Abstract

Objectives

Due to the time and cost effectiveness, online teaching has played a significant role in the provision of education and has been a well‐accepted strategy for higher education in the world. The aim of this study was to survey the current online undergraduate education status in dental medicine in mainland China during the critical stage of the COVID‐19 outbreak, as well to provide a better understanding of practicing this learning strategy for the improvement and development of dental education.

Methods

For the cross‐sectional survey, recruitment emails regarding to the implementation of online education were sent to 42 dental colleges and universities in mainland China between March and April 2020.

Results

Ninety‐seven percent of the respondents have opened online courses during COVID‐19 pandemic in China, 74% of which chose live broadcast as the major teaching way. As compared with theoretical courses, fewer specialized practical curriculums were set up online with a lower satisfaction from students in most dental schools. For the general evaluation of online learning from students of different dental schools, the “online learning content” received the highest support, while the “interaction between teachers and students” showed the lowest satisfaction. Most schools reported that the difficulty in assurance of students’ learning motivation was the main problem in online education.

Conclusions

Our findings indicate the necessity and efficacy of the overall online teaching for dental education during the epidemic that can be further improved with the education model and pedagogical means to boost the informationization of dental education for future reference.

Keywords: dental education, dental schools, massive open online courses, nationwide survey, online teaching

1. INTRODUCTION

With the rapid development of computer technologies and improvements in internet infrastructure, online education is becoming mainstream in the domain of modern world education. A Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) is an open online learning environment offering learners and tutors an open and continual form of networking beyond the limits of conventional online courses. 1 , 2 Since 2008, a large number of MOOCs were available on an ever‐growing array of subjects, with the most established online platforms reported to reach more than 101 million learners worldwide. 1 The incorporation of online elements in education could become the transformative pedagogy to help dental schools overcome many of the present challenges, such as a shortage of academic teachers, the increase in the number of students, and inadequate teaching resources. 3 Previous studies found that online education could improve time management, communication skills, critical thinking, and knowledge application beyond physical classroom boundaries. 4 , 5 With various tools and systems including telecommunication services, communications or social software, rich media in interactive training and learning, virtual learning environments, and virtual reality (VR), online teaching has delivered a broad array of solutions for the democracy of medical knowledge. 6 However, the shortcomings also exist in online education, and should be considered when planning for online courses in dental education. Researchers expressed concerns about online teaching limiting interactions and causing technical difficulties. 7 , 8 Besides, it would be difficult to conduct preclinical and clinical training using online education. To optimize dental education for the future, it is imperative to distinguish the factors that may affect the online teaching process and to keep in mind that educational need has priority over technological excellence.

Facing the rigid challenge posed by the current coronavirus COVID‐19 pandemic to school education, online teaching has been a well‐accepted strategy for higher education and engaged participants in beyond regional restrictions. It is particularly noteworthy that undergraduates are one of the important components of trans‐regional mobility in China. At present, there are 33.66 million college students in China, among whom 8.83 million are interprovincial students. 9 To ensure pandemic prevention and personnel flow control, colleges and universities postponed their schools’ openings. In the meantime, to keep continuous teaching and learning during the period, online education was implemented instead of traditional classroom teaching in more and more dental colleges and universities. Also, many dental schools opened teaching platforms to others and shared high‐quality online course resources, ensuring that the educational progress was not affected. Extensive geographic and professional coverage of the current online education makes possible a long‐distance imparting of knowledge and skills as a key solution for maintaining dental education in such complex and challenging environment.

Online education is ongoing and still confronted with severe challenge in dental colleges and universities. College teachers need to transform the method and content of teaching in classroom through systematic training and technical support. Besides, students’ learning attitudes and motivations are also essential factors in successful online learning. 10 Therefore, the aims of the present study were to (i) survey the overall implementation of online teaching in dental schools in mainland China using a nationwide evaluation feedback questionnaire; (ii) assess the dental school students’ evaluation of online education; and (iii) analyze the success and inadequacy in the practice of online dental education. Our findings will serve to better understand the positive role of online teaching in dental education, and provide detailed and valid data for improving the effectiveness of online teaching as well as exerting their potential impact on the in‐depth innovation and development of dental education.

2. METHODS

2.1. Participants

This study was approved by Academic Affairs Division, West China School of Stomatology, Sichuan University Institutional Review Board. This was a cross‐sectional online survey conducted on the research platform created and managed by universal questionnaire designer (www.wjx.cn) from March 16 to April 7, 2020. The platform's pool of participants consisted of 42 dental schools based on their geographical distribution and education assessment. And then, the undergraduates in these dental schools participating in online education were also recruited in this survey. The questionnaires were distributed and collected immediately after the survey by the researcher. Participant personal information including names was anonymized to maintain and protect confidentiality.

2.2. The questionnaire

A structured, self‐administered questionnaire was developed and consisted of questions that covered several areas: (1) the start time of online teaching during COVID‐19 outbreak; (2) the rates of students’ attendance; (3) the number of major courses offered online and satisfaction measurement of teachers and student; (4) the main way of online teaching and its web platform; (5) VR application for online dental education; (6) the use of electronic teaching material and students’ satisfaction measurement; (7) specific measures to ensure the online teaching quality in different dental schools; (8) the main challenge and difficulty of online dental education during COVID‐19 epidemic; (9) suggestions for promoting the development of higher education. For the students’ evaluations of online education, 6 criteria were included as following: (1) online learning content; (2) style of online teaching; (3) interaction between teachers and students; (4) arrangement of homework; (5) online learning materials; (6) effective time management.

2.3. Data analysis

The percentage of response was calculated according to the number of respondents per response with respect to the number of total responses of a question. And descriptive statistics was performed in this study. For the satisfaction measurement of teachers and students, we defined “highly satisfied” as score “5,” “satisfied” as score “4,” “general” as score “3,” “dissatisfied” as score “2,” and “very unsatisfied” as score “1,” respectively.

3. RESULTS

Of the 42 dental colleges and universities in mainland China that could participate in the survey, a total of 39 schools completed the questionnaire from March 16 to April 7, 2020, giving a 93% response rate. These schools are situated in 24 different provinces, covering in most parts of China (Table 1). Among them, a larger number of dental schools are located in the 4 provinces including Guangdong, Beijing, Shandong, and Shanghai. Given the survey results, after the Spring Festival, most dental schools (97%) have started online teaching since 10 February 2020. The total number of students participating in online education were 8740, from 68 to 900 in different dental schools, with more than 95% class attendance rates (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Students’ number and class attendance rate of online education in dental schools located in different provinces in this survey

| School no. | Situation (province) | Number of students | Rate of students’ attendance (%) | Start time (2020) | School no. | Situation (province) | Number of students | Rate of students’ attendance (%) | Start time (2020) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | Zhejiang | 270 | 100 | Feb 17 | #21 | Tianjin | 201 | 100 | Feb 17 |

| #2 | Jilin | 80 | 100 | Feb 24 | #22 | Guangdong | 280 | 96 | Mar 2 |

| #3 | Anhui | 300 | 100 | Feb 10 | #23 | Ningxia | 471 | 99.8 | Mar 2 |

| #4 | Liaoning | 200 | 100 | Feb 24 | #24 | Shanxi | 388 | 95 | Feb 17 |

| #5 | Chongqing | 228 | 100 | Feb 17 | #25 | Shanxi | 167 | 98 | Feb 17 |

| #6 | Beijing | 200 | 100 | Feb 17 | #26 | Guizhou | 388 | 96 | Feb 17 |

| #7 | Xinjiang | 82 | 100 | Feb 24 | #27 | Shandong | 220 | 100 | Feb 17 |

| #8 | Jiangsu | 200 | 100 | Feb 17 | #28 | Shanghai | 131 | 100 | Feb 28 |

| #9 | Xinjiang | 74 | 98 | Feb 24 | #29 | Shanxi | 68 | 100 | Mar 5 |

| #10 | Hubei | 82 | 100 | Feb 17 | #30 | Sichuan | 900 | 100 | Feb 24 |

| #11 | Shandong | 635 | 100 | Feb 24 | #31 | Jiangxi | 102 | 98.51 | Feb 17 |

| #12 | Shanghai | 144 | 100 | Mar 2 | #32 | Gansu | 413 | 99 | Mar 2 |

| #14 | Sichuan | 80 | 100 | Feb 24 | #33 | Beijing | 100 | 100 | Feb 17 |

| #15 | Hunan | 148 | 98.6 | Feb 24 | #34 | Liaoning | 69 | 99 | Mar 2 |

| #16 | Guangdong | 220 | 98.2 | Feb 17 | #35 | Shanghai | 209 | 100 | Mar 2 |

| #17 | Henan | 181 | 99.5 | Feb 10 | #36 | Beijing | 90 | 98 | Mar 16 |

| #18 | Gansu | 407 | 95 | Feb 12 | #37 | Fujian | 308 | 99 | Feb 17 |

| #19 | Tianjin | 73 | 100 | Feb 17 | #38 | Zhejiang | 200 | 98 | Feb 21 |

| #20 | Guangdong | 106 | 100 | Feb 17 | #39 | Shandong | 325 | 99.3 | Feb 17 |

As for the implementation of different types of online courses in dental colleges and universities, we analyzed the course number and student satisfaction for specialized theoretical courses, specialized practical courses, specialized compulsory courses, and specialized elective courses, respectively. First, as compared with specialized practical courses, more theoretical courses were set up online in most dental schools (Table 2). As shown in Table 2, 84% of dental schools have offered over 5 online specialized theoretical courses, while practical courses have not yet been set up in 60% dental schools. Second, similar circumstances occurred between specialized compulsory and elective courses. Although 5% of dental schools have not started specialized compulsory courses, 79% schools have opened more than 5 compulsory courses, among which 42% have offered over 10 courses for this kind online (Table 2). On the contrary, only 11% of schools have started more than 5 online specialized elective courses along with 39% not involved in these courses (Table 2). Third, undergraduates showed a generally positive attitude towards the implementation of the 4 types online courses. In particularly, 97% of dental school students expressed their overall satisfaction with specialized theoretical courses, whilst 3% felt dissatisfied with specialized practical curriculums (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

The percentage of different number of 4 types online curriculums offered by different dental schools

| Curriculum/number | 0 | 1∼5 | 5∼10 | >10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specialized theoretical courses | 0% | 16% | 42% | 42% |

| Specialized practical courses | 60% | 24% | 13% | 3% |

| Specialized compulsory courses | 5% | 16% | 37% | 42% |

| Specialized elective courses | 39% | 50% | 8% | 3% |

TABLE 3.

Assessment of students’ satisfaction for different types of online courses in dental colleges and universities

| Curriculum/satisfaction | Highly satisfied | Satisfied | General | Dissatisfied | Very unsatisfied |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specialized theoretical courses | 42% | 55% | 3% | 0% | 0% |

| Specialized practical courses | 18% | 68% | 11% | 3% | 0% |

| Specialized compulsory courses | 34% | 61% | 5% | 0% | 0% |

| Specialized elective courses | 31% | 61% | 8% | 0% | 0% |

Considering dental medicine is a major with strong practicality, specifically, we focused on the application of VR and electronic teaching materials in different dental colleges and universities. However, more than half of the dental schools have not yet started VR application online. And 45% of them conducted VR using ilab‐x.com platform along with other online courses. On the other hand, most school students (95%) have achieved universal access to electronic teaching materials with 75% satisfaction rate (including highly satisfaction).

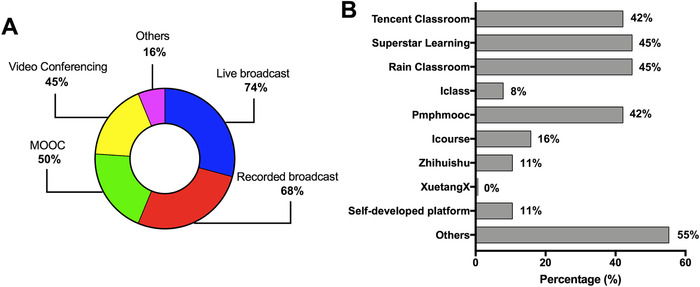

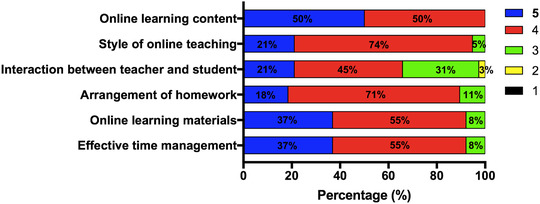

Teaching forms and methods are principal elements in online dental education. As shown in Figure 1A, the main way of online teaching in different dental schools included live broadcast (74%), recorded broadcast (68%), MOOC (50%), and video conferencing (45%). Meanwhile, various social software and web platforms were used in different dental schools. Superstar Learning (http://www.xuexi365.com), Rain Classroom (https://www.yuketang.cn/web), Tencent Classroom (https://ke.qq.com), and Pmphmooc (http://www.pmphmooc.com/#/home) were the most common software supporting the online dental education (Figure 1B). Besides these, DingTalk (https://www.dingtalk.com), Zoom Meeting (https://zoom.us), and Tencent Meeting (https://cloud.tencent.com/product/tm) are also very popular among different dental schoolteachers. According to the survey, most dental schools (76%) applied less than 4 types of online tools achieving 95% satisfaction rate from teachers, so the practice online teaching requirements could be satisfied sufficiently. Furthermore, to evaluate the effectiveness and efficacy of online education directly, we measured different dental school students’ satisfaction based on 6 points of view. As a result, all students showed highly satisfied or satisfied for the online learning content, which was followed by the style of online teaching, online learning materials, and effective time management (Figure 2). In contrast, only 66% dental school students expressed satisfaction (including highly satisfaction), while others showed negative attitude towards the interaction between teachers and students during online teaching time (Figure 2).

FIGURE 1.

Graphical representation of online teaching way and tools used in different dental colleges and universities. (A) Major online teaching methods used in different dental schools. (B) Distribution analytics of web platforms applied in online teaching in different dental schools

FIGURE 2.

Comprehensive evaluation of different dental school students’ satisfaction for online teaching. “Highly satisfied” was defined as score “5”; “satisfied” was as score “4”; “general” was defined as score “3”; “dissatisfied” was defined as score “2”; and “very unsatisfied” was defined as score “1”

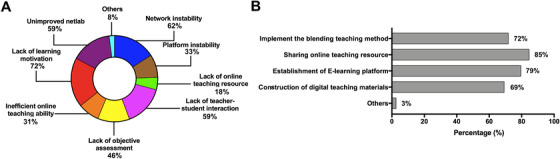

Furthermore, we collected viewpoints about the major difficulty and improvement suggestion for online dental education from different dental colleges and universities. Most respondents (72%) affirmed the poor learning initiative of students as the main influencing factor in the process of online dental education (Figure 3A). Next, network instability, unimproved network laboratory of stomatology, and lack of teacher‐student interaction were also important difficulties in online teaching that should not be ignored (Figure 3A). In addition, some dental schools reflected that other factors—including lack of objective teaching assessment, platform instability, and inefficient online teaching ability—might also affect the effectiveness of online dental education. Despite many challenges in current online teaching, dental schools in China took various measures proactively to ensure teaching quality, such as establishment of Tencent QQ groups and WeChat groups for the feasibility of the in‐phase question‐answering teaching system in the distance education. To further push forward the development of dental education reform, most dental schools suggested sharing online teaching resource, establishment of e‐learning platform, implementation of blending teaching method, and construction of digital teaching materials as the feasible strategies for reference (Figure 3B).

FIGURE 3.

Viewpoints about the major difficulty (A) and improvement suggestion (B) for online dental education collected from different dental colleges and universities

4. DISCUSSION

This investigation revealed a positive attitude toward online teaching among different dental colleges and universities during the epidemic in China. A majority of the respondents started setting online courses during the COVID‐19 outbreak and appreciated the convenience and necessity of online education in terms of time flexibility and online attendance. However, the implementation of different types of online courses were inconsistent in different dental schools. In particular, at this moment, specialized practical courses have not yet opened online in most dental schools. For students in their preclinical years, the transition from in‐person to online learning might affect their operation training. With the help of videos and role‐plays while simultaneously practicing on real patients immediately after completing online course may help to strengthen students’ dental practical skills. For students in clinical training, online modules cannot completely replace hospital‐based learning. But this is a transition period of crisis time, and presumably dental schools will find ways to obtain clinical exposure for senior medical students. 11

Recently, VR technologies are widely incorporated into dental education, teaching, and training. Moreover, VR has been described as the learning aid of the 21st century. 12 A previous study suggested that students could retain more information and better apply what they had learned after participating in VR exercises. 13 Considering the potential learning enhancement through VR use, many dental colleges and universities offered VR experiment teaching online using public platform or intra‐school network system. Sophisticated simulations and VR, such as DentSim© (http://www.denx.com/), encouraged students to learn and refresh the new and existing cognitive skills required during diagnosis and treatment. 5 , 14 However, haptic technology such as Simodont, which is critical to enhance the simulated experiences and to promote the transfer of students’ clinical skills to real‐life situation, could not be applied in online education in the current situation.

It was obvious that teachers lectured online in different ways and a wide diversity of web platforms were chosen in different online courses. As Schoenwetter et al. 3 reported, communications or social software tools such as email, wikis, newsgroups, Second Life, and Facebook could enhance collaborative learning and encourage interactions between teachers and students. Among them, Second Life and Open Wonderland with virtual environment could enhance students’ participation in a 3D environment. 15 Most software surveyed in this study, such as Superstar Learning and Tencent Classroom, could provide professional mobile learning platform for mobile terminals including smartphones and tablets. In the present study, some of the social software or web platforms were developed to meet the urgent needs of online teaching and specific to China during COVID‐19 pandemic. In this case, there might be a limitation of reference value for readers outside China. The global opening and sharing of online teaching software still needs more time and practice. However, there is at present little knowledge as to the selection of the ideal online teaching mode and software in order to study students’ engagement and learning behaviors through clickstream data. It is worth noting that more online teaching tools can provide richer user experience, but also increase more learning adaptive difficulty. Challenges may arise and result in limited quality control relating to the deficient ability to integrate existing content into different online tools. 16 , 17 Although there is a certain risk of bias in the selection of online teaching platform and software, some significant differences will be further identified among the achievement and performance in each cluster based on the aims of the study in future research. 18 Also important is the provision of methods for objective quantification of student performance and standardization to gauge and optimize the efficacy of different teaching methods.

For the students’ evaluations of online education, among 6 criteria included in this investigation, “interaction between teachers and students” showed the lowest satisfaction, indicating that teacher‐student interactive communication was limited by online teaching mode to some degree. To resolve this problem and achieve the desired effect of online education, various measures such as double type teachers in each online course, and problem‐based learning (PBL) implemented in online teaching, should be taken in different dental colleges and universities. PBL originated on constructivist conceptions of learning and successfully developed in various fields of medical education. 19 , 20 In PBL, students need to be in charge of their learning and coordinate the group learning as a whole, which will effectively promote the teacher‐student and student‐student communication such as construction of a shared goal and collaborative planning. 21 , 22 However, it is challenging to capture and support PBL with current online platforms as they require time and efforts to help teachers offer better support for students based on teaching demands.

According to the survey results, the major problem in online dental education was the uncertainty of students’ learning motivation in different dental schools. It's important for teachers to find out what students most care about and hope to get from the online course. The invitation of students’ engagement and feedback will offer instructors ideas for online teaching and give students ownership of the learning process. 23 Considering the fact that teachers cannot see each student's face during online teaching time, it is impossible to tell if they understand the content actually. Therefore, interactive elements such as short quizzes, random questions, and effective teamwork will help to ensure the online teaching effectiveness. Besides, conduction of frequent assessments by phone, text, or e‐mail with each student, especially with those who are struggling, are also tips for stimulating students’ enthusiasm for online learning.

5. CONCLUSION

Our findings demonstrated that online teaching represents a valid and reliable measure in most dental colleges and universities during the COVID‐19 outbreak in China. In particular, specialized theoretical online courses offered significant potential for dental education. However, online education still need to be further improved in consistent with the disciplinary characteristics of stomatology, including instructional design of online course, individualized tracking, technical monitoring, professional support, and specialized assessment. Such measures will help to evaluate the efficacy of online dental education and to provide guidance for the dental educators of the future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the 8th New Century Higher Education Reform Project of Sichuan University under grant SCU8370. All authors declare no conflicts of interest in this study.

Wang K, Zhang L, Ye L. A nationwide survey of online teaching strategies in dental education in China. J Dent Educ. 2021;85:128–134. 10.1002/jdd.12413

REFERENCES

- 1. Skiba DJ. Disruption in higher education: massively open online courses (MOOCs). Nurs Educ Perspect. 2012;33(6):416‐417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kaplan AM, Haenlein M. Higher education and the digital revolution: about MOOCs, SPOCs, social media, and the Cookie Monster. Bus Horiz. 2016;59(4):441‐450. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schoenwetter D, Reynolds PA, Eaton KA, De Vries J. Online learning in dentistry: an overview of the future direction for dental education. J Oral Rehabil. 2010;37(12):927‐940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lahti M, Kontio R, Pitkänen A, et al. Knowledge transfer from an e‐learning course to clinical practice. Nurse Educ Today. 2014;34(5):842‐847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sezer B. Faculty of medicine students’ attitudes towards electronic learning and their opinion for an example of distance learning application. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;55(PartB):932‐939. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Feeney L, Reynolds PA, Eaton KA, Harper J. A description of the new technologies used in transforming dental education. Br Dent J. 2008;204:19‐28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fadlelmola FM, Panji S, Ahmed AE, et al. Ten simple rules for organizing a webinar series. PLoS Comput Biol. 2019;15(4):e1006671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Knipfer C, Wagner F, Knipfer K, et al. Learners’ acceptance of a webinar for continuing medical education. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;48(6):841‐846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang C, Cheng Z, Yue X, McAleer MJ. Risk management of COVID‐19 by universities in China. J Risk Financial Manag. 2020;13(2):36. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sun PC, Tsai RJ, Finger G, Chen YY, Yeh D. What drives a successful e‐learning? An empirical investigation of the critical factors influencing learner satisfaction. Comput Educ. 2008;50(4):1183‐1202. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stokes DC. Senior medical students in the COVID‐19 response: an opportunity to be proactive. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27(4):343‐345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Papanikolaou I, Haidopoulos D, Paschopoulos M. Changing the way we train surgeons in the 21th century: a narrative comparative review focused on box trainers and virtual reality simulators. Eur J Obstet Gyn R B. 2019;235:13‐18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Krokos E, Plaisant C, Varshney A. Virtual memory palaces: immersion aids recall. Virtual Real (London). 2019;23(1):1‐15. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wagner IV, Ireland RS, Eaton KA. Digital clinical records and practice administration in primary dental care. Br Dent J. 2008;204:387‐395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Eaton KA, Reynolds PA, Grayden SK, Wilson NHF. A vision of dental education in the third millennium. Br Dent J. 2008;205:261‐271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Feeney L, Reynolds PA, Eaton KA, Harper J. A description of the new technologies used in transforming dental education. Br Dent J. 2008;204:19‐28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Reynolds PA, Eaton KA, Mason R. Seeing is believing: dental education benefits from developments in videoconferencing. Br Dent J. 2008;204(2):87‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lan M, Hou X, Qi X. Self‐regulated learning strategies in world's first MOOC in implant dentistry. Eur J Dent Educ. 2019;23(3):278‐285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Savery JR, Duffy TM. Problem based learning: an instructional model and its constructivist framework. Educ Technol. 1995;35:31‐38. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Neville AJ. Problem‐based learning and medical education forty years on. Med Princ Pract. 2009;18(1):1‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mohammed S, Jalal N, Henriikka V, Malmberg J. What makes an online problem‐based group successful? A learning analytics study using social network analysis. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Järvelä S, Järvenoja H, Malmberg J, et al. Exploring socially shared regulation in the context of collaboration. J Cogn Educ Psychol. 2013;12:267‐286. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gewin V. Into the digital classroom: five tips for moving teaching online as COVID‐19 takes hold. Nature. 2020;580(7802):295‐296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]