Abstract

Objectives

The capability and capacity of the primary and community care (PCC) sector for dementia in Singapore may be enhanced through better integration. Through a partnership involving a tertiary hospital and PCC providers, an integrated dementia care network (CARITAS: comprehensive, accessible, responsive, individualised, transdisciplinary, accountable and seamless) was implemented. The study evaluated the process and extent of integration within CARITAS.

Design

Triangulation mixed-methods design and analyses were employed to understand factors underpinning network mechanisms.

Setting

The study was conducted at a tertiary hospital in the northern region of Singapore.

Participants

We recruited participants who were involved in the conceptualisation, design, development and implementation of the CARITAS Programme from a tertiary hospital and PCC providers.

Intervention

We used the Rainbow Model of Integrated Care-Measurement Tool (RMIC-MT) to assess integration from managerial perspectives. RMIC-MT comprises eight dimensions that play interconnected roles on a macro-level, meso-level and micro-level. We administered RMIC-MT to healthcare providers and conducted in-depth interviews with key CARITAS stakeholders.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

We assessed integration scores across eight dimensions of the RMIC-MT and factors underpinning network mechanisms.

Results

Compared with other dimensions, functional integration (mechanisms by which information and management modalities are linked) achieved the lowest mean score of 55. Other dimensions (eg, clinical, professional and organisational integration) scored about 70. Presence of inspiring clinical leaders and tacit interdependencies among partners strengthened the network. However, the lack of structured documentation and a shared information-technology platform hindered functional integration.

Conclusion

CARITAS has reached maturity in micro-levels and meso-levels of integration, while macro-integration needs further development. Integration can be enhanced by assessing service gaps, increasing engagement with stakeholders and providing a shared communication system.

Keywords: geriatric medicine, public health, health services administration & management

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The strengths of this evaluation included the use of mixed methods—drawing on both quantitative and qualitative methods to generate insights.

Analyses by three coders minimised the bias of qualitative research.

However, sampling of interview participants was conducted through the recommendations of a managerial staff and could have skewed the selection.

Additionally, 48% of the participants did not complete the Rainbow Model of Integrated Care Questionnaire which may limit the representativeness of the responses.

Introduction

With ageing populations and more multi-morbidity, managing chronic and complex patients is a critical task for health systems. Care integration has been advocated as an approach to improving access to quality and continuity of health services.1–4 Integrated care involves coordination of care services across different levels and sites so that recipients of care experience continuity according to their needs and preferences. Recent studies on the effects of integrated care have been mixed. While some studies reported reduced hospital admissions, better quality of life and patient satisfaction,5–7 others showed little effect on hospital utilisation or mortality8 9 or increased nursing home admissions.10

There are several explanations for such contrasting findings. First, there are inherent difficulties in evaluating integrated care with a reductionist randomised controlled methodology.11 Compared with single interventions, care integration involves multiple components, layers and outcomes.11 Thus, evaluation of such a complex approach needs to consider the context of the composite intervention and the interaction between different contextual factors beyond merely assessing one or few quantitative outcomes.11 Second, the time needed to experience and assess outcomes in integrated care exceeds the usual duration of most studies. Multiple or mixed methods enable more comprehensive data collection to evaluate the maturity and impact of integrated care. Third, integrated care as a concept is ambiguous as it encompasses a range of meanings.2 3 12–14 The lack of a conceptual framework results in paucity of measures to assess the extent and quality of integrated care.

The Rainbow Model of Integrated Care (RMIC) was conceived to provide a comprehensive framework and taxonomy of integrated care based on principles derived from primary care.15 16 An initial framework was developed from literature reviews, further refined and validated Delphi technique with international experts and practitioners of integrated care from 11 countries.15 17 RMIC comprises eight dimensions structured along macro-levels, meso-levels and micro-levels, which can be contextualised to any integrated care setting.18 It has been adopted as a conceptual framework to evaluate integrated care from managerial perspectives.17 18

Beyond a conceptual framework, we also endeavour to understand how integrated care programmes achieve intended outcomes. Existing studies have outlined strategies to integrate person-centred services. Within a provider team, strategies include ensuring care coordination and continuity through regular team meetings,19 shared information and communication technology system and effective data management,4 20 strong leadership,4 and an organisational culture that supports accountability and shared decision-making.4 Externally, communication between providers is crucial to achieve integration.4 20 Funding incentives for providers could also foster greater commitment and sustain success.4 21 Lastly, eliciting the preferences of individuals and fostering mutual trust and responsibility are crucial to achieving person-centred and integrated care.22

We evaluated the process and determinants of integration in a dementia care network. Using the RMIC Measurement Tool (RMIC-MT), we evaluated the level and extent of integration. We also analysed the contextual factors and workings that underlie integration, and identify strategies for improvement and scaling-up. The study adds to extant knowledge on integrated care systems for patients with complex needs such as dementia, and provide important insights for the design, development and implementation of integrated care programmes.

Methods

This study is the first phase of a mixed-methods evaluation of the CARITAS Programme to examine the extent of integration in the network. The second phase which examines care recipients’ experiences with the network and assesses clinical outcomes will be separated. We used the Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence checklist when writing our report.23

RMIC framework

RMIC structures integrated care along macro-levels, meso-levels and micro-levels. At the macro-level, system integration refers to the linkages and visibility of the partnership formed between the healthcare system and external environment. At the meso-level, organisational integration refers to network mechanisms between different organisations, and professional integration refers to partnerships between different professionals in the healthcare system. At the micro-level, clinical integration refers to the coordination of patient care services across different professionals in the healthcare system. Functional and normative integration link the macro-levels, meso-levels and micro-levels of integration. The former refers to key support functions and activities by which financing, information and management modalities are linked. The latter refers to essential social and cultural factors (eg, shared mission, vision and values) within the system. The RMIC also includes person-focused and population-based perspectives to guide better coordination of services across care continuum. Person-focused care reflects a biopsychosocial health approach and considers personal preferences and needs, while population-based care requires healthcare be provided according to health profiles and needs of a defined population.

Intervention/programme

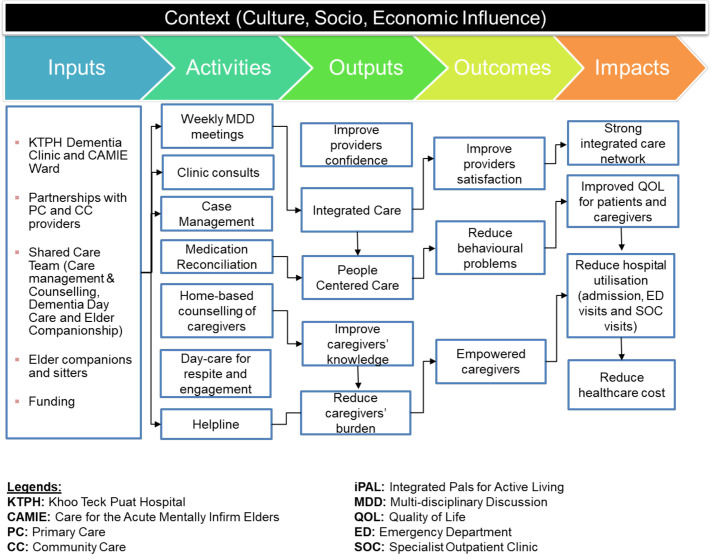

CARITAS was established as a dementia care network in 2012 within Singapore’s northern Regional Health System.18 The acronym CARITAS signifies: comprehensive, accessible, responsive, individualised, transdisciplinary, accountable and seamless care for persons with dementia (PWD).24 25 CARITAS aims to: (1) enhance the quality, capacity and efficacy of dementia care through vertically and horizontally integrated team-based care with regular case conferencing, partnerships between the tertiary hospital and primary and community care (PCC); (2) increase the capability of PCC to care for PWD through regular training, shared care and case conferencing; and (3) empower caregivers to care better for PWD through caregiver training programmes and a direct helpline. The model was developed based on the concept of integrated practice units (IPU). IPU embodies concepts of value-based care in organising care around a condition and/or population, shared decision-making, regular team meetings and responsibility for the full cycle of care for the condition.26 Figure 1 depicts the CARITAS’ logic model.

Figure 1.

A logic model of CARITAS. CAMIE, care for the acute mentally infirm elders; CARITAS, comprehensive, accessible, responsive, individualised, transdisciplinary, accountable and seamless; CC, community care; ED, emergency department; KTPH, Khoo Teck Puat Hospital; MDD, multi-disciplinary discussion; PC, primary care; QOL, quality of life; SOC, specialist outpatient clinic.

Study design

We applied a triangulation mixed-methods approach to combine the insights obtained from administering RMIC-MT, conducting ethnographic observations and semi-structured interviews. Quantitative and qualitative data were collected concurrently and analysed separately, but compared and contrasted using triangulation.

Quantitative data

Forty-nine healthcare professionals from CARITAS were invited via email to participate. A reminder was sent after 3 months. The questionnaire, averaging 30 min to complete, included a participant information sheet and consent, capturing demographics and the RMIC-MT. RMIC-MT comprised 62 items grouped into eight dimensions with each item rated on a 5-point Likert Scale (from never to all the time). An additional option (not sure/don’t know) was provided if participants felt inadequate to provide a response. Values from 0 to 100 were assigned to each point of the Likert Scale and mean scores were computed across all dimensions and respondents. We excluded entries with >30% missing data from analyses. Higher scores indicated higher levels care integration. Descriptive data and mean score were computed using Stata V.12.

Qualitative data

To better understand the activities of CARITAS, researchers (MN, NHLH and IC) observed consultations and discussions (n=14)27 in ambulatory clinics at the tertiary hospital, multi-disciplinary meetings, primary care clinic and teleconsultations. Observers were inconspicuous and did not influence the sessions. Field notes were recorded after each observation session using a guide (online supplemental appendix 1).

bmjopen-2020-039017supp001.pdf (116.2KB, pdf)

Additionally, we conducted semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders of CARITAS (n=17) to understand the programme workings and outcomes determinants. We included participants who were involved in the conceptualisation, design, development and implementation of the programme. Those who had resigned were excluded. Participants were selected using purposive sampling28 to have a mix of healthcare professionals from different settings and with different periods of involvement. Interview questions were developed based on the RMIC dimensions including care coordination (clinical integration), how professionals worked together (professional integration), financial and information management (functional integration) (online supplemental appendix 2). Interviews averaged 67 (range 42–93) min, were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Numbered identifiers were assigned to participants to protect their identities, with prefixes ‘T’ (from the tertiary hospital) and ‘P’ (PCC providers). After each interview, team members debriefed and created summary notes. Analysis was done inductively through thematic coding and deductively through classifying data into initial themes (NVivo V.11). Team members (MN, NHLH and IC) developed a shared codebook to document the initial themes and definitions, which were iteratively refined into prominent themes. These final themes were subsequently organised according to the eight RMIC dimensions of integration.

Data triangulation

Through rigorous discussions, qualitative themes were classified accordingly to provide insights on the quantitative results. The triangulated findings were subsequently presented to CARITAS stakeholders at a meeting to assess their validity. Feedback was used to refine the categorisation of themes and interpretation of results.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and their family caregivers were not involved in the design and conduct of this phase of the study, which was focused on evaluating the organisation of CARITAS care network and extent of integration from care providers’ perspectives. As such, the findings will primarily be disseminated to healthcare professionals and providers, not patients and their families. Findings are intended to inform care integration and delivery and will not directly result in any change to patient care.

Results

Rainbow Model of Integrated Care-Measurement Tool

Forty-nine healthcare participants came from the tertiary hospital (24.5%), volunteer welfare organisations (VWO) (53.1%), a primary care provider (8.16%) and national agency (14.3%). Twenty-seven (55.1%) attempted the questionnaire, 2 (7.41%) did not complete and 12 (44.4%) had >30% missing data. Majority (66.7%) opted to be anonymous. The final analysis comprised 13 respondents (48.1%) from 7 organisations—tertiary hospital (38.5%), VWO (30.8%), primary care provider (23.0%) and national agency (7.7%). Majority were tertiary hospital doctors (38.5%) with >1 year of involvement in CARITAS (84.6%) (table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of RMIC-MT respondents (n=13)

| Variables | N (%) |

| Profession | |

| Doctor | 5 (38.5) |

| Nurse | 3 (23.0) |

| Allied health | 3 (23.0) |

| Administrator | 2 (15.5) |

| Work setting | |

| Tertiary hospital | 5 (38.5) |

| Primary care provider | 3 (23.0) |

| Voluntary welfare organisation | 4 (30.8) |

| National agency | 1 (7.70) |

| Years of involvement | |

| <6 months | 0 (0.00) |

| 6 months–1 year | 2 (15.4) |

| >1 year | 11 (84.6) |

RMIC-MT, Rainbow Model of Integrated Care-Measurement Tool.

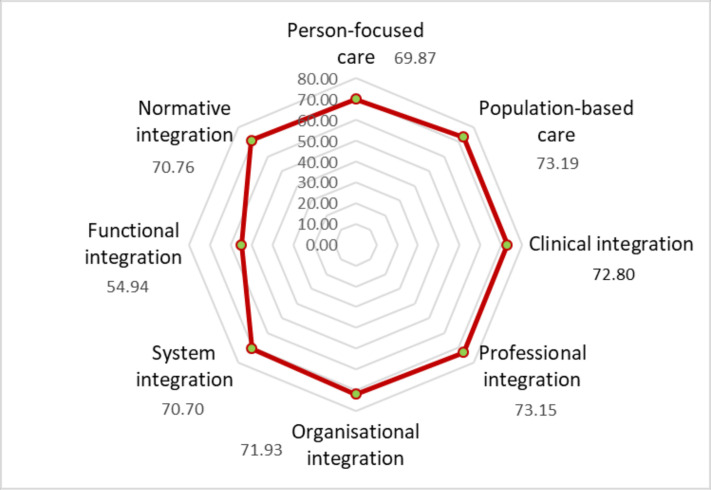

Most dimensions achieved scores averaging 70/100 (figure 2). Population-based care scored the highest (73.19), followed by professional (73.15), clinical (72.80) and organisational integration (71.93). Functional integration scored the lowest (54.94).

Figure 2.

Scores of RMIC’s eight dimensions of integration. RMIC, Rainbow Model of Integrated Care.

Ethnographic observation and in-depth interviews

Based on the observation notes, a typical patient’s journey was charted which provided initial understanding into the interventions available at CARITAS and how members worked across settings within the system. Doctors (37.0%) from the tertiary hospital (53.0%) with >4 years of involvement (58.0%) comprised the larger proportion of participants in the semi-structured interviews (table 2). A small proportion of themes derived from in-depth interviews overlapped with those of observational notes, which described a patient’s journey at various settings in the network. Themes regarding the background of the interview and reasons for their involvement in CARITAS were not classified into the eight RMIC dimensions. Relevant interview quotes corresponding to the RMIC-MT dimensions are summarised in table 3.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of respondents for qualitative interviews (n=17)

| Variables | N (%) |

| Profession | |

| Doctor | 6 (37.0) |

| Nurse | 3 (19.0) |

| Allied health | 4 (25.0) |

| Administrator | 3 (19.0) |

| Work setting | |

| Tertiary hospital | 9 (53.0) |

| Primary care provider | 2 (12.0) |

| Voluntary welfare organisation | 5 (29.0) |

| National agency | 1 (6.00) |

| Years of involvement | |

| <1 year | 3 (18.0) |

| 1–2 years | 1 (6.00) |

| 2–3 years | 3 (18.0) |

| 3–4 years | 0 (0.00) |

| 4–5 years | 6 (29.0) |

| >5 years | 4 (29.0) |

Table 3.

Summary of key themes across eight dimensions of the RMIC-MT

| Dimension | Key themes | Quotes |

| Population-based care | CARITAS was developed to better care for increasing needs of PWD and caregivers in Singapore | The objectives of CARITAS were:

|

| Classification of patients was based on a biopsychosocial model and the need for caregiver support |

|

|

| Family physicians were not keen to look after PWD as it is a complex condition that requires specialised expertise and resources |

|

|

| Professional integration | Clinical leaders in the network were dedicated, inspiring, knowledgeable and respectable |

|

| Mutual interdependencies existed between professionals in the network |

|

|

| Clinical integration | Service providers worked closely with one another to provide a range of services to clients |

|

| Care was expedited |

|

|

| Not all partners were always present at meetings |

|

|

| Cases were not discussed when partners were not around |

|

|

| Protocols for care process and criteria for recommendations to services were not documented formally, while they seemed to be understood by the working team |

|

|

| Organisational integration | Before initiation of the network, an influential clinical leader was able to link up with various organisations and those in leadership positions |

|

| There was a workflow for patient care linking various organisations together, despite not being documented formally |

|

|

| Less involvement from senior management among partners’ organisations |

|

|

| Normative integration | CARITAS’ objectives were not clearly and consistently conveyed to community partners, especially new staff over time |

|

| Some original intent waning over time |

|

|

| Primary care’s engagement was separate from that of other community partners |

|

|

| System integration | Increase in media advocacy on aged care issues |

|

| Increase in government funding and support on aged care |

|

|

| Person-focused care | Adopt a biopsychosocial team-based approach |

|

| Clients not aware of CARITAS network or how the hospital worked with community partners |

|

|

| Only a small group of caregivers regularly attend caregiver support sessions |

|

|

| Functional integration | High staff turnover among community partners |

|

| Channelling of finances to tertiary hospital reflects the notion that care is prioritised in hospital over community |

|

|

| Lack of IT platform for information sharing |

|

|

| Lack of sharing of performance indicators |

|

|

| Inadequate training for community partners |

|

Participants were given identifiers numbering 001–017, with ‘T’ referring to participants from the tertiary hospital and ‘P’ referring to those from primary and community care providers.

CARITAS, acronym of the integrated care network (comprehensive, accessible, responsive, individualised, transdisciplinary, accountable, seamless); CCMS, common case management system; FTE, full-time equivalent; IT, information technology; KPI, key performance indicators; MDM, multi-disciplinary meeting; PWD, persons with dementia; RMIC-MT, Rainbow Model of Integrated Care-Measurement Tool.

Population-based care

This dimension scored highest as CARITAS was conceived specifically to address the growing burden of dementia in Singapore29 and focused on building the dementia capabilities of PCC partners. PWD were admitted into the programme based on disease severity and extent of caregiver support. Stratification of patients, which enabled care to be delivered appropriately in PCC settings, resulted in better distribution of patients and care resources. Prior to CARITAS, primary care physicians lacked experience and expertise caring for PWD. The CARITAS team provided regular training, case conferences and teleconsultation via video conferencing to build competence of this group of community stakeholders. They appreciated the avenue for direct access to hospital dementia specialists for real-time advice. With increased capability and capacity of primary care for PWD, this freed up the tertiary hospital’s resources to attend to patients with more complex and specialised needs.

Professional integration

This dimension assessed the presence of dedicated clinical leaders and mutual professional interdependencies. The leaders were described to be ‘respectable, experienced, knowledgeable, always present and instrumental’ (ALL). Members felt supported and understood when discussing patients which increased their confidence to care for PWD. It also enabled them to possess greater responsibility for their patients, resulting in a higher level of professional integration.

Additionally, community partners participated regularly at interdisciplinary meetings where tertiary hospital referred patients to relevant community partners who would then update the team regularly on the patients. The opportunity for face-to-face communication served as a bridge between the tertiary hospital and community partners, and concurrently allowed partners to learn from each other. Consequently, strong interdependencies developed between community partners and hospital specialists, and the latter was able to tap on community resources such as home-care and centre day-care services to complement hospital care. Community partners expressed that the team members were ‘helpful to one another’, ‘consistent’, ‘committed’ and ‘intrinsically motivated’ (T001, P001, P002), hence fostering professional trust. They also reported that members received ‘good support from the network’ and ‘regular feedback among team members’ who ‘had the same objectives’ and ‘no competition mindset’ (T009, P006, P007). Having a shared goal to improve care for PWD promoted a sense of accountability which enhanced professional integration.

Clinical integration

Members rated their performance on coordination, referral and follow-up of patients, involvement of patients in care planning and decisions, and if the network provided comprehensive services.

The structure of the CARITAS team was flat. Instead of the CARITAS lead directing unilaterally, team members took ownership of their patients and developed individualised care plans although through shared decision-making. As a result, even when the lead was not present, discussions proceeded smoothly with each team member taking turns to update and discuss their cases. While diversity of opinions was encouraged, shared decision-making was upheld and clinical integration maintained.

The strength of CARITAS laid in regular team meetings enabling two-way information flow and provision of a comprehensive range of services to address the multi-faceted needs of PWD and their caregivers. The relationships built through face-to-face meetings were invaluable in facilitating interprofessional exchanges and empowered members to manage more complex patients.

Furthermore, the integration of staff members across care settings allowed patients to expediently tap on a comprehensive suite of services from hospital-based interventions to community centre-based care and home-care, coupled with a phone helpline to cater to patients’ ad hoc needs. As a member expressed, “It does help in terms of let’s say we refer to the day care, the day care does try (…) to expedite some of the cases” (T004). By working in a coordinated manner, the integrated CARITAS service delivered comprehensive and continued care of a higher standard.

However, there were also factors impeding clinical integration. First, not all members, especially those from the community, could be present at every meeting due to commitments at their primary workplaces. Thus, case discussions would be delayed, or be held outside the multi-disciplinary meeting (MDM) through less personable communication channels such as exchange of emails and messages. Unsurprisingly, members opined their objectives were not met when other partners caring for same patient did not attend meetings. Second, some members indicated the need for operational guides and protocols, particularly clearer criteria for referral to various services. While members with more years in the team appeared to have an implicit understanding of the criteria, newer members felt less confident and were concerned about inappropriate referrals.

Organisational integration

This dimension examined how well organisations collaborated to provide care and whether there was a shared understanding about care strategy. It also explored if there was effective leadership to connect across organisations. Having an influential clinical leader and the presence of a patient care workflow provided the foundation of organisation integration in CARITAS.

Since the inception of CARITAS, the clinical leader helped to form the network of organisations by enunciating a shared mission and aligning care goals. Despite team members coming from different care settings, the common vision to provide seamless care for PWD and their families with consistent bidirectional information flow enabled collaborative and integrated person-centric care. There was tacit understanding of the workflow involving different member organisations with clear delineation of roles. Therefore, each member understood his work scope and responsibilities, empowering smooth operations and team integrity.

However, over time, staff turnover and change in the leadership of partnering organisations with attendant shifts in priorities have negatively impacted organisational integration. Engagement with the leadership of partnering organisations to align goals and discuss strategies was also observed to decrease over the years, which impeded understanding and support towards the network’s shared objectives. Members of partnering organisations remarked that without consistent strong support from their employers, they felt less empowered to extend their commitment to the CARITAS’ activities beyond their defined roles, especially when faced with heavy responsibilities in their own organisations. As a result, some members were less inclined to attend weekly meetings or only attended when they needed to discuss their cases, and there were also instances of decreased participation in learning opportunities such as case-based learning and continuing education initiatives.

Normative integration

We examined if members understood the vision and mission of CARITAS and if their desire and ability to work together. Although senior members were generally clear on the initiative’s objectives, newer members were less able to do so. They shared that the objectives were not consistently conveyed; a member remarked “because when I join that time, nobody tell[s]me what is the objective of Caritas network” (P001) and another shared, “we remind what is the vision and yah I don’t think we do enough especially when people move on” (P005).

Another issue lay in the primary care team not being able to participate regularly at team meetings. The primary care team worked mainly with the tertiary hospital team. As such, information concerning patients from primary care was often conveyed through hospital team members to community partners at the MDM. This inadvertently reduced the need for face-to-face interaction between the primary care team and community partners. There were hence diminished opportunities for forging a shared identity which is instrumental to normative integration.

Systems integration

Systems integration assessed the presence of a favourable socioeconomic and political milieu for advancing CARITAS as a viable model of integrated care. Given the thrust to advance quality care for older persons in the country, CARITAS presents a working model of integrated care for PWD and their families who often present with complex medical and social needs. With increased community-based resources to enhance care for older adults, CARITAS’ ability to tap on these resources demonstrates its ability to synergise with the healthcare system at large to secure continuity and scalability. However, as the main focus has been day-to-day patient care, CARITAS has yet to prioritise efforts to increase awareness of its work and to translate to other regions.

Person-focused care

This dimension assessed the degree of patients’ needs being explicit in care delivery, and patients being educated and involved in planning and organising of care. The CARITAS team adopted a biopsychosocial care approach and emphasised individualised relationship-centred care across the disease continuum. As a member remarked, “there is the same team who knows the patient, to be taking care of them as the primary team (…) We really get to know them, how to care for them and what are the reasons why they have certain behaviours before we can really give proper advice or treatment” (T001). The holistic and individualised approach was shared by another member who elaborated, “we will look at things like the type of dementia, existing symptoms, the needs that they have in terms of both physical and psychological…and the impact on their social circles. Then we will study their families or their support network (…)” (T002).

However, while the patients received person-centred care, they lacked awareness of CARITAS as an integrated care team and how they benefited from the services afforded by the network’s partners. They knew little of which agencies were in the network and how the hospital partnered them to deliver care. Engagement with the family caregiver support group dwindled with time as only a small number of caregivers regularly attended these sessions out of a large repository of caregivers in the network.

Functional integration

Functional integration investigates the extent financial and other incentives are used to improve teamwork, coordination and continuity of care. Functional integration had the lowest score which could be attributed to staff turnover, the financing system favouring tertiary care and the lack of a shared platform for documentation.

Significant staff turnover, especially among community partners affected the stability of the team. Manpower shortage in community care compromised partners’ attendance at weekly team meetings which in turn impacted care. Moreover, new staff lacked experience and skills in managing more complex problems and needed time to become proficient with the workings of the CARITAS.

Funding for CARITAS was channelled primarily to the tertiary hospital which shaped the notion that leadership and management was concentrated within tertiary care instead of being distributed across care settings. The initiative was perceived to be driven by the hospital which embraced accountability and setting of key performance indicators. As such, other partnering organisations tended to assume less accountability which compromised functional integration.

The absence of a common information technology (IT) platform for structured information sharing between hospital and community partners also impeded functional integration. As team members caring for the same patient could not access each other’s records, much time was spent during meetings to update members about patients’ progress instead of discussing how best to improve care. The lack of shared documentation of previous and ongoing services for patients also risked duplication of services. Even when a shared IT platform was piloted in the course of CARITAS implementation, limitations in the system’s usability and capability restricted its uptake among members of the team.

Discussion

This study assessed the process and extent of integration of the CARITAS dementia care network. We adopted a mixed-methods approach by triangulating the RMIC-MT with in-depth interviews and ethnographic observation. All but one RMIC dimension achieved a mean score of ~70/100—highest for population-based (73.19) and lowest for functional integration (54.94). Qualitative findings revealed contextual factors that strengthened or hindered the integration of CARITAS. Notably, the presence of inspiring clinical leaders, having quick access to and close guidance from the tertiary hospital increased community partners’ knowledge, skills and confidence in care delivery. The closely knit interdisciplinary and cross-institutional partnership also facilitated the common goal of person-centred care for the patient–caregiver dyad. However, less than optimal inter-organisational stakeholder engagement, lack of structured process documentation and shared IT platform compromised the degree of integration.

The determinants of care integration within CARITAS are consistent with published literature. Salutary scores across professional, clinical and organisational integration could be attributed to knowledgeable and inspiring clinical leaders, regular face-to-face meetings and a comprehensive range of services for PWD and caregivers. These factors have been shown to facilitate the development of integrated care and its components.30–32 Competent leadership in the sharing of clinical expertise, providing guidance on patient care and establishing a culture that facilitates accountability and shared decision-making4 33–35 contributed to the readiness and commitment of team members to implement changes towards integrated care.35 Working across healthcare disciplines has been shown to enable shared decision-making and formation of care plans for patients with complex needs,34 35 contributing to improved clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction.19 Furthermore, having a comprehensive range of services afforded for both customisation and generalisation of care to meet varied needs.

A few factors unique to CARITAS impeded its endeavour of seamless care. The primary care team operated rather independently from the rest of the partners which compromised care continuity and information flow. Also, the absence of a common IT documentation and care planning platform,4 20 hindered information exchange between care providers. Information sharing is important to integrated care programmes without which less expedient ways of communication are inevitable.35

Integrated care programmes evolve with time and some dimensions mature more quickly than others.36 Integration often begins at micro-levels (eg, clinical integration) and meso-levels (eg, professional and organisational integration) before progressing to a macro-level (eg, system integration).37 Dimensions such as functional and normative integration which establish connectivity across the micro, meso and macro require significant time to stabilise.38 Moreover, integration may start from the primary organisation spearheading the initiative first before becoming established in other member agencies. It is thus conceivable that CARITAS performed better in dimensions such as clinical integration while the areas of functional and normative integration are still a work in progress.

There are ways to enhance the more mature dimensions of integration of CARITAS and augment the less developed ones. Addressing existing service gaps can refine the CARITAS model. First, extending telephone helpline beyond office hours can improve responsiveness to needs. Second, wider and deeper engagement to better understand caregiver needs will help develop targeted caregiver-support services. Third, to improve functional integration, the network can adopt a centralised IT infrastructure for documentation, communication and case coordination, all of which help standardise care delivery.38 Fourth, the network could organise formal and informal processes and activities to facilitate cross-organisational understanding and collaboration. They can serve to reiterate the objectives of the team, communicate key performance indicators, discuss strategies and align goals. These efforts can have positive effects on system and normative integration which are often harder to achieve. Finally, initiatives to engage users, increase visibility and scale up the initiative should be prioritised. CARITAS can take advantage of its strong leadership to connect with more organisations and continuously engage community stakeholders to garner longer-term support.

The strengths of this evaluation include the use of mixed-methods—drawing on both quantitative and qualitative methods to generate insights. Analyses by three coders also minimised the bias of qualitative research. However, certain limitations should be considered. Sampling of interview participants was conducted through the recommendations of a managerial staff and could have skewed the selection. To mitigate bias, participants were reminded that their responses would be anonymised, and efforts were made to capture the opinions of participants from each component of CARITAS. Additionally, 48% of the participants did not complete the RMIC Questionnaire which may limit the representativeness of the responses. This could be attributed to the length of the questionnaire (62 items), which took respondents 48 min on average to complete, whereas respondents who did not complete averaged only 4 min on the questionnaire. It is likely that staff turnover had resulted in several new staff with <1 year of CARITAS experience who felt inadequate to provide valid responses. Still, despite the reduced sample, the interviews largely validated the RMIC responses.

Conclusion

The findings reveal that integration in CARITAS has attained maturity on micro-levels (clinical integration) and meso-levels (professional and organisational integration), with potential for improvement on the macro-level (functional, system and normative integration).

Future studies could extend the RMIC to patient–caregiver dyads. This will help provide more holistic assessments which can lend valuable insights to assist programme planners, implementers, funders and policy makers in the conceptualisation, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of integrated care initiatives for patients with complex needs. Lastly, evaluation results of the clinical outcome and experience of CARITAS’ service users will be reported in another publication.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: NHLH and IC collected, analysed, interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. PY initiated the study, provided suggestions on the study methodology, helped interpret the findings and revised the manuscript. MN and HJMV conceptualised the study, provided guidance for data collection, analysis and suggestions to enhance the manuscript. SON contributed to data interpretation and revised the manuscript. S-LW conceptualised the study, supervised data collection, analysis and interpretation of result, and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received support from GERI Intramural Funding, project reference GERI/1610, cost number REPFPM006.

Competing interests: PY is a key clinical leader of the CARITAS integrated dementia care network.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Domain Specific Review Board, National Healthcare Group (Singapore) gave study ethics approval [Ref. 2017/00904].

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available. Dataset of the study is not available to protect the identities of the study participants.

References

- 1.Gröne O, Garcia-Barbero M, WHO European Office for Integrated Health Care Services . Integrated care: a position paper of the who European office for integrated health care services. Int J Integr Care 2001;1:e21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armitage GD, Suter E, Oelke ND, et al. Health systems integration: state of the evidence. Int J Integr Care 2009;9:e82. 10.5334/ijic.316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kodner DL. All together now: a conceptual exploration of integrated care. Healthc Q 2009;13 Spec No:6–15. 10.12927/hcq.2009.21091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suter E, Oelke ND, Adair CE, et al. Ten key principles for successful health systems integration. Healthc Q 2009;13 Spec No:16–23. 10.12927/hcq.2009.21092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Starfield B. Is patient-centered care the same as person-focused care? Perm J 2011;15:63–9. 10.7812/TPP/10-148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization Integrated health services – what and why? Tech Br, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008;337:a1655. 10.1136/bmj.a1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kane RL, Homyak P, Bershadsky B, et al. The effects of a variant of the program for all-inclusive care of the elderly on hospital utilization and outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006;54:276–83. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00581.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kane RL, Homyak P, Bershadsky B, et al. Consumer responses to the Wisconsin partnership program for elderly persons: a variation on the PACE model. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2002;57:M250–8. 10.1093/gerona/57.4.M250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown L, Tucker C, Domokos T. Evaluating the impact of integrated health and social care teams on older people living in the community. Health Soc Care Community 2003;11:85–94. 10.1046/j.1365-2524.2003.00409.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Busetto L, Luijkx K, Vrijhoef B. Development of the COMIC model for the comprehensive evaluation of integrated care interventions. Int J Integr Care 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kodner DL, Spreeuwenberg C. Integrated care: meaning, logic, applications, and implications--a discussion paper. Int J Integr Care 2002;2:e12. 10.5334/ijic.67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nolte E, McKee M. Integration and chronic care: a review In: Caring for people with chronic conditions: a health system perspective, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Viktoria Stein K, Rieder A. Integrated care at the crossroads-defining the way forward. Int J Integr Care 2009;9:e10. 10.5334/ijic.315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valentijn PP, Boesveld IC, van der Klauw DM, et al. Towards a taxonomy for integrated care: a mixed-methods study. Int J Integr Care 2015;15:e003. 10.5334/ijic.1513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valentijn PP, Schepman SM, Opheij W, et al. Understanding integrated care: a comprehensive conceptual framework based on the integrative functions of primary care. Int J Integr Care 2013;13:e010. 10.5334/ijic.886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valentijn PP, Vrijhoef HJM, Ruwaard D, et al. Towards an international taxonomy of integrated primary care: a Delphi consensus approach. BMC Fam Pract 2015;16:64. 10.1186/s12875-015-0278-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nurjono M, Valentijn PP, Bautista MAC, et al. A prospective validation study of a rainbow model of integrated care measurement tool in Singapore. Int J Integr Care 2016;16:1. 10.5334/ijic.2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xyrichis A, Lowton K. What fosters or prevents interprofessional teamworking in primary and community care? A literature review. Int J Nurs Stud 2008;45:140–53. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hartgerink JM, Cramm JM, van Wijngaarden JDH, et al. A framework for understanding outcomes of integrated care programs for the hospitalised elderly. Int J Integr Care 2013;13:e047. 10.5334/ijic.1063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johri M, Beland F, Bergman H. International experiments in integrated care for the elderly: a synthesis of the evidence. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003;18:222–35. 10.1002/gps.819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Orgainzation Framework on integrated, people-centred health services. Sisty-ninth World Health Assembly, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ogrinc G, Davies L, Goodman D, et al. Squire 2.0 (standards for quality improvement reporting excellence): revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process. BMJ Qual Saf 2016;25:986–92. 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alexandra Health System Annual Report 2014/2015 - Growing in the North with you, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 25.WHO, WPA . Organization of care in psychiatry of the elderly - a technical consensus statement. Aging Ment Health 1998;2:246–52. 10.1080/13607869856731 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.WHO Integrated care models: an overview. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flick U. An introduction to qualitative research. 5th ed London: Sage Publication Ltd, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tongco MDC. Purposive sampling as a tool for informant selection. Ethnobot Res Appl 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bunn F, Goodman C, Manthorpe J, et al. Supporting shared decision-making for older people with multiple health and social care needs: a protocol for a realist synthesis to inform integrated care models. BMJ Open 2017;7:e014026. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kastner M, Hayden L, Wong G, et al. Underlying mechanisms of complex interventions addressing the care of older adults with multimorbidity: a realist review. BMJ Open 2019;9:e025009. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nurjono M, Shrestha P, Ang IYH, et al. Implementation fidelity of a strategy to integrate service delivery: learnings from a transitional care program for individuals with complex needs in Singapore. BMC Health Serv Res 2019;19:177. 10.1186/s12913-019-3980-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pavlickova A, Henderson D, Alexandru CA, et al. The maturity of integrated care systems: lessons learned in using the SCIROCCO tool across Europe. Eur J Public Health 2017;28. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aarons GA, Sawitzky AC. Organizational culture and climate and mental health provider attitudes toward evidence-based practice. Psychol Serv 2006;3:61–72. 10.1037/1541-1559.3.1.61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glisson C, James LR. The cross-level effects of culture and climate in human service teams. J Organ Behav 2002;23:767–94. 10.1002/job.162 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weiner BJ. A theory of organizational readiness for change. Implement Sci 2009;4:67. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grooten L, Vrijhoef HJM, Calciolari S, et al. Assessing the maturity of the healthcare system for integrated care: testing measurement properties of the SCIROCCO tool. BMC Med Res Methodol 2019;19:63. 10.1186/s12874-019-0704-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Douglas HE, Georgiou A, Tariq A, et al. Implementing information and communication technology to support community aged care service integration: lessons from an Australian aged care provider. Int J Integr Care 2017;17:9. 10.5334/ijic.2437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grooten L, Borgermans L, Vrijhoef HJ. An instrument to measure maturity of integrated care: a first validation study. Int J Integr Care 2018;18:10. 10.5334/ijic.3063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-039017supp001.pdf (116.2KB, pdf)