Abstract

Individuals with dialysis-dependent kidney failure experience considerable disease- and treatment-related decline in functional status and overall well-being. Despite these experiences, there have been few substantive technological advances in KRT in decades. As such, new federal initiatives seek to accelerate innovation. Historically, integration of patient perspectives into KRT product development has been limited. However, the US Food and Drug Administration recognizes the importance of incorporating patient perspectives into the total product life cycle (i.e., from product conception to postmarket surveillance) and encourages the consideration of patient-reported outcomes in regulatory-focused clinical trials when appropriate. Recognizing the significance of identifying patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) that capture contemporary patient priorities, the Kidney Health Initiative, a public–private partnership between the American Society of Nephrology and US Food and Drug Administration, convened a workgroup to (1) develop a conceptual framework for a health-related quality of life PROM; (2) identify and map existing PROMs to the conceptual framework, prioritizing them on the basis of their supporting evidence for use in the regulatory environment; and (3) describe next steps for identifying PROMs for use in regulatory clinical trials of transformative KRT devices. This paper summarizes the proposed health-related quality-of-life PROM conceptual framework, maps and prioritizes PROMs, and identifies gaps and future needs to advance the development of rigorous, meaningful PROMS for use in clinical trials of transformative KRT devices.

Keywords: patient-reported outcomes, medical devices, innovation, dialysis, hemodialysis, end-stage renal disease, patient priorities, clinical trial, renal dialysis, quality of life, Public-Private Sector Partnerships, United States Food and Drug Administration, Patient Reported Outcome Measures, Renal Insufficiency, Renal Replacement Therapy, kidney, Patient-Centered Care

Introduction

More than 700,000 Americans receive KRT—dialysis or kidney transplantation—costing the Medicare system $35 billion in 2016 (1). Despite this investment, individuals receiving dialysis experience considerable disease- and treatment-related declines in functional status and overall well-being. Dialysis is highly burdensome, with many individuals treated with in-center hemodialysis, a therapy that is disruptive to daily life and often compounded by debilitating side effects such as cramping, fatigue, poor sleep, and depression (2–4).

To address this state of affairs, initiatives such as KidneyX, an innovation accelerator supported by a public–private partnership between the US Department of Health and Human Services and the American Society of Nephrology (ASN), and the Executive Order, Advancing American Kidney Health, seek to disrupt existing approaches to kidney care and incentivize innovation in KRT (5,6). Next-generation KRT devices are likely to encompass a spectrum of technologies, from portable to wearable to implantable bioengineered products, many with the potential to revolutionize the patient experience. Historically, integration of patient perspectives into KRT product development has been limited. However, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recognizes patient perspectives as essential to safe, effective medical product development and evaluation, and the Center for Devices and Radiologic Health named partnering with patients as a strategic priority in 2016 (7).

Using patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in defining clinical trial end points is one opportunity to encourage more patient-centered innovation and evaluation of medical products (7). Existing patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) may not adequately reflect patient priorities (8). The Standard Outcomes in Nephrology (SONG) Initiative found that patients prioritize relief of fatigue, ability to work and travel, and more dialysis-free time as outcomes for clinical trials, concepts not specifically captured in existing PROMs (2). PROMs that better capture patient priorities would focus innovators and regulators on the treatment effects most meaningful to patients.

Kidney Health Initiative Transformative KRT Devices PROM Project

Overview

PROMs used as outcome assessments in regulatory trials must meet rigorous criteria and be sensitive in detecting treatment (e.g., KRT device) effects and discriminating between scores in a clinical trial’s treatment and nontreatment arms (9,10). As such, all PROMs used in clinical practice may not be appropriate for regulatory trials. In 2018, the Kidney Health Initiative (KHI), a public–private partnership between the ASN and FDA, convened a workgroup (patient, industry, regulatory, PRO expert, and clinical representatives) to identify candidate PROMs for modification or development, validation, and eventual use in regulatory trials of transformative KRT devices. The workgroup (1) developed a conceptual framework; (2) identified existing PROMs used in kidney disease and related conditions; (3) sought patient and industry input on the framework; (4) mapped identified PROMs to the conceptual framework, prioritizing them on the basis of their supporting evidence; and (5) described the next steps for facilitating PROM use in transformative KRT device trials.

PRO Conceptual Framework

Approach.

Drawing upon workgroup expertise and evidence about patient priorities, such as the SONG Initiative and KHI’s “Technology Roadmap for Innovative Approaches to RRT,” we developed a conceptual framework capturing priority health-related quality-of-life (HRQOL) outcomes (2,3,11). Conceptual frameworks are diagrams that explicitly define the concepts measured by the PRO instrument. Such frameworks consist of measurable items that collectively describe a domain, the specific feeling, function, or perception being measured. Framework diagrams depict the relationships of instrument items to domains and domains to instrument score (10). We then sought feedback on the framework from patients and industry representatives.

Proposed Conceptual Framework.

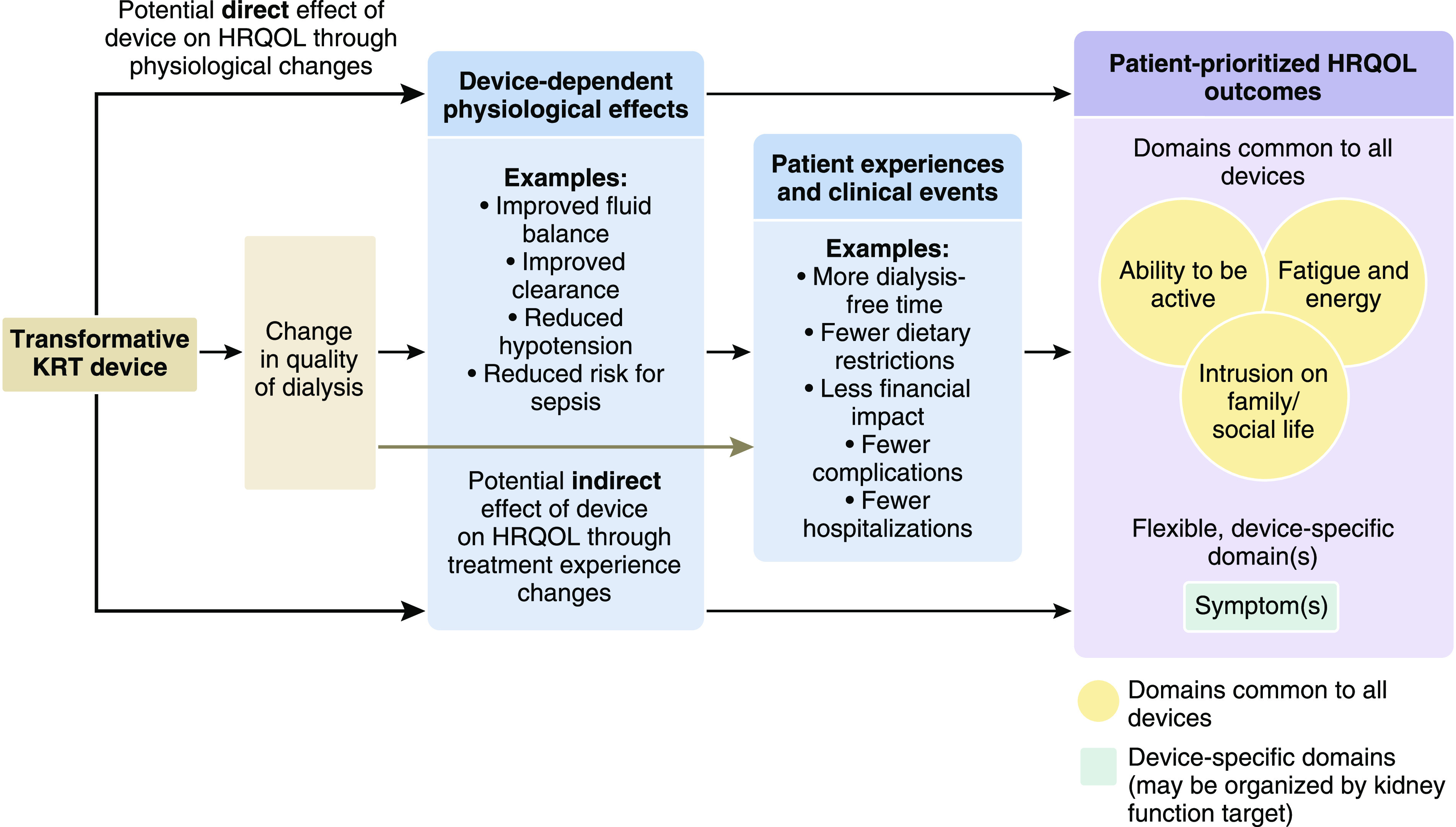

Our proposed conceptual framework (Figure 1) includes PROs suggested for use as secondary outcomes in clinical trials of transformative KRT devices with the physiologic effects of the devices serving as primary outcomes. The framework considers the current state of dialysis and posits that new devices would improve aspects of life that are negatively affected by current therapeutic approaches. The framework is not prescriptive, but rather developed to aid innovators in selecting PROMs that are meaningful to individuals with kidney failure. The framework is unlikely to be appropriate for all KRT devices.

Figure 1.

The proposed conceptual framework for a HRQOL PROM for transformative KRT devices includes three common domains and unlimited, device-specific symptom domains. The patient-reported outcome conceptual framework depicts the hypothesis that transformative KRT devices could affect HRQOL either directly, through changes in physiologic effects (e.g., improvement in fluid balance, reduction in intradialytic hypotension, etc.), and/or indirectly, through changes in patients’ experiences with the treatment (e.g., more dialysis-free time, fewer dietary restrictions, etc.). The framework consists of three core HRQOL-related domains posited as common to all devices (fatigue and energy, intrusion on family/social life, and ability to be active), and an unlimited number of flexible symptom domains that are device-specific. Relevant symptom domains would be selected on the basis of device characteristics and physiologic targets (e.g., clearance, ultrafiltration). A domain is the specific feeling, function, or perception being measured. HRQOL, health-related quality of life; PROM, patient-reported outcome measure.

In developing the framework, we hypothesized that transformative KRT devices could affect HRQOL either directly, through changes in physiologic effects (e.g., reduction in intradialytic hypotension and associated symptom alleviation), and/or indirectly, through changes in patients’ experiences with the treatment (e.g., reduction in requisite number of in-clinic treatment hours and associated increase in time for patient-prioritized activities). The framework consists of three core HRQOL-related domains posited as common to many KRT devices (fatigue and energy, intrusion on family/social life, and ability to be active), and an unspecified number of flexible symptom domains that are device-specific. We intend for developers to select symptom domains on the basis of device characteristics and physiologic targets. Device-specific symptom domains may capture single symptom constructs or symptom clusters related to the device’s target (e.g., clearance, ultrafiltration).

Our framework builds on the traditional, multidimensional concept of HRQOL that accounts for physical, mental, emotional, and social functioning. The proposed domains of “ability to be active,” “fatigue and energy,” and “intrusion on family and social life” reflect specific aspects of physical, mental, and emotional health that are important to patients and are more proximal to (i.e., closer to) the treatment, and are thus more likely to show a meaningful treatment effect (9). For example, a new device that reduces in-clinic treatment time may impose less on a patient’s family/social life, allowing for more time spent participating in enjoyable, meaningful life activities. Such treatment effects would be experienced before downstream changes in emotional and/or social functioning. Per FDA guidance on selecting, developing, and modifying clinical outcome assessments for the regulatory environment, outcomes that are more proximal to the treatment being studied provide better evidence of effectiveness because the observed effect(s) link back to the treatment more reliably (9). However, we recognize the potential utility in assessing traditional HRQOL concepts or other outcomes, including device intrusion and feelings of safety, among others. Developers may opt to assess such PROs in addition to or in lieu of our proposed domains.

Stakeholder Insights on the Conceptual Framework.

Overall, patient and industry representatives expressed enthusiasm about the framework, noting that it was straightforward, captured aspects of HRQOL most important to individuals living with kidney failure, and represented an important step toward incorporating patient perspectives into medical device development and evaluation (Table 1). Many patients emphasized the importance of symptoms and desired to see specific symptoms such as insomnia and sexual dysfunction in the framework. Some industry representatives expressed uncertainty about whether every framework concept was necessary for every trial and for all KRT devices. One individual pointed out that some of the domains (e.g., intrusion on family/social life) were deficit-focused, suggesting reframing domains in terms of strengths rather than deficiencies.

Table 1.

Patient, care partner, and industry representative feedback on the conceptual framework

| Feedback | Patients and Care Partnersa | Professionalsb |

|---|---|---|

| Overall impressions | • Overwhelmingly positive reactions from all participants | • All but one interviewee had an overall positive reaction to the framework |

| Strengths | • Straightforward, sound, and well rounded | • Domains accurately reflect priorities of patients and families by capturing what they really want, which is “their life back” |

| • Core domains accurately capture aspects of quality of life that are important to individuals living with kidney disease | • Consistent with other core patient outcomes that have been reported (e.g., SONG initiative) | |

| • Core domains capture constructs that are meaningful and perceived to be closely linked to quality of life rather than functional states that may have lesser effect on quality of life (e.g., ability to be active rather than physical function) | • Formally conveys the importance of including the patient voice in innovation; tool can help industry communicate the value to leadership | |

| • Signals long-awaited shift toward prioritizing patient input in medical device innovation | ||

| Weaknesses | • Missing specific symptoms that are important to patients, such as insomnia and sexual functionc | • Unclear whether the framework fits all potential new devices or only devices to enhance dialysis |

| • Not written in patient-friendly language | • Deficit framing of domains | |

| • Does not capture whether patients “feel safe” when using the device | • Missing domains that are important such as pain, device intrusion, diet, mental health, physical activity | |

| • Does not account for other objective measures such as total costs to society, productivity losses, social acceptance/stigma, time on therapy, etc. | ||

| Future directions | • Develop messaging around the purpose of the framework for patients, families, and other stakeholders who may find it useful, such as CMS and dialysis provider organizations | • Determine next steps in translating the framework to development of a PROM that could be used in the regulatory environment (what would it look like? how administered? etc.) |

| • Adapt language and content level when communicating the framework to nonprofessional audiences | • Consider reframing appropriate domains to focus on strengths/assets rather than deficits (e.g., ability to engage in family/social life versus intrusion on family/social life) | |

| • Advocate for adoption of the framework in future trials by industry/inventers | • Consider potential unintended consequences of the framework, such as increased risk to developers in terms of costs or FDA approval, reduced comparability of trials, and redundancy with adverse event data | |

| • Engage CMS and private payers to align reimbursement with patient priorities |

SONG, Standardized Outcomes in Nephrology; CMS, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; PROM, patient-reported outcome measure; FDA, US Food and Drug Administration.

Patient participants (n=9) were members of the Kidney Health Initiative Patient and Family Partnership Council (one current patient on hemodialysis; six transplant recipients, all of whom had received dialysis in the past; two care partners). Perspectives were elicited during a 90-minute teleconference focus group, conducted by a trained moderator using a standardized moderator guide.

Industry representative participants (n=7) had experience with medical device development related to KRT. Perspectives were elicited during 30- to 60-minute, semistructured telephone interviews, conducted by a trained interviewer using a standardized interviewer guide.

Participants reviewed a version of the framework that included example symptom domains that were not intended to be exhaustive. We intend for device developers to select symptoms for PROM inclusion on the basis of the device characteristics and kidney function targets. Existing symptom prioritization data may also guide decisions (4).

Review and Evaluation of Existing PROMs

Using PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library databases, we conducted a targeted search to identify PROMs used in kidney disease and related conditions (Supplemental Appendix 1, Supplemental Figure 1). Two reviewers independently reviewed abstracts and identified 217 unique PROMs (Supplemental Table 1). We mapped these PROMs to the conceptual framework, assessed their supporting evidence for use as outcomes in the regulatory environment, and identified evidence gaps. We relied on FDA PRO guidance to inform criteria used to select PROMs for in-depth review (10). In doing so, we excluded PROMs that were specific to other conditions and thus not appropriate as PROs for trials of KRT devices, PROMs with single-items for concepts that lacked evidence on scoring and/or validity of those domains (e.g., symptom checklists), and PROMs outside this project’s scope (e.g., treatment satisfaction). This resulted in 27 PROMs for in-depth review (Supplemental Table 1).

The steering committee and FDA representatives (Supplemental Table 2) met in March 2019 to identify gaps in extant measures relative to their validation. We prioritized the instruments on the basis of their concept/domain definition, burden, evidence of scientific acceptability (validity, reliability, responsiveness), and scoring, among other factors (Table 2). Table 3 displays the prioritized PROMs mapped to the conceptual framework domains and identified needs, as well as future directions for identifying domain-specific PROMs for use in regulatory trials of transformative KRT devices. In prioritizing these instruments, we are not endorsing them, but are instead suggesting that these instruments deserve further evaluation when developers are considering PROMs for regulatory applications.

Table 2.

Evaluation criteria used to prioritize patient-reported outcome measures mapped to the conceptual framework

| Criteriaa,b | 'Type | Definition (Example Criteria) |

|---|---|---|

| Burden | Item number, complexity, time to completion | |

| Validity | ||

| Content | Evidence that instrument measures the concept of interest in the intended population (qualitative interviews, focus groups with target population) | |

| Construct | Evidence that relationships among items, domains, and concepts conform to a priori hypotheses about relationships that should exist with measures of related concepts (discriminant and convergent validity, known group validity)c | |

| Reliability | ||

| Test-retest | Stability of scores over time when no change in the measurement concept is expected (intraclass correlation coefficient) | |

| Internal consistency | Extent to which items comprising a scale measure the same concept (Cronbach alpha, item-total correlations) | |

| Responsiveness | Evidence that instrument can identify differences in scores over time in individuals who have changed with respect to the measurement concept (within-person change over time, effect size statistic) | |

| Scoring | Scores easily interpretable versus not | |

| Availability | Public domain versus not | |

| Translation | Translation with relevant language and cultural validation versus not | |

PROM, patient-reported outcome measure; FDA, US Food and Drug Administration.

Meeting participants considered these criteria (in listed order) when evaluating the PROMs selected for in-depth review and in prioritizing the PROMs for framework mapping.

The presented criteria reflect some, but not all, of the PROM properties evaluated when using PROMs in clinical trials reviewed by the FDA. Please see the FDA’s Guidance for Industry on Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims (issued by the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, and the Center for Devices and Radiologic Health) for more information (10).

Discriminant and convergent validity measure the strength of correlation testing a priori hypotheses, and known group validity measures the degree to which the instrument can distinguish among groups hypothesized a priori to be different.

Table 3.

Prioritized patient-reported outcome measures by conceptual framework domain and future directions

| Domain and Prioritized PROMs | Gaps and Future Directions |

|---|---|

| Fatigue and energy | |

| Domain in general | • Concept elicitation to evaluate relative importance of energy and vitality |

| Chalder Fatigue Scale | • Developed for chronic fatigue so may not capture fatigue as relevant to kidney failure |

| • Weak responsiveness testing relevant to KRT | |

| • No identified Spanish language version | |

| Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-Fatigue) | • Lack of validation testing in the dialysis population |

| • Lack of responsiveness testing relevant to KRT | |

| • Scoring not intuitive (i.e., not normalized and a higher score represents lesser fatigue) | |

| Intrusion on family/social life | |

| Domain in general | • Concept elicitation to prioritize most important aspects of family/social life to evaluate, including defining “family” |

| PROMIS Item Bank v2.0 Ability to Participate in Social Roles and Activities | • Lack of validation testing in the dialysis population |

| • Lack of responsiveness testing relevant to KRT | |

| Ability to be active | |

| Domain in general | • Concept elicitation to prioritize most important aspects of activity to evaluate |

| • Identification or development of measures assessing ability to work or go to school | |

| PROMIS Physical Function Item Bank | • Lack of validation testing in the dialysis population |

| • Full item bank (165 items) too burdensome and role of CAT in regulatory-focused clinical trials unclear; unclear if short form versions capture most important aspects of concept | |

| • Limited questions related to ability to work/go to school | |

| Freedom domain of the CHOICE Health Experience Questionnaire (CHEQ) | • Validation testing among a more contemporary dialysis population |

| • Lack of responsiveness testing relevant to KRT | |

| Symptoms | |

| Domain(s) in general | • Evaluation of symptom clusters as they relate to potential device physiologic targets (e.g., uremia-related symptoms, fluid-related symptoms) |

| • Identification of optimal, symptom-specific PROMs | |

| • Known gaps in existing PROMs for the symptoms of cramping and swelling | |

| PROMIS | • Lack of validation testing in the dialysis population |

| • Lack of responsiveness testing relevant to KRT | |

| Disease-specific symptom instruments | • Exploration of the potential overlap of function related to symptoms and function itself (as captured in the core domains) |

| • Identification of symptom clusters relevant to physiologic targets | |

PROM, patient-reported outcome measure; PROMIS, Patient-Reported-Outcome Measures Information System; CAT, computerized adaptive testing.

Prioritized PROMs by Domain

Fatigue and Energy.

Description.

Fatigue is a common symptom among individuals receiving dialysis, affecting as many as 90% of patients; moreover, it is associated with higher mortality and lower HRQOL (12–15). In prioritization exercises, patients rated fatigue of higher importance than death, describing that fatigue limits their ability to work and participate in social interactions, negatively affecting HRQOL (2,4). However, fatigue is multidimensional and lacks a universally accepted definition. A systematic review found 11 potential content dimensions of fatigue, with level of energy, tiredness, and life participation being the most frequently assessed dimensions in existing PROMs (13). To reflect the patient-expressed desire for return of vitality and energy, not merely absence of fatigue, we considered the assessment of energy (and/or vitality) of equal importance to the assessment of fatigue/tiredness in evaluating the PROMs (12).

Prioritized Measures.

We reviewed 18 fatigue PROMs, evaluating their measurement properties and their inclusion of both tiredness and energy assessments. We identified the Chalder Fatigue Scale and Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-Fatigue) instruments as the highest priority measures to evaluate further. The Chalder Fatigue Scale is a publicly available, low-burden questionnaire (11 items) that assesses fatigue over the last month and has demonstrated validity and reliability in the kidney failure population (13,16). FACIT-Fatigue is a publicly available, low-burden questionnaire (13 items) that assesses fatigue over the past 7 days and has been used in the dialysis population (17,18). FACIT-Fatigue exhibits validity, reliability, and responsiveness to change in nondialysis populations (19,20) and content validity in the Chinese hemodialysis population (18), but its lack of validation in other populations is a weakness. Both questionnaires contain at least one energy-focused item. Finally, we acknowledge the SONG Initiative’s ongoing effort to develop a fatigue PROM, and its supporting data will be evaluated once available (12,13,21).

We downgraded measures without energy-related items (e.g., Fatigue Symptom Inventory-Short Form and Fatigue Severity Scale). However, such fatigue-only measures could be supplemented by energy-related measures and/or items to capture the desired spectrum of fatigue dimensions. In addition, we did not distinguish between energy (capacity to be active) and vitality (psychologic sense of aliveness, enthusiasm, or energy) (22). Future population-specific qualitative work is needed to determine their relative importance and inform domain content.

Intrusion on Family and Social Life.

Description.

Patients cite dialysis-free time and the effect of disease/treatment on family and friends as high priority outcomes for dialysis trials (2,23). Impaired social relationships (defined broadly as personal relationships, social support, and sexual activity) have been associated with adverse outcomes such as hospitalizations and mortality in diverse patient populations, including the dialysis population (24–27). We selected intrusion on family/social life for framework inclusion to capture device effect on an individual’s ability to participate in valued relationships. This concept is intended to assess specific aspects of life interference and treatment effect on relationships. However, it is challenging to measure as people differently prioritize how and with whom they spend their time, and some may define “family” more broadly than traditional constructs.

Prioritized Measures.

We reviewed 12 measures, prioritizing the PROM Information System (PROMIS) Item Bank v2.0 Ability to Participate in Social Roles and Activities instrument because of its content relevance. This item bank has demonstrated acceptable validity (28) and reliability (29) in the general population; however, population-specific validation is needed. Although we found support for the content validity and psychometric properties of some items in the Ferrans and Power Quality of Life Index and Illness Impact Scale (30–32), the response scales were deemed inappropriate because they refer to the degree of importance of or satisfaction with each health topic. Some PROMs were too specific, with items on family impact only and without items on other social relationships (e.g., PROMIS Item Bank v1.0 Satisfaction with Participation in Social Roles), whereas other PROMs were too general, lacking items on specific patient priorities (e.g., Kidney Disease Quality of Life 36-ItemShort Form Survey) (33,34).

Ability to be Active.

Description.

Individuals living with kidney failure value their ability to work and travel and dialysis-free time. We intend for the “ability to be active” domain to encompass both whether people are physically able to do something and whether they feel they can do it (i.e., physical and perceived limitations). As with intrusion on family/social life, individuals have different desired activity states with varying interest(s) in work, travel, and degrees of mobility/physical function. Not all aspects (e.g., work and travel) are applicable to all individuals. Therefore, we sought to identify PROMs measuring freedom or ability to pursue activities of choice.

Prioritized Measures.

We reviewed eight measures relevant to this domain, prioritizing the PROMIS Physical Function Item Bank and the freedom domain of the CHOICE Health Experience Questionnaire (CHEQ) (35–37). The 165-item PROMIS item bank includes items on mobility, work/function, leisure/recreational activities, and the four-item CHEQ freedom domain captures work/travel, convenience, and freedom. Although the contents of both measures are highly domain-relevant, both instruments have weaknesses. The PROMIS measure has not been validated or used in the adult dialysis population (38,39), and we found no responsiveness data for the CHEQ freedom domain. Moreover, neither instrument addresses ability to work (professionally) or attend school, and, to our knowledge, instruments capturing these constructs have not been used in the dialysis population (e.g., Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaire [40]).

Device-Specific, Flexible Symptom Domain(s).

Description.

Individuals receiving KRT experience a high burden of symptoms, many of which plausibly relate to the dialysis treatment and, hence, may be alleviated by next-generation KRT devices. Common symptoms include pain, pruritus, insomnia, and cramping, among others (41,42). We included a placeholder for an unlimited number of device-specific, flexible symptom domains in our framework. As symptom alleviation would likely vary by device, developers would select symptoms to evaluate on the basis of device characteristics, kidney functional target (e.g., ultrafiltration, clearance, etc.), and existing patient symptom prioritization data. For example, a wearable device that provides near-continuous ultrafiltration might alleviate symptoms related to hypotension (e.g., cramping, lightheadedness), whereas a clearance-based device might alleviate symptoms related to uremia (e.g., poor appetite, itching). Therefore, developers would consider PROMs that capture the symptom constructs most relevant to their devices. Finally, there are few empirical data linking discrete symptom clusters to aspects of kidney failure such as volume management and uremia. As such, it may be prudent to consider single symptom constructs rather than multisymptom constructs for these domains (9).

Potential Measures.

Given the number of symptoms, we did not exhaustively review symptom PROMs. In general, use of PROMs with multiple items per symptom construct may be more useful than single-item symptom checklists. However, symptom checklists may have utility in safety assessments. As with other domain PROMs, selected symptom PROMs should be fit for purpose for their intended use with respect to validity, reliability, and responsiveness, among other criteria (10,11).

The PROMIS measure repository may be a useful source of symptom-specific PROMs. Examples of relevant instruments include PROMIS Item Bank Dyspnea Functional Limitations v1.0, Itch-Interference, and Gastrointestinal Nausea and Vomiting v1.0. However, many PROMIS instruments have not been validated in dialysis populations (39). Beyond PROMIS, there are disease-specific symptom instruments to consider (e.g., Uremic Pruritus in Dialysis Patients [UP-DIAL] [43], and Dialysis Thirst Index [44]). A recent clinical trial of an antipruritus drug in patients receiving hemodialysis used the 5-D Itch and Skindex-10 instruments to evaluate itch-related HRQOL (45). There are no disease-specific PROMs for the prevalent symptoms of cramping and swelling; however, this is an area of active inquiry (46). In general, developers could generate an end-point model specific to the anticipated physiologic effects of their devices, including how patients may experience these effects in terms of symptoms, and then select PROMs to assess relevant, device-specific symptoms.

Future Directions and Considerations

At this stage, there is uncertainty about the precise content of instruments capturing our conceptual framework of PRO domains relevant to transformative KRT devices. Conceptual frameworks of PRO instruments are intended to evolve and be confirmed as empirical evidence for domains, item grouping, and scoring accumulates over the course of instrument development and clinical trial performance (10). Future work, particularly regarding clarification of domain constructs, identification of potential instruments and/or items for inclusion, and assessment of domain overlap, is needed. Beyond PROM content, it is important to evaluate the optimal mode of instrument administration, specifically the use of computerized adaptive testing. Although computerized adaptive testing is an attractive approach to tailoring domain items to individual respondents and decreasing respondent burden, it is not widely used in regulatory-focused trials (47). In addition, we considered but did not comprehensively review pediatric measures; pediatric-specific PROM work is needed (48).

We developed the framework agnostic to specific devices because such devices are still under development. As such, we focused on patient-prioritized outcomes that relate to HRQOL and kidney function but may not apply to all KRT devices. Finally, this proposal is neither a mandate nor a guideline. Rather, it is an effort to synthesize existing data on patient priorities into a cohesive framework that can be used to catalyze patient-centered innovation by incorporating patient perspectives into both the development and regulatory evaluation stages of the total product life cycle. Additional work is needed before the framework is ready for use, and we intend for this proposal to serve as a stimulant for such work. Existing FDA guidance on PROs does not mandate inclusion of PROs in trials, but encourages their consideration.

Incorporation of the patient voice into medical product development helps ensure that products on the US market meet patient needs and priorities. We developed a conceptual framework intended to (1) inspire the consideration of outcomes important to patients in KRT device development and evaluation and (2) serve as a guide toward developing rigorous, more meaningful measures of the patient experience with transformative KRT devices. Although additional work is required, the proposed framework marks an essential step toward transforming both the development and delivery of KRT through patient-centered innovation.

Disclosures

J.E. Flythe has received speaking honoraria from American Renal Associates, ASN, Dialysis Clinic Incorporated (DCI), National Kidney Foundation, and multiple universities; research funding for studies unrelated to this project from the Renal Research Institute, a subsidiary of Fresenius Medical Care, North America; and consulting fees from AstraZeneca and Fresenius Medical Care, North America in the past 3 years. She is on the medical advisory board to NxStage Medical, a subsidiary of Fresenius Medical Care, North America. P. Roy-Chaudhury is a consultant or advisory board member for Akebia, Bayer, BD-Bard, Cormedix, InRegen, Medtronic, Reata, Relypsa (a Vifor Company), and WL Gore. He is the chief scientific officer and founder of Inovasc LLC, and has received honoraria and travel support from multiple societies and universities. M. Unruh has received speaking honoraria from ASN, Fresenius Medical Care, North America, and multiple universities in the past 2 years; has received research support for studies unrelated to this report from DCI; and has served as chair of a data monitoring board for Cara Therapeutics. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This work was supported by US Food and Drug Administration Broad Agency Agreement award HHSF223201810189C. This work was also supported by the KHI, a public–private partnership between ASN, the US Food and Drug Administration, and >100 member organizations and companies to enhance patient safety and foster innovation in kidney disease. J.E. Flythe is supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant K23 DK109401. P. Roy-Chaudhury is supported by the NIH, US Department of Veterans Affairs, and National Science Foundation. R.D. Perrone is supported in part by Tufts Clinical and Translational Science Institute grant UL1TR002544.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Kidney Health Initiative (KHI) Patient Family Partnership Council and industry stakeholders who participated in the focus group and interviews about the proposed conceptual framework.

KHI funds were used to defray costs incurred during the conduct of the project, including project management support, which was expertly provided by American Society of Nephrology (ASN) consultant Grace Squillaci. The authors of this paper had final review authority and are fully responsible for its content. KHI makes every effort to avoid actual, potential, or perceived conflicts of interest that may arise as a result of industry relationships or personal interests among the members of the workgroup. More information on KHI, the workgroup, or the conflict of interest policy can be found at www.kidneyhealthinitiative.org.

The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policies of any KHI member organization, the US Department of Veterans Affairs, or the US Department of Health and Human Services, nor does any mention of trade names, commercial practices, or organization imply endorsement by the US Government.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.00110120/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Appendix 1. Targeted literature search to identify existing patient-reported outcome measures.

Supplemental Figure 1. Flow chart of article and instrument selection.

Supplemental Table 1. Patient-reported outcome measures identified in the targeted literature search.

Supplemental Table 2. In-person meeting attendees.

References

- 1.Saran R, Robinson B, Abbott KC, Agodoa LYC, Bragg-Gresham J, Balkrishnan R, Bhave N, Dietrich X, Ding Z, Eggers PW, Gaipov A, Gillen D, Gipson D, Gu H, Guro P, Haggerty D, Han Y, He K, Herman W, Heung M, Hirth RA, Hsiung JT, Hutton D, Inoue A, Jacobsen SJ, Jin Y, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kapke A, Kleine CE, Kovesdy CP, Krueter W, Kurtz V, Li Y, Liu S, Marroquin MV, McCullough K, Molnar MZ, Modi Z, Montez-Rath M, Moradi H, Morgenstern H, Mukhopadhyay P, Nallamothu B, Nguyen DV, Norris KC, O’Hare AM, Obi Y, Park C, Pearson J, Pisoni R, Potukuchi PK, Repeck K, Rhee CM, Schaubel DE, Schrager J, Selewski DT, Shamraj R, Shaw SF, Shi JM, Shieu M, Sim JJ, Soohoo M, Steffick D, Streja E, Sumida K, Kurella Tamura M, Tilea A, Turf M, Wang D, Weng W, Woodside KJ, Wyncott A, Xiang J, Xin X, Yin M, You AS, Zhang X, Zhou H, Shahinian V: US renal data system 2018 annual data report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 73[Suppl 1]: A7–A8, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evangelidis N, Tong A, Manns B, Hemmelgarn B, Wheeler DC, Tugwell P, Crowe S, Harris T, Van Biesen W, Winkelmayer WC, Sautenet B, O’Donoghue D, Tam-Tham H, Youssouf S, Mandayam S, Ju A, Hawley C, Pollock C, Harris DC, Johnson DW, Rifkin DE, Tentori F, Agar J, Polkinghorne KR, Gallagher M, Kerr PG, McDonald SP, Howard K, Howell M, Craig JC; Standardized Outcomes in Nephrology–Hemodialysis (SONG-HD) Initiative: Developing a set of core outcomes for trials in hemodialysis: An international Delphi survey. Am J Kidney Dis 70: 464–475, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tong A, Manns B, Hemmelgarn B, Wheeler DC, Evangelidis N, Tugwell P, Crowe S, Van Biesen W, Winkelmayer WC, O’Donoghue D, Tam-Tham H, Shen JI, Pinter J, Larkins N, Youssouf S, Mandayam S, Ju A, Craig JC; SONG-HD Investigators: Establishing core outcome domains in hemodialysis: Report of the standardized outcomes in nephrology-hemodialysis (SONG-HD) consensus workshop. Am J Kidney Dis 69: 97–107, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flythe JE, Hilliard T, Castillo G, Ikeler K, Orazi J, Abdel-Rahman E, Pai AB, Rivara MB, St Peter WL, Weisbord SD, Wilkie C, Mehrotra R: Symptom prioritization among adults receiving in-center hemodialysis: A mixed methods study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 735–745, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White House: Executive Order on Advancing American Kidney Health, 2019. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/executive-order-advancing-american-kidney-health/. Accessed November 12, 2019

- 6.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: KidneyX, 2019. Available at: http://www.kidneyx.org/. Accessed on November 12, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Food and Drug Administration; Center for Devices and Radiological Health: Value and Use of Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs) in Assessing Effects Of Medical Devices (CDRH Strategic Priorities 2016-2017). Available at: https://www.fda.gov/media/109626/download. Accessed November 12, 2019

- 8.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: End-Stage Renal Disease Patient-Reported Outcomes Technical Expert Panel Final Report, 2017. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/MMS/TEP-Current-Panels.html. Accessed November 12, 2019

- 9.U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Patient-Focused Drug Development Guidance: Methods to Identify What Is Important to Patients and Select, Develop or Modify Fit-For-Purpose Clinical Outcome Assessments, 2018. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/patient-focused-drug-development-guidance-methods-identify-what-important-patients-and-select. Accessed November 12, 2019

- 10.U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. Guidance for Industry, 2009. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/patient-reported-outcome-measures-use-medical-product-development-support-labeling-claims. Accessed November 12, 2019

- 11.American Society of Nephrology; Kidney Health Initiative: Technology Roadmap for Innovative Approaches to Renal Replacement Therapy, 2018. Available at: https://www.asn-online.org/g/blast/files/KHI_RRT_Roadmap1.0_FINAL_102318_web.pdf. Accessed on November 12, 2019

- 12.Jacobson J, Ju A, Baumgart A, Unruh M, O’Donoghue D, Obrador G, Craig JC, Dapueto JM, Dew MA, Germain M, Fluck R, Davison SN, Jassal SV, Manera K, Smith AC, Tong A: Patient perspectives on the meaning and impact of fatigue in hemodialysis: A systematic review and thematic analysis of qualitative studies. Am J Kidney Dis 74: 179–192, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ju A, Unruh ML, Davison SN, Dapueto J, Dew MA, Fluck R, Germain M, Jassal SV, Obrador G, O’Donoghue D, Tugwell P, Craig JC, Ralph AF, Howell M, Tong A: Patient-reported outcome measures for fatigue in patients on hemodialysis: A systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis 71: 327–343, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jhamb M, Weisbord SD, Steel JL, Unruh M: Fatigue in patients receiving maintenance dialysis: A review of definitions, measures, and contributing factors. Am J Kidney Dis 52: 353–365, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jhamb M, Liang K, Yabes J, Steel JL, Dew MA, Shah N, Unruh M: Prevalence and correlates of fatigue in chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease: Are sleep disorders a key to understanding fatigue? Am J Nephrol 38: 489–495, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Picariello F, Moss-Morris R, Macdougall IC, Chilcot J: Measuring fatigue in haemodialysis patients: The factor structure of the Chalder Fatigue Questionnaire (CFQ). J Psychosom Res 84: 81–83, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tennant KF: Assessment of Fatigue in Older Adults: The FACIT Fatigue Scale (Version 4), 2019. Available at: https://consultgeri.org/try-this/general-assessment/issue-30.pdf. Accessed November 12, 2019

- 18.Wang SY, Zang XY, Liu JD, Gao M, Cheng M, Zhao Y: Psychometric properties of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-Fatigue) in Chinese patients receiving maintenance dialysis. J Pain Symptom Manage 49: 135–143, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Acaster S, Dickerhoof R, DeBusk K, Bernard K, Strauss W, Allen LF: Qualitative and quantitative validation of the FACIT-fatigue scale in iron deficiency anemia. Health Qual Life Outcomes 13: 60, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Webster K, Cella D, Yost K: The functional assessment of chronic illness therapy (FACIT) measurement system: Properties, applications, and interpretation. Health Qual Life Outcomes 1: 79, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ju A, Unruh M, Davison S, Dapueto J, Dew MA, Fluck R, Germain M, Jassal SV, Obrador G, O’Donoghue D, Josephson MA, Craig JC, Viecelli A, O’Lone E, Hanson CS, Manns B, Sautenet B, Howell M, Reddy B, Wilkie C, Rutherford C, Tong A; SONG-HD Fatigue Workshop Collaborators: Establishing a core outcome measure for fatigue in patients on hemodialysis: A standardized outcomes in nephrology-hemodialysis (SONG-HD) consensus workshop report. Am J Kidney Dis 72: 104–112, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guérin E: Disentangling vitality, well-being, and quality of life: A conceptual examination emphasizing their similarities and differences with special application in the physical activity domain. J Phys Act Health 9: 896–908, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manns B, Hemmelgarn B, Lillie E, Dip SC, Cyr A, Gladish M, Large C, Silverman H, Toth B, Wolfs W, Laupacis A: Setting research priorities for patients on or nearing dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 1813–1821, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tough H, Siegrist J, Fekete C: Social relationships, mental health and wellbeing in physical disability: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 17: 414, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valtorta NK, Moore DC, Barron L, Stow D, Hanratty B: Older adults’ social relationships and health care utilization: A systematic review. Am J Public Health 108: e1–e10, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neumann D, Lamprecht J, Robinski M, Mau W, Girndt M: Social relationships and their impact on health-related outcomes in peritoneal versus haemodialysis patients: A prospective cohort study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 33: 1235–1244, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sousa H, Ribeiro O, Paúl C, Costa E, Miranda V, Ribeiro F, Figueiredo D: Social support and treatment adherence in patients with end-stage renal disease: A systematic review. Semin Dial 32: 562–574, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hahn EA, DeWalt DA, Bode RK, Garcia SF, DeVellis RF, Correia H, Cella D; PROMIS Cooperative Group: New English and Spanish social health measures will facilitate evaluating health determinants. Health Psychol 33: 490–499, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Terwee CB, Crins MHP, Boers M, de Vet HCW, Roorda LD: Validation of two PROMIS item banks for measuring social participation in the Dutch general population. Qual Life Res 28: 211–220, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferrans CE, Powers MJ: Quality of life index: Development and psychometric properties. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 8: 15–24, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang E, Bansal A, Novak M, Mucsi I: Patient-reported outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease and kidney transplant-part 1. Front Med (Lausanne) 4: 254, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McNair AG, Whistance RN, Forsythe RO, Rees J, Jones JE, Pullyblank AM, Avery KN, Brookes ST, Thomas MG, Sylvester PA, Russell A, Oliver A, Morton D, Kennedy R, Jayne DG, Huxtable R, Hackett R, Dutton SJ, Coleman MG, Card M, Brown J, Blazeby JM; CONSENSUS-CRC (Core Outcomes and iNformation SEts iN SUrgical Studies - ColoRectal Cancer) Working Group: Synthesis and summary of patient-reported outcome measures to inform the development of a core outcome set in colorectal cancer surgery. Colorectal Dis 17: O217–O229, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hays RD, Kallich JD, Mapes DL, Coons SJ, Carter WB: Development of the kidney disease quality of life (KDQOL) instrument. Qual Life Res 3: 329–338, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peipert JD, Bentler PM, Klicko K, Hays RD: Psychometric properties of the kidney disease quality of life 36-item short-form survey (KDQOL-36) in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 71: 461–468, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.HealthMeasures; Northwestern University: PROMIS Bank v2.0 - Physical Function, 2016. Available at: http://www.healthmeasures.net/index.php?option=com_instruments&view=measure&id=789&Itemid=992. Accessed November 12, 2019

- 36.Wu AW, Fink NE, Cagney KA, Bass EB, Rubin HR, Meyer KB, Sadler JH, Powe NR: Developing a health-related quality-of-life measure for end-stage renal disease: The CHOICE Health Experience Questionnaire. Am J Kidney Dis 37: 11–21, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aiyasanon N, Premasathian N, Nimmannit A, Jetanavanich P, Sritippayawan S: Validity and reliability of CHOICE health experience questionnaire: Thai version. J Med Assoc Thai 92: 1159–1166, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Selewski DT, Massengill SF, Troost JP, Wickman L, Messer KL, Herreshoff E, Bowers C, Ferris ME, Mahan JD, Greenbaum LA, MacHardy J, Kapur G, Chand DH, Goebel J, Barletta GM, Geary D, Kershaw DB, Pan CG, Gbadegesin R, Hidalgo G, Lane JC, Leiser JD, Song PX, Thissen D, Liu Y, Gross HE, DeWalt DA, Gipson DS: Gaining the patient reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) perspective in chronic kidney disease: A Midwest Pediatric Nephrology Consortium study. Pediatr Nephrol 29: 2347–2356, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peipert JD, Hays RD: Expanding the patient’s voice in nephrology with patient-reported outcomes. J Am Soc Nephrol 30: 530–532, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reilly M: Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire: General Health V2.0 (WPAI:GH). 2004. Available at: http://oml.eular.org/sysModules/obxOml/docs/ID_98/WPAI-GH_English_US_V2.pdf. Accessed November 12, 2019

- 41.Weisbord SD, Fried LF, Arnold RM, Fine MJ, Levenson DJ, Peterson RA, Switzer GE: Prevalence, severity, and importance of physical and emotional symptoms in chronic hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 2487–2494, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Flythe JE, Dorough A, Narendra JH, Forfang D, Hartwell L, Abdel-Rahman E: Perspectives on symptom experiences and symptom reporting among individuals on hemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 33: 1842–1852, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nochaiwong S, Ruengorn C, Awiphan R, Panyathong S, Noppakun K, Chongruksut W, Chiewchanvit S: Development of a multidimensional assessment tool for uraemic pruritus: Uraemic Pruritus in Dialysis Patients (UP-Dial). Br J Dermatol 176: 1516–1524, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bots CP, Brand HS, Veerman EC, Valentijn-Benz M, Van Amerongen BM, Valentijn RM, Vos PF, Bijlsma JA, Bezemer PD, Ter Wee PM, Amerongen AV: Interdialytic weight gain in patients on hemodialysis is associated with dry mouth and thirst. Kidney Int 66: 1662–1668, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. ClinicalTrials.gov: CR845-CLIN3103: A Global Study to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of CR845 in Hemodialysis Patients with Moderate-to-Severe Pruritus (KALM-2), 2018. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03636269?term=difelikefalin&draw=2&rank=6. Accessed November 12, 2019.

- 46.American Society of Nephrology; Kidney Health Initiaitve: Patient Reported Outcomes for Muscle Cramping in Patients on Dialysis Workgroup. Available at: https://khi.asn-online.org/projects/project.aspx?ID=79. Accessed on November 12, 2019

- 47.US Food and Drug Administration: Computerized Systems Used In Clinical Investigations. Guidance for Industry, 2007. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/media/70970/download. Accessed November 12, 2019

- 48.Huang IC, Revicki DA, Schwartz CE: Measuring pediatric patient-reported outcomes: Good progress but a long way to go. Qual Life Res 23: 747–750, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.