Abstract

Background

The implementation of evidence-based practices to reduce opioid overdose deaths within communities remains suboptimal. Community engagement can improve the uptake and sustainability of evidence-based practices. The HEALing Communities Study (HCS) aims to reduce opioid overdose deaths through the Communities That HEAL (CTH) intervention, a community-engaged, data-driven planning process that will be implemented in 67 communities across four states.

Methods

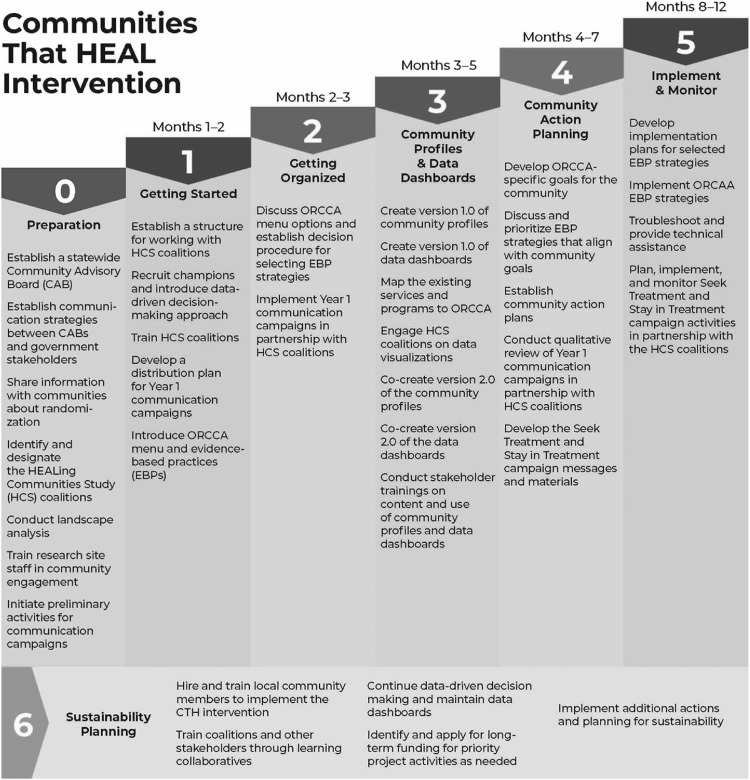

An iterative process was used in the development of the community engagement component of the CTH. The resulting community engagement process uses phased planning steeped in the principles of community based participatory research. Phases include: 0) Preparation, 1) Getting Started, 2) Getting Organized, 3) Community Profiles and Data Dashboards, 4) Community Action Planning, 5) Implementation and Monitoring, and 6) Sustainability Planning.

Discussion

The CTH protocol provides a common structure across the four states for the community-engaged intervention and allows for tailored approaches that meet the unique needs or sociocultural context of each community. Challenges inherent to community engagement work emerged early in the process are discussed.

Conclusion

HCS will show how community engagement can support the implementation of evidence-based practices for addressing the opioid crisis in highly impacted communities. Findings from this study have the potential to provide communities across the country with an evidence-based approach to address their local opioid crisis; advance community engaged research; and contribute to the implementation, sustainability, and adoption of evidence-based practices.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04111939).

Keywords: Opioid use disorder (OUD), Overdose, Community engagement, Community-Based participatory research, Communities that heal, Helping to end addiction long-term, HEALing communities study

1. Introduction

The opioid crisis poses a significant health threat in the United States. In 2018, opioids were implicated in 70 % of fatal drug overdoses (Wilson, 2020). Despite a sense of urgency among researchers, policy makers, and communities the implementation of effective evidence based practices (EBPs) to reduce overdose within communities remains suboptimal. Differences at the community level can make widespread implementation of EBPs to address the opioid crisis challenging (Glasgow et al., 2003). Community level factors play an important role given the broad ecological context in which opioid use disorder (OUD) exists. Differences at the community level may include variations in local demographics, stigma, prevention and treatment infrastructure, justice systems, and policy. The complexity of the opioid crisis necessitates community participation in the design and implementation of local initiatives.

Community engaged research (CEnR) uses a variety of partnership approaches to address our most complex public health crises (CTSA Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force, 2011). A key assumption of CEnR is that communities are experts in their own lived experience and engaging them in the development of solutions can enhance the relevance of interventions and facilitate uptake and sustainability (Minkler et al., 2008; Wallerstein and Duran, 2010). Community engagement is broadly defined as:

“…the process of working collaboratively with and through groups of people affiliated by geographic proximity, special interest, or similar situations to address issues affecting the well-being of those people…it can take many forms, and partners can include organized groups, agencies, institutions, or individuals. Collaborators may be engaged in health promotion, research, or policy making.”

Community-based Participatory Research (CBPR) is often referred to as the CEnR “gold standard” because it is community driven and emphasizes collective action, empowerment, and co-learning (Israel et al., 2018).

Preliminary studies indicate community engagement can increase the participation of diverse sectors in opioid overdose prevention efforts (Albert et al., 2011), as well as elevate the issue of overdose while enhancing intervention sustainability (Alexandridis et al., 2018). More research is needed to inform our understanding of: 1) the impact of community engagement as an approach for implementing EBPs to address public health issues like the opioid crisis, and 2) best practices for engaging communities in the adoption of EBPs for OUD (Glandon et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2018). The HEALing Communities Study (HCS) will add to the evidence base for community engagement as an approach to support implementation and maintenance of EBPs in communities heavily impacted by the opioid crisis (The Healing Communities Study Consortium, 2020). The HCS aims to reduce opioid overdose deaths through the Communities That HEAL (CTH) intervention that includes three components: 1) community engagement, 2) the Opioid-overdose Reduction Continuum of Care Approach (ORCCA) a menu of EBPs to address OUD and opioid overdose deaths, and 3) a set of communication campaigns to reduce stigma and drive demand for EBPs. Overall, the CTH intervention provides a community-engaged, data-driven planning process that will be implemented in 67 communities across four states: Kentucky, Massachusetts, New York, and Ohio. The community engagement component of the CTH intervention was derived from the Communities that Care (CTC) model (Oesterle et al., 2018), a community-change process for reducing youth violence, alcohol, and tobacco use and is steeped in the principles of CBPR. These principles include: co-learning, equitable partnership, power sharing, and local asset devolvement and information sharing (Israel et al., 1998). The CTH uses a multi-site, parallel group, cluster randomized wait-list control trial design where the 67 communities are treated as clusters and are either assigned to receive the CTH intervention or a wait-list comparison arm. Communities randomized to the CTH intervention during the first two years of the study are referred to as Wave 1 communities and communities randomized to the wait-list comparison group are referred to as Wave 2 communities.

This paper augments the extant literature by detailing the community engagement approach employed by the HCS CTH intervention (Holt and Chambers, 2017). The paper has two objectives: 1) describe the community engagement approach and the data driven coalition planning process incorporated in the CTH intervention with an emphasis on flexibility to ensure relevance to diverse community settings, and 2) share early lessons and challenges related to implementing the CTH intervention. We provide a brief background on community engagement and coalition planning in OUD research. Then we describe how community engagement is operationalized in each of the CTH intervention phases and discuss initial challenges with the community engagement approach. Because this research was punctuated by the COVID-19 pandemic, adaptations for implementation in a virtual landscape are also discussed.

1.1. The rationale for community engagement as an implementation strategy in HCS

HCS is using community engagement as an implementation strategy for EBPs including naloxone, medication for OUD (MOUD), and safer prescribing practices for opioids (see Winhusen et al., 2020). Community engagement will include local stakeholders and those who stand to be most impacted by the selection and implementation of EBPs, including people who live, work, and use drugs in communities. Drawing on community member expertise in the selection and tailoring of EBPs can enhance the relevance of interventions, increasing the likelihood of implementation and sustainability (Backer and Guerra, 2011). Community engagement will help ensure that EBPs for OUD and overdose are aligned with community needs, resources, priorities, community norms, and policies.

Coalition building is a well-documented community engagement strategy for planning, executing, adapting, and implementing health prevention and promotion research (Wallerstein et al., 2015, 2011) and has been cited as an effective implementation strategy for EBPs (Powell et al., 2015). A coalition is an alliance of individual and/or organizational stakeholders working together to achieve a mutually agreed upon goal through shared decision-making (Wolff, 2001; Alexander et al., 2016). Mobilization of coalitions can maximize the influence of individuals and organizations, creating new collective resources and reducing duplication of efforts (Butterfoss, 2007; Wandersman et al., 1997). Coalitions allow stakeholders representing diverse community sectors and residents to come together to collectively address public health issues (Butterfoss, 2007; Wallerstein et al., 2011).

Coalition planning processes in studies of addiction research have typically studied the effects of primary prevention-based coalitions focused on preventing the initiation of drug use among youth (Flewelling and Hanley, 2016; Hays et al., 2000; Wandersman and Florin, 2003). However, preliminary findings from a comprehensive coalition-based opioid overdose intervention in North Carolina indicate the approach may facilitate uptake and sustainability of effective treatment interventions as well (Alexandridis et al., 2018). The CTH community engagement intervention was guided by the Communities That Care intervention, a multi-phase coalition planning process that has been elevated as an effective intervention for supporting communities in the selection of evidence-based prevention strategies and policies for reducing youth violence, alcohol, and tobacco use (Oesterle et al., 2018). Establishing and working with community coalitions within the context of the community-engaged CTH intervention has promise for the local implementation of EBPs to prevent fatal opioid overdose, offering 1) resources and infrastructure to support coalitions including funding to hire staff, payment for EBPs (e.g. naloxone), data and web-based dashboards for community decision-making, and community-specific web pages aligned with communication campaigns; 2) a structured approach to planning and implementing EBPs; 3) bidirectional training and technical assistance to support EBP implementation; and 4) a uniform voice across community sectors to elevate the issue and best practices (Flewelling and Hanley, 2016; Hays et al., 2000).

2. Methodology used to develop the CTH community engagement intervention protocol

Community engagement investigators from the HCS Consortium worked together between May and November of 2019 to develop the community engagement component of the CTH intervention. This involved an iterative process of adapting the Communities That Care model to align it with the goal and objectives of the HCS. HCS research staff received training in the principles of CBPR, which was intended to guide the approach to implementing the CTH intervention. Building on the framework of the Communities That Care model, the CTH intervention implements a multi-phase process where community coalitions examine local data and community assets to select and support the implementation of a set of EBPs from the Opioid-overdose Reduction Continuum of Care Approach (ORCCA) menu (Winhusen et al., 2020). EBP selection and implementation is bolstered by communication campaigns to reduce stigma related to OUD and MOUD and increase demand for EBPs (Lefebvre et al., 2020). The overall premise is that engaging relevant sectors of the community, including people with lived OUD experience, will lead to community-relevant selection and implementation of EBPs.

The community engagement approach had to be nimble enough to be employed within diverse communities and unique contexts across the 67 communities. This was particularly true given variation in sociopolitical context, norms, infrastructure, priorities and opioid misuse, OUD, and overdose deaths across and within the participating communities. Each site defined “community” differently, based on regional norms and existing public health infrastructure. (see Table 1 ). In Kentucky and Ohio, community boundaries were established at the county level. New York communities include a mix of counties and municipalities. Massachusetts boundaries were drawn at the municipal level and in some cases involve clusters of small towns. The extent to which variation in community conceptualization may have implications for EBP implementation and reach will be explored.

Table 1.

Coalitions, Communities and Partnerships by State.

| Community Coalitions, Communities and Partnerships by State | |

|---|---|

| Kentucky | Community was defined at the county level. Thirteen Agency for Substance Abuse Policy (ASAP) boards covering all 16 selected counties were engaged during proposal development. Kentucky’s network of ASAP coalitions arose from legislation that required the development of a statewide strategic plan to reduce prevalence of substance use and to suggest aligning policies. During Phase 0 of the Communities That Heal (CTH) intervention, county-specific subcommittees or spin-off taskforces from the ASAP boards were formed for the purposes of guiding the HCS work. In addition to ASAP Boards, key partners included state and local Departments of Public Health, Kentucky Office of Drug Control Policy, Kentucky Division of Behavioral Health, local opioid treatment programs, and the Kentucky Justice and Public Safety Cabinet. |

| Massachusetts | Community was defined at the local level. In MA there are 351 local public health authorities. As such cities and towns comprised community. In some cases, smaller communities were grouped to form clusters. Initially, existing state-funded opioid prevention collaboratives from the communities of interest were engaged. However, not all communities had state-funded prevention collaboratives. Key partners included the state Department of Public Health, anchors agencies and eight community leaders from across sectors. |

| New York | Community was defined at the county level as well as at the municipal level. Community coalitions were not predefined. The overall goal was to establish community coalitions, whose focus would be centered on the study aims. Fifteen New York States County Health Commissioners (CHCs) (now 16) as the backbone, Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), substance use disorder and other treatment and prevention providers as well as the justice system from each county were engaged as partners. |

| Ohio | Community was defined at the county level. Existing community coalitions were identified by local leaders (executive director of mental health boards and public health commissioner) in each of the counties. In the larger counties, substance use specific coalitions were identified, while in smaller counties, community coalitions tended to have a broader mission of the health of their communities. These community coalitions had representatives across sectors, including members from mental health, public health, criminal justice, health care providers and local media. |

Sites built on existing community infrastructure, as such, multiple tactics were used to establish coalitions. For example, Kentucky and Ohio recruited existing coalitions to implement the CTH intervention, and New York established HCS-designated coalitions formed from newly assembled or restructured groups. Massachusetts, meanwhile, relied on a mix of existing and newly established coalitions.

3. The CTH community engagement intervention

The CTH intervention was designed to build community capacity—including inter-organizational relationships and coordination—for implementing and sustaining EBPs to address the opioid crisis and reduce opioid deaths (Dillahunt-Aspillaga et al., 2019; Powell et al., 2015). The HCS research sites support the work of community coalitions across all phases of the CTH intervention, providing training and technical assistance in many areas including: using data to understand local assets and gaps, stigma of OUD and MOUD, EPBs to decrease opioid overdose deaths, decision making strategies to select and gauge the potential success of EBPs, and implementation strategies related to EBPs.

3.1. CTH intervention phases

The CTH intervention includes seven phases: 0) Preparation, 1) Getting Started, 2) Getting Organized, 3) Community Profiles and Data Dashboards, 4) Community Action Planning, 5) Implementation and Monitoring, and 6) Sustainability Planning (Fig. 1 ). Phases of the CTH are sequential, each building on the preceding phase. The phases are designed to guide community coalitions through a systematic partnership process: developing a shared charter, learning about a full range of EBPs, and accessing data to fully describe the local crisis, resources, and gaps. The partnership process culminates in the development and implementation of a community action plan that includes EBPs and implementation strategies from the ORCCA. A community engagement approach is embedded throughout the phases with a focus on co-learning, capacity building, and relationship building.

Fig. 1.

The Communities That HEAL Intervention.

3.2. Phase 0: preparation

During Phase 0, research site staff engage in a set of activities intended to establish the infrastructure in communities to support the CTH. A community advisory board (CAB), separate from local community coalitions, is established for each state to provide feedback and recommendations on HCS activities and approaches, including study design, execution, and methods for overcoming challenges. CABs include membership from each community participating in the HCS, with size ranging from 21 to 30 members. Each CAB typically includes staff from state agencies, people with lived experience with OUD, and frontline workers.

Prior to randomization, research teams identify existing or potential coalitions to partner on the HCS and participate in the CTH intervention. Following randomization of communities into Wave 1 or Wave 2 communities, local HCS research team members visited community coalitions to present an overview of project goals, framework, timeline, randomization results, data collection plans, and next steps. In Wave 1 communities, presentations are followed by either the formation of new HCS community coalitions (MA, NY), or the commitment of established coalitions (KY, OH). While principles of coalition development are included in the CTH manual, state approaches vary and build upon existing OUD initiatives and infrastructure. For example, HCS community coalitions vary in size and membership, though target coalition members include people working in the public health, social service, criminal justice, emergency response, health care delivery and/or addiction services sectors, and individuals who have lived experience with OUD and/or individuals representing private sector businesses.

During Phase 0, research teams conduct a Landscape Analysis (LA) to identify existing community assets for, and barriers to, EBP adoption. Research staff use publicly available administrative data and a thorough online search using standardized search terms and parameters to identify a range of existing resources and organizations (assets) in the communities to address the opioid crisis. Research staff contact a subset of assets to administer surveys that gather detailed information about assets’ services related to OUD. These data provide information to inform community profiles and assist communities in action planning.

3.3. Phase 1: getting started

Phase 1 is the official “launch” of the CTH intervention in Wave 1 communities. Phase 1 employs a number of implementation strategies designed to develop community-academic partnerships and cultivate community coalitions to support the adoption of EBPs. Information about HCS and the CTH is conveyed to community coalitions in presentations and to stakeholders and opinion leaders through one-on-one conversations. Community coalition members discuss their priorities with HCS research teams. A community coalition charter is also developed during Phase 1 to help solidify community-academic partnerships and ensure a shared vision and understanding for CTH implementation.

Individuals are either hired by the research sites, or identified as volunteers within community coalitions to support the CTH. A community engagement facilitator is hired by research staff to coordinate and support the implementation of the CTH in each community. In addition, community champions are selected to serve as liaisons with the community coalition, community engagement facilitator, and research sites. Champions are committed, well connected community members whose roles are in the areas of: 1) communication campaigns, 2) data, and 3) each of the three ORCCA EBPs (i.e., overdose education and naloxone distribution [OEND], MOUD, and safer opioid prescribing). After the charter is created, community coalitions and site research teams review the CTH phases in detail, including the role of data-driven decision making in the CTH process. Site research teams and community coalitions co-create specialized training plans to identify training needs as well as opportunities for community coalition members to provide training on local community context for research teams. To complete Phase 1, research team members with content expertise deliver an introduction to each of the three ORCCA strategies, and the site teams introduce community coalitions to their role in reviewing and selecting EBPs from the ORCCA menu.

3.4. Phase 2: getting organized

Phase 2 activities ensure that community coalitions understand the ORCCA and the rationale for included EBPs. Presentations are provided to familiarize community coalitions with EBPs most likely to achieve reductions in opioid overdose deaths. Research sites also provide community facing teams with training to support community coalitions’ work (Powell et al., 2015). Specific activities include discussing the menu of EBPs, refining the selection process, and developing a shared vision for identifying and implementing EBPs. Discussions facilitated by the community engagement facilitators from each community provide guidance on the decision-making process, including: (1) previewing a Technical Assistance Guide created for the HCS (a compendium of resources to guide data-driven decision making, EBP selection and implementation) (Winhusen et al., 2020); (2) reviewing the rationale for the EBP menu (the evidence of their effectiveness) and the differences among menu options; and (3) discussing how to evaluate potential risks and benefits of each menu option across various settings and populations. Community Coalitions are also encouraged to take advantage of local expertise while reviewing ORCCA menu options, including the active solicitation of input from members with lived experience and organizations currently implementing EBPs. Community coalitions are also involved in planning a series of communication campaigns designed to reduce stigma related to OUD and MOUD and increase demand for EBPs (Lefebvre et al., 2020).

3.5. Phase 3: community profiles and data dashboards

In Phase 3, research site staff engage community coalitions in conversations about local needs, resources, policies, and context to support the development of a shared understanding of the local opioid crisis. Tasks center on the collaborative synthesis of available data to inform community action planning. Data experts work in collaboration with community coalitions and data champions. Through an iterative process, community coalitions and the research site teams compile available data to co-create: 1) a community profile of local OUD resources with the explicit goal of identifying gaps, and 2) a data dashboard to visualize data related to community goals and HCS outcomes (e.g. number of opioid overdose deaths in a community). The community profile summarizes baseline resources, needs, opportunities, and trends in opioid overdose fatalities based on results from the landscape analysis and existing epidemiologic data. A series of meetings and trainings between research site staff, community coalition members, and data champions provide additional data. The data dashboard is a dynamic web-based platform designed in collaboration with communities to visualize data related to community goals and the HCS outcomes (Wu et al., 2020). Community dashboards are designed to support decision making and monitor community-specific metrics and other community-tailored data. During and between community coalition meetings, research site staff encourage and facilitate use of the dashboard. Trainings are held to ensure community coalition members have a shared understanding of how to: 1) interpret data in the profile and dashboard; 2) navigate the dashboard, visualize reports and/or graphs; and 3) use the profile and dashboard to support goal setting, action planning, and implementation monitoring.

3.6. Phase 4: community action planning

In Phase 4, with facilitation support from research sites, community coalitions develop comprehensive action plans to select and implement EBPs and strategies in each of the three ORCCA areas (i.e., OEND, MOUD, safer opioid prescribing) (Winhusen et al., 2020). Action plans provide a blueprint for communities and are intended to ensure the CTH intervention will have sufficient reach and impact to significantly reduce fatal opioid overdose. As part of action planning, community coalitions consider ORCCA strategies within the context of existing community data, resources, and needs. The community coalitions then identify and prioritize feasible, high impact strategies appropriate for their local context. In some communities, this planning process involves reviewing modeling provided by the research sites to better gauge the uptake of EBPs required to achieve desired outcomes (e.g., penetration of MOUD initiation or retention greater than six months). Each action plan includes both required and optional EBPs and ORCCA strategies (see Winhusen et al., 2020). Action plans are used to formulate implementation plans for the selected EBPs with community partner organizations. Implementation plans are executed in Phase 5.

3.7. Phase 5: implementation and monitoring

Phase 5 builds on these action plans to develop and carry out EBP implementation plans. Implementation plans detail how community coalition members and partner organizations will introduce or expand selected EBPs with support from community coalitions and HCS research site staff providing technical assistance. Following a systematic process of collaborative goal-setting and identification of strategies, implementation plans are developed to align with community coalition member and partner needs, capabilities and practices. In forming their implementation plans, organizations can access EBP implementation training materials, manuals, and presentations developed by research sites. Implementation plans are developed for each ORCCA strategy included in the action plan. As community coalitions and research teams monitor and learn from implementation efforts, they may identify opportunities to improve the implementation of EBPs and work together to modify implementation plans as needed.

As new data becomes available, implementation updates for required ORCCA strategies are summarized and reported back to community coalition members and partner organizations. This information will assist them in gauging progress on EBP implementation as well as inform implementation improvements. Timely troubleshooting and technical assistance are critical for supporting a community-engaged intervention to reduce opioid overdose deaths. Strategies to support EBP implementation include: learning collaboratives, quality monitoring tools, meeting facilitation, dynamic training, and technical assistance. Continuous monitoring and clear communication facilitate the timely identification of implementation challenges and inform the provision of TA.

3.8. Phase 6: sustainability

In CTH, sustainability planning is an ongoing process that evolves over the course of the intervention. Building capacity through training and data-driven decision making for the long term are key CTH elements to help community coalitions and partner organizations sustain EBPs after the study ends (Gloppen et al., 2012, 2016; Shelton et al., 2018). All research sites hire and train local community field teams to conduct community engagement activities. Partnering with community coalition members builds local expertise related to data-driven action planning and EBP selection, which can support long-term EBP implementation that in turn leads to improved health outcomes (Johnson et al., 2017). CTH trainings, including those related to identifying and applying for long-term funding, are archived so community members can access these resources after HCS ends. Sites establish Learning Collaboratives (LCs) to help address community coalitions’ and partner organizations’ training and technical assistance needs, share best practices or common barriers and foster sustained coordination and partnering among key stakeholders working to address the opioid crisis in their communities. As a sustainability strategy, community coalitions are encouraged to assume ownership of learning collaboratives developed under HCS or develop new learning collaboratives with key stakeholders to support EBP implementation beyond HCS. Similarly, data tools and data sharing protocols are developed with consideration to maintaining data sources beyond HCS.

Action and implementation plans developed in previous phases include sustainability components. As community coalitions begin to explore the ORCCA menu, develop action plans, and proceed with implementation, they are encouraged to consider facilitators and barriers to sustainability, map out resources to promote sustainability, and prioritize tactics for sustaining EBP strategies beyond the study period. Planned tactics for sustaining EBP implementation may include providing recommendations to decision makers and state agencies for establishing infrastructure and policies that support EBPs (e.g., Medicaid expansion to pay for treatment, peer and recovery services). As community coalitions and partner organizations gain insights from EBP implementation, research sites work with them to develop a detailed sustainability plan. Although CTH focuses on addressing the opioid crisis, sustainability elements of the CTH intervention can be leveraged to address other community health priorities as well.

3.9. Iterative nature of the CTH intervention

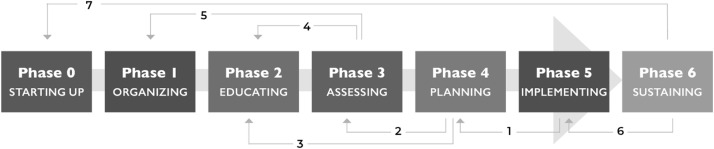

CTH is an iterative intervention, and this flexibility helps ensure responsiveness to community needs and priorities. Community coalitions may revisit decisions made at earlier steps, re-examine data, consider alternative ORCCA EBPs, arrange additional training and technical assistance, and even bring in new stakeholders to broaden the community coalition’s perspective and expertise. Fig. 2 presents examples of seven different junctures that may prompt community coalitions to cycle back to previous phases.

-

1

Phase 5 to Phase 4. Implementation plans are based on community coalition’s overall action plans, so substantive changes to a partner organization’s implementation plan may lead to action plan updates.

-

2

Phase 4 to Phase 3. As community coalitions revise action plans based on unanticipated challenges in implementation, they may need to re-examine community data.

-

3

Phase 4 to Phase 2. Community coalitions may re-examine resources and materials introduced during Phase 2 when partners encounter challenges with a particular ORCCA strategy.

-

4

Phase 3 to Phase 2. A return to Phase 2 may be prompted by the availability of new data or further analysis of existing data over the course of implementation.

-

5

Phase 3 to Phase 1. Community coalitions may want to revise their initial charters to respond to changing circumstances.

-

6

Phase 6 to Phase 5. Community coalitions and partner organizations may find an EBP as implemented is not sustainable and decide to adjust the implementation plan.

-

7

Phase 6 to Phase 0. As part of sustainability planning, community coalitions consider how they want to operate in the future and who needs to be involved in decision making. This may be an opportunity to return to Phase 0 as community coalitions prepare to collectively plan around a new shared intervention area.

Fig. 2.

Examples for Iterating through the CTH Intervention.

The potential to revisit information and decisions made at earlier phases is an advantage of embedding a community engagement approach in the CTH intervention. The ability to flexibly manage intervention content and resources provides community coalitions with the greatest range of options for collective problem solving and shared decision-making.

4. Discussion

The HCS CTH intervention was developed through a collaborative process among HCS consortium investigators from multiple disciplines across four states. Guided by the principles of CBPR, HCS investigators adapted, the Communities That Care model, a successful coalition-based change process for substance use prevention to address the opioid overdose crisis. The CTH intervention is designed as a partnership between academic institutions with content and technical expertise and local community coalitions comprised of diverse community stakeholders, including those most impacted by OUD with community expertise. The CTH is designed to leverage local assets and utilize the knowledge held by local community stakeholders (Gloppen et al., 2012, 2016). With support from research teams, community coalition members interpret local data and select appropriate EBPs, then implement and monitor the impact of those EBPs. Flexibility built into the CTH intervention allows for adaptations based on community context and the ability to iterate through the CTH phases.

To date, operationalizing the CTH protocol across the four states has provided a common structure for the community-engaged intervention while allowing for tailored approaches that meet the unique needs or sociocultural context of each community. For example, the community coalition building strategy, although variable across states, provides a critical space for HCS staff to actively engage a diverse group of community members across multiple sectors.

4.1. Early challenges

A number of challenges inherent to community engagement work were anticipated, including insider-outsider dynamics, competing priorities, distrust, and time constraints (Freeman et al., 2014; Minkler, 2004). Kentucky and Ohio used existing community coalitions established by their states, while New York and Massachusetts built on existing coalition infrastructure to develop new community coalitions. Entering mature community coalitions means the HCS staff are guests who must compete with other efforts and priorities, whereas community coalitions convened explicitly for HCS are driven by HCS priorities. To help address time constraints, HCS subcommittees were added in Phase 1 to move the work forward efficiently without deterring from other coalition business. Although differences in coalitions’ origin, history, and jurisdictions presented some early challenges, the community engagement approach accommodates variation and allows the flexibility to meet communities where they are.

Plans for working directly with communities upon grant award were delayed due to the time required to develop a common CTH protocol. This delay led to some frustration among communities because they were notified of the funding award in April 2019, but protocol was not finalized until Fall 2019. Although the development of a common CTH protocol had tremendous scientific benefit, the shifts in original plans research sites discussed with existing community coalitions during grant writing strained some relationships. In some cases, relationships established early on between research sites and communities were not being maintained and the time gap raised suspicions that the researchers were not holding up their end of the partnerships. Trust, a key factor for strong community-academic partnerships, was undermined and required renewed relationship development. Several CTH components have been critical for regaining trust and building support for HCS. CAB members serve an important role as local and state level thought leaders promoting HCS and the CTH process. For example, in MA, having CAB member liaisons to research cores facilitates relationship development and bi-directional communication. Coalition building along with targeted education, outreach and assessment, as well as the identification of thought leaders and champions has also helped build trust. In addition, Community Engagement Facilitators serve as a critical implementation role spanning the boundary between the institution and community (Kangovi et al., 2015; Wilkinson et al., 2016).

HCS has a very ambitious timeline and, understandably, there is a sense of urgency to implement EBPs that will reduce opioid overdose deaths. A shared sense of urgency can be a rallying point but can also pose challenges for relationship building, due to the lack of time to cultivate relationships. Aligning EBPs with community priorities requires that diverse relationships are formed to ensure a balance of those with authority to make decisions and those who are most impacted, who have the lived experience to inform decision-making. Community-facing research site staff find themselves balancing a tight timeline with the need to cultivate relationships and attend to the partnership process, while navigating local power dynamics and supporting community coalitions with new members, including people with lived experience.

4.2. CBPR and the CTH

Although community input was sought during the proposal development process, the CTH intervention protocol itself was not developed in partnership with community stakeholders and its implementation involves strong oversight by researchers and only guidance, not decision-making, from a CAB. As such, CTH does not meet the criteria for CBPR. However, the community-engaged intervention employs six of nine CBPR principles. CTH (1) recognizes the community as a unit of identity, (2) builds on community assets, (3) promotes co-learning through bi-directional dialogue, (4) emphasizes the value of local knowledge, (5) facilitates a collaborative process through all phases of planning and (6) involves an iterative process (Israel et al., 2018). The extent to which there is a balance between research and action for the benefit of all partners is not yet clear, nor is the long-term fate of the partnership between research teams and HCS communities. Through an intentional merging of community engagement and implementation science (Winhusen et al., 2020), the HCS includes a rigorous mixed-methods evaluation to help document the community engagement approaches that lead to successful and sustained change.

4.3. COVID-19 adaptations

The COVID-19 pandemic fundamentally changed interactions with the community as states executed “stay in place” or “shelter at home” orders. The most immediate change to the CTH intervention was the shift to virtual meetings for coalition work. COVID-19 also impacted coalitions’ capacity to engage in the CTH and public health officials who would have normally championed CTH efforts were leading the local response to COVID-19, leaving limited availability for action planning.

Most coalitions quickly adapted to virtual meetings and interim smaller group meetings to maximize engagement. However, some coalitions had to pause CTH work to respond to COVID-19 in their communities. COVID-19 also challenged research sites to make online meetings engaging (e.g., using breakout rooms for in-depth small group discussions, using in-meeting polling features) and to provide interactive training on how to use new platforms. Moreover, relationship building had to occur through virtual processes, which is not the norm for community engaged research. In some cases, virtual platforms facilitated the work as busy stakeholders and the research team were able to allocate more time for virtual meetings that did not require travel. COVID-19 also highlighted infrastructure disparities across communities. In some HCS communities, coalition members did not have sufficient internet speeds and had to call in via a telephone, limiting their engagement. This raises concern that differential broadband internet access may exacerbate pre-existing power imbalances in community coalitions.

5. Conclusions

Community level variation poses a significant challenge to the widespread implementation of EBPs to reduce opioid overdose deaths (Glasgow et al., 2003). HCS is designed to show how community engagement can support the adoption of EBPs for addressing the opioid crisis in highly-impacted communities despite this variation. While we experienced many expected challenges early in the engagement process, our CTH protocol and process allowed us to successfully address them. Important next steps include rigorous examination of community engagement approaches employed, and their impact on EBP sustainability as well as community-academic relationships. Findings from this study have the potential to advance community engagement research, develop an intervention model other communities can use to address the opioid epidemic, and contribute to the sustainability of adopted EBPs in local communities (Albert et al., 2011; Alexandridis et al., 2018).

Role of funding source

The authors have no affiliation with any organization with a direct or indirect financial interest in the subject matter discussed in the manuscript.

Contributors

BDR, AY, TB, NE, LG, LSM, AFB, BF, PS, EAO, TH, CAR, HS, PRF made contributions to the conceptualization of the manuscript and the intervention. LSM took the lead on writing of the manuscript. BDR, AY, BF, LG, TH, PS, EAO, AFB, TP, GAH, MLD, NE, TB assisted with writing of the manuscript. All authors assisted with editing the manuscript. All authors have reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Financial disclosures

Linda Sprague Martinez is an External Evaluator for CCI Health and Wellness, Inc. and the Boston Public Health Commission as well as a Youth Engagement Consultant for America’s Promise Alliance.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The following authors have affiliations with organizations with direct or indirect financial interest in the subject matter discussed in the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health through the NIH HEAL Initiative under award numbers: UM1DA049406, UM1DA049412, UM1DA049415, UM1DA049417 and UM1DA049394. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or its NIH HEAL Initiative.

References

- Albert S., Brason F.W., Sanford C.K., Dasgupta N., Graham J., Lovette B. Project Lazarus: community-based overdose prevention in rural North Carolina. Pain Med. 2011;12:S77–S85. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander J.A., Hearld L.R., Wolf L.J., Vanderbrink J.M. Aligning Forces for Quality multi-stakeholder healthcare alliances: do they have a sustainable future. Am. J. Manag. Care. 2016;22:S423–S436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandridis A.A., McCort A., Ringwalt C.L., Sachdeva N., Sanford C., Marshall S.W., Mack K., Dasgupta N. A statewide evaluation of seven strategies to reduce opioid overdose in North Carolina. Inj. Prev. 2018;24:48–54. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2017-042396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backer T.E., Guerra N.G. Mobilizing communities to implement evidence-based practices in youth violence prevention: the state of the art. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2011;48:31–42. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9409-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterfoss F.D. John Wiley & Sons; 2007. Coalitions and Partnerships in Community Health. [Google Scholar]

- CTSA Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force . 2nd ed. National Institutes of Health & Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, Georgia: 2011. Principles of Community Engagement. [Google Scholar]

- Dillahunt-Aspillaga C., Bradley S., Ramaiah P., Radwan C., Ottomanelli L. Coalition building: a tool to implement evidenced-based resource facilitation in the VHA: pilot results. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2019;100:e164. [Google Scholar]

- Flewelling R.L., Hanley S.M. Assessing community coalition capacity and its association with underage drinking prevention effectiveness in the context of the SPF SIG. Prev. Sci. 2016;17:830–840. doi: 10.1007/s11121-016-0675-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman E., Seifer S.D., Stupak M., Martinez L.S. Community engagement in the CTSA program: stakeholder responses from a national Delphi process. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2014;7:191–195. doi: 10.1111/cts.12158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glandon D., Paina L., Alonge O., Peters D.H., Bennett S. 10 best resources for community engagement in implementation research. Health Policy Plan. 2017;32:1457–1465. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czx123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow R.E., Lichtenstein E., Marcus A.C. Why don’t we see more translation of health promotion research to practice? Rethinking the efficacy-to-effectiveness transition. Am. J. Public Health. 2003:8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloppen K.M., Arthur M.W., Hawkins J.D., Shapiro V.B. Sustainability of the communities that care prevention system by coalitions participating in the community youth development study. J. Adolesc. Health. 2012;51:259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloppen K.M., Brown E.C., Wagenaar B.H., Hawkins J.D., Rhew I.C., Oesterle S. Sustaining adoption of science-based prevention through communities that care. J. Community Psychol. 2016;44:78–89. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays C.E., Hays S.P., DeVille J.O., Mulhall P.F. Capacity for effectiveness: the relationship between coalition structure and community impact. Eval. Program Plann. 2000;23:373–379. [Google Scholar]

- Holt C.L., Chambers D.A. Opportunities and challenges in conducting community-engaged dissemination/implementation research. Transl. Behav. Med. 2017;7:389–392. doi: 10.1007/s13142-017-0520-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang K.Y., Kwon S.C., Cheng S., Kamboukos D. Unpacking partnership, engagement, and collaboration research to inform implementation strategies development: theoretical frameworks and emerging methodologies. Front. Public Health. 2018;6:190. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel B.A., Schulz A.J., Parker E.A., Becker A.B. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel B.A., Schulz A.J., Parker E.A., Becker A.B., Allen A.J., Guzman R.J., Lichtenstein R. In: Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: Advancing Social Health Equity. Wallerstein N., Duran B., Oetzel J.G., Minkler M., editors. Jossey Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2018. Critical issues in developing and following CBPR principles; pp. 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K., Collins D., Shamblen S., Kenworthy T., Wandersman A. Long-term sustainability of evidence-based prevention interventions and community coalitions survival: a five and one-half year follow-up study. Prev. Sci. 2017;18:610–621. doi: 10.1007/s11121-017-0784-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kangovi S., Grande D., Trinh-Shevrin C. From rhetoric to reality—community health workers in post-reform US health care. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:2277. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1502569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre R.C., Chandler R.K., Helme D.W., Kerner R., Mann S., Stein M.D., Reynolds J., Slater M.D., Anakaraonye A.R., Beard D., Burrus O., Frkovich J., Hedrick H., Lewis N., Rodgers E. Health communication campaigns to drive demand for evidence-based practices and reduce stigma in the HEALing Communities Study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;217 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M. Ethical challenges for the “outside” researcher in community-based participatory research. Health Educ. Behav. 2004;31:684–697. doi: 10.1177/1090198104269566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M., Vasquez V., Chang C., Miller J. University of California, Berkeley, School of Public Health and PolicyLink; 2008. Promoting Healthy Public Policy Through Community-based Participatory Research: Ten Case Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Oesterle S., Kuklinski M.R., Hawkins J.D., Skinner M.L., Guttmannova K., Rhew I.C. Long-term effects of the communities that care trial on substance use, antisocial behavior, and violence through age 21 years. Am. J. Public Health. 2018;108:659–665. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell B.J., Waltz T.J., Chinman M.J., Damschroder L.J., Smith J.L., Matthieu M.M., Proctor E.K., Kirchner J.E.J.I.S. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement. Sci. 2015;10:21. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton R.C., Cooper B.R., Stirman S.W. The sustainability of evidence-based interventions and practices in public health and health care. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 2018;1:55–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-014731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The HEALing Communities Study Consortium HEALing (Helping to End Addiction Long-term) Communities Study: Protocol for a cluster randomized trial at the community level to reduce opioid overdose deaths through implementation of an Integrated set of evidence-based practices. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;217 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N., Duran B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am. J. Public Health. 2010;100:S40–S46. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N.B., Yen I.H., Syme S.L. Integration of social epidemiology and community-engaged interventions to improve health equity. Am. J. Public Health. 2011;101:822–830. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.140988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N., Minkler M., Carter-Edwards L., Avila M., Sánchez V. In: Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice Jossey-Bass. Glanz K., Rimer B.K., Viswanath K.V., editors. 2015. Improving health through community engagement, community organization, and community building; pp. 277–300. [Google Scholar]

- Wandersman A., Florin P. Community interventions and effective prevention. Am. Psychol. 2003;58:441. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.6-7.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wandersman A., Goodman R.M., Butterfoss F.D. In: Community Organizing Community Building for Health. Minkler M., editor. Rutgers University Press; New Brunswick, NJ: 1997. Understanding coalitions and how they operate; pp. 261–277. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson G.W., Mason T., Hirsch G., Calista J.L., Holt L., Toledo J., Zotter J. Community health worker integration in health care, public health, and policy. J. Ambul. Care Manage. 2016;39:2–11. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0000000000000124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson N. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—united States, 2017–2018. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020:69. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6911a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winhusen T., Walley A., Fanucchi L.C., Hunt T., Lyons M., Lofwall M., Brown J.L., Freeman P.R., Nunes E., Beers D., Saitz R., Stambaugh L., Oga E.A., Herron N., Baker T., Cook C.D., Roberts M.F., Alford D.P., Starrels J.L., Chandler R.K. The Opioid-overdose Reduction Continuum of Care Approach (ORCCA): Evidence-based practices in the HEALing Communities Study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;217 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff T. Community coalition building—contemporary practice and research: introduction. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2001;29:165–172. doi: 10.1023/A:1010314326787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu E., Villani J., Davis A., Fareed N., Harris D.R., Huerta T.R., LaRochelle M.R., Miller C.C., Oga E.A. Community dashboards to support data-informed decision-making in the HEALing Communities Study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;217 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]