Abstract

Low concordance between drug-drug interaction (DDI) knowledge bases is a well-documented concern. One potential cause of inconsistency is variability between drug experts in approach to assessing evidence about potential DDIs. In this study, we examined the face validity and inter-rater reliability of a novel DDI evidence evaluation instrument designed to be simple and easy to use.

Methods:

A convenience sample of participants with professional experience evaluating DDI evidence was recruited. Participants independently evaluated pre-selected evidence items for 5 drug pairs using the new instrument. For each drug pair, participants labeled each evidence item as sufficient or insufficient to establish the existence of a DDI based on the evidence categories provided by the instrument. Participants also decided if the overall body of evidence supported a DDI involving the drug pair. Agreement was computed both at the evidence item and drug pair levels. A cut-off of ≥ 70% was chosen as the agreement threshold for percent agreement, while a coefficient > 0.6 was used as the cut-off for chance-corrected agreement. Open ended comments were collected and coded to identify themes related to the participants’ experience using the novel approach.

Results:

The face validity of the new instrument was established by two rounds of evaluation involving a total of 6 experts. Fifteen experts agreed to participate in the reliability assessment, and 14 completed the study. Participant agreement on the sufficiency of 22 of the 34 evidence items (65%) did not exceed the a priori agreement threshold. Similarly, agreement on the sufficiency of evidence for 3 of the 5 drug pairs (60%) was poor. Chance-corrected agreement at the drug pair level further confirmed the poor interrater reliability of the instrument (Gwet’s AC1 = 0.24, Conger’s Kappa =0.24). Participant comments suggested several possible reasons for the disagreements including unaddressed subjectivity in assessing an evidence item’s type and study design, an infeasible separation of evidence evaluation from the consideration of clinical relevance, and potential issues related to the evaluation of DDI case reports.

Conclusions:

Even though the key findings were negative, the study’s results shed light on how experts approach DDI evidence assessment, including the importance situating evidence assessment within the context of consideration of clinical relevance. Analysis of participant comments within the context of the negative findings identified several promising future research directions including: novel computer-based support for evidence assessment; formal evaluation of a more comprehensive evidence assessment approach that requires consideration of specific, explicitly stated, clinical consequences; and more formal investigation of DDI case report assessment instruments.

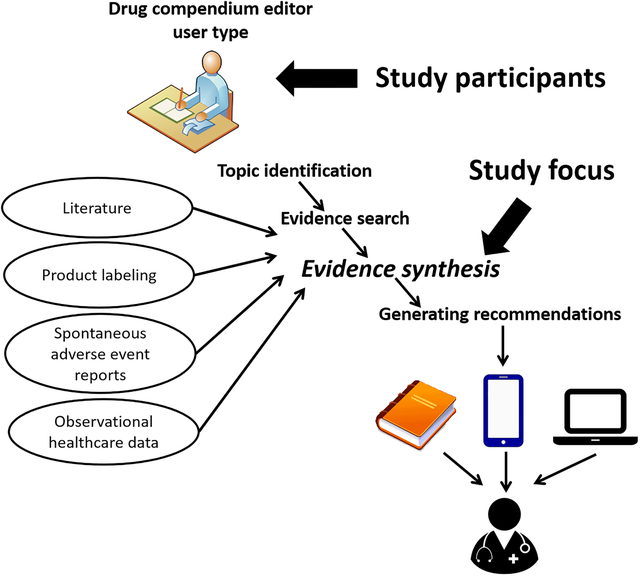

Graphical Abstract

1. BACKGROUND

Drug-drug interactions (DDI) are biological processes that result in a clinically meaningful change to the response of at least one co-administrated drug (1). Identifying potential DDIs during the care process is important to ensure patient safety and health care quality. Unfortunately, cognitive capacity hinders the ability of prescribers to preemptively identify all potential DDIs (2,3). For this reason, various groups have developed computerized alerting systems that provide expert vetted DDI knowledge during the medication prescribing process (4,5). Ideally, these clinical decision support (CDS) systems should provide clinicians with relevant reference information or suggestions, intelligently filtered and presented at appropriate times (6). Unfortunately, the knowledge-bases underlying these DDI CDS systems have long been known to be incomplete and inconsistent with one another. Fung et al. compared 3 commercial DDI knowledge bases used in clinical practice and found that only 5% of 8.6 million unique interacting drug pairs were present in all 3 knowledge bases (7).

We previously described the workflow of individuals who maintain knowledge bases used by clinicians for potential DDI CDS (8). In this paper, we refer to these individuals as compendium editors. The workflow of compendium editors generally involves topic identification, evidence search, evidence synthesis, and generating recommendations (8). A recent study found that compendium editors use various keyword strategies and diverse resources to seek potential DDI evidence within an identified topic (9). This variability in information seeking approaches might partly explain the poor agreement of DDI knowledge bases. Another factor, and the focus of the study reported in this paper, might be variability in how compendium editors synthesize the evidence they retrieve about potential DDIs.

Evidence supporting potential DDIs includes physiological and pharmacological observations from clinical studies; mechanistic knowledge derived from pre-clinical and clinical studies; and observational data including case reports and various non-randomized studies (10,11). This evidence may be useful for merely establishing the existence of an interaction without providing information about the potential clinical effect. Other evidence can help answer questions about the associated clinical effects and their magnitude, variability, and estimated frequency (3).

A recent qualitative study reported that compendia editors tend to focus on gathering sufficient evidence for a recommendation, as opposed to systematic investigation of all available evidence (8). Editors also tended to evaluate evidence informally, with no dedicated support from information tools such as reference management software or databases. Although systematic approaches to evaluate a collection of evidence relevant to establishing DDI exist (12–14), compendia editors generally reported using heuristic and subjective approaches to determine when sufficient evidence had been gathered to make a recommendation (8). Possible reasons for poor adoption of systematic approaches were reported in a 2015 consensus paper (3). Specifically, panelists considered existing approaches more complex than necessary because they combined DDI evidence assessment with questions of clinical relevance, did not explicitly address reasonable extrapolation of DDIs from in vitro findings, and did not explicitly address study quality in the context of establishing the existence of a DDI.

With the goal of addressing potential limitations of existing DDI evidence evaluation approaches, we developed a novel instrument to aid compendia editors as they assess DDI evidence. The instrument, called Drug Interaction eVidence Evaluation (DRIVE), is summarized in the Table 1 and shown completely in the Appendix. DRIVE was designed to be a filter of evidence to support the existence of a DDI using clear and unambiguous criteria. We envisioned that compendia editors would use DRIVE as the first step in a DDI assessment workflow. In the development of DRIVE it was assumed that the determination of the sufficiency of evidence for a DDI should precede assessment of the clinical relevance of the interaction. The basis of this assumption is recognition that, while ample evidence is available for some DDIs, this is not true for many other drug pairs, especially given the large number of theoretical interactions based on pharmacology and/or pharmacokinetic principles.

Table 1.

A simplified version of the DRug Interaction eVidence Evaluation (DRIVE) instrument (see the instrument in the Appendix)

| Category | Evidence |

|---|---|

|

Sufficient

Sufficient evidence that a drug interaction exists and can be evaluated for clinical relevance |

One or more of the following: (Direct evidence for a given pair of drugs)

(Indirect evidence involving related drugs)

(Inference based on mechanisms)

|

|

Insufficient

Insufficient evidence that a drug interaction exists |

One or more of the following, without supporting evidence from the “sufficient” category:

|

Criteria for what constitutes a well-designed study is provided in Appendix A.

The study demonstrates relevant clinical or appropriate surrogate outcomes that support an interaction.

Horn JR et al. Ann Pharmacother 2007;41:674–80.

Application to transporters is less certain. This is a rapidly evolving field of study.

Product labeling and regulatory documents are evaluated by the same criteria as other types of evidence; statements in product labeling or regulatory documents that are unsubstantiated by data or pharmacologic properties of the drug(s) are considered insufficient evidence.

Unpublished statements or data provided by product sponsors/manufacturers (frequently referenced as “data on file”) that are not included in product labeling or regulatory documents, cannot be verified or scientifically reviewed by an independent group of experts, and are considered insufficient evidence.

We designed DRIVE to provide simple evidence categories that a compendia editor would use to rate DDI evidence as sufficient or insufficient to support the existence of a DDI, thereby disentangling sufficiency assessment from evaluation of clinical relevancy. Other unique features of DRIVE were the incorporation of a DDI case report causality assessment instrument called the Drug Interaction Probability Scale (DIPS) (15), guidance on how knowledge of the pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic properties of pharmacologically similar drugs serves as sufficient evidence to establish a DDI (i.e., reasonable extrapolation), and guidance on how to asses DDI statements provided in product labeling as DDI evidence.

Although thoughtfully designed, DRIVE needed testing with compendia editors before broad dissemination. In this paper, we report on a study assessing DRIVE with respect to face validity and inter-rater reliability.

2. METHODS

2.1. Overview of the DRIVE

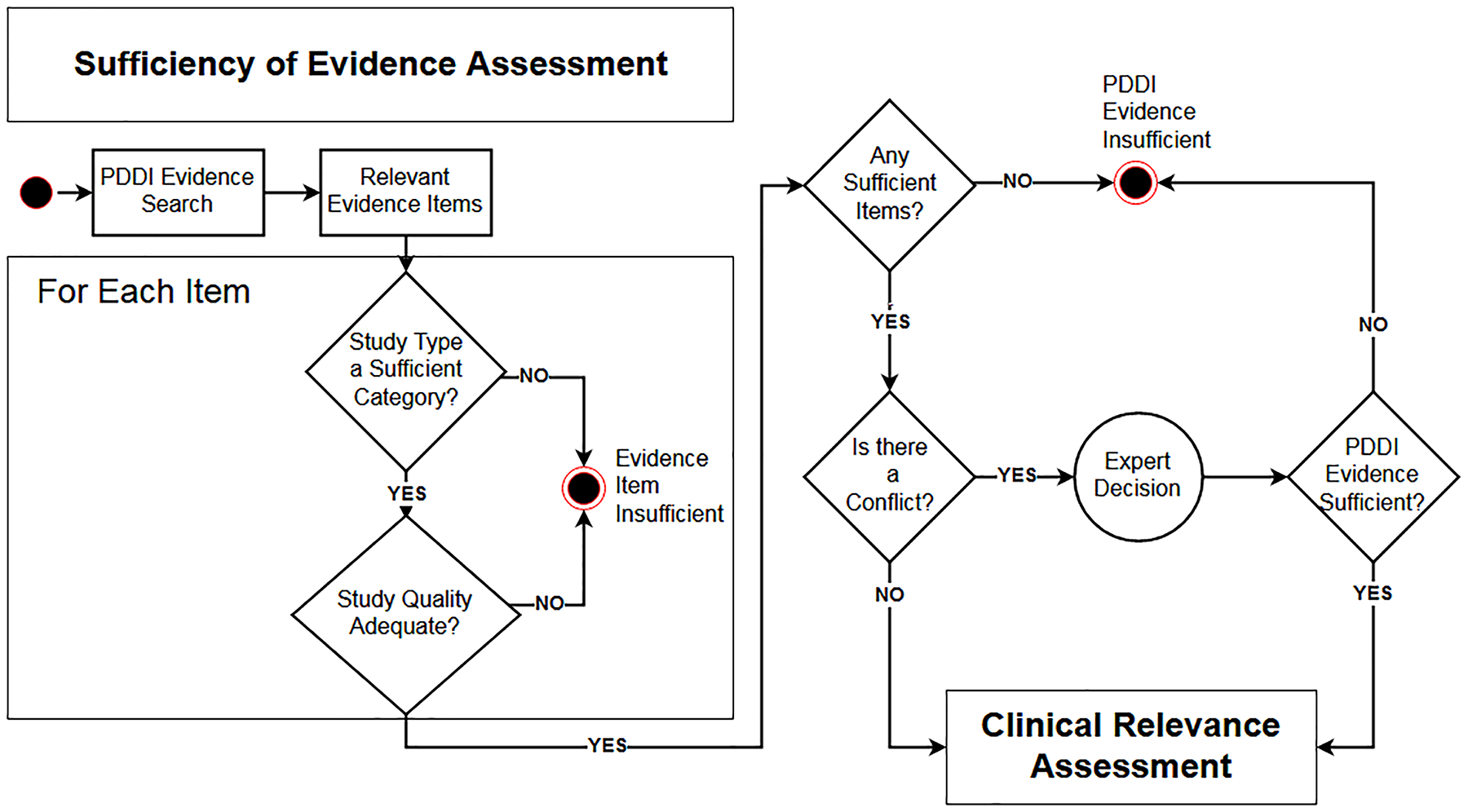

Figure 1 shows a workflow diagram of the DRIVE evidence sufficiency assessment that was the focus of this study. To use DRIVE for a given potential DDI, a reviewer would begin by determining the DRIVE evidence category (Table 1) that best fit each evidence item considered relevant. DRIVE provided 6 evidence categories considered sufficient for establishing the existence of a DDI, and 7 categories considered insufficient. The reviewer would also check that evidence items he/she considered belonging to a sufficient category satisfied quality criteria using guidance provided in the DRIVE handout (Appendix A). After reviewing all relevant evidence items, the reviewer would label the DDI as sufficiently supported if one or more evidence items met a sufficiency criterion and there was no conflicting information. The search and selection of relevant evidence items shown in the diagram was not the focus of this study but is indicated as a necessary pre-condition. Similarly, an assessment of clinical relevance was outside the scope of DRIVE and so was not a part of this study.

Figure 1.

Flowchart illustrating the workflow of the DRIVE instrument utilized for assessment of the evidence about a potential drug-drug interaction (PDDI).

2.2. Evaluations

This study was undertaken in two stages: a face validity assessment, followed by an inter-rater reliability assessment using percent agreement and chance-corrected agreement coefficients. Institutional Review Board exemption from human subjects’ research requirements was obtained by the University of Pittsburgh.

2.3. Face Validity

Prior to enrolling participants for the inter-rater reliability study, we conducted an evaluation to determine if compendia editors found the instrument easy to understand and helpful. This evaluation involved two phases: a first round to identify recommendations for improvement; a second round to ensure that the changes led to improvements and that no new issues surfaced.

The face validity assessment included input from six experts who routinely evaluate drug interaction evidence and write supporting statements that accompany clinical decision support for DDIs. A test set of drug pairs included three examples of varying levels of complexity: 1) simvastatin + fluconazole (considered to be straightforward); 2) fluoxetine + selegiline (more challenging because the interaction depends on drug formulation); and 3) ritonavir + rifabutin (substantially more challenging because the interaction involves enzyme induction and rifabutin can be both inducer and victim).

Each participant was provided the same set of evidence items for each of the three test drug pairs. The DRIVE evaluation was completed for each drug pair along with a questionnaire assessing the participant’s level of understanding regarding evidence categories and descriptions, as well as perceptions of usefulness and ease of use of the DRIVE. After completing the three DRIVE evaluations, participants were scheduled for a one-hour webinar interview and discussion session with one to two investigators (RB, KR, LH). The first four interview and questionnaire results were summarized and presented to the research team that developed the DRIVE. Changes were made based upon feedback and the revised instrument was administered to two additional participants.

2.4. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

A convenience sample of clinicians with expertise in evaluating the evidence for drug interactions was recruited to participate in this study. Participants represented the intended users of DRIVE and were required to have at least graduate level training in clinical pharmacology as well as the ability to read and comprehend the scientific and regulatory literature. We sought to recruit 15 experts because this was thought to be sufficient to evaluate inter-rater reliability and a reasonable sample of the small population of experts whose work involves evaluating DDI evidence. Individuals who assisted in the design of DRIVE were excluded.

Our recruitment strategy included sending email invitations to 1) all members of the three workgroups who participated in a consensus building conference series focusing on DDI evidence and decision support (3), and 2) persons working at drug information centers in the United States. Suggestions of appropriate people to invite for the inter-rater reliability testing were requested from email recipients.

2.5. Selection of Drug Pairs

We selected the following 5 drug pairs that we thought would result in a variety of evidence categories and respondent burden:

azithromcyin + digoxin

rivaroxaban + clarithromycin

levofloxacin + ondansetron

simvastatin + fluconazole

fluoxetine + selegiline

All pairs shared the common feature of being reported as a potential drug interaction in at least one clinically oriented resource. The set of 5 drug pairs was carefully chosen to include interactions occurring by different mechanisms (i.e., pharmacokinetic /pharmacodynamic) and a variety of evidence types such as in vitro/in vivo studies, case reports, reasonable extrapolation, animal data, product labeling, and clinical studies (defined as randomized trials, observational, case control, or cohort studies), or retrospective analysis of patient charts or electronic medical records. It should be noted that the 5 drug pairs were not chosen from any “gold standard” set of DDIs. Rather, the drug pairs were chosen such that the corresponding collection of evidence was representative of what compendia editors typically encounter. In an effort to keep the participant review times brief, a small number of evidence items (between 4 and 10) were included for each of the drug pairs.

We provided pre-selected evidence items for each of the 5 drug pairs to participants to eliminate variability associated with participants conducting their own literature searches (9). Participants were asked to assume that the evidence items comprised the entire body of available evidence related to each drug pair. Participants were told that assessment of the clinical relevance of a DDI for which there was sufficient evidence support was out of scope for this study.

2.6. DRIVE Completion

Participants were provided instructions along with an email link to an online Qualtrics® based survey to apply DRIVE to each drug pair. Full text copies of relevant articles and other evidence items were linked to the survey (copyright permission had been obtained for full text journal articles). Participants completed DDI causality assessments for case reports using the DIPS instrument (see Appendix A). After evaluating all items for a drug pair, participants rated the overall body of evidence for a drug pair as sufficient or insufficient to support the existence of an interaction (Figure 1). Participants were instructed to base their overall rating solely on the evidence items provided. They were asked to not incorporate their own clinical knowledge of other evidence not provided. A comment field was also provided for participants to share their thoughts or concerns during the evaluation process.

We estimated 2–5 hours to review the instructions and all of the evidence provided. Participants were allowed to start/stop as needed, but they were encouraged to complete each survey within two weeks of receipt. An email reminder was sent if a survey was not submitted within two-weeks of receipt. Each drug pair was evaluated sequentially; upon submitting a completed survey, participants were provided materials for the next drug pair. After completing evaluations for the first 3 drug pairs, participants were provided a $125 gift card to thank them for their time and incentivize completion of the remaining two drug pair surveys.

2.7. Data Analysis

Three different measures of inter-rater reliability were used. Percent agreement was used to assess inter-rater reliability in assessing the sufficiency of individual evidence items. Two chance corrected agreement coefficients were used to assess inter-rater reliability on the overall sufficiency of evidence for the 5 drug pairs used in the study. Conger’s Kappa was used because it applies to multiple-raters and Gwet’s AC1 was chosen because it is a paradox-resistant alternative to kappa coefficient when the overall percentage agreement is high (16). Intra-rater reliability refers to a single rater obtaining the same results when performing repeated assessments of evidence. We did not evaluate intra-rater reliability because of the short duration of the study.

Data from the inter-rater reliability survey were exported into a spreadsheet for summary and analysis. Demographic data and participant responses were analyzed using descriptive statistics. For percent agreement we chose a reasonable cut-off of ≥ 70% as the threshold for agreement. Chance-corrected agreement coefficients calculations were performed using AgreeStat 2013.3 for Excel (Advanced Analytics, LLC Gaithersburg, MD). The extent of agreement was assessed using the benchmark proposed by Landis and Koch where a coefficient >0.6 indicates substantial agreement and a value >0.8 near-perfect agreement (17).

Participant comments were evaluated to identify themes, explain inconsistencies, or identify issues that should be addressed with DRIVE. The data were entered into NVivo® software to easily link each comment to a category. Comments addressing several issues were linked to multiple categories.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Face Validity

Participants in the initial round of face-validity assessment suggested more clarity around the context of the DRIVE e.g., that it was designed to help establish the existence of a DDI, but does not address clinical relevance, sub-populations, or modifying factors. We added a flow chart to the DRIVE instructions (shown in the Appendix) to clarify that the DRIVE is the first step in evaluating a potential DDI.

Other comments indicated differing viewpoints on whether “in vitro substrate” evidence should be listed among the sufficient evidence categories while listing “in vitro inhibition” among the insufficient categories. We decided that, since there was very little empirical evidence to support or refute either viewpoint on in vitro evidence, any decision would ultimately be subjective. So, we retained the two evidence categories originally specified by the DRIVE development team while providing more information about these kinds of studies in DRIVE’s reasonable extrapolation guidance (Appendix).

Additional comments related to uncertainty about how to evaluate information from product labels. Participants noted that label information is vague, and they were unclear what constitutes sufficient information. They asked for clarification regarding the DRIVE category “unsupported data on file” which was intended to cover cases where a source makes a PDDI claim with only a vague mention to proprietary data. We addressed these comments by adding clarifications to the DRIVE for these evidence categories. Instructions for the instrument were also modified to improve comprehension and understanding by the end user. After making these modifications, two additional participants completed the same process. These participants suggested that examples of sufficient and insufficient information for each study category would be helpful. The research team was concerned that including examples for each study type would make the instructions too lengthy, so an online appendix was linked to the instructions with specific examples. The results were summarized, and no further changes were deemed necessary.

3.2. Inter-rater Reliability

Fifteen experts agreed to participate in the inter-rater reliability evaluation. Due to time constraints, one individual was unable to complete all five potential DDI evaluations and this person’s evaluations were excluded from the analysis. Table 3 shows that respondents were primarily female (79%), with an average of nearly ten years of self-reported experience assessing DDI evidence (standard deviation 7.9). Participants self-identified primarily as either an employee of a commercial drug information knowledge base vendor (n=7, 50%) or a commercial clinical solution vendor (n=6, 43%).

Table 3.

Demographics

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 3 (21%) |

| Female | 11 (79%) |

| Avg Years Experience (sd) | 9.7 (7.9) |

| Type of Organization | |

| Knowledgebase Vendor | 7 (50%) |

| Clinical Solutions Vendor | 6 (43%) |

| University hospital | 1 (7%) |

Across the five drug pairs, participants rated the sufficiency of a total of 34 evidence items. Participant ratings agreed 65% of the time (22/34 items) which did not exceed the a priori 70% threshold that we set for inter-rater agreement (Table 4). The highest amount of agreement was for product labeling evidence items, with percent agreement ranging from 71% to 100% for 11 items. Percent agreement on the sufficiency of 7 case report evidence items ranged from 29% to 71% with only 1 item passing 70%. Participants agreed on the evidence rating for clinical study items 55% (6/11) of the time with percent agreement on individual items ranging from 14% to 93%. Discrepancies were common when evaluating in vitro data. Agreement on the three evidence items containing solely in vitro data (not mixed with animal data) varied from 21% to 71%.

Table 4.

Agreement on evidence item sufficiency

| AGREEMENT | SUFFICIENT % | INSUFFICIENT % | EVIDENCE TYPE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Pair 1 Digoxin/Azithromycin | ||||

| Item 1 | No | 43% | 57% | In vitro |

| Item 2 | No | 57% | 43% | Clinical study |

| Item 3 | Yes | 7% | 93% | Product label |

| Item 4 | Yes | 0% | 100% | Product label |

| Drug Pair 2 Rivaroxaban/Clarithromycin | ||||

| Item 1 | Yes | 29% | 71% | In vitro |

| Item 2 | Yes | 86% | 14% | Clinical study |

| Item 3 | Yes | 21% | 79% | Product label |

| Item 4 | Yes | 21% | 79% | Product label |

| Drug Pair 3 Ondansetron/Levofloxacin | ||||

| Item 1 | No | 43% | 57% | Clinical study |

| Item 2 | Yes | 93% | 7% | Clinical study |

| Item 3 | Yes | 71% | 29% | Clinical study |

| Item 4 | Yes | 71% | 29% | Clinical study |

| Item 5 | No | 57% | 43% | Clinical study |

| Item 6 | Yes | 14% | 86% | Product label |

| Item 7 | Yes | 14% | 86% | Product label |

| Drug Pair 4 Simvastatin/Fluconazole | ||||

| Item 1 | Yes | 79% | 21% | In vitro |

| Item 2 | No | 64% | 36% | Case report |

| Item 3 | Yes | 29% | 71% | Case report |

| Item 4 | No | 43% | 57% | Case report |

| Item 5 | No | 64% | 36% | Case report |

| Item 6 | Yes | 21% | 79% | In vitro / Animal |

| Item 7 | Yes | 86% | 14% | Clinical study |

| Item 8 | Yes | 14% | 86% | Product label |

| Item 9 | Yes | 29% | 71% | Product label |

| Drug Pair 5 Fluoxetine/Selegiline | ||||

| Item 1 | No | 36% | 64% | Case report |

| Item 2 | Yes | 0% | 100% | Animal |

| Item 3 | No | 57% | 43% | Case report |

| Item 4 | No | 57% | 43% | Clinical study |

| Item 5 | No | 64% | 36% | Case report |

| Item 6 | Yes | 29% | 71% | Clinical study |

| Item 7 | No | 64% | 36% | Clinical study |

| Item 8 | Yes | 7% | 93% | Product label |

| Item 9 | Yes | 14% | 86% | Product label |

| Item 10 | Yes | 7% | 93% | Product label |

There was no agreement on the sufficiency of the overall body of evidence for each of the five drug pairs with a percent agreement of only 60% (3/5 pairs) (Table 5), a Gwet’s AC1 coefficient of 0.24, and a Conger’s Kappa coefficient of 0.24 (see Table 6).

Table 5.

Agreement on sufficient vs insufficient ratings at the drug pair level

| Agreement | Sufficient | Insufficient | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potential DDI 1 (Digoxin/Azithromycin) | Yes | 3 (21%) | 11 (79%)* |

| Potential DDI 2 (Rivaroxaban/Clarithromycin) | No | 9 (64%) | 5 (36%) |

| Potential DDI 3 (Ondansetron/Levofloxacin) | Yes | 2 (14%) | 12 (86%)* |

| Potential DDI 4 (Simvastatin/Fluconazole) | Yes | 12 (86%)* | 2 (14%) |

| Potential DDI 5 (Fluoxetine/Selegiline) | No | 6 (43%) | 8 (57%) |

Greater than 70% agreement denotes inter-rater agreement

Table 6.

Inter-rater agreement on sufficient vs insufficient rating across the 5 drug pairs

| METHOD | Coefficient | Inference/Subjects | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| StdErr | 95% C.I. | p-Value | ||

| Conger’s Kappa | 0.23684 | 0.11598 | −0.085 to 0.559 | 1.107E-01 |

3.3. Participant comments

After reviewing the comments independently, two investigators (AG and BS) grouped comments into the following four categories 1) drug and interaction information; 2) study design; 3) evidence; and 4) recommendations. Similarly, sub-categories were developed under each of the four primary groups (see Table 2) and the two investigators categorized each of the 244 comments, compared, discussed, and then revised to reflect consensus. Participant comments illuminated several issues that warrant further consideration. Overall, participants felt that product labels were not very helpful in determining the existence of a DDI. One participant stated, “The product labeling makes a very conservative recommendation based on potential interactions with other macrolides and acknowledges the lack of data to support that recommendation. This evidence is insufficient.” Similar comments reiterated limitations by noting that general contraindications are made in labels without reference to supporting evidence. Another issue was that many of the drug pairs were not specifically included in the label, or a cautionary statement was made based on a potential class effect. Multiple comments were made that “absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.”

Table 2.

Thematic categories of participant comments while assessing evidence

| Drug and Interaction Information | Evidence | Recommendations | Study Design | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| biological relativity | contradicting results | conservative label | case study | isolated case | |||

| clinical consequence | potential interaction | contraindicated DDI | considerations | consider other published data | multiple cases | ||

| potential side effects | does not meet criteria | consider prescription guidelines | Extrapolation | extrapolation reasonable | |||

| clinical relevance | clinically irrelevant | high degree of conformation | consider route of administration | excessive extrapolation | |||

| clinically meaningful | hypothesis generating | consider toxicity levels | good study design | ||||

| may be clinically relevant in special at-risk populations | neither for or against | legal requirements to include | in vitro study | ||||

| not clinically significant | not specific to drug interaction | no precautions necessary | in vivo animal study | ||||

| unclear clinical relevance | possible external gathering source | no problem present | not an applicable setting | ||||

| inconclusive macrolide affect | Quality and content of report | DIPS | did not apply DIPS | overly cautious | poor study design | ||

| inhibitors | lack of clear distinction of strong and moderate inhibitors | DIPS standard not met | warrants monitoring | problematic study | |||

| strong to moderate CYP inhibitor | sufficient DIPS score | prospective observational study | |||||

| low magnitude | FDA report | unknown interaction | restricted study | ||||

| possible other factors | questionable source credibility | unclear magnitude | retrospective chart review | ||||

| questionable timeframe | Statement | abstract statement | significance | no significant difference | |||

| rare but possible | generic statement | significant limitations | |||||

| use of comparison | Type of evidence | insufficient evidence | statistically significant | ||||

| missing evidence | small sample size | ||||||

| too many variables | |||||||

| not enough evidence to support mechanism | well-designed methods | ||||||

| not meaningful evidence | wide confidence interval | ||||||

| supporting evidence | |||||||

| various interpretations | |||||||

Although it was explicitly stated that the DRIVE does not address DDI risk modifying factors, participants consistently noted that these need to be considered. One comment regarding an interaction between ondansetron and levofloxacin was “while there is evidence that an interaction can exist, it is unclear what the interaction will be and what the risk factors are given the variability of the patient populations and effects.” Another participant commenting on the same interaction mentioned that the decreased bioavailability of oral vs IV ondansetron raises the possibility of differential risk based upon the route or dose, as has been noted with other QT prolongation drugs such as haloperidol. A third participant noted the interaction may only be significant in patients with additional risk factors such as electrolyte disturbances.

Similar to the comments about risk factors, many comments related to clinical significance of an interaction despite instructions that DRIVE ignores clinical relevance. One expert rated the interaction between azithromycin and digoxin as insufficient and commented the “magnitude of effect and clinical relevance still appear to be somewhat unknown.” Others commented that interactions may be clinically irrelevant or not meaningful, or consequences may be of low or unclear magnitude. In contrast, other comments argued that there may be relevance when evidence pointed to no interaction. Another comment illustrates this: “Despite article opinion that a 54% increase is not important it may be of clinical as well as statistical significance. Their explanation that the difference is within the normal variation doesn’t take into consideration the effect that could happen if a patient was already on the high end of that variation.”

The analysis of comments found that participants considered many studies insufficient because of flaws in study design. Small sample size, lack of transparency in methods, insufficient references to support extrapolations, and no inclusion of risk factors were a few of the examples cited for problematic study designs. Not all study flaws were as clearly delineated, as demonstrated by the following comment, “This study design does not allow you to draw conclusions on causality of DDI.” Similarly, participants noted “well-done study design” was a reason for rating evidence as sufficient. One participant commented, “The methods and well-known design characteristics help reduce the bias and push this article to a high degree of confirmation and utility for DDI.”

The last theme identified was surrounding the use of DIPS for case reports. There was considerable variability in the DIPS scores calculated by participants. The calculated DIPS scores for a simvastatin/fluconazole case report (Item 2) ranged from 2 to 5. We noticed that some participants did not use the suggested DIPS score cut-off of ≥ 5 as sufficient evidence. One participant labeled a case report sufficient evidence based on a DIPS score of 2. Another participant indicated that their organization “usually includes only DDI case reports that have a score of 4 or higher.” Yet another participant calculated a DIPS score of 5 but still rated this evidence item as insufficient.

4. DISCUSSION

Although the face validity evaluation of DRIVE suggested it to be potentially usable and useful, the inter-rater reliability assessment did not yield positive findings. Of 34 evidence item ratings, participants agreed on sufficiency for 22 items (65%). As one would expect, the low level of agreement on the sufficiency of evidence items was matched by a low level of agreement on the sufficiency of evidence for each of the five drug pairs (60%). This, along with the low and non-significant inter-rater reliability statistics indicate that DRIVE, as originally designed is not as useful as anticipated for evaluating the evidence for existence of a DDI.

We examined possible reasons for the lack of agreement among participants. Participant comments demonstrated differences of opinion in identifying if studies were designed appropriately. While evaluating study design is critical to evidence assessment, the nuances of flawed studies are not always obvious. Experience and knowledge of specific in vitro and in vivo pharmacology research methods might play a large role in whether evaluators rate a given evidence item as sufficient or insufficient to support the existence of an interaction. This suggests a need to study novel methods to remove subjectivity from determining the type of an evidence item and whether it satisfies quality criteria.

We think that a particularly promising future research direction would be computerized decision support to help experts be more objective at determining the category that an evidence item belongs to and if it meets relevant quality criteria. In a separate study we showed proof-of-concept for an ontology-based system that accurately categorizes DDI evidence items into complex evidence categories based on a small set of simple questions (18). In future work, we intend to extend this system to support study quality assessment, and then test if the novel form of decision support increases agreement among compendia editors on the sufficiency of individual evidence items.

Another issue identified in the participant comments is that participants found it difficult to separate consideration of the existence of a DDI from interpretation of clinical relevance. By design, the DRIVE was not intended to address the clinical relevance of an interaction, only whether a DDI actually exists based on available evidence. The justification for this design decision was that assessing the existence of a DDI is a critical step in the overall DDI evaluation process. However, results from this study suggest that treating this as a crisp distinction is difficult. Rather, an approach that supports assessing clinical relevance as an integrated part of overall evidence evaluation seems necessary.

Of interest, Seden et. al. have developed guiding criteria inspired by the widely used Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach (14). The approach focuses on DDIs that might occur during treatment for specific disorders such as HIV and malaria co-infection (14), Hepatitis C (19), or cancer (20). The Seden approach is different from the approach we took in the current study of selecting potentially interacting drug pairs without consideration of a specific clinical context. Our approach made sense to us initially because many potential DDIs are reported with no mention of a possible clinical consequence (21). However, a recent report by the Semantic Web in Health Care and Life Sciences Community Group (22), and other consensus efforts (4,23), note this is not a preferred practice. Instead, it is recommended that the clinical consequence(s) of a potential DDI be included in all DDI knowledge artifacts intended for clinical use. We think that future work should seek to formally evaluate the approach of Seden et al. while integrating lessons learned from the current study and focusing only on potential DDIs that could result in specific, explicitly stated, clinical consequences.

Finally, there may be less standardization with calculating a DIPS score than these authors anticipated. Based on the wide variation in participant-calculated scores it seems that there might be a subjective component to DIPS evaluation that could result in discrepant evidence ratings. Additional investigation into the inter-rater reliability of DIPS and how use of the DIPS scale could be more standardized would be beneficial.

One potential limitation of this study is that we used a convenience sample that might not necessarily be representative of the users who would ultimately rely on the DRIVE as an evaluation tool. Drug interaction experts whose work involved PDDIs are a relatively small and specialized population. Our recently published survey of how such experts conduct PDDI literature searches used a sampling frame of 70 and had a total of 20 participants who completed the survey (9). This is comparable to the total number of experts involved in the current study (6 in establishing the face validity of DRIVE and 14 for reliability assessment). A larger sample was desirable but both the time demand and remuneration cost for reliability assessment limited the number of experts that we could enroll. However, we think it unlikely that a larger sample size would have led to different conclusions because agreement was consistently poor on both the sufficiency of evidence types and the overall DDI evidence assessment. For this reason, we think that the scientific contribution of this study to provide a baseline that informs development of a better tools to support DDI evidence assessment.

There are other potential limitations. The level of experience of the participants in number of years varies but, due to small sample size, we did not conduct an analysis to find correlations between the years of experience and level of agreement. A larger sample might help explain some of the reasons for the difference of opinions seen in this study. Another limitation is that, due to time constraints, participants reviewed a relatively small amount of evidence that was chosen for them by the research team to be representative of the variety of evidence items compendia editors’ encounter during their normal work process. Finally, DRIVE did not prescribe any approach to weighting evidence items. As a result, the tool did not address how to handle conflicting evidence.

5. CONCLUSION

DRIVE was designed to address the need for a simple to use and highly adoptable tool to assess a body of evidence to support the existence of a DDI. Although DRIVE was found to have face validity, it was not shown to have inter-rater reliability among experts who evaluate the DDI evidence. Possible reasons include unaddressed subjectivity in assessing an evidence item’s type and study design, an infeasible separation of evidence evaluation from the consideration of clinical relevance, and potential issues related to the evaluation of DDI case reports. Analysis of participant comments within the context of the negative findings identified several promising future research directions including: novel computer-based support for evidence assessment; formal evaluation of a more comprehensive evidence assessment approach that enforces consideration of specific, explicitly stated, clinical consequences; and more formal investigation of DDI case report assessment instruments such as the DIPS.

Supplementary Material

6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was funded in part by a grant from the National Library of Medicine: “Addressing gaps in clinically useful evidence on drug-drug interactions” (R01LM011838). We thank Britney Stottlemyer for helping with the thematic analysis of participant comments.

7. REFERENCES

- 1.“DIDEO Contributors.” Definition of “drug-drug interaction” from the Drug-drug Interaction and Drug-drug Interaction Evidence Ontology (DIDEO) [Internet]. 2017. [cited 2017 Nov 30]. Available from: http://www.obofoundry.org/ontology/dideo.html

- 2.van der Sijs H, Aarts J, van Gelder T, Berg M, Vulto A. Turning off frequently overridden drug alerts: limited opportunities for doing it safely. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008;15(4):439–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheife RT, Hines LE, Boyce RD, Chung SP, Momper JD, Sommer CD, et al. Consensus recommendations for systematic evaluation of drug-drug interaction evidence for clinical decision support. Drug Saf. 2015. February;38(2):197–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Payne TH, Hines LE, Chan RC, Hartman S, Kapusnik-Uner J, Russ AL, et al. Recommendations to improve the usability of drug-drug interaction clinical decision support alerts. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015. November;22(6):1243–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolfstadt JI, Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Lee M, Kalkar S, Wu W, et al. The effect of computerized physician order entry with clinical decision support on the rates of adverse drug events: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(4):451–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sirajuddin AM, Osheroff JA, Sittig DF, Chuo J, Velasco F, Collins DA. Implementation pearls from a new guidebook on improving medication use and outcomes with clinical decision support. Effective CDS is essential for addressing healthcare performance improvement imperatives. J Healthc Inf Manag. 2009;23(4):38–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fung KW, Kapusnik-Uner J, Cunningham J, Higby-Baker S, Bodenreider O. Comparison of three commercial knowledge bases for detection of drug-drug interactions in clinical decision support. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017. July 1;24(4):806–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Romagnoli KM, Nelson SD, Hines L, Empey P, Boyce RD, Hochheiser H. Information needs for making clinical recommendations about potential drug-drug interactions: a synthesis of literature review and interviews. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2017. February 22;17(1):21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grizzle AJ, Horn J, Collins C, Schneider J, Malone DC, Stottlemyer B, et al. Identifying Common Methods Used by Drug Interaction Experts for Finding Evidence About Potential Drug-Drug Interactions: Web-Based Survey. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2019. January 4;21(1):e11182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brochhausen M, Utecht J, Judkins J, Schneider J, Boyce R. Formalizing Evidence Type Definitions for Drug-drug Interaction Studies to Improve Evidence Base Curation In: Proceedings in process [Internet]. Hangzhou, China; 2017. [cited 2017 Jul 5]. Available from: http://jodischneider.com/pubs/medinfo2017.pdf [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brochhausen M, Schneider J, Malone D, Empey PE, Hogan WR, Boyce RD. Towards a foundational representation of potential drug-drug interaction knowledge. In: First International Workshop on Drug Interaction Knowledge Representation (DIKR-2014) at the International Conference on Biomedical Ontologies (ICBO; 2014). 2014. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Böttiger Y, Laine K, Andersson ML, Korhonen T, Molin B, Ovesjö M-L, et al. SFINX-a drug-drug interaction database designed for clinical decision support systems. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009. June;65(6):627–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Roon EN, Flikweert S, le Comte M, Langendijk PNJ, Kwee-Zuiderwijk WJM, Smits P, et al. Clinical relevance of drug-drug interactions : a structured assessment procedure. Drug Saf. 2005;28(12):1131–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seden K, Gibbons S, Marzolini C, Schapiro JM, Burger DM, Back DJ, et al. Development of an evidence evaluation and synthesis system for drug-drug interactions, and its application to a systematic review of HIV and malaria co-infection. PLOS ONE. 2017. March 23;12(3):e0173509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horn JR, Hansten PD, Chan L-N. Proposal for a new tool to evaluate drug interaction cases. Ann Pharmacother. 2007. April;41(4):674–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gwet KL. Handbook of Inter-Rater Reliability, 4th Edition: The Definitive Guide to Measuring The Extent of Agreement Among Raters. Advanced Analytics, LLC; 2014. 429 p. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977. March;33(1):159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Utecht J, Brochhausen M, Judkins J, Schneider J, Boyce RD. Formalizing Evidence Type Definitions for Drug-Drug Interaction Studies to Improve Evidence Base Curation. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2017;245:960–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Internal. Liverpool HEP Interactions [Internet]. 2019. [cited 2019 May 4]. Available from: https://www.hep-druginteractions.org/

- 20.Internal. Cancer Drug Interactions from Radboud UMC and University of Liverpool [Internet]. 2019. [cited 2019 May 4]. Available from: https://cancer-druginteractions.org/

- 21.Ayvaz S, Horn J, Hassanzadeh O, Zhu Q, Stan J, Tatonetti NP, et al. Toward a complete dataset of drug-drug interaction information from publicly available sources. J Biomed Inform. 2015. Jun;55:206–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boyce R, Garcia E, Hochheiser H, Ayvaz S, Sahay R, Dumontier M. A Minimum Representation of Potential Drug-Drug Interaction Knowledge and Evidence - Technical and User-centered Foundation [Internet]. The W3C Semantic Web in Health Care and Life Sciences Community Group; 2019. May [cited 2017 Jul 5]. Available from: https://w3id.org/hclscg/pddi [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tilson H, Hines LE, McEvoy G, Weinstein DM, Hansten PD, Matuszewski K, et al. Recommendations for selecting drug-drug interactions for clinical decision support. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016. April 15;73(8):576–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.