Abstract

Objectives

Nursing homes became epicenters of COVID-19 in the spring of 2020. Due to the substantial case fatality rates within congregate settings, federal agencies recommended restrictions to family visits. Six months into the COVID-19 pandemic, these largely remain in place. The objective of this study was to generate consensus guidance statements focusing on essential family caregivers and visitors.

Design

A modified 2-step Delphi process was used to generate consensus statements.

Setting and Participants

The Delphi panel consisted of 21 US and Canadian post-acute and long-term care experts in clinical medicine, administration, and patient care advocacy.

Methods

State and federal reopening statements were collected in June 2020 and the panel voted on these using a 3-point Likert scale with consensus defined as ≥80% of panel members voting “Agree.” The consensus statements then informed development of the visitor guidance statements.

Results

The Delphi process yielded 77 consensus statements. Regarding visitor guidance, the panel made 5 strong recommendations: (1) maintain strong infection prevention and control precautions, (2) facilitate indoor and outdoor visits, (3) allow limited physical contact with appropriate precautions, (4) assess individual residents' care preferences and level of risk tolerance, and (5) dedicate an essential caregiver and extend the definition of compassionate care visits to include care that promotes psychosocial well-being of residents.

Conclusions and Implications

The COVID-19 pandemic has seen substantial regulatory changes without strong consideration of the impact on residents. In the absence of timely and rigorous research, the involvement of clinicians and patient care advocates is important to help create the balance between individual resident preferences and the health of the collective. The results of this evidence-based Delphi process will help guide policy decisions as well as inform future research.

Keywords: COVID-19, nursing homes, visitors, public policy

Nursing homes are the epicenters of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in the United States, with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) reporting more than 286,000 confirmed or suspected COVID-19 resident cases and more than 45,000 COVID-19 resident deaths as of August 2, 2020.1, 2, 3 Nursing home residents are at increased risk of contracting severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)—the causative infectious agent of COVID-19—as a result of congregate living, difficulty complying with physical distancing and hand hygiene, shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE) for staff, and exposure to asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic health care workers, who may themselves be at elevated risk due to age, comorbidities, and other associated health disparities.4, 5, 6, 7 Furthermore, nursing home residents are at increased risk of COVID-19 morbidity and mortality because of their advanced age, frailty, immunosenescence, and multimorbidity, resulting in early case fatality rates of 33.7%.8

In response to an intensifying COVID-19 crisis in American nursing homes, in mid-March CMS implemented new regulations with the goal of preventing the introduction of COVID-19 into facilities across the country. These measures resulted in the immediate restriction of visitors, volunteers and nonessential personnel from entering nursing homes, as well as the cancellation of group activities and communal dining.9 , 10 The ban on visitors included family and other non-staff caregivers who provide direct, complex, intense and usually unpaid care for many nursing home residents.11, 12, 13, 14 Although the regulations were deemed essential to COVID-19 containment, the continuation of this lockdown for a prolonged time has resulted in potentially irreversible physical, cognitive, psychological and functional decline.15, 16, 17, 18, 19 Restrictions were implemented without resident and family input leading to ethical concerns regarding the abrogation of self-determination and clinical concerns that ongoing restrictions have begun to outweigh any potential benefits.15 , 20, 21, 22

CMS released phased reopening guidelines on May 18, 2020, instructing nursing homes to reopen only when the facility had no new COVID-19 cases for a 28 day period and no shortages in PPE, staffing, or testing capacity.23 , 24 Three months after release of these guidelines, many facilities are still far from meeting these criteria.11 Residents, families, clinicians, and advocates are calling for a more immediately actionable, sustainable, balanced, nuanced, and resident-centered approach to reopening nursing homes that respects residents' rights to autonomy, informed risk taking, access to essential family caregivers, and other face-to-face interactions. A group of experts convened to develop a set of evidence-informed guidance statements to welcome back visitors and essential family caregivers to America's nursing homes.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

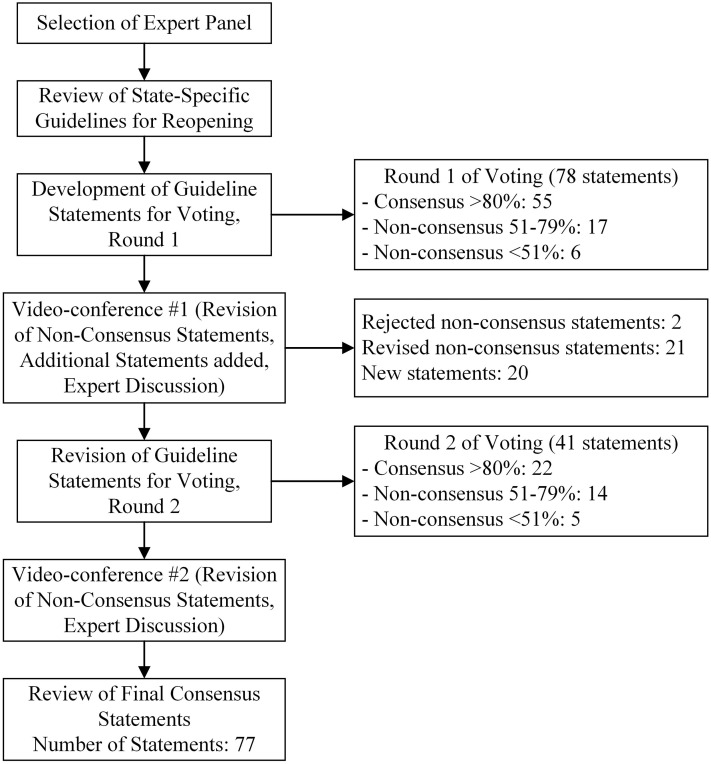

A 2-step, accelerated Delphi process was conducted among experts in post-acute and long-term care medicine, administration, and patient care advocacy. The modified Delphi process provided structured communication utilizing e-mail and survey technology, iterative feedback, and informed expert discussions to guide the development of novel, resident-centered guidance statements.25 , 26 Due to the evolving nature of COVID-19 and urgency to inform public policymakers and advocates, the modified Delphi process was conducted in a 30-day period in July 2020. The two-round modified Delphi process chosen for this project used a series of questionnaires to collect anonymous responses to statements derived from state and federal reopening guidelines (see Figure 1 ).

Fig. 1.

A flow diagram of the 2-step modified Delphi process. Round 1 started with 78 statements and round 2 started with 41 statements with 77 statements ultimately reaching consensus, defined as >80% of panel members who voted “Agree.”

Delphi Panel Selection and Composition

Active post-acute and long-term care clinicians, administrators, and patient care advocates were selected through e-mail communications in June 2020 from an initial pool of candidates who had worked on a similar project. After an initial review of the panel composition, a decision was made to invite additional selected members to join in an effort to expand minority representation. The final Delphi panel of experts was composed of 21 members. Most of our expert panel was older than 50 (72%), female (67%), and white (71%). Our panel included 2 (10%) African-American panelists and 4 (19%) Asian panelists. Furthermore, our panelists were not all current clinicians, since 4 (19%) members were administrators and 6 (29%) members primarily were patient care advocates. Representative of the wider post-acute and long-term care industry, only 5 (24%) members were employed by an academic medical center. Of the 15 panel members who had direct clinical experience, 11 (73%) had more than 20 years of experience.

Generation of Guidance Statements

We collected published reopening guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), CMS and 17 states in June 2020 and generated the initial round of statements for the expert panel to consider. Individuals on the panel added and edited certain statements for consistency, accuracy, and wording, with a focus on delivering a resident-centered guidance document. We organized the statements into broad categories: definitions, criteria for entrance into phase 3 as defined by CMS,23 universal source control, screening, testing and surveillance, contact tracing, cohorting and isolation, visitor guidelines, healthcare personnel, communal dining, group activities, non–medically necessary trips outside the nursing home, outbreak investigation and regression to earlier phases, immunity, and special resident populations and scenarios (see Supplementrary Material 1 for complete list).

Data Collection and Analysis

In round one, participants voted on the statements, using a three-point Likert scale (“Agree,” “Neutral,” or “Disagree”) with an option to offer “Absent” due to a lack of perceived expertise. Consensus was defined as ≥80% of participants voting “Agree” (green statements). We grouped non-consensus statements into ≤50% (red statements) and 51% to 79% (yellow statements) for purposes of facilitating discussion after each round. The whole panel discussed statements not reaching consensus in a videoconference, starting with statements that had the highest degree of uncertainty (red statements). In preparation for round 2 of voting, participants also suggested additional statements for consideration. Following the second round of voting, a final videoconference discussion collected comments on the non-consensus statements to help inform the final document. We report the final count of consensus and non-consensus statements. Descriptive statistics and tables illuminated differences in responses among the expert panel.

Development of Visitor Guidance

Although the present reopening statements cover a wide range of topics, we focused on the statements specific to visitors in order to communicate immediately actionable recommendations to policymakers. Those statements reaching consensus shaped our visitor guidance document. We edited the final guidance statements for clarity, aiming to capture the consensus of the Delphi panel.

Results

Delphi Voting Results

Round one of voting started with 78 statements during which 21 panelists voted (100% response rate) to reach consensus on 55 statements (71% consensus rate). The videoconference discussion of non-consensus statements rejected 2 statements and edited 21 statements for further voting. In Round 2, the panel voted on 21 revised statements and 20 new statements (19 members of the panel, 90% response rate) resulting in 22 consensus statements (54% consensus rate). To assure fidelity of the Delphi process, all questions required that a minimum of 75% of panelists participate. On average, the questions had an average of 19 members cast a vote with the lowest number being 16 (76%) and the highest being 21 (100%). In Round 2, 11 of the 21 revised statements from Round 1 reached consensus, representing a non-consensus to consensus conversion of 52%. Complete results are included in the supplemental information (see Supplementray Materials 2 and 3).

Persistent Non-Consensus Statements

Due to the evolving science regarding COVID-19, the panel was not able to reach consensus on all statements. The panel demonstrated considerable disagreement on certain aspects of the following topics (see Table 1 ): testing of asymptomatic staff and residents, surveillance testing, visitor guidance, immunity from prior COVID-19 infection and associated risk of infecting others. The panel generally agreed on the need for testing of asymptomatic staff (79%); but the panel discussion reflected the importance of understanding community prevalence as a key factor in deciding to test asymptomatic individuals. While the panel mostly agreed (68%) that residents should be allowed to opt out of testing for sole purposes of surveillance, fewer agreed that testing of asymptomatic residents should not be done (53%). Most members agreed that an asymptomatic resident who has recovered from the disease need not be tested within 8 weeks from the onset of symptoms (74%) but fewer agreed to extend that to 90 days (58%) or to never test again (11%). This general uncertainty about the time was again reflected when the panel commented on whether an asymptomatic COVID-19 resident who has recovered could be contagious 8 weeks after recovery (65% agreement that they are not contagious), or after 90 days (53% agreement that they are not contagious). A minority of the panel members (35%) agreed that a recovered COVID-19 who remains asymptomatic is not contagious.

Table 1.

Persistent Non-Consensus Statements

| Statement | Agree (n, %) | Neutral (n) | Disagree (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definitions | |||

| A nursing home (NH)-onset Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection definition does not include an asymptomatic COVID-19 resident who has recovered from the disease but tests positive within 90 days of onset of symptoms. | 13 (68) | 5 | 1 |

| Criteria for Entrance into Phase 3 | |||

| In order for a nursing home to proceed with phased reopening, there should be no new NH-onset cases for 28 days. | 14 (74) | 1 | 4 |

| Testing and Surveillance | |||

| Testing a proportion of randomly selected asymptomatic HCP (staff) who have not previously tested positive should be done for surveillance efforts. The frequency and sample size of staff should be guided by size of the nursing home and level of local community spread. | 15 (79) | 1 | 3 |

| In facilities without any positive COVID-19 cases, test 100% of asymptomatic HCP (staff) who have previously not tested positive weekly for 4 weeks; if no new positives may test 25% of asymptomatic HCP (staff) every 7 days such that 100% of the nursing home staff are tested each month. | 10 (53) | 3 | 6 |

| Testing a proportion of randomly selected asymptomatic residents who have not previously tested positive should not be done for surveillance efforts. Instead, residents who are asymptomatic should only be tested during outbreak investigations of close contacts of a known COVID-19 positive resident or staff member. | 10 (53) | 4 | 5 |

| Residents who are asymptomatic should be allowed to opt out of testing for sole purposes of surveillance. This statement would not be applicable for contact tracing with a known exposure to a COVID-19 resident or staff member. | 13 (68) | 2 | 4 |

| An asymptomatic resident who has previously tested positive for COVID-19 and recovered does not need to be tested again within an 8-week window of prior onset of symptoms. | 14 (74) | 2 | 3 |

| An asymptomatic resident who has previously tested positive for COVID-19 and recovered does not need to be tested again within a 90-day window of prior onset of symptoms. | 11 (58) | 5 | 3 |

| An asymptomatic resident who has previously tested positive for COVID-19 and recovered does not need to be tested again. | 2 (11) | 3 | 11 |

| Outbreak Investigation and Phase Regression | |||

| A new or returning asymptomatic nursing home resident without a prior diagnosis of COVID-19 and who has remained under isolation in a private room for 14 days since admission tests positive during nursing home testing of asymptomatic residents. Not during an outbreak investigation and there has been no exposure to a COVID-19 positive resident or staff. In this situation, re-test the resident only. If subsequently negative and no further suspicion of COVID-19 in the building, this scenario would not warrant nursing home-wide testing or phase regression. | 14 (74) | 1 | 4 |

| Visitor Guidelines | |||

| A negative COVID-19 test is not a requirement prior to visiting a nursing home. | 14 (70) | 1 | 5 |

| Visitors who wish to visit a nursing home resident who is actively symptomatic but for whom COVID-19 testing is pending or unknown should have an informed consent discussion with nursing leadership, demonstrate appropriate donning/doffing of personal protective equipment (PPE) and agree to wear appropriate PPE during the visit. | 8 (47) | 1 | 8 |

| Health Care Personnel | |||

| Allow entry of all essential and nonessential healthcare personnel, contractors, and vendors with appropriate screening, physical distancing, hand hygiene, and face coverings. They would be subject to the same testing and surveillance requirements as the rest of the HCP (staff) cohort. Visitors including non-employed caregivers and surrogate decision makers would be subject to the visitor guidelines. | 14 (74) | 0 | 5 |

| The nursing home should consider a designated care giver (or dedicated support person, surrogate decision-maker) an essential member of the health care team who would not be subject to visitor guidelines if resources (PPE, training, monitoring) are available at the time and the person is directly engaged in compassionate care to alleviate a residents psychosocial stress as a result of isolation. | 15 (79) | 0 | 4 |

| Non–Medically Necessary Trips Outside the Nursing Home | |||

| A resident who engages in a visit with family or friends beyond the nursing home grounds, remains outside, and the visit does not involve close contact with COVID+ individuals or symptomatic individuals would not be subject to isolation upon re-entry to the nursing home. | 3 (17) | 4 | 11 |

| After a resident returns from an outside trip beyond the nursing home grounds and prior to the resident resuming activities within a shared space, the resident should be bathed according to accepted practice with soap and have the clothes they were wearing laundered in a standard fashion. | 9 (47) | 5 | 5 |

| Immunity | |||

| A currently asymptomatic individual who has recovered from COVID-19 and is post 8 weeks from onset of symptoms is not considered infectious and should not be tested. If tested and the test returns positive, as long as the resident remains asymptomatic, it would not be considered a reinfection and the resident is not contagious. | 11 (65) | 2 | 4 |

| A currently asymptomatic individual who has recovered from COVID-19 and is post 90 days from onset of symptoms is not considered infectious and should not be tested. If tested and the test returns positive, as long as the resident remains asymptomatic, it would not be considered a reinfection and the resident is not contagious. | 9 (53) | 1 | 7 |

| A currently asymptomatic individual who has recovered from COVID-19 is not considered infectious and should not be tested. If tested and the test returns positive, as long as the resident remains asymptomatic, it would not be considered a reinfection and the resident is not contagious. | 6 (35) | 4 | 7 |

| Antibody testing can be a surrogate marker of individual immunity but does not currently inform clinical practice; recovery from prior infection does. | 11 (69) | 0 | 5 |

Color scheme represents level of consensus among panel. Yellow represents statements in which 51%–79% of members voted “Agree” and red represents statements in which <50% of members voted “Agree.”

Generation of the Visitor Guidance Statements

The Delphi process reached consensus on 12 of 14 statements related to visitors. These statements were then merged and expanded into guidance statements (see Table 2 ) discussing criteria to welcome back visitors and the factors involved in its implementation, including: screening procedures, visit logistics, infection prevention strategies, location of visit, an essential family caregiver, and issues surrounding visiting symptomatic residents and those at the end-of-life.

Table 2.

Suggested Visitor Guidance as Developed Through a Delphi Consensus Process

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Discussion

Reopening America's nursing homes to visitors is of critical importance as many residents continue to sustain severe and potentially irreversible consequences from lack of human contact, especially with family caregivers. The CDC nursing home guidelines published as of June 2020 are confusing and lack detail with respect to visitors and essential family caregivers.10 While the evidence concerning COVID-19 is still developing, some of the practical issues facing nursing homes were clarified by convening an expert panel and formulating guidance that begins to balance the well-being and self-determination of residents and their families with the very real public health concern of preventing nursing home outbreaks.

Our panel was able to review 119 guideline statements and develop consensus around 77 general statements to help inform a set of suggested visitor guidance statements. The panel strongly agreed on some preconditions that would be essential prior to welcoming back visitors, such as universal masking for staff, sufficient disinfecting supplies, PPE, and written plans around isolation, cohorting, screening, testing, and outbreak investigations. Furthermore, our panel had wide consensus on testing of symptomatic residents and staff, the importance of contact tracing, and barring communal and group activities for symptomatic residents. A key finding reinforced by the panel was the future need to assess individual residents' care preferences and level of risk tolerance, something that has been missing in many of the existing reopening guidelines, in part due to cohorting challenges. This was envisioned by the panel as allowing some residents to participate in a risk-accepting group that could be cohorted together for increased social interactions and dining.

However, as illustrated in Table 1, the panel did not reach accord on the nursing home-onset (NH-onset) case definition, testing of asymptomatic staff and residents, visitor guidance, and whether prior COVID-19 infection confers immunity or protection against transmission of SARS-CoV-2 to others.

Concerning the definition of a NH-onset case, a majority of panelists (68%) thought that the definition should not include an asymptomatic resident who has recovered from COVID-19 but tests positive again without new symptoms within 90 days of onset of symptoms. The most recent CDC guidelines support this conclusion, recommending that such residents not be retested within that 90-day window.27 The panel generally agreed that a nursing home should have no new NH-onset cases for 28 days prior to welcoming back visitors. According to CMS guidance, a COVID-19 nursing home outbreak, defined as a single NH-onset COVID-19 case,28 would automatically cause reinstitution of policies restricting communal dining, group activities, and visitors.23 While opposed to this strict definition, our panel overwhelmingly supported instituting a prompt and thorough outbreak investigation prior to automatic restrictions being reinstated.

On discussing surveillance testing, our panel evaluated testing in terms of 3 main categories: (1) asymptomatic residents and staff, (2) outbreak investigation, and (3) testing of symptomatic residents or staff. The panel agreed on testing symptomatic residents and staff, though our panel voted to allow an individual resident the choice to refuse. If a resident or surrogate decision maker declined testing during an outbreak investigation, our panel agreed the resident should be presumed positive and appropriately isolated. Furthermore, the panel agreed to require an outbreak investigation after one positive resident or staff and to include testing of close contacts, such as roommates, neighboring rooms, and staff with direct resident contact. Regarding testing of asymptomatic residents for the purposes of surveillance, the panel members reached only partial consensus (68% agreement) on whether a resident could opt out.

On the topic of visitor guidance, the panel had 3 key recommendations. First, there was strong consensus on infection prevention criteria for the nursing home, such as availability of disinfecting supplies and PPE while also having a clear and established plan surrounding isolation, cohorting, screening, testing, contact tracing, and outbreak investigations. Second, the panel agreed that visits should occur outdoors when feasible, with an option for indoors when resident, visitor, or weather conditions make an outdoor visit not possible. Third, the panel agreed that limited physical contact between visitors and residents should be allowed with meticulous hand hygiene before and after resident contact, and the use of masks, gowns and gloves. A lack of visitor access to PPE should not preclude a visit, so nursing homes must be able to provide masks, gloves and gowns when required.

The panel had less accord, however, regarding infection prevention strategies during a visit encounter. For example, universal masking for staff was supported but the group did not reach consensus on which type of mask (eg, surgical vs cloth) or whether all visitors had to wear a mask all of the time during a visit. Similarly, it was agreed that physical distancing be required in public, common spaces such as the lobby, hallways, or nursing stations, but perhaps not applicable during a visit encounter with an asymptomatic resident.

Regarding visitor guidance logistics, the panel strongly recommended the use of an electronic process to schedule visits and a sign-in log with contact information to aid in potential contact tracing. Additionally, the panel recommended allowing the designation of 1 or 2 essential family caregivers by the resident or surrogate decision maker. The essential family caregiver(s) and the surrogate decision maker would have priority to visit the resident. These visitors, for example, might provide complex care, such as assistance with feeding or support for responsive behaviors commonly encountered in residents with dementia. All visitors and essential family caregivers must be provided entry during serious illness, including at the end-of-life, irrespective of COVID-19 status of the resident, provided that the visitor dons appropriate PPE.

Lastly, regarding visitor guidance and risk tolerance, the panel acknowledged that essential family caregivers may wish to visit a resident who may be contagious such as (1) a symptomatic resident with a positive COVID-19 test, (2) a symptomatic resident with an unknown or pending COVID-19 test, or (3) an asymptomatic resident who has tested positive for COVID-19. After discussion, the authors recommend 3 steps be followed. First, a shared informed consent discussion between essential caregivers and nursing leadership that would include education and demonstration of proper donning and doffing of PPE and an understanding of the risks of potential exposure. Second, visitors should be discouraged from visiting a resident with a pending COVID-19 test with the exception of serious illness visits, including at the end-of-life. Lastly, visiting any resident with possible or confirmed COVID-19 should require the appropriate PPE.

Regarding immunity and cohorting, our panel agreed (83%) that cohorting asymptomatic residents who have all recovered for COVID-19 can be safely done and that a resident who has recovered from COVID-19, remains asymptomatic, and is at least 3 weeks post onset of symptoms is likely not infectious (88% consensus). Regarding the role of antibody testing, a modest majority agreed (69%) that antibody testing could be a surrogate marker of individual immunity; but all agreed that a positive immunity test does not currently inform clinical practice and instead one has to rely upon recovery from prior infection. It should be noted that the Delphi process occurred before the CDC guidance that recovered COVID-19 residents do not require re-testing or precautions for 90 days had been released.27

The areas of congruence leading to the suggested visitor guidance statements stem from thoughtful resident-centered debates among a panel of Delphi experts. The fact that there are many areas with substantial variation certainly arises from the state of the science but might also be a result of the interaction of certain statements with each other, difficulties with precise wording or statements, or the persistent inability of guidelines to accommodate the wealth of variations in clinical situations. One limitation of this study was that a rapid two-step modified Delphi process may not have allowed enough time for the panel to develop consensus around some of the challenging language or the more controversial topics, but the panel felt the urgency to produce high-quality guidance statements promptly.

The use of a modified Delphi process to standardize the process, provide iterative feedback, and consensus-gathering strengthens the findings of this study. The Delphi process itself limits bias but could be influenced by how panelists were selected.29 There was some degree of self-selection in the organization of this panel as the group shared a common concern regarding the health and well-being of the vulnerable older adults living in nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, the panel had substantial diversity but did not include all important stakeholders, such as nurse leaders, direct care workers, or residents. Nevertheless, the panelists were chosen for their expertise in the field of geriatrics and long-term care medicine, and have all been listed in the acknowledgment section.

Conclusions and Implications

The objective of this study was to develop a set of visitor guidance statements that could be used to welcome back visitors and essential family caregivers to US nursing homes. Even after a structured Delphi process, experts in nursing home care still had substantial discord on important elements. However, through rigorous and evidence-informed discussions, a concise and practical set of guidance statements was developed (Table 2), giving voice to the issues facing leaders in nursing homes as they try to welcome back visitors in a reasonable and safe manner. In the absence of timely and rigorous research, the involvement of post-acute and long-term care clinicians and patient care advocates is important to help create the balance between individual resident preferences and the health of the collective. The results of this Delphi process will help guide current policy decisions at the state and federal level as well as inform future research.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the time and dedication of our Delphi panel experts and other experts who have participated in this process, provided guidance, or critically appraised our manuscript. Their names are listed as follows in alphabetical order. None received compensation, financial or otherwise, for their contributions.

Leza Coleman, Koyia Figures, Swati Gaur, Elaine Healy, Karen Jones, Albert H. Lam, Noah Marco, Allison McGeer, Cheryl Phillips, Sabine von Preyss-Friedman, Verna Sellers, Fatima Sheikh, Ritu Suri, and DeAnn Walter.

Footnotes

All authors meet the 4 core criteria set forth by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICJME) for authorship.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2020.09.036.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Barnett M.L., Grabowski D.C. Nursing homes are ground zero for COVID-19 pandemic. 2020. https://jamanetwork.com/channels/health-forum/fullarticle/2763666 Available at: [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services COVID-19 nursing home data. 2020. https://data.cms.gov/stories/s/COVID-19-Nursing-Home-Data/bkwz-xpvg Available at: [PubMed]

- 3.Ouslander J.G., Grabowski D.C. COVID-19 in nursing homes: Calming the perfect storm. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020 Jul 31 doi: 10.1111/jgs.16784. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D'Adamo H., Yoshikawa T., Ouslander J.G. Coronavirus Disease 2019 in geriatrics and long-term care: The ABCDs of COVID-19. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:912–917. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arons M.M., Hatfield K.M., Reddy S.C. Presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections and transmission in a skilled nursing facility. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2081–2090. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2008457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoxha A., Wyndham-Thomas C., Klamer S. Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection in Belgian long-term care facilities. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 Jul 3 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30560-0. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldberg S.A., Lennerz J., Klompas M. Presymptomatic transmission of SARS-CoV-2 amongst residents and staff at a skilled nursing facility: Results of real-time PCR and serologic testing. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Jul 15 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa991. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McMichael T.M., Currie D.W., Clark S. Epidemiology of Covid-19 in a long-term care facility in King County, Washington. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2005–2011. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2005412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS Announces New Measures to Protect Nursing Home Residents from COVID-19. Available at: htpps://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-announces-new-measures-protect-nursing-home-residents-covid-19, Accessed August 19, 2020.

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Preparing for COVID-19 in nursing homes. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/long-term-care.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fhealthcare-facilities%2Fprevent-spread-in-long-term-care-facilities.html Available at:

- 11.Karlawish J., Grabowski D.C., Hoffman A.K. The Washington Post; Washington, DC: 2020. Continued bans on nursing home visitors are unhealthy and unethical. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hado E., Friss Feinberg L. Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, meaningful communication between family caregivers and residents of long-term care facilities is imperative. J Aging Soc Policy. 2020;32:410–415. doi: 10.1080/08959420.2020.1765684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Academies of Sciences, E, Medicine . The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2016. Families Caring for an Aging America. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schlaudecker J.D. Essential family caregivers in long-term care during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:983. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suarez-Gonzalez A. LTCcovid, International Long-Term Care Policy Network: Care Policy and Evaluation Centre (CPEC), London School of Economics; London, England: 2020. Detrimental effects of confinement and isolation on the cognitive and psychological health of people living with dementia during COVID-19: emerging evidence. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stall N.M., Johnstone J., McGeer A.J. Finding the right balance: An evidence-informed guidance document to support the re-opening of Canadian nursing homes to family caregivers and visitors during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:1365–1370.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Low L. Easing lockdowns in care homes during COVID-19: Risks and risk reduction. 2020. https://ltccovid.org/2020/05/13/easing-lockdowns-in-care-homes-during-covid-19-risks-and-risk-reduction/ Available at:

- 18.Abbasi J. Social isolation-the other COVID-19 threat in nursing homes. JAMA. 2020 Jul 16 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.13484. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trabucchi M., De Leo D. Nursing homes or besieged castles: COVID-19 in northern Italy. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:387–388. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30149-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kusmaul N. COVID-19 and nursing home residents' rights. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:1389–1390. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chu C.H., Donato-Woodger S., Dainton C.J. Competing crises: COVID-19 countermeasures and social isolation among older adults in long-term care. J Adv Nurs. 2020 Jul 9 doi: 10.1111/jan.14467. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diamantis S., Noel C., Tarteret P. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)-related deaths in French long-term care facilities: The “Confinement Disease” is probably more deleterious than the coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) itself. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:989–990. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Nursing home reopening recommendations for state and local officials. 2020. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/qso-20-30-nh.pdf-0 Available at:

- 24.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Nursing Home reopening recommendations frequently asked questions. 2020. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/covid-nursing-home-reopening-recommendation-faqs.pdf Available at:

- 25.Jones J., Hunter D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ. 1995;311:376–380. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7001.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fitch K., Bernstein S., Aguilar M.D. RAND; Santa Monica, CA: 2001. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method User's Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Duration of isolation and precautions for adults with COVID-19. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/duration-isolation.html Available at:

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Testing guidelines for nursing homes. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/nursing-homes-testing.html Available at:

- 29.Hallowell M.R. Techniques to minimize bias when using the Delphi method to quantify construction safety and health risks. In: Ariaratnam S.T., Rojas E.M., editors. Building a Sustainable Future. American Society of Civil Engineers; Seattle, WA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.