Abstract

In contradiction with what has been reported before, the light signaling factor HY5 negatively regulates ABA-mediated inhibition of post-germination seedling growth by acting downstream to COP1.

Dear Editor,

Seed germination and postgermination seedling establishment are crucial early developmental events in angiosperms. Although the demarcations between these two successive events appear to be elusive, they have been defined as distinct developmental processes and identified to involve separate regulatory mechanisms at the molecular level. Seed germination is marked by the protrusion of embryonic root out of the seed coat. Postgermination seedling establishment denotes the developmental window after germination that involves the opening, greening, and expansion of cotyledons or foliar leaves, marking the switch to autotrophic development (Lopez-Molina et al., 2001; Weitbrecht et al., 2011).

Light is one of the most prominent environmental signals that influence early developmental events in plants. A well-coordinated regulation of light and abscisic acid (ABA) signaling pathways is crucial to optimize the timing and pace of germination and postgermination seedling establishment, especially under stress conditions (de Wit et al., 2016; Vaishak et al., 2019). The bZIP transcription factor ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL5 (HY5) is a key positive regulator of photomorphogenesis (Oyama et al., 1997; Gangappa and Botto, 2016). HY5 also acts as a major integrating factor for light and ABA pathways. A previous study identified that HY5 promotes ABA signaling by directly binding to the promoter of ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE5 (ABI5) and inducing its expression (Chen et al., 2008).

During seedling development, the protein level of HY5 is tightly controlled by the E3 ubiquitin ligase CONSTITUTIVELY PHOTOMORPHOGENIC1 (COP1), which ubiquitinates HY5 and targets it for proteasome-mediated degradation (Ang et al., 1998; Osterlund et al., 2000). Recently, we reported that COP1 promotes ABA-mediated inhibition of postgermination seedling establishment (Yadukrishnan et al., 2020). We observed that cop1 mutants show ABA hyposensitivity during postgermination seedling development (Yadukrishnan et al., 2020). Previous evidence suggests that hy5 is less sensitive to ABA inhibition of seedling growth (Chen et al., 2008). While the germinated Columbia-0 (Col-0) remains in a prolonged arrested state with ABA treatment, hy5 rapidly grows and establishes into seedlings (Chen et al., 2008). Together, these reports suggest that despite COP1 being a negative regulator of HY5, cop1 and hy5 mutants do not show opposite ABA sensitivities during seedling development. This prompted us to revisit the ABA-hyposensitive phenotype of hy5 mutants during postgermination seedling growth in light.

The hy5 allele used by Chen et al. (2008) was a T-DNA insertion mutant (SALK_096651) in the Columbia background. To validate the ABA-hyposensitive postgermination phenotype of hy5, we monitored its seedling establishment percentage under cycling light in the absence and presence of ABA. By day 6, both Col-0 and hy5 attained 100% seedling establishment in the absence of ABA (Fig. 1, A and B). However, in the presence of ABA, seedling establishment was considerably slower in hy5 as compared with the wild type. While ∼30% of the Col-0 seedlings attained establishment by 6 d, hy5 mutants had not started establishment (Fig. 1, A and B). Our observation indicated that the hy5 mutant might be hypersensitive to ABA during postgermination seedling development, which is contradictory to the previous report.

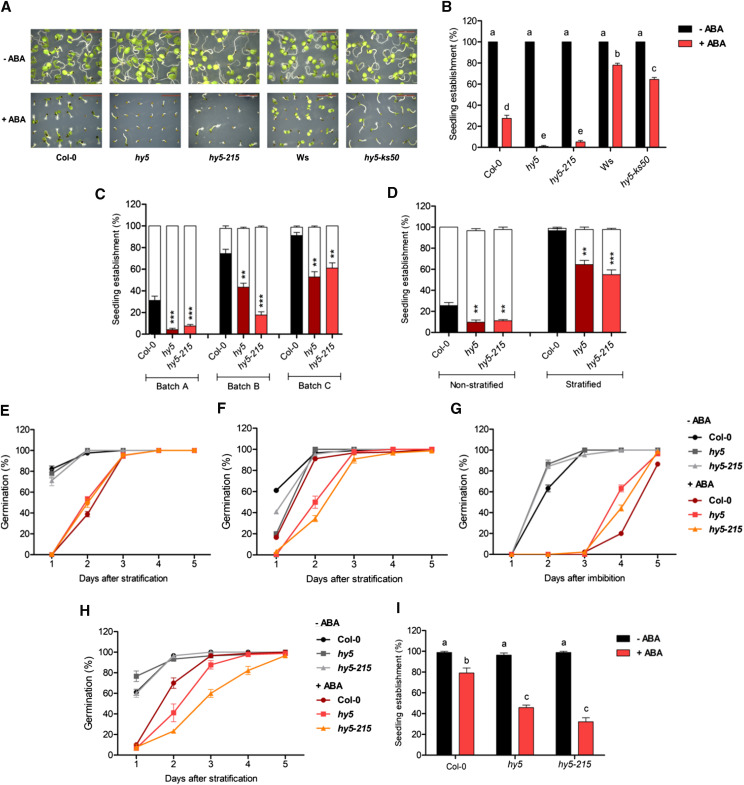

Figure 1.

HY5 negatively regulates ABA-mediated inhibition of postgermination seedling establishment. A and B, Representative images (A) and seedling establishment rates (B) of Col-0, hy5 (SALK_096651), hy5-215, Wassilewskija (Ws), and hy5-ks50 grown on 0.5× Murashige and Skoog (MS) plates complemented with and without 1 μm ABA for 6 d. Scale bars = 5 mm. C, Seedling establishment rates of three different batches of Col-0, hy5, and hy5-215 seeds grown on 0.5× MS plates without (white bars) and with (colored bars) 1 μm ABA for 6 d. Batches A, B, and C represent freshly harvested, 6-month-old, and 1-year-old seed batches, respectively. D, Seedling establishment rates of nonstratified and stratified Col-0, hy5, and hy5-215 seeds (batch C) on 0.5× MS plates without (white bars) and with (colored bars) 1 μm ABA for 6 d. Values represent means ± se of three experiments with 50 or more seeds used in each experiment. Asterisks represent statistically significant differences between the individual mutants and the wild type (***P < 0.001 and **P < 0.01) as determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s posthoc test. E and F, Germination rates of batch A (E) and batch C (F) Col-0, hy5, and hy5-215 seeds on 0.5× MS plates without and with 1 μm ABA counted up to 5 d after stratification treatment. G, Germination rates of nonstratified batch C seeds of Col-0, hy5, and hy5-215 on 0.5× MS plates without and with 1 μm ABA counted up to 5 d after imbibition. H, Germination rates of Col-0, hy5, and hy5-215 seeds (batch C) on filter paper soaked with sterile water without or with 1 μm ABA counted up to 5 d after stratification treatment. I, Seedling establishment rates of batch C seeds of Col-0, hy5, and hy5-215 germinated on water-soaked filter paper after stratification and transferred on day 2 to 0.5× MS plates without or with 5 μm ABA and grown for another 2 d. The 0.5× MS plates containing 1% (w/v) agar and no added Suc were used in the experiments. Plates were kept in long days (16 h of light/8 h of dark) with 80 μmol m−2 s−1 white light. Seeds were scored as germinated upon the emergence of radicle out of the testa and endosperm. Seedling establishment was marked by complete opening and greening of cotyledons. Values represent means ± se of three experiments with 50 or more seeds used in each experiment. Lowercase letters above the bars in B and I indicate statistical groups as determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s posthoc test (P ≤ 0.05).

To validate this further, we studied the postgermination ABA sensitivity of other widely used hy5 mutant alleles: hy5-215 and hy5-ks50 (Fig. 1, A and B). Although some of the previous studies have shown the ABA-hyposensitive germination phenotype of hy5-215, its postgermination ABA sensitivity has not been quantitatively reported (Xu et al., 2014; Fernando and Schroeder, 2015; Srivastava et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2018). Thus, we monitored the seedling establishment of hy5-215 in the presence and absence of ABA. While the wild type and hy5-215 showed 100% seedling establishment in the absence of ABA, hy5-215 showed significantly slower seedling establishment in 1 μm ABA as compared with Col-0 (Fig. 1, A and B). In the presence of ABA, ∼25% of Col-0 seedlings were established by day 6, whereas only ∼5% of hy5-215 seedlings were established (Fig. 1, A and B).

Since both hy5 (SALK_096651) and hy5-215 are in the genetic background of ecotype Columbia, we further verified the phenotype in the hy5-ks50 allele in the Ws background. When grown in the presence of 1 μm ABA, the seedling establishment rate of the wild-type Ws ecotype was higher than in the Col-0 ecotype (Fig. 1, A and B). However, the hy5-ks50 mutant showed significantly less seedling establishment in the presence of ABA as compared with the Ws wild type (Fig. 1, A and B). The seedling establishment of hy5-ks50 in ABA was greater than that of hy5 (SALK_096651) and hy5-215, indicating that the postgermination ABA sensitivity is generally weaker in the Ws genetic background (Fig. 1, A and B). All the hy5 mutant alleles tested showed varying extents of ABA-hypersensitive seedling establishment, underlining that HY5 might be a negative regulator of ABA-mediated postgermination seedling growth arrest, contrary to what has been known.

Seed age can affect dormancy, thereby modulating germination and postgermination phenotypes of seedlings both in the presence and absence of ABA (Weitbrecht et al., 2011; Shu et al., 2016). All the seeds used in the experiment mentioned above (Fig. 1, A and B) were freshly harvested. To verify if seedling establishment in Col-0 and hy5 mutants varies between different seed batches, we compared three seed batches: batch A (freshly harvested), batch B (harvested 6 months ago), and batch C (harvested 1 year ago; Fig. 1C). Sensitivity to ABA decreased in both Col-0 and hy5 mutants with seed age (Fig. 1C). However, in all the batches, hy5 and hy5-215 showed enhanced sensitivity to ABA compared with Col-0 (Fig. 1C). In our experiments, seeds were stratified for a period of 3 d, whereas the protocol followed by Chen et al. (2008) is slightly ambiguous, as the figure 2 legend therein mentions stratification while the methods section refers to a previous article that does not include stratification (Xiong et al., 2001). To investigate if stratification modulates seedling establishment, we compared the establishment of stratified and nonstratified batch C seeds (Fig. 1D). hy5 mutants showed ABA-hypersensitive seedling establishment phenotypes irrespective of the stratification treatment, although bypassing the stratification caused a stronger inhibition (Fig. 1D). Taking these data into consideration, we suspect that the difference in seed age and dormancy levels between Col-0 and hy5 seeds used by Chen et al. (2008) could possibly have contributed to the reduced ABA sensitivity of hy5 during seedling establishment seen before.

We further asked whether the ABA hypersensitivity of hy5 mutants is confined to the postgermination development of seedlings or if it starts from the germination process itself. To test this, we monitored the germination rates of these mutants in the presence and absence of ABA (Fig. 1, E–G). In the absence of ABA, freshly harvested Col-0, hy5 (SALK_096651), and hy5-215 seeds germinated at similar rates, whereas in the presence of ABA, the germination rates of hy5 mutants were marginally faster than that of Col-0 (Fig. 1E), which is in agreement with previous reports (Chen et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2014; Fernando and Schroeder, 2015; Yang et al., 2018). When we performed the same experiment with the 1-year-old seed batch, hy5 mutants showed slower germination rates compared with the wild type, reiterating the role of dormancy or seed age in modulating the sensitivity of hy5 mutants to ABA (Fig. 1F). Next, we investigated the role of stratification in regulating the germination of hy5 mutants in the presence and absence of ABA. In 1-year-old seeds in the absence of stratification, hy5 mutants germinated faster than Col-0 (Fig. 1G), which is opposite to their hypersensitive response when stratified (Fig. 1F). This emphasizes the role of stratification in regulating germination under stress.

Since Chen et al. (2008) performed their germination assays on filter paper, we also verified the germination of 1-year-old seeds on filter paper in the presence and absence of ABA and found that hy5 mutants retain the ABA-hypersensitive germination phenotype in this condition as well (Fig. 1H). When the seeds germinated on water-soaked filter paper were transferred to ABA-containing plates for further growth, hy5 mutants continued to show ABA-hypersensitive responses during seedling establishment, indicating that the postgermination ABA hypersensitivity of hy5 mutants is not a consequence of its delayed germination in ABA (Fig. 1I). Together, these results indicate that the ABA sensitivity of hy5 mutants during early development is highly influenced by levels of dormancy in different seed batches and stratification of the seeds, which might have been overlooked in some of the previous studies.

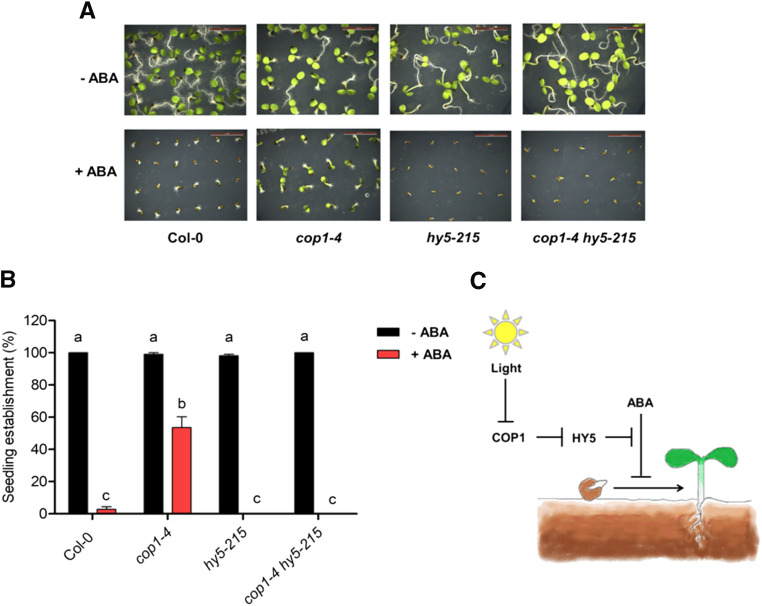

According to our observations, while hy5 mutants show ABA hypersensitivity during postgermination development, cop1 mutants show ABA hyposensitivity (Yadukrishnan et al., 2020). Since HY5 acts downstream of COP1 in light signaling and during germination, we asked if COP1 and HY5 act in a similar module to regulate postgermination ABA sensitivity. To test this, we grew cop1-4 hy5-215 double mutants (Rolauffs et al., 2012) in the presence and absence of ABA and studied their postgermination ABA sensitivity (Fig. 2, A and B). In the absence of ABA, all lines achieved 100% seedling establishment by 4 d (Fig. 2, A and B). In 1 μm ABA, cop1-4 and hy5-215 exhibited ABA-hyposensitive and -hypersensitive seedling establishment, respectively. The cop1-4 hy5-215 double mutant showed ABA sensitivity similar to hy5-215 (Fig. 2, A and B). The epistatic phenotype of hy5-215 over cop1-4 suggests that HY5 is necessary for the ABA-hyposensitive seedling establishment phenotype of cop1-4, and HY5 acts downstream of COP1 to regulate ABA-mediated inhibition of postgermination development (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

HY5 acts downstream of COP1 to regulate ABA-mediated inhibition of postgermination seedling establishment. A and B, Representative images (A) and seedling establishment rates (B) of 4-d-old Col-0, cop1-4, hy5-215, and cop1-4 hy5-215 on 0.5× Murashige and Skoog plates complemented with and without 1 μm ABA. Scale bars = 5 mm. Plates were kept in long days (16 h of light/8 h of dark) with 80 μmol m−2 s−1 white light after stratification. Seedling establishment was marked by complete opening and greening of cotyledons. Values represent means ± se of three experiments with 50 or more seeds used in each experiment. Lowercase letters above the bars indicate statistical groups as determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s posthoc test (P ≤ 0.05). C, Model showing the regulation of ABA-mediated inhibition of early seedling development by the COP1-HY5 regulatory module.

To conclude, sensing light cues from the environment and integrating them with the ABA pathway might be crucial for making the decision to switch to autotrophic growth. Under stress conditions, ABA dictates the seedling to remain in a prolonged postgermination quiescent state, whereas light favors photomorphogenic growth and autotrophic establishment of the seedling. The interaction of HY5, COP1, and possibly other regulators of light signaling with the ABA pathway might be decisive in determining the right timing for seedling establishment.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession numbers: HY5 (AT5G11260); COP1 (AT2G32950); and ABI5 (AT2G36270).

Acknowledgments

P.Y. and P.V.R. acknowledge the Department of Biotechnology, Ministry of Science and Technology, and the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, Government of India, respectively, for their Ph.D. fellowships. We thank Dr. Henrik Johansson (Free University of Berlin) for providing the cop1-4 hy5-215 double mutant.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Department of Biotechnology, Ministry of Science and Technology (grant no. BT/PR19193/BPA/118/195/2016 to S.D.), and the Science and Engineering Research Board (grant no. EMR/2016/000181 and CRG/2019/002039 to S.D.), Government of India.

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Ang LH, Chattopadhyay S, Wei N, Oyama T, Okada K, Batschauer A, Deng XW(1998) Molecular interaction between COP1 and HY5 defines a regulatory switch for light control of Arabidopsis development. Mol Cell 1: 213–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Zhang J, Neff MM, Hong SW, Zhang H, Deng XW, Xiong L(2008) Integration of light and abscisic acid signaling during seed germination and early seedling development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 4495–4500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit M, Galvão VC, Fankhauser C(2016) Light-mediated hormonal regulation of plant growth and development. Annu Rev Plant Biol 67: 513–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernando VCD, Schroeder DF(2015) Genetic interactions between DET1 and intermediate genes in Arabidopsis ABA signalling. Plant Sci 239: 166–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangappa SN, Botto JF(2016) The multifaceted roles of HY5 in plant growth and development. Mol Plant 9: 1353–1365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Molina L, Mongrand S, Chua NH(2001) A postgermination developmental arrest checkpoint is mediated by abscisic acid and requires the ABI5 transcription factor in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 4782–4787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterlund MT, Hardtke CS, Wei N, Deng XW(2000) Targeted destabilization of HY5 during light-regulated development of Arabidopsis. Nature 405: 462–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyama T, Shimura Y, Okada K(1997) The Arabidopsis HY5 gene encodes a bZIP protein that regulates stimulus-induced development of root and hypocotyl. Genes Dev 11: 2983–2995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolauffs S, Fackendahl P, Sahm J, Fiene G, Hoecker U(2012) Arabidopsis COP1 and SPA genes are essential for plant elongation but not for acceleration of flowering time in response to a low red light to far-red light ratio. Plant Physiol 160: 2015–2027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu K, Liu XD, Xie Q, He ZH(2016) Two faces of one seed: Hormonal regulation of dormancy and germination. Mol Plant 9: 34–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava AK, Senapati D, Srivastava A, Chakraborty M, Gangappa SN, Chattopadhyay S(2015) Short Hypocotyl in White Light1 interacts with Elongated Hypocotyl5 (HY5) and Constitutive Photomorphogenic1 (COP1) and promotes COP1-mediated degradation of HY5 during Arabidopsis seedling development. Plant Physiol 169: 2922–2934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaishak KP, Yadukrishnan P, Bakshi S, Kushwaha AK, Ramachandran H, Job N, Babu D, Datta S(2019) The B-box bridge between light and hormones in plants. J Photochem Photobiol B 191: 164–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitbrecht K, Müller K, Leubner-Metzger G(2011) First off the mark: Early seed germination. J Exp Bot 62: 3289–3309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong L, Gong Z, Rock CD, Subramanian S, Guo Y, Xu W, Galbraith D, Zhu JK(2001) Modulation of abscisic acid signal transduction and biosynthesis by an Sm-like protein in Arabidopsis. Dev Cell 1: 771–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D, Li J, Gangappa SN, Hettiarachchi C, Lin F, Andersson MX, Jiang Y, Deng XW, Holm M(2014) Convergence of light and ABA signaling on the ABI5 promoter. PLoS Genet 10: e1004197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadukrishnan P, Rahul PV, Ravindran N, Bursch K, Johansson H, Datta S(2020) CONSTITUTIVELY PHOTOMORPHOGENIC1 promotes ABA-mediated inhibition of post-germination seedling establishment. Plant J 103: 481–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B, Song Z, Li C, Jiang J, Zhou Y, Wang R, Wang Q, Ni C, Liang Q, Chen H, et al. (2018) RSM1, an Arabidopsis MYB protein, interacts with HY5/HYH to modulate seed germination and seedling development in response to abscisic acid and salinity. PLoS Genet 14: e1007839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]