Abstract

The brainstem, a structure of vital importance in mammals, is currently becoming a principal focus in cognitive, affective, and clinical neuroscience. Midbrain, pontine and medullary structures serve as the conduit for signals between the forebrain and spinal cord, are the epicenter of cranial nerve-circuits and systems, and subserve such integrative functions as consciousness, emotional processing, pain, and motivation. In this study, we parcellated the nuclear masses and the principal fiber pathways that were visible in a high-resolution T2-weighted MRI dataset of 50-micron isotropic voxels of a postmortem human brainstem. Based on this analysis, we generated a detailed map of the human brainstem. To assess the validity of our maps, we compared our observations with histological maps of traditional human brainstem atlases. Given the unique capability of MRI-based morphometric analysis in generating and preserving the morphology of 3D objects from individual 2D sections, we reconstructed the motor, sensory and integrative neural systems of the brainstem and rendered them in 3D representations. We anticipate the utilization of these maps by the neuroimaging community for applications in basic neuroscience as well as in neurology, psychiatry, and neurosurgery, due to their versatile computational nature in 2D and 3D representations in a publicly available capacity.

Keywords: ultrahigh-resolution MRI, human brainstem anatomy, neuroimaging, ontology, terminologia anatomica, brainstem atlas

Introduction

The human brainstem, a relatively small part of the human brain (roughly the size of a human thumb) yet of utmost biological importance, remains one of the most understudied brain regions in basic and clinical neuroscience. Phylogenetically, the brainstem is the oldest part of the brain. It has three main structural divisions rostrocaudally, commonly referred to as the midbrain (or mesencephalon), pons (Latin for “bridge”) and medulla oblongata (“oblong marrow” as well as “bulbus” in Latin; e.g., Willis, 1681; Carpenter and Sutin, 1983; Nieuwenhuys, 2008; Swanson, 2015)1. Located in the posterior cranial fossa between the spinal cord and the diencephalon, the brainstem appears between the 5th and 7th week of embryonic life in humans (Nolte et al., 2016). It is strategically positioned as a conduit for ascending and descending fiber tracts and serves cranial nerve-related as well as higher integrative and neuromodulatory functions (Carpenter and Sutin, 1983; Duvernoy, 1995; Nieuwenhuys, 2008; Blessing and Benarroch, 2012; Nolte et al., 2016). These functions are reflected by the fine morphological, topographical, and qualitative structural architecture of the brainstem, namely the cellular composition of individual nuclei and their fiber connections. From a neural systems perspective, specialized functions of the brainstem are most clearly understood for sensory and motor systems, for which the midbrain, pons, and medulla oblongata contain key interrelated structures. By contrast, the structural and functional anatomy of brainstem systems integrating consciousness, pain, and different types of affect is less clear. Brainstem cytoarchitecture and subsequently its myeloarchitecture have been described to a considerable extent since the early 1900s in classical studies that paved the way for more recent mapping of its nuclear masses and fiber connections (e.g., Olszewski and Baxter, 1982; Swanson, 2015). The atlases resulting from such investigations have enabled us to determine the location and cellular composition of individual nuclei as well as their fiber pathways in the human brainstem. These lines of investigation have been crucial in understanding normative neuroanatomy as well as neuropathology (e.g., Olszewski and Baxter, 1982).

With the advent of MRI, studies of the brainstem have demonstrated the potential of neuroimaging for analyzing this brain component structurally, metabolically and functionally (Toga and Mazziotta, 2002; Aggarwal et al., 2013; Deistung et al., 2013; Beissner, 2015; Sclocco et al., 2018; Tang et al., 2018; Edlow et al., 2019). Currently, ex-vivo acquisitions of human brain tissue using high field MRI scanners have allowed for high spatial resolution brainstem datasets (e.g., Calabrese et al., 2015; Edlow et al., 2019). These datasets have enabled the visualization of gray and white matter structures to such a degree that the goal of matching morphologically histological preparations traditionally used in neuroanatomy with those of the MRI images has been met for certain nuclei as a whole, although not yet at the cellular level. Precise MRI-based 2D and 3D computational reconstructions of gray and white matter anatomical structures allow their integration into current multimodal neuroimaging, a unique feature of current morphometric analysis, with a significant advantage over traditional histological methodologies. Consequently, these data can be used in different fields of basic and clinical neuroscience in which knowledge of structure, function, and metabolism of the human brainstem is needed.

In the present study, we parcellated the anatomical gray matter structures and the fiber pathways of conduit and cranial nerve systems that were visible in an ultrahigh-resolution T2-weighted MRI dataset of a postmortem human brainstem. Based on our initial analyses, we combined the gray and white matter parcellation results to generate a detailed map of the human brainstem. To evaluate the anatomical accuracy and precision of our maps, we compared our observations with histological maps of classical human brainstem atlases. Furthermore, by assembling the different component structures, we reconstructed the motor, sensory, and integrative neural systems of the brainstem and rendered them in 3D representations. Given the computational nature of our maps in 2D and 3D spaces, we anticipate their utilization by the neuroimaging community at large for applications in basic and clinical neuroscience.

Materials and Methods

Image Acquisition and Protocol Parameters of an Ultrahigh-Resolution ex vivo T2-Weighted MRI Dataset

Postmortem imaging was performed in a single human brainstem from an anonymous 65-year old male donor as described by Calabrese et al. (2015), following our institutional rules and guidelines. Briefly, the brain was extracted with a post-mortem interval of 24 h and the brainstem and thalamus were dissected. The vasculature was flushed with normal heparinized saline (100 UI/ml heparin) and the brain subsequently immersed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 2 weeks. A week before scanning, the sample was placed in a 0.1 M phosphate buffer containing 1% gadoteridol. Before imaging, the brain was immersed in liquid fluorocarbon (Galden PFPE, Solvay Plastics, Brussels, Belgium). RF transmission and reception were achieved with a 65 mm inner-diameter quadrature RF coil. Anatomical images were acquired using a 3D gradient echo pulse sequence with repetition time (TR) = 50 ms, echo time (TE) = 10 ms, flip angle (a) = 60 degrees, and bandwidth (BW) = 78 Hz/pixel. The field of view (FOV) was 80 × 55 × 45 mm, and the acquisition matrix was 1,600 × 1,100 × 900 resulting in a 50-micrometer isotropic voxel size. The total acquisition time was 14 h (Calabrese et al., 2015).

Anatomical Image Analysis: Segmentation and Labeling of Regions of Interest

Identification and delineation of anatomical regions of interest (ROI) were carried out on the T2-weighted MRI dataset as follows. Every 5th axial slice was manually segmented, using the 3D Slicer software analysis platform to perform segmentation and labeling of visualized brainstem anatomical structures (Fedorov et al., 2012). All the tools used are publicly available and can be downloaded from the official 3D Slicer website1. The segmentation of structures was done as follows. The brainstem was segmented as a whole and then subdivided into three component parts, namely midbrain or mesencephalon, pons, and medulla. Following traditional anatomical conventions, the limiting axial plane between the midbrain and the pons was set at the uppermost extent of the basis pontis, whereas the limiting axial plane between the pons and the medulla was set at the lowermost extent of the basis pontis (DaSilva et al., 2002). This yielded a gross morphological definition and topographical delimitation of the brainstem in the context of traditional neuroanatomical descriptions. Subsequently, segmentation of gray matter and white matter structures was carried out individually for each nucleus and fiber tract. This was performed using the Segment Editor module of 3D Slicer, which allows segmentation operations. To ensure anatomical accuracy in the identification of gray and white matter structures we were also guided by anatomical textbooks and atlases of the brainstem. These included Olszewski-Baxter (Olszewski and Baxter, 1954, 1982; Büttner-Ennever and Horn, 2014) Paxinos and Huang (Paxinos and Huang, 1995), Haines (Haines, 1991), Carpenter and Sutin (Carpenter and Sutin, 1983), Mai and Paxinos (Mai and Paxinos, 2012), and Nolte (Nolte et al., 2016; Vanderah, 2018). Furthermore, we assessed our results by matching the extent of each structure of our analysis with those of Paxinos and Huang (1995). To address neural systems analysis in the brainstem, we assembled individual structures into the motor, sensory and integrative (or neuromodulatory) neural systems, a topic of great relevance in current basic and clinical neuroscience (Dahlström and Fuxe, 1964; Mesulam, 2000; Solms and Turnbull, 2002; Panksepp, 2004; Damasio, 2010; Blessing and Benarroch, 2012).

Results

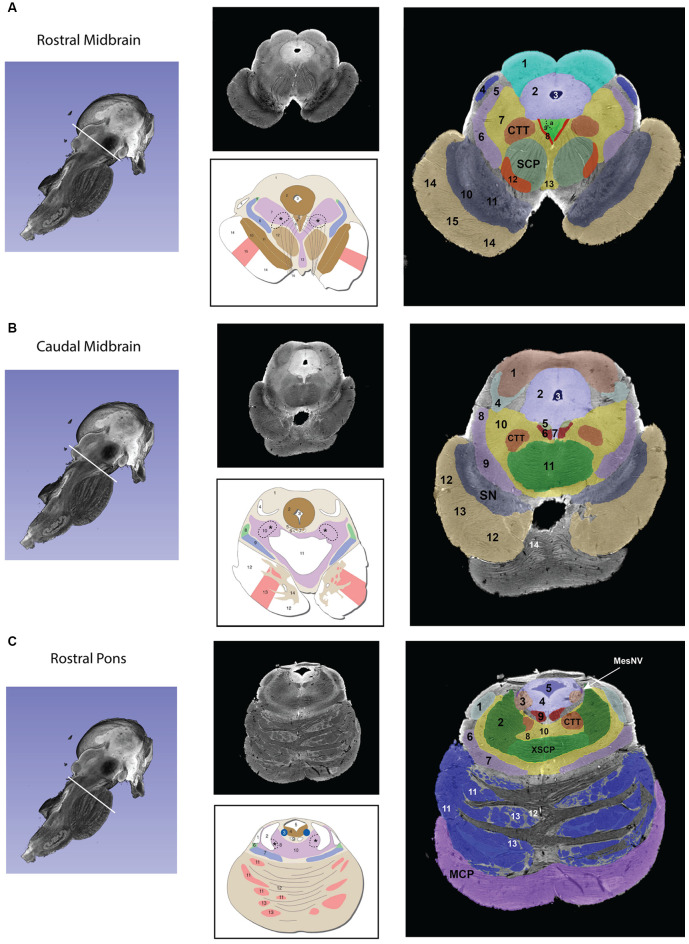

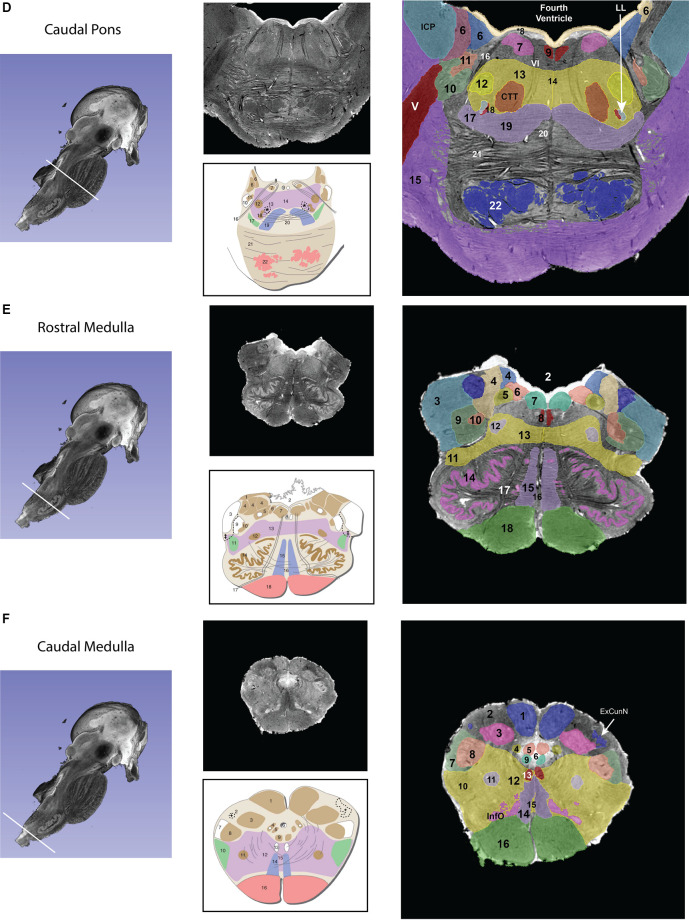

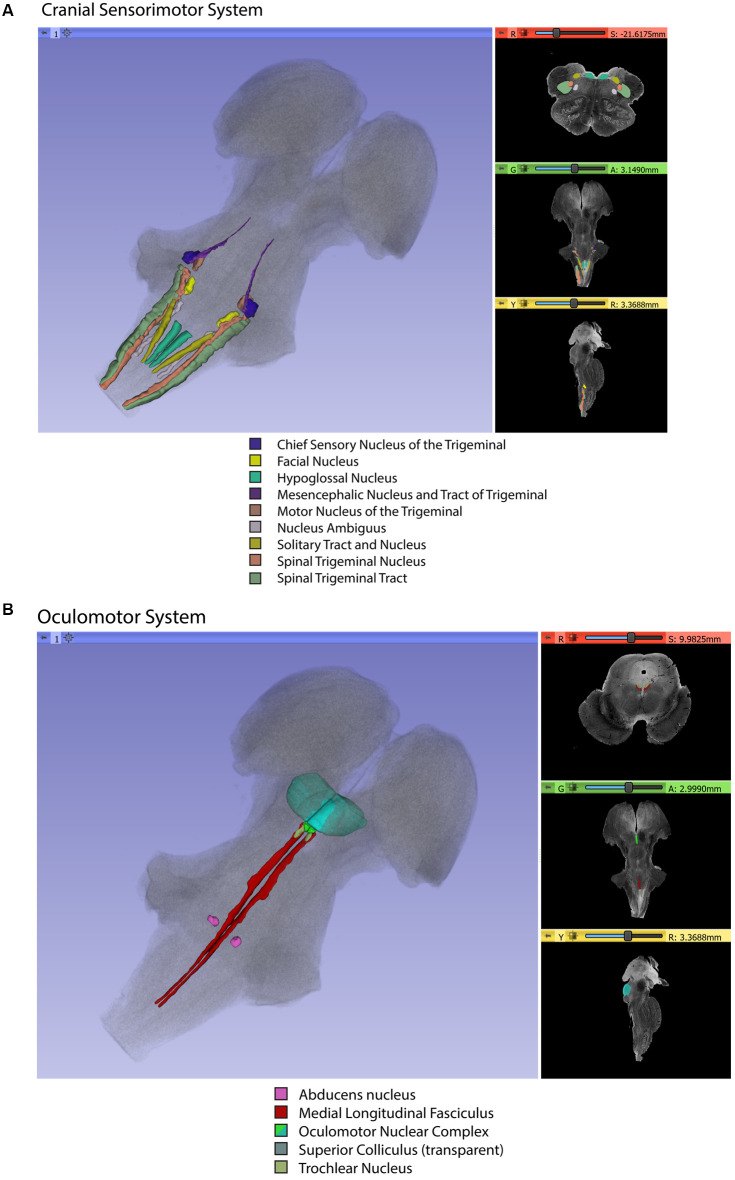

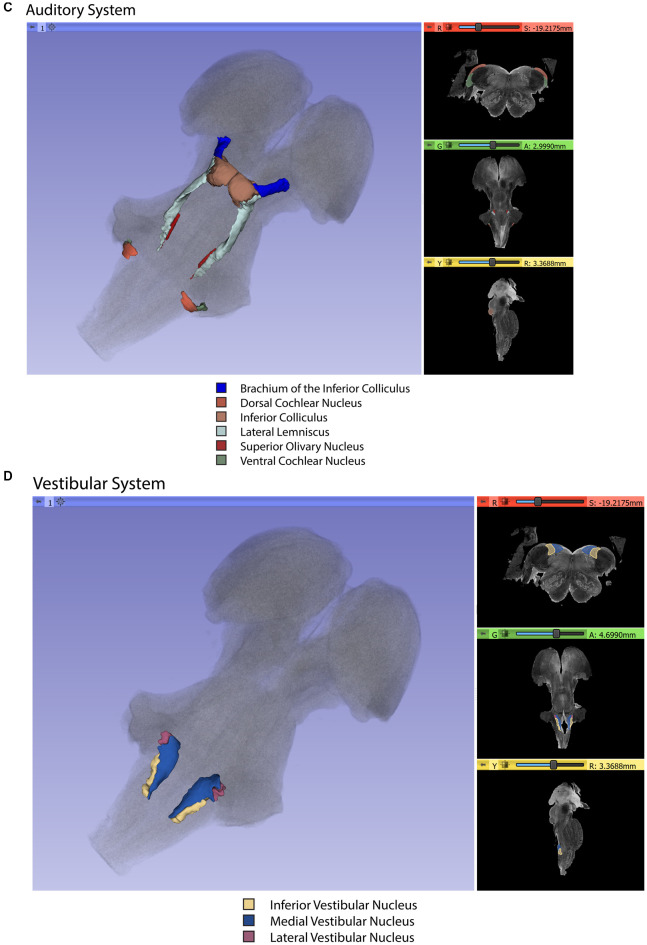

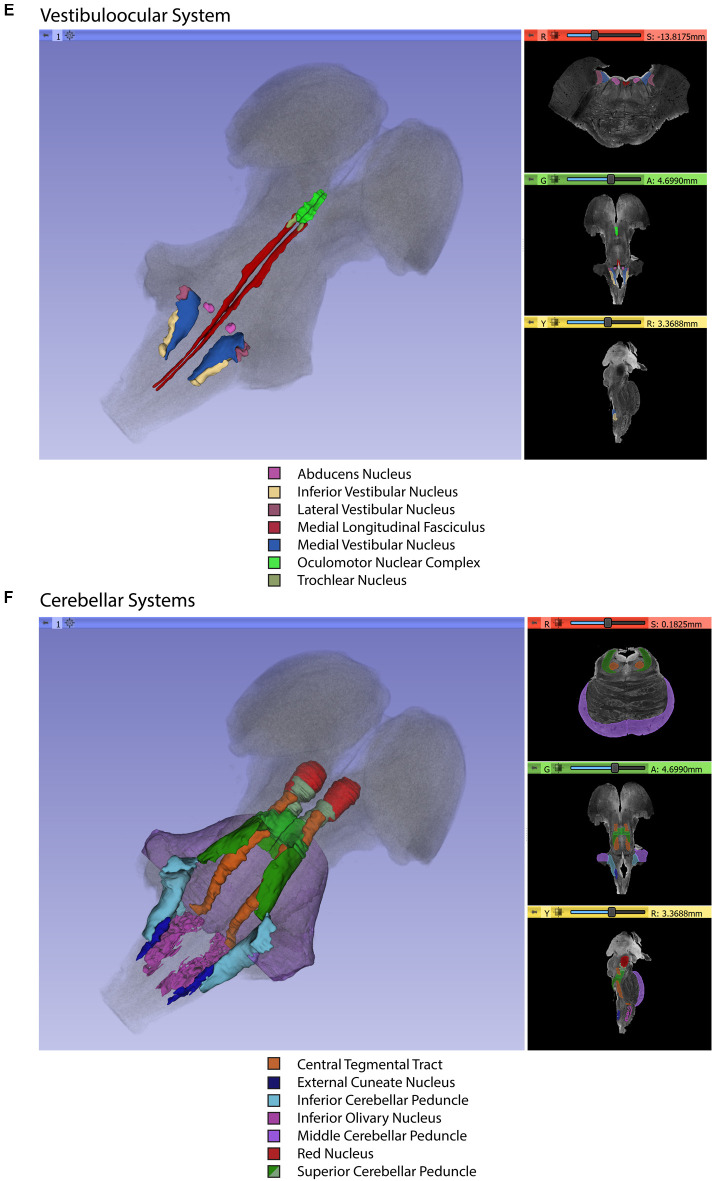

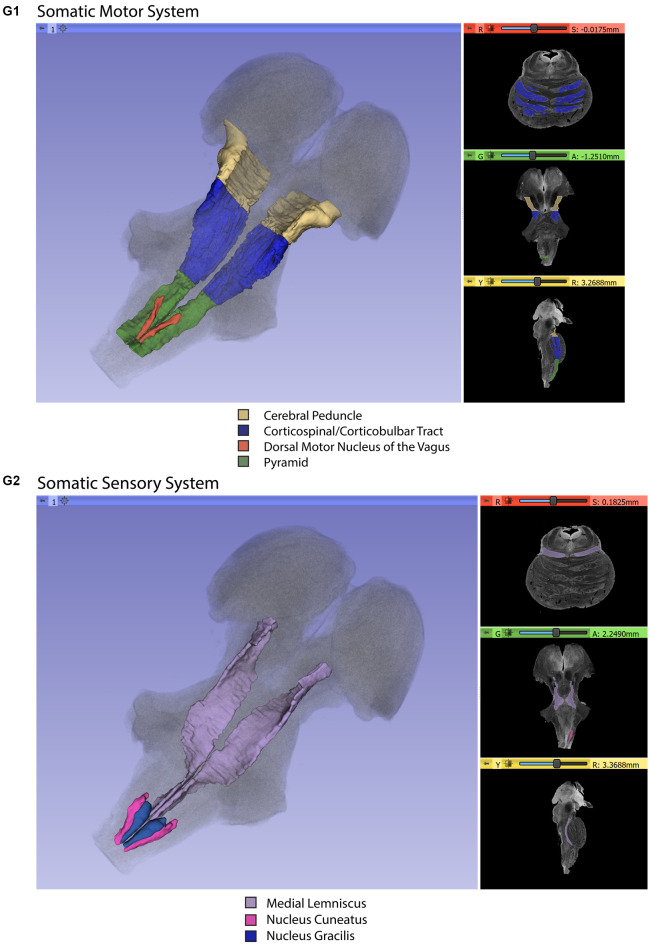

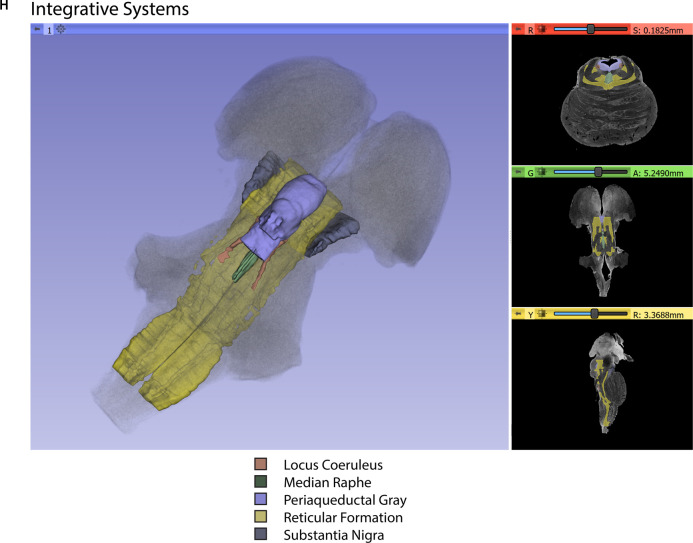

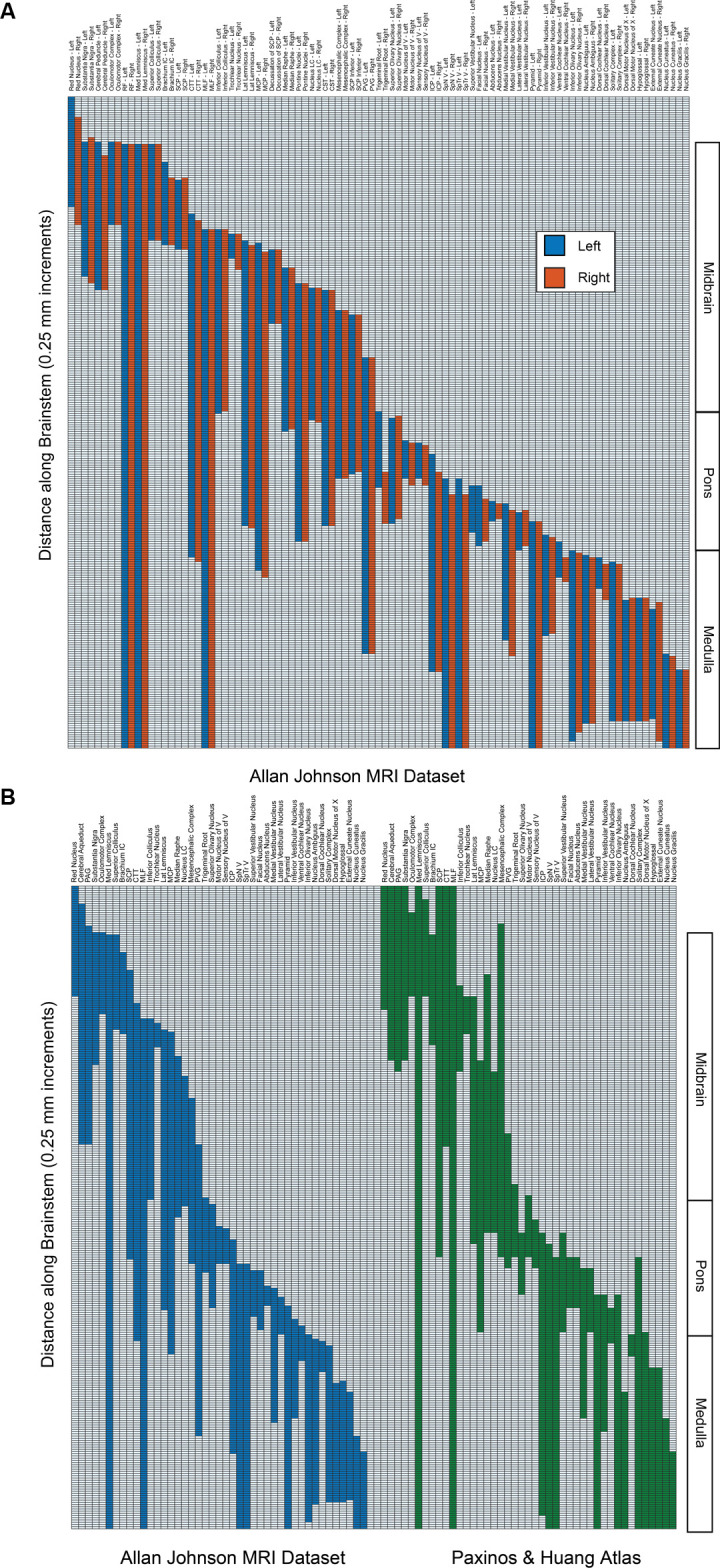

Gross segmentation of the brainstem reflecting its three principal parts, namely midbrain, pons, and medulla, was readily accomplished. At an individual structure level of analysis, we were able to identify 47 gray and white matter structures within the entire brainstem and the cerebral aqueduct. These consisted of 25 gray matter structures, 22 fiber tracts as well as the cerebral aqueduct. Of the 47 structures identified, we were able to delineate morphometrically all 25 gray matter structures, 16 white matter structures (including the trigeminal root), and the cerebral aqueduct as listed in detail in Table 1 and illustrated in Figure 1 in six representative axial sections. For anatomical reference and clarity, we displayed our results side-by-side with corresponding plates of the Nolte textbook (Nolte et al., 2016; Vanderah, 2018). The latter was done for didactic purposes to aid the student of brainstem anatomy who is not sufficiently familiar with this complex structure. The results observed in our analysis matched the topography reported by classical atlases, namely those of Haines (1991), Paxinos and Huang (1995), and Tona et al. (2017). The size of our brainstem dataset (i.e., 54.2 mm in length) was comparable to the sample used by Tona et al. (2017; i.e., 54.02 mm) by 99.7%, and with the brainstem analyzed by Paxinos and Huang (1995; i.e., 59 mm) by 91.6%. The topographical relationships among the various gray and white matter structures and the ventricular complex also met expectations based on traditional neuroanatomy. More specifically, a comparison between left and right structures in our analysis showed an overall 99% correspondence and a spatial overlap of 97%, as shown in Figure 2A. Moreover, the overall segmentation of individual ROIs showed a correspondence of 88% and an overall spatial overlap of our segmentations of 87% as compared to Paxinos and Huang (1995). The latter comparison is represented numerically in Table 2 and graphically in Figure 2B. The histological sectioning and processing procedures used to generate the atlases (Olszewski and Baxter, 1982; Paxinos and Huang, 1995) are likely the main source of the differences in the overlap between the atlases and the present material. At another level of analysis, the neural systems associated with brainstem structures were delineated and reconstructed in three-dimensional space as shown in Figure 3. These were the motor and sensory systems of the face (Figure 3A), the oculomotor system (Figure 3B), the auditory system (Figure 3C), the vestibular system (Figure 3D), the vestibuloocular system (Figure 3E), the cerebellar systems (Figure 3F), the motor and sensory body systems (Figures 3G1,G2) and the integrative systems (Figure 3H). Finally, we produced a full segmentation as a set of 291 axial atlas plates in the Supplementary Material.

Table 1.

List of gray and white matter structures to relate brainstem structures as defined by Nolte et al. (2016) and Vanderah (2018) with the present study and with the terminologia neuroanatomica (ten Donkelaar et al., 2017, 2018; FIPAT.library.dal.ca).

| Gray matter structures | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nolte | Present study | Terminologia neuroanatomica (TNA) | TA98 ID |

| Abducens nucleus | Abducens nucleus | Nucleus nervi abducentis | A14.1.05.411 |

| Cochlear nuclei | Dorsal cochlear nucleus Ventral cochlear nucleus | Nucleus cochlearis posterior Nucleus cochlearis anterior | A14.1.04.248 A14.1.04.249 |

| Dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus | Dorsal motor nucleus of X | Nucleus posterior nervi vagi | A14.1.04.229 |

| Edinger-Westphal nucleus | Oculomotor complex | Nucleus accessorii nervi oculomotorii | A14.1.06.303 |

| External cuneate nucleus | External cuneate nucleus | Nucleus cuneatus accessories | A14.1.04.209 |

| Facial motor nucleus | Facial nucleus | Nucleus nervi facialis | A14.1.05.412 |

| Hypoglossal nucleus | Hypoglossal | Nucleus nervi hypoglossi | A14.1.04.227 |

| Inferior colliculus | Inferior colliculus—Anatomical Inferior colliculus—CN | Colliculus inferior | A14.1.06.014 |

| Inferior olivary nucleus | Inferior olivary nucleus | Nucleus olivaris principalis | A14.1.04.220 |

| Locus coeruleus | Nucleus locus coeruleus | Nucleus caeruleus | A14.1.05.436 |

| Nucleus ambiguus | Nucleus ambiguus | Nucleus ambiguus | A14.1.04.253 |

| Nucleus cuneatus | External cuneate nucleus Nucleus cuneatus | Nucleus cuneatus | A14.1.04.206 |

| Nucleus gracilis | Nucleus gracilis | Nucleus gracilis | A14.1.04.202 |

| Nucleus of the solitary tract | Solitary complex | Nuclei tractus solitarii | A14.1.04.230 |

| Oculomotor nucleus | Oculomotor complex | Nucleus nervi oculomotorii | A14.1.06.302 |

| Periaqueductal gray | PAG | Substantia grisea periaquaeductalis | A14.1.06.321 |

| Periventricular gray | PVG | ||

| Pontine nuclei and pontocerebellar fibers | Pontine nuclei | Nuclei pontis | A14.1.05.202 |

| Raphe nuclei | Median raphe Dorsal raphe | Nucleus raphes medianus Nucleus raphes dorsalis | A14.1.05.402 A14.1.05.601 A14.1.06.401 |

| Red nucleus | Red nucleus | Nucleus ruber | A14.1.06.323 |

| Spinal trigeminal nucleus | SpN V | Nucleus spinalis nervi trigemini | A14.1.05.404 A14.1.04.211 |

| Motor nucleus of the trigeminal | Motor nucleus of V | Nucleus motorius nervi trigemini | A14.1.05.410 |

| Sensory nucleus of the trigeminal | Sensory nucleus of V | Nucleus principalis nervi trigemini | A14.1.05.406 |

| Mesencephalic nucleus of the trigeminal | Mesencephalic complex | nucleus mesencephalicus nervi trigemini | A14.1.05.409 |

| Substantia nigra | Substantia nigra | Substantia nigra | A14.1.06.111 |

| Superior colliculus | Superior colliculus | Colliculus superior | A14.1.06.015 |

| Superior olivary nucleus | Superior olivary nucleus | Complexus olivaris superior | A14.1.05.415 |

| Trochlear nucleus | Trochlear nucleus | Nucleus nervi trochlearis | A14.1.06.319 |

| Vestibular nuclei | Inferior vestibular nucleus Lateral vestibular nucleus Medial vestibular nucleus Superior vestibular nucleus | Nucleus vestibularis inferior Nucleus vestibularis lateralis Nucleus vestibularis medialis Nucleus vestibularis superior | A14.1.04.243 A14.1.05.427 A14.1.05.426 A14.1.05.429 |

| White matter structures | |||

| Brachium of the inferior colliculus | Brachium IC | Brachium colliculi inferioris | A14.1.06.012 |

| CTT | Tractus tegmentalis centralis | A14.1.05.325 | |

| Cerebral peduncle | Cerebral peduncle | Pedunculus cerebri | A14.1.06.004 |

| Decussation of the superior cerebellar peduncles | Decussation of SCP | Decussatio pedunculorum cerebellarium superiorum | A14.1.06.217 |

| Inferior cerebellar peduncle | ICP | Pedunculus cerebellaris inferior | A14.1.07.413/ A14.1.04.013 |

| Lateral lemniscus | Lat lemniscus | Lemniscus lateralis | A14.1.05.317 A14.1.06.204 A14.1.08.670 |

| Medial lemniscus | Med lemniscus | Lemniscus medialis | A14.1.04.111 A14.1.06.207 A14.1.08.672 |

| Medial longitudinal fasciculus | MLF | Fasciculus longitudinalis medialis | A14.1.05.304 A14.1.04.113 A14.1.06.209 |

| Middle cerebellar peduncle | MCP | Pedunculus cerebellaris medius | A14.1.07.416 A14.1.05.003 |

| Pyramid | Pyramid | Pyramis medullae oblongatae | A14.1.04.003 |

| Reticular formation | RF | Formatio reticularis | A14.1.00.021 A14.1.05.403 A14.1.06.327 |

| Solitary tract | Solitary complex | Tractus solitarius/Nucleus tractus solitarii | A14.1.04.120/ A14.1.04.230 |

| Spinal trigeminal tract | SpTr V | Tractus spinalis nervi trigemini | A14.1.05.309 A14.1.04.115 |

| Superior cerebellar peduncle | SCP SCP—Inferior | Pedunculus cerebellaris superior | A14.1.07.417 A14.1.05.006 A14.1.06.216 A14.1.06.009 A14.1.08.678 |

| Other structures | |||

| Cerebral aqueduct | Cerebral aqueduct | Aquaeductus mesencephali | A14.1.06.501 |

The last column contains identification codes for the structures as found in the terminologia anatomica viewer (https://taviewer.openanatomy.org). The trigeminal root is not included here because it does not correspond explicitly to the TNA nomenclature.

Figure 1.

Transverse segmented sections through the midbrain (A,B), pons (C,D), and medulla (E,F) of the brainstem. For each subfigure, a hemisected longitudinal view of the brainstem is shown on the left with a white line representing the plane of the section that corresponds to the images in the middle panel. The upper section of the middle panel is an image from the MRI dataset, and the lower picture is a schematic image from Essentials of the Human Brain (Vanderah, 2018) of a comparable brainstem section. The numbers in the schematic figures are recapitulated in the large segmented image on the right to show the correspondence of structures between the MRI dataset and the schematic image. Note that: (1) in some instances, some numbered structures present in the schematic figures do not appear in the segmented MRI image because they could not be reliably identified in the MRI image; and (2) some structures appear in the MRI image but not in the schematic images—these structures are identified by the alphabetical abbreviation and reflect slight differences in the angle of cut or structures that were clear in the MRI but not demarcated in the schematic images. The red nucleus, in particular, appears minimally in the MRI image due to the angle of the section, which was taken at the caudal-most tip of the red nucleus. More specifically, this section represents the level where fibers of the superior cerebellar peduncle enter in the red nucleus. Furthermore, the central tegmental tract, which does not appear in the schematic figure has been identified in the MRI image. Moreover, fibers of the oculomotor nerve traversing the superior cerebellar peduncle are visible in both the MRI image and the schematic figure. Figures from Vanderah (2018) used with permission. Abbreviations: (A) 1. Superior Colliculus, 2. Periaqueductal gray, 3. Cerebral Aqueduct, 4. Brachium of the inferior colliculus, 5. Anterolateral system, 6. Medial lemniscus, 7. The reticular formation, 8. Medial longitudinal fasciculus, 9. Oculomotor nuclear complex (a. Nucleus of Edinger-Westphal), 10. Substantia Nigra pars reticulata, 11. Substantia nigra pars compacta, 12. Red nucleus, 13. Ventral tegmental area, 14. Corticopontine fibers of the Cerebral peduncle, 15. Corticospinal and corticobulbar fibers of the Cerebral peduncle. CTT—Central tegmental tract, SCP—Superior cerebellar peduncle. The CTT was added in the schematic image from Essentials of the Human Brain (Vanderah, 2018) in a dashed line indicated by an asterisk. (B) 1. Inferior colliculus, 2. Periaqueductal gray, 3. Cerebral aqueduct, 4. Lateral lemniscus, 5. Trochlear nucleus, 6. Medial longitudinal fasciculus, 7. Raphe nuclei, 8. Anterolateral system, 9. Medial lemniscus, 10. The reticular formation, 11. Decussation of the superior cerebellar peduncle 12. Corticopontine fibers of the Cerebral peduncle, 13. Corticospinal and corticobulbar fibers of the Cerebral peduncle, 14. Pontine nuclei. CTT—Central tegmental tract, SN—Substantia nigra. The CTT was added in the schematic image from Essentials of the Human Brain (Vanderah, 2018) in a dashed line indicated by an asterisk. (C) 1. Lateral lemniscus, 2. Superior cerebellar peduncle, 3. Locus coeruleus, 4. Periaqueductal gray, 5. Fourth ventricle, 6. Anterolateral system, 7. Medial lemniscus, 8. The reticular formation, 9. Medial longitudinal fasciculus, 10. Raphe nuclei, 11. Corticopontine fibers of the Cerebral peduncle, 12. Pontine nuclei, 13. Corticospinal and corticobulbar fibers. CTT—Central tegmental tract, MCP—Middle cerebellar peduncle, MesNV—Mesencephalic tract and nucleus of trigeminal, XSCP—Decussation of the superior cerebellar peduncle. The CTT was added in the schematic image from Essentials of the Human Brain (Vanderah, 2018) in a dashed line indicated by an asterisk. (D) 6. Vestibular complex of nuclei, 7. Abducens nucleus, *8. The location of the internal genu of the facial nerve is indicated here, although it should be noted that in this MRI image the plane of the section includes both fibers of the facial nerve laterally (16 in this figure) and fibers of the abducens nerve medially (VI), 9. Medial longitudinal fasciculus, 10. Spinal tract of the trigeminal, 11. Spinal nucleus of the trigeminal, 12. Facial motor nucleus, 13. Reticular formation, 14. Raphe nuclei, 15. Middle cerebellar peduncle, 16. Facial nerve fibers, 17. Anterolateral system, 18. Superior olivary nucleus, 19. Medial lemniscus, 20. Trapezoid body, 21. Pontine nuclei, 22. – Corticospinal, corticobulbar, and corticopontine fibers. CTT—Central tegmental nucleus, ICP—Inferior cerebellar peduncle, LL—Lateral lemniscus, MCP—Middle cerebellar peduncle, V—Trigeminal nerve fibers, VI—Abducens nerve fibers. The CTT was added in the schematic image from Essentials of the Human Brain (Vanderah, 2018) in a dashed line indicated by an asterisk. (E) 2. Fourth Ventricle, 3. Inferior cerebellar peduncle, 4. Vestibular nuclei, 5. Solitary tract and nucleus of the solitary tract, 6. Dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus, 7. Hypoglossal nucleus, 8. Medial longitudinal fasciculus, 9. Spinal trigeminal tract, 10. Spinal trigeminal nucleus, 11. Anterolateral system, 12. Nucleus ambiguous, 13. Reticular formation, 14. Inferior olivary nucleus, 15. Medial lemniscus, 16. Raphe nuclei, 17. Hypoglossal nerve fibers, 18. Pyramid. Please note that in the MRI image the cochlear nuclei are not present due to the plane of section. The border of the inferior cerebellar peduncle was extended in the schematic image from Essentials of the Human Brain (Vanderah, 2018) in a dashed line indicated by a double-cross. (F) 1. Nucleus gracilis, 2. Fasciculus cuneatus, 3. Nucleus cuneatus, 4. Solitary tract and nucleus of the solitary tract, 5. Dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus, 7. Spinal trigeminal tract, 8. Spinal trigeminal nucleus, 9. Hypoglossal nucleus, 10. Anterolateral system, 11. Nucleus ambiguous, 12. Reticular formation, 13. Medial longitudinal fasciculus, 14. Medial lemniscus, 15. Raphe nuclei, 16. Pyramid, InfO—Inferior olivary nucleus. The external cuneate nucleus was added in the schematic image from Essentials of the Human Brain (Vanderah, 2018) in a dashed line indicated by a single cross.

Figure 2.

(A) The superior-inferior extent of brainstem structures on the left (blue) and right (red) from the present dataset. Regions are indicated on the abscissa, and the presence of the regions from superior (upper) to inferior (lower) is indicated in 250-micrometer increments on the ordinate. The right-hand side indicates the divisions of the brainstem into midbrain, pons, and medulla. Note that the unpaired cerebral aqueduct and periaqueductal gray are not included. (B) Comparison of the superior-inferior extent of brainstem structures from the present dataset (Allan Johnson, blue) with the Paxinos and Huang (1995) atlas (green). All conventions are as in 2A. Note that some regions that were identified in the present dataset (i.e., reticular formation, pontine nuclei, corticospinal tract, cerebral peduncle) were not identified in the Paxinos and Huang atlas per se and were removed for purposes of clarity.

Table 2.

Ratios of the superior-inferior extent of brainstem structures from the present dataset (Allan Johnson MRI dataset) with the Paxinos and Huang (1995) atlas.

| Structure | Ratio | Structure | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Red Nucleus | 0.89 | Sensory Nucleus of V | 0.77 |

| Cerebral Aqueduct | 1.40 | ICP | 0.76 |

| PAG | 1.18 | SpN V | 0.93 |

| Substantia Nigra | 0.76 | SpTr V | 0.98 |

| Oculomotor Complex | 1.16 | Superior Vestibular Nucleus | 0.47 |

| Medial Lemniscus | 0.92 | Facial Nucleus | 1.17 |

| Superior Colliculus | 0.98 | Abducens Nucleus | 0.39 |

| Brachium IC | 0.74 | Medial Vestibular Nucleus | 0.90 |

| SCP | 0.78 | Lateral Vestibular Nucleus | 0.62 |

| CTT | 1.31 | Pyramid | 0.95 |

| MLF | 0.79 | Inferior Vestibular Nucleus | 0.73 |

| Inferior Colliculus | 0.87 | Ventral Cochlear Nucleus | 1.00 |

| Trochlear Nucleus | 0.65 | Inferior Olivary Nucleus | 0.80 |

| Lateral Lemniscus | 1.12 | Nucleus Ambiguus | 1.21 |

| MCP | 1.19 | Dorsal Cochlear Nucleus | 1.40 |

| Nucleus LC | 0.81 | Solitary Complex | 0.58 |

| Mesencephalic Complex | 0.44 | Dorsal Motor Nucleus of X | 0.60 |

| Median Raphe | 0.62 | Hypoglossal | 0.74 |

| PVG | 2.16 | External Cuneate Nucleus | 0.67 |

| Trigeminal Root | 1.03 | Nucleus Cuneatus | 0.84 |

| Superior Olivary Nucleus | 1.68 | Nucleus Gracilis | 0.90 |

| Motor Nucleus of V | 0.61 |

Note that some regions that were identified in the present dataset (i.e., reticular formation, pontine nuclei, corticospinal tract, cerebral peduncle) were not identified in the Paxinos and Huang atlas per se and were removed for purposes of clarity. Abbreviations: CTT, central tegmental tract; IC, inferior colliculus; ICP, inferior cerebellar peduncle; LC, locus coeruleus; MCP, middle cerebral peduncle; MLF, medial longitudinal fasciculus; PAG, periaqueductal gray; PVG, periventricular gray; SCP, superior cerebellar peduncle; SpNV, the spinal nucleus of the trigeminal; SPTrV, spinal tract of the trigeminal; X, vagus.

Figure 3.

Three-dimensional reconstructions of selected brainstem systems. For each subfigure, the three-dimensional rendering is overlaid on a volume rendering of the brainstem, and selected slices in the axial (red), coronal (yellow), and sagittal (green) planes are illustrated on the right. To generate the three-dimensional structures, a 0.5 mm median smoothing kernel was applied. (A) Cranial sensorimotor system, (B) Oculomotor system, (C) Auditory system, (D) Vestibular system, (E) Vestibuloocular system, (F) Cerebellar systems, (G) Motor (G1) and Sensory (G2) systems of the body, (H) Integrative systems. Note that the most easily resolvable structures on the MRI images were segmented and reconstructed and that these images do not encapsulate all component structures of each system.

Discussion

In this study, we localized and delineated the principal structures of the human brainstem using an MRI ex vivo ultrahigh-resolution dataset with properties largely comparable to histological representation. More specifically, we volumetrically identified 47 gray (viz., 25) and white matter (viz., 22) structures in the brainstem based on an ex vivo human T2-weighted MRI dataset of 50-micron spatial resolution. Furthermore, we were able to delineate morphometrically all 25 gray matter structures and 16 of the 22 white matter structures. To our knowledge, this has not been previously achieved in MRI-based morphometric analysis. Moreover, we assembled individual structures into neural systems specifically serving cranial nerve, conduit, and integrative functions.

The brainstem is becoming a major focus in clinical and basic neuroscience due to our current ability to image it volumetrically at resolutions previously inaccessible to MRI. It is a structure that appears early in evolution and has been studied structurally across several species (Ariëns-Kappers et al., 1960; Angevine, 1961; Emmers and Akert, 1963; Berman, 1968; Madigan and Carpenter, 1971; Paxinos and Huang, 1995; Franklin and Paxinos, 1997; Nieuwenhuys et al., 1998; Paxinos, 1999; Paxinos et al., 1999, 2000; Naidich et al., 2009; Baizer, 2014). Although, relatively small in size, this brain structure is associated with vital biological integrative functions such as consciousness, motivation, pain, and reward as well as cranial nerve biology and conduit somatosensory and motor functions. Thus, the brainstem is critical for a complete understanding of brain structure-function relationships. We expect our anatomical analysis to be of use to neuroanatomists as well as clinical and basic neuroscientists.

Early students of neuroanatomy who macrodissected the human brain provided gross, approximate descriptions of the brainstem as a whole and its component parts, namely the midbrain, pons and medulla (e.g., Vesalius, 1543; Varoli, 1573; Diemerbroeck, 1689; Haller, 1747; von Baer, 1837). Microscopic studies of the human brainstem have provided comprehensive descriptions of this structure since the early 1900s. A historical review of these aspects of the human brainstem has been provided by Olszewski and Baxter (1982) and can be highlighted briefly as follows. Jacobsohn’s drawings in particular, given their anatomical accuracy, have served as a classical guideline for anatomical work regarding the brainstem nuclei (Jacobsohn, 1909). The classical work of Ziehen (1903) has provided extensive descriptions of cyto- and myelo-architecture of fiber pathways in the brainstem. Subsequent cytoarchitectonic studies have provided additional detail and more refined visualization with the use of photomicrographs (Gagel and Bodechtel, 1930; Stern, 1935; Crosby and Woodburne, 1943; Riley, 1943). More recently, the atlases of Paxinos and Huang (1995) and Tona et al. (2017) stand out for their in-depth descriptions of brainstem nuclei cytoarchitecture and topography. It should be noted that the Paxinos and Huang (1995) atlas provides unprecedented detail and coverage of not only nuclei but also fiber tracts in the human brainstem—almost twice the number of fiber pathways compared to other atlases. Given that in the present study we needed to simplify and adapt the brainstem nuclear and fiber tract analysis to the neuroimaging data under analysis, we used primarily the Tona et al. (2017) atlas as well as the atlas of Haines (1991), while the Paxinos and Huang (1995) atlas served as the final comparison reference and testbed for our analyses. The results of the analyses were also consistent with Naidich et al. (2009). Finally, for didactic purposes we have displayed the human brainstem gray and white matter structures in six classical axial planes, namely, through the rostral and caudal midbrain, rostral and caudal pons, rostral and caudal medulla, as generally accepted in neuroanatomy following, for example, the Nolte textbook (Nolte and Angevine, 1995; Nolte, 1999; Nolte et al., 2016; Vanderah, 2018).

With the advent of MRI, there have been several studies addressing the in vivo and non-invasive visualization of the gray and white matter of the human brainstem (Salamon et al., 2005; Kamali et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2011; Linnman et al., 2012; Bianciardi et al., 2015, 2018; Meola et al., 2016; Sclocco et al., 2018). MRI-based morphometry has examined the morphological and volumetric characterization of the brainstem since the early 1990s (Filipek et al., 1994). Although the gross nature of these investigations precluded their addressing the fine architecture of the brainstem, these early morphological studies indicated the great potential of neuroimaging to visualize this structure in vivo and non-invasively. As neuroimaging technology and methods of analysis evolved, brainstem anatomical analysis advanced using structural T1- and T2-weighted MRI as well as diffusion MRI (dMRI) and dMRI tractography. Pioneering morphometric studies with structural imaging measured the major components of the brainstem, namely the midbrain, pons, and medulla, and were used to localize functional activation of specific cranial nerve nuclei in combination with task-specific fMRI acquisitions (e.g., DaSilva et al., 2002). Furthermore, specific nuclear masses have been identified and labeled using T1- and T2-weighted MRI (Linnman et al., 2012; Bianciardi et al., 2015, 2016, 2018; Tona et al., 2017). Moreover, using dMRI tractography, several fiber tract connections have been identified and delineated in the brainstem. Although most studies have addressed principally major motor and sensory connections such as the corticospinal tract (e.g., Salamon et al., 2005; Meola et al., 2016), the cerebellar peduncles (Meola et al., 2016), the corticopontocerebellar pathways (Habas and Cabanis, 2007), and the medial and lateral lemniscus (Kamali et al., 2009; Meola et al., 2016), there are also investigations focusing on finer connections such as the rubrospinal tract (Yang et al., 2011; Meola et al., 2016), spinothalamic tract, medial longitudinal fasciculus, dorsal longitudinal fasciculus (Meola et al., 2016) and central tegmental tract (Kamali et al., 2009; Meola et al., 2016).

In the context of an increasing body of information in the anatomical brainstem imaging field, to our knowledge the present study takes a step forward in identifying and delineating the greatest number of nuclear structures to date. This was achieved principally because of the high spatial resolution, and the very high signal quality of the dataset we analyzed. Importantly, the anatomical analysis was done by expert neuroanatomists using 3D Slicer segmentation and visualization tools. Finally, comparisons of the delineated nuclear structures were done with guidance from classical brainstem textbooks and atlases portraying the precise cytoarchitecture and topography of the human brainstem nuclei. The present analysis represents an advancement concerning traditional histological atlases, given the volumetric nature of our data and our ability to use MRI at a 50-micron resolution. Furthermore, histological slices often have physical artifacts and geometric distortions (e.g., small tears due to tissue folding) and are difficult to reconstruct as a single 3D object. The inherent 3D nature of MRI reduces tissue distortions, leading to more accurate representations in MR-based atlases. Moreover, in vivo histology is not possible; thus, relating histological atlases to in vivo imaging can be problematic. In contrast, MRI is the primary modality for structural brain imaging, and MR-based atlases appear to be more appropriate and easier to register, and thus to inform more accurately in vivo MR-based studies or interventions.

By delineating the structural parts of the brainstem, we have provided a viable means of visualizing in 3D the different cranial nerve systems, conduit systems, and integrative systems. This is a useful method for illustrating and understanding brainstem anatomy for basic neuroscientists as well as neurologists, psychiatrists, and neurosurgeons. As a result of this endeavor, 3D visualizations in the publicly available platform of 3D Slicer allow the student of the brainstem to use the atlas provided herein readily and relatively simply as a learning and teaching tool for this highly complex domain of neuroanatomy.

Functional Considerations

Brainstem functions can be generally categorized in a didactic, simplistic manner as conduit, cranial nerve, and integrative. The topographic arrangement of the brainstem with the spinal cord, cerebellum, and cerebrum makes it a natural route of passage for the numerous fiber tracts interconnecting these structures, thus justifying its role as a conduit of fibers of passage. In this study, we labeled 22 and delineated 16 of these fiber pathways, as shown in Table 1 and Figures 1, 3. It should be noted, however, that fibers of passage may also course through the nuclei of the midbrain, pons, and medulla. Although three of the cranial nerves, namely olfactory (cranial nerve I), optic (cranial nerve II), and accessory (cranial nerve XI), do not project primarily or directly to the brainstem, the other nine are anatomically associated with the brainstem. Herein, we were able to label the majority of cranial nerve nuclei, namely those of cranial nerves III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII, IX, X, and XII in greater detail, as shown in Table 1 and Figures 3A–E. As such, the main associated functions are sensory, i.e., facial and taste, hearing, equilibrium, visceral thoracic and abdominal, chemoceptive and baroceptive, as well as motor, i.e., eye movements, pupil and lens function, chewing, facial expression, swallowing, speech, visceral thoracic and abdominal as well as tongue movements. The most intriguing and least explored role of the brainstem relates to its integrative functions. This is especially apparent from a behavioral point of view, given the brainstem’s involvement in complex state-dependent functions such as consciousness or emotion (Mesulam, 2000; Solms and Turnbull, 2002). Briefly, several integrative functions take place at the level of the midbrain, pons and medulla, dealing with regulation of consciousness and arousal (Moruzzi and Magoun, 1949; Solms and Turnbull, 2002; Edlow et al., 2012), autonomic visceral activity (Janig, 2008; Nieuwenhuys, 2008; Pattinson et al., 2009; Macefield and Henderson, 2010; Nolte et al., 2016), stress response (Feldman and Saphier, 1985; Feldman et al., 1995), pain (Eippert et al., 2009; Heinricher et al., 2009; Napadow et al., 2009; Linnman et al., 2012; Menant et al., 2016), and complex motor and sensory processing (Carpenter and Sutin, 1983; Guimaraes et al., 1998; Nolte et al., 2016). A critical role in integrative functions is served by the reticular formation, as reflected structurally by its diffuse pattern of connectivity with several other parts of the brain. Furthermore, cell groups that are sources of major neurotransmission systems in the brain are localized in the brainstem, namely the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area (VTA; dopamine), locus coeruleus (noradrenaline), raphe nuclei (serotonin) and reticular formation (acetylcholine; e.g., Nieuwenhuys, 2012). All structures involved in the aforementioned functions were identified in the present study. It should be noted that the reticular formation and periaqueductal gray were labeled as single regions of interest, given the limitations in spatial resolution and contrast characteristics of our dataset for visualizing individual cell groups.

Clinical Considerations

Alterations of brainstem structure have been and remain a current matter of relevance in neurological and neurosurgical clinical practice. Lesions of the brainstem such as embolic or hemorrhagic strokes and tumors can affect the conduit, cranial nerve, and integrative functions of the brainstem. In addition to classical neurological syndromes associated with cranial nerve alterations, such as Weber’s syndrome, medial medullary syndrome, and lateral medullary syndrome, which are diagnosed using the traditional neurological examination, other clinical conditions with brainstem involvement have been of recent interest. This is of particular note given the therapeutic interventions that can be applied using deep brain stimulation (DBS) for neuromodulation. Duret’s work on the involvement of the tegmental reticular formation, thalamic and extra-thalamic pathways as well as anterior forebrain circuits in alterations of consciousness has elucidated the role of lesions at the diencephalon-mesencephalic junction in coma and prolonged disorders of consciousness (Duret, 1955). Anatomical visualization of such structures and circuits is of clinical relevance given the therapeutic potential of neuromodulation of the brainstem (Fridman and Schiff, 2014). Interestingly, the cholinergic pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus, which projects to the thalamus and is involved in conscious behavior, is also involved in gait-balance control and may be a potential therapeutic target for postural and gait disorders in Parkinson’s disease (Wang et al., 2017). Neurochemical modulation of neurotransmitter systems arising in brainstem nuclei is of interest in neuropsychiatric practice given the involvement of transmitters in a variety of syndromes. More specifically, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are routinely used as antidepressants due to their ability to enhance the levels of these neurotransmitters, whereas dopamine antagonists have potent antipsychotic effects by blocking dopamine receptors (e.g., Schwartz et al., 2012). Furthermore, cholinergic agents are used in neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease (e.g., Mesulam et al., 1989; Nolte et al., 2016).

Limitations and Future Studies

Given the quality of the imaging dataset used herein, a cogent way of viewing limitations is by comparing these data with histological observations at the microscopic level. A critical student of neuroanatomy always has as the gold standard of analysis a microscopic level of explanation. Neuroimaging is still a few steps away, perhaps by a factor of 10 in spatial resolution, from reaching this level of visualization, although it seems this is rapidly approaching. In this study, we were able to delineate 25 nuclear masses and 16 fiber pathways in the human brainstem using a 50-micron spatial resolution in a postmortem human brainstem. This is still far from the detail provided by microscopic histological examination, where brainstem nuclei and fiber tracts have been identified and delineated using such techniques. It should be noted that in the present study the reticular formation was delineated as a region of interest by the exclusion of other structures and guided by histological atlases; the reticular formation per se could not be visualized with certainty using the current imaging methods. This limitation also applies to the description of the systems, such as the vestibuloocular system, which has more connections than were visualized in the current dataset. We recognize as well that certain boundaries of the ROIs segmented in this investigation may change as the state of MRI technology and neuroanatomical knowledge grows. We will publish updates in an on-line repository as the present structural borders may be modified as we receive feedback.

Future studies using combined high-resolution MRI datasets with their histological sections for comparison (Makris et al., 2013) should provide further validation and accuracy of anatomical delineations in brainstem anatomy. These approaches will also permit a formal evaluation of the variability in volume and extent of regions of the human brainstem. To date, such variability in the human brainstem has been incompletely studied (Andrew and Watkins, 1969; Afshar, 1978; Blood et al., 2012); more detailed knowledge will be a critical step in understanding normal and abnormal brainstem anatomy.

As MRI technology advances it is expected that higher resolution datasets than the one used in the present study will become available. Thus, histological analyses should be done in these samples as well in a co-registered fashion with the MRI datasets for precise and valid comparisons. In addition to the greater level of structural detail that these types of comparison will produce, they are also expected to generate a more complete description of brainstem systems.

Conclusions

Using a high-resolution MRI postmortem dataset of the human brainstem and the 3D Slicer platform set of tools for image analysis, we were able to identify and delineate a large number of nuclear masses, the largest so far to our knowledge. Also, we identified and delineated most of the sizeable brainstem white matter fiber tracts of conduit and interconnecting nature.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

NM, RK, EY, RR, EC, and GJ conceived the project. NM, RR, PW-B, IN, and GP analyzed the data and prepared the figures. NM wrote the first draft of the manuscript, which was read and revised by all the authors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript has been released as a pre-print at BioRXIV (Makris et al., 2019).

Funding. This research was supported in part by National Institute of Health (NIH) grants R01 MH112748 (to SB, MK, and NM), R01 MH111917 (to YR and NM), R21 DA042271 and K24 MH116366 (to NM) and NIH grants P41 EB015902, P41 EB015898, R01 CA235589, and HHSN261200800001E (to RK, Professor of Radiology, Harvard Medical School, USA; Director, Surgical Planning Laboratory, Department of Radiology, and Robert Greenes Distinguished Director of Biomedical Informatics, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, USA; Professor of Medical Image Computing, University of Bremen Institutsleiter, Fraunhofer MEVIS, Bremen, Germany). NM was a Fellow at the Hanse-Wissenschaftskolleg Institute for Advanced Study, Delmenhorst, Germany while working on this study.

1Note that the neuroanatomical definition of pons refers strictly to the ventral protrusion of the metencephalon and does not include the pontine tegmental nuclei (the pons Varoli, see ten Donkelaar et al., 2018).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnana.2020.00040/full#supplementary-material.

References

- Afshar F. (1978). Stereotaxic Atlas of the Human Brainstem and Cerebellar Nuclei: A Variability Study. New York City, NY: Raven Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal M., Zhang J., Pletnikova O., Crain B., Troncoso J., Mori S. (2013). Feasibility of creating a high-resolution 3D diffusion tensor imaging based atlas of the human brainstem: a case study at 11.7 T. NeuroImage 74, 117–127. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.01.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrew J., Watkins E. S. (1969). A Stereotaxic Atlas of the Human Thalamus and Adjacent Structrures; A Variability Study. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Angevine J. B. (1961). The Human Cerebellum: An Atlas of Gross Topography in Serial Sections. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Ariëns-Kappers C. U., Huber G. C., Crosby E. C. (1960). The Comparative Anatomy of the Nervous System of Vertebrates, Including Man. New York, NY: Hafner Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Baizer J. S. (2014). Unique features of the human brainstem and cerebellum. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 8:202. 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beissner F. (2015). Functional MRI of the brainstem: common problems and their solutions. Clin. Neuroradiol. 25, 251–257. 10.1007/s00062-015-0404-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman A. L. (1968). The Brainstem of the Cat: A Cytoarchitectonic Atlas With Stereotaxic Coordinates. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bianciardi M., Strong C., Toschi N., Edlow B. L., Fischl B., Brown E. N., et al. (2018). A probabilistic template of human mesopontine tegmental nuclei from in vivo 7T MRI. NeuroImage 170, 222–230. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.04.070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianciardi M., Toschi N., Edlow B. L., Eichner C., Setsompop K., Polimeni J. R., et al. (2015). Toward an in vivo neuroimaging template of human brainstem nuclei of the ascending arousal, autonomic and motor systems. Brain Connect. 5, 597–607. 10.1089/brain.2015.0347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianciardi M., Toschi N., Eichner C., Polimeni J. R., Setsompop K., Brown E. N., et al. (2016). In vivo functional connectome of human brainstem nuclei of the ascending arousal, autonomic, and motor systems by high spatial resolution 7-Tesla fMRI. MAGMA 29, 451–462. 10.1007/s10334-016-0546-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blessing W. W., Benarroch E. E. (2012). “Lower brainstem regulation of visceral, cardiovascular, and respiratory function,” in The Human Nervous System, 3rd Edn. eds, Mai J. K., Paxinos G. (Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier; ), 1058–1073. [Google Scholar]

- Blood A. J., Kuster J. K., Woodman S. C., Kirlic N., Makhlouf M. L., Multhaupt-Buell T. J., et al. (2012). Evidence for altered basal ganglia-brainstem connections in cervical dystonia. PLoS One 7:e31654. 10.1371/journal.pone.0031654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büttner-Ennever J. A., Horn A. K. E. (2014). Olszewski and Baxter’s Cytoarchitecture of the Human Brain Stem. 3rd Edn. Basel, Switzerland: Karger. [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese E., Hickey P., Hulette C., Zhang J., Parente B., Lad S. P., et al. (2015). Postmortem diffusion MRI of the human brainstem and thalamus for deep brain stimulator electrode localization. Hum. Brain Mapp. 36, 3167–3178. 10.1002/hbm.22836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter M., Sutin J. (1983). Human Neuroanatomy. 8th Edn. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby E. C., Woodburne R. T. (1943). The nuclear pattern of the non-tectal portions of the midbrain and isthmus in primates. J. Comp. Neurol. 79, 441–482. 10.1002/cne.900780311 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlström A., Fuxe K. (1964). Evidence for the existence of monoamine-containing neurons in the central nervous system. I Demonstration of monoamines in the cell bodies of the brain stem neurons. Acta Physiol. Scand. 62, 1–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damasio A. (2010). Self Comes to Mind: Contstructing the Conscious Brain. 1st Edn. New York, NY: Pantheon/Random House. [Google Scholar]

- DaSilva A. F. M., Becerra L., Makris N., Strassman A. M., Gonzalez R. G., Geatrakis N., et al. (2002). Somatotopic activation in the human trigeminal pain pathway. J. Neurosci. 22, 8183–8192. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-18-08183.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deistung A., Schäfer A., Schweser F., Biedermann U., Güllmar D., Trampel R., et al. (2013). High-resolution MR imaging of the human brainstem in vivo at 7 tesla. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 7:710. 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diemerbroeck I. V. (1689). The Anatomy of Human Bodies. London: William Salmon. [Google Scholar]

- Duret R. L. (1955). A rare and little known hemorrhagic syndrome. Brux. Med. 35, 797–800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvernoy H. M. (1995). The Human Brainstem and Cerebellum. New York, NY: Spring-Verlag/Wein. [Google Scholar]

- Edlow B. L., Mareyam A., Horn A., Polimeni J. R., Witzel T., Tisdall M. D., et al. (2019). 7 Tesla MRI of the ex vivo human brain at 100 micron resolution. Sci. Data 6:244. 10.1101/649822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edlow B. L., Takahashi E., Wu O., Benner T., Dai G., Bu L., et al. (2012). Neuroanatomic connectivity of the human ascending arousal system critical to consciousness and its disorders. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 71, 531–546. 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3182588293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eippert F., Bingel U., Schoell E. D., Yacubian J., Klinger R., Lorenz J., et al. (2009). Activation of the opioidergic descending pain control system underlies placebo analgesia. Neuron 63, 533–543. 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmers R., Akert K. (1963). A Stereotaxic Atlas of the Brain of the Squirrel Monkey (Saimiri Sciureus). Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fedorov A., Beichel R., Kalpathy-Cramer J., Finet J., Fillion-Robin J.-C., Pujol S., et al. (2012). 3D slicer as an image computing platform for the quantitative imaging network. Magn. Reson. Imaging 30, 1323–1341. 10.1016/j.mri.2012.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman S., Conforti N., Weidenfeld J. (1995). Limbic pathways and hypothalamic neurotransmitters mediating adrenocortical responses to neural stimuli. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 19, 235–240. 10.1016/0149-7634(94)00062-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman S., Saphier D. (1985). “Role of neurotransmitters and electrophysiological changes in the hypothalamus related to central adrenocortical regulation,” in Neuroendocrine Correlates of Stress, ed. McKerns K. W. (New York, NY: Plenum Press; ), 39–62. [Google Scholar]

- Filipek P. A., Richelme C., Kennedy D. N., Caviness V. S., Jr. (1994). The young adult human brain: an MRI-based morphometric analysis. Cereb. Cortex 4, 344–360. 10.1093/cercor/4.4.344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin K. B. J., Paxinos G. (1997). The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fridman E. A., Schiff N. D. (2014). Neuromodulation of the conscious state following severe brain injuries. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 29, 172–177. 10.1016/j.conb.2014.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagel O., Bodechtel G. (1930). Die topik und feinere histotogie der medulla oblongata und im ponsgebiet mit einem kurzen hinweis auf die gliaverhaltnisse und die hisopathologie. Z. Gesamt. Anat. 29, 172–177. 10.1007/bf02119345 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guimaraes A. R., Melcher J. R., Talavage T. M., Baker J. R., Ledden P., Rosen B. R., et al. (1998). Imaging subcortical auditory activity in humans. Hum. Brain Mapp. 6, 33–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habas C., Cabanis E. A. (2007). Anatomical parcellation of the brainstem and cerebellar white matter: a preliminary probabilistic tractography study at 3 T. Neuroradiology 49, 849–863. 10.1007/s00234-007-0267-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines D. (1991). Neuroanatomy: An Atlas of Structures. 3rd Edn. Baltimore, MD: Urban and Schwarzenberg. [Google Scholar]

- Haller A. V. (1747). Primae Lineae Physiologiae in Usum Praelectionum Academicarum. Gottingen: Vanderhoeck. [Google Scholar]

- Heinricher M. M., Tavares I., Leith J. L., Lumb B. M. (2009). Descending control of nociception: specificity, recruitment and plasticity. Brain Res. Rev. 60, 214–225. 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsohn L. (1909). Über die Kerne des menschlichen Hirnstamms. Berlin: Akademie der Wissenschaften; 1–70. [Google Scholar]

- Janig W. (2008). Integrative Action of the Autonomic Nervous System. Cambridge, MA: Cambidge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kamali A., Kramer L. A., Butler I. J., Hasan K. M. (2009). Diffusion tensor tractography of the somatosensory system in the human brainstem: initial findings using high isotropic spatial resolution at 3.0 T. Eur. Radiol. 19, 1480–1488. 10.1007/s00330-009-1305-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnman C., Moulton E. A., Barmettler G., Becerra L., Borsook D. (2012). Neuroimaging of the periaqueductal gray: state of the field. NeuroImage 60, 505–522. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.11.095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macefield V. G., Henderson L. A. (2010). Real-time imaging of the medullary circuitry involved in the generation of spontaneous muscle sympathetic nerve activity in awake subjects. Hum. Brain Mapp. 31, 539–549. 10.1002/hbm.20885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madigan J., Carpenter M. (1971). Cerebellum of the Rhesus Monkey. Baltimore, MD: University Park Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mai J. K., Paxinos G. (2012). The Human Nervous System. 3rd Edn. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Makris N., Rushmore R. J., Wilson-Braun P., Papadimitriou G., Ny I., Rathi Y. N., et al. (2019). 3D exploration of the brainstem in 50-micron resultion MRI. BioRXIV [Preprint]. 10.1101/768002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makris N., Swaab D. F., van der Kouwe A., Abbs B., Boriel D., Handa R. J., et al. (2013). Volumetric parcellation methodology of the human hypothalamus in neuroimaging: normative data and sex differences. NeuroImage 69, 1–10. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menant O., Andersson F., Zelena D., Chaillou E. (2016). The benefits of magnetic resonance imaging methods to extend the knowledge of the anatomical organisation of the periaqueductal gray in mammals. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 77, 110–120. 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2016.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meola A., Yeh F.-C., Fellows-Mayle W., Weed J., Fernandez-Miranda J. C. (2016). Human connectome-based tractographic atlas of the brainstem connections and surgical approaches. Neurosurgery 79, 437–455. 10.1227/neu.0000000000001224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam M. (2000). Principles of Behavioral and Cognitive Neurology. 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam M. M., Geula C., Bothwell M. A., Hersh L. B. (1989). Human reticular formation: cholinergic neurons of the pedunculopontine and laterodorsal tegmental nuclei and some cytochemical comparisons to forebrain cholinergic neurons. J. Comp. Neurol. 283, 611–633. 10.1002/cne.902830414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moruzzi G., Magoun H. W. (1949). Brain stem reticular formation and activation of the EEG. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1, 455–473. 10.1016/0013-4694(49)90219-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naidich T. P., Duvernoy H. M., Delman B. N., Sorensen A. G., Kollias S. S., Haacke E. M. (2009). Duvernoy’s Atlas of the Human Brainstem and Cerebellum. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Napadow V., Dhond R., Park K., Kim J., Makris N., Kwong K. K., et al. (2009). Time-variant fMRI activity in the brainstem and higher structures in response to acupuncture. NeuroImage 47, 289–301. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.03.060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuys R. (2008). The Human Central Nervous System. 4th Edn. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuys R. (2012). Chemoarchitecture of the Brain. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuys R., ten Donkelaar H. J., Nicholson C. (1998). The Central Nervous System of Vertebrates. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Nolte J. (1999). The Human Brain: An Introduction to Its Functional Anatomy. 4th Edn. St. Louis, Missouri: Mosby. [Google Scholar]

- Nolte J., Angevine J. (1995). The Human Brain: In Photographs and Diagrams. St. Louis, Missouri: Mosby. [Google Scholar]

- Nolte J., Vanderah T., Gould D. (2016). Nolte’s the Human Brain: An Introduction to Its Functional Anatomy. 7th Edn. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski J., Baxter D. (1954). Cytoarchitecture of the Human Brain Stem. 1st Edn. New York, NY: Karger. [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski J., Baxter D. (1982). Cytoarchitecture of the Human Brain Stem. 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Karger. [Google Scholar]

- Panksepp J. (2004). Affective Neuroscience: The Foundations of Human and Animal Neuroscience. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pattinson K. T. S., Mitsis G. D., Harvey A. K., Jbabdi S., Dirckx S., Mayhew S. D., et al. (2009). Determination of the human brainstem respiratory control network and its cortical connections in vivo using functional and structural imaging. NeuroImage 44, 295–305. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G. (1999). Chemoarchitecture Atlas of the Rat Forebrain. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G., Carrive P., Wang P.-Y. (1999). Chemoarchiteture Atlas of the Rat Brainstem. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G., Huang X.-F. (1995). Atlas of the Human Brainstem. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G., Huang X.-F., Toga A. W. (2000). The Rhesus Monkey Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Riley H. (1943). Atlas of the Basal Ganglia, Brain Stem and Spinal Cord Based on Myelin-Stained Material. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Salamon N., Sicotte N., Alger J., Shattuck D., Perlman S., Sinha U., et al. (2005). Analysis of the brain-stem white-matter tracts with diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroradiology 47, 895–902. 10.1007/s00234-005-1439-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz T. L., Sachdeva S., Stahl S. M. (2012). Glutamate neurocircuitry: theoretical underpinnings in schizophrenia. Front. Pharmacol. 3:195. 10.3389/fphar.2012.00195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sclocco R., Beissner F., Bianciardi M., Polimeni J. R., Napadow V. (2018). Challenges and opportunities for brainstem neuroimaging with ultrahigh field MRI. NeuroImage 168, 412–426. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.02.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solms M., Turnbull O. (2002). The Brain and the Inner World: An Introduction to the Neuroscience of Subjective Experience. New York, NY: Other Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stern K. (1935). Der Zellaufbau des menschlichen Mittelhirns. Z. Gesamt. Neurol. Psychiatr. 154, 521–598. 10.1007/bf02865817 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson L. W. (2015). Neuroanatomical Terminology: A Lexicon of Classical Origins and Historical Foundations. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y., Sun W., Toga A. W., Ringman J. M., Shi Y. (2018). A probabilistic atlas of human brainstem pathways based on connectome imaging data. NeuroImage 169, 227–239. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.12.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ten Donkelaar H. J., Broman J., Neumann P. E., Puelles L., Riva A., Tubbs R. S., et al. (2017). Towards a terminologia neuroanatomica. Clin. Anat. 30, 145–155. 10.1002/ca.22809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ten Donkelaar H. J., Kachlik D., Tubbs R. S. (2018). An Illustrated Terminologia Neuroanatomica: A Concise Encyclopedia of Human Neuroanatomy. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG. [Google Scholar]

- Toga A. W., Mazziotta J. (2002). Brain Mapping: The Methods. 2nd Edn. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tona K.-D., Keuken M. C., de Rover M., Lakke E., Forstmann B. U., Nieuwenhuis S., et al. (2017). in vivo visualization of the locus coeruleus in humans: quantifying the test-retest reliability. Brain Struct. Funct. 222, 4203–4217. 10.1007/s00429-017-1464-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderah T. (2018). Nolte’s Essentials of the Human Brain. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Varoli C. (1573). De Nervis Opticis Nonnullis; Aliis Praeter Communem Opinionem in Humano Capite Observatis. Brussells: Culture et Civilization. [Google Scholar]

- Vesalius A. (1543). De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem. Basel: Ex Officina Joannis Oporini. [Google Scholar]

- von Baer K. E. (1837). Uber Entwickelungsgeschichte der Thiere. Beobachtung und Reflexion. Konigsberg: Bontrager. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.-W., Zhang Y.-Q., Zhang X.-H., Wang Y.-P., Li J.-P., Li Y.-J. (2017). Deep brain stimulation of pedunculopontine nucleus for postural instability and gait disorder after parkinson disease: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. World Neurosurg. 102, 72–78. 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.02.110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis T. (1681). The Anatomy of the Brain. Tuckahoe, New York, NY: USV Pharmaceutical Corp. 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Yang H.-S., Kwon H. G., Hong J. H., Hong C. P., Jang S. H. (2011). The rubrospinal tract in the human brain: diffusion tensor imaging study. Neurosci. Lett. 504, 45–48. 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.08.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziehen T. (1903). Anatomie des Zentralnervensystem. Jena: Bardeleben. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All datasets presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.