Abstract

BACKGROUND/OBJECTIVES

Physical distancing during the COVID‐19 pandemic may have unintended, detrimental effects on social isolation and loneliness among older adults. Our objectives were to investigate (1) experiences of social isolation and loneliness during shelter‐in‐place orders, and (2) unmet health needs related to changes in social interactions.

DESIGN

Mixed‐methods longitudinal phone‐based survey administered every 2 weeks.

SETTING

Two community sites and an academic geriatrics outpatient clinical practice.

PARTICIPANTS

A total of 151 community‐dwelling older adults.

MEASUREMENTS

We measured social isolation using a six‐item modified Duke Social Support Index, social interaction subscale, that included assessments of video‐based and Internet‐based socializing. Measures of loneliness included self‐reported worsened loneliness due to the COVID‐19 pandemic and loneliness severity based on the three‐item University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Loneliness Scale. Participants were invited to share open‐ended comments about their social experiences.

RESULTS

Participants were on average aged 75 years (standard deviation = 10), 50% had hearing or vision impairment, 64% lived alone, and 26% had difficulty bathing. Participants reported social isolation in 40% of interviews, 76% reported minimal video‐based socializing, and 42% minimal Internet‐based socializing. Socially isolated participants reported difficulty finding help with functional needs including bathing (20% vs 55%; P = .04). More than half (54%) of the participants reported worsened loneliness due to COVID‐19 that was associated with worsened depression (62% vs 9%; P < .001) and anxiety (57% vs 9%; P < .001). Rates of loneliness improved on average by time since shelter‐in‐place orders (4–6 weeks: 46% vs 13–15 weeks: 27%; P = .009), however, loneliness persisted or worsened for a subgroup of participants. Open‐ended responses revealed challenges faced by the subgroup experiencing persistent loneliness including poor emotional coping and discomfort with new technologies.

CONCLUSION

Many older adults are adjusting to COVID‐19 restrictions since the start of shelter‐in‐place orders. Additional steps are critically needed to address the psychological suffering and unmet medical needs of those with persistent loneliness or barriers to technology‐based social interaction.

Keywords: social isolation, loneliness, COVID‐19, older adults, technology

On March 16, 2020, San Francisco was the first county in the United States to institute shelter‐in‐place orders in addition to broader physical distancing recommendations. Although these orders have been credited with reducing the spread of COVID‐19, it is unclear whether such orders have had unintended consequences for older adults who may be uniquely vulnerable to experiencing social isolation and loneliness, two distinct markers of social well‐being. 1 , 2

Social isolation is an objective deficit in the number of relationships with and frequency of contact with family, friends, and the community. 3 By definition, shelter‐in‐place orders have isolated older adults to their homes, and this isolation might be greater for individuals who struggle to navigate video‐ and Internet‐based social interaction. Although social isolation may not be emotionally distressing for all, it is associated with medical risks, increased healthcare costs, and limited access to key caregiver, financial, medical, or emotional support during the pandemic. 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 In contrast, loneliness is a discrepancy between one's actual and desired level of social connection, and it is associated with depression, anxiety, functional disability, physical symptoms such as pain, and death. 3 , 5 , 6 , 8 , 9 During the COVID‐19 pandemic, many older adults may have experienced new or worsened feelings of loneliness due to a disruption of in‐person social activities that are often essential due to preexisting limitations from chronic medical conditions, vision or hearing impairment, or functional disability. 1 Social isolation and loneliness can exist separately, and it is not uncommon for them to coexist.

A better understanding of experiences of social isolation and loneliness among older adults during the COVID‐19 pandemic and health needs stemming from changes in social interaction is needed. Although many older adults may be successfully adjusting to social restrictions, more detailed information about older adults who may not be adapting to restrictions could guide evolving policies and strategies for supporting those who need more help. Moreover, a recent National Academy of Sciences report highlighted the need for clinicians to be aware of and actively address the health effects of social isolation and loneliness. 10 We therefore conducted a mixed‐methods study of community‐dwelling older adults primarily in the San Francisco and Bay Area during shelter‐in‐place orders. Our objectives were to (1) investigate experiences of social isolation and loneliness during shelter‐in‐place orders, and (2) examine unmet health needs related to changes in social interactions.

1. METHODS

1.1. Study Subjects and Design

We included participants from three sites to ensure a diverse sample: (1) University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) geriatrics clinical programs, (2) Covia Senior Services, and (3) the Curry Senior Center, with an overall response rate of 40%. The UCSF geriatrics programs included a sample of community‐dwelling adults (n = 79) receiving outpatient and home‐based care. Covia Senior Services is a nonprofit community program. Participants (n = 24) were recruited from two existing service programs: Well‐Connected and Social Call. Finally, we included older adults from the nonprofit Curry Senior Center (n = 48) within San Francisco's Tenderloin neighborhood, a socioeconomically and ethnically diverse area of the city. Eligible participants were community dwelling, aged 60 and older, and able to participate in a 15‐ to 45‐minute interview. We included participants speaking English, Spanish, Mandarin, Cantonese, and Russian with interviewers who were native speakers in the participant's primary language. Potential participants were excluded if they were unable to complete the consent process or if a prior diagnosis of cognitive impairment precluded them from consenting. Recruitment and baseline interviews were conducted over the phone by trained volunteers between April 8 and June 23, 2020, and follow‐up interviews were primarily conducted over the phone every 2 weeks, with few by mail or via e‐mail if preferred. Shelter‐in‐place orders were in place during the entire study time period. The study protocol and contents were approved by the UCSF institutional review board.

1.2. Social Measures

Several measures of social connections were included based on standard scales or adapted to measure social experiences during the coronavirus pandemic (Supplementary Table S1). We used a modified Duke Social Support Index social interaction subscale. 11 , 12 The six‐item scale includes the number of local contacts the participant feels close to or can depend on, the frequency of participation in community activities in the past week, and the frequency of social interaction (excluding interactions with co‐residents) via telephone, video, Internet, or in‐person communication, for a total range of 0 to 17 points. We categorized individuals as socially isolated if scoring 6 points or less on the 17‐point scale that represents minimal support or interaction from all sources. 13 , 14 Given the lack of consensus on an appropriate cutoff for social isolation, especially during the pandemic, we conducted sensitivity analyses of the social interaction scale both as a continuous variable and as a categorical variable with higher or lower cutoffs that yielded similar results (results available on request). In addition, we measured the frequency of communication with different social relationships (children or family, friends or neighbors, or volunteers).

Loneliness was measured in two ways. First, we assessed self‐reported change in loneliness by asking participants whether their feelings of companionship, feeling left out, or feeling isolated were “worse,” “about the same,” or “better” due to COVID‐19. Second, to measure the severity of loneliness, we used the three‐item University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Loneliness Scale (range = 0–6 points), categorizing 3 or more points on the scale as high loneliness. 15 , 16

1.3. Demographic and Clinical Measures

We measured several covariates to characterize the sample and that are relevant to social isolation and loneliness including age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, and financial stress (“In general, how do finances typically work out at the end of the month?”). 17 , 18 Health conditions included self‐reported diagnoses of depression, anxiety, hypertension, diabetes, non‐skin cancer, chronic lung disease, heart disease, or prior stroke. Functional impairment included self‐reported difficulty with bathing, preparing meals, shopping for groceries, medication management, and accessing transportation. 19

1.4. Medical Needs, Psychological Distress, and Open‐Ended Feedback

Participants were asked how worried they were about worsening health due to delayed medical care and about worries of food insecurity during the pandemic. 20 Individuals reporting functional impairment with bathing, preparing meals, shopping, medication management, or accessing transportation were asked if they had difficulty finding help with the task during the pandemic. Anxiety was measured using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder two‐item (GAD‐2) scale and by asking if these feelings changed due to coronavirus (“worse,” “same,” or “better”). 21 Depression was measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire‐2 (PHQ‐2) and asking if these feelings changed due to coronavirus (“worse,” “same,” or “better”). 22 Finally, we provided an opportunity for participants to share open‐ended thoughts or comments about the coronavirus pandemic; 77% participated (n = 115).

1.5. Analytic Approach

We analyzed available data on June 23, 2020. We conducted descriptive and bivariate statistics to characterize the social experience of older adults and the association with health access, medical needs, and psychological distress. We then assessed the change over time of social connection measures and loneliness since the start of shelter‐in‐place orders using random effects models to account for repeated measures within individuals. For qualitative analysis, all comments were reviewed using open coding in which themes that emerged repeatedly in the data were defined and saved as codes. After a set of preliminary codes was created, free‐text comments were then reviewed by each coder (A.K. and R.N.), and a constant comparative approach was used to finalize codes fitting concepts suggested by the data. The research team discussed codes to ensure reliable applications of the data. Themes and reported experiences of participants were compared with individual participants' UCLA Loneliness Scale scores at different time points.

2. RESULTS

2.1. Subjects

A total of 460 interviews were conducted with 151 participants. The mean age of our sample was 75 years (standard deviation = 10), 64% were female, 8% African American/Black, and 8% Asian (Table 1). Approximately 31% reported fair/poor hearing, 40% had fair/poor vision, 26% reported difficulty with bathing, and 35% difficulty shopping for groceries. Regarding social characteristics, 64% lived alone, 28% were widowed, 43% reported no close children, 10% had no close contacts, and 26% had only one to two close contacts.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Participants at Baseline (n = 151)

| Characteristics | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 75.3 (10.1) | |

| Sex | Female | 95 (65) |

| Male | 52 (35.4) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | Black/African American | 12 (8.2) |

| Latinx | 7 (4.8) | |

| Asian American or Pacific Islander | 12 (8.2) | |

| White/Caucasian | 102 (69.9) | |

| Multi‐ethnic | 8 (5.5) | |

| Other | 5 (3.4) | |

| Live alone | 94 (63.5) | |

| Marital status | Married/Partnered | 40 (28.4) |

| Divorced/Separated | 31 (22) | |

| Widowed | 39 (27.7) | |

| Never married | 31 (22) | |

| No. of close children a | None | 63 (42.9) |

| ≥1 children | 84 (57.1) | |

| No. of close contacts b | None | 14 (9.7) |

| 1–2 people | 38 (26.2) | |

| ≥2 people | 93 (61.6) | |

| Education | Less than high school | 6 (4.1) |

| High school/GED | 18 (12.2) | |

| Some college | 35 (23.7) | |

| Bachelor' s or higher+ | 89 (60.1) | |

| Financial stress, c | Usually some money left over | 71 (49.3) |

| end of month | Just enough to make ends meet | 47 (32.6) |

| Not enough to make ends meet | 18 (12.5) | |

| Declined/Not sure | 8 (5.6) | |

| Medical conditions, | Depression | 54 (35.8) |

| self‐reported | Anxiety | 57 (37.8) |

| Hypertension | 72 (47.7) | |

| Diabetes | 22 (14.6) | |

| Non‐skin cancer | 41 (27.2) | |

| Chronic lung disease | 19 (12.6) | |

| Heart condition | 36 (23.8) | |

| Prior stroke | 11 (7.3) | |

| Self‐rated hearing d | Fair/Poor | 46 (30.9) |

| Self‐rated vision d | Fair/Poor | 59 (39.9) |

| Difficulty with activities of daily living, Yes/No | Bathing | 38 (25.7) |

| Preparing meals | 35 (23.5) | |

| Shopping for groceries | 51 (34.5) | |

| Managing medications | 21 (14.1) | |

| Accessing transportation | 36 (24.2) |

Close children was determined by asking, “How many of your children would you say you have a close relationship with?”

Close contacts was determined by asking, “How many persons in your local area do you feel like you can depend on or feel close to?”

Financial stress was determined by asking, “In general, how do your finances usually work out at the end of the month?”

Self‐rated hearing and vision impairment was rated in five categories: excellent, very good, good, fair, and poor.

2.2. Social Connections

Participants reported levels of social interaction consistent with social isolation in 40% of study interviews (Table 2). Examining individual indicators, telephone interaction was the most common medium of social interaction (daily: 43%; 3 times per week: 28%). In contrast, there were low rates of weekly video‐based socializing (none: 46%; 1–2 times per week: 30%) and Internet‐based socializing (none: 26%; 1–2 times per week: 16%), with rates consistent by time since shelter‐in‐place. The overall rate of weekly community participation was 15%, and this rate increased with time since shelter‐in‐place (Week 4–6: 10% vs Week 13–15: 27%; P = .04). Individuals who were socially isolated were more likely to report difficulty finding help with functional needs, particularly bathing (55% vs 20%; P = .04) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Social Isolation and Loneliness Overall and by Time Since Shelter‐in‐Place (N = 460 Interviews)

| Overall | Time of interview since March 16 shelter‐in‐place orders | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weeks 4–6 | Weeks 7–9 | Weeks 10–12 | Weeks 13–15 | P value a | |||

| (N = 460) | (N = 108) | (N = 148) | (N = 131) | (N = 73) | |||

| Loneliness, % | |||||||

| Loneliness due to COVID‐19 b | Worse | 31 | 41 | 31 | 23 | 27 | .009 |

| Same or better | 70 | 59 | 69 | 77 | 73 | ||

| Severity of loneliness c | High | 29 | 36 | 29 | 23 | 28 | .58 |

| (≥3 points on UCLA scale) | |||||||

| Social connections and isolation, % | |||||||

| Overall social isolation d | Yes | 40 | 49 | 36 | 39 | 33 | .53 |

| (≤6 points on Duke scale) | No | 60 | 51 | 64 | 61 | 67 | |

| Types of social interaction d | |||||||

| In person | None | 33 | 40 | 36 | 31 | 22 | .77 |

| 1–2 times/week | 35 | 25 | 34 | 41 | 41 | ||

| ≥3 times/week | 20 | 17 | 19 | 18 | 29 | ||

| Daily | 12 | 18 | 11 | 10 | 7 | ||

| Telephone | None | 5 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 3 | .92 |

| 1–2 times/week | 24 | 24 | 21 | 28 | 25 | ||

| ≥3 times/week | 28 | 27 | 30 | 27 | 29 | ||

| Daily | 43 | 42 | 45 | 41 | 43 | ||

| Video | None | 46 | 53 | 45 | 44 | 38 | .64 |

| 1–2 times/week | 30 | 24 | 32 | 33 | 25 | ||

| ≥3 times/week | 14 | 12 | 14 | 12 | 24 | ||

| Daily | 10 | 10 | 8 | 11 | 13 | ||

| Internet | None | 26 | 36 | 21 | 24 | 26 | .41 |

| 1–2 times/week | 16 | 14 | 16 | 17 | 16 | ||

| ≥3 times/week | 23 | 20 | 22 | 32 | 17 | ||

| Daily | 35 | 40 | 41 | 28 | 41 | ||

| Interaction by relationship | |||||||

| Children or family | None | 13 | 16 | 13 | 12 | 10 | .43 |

| 1–2 times/week | 18 | 19 | 15 | 23 | 16 | ||

| ≥3 times/week | 24 | 23 | 28 | 19 | 29 | ||

| Daily | 34 | 29 | 34 | 39 | 32 | ||

| No children | 10 | 13 | 10 | 8 | 12 | ||

| Friends or neighbors | None | 17 | 23 | 17 | 17 | 7 | .87 |

| 1–2 times/week | 28 | 20 | 27 | 31 | 36 | ||

| ≥3 times/week | 27 | 24 | 28 | 25 | 33 | ||

| Daily | 27 | 31 | 28 | 26 | 20 | ||

| No friends | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Volunteers | None | 65 | 55 | 68 | 70 | 65 | .57 |

| 1–2 times/week | 22 | 29 | 18 | 20 | 24 | ||

| ≥3 times/week | 7 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 9 | ||

| Daily | 6 | 9 | 6 | 5 | 3 | ||

| Community participation e | None | 85 | 90 | 89 | 82 | 73 | .04 |

| (per week; range = 0 to ≥7) | ≥1 times | 15 | 10 | 11 | 18 | 27 | |

P values were determined based off random effects models accounting for repeated measures within individuals.

Loneliness due to COVID‐19 was determined by asking, “Because of the recent coronavirus outbreak (in the last 2 weeks), are your feelings of lack of companionship, being left out, or isolated?” (Responses: Worse, Better, the Same).

The severity of loneliness was assessed based on the three‐item UCLA Loneliness Scale with 3 or more points categorized as “high.”

Social isolation was measured using a six‐item modified Duke Social Support Index, social interaction subscale, including the number of local contacts the participant feels close to or can depend on, the frequency of participation in community activities in the past week, and the frequency of social interaction (excluding interactions with co‐residents) via telephone, video, Internet, or in‐person communication, for a total range of 0 to 20 points. Social isolation was categorized as 6 or fewer points.

Community participation was determined by asking, “In the past week, about how often did you go to meetings of clubs, religious meetings, or other groups that you belong to?”

Table 3.

Association of Social Isolation and Loneliness with Health and Health Access (N = 460 Interviews)

| Overall | Loneliness not worse a | Loneliness worse | No social isolation c | Social isolation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 460) | (N = 305) | (n = 135) | P value b | (N = 258) | (N = 169) | P value b | ||

| Psychological health, % | ||||||||

| Depression | Screen positive d | 24 | 17 | 42 | .001 | 24 | 25 | .43 |

| Worse e | 25 | 9 | 62 | <.001 | 30 | 19 | .27 | |

| Same | 67 | 81 | 36 | 64 | 72 | |||

| Better | 8 | 10 | 2 | 6 | 10 | |||

| Anxiety | Screen positive f | 26 | 17 | 46 | <.001 | 25 | 29 | .17 |

| Worse g | 24 | 9 | 57 | <.001 | 26 | 20 | .56 | |

| Same | 69 | 82 | 42 | 68 | 72 | |||

| Better | 6 | 9 | 1 | 6 | 7 | |||

| How worried are you about coronavirus? | Not at all worried | 12 | 14 | 7 | .002 | 9 | 18 | .26 |

| Somewhat worried | 19 | 21 | 11 | 18 | 18 | |||

| Moderately worried | 33 | 36 | 26 | 34 | 29 | |||

| Very worried | 25 | 19 | 38 | 28 | 21 | |||

| Extremely worried | 12 | 10 | 18 | 12 | 14 | |||

| Health care and function, % | ||||||||

| Are you worried about your health worsening due to delayed medical care? | Not at all | 55 | 62 | 39 | <.001 | 55 | 55 | .61 |

| Somewhat | 20 | 22 | 17 | 19 | 22 | |||

| Moderately | 15 | 12 | 22 | 14 | 15 | |||

| Very | 8 | 4 | 17 | 10 | 5 | |||

| Extremely | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Food insecurity h | Yes | 12 | 9 | 20 | .05 | 12 | 14 | .65 |

| Unable to find help with i | Bathing (n = 38) | 38 | 38 | 38 | .97 | 20 | 55 | .04 |

| Preparing meals (n = 35) | 27 | 20 | 35 | .34 | 20 | 31 | .47 | |

| Groceries (n = 51) | 20 | 9 | 30 | .08 | 15 | 23 | .52 | |

| Managing meds (n = 21) | 40 | 45 | 38 | .73 | 30 | 50 | .36 | |

| Transportation (n = 36) | 57 | 38 | 71 | .06 | 50 | 67 | .33 | |

Loneliness due to COVID‐19 was determined by asking, “Because of the recent coronavirus outbreak (in the last 2 weeks), are your feelings of lack of companionship, being left out, or isolated: (Responses: Worse, Better, the Same).”

The P values were determined based on chi‐square tests.

Social isolation was measured using a six‐item modified Duke Social Support Index, social interaction subscale, including the number of local contacts the participant feels close to or can depend on, the frequency of participation in community activities in the past week, and the frequency of social interaction (excluding interactions with co‐residents) via telephone, video, Internet, or in‐person communication, for a total range of 0 to 20 points. Social isolation was categorized as 6 or fewer points.

Screen positive for depression was determined based on the PHQ‐2.

Depression due to COVID‐19 was determined by asking, “Because of the recent coronavirus outbreak (in the last two weeks), are your feelings being down, depressed, or hopeless, or having little interest or pleasure doing things: (Responses: Worse, Better, the Same).”

Screen positive for anxiety was determined based on the GAD‐2.

Anxiety due to COVID‐19 was determined by asking, “Because of the recent coronavirus outbreak (in the last two weeks), is your ability to control worrying or feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge: (Responses: Worse, Better, the Same).”

Food insecurity was determined by asking, “Due to the coronavirus outbreak, have you been worried that your food may run out before you have a chance to buy more?”

Individuals were asked if they could not find help with an activity during the coronavirus pandemic only if they described an inability to do the activity independently.

In examining open‐ended responses, several participants reported successful use of technology to sustain connections with community activities and loved ones (Table 4), and that their relationships with technology changed during the pandemic as more services and interactions moved online or they were provided help:

Table 4.

Open‐Ended Responses on Social Connections During the COVID‐19 Pandemic

| Group | Theme | Illustrative quotations |

|---|---|---|

| Limited social interaction | Difficulty navigating technology | “Computer and I have been fight[ing] since the day I got it–it can be such a monster.” |

| “I answered ‘left out' because I do not have a working tablet to get on the Internet from my apartment.” | ||

| “I really wish I could use the computer . . . It's time I learn a little technology. I'll be stuck at home; the world will pass me by. All my friends are on the Internet.” | ||

| “There are always problems with cable and telephone and no to one to help with the problems.” | ||

| Difficulty getting help with functional needs | “The floors have not been washed in our hallways for 4 weeks, and cockroaches are spreading.” | |

| “I think social isolation has been overdone in San Francisco. Seniors need bus lines for transportation to carry out their own essential tasks that need to be completed” (go to the bank, get medications, maintain independence, catch a bus).” | ||

| “I'm starting to notice feeling more vulnerable from eyesight change . . . gives me a hurdle with going to a grocery store . . . especially with no busses in my neighborhood.” | ||

| Limited engagement with broader social network | “I only see my daughter, son‐in‐law, and two young grandchildren. I have not been out except to the garden, to take 30‐ to 45‐minute walks; I have not been in any shops. | |

| “I feel some sadness in knowing that both my age and the time this will take to stabilize might prevent me from ever traveling easily and freely again in my life. It is a reality that I have to accept.” | ||

| “I used to be around people all the time like going to church or grocery shopping. There is now no human contact because of the virus.” | ||

| Maintained social interactions | Technology | “I have learned more . . . [about] technology . . . I had opportunity to help other people through technology.” |

| “I am communicating more than ever, I have a new friend . . . I guess I want to say I am better with technology.” | ||

| “I do not like using technology but do because it is the means to communicate.” | ||

| “The majority of my activities and Drs. visits can be done by Zoom. I have help from granddaughter or others if I have a technology issue. I am trying to update my skills.” | ||

| Community engagement | “Zoom opportunities have substituted for some religious and exercise programs that I previously would attend in person.” | |

| “I do some Zoom stuff like Zoom exercise and book club.” | ||

| Finding Help | “I have great support through organizations like Curry Senior Center.” | |

| “The Healing Well is the agency that calls me every day and sends me things in the mail. That's a good thing.” |

“For technology, I think that has improved, I get tutoring a couple times a month from Curry [Senior Center].” (Interview No. 50; 6‐week follow‐up)

However, several participants mentioned either discomfort with technology or not having adequate access to the Internet or equipment that limited their social interactions.

“I am limited by not being comfortable on my iPhone for anything other than as a telephone, e‐mail, texts, and banking. It is my own fault so I get down on myself for that.” (Interview No. 162; 2‐week follow‐up)

Limited use of technology often led to an inability to engage with a broader social network and individuals being confined to interacting with family members or no one at all. Participants further described barriers in obtaining help with household chores, cooking, and accessing transportation (Table 4).

2.3. Loneliness

Overall, 54% of participants attributed worsened feelings of loneliness to the coronavirus pandemic at least once during the study period. The rate of reporting worsened loneliness declined by time of interview since shelter‐in‐place orders (4–6 weeks: 41% to 13–15 weeks: 27%; P = .009) (Table 2). Regarding psychological health, individuals reporting worsened loneliness were more likely to self‐report worsened depression due to COVID‐19 (62% vs 9%; P < .001) and screen positive on the PHQ‐2 (42% vs 17%; P < .001), as well as report worsened anxiety (57% vs 9%; P < .001) and screen positive for anxiety on the GAD‐2 (46% vs 17%; P < .001) (Table 3). In addition, participants with worsened loneliness reported being extremely or very worried about coronavirus (56% vs 29%; P = .002), worries about worsening health due to delays in medical care (21% vs 5%; P < .001), and food insecurity (20% vs 9%; P = .05) (Table 3).

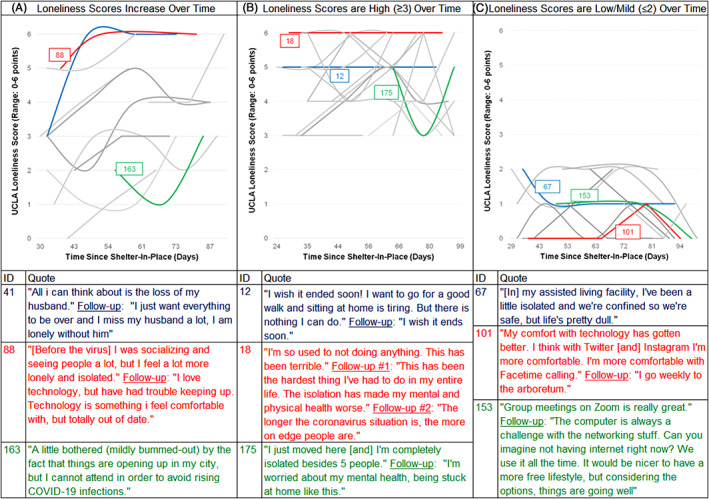

There was substantial diversity in the severity of loneliness over time (as measured by the UCLA Loneliness Scale) and open‐ended feedback among individual participants. We examined participants who reported worsened loneliness due to the coronavirus pandemic and who had at least two interviews during the study period (n = 63) (Figure 1). Among these participants, several experienced loneliness scores that increased in severity over time (n = 18 [28%]; Figure 1A) or loneliness scores that remained high over time (n = 27 [42%]; Figure 1B). In open‐ended responses, these individuals described COVID‐19 restrictions amplifying prior social losses (e.g., widowhood), difficulty using technology‐based alternatives to socializing, overwhelming feelings of being trapped, and loneliness affecting their physical and mental health:

“I have high anxiety. I don't get angry, but I cry easily. I've been locked up for this lockdown. I can't go to church. I have no one to talk to. [My] relationship is really rough right now. The virus is making it worse.” (Interview No. 91; average UCLA Loneliness Scale score: 6 points in three interviews)

This was accentuated by seeing city activities open up but feeling left out due to avoiding rising COVID‐19 cases. Even with nearby friends or family, certain participants wished for more unsolicited effort and companionship:

“I wish that my family who lived near me would call me. I have to call them and it doesn't feel good.”(Interview No. 98; average UCLA Loneliness Scale score: 3 points in three interviews)

Others reported worsened loneliness that was relatively mild over time (UCLA scores of 0–2 points) (n = 13 [21%]; Figure 1C). These participants reported a developing sense of boredom and dullness but managing their loneliness through keeping busy with activities at home and adopting new technologies.

Figure 1.

University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Loneliness Score trajectories among those who attributed worsened loneliness to COVID‐19 precautions. Participants included in the figure reported worsened loneliness due to the COVID‐19 pandemic at least once during the study period and had at least two interviews (n = 63). Participants were included in panels (A) “Loneliness scores increase” (n = 18) if UCLA Loneliness Scale scores increased on average in follow‐up interviews compared with baseline; (B) “Loneliness scores remain high” (n = 27) if all UCLA scores were 3 or higher; and (C) “Loneliness scores remain low” (n = 13) if all UCLA scores were 2 or lower. Worsened loneliness due to COVID‐19 was determined by asking, “Because of the recent coronavirus outbreak (in the last 2 weeks), are your feelings of lack of companionship, being left out, or isolated: (Responses: Worse, Better, the Same).” The severity of loneliness over time was then determined using the UCLA three‐item loneliness scale (range = 0–6 points), where 3 or more points corresponds with “high” loneliness. Colored lines show the loneliness trajectory corresponding with the participants' quotes.

Among participants with at least two interviews who never reported worsened loneliness due to COVID‐19 (n = 67), open‐ended feedback corresponded with two general subgroups. First, this included participants who were already isolated due to prior social deficits or functional impairments:

“Since I'm bedridden, my life has not been affected by this pandemic. My caregivers continue to come and assist me. I am grateful for that.”(Interview No. 147; average UCLA Loneliness Scale score: 0 points in four interviews)

Second, this included individuals who were adapting through appreciation of the quiet time, feelings of inclusion through technology, and positive emotional coping:

“It gave me time to know myself deeper. Living by yourself is a hard thing to do, when you are confined to a space all by yourself. When you're at home, your mind is idle and all your thoughts come out. Some can be negative and some can be positive, but you get to know yourself better and how to overcome that.” (Interview No. 102; average UCLA Loneliness Scale score: 0 points in five interviews)

3. DISCUSSION

In this longitudinal mixed‐methods survey of primarily community‐dwelling older adults, conducted during the most active phase of shelter‐in‐place orders, participants reported levels of social interaction consistent with social isolation in 40% of interviews. Technology‐based interactions have been widely assumed to alleviate forced isolation from shelter‐in‐place orders; however, nearly three‐quarters of study participants reported minimal or no video‐ and/or Internet‐based socializing with friends and family. In addition, more than half of participants reported heightened loneliness attributed to the COVID‐19 pandemic. Loneliness was strongly associated with concurrent worsening of depression, anxiety, worries about coronavirus, and worries about their general health. Results indicate that overall there was stability or improvement in loneliness over time, suggesting resilience and an ability to adapt among many older adults. However, a notable subgroup experienced persistent or worsened loneliness over time. Open‐ended feedback revealed challenges this subgroup of older adults may be experiencing with emotional coping. Moreover, comfort with and access to technology was often central to an ability to cope with restrictions, maintain social connections, or find help with medical needs. Taken together, results suggest that identifying those experiencing persistent loneliness or with barriers to technology‐based social interaction may be critical to addressing psychological suffering and unmet medical needs during the pandemic.

Nearly 4 in 5 older adults had minimal video interaction, and 2 in 5 had infrequent Internet‐based socializing with friends and family that contributed to high rates of social isolation in our study. These findings are consistent with prior literature on barriers to Internet use and communication technologies among older adults. 23 , 24 , 25 This digital divide is complex in that it may reflect both inadequate access to technologies or discomfort with available technologies. 26 Discomfort with technology might impact not only social interactions, but also accessing essential telehealth services, medication delivery programs, or technology‐based food delivery programs. 27 Our study found that social isolation was further associated with difficulty finding help with bathing, meal preparation, grocery shopping, and accessing transportation.

Consequently, identifying social isolation or deficits in social support may provide a gateway for identifying critical unmet needs among older adults. In the short term, we caution against an overreliance on technology‐based solutions for facilitating medical or social interactions because these may not be inclusive of many older adults with limited comfort or access to these options. 27 In these circumstances, clinicians may need to take the lead on making exceptions to allow in‐person interactions for older adults. This can complement messaging from public health and community organizations. However, most older adults had used video‐ or Internet‐based platforms to socialize at least once during shelter‐in‐place orders, and open‐ended feedback included enthusiastic stories of adopting new technologies for socializing or community participation. These findings point to the potential for novel or age‐friendly technological interventions among older adults, especially in situations where available classes, volunteers, family, or friends can facilitate the use of unfamiliar technologies. 23 , 24 , 28

Our study found overall declines in loneliness over time that is consistent with other surveys of older adults finding resilience to psychological distress during COVID‐19. 29 , 30 Important differences in the severity of loneliness over time and an ability to adapt were found among study participants that highlights the importance of understanding nuances of individual experiences of loneliness. Among individuals who experienced loneliness that worsened or remained severe over time, common themes from open‐ended feedback included an inability to cope emotionally, insufficient social support, and inadequate access or comfort with technologies for social interaction. In contrast, individuals who experienced no negative impact of the pandemic on loneliness reported the successful use of technology, positive emotional coping, and an ability to use city services (including senior center outreach, volunteer organizations, and services like Meals on Wheels) that is consistent with experiences in other parts of the country. 30 Notably, a minority of participants reported no difference in their loneliness during the pandemic because of already being isolated due to prior medical conditions (e.g., blindness, bedbound). In this sense, a lack of change during the pandemic reflected prior impairments rather than positive coping.

The diversity of experiences of loneliness suggest healthcare systems should conduct systematic assessments to identify the subgroup of individuals who are having a harder time adjusting to tailor outreach efforts. 29 , 31 Assessments of loneliness can provide a window into addressing the additional psychological distress, worries about health, and trauma that many are experiencing and perhaps not openly discussing with family, friends, or healthcare providers. A 2014 Institute on Medicine report suggested integrating psychosocial “vital signs” into the electronic health record (EHR). 32 , 33 The Berkman‐Syme Social Network Index and UCLA Loneliness Scale score are reasonable candidates for inclusion in the EHR during the COVID‐19 pandemic, and measures of social isolation should include assessments of the use of technology for social connections. 3

A recent National Academy of Sciences report on interventions to address loneliness and the health effects of social isolation demonstrated a large knowledge gap. 10 During the COVID‐19 pandemic, there is a particular need to address this knowledge gap by developing and testing interventions that do not rely on in‐person interactions. It may be reasonable to scale interventions for immediate health needs while concurrently developing the evidence base. For example, anecdotally, during the course of study interviews, research staff found participants wanted to discuss their social experiences because this in and of itself was therapeutic. Brief phone calls or inquiries about social isolation and loneliness during the pandemic may be feasible for primary care offices or community organizations, and they are often welcomed by older adults. 10 In addition, we suggest medical and health providers establish partnerships and referral networks to allow for “social prescribing” to local community‐based support programs. 10 , 34 , 35 Lastly, our study demonstrates that technology can be a powerful tool to help adults connect during periods such as the COVID‐19 pandemic. Yet overreliance on technologies can heighten or accentuate digital and socioeconomic divides. Before moving forward with technology‐based interventions during the pandemic, it is important to assess who the interventions aim to serve, who may be left out, and how to address these gaps.

Our study has several strengths. Although this study was primarily focused on residents of San Francisco, California, the diversity of our sample makes these results potentially applicable to other older adults throughout the United States. We conducted interviews over the phone, by e‐mail, and by postal mail that allowed us to be inclusive of older adults with vulnerabilities exacerbated by the pandemic including discomfort with technologies, functional impairment, hearing impairment, and vision impairment. Established relationships between community organizations and primary care clinicians further facilitated recruitment of participants who are traditionally excluded from studies.

Our study also has limitations. First, our sample size for quantitative analysis was limited in detecting statistically significant differences over time and by subgroups, although several notable differences emerged from the data. Second, we did not gather data on social measures and functional limitations before the start of shelter‐in‐place orders, so we cannot directly compare differences pre‐ and post‐pandemic. Lastly, recall and social desirability bias may have affected residents' reports of social interactions and well‐being.

In conclusion, the effect of the COVID‐19 pandemic on social isolation and loneliness among older adults has been mixed. Many have positively coped and adapted, whereas others have experienced worsened feelings of loneliness and an inability to adopt new technologies to facilitate social interaction. Identifying older adults experiencing sustained loneliness during the pandemic is critical to improving their overall well‐being. Moreover, our results raise the potential of age‐friendly technology to improve access to social interactions among older adults but caution against overreliance on technological solutions, especially in the short term among the most vulnerable in our communities. As the pandemic progresses, particularly given the recent increases in infections that are forcing reevaluation of public health policies, immediate interventions are needed to support the social well‐being of older adults to compensate for prolonged social restrictions.

Supporting information

Supplementary Table S1: Social Measures Included in the Survey

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to the staff at Curry Senior Center, Covia Senior Services, and UCSF medical student and pharmacy student volunteers who were responsible for data collection. We are extremely appreciative of study participants for their involvement.

Financial Disclosure

Ashwin A. Kotwal's effort on this project was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (K23AG065438; R03AG064323), the National Institute on Aging Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (No. P30AG044281), the National Palliative Care Research Center Kornfield Scholar's Award, and the Hellman Foundation Award for Early‐Career Faculty. Rebecca Newmark is supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences Medical Scientist Training Program (T32GM007618). This work was supported by a grant from the Metta Fund.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest for this article.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: All authors. Acquisition of the data: Kotwal, Holt‐Lunstad, Newmark, Cenzer, Escueta, Lee, and Perissinotto. Analysis and interpretation, drafting and revising the manuscript, and approval of the final manuscript: All authors.

Sponsor's Role

The sponsor had no role in the design, methods, data collection, analysis, or preparation of the article.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cudjoe TK, Kotwal AA. “Social distancing” amidst a crisis in social isolation and loneliness. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:E27‐E29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Steinman MA, Perry L, Perissinotto CM. Meeting the care needs of older adults isolated at home during the COVID‐19 pandemic. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:819‐820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Perissinotto C, Holt‐Lunstad J, Periyakoil VS, Covinsky K. A practical approach to assessing and mitigating loneliness and isolation in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:657‐662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cudjoe TK, Boyd CM, Wolff JL, Roth DL. Advance care planning: social isolation matters. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:841‐846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Holt‐Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, Harris T, Stephenson D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta‐analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10:227‐237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hoogendijk EO, Smit AP, van Dam C, et al. Frailty combined with loneliness or social isolation: an elevated risk for mortality in later life. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020. 10.1111/jgs.16716. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Oh A, Patel K, Boscardin WJ, et al. Social support and patterns of institutionalization among older adults: a longitudinal study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:2622‐2627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Perissinotto CM, Cenzer IS, Covinsky KE. Loneliness in older persons: a predictor of functional decline and death. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1078‐1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Abedini NC, Choi H, Wei MY, Langa KM, Chopra V. The relationship of loneliness to end‐of‐life experience in older Americans: a cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:1064‐1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Opportunities for the Health Care System. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Powers J, Goodger B, Byles J. Duke Social Support Index. Australian Longitudinal Study on Women's Health (ALSWH). Data Dictionary Supplement. 2004.

- 12. Pachana NA, Smith N, Watson M, McLaughlin D, Dobson A. Responsiveness of the Duke social support sub‐scales in older women. Age Ageing. 2008;37:666‐672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Steptoe A, Shankar A, Demakakos P, Wardle J. Social isolation, loneliness, and all‐cause mortality in older men and women. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110:5797‐5801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Strodl E, Kenardy J, Aroney C. Perceived stress as a predictor of the self‐reported new diagnosis of symptomatic CHD in older women. Int J Behav Med. 2003;10:205‐220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: results from two population‐based studies. Res Aging. 2004;26:655‐672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hawkley LC, Kocherginsky M. Transitions in loneliness among older adults: a 5‐year follow‐up in the national social life, health, and aging project. Res Aging. 2018;40:365‐387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Crawford LE, et al. Loneliness and health: potential mechanisms. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:407‐417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shah SJ, Krumholz HM, Reid KJ, et al. Financial stress and outcomes after acute myocardial infarction. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Katz S. Assessing self‐maintenance: activities of daily living, mobility, and instrumental activities of daily living. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1983;31:721‐727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gundersen C, Engelhard EE, Crumbaugh AS, Seligman HK. Brief assessment of food insecurity accurately identifies high‐risk US adults. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20:1367‐1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Plummer F, Manea L, Trepel D, McMillan D. Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD‐7 and GAD‐2: a systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;39:24‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Arroll B, Goodyear‐Smith F, Crengle S, et al. Validation of PHQ‐2 and PHQ‐9 to screen for major depression in the primary care population. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8:348‐353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Greysen SR, Garcia CC, Sudore RL, Cenzer IS, Covinsky KE. Functional impairment and internet use among older adults: implications for meaningful use of patient portals. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1188‐1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Levy H, Janke AT, Langa KM. Health literacy and the digital divide among older Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:284‐289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hunsaker A, Hargittai E. A review of Internet use among older adults. New Media Soc. 2018;20:3937‐3954. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Eghtesadi M. Breaking social isolation amidst COVID‐19: a viewpoint on improving access to technology in long‐term care facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:949‐950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lam K, Lu AD, Shi Y, Covinsky KE. Assessing telemedicine unreadiness among older adults in the United States during the COVID‐19 pandemic. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:1389‐1391. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zubatsky M, Berg‐Weger M, Morley J. Using telehealth groups to combat loneliness in older adults through COVID‐19. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:1678‐1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Luchetti M, Lee JH, Aschwanden D, et al. The trajectory of loneliness in response to COVID‐19. Am Psychol. 2020. 10.1037/amp0000690. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hamm ME, Brown PJ, Karp JF, et al. Experiences of American older adults with pre‐existing depression during the beginnings of the COVID‐19 pandemic: a multicity, mixed‐methods study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;28:924‐932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Reading Turchioe M, Grossman LV, Baik D, et al. Older adults can successfully monitor symptoms using an inclusively designed mobile application. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:1313‐1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Matthews KA, Adler NE, Forrest CB, Stead WW. Collecting psychosocial “vital signs” in electronic health records: why now? what are they? What's new for psychology? Am Psychol. 2016;71:497‐504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Institute of Medicine . Institute of Medicine Report: Capturing Social and Behavioral Domains in Electronic Health Records. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mulligan K, Bhatti S, Rayner J, Hsiung S. Social prescribing: creating pathways towards better health and wellness. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:426‐428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Savage RD, Stall NM, Rochon PA. Looking before we leap: building the evidence for social prescribing for lonely older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:429‐431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table S1: Social Measures Included in the Survey