Abstract

Objective

(1) To give adolescents and youth a voice and listen to the impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) in their lives; (2) to identify their coping strategies; (3) present lessons learned to be better prepared for future pandemics.

Methods

Six hundred and seventeen participants from 16 to 24 years old (M = 19.2 years; F = 19.1 years) answered the online questionnaire during the pandemic lockdown. Sociodemographic data were analyzed with SPSS version 26 and qualitative data with MAXQDA 2020. Engel's Biopsychosocial model supported the analysis and data presentation.

Results

in terms of impacts, stands out: biological—headaches and muscle pain; psychological—more time to perform pleasant and personal development activities, but more symptoms of depression, anxiety, and loneliness, longer screen time, and more substance use; social—increase of family conflicts and disagreements, loss of important life moments, contacts, and social skills, but it allows a greater selection of friendships. Regarding coping strategies, the importance of facing these times with a positive perspective, carrying out pleasurable activities, keeping in touch with family and friends, and establishing routines are emphasized. As lessons for future pandemics, the importance of respecting the norms of the Directorate‐General for Health, the need for the National Health System to be prepared, as well as teachers and students for online learning, and studying the possibility of establishing routines with the support of television.

Conclusions

This study illustrates adolescents and young people's perception of the impacts of the pandemic upon them, as well as their competence to participate in the issues that directly affect them. Priorities to mitigate the impact of future pandemics are presented.

Keywords: adolescent and youth participation, COVID‐19, pandemic, Portugal, qualitative research, voice

1. INTRODUCTION

Declared a pandemic on March 11, 2020 (WHO, 2020), coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) is currently responsible for thousands of deaths worldwide. Consequently, social confinement became mandatory, affecting the entire population, including adolescents and young people (AYA). The COVID‐19 confinement has affected AYA's physical, mental, and emotional well‐being (The Lancet Child Adolescent Health, 2020). Moreover, deprived of the traditional teaching model, with the closure of schools and universities, online‐learning was the methodology adopted by numerous countries (Golberstein et al., 2020). These public health measures, although necessary, can not only impact the health and well‐being of young people but can also affect their development, as a result of the restricted face‐to‐face relationships with their peer group; the cancellation or plans postponement; the uncertainty about the future; and the potential threat that the virus may pose to themselves and their family (The Lancet Child Adolescent Health, 2020). Moreover, the mental health impact of the economic recession cannot be ignored and may be cumulative.

A study conducted in China, the first country to be confronted with the outbreak, showed a greater tendency for psychological problems and posttraumatic stress in the young people surveyed (Liang et al., 2020).

A study focused on psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the pandemic in China, found that being female, a student, having specific physical symptoms, such as muscle tension or dizziness, and self‐rating poor health was significantly associated with a higher psychological impact and higher levels of stress, anxiety, and depression (Wang et al., 2020). Frequent contact with colleagues, calm and psychological resilience were highlighted as protective factors (Song et al., 2020).

At the physical level, in an investigation focused on the effects of the outbreak on young people's lifestyles, a decrease in physical activity, with an increase in sedentary behavior predominated by screen time, was reported (Xiang et al., 2020).

Contrary to other studies that consider the female gender to be more vulnerable to traumatic or stressful life events, Cao et al. (2020) did not find differences by gender. However, young people do experience an increase in psychological and physical symptoms during their physical and pubertal development (Matos & Equipa Aventura Social, 2019).

1.1. Why involve young people in the issues that affect them?

According to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989), the voice of young people should be valued. Studies such as Research Into Child In Europe argue that listening to them is fundamental to identify their true needs (Ottova et al., 2013). Moreover, 6C—Contribution of Lerner (Lerner, 2004) is considered a fundamental right of young people (UNICEF, 2011) yet numerous decisions related to young people's lives are still taken without any input from young people themselves (Branquinho et al., 2016; Matos et al., 2015).

Based on the principle that young people can contribute with important knowledge related to their problems and needs (Ozer & Piatt, 2017), based on their voice and experience (Cammarota & Fine, 2008; Kim, 2016; Livingstone et al., 2014), AYA's participation can be an important resource during and after COVID‐19. Acknowledging that young people can be a target but also a resource for change (Zeldin et al., 2007), makes them a potential agent of change (Checkoway & Gutiérrez, 2006).

With this argument and curious to know what they think and experience during the COVID‐19 pandemic, but also to help health and educational professionals to be better prepared to meet the future needs of AYA, a study focused on their voice related to the impact on social and friendly relationships, on daily life and routines, on health and well‐being and differences on sex, age, and socioeconomic status (SES) is presented. To understand the impact on their generation, identifies their coping strategies and lessons for future pandemics. A general comparative study of their discourse regarding gender and education level will also be presented, allowing to analyze if the female gender is more vulnerable to stressful life events (Cao et al., 2020) and if adolescents experience more physical and psychological symptoms when compared to young adults since they are in the period of pubertal development (Matos & Equipa Aventura Social, 2019).

2. METHODS

2.1. Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the Order of Portuguese Psychologist (OPP, 2020). Informed consent (own or guardian if under 18) was described in the instrument, with mandatory acceptance to proceed. There was also a contact for further clarification.

2.2. Design and participants

To engage and capture AYA's perspectives of the pandemic and future strategies, a survey was designed for AYA. The questionnaire was disseminated through the research team contacts, including social networks, e‐mails, and with the support of the OPP, Portuguese Institute of Sport and Youth and Cascais Municipality. Data collection was carried out from April 14, 2020 to May 18, 2020.

In total, 674 responses were collected in this qualitative study, but after the elimination of incomplete answers, 617 responses were considered (nonprobability sampling). It is thus a merely convenience sample, basically gathered at a one‐to‐one basis starting from the team's previous contacts with young AYA organizations.

2.3. Instrument

Aimed at AYA aged between 16 and 24 years, this online questionnaire included sociodemographic questions, along with eight open‐response questions, centered on the impact of the outbreak on AYA's social life and friendships; their routines and daily life, including school, work, and leisure time; well‐being and health; coping strategies and lessons to deal with future pandemics. Analysis of differences in responses by gender and school level were explored. The questionnaire took an average time of 15–20 min to complete in full.

2.4. Methods

An analysis of the sociodemographic data was performed using descriptive statistics, using the quantitative analysis software SPSS version 26.

After exporting all the responses to a text document, an initial content analysis was carried out. In the search for a model that could support the results’ presentation, the Biopsychosocial model of Engel (1980) was considered the best fit.

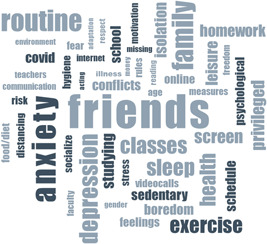

The qualitative data were coded and processed using MAXQDA 2020. Even though manual content analysis techniques are considered valid and necessary to analyze any type of data, it is believed that the addition of computer‐assisted qualitative data analysis (MAXQDA) can make the results more trustworthy (Souza et al., 2015) and the process more transparent (Woods et al., 2016). After the first round of analysis, the data were studied based on the rule of thumb principle and based on a word cloud for checking the most frequent words in the document: 50 of the most common words (grouped by synonyms, ignoring prepositions, and conjunctions) and uttered more than 20 times (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Word cloud depicting the 50 most common words of the voice of adolescent and young people related to the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic

After studying the most frequent concepts to find the key thematic areas, the terms were grouped by similarity in categories: (C1) impact on social life and friendly relationships; (C2) impact on daily life and routines; (C3) impact on health and well‐being; (C4) differences in the impact on sex, age, and SES; (C5) coping strategies; (C6) lessons for future pandemics and integrated into subcategories related to their impact on AYA: “positive,” “negative,” or “neutral.” Regarding the type of content, coping strategies, analysis of differences (gender, age, and SES) and lessons for future pandemics were not included in the subcategories.

To understand the different priorities in the discourse of both genders and levels of education, a study of the 10 most frequent words in each group was carried out, followed by their contextualization in the text.

A project memorandum was used to ensure greater detail in the presentation of the work developed.

3. RESULTS

Participants had an average age of 19.1 years, (SD = 2.352; min = 16; and max = 24); the majority were female (69.5%); of Portuguese nationality (95.1%), living in the region of Lisbon and Tagus Valley (64.3%), where the country's capital is located; were students (74.2%), attending university (38.7%), or secondary school (35.8%).

The data were analyzed by categories, starting with the analyses of the impacts on social life and friendships. In this, young people refer that pandemic can cause loss of contacts; decrease interpersonal skills; that made it impossible to live moments and events that they have planned; as well as increase feeling of distrust towards others. In rebuttal of the negative effects, AYA points out that this pandemic will allow us to give more value to friendship and strengthen relationships.

In turn, on the impact on daily life and routines, they said that their days are monotonous and boring; the absence of a routine; lower productivity and procrastination; and the interference in the practice of physical activity by athletes. On the positive points, stand out that now they have more time to perform pleasurable activities; the online‐learning; initiation to physical exercise and enjoy more of their parents’ company.

In terms of health and well‐being, physical symptoms (head and muscle pain) and psychological symptoms (e.g., depression, anxiety, and irritability) are mentioned, as well as, changes in sleep pattern and weight, also due to changes in physical activity; higher screen time and substance use; propensity for more fights and discussions with a possible increase in the rate of domestic violence and divorces; more homework; and not being able to sunbathe. On the other hand, they emphasize the least fatigue and the opportunity for personal growth. One of the AYA also points out that he has not lived as happy times as this with his school closed.

In the differences of sex, age, and SES, the AYA emphasize that there no gender differences; that adolescents and senior and most affected; and that people with low SES are most affected by the outbreak, as they have less financial, space and technology resources.

After studying the impacts, the impacts, the coping strategies were identified. In this category, young people pointed out regular communication with friends and family through video calling; perform pleasurable activities; face this period in a calm and positive way; and have a routine with set times.

Lessons for future pandemics, include how it is important to value freedom because you never know when you can be deprived of it; the importance of following the guidelines of the Directorate‐General for Health; that the National Health System must be prepared and equipped for outbreaks; teachers and students must be trained for online teaching; and that maintaining a routine is fundamental. Television can be seen as a resource in establishing healthy routines (e.g., physical activity schedules, programs with healthy eating recipes before usual meal times, evening programs aimed to the whole family) (See Table 1).

Table 1.

Categories, subcategories, and key‐ideas

| Categories | Positive | Negative | Neutral |

|---|---|---|---|

| Impact on social life and friendly relationships |

|

|

|

| Impact on daily life and routines |

|

|

|

| Impact on health and well‐being |

|

|

|

| Differences in impact on sex, age, SES |

|

||

| Coping strategies |

|

||

| Lessons for future pandemics |

|

||

Abbreviation: SES, socioeconomic status.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

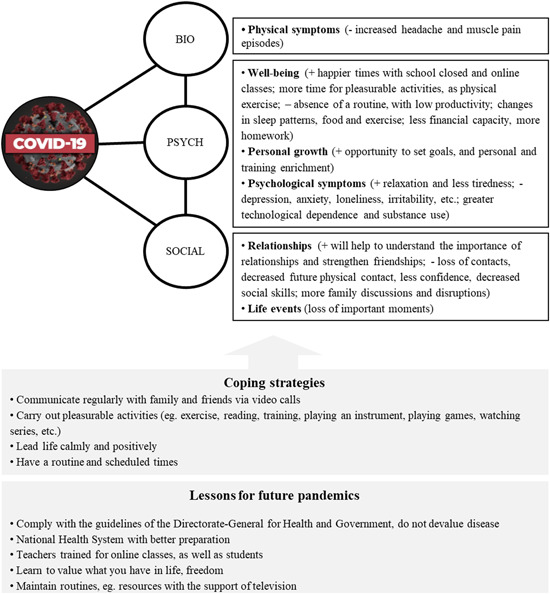

In a summary of the results, based on the adaptation of Engel's Biopsychosocial model (1980), the positive and negative impacts of the COVID‐19 on AYA are presented, focused on their voice, as well as the coping strategies identified and lessons (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Summary of the results based on the adaptation of the Biopsychosocial model

The initial analysis in the “gender” group (see Table 2) showed that although the level of prioritization of topics is different, the same was reported by both (e.g., friends, anxiety, routine, family, exercise, depression, classes, health, and sleep). The responses were similar between females and males except for “homework,” and the large amount of homework sent by teachers, which was reported more by the female gender, and “privileged,” associated with greater ease for the most privileged to cope with the pandemic, highlighted predominantly by males.

Table 2.

Comparison of key concepts between groups—sex and educational level

| Order | Female | Male | Secondary | University |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Friends | Friends | Friends | Friends |

| 2 | Anxiety | Family | COVID | Anxiety |

| 3 | Routine | Exercise | Distance | Routine |

| 4 | Family | Routine | Communication | Family |

| 5 | Exercise | Anxiety | Family | Exercise |

| 6 | Depression | Classes | Miss | Classes |

| 7 | Classes | Depression | Affection | Depression |

| 8 | Health | Sleep | School | Sleep |

| 9 | Sleep | Health | Conviviality | Health |

| 10 | Homework | Privileged | Fear | Privileged |

Note: bold means the different prioritization (number of times in the comments) of themes in the speech of both genders.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

In turn, in the group “education level” (see Table 2), even though “friends” occupies the first place in the discourse for both levels, and “family” is also a common word, all other terms differ between secondary (COVID, distance, communication, miss (someone), affection, school, conviviality, and fear) and third‐level education (anxiety, routine, exercise, classes, depression, sleep, health, privileged). Secondary school students highlight the impacts on friendship relationships (distance from friends that translate into homesickness, changes in habits, and ways of socializing with friends), constant contact with parents, the importance of communicating regularly with family and friends, and fear that their family will be infected. While university students report permanent family time, alongside the repercussions on physical and psychological health, as well as on education. Also, university students highlight the issue of greater facilitation of the higher SES in dealing with the virus, as found in young men.

In coping strategies and lessons for future pandemics, the discourse of both genders and educational levels are similar.

Based on the categories and subcategories identified, exemplary excerpts from the speeches of young women and men who attend secondary or higher education are presented (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Example of excerpts in each of the categories

| C1—Impact on social life and friendly relationships |

| Positive—"Social withdrawal strengthens friendships, real ones last." (18 years old, M, University); “… It is helping to strengthen friendly relationships.” (18 years old, F, Secondary); “… People are beginning to understand the importance of social life and relationships with others.” (19 years old, F, Secondary) |

| Negative—“Being in the 12th year, I am missing many moments that I waited for this year, whether be the finalists' trip or the ball or just being able to say goodbye to the secondary as I thought…” (17 years old, F, Secondary); "Being afraid to hug and kiss the people I love." (18 years old, M, Secondary); "It can decrease the simplicity of the personal touch." (20 years old, M, University) |

| Neutral—“Given the fact that my generation was born online, communication and friendship are not being affected…” (16 years old, F, Secondary); “Relationships remain healthy…” (18 years old, M, Secondary); “… I didn't have a very active social life, and what I do now (speaking on social media or occasionally called) was what I was doing before.” (24 years old, F, University) |

| C2—Impact on daily life and routines |

| Positive—"In a very positive way, the time I have is perfect for investing in me, in my development, organizing the life that was previously on the run and taking the opportunity to be with those who share the same roof." (19 years old, F, University student); “I spent most of my daily life away from home now. I try to find more time for myself and my closest family…” (18 years old, M, Secondary); “… Online classes are going really well!!!” (17 years old, F, Secondary) |

| Negative—“I used to have 4 volleyball training sessions per week and despite maintaining physical exercise, it is undoubtedly what I miss most…” (17 years old, F, Secondary); “We are overwhelmed with schoolwork.” (16 years old, F, Secondary); “… When someone arrives from the street, whether from work or a “simple” trip to the supermarket, it's paranoid until everything is disinfected.” (17 years old, F, Secondary) |

| Neutral—“I don't feel particularly affected… I try to occupy my days, and I don't think much of the time that is left until the social distance ends…” (18 years old, F, University student); “… I do almost everything I did before, but at home.” (16 years old, F, Secondary); “…. I try to have a normal life as a student, study, eat, wash, clean, exercise, sleep.” (21 years old, M, University student) |

| C3—Impact on health and well‐being |

| Positive—“…. I've never been as happy as I am now, with schools closed.” (16 years old, F, Secondary); “Physically, I even find positive points, I can rest more, study, watch my series, play sports, eat well…” (19 years old, F, University); “… Increased comfort by always being at home and allowing remote work.” (23 years old, M, university) |

| Negative—"I feel depressed." (20 years old, F, Secondary); "I feel more alone and isolated." (19 years old, M, University); "There is strong insecurity about economic instability and the future, generating anxiety and stress." (24 years old, M, University) |

| Neutral—"It's not really affecting me." (22 years old, F, Secondary); “… I follow my life normally.” (18 years old, F, Secondary); "At the moment it doesn't affect me because I am not infected, but if that happened, it would be quite serious, as I am a person at risk." (19 years old, F, Secondary) |

| C4—Analysis of the impact of differences between sex, age, and SES |

| "It is difficult for everyone." (17 years old, F, Secondary); “…. More difficult for older people who received visits from their children/grandchildren and now conform to a simple call/video call.” (18 years old, F, University); “I think that there are no differences between genders…”(20 years old, M, University); “… I believe that it is more costly for the younger ones than for the older ones since their lives revolve around people they don't live with (colleagues, friends, teachers, boyfriends, etc.)…” (20 years old), F, University); “Whoever has more economic power shouldn't have so much trouble distracting himself during this time…” (17 years old, M, Secondary) |

| C5—Coping strategies |

| “Try to maintain routines,” (22 years old, M, University); “… Try to sunbathe and exercise regularly.” (20 years old, F, University); “I try to occupy my time with tidying up, studying, learning new music on the guitar, cooking, making video calls.” (17 years old, F, Secondary); “… Participate in online courses/training.” (20 years old, F, University); “Try to maintain positivity…” (23 years old, M, University) |

| C6—Lessons for future epidemics |

| “Investing more in the National Health System…” (16 years old, M, Secondary); “…. I've never been so proud of being a Portuguese! I think schools closed at the right time, the state of emergency came into force at the right time, people respected (albeit with some exceptions that are part of) the state's requests to stay home and respect the rules of social distance…” (16 years old, F, Secondary); “We must give MUCH MORE VALUE to small moments…” (16 years old, F, Secondary); “Respiratory etiquette is the most important…” (20 years old, F, University); “Promote a routine on television…” (23 years old, M, University student); “… Train teachers in the area of online classes.” (18 years old, F, University) |

Abbreviation: SES, XXX.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

4. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

This study explored the Voice of young Portuguese regarding the impacts of COVID‐19 in their generation, along with coping strategies and lessons for future pandemics. The impacts of COVID‐19 were grouped in three categories: (i) impact on social life and friendly relationships, (ii) impact on daily life and routines, and (iii) impact on health and well‐being, and results were considered on behalf of the biopsychosocial perspective (Engel, 1980).

AYA expressed more physical symptoms, such as headaches and muscle pain, associated with a less active life, which is consistent with studies on the outbreak of COVID‐19 in China (Wang et al., 2020). The report of more symptoms of depression, anxiety, and loneliness seen in this study, has also been found in other studies (Liang et al., 2020; Pereira et al., 2020; Qiu et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). Longer screen time and more substance use during the COVID‐19 pandemic were also referred by AYA. In a study developed by Xiang et al. (2020), longer screen time was also mentioned. However, participants also reported benefiting from more time to perform pleasurable (e.g., do physical exercise, painting, and reading) and personal development activities, as online courses in their areas of interest.

Regarding the social impact, participants reported the loss of social competencies related to less contact with others and relevant life moments, such as final academic year celebrations, like the prom and finalists' trip and other family parties. In fact, literature already identified not only the health and well‐being impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic, but also the influence on AYA's development as a result of the reduced face‐to‐face relationships with their peer group, the cancellation or postponement of plans, and the uncertainty about the future (The Lancet Child Adolescent Health, 2020).

Though Wang et al. (2020) reported female gender as more vulnerable to the psychological impact of the COVID‐19, our study also showed a higher prioritization of the words “anxiety” and “depression” by females, when compared to males. In addition to the physical and psychological impacts, they say that the outbreak brought financial difficulties to family life. In a review of the socioeconomic implications of the pandemic, its impacts on the primary, secondary, and tertiary sectors are recognized, with a consequent loss of jobs (Nicola et al., 2020).

They agree that the outbreak has altered their pattern of sleep, food, and exercise and that the change in routines decreases their productivity. Abbas et al. (2020) support these results, arguing that stress can affect behavioral mechanisms, leading to greater food intake, reducing the practice of physical activity, and impairing the quality of sleep. They are also unanimous that online classes have brought a greater burden of homework.

In the study of the education level, although both emphasize the fact that they are permanently with the family, sometimes resulting in episodes of conflict, their voice diverges. Confinement led to an organization of daily life, forcing the whole family to deal with stress and social detachment (Fegert et al., 2020).

It is common for AYA in secondary education to highlight the impact of the pandemic on friendly relationships and the fear that their family will be infected; while university students report the repercussions of the outbreak on physical and psychological health, as well as on education. In a policy brief published by the United Nations (2020), focused on the need for action on mental health, are reported physical distance from friends, fear of infection by the family, along with the effects on physical and psychological health.

They also mention that it is easier for people with high SES to deal with the current situation since they have outdoor leisure areas and resources such as consoles and computers to occupy their time.

In coping strategies and lessons for future pandemics, speeches are similar among AYA of both genders and educational levels. In coping strategies, the importance of regular communication with family and friends; conduct training and pleasurable activities; having a routine with defined times; and try to live calmly and positively, are highlighted. Easily integrated into the 3C model—Control, Coherence, and Connectedness (Reich, 2006), which explains resilience in stressful situations. Shared resilience at the global level is advocated as crucial to meeting this challenge (Vinkers et al., 2020).

The high interest and participation of AYA in the present study confirms that they want to be heard, and they want to be actively engaged in decisions that are related to AYA and with the current global situation. In a testament to their competence and in an attempt to raise awareness among stakeholders and bodies of political power regarding the importance of (truly) including AYA in the issues that affect them, their strategies for future pandemics are presented: the need to follow the guidelines of the Directorate‐General for Health is highlighted; better preparedness by the National Health System to deal with outbreaks; teachers and students suitable for an online teaching methodology; maintaining routines using audiovisual media such as television; and learn to value freedom.

5. STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

Regarding limitations, and due to the characteristics of this current time of isolation, all the participants answered an online questionnaire, which made it impossible to deepen the themes under analysis with each of the AYA and to obtain nonverbal information that could trigger more information obtained that is usually acquired through a qualitative search. Second, the sample was constructed by female participants, which in fact is a regular limitation in psychosocial literature. However, the study aimed to compare the most reported impacts and considering the high number of participants, we believe that the findings were not biased by the uneven gender composition. Last, the impossibility to compare these results with similar studies.

Despite the outlined limitations, several strengths must be noted. First, and to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to give a voice to AYA. In this sense, not only did we search for the COVID‐19 pandemic and consequently confinement impact on AYA's lives but the study also focused on understanding their coping strategies and illustrated lessons for the future. Second, considering the knowledge raised here, we hope that future pedagogical and therapeutic programs can be more suitable for AYA need in times of global crises. Also, the conveyed information aims to be useful for the present coronavirus pandemic which is far away from the end, and political, educative, and health actions must be taken to decrease its negative effects on AYA. Third, the content analysis was developed bearing transparent (Woods et al., 2016) and reliable (Souza et al., 2015) qualitative research standards, namely by using a qualitative data analysis software (MAXQDA). Also, the search systematically searched for positive, but also for negative and neutral cases regarding the impact of the pandemic on AYA's lives. Fourth, the high response rate of AYA to this study allows some confidence in the generalization of the results to the representative population. Finally, the present study aimed to have participants of different ages and levels of education to analyze different perspectives regarding the same problematic and to better address the findings.

6. KEY MESSAGES AND PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

Lockdown due to the COVID‐19 pandemic has obliged AYA to stay at home, have e‐classes from home, and in general seeing family too much and friends too little. The educational system must be prepared for a distance learning model, ensuring that it is operational and accessible to all students, regardless of their specific health, education, or economic needs.

As the situation follows there is an urgent need to address the needs reported by AYA (e.g., increased training of teachers and students for online‐learning; a load of homework adapted to the new context; health professionals supporting the establishment of healthy routines) that were raised by the pandemic situation, and to establish a routine that can foster positive effects and mitigate negative ones.

Regarding the impact on psychological health, even though the means of psychological support were quickly deployed, it is important to highlight the importance of including or increasing support resources in schools or higher education institutions.

AYA voices describe both positives and negative outcomes, both from a personal, a social, and an environmental perspective. Realizing the ability of AYA to identify their problems and needs, the importance of their voice, and their participation in the issues that directly affect them are highlighted.

As the situation follows there is an urgent need to address the needs reported by AYA (e.g., increased training of teachers and students for online learning; a load of homework adapted to the new context; health professionals supporting the establishment of healthy routines) that were raised by the pandemic situation, and to establish a routine that can foster positive effects and mitigate negative ones.

The present work is of utmost importance for public policies in the area of AYA's physical, psychological, social, and academic well‐being.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1002/jcop.22453.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Aventura Social Team, Order of Portuguese Psychologists, Portuguese Institute of Sport and Youth, and Cascais Municipality for their support in the data collection phase.

Branquinho C, Kelly C, Arevalo LC, Santos A, Gaspar de Matos M. “Hey, we also have something to say”: a qualitative study of Portuguese adolescents’ and young people's experiences under COVID‐19. J Community Psychol. 2020;48:2740–2752. 10.1002/jcop.22453

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, Cátia Branquinho.

REFERENCES

- Abbas, A. M. , Fathy, S. K. , Fawzy, A. T. , Salem, A. S. , & Shawky, M. S. (2020). The mutual effects of COVID‐19 and obesity. Obesity Medicine, 19, 100250. 10.1016/j.obmed.2020.100250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branquinho, C. , & Matos, M. G. , Equipa Aventura Social . (2016). Dream Teens: Uma geração autónoma e socialmente participative [Dream Teens: An autonomous and socially participative generation]. In Pinto A. M., & Raimundo R. (Eds.), Avaliação e Promoção das Competências Socioemocionais em Portugal (pp. 421–440). Coisas de Ler. [Google Scholar]

- Cammarota, J. , & Fine, M. (2008). Revolutionizing education: youth participatory action research in motion. Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, W. , Fang, Z. , Hou, G. , Han, M. , Xu, X. , Dong, J. , & Zheng, J. (2020). The psychological impact of the COVID‐19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Research, 287, 112934. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Checkoway, B. N. , & Gutiérrez, L. (2006). Youth participation and community change: An introduction. Journal of Community Practice, 14(1‐2), 1–9. 10.1300/J125v14n01_01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Engel, G. L. (1980). The clinical application of the Biopsychosocial model. American Journal of Psychiatry, 137, 535–544. 10.1176/ajp.137.5.535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fegert, J. M. , Vitiello, B. , Plener, P. L. , & Clemens, V. (2020). Challenges and burden of the coronavirus 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: A narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 14, 20. 10.1186/s13034-020-00329-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golberstein, E. , Wen, H. , & Miller, B. F. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) and mental health for children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatrics, 174, 1–2. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. (2016). Youth involvement in Participatory Action Research (PAR): Challenges and barriers. Critical Social Work, 17(1), 38–53. [Google Scholar]

- The Lancet Child Adolescent Health . (2020). Pandemic school closures: Risks and opportunities. The Lancet. Child & Adolescent Health, 4, 341. 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30105-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, R. M. (2004). Liberty: thriving and civic engagement among American youth. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, L. , Ren, H. , Cao, R. , Hu, Y. , Qin, Z. , Li, C. , & Mei, S. (2020). The effect of COVID‐19 on youth mental health. The Psychiatric Quarterly, 91, 1–12. 10.1007/s11126-020-09744-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone, A. , Celemencki, J. , & Calixte, M. (2014). Youth participatory action research and school improvement: the missing voices of black youth in Montreal. Canadian Journal of Education, 37(1), 283–307. [Google Scholar]

- Matos, M. G. , Branquinho, C. , Tomé, G. , Camacho, I. , Reis, M. , Frasquilho, D. , Santos, T. , Gomes, P. , Cruz, J. , Ramiro, L. , Gaspar, T. , Simões, C. , & Equipa Aventura Social . (2015). Dream teens ‐ Adolescentes autónomos, responsáveis e participantes, enfrentando a recessão em Portugal. Revista de Psicologia da Criança e do Adolescente, 6(2), 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Matos, M. G. , Equipa Aventura Social . (2019). A Saúde dos Adolescentes Portugueses após a Recessão: Dados Nacionais 2018 [The Health of Portuguese Adolescents after the Recession: National Data 2018]. Equipa Aventura Social. [Google Scholar]

- Nicola, M. , Alsafi, Z. , Sohrabi, C. , Kerwan, A. , Al‐Jabir, A. , Iosifidis, C. , Agha, M. , & Agha, R. (2020). The socio‐economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID‐19): A review. International Journal of Surgery, 78, 185–193. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordem dos Psicólogos Portugueses (OPP) . (2020). Via Verde de Apoio â Investigação Científica [Green Way to Support Scientific Research]. http://mkt.ordemdospsicologos.pt/vl/c99af3a1e25f8a973cd3addbc76ac59b91af0bdb0eoVe0e16M0e

- Ottova, V. , Alexander, D. , Rigby, M. , Staines, A. , Hjern, A. , Leonardi, M. , Blair, M. , Tamburlini, G. , Gaspar de Matos, M. , Bourek, A. , Köhler, L. , Gunnlaugsson, G. , Tomé, G. , Ramiro, L. , Santos, T. , Gissler, M. , McCarthy, A. , Kaposvari, C. , Currie, C. , … The RICHE Project Group . (2013). Report on the roadmaps for the future, and how to reach them. http://doras.dcu.ie/19732/1/WP4_D8_RICHE_Roadmap.pdf

- Ozer, E. J. , & Piatt, A. A. (2017). Adolescent participation in research: Innovation, rationale and next steps. Innocenti Research Briaf, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, M. , Oliveira, L. , Costa, C. , Bezerra, C. , Pereira, M. , Santos, C. , & Dantas, E. (2020). The COVID‐19 pandemic, social isolation, consequences on mental health and coping strategies: an integrative review. Research, Society and Development, 9(7), e652974548. 10.33448/rsd-v9i7.4548 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, J. , Shen, B. , Zhao, M. , Wang, Z. , Xie, B. , & Xu, Y. (2020). A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID‐19 epidemic: Implications and policy recommendations. General Psychiatry, 33(2), 19–21. 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich, J. (2006). Three psychological principles of resilience in natural disasters. Disaster Prevention and Management, 15, 793–798. 10.1108/09653560610712739 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song, K. , Xu, R. , Stratton, T. D. , Kavcic, V. , Luo, D. , Hou, F. , Bi, F. , Jiao, R. , Yan, S. , & Jiang, Y. (2020). Sex differences and psychological stress: Responses to the COVID‐19 epidemic in China. MedRxiv, 10.1101/2020.04.29.20084061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza, D. N. , Costa, A. P. , & Souza, F. N. (2015). Desafio e inovação do estudo de caso com apoio das tecnologias [Challenge and innovation in the case study with the support of technologies]. In de Souza F. N., de Souza D. N., & Costa A. P. (Eds.), Investigação Qualitativa: Inovação, Dilemas e Desafios (pp. 143–162). Ludomedia ‐ Conteúdos Didácticos e Lúdicos. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF . (2011). Every Child's Right to be Heard: a resource guide on the un committee on the rights of the child general comment no.12. https://www.unicef.org/french/adolescence/files/Every_Childs_Right_to_be_Heard.pdf

- United Nations. (2020). Policy Brief: COVID‐19 and the Need for Action on Mental Health. https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/un_policy_brief-covid_and_mental_health_final.pdf

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) . 1989. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. https://downloads.unicef.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2010/05/UNCRC_united_nations_convention_on_the_rights_of_the_child.pdf

- Vinkers, C. H. , van Amelsvoort, T. , Bisson, J. I. , Branchi, I. , Cryan, J. F. , Domschke, K. , Howes, O. , Manchia, M. , Pinto, L. , de Quervain, D. , Schmidt, M. V. , & van der Wee, N. J. A. (2020). Stress resilience during the coronavirus pandemic. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 35, 12–16. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2020.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C. , Pan, R. , Wan, X. , Tan, Y. , Xu, L. , Ho, C. S. , & Ho, R. C. (2020). Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) epidemic among the general population in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(5), 1729. 10.3390/ijerph17051729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods, M. , Paulus, T. , Atkins, D. P. , & Macklin, R. (2016). Advancing qualitative research using Qualitative Data Analysis Software (QDAS)? Reviewing potential versus practice in published studies using ATLAS.ti and NVivo, 1994‐2013. Social Science Computer Review, 34(5), 597–617. 10.1177/0894439315596311 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) . (2020). Rolling updates on coronavirus disease (COVID‐19). https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen

- Xiang, M. , Zhang, Z. , & Kuwahara, K. (2020). Impact of COVID‐19 pandemic on children and adolescents' lifestyle behavior larger than expected. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases, 20, 30096–30097. 10.1016/j.pcad.2020.04.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeldin, S. , Camino, L. , & Calvert, M. (2007). Toward an understanding of youth in community governance: Policy priorities and research directions. Análise Psicológica, 25(1), 77–95. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, Cátia Branquinho.