Abstract

Endovascular aneurysm repair is an established treatment for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. Primary aortocaval fistula is an exceedingly rare finding in ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, with a reported incidence of less than 1%. The presence of an aortocaval fistula used to be an unexpected finding in open surgical repair which often resulted in massive haemorrhage and caval injury. We present a case of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm with an aortocaval fistula that was successfully treated with percutaneous endovascular aneurysm repair under local anaesthesia. Despite a persistent type 2 endoleak the aneurysm sack shrank from 8.4cm to 4.8cm in 12 months. The presence of an aortocaval fistula may have depressurised the aneurysm, resulting in less bleeding retroperitoneally and may have promoted rapid shrinkage of the sac despite the presence of a persistent type 2 endoleak.

Keywords: Aortocaval fistula, Aortic aneurysm, Percutaneous EVAR, Type 2 endoleak, Aortic rupture

Background

Endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) is an established treatment for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm.1 The initial fear that a type 2 endoleak may contribute to continuing bleeding even after successful exclusion of a ruptured aneurysm with EVAR has largely proven to be unsubstantiated.

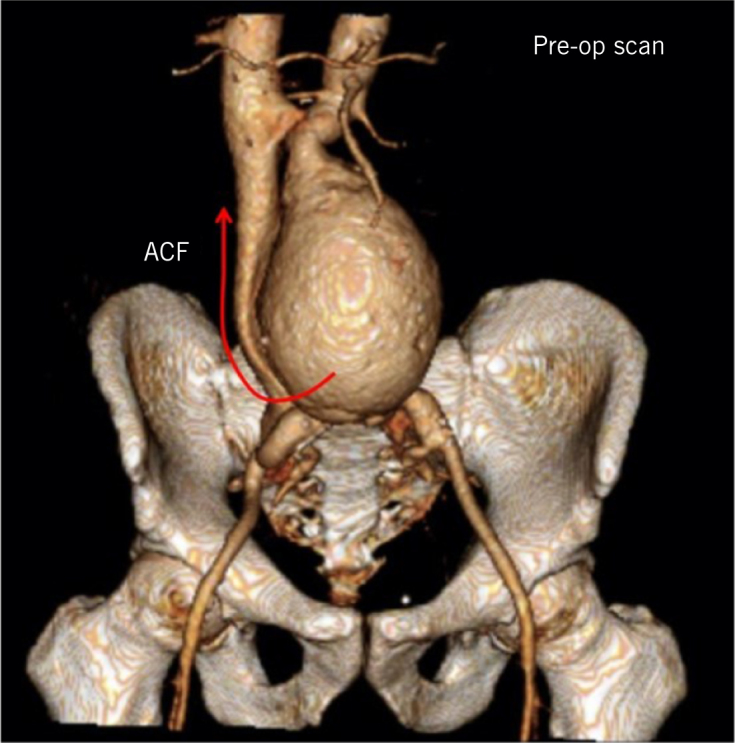

Aortocaval fistulas are an exceedingly rare finding in abdominal aortic aneurysm, with a reported incidence of less than 1%.2 The majority of aortocaval fistulas present without a massive haematoma because the aortic rupture shunts directly into the caval vein. Unlike other aortic ruptures, most aortocaval fistulas are therefore not associated with significant blood loss upon admission. Instead, the most common symptoms are from rapid arteriovenous shunting and secondary venous hypertension and include an abdominal bruit, oliguria, tachycardia, hypotension and right heart failure.2–3 The diagnosis is usually confirmed preoperatively by computed tomography angiogram (CTA) with early caval opacification in the arterial phase (Fig 1).

Figure 1.

Preoperative computed tomography angiogram showing infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm, aortocaval fistula and adjacent haematoma.

Case history

An otherwise fit and healthy 73-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a two-day history of abdominal pain radiating to the back. On arrival, the patient was hypotensive and hypoxic; clinical examination revealed a tender central abdominal mass. CTA demonstrated a fusiform infrarenal ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm with a maximal anteroposterior diameter of 8.7cm and an associated contained retroperitoneal haematoma (axial dimensions of 9 × 7cm). An aortocaval fistula was evident between the aneurysmal aorta and the inferior vena cava (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 2.

Preoperative computed tomography angiogram with three-dimensional reconstruction showing abdominal aortic aneurysm (arrow demonstrates pathway of blood diversion through aortocaval fistula).

The patient underwent emergency percutaneous endovascular aortic repair under local anaesthesia with a bifurcated stent graft (Zenith Flex, Cook® Medical). A completion angiography demonstrated exclusion of the aneurysm without type 1 or 3 endoleak. The patient’s physiology normalised immediately, and he was discharged home on the third postoperative day.

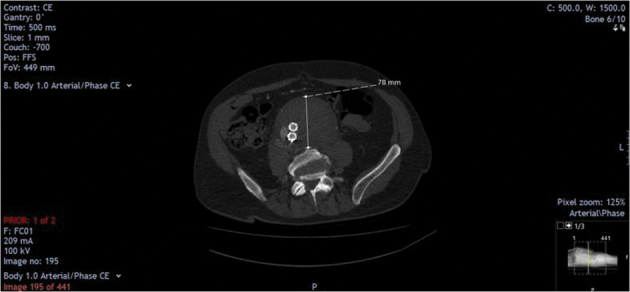

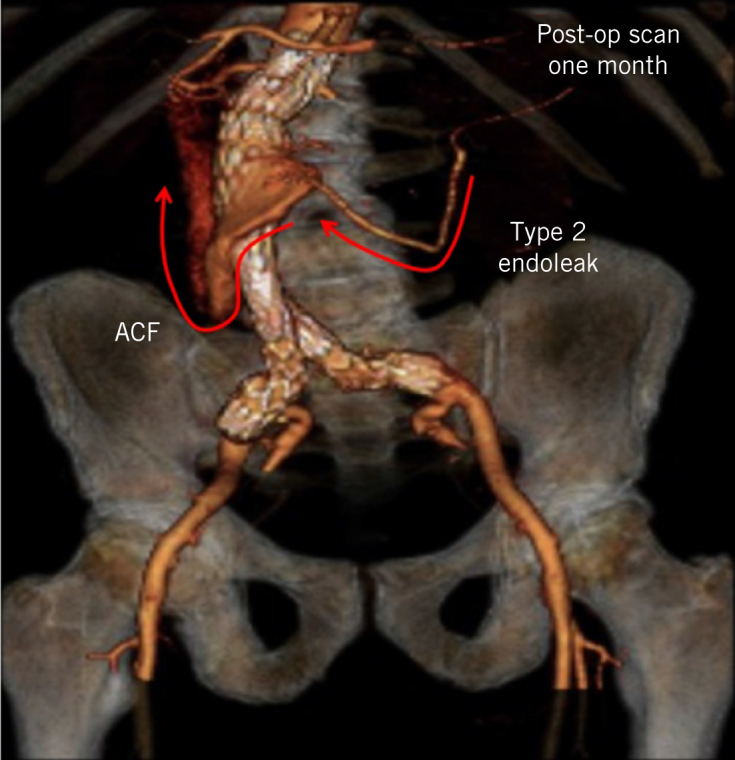

A 30-day duplex scan and triple phase CTA demonstrated a type 2 endoleak from retrograde flow in the inferior mesenteric artery, which was feeding the persistent aortocaval fistula via the sac (Figures 3 and 4). CTA after six months showed a 5.7cm aortic sac with persistent aortocaval fistula and type 2 endoleak (Fig 5). A duplex scan at one year demonstrated shrinkage of the aortic aneurysm from 8.7cm to 4.8cm despite the persistent type 2 endoleak and patent aortocaval fistula. The patient remains well and has no symptoms or echocardiographic evidence of high output cardiac failure.

Figure 3.

Thirty-day postoperative computed tomography angiogram showing stented abdominal aortic aneurysm, type II endoleak and persistent aortocaval fistula.

Figure 4.

Thirty-day postoperative computed tomography angiogram with three-dimensional reconstruction showing stented abdominal aortic aneurysm, type II endoleak and persistent aortocaval fistula (ACF; arrows represent retrograde blood flow through the inferior mesenteric artery into the aortic sac and subsequent diversion into the inferior vena cava).

Figure 5.

Axial view of computed tomography angiogram showing aortic sac and persistent aortocaval fistula and type 2 endoleak.

Discussion

An aortocaval fistula is widely recognised as a risk factor for poor outcome after open surgical repair of a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm.4–6 The presence of the aortocaval fistula was often unrecognised until massive bleeding from the caval fistula surprised the surgeon upon opening the sac. The bleeding occurs despite effective cross-clamping of the aorta and could result in iatrogenic injury of the caval vein.

By contrast, the presence of an aortocaval fistula adds no specific challenge to EVAR. The present case report illustrates the immediate benefit of EVAR for patients with a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm and aortocaval fistula. Until recently, patients with aortocaval fistula were denied EVAR in some of the studies comparing EVAR with open surgical repair for a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. The long-term outcome of EVAR is also favourable with rapid shrinkage of the sac despite a persistent type 2 endoleak. The type 2 endoleak persists due to shunting from the sac into the caval vein via the aortocaval fistula. The sack is depressurised, which explains the rapid shrinkage following EVAR.

It would be technically feasible to obliterate the type 2 endoleak and the aortocaval fistula at follow-up. Retrograde embolisation of the inferior mesenteric artery via the superior mesenteric and middle colic arteries is well established. Alternatively, the vessel can be accessed antegrade by cannulating the sack from the caval vein via the existing aortocaval fistula. However, this has not proven necessary. The sustained arteriovenous shunt keeps the sac depressurised. While the shunt is likely to increase over time, cardiopulmonary failure does not seem to develop because the inferior mesenteric artery is too small a feeding vessel, unable to provide such flow volumes. Significantly larger arteriovenous shunts are routinely inserted for dialysis access.

Our patient complained of sudden onset abdominal pain radiating to the back two days prior to admission. The pain may represent initial retroperitoneal extravasation that progressed until the aortocaval fistula was sufficiently established to depressurise the sac and thereby prevent further haemorrhage into retroperitoneal space.

Hypothetically, an intentional aortocaval fistula could offer a treatment for difficult type 2 endoleaks with chronic sac expansion after EVAR. Successful puncture and stenting from the cava into the sac with subsequent sac shrinkage have indeed been reported (personal communication, Professor Claes Forssell, Sweden). However, a widespread application of this technology seems unlikely for technical difficulties to target the endoleak which often is quite narrow and located remotely from the cava inside a large thrombosed sac. It is therefore tempting to suggest a prophylactic stented aortocaval fistula in patients at high risk of developing symptomatic type 2 endoleaks after EVAR. Such patients may include those with large non-thrombosed aneurysms or patients who require blood thinning. More data and longer follow-up seem necessary before this policy can be advocated.

Conclusion

Patients with a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm and an aortocaval fistula are particularly challenging for open repair and seem to benefit from EVAR. The presence of an aortocaval fistula likely acted to reduce extravascular blood loss into the retroperitoneum, and in the longer term promoted a significant reduction in aneurysm sac size despite the presence of a persistent type 2 endoleak. Further reports and studies are required to assess the potential therapeutic implications of aortocaval fistula in ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm.

References

- 1.IMPROVE Trial Investigators, Powell JT, Sweeting MJ, Thompson MM et al. Endovascular or open repair strategy for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm: 30 day outcomes from IMPROVE randomised trial. BMJ 2014; : f7661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adili F, Balzer JO, Ritter RG et al. Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm with aorto-caval fistula. J Vasc Surg 2004; : 582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ala-Ketola L, Karkola P, Koivisto E. Aorto-caval fistula as complication of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Rofo 1978; : 93–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reckless JP, McColl I, Taylor GW. Aorto-caval fistulae: an uncommon complication of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Br J Surg 1972; : 461–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidt R, Bruns C, Walter M, Erasmi H. Aorto-caval fistula: an uncommon complication of infrarenal aortic aneurysms. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1994; : 208–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wittenstein GJ. Complications of aortic aneurysm surgery: prevention and treatment. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1987; (Suppl 2): 136–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]