Abstract

Background

Approaches in malaria risk mapping continue to advance in scope with the advent of geostatistical techniques spanning both the spatial and temporal domains. A substantive review of the merits of the methods and covariates used to map malaria risk has not been undertaken. Therefore, this review aimed to systematically retrieve, summarise methods and examine covariates that have been used for mapping malaria risk in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA).

Methods

A systematic search of malaria risk mapping studies was conducted using PubMed, EBSCOhost, Web of Science and Scopus databases. The search was restricted to refereed studies published in English from January 1968 to April 2020. To ensure completeness, a manual search through the reference lists of selected studies was also undertaken. Two independent reviewers completed each of the review phases namely: identification of relevant studies based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines, data extraction and methodological quality assessment using a validated scoring criterion.

Results

One hundred and seven studies met the inclusion criteria. The median quality score across studies was 12/16 (range: 7–16). Approximately half (44%) of the studies employed variable selection techniques prior to mapping with rainfall and temperature selected in over 50% of the studies. Malaria incidence (47%) and prevalence (35%) were the most commonly mapped outcomes, with Bayesian geostatistical models often (31%) the preferred approach to risk mapping. Additionally, 29% of the studies employed various spatial clustering methods to explore the geographical variation of malaria patterns, with Kulldorf scan statistic being the most common. Model validation was specified in 53 (50%) studies, with partitioning data into training and validation sets being the common approach.

Conclusions

Our review highlights the methodological diversity prominent in malaria risk mapping across SSA. To ensure reproducibility and quality science, best practices and transparent approaches should be adopted when selecting the statistical framework and covariates for malaria risk mapping. Findings underscore the need to periodically assess methods and covariates used in malaria risk mapping; to accommodate changes in data availability, data quality and innovation in statistical methodology.

Keywords: systematic review, malaria, review, geographic information systems, control strategies

Summary box.

What is already known?

The disproportionate decline of malaria risk overtime and between/within countries in sub-Saharan Africa attributed to biological, environmental, social and demographic factors has triggered a renewed interest in its fine-scale epidemiology.

Enhanced computational ability and availability of data of high quality and volume has enabled the quantification malaria risk burden in space and time leading to the proliferation of methods within a formal statistical framework.

The complexity of spatio-temporal models has increased, making inferential and predictive processes difficult to undertake.

What are the new findings?

The production of more granular estimates of malaria risk hinges on accessibility to and collection of timely data at finer resolutions.

Variable selection should be objectively developed to contribute to the maximum predictive accuracy of the spatio-temporal model.

What do the new findings imply?

Spatio-temporal approaches need to robustly quantify the sub-national burden of malaria risk, as an epidemiological prerequisite to intervention strategies.

Investments in primary data collection at subnational scales, development and continuous application of robust modelling tools and approaches will be important for orienting malaria control and elimination efforts in the next decade.

As the malaria landscape diversifies, new tools will be required to not only highlight changes locally, but also to provide evidence-based insights into factors driving the change.

Introduction

Global efforts to control and eliminate malaria are intrinsically linked to the Sustainable Development Goals.1 Specifically, the Global Technical Strategy (GTS) for Malaria (2016–2030) reiterates the need to reduce both malaria case incidence and mortality rates by up to 90%2 in high burden countries, mostly concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), and eliminating malaria in at least 35 countries and preventing resurgence in malaria-free countries.2 However, in 2018, SSA had an estimated 213 million clinical episodes of malaria, caused mainly by Plasmodium falciparum parasite3. To address this high burden, the GTS emphasises on the need to target interventions according to subnational disease risk stratification.2

The importance of malaria risk mapping in Africa can be traced back to the mid-1950s when malaria epidemiology formed a critical prelude to the design of interventions aimed at eliminating malaria.4 A resurgence in malaria cartography emerged in the 1990s,4–6 coinciding with an era of intensive control and elimination activities. Over the last 20 years, national and subnational malaria risk maps have been developed in many endemic countries in SSA.4 7 8 This has led to a proliferation of methods and an increase in data quality and quantity—prompted by the demands for robust and reliable characterisation of malaria risk in space and time.

The science of malaria cartography has evolved from hand-drawn risk maps to contemporary digital maps due to the demand for computational solutions and methodologies. These are needed to produce accurate estimates at a high spatial and temporal resolution to facilitate monitoring elimination progress within and between countries in SSA.8 Modern mapping embracing novel statistical techniques at high spatial and temporal resolution are increasingly being used to inform public health policy.9 10 Most recently, this has been aided by the availability of curated spatial databases, geographical information systems, enhanced computational capabilities and the advancement in spatial statistics. Standardised nationally representative survey initiatives, such as the geolocated Malaria Indicator Survey and the Demographic and Health Survey platforms, have availed geocoded malaria data with relevant covariates.11 12 This has enabled the characterisation of malaria risk at a high spatial resolution over which health policy is made.

Previous reviews have been conducted to; identify environmental risk factors of malaria transmission,11 13 summarise methodological and computational power advancement.12 Despite the increase in the number of malaria risk mapping studies, there are no recent and comprehensive reviews of the changes in methodological frameworks and covariates used. Consequently, we aimed to identify and review malaria risk mapping studies, to assess analytical methods and covariates used in the last five decades.

Methods

The protocol guiding this review has been previously published.14 Our results are reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.15 16 A notable deviation from our protocol was limiting the review scope to SSA where the burden of malaria is highest and countries have broadly similar malaria vector and parasite ecologies and health system contexts, compared with low-income and middle-income countries.3 17 A rigorous three-phase process was undertaken to transparently identify and summarise spatio-temporal studies based on their methodical framework and covariates employed used in malaria risk mapping.

Phase 1: Identification of relevant studies/keyword search.

Search terms and databases

All studies published between 1 January 1968 and 30 April 2020 were systematically searched through four electronic databases (PubMed, Web of Science, EBSCOhost and Scopus) using search terms defined in online supplemental table 1. To improve the search strategy, thematically mined keywords were funnelled using Boolean operators and truncations before being employed across the selected electronic reference databases. The starting year (1968) corresponded to the year when the first global audit of malaria endemicity was undertaken.5 12 Relevant studies were imported into Endnote, version X9 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA) (online supplemental table 1).

bmjgh-2020-002919supp001.pdf (27.5KB, pdf)

Phase 2: Study selection

Studies were screened independently by two authors JNO and CK for possible inclusion based on information provided in the title and abstract. Relevant studies based on the research questions were subsequently appraised on their eligibility for full-text review. The full-text review entailed the application of a more stringent inclusion/exclusion criteria for selecting studies to be included for data extraction. Additional papers were identified by examining the reference lists of retrieved studies and by contacting the authors where necessary. Emerging discrepancies were resolved by consensus and by an independent arbitrator (BS). A comprehensive and pilot tested form was used for data extraction.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Peer-reviewed studies that employed spatial, temporal and spatio-temporal modelling techniques in malaria risk mapping in SSA were considered. A spatial model was defined as one that explicitly included a geographical index, while a temporal model included a time index. Studies using at least one visualisation or modelling technique (with or without covariates) for assessing the burden of malaria were included. Commentaries, expert reviews and/or reports that did not include original research were read, and only relevant studies cited included.

Phase 3: Data extraction

A standardised extraction form was used to independently extract the data by two reviewers (JNO and CK). The tool was first piloted and refined accordingly. Discordance between the reviewers with respect to the information extracted was resolved by consensus and by consulting with an independent arbitrator (BS). For each selected study, the following information was extracted (online supplemental table 2) namely:

bmjgh-2020-002919supp002.pdf (223.4KB, pdf)

Bibliographic information (Author, year, study setting and period, primary unit of analysis, spatial and temporal resolution).

Study objective(s)

Data aspects (data sources, malaria data, covariate type)

Analytical method (modelling approach(es), assumptions, cluster detection techniques, statistical tests, diagnostic/validation checks).

Results and discussions (key findings, modelling gaps, recommendation(s)).

Quality assessment

A previously used 8-point scoring criteria18 was adapted and modified to assess the quality of the individual studies based on their aims and objectives, input data, model validity, results and conclusions (online supplemental table 3). Screening questions/criterion were used to guide the scoring process, with the score ranging from 0 (poor) to 2 (good) on each criterion. The overall quality level assigned to individual studies were summarised into four broad categories; very high (>13), high (11–13), medium (8–10) and low (<8) (online supplemental table 3).

bmjgh-2020-002919supp003.pdf (80.4KB, pdf)

Results

Literature search, data synthesis and quality assessment

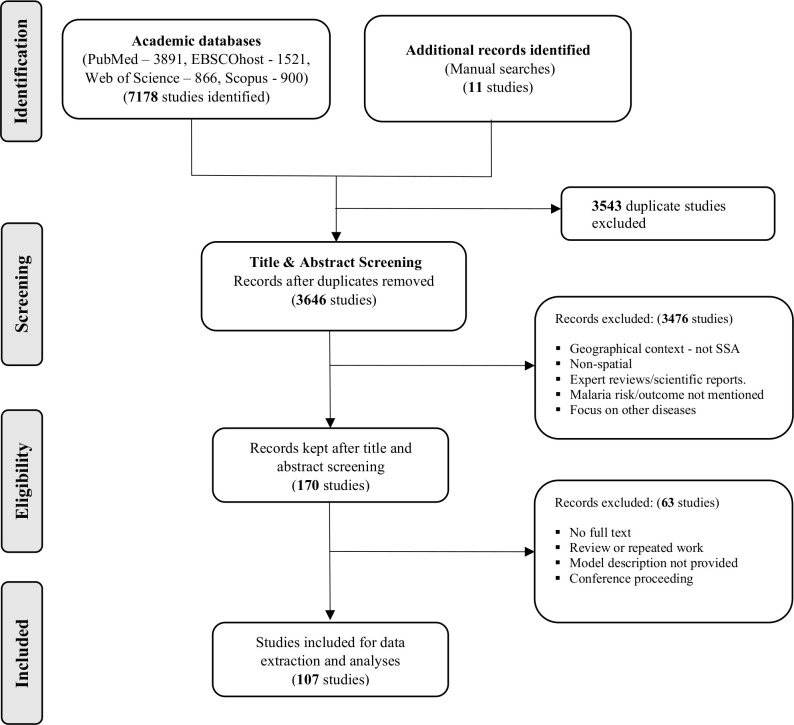

A total of 7189 studies were retrieved from the various databases with 170 studies fully screened after the title and abstract review. Ultimately 107 studies were included for review and underwent quality assessment and synthesis (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow from literature search to data extraction and analyses.

The distribution of studies by geographical scale and scope varied across SSA. Five (5%) studies were continental in scale, 48 (45%) studies were national and 52 (49%) studies were subnational. Kenya (10 studies) and Tanzania (9 studies) had the highest number of publications included in the review (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Geographical scale and scope of studies. Geographical scale (municipality, district, province/state, country) of studies is given in grey boxes. The studies covered 27 countries in sub-Saharan Africa with East Africa being the most represented subregion.

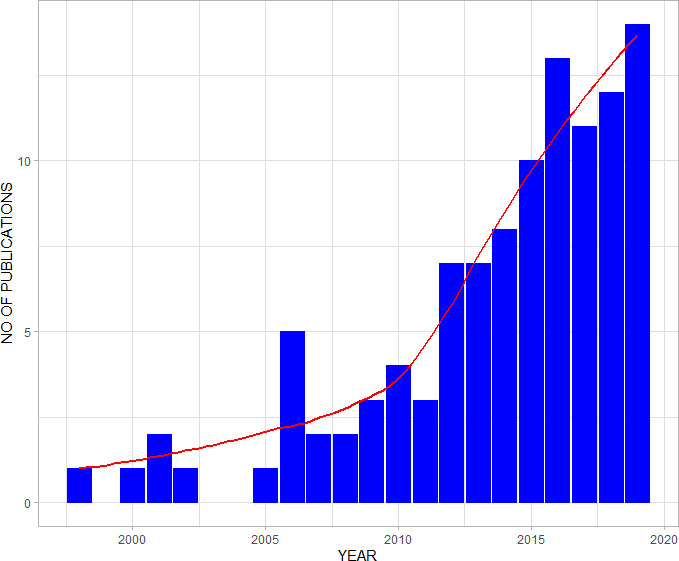

The longest study period spanned 115 years,19 while the shortest study period was 3 months.20 Fifty-eight (54%) studies had an overall study period ranging between 3 months and 5 years, while 21 (20%) studies had their study period ranging between 6 and 10 years and 28 (26%) studies spanned more than 10 years. Overall, the number of publications increased over the review period (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Bar—chart with a trend line (red) showing the total number of included studies.

The median score was 12 out of 16, with 16 representing the highest possible quality. The overall quality score of the reviewed studies ranged from 7 to 16. Two studies were of low quality, 22 studies were of medium quality, 42 studies were of high quality and 41 studies were of very high quality (online supplemental table 3).

Data sources, covariate selection and preprocessing

From the review, global, continental, national and subnational databases/repositories provided a rich source of both malaria data and covariates used for modelling. These sources comprised of geographically referenced surveys used by 34 (32%) studies, 20 (19%) studies used population databases and 10 (9%) studies used government records. Routinely collected data from the Health and Demographic Surveillance System were used in 16 (15%) studies. Sources of climatic and environmental covariates consisted of ground station observations used by 17 (16%) studies and remotely sensed satellite surrogates of climate, urbanisation and topography were employed by 49 (46%) studies (table 1).

Table 1.

Data sources

| Type | Source | No | References |

| Global/continental databases | Malaria Transmission Intensity and Mortality Burden across Africa | 1 | 88 |

| Mapping Malaria Risk in Africa databases | 9 | 29 31 44 45 63 67 73 97 98 | |

| World Pop/Afripop | 14 | 25 41 46–48 59 60 72 75 88 99–102 | |

| Food and Agriculture Organisation-Food Security and Nutrition Analysis Unit | 1 | 59 | |

| Global Rural and Urban Mapping project | 2 | 41 99 | |

| WHO database on malaria drug resistance | 1 | 98 | |

| Global Lakes and Wetlands Database | 3 | 34 48 49 | |

| UN World Urbanisation prospects database | 4 | 25 49 50 64 | |

| National databases | Health and Demographic Surveillance System | 16 | 28 32 38 42 79 100 102–111 |

| Census | 6 | 21 22 68 108 112 113 | |

| National statistical agencies | 10 | 40 51 65 69 107 114–118 | |

| Demographic Health Survey | 7 | 23 26 52 61 66 98 101 | |

| Malaria Indicator Survey | 12 | 37 41 43 49 52 60 66 75 76 99 117 119 | |

| Subnational databases | Cross-sectional surveys | 9 | 8 20 46 48 49 53 120–122 |

| Cohort studies | 5 | 33 39 54 84 123–125 | |

| Cluster surveys | 1 | 34 | |

| Entomological/parasitological surveys | 5 | 77 113 120 126 127 | |

| Remote sensing | Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer | 28 | 25 27 29 30 34 37 38 41 48 55 59–61 65 66 72 75–79 99 100 103 104 128–130 |

| Africa Data Dissemination Service | 8 | 29 30 65 71 76–79 | |

| United States Geological Survey-Earth Resources Observation and Science Centre | 8 | 27 28 30 35 43 76 77 99 | |

| Health Mapper | 8 | 27 29 30 41 61 65 68 76 77 | |

| Shuttle Radar Topographic Mission | 5 | 28 60 72 99 129 | |

| WorldClim-Global Climate database | 7 | 23 34 37 59–61 100 | |

| Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission | 3 | 104 128 130 | |

| Early Warning System | 3 | 66 72 88 | |

| Climate Research Unit | 3 | 23 71 131 | |

| National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration | 2 | 109 132 | |

| Water Resources Institute | 1 | 63 | |

| World Wildlife Fund | 1 | 37 | |

| Africover | 1 | 34 | |

| Famine Early Warning Systems Network Land Data Assimilation System | 1 | 88 | |

| Ground station data | Meteorological data | 17 | 21 22 35 38 40 54 69–71 84 103 106 113 126 133–135 |

In this review, variable selection techniques were explicitly specified by 47 (44%) studies. These techniques varied substantially; with the frequentist approach used in 14 (13%) studies to assess the (uni and multi) variate association between malaria outcomes and its covariates being the most common. Significant covariates were included if their nominal p value was less than 0.001,21–24 0.05,25–27 0.1,28 0.15,29 300.2.31 32 and 0.25.33 The generalised linear models used by nine (8%) studies identified the best covariate subset based on Wald’s p value20 32 34–36 and the variance inflation factor.37 Additionally, six (6%) studies used the total-sets analysis based on Bayesian information criterion (BIC) statistic to identify the optimal variable combination. Principal component analysis was employed by eight (8%) studies to reduce dimensions and avoid collinearities in environmental factors,38 39 meteorological factors38 40 and household demographics.32 33 41–43 The Bayesian stochastic search was used by three (3%) studies to identify covariates with the highest inclusion probability. Other techniques employed included the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) penalty, the Spike and slab and the Bayesian model averaging cumulatively used by five (5%) studies. Two studies (2%) reviewed covariates used in past studies to identify and adopt the best suite of covariates to be included in their model (table 2).

Table 2.

Analytical methods used in malaria risk mapping

| Category | Method | No | References |

| Variable selection techniques | Stepwise procedures | 11 | 20 28 34–36 44 45 61 67 73 135 |

| Preliminary frequentist analysis | 14 | 21 22 24–27 29–32 61 63 84 134 | |

| Total-set analysis | 6 | 8 48 49 58–60 | |

| Principal component analysis | 6 | 32 39–43 | |

| Bayesian stochastic search | 3 | 72 77 119 | |

| LASSO penalty | 2 | 47 88 | |

| Literature review | 2 | 30 74 | |

| Spike and slab | 2 | 72 99 | |

| BMA | 1 | 100 | |

| Visualisation | Rate map | 63 | 8 19 24 26–32 34 35 37 40 41 43 45 46 49–51 53 55 57–68 71–80 84 88 97 98 100–102 108 109 111 112 114 117 119 122 124 135 136 |

| Dot map | 25 | 20 27 29 31 36 39 42 48 50 55–57 63 65 72 99 105 113 120 121 123 125 127 132 137 | |

| Case counts | 16 | 21 25 41 44 54 65 66 72 76–78 98 106 115 118 131 | |

| Spatial cluster ‘hotspot’ analysis | Spatial scan statistic | 15 | 33 38–40 42 51 54 105 114 120 122 123 127 134 137 |

| Global Moran’s/ | 6 | 23 56 57 68 115 121 | |

| Getis Ord statistic | 3 | 32 112 113 | |

| Local Moran’sI | 7 | 23 32 68 102 108 117 118 | |

| Spatial/spatio-temporal modelling | Geostatistical models | 27 | 8 26 27 29–31 34 36 37 41 43 46 48–50 53 59–61 63–65 74–78 |

| Bayesian CAR models | 15 | 19 21 22 24 25 44 47 66 84 102 103 119 129 131 135 | |

| Time series models | 9 | 40 51 69 70 107 125 128 130 133 | |

| Bayesian Kriging | 5 | 45 62 67 72 73 | |

| Conventional Poisson | 7 | 97 104 109–112 126 | |

| Conventional logistic | 4 | 28 35 52 113 | |

| GAM | 2 | 38 40 | |

| Negative binomial regression | 1 | 117 | |

| GWR | 1 | 57 | |

| ANN | 1 | 116 | |

| BRT | 1 | 55 | |

| Model validation/predictive ability | Data partitioning | 24 | 8 19 27 34 36 37 41 46 48–50 53 58 61 63–65 76–78 80 88 109 110 |

| Deviance information criterion | 19 | 21–25 30 34 60 64 66 75 79 84 102 103 110 125 131 135 | |

| Akaike information criterion | 8 | 37 60 66 75 79 113 128 130 | |

| Root mean squared error | 7 | 35 47 55 64 79 88 130 | |

| Variogram-based algorithm | 7 | 19 47 72 79 84 99 119 | |

| Mean absolute prediction error | 6 | 8 48 49 58 59 61 | |

| Mean error | 3 | 34 36 47 | |

| Bayesian information criterion | 2 | 23 107 |

ANN, Artificial neural network; BMA, Bayesian model averaging; BRT, Boosted regression tree; CAR, Conditional autoregressive; GAM, General additive model; GWR, Geographically weighted regression; LASSO, Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator.

Data preprocessing procedures were employed in 37 (35%) studies. The verification of geographical coordinates by either paper maps44 or global digital maps8 31 34 36 42 44–58 used in 20 (21%) studies was the most common procedure. Algorithms based on the catalytic conversion models8 36 46 48–50 55 59–61 were used in 10 (9%) studies to generate age-adjusted malaria prevalence predictions, that is, age range of 2–10 years. Continuous variables were standardised in seven (7%) studies; by log transformation,62 centring on the mean47 63–66 and zero.47 Four (4%) studies excluded study regions with inconsistent datasets8 19 67 68 while two (2%) studies used the average of its nearest values.69 70 Other approaches used included the multivariate stepwise regression,71 using data values extracted from previous surveys.32

Modelling covariates

The type and number of covariates included in malaria models varied across studies. Different categories encompassing climatic and environmental, sociodemographic and malaria intervention covariates were identified. The most common covariates in the environmental domain were rainfall and temperature used in 61 (57%) and 59 (55%) studies, respectively; while the most common sociodemographic covariates used in 12 (11%) studies were population size and age. Malaria interventions (insecticide-treated bed nets, indoor residual spraying and artemisinin-based combined therapy) used in 32 (30%) studies and transmission seasonality used in 28 (26%) studies were also common. Detailed variations and adaptations covariates are presented in table 3.

Table 3.

Covariates used in malaria risk mapping

ACTs, Artemisinin-based combined therapy; CTI, Compound topographic index; DEM, Digital elevation models; EIR, Entomological inoculation rate; EVI, Enhanced vegetation index; GIS, geographical information system; IRS, Indoor residual spraying; ITN, Insecticide-treated bed nets; LLIN, Long lasting insecticidal nets; LST, Land surface temperature; NDVI, Normalised difference vegetation index; NDWI, Normalised difference water index; SES, Social economic status; TSI, Temperature suitability index; TWI, Topographic wetness index.

Spatial, temporal and spatio-temporal methods

A variety of spatial, temporal and spatio-temporal methods were employed to visualise malaria risk patterns, explore spatial clusters and model risk across space and time in SSA. Measurement of malaria burden varied across studies with the type of outcome informing the modelling framework. The most common malaria metric used in models, was incidence used in 50 (47%) studies and prevalence used in 37 (35%) studies. Table 3 presents a summary of the malaria outcomes that were considered in the papers included in the review.

In settings of low malaria transmission, local and global spatial cluster detection methods were used in 31 (29%) studies to identify significant geographical variation in malaria risk patterns (table 2). These were the Kulldorf spatial scan statistic, Getis’ Gi*(d) local statistic; local Moran’s I statistic and the Global Moran’s I statistic. On the other hand, nine (8%) studies used temporal models to explore and forecast malaria risk at different temporal resolutions, with the autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model used in seven (6%) studies being the most common. Two studies (2%) used a univariate seasonal ARIMA model to explore malaria risk patterns (table 2).

The Bayesian spatial only and space-time kriging—a statistically unbiased and robust interpolation method appropriate for study settings with limited data; was used in five (6%) studies, to predict risk at unsampled locations,67 72 improve predictions in geographical areas with considerable variation between observed values and model predictions45 73 and model the spatial and temporal correlations of monthly malaria morbidity cases.62

Using point-referenced data sourced from multiple independent surveys, 27 (25%) studies applied both the model-based geostatistical (MBG) and Bayesian MBG methods to analyse, predict and map malaria risk. In this framework, the spatio-temporal dependency was modelled as a Gaussian process in fourteen (13%) studies.8 34 36 37 43 46 48–50 53 59 60 64 74 Spatial only random effects (dependency) were modelled via the Gaussian prior distribution26 27 29–31 41 63 65 75–78 in 12 (11%) studies. Temporal random effects were assigned a first order autoregressive AR (1) prior distribution in three (3%) studies37 75 79 and second order autoregressive AR(2) prior distribution8 in one (1%) study (table 4).

Table 4.

Structure of the spatio-temporal models

| ID | References | Year | Space | Time | Space time |

| 1 | Abellana et al 84 | 2008 | CAR | ||

| 2 | Alegana et al 64 | 2016 | Markov random field | – | Gaussian |

| 3 | Alegana et al 25 | 2013 | – | – | CAR |

| 4 | Alemu et al 51 | 2013 | – | Temporal trend – ARIMA | – |

| 5 | Amek et al 79 | 2012 | Gaussian | AR (1) | – |

| 6 | Amratia et al 61 | 2019 | Gaussian | – | – |

| 7 | Appiah et al 62 | 2011 | – | – | STOK |

| 8 | Awine et al 133 | 2018 | – | – | SARIMA |

| 9 | Bejon et al 39 | 2010 | Cluster analysis | Temporal trends | – |

| 10 | Bejon et al 105 | 2014 | Cluster analysis | – | – |

| 11 | Belay et al 106 | 2017 | – | Temporal trends | – |

| 12 | Bennett et al 60 | 2013 | – | – | Gaussian |

| 13 | Bennett et al 75 | 2016 | Gaussian | – | – |

| 14 | Bennett et al 66 | 2014 | CAR | CAR | CAR |

| 15 | Bhatt et al 74 | 2015 | Markov random field | AR (1) | Gaussian |

| 16 | Bisanzio et al 113 | 2015 | Markov random field | B – splines with RW (2) | – |

| 17 | BM & OE44 | 2007 | CAR | – | – |

| 18 | Bousema et al 123 | 2010 | Hotspot analysis | – | – |

| 19 | Ceccato et al 71 | 2007 | Cluster analysis | – | – |

| 20 | Chipeta et al 50 | 2019 | – | – | Gaussian |

| 21 | Chirombo et al 109 | 2020 | Markov random field | Markov random field | Gaussian |

| 22 | Cissoko et al 38 | 2020 | Cluster analysis | Temporal trend | |

| 23 | Colborn et al 88 | 2018 | – | – | Gaussian |

| 24 | Coulibaly et al 54 | 2013 | Cluster analysis | – | – |

| 25 | DePina et al 118 | 2019 | Cluster analysis | Temporal trend | _ |

| 26 | Diboulo et al 41 | 2016 | Gaussian | – | – |

| 27 | Ferrão et al 70 | 2017a | – | Temporal trend - ARIMA | – |

| 28 | Ferrão et al 69 | 2017b | – | Temporal trend - ARIMA | – |

| 29 | Ferrari et al 124 | 2016 | Cluster analysis | – | – |

| 30 | Gaudart et al 125 | 2006 | Cluster analysis | Temporal trend - ARIMA | – |

| 31 | Gemperli et al 67 | 2006 | Exponential correlation function | – | – |

| 32 | Gething et al 98 | 2016 | – | P – splines with RW (1) | – |

| 33 | Giardina et al 78 | 2015 | Gaussian | – | – |

| 34 | Giardina et al 65 | 2012 | Multivariate Normal | – | – |

| 35 | Giardina et al 101 | 2014 | Gaussian | – | – |

| 36 | Giorgi et al 46 | 2018 | – | – | Gaussian |

| 37 | Gómez-Barroso et al 20 | 2017 | Cluster analysis | – | – |

| 38 | Gosoniu et al 27 | 2012 | Gaussian | – | – |

| 39 | Gosoniu et al 76 | 2010 | Gaussian | – | – |

| 40 | Gosoniu et al 63 | 2006 | Gaussian | – | – |

| 41 | Houngbedji et al 77 | 2016 | Normal | – | – |

| 42 | Ihantamalala et al 114 | 2018 | Cluster analysis | – | – |

| 43 | Ikeda et al 116 | 2017 | – | – | SOM |

| 44 | Ishengoma et al 126 | 2018 | – | Temporal trends | – |

| 45 | Kabaghe et al 43 | 2017 | Gaussian | – | – |

| 46 | Kabaria et al 55 | 2016 | – | – | BRT |

| 47 | Kamuliwo et al 117 | 2015 | Cluster analysis | – | – |

| 48 | Kang et al 37 | 2018 | Gaussian | AR (1) | – |

| 49 | Kangoye et al 127 | 2016 | Cluster analysis | – | – |

| 50 | Kanyangarara et al 28 | 2016 | – | – | – |

| 51 | Kazembe et al 31 | 2006 | Gaussian | – | – |

| 52 | Kifle et al 107 | 2019 | Cluster analysis | Temporal trends - SARIMA | |

| 53 | Kigozi et al 128 | 2016 | – | Temporal trend- ARIMA | – |

| 54 | Kleinschmidt et al 45 | 2000 | Kriging | – | – |

| 55 | Kleinschmidt et al 73 | 2001a | Kriging | – | – |

| 56 | Kleinschmidt et al 97 | 2001b | Kriging | – | – |

| 57 | Kleinschmidt et al 136 | 2002 | Normal | Normal | – |

| 58 | Mabaso et al 131 | 2005 | CAR | – | AR (1) |

| 59 | Mabaso et al 24 | 2006 | CAR | AR (1) | – |

| 60 | Macharia et al 53 | 2018 | – | – | Gaussian |

| 61 | Mfueni et al 52 | 2018 | – | – | – |

| 62 | Midekisa et al 130 | 2012 | – | Temporal trend - SARIMA | – |

| 63 | Millar et al 100 | 2018 | – | – | – |

| 64 | Mirghani et al 120 | 2010 | Cluster analysis | – | – |

| 65 | Mlacha et al 56 | 2017 | Cluster analysis | – | – |

| 66 | Mukonka et al 138 | 2014 | – | Temporal trends | – |

| 67 | Mukonka et al 115 | 2015 | Cluster analysis | – | – |

| 68 | Mwakalinga et al 121 | 2016 | Cluster analysis | – | – |

| 69 | Ndiath et al 57 | 2015 | Cluster analysis | – | – |

| 70 | Ndiath et al 42 | 2014 | Cluster analysis | – | – |

| 71 | Nguyen et al 110 | 2020 | Gaussian | – | Gaussian |

| 72 | Noor et al 48 | 2013a | Gaussian | – | GRF |

| 73 | Noor et al 34 | 2008 | Gaussian | – | – |

| 74 | Noor et al 58 | 2012b | – | – | GRF |

| 75 | Noor et al 36 | 2009 | – | – | GRF |

| 76 | Noor et al 8 | 2014 | Gaussian | AR (2) | – |

| 77 | Noor et al 49 | 2013b | – | – | GRF |

| 78 | Noor et al 59 | 2012a | Gaussian | – | Stationary Gaussian |

| 79 | Nyadanu et al 108 | 2019 | Cluster analysis | – | – |

| 80 | Okunola et al 23 | 2019 | Cluster analysis | – | – |

| 81 | Onyiri29 | 2015 | Gamma | – | – |

| 82 | Ouedraogo et al 40 | 2018 | – | Temporal trend- ARIMA | – |

| 83 | Ouédraogo et al 111 | 2020 | CAR | AR (1) / Temporal trends | |

| 84 | Peterson et al 134 | 2009 | Cluster analysis | – | – |

| 85 | Pinchoff et al 35 | 2015 | – | – | – |

| 86 | Raso et al 30 | 2012 | Multivariate Normal | – | – |

| 87 | Rouamba et al 102 | 2020 | CAR | CAR | Gaussian |

| 88 | Rumisha et al 80 | 2014 | Gaussian | AR (1) | – |

| 89 | Selemani et al 32 | 2015 | Cluster analysis | – | – |

| 90 | Selemani et al 103 | 2016 | CAR | AR (1) | – |

| 91 | Sewe et al 104 | 2016 | – | Natural cubic spline | – |

| 92 | Seyoum et al 137 | 2017 | Cluster analysis | – | – |

| 93 | Shaffer et al 122 | 2020 | Cluster analysis | Temporal trends | – |

| 94 | Simon et al 112 | 2013 | Cluster analysis | – | – |

| 95 | Siraj et al 135 | 2015 | CAR | – | – |

| 96 | Snow et al 19 | 2017 | CAR | CAR | – |

| 97 | Snow et al 132 | 1998 | – | – | – |

| 98 | Solomon et al 33 | 2019 | Cluster analysis | – | – |

| 99 | Ssempiira et al 119 | 2018a | CAR | AR (1) / temporal trend | – |

| 100 | Ssempiira et al 129 | 2018b | CAR | AR (1) / temporal trend | – |

| 101 | Ssempiira et al 99 | 2017b | CAR | – | – |

| 102 | Ssempiira et al 72 | 2017a | – | – | – |

| 103 | Sturrock et al 47 | 2014 | CAR | Temporal trend | – |

| 104 | Yankson et al 26 | 2019 | Gaussian | – | – |

| 105 | Yeshiwondim et al 68 | 2009 | – | – | – |

| 106 | Zacarias and Andersson22 | 2011 | CAR | AR (1) | – |

| 107 | Zacarias and Majlender21 | 2011 | CAR | RW (1) | – |

AR, autoregressive; ARIMA, autoregressive integrated moving average; BRT, boosted regression tree; CAR, conditional autoregressive; GRF, Gaussian random field; RW, random walk; SARIMA, seasonal autoregressive integrated moving average; SOM, self-organising maps; STOK, space-time ordinary kriging.

Using observations aggregated over distinct geographical region/spatial partitions/adjacent units (eg, census tract, administrative boundaries); 15 (14%) studies used the Bayesian conditional autoregressive (CAR) models, to explore the spatial and spatio-temporal variation of malaria risk. To account for the temporal dependency between consecutive time points; seven studies (6%) used the first order autoregressive AR (1) prior process, whereas one study (1%) used the random walk of order one RW (1) prior process (table 4).

Other models

Generalised linear modelling framework, such as the Poisson, logistic regression, negative binomial and geographically weighted regression, was used in fifteen studies (14%). These models explored the association of malaria counts or rates and its correlates, using appropriate exponential distribution families. Machine learning techniques such as the artificial neural network and the boosted regression tree were used to analyse incidence patterns and to examine malaria prevalence, respectively (table 4).

Model validation, performance and uncertainty

A range of different validation techniques were used to assess model fitness and to select the optimal predictive models. The most commonly used approach entailed partitioning the data for model training and validation and was employed in 24 (22%) studies. The training set was then used to validate the predictive model fit, whereas the validation set was used for assessing the model predictive ability. The representative holdout datasets were selected using a spatially and temporal declustered algorithm,8 48 49 59 stratified sampling approach75 and randomly.35 46 50 53 80 Information criteria, that is, the deviance information criterion, Akaike information criterion and the BIC were used in seventeen (16%) studies. Seven (7%) studies used variogram-based algorithms to identify estimates falling within the 95% credible interval. Model precision and accuracy metrics included the mean prediction error, root mean squared error, mean absolute prediction error, mean error and the SD (table 2).

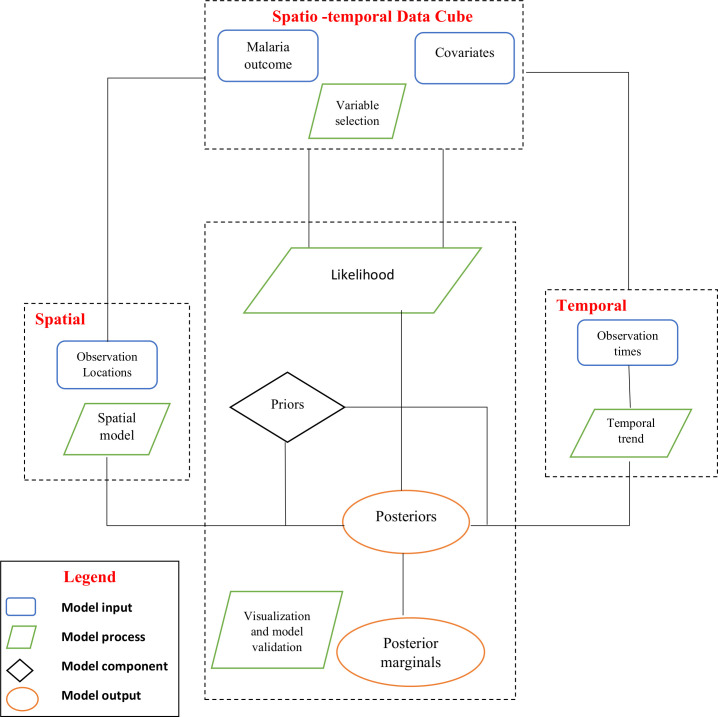

Summarised modelling framework

The rapid expansion of methods and data informs the need to guide future spatial and spatio-temporal modelling of infectious diseases in SSA (online supplemtal table 4). We illustrate a framework composed of four fundamental modelling entities, namely: inputs, process, stochastic components and output. Malaria data and covariates sourced from different spatial and temporal resolutions are considered to be the model inputs. A series of progressive and interdependent steps/processes on the model inputs are then used to generate the outputs (posterior marginals). Posterior marginals can then be approximated using iterative computational techniques such as the Markov Chain Monte Carlo methods or by using numerical integrations via the Integrated Nested Laplace Approximations method.81 82(figure 4)

Figure 4.

Schematic illustration of the spatio-temporal modelling framework for malaria risk in sub-Saharan Africa.

bmjgh-2020-002919supp004.pdf (14.6KB, pdf)

Discussion

Scalable guidelines for rigorous and transparent statistical methodology are necessary for reproducible malaria risk estimation. This review offers a comprehensive appraisal and synthesis of methods and covariates used in malaria risk mapping in SSA in the last five decades.

Sources of malaria data

High-resolution maps revealing the spatio-temporal variation of malaria endemicity are useful for estimating malaria burden, quantifying the effectiveness of control initiatives and assessing the progress towards its elimination nationally and subnationally. However, malaria risk mapping efforts in SSA are rarely based on routinely collected data. Instead, periodic and costly household survey’s data have traditionally been used in modelling malaria risk. To address this challenge and obtain robust estimates reflective of the subnational burden, WHO initiated the high burden to high impact approach in 2018, which underscored the need for reliable national data systems. This is considered central to the understanding of malaria burden in low transmission settings and in the most vulnerable populations.3 Additionally, the approach has availed more malaria data in malaria-endemic settings, and caution is needed when gathering and interpreting findings generated from data at fine spatial and/or temporal scales with varying degree of completeness and representativeness.83

The steady growth of satellite, remote sensing platforms and curated databases has made available a rich suite of both environmental and socioeconomic covariates at a finer level of detail useful for mapping malaria risk at high spatial and temporal resolution. Validating the quality of available satellite data prior to their inclusion in malaria studies remains central to achieving robust estimates.

While malaria incidence and prevalence metrics can be modelled from routine health information systems and sample surveys respectively, caution should be taken when interpreting estimates as both metrics are products of interacting factors such as interventions, sociodemographic and environmental factors that may contribute to the overall risk. A concise picture may be achieved by measuring malaria indicators at a finer spatial scale and exploring the nature and scope of the interaction. Data on malaria mortality as an outcome were sparse, and efforts must be made to increase data collection and improve the sensitivity and specificity of malaria mortality burden attribution in SSA.74 83As many countries in SSA transition epidemiologically from high to low malaria transmission zones, obtaining useful metrics for mapping risk from sparse national surveys at low, moderate and heterogeneous transmission settings possess unique challenges for measuring progress and impact.84

The paucity of continuous, reliable data necessary to yield estimates with greater geographical and temporal richness is a growing concern in the era of evidence-based public health. A high-quality, routinely collected data avail an alternative source of malaria metrics for continuous analysis over time.83 Investments should be channelled towards establishing and addressing inadequacies in the health information systems to enable subnational mapping of malaria risk. However, the urge for quality data and the increasing need of accurate estimates can significantly be improved by adoption of data-driven modelling approaches that leverage both routine and household survey data in their model framework.85 Additionally, detailed information on critical data sources, preliminary data adjustments undertaken before modelling should be availed as an important step towards enhancing reproducibility of methods and estimates.86

Understanding covariates used in mapping malaria risk

Improving the precision of malaria risk estimates largely depends on limiting subjective decisions. These decisions may impact on the modelling process, even as more covariates becomes accessible at finer geographical and temporal resolutions. Studies have shown large variables to be desirable for prediction, whereas small sets of variables to be meaningful for inference.87 It is important to understand the complex relationship between covariates at the same spatial or temporal resolution, to avoid overfitting. The trade-off between model interpretability, predictive ability, spatial and temporal scope, data accessibility and computational limitations are critical factors worth considering when selecting candidate covariates. Evidentially variable selection is an important preliminary step for a robust malaria risk mapping exercise. However, this approach continues to receive little attention amidst the growing diversity of covariate layers that need to be identified and included in the models.

Environmental and climatic factors influence mosquito vector abundance, distribution and longevity; at different time scales88 and are important for mapping malaria risk.59 A scoping review by Zinszer et al 89 highlighted the importance of climatic-related predictors in malaria risk prediction. Understanding the different facets and extent of how climatic influences on malaria risk variation; has been enhanced by advances in remote sensing and satellite imagery technology, increasing the availability of remotely sensed climatic data at high spatial resolution.35 In this review proxies of; temperature (land surface temperature, temperature suitability index, mean/min/max/weekly) and rainfall/precipitation (weekly/monthly/annual) were the most widely used environmental factors related to malaria transmission in SSA. Vegetative indices such as elevation, surface moisture, land use and land cover were included in malaria risk maps, primarily due to their association with temperature and precipitation which indirectly influences90 the distribution of malaria. Remote sensing will continue to feature prominently as a cost-effective tool for mapping malaria risk in SSA and an important source of environmental and climatic covariates.91 The review further demonstrates the significance of non-climatic determinants such as malaria interventions and demographic factors in malaria risk mapping.

Modelling frameworks in malaria risk mapping

Complex decisions involving key modelling components such as covariates to include, preliminary data preprocessing and diagnostics checks demands advanced statistical knowledge. Extensive computational algorithms and complex spatio-temporal data structures may limit the applicability of these modelling approaches to experts. Furthermore, complex models used to represent malaria heterogeneity may not necessarily represent the truth on the ground. Thus, the statistical uncertainties around model estimates should be carefully examined, and the varying quantities and quality malaria data, that informs modelling approaches accounted for.

The review highlights the prominence and flexibility of geostatistical methods in modelling spatial and spatio-temporal malaria patterns, at policy-relevant units and thresholds.46 Geostatistical methods provide a useful framework for interpolating imperfect data from multiple independent surveys by estimating spatial dependence from the data. At low spatial resolution, the Bayesian geostatistical framework accounts for uncertainty resulting from sparsely sampled point-referenced data by assigning priors that allows ‘borrowing of strength’ from adjacent regions leading to robust estimates and predictions.92 Amidst the current scarcity and imperfections of routine, high resolution and spatially expansive malaria data in many SSA countries, using geostatistical methods with data from multiple independent georeferenced surveys, continues to be important for generating reliable estimates.

Bayesian hierarchical CAR models are useful for modelling spatially correlated areal data by smoothing noisy estimates and leveraging information from adjacent regions. However, choosing an appropriate prior specification for the parameters defining the spatial interaction is inevitable and sometimes challenging. Notably, the spatial dependence among neighbouring regions is accounted for by assuming a CAR process in the random effects. For example, in the Besag York and Mollie/convolution model, location-specific spatial effects are assumed to follow a normal distribution with the mean equal to the average of its neighbours and the variance considered to be inversely proportional to the number of neighbours. In the Leroux et al model, the spatial dependence is based on the weighted average of both the independent random effects and spatially structured random effects.93 94 The intrinsic CAR and Besag, York and Mollie (BYM) were the most frequent global spatial smoothing specifications used in the review; given their easy implementation in a range of softwares. However, caution should be taken to minimise over smoothing—obscuring the underlying geographical patterns. Future modelling studies should compare the impact of using other spatial smoothing priors.

Overall, malaria risk mapping has increased dramatically over the last decades, with novel methods advanced to meet the quest for accurate estimates of malaria burden. Whereas most approaches are built on classical statistical methods, recent advances in computing, availability of geographically referenced data have ushered/propagated new techniques designed to address existing challenges. These approaches include ensemble modelling, neural networks, simulation-based methods and bootstrap models to better capture space-time interactions.

Recommendations for best practices

As malaria landscape diversifies in the next decade, investments in primary data collection at subnational scales, development and continuous application of robust modelling tools will continue to be important priorities in malaria control and elimination efforts. In the era of open data policy and reproducible research, our review reiterates the importance of periodically reviewing, validating and updating malaria maps to accommodate new data sources, improved data quality, enhanced computing power and novel methodological approaches. Variable selection procedures should be data driven and objectively developed to the maximise the predictive accuracy of malaria risk mapping. The spatio-temporal modelling framework should incorporate practical challenges facing control and elimination of malaria in SSA. These challenges are: human migration within and among endemic zones, mapping asymptotic infection reservoirs and accounting for differential immunity within a population.95 96

Strengths and limitations

The review search strategy was exhaustive and transparent, in accordance with the current methodological guidelines and included studies have provided a fair depiction of malaria risk mapping efforts in SSA. The methodological approach of the included studies was diverse, making meta-analysis inappropriate. The review considered only studies published in English and relevant papers published in other languages might have been excluded.

Conclusions

Malaria risk mapping remains an important component for understanding the burden of malaria in SSA. The review has described modelling approaches and examined covariates used in mapping malaria risk in different epidemiological contexts. As malaria transmission continues to decline in SSA, the use of metrics that accurately describes changes in its transmission intensity across space and time will be important for the design and implementation of evidence-based control and elimination measures.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the College of Health Sciences, systematic review services and library services at the University of KwaZulu-Natal for providing training and resources at the initial phases of the review.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Alberto L Garcia-Basteiro

Twitter: @Pete_M_M

Contributors: JNO, BS and RWS conceived and designed the systematic review. JNO, BS and CK conducted the literature search, study selection and data extraction. JNO wrote the first draft of the manuscript with assistance from CK and BS. PMM and RWS revised the draft critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: JNO acknowledges support from the University of KwaZulu Natal, College of Health Sciences postgraduate scholarship scheme. RWS is supported as a Wellcome Trust Principal Fellow (#103602 and 212176) that also supported PMM. PMM acknowledges support for his PhD under the IDeALs Project part of the DELTAS Africa Initiative (DEL-15-003). The DELTAS Africa Initiative is an independent funding scheme of the African Academy of Sciences (AAS)'s Alliance for Accelerating Excellence in Science in Africa and supported by the New Partnership for Africa's Development Planning and Coordinating Agency with funding from the Wellcome Trust (107769) and the UK government. RWS and PMM are grateful to the support of the Wellcome Trust to the Kenya Major Overseas Programme (203077).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information. The data supporting conclusions made in this review are available in the detailed reference list.

References

- 1. World Health Organization Health in the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. World health assembly resolution 6911. Geneva; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization Global technical strategy for malaria 2016-2030; 2015.

- 3. World Health Organization World malaria report 2019. Geneva; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Snow RW, Noor AM. Malaria risk mapping in Africa: The historical context to the Information for Malaria (INFORM) project. Nairobi, Kenya: Working paper in support of the INFORM Project funded by the Department for International Development and The Wellcome Trust, UK; 2015.

- 5. Snow RW, Marsh K, le Sueur D. The need for maps of transmission intensity to guide malaria control in Africa. Parasitology Today 1996;12:455–7. 10.1016/S0169-4758(96)30032-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Le Sueur D, Binka F, Lengeler C, et al. An atlas of malaria in Africa. Africa health 1997;19:23–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Omumbo JA, Noor AM, Fall IS, et al. How well are malaria maps used to design and finance malaria control in Africa? PLoS One 2013;8:e53198 10.1371/journal.pone.0053198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Noor AM, Kinyoki DK, Mundia CW, et al. The changing risk of Plasmodium falciparum malaria infection in Africa: 2000–10: a spatial and temporal analysis of transmission intensity. The Lancet 2014;383:1739–47. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62566-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kraemer MUG, Hay SI, Pigott DM, et al. Progress and challenges in infectious disease cartography. Trends Parasitol 2016;32:19–29. 10.1016/j.pt.2015.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ye Y, Andrada A. Estimating malaria incidence through modeling is a good academic exercise, but how practical is it in high-burden settings? Am J Trop Med Hyg 2020;102:701–2. 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Weiss DJ, Mappin B, Dalrymple U, et al. Re-Examining environmental correlates of Plasmodium falciparum malaria endemicity: a data-intensive variable selection approach. Malar J 2015;14:68 10.1186/s12936-015-0574-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dalrymple U, Mappin B, Gething PW. Malaria mapping: understanding the global endemicity of falciparum and vivax malaria. BMC Med 2015;13:140. 10.1186/s12916-015-0372-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Canelas T, Castillo-Salgado C, Ribeiro H. Systematized literature review on spatial analysis of environmental risk factors of malaria transmission. Adv Infect Dis 2016;06:52–62. 10.4236/aid.2016.62008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Odhiambo JN, Sartorius B. Spatio - temporal modelling assessing the burden of malaria in affected low and middle-income countries: a scoping review. BMJ Open 2018;8:e023071 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liberati A, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:W–W-94. 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moher D, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:264–9. 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. World Health Organization World malaria report 2015. Geneva; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Aswi A, Cramb SM, Moraga P, et al. Bayesian spatial and spatio-temporal approaches to modelling dengue fever: a systematic review. Epidemiol Infect 2019;147 10.1017/S0950268818002807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Snow RW, Sartorius B, Kyalo D, et al. The prevalence of Plasmodium falciparum in sub-Saharan Africa since 1900. Nature 2017;550:515–8. 10.1038/nature24059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gómez-Barroso D, García-Carrasco E, Herrador Z, et al. Spatial clustering and risk factors of malaria infections in Bata district, equatorial guinea. Malar J 2017;16:146 10.1186/s12936-017-1794-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zacarias OP, Majlender P. Comparison of infant malaria incidence in districts of Maputo Province, Mozambique. Malar J 2011;10:93 10.1186/1475-2875-10-93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zacarias OP, Andersson M. Spatial and temporal patterns of malaria incidence in Mozambique. Malar J 2011;10:189 10.1186/1475-2875-10-189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Okunlola OA, Oyeyemi OT. Spatio-Temporal analysis of association between incidence of malaria and environmental predictors of malaria transmission in Nigeria. Sci Rep 2019;9:1–11. 10.1038/s41598-019-53814-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mabaso MLH, Vounatsou P, Midzi S, et al. Spatio-Temporal analysis of the role of climate in inter-annual variation of malaria incidence in Zimbabwe. Int J Health Geogr 2006;5:20. 10.1186/1476-072X-5-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Alegana VA, Atkinson PM, Wright JA, et al. Estimation of malaria incidence in northern Namibia in 2009 using Bayesian conditional-autoregressive spatial–temporal models. Spat Spatiotemporal Epidemiol 2013;7:25–36. 10.1016/j.sste.2013.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yankson R, Anto EA, Chipeta MG. Geostatistical analysis and mapping of malaria risk in children under 5 using point-referenced prevalence data in Ghana. Malar J 2019;18:67 10.1186/s12936-019-2709-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gosoniu L, Msengwa A, Lengeler C, et al. Spatially explicit burden estimates of malaria in Tanzania: Bayesian geostatistical modeling of the malaria indicator survey data. PLoS One 2012;7:e23966 10.1371/journal.pone.0023966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kanyangarara M, Mutambu S, Kobayashi T, et al. High-Resolution Plasmodium falciparum malaria risk mapping in Mutasa district, Zimbabwe: implications for regaining control. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2016;95:141–7. 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Onyiri N. Estimating malaria burden in Nigeria: a geostatistical modelling approach. Geospat Health 2015;10 10.4081/gh.2015.306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Raso G, Schur N, Utzinger J, et al. Mapping malaria risk among children in Côte d’Ivoire using Bayesian geo-statistical models. Malar J 2012;11:160 10.1186/1475-2875-11-160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kazembe LN, Kleinschmidt I, Holtz TH, et al. Spatial analysis and mapping of malaria risk in Malawi using point-referenced prevalence of infection data. Int J Health Geogr 2006;5:41 10.1186/1476-072X-5-41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Selemani M, Mrema S, Shamte A, et al. Spatial and space–time clustering of mortality due to malaria in rural Tanzania: evidence from Ifakara and Rufiji health and demographic surveillance system sites. Malar J 2015;14:369 10.1186/s12936-015-0905-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Solomon T, Loha E, Deressa W, et al. Spatiotemporal clustering of malaria in southern-central Ethiopia: a community-based cohort study. PLoS One 2019;14:e0222986 10.1371/journal.pone.0222986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Noor AM, Clements ACA, Gething PW, et al. Spatial prediction of Plasmodium falciparum prevalence in Somalia. Malar J 2008;7:159 10.1186/1475-2875-7-159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pinchoff J, Chaponda M, Shields T, et al. Predictive malaria risk and uncertainty mapping in Nchelenge district, Zambia: evidence of widespread, persistent risk and implications for targeted interventions. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2015;93:1260–7. 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Noor AM, Gething PW, Alegana VA, et al. The risks of malaria infection in Kenya in 2009. BMC Infect Dis 2009;9:180. 10.1186/1471-2334-9-180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kang SY, Battle KE, Gibson HS, et al. Spatio-temporal mapping of Madagascar’s Malaria Indicator Survey results to assess Plasmodium falciparum endemicity trends between 2011 and 2016. BMC Med 2018;16:71 10.1186/s12916-018-1060-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cissoko M, Sagara I, Sankaré MH, et al. Geo-epidemiology of malaria at the health area level, dire health district, Mali, 2013–2017. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:3982–16. 10.3390/ijerph17113982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bejon P, Williams TN, Liljander A, et al. Stable and unstable malaria hotspots in longitudinal cohort studies in Kenya. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000304 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ouedraogo B, Inoue Y, Kambiré A, et al. Spatio-Temporal dynamic of malaria in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 2011–2015. Malar J 2018;17:138 10.1186/s12936-018-2280-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Diboulo E, Sié A, Vounatsou P. Assessing the effects of malaria interventions on the geographical distribution of parasitaemia risk in Burkina Faso. Malar J 2016;15:228 10.1186/s12936-016-1282-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ndiath M, Faye B, Cisse B, et al. Identifying malaria hotspots in Keur SOCE health and demographic surveillance site in context of low transmission. Malar J 2014;13:453 10.1186/1475-2875-13-453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kabaghe AN, Chipeta MG, McCann RS, et al. Adaptive geostatistical sampling enables efficient identification of malaria hotspots in repeated cross-sectional surveys in rural Malawi. PLoS One 2017;12:e0172266 10.1371/journal.pone.0172266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. BM D, OE A. Spatial association between malaria pandemic and mortality. Data Science Journal 2007;6:145–53. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kleinschmidt I, Bagayoko M, Clarke GPY, et al. A spatial statistical approach to malaria mapping. Int J Epidemiol 2000;29:355–61. 10.1093/ije/29.2.355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Giorgi E, Osman AA, Hassan AH, et al. Using non-exceedance probabilities of policy-relevant malaria prevalence thresholds to identify areas of low transmission in Somalia. Malar J 2018;17:88 10.1186/s12936-018-2238-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sturrock HJW, Cohen JM, Keil P, et al. Fine-Scale malaria risk mapping from routine aggregated case data. Malar J 2014;13:421 10.1186/1475-2875-13-421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Noor AM, Alegana VA, Kamwi RN, et al. Malaria control and the intensity of Plasmodium falciparum transmission in Namibia 1969–1992. PLoS One 2013;8:e63350 10.1371/journal.pone.0063350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Noor AM, Uusiku P, Kamwi RN, et al. The receptive versus current risks of Plasmodium falciparumtransmission in northern Namibia: implications for elimination. BMC Infect Dis 2013;13:184 10.1186/1471-2334-13-184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chipeta MG, Giorgi E, Mategula D, et al. Geostatistical analysis of Malawi’s changing malaria transmission from 2010 to 2017. Wellcome Open Res 2019;4:57 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15193.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Alemu K, Worku A, Berhane Y. Malaria infection has spatial, temporal, and spatiotemporal heterogeneity in unstable malaria transmission areas in Northwest Ethiopia. PLoS One 2013;8:e79966 10.1371/journal.pone.0079966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mfueni E, Devleesschauwer B, Rosas-Aguirre A, et al. True malaria prevalence in children under five: Bayesian estimation using data of malaria household surveys from three sub-Saharan countries. Malar J 2018;17:65 10.1186/s12936-018-2211-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Macharia PM, Giorgi E, Noor AM, et al. Spatio-Temporal analysis of Plasmodium falciparum prevalence to understand the past and chart the future of malaria control in Kenya. Malar J 2018;17:340 10.1186/s12936-018-2489-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Coulibaly D, Rebaudet S, Travassos M, et al. Spatio-Temporal analysis of malaria within a transmission season in Bandiagara, Mali. Malar J 2013;12:82 10.1186/1475-2875-12-82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kabaria CW, Molteni F, Mandike R, et al. Mapping intra-urban malaria risk using high resolution satellite imagery: a case study of Dar es Salaam. Int J Health Geogr 2016;15:26 10.1186/s12942-016-0051-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mlacha YP, Chaki PP, Malishee AD, et al. Fine scale mapping of malaria infection clusters by using routinely collected health facility data in urban Dar ES Salaam, Tanzania. Geospat Health 2017;12:294. 10.4081/gh.2017.494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ndiath MM, Cisse B, Ndiaye JL, et al. Application of geographically-weighted regression analysis to assess risk factors for malaria hotspots in Keur SOCE health and demographic surveillance site. Malar J 2015;14:463. 10.1186/s12936-015-0976-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Noor AM, ElMardi KA, Abdelgader TM, et al. Malaria risk mapping for control in the Republic of Sudan. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2012;87:1012–21. 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.12-0390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Noor AM, Alegana VA, Patil AP, et al. Mapping the receptivity of malaria risk to plan the future of control in Somalia. BMJ Open 2012;2:e001160 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bennett A, Kazembe L, Mathanga DP, et al. Mapping malaria transmission intensity in Malawi, 2000–2010. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2013;89:840–9. 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Amratia P, Psychas P, Abuaku B, et al. Characterizing local-scale heterogeneity of malaria risk: a case study in Bunkpurugu-Yunyoo district in northern Ghana. Malar J 2019;18:81 10.1186/s12936-019-2703-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Appiah SK, Mueller U, Cross J. Spatio-Temporal modelling of malaria incidence for evaluation of public health policy interventions in Ghana. West Africa 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Gosoniu L, Vounatsou P, Sogoba N, et al. Bayesian modelling of geostatistical malaria risk data. Geospat Health 2006;1:127–39. 10.4081/gh.2006.287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Alegana VA, Atkinson PM, Lourenço C, et al. Advances in mapping malaria for elimination: fine resolution modelling of Plasmodium falciparum incidence. Sci Rep 2016;6:29628 10.1038/srep29628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Giardina F, Gosoniu L, Konate L, et al. Estimating the burden of malaria in Senegal: Bayesian zero-inflated binomial geostatistical modeling of the MIS 2008 data. PLoS One 2012;7:e32625 10.1371/journal.pone.0032625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Bennett A, Yukich J, Miller JM, et al. A methodological framework for the improved use of routine health system data to evaluate national malaria control programs: evidence from Zambia. Popul Health Metr 2014;12:30 10.1186/s12963-014-0030-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Gemperli A, Sogoba N, Fondjo E, et al. Mapping malaria transmission in West and central Africa. Trop Med Int Health 2006;11:1032–46. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01640.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Yeshiwondim AK, Gopal S, Hailemariam AT, et al. Spatial analysis of malaria incidence at the village level in areas with unstable transmission in Ethiopia. Int J Health Geogr 2009;8:5 10.1186/1476-072X-8-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Ferrão JL, Mendes JM, Painho M, et al. Malaria mortality characterization and the relationship between malaria mortality and climate in Chimoio, Mozambique. Malar J 2017;16:212 10.1186/s12936-017-1866-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Ferrão JL, Mendes JM, Painho M. Modelling the influence of climate on malaria occurrence in Chimoio Municipality, Mozambique. Parasit Vectors 2017;10:260. 10.1186/s13071-017-2205-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Ceccato P, Ghebremeskel T, Jaiteh M, et al. Malaria stratification, climate, and epidemic early warning in Eritrea. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2007;77:61–8. 10.4269/ajtmh.2007.77.61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ssempiira J, Nambuusi B, Kissa J, et al. The contribution of malaria control interventions on spatio-temporal changes of parasitaemia risk in Uganda during 2009–2014. Parasit Vectors 2017;10:450 10.1186/s13071-017-2393-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kleinschmidt I, Omumbo J, Briet O, et al. An empirical malaria distribution map for West Africa. Trop Med Int Health 2001;6:779–86. 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2001.00790.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Bhatt S, Weiss DJ, Cameron E, et al. The effect of malaria control on Plasmodium falciparum in Africa between 2000 and 2015. Nature 2015;526:207–11. 10.1038/nature15535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Bennett A, Yukich J, Miller JM, et al. The relative contribution of climate variability and vector control coverage to changes in malaria parasite prevalence in Zambia 2006–2012. Parasit Vectors 2016;9:431 10.1186/s13071-016-1693-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Gosoniu L, Veta AM, Vounatsou P. Bayesian geostatistical modeling of malaria indicator survey data in Angola. PLoS One 2010;5:e9322 10.1371/journal.pone.0009322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Houngbedji CA, Chammartin F, Yapi RB, et al. Spatial mapping and prediction of Plasmodium falciparum infection risk among school-aged children in Côte d’Ivoire. Parasit Vectors 2016;9:494 10.1186/s13071-016-1775-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Giardina F, Franke J, Vounatsou P. Geostatistical modelling of the malaria risk in Mozambique: effect of the spatial resolution when using remotely-sensed imagery. Geospat Health 2015;10 10.4081/gh.2015.333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Amek N, Bayoh N, Hamel M, et al. Spatial and temporal dynamics of malaria transmission in rural Western Kenya. Parasit Vectors 2012;5:86 10.1186/1756-3305-5-86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Rumisha SF, Smith T, Abdulla S, et al. Modelling heterogeneity in malaria transmission using large sparse spatio-temporal entomological data. Glob Health Action 2014;7:22682. 10.3402/gha.v7.22682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Spatial data analysis with R-INLA with some extensions; 2015. American statistical association.

- 82. Rue H, Martino S, Chopin N. Approximate Bayesian inference for latent Gaussian models by using integrated nested Laplace approximations. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B 2009;71:319–92. 10.1111/j.1467-9868.2008.00700.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Alegana VA, Okiro EA, Snow RW. Routine data for malaria morbidity estimation in Africa: challenges and prospects. BMC Med 2020;18:121. 10.1186/s12916-020-01593-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Abellana R, Ascaso C, Aponte J, et al. Spatio-seasonal modeling of the incidence rate of malaria in Mozambique. Malar J 2008;7:228 10.1186/1475-2875-7-228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Thawer SG, Chacky F, Runge M, et al. Sub-national stratification of malaria risk in mainland Tanzania: a simplified assembly of survey and routine data. Malar J 2020;19:1–12. 10.1186/s12936-020-03250-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Atun R. Time for a revolution in reporting of global health data. Lancet 2014;384:937–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61062-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Heinze G, Wallisch C, Dunkler D. Variable selection - A review and recommendations for the practicing statistician. Biom J 2018;60:431–49. 10.1002/bimj.201700067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Colborn KL, Giorgi E, Monaghan AJ, et al. Spatio-Temporal modelling of weekly malaria incidence in children under 5 for early epidemic detection in Mozambique. Sci Rep 2018;8:9238 10.1038/s41598-018-27537-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Zinszer K, Verma AD, Charland K, et al. A scoping review of malaria forecasting: past work and future directions. BMJ Open 2012;2:e001992. 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Ferrao JL, Niquisse S, Mendes JM, et al. Mapping and modelling malaria risk areas using climate, socio-demographic and clinical variables in Chimoio, Mozambique. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:795. 10.3390/ijerph15040795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Kabaria CW, Molteni F, Mandike R, et al. Mapping intra-urban malaria risk using high resolution satellite imagery: a case study of Dar ES Salaam. Int J Health Geogr 2016;15:26. 10.1186/s12942-016-0051-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Diggle PJ, Tawn JA. Moyeed RJJotRSSSC. Model‐based geostatistics 1998;47:299–350. [Google Scholar]

- 93. Lee D. A comparison of conditional autoregressive models used in Bayesian disease mapping. Spat Spatiotemporal Epidemiol 2011;2:79–89. 10.1016/j.sste.2011.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Leroux BG, Lei X, Breslow N. Estimation of disease rates in small areas: a new mixed model for spatial dependence. statistical models in epidemiology, the environment, and clinical trials. Springer 2000:179–91. [Google Scholar]

- 95. Aguilar JB, Gutierrez JB. An epidemiological model of malaria accounting for asymptomatic carriers. Bull Math Biol 2020;82:1–55. 10.1007/s11538-020-00717-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Kimenyi KM, Wamae K, Ochola-Oyier LI. Understanding P. falciparum Asymptomatic Infections: A Proposition for a Transcriptomic Approach. Front Immunol 2019;10:2398. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Kleinschmidt I, et al. Use of generalized linear mixed models in the spatial analysis of small-area malaria incidence rates in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. Am J Epidemiol 2001;153:1213–21. 10.1093/aje/153.12.1213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Gething PW, Casey DC, Weiss DJ, et al. Mapping Plasmodium falciparum mortality in Africa between 1990 and 2015. New England Journal of Medicine 2016;375:2435–45. 10.1056/NEJMoa1606701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Ssempiira J, Nambuusi B, Kissa J, et al. Geostatistical modelling of malaria indicator survey data to assess the effects of interventions on the geographical distribution of malaria prevalence in children less than 5 years in Uganda. PLoS One 2017;12:e0174948 10.1371/journal.pone.0174948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Millar J, Psychas P, Abuaku B, et al. Detecting local risk factors for residual malaria in northern Ghana using Bayesian model averaging. Malar J 2018;17:343 10.1186/s12936-018-2491-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Giardina F, Kasasa S, Sié A, et al. Effects of vector-control interventions on changes in risk of malaria parasitaemia in sub-Saharan Africa: a spatial and temporal analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2014;2:e601–15. 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70300-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Rouamba T, Samadoulougou S, Tinto H, et al. Bayesian spatiotemporal modeling of routinely collected data to assess the effect of health programs in malaria incidence during pregnancy in Burkina Faso. Sci Rep 2020;10:2618 10.1038/s41598-020-58899-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Selemani M, Msengwa AS, Mrema S, et al. Assessing the effects of mosquito nets on malaria mortality using a space time model: a case study of Rufiji and Ifakara Health and Demographic Surveillance System sites in rural Tanzania. Malar J 2016;15:257 10.1186/s12936-016-1311-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Sewe MO, Ahlm C, Rocklöv J. Remotely sensed environmental conditions and malaria mortality in three malaria endemic regions in Western Kenya. PLoS One 2016;11:e0154204 10.1371/journal.pone.0154204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Bejon P, Williams TN, Nyundo C, et al. A micro-epidemiological analysis of febrile malaria in coastal Kenya showing hotspots within hotspots. eLife 2014;3:e02130 10.7554/eLife.02130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Belay DB, Kifle YG, Goshu AT, et al. Joint Bayesian modeling of time to malaria and mosquito abundance in Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis 2017;17:415 10.1186/s12879-017-2496-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Kifle MM, Teklemariam TT, Teweldeberhan AM, et al. Malaria risk stratification and modeling the effect of rainfall on malaria incidence in Eritrea. J Environ Public Health 2019;2019:1–11. 10.1155/2019/7314129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Nyadanu SD, Pereira G, Nawumbeni DN, et al. Geo-visual integration of health outcomes and risk factors using excess risk and conditioned choropleth maps: a case study of malaria incidence and sociodemographic determinants in Ghana. BMC Public Health 2019;19:514 10.1186/s12889-019-6816-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Chirombo J, Ceccato P, Lowe R, et al. Childhood malaria case incidence in Malawi between 2004 and 2017: spatio-temporal modelling of climate and non-climate factors. Malar J 2020;19 10.1186/s12936-019-3097-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Nguyen M, Howes RE, Lucas TCD, et al. Mapping malaria seasonality in Madagascar using health facility data. BMC Med 2020;18:26 10.1186/s12916-019-1486-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Ouédraogo M, Kangoye DT, Samadoulougou S, et al. Malaria case fatality rate among children under five in Burkina Faso: an assessment of the spatiotemporal trends following the implementation of control programs. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:1840 10.3390/ijerph17061840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Simon C, Moakofhi K, Mosweunyane T, et al. Malaria control in Botswana, 2008–2012: the path towards elimination. Malar J 2013;12:458 10.1186/1475-2875-12-458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Bisanzio D, Mutuku F, LaBeaud AD, et al. Use of prospective Hospital surveillance data to define spatiotemporal heterogeneity of malaria risk in coastal Kenya. Malar J 2015;14:482 10.1186/s12936-015-1006-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Ihantamalala FA, Rakotoarimanana FMJ, Ramiadantsoa T, et al. Spatial and temporal dynamics of malaria in Madagascar. Malar J 2018;17:58 10.1186/s12936-018-2206-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Mukonka VM, Chanda E, Kamuliwo M, et al. Diagnostic approaches to malaria in Zambia, 2009-2014. Geospat Health 2015;10 10.4081/gh.2015.330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Ikeda T, Behera SK, Morioka Y, et al. Seasonally lagged effects of climatic factors on malaria incidence in South Africa. Sci Rep 2017;7:2458 10.1038/s41598-017-02680-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Kamuliwo M, Kirk KE, Chanda E, et al. Spatial patterns and determinants of malaria infection during pregnancy in Zambia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2015;109:514–21. 10.1093/trstmh/trv049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. DePina AJ, Andrade AJB, Dia AK, et al. Spatiotemporal characterisation and risk factor analysis of malaria outbreak in Cabo Verde in 2017. Trop Med Health 2019;47:3 10.1186/s41182-018-0127-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Ssempiira J, Kissa J, Nambuusi B, et al. The effect of case management and vector-control interventions on space–time patterns of malaria incidence in Uganda. Malar J 2018;17:162 10.1186/s12936-018-2312-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Mirghani SE, Nour BYM, Bushra SM, et al. The spatial-temporal clustering of Plasmodium falciparum infection over eleven years in Gezira state, the Sudan. Malar J 2010;9:172 10.1186/1475-2875-9-172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Mwakalinga VM, Sartorius BKD, Mlacha YP, et al. Spatially aggregated clusters and scattered smaller loci of elevated malaria vector density and human infection prevalence in urban Dar ES Salaam, Tanzania. Malar J 2016;15:135 10.1186/s12936-016-1186-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Shaffer JG, Touré MB, Sogoba N, et al. Clustering of asymptomatic Plasmodium falciparum infection and the effectiveness of targeted malaria control measures. Malar J 2020;19:33 10.1186/s12936-019-3063-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Bousema T, Drakeley C, Gesase S, et al. Identification of hot spots of malaria transmission for targeted malaria control. J Infect Dis 2010;201:1764–74. 10.1086/652456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Ferrari G, Ntuku HM, Schmidlin S, et al. A malaria risk map of Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. Malar J 2016;15:27 10.1186/s12936-015-1074-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]