Abstract

The concept of a mechanical device to support failing hearts arose after the introduction of the heart lung bypass machine pioneered by Gibbon. The initial devices were the pulsatile paracorporeal and total artificial heart (TAH), driven by noisy chugging pneumatic pumps. Further development moved in three directions, namely short-term paracorporeal devices, left ventricular assist devices (LVADs), and TAH. The paracorporeal pumps moved in the direction of electrically driven continuous-flow pumps as well as catheter-mounted intracardiac pumps for short-term use. The LVAD became the silent durable electric, implantable continuous-flow pumps. The TAH remains a pneumatically driven pulsatile device with limited application, but newer technology is moving toward electrically operated TAH. The most successful pumps are the durable implantable continuous-flow pumps now taken over by the 3rd-generation pumps for the bridge to transplant and long-term use with significantly improved survival and quality of life. But bleeding including gastrointestinal bleeding, strokes, and percutaneous driveline infections exist as troublesome issues. Available data supports less adverse hemocompatibility of HeartMate 3 LVAD. Eliminations of the driveline will significantly improve the freedom from infections. Restoring physiological pulsatility to continuous-flow pumps is in the pipeline. Development of appropriate right VAD, miniaturization, and pediatric devices is awaited. Poor cost-effectiveness from the cost of LVAD needs to be resolved before mechanical cardiac support becomes universally available as a substitute for heart transplantation.

Keywords: Mechanical cardiac support, Left ventricular assist device, Total artificial heart, Heart transplantation, Heart failure, Bridge to transplantation, Destination therapy

Introduction

Globalization has resulted in an epidemiologic transition in developing countries, from infectious disease and nutritional deficiencies, to non-communicable diseases such as hypertension, coronary artery disease, diabetes, and obesity [1]. Even in India, cardiovascular diseases (CVD) have become the leading cause of mortality. A quarter of all mortality is attributable to CVD. Ischemic heart disease and stroke are the predominant causes and are responsible for more than 80% of CVD deaths [2]. With the increasing incidence of CVD and the aging population, the burden of heart failure (HF) is likely to rise [3]. Although both pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies are available, HF usually requires life-long medications. In fact, India contributed to the finding that neuroendocrine activation occurs in HF, when Roberto Ferrari and his colleagues visited India in the early 1980s to study patients with untreated HF, at the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India [4]. Unfortunately, affordability and compliance are major hurdles in managing these patients. Once the patient reaches end-stage HF, the options are limited to heart transplantation and ventricular assist devices (VADs). However, these options are only available to a select group of patients, to prolong life and offer an opportunity to return to the community with significantly improved quality of life [5]. These therapeutic options are available only in a few centers in the region [6]. The number of cardiac transplants performed in India is far less than required, which is estimated to be a minimum of over 5000 transplants per year, based on its population of 1369 million, at 3 per million. The interest in heart transplantation is growing and according to the Transplant Authority of Tamil Nadu, where most of the heart transplants are done in India, the number of transplants has significantly increased from 11 in 2010 to 89 in 2019 [7].

VADs will be an alternative option for heart transplants, but they are limited to a handful of centers. The use of such devices is unlikely to be cost-effective when addressing a much bigger target population that needs to be managed with lesser resources [6]. In this article, the development of VADs, current application, and the future direction of mechanical cardiac support (MCS) are reviewed. The discussion focuses mainly on the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved devices to limit the discussion.

Development of MCS

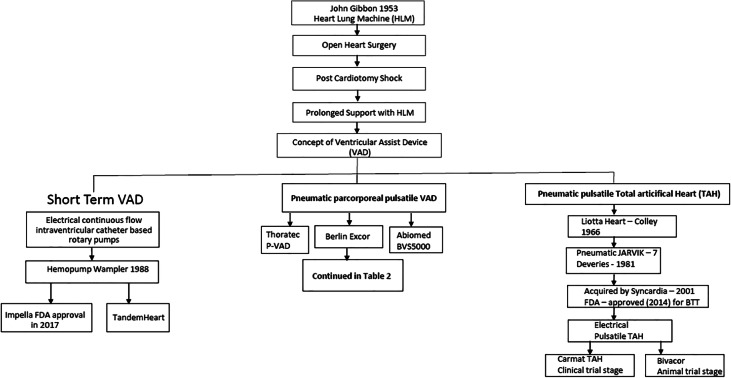

The seminal event that led to the possibility of replacing the function of heart and lungs by mechanical devices was on May 6, 1953, when Dr. Gibbon, Jr., performed the first successful clinical heart surgical procedure with the use of a heart-lung machine, which he developed [8]. Further development in the heart-lung machine led to the rapid adaptation of open-heart surgery. One significant sequential issue was the occurrence of post-cardiotomy shock, due to inadequate myocardial preservation, before the era of cardioplegia. It was also observed that at times prolonged heart-lung support led to the recovery of the heart to resume adequate function. This led to the concept of mechanical cardiac support in the form of VADs followed by total artificial heart (TAH), when there is no recovery, or in patients with irreversible HF. These devices were based on pneumatically activated pulsatile paracorporeal VADs and implantable TAH.

The first successful clinical application of VAD, as a bridge to recovery, was by Dr. DeBakey on August 8, 1966, in a lady who could not be weaned off heart-lung bypass after double valve replacement [9]. With the emergence of heart transplantation in the 1980s, the VAD application emerged as a bridge to transplantation to support a failing heart while awaiting transplantation [10, 11].

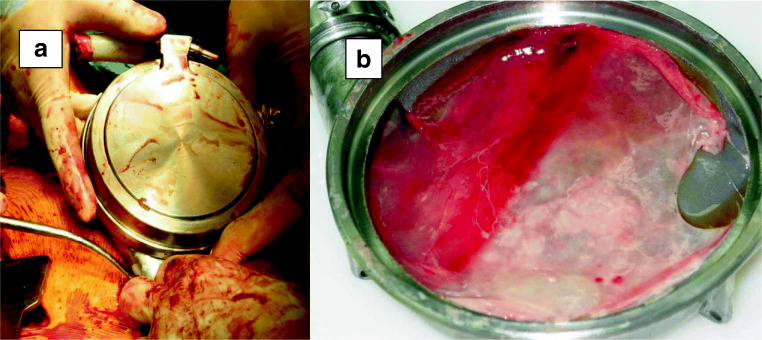

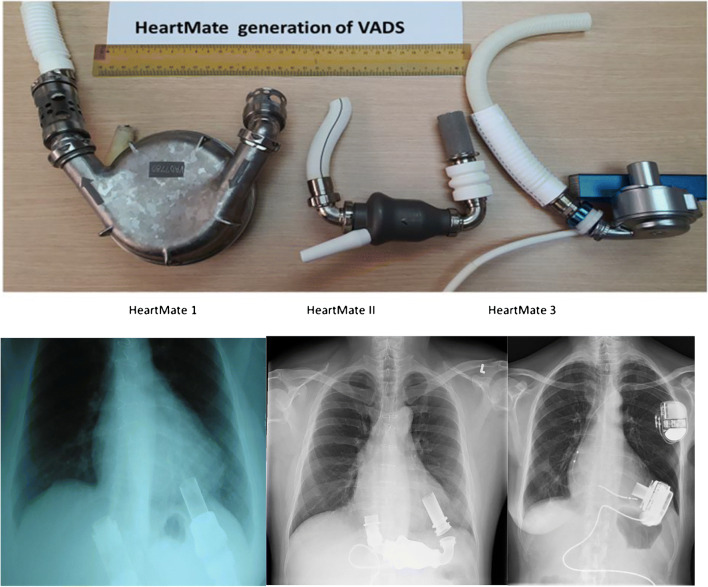

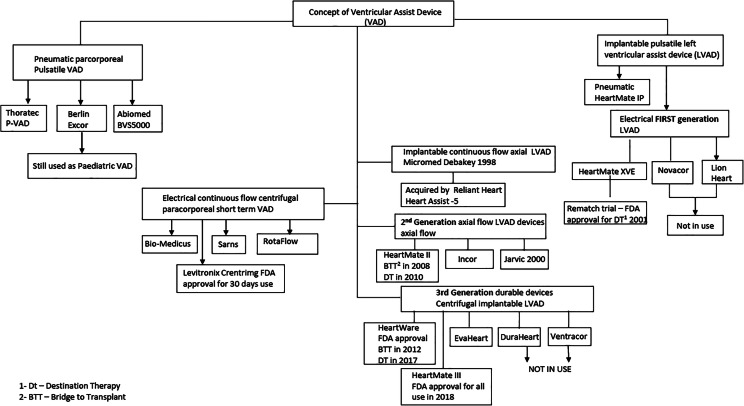

The number and types of assist devices also varied considerably. Mostly they were the paracorporeal pneumatic pumps. The pneumatic pumps required large consoles to operate the noisy pneumatic pumps tethered to the patient. These include Thoratec (Thoratec Corporation, Berkeley, CA) (Fig. 1), Abiomed BVS 5000 (ABIOMED, Danvers, MA, USA) (Fig. 2), and BerlinHeart-Excor (Berlin Heart GmbH, Berlin, Germany). The development of implantable left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) led to the first-generation LVADs which were the pneumatically operated HeartMate IP, followed by HeartMate VE, XVE (Thoratec Corp, Pleasanton, CA), Novacor (World Heart Corp., CA, USA), and LionHeart LVD2000 (Arrow International, PA, USA). The latter three were electrically operated pulsatile devices. These were the devices that came to the clinical arena. The notable feature of HeartMate (Fig. 3) with its sintered blood contact surface is that it only required antiplatelet agent, unlike other devices which required anticoagulation as well. The Novacor LVAD was approved for bridge to transplant (BTT) therapy by the FDA; however, this device has been discontinued. The LionHeart LVAD is a fully implantable device that lacks a percutaneous lead and is powered by a transcutaneous energy transmission system. It failed to achieve FDA commercial approval. Neurological complications and device failure resulted in the failure of the device. The implantable electrical pumps became popular, as they did not have to be tethered to consoles and patients can be discharged on rechargeable batteries. This led to the Rematch trial with the HeartMate XVE. Rematch Study [12] demonstrated conclusively the benefit of a LVAD over medical treatment for patients with irreversible heart failure, leading to FDA approval as destination therapy (DT). But the durability of the pump in the second year and pump-related infections became major limiting factors. The 2-year survival in the Rematch trial dropped to 24 from 53% at 1 year. The survival in the medical arm was 25% at 1 year and 8% at 2 years.

Fig. 1.

Thoratec P-VAD in biventricular support configuration

Fig. 2.

Abiomed BVS 5000 VAD

Fig. 3.

a HeartMate I: Explantation in a recovered patient with advanced heart failure. b Pseudo-membrane on the sintered surface of the explanted HeartMate I, requiring anti-platelets only

Development of TAH

The first TAH, the Liotta Heart, was also implanted in 1966 by Denton Cooley and his colleagues as a bridge to cardiac transplantation [13]. The implantation of a TAH as a permanent therapy was first performed by William DeVries et al. in 1981 [14]. They used the Jarvik-7 and the patient survived for 112 days. The Jarvik heart subsequently came to be known as CardioWest. It remained pneumatically operated. The development of TAH was slow. Device thrombosis, hemolysis, and infection were a major hindrance to its development. The technology was bought over by SynCardia which was founded in 2001 by Dr. Jack G. Copeland, Richard G. Smith, and Marvin J. Slepian [15]. It is the only currently approved option for the treatment of biventricular failure with an implantable TAH. It received FDA approval for the BTT in November 2014. The Syncardia TAH (Tucson, AZ, USA) relies on two pneumatically driven polyurethane ventricles. The external console consists of a pneumatic driver, electronics, air tanks, and transport batteries. A portable console is now available to allow hospital discharge. Two versions are available. The 70-cc version requires a body surface area (BSA) ≥ 1.7 m2 and anteroposterior distance of 10 cm at the level of the 10th thoracic vertebra. The 50-cc version supports a BSA of ≤ 1.85 m2. Both versions have the FDA approval for BTT. In a retrospective study of 47 patients who received TAH from 10 centers with a minimum of 1 year of support, 34 patients (72%) were successfully transplanted, and 12 patients (24%) died while on device support [16]. Five patients (10%) had device failure. Systemic infections occurred in 25 patients (53%), driveline infections in 13 (27%), thromboembolic events in 9 (19%), and hemorrhagic events in 7 patients (14%). Infections and hemorrhagic events were the major causes of death.

Two other electrically operated TAHs that are being developed are Carmat TAH and Bivacor. Carmat is a pulsatile pump having internal electro-hydraulic actuation of the membranes and is undergoing clinical evaluation [17]. In Carmat TAH, the blood-contacting surface of the membrane is processed bovine pericardial tissue. Bivacor is currently undergoing animal trials. It is a small compact device with a magnetically levitated rotor located between opposing pump casings. An external controller and batteries provide power to the internal device via a percutaneous driveline.

Development of LVAD

Parallel to the development of pulsatile pumps, Dr. DeBakey’s collaboration with National Aeronautics and Space Administration engineers led to the development of a miniature electrical axial-flow blood pump [18], based on Archimedes “screw pump” which was used for raising water for irrigation in the third century before Christ [19]. The Micromed DeBakey pump obtained its Conformité Européenne (French for “European Conformity”) (CE) mark in 1998, but it lost its impact with issues related to hemo-incompatibility resulting in the increased incidence of pump thrombosis and stroke. The company filed for bankruptcy in 2013. Now, it is being developed as an axial-flow LVAD (HeartAssist5) and as an intraventricular LVAD (aVAD® ReliantHeart (ReliantHeart Inc., Houston, TX)). Both retain the ultrasonic flow probe used in the Micromed DeBakey pump (Fig. 4), which is placed around the outflow graft. Both pumps have remote device monitoring.

Fig. 4.

Micromed-Debakey LVAD with the ultrasound flow probe on the outflow graft and post-implant X-ray

In fact, the development of durable LVADs, based on rotary flow blood pumps, began after the successful implantation of a catheter-mounted axial flow blood pump via intravascular access in 1988. This device, the Hemopump [20], developed by Wampler, successfully supported the circulation of a patient in cardiogenic shock secondary to acute rejection in a transplanted heart. In effect, this sentinel event demonstrated that continuous-flow blood pumps could be used to support patients in cardiogenic shock. The currently approved catheter mounted intravascular axial-flow pump version for short-term use is the Impella (ABIOMED, Danvers, MA, USA), approved by FDA in 2017 [21]. It is inserted into the left ventricle (LV) across the aortic valve to pump the blood out into the aorta. Another available catheter device is TandemHeart® percutaneous ventricular assist device (CardiacAssist, Inc.; Pittsburgh, PA). The inflow catheter is inserted via the femoral vein into the left atrium (LA) through the interatrial septum. It draws the blood out of LA and pumps into the systemic circulation, through an outflow catheter inserted through the femoral artery. Based on axial-flow technology, other implantable durable axial-flow pumps that were developed are the HeartMate II (HMII) (Abbott, St. Paul, MN, USA), Incor (Berlin Heart GmbH; Berlin, Germany), and Jarvik 2000 (Jarvik Heart, Inc., New York, NY, USA). The pump rotor spins on two bearings within the housing. All of them have drivelines that exit from the body connected to a controller and rechargeable batteries. They became the second-generation, mechanically reliable, silent devices, eliminating valves and mechanical components, other than the electromagnetic rotor. The clinical study for evaluation of the Jarvik 2000 axial-flow VAD began in April 2000 [22], but it remains as a FDA investigational device. Only the HeartMate II became the FDA-approved LVAD for clinical use based on its extensive clinical trials.

Current durable continuous-flow LVADS

HMII bridge to transplant (BTT) [23] was a prospective, multicenter study without a concurrent control group of 133 patients. The survival rate during support was 75% at 6 months and 68% at 12 months. At 3 months, the therapy was associated with significant improvement in functional status, based on the New York Heart Association class and 6-min walk test, along with improvement in the quality of life (according to the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure and Kansas City Cardiomyopathy questionnaire). Major adverse events included postoperative bleeding, stroke, right heart failure, and percutaneous lead infection. Pump thrombosis occurred in two patients. BTT approval was granted by the FDA in 2008.

HMII Destination Therapy (DT) [24] Trial was a prospective, randomized, multicenter clinical trial comparing patients with advanced heart failure, who were ineligible for transplantation, consisting of 134 patients with HMII and 66 patients with HM XVE. The primary composite endpoint was survival at 2 years. Patients with HMII had superior actuarial survival rates at 2 years (58% vs. 24%, P = 0.008). Adverse events and device replacements were less frequent in patients with the continuous-flow device. The quality of life and functional capacity improved significantly in both groups. Based on the above trials, FDA approved HMII for DT therapy in 2010.

Other non-pulsatile technologies that came to the scene from the 1990s as short-term devices are the centrifugal pumps, Bio-Medicus, Sarns, RotaFlow, and Levitronix CentriMag. These are extracorporeal blood pumps. The Levitronix CentriMag (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL) pump is fully magnetically levitated pump and has the FDA approval for use up to 30 days. It is used as a short-term device [25] as LVAD, right VAD (RVAD), or biventricular assist device (BIVD) (Fig. 5). These devices are also used in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) circuits.

Fig. 5.

Levitronix centrifugal pumps in extracorporeal biventricular configuration

Developments in implantable durable LVAD centrifugal pumps led to the several devices, namely VentrAssist, DuraHeart LVAD (Terumo Heart Inc., MI, USA), EvaHeart 2 (Sun Medical Technology Research Corporation, Nagano, Japan), HeartWare (HVAD) (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA), and HeartMate 3 (HM3). The latter two devices are intrapericardial and approved for BTT and for long-term use by FDA. The rest of them require abdominal pump pockets. The intrapericardial pumps form the 3rd-generation LVADS. The DuraHeart was acquired by Thoratec in 2013 and no further development has taken place. In 2009, Ventracor was liquidated due to financial problems. The EvaHeart 2 is approved for clinical use in Japan but is yet to obtain FDA approval. The progression of technology along with better patient selection, and getting over the learning curve of management has resulted in a significant improvement in patient morbidity and mortality. The 1-year survival has risen from 53% with the first-generation support devices to 80–85% for the 2nd- and 3rd-generation devices based on INTERMACS registry data [26]. The first centrifugal pump that entered the clinical trial was the HVAD (Fig. 6). It is a hydromagnetically levitated pump, where the rotor or the impeller is free from contact surfaces while functioning. It obtained its FDA approval for BTT in November 2012 and for DT in September 2017.

Fig. 6.

a HeartWare (explanted) pump; b operative view of HeartWare outflow graft anastomosed to the ascending aorta. Cross clamp is on proximal graft with a needle in the graft to de-air

The ADVANCE trial [27] was a prospective multicenter BTT trial consisting of 140 HVAD recipients who were compared contemporaneously with data from 499 BTT patients who received the HMII, from the INTERMACS registry [28]. The primary outcome success was defined as survival on the originally implanted device, transplantation, or explantation for ventricular recovery at 180 days and was evaluated for both noninferiority and superiority. Secondary outcomes included a comparison of survival, functional, quality-of-life outcomes, and adverse events in the investigational device group. Success occurred in 90.7% of investigational pump patients and 90.1% of controls, establishing the noninferiority of the HVAD (P < 0.001; 15% noninferiority margin).

The Endurance trial [29] is the HVAD DT trial. It was a multicenter randomized trial involving 446 patients who were assigned, in a 2:1 ratio, between HVAD and HMII. The primary endpoint was survival at 2 years, free from disabling stroke or device removal for malfunction or failure. The primary endpoint was achieved in 55.4% of 164 patients in the HVAD group and 59.1% of 85 patients in the HMII group. The analysis showed the noninferiority of the study device relative to the control device. But more patients in the HM II group, than the HVAD group, had device malfunction or device failure requiring replacement (16.2% vs. 8.8%), and more patients in the HVAD group had strokes (29.7% vs. 12.1%, P < 0.001). The quality of life and functional capacity improved to a similar degree in the two groups.

The Endurance trial was followed by the Endurance Supplemental trial [30], which was published in 2018. This study aimed to prospectively evaluate the impact of keeping the blood pressure of patients in the HVAD group below 90 mmHg, on stroke incidence. The inlet cannula of the pump also underwent modification with sintering. The Supplemental trial was a prospective, multicenter evaluation of 465 patients randomized 2:1 to HVAD (n = 308) or control (n = 157). The primary endpoint was the 12-month incidence of transient ischemic attack or stroke with residual deficit, 24 weeks post-event. Secondary endpoints included a composite of freedom from death, disabling stroke, and need for device replacement or urgent transplantation. The results showed that enhanced blood pressure protocol significantly reduced the mean arterial blood pressure. The primary endpoint occurred in 14.7% with HVAD vs. 12.1% with control, not achieving noninferiority. However, the secondary composite endpoint demonstrated the superiority of HVAD (76.1%) versus control (66.9%) (p = 0.04). The incidence of stroke in HVAD subjects was reduced by 24.2% in ENDURANCE Supplemental trial compared with ENDURANCE (p = 0.10). The hemorrhagic cerebrovascular accident was reduced by 50.5% (p = 0.02). The trial confirmed that BP management is associated with reduced stroke rates in HVAD subjects.

HeartMate 3 LVAD obtained its FDA approval for BTT and long-term support in October 2018, after the publication of 2-year outcomes in March 2018 [31]. It is a fully magnetically levitated pump, designed with wider gaps between the impeller and housing, to minimize shear stress-induced hemo-incompatibility between the blood and contact surfaces in the pump. The progressive development of HeartMate LVADs is reflected in Fig. 7. The 2-year follow-up study was a randomized noninferiority and superiority trial, comparing 190 patients with HM 3 and 176 HM II patients, including BTT and DT. The composite primary endpoint was survival at 2 years, free of disabling stroke, to replace or remove a malfunctioning device. The primary endpoint occurred in 151 patients (79.5%) in HM3 and 106 (61.2%) in HM II (P < 0.001 for noninferiority): hazard ratio, 0.46; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.31 to 0.69 (P < 0.001 for superiority). Reoperation for pump malfunction occurred in 3 with HM3 (1.6%) vs 30 patients in HM II (17.0%) (P < 0.001). The rates of death and disabling stroke were similar in the two groups, but the overall rate of stroke was lower in HM3 than in that HM II (10.1% vs. 19.2%; P = 0.02). The significant observation was that the reoperation for pump malfunction in HM3 was only 1.6%.

Fig. 7.

The 3 generations of HeartMate LVADS with corresponding X-rays. HeartMate I and II are explanted pumps. HeartMate 3 is a dummy pump

The progressive development of MCS devices is summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Development of mechanical cardiac support (MCS)

Table 2.

Development of ventricular assist devices (VADs)

Post-implant complications

Although the 2nd- and 3rd-generation LVADs have significantly improved survival and quality of life, post-implant complications and hospital readmissions remain important issues. Thus, the trial REVIVE-IT [32] was designed to compare long-term LVAD therapy with optimal medical management in patients with less advanced HF. The aim was to determine whether LVAD therapy would improve survival, quality of life, or functional capacity. The trial was terminated due to futility of trial enrolment because of a loss of equipoise among a significant number of clinical sites, concerning placing the LVAD in a less ill population. Another reason was the inability to enroll subjects into the complex trial, within the remaining time frame of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute contract in April 2015.

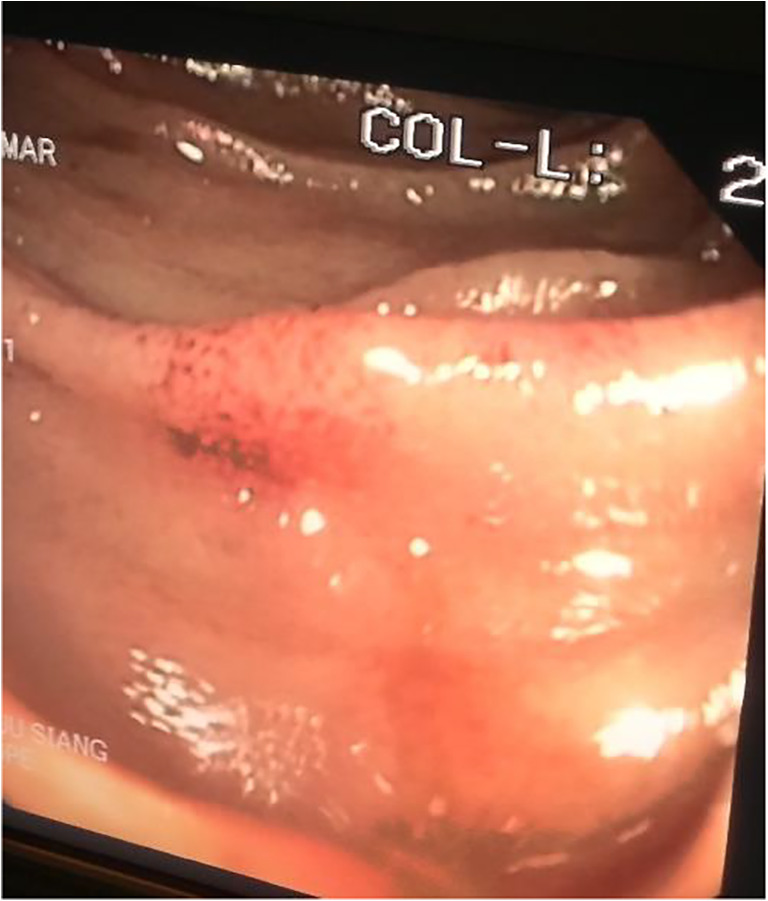

The Intermacs annual database published in 2019 [33] reveals Kaplan-Meier survival rates at years 1, 2, and 5 as 83%, 73%, and 46% respectively after continuous-flow LVAD implantation. A total of 19% of deaths were due to strokes. Freedom from all-cause rehospitalization was up to 53% by 3 months and by 12 months, approximately 20% were free from readmissions. Perioperative bleeding requiring reopening surgery was reported around 20 to 30%. Causes of early post-operative bleeding included diffuse coagulopathy in the setting of chronic heart failure. Gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB) is a common complication after LVAD. The GIB rate in Intermacs data was 7.09 per 100 patient-months for the axial-flow LVAD compared with 5.26 for the centrifugal-flow pump between 3 and 12 months after LVAD implantation [33]. Causes of late bleeding are multifactorial and attributed to the use of chronic antiplatelet, warfarin therapy, absence of pulsatile flow, the development of arteriovenous malformations [34] (Fig. 8), and acquired von Willebrand syndrome [35] by exposure of blood elements to shear stress forces within the pump and hepatic dysfunction, due to post-implant right ventricular failure. Another serious complication after LVAD implantation is the infection of the device or its components. The driveline skin interface is a major source for the infections to set in. Once the infection sets in, it can spread to the pump pocket and can result in hematogenous spread. Driveline infections (DLI) negatively impact recipient quality of life; potential complications include the development of sepsis/bacteremia, hospital re-admissions, pump pocket infection, pump thrombosis, re-operation, and strokes. Pump-related infection after 3 months is about 2.5 per 100 patient months in the Intermacs report. Neurologic complications are devastating and reported to occur in 0.98 to 1.4 per 100 patient-months [33]. Progressive aortic insufficiency (AI) (Fig. 9) is a commonly recognized entity, affects 25 to 30% of patients within the first year of implantation, and is increasingly being recognized as a cause of recurrence of symptomatic HF [36]. Management will involve closure or replacement of the aortic valve. Anecdotal reports of percutaneous transaortic valve implants or closure devices have been reported with mixed results.

Fig. 8.

Hemorrhagic patch of arteriovenous malformation in the jejunum

Fig. 9.

Aortic incompetence due to fusion of commissures and retraction of cusps in an explanted LVAD supported heart

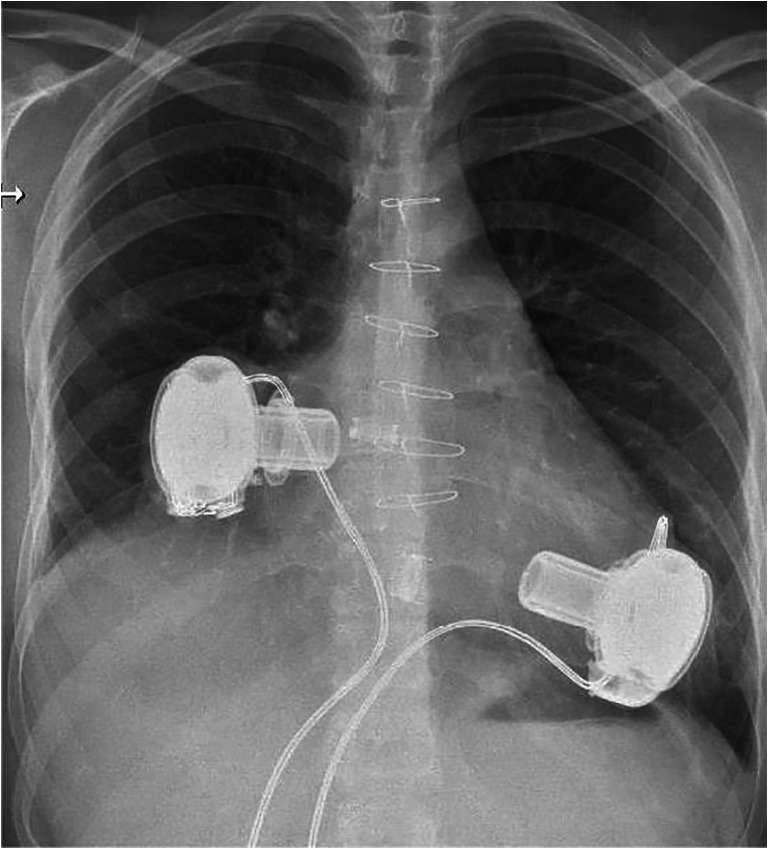

Late right HF (RHF) is another issue seen after LVAD implantation. According to Intermacs report [33], de novo RHF first identified at 6 months, persisted at 12 m in 31% of cases. The late RHF can be due to progression of the cardiomyopathy or due to insufficient unloading or excessive unloading of the left ventricle and deviation of the interventricular septum to the left, or progression of AI. Unfortunately, there are no implantable durable devices available for clinical use in RHF. Off-label use of continuous-flow durable LVADs as RVAD, as well as biventricular devices, are being used (Fig. 10), especially with 3rd-generation devices [37]. Intermacs 2019 data [33] has reported poorer survival of 58% and 31% at 1 and 5 years after implantation, with biventricular support. Off-label use of HeartWare as a permanent RVAD has also been reported [38].

Fig. 10.

Biventricular support with HVADs

Device malfunction related to the controller, battery, and driveline failure occurs and is reported to be 3.73 per 1000 patient-days for HM II and 3.06 per 1000 patient-days for the HVAD (P < 0.01) [39]. The same report also noted that freedom from a failure of the integrated driveline was 79% at 3 years for the HM II and 100% for the HVAD (log-rank P < 0.02).

Exploring the long-term challenges and supportive care needs of LVAD patients and caregivers is important, especially in the context of the Asian healthcare setting [40]. It is currently recommended for centers with Mechanical Circulatory Support programs to include supportive care personnel as part of the managing team [41]. Possible supportive care interventions include managing symptoms, psycho-emotional support, advance care planning, and bereavement support, especially for DT patients and caregivers [42, 43].

Pediatric MCS

The field of MCS for children has significantly lagged behind its adult counterpart. This is primarily because of limitations in MCS designs available for infants and small children, size mismatch, congenital cardiac anomalies, delicate blood vessels, multiple surgeries in staged repair, etc. To address such issues, the US National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) launched the US Pediatric Circulatory Support Program in 2004, which is the predecessor of the PumpKIN (Pump for Kids, Infants, and Neonates) program. The goal of this program was to develop mechanical circulatory support devices, specifically designed for small children. The Infant Jarvik 2015, one of the original devices within the PumpKIN Program, has become the first continuous-flow VAD specifically designed for small children that obtained the Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) from FDA. This approval is a prerequisite to initiating a clinical trial. ECMO remains the primary device for acute short-term support. With widespread acceptance and application of the paracorporeal Berlin Heart EXCOR, which is available in a wide range of sizes (Fig. 11), even the smallest infants can now benefit from long-term VAD support. The PediMag is the pediatric version of the CentriMag being used as an extracorporeal, centrifugal, continuous-flow device for those < 20 kg. It has a priming volume of 14 mL and can provide up to 1.5 L/min flow. Also, the relatively smaller 3rd-generation devices have allowed for their use in larger children and adolescents [43]. They have been used in small patients down to BSA of 0.7 m2 and in patients > 25 to 30 kg.

Fig. 11.

The Berlin Heart EXCOR range of ventricular assist pumps. Photograph was taken with courtesy from Professor Roland Hetzer when the author visited his office, in German Heart Institute Berlin (DHZB)

MCS for adult patients with congenital heart is challenging, specifically in patients with failing single ventricle physiology. The 3rd-generation devices are being used as BTT [43] in selected patients.

Future

The three major issues with the currently available approved 3rd-generation devices are driveline-related infections, neurological complications, and bleeding. The overall rate of DLI in various studies ranges from 14 to 48%. It appears to be cumulative over time with increased DLI noted with a greater duration of VAD support [44]. Overall mortality following infections has been reported to be as much as 19.7%.

A fully implantable system that is rechargeable trans-cutaneously is urgently required to reduce infection and improve quality of life, especially in patients requiring long-term support. Attempts to eliminate the driveline using transcutaneous energy transfer systems (TETS) have been explored in pulsatile and TAH over the years. Many issues need to be resolved before the technology can be brought to clinical use. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) have a continuous power consumption of less than 1/4 W; in contrast, the continuous average power consumption of 3rd-generation LVADs is in a range of 4–7 W with a peak power consumption of up to 12 W [45]. For bi-ventricular support or total artificial hearts, the power demand is even higher. Besides, in DT patients, the TETS must be able to provide power continuously with the ability of an independent internal battery system, capable of providing power for reasonable time, independent of the external energy supply. Additional backup battery storage must be included as a safety measure. The TETS must be capable of transferring energy from an external transmitting coil to a small receiving coil that is implanted under the skin. To be successful, the transmitter and receiver must be aligned, and the energy is transferred through the small area of skin that separates them. The power transfer capability requirement of the TETS system is increased by the recharging of the internal backup battery and is therefore expected to be in a range of 25–30 W, depending on the LVAD power consumption and the maximum feasible battery charging power [46]. Studies into energy efficiency, coil misalignment, system volume, implant weight, system reliability, operational safety, design for high power transmission, energy transfer efficiency, the heating of the tissue and the electromagnetic field exposure of the human body, and implantable controller telemetry, and clinical trials are required before the system is available to the clinician.

The other energy transfer system is the coplanar energy transfer system (CET). It is characterized by 2 large rings utilizing a coil-within-the-coil topology, with the internal coil placed within the right pleural cavity. An external transmitter inductive coil with a belt design is placed externally around the body of the patient. The externally located transmitter inductive coil inductively transfers electromagnetic power to the internal inductive coil. It has a low sensitivity to metallic environments in its close proximity, and uses inductive electromagnetic energy transfer for fast charging. It has no skin friction or heating and no direct skin contact. The CET enables a larger distance between the transmitter and receiver coils and can reach higher power levels of up to 30 W. The first human use of a wireless coplanar energy transfer coupled with a continuous-flow Jarvik 2000 LVAD (Jarvik Heart, Inc., New York, NY) was reported by Pya and colleagues in 2019 [47]. It allows > 6 h of unholstered circulatory support powered by an implantable battery source. The authors state that the controller exchange would require replacement in 3 years and that the current dimensions of the internal battery and controller will require future modifications to reduce their size, while retaining charge capacity.

Neurologic complications represent the most devastating issue for LVAD patients. Pump-patient interface-related hemo-incompatibility needs to be minimized. In this direction, the study of more than 1000 patients implanted with HM3 has markedly reduced the need for re-operations due to pump malfunctions and lowered the risk of strokes and bleeding events, compared with the HM II. The disabling stroke rate was 3.9% compared with 5.9% in HM II. (The relative risk (95% CI) was 0.66 (0.38–1.15) [48].) A pilot study on lowering the International Normalized Ratio (INR) targets between 1.5 and 1.9 [49] and discontinuation of aspirin in HeartMate 3 patients have been reported [50]. If randomized studies confirm the safety of these measures, further reduction in bleeding complications is possible.

Continuous flow with low arterial pulsation has been implicated in the development of arteriovenous malformations, AI [51], possible deterioration in renal function [52] with long-term LVAD support, and pathophysiological changes in the aortic wall [53]. Thus, recent researches are being directed toward creating pulsatility, intermittent opening of the aortic valve by speed modulation, and developing algorithms. Other areas that need to be developed are pump response to physiological demands, baroreceptor response, and response to exercise.

Technology for telemetry and remote monitoring of pump performance are available, but are not being used, in the approved 3rd-generation devices. A “cell phone system” within the controller that transmits flow, power, and speed data at a given time is being developed and available. Continuous transmittable pulmonary artery monitoring system, which is available now, has the potential of assessing and monitoring LV unloading remotely [54].

Another current design trend for LVADs is their miniaturization of the pump. But there are limitations to miniaturizing in designing pumps to provide adequate output to the physiological demands of an adult patient. Compromising on impeller gap size, increasing the speed of the pump revolution would increase shear stress, which increases the risk of adverse hemo-compatibility. It has been shown, using computational fluid dynamics (CFD), that due to a jet effect, a 10-mm outflow graft has a lot of eddies and stasis, when compared with a 14-mm graft, which mimics normal flow much more closely. The angle of insertion on the aorta also seems more crucial in a 10 mm, but not in a 14-mm graft [55]. Thus, the size of the outflow conduit needs to be considered in designing miniaturized pumps. But miniaturization in the field of partial support would increase the treatable patient population. Smaller devices offer several potential advantages, including minimally invasive surgery via a mini-thoracotomy, avoiding cardiopulmonary bypass for implantation, and providing partial support and right ventricular support. Miniaturized percutaneous LVADs capable of wireless power operation are also being developed [56].

Cardiac recovery protocols on patients with LVAD support, along with aggressive neurohormonal blockage and maximized heart failure pharmacology [57], have not made any dramatic changes in most practices. Also, adjuvant cell therapy, along with LVAD support [58], has not gained ground.

LVAD therapy, although it improves survival and quality of life, comes at a great cost and is prohibitive in Asian countries [6] unless there is reimbursement from the governments and insurance schemes. Although this can be reduced to lower levels by decreasing readmissions and outpatient costs, in practice it may be difficult to achieve. Furthermore, the readmission cost may not be significant in Asia compared with the device cost, which is between USD 75,000 and 100,000. Shih and Dimick [59] have published that in the USA, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for LVAD destination therapy is estimated at $202,000 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained, and immediate heart transplant had an ICER of $94,800 per QALY gained, whereas LVAD therapy as BTT with a median wait time of 5.6 months had an ICER of $226,300, when compared with inotrope-dependent medical therapy. Shreibati and colleagues [60] calculated that if LVAD outpatient costs could be halved and readmission rates were halved to one readmission per patient-year, the ICER for LVAD can be decreased to $86,900 per QALY gained.

Hence, Asian countries should focus on developing transplant programs, along with developing low-cost mechanical cardiac support, such as ECMO, for use in acute cardiogenic shock as a bridge to decision. Developing low-cost paracorporeal devices for BTT is a possibility. Unfortunately, we will need to depend on durable implantable continuous-flow approved devices for long-term support, if the patient is not a candidate for heart transplantation and meets the appropriate criteria for DT.

Funding

Not applicable

Data availability

Review article supported by published articles.

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethics approval

Not required being a review article

Human and animal rights

Not required being a review article

Informed consent

Not required being a review article

Conflict of interest

Proctoring for Abbott, Asia Pacific.

Attended workshops and educational meetings organized by Abbotts and Medtronic Asia Pacific.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Yusuf S, Reddy S, Ounpuu S, Anand S. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases: part I: general considerations, the epidemiologic transition, risk factors, and impact of urbanization. Circulation. 2001;104:2746–2753. doi: 10.1161/hc4601.099487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shimokawa H, Miura M, Nochioka K, Sakata Y. Heart failure as a general pandemic in Asia. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17:884–892. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pillai HS, Ganapathi S. Heart Failure in South Asia. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2013;9:102–111. doi: 10.2174/1573403X11309020003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anand IS, Ferrari R, Kalra GS, Wahi PL, Poole-Wilson PA, Harris PC. Edema of cardiac origin. Studies of body water and sodium, renal function, hemodynamic indexes, and plasma hormones in untreated congestive cardiac failure. Circulation. 1989;80:299–305. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.80.2.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rogers JG, Aaronson KD, Boyle AJ, et al. Continuous flow left ventricular assist device improves functional capacity and quality of life of advanced heart failure patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1826–34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Sivathasan C, Lim CP, Kerk KL, Sim DK, Mehra MR. Mechanical circulatory support and heart transplantation in the Asia Pacific region. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2017;36:13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2016.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Transplant Authority of Tamil Nadu. https://transtan.tn.gov.in/statistics.php Google search: Accessed 18 April 2020.

- 8.Gibbon JH., Jr Application of a mechanical heart and lung apparatus to cardiac surgery. Minn Med. 1954;37:171–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeBakey ME. Development of mechanical heart devices. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79:S2228–S2231. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pennock JL, Pierce WS, Campbell DB, et al. Mechanical support of the circulation followed by cardiac transplantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1986;92:994–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pennington DG, McBride LR, Kanter KR, et al. Bridging to heart transplantation with circulatory support devices. J Heart Transplant. 1989;8:116–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rose EA, Gelijns AC, Moskowitz AJ, et al. Long-term use of a left ventricular assist device for end-stage heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1435–1443. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooley DA, Liotta D, Hallman GL, et al. Orthotopic cardiac prosthesis for two staged cardiac replacement. Am J Cardiol. 1969;24:723–730. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(69)90460-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeVries WC, Anderson JL, Joyce LD, et al. Clinical use of the total artificial heart. New Engl J Med. 1984;310:273–278. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198402023100501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Copeland JG, Copeland H, Gustafson M, et al. Experience with more than 100 total artificial heart implants. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143:727–734. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Torregrossa G, Morshuis M, Varghese R, et al. Results with SynCardia total artificial heart beyond 1 year. ASAIO J. 2014;60:626–634. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohacsia P, Leprince P. The CARMAT total artificial heart. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;46:933–934. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezu333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeBakey ME, Benkowski R. The DeBakey/NASA Axial Flow Ventricular Assist Device. In: Akutsu T, Koyanagi H, editors. Heart Replacement. Tokyo: Springer; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Archimedes screw. "Archimedes screw." World Encyclopedia. 2020 https://www.encyclopedia.com. Accessed on 6 May 2020.

- 20.Wampler R, Frazier OH. The Hemopump™, The First Intravascular Ventricular Assist Device. ASAIO J. 2019;65:297–300. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lemaire A, Anderson MB, Lee LY, et al. The Impella device for acute mechanical circulatory support in patients in cardiogenic shock. Ann Thorac. Surg. 2014;97:133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.07.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frazier OH, Myers TJ, Westaby S, Gregoric ID. Use of the Jarvik 2000 left ventricular assist system as a bridge to heart transplantation or as destination therapy for patients with chronic heart failure. Ann Surg. 2003;237:631–636. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000064359.90219.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller LW, Pagani FD, Russell SD, et al. Use of a continuous-flow device in patients awaiting heart transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:885–896. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Slaughter MS, Rogers JG, Milano CA, et al. Advanced heart failure treated with continuous flow left ventricular assist device. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2241–2251. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.John R, Long JW, Massey HT, et al. Outcomes of a multicenter trial of the Levitronix CentriMag ventricular assist system for short-term circulatory support. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141:932–939. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Pagani FD, et al. Seventh INTERMACS annual report: 15,000 patients and counting. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2015;34:1495–1504. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aaronson KD, Slaughter MS, Miller LW, et al. Use of an intrapericardial, continuous-flow, centrifugal pump in patients awaiting heart transplantation. HeartWare Ventricular Assist Device (HVAD) Bridge to Transplant ADVANCE Trial Investigators. Circulation. 2012;125:3191–3200. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.058412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Stevenson LW, et al. INTERMACS database for durable devices for circulatory support: first annual report. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2008;27:1065–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rogers JG, Pagani FD, Tatooles AJ, et al. Intrapericardial left ventricular assist device for advanced heart failure. New Engl J Med. 2017;376:451–460. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Milano CA, Rogers JG, Tatooles AJ, et al. HVAD: The ENDURANCE Supplemental Trial. JACC Heart Fail. 2018;6:792–802. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2018.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mehra MR, Goldstein DJ, Uriel N, et al. Two-year outcomes with a magnetically levitated cardiac pump in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1386–1395. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pagani FD, Aaronson KD, Kormos R, et al. The NHLBI REVIVE-IT study: Understanding its discontinuation in the context of current left ventricular assist device therapy. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2016;35:1277–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kormos RL, Cowger J, Pagani FD, et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Intermacs Database Annual Report: Evolving indications, outcomes, and scientific partnerships. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;107:341–353. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suarez J, Patel CB, Felker GM, Becker R, Hernandez AF, Rogers JG. Mechanisms of bleeding and approach to patients with axial-flow left ventricular assist devices. Circ Heart Fail. 2011;4:779–84. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Uriel N, Pak SW, Jorde UP, et al. Acquired von Willebrand syndrome after continuous-flow mechanical device support contributes to a high prevalence of bleeding during long term support and at the time of transplantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1207–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bouabdallaoui N, El-Hamamsy I, Pham M, et al. Aortic regurgitation in patients with a left ventricular assist device: A contemporary review. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2018;37:1289–1297. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2018.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shah P, Richard HA, Singh R, et al. Multicenter experience with durable biventricular assist devices. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2018;37:1093–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2018.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bernhardt AM, De By TM, Reichenspurner H, Deuse T. Isolated permanent right ventricular assist device implantation with the HeartWare continuous-flow ventricular assist device: first results from the European Registry for Patients with Mechanical Circulatory Support. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2015;48:158–162. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezu406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kormos RL, McCall M, Althouse A, et al. Left ventricular assist device malfunctions, it is more than just the pump. Circulation. 2017;136:1714–1725. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.027360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shan Neo SH, Min Ku JS, Sim Wong GC, et al. Life beyond Heart Failure– what are the long-term challenges, supportive care needs and views towards supportive care, of multiethnic Asian patients with left ventricular assist device and their caregivers? J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2020. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Luo N, Rogers JG, Dodson GC, et al. usefulness of Palliative care to complement the management of patients on left ventricular assist devices. Am J Cardiol. 2016;118:733–738. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goldstein NE, May CW, Meier DE. Comprehensive care for mechanical circulatory support: a new frontier for synergy with palliative care. Circ Heart Fail. 2011;4:519–527. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.957241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shugh SB, Riggs KW, Morales DLS. Mechanical circulatory support in children: past, present and future. Transl Pediatr. 2019;8:269–277. doi: 10.21037/tp.2019.07.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Topkara VK, Kondareddy S, Malik F, et al. Infectious complications in patients with left ventricular assist device: etiology and outcomes in the continuous-flow era. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90:1270–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Slaughter MS, Myers TJ. Transcutaneous energy transmission for mechanical circulatory support systems: History, current status and future prospects. J Card Surg. 2010;25:484–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.2010.01074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Knecht OM Transcutaneous Energy and Information Transfer for Left Ventricular Assist Devices. https://www.pespublications.ee.ethz.ch/uploads/tx_ethpublications/Diss_Knecht_no_24719_pdf_links_270818.pdf Google search: Accessed 18 April 2020.

- 47.Pya Y, Maly J, Bekbossynova M, et al. First human use of a wireless coplanar energy transfer coupled with a continuous-flow left ventricular assist device. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2019;38:339–343. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2019.01.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mehra MR, Uriel N, Naka Y, et al. A Fully Magnetically levitated left ventricular assist device — final report. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1618–1627. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1900486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Netuka I, Ivák P, Tučanová Z. Evaluation of low-intensity anti-coagulation with a fully magnetically levitated centrifugal-flow circulatory pump—the MAGENTUM 1 study. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2018;37:579–586. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2018.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lim HS, Ranasinghe A, Mascaro J, Howell N. Discontinuation of aspirin in Heartmate 3 left ventricular assist device. ASAIO J. 2019;65:631–633. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jorde UP, Uriel N, Nahumi N, et al. Prevalence, significance and management of aortic insufficiency in continuous flow left ventricular assist device recipients. Circ Heart Fail. 2014;7:310–319. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yalcin YC, Muslem R, Veen KM, et al. Impact of continuous flow left ventricular assist device therapy on chronic kidney disease: A longitudinal multicenter study. J Card Fail. 2020;26:333–341. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2020.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ambardekar AV, Hunter KS, Babu AN, et al. Changes in Aortic Wall Structure, Composition, and StiffnessWith Continuous-Flow Left Ventricular Assist Devices, A Pilot Study. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8:944–952. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yandrapalli S, Raza A, Tariq S, Aronow WS. Ambulatory pulmonary artery pressure monitoring in advanced heart failure patients. World J Cardiol. 2017;26(9):21–26. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v9.i1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Balakrishnan K, Bhat S, Mathew J, Krishnakumar R. Is the Diameter of the Outflow Graft the Crucial Difference in Stroke Rates Between Heartmate II and HVAD? A Computational Fluid Dynamics Study. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2016;35(4S):324. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2016.01.926. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Letzen B, Park J, Tuzun Z, et al. Design and development of a miniaturized percutaneously deployable wireless left ventricular assist device: early prototypes and feasibility testing. ASAIO J. 2018;64:147–153. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Birks EJ, Tansley PD, Hardy J, et al. Left ventricular assist device and drug therapy for the reversal of heart failure. New Engl J Med. 2006;355:1873–1884. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ibrahim M, Rao C, Athanasiou T, Yacoub MH, Terracciano CM. Mechanical unloading and cell therapy have a synergistic role in the recovery and regeneration of the failing heart. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;42:312–318. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezs067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shih T, Dimick JB. Reducing the cost of left ventricular assist devices: Why it matters and can it be done? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;155:2466–2468. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.12.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shreibati JB, Goldhaber-Fiebert JD, Banerjee D, Owens DK, Hlatky MA. Cost-effectiveness of left ventricular assist devices in ambulatory patients with advanced heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2017;5:110–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Review article supported by published articles.