Abstract

Objective

This brief report presents contemporary national estimates of the spatial distance between residences of parents and adult children in the United States, including distance to one’s nearest parent and/or adult child and whether one lives near all of their parents and adult children.

Background

The most recent national estimates of parent-child spatial proximity come from data for the early 1990s. Moreover, research has rarely assessed spatial clustering of all parents and adult children.

Method

Data are from the 2013 Panel Study of Income Dynamics on residential locations of adults 25 and older and each of their parents and adult children. Two measures of spatial proximity were estimated: distance to nearest parent or adult child, and the share of adults who have all parents and/or adult children living nearby. Sociodemographic and geographic differences were examined for both measures.

Results

Among adults with at least one living parent or adult child, a significant majority (74.8%) had their nearest parent or adult child within 30 miles, and about one third (35.5%) had all parents and adult children living that close. Spatial proximity differed substantially among sociodemographic groups, with those who were disadvantaged more likely to have their parents or adult children nearby. In most cases, sociodemographic disparities were much higher when spatial proximity was measured by proximity to all parents and all adult children instead of to nearest parent or nearest adult child.

Conclusion

Disparities in having all parents and/or adult children nearby may be a result of family solidarity and also may affect family solidarity. This report sets the stage for new investigations of the spatial dimension of family cohesion.

Keywords: Families, Geographic proximity, Intergenerational relations, Living arrangements, Disparities, Panel Study of Income Dynamics

Introduction

Family members help each other in various ways including caring for young children, coping with physical or cognitive limitations, providing emotional support, and completing routine tasks (Compton & Pollak, 2014; Houtven & Norton, 2004; McGarry & Schoeni, 1995; Sasso & Johnson, 2002; Sloan, Zhang, & Wang, 2002; Stone, Cafferata, & Sangl, 1987). Close proximity of family members is strongly positively associated with intergenerational support including help provided to aging parents and relatives (Joseph & Hallman, 1998; Litwak & Kulis, 1987; Rossi & Rossi, 1990), assistance with household chores (Mulder & van der Meer, 2009), and the frequency of intergenerational contact (Grundy & Shelton, 2001; Hank, 2007; Kalmijn, 2006; Lawton, Silverstein, & Bengtson, 1994; Rossi & Rossi, 1990; Spitze & Logan, 1990). Proximity is also associated with health care utilization and labor market outcomes. Having an adult child living nearby reduces nursing home entry and the use of formal care following a decline in health (Choi, Schoeni, Langa, & Heisler, 2014), and having parents living nearby improves labor market outcomes for both men and women (Coate, 2013; Coate, Krolikowski, & Zabek, 2017; Compton & Pollak, 2014). Finally, migration decisions are also influenced by the location of relatives (Dawkins, 2006; Longino, 2008; Massey & Espinosa, 1997; Spilimbergo & Ubeda, 2004; Spring, Ackert, Crowder, & South, 2017; Zorlu, 2009).

This brief report contributes to the literature on family proximity in several ways. First, we update previous national estimates of family proximity in the United States. The most recent study that provides national estimates of family proximity is Compton & Pollak (2015) which used the National Survey of Families and Households from the 1990s. We provide contemporary estimates of the proximity to the nearest parent, nearest adult child, nearest parent or adult child, and, nearest parent and adult child for adults of all ages using data from 2013. By examining adults of all ages, this approach contrasts with most previous research that examines proximity of older adults to their children or proximity of younger adults to their parents. Our approach also recognizes that many families have three generations of adults for whom measures of kin proximity should consider relatives both up and down their family tree simultaneously.

Second, we also provide a more holistic view of family proximity by identifying adults who have all of their parents and/or adult children living nearby. Having all parents and/or adult children nearby may enhance solidarity or potential for family help, for instance if children take turns helping aging parents or each adult child helps instead of one designated caregiver, or if both own parents and in-laws provide childcare. At the same time, when individuals live in the same geographic area as their parents and/or adult children they share the vulnerabilities of local labor market declines, strained housing markets, and natural disasters. Our attention to the co-location of these family members addresses a major gap in past research (Agree, 2018).

Third, we report differences in spatial proximity by five key sociodemographic and geographic factors: education, race, marital status, metropolitan residence, and region. Prior research has found differences in distance to nearest parent or adult child by these factors. We determine whether similar differences exist when proximity to parents and/or children is measured by having all parents and/or adult children living nearby.

Taken together, this report on contemporary estimates of family proximity sets the stage for future work to examine the causes and effects of spatial proximity of families in the United States.

The next section of this report briefly summarizes past research on intergenerational proximity. Section 3 describes the sample, measures of proximity, and methods. Sections 4 and 5 report estimates of proximity and how proximity varies by key sociodemographic characteristics. The last section summarizes major findings, discusses limitations, and considers the implications of the study.

Prior Studies

Family scholars have a long-standing interest in the proximity of kin, which was motivated by debates about nuclear family isolation from extended kin and the effects of industrialization and urbanization on family cohesion (Litwak, 1960a, 1960b; Parsons, 1943). A large literature examines coresidence, mainly focusing on coresidence of parents and adult children (Wolf & Soldo, 1988; Costa, 1999; Choi, 2003; Wiemers, Slanchev, McGarry & Hotz, 2017), with a much smaller body of evidence on spatial distance beyond shared housing. Studies in general differ in whether they adopt the point of view of a parent or an adult child, age restrictions (e.g., focusing on older or younger adults), and the marital and health status of the focal person.

Previous national estimates from the parent’s perspective indicated that 60–75% of older parents lived with or close to (i.e., within 25 miles or 30 minutes of) their nearest child (Crimmins & Ingegneri, 1990; Hoyert, 1991; Shanas, 1984), and very few had their nearest child living more than several hundred miles away (Lin & Rogerson, 1995). Analyzing data from 1980 to 2013, Spring et al. (2017) showed that a quarter of adults in their fifties lived within a mile of at least one non-coresident child. Between the early 1960s and early 1980s, the percentages living near but not with a child rose while coresidence declined (Shanas, 1982). A more recent study finds that coresidence has increased in the recent period (Kahn, Goldscheider, & García-Manglano, 2013).

From the adult child’s perspective, data from the early 1990s indicated that most lived fairly close to their parents. The median distance to mother was just 8 miles, 5 miles, and 20 miles for unmarried women, unmarried men, and married couples, respectively (Compton & Pollak, 2015). At the same time, for unmarried women, unmarried men, and married couples, one-quarter were more than 150 miles, 67 miles, and 300 miles from their mothers, respectively (Compton & Pollak, 2015). Among young adults under age 30, about one third lived within a mile of at least one non-coresident parent (Spring et al., 2017). Coresidence of young adults with their parents declined from 1930–1970, but has been increasing since then (Glick & Lin, 1986; Goldscheider & DaVanzo, 1989, 1985; Matsudaira, 2016), particularly for young adults in their 20s. By 2011, 22.7% of men and 18.3% of women age 28 were living with parents (Matsudaira, 2016).

U.S. family scholars have paid little attention to the geographic dispersion of all members of a family since the 1960s. Adams’ (1968) influential study of Kinship in an Urban Setting examined the percentages of total kin (parents, siblings, grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins) living nearby for White married couples in Greensboro, North Carolina. Klatzky (1972) used data from a 1965 national sample to describe the geographic distance of married men to other male kin, and examined how the proximity of other kin was associated with contact with fathers or other family members. Although these early U.S. studies set the stage for recent research that examines the effects of the location of kin on residential mobility, few studies approached the question of the geographic dispersion of parents and adult children holistically focusing instead on a single parent/child or the nearest parent/child.

Some studies take a more holistic orientation but for a restricted number of family members or specific family sizes. For instance, Dykstra et al. (2006) described average distances between types of kin (a parent, sibling, offspring) for a sample of adults in the Netherlands, but they have information about only one parent (offspring). Konrad et al. (2002) used German data to describe the relative proximity to middle-aged and older parents of first- and second-born children in two-child families to examine whether older siblings strategically move farther away from parents to limit caregiving for parents in older age.

Within the United States, Compton and Pollak (2015) described the distance of married couples to both the husband’s and wife’s mother. More recently, Spring et al. (2017) examined proximity to a wide array of kin (parents, adult children, siblings, and other family members) to assess the impact of family proximity on choices about residential mobility within metropolitan areas. They used data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) over the period 1980–2013, but considered only respondents who did not move across metropolitan areas between observations and proximity to family members who were themselves living in households interviewed by the PSID in the same year. As we describe below, the PSID included a module in 2013 that collected information, including location, for all parents, parents-in-law, and adult children, regardless of whether they lived in a household interviewed by PSID, to expand significantly the PSID’s family coverage. We use the expanded coverage provided by the 2013 module to provide unique, contemporary information about the prevalence of co-location among individuals and their parents and/or adult children. The augmented PSID data now allow an assessment of how common it is to have parents and adult offspring nearby for a representative sample of adults living in the United States.

Prior studies of the United States and other countries that examined proximity beyond coresidence found that adults with lower education were more likely to live close to their parents and other family members (Chan & Ermisch, 2015a, 2015b; Choi, Schoeni, Langa, & Heisler, 2015; Clark & Wolf, 1992; Compton & Pollak, 2015; Garasky, 2002; Kalmijn, 2006; Lauterbach & Pillemer, 2001; Leopold, Geissler, & Pink, 2012; Malmberg & Pettersson, 2008; Rogerson, Weng, & Lin, 1993; Spring et al., 2017). There also were differences in proximity to parents by race, with Blacks living closer to their parents than Whites (Bianchi, McGarry, & Seltzer, 2010; Compton & Pollak, 2015; Spring et al., 2017). Compared to unmarried (adult) children, studies found that married children were less likely to live with their mother, but they were no less likely to live near their mother relative to living farther away (Bianchi et al., 2010; Chan & Ermisch, 2015b; Compton & Pollak, 2015). In general, the less urban a parent’s municipality of residence, the farther away parents and children lived from each other (Lee, Dwyer, & Coward, 1990; van der Pers & Mulder, 2013), but adult children in more rural areas lived closer to their parents than adult children who lived in more urban areas (van der Pers & Mulder, 2013). U.S. parents and children live closest to one another in the Northeast (Lin & Rogerson, 1995; Rogerson et al., 1993).

Data, Measures, and Methods

Data and Measures

We used the Rosters and Transfers Module (R & T) data as well as the main interview data of the 2013 PSID. The 2013 R & T data provide, for a national sample of household heads and spouses, the locations of each biological/ adopted adult child and each biological/ adoptive parent (Schoeni, Bianchi, Hotz, Seltzer, & Wiemers, 2015). Because location of parents and adult children was collected for both the head and spouse, it included location for adult stepchildren, stepparents, and parents-in-law associated with current spouses. The inclusion of both parents and parents-in-law, who would not normally be observed in the PSID genealogical design, is an advantage of the 2013 R & T data for describing proximity of parents and children.

The unit of analysis is adults 25 and older (i.e., PSID heads and spouses ages 25 and older). We use the term “spouse” to refer to what PSID calls wife/”wife,” where “wife” is a female cohabiting partner who has lived with the PSID head for at least one year. For each adult, we examined proximity to biological/ adoptive parents and spouse’s (if present) biological/ adoptive parents (henceforth called “parents”), and to biological/ adopted and stepchildren who are ages 25 and older (henceforth called “adult children”). We included in our sample only adults who have a living relative of the given type (e.g., parent or adult child), which is determined from the 2013 rosters of parents and adult children.

Distance from the focal person to each parent and adult child was determined using the data from the R & T module and the PSID household roster in the main interview. The household roster was used to determine which parents and adult children live in the same household as the focal person. For PSID R & T, city/town/village and state of residence of each living parent and adult child in the United States were collected and used by PSID staff to code the Census “place” each parent and adult child lived, which is the narrowest definition of location possible based on city and state. The Census place of the focal person is based on their address. A Census place is an administrative unit recognized by the U.S. Census Bureau. It can be a city, borough, town or village that is a legally incorporated entity with a fixed set of boundaries. A Census place also can be a community or concentration of population that is identifiable by name but is not located within an incorporated area and may or may not have any government. The location of parents and adult children who live outside of the United States is coded by PSID staff as living abroad (i.e., US territory or foreign country).

We used this information available to researchers in a restricted use data file to determine whether the parent or adult child lived in the same Census place as the focal person and, if not, the distance in miles between them based on the latitude and longitude of the centroid of the Census place using the great-circle distance formula. We examined the following distance categories: living in the same household (“coresident”); in the United States and <30 miles or in the same place, but not in the same household (“close”); and ≥500 miles within the United States (“very far”). Less than thirty miles was chosen because a number of prior studies used this cut point (Compton & Pollak, 2015; Lin & Rogerson, 1995; Rogerson et al., 1993), and because in most locations 30 miles could be traveled easily for a part-day visit. Furthermore, few Census places contain two locations where the distance between the locations is more than 30 miles. For example, in the Census places for the locations in which the sample we analyzed lived, the 75th percentile of the distribution of square miles of the Census place was 16.8. We chose the cut point for “very far” so that a meaningful share of the total sample, roughly 5–10%, was in that category. Results from preliminary analyses including categories of intermediate distance and having a parent living abroad indicated that the three categories we use capture well most subgroup differences.

Methods

We describe the spatial distance between persons 25 and older and their parents, and between persons 25 and older and their adult children based on two measures of proximity. First, we report the distance to the nearest such relative, that is, nearest parent, nearest adult child, and nearest parent or adult child. The second measure indicates the proportion of adults 25 and older who have all of their parents, all of their adult children, or all parents and adult children living within a given distance.

When we estimated distance to the nearest parent and/or adult child, we included all adults 25 and older who have non-missing location data for themselves and for at least one relative of the specified type (i.e., parents, adult children, or both). When we estimated the proportion of adults who have all parents and/or adult children living within a given distance, we included only those adults who have non-missing location data for themselves and all relatives of the specified type (i.e., parents, adult children, or both). The less restrictive elimination of missing data for the measure of nearest parent and/or child implies slightly different sample sizes between the two measures for a given type of relative.

The rate of missing data on locations was low, ranging from 1.3% for adults with a parent or an adult child to 2.7% for adults with at least one parent and at least one child. Among adults with a living parent or adult child, 7.9% had missing data for at least one parent or adult child. All analyses used the PSID cross-sectional individual sample weight for 2013, adjusted for immigration since 1997 (when PSID refreshed its sample for immigration) and for the elimination of a select set of families from the PSID in 1997 (Freedman & Schoeni, 2016).

We considered adults in their potential dual roles as children to their parents and as parents to their children by estimating spatial proximity to either one’s parents or adult children. Accordingly, all measures were provided from the perspective of adult children (i.e., where the focal person was an adult who had a living parent), the perspective of parents (i.e., where the focal person was a parent of an adult child), the perspective of adults who were either children or parents of adult children (i.e., where the focal person had a living parent or was the parent of an adult child), and the perspective of adults who were both children and parents to adult children (i.e., where the focal person had a living parent and was her/himself the parent of an adult child).

The samples used in the tabulations below vary based on whether we examined individuals’ proximity to a parent or an adult child or both parents and adult children and on whether we examined proximity to the nearest or to all such relatives. There were 12,608 individuals aged 25 or older who were PSID heads or spouses in 2013 of which 9,844 had at least one living parent (biological/adoptive, in-law); 9,709 had non-missing information on the proximity to at least one parent, and 9,286 had non-missing information on the proximity to all living parents. For analyses of individuals’ proximity to adult children, we began with a sample of the 4,956 individuals who had at least one adult child (biological/ adopted, stepchild) who was age 25 or older. Of these, 4,867 had non-missing information on the proximity to at least one adult child, and 4,536 had non-missing proximity information on all living adult children. For analyses of proximity to a parent or adult child, 12,153 adults had at least one living parent or adult child; 12,001 had non-missing information on proximity to at least one parent or adult child; 11,197 had complete information on proximity to all parents and adult children. Proximity in three-generation families required that the sample be restricted to the 2,647 individuals who had both a living parent and an adult child. Of these, 2,575 had non-missing proximity information on at least one parent or adult child; 2,398 had complete proximity information for all parents and adult children.

We also considered how distance between family members varies by education, race, marital status, metropolitan status, and region. We distinguished among focal persons who had fewer than 16 years of schooling versus 16 or more years of schooling; non-Hispanic Black versus non-Hispanic White focal persons (other race/ethnic groups were not examined separately due to limited sample sizes but are included in all other analyses); and, those who were partnered (i.e., married or cohabitating) versus unpartnered. We also examined proximity differences by whether or not the focal person lived in a metropolitan area and by region of the country. Metropolitan areas included all counties in metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs), which were defined based on the U. S. Office of Management and Budget (OMB) standards. We defined region as one of four Census Regions: Northeast, Midwest, South, and West. All of these characteristics were obtained from the main PSID interview. Less than 1% (0.1–0.7%) had missing data attributable to missing values in these sociodemographic or geographic variables.

To assess differences in proximity across sociodemographic groups, we performed t-tests by estimating logistic regressions with a binary outcome for each proximity category. We adopted a standard approach to measuring disparities by comparing the absolute difference relative to a baseline proportion. For instance, we examined the difference in the proportion coresident or living close by among adults with <16 years of schooling and the proportion coresident or living close by among adults with ≥16 years, divided by the latter. We used this approach for each of the sociodemographic and geographic comparisons.

Family Spatial Proximity

Distance to nearest Parent or Adult Child

Table 1, Panel A, reports the distance to the nearest parent and/or adult child. Among adults with a living parent, 5.9% had a parent living with them and 59.8% had their nearest parent living close. Fewer than one in ten (9.2%) had their nearest parent very far away. Among persons with adult children, 19.1% had an adult child living with them, 57.1% had their nearest child living close to them, and 6.6% had their nearest child very far away.

Table 1.

Distance to nearest and to all parents and/or adult children

| Panel A. Distance to nearest parent and/or adult child | ||||

| % of adults who have the nearest parent within a given distance among those who have a living parent | % of adults who have the nearest adult child within a given distance among those with an adult child | % of adults who have the nearest parent and/or adult child within a given distance among those who: |

||

| have a living parent or adult child | have a living parent and adult child | |||

| Unweighted N | 9709 | 4867 | 12001 | 2575 |

| Coresident, % | 5.9 | 19.1 | 13.2 | 22.4 |

| Close, % | 59.8 | 57.1 | 61.6 | 63.6 |

| Coresident or Close, % | 65.7 | 76.2 | 74.8 | 86.0 |

| Very Far, % | 9.2 | 6.6 | 6.8 | 2.8 |

| Panel B. Share (%) of adults who have all parents and/or adult children within a given distance | ||||

| % of adults who have all parents within a given distance among those with a living parent | % of adults who have all adult children within a given distance among those with an adult child | % of adults who have all parents and/or adult children within a given distance among those who: |

||

| have a living parent or adult child | have a living parent and adult child | |||

| Unweighted N | 9286 | 4536 | 11197 | 2398 |

| Coresident, % | 3.2 | 4.7 | 2.8 | |

| Coresident or Close, % | 41.8 | 38.6 | 35.5 | 21.2 |

| Very Far, % | 9.2 | 6.5 | 6.8 | 2.6 |

Notes: Nearest distance is based on the sample of PSID heads and spouses 25 and older who have at least one parent and/or adult child with non-missing distance values. Percent with all parents and/or adult children within a distance is based on the sample of PSID heads and spouses 25 and older for whom all parents and/or adult children of the given type have non-missing distance values. “Parents” include own and spouse’s biological/adoptive parents. “Adult children” include adult biological/adopted and step children. Close = in the United States and less than 30 miles but not coresident; Very far = at least 500 miles and in the United States. Sample weights are applied for all estimates. Shaded cells have a cell count less than 10 and cannot be reported.

Among all adults with a living parent or adult child, 13.2% lived with a parent or adult child, and an additional 61.6% had their nearest parent or adult child living close to them. A substantial minority did not have a parent or adult child nearby; the nearest such relative living in the United States was very far away for 6.8% of adults. For the 21% (estimate not shown in tables) of adults who had at least one living parent and at least one adult child (i.e., there were at least three living adult generations), almost one quarter of them (22.4%) had at least one coresident parent or adult child, another 63.6% had at least one parent or adult child in close proximity. Only 2.8% had their nearest parent or adult child living very far away. Table 1 highlights that having at least one relative within 30 miles (including coresident) was the norm.

Share with All Parents and Adult Children Living Nearby

A substantial share of adults had all of their parents and adult children living nearby, as shown in Panel B of Table 1. Among individuals who had at least one living parent, 41.8% had all parents either coresident or living close to them, and among individuals who had at least one adult child, 38.6% had all adult children coresident or close to them. Among those with a living parent or adult child, 35.5% had all parents and adult children within 30 miles, and among three-generation families, this fraction is 21.2%.

The contrast in estimates of proximity to the nearest parent or child (Table 1, Panel A) versus all parents and children (Table 1, Panel B) suggests a more nuanced pattern of spatial proximity than has been depicted in previous research based on proximity to the nearest kin. Although most adults lived with or close to a parent or adult child, a much smaller percentage had all of their parents or children nearby. The contrast between nearest parent or adult child and having all parents and adult children spatially concentrated was greatest for three-generation families; among adults who had both a parent and adult child alive, 86.0% had at least one relative living with them or close to them, but a smaller but still substantial 21.2% had all such relatives within this distance.

Sociodemographic Variation in Proximity

Table 2 reports differences in proximity by years of schooling, race, and partnership status (whether married/cohabiting or not) of the focal person. Panel A reports the distance to the nearest relative of a given type, and Panel B reports the share of adults with all parents and children living at each distance. Differences across sociodemographic subgroups that are statistically different from each other are denoted by asterisks.

Table 2.

Distance to nearest and to all parents and/or adult children, by sociodemographic characteristics

| Panel A. Distance to nearest parent and/or adult child | ||||||||

| % of adults who have the nearest parent within a given distance among those with a living parent | % of adults who have the nearest adult child within a given distance among those with an adult child | % of adults who have the nearest parent and/or adult child within a given distance among adults who: |

||||||

| have a living parent or adult child | have a living parent and adult child | |||||||

| by Education | <16 | ≥16 | <16 | ≥16 | <16 | ≥16 | <16 | ≥16 |

| Unweighted N | 6450 | 3259 | 3697 | 1170 | 8207 | 3794 | 1940 | 635 |

| Coresident, % | 6.9 | 4.1*** | 20.6 | 14.3*** | 15.5 | 8.2*** | 24.0 | 17.5** |

| Close, % | 64.6 | 50.6*** | 58.8 | 51.7*** | 65.1 | 54.3*** | 64.6 | 60.2 |

| Coresident or Close, % | 71.5 | 54.7*** | 79.4 | 66.0*** | 80.6 | 62.5*** | 88.6 | 77.7*** |

| Very Far, % | 6.1 | 15.1*** | 5.4 | 10.4*** | 4.5 | 11.7*** | 1.6 | 6.5*** |

| by Race | NH-Black | NH-White | NH-Black | NH-White | NH-Black | NH-White | NH-Black | NH-White |

| Unweighted N | 2924 | 5593 | 1528 | 2833 | 3658 | 6928 | 794 | 1498 |

| Coresident, % | 8.4 | 4.8*** | 27.5 | 15.0*** | 19.2 | 10.8*** | 27.8 | 17.3*** |

| Close, % | 68.0 | 61.5*** | 55.5 | 58.7 | 62.3 | 63.7 | 63.7 | 67.6 |

| Coresident or Close, % | 76.4 | 66.3*** | 83.0 | 73.7*** | 81.5 | 74.5*** | 91.5 | 84.9** |

| Very Far, % | 6.0 | 10.1** | 4.0 | 7.1* | 4.1 | 7.2** | 2.4 | |

| by Partnership status | Unpartnered | Partnered | Unpartnered | Partnered | Unpartnered | Partnered | Unpartnered | Partnered |

| Unweighted N | 2591 | 7118 | 1368 | 3499 | 3501 | 8500 | 458 | 2117 |

| Coresident, % | 13.9 | 3.1*** | 22.3 | 17.8** | 19.2 | 10.7*** | 31.2 | 20.7*** |

| Close, % | 50.9 | 62.9*** | 58.5 | 56.5 | 54.5 | 64.7*** | 58.4 | 64.5 |

| Coresident or Close, % | 64.8 | 66.0 | 80.8 | 74.3*** | 73.7 | 75.4 | 89.6 | 85.2 |

| Very Far, % | 11.7 | 8.4*** | 5.5 | 7.1 | 8.3 | 6.1** | 2.9 | |

| Panel B. Share (%) of adults who have all parents and/or adult children within a given distance | ||||||||

| % of adults who have all parents within a given distance among those with a living parent | % of adults who have all adult children within a given distance among those with an adult child | % of adults who have all parents and/or adult children within a given distance among those who: |

||||||

| have a living parent or adult child | have a living parent and adult child | |||||||

| by Education | <16 | ≥16 | <16 | ≥16 | <16 | ≥16 | <16 | ≥16 |

| Unweighted N | 6125 | 3161 | 3407 | 1129 | 7545 | 3652 | 1790 | 608 |

| Coresident, % | 3.8 | 2.0*** | 4.9 | 3.8 | 3.2 | 1.9** | ||

| Coresident or Close, % | 47.5 | 30.9*** | 41.8 | 28.8*** | 39.9 | 26.5*** | 24.7 | 10.6*** |

| Very Far, % | 6.1 | 15.0*** | 5.4 | 10.0*** | 4.4 | 11.6*** | 1.5 | 5.8*** |

| by Race, % | NH-Black | NH-White | NH-Black | NH-White | NH-Black | NH-White | NH-Black | NH-White |

| Unweighted N | 2798 | 5364 | 1412 | 2897 | 3385 | 6533 | 734 | 1425 |

| Coresident, % | 5.2 | 2.8*** | 6.7 | 2.9*** | 5.1 | 2.1*** | ||

| Coresident or Close, % | 56.0 | 42.5*** | 54.5 | 33.7*** | 50.9 | 33.7*** | 42.8 | 18.9*** |

| Very Far, % | 6.0 | 10.2** | 4.3 | 6.9 | 4.1 | 7.2** | 2.4 | |

| by Partnership status | Unpartnered | Partnered | Unpartnered | Partnered | Unpartnered | Partnered | Unpartnered | Partnered |

| Unweighted N | 2520 | 6766 | 1284 | 3252 | 3335 | 7862 | 435 | 1963 |

| Coresident, % | 10.6 | 0.6*** | 5.4 | 4.4 | 7.5 | 0.7*** | ||

| Coresident or Close, % | 57.0 | 36.3*** | 46.6 | 35.2*** | 49.8 | 29.3*** | 35.7 | 18.4*** |

| Very Far, % | 11.7 | 8.4*** | 5.4 | 7.0 | 8.2 | 6.1** | 2.7 | |

Note: Nearest distance is based on the sample of PSID heads and spouses 25 and older who have at least one parent and/or adult child with non-missing distance values. Percent with all parents and/or adult children within a distance is based on the sample of PSID heads and spouses for whom all parents and/or adult children have non-missing distance values. “Parents” include own and spouse’s biological/adoptive parents. “Adult children” include adult biological/adopted and step children. Close = in the United States and less than 30 miles but not coresident; Very far = at least 500 miles and in the United States. Sample weights are applied for all estimates. Shaded cells have a cell count less than 10 and cannot be reported.

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

Several broad themes emerge from the tabulations in Table 2. There were large differences in family proximity by education. Compared to those with less education, adults with a college degree or more were significantly less likely to be close or coresident with at least one parent (54.7% vs. 71.5%) and less likely to be close or coresident with at least one adult child (66.0% vs. 79.4%). There was a correspondingly much higher prevalence of living over 500 miles away from all parents (adult children) for college-educated adults.

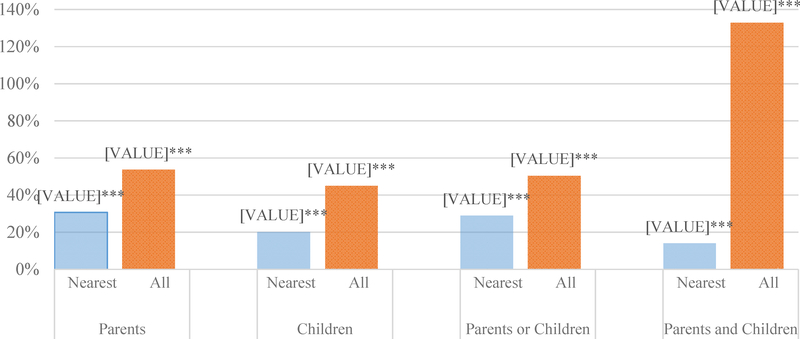

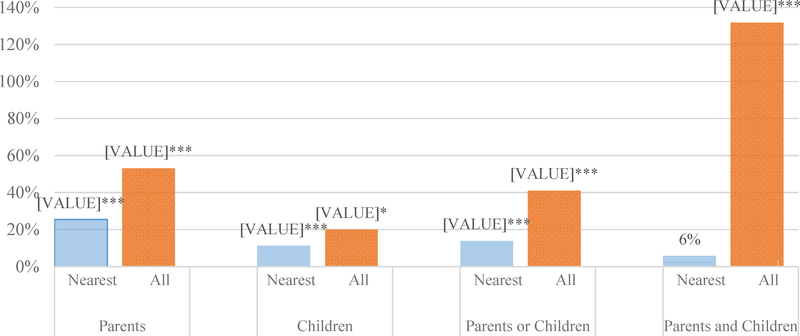

Figure 1 shows the percent differences between education subgroups for having the nearest parent or adult child and all parents and adult children coresident or close. Education differences were much larger for distances to all parents and/or adult children than for nearest parent or adult child. For parents (adult children), less-educated adults were 31% (20%) more likely to live with or close to their nearest parent (adult child) and 54% (45%) more likely to live with or close to all of their parents (adult children). Estimates of educational disparities for individuals in families with three adult generations were especially sensitive to measuring close proximity to the parent or adult child versus all parents and adult children: 14.0% for nearest versus 133.0% for all parents and adult children coresident or close.

Figure 1.

Difference in Prevalence of Coresident or Close, by Education (<16 years minus ≥16 years)/≥16 years

Notes: Nearest distance is based on the sample of PSID heads and spouses 25 and older who have at least one parent and/or adult child with non-missing distance values. Distance to all is based on the sample of PSID heads and spouses for whom all parents and/or adult children of the given type have non-missing distance values. “Parents” include own and spouse’s biological/adoptive parents. “Children” include adult biological/adopted and step children. Close = in the United States and less than 30 miles but not coresident. Asterisks indicate significance levels from testing proximity differences by education as in Table 2 (P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001)

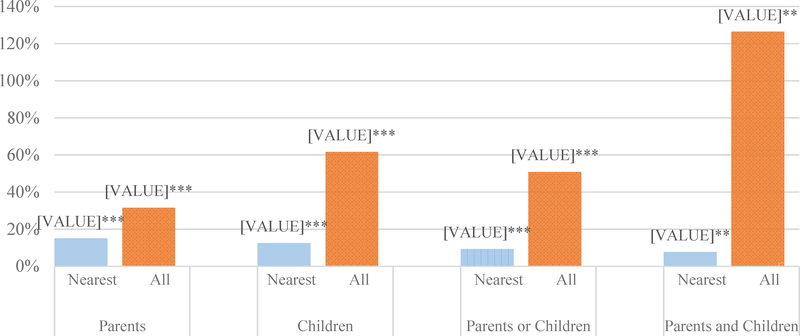

There were also large race differences in proximity to kin. Relative to non-Hispanic Whites, non-Hispanic Blacks were more likely to coreside (8.4% vs. 4.8%) and more likely to live close to a parent (68.0% vs. 61.5%). Non-Hispanic Blacks also were much more likely to live with adult children, but no more likely to live close (Table 2, Panel A). Having all parents and children coreside was rare for both non-Hispanic Blacks and non-Hispanic Whites, but 56.0% (54.5%) of non-Hispanic Blacks had all their parents (all their adult children) coresident or close (Table 2, Panel B). Disparities by race in coresident or close were much larger when comparing proximity to all versus nearest parent (adult child), as shown in Figure 2. For distance to adult children, the former was nearly five times greater, 61.7% versus 12.6%.

Figure 2.

Difference in Prevalence of Coresident or Close, by Race (nonHispanic Black minus nonHispanic White)/nonHispanic White

Notes: Nearest distance is based on the sample of PSID heads and spouses 25 and older who have at least one parent and/or adult child with non-missing distance values. Distance to all is based on the sample of PSID heads and spouses for whom all parents and/or adult children have non-missing distance values. “Parents” include own and spouse’s biological/adoptive parents. “Children” include adult biological/adopted and step children. Close = in the United States and less than 30 miles but not coresident. Asterisks indicate significance levels from testing proximity differences by race as in Table 2 (P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001)

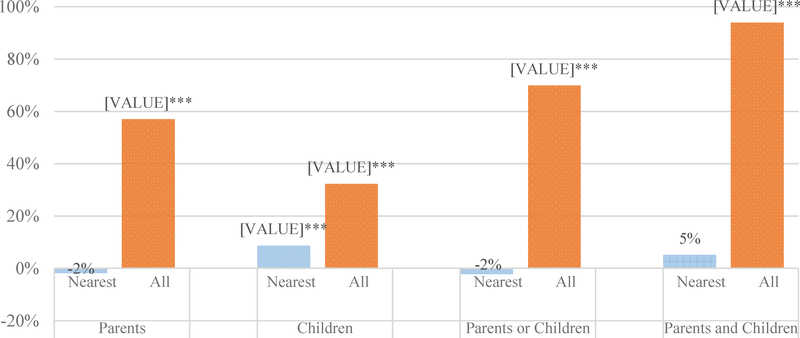

Relative to partnered adults, unpartnered adults were four times more likely to live with a parent (13.9% vs. 3.1%), but less likely to live close to (50.9% vs. 62.9%) and more likely to live very far away from their nearest parent (11.7% vs. 8.4%, Table 2, Panel A). Unpartnered adults were much more likely than partnered adults to have all of their parents living nearby (57.0% vs. 36.3%). This is consistent with married people having more parents (because they have in-laws), and having parents and parents-in-law who may not live near each other. Figure 3 shows that differences in proximity estimates by marital status were much larger for all parents and adult children versus nearest parent or adult child.

Figure 3.

Difference in Prevalence of Coresident or Close, by Partnership Status (Unpartnered minus Partnered)/Partnered

Notes: Nearest distance is based on the sample of PSID heads and spouses 25 and older who have at least one parent and/or adult child with non-missing distance values. Distance to all is based on the sample of PSID heads and spouses for whom all parent and/or adult children have non-missing distance values. “Parents” include own and spouse’s biological/adoptive parents. “Children” include adult biological/adopted and step children. Close = in the United States and less than 30 miles but not coresident. Asterisks indicate significance levels from testing proximity differences by partnership status as in Table 2 (P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001)

Table 3 highlights a generational difference in proximity for individuals living in non-metropolitan areas. Adults in non-metropolitan areas were more likely to have their parents, but less likely to have their adult children coresident or close (Table 3). Only about one quarter (28.9%) of adults living in a non-metropolitan area had all their adult children coresident or close but over 40% of those in a metropolitan area were this close to all their children. Figure 4 indicates that the contrast by metropolitan status also was larger for living near all parents and adult children versus the nearest parent or adult child.

Table 3.

Distance to nearest and to all parents and/or adult children, by metropolitan status

| Panel A. Distance to nearest parent and/or adult child | ||||||||

| % of adults who have the nearest parent within a given distance among those with a living parent | % of adults who have the nearest adult child within a given distance among those with an adult child | % of adults who have the nearest parent and/or adult child in a given distance among those who: |

||||||

| have a living parent or adult child | have a living parent and adult child | |||||||

| by Metro status | Metro | non-Metro | Metro | non-Metro | Metro | non-Metro | Metro | non-Metro |

| Unweighted N | 7340 | 2367 | 3433 | 1430 | 8971 | 3024 | 1802 | 773 |

| Coresident, % | 6.0 | 5.4 | 20.6 | 15.4*** | 13.4 | 12.4 | 24.4 | 18.1** |

| Close, % | 57.9 | 65.9*** | 58.9 | 53.3** | 61.1 | 63.5 | 61.4 | 68.2** |

| Coresident or Close, % | 63.9 | 71.3*** | 79.5 | 68.7*** | 74.5 | 75.9 | 85.8 | 86.3 |

| Very Far, % | 10.3 | 5.9*** | 7.1 | 5.4 | 7.4 | 4.9 | 3.5 | |

| Panel B. Share (%) of adults who have all parents and/or adult children within a given distance | ||||||||

| % of adults who have all parents within a given distance among those with a living parent | % of adults who have all adult children within a given distance among those with an adult child | % of adults who have all parents and/or adult children within a given distance among those who: |

||||||

| have a living parent or adult child | have a living parent and adult child | |||||||

| by Metro status | Metro | non-Metro | Metro | non-Metro | Metro | non-Metro | Metro | non-Metro |

| Unweighted N | 7024 | 2262 | 3223 | 1311 | 8407 | 2789 | 1683 | 715 |

| Coresident, % | 3.3 | 3.0 | 5.6 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 2.0 | ||

| Coresident or Close, % | 39.8 | 47.8*** | 42.8 | 28.9*** | 36.2 | 33.5* | 21.8 | 19.9 |

| Very Far, % | 10.2 | 6.0*** | 7.2 | 5.1* | 7.4 | 4.9*** | 3.2 | |

Notes: Nearest distance is based on the sample of PSID heads and spouses 25 and older who have at least one parent and/or adult child with non-missing distance values. Percent with all parents and/or adult children within a distance is based on the sample of PSID heads and spouses for whom all parents and/or children have non-missing distance values. “Parents” include own and spouse’s biological/adoptive parents. “Adult children” include adult biological/adopted and step children. Close = in the United States and less than 30 miles but not coresident; Very far = at least 500 miles and in the United States. Sample weights are applied for all estimates. Shaded cells have a cell count less than 10 and cannot be reported.

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

Figure 4.

Difference in Prevalence of Coresident or Close, by Metropolitan Status (Metro minus nonMetro)/(nonMetro)

Notes: Nearest distance is based on the sample of PSID heads and spouses 25 and older who have at least one parent and/or adult child with non-missing distance values. Distance to all is based on the sample of PSID heads and spouses for whom all parents and/or adult children have non-missing distance values. “Parents” include own and spouse’s biological/adoptive parents. “Children” include adult biological/adopted and step children. Close = in the United States and less than 30 miles but not coresident. Asterisks indicate significance levels from testing proximity differences by metropolitan status as in Table 3 (P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001)

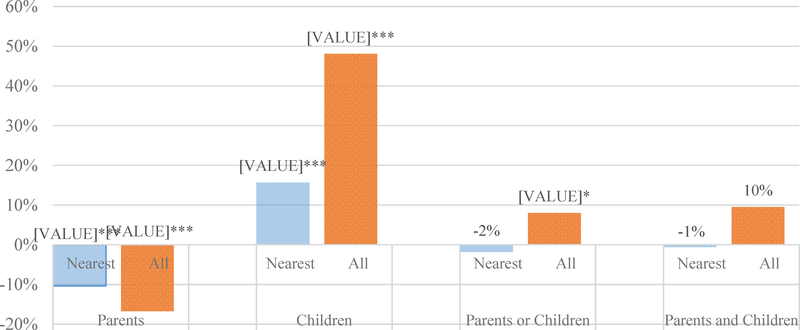

There were large differences in proximity by Census Region of residence. Table 4 shows that adults in the Northeast were more likely to have at least one parent or all parents living with or close to them, compared to adults in the South and the West. The tests of statistical significance evaluate the contrast between Northeast and each of the other three regions. The closer proximity to parents among those in the Northeast also holds for having at least one adult child or all children coresiding or living in close proximity. For example, 52.1% of adults in the Northeast lived near all of their parents compared to only 34.0% in the West. Similarly, 44.7% of adults in the Northeast lived near all of their adult children compared to only 36.8% in the South. As presented in Figure 5, the difference in coresident or close proximity to parents and adult children between the Northeast and the West was larger for all parents and adult children versus nearest parent or adult child, especially among adults in families with three generations of adults (131.9% vs. 5.8%). In fact, the Northeast versus West difference in proximity to nearest parent or adult child is not statistically significant for three-generation families.

Table 4.

Distance to nearest and to all parents and/or adult children, by region

| Panel A. Distance to nearest parent and/or adult child | ||||||||||||||||

| % of adults who have the nearest parent within a given distance among those with a living parent | % of adults who have the nearest adult child within a given distance among those with an adult child | % of adults who have the nearest parent and/or adult child within a given distance among adults who: |

||||||||||||||

| have a living parent or adult child | have a living parent and adult child | |||||||||||||||

| by Region | Northeast (ref) | Midwest | South | West | Northeast (ref) | Midwest | South | West | Northeast (ref) | Midwest | South | West | Northeast (ref) | Midwest | South | West |

| Unweighted N | 1255 | 2449 | 4097 | 1884 | 646 | 1197 | 2134 | 873 | 1569 | 2997 | 5133 | 2268 | 332 | 649 | 1098 | 489 |

| Coresident, % | 5.2 | 5.4 | 6.2 | 6.3 | 23.1 | 15.1*** | 17.9* | 21.6 | 14.2 | 11.3* | 13.1 | 14.0 | 27.5 | 18.6** | 20.6* | 25.8 |

| Close, % | 68.6 | 65.6 | 57.5*** | 52.5*** | 61.2 | 62.7 | 54.2** | 54.1* | 66.4 | 67.6 | 59.5*** | 56.7*** | 63.1 | 67.9 | 63.2 | 59.9 |

| Coresident or Close, % | 73.8 | 71.0 | 63.7*** | 58.8*** | 84.3 | 77.8** | 72.1*** | 75.7*** | 80.6 | 78.9 | 72.6*** | 70.7*** | 90.6 | 86.5 | 83.8** | 85.6 |

| Very Far, % | 5.1 | 5.1 | 11.0*** | 12.6*** | 4.4 | 6.3 | 7.3* | 7.1* | 4.1 | 3.9 | 7.8*** | 9.4*** | 2.2 | 3.5 | 3.1 | |

| Panel B. Share (%) of adults who have all parents and/or adult children within a given distance | ||||||||||||||||

| % of adults who have all parents within a given distance among those with a living parent | % of adults who have all adult children within a given distance among those with an adult child | % of adults who have all parents and/or adult children within a given distance among those who: |

||||||||||||||

| have a living parent or adult child | have a living parent and adult child | |||||||||||||||

| by Region | Northeast (ref) | Midwest | South | West | Northeast (ref) | Midwest | South | West | Northeast (ref) | Midwest | South | West | Northeast (ref) | Midwest | South | West |

| Unweighted N | 1203 | 2346 | 3909 | 1808 | 607 | 1129 | 1975 | 810 | 1471 | 2821 | 4760 | 2118 | 316 | 622 | 1001 | 452 |

| Coresident, % | 3.3 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 2.8 | 6.6 | 2.6*** | 5.2 | 3.9* | 3.0 | 2.2 | 3.1 | 2.4 | ||||

| Coresident or Close, % | 52.1 | 46.8* | 39.4*** | 34.0*** | 44.7 | 38.2* | 36.8** | 37.2* | 44.2 | 37.8*** | 32.9*** | 31.3*** | 32.7 | 22.3** | 20.1*** | 14.1*** |

| Very Far, % | 5.0 | 5.1 | 11.1*** | 12.4*** | 4.0 | 6.6* | 7.1* | 7.2* | 3.9 | 3.9*** | 7.9*** | 9.2*** | 2.3 | 3.0 | 2.9 | |

Notes: Northeast is the reference category for tests of statistical significance. Nearest distance is based on the sample of PSID heads and spouses 25 and older who have at least one parent and/or adult child of the given type with non-missing distance values. Percent with all parents and/or adult children within a distance is based on the sample of PSID heads and spouses for whom all parents and/or adult children of the given type have non-missing distance values. “Parents” include own and spouse’s biological/adoptive parents. “Adult children” includes adult biological/adopted and step children. Close = in the United States and less than 30 miles but not coresident; Very far = at least 500 miles and in the United States. Sample weights are applied for all estimates. Shaded cells have a cell count less than 10 and cannot be reported.

P<0.05

P<0.01

P<0.001

Figure 5.

Difference in Prevalence of Coresident or Close, by Region (Northeast minus West)/(West)

Note: Nearest distance is based on the sample of PSID heads and spouses 25 and older who have at least one parent and/or adult child with non-missing distance values. Distance to all is based on the sample of PSID heads and spouses for whom all parents and/or adult children have non-missing distance values. “Parents” include own and spouse’s biological/adoptive parents. “Children” include adult biological/adopted and step children. Close = in the United States and less than 30 miles but not coresident. Asterisks indicate significance levels from testing proximity differences by region as in Table 4 (P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001)

Conclusion

The portrait of intergenerational spatial proximity that emerges defies simple characterization. On the one hand, three quarters of adults with a living parent or adult child had at least one such relative living within 30 miles. About one third of adults (35.5%) had all their adult biological children, adult stepchildren, biological/ adoptive parents, and parents-in-law living within 30 miles. A substantial minority of adults, however, had no relatives nearby; 6.8% of adults had their nearest such relative farther than 500 miles away in the United States.

There also were large sociodemographic differences in proximity to kin. Among adults who had a parent alive, the share living within 30 miles was much higher for those with less than 16 years of schooling than those with 16 or more years, and for non-Hispanic Blacks than non-Hispanic Whites. That share was also higher for those living in the Northeast and Midwest than the South or West, which in part may be due to the fact that the latter regions are common destinations for international and long-distance internal migrants. Differences by partnership status and metropolitan status are more nuanced. Unpartnered adults were much more likely than partnered adults to live with a parent but also more likely to live very far away. Adults living in metropolitan areas were more likely than adults in non-metropolitan areas to live within 30 miles of an adult child, less likely to live near a parent, and equally likely to live near either an adult child or parent.

Sociodemographic differences in spatial proximity were almost always many times larger when measured by having all relatives of a given type living close by than when measured by proximity to one’s nearest relative. The higher rates of having all parents and/or adult children nearby among non-Hispanic Blacks, those with less than 16 years of schooling, and those in the Northeast can be an important asset, with a greater share of one’s network more readily available to support each other because of close proximity. At the same time, geographic clustering may limit family members’ ability to help each other when dealing with hardships caused by local economic or environmental shocks because they all experience them.

Future studies can build on this brief report in several dimensions. First, although parents and adult children are typically the relatives with the most active networks in the United States (Kahn, McGill, & Bianchi, 2011; Schoeni, 1997), other family members, such as siblings, grandparents, and step relationships from prior marriages, may also be important. Other family members may be more important for those with less education or for non-Whites who are more likely to rely on kin for practical assistance with household tasks and transportation (Sarkisian and Gerstel, 2004). Location data are not available for all of these relatives in the PSID but should be considered for future data collection in the PSID and other surveys. Second, the 2013 PSID sample does not fully represent the roughly 7% of the adult U.S. population in 2013 that immigrated to the United States after 1997, when PSID added a sample of immigrants who arrived after the PSID began in 1968 (Flood et al., 2018). The PSID added in 2017 a sample of immigrants who arrived after 1997, and collecting information on the location of relatives for this sample would allow a more complete description of family networks than is currently possible. Third, collecting city and state location of each relative instead of distance or travel time, which is what most other surveys have done, has the advantage of supporting estimates of having all parents and/or adult children nearby because respondents can readily report city and state. But residential location at the level of city and state is not as precise for large cities as for smaller geographic units and does not support investigations of differences in proximity under 30 miles. These differences in close proximity may matter, especially for providing hands-on care (Litwak & Kulis, 1987). Fourth, many adults do not have certain types of relatives (28% without a living parent and 56% without an adult child), and this varies substantially by socioeconomic status. Incorporating information about the existence of certain types of relatives into studies of spatial proximity of kin will provide a more complete picture of disparity in family availability.

Finally, the unique data described in this report lay the groundwork for investigations of how proximity to family members in several adult generations both reflects and contributes to family solidarity and material exchanges among family members. Family scholars know little about how having all offspring nearby affects the division of responsibility for caring for aging parents or how parents allocate help among their offspring, including help with childcare. These questions are particularly relevant for the growing number of adults, the “sandwich generation,” who have both aging parents and adult children who require care or financial support. Moreover, although there is a long-standing literature examining the support that family members give to each other in times of financial need, there is still little research on how family members who are all in close proximity cope with common experiences, such as the same poor labor or housing markets. The latter is particularly salient, as we have shown that sociodemographic and geographic differences in family proximity are especially large when measured by having all relatives of a given type nearby. Future research should determine the causes and consequences of living near all relatives.

Acknowledgement

The data used in this paper, the 2013 Rosters and Transfers Module of the PSID, as well as the analyses presented, were funded by grant P01 AG029409 from the National Institute on Aging. Some of analyses are also supported by R21 HD087881 from Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development. The project also was supported, in part, by the California Center for Population Research at UCLA (CCPR), which receives core support (P2C-HD041022) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and by the Duke Population Research Institute, which receives core support (P30AG034424) from the National Institute on Aging.

Contributor Information

HwaJung Choi, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan, NCRC Building 14, GR109, 2800 Plymouth Road, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Robert F. Schoeni, Institute for Social Research, Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy, Department of Economics, University of Michigan, 426 Thompson Street, Ann Arbor, Michigan

Emily E. Wiemers, Department of Public Administration and International Affairs, Aging Studies Institute, Syracuse University, 320C Lyman Hall, Syracuse, New York

V. Joseph Hotz, Department of Economics, Duke University, 243 Social Sciences Building, 419 Chapel Drive, Durham, North Carolina.

Judith A. Seltzer, Department of Sociology, University of California, Los Angeles, 264 Haines Hall, Box 951551, 375 Portola Plaza, Los Angeles, California

References

- Adams BN (1968). Kinship in an urban setting. Chicago: Markham. [Google Scholar]

- Agree EM (2018). Demography of Aging and the Family In Hayward MD & Majmundar MK (Eds.), Future directions for the demography of aging: Proceedings of a workshop (pp. 159–186). Washington, D. C.: National Academies Press; 10.17226/25064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi S, McGarry KM, & Seltzer J (2010). Geographic dispersion and the well-being of the elderly. Michigan Retirement Research Center Research Paper 2010–234. https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/78351/wp234.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [Google Scholar]

- Chan TW, & Ermisch J (2015a). Proximity of couples to parents: influences of gender, labor market, and family. Demography, 52, 379–399. 10.1007/s13524-015-0379-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan TW, & Ermisch J (2015b). Residential proximity of parents and their adult offspring in the United Kingdom, 2009–10. Population Studies, 69(3), 355–372. 10.1080/00324728.2015.1107126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H, Schoeni RF, Langa KM, & Heisler MM (2014). Older adults’ residential proximity to their children: Changes after cardiovascular events. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 70(6), 995–1004. 10.1093/geronb/gbu076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H, Schoeni RF, Langa KM, & Heisler MM (2015). Spouse and child availability for newly disabled older adults: Socioeconomic differences and potential role of residential proximity. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 70(3), 462–469. 10.1093/geronb/gbu015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi NG (2003). Coresidence between unmarried aging parents and their adult children. Research on Aging, 25, 384–404. 10.1177/0164027503025004003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RL, & Wolf DA (1992). Proximity of children and elderly migration In Rogers A (Ed.), Elderly migration and population redistribution: A comparative study. London: Belhaven. [Google Scholar]

- Coate P (2013). Parental influence on labor market outcomes and location decisions of young workers Unpublished Manuscript. Duke University; https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/ce65/44f86819e70919a3a7a8df380b3c86582adf.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Coate P, Krolikowski PM, & Zabek M (2017). Parental proximity and earnings after job displacements. Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland WP 17–22. 10.26509/frbc-wp-201722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton J, & Pollak RA (2014). Family proximity, childcare, and women’s labor force attachment. Journal of Urban Economics, 79, 72–90. 10.1016/j.jue.2013.03.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Compton J, & Pollak RA (2015). Proximity and co-residence of adult children and their parents in the United States: Descriptions and correlates. Annals of Economics and Statistics, (117–118), 91–114. DOI: 10.15609/annaeconstat2009.117-118.91 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costa D (1999). A house of her own: Old age assistance and the living arrangements of older nonmarried women. Journal of Public Economics, 72, 39–59. 10.1016/S0047-2727(98)00094-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crimmins EM, & Ingegneri DG (1990). Interaction and living arrangements of older parents and their children: past trends, present determinants, future Implications. Research on Aging, 12(1), 3–35. 10.1177/0164027590121001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawkins CJ (2006). Are social networks the ties that bind families to neighborhoods? Housing Studies, 21(6), 867–881. 10.1080/02673030600917776 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dykstra PA, Kalmijn M, Knijn TCM, Komter AE, Liefbroer AC, & Mulder CH (2006). Family solidarity in the Netherlands. Amsterdam: Dutch University. [Google Scholar]

- Flood S, King M, Rodgers R, Ruggles S, & Warren JR (2018). Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, Current Population Survey: Version 6.0 Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2018 10.18128/D030.V65.0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman VA, & Schoeni R (2016). Generating Nationally Representative Estimates of Multi-generational Families and Related Statistics for Blacks in the PSID PSID Technical Series Paper #16–01, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor: Retrieved from http://psidonline.isr.umich.edu/Publications/Papers/tsp/2016-01_Est_Multi_Gen_Black_Fam.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Garasky S (2002). Where are they going? A comparison of urban and rural youths’ locational choices after leaving the parental home. Social Science Research, 31(3), 409–431. 10.1016/S0049-089X(02)00007-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glick PC, & Lin S-L. (1986). More young adults are living with their parents: Who are they? Journal of Marriage and Family, 48(1), 107–112. http://www.jstor.org/stable/352233 [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider FK, & DaVanzo J (1989). Pathways to independent living in early adulthood: Marriage, semiautonomy, and premarital residential independence. Demography, 26(4), 597–614. 10.2307/206126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider FK, & DaVanzo J (1985). Living arrangements and the transition to adulthood. Demography, 22(4), 543–563. 10.2307/2061587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy E, & Shelton N (2001). Contact between adult children and their parents in Great Britain 1986–99. Environment and Planning A, 33(4), 685–697. 10.1068/a33165 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hank K (2007). Proximity and contacts between older parents and their children: A European comparison. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(1), 157–173. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00351.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Houtven CH, & Norton EC (2004). Informal care and health care use of older adults. Journal of Health Economics, 23, 1159–1180. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2004.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyert DL (1991). Financial and household exchanges between generations. Research on Aging, 13(2), 205–225. 10.1177/0164027591132005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph AE, & Hallman BC (1998). Over the hill and far away: distance as a barrier to the provision of assistance to elderly relatives. Social Science & Medicine, 46(6), 631–639. 10.1016/S0277-9536(97)00181-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn JR, Goldscheider F, & Garcia-Manglano J (2013). Growing parental economic power in parent-adult child households: Coresidence and financial dependency in the United States, 1960–2010. Demography, 50(4), 1449–1475. 10.1007/s13524-013-0196-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn JR, McGill BS, & Bianchi SM (2011). Help to family and friends: Are there gender differences at older ages? Journal of Marriage and Family, 73(1), 77–92. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00790.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmijn M (2006). Educational inequality and family relationships: Influences on contact and proximity. European Sociological Review, 22(1), 1–16. 10.1093/esr/jci036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klatzky SR (1972). Patterns of contact with relatives. Washington, D. C.: American Sociological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Konrad KA, Künemund H, Lommerud KE, & Robledo JR (2002). Geography of the family. American Economic Review, 92(4), 981–998. DOI: 10.1257/00028280260344551 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lauterbach W, & Pillemer K (2001). Social structure and the family: a United States-Germany comparison of residential proximity between parents and adult children. Zeitschrift Für Familienforschung, 13(1), 68–88. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton L, Silverstein M, & Bengtson V (1994). Affection, social contact, and geographic distance between adult children and their parents. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 56(1), 57–68. www.jstor.org/stable/352701 [Google Scholar]

- Lee GR, Dwyer JW, & Coward RT (1990). Residential location and proximity to children among impaired elderly parents. Rural Sociology, 55(4), 579–589. 10.1111/j.1549-0831.1990.tb00698.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leopold T, Geissler F, & Pink S (2012). How far do children move? Spatial distances after leaving the parental home. Social Science Research, 41(4), 991–1002. 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin G, & Rogerson PA (1995). Elderly parents and the geographic availability of their adult children. Research on Aging, 17(3), 303–331. 10.1177/0164027595173004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Litwak E (1960a). Occupational mobility and extended family cohesion. American Sociological Review, 25(1), 9–21. www.jstor.org/stable/2088943 [Google Scholar]

- Litwak E, (1960b). Geographic mobility and extended family cohesion. American Sociological Review, 25(3), 385–394. www.jstor.org/stable/2092085 [Google Scholar]

- Litwak E, & Kulis S (1987). Technology, proximity, and measures of kin support. Journal of Marriage and Family, 49(3), 649–661. DOI: 10.2307/35221010.2307/352210https://www.jstor.org/stable/352210https://www.jstor.org/stable/352210 [Google Scholar]

- Longino CF, Bradley DE, Stoller EP, & Haas WH (2008). Predictors of non-local moves among older adults: A prospective study. Journal of Gerontology: Series B, 63(1), S7–S14. 10.1093/geronb/63.1.S7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmberg G, & Pettersson A (2008). Distance to elderly parents: Analyses of Swedish register data. Demographic Research, 17(23), 679–704. www.jstor.org/stable/26347968 [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, & Espinosa KE (1997). What’s driving Mexico-U.S. migration? A theoretical, empirical, and policy analysis. American Journal of Sociology, 102(4), 939–999. 10.1086/231037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsudaira J (2016). Economic conditions and the living arrangements of young adults: 1960 to 2011. Journal of Population Economics, 29, 167–195. 10.1007/s00148-015-0555-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGarry, & Schoeni R. (1995). Transfer behavior in the Health & Retirement Study: Measurement & redistribution of resources within the family. Journal of Human Resources, 30, S184–S226. www.jstor.org/stable/146283 [Google Scholar]

- Mulder CH, & van der Meer MJ (2009). Geographical distances and support from family members. Population, Space and Place, 15, 381–399. 10.1002/psp.557 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons T (1943). The kinship system of the contemporary United States. American Anthropologist, New Series, 45(1), 22–38. 10.1525/aa.1943.45.1.02a00030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rogerson PA, Weng RH, & Lin G (1993). The spatial separation of parents and their adult children. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 83(4), 656–671. 10.1111/j.1467-8306.1993.tb01959.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi PPH, & Rossi A (1990). Of human bonding: Parent-child relations across the life course. New York: Aldine de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Schoeni RF (1997). Private interhousehold transfers of money and time: new empirical evidence. Review of Income and Wealth, 43(4), 423–48. 10.1111/j.1475-4991.1997.tb00234.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkisian N, & Gerstel N (2004). Kin support among blacks and whites: Race and family organization. American Sociological Review, 69, 812–837. 10.1177/000312240406900604 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shanas E (1982). National survey of the aged (No. 83–20425). Washington D. C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Shanas E (1984). Old parents and middle-aged children: The four-and five-generation family. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 17(1), 7–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasso AT, & Johnson RW (2002). Does informal care from adult children reduce nursing home admissions for the elderly? INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing, 39, 279–297. 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_39.3.279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoeni RF, Bianchi S, S. M., Hotz VJ, Seltzer JA, & Wiemers EE (2015). Intergenerational transfers and rosters of the extended family: A new substudy of the Panel Study of Income Dynamics. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies, 6(3), 319–30. 10.14301/llcs.v6i3.332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan FA, Zhang H, & Wang J (2002). Upstream intergenerational transfers. Southern Economic Journal, 69(2), 363–380. doi: 10.2307/1061677 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spilimbergo A, & Ubeda L (2004). Family attachment and the decision to move by race. Journal of Urban Economics, 55(3), 478–497. 10.1016/j.jue.2003.07.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spitze G, & Logan J (1990). Sons, daughters, and intergenerational social support. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 52(2), 420–430. doi: 10.2307/353036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spring A, Ackert E, Crowder K, & South SJ (2017). Influence of proximity to kin on residential mobility and destination choice: Examining local movers in metropolitan areas. Demography, 54(4), 1277–1304. 10.1007/s13524-017-0587-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone R, Cafferata GL, & Sangl J (1987). Caregivers of the frail elderly: A national profile. The Gerontologist, 27(5), 616–626. 10.1093/geront/27.5.616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Pers M, & Mulder CH (2013). The regional dimension of intergenerational proximity in the Netherlands. Population, Space and Place, 19, 505–521. 10.1002/psp.1729 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wiemers EE, Slanchev V, McGarry K, & Hotz VJ (2017). Living arrangements of mothers and their adult children over the life course. Research on Aging, 39(1) 111–134. 10.1177/0164027516656138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf DA, & Soldo BJ (1988). Household composition choices of older unmarried women. Demography, 25, 387–403. 10.2307/2061539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorlu A (2009). Ethnic differences in spatial mobility: The impact of family ties. Population, Space and Place, 15(4), 323–342. 10.1002/psp.560 [DOI] [Google Scholar]