Short abstract

Watch an interview with the author

Abbreviations

- CDC

US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- eHAV

quasi‐enveloped hepatitis A virus

- GSK

GlaxoSmithKline

- HAV

hepatitis A virus

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- Ig

immune serum globulin

- IgG

immunoglobulin G

- IgM

immunoglobulin M

- MSD

Merck Sharp & Dohme

- MSM

men who have sex with men

- UMV

universal mass immunization

Daniel Shouval

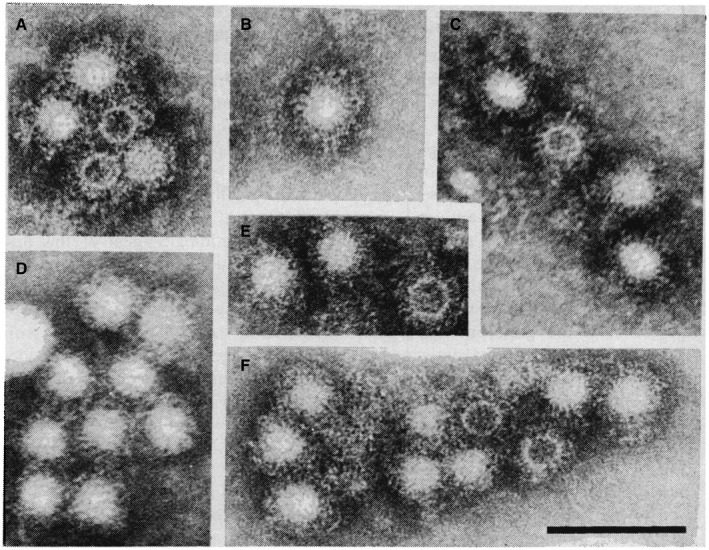

The hepatitis A virus (HAV) (Fig. 1), 1 a positive‐stranded RNA virus within the Hepatovirus species, is an ancient hepatotropic pathogen, belonging to the Picornaviridae family that has been infecting humans for millennia. 2 Bayesian analysis of human‐derived HAV genomes of Hepatovirus A suggests a recent common ancestor of ~1500 years, with a common ancestor for all variants that may have existed already 2000 to 3000 years ago. 3 , 4 HAV is mainly (but not exclusively) transmitted through the fecal‐oral route and causes epidemics, as well as sporadic, anicteric, or icteric hepatitis. 2 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14

Fig 1.

Identification of HAV particles in stools, by Feinstone et al., 1 using immune electron microscopy. Reproduced with permission from Science. 1 Copyright 1973, American Association for the Advancement of Science.

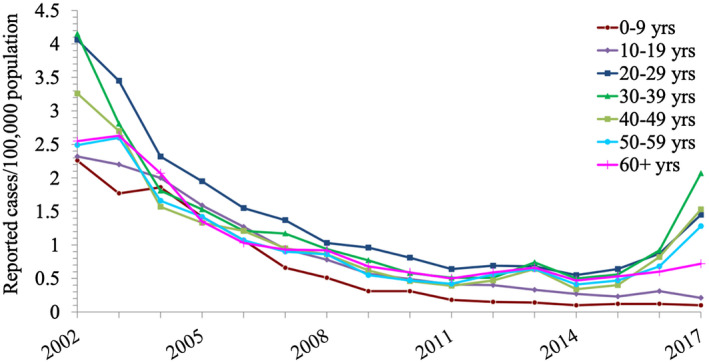

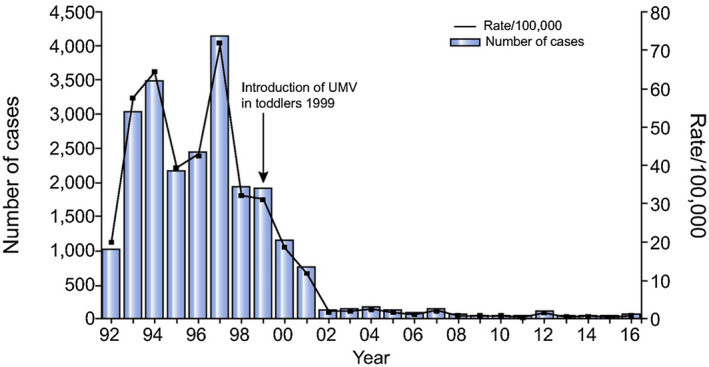

The disease burden of HAV infection in industrial countries has been declining during the past two decades (Fig. 2) because of improved sanitary and socioeconomic conditions, as well as the introduction of several efficacious vaccines in regions where immunization rates are relatively high. 15

Fig 2.

Rates of reported acute HAV infection, by age group, in the US, 2002 to 2017. Reproduced from CDC, National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System. Hepatitis A Tables and Figures. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2017surveillance/tablesFigures-HepA.htm#tabs-1-6. Accessed April 10, 2020. 82

Despite a global trend for a declining incidence of acute HAV infection, HAV still infects millions of people annually worldwide, frequently causing temporary disability but rarely liver failure with significant health care expense. However, improvement in socioeconomic and sanitary conditions in many countries is leading to a decline in infection rates, as well as in herd immunity against HAV. Consequently, susceptibility to HAV infection has increased in large populations beyond childhood, through the import of contaminated food products, 16 following travel to HAV‐endemic countries, 17 in men who have sex with men (MSM), 18 in homeless individuals, 19 , 20 and in patients with HIV. 21 Thus, although HAV rates in the United States have decreased by 95% from 1996 to 2011, a paradoxic increase in HAV infections was noted by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), as manifested by 15,000 reports of new infections in US states and territories between 2016 and 2018. 22

HAV infection often remains anicteric and unrecognized, especially in children, 23 but it may also cause severe hepatitis, jaundice, and rarely, hepatic decompensation. 24

During the last four decades, significant progress has been achieved in understanding the genomic organization, molecular epidemiology, diagnosis, 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 and prevention of HAV infection. 15 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 Formaldehyde‐inactivated hepatitis A vaccines were already licensed in 1991 and 1995 in Europe and the United States, respectively, 31 , 32 whereas a live attenuated HAV vaccine has been available in China since 1992. 34 To date, it can be stated without reservation that similar to hepatitis B, hepatitis A is a vaccine‐preventable disease, as originally assessed following the hepatitis virus transmission studies by the late Saul Krugman. 35

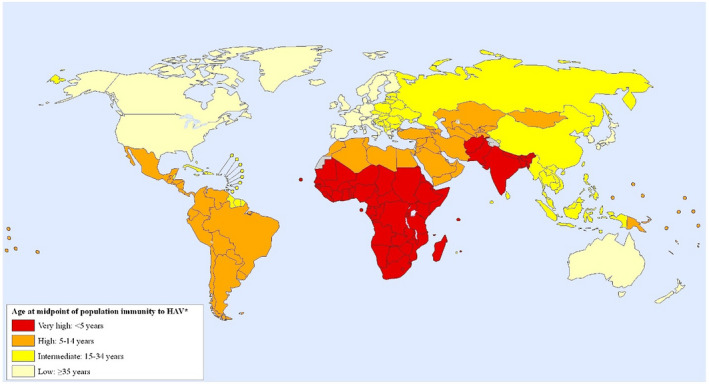

Yet, despite the development of efficient means of prevention, HAV infection is still prevalent in many countries worldwide 36 (Fig. 3) because large‐scale control of infection through vaccination is still restricted to selected geographic regions. 15

Fig 3.

Global map of prevalence of HAV immunity (2005). Reproduced with permission from International Journal of Health Geographics. 36 Copyright 2011, BioMed Central Ltd.

Space limitation prevents me from giving full credit to the hundreds of investigators, virologists, epidemiologists, immunologists, and clinicians who contributed to the impressive progress in this field (see the 1983 review on The History of Viral Hepatitis by Jean and Fritz Deinhardt 2 and a recent collection of monographs, Enteric Hepatitis Viruses, edited by Stanley Lemon and Christopher Walker 13 ). The current essay is intended to provide a concise overview of the history of the long struggle of medical professionals to control HAV infection and jaundice.

The term jaundice is derived by epenthetic insertion (as the linguists would have it) of the sound “d” into the Old French jaunisse (modern jaunise)—to make it easier to pronounce—which itself comes from jaune, meaning “yellow.” Jaundice had already triggered the attention of medical practitioners over 5000 years ago. The alternative yet equivalent expression icterus (ικτερος) is derived from the Greek word for the golden thrush, a bird with golden plumage belonging to the New Word orioles in the genus Icterus of the blackbird family 2 (Fig. 4). According to ancient Jewish and Greek beliefs, placing this bird near the umbilicus of a jaundiced person may lead to resolution of the icterus/jaundice, recovery of the patient, and death of the bird.

Fig 4.

The golden thrush Yellow tail oriole, Icterus nigrogularis. Photo by Félix Uribe, covered under Attribution‐ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY‐SA 2.0).

Epidemic jaundice (icterus epidemicus) and liver disease are mentioned in the Babylonian Talmud and by the authors of the Hippocratic Corpus—both in the fifth century BCE—and in the ancient Chinese literature, ~200s CE. 2 Epidemic jaundice was described by Bamberger in 1855, 37 by Virchow in 1865, 38 and by Cockayne in 1912 11 as “catarrhal jaundice.” In 1968, Ackerknecht 39 recorded nine episodes of “epidemic jaundice” during the 17th and 18th centuries in Europe, including outbreaks in Germany (1629), Flanders (1764), Geneva (1742), and Genoa (1793). Such outbreaks had also been recognized as affecting military troops during wars (i.e., the American Civil War in the 19th century, as well as the First and Second World Wars) and were referred to as “campaign jaundice.” 2 In retrospect, these epidemics were presumably caused by HAV. Less likely, although possible, some of those outbreaks may have been caused by the hepatitis E virus. 5 , 40

Hepatitis A outbreaks were, however, not limited to the military. Several epidemics were noted in the United States during the 19th century. 2 , 5 One of the largest recorded epidemics of HAV in modern times occurred in 1988 in Shanghai, where almost 300,000 subjects experienced clinical symptoms of hepatitis A after ingestion of contaminated raw clams. 41 , 42 Other outbreaks were reported in the past three decades, that is, in patients with hemophilia who received factor VIII concentrates, 43 , 44 in MSM, 18 as well as in patients with HIV. 20 The many synonyms that have been coined in the past for “hepatitis” (Table 1) reflect the uncertainty regarding etiology, whether obstructive or infectious.

Table 1.

Synonyms for Viral Hepatitis

|

Reproduced with permission from World Health Organization. 81 Copyright 1973, World Health Organization.

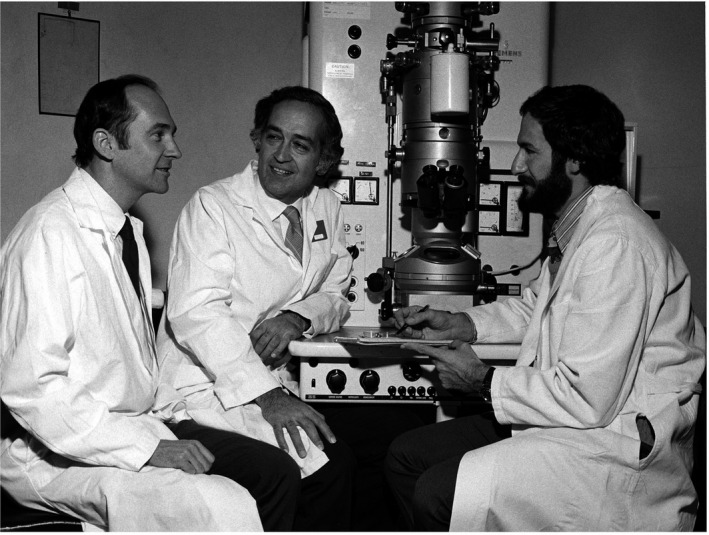

A causative yet unidentified infectious agent leading to liver injury was already suspected in 1908 45 and then again in the 1940s following outbreaks of hepatitis among military troops of the Allied and the German forces alike during the Second World War. 2 Around this period, Dr. F.O. MacCallum came to the conclusion that there are two types of hepatitis, which he classified as “infectious hepatitis” (later identified as hepatitis A‐HAV infection) and “homologous serum hepatitis” 12 , 46 (later labeled as hepatitis B virus [HBV] infection). This old classification corresponds to the MS1 and MS2 stratification used at the Willowbrook Institute during the controversial, yet important human transmission and prevention studies by Krugman et al. 35 Proof for this distinction between the two hepatitis‐causing agents came following serological and morphological identification of the HBV agent, which was originally designated as the “Australia antigen,” later identified as the HBV surface protein or HBsAg (hepatitis B surface antigen) by Blumberg and colleagues. 47 The noteworthy and remarkable detection of HAV by Feinstone et al. 1 in the United States using immune electron microscopy (Figs. 1 and 5), and confirmed by Stephen Locarnini, Ian Gust, and coworkers 48 in Australia, enabled a clear morphological and serological distinction to be made between HAV and HBV.

Fig 5.

Stephen Feinstone, Robert Purcell, and Albert Kapikian. Identification of HAV by electron microscopy at the US National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Photo courtesy of Office of NIH History and Stetten Museum, U.S. National Institutes of Health.

During the past four decades, scientists at the CDC, the World Health Organization, the Eurosurveillance system, and academia all contributed to a number of major breakthroughs and observations in understanding the epidemiology, immunology, and molecular pathophysiology of HAV. These included, among others, the results of transmission experiments of HAV from human fecal isolates to marmosets initially by Fritz Deinhardt, 49 , 50 , 51 HAV isolation and initial physical characterization by G. Siegl and G.G. Froesner, 52 , 53 , 54 propagation and attenuation of HAV in culture by Phil Provost and Maurice Hilleman 55 at Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD), isolation of an HAV strain by Ian Gust and coworkers 56 at the Fairfield Hospital for Communicable Diseases, Victoria, Australia, and by Robert Purcell and coworkers 57 at the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease. Their efforts in serial propagation of HAV in culture led to the establishment of two attenuated HAV strains in MRC‐5 cells, namely, HM‐175 (originally a wild‐type virus isolated by Ian Gust 56 in Australia) and CR 326 (a wild‐type virus originating from Costa Rica by V.M. Villarejos 23 ). The then putative virus was propagated in vivo in marmosets by Friedrich Deinhardt and attenuated through serial passages in tissue culture by Phil Provost. 55 , 58 Further progress was achieved in understanding the epidemiology and pathophysiology of HAV infection through the establishment of serological antibody assays for the diagnosis of acute (anti‐HAV [immunoglobulin M (IgM)]) and past (anti‐HAV [immunoglobulin G (IgG)]) HAV infection, 25 , 27 , 28 , 29 as well as transmission studies in vitro and in vivo in chimpanzees by Suzanne Emerson, Robert Purcell, and colleagues. 57 , 59 Major progress has been achieved in molecular cloning of the HAV genome and its taxonomic classification by J.R. Ticehurst, R. Purcell and coworkers, 59 Stanley Lemon, 60 Omana Nainan, 28 and Betty Robertson. 44 Results obtained by these investigators expanded our knowledge on HAV genotypes and provided new tools for follow‐up of the molecular epidemiology of HAV infection. A number of investigators have made important contributions in understanding the attachment, uptake, replication, and release of HAV by infected hepatocytes 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 (see also review by Lemon et al. 24 ). In this context, it is noteworthy to mention some of the major contributions made by Stan Lemon (Fig. 6) and coworkers 24 , 61 , 65 , 66 , 67 over the past three decades in understanding the attachment, replication, and release of picornaviruses in general and HAV in particular.

Fig 6.

Stanley M. Lemon, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, a virologist and leader in investigation of hepatotropic RNA viruses.

In brief, nonparenteral infection usually occurs through ingestion of HAV‐contaminated food or fluids followed by viral penetration of the gut mucosa. HAV appears to reach the liver through the portal circulation. However, although HAV was demonstrated in intestinal crypts by immunofluorescence, replication was not verified in the gut, and hepatocytes are considered the primary site of replication.

Previously, HAV entry was thought to occur through a surrogate putative mucin‐like glycoprotein receptor or as a virus‐IgA complex. 24 Then experimental observations suggested that attachment and entry of HAV into hepatocytes may occur through a calcium‐dependent cellular receptor HAVcr/TIM‐1. 24 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 66 Finally and recently, endosomal gangliosides were shown as essential receptors for HAV. 67 After intracellular genome translation, polyprotein processing, and replication, the virus generates an immune‐mediated inflammatory process against the infected hepatocytes. HAV is then released into the blood encased in a protective host‐derived membrane termed eHAV, which presumably shields circulating virus from neutralizing antibodies. The quasi‐enveloped HAV (eHAV) is then shed into the bile and is found in feces as naked, nonenveloped virions. 61

Already in 1945, Neefe, Gellis, and Stokes 68 had presented proof that passive immunization with immune serum globulin (Ig) prepared by the Cohn’s fractionation method (much later shown to contain HAV IgG antibodies) was effective in postexposure prophylaxis of HAV. Postexposure and even preexposure prophylaxis with Ig has been shown to provide protection against HAV for several months with a good safety profile. 69 Yet, the potency of Ig products has been declining in recent years in parallel with the dwindling HAV (IgG) titers in the donors’ plasma that is used for manufacturing Ig. 70

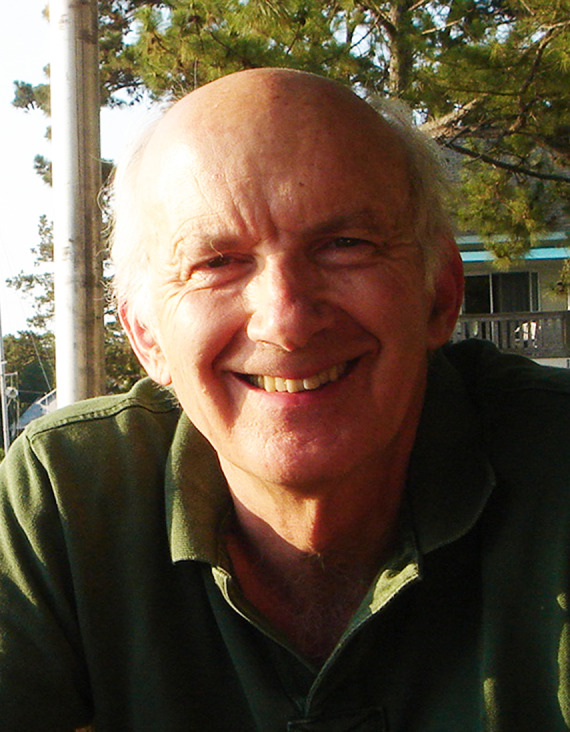

It took almost five decades from introduction of Ig until the successful development of safe, efficacious inactivated, as well as live attenuated, HAV vaccines. 15 These achievements in improving the means for active prophylaxis against HAV were mainly led by two pharmaceutical manufacturer teams, namely, the world pioneer in vaccine development Maurice Hilleman 9 , 73 (Fig. 7A) and his coworkers at MSD and Francis Andre 72 (Fig. 7B) and coworkers at GlaxoSmithKline (GSK; originally SmithKline Beecham). About a decade later, similar live attenuated and inactivated HAV vaccines were also developed in China 34 and in Switzerland. 71

Fig 7.

(A) Maurice R. Hilleman (1919‐2005) led the development of an inactivated hepatitis A vaccine at MSD, 9 , 73 “the most successful vaccinologist in history,” as described by Dr. Robert Gallo at the US National Institutes of Health. Reproduced with permission from Merck Archives. (B) Francis Andre, the late Vice President and Senior Medical Director at GSK Biologicals in Belgium who led the GSK hepatitis A vaccine program. 72 Courtesy of Blaine Hollinger.

The efforts of these pioneers, the late Drs. Hilleman and Andre, to develop an “active HAV vaccine” paved the way for two pivotal vaccine efficacy controlled trials. These trials involving large cohorts of vaccinees required the planning of an intervention—for proof of efficacy—during an outbreak of a disease that often remained subclinical. GSK and MSD independently have initiated such phase 3 controlled clinical trials, using the attenuated HAV strains (HM‐175 and CR326, respectively), formulated with aluminum hydroxide that had been serially propagated in mammalian cell culture, inactivated by formaldehyde, and suspended in aluminum hydroxide.

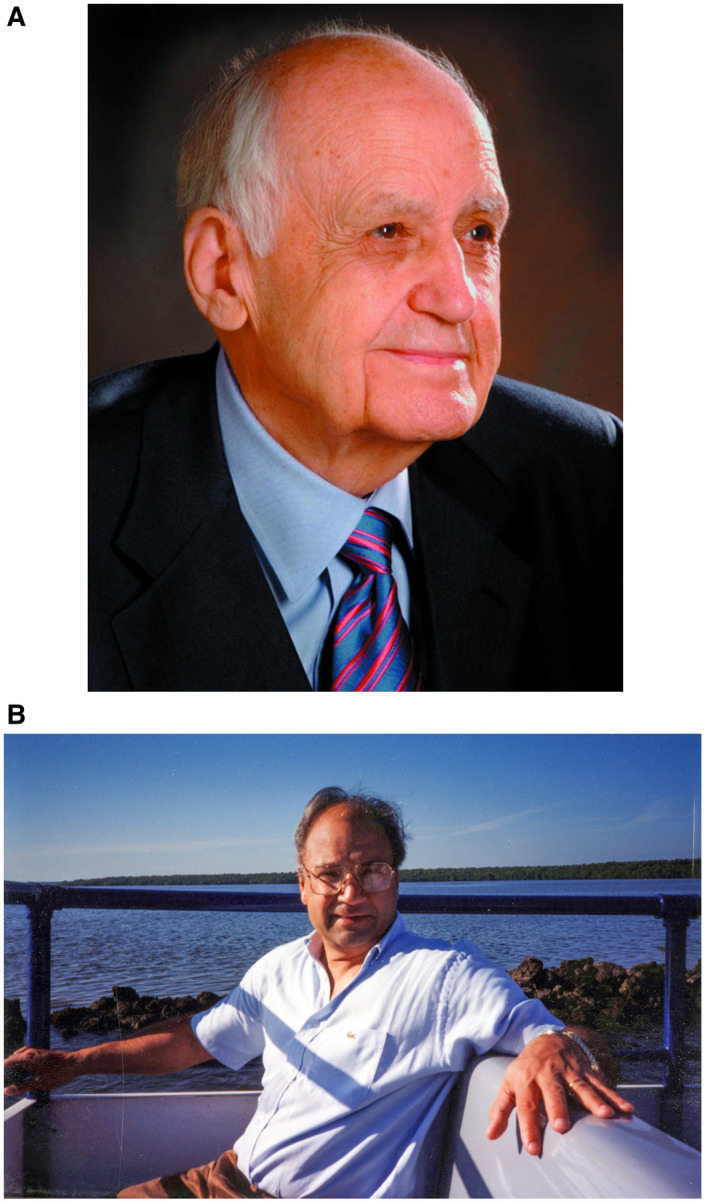

In Thailand, GSK recruited 40,119 children (1‐16 years old) to receive three injections at day 0, month 1, and month 12 of either a formaldehyde‐inactivated HAV vaccine or a control vaccine, with crossover after a year to an alternative vaccine. Protective efficacy rate against HAV before and 5 months after a 1‐year booster was 94% and 99%, respectively, without serious adverse events 32 (Fig. 8).

Fig 8.

Cumulative rates of symptomatic infection with HAV in the hepatitis A vaccine and control group trial in Thailand. HAV vaccine or control vaccine was administered at 0, 1, and 12 months. Reproduced with permission from JAMA. 32 Copyright 1994, American Medical Association.

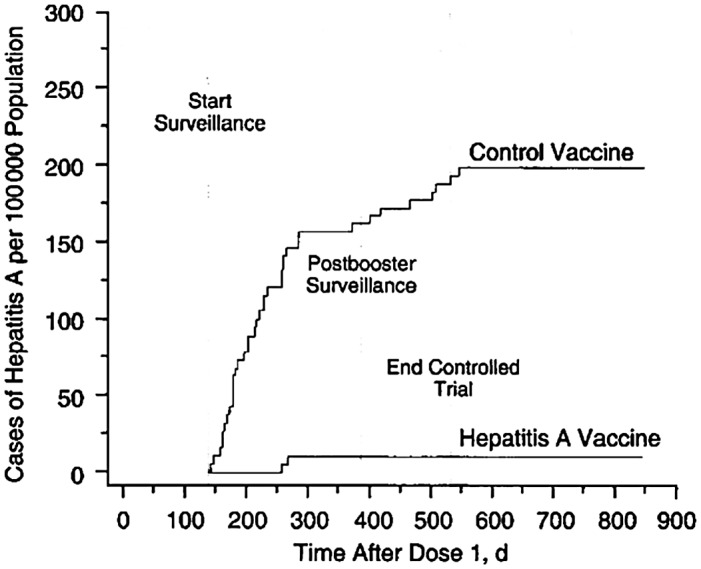

In the United States, MSD had initially considered a logistically challenging clinical trial among either Native American Indians or Alaskan Natives, who were known to have cyclical outbreaks of HAV infection. Meanwhile and serendipitously during these preparations, the CDC was informed of a hepatitis A outbreak in an orthodox Jewish community in Monroe in Upstate New York. The high attack rate of HAV in this town and the relative self‐seclusion of its residents enabled the design of a clinical efficacy trial by David Nalin, Alan Werzberger, Daniel Shouval, and coworkers 30 , 31 with a much smaller sample size than in the Thai study. At the beginning of an outbreak, 1037 healthy seronegative children (2‐16 years) were randomized to receive a single intramuscular injection of the formalin‐inactivated HAV vaccine or placebo. Before day 21, seven cases occurred in the vaccine group and three cases in the placebo group. Thereafter, there were no new cases among vaccine recipients, but there were 34 cases among placebo recipients, indicating 100% protective efficacy (P < 0.001). Further follow‐up confirmed the disappearance of cyclical hepatitis A outbreaks in the Monroe community (Fig. 9). Other data suggested that active vaccination that was administered within 16 days of HAV exposure would also be effective for postexposure prophylaxis. 30 , 31 , 78

Fig 9.

Quarterly follow‐up (1985‐2000) of new hepatitis A cases in the Monroe community following the clinical vaccine efficacy trial in 1993. 31 Reproduced with permission from Vaccine. 82 Copyright 2002, Elsevier.

Following these two important clinical trials, the GSK vaccine (HAVRIX) and the MSD vaccine (VAQTA) were licensed in the mid‐1990s in the United States and worldwide. Another HAV vaccine containing attenuated inactivated HAV suspended with virosomes as an adjuvant (which is currently unavailable) was developed in Switzerland and tested successfully in Nicaragua. 71

Immune memory against HAV, following injection of vaccine, irrespective if it is inactivated or live attenuated, persists for years and, as shown for formaldehyde‐inactivated vaccines, lasts at least for 22 years without the necessity of a booster dose. 74 , 75 , 76 , 80

Initially, immunization was offered only to defined groups deemed at high risk to contract HAV infection or to children residing in HAV‐endemic regions. 15 Later, mass immunization campaigns in babies had an impressive impact on the incidence of HAV infection, not only in children but also in adults in Europe, Asia, and the United States. 15 , 76 In this setting, I would be remiss not to mention that Israel was the first, so far, of 11 countries to introduce universal mass immunization (UMV) against HAV to toddlers using a two‐dose schedule. 77 Consequently, hepatitis A became an almost extinct disease in immunized Israeli children, as well as in nonimmunized adults 24 (Fig. 10), likely through a vaccination‐induced herd effect. As of February 2020, HAV vaccination has been introduced by 40 countries worldwide, either in routine childhood immunization programs or in particular risk groups.

Fig 10.

Impact of UMV of toddlers on the overall incidence of acute hepatitis A in Israel. UMV was started in 1999 with administration of an inactivated HAV vaccine, HAVRIX, at 10 μg/dose, at 18 and 24 months of age. 24 Reproduced with permission from Journal of Hepatology. 24 Copyright 2018, European Association for the Study of the Liver.

The use of both postexposure and preexposure Ig has dwindled following a successful controlled trial, conducted in Kazakhstan, of an active vaccine versus Ig for protection against clinical hepatitis A, if given within 16 days of HAV exposure. 31 , 78

Finally, the extraordinary immunogenicity of HAV vaccines was recently demonstrated in Argentina and neighboring countries, where the incidence of viral hepatitis A and its complications declined significantly in healthy and immune‐competent subjects immunized with only a single dose of an inactivated HAV vaccine. 79 , 80 A similar response was also observed in Chinese children immunized with a single dose of a live attenuated HAV vaccine. 34 , 80

In summary, whereas HAV infection has afflicted humans for thousands of years, recent advances in molecular tools for diagnosis and follow‐up of HAV, the development of efficacious vaccines, and improved socioeconomic conditions are contributing to the control of hepatitis A worldwide. If only these successes could be replicated with influenza and other viral, potentially deadly scourges, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome, Middle East respiratory syndrome, Ebola, and especially with COVID‐19, which is now a pandemic the threat of which has yet to be fully realized.

Series Editor’s Postscript

In the field of viral hepatitis studies and especially that of HAV, Daniel “Dani” Shouval is the very reverse of an “upstart.” This is hardly unexpected, because he comes from a “Startup Nation,” as Israel has been dubbed by journalists Dan Senior and Saul Singer (in their 2009 monograph), on account of the country’s entrepreneurship in science, medicine, technology, and agriculture. All puns aside, however, Dani Shouval has been a leading light and entrepreneur himself in the medical science of HAV, as shown by this scholarly testimony to the evolution of our understanding of the virus, and particularly of its prevention and postexposure treatment. Indeed, the results of Dani’s own seminal studies in HAV vaccination greatly inform current practice worldwide.

The HAV story is in many ways unique in the annals of hepatology, because we virtually have closure now that there is effective immunization, although not yet antiviral therapy for which there has really been no need. The history of HAV begins with the recognition that the acute liver injury that the Ancients described, and that ravaged civilian and military populations throughout the centuries, can be divided into those hepatitides that are transmitted enterally, as is the case with HAV and hepatitis E virus infections, and those that are passed on by the parental route, namely, hepatitis B, C, and D. After identification and isolation of HAV itself came its molecular characterization, propagation studies, and identification of routes of transmission and populations at risk, culminating in the development of safe effective vaccines. A glimpse at the bibliography of this essay unequivocally reveals Dani’s dedication to hunting down and nullifying the reach of this submicroscopic scourge.

Finally, let us end this postscript on an onomastic note, regarding the abbreviation Dani, of Daniel Shouval’s first or given name. Daniel has been used an English forename since the Middle Ages and especially so since the Protestant Reformation. As such, we would expect the abbreviation to be the simple truncation Dan, the formal contraction Danl (Dan’l), or Danny with its diminutive suffix “y,” which begins as Child Directed Speech or “Parentese,” that imparts a sense of familiarity, intimacy, tenderness, and even possessiveness. In English, the “n” is doubled to facilitate pronunciation. But for the author of the current essay, Daniel, which is translated as “Judge of God,” from the right‐to‐left Hebrew לאינד (creatively imagined by Gustave Doré in the woodcut print below), is for Prof. Shouval not an English first name. Daniel Shouval is an Israeli of originally German/Austrian parentage. The diminutive truncation in Hebrew ends in the first‐person possessive suffix yod (י) as ינד, which transliterates into English as Dani; there is no need to double the “n” for pronunciation. However, despite Dani Shouval’s citizenship, it is in fact the German parentese Dani by which he has been familiarly known lifelong.

Acknowledgment:

This article was written as a tribute to my mentors, coworkers, and colleagues: Maurice Hilleman (deceased), Fritz Deinhardt (deceased) and Jean Deinhardt, Stanley Lemon, David Nalin, Omana Nainan (deceased), and Betty Robertson (deceased) whose work and my interaction with on hepatitis A have been a continuous inspiration for my personal involvement in the field of hepatitis A.

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

References

- 1. Feinstone S, Kapikian AZ, Purcell RH. Hepatitis A: detection by immune electron microscopy of a viruslike antigen associated with acute illness. Science 1973;182:1026‐1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zuckerman AJ. The history of viral hepatitis from antiquity to the present In: Deinhardt F, Deinhardt J, eds. Viral Hepatitis. Laboratory and Clinical Science. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1983:3‐34. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kulkarni MA, Walimbe AM, Cherian S, et al. Full length genomes of genotype IIIA Hepatitis A Virus strains (1995‐2008) from India and estimates of the evolutionary rates and ages. Infect Genet Evol 2009;9:1287‐1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smith DB, Simmonds P. Classification and genomic diversity of enterically transmitted hepatitis viruses. In: Enteric Hepatitis Viruses, Edts SM Lemon and CCM Walker. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2018;37‐51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Teo CG. 19th‐century and early 20th‐century jaundice outbreaks, the USA. Epidemiol Infect 2018;146:138‐146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Martin A, Lemon SM. Hepatitis A virus: from discovery to vaccines. Hepatology 2006;43:S164‐S172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Payen JL, Rongieres M. History of hepatitis. I. From jaundice to viruses. Rev Prat 2002;52:2097‐2100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Payen JL,Rongieres M. History of hepatitis. 2. Identification of epidemic hepatitis. Rev Prat 2002;52:2213‐2217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hilleman MR. Hepatitis and hepatitis A vaccine: a glimpse of history. J Hepatol 1993;18(Suppl. 2):S5‐S10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Froesner GG. Epidemiology of hepatitis A In: Zuckerman AJ, ed. Viral Hepatitis: Laboratory and Clinical Science. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1983:201‐214. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cockayne A. Catarrhal jaundice sporadic and epidemic and its relation to acute yellow atrophy of the liver. QJM 1912;6:1‐29. [Google Scholar]

- 12. MacCallum FO. Historical perspectives. In-Proceedings of the Canadian Hepatic Foundation Symposium on viral hepatitis, Toronto, Canada May 1971. Can Med Assoc J 1972;106:423‐426. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lemon SM, Walker CM. Enteric hepatitis viruses In: Lemon SM, Walker C, eds. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2019;1‐393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shouval D. Hepatitis A virus In: Viral Infections of Humans Kaslow RA, Stanberry LS, LeDuc JW, eds. New York: Springer; 2014:417‐438. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shouval D, Van Damme P. World Health Organization . The Immunological Basis for Immunization Series; Module 18: Hepatitis A, Update 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019:1‐58. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Enkirch T, Eriksson R, Persson S, et al. Hepatitis A outbreak linked to imported frozen strawberries by sequencing, Sweden and Austria, June to September 2018. Euro Surveill 2018;23:1800528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Beaute J, Westrell T, Schmid D, et al. Travel‐associated hepatitis A in Europe, 2009 to 2015. Euro Surveill 2018;23:1700583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ndumbi P, Freidl GS, Williams CJ, et al. Hepatitis A outbreak disproportionately affecting men who have sex with men (MSM) in the European Union and European Economic Area, June 2016 to May 2017. Euro Surveill 2018;23:1700641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nelson R. Hepatitis A outbreak in the USA. Lancet Infect Dis 2018;18:33‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Foster M, Ramachandran S, Myatt K, et al. Hepatitis A virus outbreaks associated with drug use and homelessness ‐ California, Kentucky, Michigan, and Utah, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:1208‐1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee YL, Chen GJ, Chen NY, et al. Less severe but prolonged course of acute hepatitis A in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)‐infected patients compared with HIV‐uninfected patients during an outbreak: a multicenter observational study. Clin Infect Dis 2018;67:1595‐1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Foster MA, Hofmeister MG, Kupronis BA, et al. Increase in hepatitis A virus infections ‐ United States, 2013‐2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:413‐415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Villarejos VM, Serra J, Anderson‐Visona K, et al. Hepatitis A virus infection in households. Am J Epidemiol 1982;115:577‐586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lemon SM, Ott JJ, Van Damme P, et al. Type A viral hepatitis: a summary and update on the molecular virology, epidemiology, pathogenesis and prevention. J Hepatol 2018;68:167‐184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Decker RH, Kosakowski SM, Vanderbilt AS, et al. Diagnosis of acute hepatitis A by HAVAB‐M, a direct radioimmunoassay for IgM anti‐HAV. Am J Clin Pathol 1981;76:140‐147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Decker RH, Overby LR, Ling CM, et al. Serologic studies of transmission of hepatitis A in humans. J Infect Dis 1979;139:74‐82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hollinger FB, Bradley DW, Dreesman GR, et al. Detection of viral hepatitis type A. Am J Clin Pathol 1976;65:854‐865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nainan OV, Xia G, Vaughan G, et al. Diagnosis of hepatitis a virus infection: a molecular approach. Clin Microbiol Rev 2006;19:63‐79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Phan C, Hollinger FB. Hepatitis A: natural history, immunopathogenesis, and outcome. Clin Liver Dis 2013;2:231‐234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Werzberger A, Kuter B, Nalin D. Six years' follow‐up after hepatitis A vaccination. Lt. N Engl J Med 1998;338:1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Werzberger A, Kuter B, Shouval D, et al. Anatomy of a trial: a historical view of the Monroe inactivated hepatitis A protective efficacy trial. J Hepatol 1993;18(Suppl. 2):S46‐S50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Innis BLSR, Kunasol P, et al. Protection against hepatitis A by an inactivated vaccine. JAMA 1994;271:1328‐1334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shouval D. Immunization against hepatitis A. In: Enteric Hepatitis Viruses, Edts SM.Lemon and CM. Walker. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med; NY, 2018;361‐375. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cui F, Hadler SC, Zheng H, et al. Hepatitis A surveillance and vaccine use in China from 1990 through 2007. J Epidemiol 2009;19:189‐195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Krugman S, Giles JP. Viral hepatitis. New light on an old disease. JAMA 1970;212:1019‐1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mohd Hanafiah K, Jacobsen KH, Wiersma ST. Challenges to mapping the health risk of hepatitis A virus infection. Int J Health Geogr 2011;10:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bamberge H, ed. Krakheiten des Chylopoetischen Systeme. In: Virchow’s Handbuch der Pathologie und Therapie Vol. 5. 1855. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Virchow R. Ueber das Vorkommen und den Nachweiss der Hepatogenen insbesondere das Katarrhalischen Icterus. Virchow's Arch Pathol Anat Physiol 1865;32:117‐125. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ackerknecht EH. The vagaries of the notion of epidemic hepatitis or infectious jaundice In: Stevenson LD, Multhauf RP, eds. Medicine, Science and Culture. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins Press; 1968:4‐7. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Seth A, Sherman KE. Hepatitis E: what we think we know. Clin Liver Dis 2020;15:S37‐S44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Halliday ML, Kang LY, Zhou TK, et al. An epidemic of hepatitis A attributable to the ingestion of raw clams in Shanghai, China. J Infect Dis 1991;164:852‐859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cooksley WG. What did we learn from the Shanghai hepatitis A epidemic? J Viral Hepatitis 2000;7(Suppl. 1):1‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mannucci PM, Gdovin S, Gringeri A, et al. Transmission of hepatitis A to patients with hemophilia by factor VIII concentrates treated with organic solvent and detergent to inactivate viruses. The Italian Collaborative Group. Ann Intern Med 1994;120:1‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Robertson BH, Friedberg D, Normann A, et al. Sequence variability of hepatitis A virus and factor VIII associated hepatitis A infections in hemophilia patients in Europe. An update. Vox Sang 1994;67(Suppl. 1):39‐45, discussion 6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. McDonald E. Acute yellow atrophy. Edinb Med J 1908;15:208. [Google Scholar]

- 46. MacCallum F. Homologous serum jaundice. Lancet 1947;2:691. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Blumberg BS, Alter HJ, Visnich S. A “new” antigen in leukemia sera. JAMA 1965;191:541‐546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Locarnini SA, Ferris AA, Stott AC, et al. The relationship between a 27‐nm virus‐like particle and hepatitis A as demonstrated by immune electron microscopy. Intervirology 1974;4:110‐118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Deinhardt F, Holmes AW, Capps RB, et al. Studies on the transmission of human viral hepatitis to marmoset monkeys. I. Transmission of disease, serial passages, and description of liver lesions. J Exp Med 1967;125:673‐688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Deinhardt F, Holmes AW, Wolfe L, et al. Transmission of viral hepatitis to nonhuman primates. Vox Sang 1970;19:261‐269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Deinhardt F, Holmes AW, Wolfe LG. Hepatitis in marmosets. J Infect Dis 1970;121:351‐352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Siegl G, Frosner GG. Characterization and classification of virus particles associated with hepatitis A. I. Size, density, and sedimentation. J Virol 1978;26:40‐47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Siegl G, Frosner GG, Gauss‐Muller V, et al. The physicochemical properties of infectious hepatitis A virions. J Gen Virol 1981;57:331‐341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Siegl G, Weitz M, Kronauer G. Stability of hepatitis A virus. Intervirology 1984;22:218‐226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Provost PJ, Hilleman MR. Propagation of human hepatitis A virus in cell culture in vitro. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1979;160:213‐221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Gust ID, Lehmann NI, Crowe S, et al. The origin of the HM175 strain of hepatitis A virus. J Infect Dis 1985;151:365‐367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Funkhouser AW, Purcell RH, D'Hondt E, et al. Attenuated hepatitis A virus: genetic determinants of adaptation to growth in MRC‐5 cells. J Virol 1994;68:148‐157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Provost PJ, Ittensohn OL, Villarejos VM, et al. A specific complement‐fixation test for human hepatitis A employing CR326 virus antigen. Diagnosis and epidemiology. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1975;148:962‐969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Purcell RH, D'Hondt E, Bradbury R, et al. Inactivated hepatitis A vaccine: active and passive immunoprophylaxis in chimpanzees. Vaccine 1992;10(Suppl. 1):S148‐S151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lemon SM. Type A viral hepatitis: epidemiology, diagnosis, and prevention. Clin Chem 1997;43:1494‐1499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Feng Z, Hensley L, McKnight KL, et al. A pathogenic picornavirus acquires an envelope by hijacking cellular membranes. Nature 2013;496:367‐371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bishop NE, Anderson DA. Uncoating kinetics of hepatitis A virus virions and provirions. J Virol 2000;74:3423‐3426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Thompson P, Lu J, Kaplan GG. The Cys‐rich region of hepatitis A virus cellular receptor 1 is required for binding of hepatitis A virus and protective monoclonal antibody 190/4. J Virol 1998;72:3751‐3761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Qu L, Feng Z, Yamane D, et al. Disruption of TLR3 signaling due to cleavage of TRIF by the hepatitis A virus protease‐polymerase processing intermediate, 3CD. PLoS Pathog 2011;7:e1002169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Hirai‐Yuki A, Whitmire JK, Joyce M, et al. Murine models of hepatitis A virus infection. In‐Edts. SM Lemon & CM Walker. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2018;143‐162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Das A, Maury W, Lemon SM. TIM1 (HAVCR1): an essential "receptor" or an "accessory attachment factor" for hepatitis A virus? J Virol 2019;93:e01793‐18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Das A, Barrientos R, Shiota T, et al. Gangliosides are essential endosomal receptors for quasi‐enveloped and naked hepatitis A virus. Nat Microbiol 2020. 10.1038/s41564-020-0727-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Neefe JR, Gellis SS, Stokes J Jr. Homologous serum hepatitis and infectious (epidemic) hepatitis; studies in volunteers bearing on immunological and other characteristics of the etiological agents. Am J Med 1946;1:3‐22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Liu JP, Nikolova D, Fei Y. Immunoglobulins for preventing hepatitis A. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;2:CD004181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Tejada‐Strop A, Costafreda MI, Dimitrova Z, et al. Evaluation of potencies of immune globulin products against hepatitis A. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:430‐432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Majorga O, Buhler S, Jaeger VK, et al. Single‐dose hepatitis A immunization: 7.5‐year observational pilot study in Nicaraguan children to assess protective effectiveness and humoral immune memory response. J Infect Dis 2016;214:1498‐1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Andre FE. Universal mass vaccination against hepatitis A. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2006;304:95‐114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Oransky I, Maurice R. Hilleman. Lancet 2005;365:1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Van Damme P, Leroux‐Roels G, Suryakiran P, et al. Persistence of antibodies 20 y after vaccination with a combined hepatitis A and B vaccine. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2017;13:972‐980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Mosites E, Gounder P, Snowball M, et al. Hepatitis A vaccine immune response 22 years after vaccination. J Med Virol 2018;90:1418‐1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Stuurman AL, Marano C, Bunge EM, et al. Impact of universal mass vaccination with monovalent inactivated hepatitis A vaccines ‐ a systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2017;13:724‐736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Dagan R, Leventhal A, Anis E, et al. Incidence of hepatitis As in Israel following universal immunization of toddlers. JAMA 2015;294:202‐210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Victor JC, Monto AS, Surdina TY, et al. Hepatitis A vaccine versus immune globulin for post exposure prophylaxis. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1685‐1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Urueña A, González JE, Rearte A, et al. Single‐dose universal hepatitis a immunization in one‐year‐old children in argentina: high prevalence of protective antibodies up to 9 years after vaccination. J Pediatr Infect Dis J 2016;35:1339‐1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Chen Y, Zhou CL, Zhang XJ, et al. Immune memory at 17‐years of follow‐up of a single dose of live attenuated hepatitis A vaccine. Vaccine 2018;36:114‐121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. WHO Scientific Group on Viral Hepatitis & World Health Organization . Viral hepatitis: report of a WHO scientific group. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1973. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/41024 [Google Scholar]

- 82. Werzberger A, Mensch B, Nalin DR, et al. Effectiveness of hepatitis A vaccine in a former frequently affected community: 9 years’ followup after the Monroe field trial of VAQTA. Vaccine 2002;20:1699‐1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]