Abstract

Aim

To describe our response to the COVID‐19 emergency in a cancer centre to enable other nursing organizations to determine which elements could be useful to manage a surge of patients in their own setting.

Background

The COVID‐19 pandemic represents one of the most challenging healthcare scenarios faced to date. Managing cancer care in such a complex situation requires a coordinated emergency action plan to guarantee the continuity of cancer treatments for patients by providing healthcare procedures for patients, caregivers and healthcare professionals in a safe environment.

Procedures

We describe the main strategies and role of nurses in implementating such procedures.

Results

Nurses at our hospital were actively involved in COVID‐19 response defined by the emergency action plan that positively contributed to correct social distancing and to the prevention of the spread of the virus.

Implications for nursing and health policies

Lessons learned from the response to phase I of COVID‐19 have several implications for future nursing and health policies in which nurses play an active role through their involvement in the frontline of such events. Key policies include a coordinated emergency action plan permitting duty of care within the context of a pandemic, and care pathway revision. This requires the rapid implementation of strategies and policies for a nursing response to the new care scenarios: personnel redistribution, nursing workflow revision, acquisition of new skills and knowledge, effective communication strategies, infection control policies, risk assessment and surveillance programmes, and continuous supplying of personal protective equipment. Finally, within a pandemic context, clear nursing policies reinforcing the role of nurses as patient and caregiver educators are needed to promote infection prevention behaviour in the general population.

Keywords: Cancer Patients, COVID‐19 Pandemic, Health Policy, Mitigating Strategies, Nursing Policy, Nursing Response, Nursing Triage, Social Distancing

Introduction

The Chinese government declared the first outbreak of Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) in the city of Wuhan on December 31st 2019 (Zhu et al. 2020), and the World Health Organization (WHO) confirmed COVID‐19 as a global pandemic on March 11th 2020 (WHO 2020a). The first case of COVID‐19 in Italy was registered on February 21st 2020 and was followed by an exponential spread of the disease throughout the country, leading to the second fastest growing number of cases worldwide (Ministero della Salute 2020a). Given the challenges it poses, the COVID‐19 pandemic has been the most impactful global public health emergency of the last few decades, especially for social and healthcare organizations in the countries affected most by the spread of the virus (Thompson 2020).

Whilst prioritizing limited resources and supplies and maximizing their benefit for patients is essential under normal circumstances, it becomes vital for community survival during pandemic events such as the COVID‐19 emergency (Emanuel et al. 2020 ). Given their poor health status, comorbidities and immuno___suppressive conditions caused by both the disease itself and anti___cancer treatments, patients with cancer are more vulnerable to infections and may experience worse outcomes than other individuals with the virus (Allegra et al 2020; Jazieh et al 2020). As individuals at high risk for COVID‐19, it is essential for these patients to avoid infection (Wang and Zhang 2020, Xia et al. 2020). At the same time, however, they must continue their cancer treatment because interrupting therapy may, in itself, compromise outcome/survival (Ueda et al. 2020).

Nurses have been directly involved in the frontline of the COVID‐19 pandemic, managing/organizing patient care and rationalizing the use of resources (Catton 2020). Describing the nursing response to this globally challenging scenario could be helpful for cancer management and for the development of emergency preparedness action plans during future pandemic events.

Our hospital is a cancer research institute located in the Northern Italian region of Emilia___Romagna, which represents one of the Italian regions hit hardest by the virus. The centre covers a catchment area of 1__200__000 people and is the hub of a hub and spoke organizational model for cancer treatment and diagnosis in the Wide Catchment Area of Romagna (Area Vasta Romagna). About 27__000 cancer patients per year access our centre for diagnosis, treatment and follow___up. Currently, 5000 are undergoing active cancer treatment with chemotherapy/immunotherapy/hormone therapy or combined approaches, whilst 2224 are undergoing radiation therapy. Managing cancer treatments during the COVID‐19 pandemic required an emergency preparedness action plan and specific implementation strategies. The main site of the institute is in Meldola (Medical Oncology Ward, Day Service, Radiotherapy Unit and Nuclear Medicine Unit [diagnosis and therapy]), and 3 satellite sites located inside the hospitals of Forl__ (Onco___Hematology Day Service), Cesena (Onco___Hematology Day Service) and Ravenna (Radiation Therapy Service) (https://www.irst.emr.it). One hundred nursing staff are involved in cancer care; 86% female and 14% male; mean age 40__years; and mean length of time working in the area of oncology 7__years. All are registered nurses, 37% have a postgraduate nursing degree and 10% a masters in nursing sciences. There are 16 advanced nursing positions, that is, clinical nurse specialists, case managers, access device nurses and research and risk manager nurses.

The intent in sharing the details of our response to the COVID‐19 emergency in a cancer centre is to enable other nursing organizations to determine which elements of this planning might be useful for managing a surge of patients in their own setting.

The main goal of the emergency preparedness action plan is:

To minimize the overall risk of poor outcomes in patients with cancer treated in our centre by ensuring treatment continuity and by protecting patients, caregivers and healthcare professionals from the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS___CoV___2) infection.

Secondary objectives

To contribute to the control of the spread of infection in our geographical area by promoting social distancing through the education of healthcare workers, patients and their families;

To reduce the burden on patients with cancer with SARS___Cov___2 on public health organizations and the need for the use of critical resources through early detection, isolation measures and treatment of symptomatic individuals/cases.

Mitigating strategies implemented during the COVID‐19 pandemic

After the declaration of the first COVID‐19 case in Italy, a Crisis Communication team was set up on 23rd February 2020 at our Center by the Healthcare Administration Director and Board of Directors. The team was composed of the General and Healthcare Administration Directors, Risk Manager, Nursing Director, Logistics Manager, Training Office Manager, Information Technology Manager, Communications Officer and Prevention and Protection Manager. General healthcare crisis management principles and World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines for a COVID‐19 preparedness and response plan were adopted using multimodal implementation strategies at our institute (WHO 2020b). In the early phase of the pandemic, the search of emerging literature was aimed at finding peer___reviewed information needed to keep nursing teams and other healthcare professionals up___to___date in the following areas: disease physiopathology and symptoms, ways of person___to___person transmission; evidence or recommendations on infection prevention and control precaution measures; epidemiology, reusable equipment and environmental cleaning procedures, diagnostic tests, efficacy of personal protective equipment (PPE) and communication strategies in healthcare organizations during health emergency events. We searched PubMed for original articles and the most important infection prevention websites for guidelines (e.g. WHO, Ministero della Salute, Center for Disease Control). Nurses were actively involved in evaluating and translating recommendations into the emergency preparedness and response plan, and in implementing new institutional policies, protocols and procedures developed for the management of the COVID‐19 emergency. A clear communication chain was defined by the Crisis Communication team at all levels of the organization to ensure coordinated information flow. Multimodal strategies were adopted to implement action plan activities for each step of emergency preparedness and response. Details of the interventions made in response to the COVID‐19 emergency at our cancer centre are shown in Table__1.

Table 1.

Mitigating strategies in response to COVID‐19

|

Action Designation of Crisis Communications Team:

|

Related objective | To minimize the overall risk of poor outcomes protecting patients, caregivers and healthcare professionals from the SARS___CoV___2 infection | |

| Area of risk influenced | Patient, caregiver and employee safety, communication efficacy, health resource use | ||

| Adopted strategies and instruments for achieving goals | Multimodal implementation strategies for creating an institutional safety climate implementing policies and procedures based on the best available information | ||

| Communication instruments | Briefing, e___mail texting, phone, web___conference | ||

| Barriers for implementation/ challenges faced | Rapid changes of the epidemiological situation, disease uncertainty needing crisis management skills and response capacity to new unpredicted situations | ||

| Involved roles and stakeholders | Board of Directors, nursing leader, Risk Manager, Communications Officer, IT staff, Logistics staff, administrative staff, Training Office Manager, Prevention and Protection Manager | ||

|

Action Establishment of chain of communications:

|

Related objective |

|

|

| Area of risk influenced |

Communication efficacy, preparedness plan efficacy, patient, caregiver and employee safety, use of health resources |

||

| Adopted strategies and instruments for achieving goals |

Coordinated information flow of directive issues, with a top___down and bottom___up feedback approach; information derived from crisis monitoring and follow___up were used for evaluations and future decisions |

||

| Communication instruments | Briefing at all levels of organization, webinar, phone, email texting, intranet, electronic medical records, policies, guidelines, operational procedures, data___reporting (weekly report) | ||

| Barriers for implementation/ challenges faced | Training/coaching and briefing were necessary to promote adherence to all new communication instruments implemented during each step of crisis management, which was resource___consuming | ||

| Involved roles and stakeholders | Board of Directors, strategic nursing leader at different levels of organization, cancer service managers, IT staff, Communications Manager, healthcare professionals (doctors, nurses, laboratory technicians, radiologists, pharmacists), administrative staff, local authorities, research staff, local public hospitals, voluntary associations, patients and families, externalized service providers, pharmaceutical representatives for clinical trials | ||

|

Action

|

Related objectives | To minimize the overall risk of poor outcomes by protecting patients, caregivers and healthcare professionals from the SARS___CoV___2 infection | |

| Area of risk influenced | Patients, caregivers, healthcare professionals and environment safety, use of health resources | ||

| Adopted strategies and instruments for achieving goals | Multimodal implementation strategies: institutional safety culture and climate, training, coaching, education (employees, patients, caregivers) reminders at workplaces, direct observation and feedback, maintenance of enhanced hand hygiene programme, revision of frequency and products used for high level of environmental hygiene inside the hospital (surface cleaning and disinfection procedures; hospital waste disposal; reusable medical instrument reconditioning between patients) | ||

| Communication instruments | Briefing, email, intranet, webinar, video tutorials, posters, phone, patient and caregiver interviews, social media (Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, LinkedIn) | ||

| Barriers for implementation/ challenges faced |

Social distancing imposed by precaution measures made it necessary to find alternative training options to traditional ones, which was challenging during the early phase of the crisis At the beginning difficulties on providing PPE and hand hygiene products were observed. It required a revision of logistic policies for identifying solutions able to guarantee contingency of supply |

||

| Involved roles and stakeholders | Risk Manager, nursing leaders, infection prevention nurse, Training Office Manager, Prevention and Protection Manager, Logistics staff, Communications Officer, external service providers | ||

|

Action Revision of standard of care:

|

Related objective | To minimize the overall risk of poor outcomes in cancer patients treated in our centre by ensuring treatment continuity and by protecting patients, caregivers and healthcare professionals from the SARS___CoV___2 infection | |

| Area of risk influenced | Patient, caregiver and employee safety, patient health outcomes, use of resources | ||

| Adopted strategies and instruments for achieving goals |

Risk assessment to screen those with flu___like symptoms and refer them to their general practitioner for early communication, isolation and treatment for COVID‐19 to prevent severe disease; telephone triage of patients before planning their visit to hospital; triaging patients and their caregivers before their access to cancer services; Continuity of essential services, appropriate case management |

||

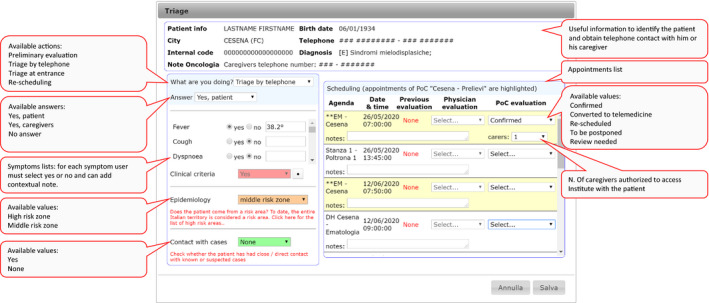

| Communication instruments | An ad hoc computerized triage tool to support healthcare professionals in the decision___making process and in documenting their evaluations (Fig.__1), EMRs, computerized patient agenda, phone, briefing, direct interview with patients/caregivers | ||

| Barriers for implementation/challenges faced | Useful but resource___ and time___consuming as training and coaching was necessary. Technology___related difficulties sometimes occurred | ||

| Involved roles and stakeholders | Risk manager, doctors, nurse leaders at different levels of organization and services, oncology nurses, medical radiology technicians, IT engineer, volunteers | ||

|

Action Reorganization of spaces |

Related objective | To promote social distancing and reduce the risk of person___to___person virus transmission | |

| Area of risk influenced | Patients, caregiver, employee and environment safety, use of health resources | ||

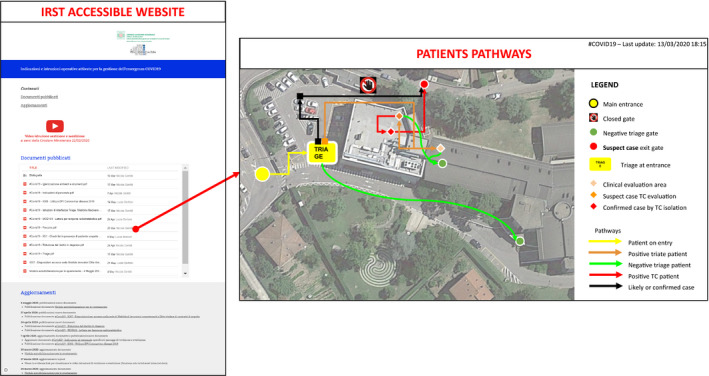

| Adopted strategies and instruments for achieving goals | Establishment of a separate and dedicated pathway inside the hospital for the clinical and instrumental assessment of suspected COVID‐19 cases; creation of separate itineraries within the hospital for administration staff and for healthcare professionals and patients (Fig.__2); reorganization of waiting rooms and common areas such as cafeterias and meeting rooms to favour social distancing; dedicated and easily noticeable stations in each cancer service containing PPEs and ready___to___use kits for surface cleaning and disinfection of reusable devices and surfaces between patients; controlling the access of lay caregivers accompanying patients to the healthcare environment to limit the spread of the virus by promoting social distancing and by reducing the number of people inside the hospital building; introduction of smart working for administration staff, | ||

| Communication instruments | Pathway signalling targets, reminders, posts for promoting social distancing and correct behaviour, phone information, triage station information, intranet, triage protocol, alert email signalling suspected cases to care teams | ||

| Barriers for implementation/ challenges faced | Weather caused difficulties for patient moving during the early phase, increasing stress between triaging nurses. Increase in internal assistance needed for patients with reduced mobility | ||

| Involved roles and stakeholders | Risk Manager, nurse leader, nurses, other healthcare professionals directly involved in patients care, Communications Officer, technical office personal | ||

|

Action Evaluations and follow___up of preparedness plan

|

Related objective | To detect COVID‐19 cases by nasopharyngeal swabs, early identification of individuals who had been in contact with COVID‐19___positive cases | |

| Area of risk influenced | Patient, caregiver and employee safety, risk communication between different care settings and services, early management of COVID‐19 disease | ||

| Adopted strategies and instruments for achieving goals | Monitoring of the efficacy of preventive strategies through surveillance | ||

| Communication instruments | Surveillance protocol and patient___screening programme, phone, email, patient agenda, google calendar | ||

| Barriers for implementation/ challenges faced | Planning and implementing such activities required communication skills, training and coordination within other routine activities | ||

| Involved roles and stakeholders | Nurse leader, surveillance nurse, research nurses, oncology nurses | ||

|

Action Accelerating priority research and innovation: Several COVID‐19 research projects were activated at our centre |

Related objective | To contribute to the identification of new treatments and prevention strategies for SARS___CoV___2 infection | |

| Area of risk influenced | Patient, caregiver and employes safety, research, standard of care | ||

| Adopted strategies and instruments for achieving goals | Maintenance of research activities was considered as a strategy gaining new information about the diagnosis and care of the disease | ||

| Communication instruments | Study protocols and related instruments, study flow___chart and participant agenda for study activity planning, email, Google calendar | ||

| Barriers for implementation/ challenges faced | Planning and implementing such activities required communication skills, training and coordination within other routine activities | ||

| Involved roles and stakeholders | Scientific director, research teams, strategic nurse leader, nurse coordinators, oncology nurses | ||

|

Action Staff management:

|

Related objective | ||

| Area of risk influenced |

Team communication Patient and healthcare professional safety Employee well___being Standard of care maintenance |

||

| Adopted strategies and instruments for achieving goals | Honest communication at all levels of organization, open discussion and listening approach, reciprocity, supporting professionals in dealing with sensitive issues | ||

| Communication Instruments | Briefing with small teams or individual interviews to discuss problematic issues related to case management, PPE, working extra shifts, social and psychological distress | ||

| Barriers for implementation/challenges faced |

During COVID‐19, schools and other public services for infants were closed, causing problems for families with children. Nursing shift planning had to deal with the absence of some nurses with young children; New triage services was managed based on the availability of nurses to work overtime; Finding economic solutions for rewarding such efforts was necessary New selection procedures were required to establish the phase two preparedness plan |

||

| Involved roles and stakeholders | Strategic nurse leader, oncology nurses, human resource manager, IT engineer, Provincial Nursing Council | ||

Contribution of nursing staff to the implementation of mitigating strategies

Implementation of the aforementioned strategies strongly impacted the organization and daily activity flow of the nursing staff throughout the cancer services of our centre. Effective communication was important for the successful coordination of the emergency plan activities. Nursing leaders played a key role in promoting effective communication at different levels of the organization between nursing teams of all cancer services and healthcare and administrative professionals. A top___down and bottom___up feedback approach was used to deal with the different issues raised by the COVID‐19 crisis, that is, staff and resource management and nursing workflow modification in response to the revised standard of care during the crisis. The communication chain for such issues consisted of direct communication between the command office, strategic nursing leader, nurse coordinators of cancer services, nursing teams, single professionals and vice versa. Phonecalls, email texting, web___conferencing, short briefings and direct interviews were the most widely used instruments to ensure good communication with nurses in all cancer services and with the satellite sites. Such instruments were useful for transmitting and receiving information about new institutional and nursing directives, training, COVID‐19 case evaluation and management, availability of nursing staff to work overtime to cover extra triage shifts and COVID‐19 surveillance services, and for monitoring the demand and supply of PPE and other medical equipment needed during the emergency. They also provided a means of discussing and finding solutions to other staff difficulties, for example, dealing with domestic arrangements for young nurses with small children. Furthermore, an online platform was set up by the Provincial Nursing Council to provide psychological support for nursing staff during the emergency period.

Patient agenda management and nursing triage

The work agenda of each cancer service was reviewed by oncologists to identify patients requiring undelayable healthcare procedures. Patients whose procedures could be postponed were contacted by doctors and their visits re___scheduled. Nurses were actively involved in managing the agenda of patients requiring undelayable procedures (i.e. consulting visits, cancer treatments and evaluations, patients enrolled in clinical trials), contacting them directly by phone. In accordance with triage criteria, after each phone interview oncologists were informed of suspected COVID‐19___positive patients. A risk___benefit assessment of these patients was then made to decide how to proceed. A telephone help___line managed by nurses was put at the disposal of the public to support, inform and educate patients and their families during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Three nursing triage stations (one for each satellite site) were implemented, whereas a triage tent was set up at the main entrance of the institute in Meldola, which has the highest influx of people. Triaging services were provided 24/7 at the Meldola site because it has an inpatient Medical Oncology Ward, and from Mondays to Fridays 7.00__a.m. to 7.00__p.m. at the 3 satellite sites. In Meldola, the Medical Oncology Ward nursing team provided a triaging service from 7.00__p.m. to 7__a.m. Nurses from all the cancer services of the institute were asked for their availability to cover extra shifts at the triaging stations. Of those who agreed, the most experienced were selected because of their ability to distinguish between COVID‐19 flu___like symptoms and cancer___related symptoms or cancer treatment___induce adverse effects. Triage nurses were all specifically trained on how to evaluate COVID‐19 symptoms and how to proceed in the event of a patient reporting such symptoms. They were also trained in the correct use of the computerized triaging instrument (Fig.__1). Volunteers from the local Civil Protection Unit helped to set up the tensile structure for triage and provided general assistance to patients and caregivers at the hospital entrance during daytime hours when there was a higher flow of people.

Fig. 1.

COVID‐19 computerized triage tool.

Managing patient care during pandemics

Specific policies and instructions were developed for the evaluation (patient triaging), management and isolation of suspected and laboratory___confirmed COVID‐19 patients and for environmental hygiene measures including a video tutorial on the correct use of PPEs, and reminders and posters for patient and family education. All new documents were presented to the nursing teams of the different cancer services and shared via the institutional intranet service. This enabled us to provide planned cancer treatments and diagnostic procedures whilst maintaining a safe environment for patients and healthcare professionals. Patients with mild symptoms and a laboratory___confirmed COVID‐19 diagnosis were isolated and treated, using additional precautions to prevent the spread of the disease to other patients and healthcare workers. Mapping of the triaged patient pathways at the main hospital site in Meldola is shown in Figure__2. There were no cases of severe COVID‐19 in our hospital during the 20___day observation period. Given the national standing of our institute as a cancer research centre, the care of patients enrolled in clinical trials is a part of our institutional commitments. During the COVID‐19 pandemic, nurses contributed to preserving the continuity of research activities and were involved in the activation of new clinical trials on COVID‐19 to further our understanding of the disease.

Fig. 2.

Mapping of the triaged patient pathways at the main hospital site in Meldola.

Measuring the impact

We analysed the data collected over a period of 20__days following the implementation of the above strategies to evaluate the contribution of the nursing staff and the impact of such strategies on nursing activities. During this period, 109 healthcare professionals were involved in patient assessments. Of these, 40 physicians were responsible for the preventive evaluations and re___evaluations and for the assessment of triage___positive patients. They appraised which health procedures were delayable and contacted patients to inform them of the need to reschedule visits to a later date. Healthcare professionals carried out a total of 6735 phone interviews with 2945 patients. Forty___five nurses were involved in triaging shifts at the triage stations (Meldola, Forl__, Cesena and Ravenna). During the 20___day period, they made 6000 evaluations of 2000 triaged patients. Twenty___six nurses and a number of administration personnel were involved in re___planning patient agendas.

Overall evaluation of mitigating strategies

An active surveillance programme using the COVID‐19 RT___PCR test (nasopharyngeal swab) was implemented at our centre to monitor the spread of the virus in hospitalized patients and healthcare workers. All healthcare workers and patients scheduled for admission to the Oncology Ward were tested. During the 20__days of active surveillance, a total of 28 patients with cancer from all care settings (including patients under follow___up) had laboratory___confirmed COVID‐19, only 2 of whom were admitted to the Medical Oncology ward. Four healthcare professionals who had no contact with these patients tested positive for COVID‐19 in the active surveillance programme and were thus quarantined. None of the patients or healthcare workers developed a severe form of COVID‐19. Known contacts of all confirmed cases were evaluated and all were negative. No additional COVID‐19 cases (either among patients or healthcare professionals caring for infected patients) were observed in the hospital after admission of the infected patients.

The impact of mitigating strategies on social distancing was evaluated by comparing the mean number of daily accesses of patients and caregivers to the hospital immediately before and during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Data for calculating the daily number of patients were extracted from the computerized hospital information system: before COVID‐19, the mean number of daily accesses of patients was 723 compared to 470 during the 20___day observation period, resulting in a 35% reduction in daily patient accesses.

Social distancing was promoted inside the hospital by adopting a multimodal information strategy aimed at reducing the number of people in the waiting rooms. During phone interviews, patients were informed of institutional policies during the COVOD___19 pandemic and of the importance of social distancing. They were also asked to reduce the number of caregivers accompanying them to the hospital as much as possible. This was obviously a sensitive issue because of the complex needs of cancer patients. Whilst in other healthcare settings the presence of accompanying caregivers may not always be necessary, in a cancer setting it is not easy for nurses to evaluate whether patients actually need someone to be with them during visits or treatments. We felt that well informed people would better accept precautionary measures and so chose to explain to patients and caregivers the twofold risk of being in crowded places, letting patients decide when they really needed a caregiver to accompany them. Our triage nurses perceived a substantial reduction (around two___thirds) in the number of accompanying caregivers. When interviewed during visits or by phone, both patients and carers readily accepted the revised standard of care and COVID‐19 precaution measures taken at our centre. However, it would be interesting to explore this issue with qualitative research to better understand what they appreciated the most and what could be done to improve the services in future times of crisis.

Discussion

The mitigating strategies implemented in our centre were based on specific recommendations of WHO, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Italian Ministry of Health for the control of COVID‐19, and also on general CDC guidelines (CDC 2020a; CDC 2020b; Ministero della Salute 2020b; WHO 2020c). We chose not to increase the number of nursing staff during phase one of COVID‐19 because this would have required additional training due to the highly specialized activities of the nurses in our centre. Furthermore, the introduction of new staff in times of emergency is not without problems. Our nurses faced the situation, well aware of the risk, and gave their best, showing generosity, competence and compassion. The nurses and other healthcare professionals directly involved in patient care were fully compliant with prevention procedures. Social distancing is one of the main recommendations of WHO aimed at preventing the spread of COVID‐19, and our nursing triage contributed to a 53% overall reduction in the presence of people (patients and caregivers) inside the hospital during the observation period. By promoting social distancing through strategies such as nursing triage and patient education, we believe that we substantially helped to reduce the spread of COVID‐19 in our geographical area. In fact, there have been no new cases of COVID‐19 in our hospital since these practices were adopted.

Implications for the future

The lessons learned whilst responding to phase one of the COVID‐19 pandemic have several implications for nursing and health policies in the future. A number of key policies are needed to facilitate the implementation of an emergency action plan in healthcare settings in response to a pandemic:

Health policies: The response to the COVID‐19 pandemic in Italy revealed a number of shortcomings, especially in the early stages of the emergency, probably related to the lack of awareness of the risk of infection among the population and healthcare professionals. There were also weaknesses in the nationally coordinated response, which resulted in different performances between regions and hospitals across the country (Carinci 2020; Volpato et al. 2020). Health policies must provide an emergency preparedness action plan for a coordinated management of future pandemic events (Armocida et al. 2020; Remuzzi & Remuzzi, 2020).

Co ordinated action plan and communication strategies had a substantial impact on the performance of the emergency response at our hospital. In the event of future emergency pandemics, nurses should be actively involved in developing and implementing health policies aimed at reducing the impact of pandemic events on the general population (Paterson et al. 2020; Wall & Keeling 2010). Rethinking patients paths, real___time surveillance, rapid risk assessment, access control, isolation, infection precautions and risk communication between different care settings represent key elements of the action plan (The Lancet Respiratory Medicine 2020, Cheng et al 2020). In healthcare organizations, administration and nursing management should work together as coordinated teams to develop and implement the emergency preparedness action plan in order to achieve common goals for patients, healthcare workers and the population in general.

Infrastructure and health informatics technology (all our sites are equipped with Wi___Fi, electronic medical records (EMRs) and Intranet where policies and procedures are available and accessible to healthcare professionals) played an important part in supporting our communication strategies and decisional processes, thus making multidisciplinary patient evaluations possible in real___time and enabling interventions via telemedicine (Rockwell & Gilroy 2020);

Health policies should be established to guarantee a continuous supply of PPEs for healthcare professionals and surgical masks for patients and accompanying caregivers (Chughtai et al. 2020). Although information on the type of PPE needed to protect healthcare workers and patients was somewhat conflicting during the early phase of the COVID‐19 pandemic, we chose to adopt a cautious approach in our institutional policies given the higher susceptibility of cancer patients to infection. Our policies have always stipulated the compulsory wearing of masks with filters to protect healthcare operators during aerosol___generating procedures, and surgical masks for all others inside the hospital. PPEs were distributed and instructions on how to wear them were provided by triage nurses to all people entering the hospital. Our logistics service guaranteed the continuous supply of masks and other PPEs.

Nursing organization: during a pandemic emergency, rapid and continuous updating of nursing scientific knowledge is needed, not as an intellectual exercise, but as a tool to promote initiative and nursing leadership, both mandatory to obtain an adequate nursing response. Rethinking nursing staff organization and activity workflows, healthcare paths and redistribution of personnel requires the rapid acquisition of new skills or the reinforcement of existing ones. Nurses play an important role in educating and promoting community health during pandemics. By using social networks, nurses can provide scientific and ethical communication and be a personal example of prudence and fairness, thus becoming a reference for citizens who need to be informed correctly (FNOPI 2020).

A widespread culture of safety among healthcare professionals and hospital infection prevention and control policies played an important role in the outcome of our action plan. In the event of future pandemics, it will be important to keep our attention and awareness on the real risk of infection in health organizations. The education of patients and caregivers on the correct behaviour that can help to reduce the risk of acquiring and transmitting infectious diseases must be an integral part of nursing cancer care (Fang et al. 2020; Fathizadeh et al. 2020; Nagesh & Chakraborty 2020).

It is worthy of note that the COVID‐19 health crisis also raised several ethical issues involving nurses. The first concerns the effect that interrupting health procedures after a revision of standard of care in response to a pandemic can have on overall patient outcome. During the emergency, appointments and patient evaluations were sometimes postponed after a careful assessment of the risk___benefit ratio. Nursing staff registered all such changes in patient records and re___scheduled them as soon as possible. Another ethical issue was the potential risk of violating patient privacy when having to communicate sensitive data to healthcare professionals in different care settings for cases of suspected or confirmed COVID‐19. To avoid this, a unique patient identifier code for each patient was generated in the EMRs and used by nurses to communicate between care teams, thus guaranteeing patient anonymity.

A cancer care setting requires nursing staff to have a specific set of relational skills. The response of our centre’s nurses to the COVID‐19 emergency highlights that such skills are a key element in ensuring effective communication between nurses and other healthcare professionals, and in creating a collaborative alliance with patients and caregivers to achieve common goals.

Conclusions

The nursing staff of our institute provided invaluable support in numerous areas during the first phase of the COVID‐19 pandemic, that is, patient evaluation and treatment agenda planning; patient and family support, information and education; and active participation in patient care, research and training. In addition to contributing to the efficacy of the mitigating strategies implemented during the emergency, they also played an active role in ensuring the appropriate use of health resources and in increasing the benefit for patients and the community. By limiting the number of cancer cases infected by COVID‐19, they contributed to reducing the pressure that such patients would otherwise have had on public hospitals and healthcare resources.

Author contributions

AZ, SM, NG, SP conceived the idea for and designed the paper

MB, MG, MR, NG collected and analysed the data

AZ, MB, NG, SP, MG, MR, MS drafted the manuscript

MA, SM critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content

All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript for submission

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Prof. Gianluca Catania for reading critically the paper, Gr__inne Tierney for editorial assistance, all nurses and healthcare professionals of our institute for their compliant behaviour in managing cancer care during the COVID‐19 pandemic. A special thanks goes to our patients, who had to forsake the proximity of their loved ones and caregivers to comply with social distancing.

Zeneli A., Altini M., Bragagni M., Gentili N., Prati S., Golinucci M., Rustignoli M.& Montalti S. (2020) Mitigating strategies and nursing response for cancer care management during the COVID‐19 pandemic: an Italian experience. International Nursing Review 67, 543–553

Sources of funding: This work received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not.

Conflict of interest: No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

References

- Allegra, A. , et al. (2020) Cancer and SARS___CoV___2 infection: diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Cancers (Basel), 12, 1581. 10.3390/cancers12061581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armocida, B. , et al. (2020) The Italian health system and the COVID‐19 challenge. Lancet Public Health, 5, e253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carinci, F. (2020) COVID‐19: preparedness, decentralisation, and the hunt for patient zero. BMJ, 368, bmj.m799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catton, H. (2020) Global challenges in health and health care for nurses and midwives everywhere. International Nursing Review, 67, 4___6. 10.1111/inr.12578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC (2020a). Clinical Care Guidance for Healthcare Professionals about Coronavirus (COVID‐19). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019‐ncov/hcp/clinical‐care.html (accessed on 3rd May 2020). [Google Scholar]

- CDC (2020b). Interim Clinical Guidance for Management of Patients with Confirmed Coronavirus Disease (COVID‐19). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019‐ncov/hcp/clinical‐guidance‐management‐patients.html (accessed on 3rd May 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H.Y. , Li, S.Y. & Yang, C.H. (2020) Initial rapid and proactive response for the COVID‐19 outbreak ___ Taiwan's experience. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association, 119, 771___773. 10.1016/j.jfma.2020.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chughtai, A.A. , et al. (2020) Policies on the use of respiratory protection for hospital health workers to protect from coronavirus disease (COVID‐19). International Journal of Nursing Studies, 105, 103567. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel, E.J. , et al. (2020) Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of COVID‐19. New England Journal of Medicine, 382, 2049___2055. 101056/NEJMsb2005114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Y. , Nie, Y. & Penny, M. (2020) Transmission dynamics of the COVID‐19 outbreak and effectiveness of government interventions: A data___driven analysis [published online ahead of print. Journal of Medical Virology, 92, 645___659. 10.1002/jmv.25750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fathizadeh, H. , et al. (2020) Protection and disinfection policies against SARS___CoV___2 (COVID‐19). Le Infeziioni in Medicina, 28, 185___191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FNOPI (2020) Manifesto deontologico per la pandemia COVID‐19. Available at: https://www.fnopi.it/2020/04/20/covid‐manifesto‐deontologico‐infermieri accessed 13th April 2020 . [Google Scholar]

- Jazieh, A.R. , et al. (2020) Outcome of oncology patients infected with coronavirus. JCO Global Oncology, 6, 471___475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministero della Salute (2020a) Covid 19 ___ Ripartizione dei contagiati per provincia ___ 12/05/2020 ore 17. Available at: http://www.salute.gov.it accessed 12th May 2020 . [Google Scholar]

- Ministero della Salute (2020b) Raccomandazioni per la gestione dei pazienti oncologici e onco___ematologici in corso di emergenza da COVID‐19. Available at: http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/nuovocoronavirus/dettaglioNotizieNuovoCoronavirus.jsp?lingua=italiano&menu=notizie&p=dalministero&id=4200 accessed 13th April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nagesh, S. & Chakraborty, S. (2020) Saving the frontline health workforce amidst the COVID‐19 crisis: Challenges and recommendations. Journal of Global Health, 10, 010345. 10.7189/jogh-10-010345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson, C. , et al. (2020) Oncology nursing during a pandemic: critical reflections in the context of COVID‐19. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 36, 151028. 10.1016/j.soncn.2020.151028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remuzzi, A. & Remuzzi, G. (2020) COVID‐19 and Italy: what next? Lancet, 395, 1225___1228. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30627-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockwell, K.L. & Gilroy, A.S. (2020) Incorporating telemedicine as part of COVID‐19 outbreak response systems. American Journal of Managed Care, 26, 147___148. 10.37765/ajmc.2020.42784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Lancet Respiratory Medicine (2020) COVID‐19: delay, mitigate, and communicate. Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 8, 321. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30128-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, R. (2020) Pandemic potential of 2019___nCoV. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 20, 280. 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30068-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda, M. , et al. (2020) managing cancer care during the COVID‐19 pandemic: agility and collaboration toward a common goal. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 20, 1___4. 10.6004/jnccn.2020.7560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpato, S. , Landi, F. & Incalzi, R.A. (2020) A frail health care system for an old population: lesson from the COVID‐19 outbreak in Italy. The Journals of Gerontology Series A Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 1___2. 10.1093/gerona/glaa087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall, B.M. & Keeling, A.W. (2010) Nurses on the Front Line: When Disaster Strikes, 1878___2010. Springer Publishing Company, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H. & Zhang, L. (2020) Risk of COVID‐19 for patients with cancer. Lancet Oncology, 21, e181. 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30149-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2020) WHO announces COVID‐19 outbreak a pandemic. Available at: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health‐topics/health‐emergencies/coronavirus‐covid‐19/news/news/2020/3/who‐announces‐covid‐19‐outbreak‐a‐pandemic accessed 13th April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2020b). 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019___nCoV): STRATEGIC PREPAREDNESS AND RESPONSE PLAN. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/strategic‐preparedness‐and‐response‐plan‐for‐the‐new‐coronavirus / (accessed 13th April 2020). [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2020c) Country & Technical Guidance ___ Coronavirus disease (COVID‐19). Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel‐coronavirus‐2019/technical‐guidance‐publications accessed 13th April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Y. , et al. (2020) Risk of COVID‐19 for patients with cancer. Lancet Oncology, 21, e180. 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30150-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, N. , et al. (2020) A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. New England Journal of Medicine, 382, 727___733. 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]