Abstract

This paper reports a study from Cape Town, South Africa, that tested an existing framework of everyday health system resilience (EHSR) in examining how a local health system responded to the chronic stress of large-scale organizational change. Over two years (2017–18), through cycles of action-learning involving local managers and researchers, the authorial team tracked the stress experienced, the response strategies implemented and their consequences. The paper considers how a set of micro-governance interventions and mid-level leadership practices supported responses to stress whilst nurturing organizational resilience capacities. Data collection involved observation, in-depth interviews and analysis of meeting minutes and secondary data. Data analysis included iterative synthesis and validation processes. The paper offers five sets of insights that add to the limited empirical health system resilience literature: 1) resilience is a process not an end-state; 2) resilience strategies are deployed in combination rather than linearly, after each other; 3) three sets of organizational resilience capacities work together to support collective problem-solving and action entailed in EHSR; 4) these capacities can be nurtured by mid-level managers’ leadership practices and simple adaptations of routine organizational processes, such as meetings; 5) central level actions must nurture EHSR by enabling the leadership practices and micro-governance processes entailed in everyday decision-making.

Highlights

-

•

Resilience to chronic stress will prepare health systems to face acute shocks.

-

•

Collective problem-solving and sensemaking enable everyday resilience.

-

•

Distributed leadership, feeling safe and reflective practice are key processes.

-

•

New forms of health system strengthening are needed to nurture resilience.

1. Introduction

Beyond acute disease shocks, such as COVID-19, health systems are faced with persistent, challenging conditions, or chronic stress (Gilson et al., 2017). Such stress can be generated by the reforms commonly deemed necessary to ensure health systems offer better care and address changing health needs (Agyepong et al., 2017; Berman et al., 2019; World Economic Forum, 2019). The institutional adaptations inherent in these reforms (changes in the norms, practices and structures of meaning that influence how people work together: March and Olsen, 2009), inevitably stimulate uncertainty. Centrally-led health reforms may also bring unexpected and unwanted consequences - such as drug supply failures after devolution (Kenya: Tsofa et al., 2017), and weakened health worker motivation due to results-based financing (Zimbabwe: Kane et al., 2019).

Everyday health system resilience (EHSR) has been proposed as the characteristic of complex, adaptive health systems that allows them to respond to chronic stress in ways that transform how they function (Barasa et al., 2017). Prior explorations of EHSR (Gilson et al., 2017; Kagwanja et al., 2020) are among the few empirical analyses of health system resilience (see also Alameddine et al., 2019). Their unusual organizational and institutional analysis (Currie et al., 2012; Swanson et al., 2015) draws attention to the importance of understanding the health system capacities underpinning EHSR.

This paper adds to health system resilience literature by reporting a study that purposefully and prospectively tested the EHSR framework, as is needed to understand the mechanisms that foster organizational resilience (Duchek, 2020). The paper examines how health managers and staff in one local health system within the City of Cape Town (South Africa) responded to parallel, centrally-imposed processes of organizational change and primary health care (PHC) service improvement. Tracing experience over time (2017–18), the paper illustrates the chronic stress generated by these processes, details what response strategies were implemented and explores what factors supported their implementation. More specifically, it analyzes how the local manager's leadership and a set of micro-governance interventions supported stress responses whilst nurturing organizational resilience capacities. Over time, some degree of local health system transformation was observed.

2. Conceptual framework

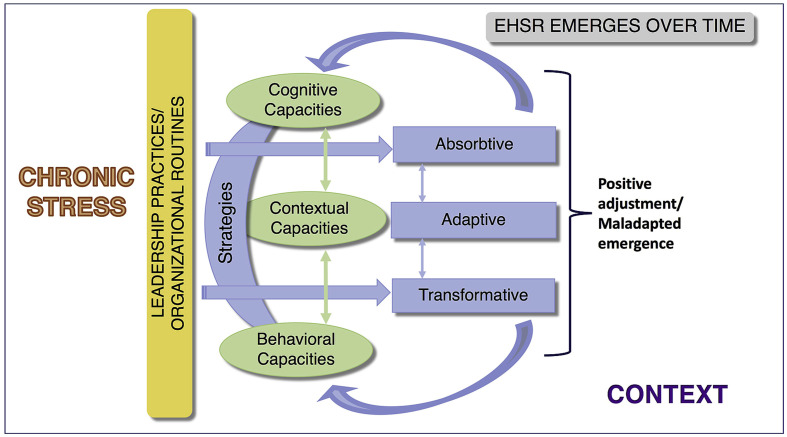

Informed largely by organizational thinking, the EHSR framework (Fig. 1 ) also reflects elements of cross-disciplinary resilience understanding.

Fig. 1.

The everyday health system resilience (EHSR) framework (see separate file).

In contexts of adversity, EHSR is revealed in ‘the maintenance of positive adjustment under challenging conditions such that the organization emerges from those conditions strengthened and more resourceful’ (Vogus and Sutcliffe, 2007: 3418). In all human systems resilience lies in the process of acquiring and sustaining the resources needed to function well under stress, rather than the end state itself (Ungar, 2018; Williams et al., 2017). The EHSR framework suggests that health system responses to chronic stress are implemented through i) a combination of leadership and routine organizational processes (Lengnick-Hall et al., 2011), and take form in ii) strategies of absorption (persistence), adaptation (incremental change), and transformation (longer-lasting systemic change) (Bene et al., 2012).

These responses are, moreover, enabled by iii) the health system's cognitive, behavioral and contextual resilience capacities, which together support it to notice, and be decisive in developing creative responses to, disruptions (Lengnick-Hall et al., 2011; insert link to online file A). Cognitive and behavioral capacities support each other in collective problem-solving and generating a store of possible actions to draw on when responding to stress, together enabling: understanding of environmental developments; making appropriate decisions; and taking necessary action (Duchek, 2020). Contextual capacities, meanwhile, provide the organizational setting in which cognitive and behavioral capacities are enacted and integrated (Williams et al., 2017). They include knowledge, financial, time and human resources, social capital, power and responsibility (Duchek, 2020; Lengnick-Hall et al., 2011; Williams et al., 2017). Together, then, the capacities support the human connectivity, exposure to novel experience, experimentation, reflection and learning more widely recognized as underlying the emergence of resilience (Ungar, 2018). Embedded in open and dynamic systems (Duchek, 2020; Ungar, 2018), the capacities exist pre-stress and are developed through the processes of responding to stress (Williams et al., 2017).

Stress responses generate a combination of iv) positive adjustments and/or undesirable or unsustainable practices (maladapted emergence), that influence health system functionality. As Ungar (2018) notes, recovery from stress is not about bouncing back to the previous normal state, as responding to stress introduces new information into the system. EHSR is instead a measure of how well environmental shocks are integrated and of an individual and collective movement towards a new behavioral state. Rather than being an aggregate of individual resilience, it is derived from the interaction between the health system, system actors and the environment when confronted with stress (Williams et al., 2017).

3. Methods

Building on our prior collaboration this paper's authorial team (a local health manager and researchers) continued to work in cycles of action and reflection over 2017–18. We implemented several micro-governance interventions that sought to strengthen the local health system's resilience capacities, learning from our past work (e.g. Cleary et al., 2018). We tracked their implementation and wider system experience over time, through multiple processes of observation, interviewing and secondary data analysis (see Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Data collected.

| Data collected | By whom |

|---|---|

| Notes & transcripts: 3 in-depth interviews, 2 group discussions Mitchell's Plain senior managers (2017) | LB, UL, & 2 colleagues |

| Transcripts & Notes: 6 reflective conversations with SE (approx. 20 h) (2017–2019); regular informal conversations (2017–18) | LB,LG, UL |

| Researcher diary: observations, 13/16 AMCMs (process, staff participation, discussions, critical incidents, informal conversations) (May 2017–November 2018) (further notes, April 2019) | LB, LG, UL |

| A4MCM minutes: summaries of process & key issues raised, 16/16 meetings (May 2017–November 2018) | LG |

| Think Tank minutes: summaries of process & key issues raised, 22/23 meetings (2017–18) | LG |

| Summaries of feedback from CityHealth Management Team (HMT) meetings to Area South (2017–18) | LG |

| Routine data | Area South staff |

AMCM = Area Management & Communication Meeting.

In analysis, a framework approach to thematic coding was applied across data sets (Ritchie and Spencer, 1994). After initial deductive coding around the four dimensions of the EHSR framework, the emergent themes of experience within each, and within their interactions, were inductively coded. Synthesis around these themes involved triangulation across data sets and generated, first, various descriptive outputs summarizing chronic stress, emergent responses and the interventions. Second, several analytic outputs were developed. A graphical representation of the timeline and intensity of chronic stress in Area South allowed selection of the key stressors discussed here. Analytic narratives considered how the selected stressors impacted on the Area (2017–18), and how the micro-governance interventions supported responses to them and deepened resilience capacities. Summaries of qualitative and quantitative data were developed to explore local health system change over time.

These outputs were, finally, tested and revised through three rounds of validation discussions: within the authorial team; with managers in Area South; and with other City of Cape Town managers. Ultimately, the analytic narrative presented here reflects a synthesized account of experience over time that was crafted from a range of data sets, descriptive and analytic outputs, and has been validated through multiple, iterative processes.

The City of Cape Town municipal authority approved the study and ethics approval was granted by theUniversity of Cape Town, HREC 039/2010.

A potential concern about our approach is that, as a team, we have both led intervention implementation and analyzed the experience. However, roles were partly split - with SE leading implementation and LG, analysis, and we have validated our analysis in several ways. We also offer a detailed report of this experience to promote analytic credibility. SE's own views and experiences are deliberately presented in combination with a range of other data to show how experience changed over time, and to highlight challenges.

4. Findings: Area South experiences 2017-18

We present Area South’s experience through a narrative that considers how it unfolded over time, considering each element of the EHSR framework (Fig. 1).

4.1. Context

Established in 2000, the City of Cape Town (CoCT) municipality has constitutional responsibilities that include promoting a safe and healthy environment. In 2017, concerns about performance weaknesses and future challenges led to large-scale organizational changes intended to ensure a well governed administration better able to pursue its economic and social goals (CoCT , 2017).

Through the Organizational and Development Transformation Plan (ODTP) four geographical Areas were delineated, aligning political and service delivery responsibilities to enhance responsiveness to ‘citizen needs’ (CoCT , 2017: 4). Existing service delivery directorates were consolidated into clusters, supported by transversal finance, assets and corporate services. Finally, a new organizational culture framework sought to promote ‘a culture of Customer-centricity’. Together, these changes were intended to decentralize decision-making ‘to empower those who are responsible for services with the authority for those services and to allow our service offering to be as adaptable and responsive as possible’ (CoCT , 2017: 19).

The changes had particular impacts on CityHealth, the directorate responsible for the provision of PHC and environmental health services. It had previously decentralized considerable decision-making authority to eight health sub-district managers and implemented flexible policies to support community-based work. Through the ODTP, CityHealth was moved into the Social Services cluster, with the authority of its head downgraded, from Executive Director (ED) to Director level. The eight sub-districts were, meanwhile, merged into the four newly-created Areas. New Area managers began work on 1 January 2017, and a new Director, in May 2017. Together they were responsible for navigating CityHealth through the early stages of ODTP implementation whilst strengthening service delivery.

4.2. Chronic stressors

Area South is comprised of two former sub-districts (sds). Mitchell's Plain-sd (MP-sd) includes some of Cape Town's poorest communities, has experienced recent, rapid population growth and, given its population size, is relatively poorly resourced. Southern-sd (S-sd) covers a large geographic area, is home to a population characterized by stark economic divides, and offers PHC services from more, mostly smaller, CityHealth facilities than MP-sd.

Over 2017–18 the Area faced various recurring challenges that presented as chronic stress (chronic stress analysis; researcher diary), with two standing out as most frequently and intensively demanding staff attention: ODTP implementation and directives to improve PHC facility services. Both were exacerbated by the underlying organizational culture.

4.2.1. The ODTP: uncertainty and recentralization

The new Area manager (SE) took up her appointment just after ODTP implementation, a time of great uncertainty - especially in S-sd where managerial transition had been experienced by staff as quite traumatic (interview, July 22, 2017). Previously the MP-sd manager, she also became responsible for over double the number of clinics (25, from 10) and staff (363, from 183 clinic staff; 58, from 28 environmental health staff).

After six months, SE expressed concern about the increased inflexibility of decision-making post-ODTP, ‘sticking to the letter of policies’ and reversing established CityHealth practice (interview, July 22, 2017). After twelve months, she noted the year had been difficult for all staff - getting to know each other in a challenging environment - whilst she had ‘never been so hamstrung in my life … everything has to go through huge numbers of bureaucratic steps. 2 or 3 levels of signatures to get anything done … Everybody's very scared to sign anything… there is constant interference, with no idea how services work’ (interview, January 31, 2018).

Three critical managerial processes became more rigid after the ODTP (Box 1 ), with impacts felt across the Area. First, delays in filling staff vacancies resulting from the centralization of decision-making led to higher workloads for all staff. Second, staff experienced the tighter implementation of the Time and Attendance (T&A) policy (monitoring working hours and practices) as an expression of distrust in them by CoCT management (researcher diary, September 09, 2017; SE interview, August 21, 2019). Third, procurement challenges particularly frustrated PHC facility managers. After one year SE judged that the ODTP ‘just isn't working… there seems to be a dysfunctional mix of decentralization to areas with recentralization [of core management processes]. It was thought that ‘political oversight of a client focused approach could be the driver of change’, but there's been no progress' (interview, January 31, 2018).

Box 1. Re-centralization and rigidity post-organizational change (sources: SE interviews July 22, 2017, January 31, 2018).

1. Staff appointments:

2. Time and Attendance (T&A) policy:

|

Alt-text: Box 1

4.2.2. PHC service delivery pressures

Addressing the apartheid legacy of limited service provision is a long-standing challenge for CityHealth, although over time it has expanded its PHC service package better to meet health needs (Gilson et al., 2014).

2017 brought additional pressures (SE interviews, January 31, July 04, 2018). The Western Cape provincial government added postnatal care (PNC) to its prior request that all CityHealth clinics provide Basic Antenatal Care (BANC). The Executive Mayor's focus on wellbeing and lifestyle placed particular attention on neglected chronic disease services, and the ODTP emphasized general service delivery improvement. National Health Insurance policy proposals stimulated wider quality improvement efforts, as they suggested only facilities meeting quality standards would, in future, be contracted to provide care. The new CityHealth Director encouraged clinics to prepare for NHI by expanding their service package, whilst the Ideal Clinic (IC) program established nationwide quality standards for all facilities. The latter brought additional stress as ‘there is so little room to manoeuvre within the processes’ (SE interview, July 04, 2018). In early 2018, moreover, poor assessments against the IC quality standards led to the concern that any PHC facility not compliant with these standards might be closed (SE interview, January 31, 2018).

4.2.3. Organizational culture

The apartheid legacy of a hierarchical, authoritarian and rigidly, procedural bureaucracy (Von Holdt, 2010), has resulted in passivity and negativity among PHC facility managers, including resistance to the population-focused imperative of PHC improvement (Gilson et al., 2014).

In S-sd there was a ‘culture of acceptance of top down imperatives’ (SE interview, July 02, 2018). In contrast, in MP-sd, there were emerging signs of the organizational re-culturing needed to support PHC improvement - including trust between managers and staff and more pro-active decision-making (MP-sd senior manager interviews, 2017). However, the ‘dominance of bureaucratic management and accountability processes’ that demand compliance with service delivery targets was still an obstacle to maintaining new ways of working in the sub-district (Cleary et al., 2018: ii73).

4.3. Responding to chronic stress

On appointment, the new Area manager immediately sought to offset the ODTP-linked anxieties and build the positive team spirit needed to manage stress and strengthen services (SE interview, July 22, 2017). Drawing on prior experience, she demonstrated enabling leadership practices (MP-sd senior manager interviews, 2017) as well as introducing a set of micro-governance interventions within pre-existing governance structures. These interventions comprised a common set of principles and practices (Box 2 ) embedded within various existing and new regular meetings, and in supervision (support and mentoring (S&M)) visits to PHC facilities (insert link to online file A). Influencing the way all engagements with staff were managed, the principles and practices sought to create safe spaces for reflection, dialogue and learning, as well as to encourage teamwork and shared responsibilities and leadership. The ultimate goal was to nurture collective problem-solving around the Area's challenges and collective responsibility for strengthening services better to meet community needs.

Box 2. The principles and practices of the micro-governance interventions (sources: SE interviews July 22, 2017; July 02, 2018; researcher diary).

Core principles:

1) Rotate meeting chair - to share responsibilities and power 2) Manage time pro-actively- set clear timeframe for meeting/each agenda item; have dedicated timekeeper 3) Rounds - each person makes brief response to common question:

6) Pro-actively looking forward- for example, template for facility-level priority setting asks, for each priority: what would success mean? What actions can be taken to achieve success? And, for periodic reflection, what challenges have been experienced in implementation? 7) Using information pro-actively - to identify problems and support solution development |

Alt-text: Box 2

Although not always easy to manage, the interventions gained traction over time. The Area Management and Communications Meeting (AMCM), attended by all PHC facility and senior managers (for PHC, environmental health services, pharmacy management, administrative and information services), and the ‘Think Tank’, attended only by the senior managers, became anchoring meeting spaces. Within the AMCM, the new meeting processes were sustained over time, albeit with some challenges, and participants became increasingly engaged and active within it (Box 3 ). The Think Tank minutes show that it created a shared space of reflection and support for senior managers that contrasted with their previous experience of isolated working. Early in its life, one manager noted: ‘I love it, it is very on point. You, we have that certain period of time that we're given and we stick to it, and, uhm, if we have any challenges as well then it can be sorted out there and then. And the rest of the team also can offer support and to see, ok, how can we manage this' (interview, October 25, 2017).

Box 3. Reflections on the Area Management & Communication Meeting experience.

Managerial reflections:

|

Alt-text: Box 3

Critically, the new micro-governance interventions enabled engagements among Area staff and managers which, in combination with the Area manager's own leadership, supported the development and implementation of strategies to manage chronic stress.

4.3.1. Absorptive/Adaptive strategies: ‘What's not in our control? How do we buffer?’ (SE interview July 04, 2018)

The rigidity of managerial processes that resulted from ODTP implementation was repeatedly discussed within meetings to support managers in coping with, and adapting to, this challenge.

Within the Think Tank, senior managers shared their frustration at the new directives - and then developed responses. The tightened T&A policy procedures were, for example, discussed in each of the six meetings Nov–Dec2017 (minutes’ analysis) - leading to the development of standard operating procedures (SOPs) for all staff involved in community-level work or required to travel during working hours.

The T&A policy as well as the new staff appointment processes were also discussed in 6/16 AMCM meetings, May2017-Nov2018 (minutes’ analysis). Information was shared and the discussions also supported the development of collective understandings among facility managers around: common problems (e.g. the time taken to fill staff vacancies, July 20, 2017); ways of addressing them (e.g. Area processes for managing vacancies, February 28, 2018); and higher-level guidance (e.g. Area-specific guidance within the T&A policy parameters, for staff legitimately working offsite, November 30, 2017).

The Area manager, meanwhile, continuously encouraged her colleagues to problem-solve. In mid-2017, a new approach to shortlisting candidates was established to reduce appointment delays (SE interview, July 02, 2018). In late 2018, a new, weekly meeting with PHC facility managers encouraged greater understanding and ownership of the T&A policy (especially among newly appointed managers) and generated solutions to the challenges (SE interviews, December 18, 2018, August 21, 2019). In relation to procurement, the Area manager worked closely with other senior managers from the start of the financial year to address facility managers’ needs and avoid losing unspent budget. She also worked up the system, repeatedly raising HR challenges, for example, with the CityHealth Director in one-on-one meetings and wider management meetings, and requesting greater procedural flexibility (HMT report-back, April 04, 2018).

4.3.2. Transformative strategies: ‘What's in our control? How do we do better?” (SE interview July 04, 2018)

Although service improvement pressures came from higher levels, the Area manager saw the ODTP as an opportunity to focus on better meeting population health needs (SE interview, July 22, 2017). By 2017 MP-sd had rolled out the provision of ART and BANC services across 8 out of its 9 clinics, but wider service expansion was needed. S-sd meanwhile had to ‘catch up’ as it did not offer BANC or ART services from the majority of its facilities, which were quite poorly maintained (SE interviews, July 22, 2017, July 02, 2018).

Working through the various Area governance processes, SE sought to develop a collective and transformative response to these service delivery pressures and needs. She wanted to ‘try to create a culture that embeds this question [how to meet the needs of poorer communities] into the routines of the Area as a whole, and to build ownership of it, because it is the right thing to do’ (interview, July 22, 2017). For example, during early 2017 S&M visits to larger S-sd facilities, she asked purposeful questions about the surrounding communities' needs and used facility data to show that expanding services did not imply significant workload increases (interviews, July 22, 2017, January 31, 2018). The 2017 strategic planning meeting then supported managers to identify priority activities for the following year - instead of, as more common, simply complying with centrally-imposed service delivery targets and standards (Cleary et al., 2018). The Area's simple priority-setting template (Box 2) guided managers to think through what they wanted to achieve in their own settings, within broad CityHealth goals, and reflect on how to address implementation challenges (SE interviews, July 22, 2017, July 02, 2018; MP-sd senior manager interviews, 2017). Its repeated use in subsequent AMCM ‘strategic priority’ report-backs only reinforced these new ways of thinking.

Service delivery challenges were also discussed in 9/16 AMCM meetings alongside service, budget and staffing data (minutes analysis, May2017-Nov2018), with the aim of developing the collective mindset that ‘service change is possible’ (SE Interview July 22, 2018). Three dedicated AMCM discussions (Aug–Sept 2017, April 2018; insert link to online file A) focused on service expansion. The researcher diary identified some challenges in the way these discussions were structured (see also Box 3), and that facility managers had not clearly engaged their own staff about the issues; but, over time, managers became more active in the meetings. For example, in September 2017 one small group considered geriatric service provision challenges: ‘[the] discussion throws up quite a few ideas; and the suggestion that ‘we need to talk more with each other’; it was a good discussion’ (researcher diary, September 27, 2107). In April 2018, moreover, the managers compared the difficult, but successful, roll-out of PNC with the failure to provide geriatric care and identified steps to strengthen future service expansion (AMCM minutes). Finally, repeated discussion within the AMCM and Think Tank of PHC facility staffing challenges (minutes' analysis) informed the location of new pharmacy posts - and by April 2018 improvements in pharmacy support were noted (researcher diary).

AMCM service delivery discussions were followed-up in SE's one-on-one meetings with other senior managers, who in turn followed up with PHC facility managers and doctors. A dedicated manager was also assigned to support facility managers in preparing for IC assessments in 2017. In 2018, S&M visits focused on encouraging staff in larger facilities to think how to improve towards IC standards, although SE was concerned that an audit, rather than supportive, supervision style was applied (interviews, July 04, 2018, August 21, 2019).

The final element of response to service delivery stressors was, again, the Area manager's own leadership. She repeatedly raised the challenges of expanding and strengthening service provision and the need for more resources with the CityHealth Director and colleagues. MP-sd, in particular, fell short of the City-wide staffing norms for providing comprehensive services (researcher diary, September 27, 2017). The CityHealth Director also engaged up the system to press the case for more resources. From January 2018 all CityHealth Areas received additional annual capital budgets for minor upgrades/equipment to support IC implementation (representing a more than 40-fold increase in the Area budget). Other once-only budgetary increases were also received, including from reallocating unspent budgets from elsewhere in the Social Services Cluster.

4.4. How did the micro-governance interventions nurture the resilience capacities?

As well as supporting the implementation of stress response strategies, the micro-governance interventions nurtured and deepened the inter-linked EHSR capacities (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

How the micro-governance interventions developed the resilience capacities.

| Cognitive capacities | Behavioral capacities | Contextual capacities |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention names signal positive and constructive orientation, intended to influence understanding of purpose (constructive sensemaking) Examples: ‘strategic planning’ as pro-active & forward looking; communication central to management (AMCM); ‘support & mentoring’ rather than audit visits |

Across interventions, new useful habits (e.g. Box 2) bring positivity to discussions, allow collaborative thinking, & support reflection/learning (for AMCM, Think Tank, includes reflection about them) - and commonly represent counter-intuitive acts, requiring the unlearning of dysfunctional behaviors (usual routines) |

Deliberate actions taken to generate the psychological safety enabling staff engagement in meetings Examples: the AMCM/Think Tank allow uncertainties and concerns to be shared (SE interview, July 02, 2018); preparation for meetings (e.g. through the Think Tank for the AMCM); use of positive rounds & appreciation (useful, practical habits, Box 2) liked by staff (MP-sd senior manager interviews, 2017) |

| Specific intervention features support constructive sensemaking, i.e. being pro-active and reflective Examples: establishing timelines for follow-up after supervision and mentoring visits; embedding statement of purpose in AMCM Agenda |

Bringing together teams cutting across organizational/professional silos & hierarchies within interventions both a useful, practical habit & key mechanism to enable collaborative inquiry and reflection (feeding back into cognitive capacities' development) | Approaches to diffusing power and accountability embedded in interventions (Box 2), offset view that facility managers have limited decision-making role (SE interview, July 22, 2017) |

| By engaging staff groups, interventions supported development of shared mindsets towards collective problem-solving & population-orientation; and sustained the interventions | Some interventions (strategic planning, AMCM & Think Tank) supported the development of learned resourcefulness and creative ingenuity (reflected in the stress responses) | Various intervention routines (Box 2), together with respectful engagement (a useful habit), enabled social capital development - relationships within organization, that, in turn, support collective working. |

| Interventions supported being prepared - both by unlearning & being ready to take advantage of emerging situations Example: pro-active engagement with health information data across interventions demonstrated that service expansion was possible, & encouraged data use (SE interviews, July 22, 2017, January 31, 2018). |

AMCM = Area Management & Communication Meeting.

At one level, the interventions worked to counter the underlying organizational culture resisting PHC improvement. The priority-setting template (Box 2), for example, supported local goal-setting over compliance with targets from higher levels, whilst, for the Think Tank, ‘the name is important as it frames the meeting. We don't think normally’ (SE interview, July 02, 2018). Unlearning dysfunctional behaviors (behavioral capacity) was necessary and difficult. Simply not having an agenda for the Think Tank was unusual; and, in the AMCM it took months to give up the habit of reviewing the previous meeting's minutes and checking off matters arising (researcher diary).

At the same time, Area South managers and staff were regularly brought together to pro-actively manage chronic stress by thinking and planning across organizational/professional silos and hierarchies (contextual capacity). This teamworking provided opportunities for collective reflection and problem-solving through positive and constructive sensemaking (cognitive capacity), enabling collective inquiry (behavioral capacity) and the development of the shared mindsets (cognitive capacity) underpinning implementation of response strategies. Using the priority-setting template, for example, encouraged pro-active and forward-looking mindsets (cognitive capacity). Meanwhile, being prepared (behavioral capacity), through discussing how to use additional staff and capital resources in the AMCM and Think Tank, enabled decision-making. The intervention names (e.g. Think Tank) also encouraged a pro-active orientation (cognitive capacity). Finally, the useful practical habits (Box 2) introduced into the meetings worked to support development of strong, positive organizational relationships (behavioral capacity), as well as to diffuse power and enhance a willingness to share concerns among staff groups (contextual capacities).

The deepening of collective capacities over time was illustrated by researcher observations of the AMCM (Box 3). Facility managers themselves also noted that these meetings became more useful over time (researcher diary, July 26, 2018 ). By the end of 2018 they were: ‘… engaging and speaking up even in discussions… Each group have taken exercise really seriously and thought carefully. Discussions allow groups to learn from each other…. Lots of engagement and thought, laughter… Good example of sensemaking process’ (researcher diary, November 29, 2018).

The interventions were not, however, instrumental in developing the relationships through which additional resources were secured (contextual capacity). Instead, the Area manager and CityHealth Director used their formal, bureaucratic relationships to argue for relaxing constraining procedures and additional resources. The wider context also supported additional resource allocations. SE noted, for example, that being part of a broader service cluster post-ODTP enabled CityHealth's access to unspent resources in other Social Service departments (interview, December 18, 2018). Ultimately, additional resources brought some slack to the system, including positivity, which itself supported service expansion and improvement.

4.5. What are the signs of system resilience emerging over time?

At the end of 2018, the story of Area South was still unfolding. However, three signs of system resilience were noted - indications that it had emerged from the 2017–18 period in a new behavioral state, ‘strengthened and more resourceful’ (Vogus and Sutcliffe, 2007: 3418).

First, an Area-wide team had developed - who had good relationships, a largely positive outlook, and who pro-actively engaged in problem-solving. Whereas in July 2017 there was a clear sense of ‘us and them’ in the AMCM between the two sub-district staff groups, by November 2017 there was a ‘ … real sense of positivity, team spirit in Area as a whole… ‘unity, coming together as a district’, ‘can see we now are moving forwards as one’’ (researcher diary, November 30, 2017). Just getting through the first year provided the platform of relationships on which to move forward: ‘we survived the year and don't feel deflated. In fact, we are stronger’ (SE interview January 31, 2018). Yet whilst progress had been made in S-sd, challenges had emerged in MP-sd (SE interview January 31, 2018); but by July 2018 SE judged that her team was working better across their silos and that staff were more relaxed in meetings (interview, July 02, 2018; Box 3). The emergence of a strong, pro-active team was demonstrated at year end. In the face of funding and bureaucratic challenges, the facility managers themselves organized the annual staff awards ceremony which they judged very important for staff morale. From her vantage point, the CityHealth Director also noted that ‘things are done differently in Area South’, with positive service delivery consequences.

Second, by 2019, nearly three years after its implementation, SE judged that the impacts of the ODTP on core management processes had been managed (interview, August 21, 2019). Various system adjustments had been implemented to support organizational functioning. These included changes in human resource management processes that brought the system back to pre-ODTP practices (e.g. authority delegations allowing the CityHealth Director to approve staff shortlists and appointments: AMCM minutes, September 27, 2018) or strengthened practice by distributing responsibility more widely (e.g. for T&A policy implementation). New procurement practices also represented an improvement on the past - leading, for example, to improved maintenance of S-sd facilities.

Third, cross-facility discussions at the AMCM appeared to have enabled staff commitment to PHC improvement and, with additional resourcing, service extension. By Jan 2018 SE judged that a culture of talking about needs and priorities was emerging, even at facility level and despite weak engagement of staff by managers. S-sd staff were, in particular, feeling more valued (SE interview January 31, 2018). In July 2018, she noted that AMCM discussions had allowed managers to share experience, learn from each other, review the relevant data and begin ‘thinking that it is possible’, rather than resisting the top-down instruction to implement new services (SE interview, July 02, 2018). This was confirmed by the PHC facility managers, who observed in the July 2018 AMCM that many of the issues previously discussed had been implemented. This included BANC and PNC provision, ART in some clinics, as well as geriatric screening in some places, hypertension and diabetes care (researcher diary, July 26, 2018). Routine data support these assessments (Table 3 ) - and demonstrate that further efforts were needed in S-sd, in particular, as well for chronic services across the Area.

Table 3.

Number of facilities offering additional services, by sub-district (source: routine data, Area South).

| Anti-retroviral therapy | Basic Ante-natal care | Post-natal care | Chronic care | Hypertension Screening |

Diabetes screening | Geriatric care | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MP-sd (9 facilities) | |||||||

| Before ODTP | 8 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| After ODTP | 1 | 1 | 9 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 9 |

| S-sd (15 facilities) | |||||||

| Before ODTP | 4 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| After ODTP | 10 | 11 | 15 | 4 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

ODTP = Organizational Development and Transformation Plan.

The IC programme may also have supported PHC improvement. SE judged that it had encouraged Area-wide review and reflection, including peer support (interview, July 04, 2018). However, it imposed considerable stress on PHC facility managers and had required direct support from the Area level. She was also concerned about its potential to generate 'maladapted emergence' (SE interview, July 04, 2018). Its audit and compliance approach, for example, might have demotivated staff - especially because some established targets simply could not be achieved. It also encouraged compliance above improvement (e.g. leading equipment to be moved between facilities during the audit process, to meet standards). In resilience capacity terms, then, it is possible that the IC process may have directed learned resourcefulness towards managing short-term needs, as well as crowded out the creative ingenuity and other cognitive capacities required to enable sustained service transformation over the long term.

5. Discussion

This analysis of a South African meso-level health system illuminates the chronic stress generated by centrally-led, large-scale organizational change. In Area South, as elsewhere (Roman et al., 2017), a re-structuring that ostensibly sought to decentralize decision-making to those responsible for service delivery, actually entailed a centralization of authority. In this case, it intensified the pre-existing hierarchical and rigidly procedural organizational culture. The re-structuring was accompanied by multiple policy demands to expand and improve PHC services. Responding to the twin pressures of organizational change and service improvement within a constraining organizational culture placed huge burdens on frontline staff and managers, even as positive adjustments were observed. It is also unclear what level of PHC improvement could have been achieved in this period without the burdens of organizational change.

Such persistent, challenging conditions, chronic stress, are an everyday reality of health systems. They include changing patient expectations and demands, staff absenteeism, budgetary constraints, cross-level managerial tensions and the politicization of health system experience (Felland et al., 2003; Gilson et al., 2017; Kagwanja et al., 2020; ; Lembani et al., 2018). Health systems manage these chronic stressors even as they seek to improve. Consequently, they face the challenge of how to respond to chronic stress in ways that enable transformative systemic change, rather than bouncing back to a prior state of weak functionality. This is the system characteristic termed everyday health system resilience (Barasa et al., 2017).

Purposefully testing the EHSR framework in analyzing Area South’s experience offers five sets of insights that add to the limited empirical knowledge base, and address the knowledge gap around needed organizational and leadership capacities (Williams et al., 2017).

First, this analysis illuminates the theoretical insight that resilience is a process (Duchek, 2020; Ungar, 2018; Williams et al., 2017) by presenting a chronological, narrative analysis of institutional change over time in one relatively small-scale health system. As shown here, institutionalizing the new principles and practices intended to nurture collective problem-solving and collective responsibility for service improvement occurred took time. By 2019 there was evidence and wider recognition that Area South had nurtured a stronger collective approach to tackling challenges, with positive impacts on PHC service provision. However, the foundations for this change lie in earlier rounds of action research supporting new practices of reflection, learning and distributed leadership within one part of the Area's health system (Cleary et al., 2018; Gilson et al., 2017). In addition, alongside the positive adjustments observed were some hints of the possible ‘dark side’ of resilience (Gilson et al., 2017; Kagwanja et al., 2020; Williams et al., 2017). These included the burdens borne by all staff in responding to change, possible opportunity costs in terms of PHC improvements and concerns about the Ideal Clinic program. Resilience, like institutional change, is, then, an emergent and dynamic process (Alameddine et al., 2019).

Second, Area South’s experience confirms other studies' conclusions that response strategies do not linearly evolve from absorption through adaptation to transformation but are deployed at the same time. They may, as in this experience, address different stressors, or be deployed against the same stressor by different actors (Kagwanja et al., 2020) or, as suggested here and by Alameddine et al. (2019), be relevant to different time horizons (with transformative strategies supporting more fundamental, longer-term change). Importantly, however, as previously noted (Gilson et al., 2017), absorption of stress by individuals does not itself demonstrate the collective resilience entailed in EHSR.

Third, this analysis deepens understanding about the system capacities that are entailed in resilience. They not only support the processes broadly recognized to contribute to resilience - such as anticipation, coping and adaptation (Duchek, 2020), or persistence, resistance, recovery, adaptation and transformation (Ungar, 2018) - but also, as demonstrated in Area South, enable the unlearning of dysfunctional organizational behaviors.

The contextual capacities supporting EHSR include organizational relationships and networks that can be nurtured through leadership practices that bring people together across organizational silos, as in the AMCM and Think Tank (itself, unlearning). The Area South experience also illustrates the importance of diffused power (Kagwanja et al., 2020), and emphasizes the need, to nurture an enhanced sense of safety to speak up and take risks in such spaces (again, unlearning) (Chamberland-Rowe et al., 2019). Research on organizational culture and improving clinical outcomes in hospitals, similarly, points to the role of leaders in fostering a learning environment, ensuring that staff feel psychologically safe and able to speak up when things go wrong; as well as deliberate management of conflict and motivation, and enabling coalitions across disciplines and levels of the hierarchy (Mannion and Smith, 2018).

In addition, the Area South experience illuminates the theoretical understanding (Williams et al., 2017) that contextual features both enable the development of, and, as shown empirically (Kagwanja et al., 2020), are integrally linked with, other resilience capacities. For example, nurturing teamwork within the Area provided the context that enabled the development of collective sensemaking and the problem-solving behaviors also needed to implement stress responses. Collaboration between managers and researchers, meanwhile, supported a continuing process of action-learning that itself nurtured other resilience capacities. As Sharp et al. (2018) argue, appreciative action research enables change in mindsets and relationships, hopefulness in the face of complex demands, a new language that expands opportunities, as well as nurturing ownership of ideas (see also Gilson et al., 2017; Kagwanja et al., 2020; Tetui et al., 2017).

These cognitive and behavioral resilience capacities were, moreover, purposefully nurtured by the micro-level governance interventions introduced in Area South. Although challenges were experienced, new practical habits were sustained over time and reinforced by spreading to new meeting spaces. These simple adaptations of meetings and supervisory engagements supported relationship-building, collective sensemaking, shared mindsets of problem-solving, creativity, and underpinned the implementation of stress responses. The new practices stimulated positivity, spread power, enabled engagement, and provoked new ways of thinking. They also, as noted, supported the unlearning of some old ways of being - such as working in silos, managerial passivity and the tendency to wait for instructions from above.

Although the particular role of sensemaking in producing or inhibiting change, and in enabling new ways of organizing, is acknowledged in wider literature (Maitlis and Christianson, 2014), there are few reported health system experiences. Jordan et al. (2009), for example, consider the role of impromptu conversations in supporting sensemaking and encouraging self-organization among agents within US primary care. They suggest that the work of organizational change is not about designing new structures but about introducing new themes into organizational conversations. Confirming the Area South experience, they argue that local managers can enable such conversations by creating time and space where they can unfold, as well as supporting conversations that allow people to manage uncertainty and re-shape relationships. Such conversations may, then, support the collective mindfulness thought to fuel organizational resilience (Williams et al., 2017).

Fourth, addressing a recognized knowledge gap (Williams et al., 2017), Area South’s experience confirms the importance of distributed leadership for EHSR (Gilson et al., 2017). Mid-level managers are themselves in a critical position to nurture resilience capacities. Situated between the centre and the frontline, they can clarify central visions and directions, support collective sensemaking and coordinate integrated responses when instability arises (Chamberland-Rowe et al., 2019; Rouleau, 2005). Canadian health reform experience illustrates this important conceptual work, highlighting mid-level managers' role in building relationships, trust and collaboration to support implementation (Cloutier et al., 2016).

As shown in Area South, mid-level managers can role-model leadership practices that both deepen the health system software recognized as important for resilience (Gilson et al., 2017; Kagwanja et al., 2020) and distribute leadership. Listening, being respectful, allowing others to lead and creating spaces for learning from experience are important practices of leadership in complexity and for resilience (Belrhiti et al., 2018; Petrie and Swanson, 2018). These practices can strengthen the commitment and motivation of staff to innovate, learn, adapt and transform. In addition, the Area South manager did two other things acknowledged to support resilience in complex systems (Chamberland-Rowe et al., 2019; Petrie and Swanson, 2018). Alongside the CityHealth Director, she worked up the bureaucracy to leverage some slack in the system - specifically, a relaxation in compliance demands and additional resources for PHC improvement - and she pro-actively sought to use data to nurture system awareness.

Fifthly, these experiences offer pointers to the forms of central level action needed to nurture EHSR. Commonly, health system strengthening is seen as a centrally-led initiative (e.g. Berman et al., 2019) and some argue that purposeful reform design can generate relevant institutional change (e.g. Bertone and Meessen, 2013). Others argue that building system robustness is the first step to resilience - perhaps by creating the organizational, legal and regulatory environments that enable adaptability at meso and micro levels (Chamberland-Rowe et al., 2019). However, complexity theory and wider experience suggests that reform design cannot by itself direct institutional change (Cloutier et al., 2016), and the sequencing of top-down/bottom-up action is less important than paying attention to both (Swanson et al., 2015). Central level actions must enable complex health systems to self-organize towards agreed goals. Such actions could include: adapting the boundary conditions influencing the system (Petrie and Swanson, 2018) e.g. in Area South, relaxing compliance demands and resource challenges; decentralizing authority, unlike in Area South, to allow local level leaders to reward experimentation (Cloutier et al., 2016); and, as demonstrated in Area South, supporting the development of relational leadership skills among future mid-level and senior managers (Gilson and Agyepong, 2018). Unlike centrally-led, large-scale governance reform, these actions seek to strengthen health systems by enabling the micro-governance processes and leadership practices underpinning everyday decision-making.

6. Conclusions

This paper illuminates the dynamic nature of health systems and the chronic stress they routinely carry. It confirms previous insights about EHSR - recognizing it as a process encompassing multiple strategies, and acknowledging responses to stress that both nurture and may harm system functionality. It adds insights about the critical role of mid-level managers in spreading leadership - and, importantly, about the micro-governance interventions such managers can introduce to nurture resilience capacities. These lynchpin figures play critical roles in nurturing resilience. The paper, then, also calls for new forms of centrally-led action that include the development of system-wide leadership to seed and sustain innovation in the micro-practices of governance. Nurturing everyday health system resilience and sustaining transformative change demands combined bottom-up and top-down action.

Credit author statement

Lucy Gilson: Conceptualization, Methodology, analysis, Investigation, Writing - original draft; Soraya Ellokor: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing - review & editing; Uta Lehmann: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - review & editing; Leanne Brady: Conceptualization, Methodology, analysis, Investigation, Writing - review & editing.

Acknowledgements

We thank the heath staff and managers of Area South for their continued dedication and commitment to the people of Cape Town - and their support for this work. We thank our colleagues in the Resilient and Responsive Health Systems, RESYST, Consortium for their support and engagement. This research is an output of RESYST, which was funded by the UK Aid from the Department for International Development (DFID) for the benefit of developing countries. However, the views expressed and information contained in it are not necessarily those of or endorsed by DFID, which can accept no responsibility for such views or information or for any reliance placed on them.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113407.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Agyepong I.A., Sewankambo N., Binagwaho A., Coll-Seck A.M., Corrah T., Ezeh A., Piot P. The path to longer and healthier lives for all Africans by 2030: the Lancet Commission on the future of health in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet. 2017;390:2803–2859. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31509-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alameddine M., Fouad F.M., Diaconu K., Jamal Z., Lough G., Witter S., Ager A. Resilience capacities of health systems: accommodating the needs of Palestinian refugees from Syria. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019;220:22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barasa, E. W., Cloete, K., Gilson, L. 2017. From bouncing back, to nurturing emergence: reframing the concept of resilience in health systems strengthening. Health Pol. Plan., 32(suppl_3), iii91-iii94, 10.1093/heapol/czy052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Belrhiti Z., Giralt A.N., Marchal B. Complex leadership in healthcare: a scoping review. Int. J. Health Pol. Manag. 2018;7:1073–1084. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2018.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bene C., Godfrey-Wood R., Newsham A., Davies M. 2012. Resilience: New Utopia or New Tyranny? Reflection about the Potentials and Limits of the Concept of Resilience in Relation to Vulnerability Reduction Programmes.http://www.ids.ac.uk/publication/resilience-new-utopia-or-new-tyranny IDS Working Paper, issue 405. [Google Scholar]

- Berman P., Azhar A., Osborn E.J. Towards universal health coverage: governance and organisational change in ministries of health. BMJ Glob. Heal. 2019;4 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertone M.P., Meessen B. Studying the link between institutions and health system performance: a framework and an illustration with the analysis of two performance-based financing schemes in Burundi. Health Pol. Plann. 2013;28:847–857. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberland-Rowe C., Chiocchio F., Bourgeault I.L. Harnessing instability as an opportunity for health system strengthening: a review of health system resilience. Healthc. Manag. Forum. 2019;32:128–135. doi: 10.1177/0840470419830105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary, S., Toit, A. D., Scott, V., Gilson, L. 2018. Enabling relational leadership in primary healthcare settings: lessons from the DIALHS collaboration. Health Pol. Plan., 33(suppl_2), ii65-ii74, 10.1093/heapol/czx135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cloutier C., Denis J.L., Langley A., Lamothe L. Agency at the managerial interface: public sector reform as institutional work. J. Publ. Adm. Res. Theor. 2016;26:259–276. doi: 10.1093/jopart/muv009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- CoCT (City of Cape Town) 2017. Organisational Development and Transformation Plan.http://resource.capetown.gov.za/documentcentre/Documents/City%20strategies,%20plans%20and%20frameworks/Organisational%20Development%20and%20Transformation%20Plan%20(ODTP).pdf Cape Town. [Google Scholar]

- Currie G., Dingwall R., Kitchener M., Waring J. Let's dance: organization studies, medical sociology and health policy. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012;74:273–280. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchek S. Organizational resilience: a capability-based conceptualization. Bus. Res. 2020;13:215–246. doi: 10.1007/s40685-019-0085-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Felland L.E., Lesser C.S., Benoit Staiti A., Katz A., Lichiello P. The resilience of the health care safety net, 1996-2001. Health Serv. Res. 2003;38:489–502. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00126. 1 Pt 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilson, L., Barasa, E., Nxumalo, N., Cleary, S., Goudge, J., Molyneux, S., ... & Lehmann, U. (2017). Everyday resilience in district health systems: emerging insights from the front lines in Kenya and South Africa. BMJ Glob. Health, 2, e000224, 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gilson L., Agyepong I.A. Strengthening health system leadership for better governance: what does it take? Health Pol. Plann. 2018;33:ii1–ii4. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czy052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilson L., Elloker S., Olckers P., Lehmann U. Advancing the application of systems thinking in health: South African examples of a leadership of sensemaking for primary health care. Health Research Policy and Systems. 2014;12(30) doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-12-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan M.E., Lanham H.J., Crabtree B.F., Nutting P.A., Miller W.L., Stange K.C., McDaniel R.R. The role of conversation in health care interventions: enabling sensemaking and learning. Implement. Sci. 2009;4:15. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagwanja N., Waithaka D., Nzinga J., Tsofa B., Boga M., Leli H., Mataza C., Gilson L., Molyneux S., Barasa E. Shocks, stress and everyday health system resilience: experiences from the Kenyan coast. Health Pol. Plan. 2020;35(5):522–535. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czaa002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane S., Gandidzanwa C., Mutasa R., Moyo I., Sismayi C., Mafuane P., Dieleman M. Coming full circle: how health worker motivation and performance in results-based financing arrangements hinges on strong and adaptive health systems. Int. J. Health Pol. Manag. 2019;8:101–111. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2018.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lembani M., De Pinho H., Delobelle P., Zarowsky C., Mathole T., Ager A. Understanding key drivers of performance in the provision of maternal health services in eastern cape, South Africa: a systems analysis using group model building. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018;18:912. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3726-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengnick-Hall C.A., Beck T.E., Lengnick-Hall M.L. Developing a capacity for organizational resilience through strategic human resource management. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2011;21:243–255. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2010.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maitlis S., Christianson M. Sensemaking in organizations: taking stock and moving forward. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2014;8:57–125. doi: 10.5465/19416520.2014.873177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mannion R., Smith J. Hospital culture and clinical performance: where next? BMJ Qual. Saf. 2018;27:179–181. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March J.G., Olsen J.P. The logic of appropriateness. In: Rein M., Moran M., Goodin R.E., editors. Oxford Handbook of Public Policy. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2009. pp. 689–708. [Google Scholar]

- Petrie D.A., Swanson R.C. The mental demands of leadership in complex adaptive systems. Healthc. Manag. Forum. 2018;31:206–213. doi: 10.1177/0840470418778051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie J., Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman A., Burgess R., editors. Analyzing Qualitative Data. 1994. pp. 173–194. Routledge, London. [Google Scholar]

- Roman T.E., Cleary S., McIntyre D. Exploring the functioning of decision space: a review of the available health systems literature. Int. J. Health Pol. Manag. 2017;6:365–376. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2017.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouleau L. Micro-practices of strategic sensemaking and sensegiving: how middle managers interpret and sell change every day. J. Manag. Stud. 2005;42:1413–1441. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2005.00549.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp C., Dewar B., Barrie K., Meyer J. How being appreciative creates change – theory in practice from health and social care in Scotland. Action Res. 2018;16:223–243. doi: 10.1177/1476750316684002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson C.C., Atun R., Best A., Betigeri A., de Campos F., Chunharas S. Strengthening health systems in low-income countries by enhancing organizational capacities and improving institutions. Glob. Health. 2015;11:5. doi: 10.1186/s12992-015-0090-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetui M., Coe A.B., Hurtig A.K., Bennett S., Kiwanuka S.N., George A., Kiracho E.E. A participatory action research approach to strengthening health managers' capacity at district level in Eastern Uganda. Health Res. Pol. Syst. 2017;15:100. doi: 10.1186/s12961-017-0273-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsofa B., Goodman C., Gilson L., Molyneux S. Devolution and its effects on health workforce and commodities management - early implementation experiences in Kilifi County, Kenya Lucy Gilson. Int. J. Equity Health. 2017;16:169. doi: 10.1186/s12939-017-0663-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungar M. Systemic resilience: principles and processes for a science of change in contexts of adversity. Ecol. Soc. 2018;23(4) doi: 10.5751/ES-10385-230434. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vogus T.J., Sutcliffe K.M. 2007 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics. IEEE; Montreal: 2007. Organizational resilience: towards a theory and research agenda; pp. 3418–3422. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Von Holdt K. Nationalism, bureaucracy and the developmental state: the South African case. South African Rev Sociol. 2010;41:4–27. doi: 10.1080/21528581003676010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams T.A., Gruber D.A., Sutcliffe K.M., Shepherd D.A., Zhao E.Y. Organizational response to adversity: fusing crisis management and resilience research streams. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017;11(2):733–769. doi: 10.5465/annals.2015.0134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum . 2019. Global Future Council on Health and Healthcare 2018-2019 A Vision for the Future : Transforming Health Systems.http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GFC_reflection_paper.pdf [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.