Abstract

Introduction

Cancer burdens not only the patient but also the partner to a comparable extent. Partners of patients with cancer are highly involved in the caring process and therefore often experience distress and report a low quality of life. Interventions for supporting partners are scarce. Existing ones are rarely used by partners because they are often time-consuming per se and offer only limited flexibility with regard to schedule and location. The online intervention PartnerCARE has been developed on the basis of caregiver needs and consists of six consecutive sessions and four optional sessions, which are all guided by an e-coach. The study aims to evaluate feasibility and acceptance of the online intervention PartnerCARE and the related trial process. In addition, first insights of the putative efficacy of PartnerCARE should be gained.

Methods and analysis

A two-arm parallel-group randomised controlled trial will be conducted to compare the PartnerCARE online intervention with a waitlist control group. The study aims to recruit in total n=60 partners of patients with any type of cancer across different access paths (eg, university medical centres, support groups, social media). Congruent with feasibility study objectives, the primary outcome comprises recruitment process, study procedure, acceptance and satisfaction with the intervention (Client Satisfaction Questionnaire adapted to Internet-based interventions), possible negative effects (Inventory of Negative Effects in Psychotherapy) and dropout rates. Secondary outcomes include quality of life, distress, depression, anxiety, caregiver burden, fear of progression, social support, self-efficacy, coping and loneliness. Online measurements will be performed by self-assessment at three time points (baseline/pre-randomisation, 2 months and 4 months after randomisation). Data analyses will be based on intention-to-treat principle.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval has been granted by the Ethics Committee of the University of Ulm (No 390/18). Results from this study will be disseminated to relevant healthcare communities, in peer-reviewed journals and at scientific and clinical conferences.

Trial registration number

DRKS00017019.

Keywords: mental health, oncology, adult oncology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Randomised controlled feasibility trial of a novel online intervention specifically tailored to the care needs of partners of patients with cancer.

The PartnerCARE online intervention comprises evidence-based psychological support including psychoeducational, cognitive behavioural and guided imagery components.

Low-threshold intervention for partners with low utilisation of psychosocial services due to time and logistic limitations, low self-awareness of own care needs as well as gender-related concerns (eg, male partners).

Possible adverse effects of the intervention will be monitored.

Challenges of the trial comprise the diverse target group (regarding, eg, age, diagnosis of the patient, progress of the disease) and technical comprehension of the participants.

Introduction

Family members, particularly partners, are increasingly involved in the care of individuals with cancer.1 They support the patient in daily life (eg, they manage treatment appointments, take over additional tasks in the household, manage medication and provide emotional support) and are often not aware of their own needs.2 3 The disease and the corresponding challenging situation can lead to a great impact on the partner’s well-being and health. Partners are at high risk to suffer from various types of problems including social and emotional problems.4 Hence, caregivers of patients with cancer reported significantly more impairments than non-caregivers regarding work productivity, activity and quality of life.5 Whereas the physical quality of life of caring partners is similar to a norm population, their reported mental quality of life is significantly lower.6 Compared with non-caregivers, caregivers show a significantly higher occurrence of stress-related comorbidities like depression (odds ratio (OR)=1.50), anxiety (OR=1.97) or insomnia (OR=2.01),5 and compared with patients they show a similar prevalence of depression (pooled relative risk (RR)=1.01) and anxiety (RR=0.71).7 8 Concurrently, caregivers’ burden often stays invisible, due to the fact that the healthcare system focuses on the patient, which leaves partners’ supportive care needs often neglected or under-reported.9 Male partners as caregivers are a particularly under-recognised and undersupported group.10

Several psychosocial interventions have been designed to address the needs of cancer caregiver. The interventions differ regarding aim (eg, reduce caregiver burden, improve quality of life), underlying approaches (eg, psychoeducation, cognitive behavioural therapy, existential therapy), delivering format (eg, face-to-face, online, telephone and group therapy, dyadic, individual) and addressed participants (eg, couple, caregiver alone). Systematic reviews have shown that these interventions have small to medium positive effects on multiple outcomes for caregivers.11–13 Interventions exclusively relying on cognitive behavioural therapy had only negligible effects on caregivers.14 Especially in couple interventions, the effects for caregivers have to be considered critically because numerous interventions focus on patient care and include caregivers only as support resource.11 In general, intervention studies often lack reporting how to implement the interventions into practice.15 There are two main challenges about interventions for caregivers: first, the target group is difficult to reach, which is evident from low recruitment rates.12 16 Second, the existing face-to-face interventions are rarely used by caregivers (eg, they are too time-consuming, caregivers are unaware of own needs).17 18 As a result, online interventions have moved into focus over the last decade. They have broadly been perceived as suitable, acceptable and helpful for cancer caregivers.16 17 19 Online interventions have several advantages over other treatment delivering formats: online interventions are easily and quickly accessible as well as flexible regarding time and location independency, and they allow caregivers privacy while seeking for information and support.20 21 Furthermore, nearly a half of the caring partners are interested in using online interventions and would prefer an intervention that takes less than 1 hour per week, lasts minimum 5 weeks, is addressed to the partner only and contains information as well as peer support.22 23

In the context of the German National Cancer Plan, the Federal Ministry of Health requests appropriate psycho-oncological care for all patients and caregivers in need,24 25 irrespective of inpatient or outpatient treatment. A recent report on the psycho-oncological care in Germany recommends to develop and promote innovative offers like ehealth programmes.26 Despite the structures and recommendations, a lot of patients and caregivers receive no or no promptly and no low-threshold psycho-oncological care in Germany.27

Already developed or planned online interventions for caregivers address couples,28 29 informal caregivers in general (including partners, children, parents)30 31 or male caregivers and caregivers of patients with a specific type of cancer,32 33 while only one hitherto known intervention particularly addresses partners.34 None of them is available in German. The results from online interventions for caregivers are rare because to date most of them did only publish study protocols33 34 or promising trend results from feasibility studies.28–32

Aim

The present study has two aims. First, feasibility of the online intervention PartnerCARE and the extent of participants’ satisfaction with the intervention will be evaluated. Second, the potential efficacy of PartnerCARE on the partner’s well-being will be investigated compared with the waitlist control group post-treatment and over 4-month follow-up. The results of this feasibility study will be used to optimise PartnerCARE via participant feedback. Subsequently, a comprehensive efficacy evaluation of the online intervention is planned.

Methods

Study design

This is a two-arm, parallel randomised controlled trial (RCT) comparing the online intervention PartnerCARE (intervention group, IG) with a waitlist control group (CG). Participants of the IG will receive the guided version (with individual feedback from an e-coach) of PartnerCARE. The CG will receive no intervention during the study. After a waiting period of 4 months, participants of the CG will get the opportunity to work on the unguided version (with automatic feedback) of PartnerCARE. Assessments of the primary and secondary outcomes will take place at baseline (T0), 2 months after randomisation (post-treatment, T1) and 4 months after randomisation (follow-up, T2).

This clinical trial will be conducted and reported in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) Statement for pilot RCTs35 as well as the guidelines for executing and reporting internet intervention research.36 The study protocol is reported according to the SPIRIT (Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials) 2013 Statement.37 This study is registered in the German clinical trial register.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The primary inclusion criterion for participation is to be in a relationship with a partner who is diagnosed with any type of cancer (initial diagnosis or relapse, regardless of the onset of the disease or stage of the patient’s treatment). Participants are required (1) to be age 18 years or above, (2) have an internet access and an appropriate device, (3) provide the study team an email address for contact reasons and (4) sign an informed consent. Participants do not have to live with the patient, but participants will be excluded if the partner with cancer has died before the start of the study. Inclusion and exclusion criteria will be checked at the first online assessment (T0) via self-report.

Recruitment

To overcome the challenge of recruiting cancer caregivers, recruitment takes place in a multiplicity of online and offline fields in the complete German-speaking area (includes Germany, Austria and Switzerland). Participants are recruited in relevant social media groups (eg, groups for caregivers of patients with cancer), in online communities, via flyers and circular emails in university medical centres, links on clinic homepages, online and offline support groups, cancer counselling centres and comprehensive cancer centres. All recruitment routes lead to the PartnerCARE study homepage (www.esano.klips-ulm.de/de/trainings/krebserkrankung/partnercare/), where potential participants get information and can register for the study via contact form or sending an email to the study team. Recruitment started in April 2019 and is still ongoing until the target sample size will be reached. Due to further project plans and financial reasons, recruitment will be closed after 18 months, even if the target sample size could not be reached.

Study procedure

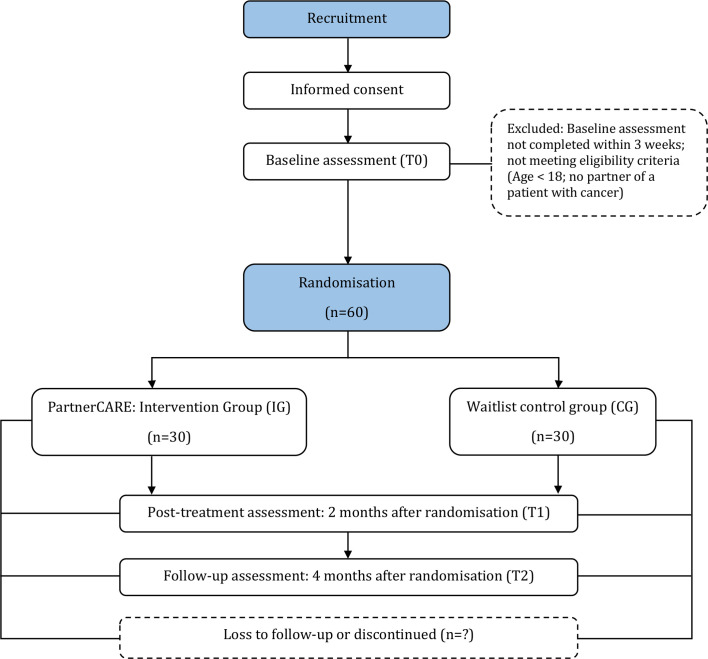

After initial contact via study homepage or email, interested partners will receive an email from the study team including a document with detailed participation information and an informed consent form attached. After given informed consent (via email, fax or mail), participants will get an invitation to the online baseline assessment (T0) and will be randomised afterwards either to the IG (immediate access to the guided version of PartnerCARE) or to the waitlist CG (access to the unguided version of PartnerCARE after about 4 months according to the follow-up assessment). Participants will be informed via email about group affiliation. Two months and 4 months after randomisation, all participants will receive an invitation for post-treatment and follow-up assessment (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study procedure.

Randomisation

Randomisation and allocation of participants to two groups will be conducted by an independent researcher, who is not involved in other processes of the study, using an automated online randomisation programme (www.sealedenvelope.com). Permuted block randomisation with randomly arranged block sizes (2 and 4) with an allocation ratio of 1:1 (allocation to IG and CG will be equally distributed in each block) will be performed. This results in a preferably balanced group distribution and that the data collector is not able to forecast the allocation of participant.

Intervention

Development of the intervention

The development of PartnerCARE was inspired by a therapy manual for a structured group intervention about psychoeducation with patients with cancer38 and internet intervention standards established by the research group (eg, Lin et al39). Thus, the intervention is based on various concepts that are widely used in cancer context: psychoeducation, behavioural therapy, supportive therapy and guided imagery.12 The group intervention was adapted to an individually online format and to the specific needs of caregivers. A literature search was conducted, focusing on current reviews, qualitative and quantitative research about needs of cancer caregivers.8 21 23 40–42 An overview of caregiver needs is listed in table 1. The most relevant topics out of the caregiver needs are included into the PartnerCARE intervention, and some topics that may only be relevant to some are provided as optional additional sessions (eg, sexuality, death and dying). As PartnerCARE is an offer to partners of patients with any kind of cancer, we abstained from putting detailed information about specific cancer disease and treatment into the intervention to avoid an overload of the single sessions. Instead, a list of relevant websites with further information and help services is provided in the sixth session.

Table 1.

Overview of needs of cancer caregivers

| Needs of caregivers | Literature | |

| Information | About illness and treatment, how to provide care | 8 23 40 41 |

| Comprehensive cancer care | Contact with healthcare professionals, knowledge of available services like, for example, peer support | 8 21 23 40 41 |

| Emotional and psychological support | Sleep disturbances, depression, anxiety, fatigue, weight gain | 8 23 40 42 |

| Impact in daily life | Financial, uncertainty, looking after own health, balance own needs with needs of patient | 8 21 23 40–42 |

| Relationship | Communication, sexuality | 8 23 40 |

| Spirituality | 40 42 | |

In order to ensure participant motivation, several persuasive elements were integrated in the design of PartnerCARE.43–45 The reduction principle is used by providing a weekly activity plan where participants record small activities for each day to learn in small and simple steps to improve self-care. At the beginning of each session, experience with the activities is queried (rehearsal principle). The tunnelling principle is implemented by guiding the participants through the intervention with feedback after each session from the e-coach. Reminders are sent if the weekly session exceeded 2 days. Three exemplary partners are specifically developed regarding the similarity and social learning principle by telling their story, giving exemplary answers on exercises and accompanying the participants through the sessions. These exemplary partners are introducing themselves in the first session via picture and written text. In all following sessions, participants can click on the picture of the exemplary partners and read their exemplary answers to various exercises. The exemplary partners are provided to show participants that they are not alone with their burdens. The online intervention is offered through Minddistrict (www.minddistrict.com), an ehealth platform where a secure access to the online intervention and a secure exchange between participant and e-coach are granted. The internet platform and the intervention are available 24 hours a day and 7 days a week.

The first version of PartnerCARE (main sessions) was evaluated by four independent psycho-oncologists (three psychologists, one psychiatrist) who were not involved in the development process. Each psycho-oncologist valued one session via the think aloud method46: while they were working on the session, they were encouraged to vocalise what they are thinking at the moment. Participant comments were collected on a list and used to further develop PartnerCARE regarding user-friendliness (eg, insert of progress bars on each page), text formulations (eg, incomprehensible and too psychological phrases verbalised more generally understandable) and content adjustments (eg, connections to previous sessions). The overall development process lasted from January 2018 until February 2019.

Content of the intervention

The content of the online intervention PartnerCARE (table 2) is composed of different empirically evaluated and clinically established manuals (eg, Weis et al38, Geuenich47). In the intervention, we combined content of different reliable approaches, which are shown to be effective for caregivers (eg, Applebaum and Breitbart12): psycho-education, cognitive behavioural therapy, supportive therapy and guided imagery elements. Therefore, the intervention focuses on activating resources, positive activities, communication skills, improving self-care and self-help strategies to manage caregiver burdens. In addition to psychoeducative text, the intervention contains visual and audio materials to enhance understanding and readability as well as to increase adherence and efficacy.48 Practical exercises and the three exemplary partners make the intervention interactive. The guided imagery exercises facilitate awareness of inner soul processes and they are used for relaxation. To create a transfer of the learnt content and strategies into daily life, examples and exercises for home practice between the sessions are contained. PartnerCARE consists of one introduction session (overview of the intervention, introduction in technical handling of the intervention), six main consecutive sessions, four optional additional sessions with specific content and one booster session. The optional sessions are presented at the third main session and can be selected by the participant. Duration of each session varies from 30 to 60 min, but there is no time limit. Participants work on their own and can take breaks within a session whenever and how often they want. It is recommended to work on one session each week to have enough time between the sessions for practising. Therefore, at the end of each session participants are asked to set an appointment for working on the next session.

Table 2.

Structure and content of the PartnerCARE sessions

| Sessions | Content | Example exercise |

| Introduction |

|

Aim: train the ability to use the online intervention |

| ||

| Main sessions | ||

| 1. Specific burdens |

|

We ask the partner to write down their story and how they cope with it. Aim: awareness of burden and perception of how to deal with the burden using existing resources |

| ||

| 2. Inner drivers |

|

Partners identify their inner drivers via questionnaire and are asked to phrase self-permissions. Aim: recognising and downscaling of excessive expectations on the own person to facilitate daily life |

| ||

| 3. Partnership communication |

|

Partners are asked to write down their communication problems. Afterwards they should plan a conversation with implementing the learnt communication rules. Aim: improve open communication between partner and patient |

| ||

| 4. Handling negative feelings |

|

Partners are encouraged to try different mindfulness exercises. Aim: reduction of dysfunctional coping and regain of control |

| ||

| 5. Control and acceptance |

|

Partners are asked which actuality they want to accept because it is not controllable. Furthermore, they learn how to enjoy little things. Aim: awareness of dysfunctional control and awareness of little positive things in everyday life |

| ||

| 6. Paths and goals |

|

We ask the partner what was helpful and what they want to continue. Aim: motivation of the partner to be his own trainer |

| ||

| ||

| Booster session |

|

Partners are asked how they have fared in the past 2 weeks and which exercises they continued. Aim: reminder and consolidation of training content |

| Optional additional sessions | ||

| Support of own children |

|

Partners are asked to write down their experience with their children and they get conversation examples. Aim: support with communication with children |

| ||

| Healthy sleep |

|

Quiz about healthy sleep and sleeping problems. Aim: support with sleep problems |

| ||

| ||

| Closeness and sexuality |

|

Partners learn about other types of sexuality, for example, relaxation and closeness through massage exercises. Aim: removal of taboos regarding communication about sexuality and encouragement to try something new |

| ||

| Existential burdens |

|

Partners can write about their thoughts about the end of life and they are encouraged to write about the sense of the time together with their spouse. Aim: removal of taboos regarding thinking and talking about death |

| ||

To have a clear structure over the whole intervention, every session follows the same process:

Today’s feeling: rating on a burden thermometer from 0 (‘no burden’) to 10 (‘high burden’) and describing the current feeling.

Report of home practice from the last week.

Basic information: psychoeducation about the topic of the session.

Practical exercises: during the session or for practice between the sessions.

Preview of the main topic from the next session.

Guided imagery exercise: guided audio imagination of approximately 10 min with different topics.

Online intervention process and guidance

After baseline assessment (T0), participants of the IG will get immediate access to PartnerCARE. Therefore, they will receive an email with log in information for the Minddistrict platform. After log in, the participant can start directly with the introduction session. At the end of each session, the participant clicks on a send button and the e-coach receives a note that a session was finished. Afterwards, the e-coach logs in to Minddistrict, reads the filled in text fields from the participant and writes a feedback. The participant also receives a note via email when feedback on a session is available.

The feedbacks from the e-coach will be partly standardised and individualised dependent on entries from the participant, encouraging them to stay motivated working on the intervention. Since it is aimed that e-coaches need about 10 min in average for writing a feedback due to time efficiency, the actual feedback time is measured. Participants will receive the feedback within the next 2 weekdays after completing a session. Participants can also write a personal message to the e-coach via the Minddistrict platform if they have questions or technical problems. The communication between participant and e-coach will be asynchronous. Guidance in online intervention is used to increase efficacy, adherence and decrease dropout.49 50

Text message coach

Participants can choose in session 1 if they want to be supported additionally with two SMS per week during the intervention (at no charge for the participant). SMS will be sent via online platform MessageBird (www.messagebird.com). The text message coach is thematically matched with the intervention and accompanies each session with two messages and after the main sessions one message per week until the booster session (in total 15 SMS). The text messages include motivational quotes, mini-tasks and reminders of positive activities or exercises, for example, ‘Before you go to bed tonight, look back on your day. Remember: What beautiful moments have you experienced today?’ It has been shown that SMS support may have the effect to enhance the intervention effect.51

Control condition

Participants of the waitlist CG will receive no intervention during the study phase but they are free to use other treatment options in standard care. Four months after randomisation and after completing the follow-up questionnaire (T2), they will get access to the unguided version of PartnerCARE. The intervention is the same as in the IG and participants will have the possibility to choose the text message coach in session 1 as well. But instead of individualised feedback, they will receive a short automatic feedback after each session.

Sample size/power calculation

Since with this study the practicality and feasibility of PartnerCARE will be evaluated as the primary outcome, a formal sample size calculation is not required. A total sample size of n=60 (30 partners per arm) was chosen as a recommendation for pilot trials.52 Part of the feasibility study will be to explore the feasibility of recruitment and rating of the different recruitment strategies.

Assessments

All assessments will take place at the online survey platform Unipark (www.unipark.de). Table 3 shows all outcomes and time points. Sociodemographic variables include age, sex, marital status, nationality, education, occupational situation and number of children. In addition, clinical characteristics from the diseased partner will be assessed with single questions: cancer diagnosis, date of diagnosis, phase of the disease and current medical treatments. Participants will be reminded via email to complete surveys if they do not respond to invitation email.

Table 3.

Overview of the assessments

| Instruments | Aim | Time of measurement | ||

| T0 | T1 | T2 | ||

| Primary outcome—feasibility | ||||

| CSQ-I* | Participant satisfaction | ✔ | ✔ | |

| INEP-On/INEP-CG | Negative effects online interventions (IG)/participation in study (CG) | ✔ | ✔ | |

| APOI | Attitudes psychological interventions | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Dropout rate | Participant adherence | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Evaluation SMS Coach* | SMS Coach satisfaction | ✔ | ||

| Secondary outcome | ||||

| DT | Distress | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| PHQ-8 | Depression | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| GAD-7 | Anxiety | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| VR-12 | Quality of life | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| BSFC-s | Caregiver burden | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| PA-F-P-KF | Fear of progression | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| ESSI | Perceived emotional social support | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| OSS-3 | Received social support | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| SWE | General self-efficacy expectation | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Brief COPE | Coping | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Loneliness | Feeling lonely | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Other assessments | ||||

| Sociodemographics | Age, sex, occupation, children | ✔ | ||

| Clinical characteristics patient | Diagnosis, onset, disease phase, current treatment | ✔ | ||

| Psychotherapy (yes/no, how long) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

T0: baseline, T1: 2 months, T2: 4 months.

*Recorded in intervention group only.

APOI, Attitudes towards Psychological Online Interventions Questionnaire; Brief COPE, abbreviated version of the COPE (Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced) inventory; BSFC-s, short version of the Burden Scale for Family Caregivers; CSQ-I, Client Satisfaction Questionnaire adapted to Internet-based interventions; DT, Distress thermometer; ESSI, ENRICHD Social Support Instrument; GAD-7, Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7; INEP-On/INEP-CG, Inventory of Negative Effects in Psychotherapy—online/-control group; OSS-3, 3-item Oslo Social Support scale; PA-F-P-KF, Fear of progression questionnaire for partners; PHQ-8, Patient Health Questionnaire-8; SWE, General Self-efficacy Expectation scale; VR-12, Veterans RAND 12-item health survey.

Primary outcome

Primary outcome of this pilot RCT study is the feasibility of the PartnerCARE online intervention. To characterise the different aspects of feasibility, a variety of questionnaires will be used. The measurement of feasibility will be composed of satisfaction with the online intervention, possible negative effects, attitudes toward psychological online interventions, evaluation of the SMS Coach, individual feedback from participants, processing duration of the sessions (via feedback from participants), participant flow, dropout rates, duration of the intervention, effort from the e-coaches and technical difficulties.

User satisfaction with web-based health interventions will be measured with the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire adapted to Internet-based interventions (CSQ-I).53 Eight items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 (‘does not apply to me’) to 4 (‘does totally apply to me’), which leads to a sum score range from 8 to 32. The scale demonstrated good reliability and construct validity. The CSQ-I is being only submitted to the IG post-treatment and follow-up.

Possible negative effects of the online intervention will be assessed with an online adapted version of the Inventory for the Assessment of Negative Effects in Psychotherapy (INEP).54 The original 21 items were adapted at the online setting by modifying text (‘online intervention’ instead of ‘therapy’) and replacing items about the relationship between participant and therapist with items about the e-coach. The adjusted inventory consists of 8 items with a 7-step bipolar format (−3=‘definitely a negative effect’; 0=‘unchanged’; +3=‘definitely a positive effect’) and 14 items with a 4-step unipolar format (from 0=‘strongly disagree’ to 3=‘fully agree’). Additionally, the first 17 items record whether any negative effect is attributed on the online intervention or on other circumstances in life. For the last 5 items, there is an open question in what way the statement applies. The internal consistency for the original INEP was good (α=0.86). Participants of the IG will receive the online adapted version of the INEP (INEP-On) post-treatment and follow-up. In contrast, participants of the CG will receive an abridged and adjusted INEP version with 14 items (INEP-CG) about the participation in the study and whether any negative effect is attributed on the participation in the study or on other circumstances in life post-treatment and follow- up. Both questionnaires include the question ‘Since or during the online intervention/participation of the study I had suicidal thoughts/intentions for the first time’. Participants who score 1 (‘agree a little bit’) receive automatically an email with information about available healthcare services in case of emergency. They are advised to seek for help if the symptoms increase. Participants who score 2 or 3 (‘agree partly’ or ‘fully agree’) receive likewise the automatically emergency email and additionally a psychotherapist of the study management calls the participant to clarify if they distance themselves from suicidal ideation.

The attitude towards online interventions will be assessed with the Attitudes towards Psychological Online Interventions Questionnaire (APOI).55 The APOI consists of 16 five-step items (from 1=‘totally agree’ to 5=‘totally disagree’), which can be integrated into four subscales: Scepticism and Perception of Risks (SCE), Confidence in Effectiveness (CON), Technologisation Threat (TET) and Anonymity Benefits (ABE), with a theoretical range of 4 to 20 for each subscale. The total sum score ranges from 16 to 80, whereas higher scores imply a positive attitude towards online interventions. The medians of the scales can be used to classify the scores (56 for the total sum score, 9 for SCE, 16 for CON, 12 for TET and 12 for ABE). Cronbach’s alpha with α=0.77 shows an acceptable to good internal consistency. The APOI is given to all participants at all three measurement points.

The SMS Coach will be evaluated with three items at post-treatment from participants of the IG: ‘The SMS Coach was helpful’, ‘The content of the SMS was pleasant’ and ‘The SMS Coach was motivating’. The items are scored on a five-point scale from 1 (‘never’) to 5 (‘always’).

After each finished PartnerCARE session at the Minddistrict platform, the participants will have the possibility to give individual feedback to the session. First, they can rate the session from 1 (‘did not like at all’) to 10 (‘did like very much’). One question is about the scope of the session (‘too extensive’, ‘too short’, ‘just right’). Then four open questions ask about which exercise was most helpful, what was positive, what could be improved and how long it took to complete the session.

Participant flow and dropout rates will be recorded during the study period. Duration of the intervention for each participant, effort from the e-coach (needed time for written feedback and quantity of sent reminders) and technical difficulties are collected by the e-coach.

Secondary outcomes

The NCCN Distress Thermometer (DT) that has been developed by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) is a valid and reliable measure of psychological distress.56 57 It consists of a single item with a scale from 0 (‘no distress’) to 10 (‘extreme distress’), illustrated by a thermometer and a list of 36 potential problems, which can cause distress (rationed into five categories: practical problems, family problems, emotional problems, spiritual/religious concerns and physical problems; all rated with yes/no). A cut-off value of 5 or higher is recommended for a clinically significant level of distress.

The German version of the Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8) is a reliable and valid self-report tool for assessing current depression symptoms.58 Given that the online intervention is preventive and does not focus on depression or suicidality, the PHQ-8 will be used instead of the PHQ-9 to assess depressive symptoms as secondary outcome. In this case, the PHQ-8 is an acceptable alternative to the PHQ-9. The sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive value of the PHQ-8 are comparable with the PHQ-9.59 The questionnaire consisting of eight items asks about impairments of the last 2 weeks and the items are scored on a four-point Likert scale from 0 (‘not at all’) to 3 (‘nearly every day’) with a total range from 0 to 24. Higher values indicate increased severity of symptoms and a cut-off point of ≥10 is defined for current depression symptoms.58

The Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 Questionnaire (GAD-7) is a valid and efficient tool for assessing symptoms of a generalised anxiety disorder.60 The seven items are scored on a four-point Likert scale from 0 (‘not at all’) to 3 (‘nearly every day’), a total score from 0 to 21 is possible. Like for the PHQ-8, a cut-off point of ≥10 is recommended to screen for symptoms of a generalised anxiety disorder. The reported internal consistency in a German sample is Cronbach’s α=0.89.61

Quality of life will be assessed with the Veterans RAND 12-Item Health Survey (VR-12), an abbreviated version of the Veterans RAND 36-Item Health Survey (VR-36), which was developed on the basis of the validated SF-36 (Short form 36 health survey) questionnaire.62 63 The VR-12 consists of different scaled questions (three-point scale, five-point scale and six-point scale) with different rating descriptions. The 12 items can be separated into two scores: physical and mental health. Standard norms of the summary scores are available for the US population: Mean for physical health summary is M=48.60 (SD=11.1) and for mental health summary M=51.01 (SD=10.0).64

The Short Version of the Burden Scale for Family Caregivers (BSFC-s) will be used to assess the amount of burden in caregivers.65 66 The 10 items are rated on a scale from 0 (‘strongly disagree’) to 3 (‘strongly agree’). The score can range from 0 to 30, where higher scores indicate greater caregiver burden. For interpreting the BSFC-s scores, a classification system was developed: 0–4 means ‘none to low’ burden, 5–14 means ‘moderate’ burden and 15–30 means ‘severe to very severe’ burden.66 Cronbach’s alpha for the complete scale with α=0.92 is very high.65

Fear of progression in spouse caregivers will be assessed with the German version of the questionnaire Fear of Progression in Partners of Chronically Ill Patients (FoP-Q-SF/P; German: PA-F-P-KF).67 The 12 items are responded on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (‘not at all’) to 5 (‘very much’). The scale will be evaluated through addition of the items, whereupon higher values show higher fear of progression. A cut-off with 34 or higher indicates dysfunctional fear of progression. The internal consistency of the complete scale is high (Cronbach’s α=0.87).

The ENRICHED Social Support Inventory (ESSI) is a short questionnaire to assess the perceived emotional social support.68 69 The five items are measured with a five-point scale (1=‘at no time’ to 5=‘always’) with a minimum of 5 and a maximum of 25. The internal consistency of the scale is α=0.89. Lack of social support is defined by values below 18.

Received social support will be assessed with the three-item Oslo Social Support scale (OSS-3).70 The questionnaire consists of one question with a four-point scale and two questions with a five-point scale with different descriptions. The evaluation is based on the sum score of the raw scores (3 to 14). A score of 3–8 can be interpreted as ‘poor support’, 9–11 as ‘moderate support’ and 12–14 as ‘strong support’, respectively. The internal consistency with α=0.64 is acceptable considering the number of items.71 While loneliness can be an important challenge for caregivers,72 we added one question about loneliness to this questionnaire: ‘How lonely do you feel at the moment?’ with a five-point scale from 1 (‘not at all’) to 5 (‘very much’).

The German version of the Generalised Self-Efficacy scale (GSE, German: SWE) measures the perceived self-efficacy.73 This one-dimensional scale was primarily developed for students and teachers but it is also used in cancer context.74 75 The 10 items have a response range from 1 (‘not at all true’) to 4 (‘exactly true’). The internal consistency is α=0.86 and the validity is confirmed by numerous findings.76

Coping will be assessed with the German version of the BriefCOPE (Brief Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced) Inventory.77 78 It consists of 28 items that are rated on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (‘not at all’) to 4 (‘very much’). The questionnaire is divided into 14 subscales, each represented by two items. The internal consistency for the subscales ranges from α=0.50 to α=0.90.

Patient and public involvement

Before start of the feasibility trial, psycho-oncologists and partners of patients with cancer were invited to value the main sessions of PartnerCARE. Since only four psycho-oncologists responded to the request, only the feedback from these four psycho-oncologists could be included in the development process. As a subsequent step, feedback from participants of the feasibility study will be used to further optimise the online intervention for the following efficacy evaluation study. We intend to disseminate the main results of the feasibility study with a short report at suitable platforms where partners of patients with cancer are reached (eg, online communities).

Statistical analysis

Demographic data will be reported using descriptive statistics. A chart of participant flow during the whole study will be plotted. Quantity of dropout and reasons for dropout will be displayed. With basic psychometric analyses, the scale structure and internal consistency of the used questionnaires will be verified. χ2 (for categorical variables) and t-tests will be performed to analyse whether randomisation leads to comparable groups with no significant differences at baseline. Before starting with the analyses, we will examine if the data is normally distributed, else we will use a non-parametric test. The significance level for all analyses will be p≤0.05.

All statistical analyses will be performed based on the intention-to-treat principle with multiple imputations to replace missing data. Per-protocol analyses for completers will be additionally conducted to investigate the influence of intervention attrition on study results.

Qualitative individual feedback from participants via the Minddistrict platform regarding the feasibility and acceptance of the online intervention will be summarised. Feasibility measurements from the online questionnaire will be analysed descriptive (INEP-On; dropout) and with t-test (APOI; CSQ-I (only in IG)).

To test a potential intervention effect, that is, an indication for the potential efficacy of PartnerCARE, continuous outcome parameters at post-treatment (T1) will be analysed using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), controlling for the baseline measurement (T0) and further covariates (eg, age, sex). For follow-up (T2) effects, a repeated measure ANCOVA will be conducted with time as within-subject factor (baseline vs post-treatment vs follow-up) and group as between-subject factor (IG vs CG). In case of a significant main effect, post hoc tests will be conducted to analyse between which measurement points the significant differences exist. Cohen’s d will be calculated to report effect sizes (effect sizes smaller than 0.32 are considered small, 0.33–0.55 are considered moderate and those larger than 0.56 are considered large79).

Discussion

Partners of patients with cancer are confronted with a variety of challenges and new, additional tasks regarding the disease, resulting in a decrease of mental health. These burdens are often overlooked and psycho-oncological support or specific interventions for partners are rare. The online intervention PartnerCARE was developed to provide tailored support for partners of patients with cancer. The main purpose of the feasibility study is to evaluate the feasibility and acceptance of PartnerCARE and of the study process itself through an RCT. Furthermore, we aim to gain first preliminary evidence for the potential efficacy of the online intervention that is hoped to pave the way for a comprehensive efficacy evaluation study. An online intervention is, from our point of view, particularly suitable for partners because of the flexibility (time and place independency), easy accessibility, possible anonymity and low-threshold format. We expect that the online intervention facilitates access to psychosocial services for partners with hitherto low utilisation of conventional face-to-face psychosocial care (eg, because of logistic and time reasons, discomfort or other objections towards psychosocial services or gender-related reasons).17 18 Although to date there is evidence that the majority of online intervention users are female17 and female caregivers are more negatively affected by the caregiving process,1 male caregivers should not be neglected. We assume that online interventions could suit particularly for male caregivers because of their tendency to have to be strong (no public searching for help) and their potential difficulties to express their concerns and emotions (could be easier for them in an online setting).10 There is recent research about an online intervention especially for male caregivers,33 but definitely more research is needed to investigate specific needs of male caregivers and how to better reach male participants for online interventions.

Recruitment of partners of patients with cancer can be challenging due to the fact that partners are often busy and therefore not reached at the clinic, recruitment via patient is not always effective (information is not passed to the partner) and there are not many typical areas where partners can be reached. Recruitment rates for caregivers of patients with cancer tended to be poor and varied from 20% to 66%.16 To overcome the challenges of recruitment, we try to use a wide variety of online and offline recruitment strategies and will evaluate their adequacy.

PartnerCARE is the first online intervention for partners of patients with cancer available in German language. The newly developed online intervention for partners of patients with cancer is adjusted to the needs of cancer caregivers and takes several persuasive principles into account. The online intervention uses a variety of different elements (relevant topics, varying exercises, practical tips, guided imagery exercises) to motivate participants to go on with the intervention. If the pilot study verifies feasibility and acceptance of PartnerCARE, it is conceivable to translate PartnerCARE in different languages and evaluate the online intervention in further studies worldwide.

With this pilot study, we will initiate a continuous development and evaluation process of the online intervention PartnerCARE. During the online intervention, we assess satisfaction, positive and negative estimations of the intervention via written feedback. These insights from partners of persons with cancer will be used to improve and further develop PartnerCARE to an even more user-tailored intervention. We will also assess possible negative effects in our RCT to evaluate potential side effects of the online intervention for partners. The measurement of e-coach time for feedback every week and quantity of sent reminders will give a first insight in the estimation of costs for the online intervention for implementation in usual healthcare.

A few limitations need to be taken into consideration. As all outcomes will be assessed via self-report and the contact with participants is only online, there is uncertainty regarding the identity of the participants. With signed informed consent and control questions with automatic premature termination at the first online assessment, this problem will be reduced. Online interventions in general and online interventions specifically for caregivers have to face with high dropout rates (29%–38%).80 81 To reduce a potential adherence problem and to enhance motivation, the participants of the IG will be accompanied by an e-coach with feedback and reminders50 82 and the development of the online design includes persuasive elements.45 As participation in the study is only possible with access to internet and some technical affinity, we designed the online intervention as simple and intuitive as possible and will offer technical use basics at the introduction session. Furthermore, it has been discussed that including a waitlist control condition leads to an overestimation of the effect sizes compared with a no treatment or psychological placebo condition.83 However, all participants in our study will be free to use care as usual and they receive a list of other treatment options like cancer counselling centres if they are interested. Furthermore, we will be able to have a look on possible long-term effects (4-month follow-up), but this leads to a long waiting time for the waitlist CG. In addition, our online intervention for partners could not cover all relevant topics: a recent study showed ‘home care interventions’, ‘impact of financial demands on caregiver, ‘impact of health reforms, programmes and policies on caregivers’ as some of the most important topics for caregivers.84 The further development of PartnerCARE should take these insights into account.

Regarding the future outlook, PartnerCARE could be included into the healthcare routine: by the time a patient becomes diagnosed with cancer, also the partner should be screened for psycho-social and physical burdens. PartnerCARE can also provide a communicative benefit for healthcare professionals with enhanced awareness of caregivers and the opportunity of having a special offer for partners. If needed, PartnerCARE could be immediately offered as a tool for partners to work on their burdens regardless of where and when. It can also be used to overcome the waiting time for partners until a local psycho-oncological treatment is available.

Ethics and dissemination

This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Ulm (No 390/18). Results will be published in peer-reviewed journals and presented on local, national and international conferences.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank Sabrina Heil for her engagement in enrolling participants and for her support in study organisation. Furthermore, authors thank Daniel Neveling for his support as e-coach and Miriam Stock for providing the imaginary exercise audio files. Authors also thank Eileen Bendig for her supporting role in planning the trial process, Ann-Marie Kuechler for her support at the Minddistrict Platform as well as Robin Kraft and Sebastian Broetzler for creating the PartnerCARE homepage. Special thanks go to the psycho oncologists who valued the PartnerCARE sessions and thus support the enhancement of the intervention.

Footnotes

Contributors: DB, NB, HG, HB and KH contributed to the study design. DB and IL compiled the content of the intervention sessions. The online design and structure of the intervention was carried out from DB building on prior online interventions of the Department of Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy (HB). Intervention development was supervised by NB, HG, HB and KH. DB is responsible for recruitment and coordination of the study. DB drafted the manuscript. All authors provided critical revision and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from the German Cancer Aid to the Comprehensive Cancer Center Ulm (grant number: 70112209). The German Cancer Aid had no role in study design, decision to publish or preparation of this manuscript. The German Cancer Aid will not be involved in data collection, analyses, decision to publish or preparation of future papers regarding the PartnerCARE project.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Li QP, Mak YW, Loke AY. Spouses’ experience of caregiving for cancer patients: a literature review. Int Nurs Rev 2013;60:178–87. 10.1111/inr.12000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Popek V, Hönig K. [Cancer and family: tasks and stress of relatives]. Nervenarzt 2015;86:266–8. 10.1007/s00115-014-4154-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pitceathly C, Maguire P. The psychological impact of cancer on patients’ partners and other key relatives: a review. Eur J Cancer 2003;39:1517–24. 10.1016/S0959-8049(03)00309-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stenberg U, Ruland CM, Miaskowski C. Review of the literature on the effects of caring for a patient with cancer. Psychooncology 2010;19:1013–25. 10.1002/pon.1670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goren A, Gilloteau I, Lees M, et al. Quantifying the burden of informal caregiving for patients with cancer in Europe. Support Care Cancer 2014;22:1637–46. 10.1007/s00520-014-2122-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergelt C, Koch U, Petersen C. Quality of life in partners of patients with cancer. Qual Life Res 2008;17:653–63. 10.1007/s11136-008-9349-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitchell AJ, Ferguson DW, Gill J, et al. Depression and anxiety in long-term cancer survivors compared with spouses and healthy controls: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:721–32. 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70244-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sklenarova H, Krümpelmann A, Haun MW, et al. When do we need to care about the caregiver? supportive care needs, anxiety, and depression among informal caregivers of patients with cancer and cancer survivors. Cancer 2015;121:1513–9. 10.1002/cncr.29223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenberger C, Höcker A, Cartus M, et al. [Outpatient psycho-oncological care for family members and patients: access, psychological distress and supportive care needs]. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol 2012;62:185–94. 10.1055/s-0032-1304994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopez V, Copp G, Molassiotis A. Male caregivers of patients with breast and gynecologic cancer. Cancer Nurs 2012;35:402–10. 10.1097/NCC.0b013e318231daf0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Northouse L, Katapodi M, Song L, et al. Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: meta-analysis of randomized trials. CA Cancer J Clin 2011;60:317–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Applebaum AJ, Breitbart W. Care for the cancer caregiver: a systematic review. Palliat Support Care 2013;11:231–52. 10.1017/S1478951512000594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kleine A-K, Hallensleben N, Mehnert A, et al. Psychological interventions targeting partners of cancer patients: a systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2019;140:52–66. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2019.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Toole MS, Zachariae R, Renna ME, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapies for informal caregivers of patients with cancer and cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychooncology 2017;26:428–37. 10.1002/pon.4144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ugalde A, Gaskin CJ, Rankin NM, et al. A systematic review of cancer caregiver interventions: appraising the potential for implementation of evidence into practice. Psychooncology 2019;28:687–701. 10.1002/pon.5018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heynsbergh N, Heckel L, Botti M, et al. Feasibility, useability and acceptability of technology-based interventions for informal cancer carers: a systematic review. BMC Cancer 2018;18:244. 10.1186/s12885-018-4160-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaltenbaugh DJ, Klem ML, Hu L, et al. Using web-based interventions to support caregivers of patients with cancer: a systematic review. Oncol Nurs Forum 2015;42:156–64. 10.1188/15.ONF.156-164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sinfield P, Baker R, Ali S, et al. The needs of carers of men with prostate cancer and barriers and enablers to meeting them: a qualitative study in England. Eur J Cancer Care 2012;21:527–34. 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2012.01341.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sin J, Henderson C, Spain D, et al. eHealth interventions for family carers of people with long term illness: a promising approach? Clin Psychol Rev 2018;60:109–25. 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Griffiths F, Lindenmeyer A, Powell J, et al. Why are health care interventions delivered over the Internet? A systematic review of the published literature. J Med Internet Res 2006;8:e10. 10.2196/jmir.8.2.e10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heynsbergh N, Botti M, Heckel L, et al. Caring for the person with cancer and the role of digital technology in supporting carers. Support Care Cancer 2019;27:2203–9. 10.1007/s00520-018-4503-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Köhle N, Drossaert CHC, Van Uden-Kraan CF, et al. Intent to use a web-based psychological intervention for partners of cancer patients: associated factors and preferences. J Psychosoc Oncol 2018;36:203–21. 10.1080/07347332.2017.1397831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Köhle N, Drossaert CH, Oosterik S, et al. Needs and preferences of partners of cancer patients regarding a web-based psychological intervention: a qualitative study. JMIR Cancer 2015;1:e13. 10.2196/cancer.4631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bundesministerium für Gesundheit Nationaler Krebsplan: Handlungsfelder, Ziele, Umsetzungsempfehlungen und Ergebnisse, 2017. Available: https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/fileadmin/Dateien/5_Publikationen/Praevention/Broschueren/Broschuere_Nationaler_Krebsplan.pdf [Accessed 5 Jun 2019].

- 25.Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, AWMF) Psychoonkologische Diagnostik, Beratung und Behandlung von erwachsenen Krebspatienten, Langversion 1.1, 2014. Available: https://www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Downloads/Leitlinien/Psychoonkologieleitlinie_1.1/LL_PSO_Langversion_1.1.pdf [Accessed 5 Jun 2019].

- 26.Schulz H, Bleich C, Bokemeyer C, et al. Psychoonkologische versorgung in deutschland : bundesweite bestandsaufnahme und analyse, 2018. Available: https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/fileadmin/Dateien/5_Publikationen/Gesundheit/Berichte/PsoViD_Gutachten_BMG_19_02_14_gender.pdf [Accessed 21 Jun 2019].

- 27.Mehnert A, Koranyi S. [Psychooncological care: a challenge]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 2018;143:316–23. 10.1055/s-0043-107631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Northouse L, Schafenacker A, Barr KLC, et al. A tailored web-based psychoeducational intervention for cancer patients and their family caregivers. Cancer Nurs 2014;37:1–30. 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song L, Rini C, Deal AM, et al. Improving couples’ quality of life through a web-based prostate cancer education intervention. Oncol Nurs Forum 2015;42:183–92. 10.1188/15.ONF.183-192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scott K, Beatty L. Feasibility study of a self-guided cognitive behaviour therapy Internet intervention for cancer carers. Aust J Prim Health 2013;19:270–4. 10.1071/PY13025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Applebaum AJ, Buda KL, Schofield E, et al. Exploring the cancer caregiver’s journey through web-based meaning-centered psychotherapy. Psychooncology 2018;27:847–56. 10.1002/pon.4583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duggleby W, Ghosh S, Struthers-Montford K, et al. Feasibility study of an online intervention to support male spouses of women with breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 2017;44:765–75. 10.1188/17.ONF.765-775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levesque JV, Gerges M, Girgis A. The development of an online intervention (care assist) to support male caregivers of women with breast cancer: a protocol for a mixed methods study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e019530. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Köhle N, Drossaert CHC, Schreurs KMG, et al. A web-based self-help intervention for partners of cancer patients based on acceptance and commitment therapy: a protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2015;15:303. 10.1186/s12889-015-1656-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eldridge SM, Chan CL, Campbell MJ, et al. Consort 2010 statement: extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. Pilot Feasibility Stud 2016;2:64–96. 10.1186/s40814-016-0105-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Proudfoot J, Klein B, Barak A, et al. Establishing guidelines for executing and reporting internet intervention research. Cogn Behav Ther 2011;40:82–97. 10.1080/16506073.2011.573807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. Spirit 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:200–7. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weis J, Heckl U, Brocai D, et al. Psychoedukation mit Krebspatienten - Therapiemanual für eine strukturierte Gruppenintervention. Stuttgart: Schattauer, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin J, Paganini S, Sander L, et al. An internet-based intervention for chronic pain. Dtsch Aerzteblatt Online 2017;114:681–8. 10.3238/arztebl.2017.0681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lambert SD, Harrison JD, Smith E, et al. The unmet needs of partners and caregivers of adults diagnosed with cancer: a systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2012;2:224–30. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marcotte J, Tremblay D, Turcotte A, et al. Needs-focused interventions for family caregivers of older adults with cancer: a descriptive interpretive study. Support Care Cancer 2019;27:2771–81. 10.1007/s00520-018-4573-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Skalla KA, Smith EML, Li Z, et al. Multidimensional needs of caregivers for patients with cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2013;17:500–6. 10.1188/13.CJON.17-05AP [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oinas-Kukkonen H, Harjumaa M. Persuasive systems design: key issues, process model, and system features. CAIS 2009;24:485–500. 10.17705/1CAIS.02428 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kelders SM, Kok RN, Ossebaard HC, et al. Persuasive system design does matter: a systematic review of adherence to web-based interventions. J Med Internet Res 2012;14:e152. 10.2196/jmir.2104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baumeister H, Kraft R, Baumel A, et al. Persuasive e-health design for behavior change : Digital phenotyping and mobile sensing: new developments in psychoinformatics. Berlin: Springer, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jaspers MWM, Steen T, van den Bos C, et al. The think aloud method: a guide to user interface design. Int J Med Inform 2004;73:781–95. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2004.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Geuenich K. Krebs gemeinsam bewältigen - Wie Angehörige durch Achtsamkeit Ressourcen stärken. Stuttgart: Schattauer, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Andersson G, Carlbring P, Berger T, et al. What makes internet therapy work? Cogn Behav Ther 2009;38:55–60. 10.1080/16506070902916400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mohr DC, Cuijpers P, Lehman K. Supportive accountability: a model for providing human support to enhance adherence to eHealth interventions. J Med Internet Res 2011;13:e30–11. 10.2196/jmir.1602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baumeister H, Reichler L, Munzinger M, et al. The impact of guidance on Internet-based mental health interventions—a systematic review. Internet Interv 2014;1:205–15. 10.1016/j.invent.2014.08.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eckert M, Ebert DD, Lehr D, et al. Does SMS-support make a difference? effectiveness of a two-week online-training to overcome procrastination. A randomized controlled trial. Front Psychol 2018;9:1–13. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Viechtbauer W, Smits L, Kotz D, et al. A simple formula for the calculation of sample size in pilot studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2015;68:1375–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Boß L, Lehr D, Reis D, et al. Reliability and validity of assessing user satisfaction with web-based health interventions. J Med Internet Res 2016;18:e234. 10.2196/jmir.5952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ladwig I, Rief W, Nestoriuc Y. What are the risks and side effects of psychotherapy? – development of an inventory for the assessment of negative effects of psychotherapy (INEP). Verhaltenstherapie 2014;24:252–63. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schröder J, Sautier L, Kriston L, et al. Development of a questionnaire measuring attitudes towards psychological online Interventions-the APOI. J Affect Disord 2015;187:136–41. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.08.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mehnert A, Müller D, Lehmann C, et al. Die Deutsche version des NCCN Distress-Thermometers: Empirische Prüfung eines Screening-Instruments Zur erfassung psychosozialer Belastung bei Krebspatienten. Zeitschrift fur Psychiatr Psychol und Psychother 2006;54:213–23. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roth AJ, Kornblith AB, Batel-Copel L, et al. Rapid screening for psychologic distress in men with prostate carcinoma: a pilot study. Cancer 1998;82:1904–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, et al. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord 2009;114:163–73. 10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr Ann 2002;32:509–15. 10.3928/0048-5713-20020901-06 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092–7. 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Löwe B, Decker O, Müller S, et al. Validation and standardization of the generalized anxiety disorder screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care 2008;46:266–74. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318160d093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Iqbal SU, Rogers W, Selim A, et al. The veterans RAND 12 item health survey (VR-12): what it is and how it is used In: CHQOERs Va Med center CapP Bost Univ SCH public heal Bedford, 2007: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kazis LE, Miller DR, Clark JA, et al. Improving the response choices on the Veterans SF-36 health survey role functioning scales: results from the Veterans health study. J Ambul Care Manage 2004;27:263–80. 10.1097/00004479-200407000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Selim AJ, Rogers W, Fleishman JA, et al. Updated U.S. population standard for the veterans rand 12-Item health survey (VR-12). Qual Life Res 2009;18:43–52. 10.1007/s11136-008-9418-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Graessel E, Berth H, Lichte T, et al. Subjective caregiver burden: validity of the 10-item short version of the burden scale for family caregivers BSFC-s. BMC Geriatr 2014;14:1–9. 10.1186/1471-2318-14-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pendergrass A, Malnis C, Graf U, et al. Screening for caregivers at risk: extended validation of the short version of the burden scale for family caregivers (BSFC-s) with a valid classification system for caregivers caring for an older person at home. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:1–9. 10.1186/s12913-018-3047-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zimmermann T, Herschbach P, Wessarges M, et al. Fear of progression in partners of chronically ill patients. Behav Med 2011;37:95–104. 10.1080/08964289.2011.605399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kendel F, Spaderna H, Sieverding M, et al. Eine Deutsche adaptation des ENRICHD social support inventory (ESSI). Diagnostica 2011;57:99–106. 10.1026/0012-1924/a000030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cordes A, Herrmann-Lingen C, Büchner B, et al. Repräsentative Normierung des ENRICHD-Social-Support-Instrument (ESSI) - Deutsche Version. Klin Diagnostik und Eval 2009;1:16–32. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dalgard OS, Dowrick C, Lehtinen V, et al. Negative life events, social support and gender difference in depression. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2006;41:444–51. 10.1007/s00127-006-0051-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kocalevent R-D, Berg L, Beutel ME, et al. Social support in the general population: standardization of the Oslo social support scale (OSSS-3). BMC Psychol 2018;6:4–11. 10.1186/s40359-018-0249-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vasileiou K, Barnett J, Barreto M, et al. Experiences of loneliness associated with being an informal caregiver: a qualitative investigation. Front Psychol 2017;8:585. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jerusalem M, Schwarzer R. Skalen Zur Erfassung von Lehrer- und Schülermerkmalen. Dokumentation Der psychometrischen Verfahren Im Rahmen Der Wissenschaftlichen Begleitung des Modellversuchs Selbstwirksame Schulen. Berlin: Freie Universität Berlin, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Luszczynska A, Scholz U, Schwarzer R. The general self-efficacy scale: multicultural validation studies. J Psychol 2005;139:439–57. 10.3200/JRLP.139.5.439-457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mystakidou K, Parpa E, Panagiotou I, et al. Caregivers’ anxiety and self-efficacy in palliative care. Eur J Cancer Care 2013;22:188–95. 10.1111/ecc.12012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Scholz U, Gutierrez-Dona B, Sud S, et al. Is general self-efficacy a universal construct ? Psychometric findings from 25 countries. Eur J Psychol Assess 2002;18:242–51. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: consider the brief cope. Int J Behav Med 1997;4:92–100. 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Knoll N, Rieckmann N, Schwarzer R. Coping as a mediator between personality and stress outcomes: a longitudinal study with cataract surgery patients. Eur J Pers 2005;19:229–47. 10.1002/per.546 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. The efficacy of psychological, educational, and behavioral treatment. confirmation from meta-analysis. Am Psychol 1993;48:1181–209. 10.1037/0003-066X.48.12.1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Melville KM, Casey LM, Kavanagh DJ. Dropout from internet-based treatment for psychological disorders. Br J Clin Psychol 2010;49:455–71. 10.1348/014466509X472138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tang WP, Chan CW, So WK, et al. Web-based interventions for caregivers of cancer patients: a review of literatures. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs 2014;1:9–15. 10.4103/2347-5625.135811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fry JP, Neff RA. Periodic prompts and reminders in health promotion and health behavior interventions: systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2009;11:e16–15. 10.2196/jmir.1138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Furukawa TA, Noma H, Caldwell DM, et al. Waiting list may be a nocebo condition in psychotherapy trials: a contribution from network meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2014;130:181–92. 10.1111/acps.12275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lambert SD, Ould Brahim L, Morrison M, et al. Priorities for caregiver research in cancer care: an international Delphi survey of caregivers, clinicians, managers, and researchers. Support Care Cancer 2019;27:805–17. 10.1007/s00520-018-4314-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.