Abstract

A 65-year-old woman presented with a neuroendocrine pancreatic head tumor and known liver and bone metastasis. We performed Tc-99m-tektrotyd scintigraphy on this patient, which showed more developed diffuse bone metastases, in addition to the known lesions.

Keywords: Bone marrow metastasis, neuroendocrine tumor, pancreatic tumor, somatostatinreceptor scintigraphy

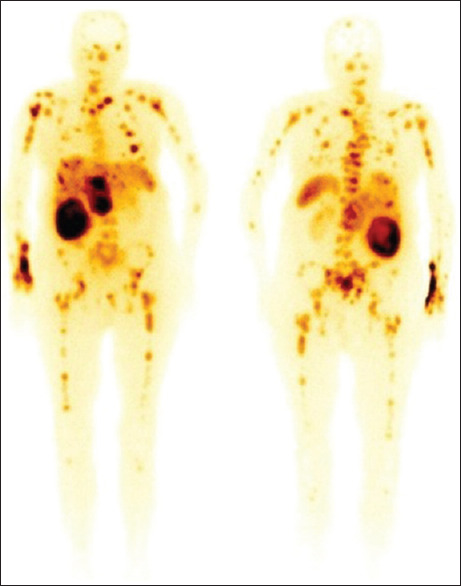

A 65-year-old woman with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (NET) who has hepatic and skeletal metastases discovered with contrast-enhanced computed tomography. The patient underwent two full-body scans acquired 15 min and 3 h after intravenous injection of 740 MBq (20 mCi) of 99mTc-ethylenediammonium diacetate- tricine-hydrazinonicotinamide-Tyr0- octreotide (Tektrotyd) which showing an intense uptake in the area of the head pancreatic mass, in the liver metastasis [Figure 1] and in diffuse bone metastasis interesting the axial and peripheral skeleton [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

Single-photon emission computed tomography-computed tomography (TEKTROTYD) showing an intense uptake in the area of the head pancreatic mass (upper image) and a large metastasis in the liver segment VI (lower image)

Figure 2.

Whole-body scan (anterior and posterior) diffuse bone metastasis

Pancreatic NETs are rare neoplasms that develop from the endocrine tissues of the pancreas. The reported incidence of 0.0003% to 0.001% of all cancers.[1,2,3] This incidence has been increasing throughout the world over the past two decades.[3,4] About 32%–73% of cases are metastatic at the moment of diagnosis.[4,5] The most common site of metastatic disease involvement for pancreatic NET is the liver.[6,7,8] Only 6%–13% of pancreatic NET patients will demonstrate skeletal metastasis.[9,10] Diffuse bone metastases in the entire axial and appendicular skeleton, as the case of our patient, are rare.[9,10,11,12,13,14] The European NET Society consensus guidelines recommend the use of both anatomic imaging, i.e. magnetic resonance imaging and functional whole-body imaging methods, including bone scintigraphy and somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (SRS), for the detection of bone metastases.[15] In the last few decades, the superior value of positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) over SRS in the diagnosis of NENs, particularly after the introduction of 68Ga-DOTA-peptides that specifically bind to somatostatin receptors, has been widely demonstrated.[16] In our department, we do not have PET/CT that is why we use tektrotyd.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Halfdanarson TR, Rabe KG, Rubin J, Petersen GM. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs): Incidence, prognosis and recent trend toward improved survival. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1727–33. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yao JC, Hassan M, Phan A, Dagohoy C, Leary C, Mares JE, et al. One hundred years after “carcinoid”: Epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3063–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hallet J, Law CH, Cukier M, Saskin R, Liu N, Singh S. Exploring the rising incidence of neuroendocrine tumors: A population-based analysis of epidemiology, metastatic presentation, and outcomes. Cancer. 2015;121:589–97. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dasari A, Shen C, Halperin D, Zhao B, Zhou S, Xu Y, et al. Trends in the incidence, prevalence, and survival outcomes in patients with neuroendocrine tumors in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1335–42. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zerbi A, Falconi M, Rindi G, Delle Fave G, Tomassetti P, Pasquali C, et al. Clinicopathological features of pancreatic endocrine tumors: A prospective multicenter study in Italy of 297 sporadic cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1421–9. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milan SA, Yeo CJ. Neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas. Curr Opin Oncol. 2012;24:46–55. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32834c554d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harring TR, Nguyen NT, Goss JA, O’Mahony CA. Treatment of liver metastases in patients with neuroendocrine tumors: A comprehensive review. Int J Hepatol. 2011;2011:154541. doi: 10.4061/2011/154541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riihimäki M, Hemminki A, Sundquist K, Sundquist J, Hemminki K. The epidemiology of metastases in neuroendocrine tumors. Int J Cancer. 2016;139:2679–86. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meijer WG, van der Veer E, Jager PL, van der Jagt EJ, Piers BA, Kema IP, et al. Bone metastases in carcinoid tumors: Clinical features, imaging characteristics, and markers of bone metabolism. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:184–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Loon K, Zhang L, Keiser J, Carrasco C, Glass K, Ramirez MT, et al. Bone metastases and skeletal-related events from neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr Connect. 2015;4:9–17. doi: 10.1530/EC-14-0119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tomassetti P, Campana D, Piscitelli L, Casadei R, Santini D, Nori F, et al. Endocrine pancreatic tumors: Factors correlated with survival. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:1806–10. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cossetti RJ, Bezerra RO, Gumz B, Telles A, Costa FP. Whole body diffusion for metastatic disease assessment in neuroendocrine carcinomas: Comparison with OctreoScan ® in two cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:82. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-10-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Basu S, Ranade R, Thapa P. Metastatic neuroendocrine tumor with extensive bone marrow involvement at diagnosis: Evaluation of response and hematological toxicity profile of PRRT with (177) Lu-DOTATATE. World J Nucl Med. 2016;15:38–43. doi: 10.4103/1450-1147.165353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adkins J, Lu Y. Diffuse bone metastases in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor shown on octreoscan. Clin Nucl Med. 2019;44:257–8. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000002455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kos-Kudła B, O’Toole D, Falconi M, Gross D, Klöppel G, Sundin A, et al. ENETS consensus guidelines for the management of bone and lung metastases from neuroendocrine tumors. Neuroendocrinology. 2010;91:341–50. doi: 10.1159/000287255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Etchebehere EC, de Oliveira Santos A, Gumz B, Vicente A, Hoff PG, Corradi G, et al. 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT, 99mTc-HYNIC-octreotide SPECT/CT, and whole-body MR imaging in detection of neuroendocrine tumors: A prospective trial. J Nucl Med. 2014;55:1598–604. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.144543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]