Abstract

Objective

To determine whether mean platelet volume (MPV) and selected single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that have been associated with MPV in genome-wide association studies relate to stroke severity, functional outcome on discharge, and 1-year mortality in patients with ischemic stroke, we retrospectively analyzed 577 patients with first-ever ischemic stroke.

Methods

Genotyping of 3 SNPs (rs342293, rs1354034, rs7961894) was performed using a real-time PCR allelic discrimination assay. Multivariable regression was used to determine the association of MPV and MPV-associated SNPs with the NIH Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score on admission, modified Rankin Scale score on discharge, and data on 1-year mortality.

Results

Rs7961894, but not rs342293 or rs1354034 SNP, was independently associated with an MPV in the highest quartile (MPV Q4). MPV Q4 was associated with significantly greater admission NIHSS (p = 0.006), poor discharge outcome (p = 0.034), and worse 1-year mortality (p = 0.033). After adjustment for pertinent covariates, MPV Q4 remained independently associated with a greater admission NIHSS score (p = 0.025). The T>C variant of rs7961894 SNP was an independent marker of a lower 1-year mortality (hazard ratio, 0.30; 95% confidence interval, 0.13–0.70; p = 0.006) in the studied population.

Conclusion

MPV is a marker of stroke severity and T>C variant of rs7961894 is independently associated with greater MPV in acute phase of ischemic stroke and relates to decreased 1-year mortality after stroke.

Platelets play a key role in inflammation, thrombosis, and atherogenesis and represent a main target for secondary ischemic stroke prevention.1,2 The mean platelet volume (MPV) is a readily available parameter that indirectly reflects platelet activity.3–5 Larger platelets have greater prothrombotic activity as they contain more granules6 and produce greater amounts of vasoactive substances such as thromboxane A2, serotonin, ATP, and β-thromboglobulin.3,6–8 Moreover, larger platelets show a greater expression of adhesion molecules and aggregate more rapidly under stimulation with ADP, adrenaline, and collagen.5–7

The MPV is largely determined by genetic factors9–11 and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified multiple single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with MPV.12–16 There is increasing interest in whether an elevated MPV and MPV-associated SNPs may serve as markers for an unfavorable outcome in patients with cardiovascular diseases. For example, an elevated MPV has been associated with an increased number of cardiac complications as well as worse short- and long-term mortality in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD).17,18 Moreover, it has been shown that carriers of the G>C rs342293 variant, which has been associated with higher MPV, had a significantly increased risk of adverse cardiac events after undergoing coronary artery stenting.19

MPV's potential utility as a prognostic marker specifically for ischemic stroke remains controversial and data regarding the association of MPV-related SNPs with outcome after ischemic stroke are lacking. Although several studies reported an association between elevated MPV with a worse admission NIH Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score,20,21 functional outcome,21–24 and poststroke mortality,21 other studies did not find such associations.25–28 Although likely reasons for these discrepant results relate to the small sample sizes, different inclusion criteria, and absent correction for the initial stroke severity,22–25,27 a possible contribution of genetic differences appears likely but has not been formally assessed.

In this study, we sought to determine the potential association of MPV and select SNPs (rs342293, rs1354034, and rs7961894) that have been shown to have the strongest association with MPV in GWAS performed in European populations with stroke severity, functional disability at discharge, and 1-year mortality after first-ever ischemic stroke.

Methods

Study cohort

Using our local prospective stroke registry, we retrospectively identified adult patients (age ≥18 years) with acute ischemic stroke who were hospitalized at the Stroke Unit, Krakow University Hospital, Poland, between January 2007 and December 2011 and between January 2013 and June 2015.

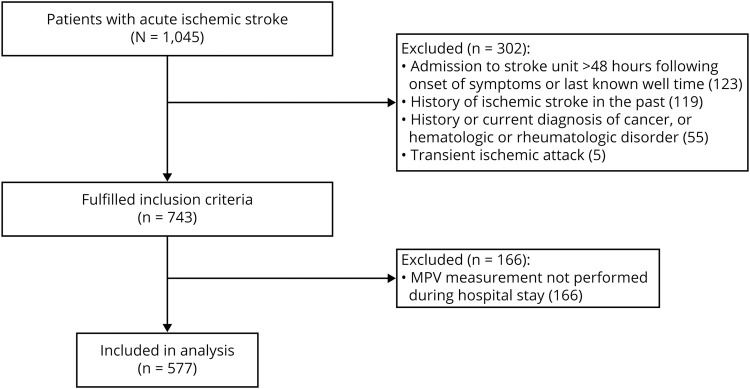

A priori defined exclusion criteria were admission to the stroke unit beyond 48 hours after the onset of stroke symptoms or last known well (LKW) time, absent MPV assessment during hospitalization, diagnosis of TIA, and history of ischemic stroke. Patients with concomitant comorbidities known to affect hemostatic parameters such as pregnancy, history of malignancy (present and past), hematologic disorders, and rheumatologic diseases were excluded (figure 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart of study design and patient selection.

MPV = mean platelet volume.

Information on age, sex, obesity, smoking status, preexisting conditions (hypertension, CAD, diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation), time from symptom onset or LKW time, time from admission to blood draw, and laboratory data (complete blood count including MPV, creatinine, glucose, and lipid panel) were collected for each participant. The diagnosis of an acute ischemic stroke was confirmed by neuroimaging (CT or MRI obtained during the index admission).

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

Our investigation was approved by Jagiellonian University Medical College Institutional Review Board. All patients or their legal representatives gave written informed consent before inclusion into the study.

Risk factor definitions

Obesity was defined as body mass index >30. Smoking was noted if the patient or family member reported active smoking or smoking within 6 months prior to the admission. The presence of hypertension was based on the use of antihypertensive medications or systolic blood pressure of ≥140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure of ≥90 mm Hg on 2 separate occasions with exclusion of the first 3 days after the stroke onset. Diabetes mellitus was noted in cases with history of fasting glucose 7 mmol/L or current use of hypoglycemic drugs as defined according to the National Diabetes Data Group and WHO.29 CAD was defined as history of myocardial infarction within the past 20 years, multivessel coronary disease with symptoms or with history of stable or unstable angina, history of percutaneous coronary intervention, or multivessel coronary artery bypass graft surgery.

Mean platelet volume measurement

A standardized blood draw protocol was used to avoid confounding by difference in sample handling and processing. In brief, fasting venous blood samples were drawn in the morning from all participants and collected into ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) tubes. Samples were stored at room temperature and processed within 1–2 hours after venipuncture according to existing hospital standards. EDTA samples were analyzed in an automated hematology analysis system (Sysmex XE-2100; Sysmex Corp., Kobe, Japan). If more than 1 MPV measurement was obtained during the hospital stay, measurements were categorized into 3 epochs based on the time of blood collection: from admission to the 3rd day after admission (epoch T1), between the 4th and 7th day of hospitalization (epoch T2), and between the 8th and 14th day of hospitalization (epoch T3). Because 23.9% of included patients had their MPV obtained after the 3rd day (18.7% between 4th and 7th day of hospitalization [epoch T2] and 5.2% between 8th and 14th day of hospitalization [epoch T3]), we serially compared the MPV in 109 patients who had MPV measurements available for all 3 defined epochs (T1, T2, and T3). Overall, there was no difference in the MPV between time points (T1, 10.78 fL ± 0.82 vs T2, 10.73 fL ± 0.82 vs T3, 10.74 fL ± 0.87; p = 0.398), for which reason we used the first available MPV in each patient for subsequent analyses. For statistical purposes, we defined 4 MPV quartiles as follows: MPV Q1 (8.7–10.2 fL; n = 152), MPV Q2 (10.3–10.9 fL; n = 158), MPV Q3 (11.0–11.5 fL; n = 128), and MPV Q4 (11.6–14.3 fL; n = 139).

Genetic analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from leukocytes using Gentra Puregene Blood kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Genotyping of 3 SNPs (rs342293, rs1354034, rs7961894) was performed using a real-time PCR allelic discrimination TaqMan 7900 assay (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Genotypes were analyzed using standardized criteria according to the TaqMan Genotyper software (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). The genotype distribution followed the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium for each tested polymorphism and the allele frequency distribution for all polymorphisms was similar to reported frequencies in the Caucasian population (not shown).

For each SNP, 2 groups were considered: patients carrying the wild-type genotype and patients carrying at least 1 allele that was associated with greater MPV in GWAS analyses (C/C genotype vs C/G+ G/G genotypes [G>C variant] in rs342293, C/C genotype vs C/T+ T/T genotypes [T>C variant] in rs1354034, C/C genotype vs C/T+ T/T genotypes [T>C variant] in rs7961894).

Outcome measures

We abstracted admission NIHSS and discharge modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score, which were routinely documented in medical records per institutional protocol by a stroke-trained physician certified in NIHSS and mRS. The discharge mRS was dichotomized to good (mRS score 0–2) vs poor (mRS score 3–6). For patients whose residence was registered in the Krakow district (n = 432; 74.9%), data on all-cause mortality were abstracted from Krakow district death registry. Because mortality data for patients residing outside the Krakow district was unavailable (n = 145; 25.1%), we censored their survival time at the time of the discharge from the hospital.

Statistics

Unless otherwise stated, continuous variables are reported as mean ± SD or median (25th–75th percentile). Categorical variables are reported as proportions. Between-group comparisons for continuous and ordinal variables were made with Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test. Analysis of variance for repeated measures was used to compare the measurements of the same variable performed over time. Unless stated otherwise, the comparisons were made between the participants in the highest quartile (MPV Q4) vs participants in combined quartiles MPV Q1−MPV Q3.

We created multivariable logistic regression models to determine whether the 3 selected SNPs were independently associated with the highest MPV quartile (MPV Q4; dependent variable) after adjustment for age, sex, and factors that were found associated with the highest MPV quartile in univariate analyses at a significance level of p < 0.2.

To determine whether the MPV and selected SNPs were independently associated with the admission NIHSS score (dependent variable), we used multiple linear regression. NIHSS scores were log-transformed to achieve a more suitable distribution for analysis. To determine whether the MPV and selected SNPs were independently associated with a poor discharge mRS score (dependent variable), we used multivariable logistic regression. Finally, survival analysis was performed using Kaplan-Maier method and Cox regression to determine whether the MPV and selected SNPs were related to 1-year mortality (dependent variable). All regression models were adjusted for known factors associated with stroke severity and poor prognosis in patients with ischemic stroke including age, sex, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, CAD, diabetes mellitus, glucose, white blood cell (WBC) and platelet counts, as well as pertinent interaction terms. Models for predicting the discharge outcome and 1-year mortality were additionally adjusted for the admission NIHSS score.

To avoid model overfitting, variables were sequentially removed (likelihood ratio) from the regression models at a significance level of 0.1. Collinearity diagnostics were performed (and its presence rejected) for all multivariable regression models. Model calibration was assessed by Hosmer-Lemeshow test and model fit determined by examining the −2 log-likelihood statistic and its associated χ2 statistics.

Two-sided significance tests were used throughout and unless stated otherwise a 2-sided p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. To calculate corrected levels of significance in cases of multiple comparisons in the univariate analyses of baseline characteristics we used an adjusted p value of <0.01 according to Benjamin and Hochberg.30 Kaplan-Meier analyses across multiple MPV strata were adjusted using Bonferroni correction. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 22 (IBM, Armonk, NY).

Data availability

The investigators will share anonymized data (with associated coding library) used in developing the results presented in this article upon reasonable request to investigators who have received ethical clearance from their host institution.

Results

Study cohort

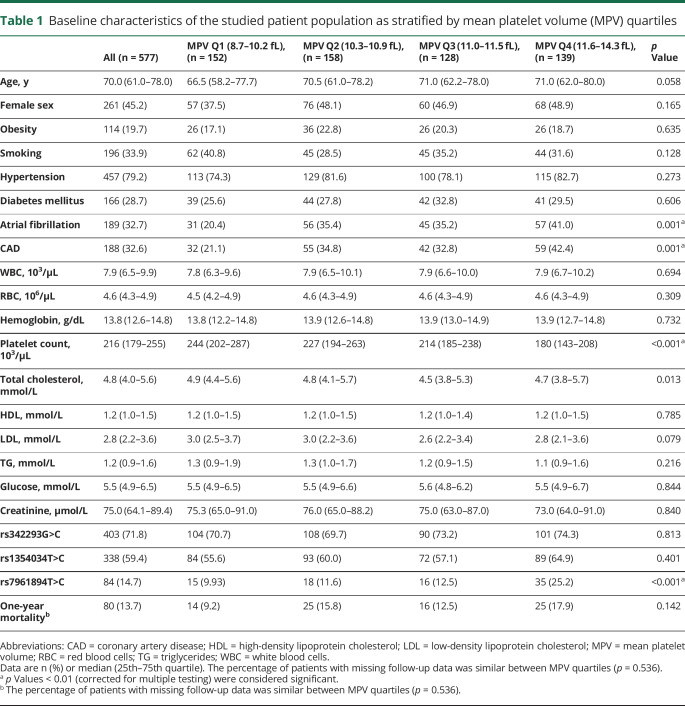

Over the study period, a total of 1,045 patients diagnosed with ischemic stroke were included in our stroke registry. Of these, 577 patients fulfilled the study criteria and had MPV available for analysis and were included for analysis (figure 1). Data were complete for all variables except for missing information on 1-year mortality (n = 145; 25.1%), lipid profile (n = 66; 11.4%), glucose (n = 70; 12.1%), and serum creatinine (n = 51; 8.8%). To allow model adjustment for laboratory data in the entire cohort, we imputed total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, glucose, and creatinine levels by using the cohort median. There was no significant difference in the ratio of missing 1-year mortality data between MPV quartiles (28.9% MPV Q1, 19.6% MPV Q2, 27.3% MPV Q3, 25.2% MPV Q4; p = 0.536). Genotyping was not performed due to insufficient amount of extracted DNA in 7 patients (1.2%) for rs1354034, in 16 patients (2.8%) for rs342293, and in 5 patients (0.9%) for rs7961894. Baseline characteristics of the studied cohort stratified according to the MPV quartiles are summarized in table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the studied patient population as stratified by mean platelet volume (MPV) quartiles

Rs7961894 SNP T>C variant is associated with the highest mean platelet volume quartile

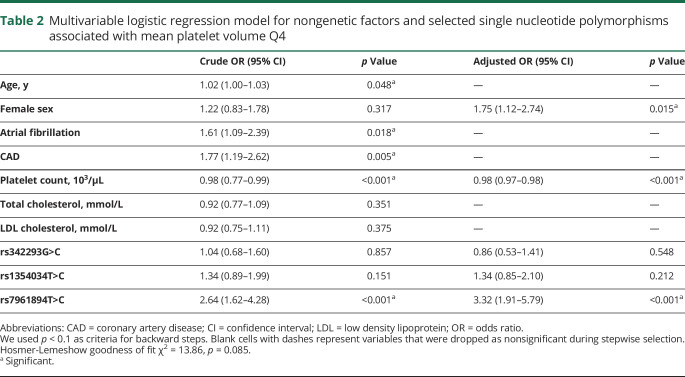

In univariate analyses, older age, presence of atrial fibrillation, CAD, and lower platelet count were associated with MPV Q4 (table 2). Of the tested SNPs, rs7961894 was significantly associated with MPV Q4 (table 2). There was no association between variant G>C of rs342293 and variant T>C of rs1354034 SNPs with MPV Q4 (table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariable logistic regression model for nongenetic factors and selected single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with mean platelet volume Q4

After adjustment for pertinent covariates, variant T>C of rs7961894 SNP was associated with a 3.3-fold greater odds of having an MPV in the highest quartile (table 2). Results did not meaningfully change when the analysis was restricted to cases with complete laboratory data available (n = 492; not shown).

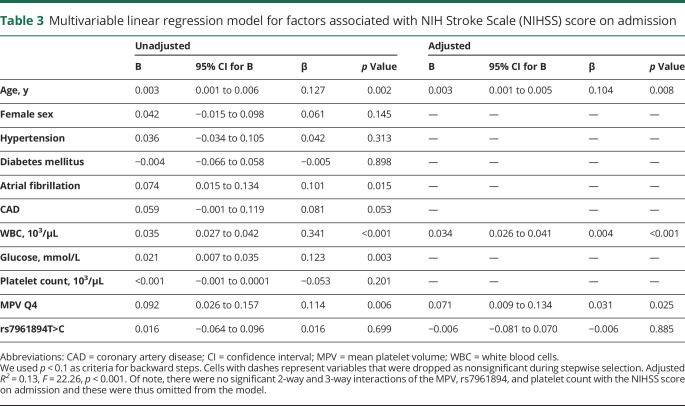

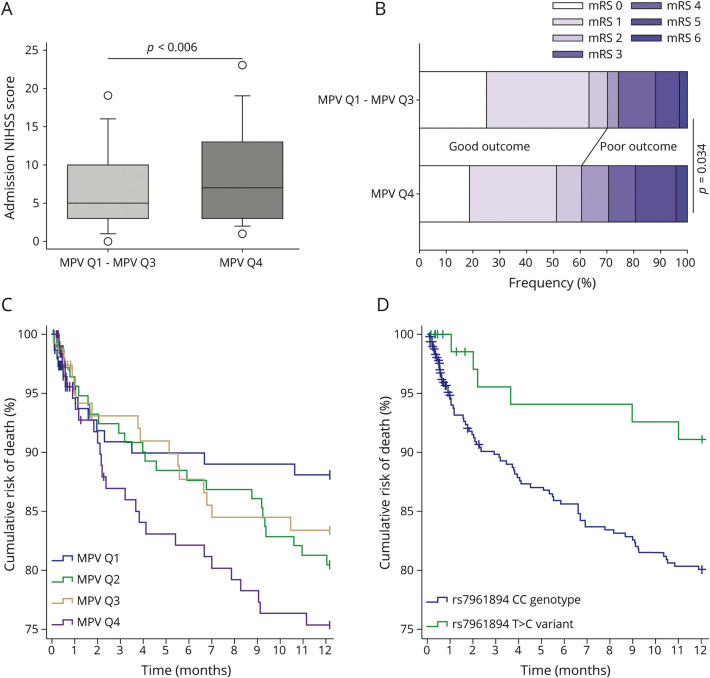

Mean platelet volume relates to a worse admission NIHSS

In univariate analyses, patients with a more severe admission NIHSS were older, more frequently had atrial fibrillation, higher WBC count, and higher glucose level (table 3). Moreover, patients in the MPV Q4 had a significantly greater NIHSS score on admission as compared to all other participants (figure 2A). After adjustment, MPV Q4 remained independently associated with greater admission NIHSS (table 3). There was no association between rs7961894 and admission NIHSS score in both unadjusted and adjusted models (table 3). Similarly, there was no association between variants of rs342293 and rs1354034 SNPs with admission NIHSS (data not shown).

Table 3.

Multivariable linear regression model for factors associated with NIH Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score on admission

Figure 2. NIH Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score on admission, modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score on discharge, and 1-year global mortality as stratified by mean platelet volume (MPV) quartiles.

(A) Patients with MPV Q4 had a significantly higher median NIHSS score on admission as compared to the group with MPV Q1–MPV Q3 (p = 0.006; Mann-Whitney U test). (B) The proportion of patients with a poor discharge mRS was significantly greater among participants in MPV Q4 as compared to participants in MPV Q1–MPV Q3 (p = 0.034; χ2). (C) Patients in MPV Q4 had significantly lower 1-year survival as compared to patients in MPV Q1 (p = 0.033; log-rank test), but this was no longer significant after adjustment for multiple comparisons. Also, there was no significant difference between MPV Q4 and the combined quartiles MPV Q1–MPV Q3 (p = 0.066; log-rank test). (D) Patients carrying variant T>C had a significantly lower 1-year mortality as compared to patients carrying CC genotype of rs7961894 single nucleotide polymorphism (p = 0.029; log-rank test).

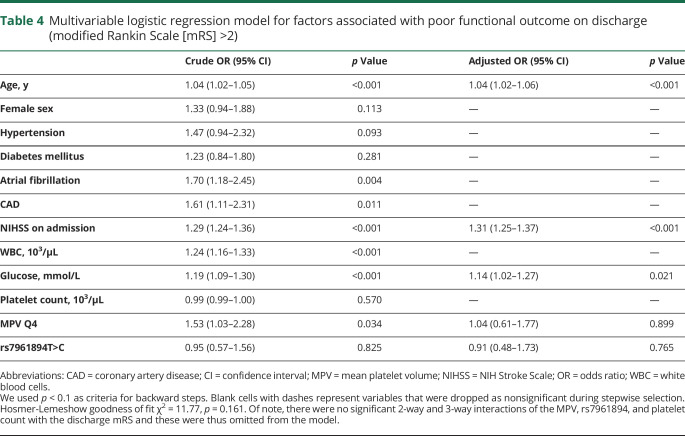

Absent association of the mean platelet volume and rs7961894 with the discharge mRS

Factors associated with poor discharge mRS are presented in table 4. Overall, the proportion of patients with a poor discharge mRS was significantly greater among participants in MPV Q4 as compared to participants in MPV Q1–MPV Q3 (figure 2B). After adjustment for age, sex, cardiovascular risk factors, laboratory data, and admission NIHSS score, neither MPV Q4 nor rs7961894 was independently associated with the discharge mRS (table 4). There was also no association between rs342293 and rs1354034 with poor discharge mRS in our cohort (data not shown).

Table 4.

Multivariable logistic regression model for factors associated with poor functional outcome on discharge (modified Rankin Scale [mRS] >2)

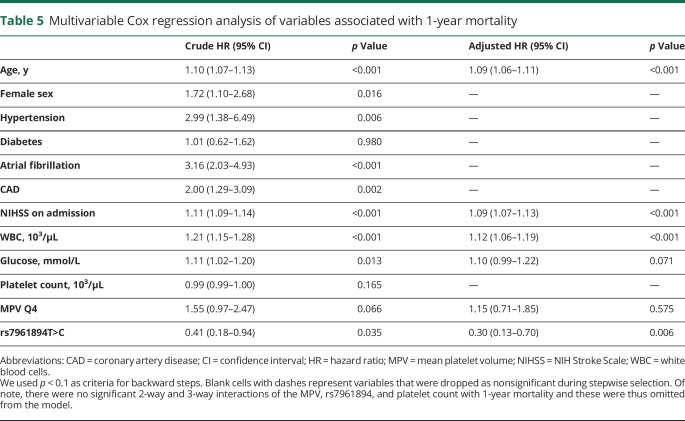

Rs7961894 but not the mean platelet volume relates to 1-year mortality

Kaplan-Meier analysis indicated a significantly greater 1-year mortality among participants in MPV Q4 as compared to MPV Q1, but after adjustment for multiple comparisons across all 4 MPV strata, this difference was lost (figure 2C). Conversely, carriers of rs7961894T>C variant had a significantly lower mortality as compared to patients carrying the CC genotype (figure 2D). On fully adjusted multivariable Cox regression model, rs7961894, age, admission NIHSS, and WBC count, but not the MPV were independently associated with 1-year mortality (table 5). Variants of rs342293 and rs1354034 SNPs were not associated with 1-year mortality (data not shown).

Table 5.

Multivariable Cox regression analysis of variables associated with 1-year mortality

Discussion

We found that the MPV is a marker of stroke severity and that T>C variant of rs7961894 is associated with a decreased 1-year mortality after first-ever ischemic stroke. Specifically, included patients carrying allele T of rs7961894 SNP had an over 3-fold increased risk of having MPV in the highest quartile independent of age, sex, and other (nongenetic) factors previously associated with the MPV such as atrial fibrillation, CAD, and platelet count. This finding is in line with the mounting evidence that platelet parameters, such as the MPV, are in part determined by genetic factors.9–11,31,32 The association of the MPV with rs7961894, located within intron 3 of the WDR66 gene, highlights the general validity of our results as this SNP has been shown to have the strongest association with MPV in multiple GWAS performed in the European population.12–14,16 Moreover, WDR66 gene represents a plausible biological candidate involved in the platelet formation. For example, Meisinger et al.13 noted a significant association between MPV and the levels of the WDR66 transcript. In addition, WDR proteins are thought to play a role in cellular processes such as signal transduction, transcription, and regulation of cell-cycle control and apoptosis.33

Identifying genetic factors associated with MPV is of importance because a greater MPV has been associated with an increased risk of recurrent34 and silent ischemic strokes.35 In our study, we demonstrated that a greater MPV related to a worse stroke severity. In this regard, our results are consistent with previous studies that found worse NIHSS scores among patients with greater MPV.20,21 We expand on these prior observations by showing that greater MPV is an independent marker of stroke severity after adjustment for factors that are associated with stroke severity such as age, atrial fibrillation, and WBC count.36–40 Knowing that platelets’ lifespan is approximately 8–10 days,41 we serially assessed MPV and showed the stability of MPV measurements within 14 days after stoke onset, indicating that the MPV assessed shortly after the stroke likely reflects the premorbid state. Accordingly, presence of an elevated MPV, or genetic risk for larger platelets, may help identify patients at risk for stroke. Indeed, the notion that the MPV may serve as marker of stroke risk is supported by observation that an elevated MPV was associated with thromboembolic complications among patients with atrial fibrillation otherwise considered to be at low risk for thromboembolic complications as assessed by the CHADS2 score.42,43 Similarly, an increased MPV predicted symptomatic plaque in patients with known asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis.44,45 If confirmed in prospective studies, information on the MPV may aid therapeutic decision-making such as choosing the most effective antithrombotic treatment regimen. Indeed, proof-of-principle to support this assertion stems from observations that the MPV inversely correlates with the response to clopidogrel in patients with coronary artery disease.46,47

Interestingly, in our cohort patients who carried at least 1 allele T of rs7961894 SNP, and hence were at risk of greater MPV, had a lower mortality rate within 1 year after ischemic stroke as compared to participants with wild CC genotype of rs7961894. Data regarding the clinical significance of rs7961894 variants are sparse. In one study,48 allele T of rs7961894, in contrast to other MPV-related SNPs, was shown to be associated with lower risk of arterial stiffness. This finding, together with our observation, raises an interesting possibility of pleiotropic effects of the WDR66 gene. For example, molecular pathways affected by rs7961894 may differentially affect MPV and stroke outcomes, which adds to the notion of shared genetic factors between hematologic and other clinical traits.31,49 Our results should be interpreted with caution as we assessed all-cause (but not cause specific) mortality and the subgroup of patients carrying the T>C variant was relatively small (n = 88). In addition, unmeasured confounders, including genetic risks, should be taken into consideration, and our model, due to its simplicity, may be insufficient to elucidate the likely complex relationship between the MPV and stroke-associated mortality.

Consistent with Du et al.,28 we found no significant association between the MPV and short-term poststroke outcome after controlling for initial stroke severity as assessed by the admission NIHSS. This is an important finding because it has been suggested that the MPV may be a marker for increased risk of functional disability after stroke; however, in those studies, NIHSS score was not taken into account.22,23 In other reports, the inclusion criteria were limited to participants undergoing mechanical thrombectomy24 or those who survived 1 year after stroke onset (mRS 0–5).20 Finally, despite a trend toward worse survival in patients within the highest MPV quartile, we did not find an independent association between MPV and 1-year mortality. Our results may be due to the fact that we were not able to evaluate the cause of death in our population. For example, Arévalo-Lorido et al.21 demonstrated that greater MPV was associated with increased risk of cardiovascular death, but not all-cause mortality within 1 year after ischemic stroke.

Strengths of our study relate to the assessment of the MPV as a marker of platelet activity, which is an inexpensive and readily available parameter obtained in all patients presenting with acute ischemic stroke. We used standardized blood draw protocols to mitigate potential confounding related to differences in the processing of samples.50 Furthermore, we showed the stability of MPV measurements in the acute phase of ischemic stroke, assuaging concerns that our results were biased by the timing of MPV assessment. Finally, our study represents one of the largest cohorts in which the association of MPV and pertinent SNPs on stroke-related measures was assessed and analyses were rigorously adjusted for key clinical and laboratory confounders.

Limitations of our study include those inherent to its retrospective design, for which reason results should be considered hypothesis-generating only. Because the normal range and exact values of MPV may vary between laboratories, cutoff values of MPV utilized in our analyses may not fully translate to other settings. We imputed missing data on lipid profile, glucose, and serum creatinine in approximately 10% of included patients, which may have introduced bias. Nevertheless, additional analyses restricted to cases with complete data yielded similar results. Likewise, we had insufficient information on preadmission medications and thus, future studies should account for potential confounding by antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy. Finally, due to administrative limitations, we were unable to determine the cause of death in 25% of cases. However, these patients were censored in our survival analyses and loss to follow-up was similar across MPV quartiles, attenuating concerns that this may have introduced major bias.

The MPV may serve as a readily assessable marker of stroke severity and its genetic variants may be determinants of long-term outcomes in ischemic stroke. Further studies are needed to confirm our findings and to determine whether information gained from the MPV and associated genetic variants could aid therapeutic decision-making.

Glossary

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- GWAS

genome-wide association studies

- LKW

last known well

- MPV

mean platelet volume

- mRS

modified Rankin Scale

- NIHSS

NIH Stroke Scale

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- WBC

white blood cell

Appendix. Authors

Study funding

Supported by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education (Jagiellonian University Medical College core funding for statutory research and development activity, K/DSC/002106).

Disclosure

M. Miller reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. N. Henninger is supported by K08NS091499 from the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke and R44NS076272 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the NIH. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. A. Słowik reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Davi G, Patrono C. Platelet activation and atherothrombosis. N Engl J Med 2007;357:2482–2494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gawaz M, Langer H, May AE. Platelets in inflammation and atherogenesis. J Clin Invest 2005;115:3378–3384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bath PM, Butterworth RJ. Platelet size: measurement, physiology and vascular disease. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 1996;7:157–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamath S, Blann AD, Lip GY. Platelet activation: assessment and quantification. Eur Heart J 2001;22:1561–1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kunicki TJ, Williams SA, Nugent DJ, Yeager M. Mean platelet volume and integrin alleles correlate with levels of integrins alpha(IIb)beta(3) and alpha(2)beta(1) in acute coronary syndrome patients and normal subjects. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2012;32:147–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin JF, Trowbridge EA, Salmon G, Plumb J. The biological significance of platelet volume: its relationship to bleeding time, platelet thromboxane B2 production and megakaryocyte nuclear DNA concentration. Thromb Res 1983;32:443–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jakubowski JA, Thompson CB, Vaillancourt R, Valeri CR, Deykin D. Arachidonic acid metabolism by platelets of differing size. Br J Haematol 1983;53:503–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thompson CB, Eaton KA, Princiotta SM, Rushin CA, Valeri CR. Size dependent platelet subpopulations: relationship of platelet volume to ultrastructure, enzymatic activity, and function. Br J Haematol 1982;50:509–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pujol-Moix N, Vazquez-Santiago M, Morera A, et al. Genetic determinants of platelet large-cell ratio, immature platelet fraction, and other platelet-related phenotypes. Thromb Res 2015;136:361–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whitfield JB, Martin NG. Genetic and environmental influences on the size and number of cells in the blood. Genet Epidemiol 1985;2:133–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson AD. The genetics of common variation affecting platelet development, function and pharmaceutical targeting. J Thromb Haemost 2011;9(suppl 1):246–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gieger C, Radhakrishnan A, Cvejic A, et al. New gene functions in megakaryopoiesis and platelet formation. Nature 2011;480:201–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meisinger C, Prokisch H, Gieger C, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies three loci associated with mean platelet volume. Am J Hum Genet 2009;84:66–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shameer K, Denny JC, Ding K, et al. A genome- and phenome-wide association study to identify genetic variants influencing platelet count and volume and their pleiotropic effects. Hum Genet 2014;133:95–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soranzo N, Rendon A, Gieger C, et al. A novel variant on chromosome 7q22.3 associated with mean platelet volume, counts, and function. Blood 2009;113:3831–3837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soranzo N, Spector TD, Mangino M, et al. A genome-wide meta-analysis identifies 22 loci associated with eight hematological parameters in the HaemGen consortium. Nat Genet 2009;41:1182–1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sansanayudh N, Numthavaj P, Muntham D, et al. Prognostic effect of mean platelet volume in patients with coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Haemost 2015;114:1299–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chu SG, Becker RC, Berger PB, et al. Mean platelet volume as a predictor of cardiovascular risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemost 2010;8:148–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siller-Matula JM, Arbesu I, Jilma B, Maurer G, Lang IM, Mannhalter C. Association between the rs342293 polymorphism and adverse cardiac events in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Thromb Haemost 2014;111:1060–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muscari A, Puddu GM, Cenni A, et al. Mean platelet volume (MPV) increase during acute non-lacunar ischemic strokes. Thromb Res 2009;123:587–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arévalo-Lorido JC, Carretero-Gomez J, Alvarez-Oliva A, Gutierrez-Montano C, Fernandez-Recio JM, Najarro-Diez F. Mean platelet volume in acute phase of ischemic stroke, as predictor of mortality and functional outcome after 1 year. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2013;22:297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greisenegger S, Endler G, Hsieh K, Tentschert S, Mannhalter C, Lalouschek W. Is elevated mean platelet volume associated with a worse outcome in patients with acute ischemic cerebrovascular events? Stroke 2004;35:1688–1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pikija S, Cvetko D, Hajduk M, Trkulja V. Higher mean platelet volume determined shortly after the symptom onset in acute ischemic stroke patients is associated with a larger infarct volume on CT brain scans and with worse clinical outcome. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2009;111:568–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peng F, Zheng W, Li F, et al. Elevated mean platelet volume is associated with poor outcome after mechanical thrombectomy. J Neurointerv Surg 2018;10:25–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ciancarelli I, De Amicis D, Di Massimo C, Pistarini C, Ciancarelli MG. Mean platelet volume during ischemic stroke is a potential pro-inflammatory biomarker in the acute phase and during neurorehabilitation not directly linked to clinical outcome. Curr Neurovasc Res 2016;13:177–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ntaios G, Gurer O, Faouzi M, Aubert C, Michel P. Mean platelet volume in the early phase of acute ischemic stroke is not associated with severity or functional outcome. Cerebrovasc Dis 2010;29:484–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Malley T, Langhorne P, Elton RA, Stewart C. Platelet size in stroke patients. Stroke 1995;26:995–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Du J, Wang Q, He B, et al. Association of mean platelet volume and platelet count with the development and prognosis of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. Int J Lab Hematol 2016;38:233–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care 1997;20:1183–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eicher JD, Lettre G, Johnson AD. The genetics of platelet count and volume in humans. Platelets 2018;29:125–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vasudeva K, Munshi A. Genetics of platelet traits in ischaemic stroke: focus on mean platelet volume and platelet count. Int J Neurosci 2018;129:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neer EJ, Schmidt CJ, Nambudripad R, Smith TF. The ancient regulatory-protein family of WD-repeat proteins. Nature 1994;371:297–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bath P, Algert C, Chapman N, Neal B; PROGRESS Collaborative Group. Association of mean platelet volume with risk of stroke among 3134 individuals with history of cerebrovascular disease. Stroke 2004;35:622–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li B, Liu X, Cao ZG, Li Y, Liu TM, Wang RT. Elevated mean platelet volume is associated with silent cerebral infarction. Intern Med J 2014;44:653–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andersen KK, Andersen ZJ, Olsen TS. Predictors of early and late case-fatality in a nationwide Danish study of 26,818 patients with first-ever ischemic stroke. Stroke 2011;42:2806–2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McGrath ER, Kapral MK, Fang J, et al. Association of atrial fibrillation with mortality and disability after ischemic stroke. Neurology 2013;81:825–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saposnik G, Kapral MK, Liu Y, et al. IScore: a risk score to predict death early after hospitalization for an acute ischemic stroke. Circulation 2011;123:739–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen J, Zhang Z, Chen L, et al. Correlation of changes in leukocytes levels 24 hours after intravenous thrombolysis with prognosis in patients with acute ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2018;27:2857–2862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Furlan JC, Vergouwen MD, Fang J, Silver FL. White blood cell count is an independent predictor of outcomes after acute ischaemic stroke. Eur J Neurol 2014;21:215–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smyth SS, Whiteheart S, Italiano JE, Coller BS. Platelet morphology, biochemistry and function. In: Williams Hematology. Chicago, IL: McGraw-Hill; 2010:1735–1814. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ha SI, Choi DH, Ki YJ, et al. Stroke prediction using mean platelet volume in patients with atrial fibrillation. Platelets 2011;22:408–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bayar N, Arslan S, Cagirci G, et al. Usefulness of mean platelet volume for predicting stroke risk in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation patients. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 2015;26:669–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koklu E, Yuksel IO, Arslan S, et al. Predictors of symptom development in intermediate carotid artery stenosis: mean platelet volume and platelet distribution width. Angiology 2016;67:622–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yilmaz F, Köklü E, Yilmaz FK, Gencer ES, Alparslan AS, Yildirimtürk O. Evaluation of mean platelet volume and platelet distribution width in patients with asymptomatic intermediate carotid artery plaque. Kardiol Pol 2017;75:35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koh YY, Kim YY, Choi DH, et al. Relation between the change in mean platelet volume and clopidogrel resistance in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 2015;13:687–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Asher E, Fefer P, Shechter M, et al. Increased mean platelet volume is associated with non-responsiveness to clopidogrel. Thromb Haemost 2014;112:137–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Panova-Noeva M, Arnold N, Hermanns MI, et al. Mean platelet volume and arterial stiffness: clinical relationship and common genetic variability. Sci Rep 2017;7:40229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Astle WJ, Elding H, Jiang T, et al. The allelic landscape of human blood cell trait variation and links to common complex disease. Cell 2016;167:1429–e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Noris P, Melazzini F, Balduini CL. New roles for mean platelet volume measurement in the clinical practice? Platelets 2016;27:607–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The investigators will share anonymized data (with associated coding library) used in developing the results presented in this article upon reasonable request to investigators who have received ethical clearance from their host institution.