Abstract

Background

Patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) have respiratory failure with hypoxemia and acute bilateral pulmonary infiltrates, consistent with ARDS. Respiratory failure in COVID-19 might represent a novel pathologic entity.

Research Question

How does the lung histopathology described in COVID-19 compare with the lung histopathology described in SARS and H1N1 influenza?

Study Design and Methods

We conducted a systematic review to characterize the lung histopathologic features of COVID-19 and compare them against findings of other recent viral pandemics, H1N1 influenza and SARS. We systematically searched MEDLINE and PubMed for studies published up to June 24, 2020, using search terms for COVID-19, H1N1 influenza, and SARS with keywords for pathology, biopsy, and autopsy. Using PRISMA-Individual Participant Data guidelines, our systematic review analysis included 26 articles representing 171 COVID-19 patients; 20 articles representing 287 H1N1 patients; and eight articles representing 64 SARS patients.

Results

In COVID-19, acute-phase diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) was reported in 88% of patients, which was similar to the proportion of cases with DAD in both H1N1 (90%) and SARS (98%). Pulmonary microthrombi were reported in 57% of COVID-19 and 58% of SARS patients, as compared with 24% of H1N1 influenza patients.

Interpretation

DAD, the histologic correlate of ARDS, is the predominant histopathologic pattern identified in lung pathology from patients with COVID-19, H1N1 influenza, and SARS. Microthrombi were reported more frequently in both patients with COVID-19 and SARS as compared with H1N1 influenza. Future work is needed to validate this histopathologic finding and, if confirmed, elucidate the mechanistic underpinnings and characterize any associations with clinically important outcomes.

Key Words: acute respiratory distress syndrome, COVID-19, H1N1 influenza A, histopathology, SARS-CoV-2

Abbreviations: AFOP, acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia; ALI, acute lung injury; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; DAD, diffuse alveolar damage; EM, electron microscopy; OP, organizing pneumonia; PRISMA, preferred reporting items for a systematic review and meta-analysis; RT-PCR, real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has swept throughout the world and captured our undivided attention.1,2 The novelty of the virus and massive burden of respiratory failure associated with it have led to urgent questions about its disease pathogenesis and pulmonary pathology. Both the scientific literature and media suggest that respiratory failure in COVID-19 represents a novel entity.3,4 However, clinical case series of patients with COVID-19 describe respiratory failure with moderate to severe hypoxemia and acute bilateral pulmonary infiltrates consistent with prior reports of ARDS, the most severe form of acute lung injury (ALI).1,2,5 Histopathologically, ALI is associated with a variety of manifestations that include diffuse alveolar damage (DAD), acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia (AFOP), and organizing pneumonia (OP).6

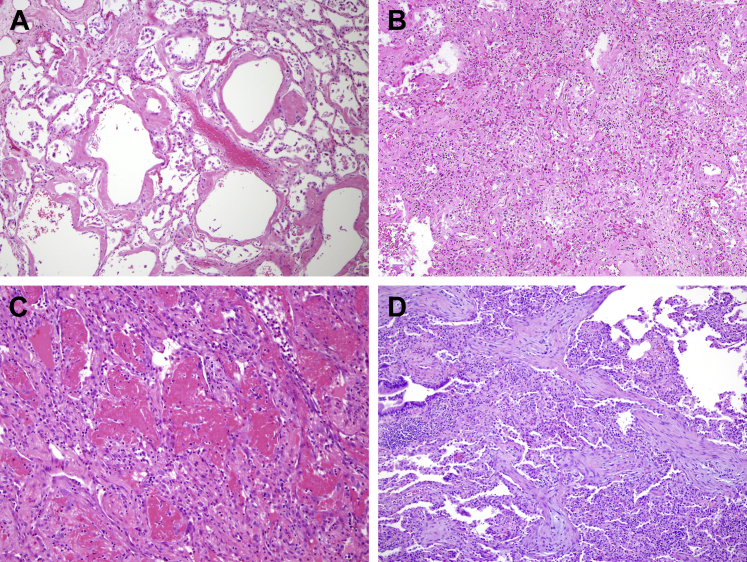

DAD lies on the severe end of the ALI spectrum and is the histopathologic pattern typically associated with clinical ARDS. DAD is caused by “endothelial and alveolar lining cell injury which leads to fluid and cellular exudation,” culminating in physical disruption of the blood-air barrier.7 DAD is divided into three histopathological phases that generally correlate with the time from pulmonary injury: acute (exudative) phase, subacute (organizing) phase, and chronic (fibrotic) phase.6, 7, 8 The acute phase of DAD (Fig 1A) occurs within 1 week of the initial injury and is characterized by intra-alveolar hyaline membranes, edema, and alveolar wall thickening without significant inflammation, unless it arises in conjunction with acute pneumonia.6,7,9 Vascular thrombosis and microthrombosis are frequently observed in DAD, even in the absence of a systemic hypercoagulable state, and they are thought to result from local inflammation.6,7,9,10 Angiographic studies also have confirmed that thrombosis occurs early in ARDS of diverse origins.11

Figure 1.

Histopathologic examples of acute lung injury pathology. A, Acute exudative phase of diffuse alveolar damage (DAD). B, Subacute organizing (or proliferative) phase of DAD. C, Acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia (AFOP). D, Organizing pneumonia (OP).

The subacute phase (Fig 1B) of DAD occurs approximately 1 week after the initial pulmonary injury and is characterized by microscopic organization of the fibrin followed by fibroblast migration and secretion of young “loose” collagen.6,7,9 Hyaline membranes become slowly incorporated into organizing fibrotic tissue, which begins to appear in airspaces, alveolar ducts, and alveolar walls.6,7,9 Reactive atypical changes in type II pneumocytes and squamous metaplasia may be present.6,7,9 Some cases of DAD will ultimately resolve, whereas others evolve into a chronic fibrotic phase (weeks to months after the initial injury) with progressive architectural remodeling and interstitial fibrosis.6,7,9 In the extreme, these changes may resemble usual interstitial pneumonitis, the histopathological correlate of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.6,7,9

AFOP is characterized by formation of “fibrin balls” within the alveolar spaces, with organization resulting from fibroblast migration and secretion of young collagen within fibrin aggregates (Fig 1C).6,9,12 That DAD can have regions with AFOP features is well established. Therefore, the presence of hyaline membranes signifies a diagnosis of DAD, even if AFOP features are also present.6,9,12 OP can be seen in isolation or in combination with DAD or AFOP and is characterized by intraluminal tufts of plump fibroblasts and young/immature collagen tissue within alveolar ducts and distal airspaces (Fig 1D).6,9,12

DAD is considered to be the traditional histopathologic correlate of ARDS.6,7 However, in a large study of 356 patients conducted by Thille et al,13 fewer than half of patients with clinical ARDS, as defined by the Berlin criteria, had DAD on autopsy histopathology.13 A published systematic review by Polak and colleagues14 described histologic patterns consistent with ARDS in lung tissue samples of patients with COVID-19, but whether the patterns of lung injury are unique to COVID-19 as compared with other viral causes of ARDS remains unknown.14 To address this gap in knowledge, we conducted a systematic review of the published literature on COVID-19 lung histopathology from a total of 171 described patients. To provide context for the histopathologic findings in COVID-19 as compared with other recent viral pandemics, we conducted additional systematic reviews of the published literature of lung histopathology reported in 287 patients infected with the 2009 influenza (H1N1) virus and 64 patients infected with SARS-CoV associated with the 2003 SARS outbreak.

Methods

Search Strategy and Study Selection

We conducted several literature natural language searches on MEDLINE, MedRxiv, arXiv, and PubMed, using multiple logical search terms as appropriate and in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis) guidelines.15 We identified studies of COVID-19 lung histopathology through MEDLINE database searches for “(COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2) AND (Pathology OR Autopsy OR Biopsy).” Inclusion criteria for the COVID-19 systematic review included (1) confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 infection by real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay; (2) clinical suspicion of COVID-19 as the primary cause of death; and (3) sufficient histologic description of each reported case within the study. Preprint studies were not included in our analysis because of the lack of adequate peer review at the time of publication.

We identified studies of 2009 H1N1 influenza lung histopathology through a PubMed search for “H1N1 AND (Pathology OR Autopsy OR Biopsy).” Inclusion criteria for the H1N1 influenza systematic review included (1) confirmation of H1N1 influenza infection by RT-PCR; (2) clinical suspicion of H1N1 infection as the primary cause of death, and (3) sufficient histologic description of each reported case within the study.

We identified studies of 2003 SARS lung histopathology through a PubMed search for “SARS AND (Pathology OR Autopsy OR Biopsy).” Inclusion criteria for the SARS systematic review included: (1) fulfillment of the World Health Organization clinical criteria for SARS, including radiologic evidence of infiltrates consistent with pneumonia, fever > 38°C, and a history of chills, cough, malaise, or known exposure; (2) clinical suspicion of SARS-CoV infection as the primary cause of death; and (3) sufficient histologic description of each reported case.

Data Analysis

Data were extracted by two pathologists (L. H., A. S.) into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (2016 Version 15.28). Studies were separated into the following disease categories: COVID-19, 2009 H1N1 influenza, and SARS. The presence of key histologic features were identified and summarized in all studies, including DAD, AFOP, organizing fibrosis, end-stage fibrosis, superimposed neutrophilic pneumonia, microthrombi, and pulmonary thrombi. Categorical variables were expressed numerically (%).

Results

Summary of Cases

COVID-19

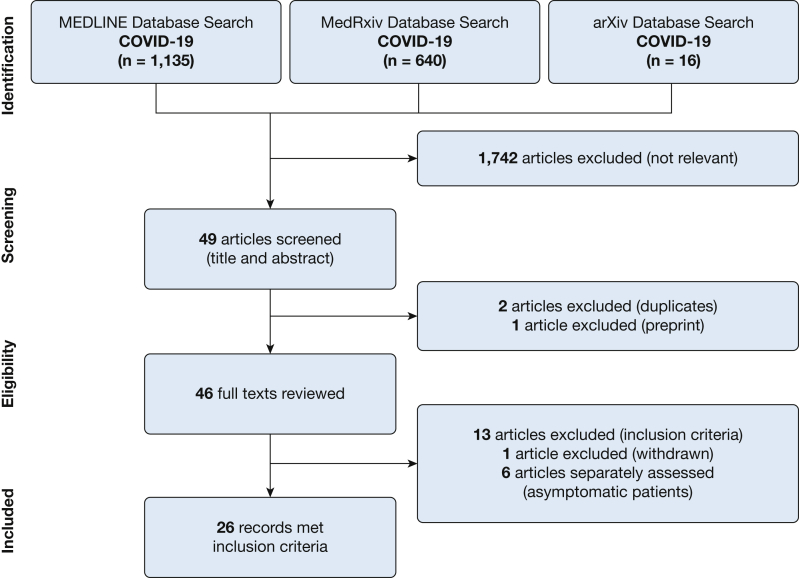

Using our search strategy, we identified 1,791 potentially relevant COVID-19 studies. Of these, 1,742 studies were excluded as not relevant (animal studies or studies without histopathology). Because of the global nature of the early literature, we included foreign language and non-pulmonary-specific studies for further review. We screened 49 studies by title and abstract, excluding an additional two studies as duplicates and one study as a preprint, and completed an in-depth review of the remaining 46 full-length articles (using online language translators for non-English articles as appropriate). A total of 26 articles representing 171 patients met the inclusion criteria and were included in this systematic review (Fig 2).1,16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of systematic literature review for COVID-19.

Of the 26 studies included in the systematic review, 16 were case series,16,20, 21, 22,24,26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33,35, 36, 37 and 10 were single case reports.1,17, 18, 19,23,25,34,38, 39, 40 Of the 171 patients reviewed, most consisted of full or limited (lung only) autopsies (82%, n = 138),16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21,23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30,32, 33, 34,36 with a minority of biopsy-based post-mortem autopsies (18%, n = 33).1,22,31,35,37, 38, 39, 40 The studies evaluated cases from nine countries, including the United States of America (n = 37 patients), Italy (n = 39), Germany (n = 22), Switzerland (n = 22), China (n = 17), Austria (n = 11), Brazil (n = 9), France (n = 6), and Japan (n = 1), with one study describing a combined case series of patients from Germany and the USA (n = 7). The histopathologic findings from these 171 patients with COVID-19 are summarized in Table 1. We also identified six COVID-19 studies that described incidental histopathologic changes in 14 asymptomatic patients who incidentally underwent resection of a lung nodule. Because infection with COVID-19 before biopsy could not be verified for most cases, these cases did not meet our criteria for inclusion and are described separately.41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46

Table 1.

Systematic Review of Lung Histopathology Features in COVID-19 Studies

| Study | Location | No. of Patients | Method | DAD | AFOP | Organizing Fibrosis | End-stage Fibrosis | Superimposed PNA | Microthrombi | Pulmonary Thrombosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ackermann et al16 | Germany/ Boston, MA, USA | 7 | Autopsy | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 4 |

| Adachi et al17 | Japan | 1 | Autopsy | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Antinori et al18 | Italy | 1 | Autopsy | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Barton et al19a | Oklahoma, USA | 1 | Autopsy | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Buja et al20 | USA | 3 | Autopsy | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Carsana et al21 | Milan, Italy | 38 | Autopsy | 38 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 5 | 33 | 0 |

| Copin et al22 | Lille, France | 6 | Post-mortem biopsies | 0 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Craver et al23 | USA | 1 | Autopsy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fox et al24 | New Orleans, Louisiana, USA | 10 | Autopsy | 10 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 |

| Konopka et al25 | Michigan, USA | 1 | Autopsy | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Konopka et al26 | Michigan, USA | 8 | Autopsy | 8 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 7 | 0 |

| Lax et al27 | Graz, Austria | 11 | Autopsy | 11 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 6 | 11 | 11 |

| Magro et al28 | New York City, New York, USA | 2 | Limited autopsy | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Martines et al29 | USA | 8 | Autopsy | 7 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| Menter et al30 | Basel and Liestal, Switzerland | 21 | Autopsy (17). Limited Autopsy (4) | 16 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 10 | 5 | 4 |

| Nunes Duarte-Neto et al31b | São Paulo, Brazil | 9 | Post-mortem biopsy | 9 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 5 | 7 | 0 |

| Schaller et al32 | Ausgberg, Germany | 10 | Autopsy | 10 | 0 | 10 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Sekulic et al33 | Cleveland, OH, USA | 2 | Autopsy | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Suess and Hausmann34 | Gallen, Switzerland | 1 | Autopsy | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Tian et al35 | Wuhan, China | 4 | Post-mortem biopsies | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Wichmann et al36 | Hamburg, Germany | 12 | Autopsy | 8 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 4 |

| Wu et al37 | China | 10 | Post-mortem biopsies | 9 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 8 | 1 | 0 |

| Xu et al1 | Beijing, China | 1 | Post-mortem biopsies | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Yan et al38 | San Antonio, TX, USA | 1 | Post-mortem biopsy | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Yao et al39 | Chongqing, China | 1 | Post-mortem biopsy | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Zhang et al40 | Wuhan, China | 1 | Post-mortem biopsies | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total No. of patients | 171 | 151 | 6 | 89 | 1 | 55 | 97 | 25 | ||

| Proportion of patients | 88% | 4% | 52% | 1% | 32% | 57% | 15% |

All reported numbers are the number of patients reported to have the respective finding within each respective study. AFOP = acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia; DAD = diffuse alveolar damage; PNA = pneumonia.

Also described findings consistent with aspiration pneumonia in a patient with positive severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) nasopharyngeal swab but with no evidence of SARS-CoV-2 pulmonary infection. Only the patient with positive SARS-CoV-2 nasopharyngeal swab and clinical evidence of SARS-CoV-2 pulmonary infection was included in the analysis.

One patient was excluded from the study with 10 patients because of negative RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2. Only results from the nine patients with positive reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction for SARS-CoV-2 were included in the analysis.

H1N1 Influenza

Starting in the spring of 2009, a novel influenza (H1N1) virus caused a global pandemic, with 201,200 respiratory deaths within 1 year.47 Using the search strategy delineated in the Methods section, we identified 2,091 potentially relevant studies. Of these, we excluded 1,248 studies as not relevant (animal studies or studies without histopathology). We screened all remaining studies by title and abstract and identified 32 studies as available and appropriate for in-depth review of full-length articles (using online language translators for non-English articles as appropriate). We identified 20 articles representing 287 patients that met inclusion criteria and were included in this systematic review (e-Fig 1).16,48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66

Of the 20 studies included in the systematic review, 18 were case series,16,48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62,64,65 and two were single case reports.63,66 Of the 287 patients reviewed, most (81%, n = 233) of the cases consisted of full or pulmonary-limited autopsy evaluations,16,48,50, 51, 52, 53,55, 56, 57, 58, 59,61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66 with the minority (19%, n = 54) resenting pre- or post-mortem biopsies.49,54,56,60 The reports represent 12 countries and institutions, including patients reported to the United States Centers for Disease Control (n = 100) and National Institute of Virology in India (n = 44), and patients from the United States (n = 52), Brazil (n = 41), Japan (n = 25), China (n = 6), Mexico (n = 5), and Germany (n = 1), with one study describing a combined case series from Germany and the United States (n = 7) and another study describing a combined case series from Uruguay, Chile, Argentina, and Spain (n = 6). The histopathologic findings from the 287 patients with 2009 H1N1 influenza are summarized in e-Table 1.

SARS

In 2003, SARS—a viral respiratory illness caused by the novel SARS-CoV coronavirus—spread across two dozen countries. Over 1 year, a total of 8,422 cases of infection were reported, with 916 deaths.67 Using our search strategy delineated in Methods, we identified 1,612 potentially relevant studies. Of these, we excluded 779 studies as not relevant (animal studies or studies without histopathology). We screened all remaining studies by title and abstract and identified 18 studies as available and appropriate for in-depth review of full-length articles (using online language translators for non-English articles as appropriate). Of these 18 studies, we identified eight studies representing 64 patients that met inclusion criteria and were included in this systematic review (e-Fig 2).68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75

All eight studies included in the systematic review were case series. Most (89%; n = 57) of the cases were full or pulmonary-limited autopsies,68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75 whereas the minority represented para-mortem biopsies (9%; n = 6)68 and one pre-mortem surgical lung biopsy (2%; n = 1).68 Although all patients fulfilled the World Health Organization clinical criteria for diagnosis of SARS, the presence of SARS-CoV was additionally confirmed by RT-PCR in 47 (73%) cases.68,71,74,75 The reports represent four countries and territories, including patients from Hong Kong (n = 23), China (n = 13), Singapore (n = 8), and Canada (n = 20). The histopathologic findings from the 64 patients with SARS are summarized in e-Table 2.

Reported Histopathology Findings in COVID-19, 2009 H1N1 Influenza, and SARS

DAD, Acute Phase

Of the published autopsy cases of patients with COVID-19, the acute phase of DAD was the predominant pulmonary pathology, reported in 88% of cases (n = 151; Table 1).1,16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21,24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40 The described features included prominent hyaline membranes with edema (e-Fig 3), mild interstitial inflammatory infiltrates, and desquamated pneumocytes with reactive pneumocyte hyperplasia. The acute phase of DAD was the most common histopathologic finding in both H1N1 and SARS, reported in 90% of H1N1 cases (n = 258, e-Table 1)16,48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62,64, 65, 66 and 98% of SARS cases (n = 63, e-Table 2).68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75

AFOP

Amongst the COVID-19 cases, six patients (4%) in one paper were described as having AFOP without hyaline membranes on needle biopsy.22 This study performed biopsy-based samples described in a brief research letter with no further characterization of the patients or their illness and, therefore, possibly hyaline membranes were not observed because of limitations of the sampling method. Five additional studies, including 12 patients, describe COVID-19 autopsy cases with regions of AFOP in a background of hyaline membranes, which were ultimately categorized in the reports as DAD.25,26,28,35,40 AFOP was also a rare finding in H1N1, with only one case (0.3%) identified as pure AFOP.63 In SARS, no patients were identified as having pure AFOP. In one case series, AFOP was identified as the predominant pattern in six (9%) cases that were diagnosed in the report as AFOP.72 However, these cases were described to have a background of hyaline membranes, and therefore, DAD may have been a more appropriate diagnosis.

Organizing Fibrosis

Most of the published COVID-19 autopsy case series describe the acute phase of DAD as the prominent acute lung injury pattern.1,16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21,24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40 However, features of organizing fibrosis were reported on histopathologic examination in 52% of the COVID-19 autopsy cases (n = 89).17,18,21,22,24,26,27,29, 30, 31, 32, 33,35, 36, 37,40 In most cases, organizing fibrosis was described as either focal or in the setting of mixed acute and organizing phases of DAD (e-Figs 3, 4), indicating an early transition to the subacute organizing phase of DAD. Organizing fibrosis was reported in 40% of H1N1 cases (n = 115)16,48, 49, 50, 51, 52,54, 55, 56, 57,59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64 and 47% of SARS cases (n = 30).68, 69, 70, 71, 72,74,75

End-stage Fibrosis

Progression to late fibrosis was rare in all cases of viral ARDS reviewed here and only occurred in patients with prolonged illness. Among the COVID-19 autopsy cases, end-stage fibrosis was noted in a single patient (1%) with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia who died 26 days after symptom onset.32 Similarly, eight (3%) of the H1N1 cases had end-stage fibrosis, all in patients more than 4 weeks from symptom onset.54,62 Among the SARS cases, there was a relatively higher proportion of end-stage fibrotic changes, present in 6% of cases (n = 4).68,75 Three of these patients were more than 4 weeks from symptom onset,68 and one was 19 days from symptom onset but was mechanically ventilated for over 2 weeks at the time of death.75

Microthrombotic Disease

Of the COVID-19 cases, 57% (n = 97) were reported to have microthrombotic disease in capillaries and small and medium-sized vessels (e-Fig 4).16,19, 20, 21,24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31,34,36,37,39 In H1N1, microthrombi were described in 24% (n = 70) of cases.16,48,50, 51, 52,55,57,59,60,62,64,65 Similar to COVID-19, among the SARS cases, microthrombi were reported in 58% (n = 37) of cases.68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75

Pulmonary Thrombosis

Thrombosis in large pulmonary vessels was reported in 15% of COVID-19 autopsy cases (n = 25).16,20,27,30,34,36 In the H1N1 cases, 6% (n = 18) had medium or large vessel thrombosis.16,50,51,58,60 The reported rate of thrombosis was higher in SARS, with 28% (n = 18) of cases describing thrombi in medium or large vessels.69, 70, 71, 72,75

Acute Neutrophilic Pneumonia

Secondary bacterial infections have been reported in patients with COVID-19 with varying incidence (e-Fig 5).76,77 In this systematic review, 32% (n = 55) reported histologic features suggestive of acute pneumonia in COVID-19 patients.18,21,26,27,29, 30, 31, 32, 33,35, 36, 37 Similar rates of superimposed pneumonia were reported in H1N1 cases (30%, n = 86)48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53,55,57, 58, 59,61,64,65 and SARS cases (31%, n = 20).68,69,71,72,74,75 Clinical data identifying pneumonia origin was not consistently available across all case reports in an unbiased manner and is therefore not reported here.

SARS-CoV-2 Virus in Postmortem Lung Tissue

Of the 26 published papers on autopsy cases of patients with COVID-19, 19 performed additional testing to detect SARS-CoV-2 in post-mortem lung tissue, including electron microscopy (EM), RT-PCR (on lung tissue or bronchial swab samples), or immunohistochemistry for SARS-CoV protein in some or all of the patients in their reports.1,16,17,19,21,24,27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33,35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40 EM was performed on 31 patients in eight studies.16,21,24,29,30,37, 38, 39 Of those, two cases in one study were not sufficient for analysis because of autolysis.30 Viral particles were found by EM in 18 of the remaining 29 patients (62%).16,21,24,29,37, 38, 39 RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 was conducted on 80 cases (69 lung tissue samples and 11 bronchial swabs) in 12 studies, 75 of which were positive (94%).1,17,19,27,30, 31, 32, 33,35, 36, 37,39 The expression of SARS-CoV protein by immunohistochemistry was evaluated in 11 patients in four studies, and 10 cases exhibited positive staining (91%) (e-Fig 3D).17,28,29,40

Examples of COVID-19-related lung injury are presented in e-Appendix 1 (e-Figs 3-5) from the first five autopsy cases performed in series at Massachusetts General Hospital from March 30th through April 10th, 2020.

Histopathological Abnormalities in Patients With Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection

Six published reports describe incidental histopathologic findings in a total of 14 asymptomatic patients who underwent lung nodule resections and were subsequently found to have SARS-CoV-2 infection.41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46 Unsurprisingly, the histologic findings were less severe than those in cases of patients with symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Most cases showed focal edema with proteinaceous exudate, pneumocyte hyperplasia, patchy chronic inflammation, and multinucleated pneuomocytes.42,43,45,46 One case series of two patients also described scant intra-alveolar fibrin with little to no hyaline membranes.43 One report described seven asymptomatic COVID-19 patients, in which one patient demonstrated mixed interstitial inflammation without pneumocyte hyperplasia, fibrin deposition, or obvious viral inclusions, and the other six patients had no identifiable histologic abnormalities.46 All seven patients had fever postoperatively (onset, 0-23 days from surgery; mean, 8.6 days from surgery), and five patients had respiratory symptoms. Confirmation of COVID-19 was determined on the basis of positive results from oropharyngeal swabs tested for SARS-CoV-2 by postoperative RT-PCR assay. Given the variable timing of disease symptom onset after surgery, possibly the patients did not yet have SARS-CoV-2 infection at the time of surgery, or the disease had not yet involved the lungs at the time of resection. Additionally, the overall histologic findings are nonspecific and may even represent changes that can be seen adjacent to mass lesions. As such, the histologic changes of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection remain unclear.

Other Non-COVID-19-Related Lung Diseases in Patients With SARS-CoV-2 Infection

Distinct, non-COVID-19-related histopathologic findings may exist in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. For example, one case report described a 42-year-old man with muscular dystrophy who presented to the hospital with 2 days of abdominal pain, a SARS-CoV-2-positive nasopharyngeal swab, and unfortunately died of respiratory failure within hours of hospital admission.19 On complete autopsy, the lung demonstrated multifocal acute bronchopneumonia with clear evidence of aspirated food material. Repeat SARS-CoV-2 testing on the lung tissue was negative. It was determined that the patient likely died with, not of, SARS-CoV-2 infection. Although COVID-19 has changed a lot about the practice of medicine, some principles endure, and aspiration will always be in the differential diagnosis.

Reported Clinical Findings

Clinical details, such as age, sex, comorbidities, mechanical ventilation, therapeutic interventions, and disease time course, were variably reported amongst the papers included in this systematic review, which prohibited the calculation and comparison of summary statistics for these clinical details. The clinical data that were presented by each paper included in this systematic review in COVID-19, 2009 H1N1 influenza, and SARS cohorts is presented in e-Table 3.

Discussion

As the COVID-19 pandemic has unfolded, some have suggested that COVID-19 is characterized by novel acute lung injury patterns22 and have used this assertion to propose subclassification of COVID-19 ARDS into novel phenotypes.3,4 This systematic review of the literature demonstrates that the predominant histologic pattern among patients with COVID-19-associated lung injury is acute-phase DAD (88%) with prominent hyaline membranes and evidence of transition to the organizing phase of DAD in 52% of cases. We further demonstrate that this is similar to the rates of acute DAD observed in H1N1 influenza (90%) and SARS (98%) viral ARDS (Table 2) and is higher than the rate of DAD reported in a large-scale study of ARDS (45%) conducted by Thille et al.13

Table 2.

Comparison of Reported Lung Histopathology Features in COVID-19, 2009 H1N1 Influenza A, and SARS

| Virus | No. of Patients | DAD | AFOP | Organizing Fibrosis | End-stage Fibrosis | Superimposed PNA | Microthrombi | Pulmonary Thrombosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 | 171 | 88% (151) | 4% (6) | 52% (89) | 1% (1) | 32% (55) | 57% (97) | 15% (25) |

| 2009 H1N1 Influenza A | 287 | 90% (258) | 0.3% (1) | 40% (115) | 3% (8) | 30% (86) | 24% (70) | 6% (18) |

| SARS | 64 | 98% (63) | 9% (6) | 47% (30) | 6% (4) | 31% (20) | 58% (37) | 28% (18) |

All reported numbers are the proportion and number of patients (in parentheses) reported to have the respective finding within each viral cohort. AFOP = acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; DAD = diffuse alveolar damage; PNA = pneumonia; Pulmonary thrombosis: pulmonary vessel thrombosis; SARS = severe acute respiratory syndrome.

Some reports have identified microthrombi as a prominent feature of lung injury in patients with COVID-19,16,21,28 causing speculation that SARS-CoV-2 has a predilection for endothelial cells, which may increase the incidence of microthrombotic complications and contribute to hypoxemia. Vascular thrombosis and microthrombosis are frequent findings in DAD, resulting from local inflammation even in the absence of a systemic hypercoagulable state.6,7,9,10,16 Angiographic studies have confirmed that thrombosis occurs early in ARDS of diverse causes.11 In addition, a heightened index of suspicion for acute embolism may improve outcomes in pediatric ARDS.11 In this systematic review, pulmonary microthrombi were reported in approximately half of COVID-19 patients (57%), which is similar to that reported in patients with SARS (58%; Table 2). This is higher than the incidence of microthrombi reported in patients with H1N1 influenza (24% of patients), which closely parallels the 24% incidence of microthrombi described in a large-scale histopathologic autopsy study of DAD.78 This is an interesting finding that may suggest that coronaviruses in general could be associated with increased pulmonary microthrombi. However, the biases inherent in published case reports require further prospective investigational studies to validate these histopathologic findings. If validated, further work is needed to elucidate the pathophysiologic mechanisms driving microthrombotic formation in coronavirus infections and ascertain their clinical relevance as compared with other viral and nonviral causes of lung injury.

The main strength of this study is that it provides a comprehensive systematic review of reported COVID-19-associated lung pathology with comparison to the reported lung pathologic conditions associated with other recent viral pandemics, namely, the 2009 H1N1 influenza and SARS. Nevertheless, there are several limitations. First, some of the reported case series are biopsy-based (11% of SARS, 18% of COVID-19, and 19% of H1N1 reports) rather than full autopsies, which may introduce systematic biases based on suboptimal tissue evaluation. Second, cases that were sent for biopsy or autopsy by the clinician may have been systematically different from cases that did not have tissue sampling—for example, more severe disease stage—which could introduce additional biases by not representing the full spectrum of COVID-19-associated lung pathology. Thus, this is not a random sampling. However, we believe the reported case series is the most comprehensive description of COVID-19-associated lung pathology and thus provides important insights for clinicians and researchers. This bias applies equally to all three viral pneumonias, not solely COVID-19. Third, although RT-PCR confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 and H1N1 influenza was uniformly present, not all SARS comparison cases were confirmed by RT-PCR for SARS-CoV. Although possibly some SARS cases diagnosed solely by clinical criteria were misclassified, this is unlikely to influence the overall conclusions of this systematic review. The number of SARS case reports is also fewer than the COVID-19 or H1N1 influenza case reports, which could bias the comparison. However, the systematic review of COVID-19 and SARS, both of which are coronavirus infections, arrived at similar results.

Another important limitation is that detailed clinical characteristics were not reported in all case series, including but not limited to comorbid conditions, duration of illness, timing of biopsy, and mechanical ventilation strategies, all of which could influence lung pathology. Physicians treating patients with COVID-19 have also been using a range of experimental therapies, such as immunomodulatory agents, based on a variety of indications. Because the use of these medications has not been consistently reported in the published literature, these data are not available to characterize the extent to which these therapies influence histologic findings. Additionally, there is not yet comparison between the pathologic conditions described in these case series and histopathologic details from (1) patients who recover from severe ALI; (2) patients with milder respiratory disease and radiologic abnormalities who do not require intubation; and (3) patients with no symptomatic disease but with radiologic abnormalities. Thus, possibly COVID-19 patients have a spectrum of ALI patterns, but the proportions and extent of disease in these patients remain a histologic mystery. Moreover, patients who recover from DAD are at risk of developing progressive architectural remodeling and interstitial fibrosis,6 but data on the long-term effects of COVID-19-associated lung injury are not currently available. As this pandemic continues, it is crucial for forthcoming pathology reports to describe detailed clinical information, including demographics, medical comorbidities, concomitant therapies, and use of invasive and noninvasive mechanical ventilation to further place these important histopathologic reports into the appropriate clinical context.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to affect millions of people worldwide, many of whom will require hospitalization because of respiratory symptoms, it is crucial to characterize the acute and chronic impacts COVID-19 have on lung health. Biopsy and autopsy histopathology remain essential tools in understanding COVID-19 and answering questions that remain regarding the spectrum of COVID-19-associated lung disease. The available evidence suggests that COVID-19 falls along the spectrum of known histopathology in the setting of ARDS, primarily manifesting as acute-phase DAD. Microvascular thrombotic complications are reported to be more prevalent in COVID-19 and SARS (present in half of patients) than in H1N1 influenza or other causes of ARDS (present in a quarter of patients). Future studies will be crucial to characterize the scope of lung pathology across the spectrum of COVID-19 severity and to assess how interventions designed to prevent the development of respiratory failure, the final common pathway in COVD-19-associated mortality, influence clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: L. P. H., C. M. N., A. R. S., R. A. I., J. H. M., J. A. V., C. C. H., and M. R. M. conceived, designed, and executed the literature search. L. P. H., C. M. N., A. R. S., R. A. I., J. N. M., J. A. V., V. V., J. R., D. A. O., A. S., J. W. A., J. W. G., M. A. G., Y. R., C. J. R., A. K. W., A. L., Y. P. H., R. R. C., C. R. P., T. F. C., L. N. B., K. A. H., B. D. M., C. C. H., J. R. S., and M. R. M. had access to and analyzed and interpreted the data. All authors participated in the care of the patients presented in the Supplemental Materials. L. P. H., C. M. N., A. R. S., R. A. I., J. N. M., J. A. V., V. V., J. R., D. A. O., A. S., J. W. A., J. W. G., M. A. G., Y. R., C. J. R., A. K. W., A. L., Y. P. H., R. R. C., C. R. P., T. F. C., L. N. B., K. A. H., B. D. M., C. C. H., J. R. S., and M. R. M. participated in the development and critical review of the manuscript, provided final approval for publication submission and are accountable for the accuracy and integrity of the work. L. P. H. and M. R. M. had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST the following: L. P. H. has served as a consultant for Biogen Idec, and serves as a consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim and Pliant Therapeutics. She also receives grant funding from Boehringer Ingelheim. B. D. M. has served on Advisory Boards for Sanofi and Regeneron and serves on the steering committee for a Joint Pulmonary Drug Discovery Laboratory sponsored by Bayer. M. M.-K. has served as a compensated consultant for H3 Biomedicine and AstraZeneca; has received research (institutional) funding from Novartis. L. N. B. has received research funding from Apple. None declared (C. M. N., A. R. S., R. A. I., J. H. M., J. A. V., V. V., J. R., D. A. O., A. S., J. W. A., J. W. G., M. A. G., Y. R., C. J. R., A. K. W., A. L., Y. P. H., R. R. C., C. R. P., T. F. C., K. A. H., C. C. H., J. R. S.).

Role of sponsors: The sponsor had no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of the data, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Additional information: The e-Appendix, e-Figures, and e-Tables can be found in the Supplemental Materials section of the online article.

Footnotes

Drs Hariri and North contributed equally to this manuscript. Drs Stone and Mino-Kenudson also contributed equally to this manuscript.

FUNDING/SUPPORT: L. P. H. is supported by NIH K23HL132120 and R01HL152075. R. R. C. is supported by NIH T32HL116275 and the American Thoracic Society Foundation.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Xu Z., Shi L., Wang Y. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(4):420–422. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu F., Zhao S., Yu B. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579(7798):265–269. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gattinoni L., Chiumello D., Caironi P. COVID-19 pneumonia: different respiratory treatments for different phenotypes? Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(6):1099–1102. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06033-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gattinoni L., Coppola S., Cressoni M., Busana M., Rossi S., Chiumello D. Covid-19 does not lead to a "typical" acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(10):1299–1300. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0817LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ziehr D.R., Alladina J., Petri C.R. Respiratory pathophysiology of mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19: a cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(12):1560–1564. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202004-1163LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beasley M.B. The pathologist's approach to acute lung injury. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134(5):719–727. doi: 10.5858/134.5.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katzenstein A.L., Bloor C.M., Leibow A.A. Diffuse alveolar damage: the role of oxygen, shock, and related factors. A review. Am J Pathol. 1976;85(1):209–228. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marshall R.P., Bellingan G., Webb S. Fibroproliferation occurs early in the acute respiratory distress syndrome and impacts on outcome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(5):1783–1788. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.5.2001061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leslie K.O. My approach to interstitial lung disease using clinical, radiological and histopathological patterns. J Clin Pathol. 2009;62(5):387–401. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2008.059782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hariri L., Hardin C.C. Covid-19, angiogenesis, and ARDS endotypes. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(2):182–183. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe2018629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greene R., Lind S., Jantsch H. Pulmonary vascular obstruction in severe ARDS: angiographic alterations after i.v. fibrinolytic therapy. Am J Roentgenol. 1987;148(3):501–508. doi: 10.2214/ajr.148.3.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beasley M.B., Franks T.J., Galvin J.R., Gochuico B., Travis W.D. Acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia: a histological pattern of lung injury and possible variant of diffuse alveolar damage. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2002;126(9):1064–1070. doi: 10.5858/2002-126-1064-AFAOP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thille A.W., Esteban A., Fernandez-Segoviano P. Comparison of the Berlin definition for acute respiratory distress syndrome with autopsy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(7):761–767. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201211-1981OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Polak S.B., Van Gool I.C., Cohen D., von der Thusen J.H., van Paassen J. A systematic review of pathological findings in COVID-19: a pathophysiological timeline and possible mechanisms of disease progression. Mod Pathol. 2020;33(11):2128–2138. doi: 10.1038/s41379-020-0603-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D., Shamseer L., Clarke M. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ackermann M., Verleden S.E., Kuehnel M. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(2):120–128. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2015432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adachi T., Chong J.M., Nakajima N. Clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical findings from autopsy of patient with COVID-19, Japan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(9):2157–2161. doi: 10.3201/eid2609.201353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Antinori S., Rech R., Galimberti L. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis complicating SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia: a diagnostic challenge. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101752. [Published online ahead of print May 26, 2020] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barton L.M., Duval E.J., Stroberg E., Ghosh S., Mukhopadhyay S. COVID-19 autopsies, Oklahoma, USA. Am J Clin Pathol. 2020;153(6):725–733. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqaa062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buja L.M., Wolf D.A., Zhao B. The emerging spectrum of cardiopulmonary pathology of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): report of 3 autopsies from Houston, Texas, and review of autopsy findings from other United States cities. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2020;48:107233. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2020.107233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carsana L., Sonzogni A., Nasr A. Pulmonary post-mortem findings in a series of COVID-19 cases from northern Italy: a two-centre descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(10):1135–1140. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30434-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Copin M.-C., Parmentier E., Duburcq T., Poissy J., Mathieu D. Time to consider histologic pattern of lung injury to treat critically ill patients with COVID-19 infection. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(6):1124–1126. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06057-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Craver R., Huber S., Sandomirsky M., McKenna D., Schieffelin J., Finger L. Fatal eosinophilic myocarditis in a healthy 17-year-old male with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2c) Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 2020;39(3):263–268. doi: 10.1080/15513815.2020.1761491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fox S.E., Akmatbekov A., Harbert J.L., Li G., Quincy Brown J., Vander Heide R.S. Pulmonary and cardiac pathology in African American patients with COVID-19: an autopsy series from New Orleans. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(7):681–686. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30243-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Konopka K.E., Wilson A., Myers J.L. Postmortem lung findings in an asthmatic patient with coronavirus disease 2019. Chest. 2020;158(3):e99–e101. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Konopka K.E., Nguyen T., Jentzen J.M. Diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) from coronavirus disease 2019 infection is morphologically indistinguishable from other causes of DAD. Histopathology. 2020 doi: 10.1111/his.14180. [Published online ahead of print June 15, 2020] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lax S.F., Skok K., Zechner P. Pulmonary arterial thrombosis in COVID-19 with fatal outcome: results from a prospective, single-center, clinicopathologic case series. Ann Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.7326/M20-2566. [Published online ahead of print May 14, 2020] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magro C., Mulvey J.J., Berlin D. Complement associated microvascular injury and thrombosis in the pathogenesis of severe COVID-19 infection: a report of five cases. Transl Res. 2020;220:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2020.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martines R.B., Ritter J.M., Matkovic E. Pathology and pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 associated with fatal coronavirus disease, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(9):2005–2015. doi: 10.3201/eid2609.202095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Menter T., Haslbauer J.D., Nienhold R. Post-mortem examination of COVID19 patients reveals diffuse alveolar damage with severe capillary congestion and variegated findings of lungs and other organs suggesting vascular dysfunction. Histopathology. 2020;77(2):198–209. doi: 10.1111/his.14134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nunes Duarte-Neto A., de Almeida Monteiro R.A., da Silva L.F.F. Pulmonary and systemic involvement of COVID-19 assessed by ultrasound-guided minimally invasive autopsy. Histopathology. 2020 doi: 10.1111/his.14160. [Published online ahead of print May 22, 2020] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schaller T., Hirschbuhl K., Burkhardt K. Postmortem examination of patients with COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323(24):2518–2520. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sekulic M., Harper H., Nezami B.G. Molecular detection of SARS-CoV-2 infection in FFPE samples and histopathologic findings in fatal SARS-CoV-2 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2020;154(2):190–200. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqaa091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suess C., Hausmann R. Gross and histopathological pulmonary findings in a COVID-19 associated death during self-isolation. Int J Legal Med. 2020;134(4):1285–1290. doi: 10.1007/s00414-020-02319-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tian S., Xiong Y., Liu H. Pathological study of the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) through postmortem core biopsies. Mod Pathol. 2020;33(6):1007–1014. doi: 10.1038/s41379-020-0536-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wichmann D., Sperhake J.P., Lutgehetmann M. Autopsy findings and venous thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(4):268–277. doi: 10.7326/M20-2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu J.H., Li X., Huang B. [Pathological changes of fatal coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the lungs: report of 10 cases by postmortem needle autopsy] Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2020;49(6):568–575. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112151-20200405-00291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yan L., Mir M., Sanchez P. Autopsy report with clinical pathological correlation. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2020;144(9):1041–1047. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2020-0217-SA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yao X.H., He Z.C., Li T.Y. Pathological evidence for residual SARS-CoV-2 in pulmonary tissues of a ready-for-discharge patient. Cell Res. 2020;30(6):541–543. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0318-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang H., Zhou P., Wei Y. Histopathologic changes and SARS-CoV-2 immunostaining in the lung of a patient with COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(9):629–632. doi: 10.7326/M20-0533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuang D., Xu S.P., Hu Y., Liu C., Duan Y.Q., Wang G.P. [Pathological changes with novel coronavirus infection in lung cancer surgical specimen] Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2020;49(5):471–473. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112151-20200315-00205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pernazza A., Mancini M., Rullo E. Early histologic findings of pulmonary SARS-CoV-2 infection detected in a surgical specimen. Virchows Arch. 2020;477(5):743–748. doi: 10.1007/s00428-020-02829-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tian S., Hu W., Niu L., Liu H., Xu H., Xiao S.Y. Pulmonary pathology of early-phase 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pneumonia in two patients with lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15(5):700–704. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu S.P., Kuang D., Hu Y., Liu C., Duan Y.Q., Wang G.P. [Detection of 2019-nCoV in the pathological paraffin embedded tissue] Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2020;49(4):354–357. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112151.20200219.00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zeng Z., Xu L., Xie X.Y. Pulmonary pathology of early phase COVID-19 pneumonia in a patient with a benign lung lesion. Histopathology. 2020;77(5):823–831. doi: 10.1111/his.14138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cai Y., Hao Z., Gao Y. COVID-19 in the perioperative period of lung resection: a brief report from a single thoracic surgery department in Wuhan, China. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15(6):1065–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dawood F.S., Iuliano A.D., Reed C. Estimated global mortality associated with the first 12 months of 2009 pandemic influenza A H1N1 virus circulation: a modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(9):687–695. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Calore E.E., Uip D.E., Perez N.M. Pathology of the swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) flu. Pathol Res Pract. 2011;207(2):86–90. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Capelozzi V.L., Parra E.R., Ximenes M., Bammann R.H., Barbas C.S., Duarte M.I. Pathological and ultrastructural analysis of surgical lung biopsies in patients with swine-origin influenza type A/H1N1 and acute respiratory failure. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2010;65(12):1229–1237. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322010001200003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harms P.W., Schmidt L.A., Smith L.B. Autopsy findings in eight patients with fatal H1N1 influenza. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;134(1):27–35. doi: 10.1309/AJCP35KOZSAVNQZW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mauad T., Hajjar L.A., Callegari G.D. Lung pathology in fatal novel human influenza A (H1N1) infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(1):72–79. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200909-1420OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nakajima N., Hata S., Sato Y. The first autopsy case of pandemic influenza (A/H1N1pdm) virus infection in Japan: detection of a high copy number of the virus in type II alveolar epithelial cells by pathological and virological examination. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2010;63(1):67–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rosen D.G., Lopez A.E., Anzalone M.L. Postmortem findings in eight cases of influenza A/H1N1. Mod Pathol. 2010;23(11):1449–1457. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shelke V.N., Kolhapure R.M., Kadam D. Pathologic study of pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 cases from India. Pathol Int. 2012;62(1):36–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2011.02751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shieh W.J., Blau D.M., Denison A.M. 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1): pathology and pathogenesis of 100 fatal cases in the United States. Am J Pathol. 2010;177(1):166–175. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fujita J., Ohtsuki Y., Higa H. Clinicopathological findings of four cases of pure influenza virus A pneumonia. Intern Med. 2014;53(12):1333–1342. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.53.1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gill J.R., Sheng Z.M., Ely S.F. Pulmonary pathologic findings of fatal 2009 pandemic influenza A/H1N1 viral infections. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134(2):235–243. doi: 10.5858/134.2.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hajjar L.A., Mauad T., Galas F. Severe novel influenza A (H1N1) infection in cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(12):2333–2341. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.He Y.X., Gao Z.F., Lu M. [A histopathological study on Influenza A H1N1 infection in humans] Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2010;42(2):137–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marchiori R., Bredt C.S., Campos M.M., Negretti F., Duarte P.A. Pandemic influenza A/H1N1: comparative analysis of microscopic lung histopathological findings. Einstein (Sao Paulo) 2012;10(3):306–311. doi: 10.1590/s1679-45082012000300009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mukhopadhyay S., Philip A.T., Stoppacher R. Pathologic findings in novel influenza A (H1N1) virus ("Swine Flu") infection: contrasting clinical manifestations and lung pathology in two fatal cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;133(3):380–387. doi: 10.1309/AJCPXY17SULQKSWK. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nin N., Sanchez-Rodriguez C., Ver L.S. Lung histopathological findings in fatal pandemic influenza A (H1N1) Med Intensiva. 2012;36(1):24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.medin.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Otto C., Huzly D., Kemna L. Acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia associated with influenza A/H1N1 pneumonia after lung transplantation. BMC Pulm Med. 2013;13:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-13-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ru Y.X., Li Y.C., Zhao Y. Multiple organ invasion by viruses: pathological characteristics in three fatal cases of the 2009 pandemic influenza A/H1N1. Ultrastruct Pathol. 2011;35(4):155–161. doi: 10.3109/01913123.2011.574249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Soto-Abraham M.V., Soriano-Rosas J., Diaz-Quinonez A. Pathological changes associated with the 2009 H1N1 virus. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(20):2001–2003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0907171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Takiyama A., Wang L., Tanino M. Sudden death of a patient with pandemic influenza (A/H1N1pdm) virus infection by acute respiratory distress syndrome. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2010;63(1):72–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chan-Yeung M., Xu R.H. SARS: epidemiology. Respirology. 2003;8(Suppl):S9–S14. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00518.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cheung O.Y., Chan J.W., Ng C.K., Koo C.K. The spectrum of pathological changes in severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) Histopathology. 2004;45(2):119–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2004.01926.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen J., Zhang H.T., Xie Y.Q. [Morphological study of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)] Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2003;32(6):516–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ding Y., Wang H., Shen H. The clinical pathology of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): a report from China. J Pathol. 2003;200(3):282–289. doi: 10.1002/path.1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Franks T.J., Chong P.Y., Chui P. Lung pathology of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): a study of 8 autopsy cases from Singapore. Hum Pathol. 2003;34(8):743–748. doi: 10.1016/S0046-8177(03)00367-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hwang D.M., Chamberlain D.W., Poutanen S.M., Low D.E., Asa S.L., Butany J. Pulmonary pathology of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Toronto. Mod Pathol. 2005;18(1):1–10. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lang Z.W., Zhang L.J., Zhang S.J. A clinicopathological study of three cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) Pathology. 2003;35(6):526–531. doi: 10.1080/00313020310001619118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nicholls J.M., Poon L.L., Lee K.C. Lung pathology of fatal severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361(9371):1773–1778. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13413-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tse G.M., To K.F., Chan P.K. Pulmonary pathological features in coronavirus associated severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) J Clin Pathol. 2004;57(3):260–265. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2003.013276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.He Y., Li W., Wang Z., Chen H., Tian L., Liu D. Nosocomial infection among patients with COVID-19: A retrospective data analysis of 918 cases from a single center in Wuhan, China. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020;41(8):1–2. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Goyal P., Choi J.J., Pinheiro L.C. Clinical characteristics of Covid-19 in New York City. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(24):2372–2374. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2010419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Thille A.W., Esteban A., Fernandez-Segoviano P. Chronology of histological lesions in acute respiratory distress syndrome with diffuse alveolar damage: a prospective cohort study of clinical autopsies. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1(5):395–401. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70053-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.