Abstract

Background

Hypertension confers a poor prognosis in moderate or severe aortic stenosis (AS), however, antihypertensive therapy (AHT) is often not prescribed due to the perceived deleterious effects of vasodilation and negative inotropes.

Objective

To assess the efficacy and safety outcomes of AHT in adults with moderate or severe AS.

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE, EMBASE and grey literature were searched without language restrictions up to 9 September 2019.

Study eligibility criteria, appraisal and synthesis methods

Two independent reviewers performed screening, data extraction and risk of bias assessments from a systematic search of observational studies and randomised controlled trials comparing AHT with a placebo or no AHT in adults with moderate or severe AS for any parameter of efficacy and safety outcomes. Conflicts were resolved by the third reviewer. Meta-analysis with pooled effect sizes using random-effects model, were estimated in R.

Main outcome measures

Mortality, Left Ventricular (LV) Mass Index, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure and LV ejection fraction

Results

From 3025 publications, 31 studies (26 500 patients) were included in the qualitative synthesis and 24 studies in the meta-analysis. AHT was not associated with mortality when all studies were pooled, but heterogeneity was substantial across studies. The effect size of AHT differed according to drug class. Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors (RAASi) were associated with reduced risk of mortality (Pooled HR 0.58, 95% CI 0.43 to 0.80, p=0.006), The differences in changes of haemodynamic or echocardiographic parameters from baseline with and without AHT did not reach statistical significance.

Conclusion

AHT appears safe, is well tolerated. RAASi were associated with clinical benefit in patients with moderate or severe AS.

Keywords: valvular heart disease, hypertension, adult cardiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The most comprehensive review of evidence to date, summarising the results of observational studies and randomised controlled trials in all relevant databases, involving over 20 000 participants.

As there are few randomised trials, most publications derived from non-randomised observational studies, and there is a risk of selection, information and confounding bias.

Classification of moderate or severe aortic stenosis (AS) varied in different studies; some defined participants on the basis of undergoing aortic valve replacement.

For those studies that classified severity of AS by echo parameters, a wide range of thresholds were used, such as aortic valve area less than 0.75, 0.8, 1 or 1.2 cm2 or peak velocity above 2.5, 3, 4.5 or 5 m/s.

There was variability in antihypertensive therapy treatments and controls.

Introduction

Aortic stenosis (AS) is common and of increasing prevalence.1 AS is recognised as both a heart valve disease and a disease of the left ventricular (LV),2 because LV remodelling or LV hypertrophy (LVH) occur as an adaptive response to compensate for LV afterload and in order to normalise wall stress.3 4 Since LVH is associated with impaired coronary blood flow reserve, diastolic dysfunction and increased risk of heart failure and death,5–12 this may also be an important contributor to the symptoms and mortality associated with AS.5 6 13–18 However, pressure overload due to hypertension also may result in increased LV mass, mask pressure gradient and lead to low-gradient severe AS.19–21 Globally, the ageing population has led to an increased prevalence of hypertension, and the combination of AS and hypertension can accelerate need for aortic valve replacement (AVR).22–30 Consequently, LVH regression is a potential therapeutic target in AS.

Current guidelines recommend treating hypertension in AS,31 32 and inhibition of renin–angiotensin and aldosterone systems (RAAS) may have benefits on LV remodelling.33 Nonetheless, current drug monographs state that antihypertensive therapies (AHT) should be used with caution in patients with significant AS and are commonly not prescribed to patients with moderate or severe AS. The two most widely cited concerns are the dependence of coronary flow on aortic pressure in LVH, and the need to preserve LV preload to fill the hypertrophied LV and maintain cardiac output.34 Other potential concerns of AHT in AS include vasodilation, negative inotropes, hypotension, fall in filling pressure and syncope. In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we assessed the effects (clinical outcomes, haemodynamic and echocardiographic changes) of AHT in patients with moderate or severe AS from observational studies and randomised controlled trials (RCTs). We hypothesised that AHT can be used effectively and safely for treating hypertension in moderate or severe AS.

Methods

This systematic review was carried out in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Statement and Meta-analyses Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology Checklist.35 36

Search strategy

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (up to 9 September 2019), MEDLINE (1946 to 9 September 2019) and EMBASE (1947 to 9 September 2019) for RCTs and observational studies that assessed the use of any AHT in patients over 18 years old with moderate or severe AS. Common search terms included: (“aortic valve stenosis” or “aortic stenosis”) and (“antihypertensive agents” or “angiotensin converting enzyme antagonist” or “angiotensin receptor-2 blocker” or “diuretic” or other drug classes or other specific drug names). We also handsearched relevant cardiology journals, conference proceedings and clinical trials databases and reference lists of relevant articles, including reviews. Language, publication status and length of follow-up restrictions were not applied. The full MEDLINE search strategy and list of grey literature are contained within the online supplemental materials. EndNote (V.X9.3.2, Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, USA) was used to retrieve citations.

bmjopen-2020-036960supp001.pdf (455.8KB, pdf)

Study selection

Two reviewers (JS and EC) independently screened articles for inclusion based on the following criteria: adults (over 18 years old) with moderate or severe AS, treated with any AHT and assessed for any parameter of efficacy (eg, survival, reduction in blood pressure, improvement in LV function) and safety outcomes (eg, mortality, renal impairment). Studies were excluded did not describe AS severity grade, had a sample size less than six patients or if abstracts or unpublished studies were not methodological quality-assessable and critically appraisable. Bibliographies of review articles were analysed for additional articles but excluded for the purposes of the study. Systemic review management software (Covidence, Melbourne, Australia) was used to track papers. Conflicts were resolved by consensus with a third reviewer (TM).

Data extraction

Data extraction was done by two independent reviewers (JS and EC) using standard forms. Any disagreements and conflicts were resolved by a third reviewer (TM). The variables extracted are described in online supplemental materials. Post-treatment values and/or change from baseline (mean and SD, effect estimates and 95% CI or number and proportions) were recorded for the primary outcome, mortality, and secondary outcomes, LV mass index, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure and LV ejection fraction. Other outcomes extracted included post-AVR complications such as atrial fibrillation, stroke, need for permanent pacemaker, readmission or acute kidney disease and other haemodynamic or echocardiographic parameters such as mean atrial pressure, heart rate, aortic valve area, mean pressure gradient, deceleration time, E/A ratio and E/e’ ratio. The authors of included studies were contacted for clarification, when needed.

Risk of bias and quality assessments

Risk of bias assessments were conducted independently by two reviewers (JS and EC) using the Cochrane Collaboration tool for RCTs (which include judgement of bias from random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, assessments should be made for each main outcome, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data and selective reporting). Quality of non-randomised case–control and cohort studies were assessed using Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (which include assessment of patient selection, comparability and outcomes), while quality of uncontrolled observational studies was assessed based on National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Study Quality Assessment Tool for Before-After Studies with No Control Group.

Data syntheses and analyses

Dichotomous outcomes (alive vs dead at follow-up) were expressed as numbers, proportions and relative risks (RR), time-to-event outcomes (mortality) were expressed as HRs with 95% CI, while continuous outcomes were expressed as means and SD, and standardised mean differences. Meta-analyses were performed to pool data and to obtain overall effect sizes using a random-effects model. Event rate data were available for mortality and were pooled to determine effect size as RR. For other continuous outcomes, standardised mean differences were determined from taking the means and SD of the intervention and control groups. A two-sided p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Additional subgroup analyses were done separately according to study design (observational studies or RCTs), drug class, presence of AVR, country, age, severe AS only and LV ejection fraction (LVEF), if each subgroup has more than one study. Heterogeneity between studies was tested for each outcome using I2 statistic (where 0%–40% is not important, 30%–60% is moderate, 50%–90% is substantial and 75%–100% is considerable).37 Funnel plots, Egger test and p curve analyses were used to assess publication bias.38 All statistical analyses were conducted in R (R Project for Statistical Computing, V.3.5.3).39

Public and patient involvement

This systematic review arose from clinical observation and discussion with individual patients with AS, but there was no systematic public involvement in the research process, design of and interpretation of results from this systematic review. However, the findings of this review will be shared with members of the public, patient and other healthcare professionals via news and educational meetings.

Results

Search results and study characteristics

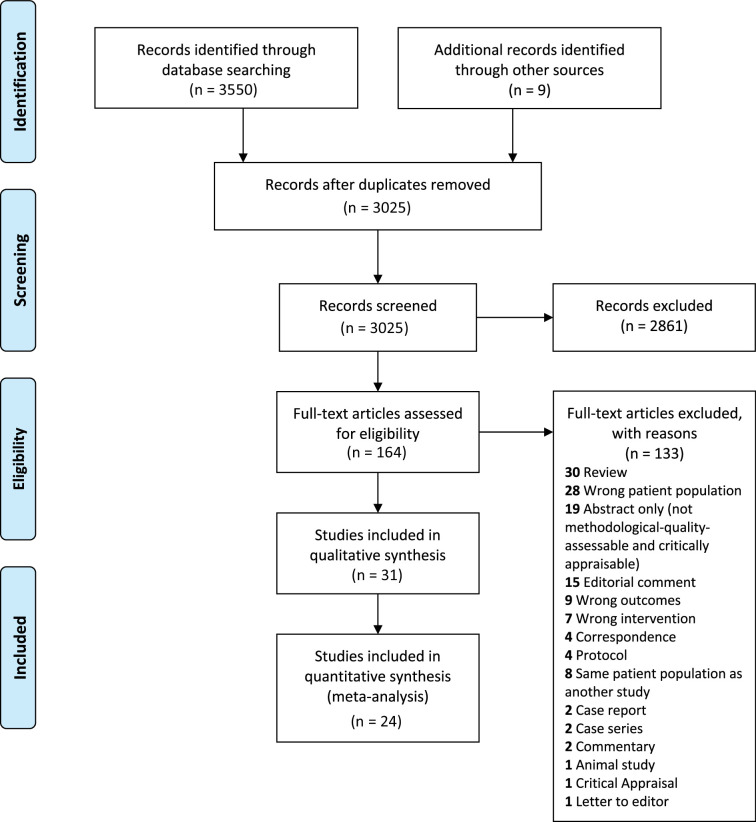

Among 3025 unique citations screened, 31 studies (n=26 500),21 40–72 consisting of eight RCTs, 16 cohort, one cross-over and six uncontrolled studies, were included in the qualitative analysis, and 24 studies were included in the meta-analysis (figure 1). Study characteristics are summarised in table 1. Sample sizes ranged from 15 to 15 896 patients. The follow-up period was at least 1 year for 50% of the studies. The clinical effect of RAAS inhibitors (RAASi) was assessed in 19/30 (63.3%), nitroprusside in 4/30 (13%—all uncontrolled studies), beta-blockers (BB) in 3/31 (9.7%), calcium channel blocker (CCB) in 1/31 (3.2%), frusemide in 1/31 (3.2%), RAASi or BB in 2/31 (6.5%) and RAASi or BB or diuretics in 1/31 (3.2%) of studies. Clinical outcomes of AHT following transcatheter AVR, surgical AVR and without AVR were explored in 26.7%, 13.3% and 60% of studies, respectively.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection.

Table 1.

Description of included studies

| Study | Sample size | Country | Study design | Inclusion criteria | Intervention | Group differences | Data collection period | Outcomes | Follow-up duration |

| Okoh40 | 602 | USA | Retrospective cohort study | Ageing patients undergoing TAVR | RAASi | RAASi vs no RAASi | – | AKI, GFR | – |

| Pino/Alrifai BB group41 42 | 372 | USA | Retrospective cohort study | Severe AS, who underwent TAVR | BB or RASi | BB, RASi, both vs without | April 2012 - March 2016 | Mortality, length of stay, AKI, stroke, heart failure readmission | 1 year |

| Rodriguez-Gabella43 | 2785 | Spain | Retrospective cohort study | Consecutive patients undergoing TAVR | RAASi | RASi vs no RASi | August 2007 - August 2017 | All-cause/CV mortality, NOAF, cerebrovascular events, readmission NYHA class III/IV, LVEF, AVA, mean transaortic gradient, EDV, ESV, septal hypertrophy | 3 years |

| Saeed73 | 314 | UK | Retrospective cohort study | Asymptomatic moderate or severe AS | CCB | CCB vs no CCB | January 2000–May 2017 | All-cause mortality, HF-readmissions | Mean 34.5 months (median 25 months) |

| Younis44 | 1383 | Israel | Prospective cohort study | Symptomatic, severe AS, who underwent TAVR | BB | BB stopped vs continued | March 2009 - April 2017 | HD-AVB, NOAF | Mean 4 days post-op |

| Inohara45 | 15 896 | USA | Retrospective cohort study | >65 years old with Medicare and underwent TAVR | RAASi | With or without RASi | July 2014 - January 2016 | All-cause mortality, HF readmission, KCCQ | 1 year |

| Magne46 | 192 | France | Retrospective cohort study | Severe AS, who underwent SAVR (AVA≤1 cm2, AVAi ≤0.6 cm2/m2, MPG >40 mm Hg) | RAASi (25% ACEI, 28% ARB) | Started RASi before surgery vs not | January 2005–January 2014 | All-cause mortality, operative mortality, survival | Mean 4.8±2.7 years |

| Ochiai47 | 560 | Japan | Retrospective cohort study | Symptomatic severe AS undergoing TAVR | RAASi | RAASi vs no RAASi | October 2013–April 2016 | Mortality, major/minor vascular complications, bleeding, conversion to open heart surgery, periprocedural myocardial injury, stroke, AKI, AF, PPM, echo (LVMI, etc) | Median 1.1 year |

| Goh48 | 428 | Singapore | Retrospective cohort study | Severe AS (AVA ≤1) with preserved LVEF ≥50% | RAASi (ARB/ACEi) | RAASi vs no RAASi | 2005–2014 | Echo, LV parameters | – |

| Hansson49 | 38 | Denmark | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | Asymptomatic moderate or severe AS (peak velocity >3.0 m/s), HR ≥60 bpm | Extended release of metoprolol uptitration <6 weeks, target dose set individually 50–200 mg/day | Metoprolol vs placebo | August 2013 - April 2016 | Haemodynamic, echo parameters, exercise test | 22 weeks |

| Lloyd50 | 41 | USA | Uncontrolled observational study | Severe AS, who underwent SAVR (AVA <1 cm2, AVAi <0.6 cm2/m2, MPG <40 mm Hg with preserved EF ≥50%) | Nitroprusside | Subdivided group to low-flow vs high-flow | January 1, 2007–March 1, 2017 | Haemodynamic, echo parameters | Median 1.35–2.4 years |

| Amsallem51 | 288 | France | Retrospective cohort study | Underwent TAVR | BB | Thoracic radiation therapy vs without (looked at BB vs without in radiation group) | – | Mortality | Median 3.4 years |

| Barbanti52 | 112 | Italy | Randomised, open-label trial | Symptomatic severe AS undergoing TAVR | RenalGuard (frusemide) | RenalGuard vs normal saline solution | Feb 2014–Jan 2015 | All-cause mortality, CV mortality, stroke/TIA, PPM, bleeding, major vascular complication, AKI | 30 days |

| Bull53 | 96 | UK | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | >18 years old with asymptomatic, moderate or severe AS and did not have indications for SAVR | Ramipril 2.5 mg/day x 2 weeks then 5 mg/day x 5 months then 10 mg/day till end of study | Ramipril vs placebo | October 2008 - December 2011 | LVMI, LVEF, myocardial functional parameters, echo parameters, BNP, distance walked | 1 year |

| Helske-Suihko54 | 51 | Finland | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | Symptomatic severe AS considered for SAVR | Candesartan | Candesartan vs placebo | May 2009–August 2012 | HR, blood pressure, exercise capacity, LV parameters, and NT-proBNP | 1 year |

| Rossi55 | 113 | Italy | Retrospective cohort study | Symptomatic severe AS | BB (atenolol 16%, carvedilol 19%, metoprolol 5%, bisoprolol 60%) | With or without BB | – | All-cause mortality | Mean 10 months |

| Dalsgaard56 | 44 | Denmark | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | Severe AS | Trandolapril dose increased from 0.5 to 1 mg on day 2, and 2 mg on day 3 | Trandolapril vs placebo | Nov 2005-Dec 2009 | Haemodynamic, echo parameters | Median 49 days (IQR: 29–55)(outcomes at day 3) |

| Goel57 | 1752 | UK | Retrospective cohort study | Severe AS, who underwent SAVR | RAASi | RAASi vs no RAASi | January 1, 1991–Dec 31, 2010 | Mortality, survival, echo parameters | Median 5.8 years |

| Dahl58 59 | 91 | Denmark | Randomised, open-label trial | Symptomatic severe AS undergoing AVR | Candesartan | candesartan vs conventional therapy | Feb 2006–April 2008 | Haemodynamic, echo parameters | 1 year |

| Eleid21 | 24 | USA | Uncontrolled observational study | Symptomatic patients with hypertension (aortic systolic pressure >140 mm Hg) and low-gradient (MPG <40 mm Hg) severe AS (AVA <1 cm2) with preserved ejection fraction (LVEF >50%) | Nitroprusside | – | January 1, 2006–May 1, 2013 | Haemodynamic, echo parameters | – |

| Nadir (severe AS group)60 | 532 | Scotland | Retrospective cohort study | AS (for meta-analysis only included severe) | RAASi (ACEI/ARB) | RAASi (ACEI/ARB) vs not | Sept 1993 - July 2008 | Mortality | 4.2 years |

| Rosenhek61 | 116 | Austria | Uncontrolled prospective observational study | Asymptomatic, very severe AS, peak velocity ≥5 m/s | RAASI n=46, BB n=16 | – | 1995–2008 | Event-free survival rate | Median 41 months (26–63 months) |

| Tatu62 | 28 | NA | Cohort study | Hypertension and AVR for AS | Telmisartan 80 mg/day (n=16) vs carvedilol 25 mg/day (n=12) | Telmisartan 80 mg/day (n=16) vs carvedilol 25 mg/day (n=12) | – | Systolic and diastolic LV function | 6 months |

| Stewart63 | 65 | New Zealand | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | Asymptomatic, moderate or severe AS (peak velocity >3.0 m/s), LVEF >50% | Eplerenone, 50 mg/day increased to 100 mg/day after 1 month (aldosterone-receptor antagonist) Diruetic/RAASi | eplerenone vs placebo | – | Haemodynamic, echo parameters, physical function | Median 19 months (IQR: 15–25) |

| Varadarajan /Pai64 65 | 453 | USA | Retrospective cohort study | Severe AS (AVA ≤0.8 cm2) | 17% BB, 24% ACEI | – | 1993–2003 | Mortality, survival | Mean 3.5 years |

| Jiménez-Candil66 | 20 | Spain | Observational, drug withdrawal, single blinded study, with randomisation of the order of tests | Moderate or severe AS (peak aortic velocity ≥2.5 m/s, AVA ≤1.2 cm2), and concomitant treatment with ACEI for at least 3 months, prescribed for arterial hypertension | ACEI | With or without ACEI | – | HR, SBP, DBP, SV, CO, SVR, MPG, AVA, LV end systolic wall stress | Five half-lives of each drug |

| Khot/Popović67 68 | 25 | USA | Uncontrolled prospective observational study | Admitted to ICU, left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVEF ≤35%), and severe AS (AVA ≤1 cm2), depressed CI ≤2.2 L/min/m2 | Nitroprusside 128±96 mcg/min | – | August 1, 2000–May 15, 2002 | HR, AVA, LVEF, PCWP, RAP, SV, peak/mean PG, MAP | 24 hours |

| Chockalingam69 | 52 | India | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | Severe AS (AVA <0.75 cm2, MPG >50 mm Hg, aortic valve Doppler jet >4.5 m/s), symptomatic NYHA III/IV dyspnoea or angina | Enalapril | Enalapril vs placebo | – | Haemodynamic, echo parameters, 6MWT | 3 months |

| Martínez Sánchez70 | 22 | Mexico | Uncontrolled observational study | >18 years old, critical AS | Captopril | – | May 1993-May 1995 | Haemodynamic, echo parameters | – |

| Friedrich71 | 28 | Belgium, Switzerland, USA | Cohort study | Compensated AS (MPG 57±4 mm Hg; AVA 0.7±0.1 cm2; wall thickness 14.3±0.5 mm) | Enalaprilat infusion 0.05 mg/min into left coronary artery | Enalaprilat vs vehicle | – | Haemodynamic, echo parameters | 15 min |

| Awan72 | 15 | USA | Uncontrolled observational study | Severe AS (AVAi 0.37±0.03 cm2/m2) | Nitroprusside mean 33 mcg/min | – | – | Haemodynamic, echo parameters | 5 min |

ACEI, ACE inhibitors; AKI, acute kidney injury; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blockers; AS, aortic stenosis; AVA, aortic valve area; AVAi, aortic valve area index; BB, beta blockers; CCB, calcium channel blockers; CI, Cardiac Index; CO, cardiac output; CV, cardiovascular; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; echo, echocardiography; EDV, end-diastolic volume; ESV, end-systolic volume; GFR, glomerular filtration; HD-AVB, high degree atrioventricular block; HR, heart rate; ICU, intensive critical unit; KCCQ, kansas city cardiomyopathy questionnaire; LV, left ventricular; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MAP, mean arterial pressure; MPG, mean pressure gradient; 6MWT, six min walking test; NOAF, new-onset atrial fibrillation; NYHA, New York heart association; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PPM, permanent pacemaker; RAASi, renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors; RAP, right arterial pressure; RASi, renin–angiotensin–system inhibitors; SAVR, surgical aortic valve replacement; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SV, stroke vol; SVR, systemic vascular resistance; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement; TIA, transient ischaemia attack.

Patient characteristics

Baseline patient characteristics of each study are summarised in tables 2 and 3. Overall, the mean age was 83.7±7.9 years, there were 11 960 females (47.2%), and 70.6% of patients had New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III or IV heart failure. Common comorbidities were dyslipidaemia (54.3%), diabetes (34.3%), coronary artery disease (35.5%), atrial fibrillation (34.3%), moderate or severe mitral regurgitation (12.8%) and moderate or severe aortic regurgitation (5.1%). The mean aortic valve area was 0.7 (SD:0.3) cm2, peak velocity was 4.3 (SD:0.7) m/s, pressure gradient was 48.5 (SD:14.9) mm Hg, LV ejection fraction was 52.2% (SD:12.4%) and LV mass index was 131.1 (SD:38.5) g/m2.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of included studies

| Study | Females, n (%) | Age, mean (SD) in years | BMI, mean (SD) in kg/m2 | HR, mean (SD) in bpm | SBP, mean (SD) in mm Hg | DBP, mean (SD) in mm Hg | NYHA class III or IV, n (%) | Hypertension, n (%) | Diabetes, n (%) | Dyslipidaemia, n (%) | CAD, n (%) | COPD, n (%) | Past stoke or TIA, n (%) | History of AF, n (%) | PVD, n (%) | Previous MI, n (%) | Previous PCI, n (%) | Previous CABG, n (%) | SCr, mean (SD) in mg/dL | eGFR, mean (SD) in mL/min/1.73 m2 |

| Okoh40 | – | 84 (8) | 28.2 (6.5) | – | – | – | – | 518 (86) | 224 (37.2) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 55.7 (29.7) |

| Pino/Alrifai BB group41 42 | 158 (42.5) | 84.9 (6.7) | – | – | – | – | – | 291 (78.2) | 79 (21.2) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1.1 (0.6) | – |

| Rodriguez-Gabella43 | 1507 (54.1) | 80.8 (7.1) | 27.9 (5.1) | – | – | – | 1546 (55.5) | 2257 (81) | 959 (34.4) | 1530 (54.9) | 921 (33.1) | 644 (23.1) | 282 (10.1) | 855 (30.7) | 298 (10.7) | 389 (14) | 514 (18.5) | 222 (8) | – | – |

| Saeed73 | 100 (31.8) | 65 (12) | – | – | 141.8 (19.1) | 82 (12.5) | – | 228 (72.6) | 43 (13.7) | 207 (65.9) | 158 (50.3) | – | 39 (12.4) | 40 (12.7) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Younis44 | 407 (29.4) | 82 (7) | 27.5 (5) | – | – | – | – | 670 (48.4) | 301 (21.8) | – | – | – | 134 (9.7) | 249 (18) | 105 (7.6) | – | – | – | – | 63.5 (28.3) |

| Inohara45 | 7639 (48.1) | 82.4 (6.8) | 28.3 (6.6) | – | – | – | 12 664 (79.7) | 14 842 (93.4) | 6151 (38.7) | – | – | 3939 (24.8) | 3421 (21.5) | 6345 (39.9) | 4845 (30.5) | 3825 (24.1) | – | 4555 (28.7) | – | 63.7 (24.7) |

| Magne46 | 85 (44.3) | 74 (9.5) | 28 (5) | 72 (8.6) | 129.5 (13.3) | 72 (9) | 53 (27.6) | 174 (90.6) | 35 (18.2) | 110 (57.3) | – | 39 (20.3) | 12 (6.3) | 9 (4.7) | 9 (4.7) | – | 10 (5.2) | – | 0.7 (0.7) | – |

| Ochiai47 | 377 (67.3) | 84.4 (5) | 22.2 (3.7) | – | – | – | 276 (49.3) | 427 (76.3) | 149 (26.6) | – | 218 (38.9) | 99 (17.7) | – | 135 (24.1) | 74 (13.2) | 45 (8) | 161 (28.8) | 39 (7) | – | 54.1 (20.3) |

| Goh48 | 224 (52.3) | 72.4 (13.4) | – | – | – | – | – | 248 (57.9) | 171 (40) | 206 (48.1) | – | – | – | – | – | 26 (6.1) | – | – | – | – |

| Hansson49 | 14 (36.8) | 70 (5) | 26.5 (3.5) | 69.5 (7.9) | 142 (12.5) | 81 (8.4) | – | 21 (55.3) | 4 (10.5) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Lloyd50 | 26 (63.4) | 76.9 (10.4) | – | 71.1 (12.6) | 157.5 (30.8) | 69.4 (12.8) | 33 (80.5) | 37 (90.2) | 10 (24.4) | 17 (41.5) | 32 (78) | 10 (24.4) | 3 (7.3) | 17 (41.5) | – | – | 8 (19.5) | 9 (22) | – | – |

| Amsallem51 | 150 (52.1) | 72 (13) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Barbanti52 | 67 (59.8) | – | 27 (4.7) | – | – | – | 92 (82.1) | 91 (81.3) | 38 (33.9) | 57 (50.9) | – | 21 (18.8) | 7 (6.3) | – | 17 (15.2) | 10 (8.9) | 18 (16.1) | 9 (8) | – | – |

| Bull53 | 25 (26) | 68.6 (14.1) | 28.6 (5.1) | – | 132.4 (17.1) | 77 (7.6) | – | 28 (29.2) | 3 (3.1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 (1) | – | 4 (4.2) | – | – |

| Helske-Suihko54 | 27 (52.9) | 71.5 (10.6) | 25.5 (4.2) | – | – | – | 10 (19.6) | 11 (21.6) | 6 (11.8) | – | 11 (21.6) | – | – | 5 (9.8) | – | – | – | – | 0.9 (0.2) | – |

| Rossi55 | 62 (54.9) | 82 (8) | – | – | 112.4 (18.8) | 63.5 (10.2) | – | 144 (127.4) | 49 (43.4) | – | 93 (82.3) | 46 (40.7) | 17 (15) | 76 (67.3) | – | – | – | – | 1.7 (1.3) | – |

| Dalsgaard56 | 16 (36.4) | 70 (8.4) | – | – | – | – | – | 23 (52.3) | 9 (20.5) | – | 13 (29.5) | 4 (9.1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Goel57 | 688 (39.3) | 72 (9.5) | 29 (6.6) | – | – | – | 420 (24.4) | 1269 (72.4) | 400 (23.6) | – | – | 230 (13.1) | 118 (6.7) | 111 (6.3) | – | 328 (18.7) | – | 846 (48.3) | 1.1 (0.5) | – |

| Dahl58 59 | 33 (36.3) | 71.5 (9.6) | – | – | 147 (20.9) | 78.5 (13) | 24 (26.4) | 39 (42.9) | 12 (13.2) | – | 19 (20.9) | – | 7 (7.7) | 14 (15.4) | 9 (9.9) | – | – | 29 (31.9) | – | – |

| Eleid21 | – | – | – | 74 (12) | 150 (26) | 66 (9) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Nadir (severe AS group)60 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Rosenhek61 | 57 (49.1) | 67 (16) | – | – | – | – | – | 64 (55.2) | 10 (8.6) | 36 (31) | 26 (22.4) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Tatu62 | 10 (35.7) | 67 (7) | – | – | 167.3 (7.4) | 102.1 (5.2) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Stewart63 | 15 (23.1) | 67.5 (10) | 27 (3.5) | 62 (9.8) | 144.5 (18.2) | 82 (10.5) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Varadarajan/Pai64 65 | 236 (52.1) | 75 (13) | – | – | – | – | – | 159 (35.1) | 63 (13.9) | – | 154 (34) | – | 50 (11) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Jiménez-Candil66 | 7 (35) | 71.6 (9.2) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 5 (25) | – | – | 6 (30) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Popovic/Khot67 68 | 9 (36) | 73 (15) | – | 91 (9) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 17 (68) | – | 9 (36) | – | – |

| Chockalingam69 | 13 (25) | 44 (11.3) | – | 83 (8) | – | – | 52 (100) | – | 2 (3.8) | – | 5 (9.6) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Martínez Sánchez70 | 10 (45.5) | 49.9 (26.3) | – | – | – | – | – | 12 (54.5) | 6 (27.3) | 14 (63.6) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Friedrich71 | 12 (42.9) | 70.3 (6.9) | – | 74.1 (3.5) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0 (0) | – | – | 0 (0) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Awan72 | – | 64.1 (8.3) | – | 73 (3) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Pooled | 11 960 (47.2) | 83.7 (7.9) | 28.1 (6.3) | 73.9 (9.0) | 138.5 (18.6) | 76.7 (10.9) | 15 170 (70.6) | 21 532 (84.7) | 8720 (34.3) | 2177 (54.3) | 1655 (35.5) | 2,1495 (23.4) | 4090 (17.7) | 7862 (34.3) | 21 019 (25.5) | 4641 (21.4) | 3690 (19.3) | 21 358 (26.8) | 1.1 (0.6) | 63.1 (25.0) |

AF, atrial fibrillation; BMI, body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD, coronary artery disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HR, heart rate; MI, myocardial infarction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SCr, serum creatinine; TIA, transient ischaemia attack.

Table 3.

Echocardiographic parameters of included studies

| Study | AVA, mean (SD) in cm2 | AVAi, mean (SD) in cm2/m2 | Peak velocity, mean (SD) in m/s | MPG, mean (SD) in mm Hg | Peak PG, mean (SD) in mm Hg | LVEF, mean (SD) in % | LVMI, mean (SD) in g/m2 | E/A ratio, mean (SD) | E/e' ratio, mean (SD) |

| Okoh40 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Pino/Alrifai BB group41 42 | 0.7 (0.2) | – | – | 49.4 (13.2) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Rodriguez-Gabella43 | 0.7 (0.2) | – | – | 47.9 (16.1) | – | 47.9 (16.1) | – | – | – |

| Saeed73 | 0.9 (0.2) | – | 3.7 (0.7) | 34.5 (13.5) | – | 60.7 (7.3) | 51.8 (17.2) | ||

| Younis44 | 0.7 (0.5) | – | – | 44.4 (3.5) | 70.9 (6) | – | – | – | – |

| Inohara45 | – | – | – | – | – | 52 (11.5) | – | – | – |

| Magne46 | 0.7 (0.2) | – | – | 51 (16.6) | – | 65.5 (12.5) | – | – | – |

| Ochiai47 | 0.6 (0.2) | 0.4 (0.1) | 4.6 (0.8) | 50.7 (17.9) | – | 63 (12.7) | 132.3 (37.4) | – | |

| Goh48 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Hansson49 | – | 0.5 (0.1) | – | 31 (11.8) | 53 (19.4) | 72.5 (5) | 83.5 (18.3) | 0.85 (0.3) | 16.1 (4.8) |

| Lloyd50 | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.5 (0.1) | – | 25.2 (6.1) | – | 64 (6) | – | 0.7 (0.6) | 15.2 (9.1) |

| Amsallem51 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Barbanti52 | 0.7 (1.7) | – | – | 50.5 (13.8) | 82.7 (19.9) | 54.6 (11.1) | – | – | – |

| Bull53 | 1.2 (0.4) | – | 3.4 (0.5) | – | – | 71.7 (8.1) | 80.1 (19.9) | – | 11.6 (5.4) |

| Helske-Suihko54 | – | 0.4 (0.1) | – | – | – | 65.5 (6.6) | – | – | – |

| Rossi55 | 0.7 (0.2) | – | – | 48 (16) | – | 46 (15) | – | – | – |

| Dalsgaard56 | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.4 (0.1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 19 (7) |

| Goel57 | 0.7 (0.1) | – | – | 47.7 (16.2) | 80.3 (25.6) | – | 128 (39.6) | – | |

| Dahl58 59 | 0.8 (0.3) | – | 3.9 (0.8) | – | – | 54.5 (7.5) | 131.5 (39.9) | ||

| Eleid21 | 0.8 (0.1) | – | – | 26 (5) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Nadir (severe AS group)60 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Rosenhek61 | 0.6 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.1) | 5.4 (0.4) | 74.5 (11.2) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Tatu62 | 0.8 (0.2) | – | – | 62 (19) | 116 (12) | – | – | – | – |

| Stewart63 | 0.9 (0.3) | – | 3.9 (0.6) | – | – | 65 (8.6) | 47 (10.6) | – | 11.2 (4.6) |

| Varadarajan/Pai64 65 | 0.7 (0.2) | 0.4 (0.1) | – | 40 (16) | 65 (24) | 52 (21) | – | – | – |

| Jiménez-Candil66 | – | – | – | – | – | 61.2 (8.5) | – | – | – |

| Popovic/Khot67 68 | 0.6 (0) | – | – | 38 (4) | 64 (8) | 21 (8) | – | – | |

| Chockalingam69 | – | – | – | 74.1 (25) | 105.1 (33) | 62.9 (11.5) | – | 1.1 (0.3) | – |

| Martínez Sánchez70 | – | – | – | 93 (38) | – | 62 (16) | – | – | – |

| Friedrich71 | 0.7 (0.1) | – | – | 58.4 (5.4) | – | 52 (4) | – | 1.1 (0.4) | – |

| Awan72 | 0.4 (0.1) | – | – | – | 58 (4) | 71.7 (10.3) | – | – | – |

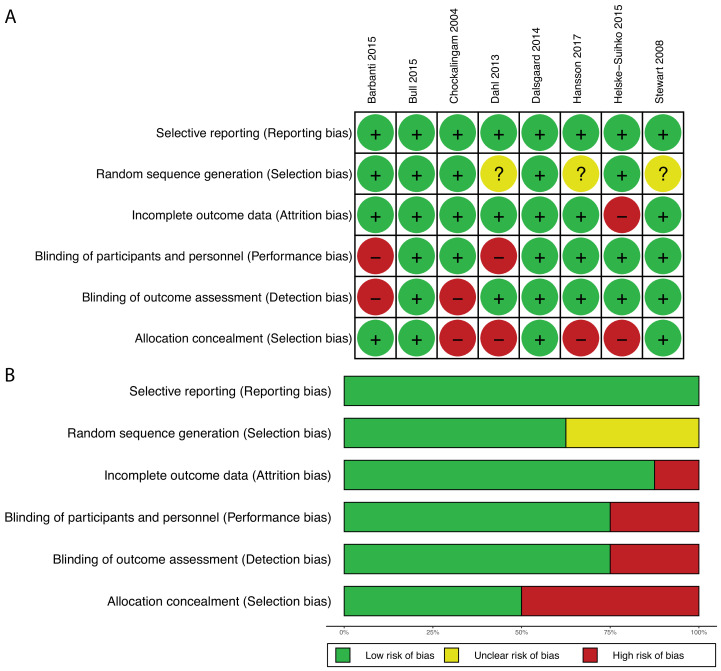

Risk of bias and quality assessments.

AVA, aortic valve area; AVAi, Aortic Valve Area Index; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVMI, left ventricular mass index; MPG, mean pressure gradient; PG, pressure gradient.;

Risk of bias and quality assessments

Eight studies were RCTs. Based on the Cochrane Collaboration tool, five out of eight trials had some risk of bias. However, 63% of trials had low risk of selection bias (through use of random sequence generation), 50% had low risk of selection bias (from allocation concealment), 75% had low risk of performance bias (from blinding of participants and personnel), 75% had low risk of detection bias (from blinding of outcome assessment), 88% had low risk of attrition bias (from incomplete outcome) and 100% had low risk of reporting bias (figure 2). Most of the included studies (73%) were observational cohort studies, and the majority were of good (63%) or fair (17%) quality based on the Newcastle Ottawa Scale (online supplemental materials).

Figure 2.

Risk-of-bias assessment of randomised controlled trials. Risk-of-bias summary (A) and graph (B).

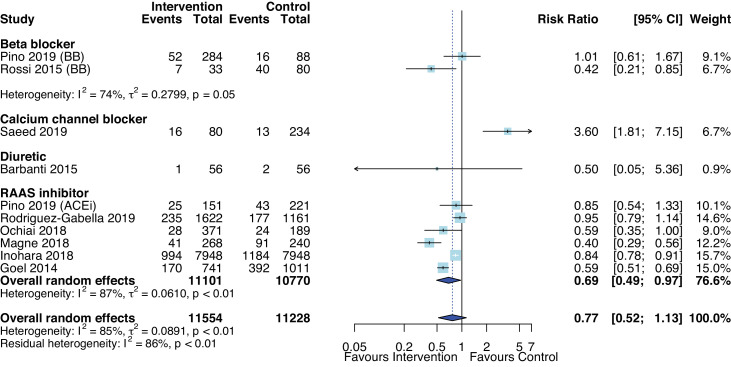

Primary efficacy and safety outcome: all-cause mortality

Overall, AHT was not associated with risk of all-cause mortality (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.13, p=0.16, figure 3) compared with no AHT or placebo in nine studies (n=22 468)41 43 45–47 52 55 57 73 with substantial heterogeneity (I2=85%, p<0.01). Most studies assessed effects of RAASi and found that RAASi were associated with reduced risk of all-cause mortality (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.97, p=0.04, I2=86.9%) with median follow-up ranging from 1 to 5.8 years. The pooled random effect of BB versus without BB from two studies with median follow-up of 10–12 months was not significantly different.41 55 Similarly, one study did not find a difference in mortality risk between frusemide-induced diuresis with matched isotonic intravenous hydration and normal saline solution with follow-up period of 30 days. One observational study (the Exercise Testing in Aortic Stenosis (EXTAS) cohort study) found CCB was associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality (34% in patients who received CCB vs 23% without CCB, p=0.049) over a median follow-up of 25 months.73 Furthermore, AHT was associated with reduced all-cause mortality after transcatheter AVR (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.79 to 0.93, p=0.004, I2=0%). All studies included patients with severe AS, and only one of eight studies were randomised.52

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the effect of antihypertensive therapies on all-cause mortality at follow-up. ACEi, ACE inhibitor; BB, beta-blockers.

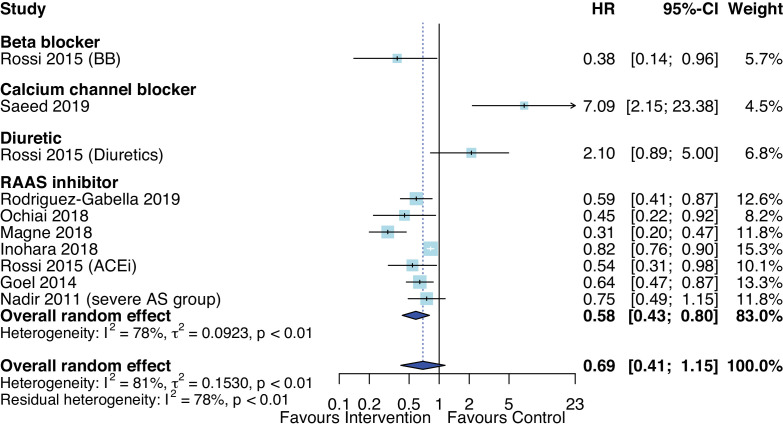

In eight observational studies that reported HRs, the pooled HR was not statistically significant, with substantial heterogeneity across studies (I2=77%, p<0.01).42–44 47 57 58 73 There was a statistically significant difference between drug class (p<0.0001), however, only one study assessed each drug class: BB, CCB and diuretics compared with seven studies that assessed RAASi (figure 4). From studies that conducted survival analyses, RAASi was also associated with reduced all-cause mortality with pooled HR of 0.58 (95% CI 0.43 to 0.80, p=0.006) with median follow-up ranging from 10 months to 5.8 years. The EXTAS study found that CCB was associated with 7-fold increased risk of all-cause mortality based on a multivariate Cox regression model.73 When stratified by mean age, AHT was significantly associated with reduced mortality in studies with mean age over 70 years (HR 0.54, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.80). However, when stratified by LV ejection fraction by at least 50% vs over 50%, there was no difference in mortality.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of the effect of antihypertensive therapies on HR of all-cause mortality at follow-up. ACEi, ACE inhibitor; AS, aortic stenosis; RAAS, renin-angiotensin and aldosterone systems.

Secondary outcomes

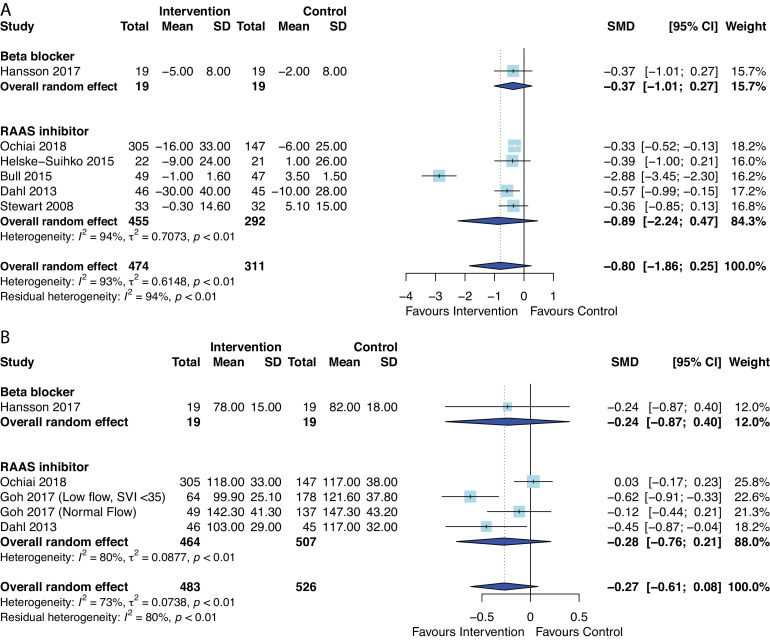

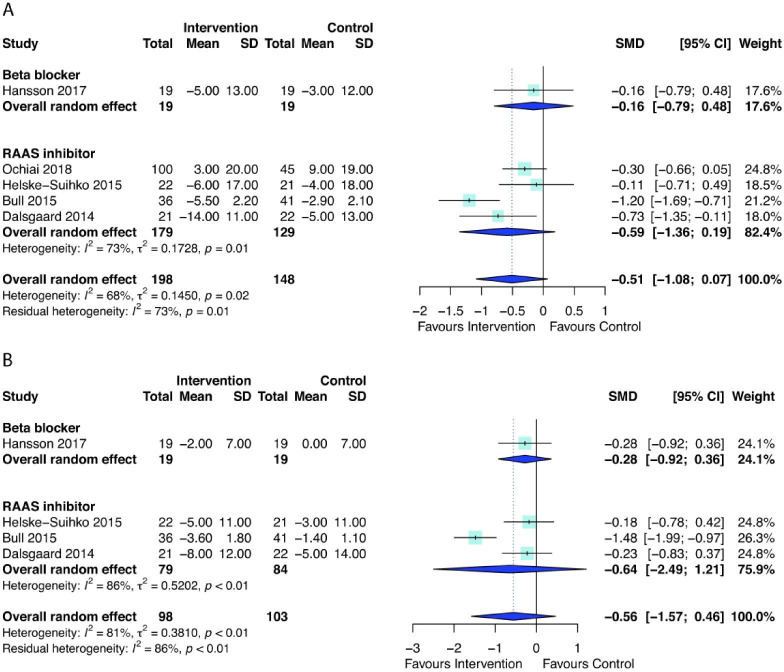

AHT did not have a significant effect on change in LV mass index (standardised mean difference=−0.80, 95% CI −1.86 to 0.25, p=0.11) or LV mass index at median follow-up duration ranging from 22 weeks to 1.1 years (standardised mean difference=−0.27, 95% CI −0.61 to 0.08, p=0.10), although there was substantial heterogeneity (I2=93% and 73%, respectively) (figure 5). When meta-analysis was limited to only RCTs (5/6 studies), AHT was still not significantly associated with LV mass index (standardised mean difference=−0.91, 95% CI −2.27 to 0.45, p=0.14). Similarly, the effects of AHT on changes of systolic blood pressure (figure 6A, standardised mean difference=−0.51, 95% CI −1.08 to 0.07, p=0.07) or diastolic blood pressure (figure 6B, standardised mean difference=−0.56, 95% CI −1.57 to 0.46, p=0.18), compared with controls was not statistically significant, but favoured use of AHT. The median follow-up ranged from 49 days to 1.1 years. Meta-analyses after removing studies with short-term (49 days) follow-up56 or only including RCTs49 53 54 56 showed consistent findings of no statistical difference in changes in blood pressures.

Figure 5.

Forest plot of the effect of antihypertensive therapies on (A) change in Left Ventricular Mass Index (LVMI) and (B) post-LVMI. RAAS, renin–angiotensin and aldosterone systems; SMD, standardised mean difference.

Figure 6.

Forest plot of the effect of antihypertensive therapies on change in (A) systolic blood pressure and (B) diastolic blood pressure during follow-up. RAAS, renin-angiotensin and aldosterone systems; SMD, standardised mean difference.

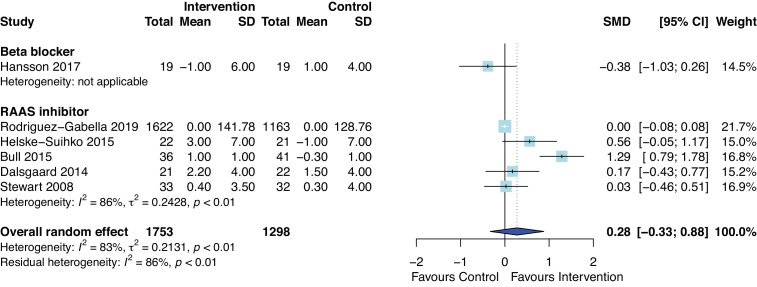

The effect of AHT on change of LV ejection fraction was not statistically significant (figure 7, standardised mean difference=0.28, 95% CI −0.33 to 0.88, p=0.29) with follow-up period ranging from 49 days to 3 years. When study with short term follow-up (49 days)56 was removed or only included RCTs,49 53 54 56 63 results of meta-analyses were consistent and showed no difference in change in LV ejection fraction.

Figure 7.

Forest plot of the effect of antihypertensive therapies on change in left ventricular ejection fraction during follow-up. RAAS, renin–angiotensin and aldosterone systems; SMD, standardised mean difference.

The Ramipril In Aortic Stenosis (RIAS) trial demonstrated a modest, but significant regression of LVH in ramipril group versus placebo group over a year (mean change in LV mass of −3.9 vs +4.5 g, respectively, p=0.006), which could not be explained by reduction in systolic (p=0.374) or diastolic blood pressures (p=0.16).53 This trial also found a trend towards reduced progression of AS, but was not statistically different (mean change in aortic valve area of 0 cm2 in ramipril group vs −0.2 cm2 in placebo group, p=0.067). Similarly, in another RCT, angiotensin receptor blockage with candesartan after AVR was associated with significant LVH regression compared with standard treatment (mean change in LV mass index of −30 vs −12 g/m2, p=0.015), but no significant difference in change in systolic blood pressure during 12-month follow-up.58 The Optimised CathEter vAlvular iNtervention-transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) registry also showed that using propensity score-matched cohort analysis, patients with RAASi postoperatively had greater LVH regression than without (mean change in LV mass index of −9 vs −2 g/m2, p=0.024) in 6 months post-AVR.47

Safety outcomes post-AVR

Overall, post-TAVI, the risk of acute kidney injury was not significantly lower in patients on AHT compared with controls (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.35 to 1.84, p=0.47), but substantial heterogeneity was demonstrated (I2=53%). An RCT called the PROphylactic effect of frusemide-induCed diuresis with matched isotonic intravenous hydraTion in TAVI showed that frusemide-induced diuresis reduced incidence of acute kidney injury post-TAVI, but the duration of follow-up was only 30 days.52 Furthermore, an observational study in TAVI patients found that glomerular filtration rate increased from baseline more significantly in RAASi patients (40%) compared with non-RAASi (29%) (p=0.001) and RAASi was independently associated with reduction in risk of development of postoperative AKI (OR 0.51, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.91, p=0.0024).40 Other outcomes such as hospital readmission (p=0.24), atrial fibrillation (p=0.92), stroke (p=0.31) and need for permanent pacemaker implantation (p=0.94) were also not statistically significant (table 4) with follow-up period ranging from 30 days to 3 years. When meta-analyses were excluded studies of less than 1-year follow-up,44 52 no statistical differences in outcomes were still observed.

Table 4.

Pooled risk ratios for postaortic valve replacement complications, haemodynamic and echocardiographic parameter changes with antihypertensive therapies at follow-up

| Postoperative complications | No of studies | Risk ratio | 95% CI | P value | I2 (%) |

| Postoperative atrial fibrillation | 6 | 0.98 | 0.64 to 1.50 | 0.92 | 81.2 |

| Postoperative stroke or transient ischaemic attack | 4 | 0.45 | 0.06 to 3.69 | 0.31 | 86.9 |

| Acute kidney injury | 3 | 0.8 | 0.35 to 1.84 | 0.47 | 53 |

| Permanent pacemaker | 5 | 0.99 | 0.62 to 1.58 | 0.92 | 70 |

| Readmission | 5 | 0.79 | 0.40 to 1.60 | 0.43 | 82 |

| Haemodynamic and echocardiographic parameters | No of studies | SMD | 95% CI | P value | I2 (%) |

| Post-mean arterial pressure | 3 | −0.62 | −2.85 to 1.60 | 0.35 | 79 |

| Change in heart rate | 3 | −0.41 | −1.71 to 0.88 | 0.3 | 61 |

| Post-heart rate | 3 | −0.68 | −2.60 to 1.23 | 0.26 | 80 |

| Change in aortic valve area | 3 | 0.09 | −0.36 to 0.54 | 0.48 | 37 |

| Post-aortic valve area | 3 | 0.01 | −0.14 to 0.16 | 0.89 | 0 |

| Post-mean pressure gradient | 3 | −0.16 | −0.55 to 0.23 | 0.28 | 25 |

| Post-deceleration time | 3 | 0.03 | −0.23 to 0.30 | 0.71 | 0 |

| Post-E/A ratio | 3 | −0.06 | −0.43 to 0.32 | 0.67 | 23 |

| Post-E/e’ ratio | 4 | 0.16 | −0.56 to 0.87 | 0.54 | 65 |

Other haemodynamic and echocardiographic changes.

SMD, standardised mean difference.;

Although some asymmetry was found in funnel plots, the publication bias appears low using Egger’s tests (p=0.14), and p value analyses (see online supplemental materials). Of nine studies/subgroups in the mortality analysis, 4 had p value lower than 0.025, and the power of the analysis was 65% (95% CI 23.9% to 90.3%). These p curve estimates suggest that evidential value is present, and that the results are not the product of publication bias and ‘p-hacking’ alone.

Other haemodynamic and echocardiographic changes

Favourable outcomes such as improved haemodynamic parameters and LV function were described in some studies. However, when data were pooled in meta-analyses, there were no statistically significant differences between AHT or placebo/without AHT for mean arterial pressure (three studies with follow-up period 15 min to 22 weeks), heart rate (three studies with follow-up period of 49 days to 1 year), aortic valve area (three studies with follow-up period of 19 months to 3 years), mean pressure gradient (three studies with follow-up period of 3–5 months), deceleration time (three studies with follow-up period of 22 weeks to 1 year), E/A ratio (three studies with follow-up period of 3–5 months) or E/e’ ratio (four studies with follow-up period of 22 weeks to 1.6 years (table 4).

Other descriptive syntheses

The effect of vasodilator (nitroprusside) infusions in patients with severe AS was only assessed in small uncontrolled observational studies.50 68 72 74 75 These studies suggest that nitroprusside can improve cardiac function by reducing afterload and LV filling pressures, and by increasing the cardiac index and stroke volume index in low-flow AS. No adverse effects were reported in patients receiving nitroprusside infusions. As such, nitroprusside can be a safe and effective bridge to AVR or long-term oral vasodilator treatment, however, patients should be monitored closely due to the potential risks of chronic, persistent vasodilation.

Safety

AHT is generally well tolerated and safe. Our meta-analysis found a statistically significant reduction in mortality when patients were treated with RAASi or when AHT was used post-AVR. A retrospective study in patients receiving a transcatheter AVR reported that BB was an independent predictor of survival and the HR in the absence of BB was 36.3 (95% CI 4.1 to 325.2, p=0.001).51 Two other studies reported that RAASi or BB did not affect survival.61 65 In contrast, the use of CCB was associated with shorter exercise time and significantly reduced survival.73 An observational, single blinded study, with randomisation of the order of drug withdrawal, demonstrated clinical benefit of ACE inhibitors through significant reduction in systolic blood pressure, increase in mean pressure gradient and reduced LV stroke work.66 Similarly, another non-controlled study showed benefit with use of captopril in patients with critical AS and heart failure through reduction in systemic vascular resistance and stroke volume, and increase in cardiac output and cardiac index.70

Discussion

Clinical outcomes

Based on pooled effect estimates from all relevant studies, this systematic review and meta-analysis provides some evidence that AHT is safe and RAASi was clinically beneficial for patients with moderate to severe AS. We demonstrated significant improvement in survival or reduction in mortality in patients receiving RAASi, although heterogeneity was substantial across studies. Subgroup analyses by drug class and AVR was conducted to investigate the heterogeneous results, however, substantial heterogeneity persisted, which may reflect more systematic nature of the studies, such as variability in study design, dose and duration of AHT, and length of follow-up across studies. There were some discrepant results in studies when interpreted in isolation as some studies failed to demonstrate significant outcomes,42 61 63 65 while others were associated with improved outcomes.

In contrast to our findings, a previous systematic review assessing the effects of renin–angiotensin system inhibitors found no significant difference in mortality, but included patients with any stage of AS severity.76 The present study, however, underscores the place of hypertension as an independent predictor of adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients with AS.20 77 Contrary to the clinical expectations of many physicians, our data suggest that the benefit of RAASi may be most substantial in those with critical or severe AS with haemodynamic compromise.

Post-AVR

Guidelines recommend AVR in patients with severe symptomatic AS or LV dysfunction.31 32 LV hypertrophy post-AVR has been associated with poorer postprocedural outcomes.78 79 In patients with surgical or transcatheter AVR, we found a significant survival benefit, and reduced risk of acute kidney injury in patients receiving AHT compared with controls or placebo, despite heterogeneity. There were no significant differences in the incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation, stroke or transient ischaemic attack, need for a permanent pacemaker or readmission rates. Current clinical trials such as the randomised multicentre phase II ARISTOTE trial assessing the effects of valsartan, an angiotensin-II receptor blocker, aim to clarify which AHT is most beneficial in moderate or severe AS.80 There is also evidence to suggest that systolic blood pressure increase significantly post-TAVI, which was shown to be associated with increase in stroke volume and cardiac output.81 There is conflicting evidence to suggest if this improves or worsens clinical outcomes. A prospective study found that patients with increased blood pressure was associated with lower risk of worsening heart failure, myocardial infarction, stroke or recurrent hospitalisation compared with stable blood pressure (53% vs 83%, p<0.01).81 However, another study found that persistent hypertension after TAVI was associated with reduced symptomatic improvement (increase NYHA functional class and reduced 6 min walk test).82

Surrogate markers

Interestingly, there was no favourable reduction in LV mass index, systolic or diastolic blood pressures in patients with AHT, compared with controls or placebo. Other haemodynamic or echocardiographic parameters did not differ significantly between those who were prescribed AHT and those who were not, however, pooled data were limited by substantial heterogeneity, variability in measurements, differences in follow-up periods and patient characteristics. Evidence was also mostly derived from non-randomised trials and randomised trials with small sample sizes.

The results also show that different AHT have varying impact on LV function and clinical outcomes.54 55 60 83 84 Some authors attribute the benefits of AHT in this context to reduction in haemodynamic stress and myocardial ischaemia and to reduction in heart failure symptoms.55 85 Haemodynamic factors and neurohormonal systems such as the RAAS are implicated in LV hypertrophy and myocardial fibrosis in AS.86 87 There remains a need for future studies to establish an appropriate blood pressure target and to clarify the optimum dosing, initiation time frame and duration of treatment with AHT for patients with moderate or severe AS. Most studies included in our meta-analysis assessed the effects of RAASi. There are insufficient data to compare clinical outcomes between drug classes and to evaluate whether a particular drug class is clinically superior in patients with moderate or severe AS.

Conclusion

This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to show that RAASi appears to have a clinical benefit in patients with moderate or severe AS, but is limited by the small number of studies and substantial heterogeneity. The included randomised trials were generally of good quality, but not all RCTs reported all outcomes relevant to this review and only one study reported all-cause mortality.52 Nevertheless, improved survival compared with control/placebo was demonstrated in these patients, especially in those who had a transcatheter AVR. Further studies with clear inclusion and exclusion criteria, longer term follow-up and reporting of clinical outcomes are needed before stronger policies are recommended for AHT use in patients with moderate or severe AS. RCTs with an appropriate sample size are required in order to determine which AHT is optimum in patients with moderate or severe AS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Evelyn Hutcheon of the Western Health Library for assistance with literature search strategies.

Footnotes

Contributors: TM conceived this review. JS and TM designed the protocol. JS and EC performed the literature search, study selection, data extraction and critical appraisal of the articles. Conflicts were resolved with discussion with TM. JS and EC synthesised the data. JS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors (JS, EC, CN and TM) revised the paper and approved the final version. TM is the study guarantor, responsible for overall content of the manuscript.

Funding: This work has been supported in part by a Partnership grant (1149692) from the National Health and Medical Research Council, Canberra. JS was supported by scholarships from the National Heart Foundation of Australia (ID: 102578), National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (ID: 1191044).

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: support from Australian Government Research Training Program (Research Scholarship) for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2019 update: a report from the American heart association. Circulation 2019;139:e56–28. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Badiani S, van Zalen J, Treibel TA, et al. Aortic stenosis, a left ventricular disease: insights from advanced imaging. Curr Cardiol Rep 2016;18:80. 10.1007/s11886-016-0753-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ito S, Miranda WR, Nkomo VT, et al. Reduced left ventricular ejection fraction in patients with aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:1313–21. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.01.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grossman W, Jones D, McLaurin LP. Wall stress and patterns of hypertrophy in the human left ventricle. J Clin Invest 1975;56:56–64. 10.1172/JCI108079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carabello BA, Paulus WJ. Aortic stenosis. Lancet 2009;373:956–66. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60211-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gould KL, Carabello BA. Why angina in aortic stenosis with normal coronary arteriograms? Circulation 2003;107:3121–3. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000074243.02378.80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levy D. Clinical significance of left ventricular hypertrophy: insights from the Framingham study. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 1991;17:S1–6. 10.1097/00005344-199117002-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaasch WH, Zile MR, Hoshino PK, et al. Tolerance of the hypertrophic heart to ischemia. Studies in compensated and failing dog hearts with pressure overload hypertrophy. Circulation 1990;81:1644–53. 10.1161/01.CIR.81.5.1644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zile MR, Brutsaert DL. New concepts in diastolic dysfunction and diastolic heart failure: Part II: causal mechanisms and treatment. Circulation 2002;105:1503–8. 10.1161/hc1202.105290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rajappan K, Rimoldi OE, Camici PG, et al. Functional changes in coronary microcirculation after valve replacement in patients with aortic stenosis. Circulation 2003;107:3170–5. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000074211.28917.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kupari M, Turto H, Lommi J. Left ventricular hypertrophy in aortic valve stenosis: preventive or promotive of systolic dysfunction and heart failure? Eur Heart J 2005;26:1790–6. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwartz LS, Goldfischer J, Sprague GJ, et al. Syncope and sudden death in aortic stenosis. Am J Cardiol 1969;23:647–58. 10.1016/0002-9149(69)90025-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Omran H, Fehske W, Rabahieh R, et al. Relation between symptoms and profiles of coronary artery blood flow velocities in patients with aortic valve stenosis: a study using transoesophageal doppler echocardiography. Heart 1996;75:377–83. 10.1136/hrt.75.4.377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Julius BK, Spillmann M, Vassalli G, et al. Angina pectoris in patients with aortic stenosis and normal coronary arteries. mechanisms and pathophysiological concepts. Circulation 1997;95:892–8. 10.1161/01.cir.95.4.892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gould KL. Why angina pectoris in aortic stenosis. Circulation 1997;95:790–2. 10.1161/01.CIR.95.4.790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faggiano P, Rusconi C, Sabatini T, et al. Congestive heart failure in patients with valvular aortic stenosis. A clinical and echocardiographic Doppler study. Cardiology 1995;86:120–9. 10.1159/000176853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pellikka PA, Sarano ME, Nishimura RA, et al. Outcome of 622 adults with asymptomatic, hemodynamically significant aortic stenosis during prolonged follow-up. Circulation 2005;111:3290–5. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.495903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rossi A, Tomaino M, Golia G, et al. Echocardiographic prediction of clinical outcome in medically treated patients with aortic stenosis. Am Heart J 2000;140:766–71. 10.1067/mhj.2000.111106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hueb JC, Vicentini JTR, Roscani MG, et al. Impact of hypertension on ventricular remodeling in patients with aortic stenosis. Arq Bras Cardiol 2011;97:254–9. 10.1590/s0066-782x2011005000081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rieck ÅE, Cramariuc D, Boman K, et al. Hypertension in aortic stenosis: implications for left ventricular structure and cardiovascular events. Hypertension 2012;60:90–7. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.194878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eleid MF, Nishimura RA, Sorajja P, et al. Systemic hypertension in low-gradient severe aortic stenosis with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation 2013;128:1349–53. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.003071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carabello BA, Paulus WJ. Aortic stenosis. Lancet 2009;373:956–66. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60211-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lindman BR, Otto CM. Time to treat hypertension in patients with aortic stenosis. Circulation 2013;128:1281–3. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodés-Cabau J, Webb JG, Cheung A, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation for the treatment of severe symptomatic aortic stenosis in patients at very high or prohibitive surgical risk: acute and late outcomes of the multicenter Canadian experience. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:1080–90. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bennett JE, Stevens GA, Mathers CD, et al. Ncd countdown 2030: worldwide trends in non-communicable disease mortality and progress towards sustainable development goal target 3.4. Lancet 2018;392:1072–88. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31992-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gulland A. Global life expectancy increases by five years. BMJ 2016;353:i2883. 10.1136/bmj.i2883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J, Kinfu Y. Impact of socioeconomic and risk factors on cardiovascular disease and type II diabetes in Australia: comparison of results from longitudinal and cross-sectional designs. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010215. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Antonini-Canterin F, Huang G, Cervesato E, et al. Symptomatic aortic stenosis: does systemic hypertension play an additional role? Hypertension 2003;41:1268–72. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000070029.30058.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jolobe OM. Systolic hypertension is also the neglected stepsister of aortic stenosis. Am J Med 2008;121:e21. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.03.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herrmann S, Störk S, Niemann M, et al. Low-gradient aortic valve stenosis myocardial fibrosis and its influence on function and outcome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:402–12. 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baumgartner H, Falk V, Bax JJ, et al. 2017 ESC/EACTS guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J 2017;38:2739–91. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: executive summary: a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:2438–88. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.02.537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morgan HE, Baker KM. Cardiac hypertrophy. mechanical, neural, and endocrine dependence. Circulation 1991;83:13–25. 10.1161/01.CIR.83.1.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bregagnollo EA, Okoshi K, Bregagnollo IF, et al. [Effects of the prolonged inhibition of the angiotensin-converting enzyme on the morphological and functional characteristics of left ventricular hypertrophy in rats with persistent pressure overload]. Arq Bras Cardiol 2005;84:225–32. 10.1590/s0066-782x2005000300006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (moose) group. JAMA 2000;283:2008–12. 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. 10.10.2 identifying and measuring heterogeneity. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 60 (updated July 2019): cochrane, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simonsohn U, Nelson LD, Simmons JP. And effect size: correcting for publication bias using only significant results. perspectives on psychological science. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2014: 666–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.R Core Team R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okoh A, Singh S, Aggarwal S, et al. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors are associated with reno-protective effects in aging patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2019;93:S229–30. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pino JE, Ramos Tuarez F, Torres P, et al. Neuroendocrine inhibition in patients with heart failure and severe aortic stenosis undergoing TAVI. Europ J Heart Fail 2019;21:244. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alrifai A, Sundaravel S, Grajeda E, et al. The impact of beta blockers on transcatheter aortic valve replacement outcomes. JACC: Cardiovas Intervent 2018;11:S48. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rodriguez-Gabella T, Catalá P, Muñoz-García AJ, et al. Renin-angiotensin system inhibition following transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;74:631–41. 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.05.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Younis A, Orvin K, Nof E, et al. The effect of periprocedural beta blocker withdrawal on arrhythmic risk following transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2019;93:1361–6. 10.1002/ccd.28017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Inohara T, Manandhar P, Kosinski AS, et al. Association of renin-angiotensin inhibitor treatment with mortality and heart failure readmission in patients with transcatheter aortic valve replacement. JAMA 2018;320:2231–41. 10.1001/jama.2018.18077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Magne J, Guinot B, Le Guyader A, et al. Relation between renin-angiotensin system blockers and survival following isolated aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis. Am J Cardiol 2018;121:455–60. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ochiai T, Saito S, Yamanaka F, et al. Renin–angiotensin system blockade therapy after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Heart 2018;104:644–51. 10.1136/heartjnl-2017-311738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goh SS-N, Sia C-H, Ngiam NJ, et al. Effect of renin-angiotensin blockers on left ventricular remodeling in severe aortic stenosis. Am J Cardiol 2017;119:1839–45. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.02.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hansson NH, Sörensen J, Harms HJ, et al. Metoprolol reduces hemodynamic and metabolic overload in asymptomatic aortic valve stenosis patients: a randomized trial. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2017;10:10. 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.117.006557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lloyd JW, Nishimura RA, Borlaug BA, et al. Hemodynamic response to nitroprusside in patients with Low-Gradient severe aortic stenosis and preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:1339–48. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.07.736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Amsallem M, Bouleti C, Himbert D, et al. 0093: early and late outcomes after trans-catheter aortic valve implantation in patients with previous thoracic irradiation. Arch Cardiovas Dis Suppl 2016;8:58 10.1016/S1878-6480(16)30171-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barbanti M, Gulino S, Capranzano P, et al. Acute kidney injury with the RenalGuard system in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement: the PROTECT-TAVI trial (prophylactic effecT of Frusemide-induCed diuresis with matched isotonic intravenous hydraTion in transcatheter aortic valve implantation). JACC: Cardiovas Interven 2015;8:1595–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bull S, Loudon M, Francis JM, et al. A prospective, double-blind, randomized controlled trial of the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor ramipril in aortic stenosis (RIAS trial). Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2015;16:834–41. 10.1093/ehjci/jev043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Helske-Suihko S, Laine M, Lommi J, et al. Is blockade of the renin-angiotensin system able to reverse the structural and functional remodeling of the left ventricle in severe aortic stenosis? J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2015;65:233–40. 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rossi A, Temporelli PL, Cicoira M, et al. Beta-blockers can improve survival in medically-treated patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis. Int J Cardiol 2015;190:15–17. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.04.083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dalsgaard M, Iversen K, Kjaergaard J, et al. Short-term hemodynamic effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition in patients with severe aortic stenosis: a placebo-controlled, randomized study. Am Heart J 2014;167:226–34. 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goel SS, Aksoy O, Houghtaling P, et al. TCT-750 role of renin-angiotensin system blockade therapy following aortic valve replacement for severe aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64:B219 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.07.822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dahl JS, Videbæk L, Poulsen MK, et al. Prevention of atrial fibrillation in patients with aortic valve stenosis with candesartan treatment after aortic valve replacement. Int J Cardiol 2013;165:242–6. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.08.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dahl JS, Videbaek L, Poulsen MK, et al. Effect of candesartan treatment on left ventricular remodeling after aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis. Am J Cardiol 2010;106:713–9. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.04.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nadir MA, Wei L, Elder DHJ, et al. Impact of renin-angiotensin system blockade therapy on outcome in aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:570–6. 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.01.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rosenhek R, Zilberszac R, Schemper M, et al. Natural history of very severe aortic stenosis. Circulation 2010;121:151–6. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.894170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tatu A, Broasca M, Munteanu I, et al. The efficacy of telmisartan and carvedilol in the left ventricle systolic and diastolic dysfunction recovery in patients with aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis. Interact Cardiovas Thor Surg 2009;8:S102–3. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stewart RAH, Kerr AJ, Cowan BR, et al. A randomized trial of the aldosterone-receptor antagonist eplerenone in asymptomatic moderate-severe aortic stenosis. Am Heart J 2008;156:348–55. 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pai RG, Kapoor N, Bansal RC, et al. Malignant natural history of asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis: benefit of aortic valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg 2006;82:2116–22. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.07.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Varadarajan P, Kapoor N, Bansal RC, et al. Clinical profile and natural history of 453 nonsurgically managed patients with severe aortic stenosis. Ann Thorac Surg 2006;82:2111–5. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.07.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jiménez-Candil J, Bermejo J, Yotti R, et al. Effects of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in hypertensive patients with aortic valve stenosis: a drug withdrawal study. Heart 2005;91:1311–8. 10.1136/hrt.2004.047233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Khot UN, Novaro GM, Popović ZB, et al. Nitroprusside in critically ill patients with left ventricular dysfunction and aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1756–63. 10.1056/NEJMoa022021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Popović ZB, Khot UN, Novaro GM, et al. Effects of sodium nitroprusside in aortic stenosis associated with severe heart failure: pressure-volume loop analysis using a numerical model. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2005;288:H416–23. 10.1152/ajpheart.00615.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chockalingam A, Venkatesan S, Subramaniam T, et al. Safety and efficacy of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in symptomatic severe aortic stenosis: symptomatic cardiac obstruction–pilot study of enalapril in aortic stenosis (SCOPE-AS). Am Heart J 2004;147:E19. 10.1016/j.ahj.2003.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Martínez Sánchez C, Henne O, Arceo A, et al. [Hemodynamic effects of oral captopril in patients with critical aortic stenosis]. Arch Inst Cardiol Mex 1996;66:322–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Friedrich SP, Lorell BH, Rousseau MF, et al. Intracardiac angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition improves diastolic function in patients with left ventricular hypertrophy due to aortic stenosis. Circulation 1994;90:2761–71. 10.1161/01.CIR.90.6.2761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Awan NA, DeMaria AN, Miller RR, et al. Beneficial effects of nitroprusside administration on left ventricular dysfunction and myocardial ischemia in severe aortic stenosis. Am Heart J 1981;101:386–94. 10.1016/0002-8703(81)90126-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Saeed S, Mancia G, Rajani R, et al. Antihypertensive treatment with calcium channel blockers in patients with moderate or severe aortic stenosis: relationship with all-cause mortality. Int J Cardiol 2020;298:122–5. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Eleid M, Nishimura R, Borlaug B, et al. Acute hemodynamic effects of sodium nitroprusside in low gradient severe aortic stenosis with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:E2114 10.1016/S0735-1097(13)62114-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Khot UN, Novaro GM, Popović ZB, et al. Nitroprusside in critically ill patients with left ventricular dysfunction and aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2003;348:1756–63. 10.1056/NEJMoa022021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Andersson C, Abdulla J. Is the use of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors in patients with aortic valve stenosis safe and of prognostic benefit? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother 2017;3:21–7. 10.1093/ehjcvp/pvw027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Capoulade R, Clavel M-A, Mathieu P, et al. Impact of hypertension and renin-angiotensin system inhibitors in aortic stenosis. Eur J Clin Invest 2013;43:1262–72. 10.1111/eci.12169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Orsinell DA, Aurigemma GP, Battista S, et al. Left ventricular hypertrophy and mortality after aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 1993;22:1679–83. 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90595-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zybach-Benz RE, Aeschbacher BC, Schwerzmann M. Impact of left ventricular hypertrophy late after aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Int J Cardiol 2006;109:41–7. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.05.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Efficacy of angiotensin receptor blocker following aortIc valve intervention for aortIc stenosis: a randomized mulTi-cEntric double-blind phase II study, 2017. Available: Https://clinicaltrialsgov/show/nct03315832

- 81.Perlman GY, Loncar S, Pollak A, et al. Post-procedural hypertension following transcatheter aortic valve implantation: incidence and clinical significance. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2013;6:472–8. 10.1016/j.jcin.2012.12.124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Reinthaler M, Stähli BE, Gopalamurugan AB, et al. Post-procedural arterial hypertension: implications for clinical outcome after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. J Heart Valve Dis 2014;23:675–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Routledge HC, Ong KR, Townend JN. Left ventricular hypertrophy and aortic stenosis: a possible role for ACE inhibition? British Journal of Cardiology 2003;10:214–6. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bang CN, Greve AM, Køber L, et al. Renin–angiotensin system inhibition is not associated with increased sudden cardiac death, cardiovascular mortality or all-cause mortality in patients with aortic stenosis. Int J Cardiol 2014;175:492–8. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kang TS, Park S. Antihypertensive treatment in severe aortic stenosis. J Cardiovasc Imaging 2018;26:45–53. 10.4250/jcvi.2018.26.e9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Grimm D, Huber M, Jabusch HC, et al. Extracellular matrix proteins in cardiac fibroblasts derived from rat hearts with chronic pressure overload: effects of beta-receptor blockade. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2001;33:487–501. 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Katsi V, Georgiopoulos G, Oikonomou D, et al. Aortic stenosis, aortic regurgitation and arterial hypertension. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 2019;17:180–90. 10.2174/1570161116666180101165306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-036960supp001.pdf (455.8KB, pdf)