Abstract

Objective

To assess treatment related changes in quality of life up to 15 years after diagnosis of localised prostate cancer.

Design

Population based, prospective cohort study with follow-up over 15 years.

Setting

New South Wales, Australia.

Participants

1642 men with localised prostate cancer, aged less than 70, and 786 controls randomly recruited from the New South Wales electoral roll into the New South Wales Prostate Cancer Care and Outcomes Study (PCOS).

Main outcome measures

General health and disease specific quality of life were self-reported at seven time points over a 15 year period, using the 12-item Short Form Health Survey scale, University of California, Los Angeles prostate cancer index, and expanded prostate cancer index composite short form (EPIC-26). Adjusted mean differences were calculated with controls as the comparison group. Clinical significance of adjusted mean differences was assessed by the minimally important difference, defined as one third of the standard deviation (SD) from the baseline score.

Results

At 15 years, all treatment groups reported high levels of erectile dysfunction, depending on treatment (62.3% (active surveillance/watchful waiting, n=33/53) to 83.0% (non-nerve sparing radical prostatectomy, n=117/141)) compared with controls (42.7% (n=44/103)). Men who had external beam radiation therapy or high dose rate brachytherapy or androgen deprivation therapy as primary treatment reported more bowel problems. Self-reported urinary incontinence was particularly prevalent and persistent for men who underwent surgery, and an increase in urinary bother was reported in the group receiving androgen deprivation therapy from 10 to 15 years (year 10: adjusted mean difference −5.3, 95% confidence interval −10.8 to 0.2; year 15: −15.9; −25.1 to −6.7).

Conclusions

Patients receiving initial active treatment for localised prostate cancer had generally worse long term self-reported quality of life than men without a diagnosis of prostate cancer. Men treated with radical prostatectomy faired especially badly, particularly in relation to long term sexual outcomes. Clinicians and patients should consider these long term quality of life outcomes when making treatment decisions.

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the second most common cancer in men and the fourth most prevalent of all cancer types.1 In 2018, 1.3 million men were diagnosed with prostate cancer worldwide. Most prostate cancers in high income countries are localised when diagnosed (clinical stage T1a to T2c, no evidence of lymph node invasion or distant metastases).1 2 Localised prostate cancer has a five year relative survival rate of nearly 100% compared with the general population; survival rates at all stages are 98% and 96% at 10 and 15 years, respectively.3 Consequently, it has become increasingly important to consider quality of life outcomes associated with different treatments in treatment decision making.4 5 Short term quality of life outcomes have been extensively documented, but only a few reports have evaluated long term (10 or more years) quality of life and survival associated with different treatment options.6 7

In recent systematic reviews and meta-analysis of quality of life in patients with localised prostate cancer (2017,6 20187), follow-up primarily focused on short term (one to three years) or intermediate term (four to five years) self-reported outcomes. Only one study has reported quality of life outcomes up to 15 years after diagnosis, finding no significant long term differences for any quality of life domains in patients with localised prostate cancer receiving the two most common prostate cancer treatments—radical prostatectomy and external beam radiation therapy.8 That study was limited, however, as it compared outcomes from only two types of treatment, and did not have a control group of men, without a diagnosis of prostate cancer, for comparison.

The New South Wales Prostate Cancer Care and Outcomes Study (PCOS) followed up a population based sample of men diagnosed with localised prostate cancer and age matched controls. The study reported three year, health related, quality of life outcomes for patients with localised prostate cancer (2009),9 10 year quality of life outcomes for those who underwent active surveillance or watchful waiting as primary management (2018),10 and the unmet supportive care needs of the cohort at a 15 year follow-up.11 Our paper reports quality of life outcomes at 15 years after diagnosis.

Our primary aim was, firstly, to describe long term self-reported quality of life associated with the different common treatment approaches for men with localised prostate cancer in comparison with population based controls. Secondly, to determine the extent to which previously self-reported changes in continence, potency, bowel function, and overall wellbeing at three and 10 years of follow-up were still present and problematic at 15 years.

Methods

Study sample

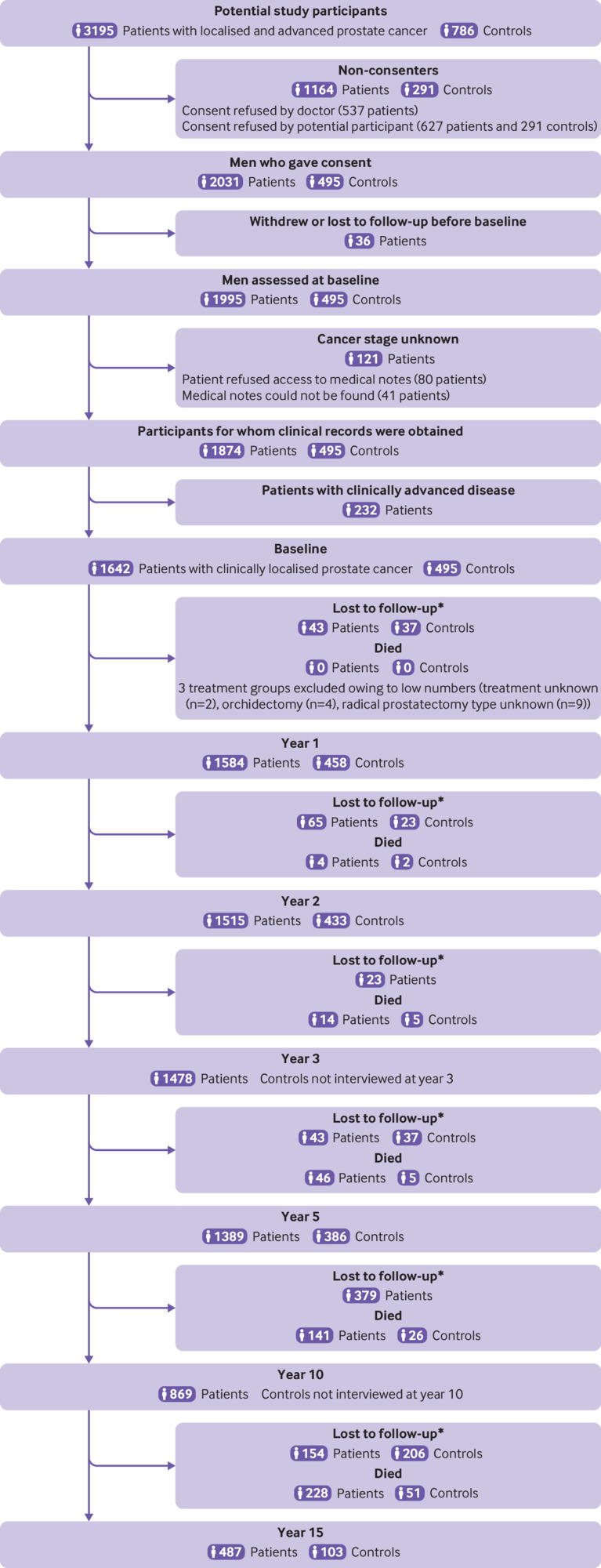

PCOS is a population wide, longitudinal cohort study conducted in New South Wales, Australia’s most populous state. A total of 3195 men aged less than 70 years with histopathologically confirmed T1 to T4 prostate cancer diagnosed between October 2000 and October 2002 were identified through the New South Wales Cancer Registry and invited to participate (fig 1). Baseline questionnaires, related to the month before diagnosis, were completed as soon as practicable after recruitment (mean 3 months, range 1-12 months). Participants at baseline with adequate clinical records (n=1874) completed follow-up surveys, when willing and possible, at 1, 2, 3, 5, 10, and 15 years after diagnosis; 1642 of these men had localised prostate cancer. Participants were contacted for each subsequent follow-up by calling the last known contact number. Participants were also asked to provide a contact number for a family member or friend who might give some information (including a current contact number) about participants lost to follow up. Additionally, a death linkage was completed with data from all participants by searching in the National Death Index held by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare before the 15 year follow-up to avoid attempting to contact family or friends of those who had died. Number of deaths by year of follow-up are displayed in table S1.

Fig 1.

Flow diagram showing patient and control participation and follow-up. *Lost to follow-up includes study participants who did not participate in the interview for that year but could have participated in subsequent interview years; controls who were diagnosed with prostate cancer after baseline and who were censored from date of diagnosis (n=35). Lost to follow-up frequencies not available for controls in the time periods preceding years 3 and 10 because controls were not interviewed in those years

At baseline, 786 men were randomly selected from the New South Wales electoral roll as control participants and were matched by age and post code of residence to patients on a 1:4 ratio. Potential controls were checked against the New South Wales Cancer Registry to exclude those with a previous diagnosis of prostate cancer. Controls were also excluded if they lacked sufficient command of the English language to complete the survey or did not reside in New South Wales.9 No other exclusion criteria were used. In total, 495 (63.0%) controls of 786eligible men contacted, consented and completed baseline surveys.9 These controls completed questionnaires at 1, 2, 5, and 15 years after recruitment. Our analyses include 1642 men diagnosed with localised prostate cancer and 495 controls (table 1 and table S2).

Table 1.

Prostate Cancer Care and Outcomes Study questionnaire completion rates by treatment and control groups

| Follow-up year | Participant category (type of treatment or control) (No who completed/Total No in group (%)) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS/WW | NSRP | Non-NSRP | RP type unknown* | EBRT/HDR | ADT | LDR | Orchidectomy* | Primary treatment unknown* |

Total cases† | Controls‡ | |

| Baseline | 200/200 (100) | 494/494 (100) | 478/478 (100) | 9/9 (100) | 170/170 (100) | 227/227 (100) | 58/58 (100) | 4/4 (100) | 2/2 (100) | 1642/1642 (100) | 495/495 (100) |

| 1 | 190/200 (95) | 486/494 (98) | 470/478 (98) | 9/9 (100) | 165/170 (97) | 217/227 (96) | 57/58 (98) | 3/4 (75) | 2/2 (100) | 1599/1642 (97) | 458/495 (93) |

| 2 | 178/200 (89) | 472/494 (96) | 443/478 (93) | 9/9 (100) | 163/170 (96) | 204/227 (90) | 56/58 (97) | 3/4 (75) | 2/2 (100) | 1530/1642 (93) | 433/495 (87) |

| 3 | 175/200 (88) | 458/494 (93) | 439/478 (92) | 9/9 (100) | 153/170 (90) | 199/227 (88) | 56/58 (97) | 2/4 (50) | 2/2 (100) | 1493/1642 (91) | N/A |

| 5 | 160/200 (80) | 443/494 (90) | 424/478 (89) | 7/9 (78) | 142/170 (84) | 173/227 (76) | 51/58 (88) | 2/4 (50) | 2/2 (100) | 1404/1642 (86) | 386/495 (78) |

| 10 | 95/200 (48) | 307/494 (62) | 256/478 (54) | 4/9 (44) | 94/170 (55) | 88/227 (39) | 40/58 (69) | 0/4 | 0/2 | 884/1642 (54) | N/A |

| 15 | 53/200 (27) | 192/494 (39) | 141/478 (29) | 3/9 (33) | 43/170 (25) | 45/227 (20) | 25/58 (43) | 0/4 | 0/2 | 502/1642 (31) | 103/495 (21) |

ADT=androgen deprivation therapy with or without EBRT; AS/WW=active surveillance/watchful waiting; EBRT/HDR=external beam radiotherapy or high dose rate brachytherapy, or both; LDR=low dose rate brachytherapy; N/A=not applicable as controls did not complete follow-up during this year; non-NSRP=non-nerve sparing radical prostatectomy; NSRP=nerve sparing radical prostatectomy.

Excluded from multivariate regression analyses owing to low numbers.

Total participants include men who had treatment unknown, orchidectomy, and radical prostatectomy type unknown, who were excluded from the multivariate analysis.

35 controls who were diagnosed with prostate cancer after baseline were censored from their date of diagnosis.

Clinical and sociodemographic data

Trained researchers or treating clinicians extracted clinical data from relevant records between 12 and 24 months after the histological diagnosis of localised prostate cancer. Prostate-specific antigen level at diagnosis, Gleason score, clinical stage at diagnosis, and details of primary treatment were collected. Demographic data (table S2) were collected in the baseline surveys. Participant’s area of residence at diagnosis was classified according to the Accessibility and Remoteness Index of Australia (ARIA+ version).12

Treatment groups were based on choice of primary treatment, including surgery, nerve sparing radical prostatectomy (NSRP) or non-nerve sparing radical prostatectomy (non-NSRP); external beam radiation therapy and high dose rate brachytherapy; androgen deprivation therapy with or without external beam radiation therapy; and low dose rate brachytherapy. Because we were unable to ascertain whether conservatively managed patients were managed through active surveillance or watchful waiting, these patients were grouped together as active surveillance/watchful waiting. Patients in this group at baseline were analysed as active surveillance/watchful waiting regardless of whether they subsequently received active treatment.

Quality of life outcome measures

The University of California, Los Angeles prostate cancer index (UCLA-PCI)13 was used for baseline data collection. Subsequently, the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC),14 derived from the UCLA-PCI, and the EPIC Short Form (EPIC-26),15 became the “gold standard” measures for quality of life in prostate cancer and were used in all further follow-up. For longitudinal analysis, a subset of items common to both UCLA-PCI and EPIC-26 were calculated for five quality of life domains: urinary incontinence, urinary bother, sexual bother, sexual summary (referred to hereafter as sexual function, which broadly encompasses the ability to perform sexually and satisfaction with performance), and bowel bother. The mental and physical components of health were assessed in all surveys using the 12-item Short Form Health Survey scale.16 Standard scoring algorithms for each questionnaire were applied, which placed all quality of life scores on 100 point scales, with lower scores indicating poorer outcomes corresponding to more bother for the five domains.

Statistical analyses

To indicate the extent to which men treated for prostate cancer differed from controls over time, regression analyses with generalised estimating equation adjustment for the repeated observations on the same individual were used to estimate adjusted mean differences in quality of life scores between treatment groups and the control group17 (corresponding 95% confidence intervals were calculated but were not adjusted for multiple comparisons of group and timepoints). All mean differences were adjusted for a variety of demographic characteristics (listed in fig 2 and fig 3), comorbidity, and domain-specific quality of life or 12-item Short Form Health Survey baseline scores. Exchangeable working correlation structures, robust standard errors, identity link functions, and Gaussian distributions were used in all generalised estimating equation analyses.

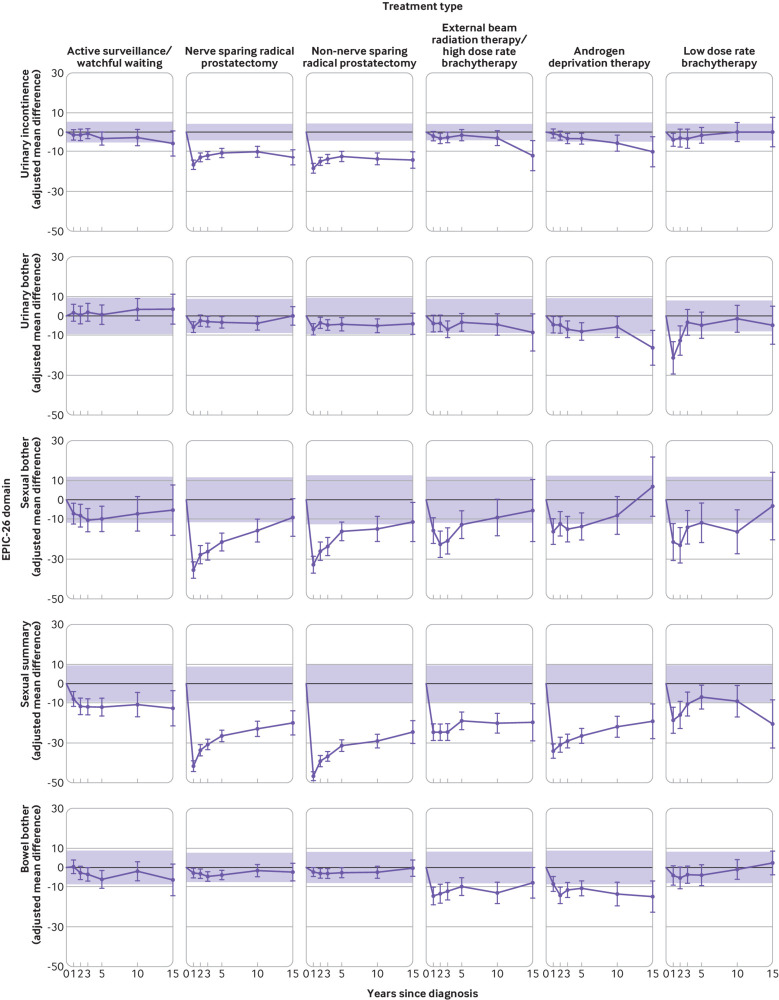

Fig 2.

Adjusted mean differences between treatment group (purple line) and control group (bold black line) follow‐up quality of life scores from expanded prostate cancer index composite short form, EPIC-26. Controls are the reference group (adjusted mean difference=0). Shading indicates the region outside of which adjusted mean differences exceed the minimally important difference. Minimally important difference limits are calculated as plus or minus one third of the pooled baseline standard deviation of the control group and of the treatment group. Adjusted mean differences are adjusted for baseline age, marital status, having private health insurance, region of residence, income, education, country of birth, comorbidity score, and domain-specific baseline (year 0) quality of life score

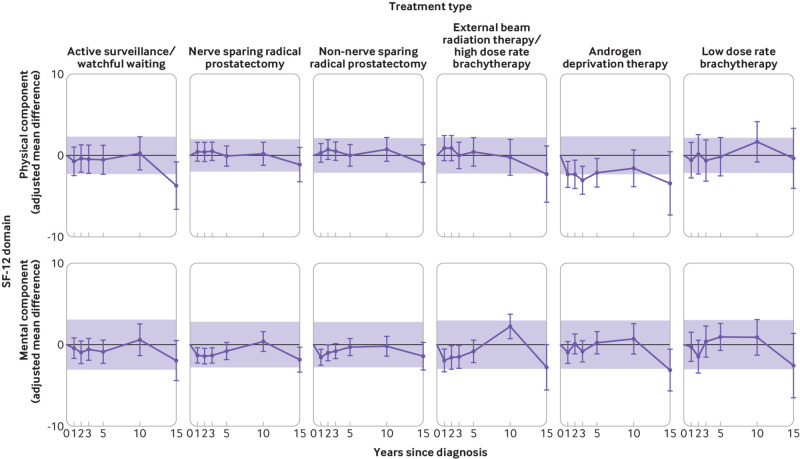

Fig 3.

Adjusted mean differences between initial treatment group (purple line) and control group (bold black line) follow‐up 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12) scores. Controls are the reference group (adjusted mean difference=0). Shaded region indicates adjusted mean differences within minimally important difference. Minimally important difference limits are calculated as plus or minus one third of the pooled baseline standard deviation of the control group and of the treatment group. Adjusted mean differences are adjusted for the following baseline characteristics: age, marital status, having private health insurance, region of residence, income, education, country of birth, comorbidity score, and domain‐specific baseline (year 0) 12-item Short Form Health Survey score

Because our primary interest was the association between treatment and self-reported quality of life at 1, 2, 3, 5, 10, and 15 years after diagnosis, interaction between treatment type and time since baseline was modelled using interaction and main effect terms. Control quality of life data were not collected at years 3 or 10; comparisons were achieved by modelling group mean trajectories as linear from year 2 to 5 and from year 5 to 15.

In our main analysis, we used men without prostate cancer as the control (reference) group because we believe that this provides the most meaningful comparison. In consequence, however, we were unable to adjust for characteristics of the prostate cancers because the controls (comparator group) did not have prostate cancer. We conducted a sensitivity analysis to assess whether the disease characteristics—clinical stage, Gleason score, and prostate-specific antigen level at baseline—were important confounders of association with treatment. In this analysis, the control group was excluded and replaced by a group undergoing NSRP as the reference group. Mean differences were calculated adjusting for the same factors as in the main analysis and then, additionally, adjusting for clinical stage, Gleason score, and prostate-specific antigen level at baseline.

Additional sensitivity analyses were undertaken to assess whether our results were overly influenced by drop out and death, given the generalised estimating equation assumption that missing data were missing at random. To do this, models were refitted to monotone subsets of the data with observations weighted by the inverse of the probability that the observation was actually seen.18 These analyses give greater weight to the outcome measurements of men with higher probability of drop out or death during follow-up, with probability based on the man’s clinical and demographic characteristics and recent quality of life. This greater weight thus accounts for men with similar clinical and demographic characteristics, and quality of life scores, who dropped out or died. Probabilities of observation were estimated through logistic regression for each domain with the dependent variable representing the presence or absence of the domain-specific quality of life score. Independent variables included all time constant covariates from the corresponding treatment association models and the participant’s most recent prior domain-specific quality of life score.

Generalised estimating equation models were complemented by longitudinal trajectory plots of unadjusted quality of life mean scores by domain and treatment groups (figs S5 and S6). Clinical relevance was interpreted as effect sizes, using a threshold of one third of a standard deviation at baseline as the minimal clinically important difference.19 The decision to use one third of a standard deviation for clinical significance was evidence based, as this threshold has been found to indicate probable clinical importance through the development of a widely cited meta-analysis of evidence based effect sizes.20 21 22 Therefore, in comparing men treated for prostate cancer with controls at any point in time and for interpreting change over time for any subgroup (initial treatment or controls), an unadjusted mean score that differed by more than one third of a standard deviation from the baseline score was considered clinically important.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement was first initiated during the design stage of the study through pilot testing. Patients and members of the public served as consultants for questionnaire design, methods of administration, and time required for administration of the questionnaire. As patients and members of the public identified potential problems, the questionnaire was amended to reflect these emerging priorities.

Results

At 15 year follow-up, 502 (30.6%) of the 1642 patients completed baseline questionnaires and 103 (20.8%) of the 495 population based controls completed surveys (table 1). The age range of participants at 15 years was 50 to 85 years (mean 75.9 years). Median follow-up time for participants surveyed at 15 years was 15.2 years. Demographic, clinical and lifestyle characteristics for year 15 participants are presented in table S2. Of the 502 participants surveyed at 15 years, 333 (66%) were initially treated with radical prostatectomy—192 (58%) of these had NSRP and 141 (42%) non-NSRP. Additionally, 43 (9%) of the 502 patients had external beam radiation therapy or high dose rate brachytherapy, 45 (9%) had androgen deprivation therapy, 25 (5%) had low dose rate brachytherapy, and 53 (11%) had active surveillance/watchful waiting. Compared with the patients, a slightly lower proportion of controls were aged 55-59, yet a slightly higher proportion were uninsured, partnered, and living in a non-metropolitan area at baseline and at 15 years (table S2); adjustments for these differences were made in the multivariate analyses. Demographic and clinical characteristics of cases included in multivariate analyses by primary treatment type are displayed in table S3.

Urinary incontinence and bother

Patients treated with low dose rate brachytherapy had the worst urinary bother of all treatment groups at year 1 after diagnosis relative to controls (n=57, adjusted mean difference −20.9, 95% confidence interval −29.1 to −12.8; fig 2 and unadjusted fig S5). This association remitted over the following two years. All other patients, except those on active surveillance/watchful waiting, reported moderate urinary bother relative to controls that, except for NSRP, extended to 15 years after treatment. Patients receiving androgen deprivation therapy had a clinically significant worsening in urinary bother from year 10 to year 15, as shown in their trajectory graph (fig S5) and relative to controls (year 10, n=88: adjusted mean difference −5.3, 95% confidence interval −10.8 to 0.2; year 15, n=45: −15.9, −25.1 to −6.7).

Urinary incontinence at year 1, relative to controls (fig 2) and in absolute terms (fig S5), was worst for men who underwent surgery (radical prostatectomy) regardless of nerve sparing techniques (NSRP, n=486: adjusted mean difference −16.4, 95% confidence interval −18.7 to −14.2; non-NSRP, n=470: −18.3, −20.7 to −16.0; fig 2). In these men, urinary incontinence improved somewhat up to five years but then worsened at 10 and 15 years, such that they remained the worst of all treatment groups at all follow-up times (fig S5). Incontinence worsened at 15 years in the control group, thus reducing somewhat the adjusted mean difference of the groups receiving radical prostatectomy at this time (NSRP, n=192: adjusted mean difference −12.6, 95% confidence interval −16.6 to −8.7 and non-NSRP, n=141: −14.1, −18.2 to −10.0).

Sexual function and bother

Sexual function scores in men treated for localised prostate cancer were lower than in population based controls for all treatment groups at all follow-up time points (fig 2) and in unadjusted absolute terms (fig S5). All treatment groups exceeded the threshold for clinically significant change at 15 years relative to controls (fig 2 and fig S5). The two prostatectomy surgery groups (NRSP; non-NRSP) had the worst sexual function scores relative to controls (fig 2). Adjusted mean differences were respectively −42.1, 95% confidence interval −44.9 to −39.3 and −47.0, −49.6 to −44.4 at year 1, and −19.9, −26.0 to −13.8 and −24.7, −30.8 to −18.7 at year 15. Sexual function scores for each group receiving active treatment generally showed an initial sharp decline from baseline to year 1 (fig S5), and gradual improvement thereafter in comparison with controls (fig 2). Exceptions to this generality were men on active surveillance/watchful waiting who reported an initial decline up to year 2 with a plateau thereafter; men treated with external beam radiation therapy/high dose rate brachytherapy, who reported little recovery in sexual function across the whole 15 year period; and the group receiving low dose rate brachytherapy who, after initial improvement, reported a decline in erectile dysfunction score after year 5 (year 5, n=51: adjusted mean difference −6.7, 95% confidence interval −12.7 to −0.7, year 15, n=25: −20.7, −33.0 to −8.4).

Self-reported unadjusted prevalence of erectile dysfunction (the inability to obtain an erection sufficient for intercourse) was common for all treatment groups 15 years after diagnosis (table 2, 62.3% (active surveillance/watchful waiting, n=33/53) to 83.0% (non-NSRP, n=117/141) compared with controls (n=44/103, 42.7%). At year 15, the highest rates of erectile dysfunction (83.0%, n=117/141) were reported by men who had non-NSRP surgery (table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of men with localised prostate cancer and of control men who reported incontinence, bowel problems, or impotence at 15 years by initial treatment

| Condition and follow-up year | Participant group (type of treatment or control) (No who reported condition/Total No in group (%)) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS/WW | NSRP | Non-NSRP | EBRT/HDR | ADT | LDR | Controls | |

| Urinary incontinence*: | |||||||

| Baseline | 12/200 (6.0) | 3/494 (0.6) | 7/478 (1.5) | 0/170 | 9/227 (4.0) | 0/58 | 5/495 (1.0) |

| 15 years | 6/53 (11.3) | 35/192 (18.2) | 38/141 (27.0) | 6/43 (14.0) | 5/45 (11.1) | 1/25 (4.0) | 0/103 |

| Moderate or severe bowel problems†: | |||||||

| Baseline | 27/200 (13.5) | 18/494 (3.6) | 25/478 (5.2) | 14/170 (8.2) | 21/227 (9.3) | 0/58 | 31/495 (6.3) |

| 15 years | 6/53 (11.3) | 12/192 (6.3) | 4/141 (2.8) | 6/43 (14.0) | 8/45 (17.8) | 0/25 | 2/103 (1.9) |

| Erectile dysfunction‡: | |||||||

| Baseline | 53/200 (26.5) | 76/494 (15.4) | 128/478 (26.8) | 47/170 (27.6) | 87/227 (38.3) | 11/58 (19.0) | 109/495 (22.0) |

| 15 years | 33/53 (62.3) | 144/192 (75.0) | 117/141 (83.0) | 34/43 (79.1) | 34/45 (75.6) | 18/25 (72.0) | 44/103 (42.7) |

ADT=androgen deprivation therapy with or without EBRT; AS/WW=active surveillance/watchful waiting; EBRT/HDR=external beam radiotherapy or high dose rate brachytherapy only (no androgen deprivation therapy); LDR=low dose rate brachytherapy; N/A=not available; non-NSRP=non-nerve sparing radical prostatectomy; NSRP=nerve sparing radical prostatectomy.

Incontinence is defined as needing to wear one or more pad per day owing to weak urinary control and frequent leakage.

Bowel problems are defined as participants’ responses to the question “Overall, how big a problem have your bowel habits been?” being either “moderate” or “big.”

Erectile dysfunction is defined as being unable to obtain an erection sufficient for penetrative intercourse.

Adjusted mean differences for sexual bother showed patterns of change over time similar to those for sexual function but with generally smaller differences relative to controls across all follow-up years.

Bowel problems and bother

Men who received external beam radiation therapy/high dose rate brachytherapy or androgen deprivation therapy had worse bowel bother than controls at all time points (fig 2). These differences exceeded the clinically significant threshold at each follow-up as far as 10 years, but only androgen deprivation therapy remained clinically significant at year 15. Men who underwent androgen deprivation therapy reported the highest unadjusted prevalence (17.8%, n=8/45) of moderate or severe bowel problems at year 15 (table 2). Bowel problems at year 15 were uncommon in 12 (6.3%) of 192 patients surgically treated with NSRP, in four (2.8%) of 141 patients treated with non-NSRP 2.8% (n=4/141), and in two (1.9%) of 103 controls.

General quality of life

Physical wellbeing adjusted mean differences in the group receiving androgen deprivation therapy were lower than in other treatment groups at almost all follow-up times. Participants in other treatment groups showed little difference in physical wellbeing scores relative to controls across the whole follow-up period (fig 3). Men managed with primary active surveillance/watchful waiting reported physical wellbeing similar to that of controls until year 15 of follow-up (n=53, adjusted mean difference −3.7, 95% confidence interval −6.7 to −0.8). Clinically significant thresholds in this group were exceeded only at year 15, while in the androgen deprivation therapy group they were met at years 1 and 2 and exceeded at years 3 and 15 (fig 3).

Mental wellbeing scores were lower for surgery and radiotherapy groups at year 1, 2, and 3, although the adjusted mean differences were small: at three years −1.3, 95% confidence interval −2.3 to −0.4 for NSRP (n=458); −0.8, −1.8 to 0.1 for non-NSRP (n=439); and −1.5, −2.9 to −0.1 for external beam radiation therapy/high dose rate brachytherapy (n=153; fig 3). Mental wellbeing tended to be worse at year 15 in all treatment groups compared with controls, except for the groups receiving active surveillance/watchful waiting and low dose rate brachytherapy. Only the difference from controls for the group receiving androgen deprivation therapy, however, exceeded the threshold for clinically significant change (fig 3).

Sensitivity analyses

Additional adjustment for clinical stage, Gleason score, and prostate-specific antigen level at baseline did not appreciably change the adjusted mean differences, suggesting that these disease severity characteristics were not important confounders in the association with treatment (figs S1 and S2).

Weighting observations by inverse probabilities did not change estimates of treatment association at the follow-up times (fig S3 and S4). In addition, when cohort drop out was examined descriptively (fig S7), we generally found worse self-reported quality of life in previous follow-up rounds in those who had dropped out.

Discussion

We examined men’s self-reported quality of life 15 years after a diagnosis of localised prostate cancer and found important differences in several quality of life domains in different treatment groups in comparison with population based controls. Persisting problems with erectile dysfunction were common in all treatment groups (range 62.3% (active surveillance/watchful waiting, n=33/53) to 83.0% (non-NSRP, n=117/141) for treatment groups; 42.7% (n=44/103) in controls).Poor sexual outcomes were most pronounced in those who initially had radical prostatectomy, regardless of nerve sparing techniques, and were most severe during the early years of follow-up, a result seen in other studies.23 24 25 Most treatment groups had improved sexual functioning across the 15 years, except the group receiving low dose rate brachytherapy, who reported deterioration in scores from year 10 to year 15 of follow-up. As far as we know, this is a new longitudinal finding, though similar findings have been reported for a median follow-up of five years.26

Men who had external beam radiation therapy/high dose rate brachytherapy or androgen deprivation therapy as primary treatment reported more bowel problems, and this persisted in the group receiving androgen deprivation therapy. Self-reported urinary incontinence was particularly prevalent and persistent for men who underwent radical prostatectomy, regardless of whether nerve sparing techniques were used, and an increase in incontinence was also reported in the groups receiving external beam radiation therapy/high dose rate brachytherapy and androgen deprivation therapy at 15 years.

Physical and mental wellbeing tended to fall in all groups between 10 and 15 years after diagnosis. The most severe late adverse associations in the active surveillance/watchful waiting group were with physical wellbeing and, in the androgen deprivation therapy group, with mental wellbeing.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study had two major strengths; it is a population wide study evaluating 15 year quality of life outcomes in men with localised prostate cancer across a range of different common treatments and includes a population based control group of men without prostate cancer for comparison. A major advantage of using a population based control group is that it allows men to quantify their expected decline in quality of life resulting from the combination of their cancer and its treatment choice, while also allowing them to indirectly compare quality of life difference between treatments (using the common control referent group). A few limitations need to be considered, however, when interpreting our results.

Firstly, we considered it important to use men without prostate cancer as controls in order to provide the most meaningful comparator for patients with prostate cancer and clinicians, and therefore we were unable to adjust for disease severity in the multivariate analysis (fig 2 and fig 3). Nevertheless, we believe that this choice of reference group had little association with our findings as a sensitivity analysis indicated that clinical stage, Gleason score, and prostate-specific antigen level at baseline did not appreciably confound the association with treatments (figs S1 and S2).

Secondly, prospective cohort studies are vulnerable to bias arising from participant attrition and death over the study period; this study is no exception. Reassuringly, however, sensitivity analyses using inverse probability weighting had very little association with our original estimates. This lack of association suggests that our estimates are robust to missing value bias, where the probability of an observation being missing depends on the surrounding responses or covariates included in the model (that is, data missing at random).

Thirdly, since the design of the PCOS baseline questionnaire preceded validation of EPIC, we were unable to directly assess quality of life domains exclusive to EPIC, such as urinary voiding and storage dysfunction. Previous studies, however, have found that radical prostatectomy reduces these problems, and this appears to be consistent with our results, which showed improvement in urinary bother for patients receiving radical prostatectomy relative to controls.25 27

Fourthly, although we adjusted for a wide range of potential confounders to account for differences in patient characteristics between groups, as with all non-randomized studies, the possibility of residual confounding cannot be ruled out.

Fifthly, our study categorized treatments by primary treatment groups and did not account for subsequent treatment provided during the study period due to disease progression or recurrence, as we did not have access to such data. Additionally, advances in treatment techniques, and surgical and radiotherapeutic technology (eg, robotic surgery and stereotactic radiotherapy) have been made during the follow-up period, as have protocols for managing men receiving active surveillance and with an earlier diagnosis. Although the potential benefit of these modern technological advances is not captured within our cohort, the long term quality of life benefits due to these advances have also not been empirically proved by more recent trials and studies. For radical prostatectomy, a recent randomised controlled trial comparing robot assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy with open radical retropubic prostatectomy found similar self-reported functional outcomes between the two techniques at 24 months after surgery and suggested that the benefits of robotic surgery could relate more to its minimally invasive approach than to self-reported improvement in quality of life for patients.28 The treatment and management approaches presented in our study still represent the most common treatments for prostate cancer albeit with advanced technology, experience, and emerging evidence for outcome based treatment selection.6 7

Sixthly, we are unable to comment on 15 year cause specific survival rates within our cohort as these data were available only up to December 2017 for our death linkage. Nonetheless, while it is important for men to consider survival outcomes together with quality of life outcomes in order to make informed decisions about treatment, previous studies have noted that patients with clinically localised prostate cancer have good overall and cancer specific long term survival regardless of the treatment received.29 30

Finally, partner/carer perspectives are important to overall quality of life, and this perspective was collected at the 15 year follow-up. However, they lie outside the scope of this paper and will be reported separately.

Comparison with other studies

Reports on the long term quality of life outcomes in men with prostate cancer receiving various treatments have only just begun to emerge. To date, few studies have reported 10 year quality of life outcomes in this group and only one study has reported 15 year comparative outcomes between only two treatment groups.8 25 31 32 33 The Cancer of the Prostate Strategic Urologic Research Endeavor (CaPSURE),31 Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group Study Number 4 (SPCG-4)25, QALIPRO,32 and Ralph et al33 studies reported at least 10 year quality of life follow-up in men with prostate cancer for several treatment modalities.

CaPSURE found a persistent long term adverse association between the use of external beam radiation therapy and bowel functioning, which increased over time, but Resnick et al found these associations attenuated in comparison with those who underwent surgery.8 31 QALIPRO assessed quality of life in patients with control comparators, finding that men treated with radiotherapy consistently reported worse bowel functioning than disease-free comparators.32 Regardless of treatment type, all men reported some level of bowel bother during short term follow-up in our cohort, with these adverse outcomes being more severe in the groups receiving androgen deprivation therapy and external beam radiation therapy/high dose rate brachytherapy. Those men who underwent androgen deprivation therapy reported the most persistent problems of bowel bother. These results are consistent with findings from studies evaluating shorter term quality of life in patients with localised prostate cancer.6 34

A patients’ preferences survey conducted with PCOS participants three years after diagnosis examined trade-offs between symptoms and survival using a discrete choice experiment.35 This survey found the least tolerable side effect was severe urinary leakage, often associated with urinary bother, closely followed by severe bowel symptoms.35 In the PCOS cohort, self-reported urinary incontinence improved for most treatment groups over the first three years after diagnosis and then plateaued. This trend was evident particularly for those who underwent surgery, with reported incontinence remaining significantly higher and with little improvement beyond three years of follow-up, a finding that was also apparent in the SPCG-4 trial.25 Interestingly, the groups receiving external beam radiation therapy/high dose rate brachytherapy and androgen deprivation therapy reported urinary incontinence comparable to that of controls up to three years, but at 10 and 15 years, both groups reported worsening urinary bother relative to controls. Over a 10 year period, Ralph et al found the use of androgen deprivation therapy led to more adverse long term quality of life outcomes.33 Our study similarly found that men receiving androgen deprivation therapy (with or without external beam radiation therapy) reported adverse outcomes for almost all quality of life domains at the 15 year follow-up. It is plausible that a proportion of men receiving androgen deprivation therapy could also have received subsequent external beam radiation therapy, which could account for this increase in bowel bother and urinary incontinence over time.

For sexual dysfunction, Resnick et al found that initially, men who underwent surgery reported more profound dysfunction than men who were treated with external beam radiation therapy, and, similarly, those treated with surgery in the SPCG-4 trial reported adverse sexual dysfunction.8 25 Sexual function continued to be a prominent concern for both treatment types, but both groups gradually reported lower sexual bother scores (less bothersome) as time passed. Our study found a similar trend in gradual reporting of less bother with sexual dysfunction, even with sustained prevalence of sexual dysfunction across treatment groups. The disconnect between reported bother and functional outcomes could be related to perceived expectations of the ageing process for survivors of localised prostate cancer8 27—namely, that impaired sexual function is expected and accepted as a result of ageing, and therefore causes less bother. When evaluating unadjusted reports of erectile dysfunction, our study found that 44 (42.7%) of the 103 age matched controls reported erectile dysfunction (unable to obtain an erection sufficient enough for penetrative intercourse) at the 15 year follow-up, still considerably less than the corresponding proportions for men with localised prostate cancer (62.3% to 83.0%). Thus although a reduction in sexual function due to the natural ageing process is apparent in healthy men, this decline in function is greater in men treated for localised prostate cancer.36

Another possible explanation for the normalisation of sexual dysfunction is termed the response shift, whereby an individual’s internal standards undergo a shift concurrently with changes in their health status.37 Hanly et al explored psychosexual adjustment to prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment and found that men strive to accept treatment induced limitations in their life and integrate their “new normal” self after treatment with their changing sexual functioning.38 This notion is further supported by the PCOS preference survey, which examined the quality of life trade-offs men were willing to make for a longer life: men reported that erectile dysfunction and loss of libido were the most acceptable side effects of treatment in this context.35

Clinical implications

Given the relatively high 15 year survival rate for men with localised prostate cancer,3 and the comparable mortality rates across treatment groups for men with low risk disease,29 the longitudinal quality of life changes discussed in this study are becoming vitally important to consider. Men diagnosed with localised prostate cancer have previously expressed a need for more involvement in treatment decision making, while also finding the many treatment options confusing or distressing, resulting in uncertainty over the best choice for them.39 40 41

Although treatment decisions are ultimately based on a combination of clinical factors and patient preferences,42 the overarching clinical implication of this study was to provide longitudinal evidence on patient reported outcomes associated with common approaches to prostate cancer to aid treatment discussions. Our findings describe the use of patient reported outcomes for men who have experienced many years of life after a diagnosis of localised prostate cancer. Clinicians should be encouraged to use this evidence to discuss and assist with decision making about long term survivorship after initial treatment for prostate cancer.

Conclusions

This paper adds to the limited evidence and understanding of the long term quality of life for men with localised prostate cancer. Each treatment approach was associated with some adverse effects on quality of life, in absolute terms and in comparison with age matched controls. The most apparent and persisting adverse association was a reduction in sexual function, although this caused limited bother to men. In contrast, while urinary incontinence was less prevalent, it was a greater cause of bother. Further research exploring individual experiences and adjustment to changes in the long term is needed to identify where support and information gaps lie and what measures are likely to fill them. Clinicians and patients should be fully informed of these long term quality of life outcomes when making treatment decisions and understand possible long term consequences of the various management approaches.

What is already known on this topic

Survival after a diagnosis of localised prostate cancer has increased over the past two decades

Few studies have reported long term (≥10 years), treatment related quality of life outcomes associated with these survival gains

Unlike previous studies this prospective cohort study compares 15 year outcomes with those for men without a diagnosis of prostate cancer who were followed up in parallel

What this study adds

Each treatment approach was associated with reports of some adverse effects on long term quality of life, and survivors of localised prostate cancer continued to report chronic side effects and associated functional problems (eg, incontinence, bowel, or sexual dysfunction) up to 15 years after diagnosis

Reduced sexual function was common in all management groups in comparison with age matched controls and was especially prevalent in men who had a radical prostatectomy

This study strengthens the evidence for informed decision making about the early management of localised prostate cancer

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the New South Wales prostate cancer care and outcomes study advisory group and the professional reference group for their contributions; the New South Wales cancer registry for their assistance in the recruitment of study participants; and John Rodgers and Con Casey for their encouragement to undertake this study and methodological and other advice.

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Web appendix: Supplementary appendix

Contributors: CGM designed and managed the 15 year follow-up of the study participants. She had full access to all the data, contributed to the analysis, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. CGM takes responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the data and the analysis and is the guarantor. SE had full access to the data, contributed to its analysis and interpretation, and commented on drafts of the manuscript. DPS and BKA co-conceived PCOS and its 15 year follow-up, provided statistical advice, contributed to data interpretation, critically revised drafts of the manuscript, and oversaw the conduct of the study. MTK provided statistical advice, data interpretation, and commented on drafts of the manuscript. IJ, HW, and MB provided clinical and methodological advice and commented on drafts of the manuscript. All authors declare that they accept full responsibility for the conduct of the study and the decision to publish. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: Cancer Council New South Wales provided all the infrastructure required by PCOS and its follow-up, paid the salaries of BKA and DP during the conduct of PCOS, and the salaries of CGM, SE, and DPS during the period of conduct, analysis and reporting on this 15 year follow-up. This research was also partially funded by grants from the Australian Commonwealth Department of Veterans Affairs, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, and the Cancer Institute New South Wales (grant number 15/CDF/1-10). The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of data; the writing of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: financial support from Cancer Institute New South Wales for partial funding for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have been interested in the submitted work in the previous three years. HW has received a speaker honorarium from Abbvie, Janssen, Astellas, Mundipharma, AstraZeneca, and Boston Scientific. BKA chairs the Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia’s Research Advisory Committee and is, ex officio, a member of its national board. The foundation meets his travel, accommodation and meal costs when attending official foundation meetings; no other remuneration is provided. All other authors declare no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the human research ethics committee of the Cancer Council New South Wales (reference No 298). Informed consent was obtained for all participants at each stage of follow-up.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

The manuscript’s guarantor (CGM) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any differences from the study as originally planned have been explained.

Dissemination to participants and related patient and public communities: A dissemination strategy for this research has been co-designed with consumer input. Upon publication, Cancer Council New South Wales intends to provide a media release outlining the main findings of this study, targeted at leading health journalists in Australia and industry publications. Additionally, Cancer Council New South Wales endeavours to make these findings interpretable for all audiences and thus a consumer focused article on the key study findings will be published on Cancer Council New South Wales’s blog (via social media channels and e-newsletters to Cancer Council staff, supporters, and volunteers) to coincide with the media release. This study will also be shared with research collectives and stakeholder organisations related to patients with prostate cancer and survivors. The findings from this study will be directly communicated with study participants via an e-newsletter, which will include a summary of this study’s findings and references to other ongoing research projects in prostate cancer conducted by Cancer Council New South Wales. Finally, these results have been presented at both national and international conferences, with the expectation that further presentations will occur.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries [correction in: CA Cancer J Clin 2020;70:313]. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:394-424. 10.3322/caac.21492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rawla P. Epidemiology of prostate cancer. World J Oncol 2019;10:63-89. 10.14740/wjon1191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. American Cancer Society Cancer facts & figures 2019. American Cancer Society, 2019. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2019/cancer-facts-and-figures-2019.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zeliadt SB, Moinpour CM, Blough DK, et al. Preliminary treatment considerations among men with newly diagnosed prostate cancer. Am J Manag Care 2010;16:e121-30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Song L, Chen RC, Bensen JT, et al. Who makes the decision regarding the treatment of clinically localized prostate cancer--the patient or physician?: results from a population-based study. Cancer 2013;119:421-8. 10.1002/cncr.27738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lardas M, Liew M, van den Bergh RC, et al. Quality of life outcomes after primary treatment for clinically localised prostate cancer: a systematic review. Eur Urol 2017;72:869-85. 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.06.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ávila M, Patel L, López S, et al. Patient-reported outcomes after treatment for clinically localized prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat Rev 2018;66:23-44. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2018.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Resnick MJ, Koyama T, Fan KH, et al. Long-term functional outcomes after treatment for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2013;368:436-45. 10.1056/NEJMoa1209978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Smith DP, King MT, Egger S, et al. Quality of life three years after diagnosis of localised prostate cancer: population based cohort study. BMJ 2009;339:b4817. 10.1136/bmj.b4817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Egger SJ, Calopedos RJ, O’Connell DL, Chambers SK, Woo HH, Smith DP. Long-term psychological and quality-of-life effects of active surveillance and watchful waiting after diagnosis of low-risk localised prostate cancer. Eur Urol 2018;73:859-67. 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mazariego CG, Juraskova I, Campbell R, Smith DP. Long-term unmet supportive care needs of prostate cancer survivors: 15-year follow-up from the NSW Prostate Cancer Care and Outcomes Study. Support Care Cancer 2020. 10.1007/s00520-020-05389-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Glover J, Tennant S. Remote areas statistical geography in Australia: notes on the accessibility/remoteness index for Australia (ARIA + version). Public Health Information Development Unit, University of Adelaide, 2002. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.502.1580&rep=rep1&type=pdf [Google Scholar]

- 13. Litwin MS, Hays RD, Fink A, Ganz PA, Leake B, Brook RH. The UCLA Prostate Cancer Index: development, reliability, and validity of a health-related quality of life measure. Med Care 1998;36:1002-12. 10.1097/00005650-199807000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wei JT, Dunn RL, Litwin MS, Sandler HM, Sanda MG. Development and validation of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology 2000;56:899-905. 10.1016/S0090-4295(00)00858-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Szymanski KM, Wei JT, Dunn RL, Sanda MG. Development and validation of an abbreviated version of the expanded prostate cancer index composite instrument for measuring health-related quality of life among prostate cancer survivors. Urology 2010;76:1245-50. 10.1016/j.urology.2010.01.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SDA. A 12-item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996;34:220-33. 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH. Generalized estimating equations (GEE). In: Applied longitudinal data analysis: Wiley series in probability and statistics. John Wiley, 2004: 291-321. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dufouil C, Brayne C, Clayton D. Analysis of longitudinal studies with death and drop-out: a case study. Stat Med 2004;23:2215-26. 10.1002/sim.1821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Skolarus TA, Dunn RL, Sanda MG, et al. PROSTQA Consortium Minimally important difference for the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite Short Form. Urology 2015;85:101-5. 10.1016/j.urology.2014.08.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. King MT, Stockler MR, Cella DF, et al. Meta-analysis provides evidence-based effect sizes for a cancer-specific quality-of-life questionnaire, the FACT-G. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:270-81. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cocks K, King MT, Velikova G, et al. EBIG collaborative group Evidence-based guidelines for interpreting change scores for the European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30. Eur J Cancer 2012;48:1713-21. 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.02.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cocks K, King MT, Velikova G, Martyn St-James M, Fayers PM, Brown JM, EBIG collaborative group Evidence-based guidelines for determination of sample size and interpretation of the European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:89-96. 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.0107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Crook JM, Gomez-Iturriaga A, Wallace K, et al. Comparison of health-related quality of life 5 years after SPIRIT: Surgical Prostatectomy Versus Interstitial Radiation Intervention Trial. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:362-8. 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.7305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Donovan JL, Hamdy FC, Lane JA, et al. ProtecT Study Group Patient reported outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1425-37. 10.1056/NEJMoa1606221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Johansson E, Steineck G, Holmberg L, et al. SPCG-4 Investigators Long-term quality-of-life outcomes after radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting: the Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group-4 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:891-9. 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70162-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Buergy D, Schneiberg V, Schaefer J, et al. Quality of life after low-dose rate brachytherapy for prostate carcinoma - long-term results and literature review on QLQ-C30 and QLQ-PR25 results in published brachytherapy series. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2018;16:21. 10.1186/s12955-018-0844-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Michalski J, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1250-61. 10.1056/NEJMoa074311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Coughlin GD, Yaxley JW, Chambers SK, et al. Robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy versus open radical retropubic prostatectomy: 24-month outcomes from a randomised controlled study. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:1051-60. 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30357-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hamdy FC, Donovan JL, Lane JA, et al. ProtecT Study Group 10-year outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1415-24. 10.1056/NEJMoa1606220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Thomsen FB, Røder MA, Jakobsen H, et al. Active surveillance versus radical prostatectomy in favorable-risk localized prostate cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2019;17:e814-21. 10.1016/j.clgc.2019.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Punnen S, Cowan JE, Chan JM, Carroll PR, Cooperberg MR. Long-term health-related quality of life after primary treatment for localized prostate cancer: results from the CaPSURE registry. Eur Urol 2015;68:600-8. 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.08.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kerleau C, Guizard AV, Daubisse-Marliac L, et al. French Network of Cancer Registries (FRANCIM) Long-term quality of life among localised prostate cancer survivors: QALIPRO population-based study. Eur J Cancer 2016;63:143-53. 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.05.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ralph N, Ng SK, Zajdlewicz L, et al. Ten-year quality of life outcomes in men with prostate cancer. Psychooncology 2020;29:444-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hoffman KE, Penson DF, Zhao Z, et al. Patient-reported outcomes through 5 years for active surveillance, surgery, brachytherapy, or external beam radiation with or without androgen deprivation therapy for localized prostate cancer. JAMA 2020;323:149-63. 10.1001/jama.2019.20675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. King MT, Viney R, Smith DP, et al. Survival gains needed to offset persistent adverse treatment effects in localised prostate cancer. Br J Cancer 2012;106:638-45. 10.1038/bjc.2011.552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Litwin MS. Health related quality of life in older men without prostate cancer. J Urol 1999;161:1180-4. 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)61624-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schwartz CE, Andresen EM, Nosek MA, Krahn GL, RRTC Expert Panel on Health Status Measurement Response shift theory: important implications for measuring quality of life in people with disability. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007;88:529-36. 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.12.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hanly N, Mireskandari S, Juraskova I. The struggle towards ‘the new normal’: a qualitative insight into psychosexual adjustment to prostate cancer. BMC Urol 2014;14:56. 10.1186/1471-2490-14-56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Steginga SK, Occhipinti S, Gardiner RA, Yaxley J, Heathcote P. Prospective study of men’s psychological and decision-related adjustment after treatment for localized prostate cancer. Urology 2004;63:751-6. 10.1016/j.urology.2003.11.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. O’Callaghan C, Dryden T, Hyatt A, et al. ‘What is this active surveillance thing?’ Men’s and partners’ reactions to treatment decision making for prostate cancer when active surveillance is the recommended treatment option. Psychooncology 2014;23:1391-8. 10.1002/pon.3576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hyatt A, O’Callaghan C, Dryden T, et al. Australian men with low risk prostate cancer and their partners’ experience of treatment decision-making and active surveillance. BJU Int 2013;112:54-65.23146082 [Google Scholar]

- 42. Violette PD, Agoritsas T, Alexander P, et al. Decision aids for localized prostate cancer treatment choice: systematic review and meta-analysis. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:239-51. 10.3322/caac.21272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Web appendix: Supplementary appendix