Abstract

Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is the most common type of pancreatic cancer and is the third leading cause of adult cancer death in the United States with a single-digit 5-year survival rate despite significant advances in understanding the genetics and biology of the disease. Glycogen synthase kinase-3α (GSK-3α) and GSK-3β are serine/threonine kinases encoded by distinct genes that have been shown to localize to the cytoplasm, mitochondria and nucleus. Although they are highly homologous within their kinase domains and known to phosphorylate an overlapping set of target proteins, genetic studies have shown that GSK-3β phosphorylates and regulates the activity of several proteins that participate in pathways that promote neoplastic transformation. Significantly, GSK-3β is progressively overexpressed during PDAC development and has been shown to play an important role in tumor development, progression and resistance to chemotherapy. Thus, novel therapeutic approaches designed to target GSK-3β or the signaling cascades that regulate its expression have become attractive targets for treating PDAC.

Areas covered

This review describes and summarizes the expanding cellular mechanisms regulating GSK-3β activity, including upstream translational and post-translational regulation, as well as the downstream cellular targets and their functions in PDAC cell growth, cell fate, metastasis and chemotherapeutic resistance.

Expert opinion

With approximately 100 identified substrates impacting a large number of signaling pathways and transcriptional regulation, the role of GSK-3 kinases are generally considered to be cell- and context-specific. Mutation of the KRas gene is found in over 95% of PDAC patients, where it plays an essential role in PDAC initiation. In addition, oncogenic KRas drives the transcriptional expression of the GSK-3β gene which has been shown to regulate the proliferation and survival of PDAC cells, as well as resistance to various chemotherapies. Thus, the combination of GSK-3 inhibitors with chemotherapeutic drugs could be a promising therapeutic strategy for PDAC.

Keywords: GSK-3, GSK-3 inhibitors, KRas, pancreatic cancer, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, targeted therapy

1. Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), the most common form of pancreatic cancer, is a recalcitrant tumor that is among the leading cause of cancer-related deaths. The incidence and mortality rates have increased since 1975, and is presently the third leading cause of cancer death in the United States and is predicted to be the second cause of cancer death by 2030 [1, 2, 3]. Notably, the absolute number of new cases and deaths due to pancreatic cancer has increased steadily in the U.S. since 2000 with an estimated 56,770 new cases and 45,750 new deaths in 2019 [3]; there has been a nearly 2-fold increase in new cases and pancreatic cancer accounts for 7.3% of all cancer deaths [3]. The rise in the number of cases is primarily due to the aging of the “baby-boomer” generation (Americans born between 1945 and 1964), as pancreatic cancer is associated with later age of onset (median age 69 years) [4]. The low survival from pancreatic cancer is in part due to the advanced stage at diagnosis in the majority of cases: by the time of diagnosis, eighty percent of PDAC are no longer localized to the pancreas. To date, no reliable screening tests or effective cures for pancreatic cancer are available. Moreover, PDAC responds poorly to chemotherapy and radiation therapy regardless of the stage of disease, highlighting the urgent need for more research into the biology of the disease in order to develop more effective targeted therapeutic strategies [5]. Thus, if we are to make inroads in preventing and treating this cancer in the coming decade, we must have a better understanding of this disease and identify the key pathways for therapeutic intervention.

Glycogen synthase kinase 3α (GSK-3α) and GSK-3β are highly homologous serine/threonine kinases encoded by different genes. With approximately 100 known targets, these kinases have been implicated in regulating multiple cellular pathways that contribute to normal cellular/organismal homeostasis, but also to tumor development, progression and metastasis [6]. Indeed, GSK-3β is overexpressed in several tumors including PDAC and its mRNA level is negatively associated with shorter survival of PDAC patients [7, 8]. GSK-3β has been shown to regulate acinar-to-ductal metaplasia (ADM) initiation in a genetically engineered mouse model, promote PDAC cell growth and survival through its regulation of NF-κB and NFAT transcriptional activity, and most recently, regulate the ATR DNA damage response pathway, thereby protecting PDAC cells from chemotherapy [9, 10, 11, 12]. Altogether, these results highlight a prominent role for GSK-3β as a tumor promotor and regulator of chemoresistance in PDAC, and provide a rationale for advancing novel GSK-3β inhibitors to the clinic for the treatment of this deadly cancer.

In this review, we will discuss the mechanisms leading to the increased expression of GSK-3β in PDAC, and the effects of GSK-3β on pathways that potently promote PDAC cell proliferation, survival and chemoresistance.

2. GSK-3α and GSK-3β kinases and their regulation in PDAC

GSK-3 kinases were first purified from rabbit skeletal muscle in 1980 and named for their specific kinase activity toward glycogen synthase [13]. Two isoenzymes, GSK-3α and GSK-3β, with over 95% sequence identity in their kinase domains, were cloned a decade later [14]. Based on their subcellular localization and ubiquitous expression pattern in tissues and cells, it was suggested that these kinases would have roles other than regulating glycogen metabolism [14]. In fact, GSK-3 kinases have now been recognized to regulate a wide range of cellular functions and participate in the pathogenesis of various human diseases, such as diabetes, inflammation, neurological disorders, and cancer [15, 16, 17]. This is largely due to its association with a variety of other signaling pathways and identification of over 100 bona fide substrates, including many transcription factors [18, 19, 20]. Despite the high-degree of similarity within their kinase domains, homozygous deletion of GSK-3β in mice results in embryonic lethality caused by sever liver degeneration with excessive tumor necrosis factor (TNF) toxicity and inactivation of NF-κB transcriptional activity toward key anti-apoptotic genes. Significantly, GSK-3α could not compensate for the loss of GSK-3β providing evidence that these kinases are not merely functionally redundant, but likely, while having overlapping targets (e.g. glycogen synthase, β-catenin), they also have discrete targets (NF-κB), which allow them to regulate unique cellular outcomes in response to extracellular stimuli [21, 22, 6]. In the following paragraphs, we will describe the mechanisms regulating GSK-3β gene and protein expression, as well as the known mechanism regulating GSK-3 kinase activity.

2.1. Transcriptional and translational regulation of GSK-3

Two decades after its discovery, GSK-3β was shown to be overexpressed in a variety of human malignancies including pancreatic, renal, ovarian, colon and glioblastoma as we reviewed recently [23]. In pancreatic cancer, GSK-3β protein expression was found to increase in preneoplastic lesions known as PanINs (pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia) compared to normal ductal epithelium [24]. The level of GSK-3β protein further increased in PDAC and was found to accumulate in the nucleus of most moderately and poorly differentiated tumors. Several potential mechanisms driving this overexpression have recently been revealed.

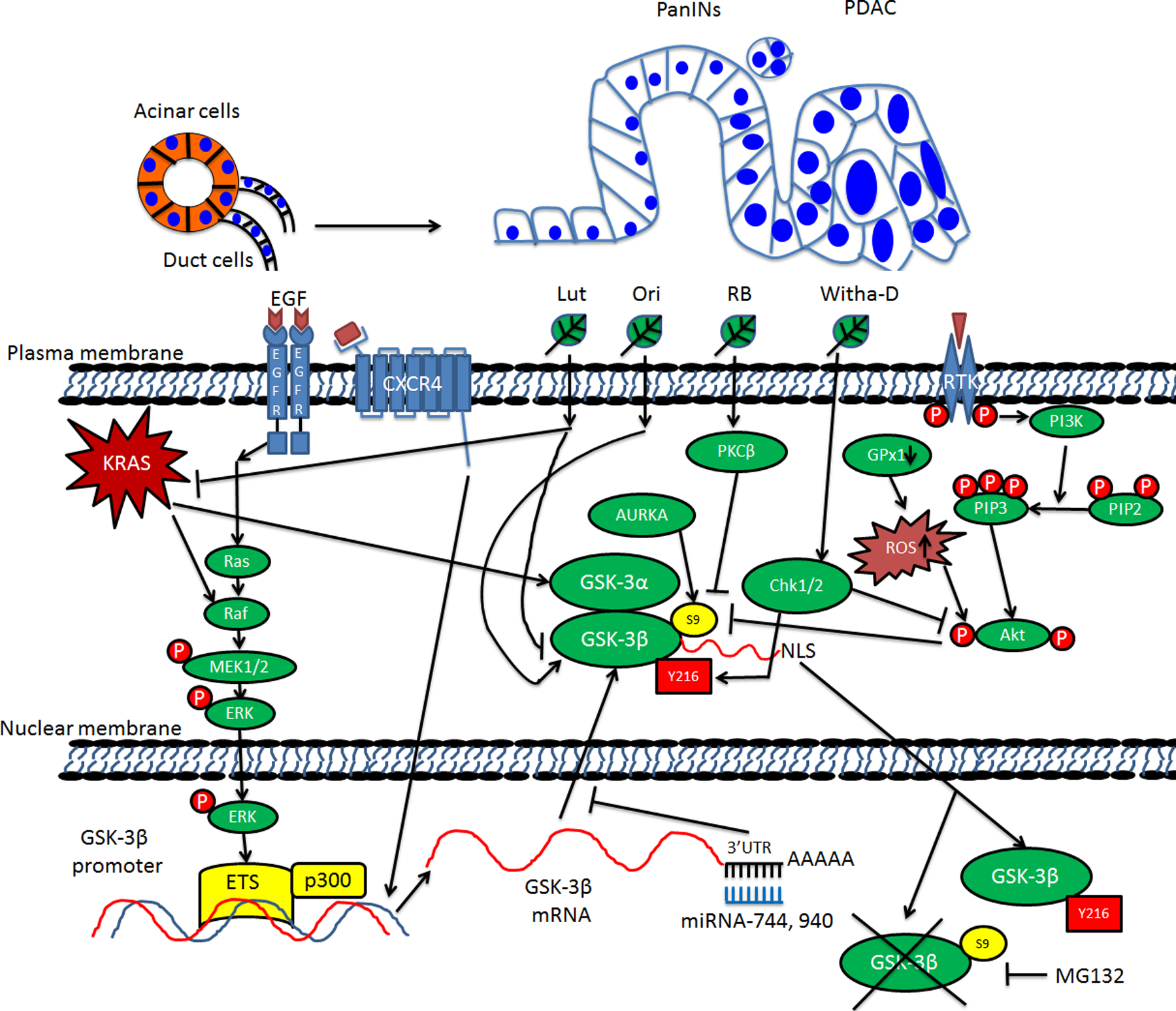

Mutationally activated KRas is found in over 95% of PDAC and represents the most frequent and earliest genetic alteration [25, 26]. The link between oncogenic KRas mutation and GSK-3β overexpression was first revealed by Zhang et al., who showed that overexpression of constitutively active Ras isoforms (H, K and N) are capable of enhancing GSK-3β promoter activity and increasing mRNA expression in pancreatic cancer cell lines carrying both wild type and mutant KRas (Figure 1). The mutant Ras-driven GSK-3β transcription was shown to be dependent on MAPK signaling leading to the formation of p300/CBP histone acetyltransferase recruitment and binding of ETS transcription factors to the GSK-3β promoter [27]. Interestingly, overexpression of mutant KRas in HPDE cells, an immortalized normal human pancreatic ductal epithelial cell line, upregulated both GSK-3α and GSK-3β gene expression [28]. Since oncogenic mutations in Ras genes and Raf are found in many human cancers, it is not surprising to see increased GSK-3 kinase gene expression and protein in a large number of cancers.

Figure 1. Model of transcriptional, translational and post-translational regulation of GSK-3 in PDAC.

PanINs: Pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia; PDAC: Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; EGF: Epidermal growth factor; EGFR: Epidermal growth factor receptor; CXCR4: C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4; RTK: Receptor tyrosine kinase; MEK1/2: MAPK/ERK kinase 1/2; ETS: E-twenty six; GSK-3α: Glycogen synthase kinase-3α; GSK-3β: Glycogen synthase kinase-3β; 3’-UTR: 3’-untranslated region; miRNA: microRNA; AURKA: Aurora kinase A; Chk1/2: Check point kinase 1/2; GPx1: glutathione peroxidase-1; ROS: Reactive oxygen species; Akt: A serine/threonine protein also known as protein kinase B (PKB); PI3K: Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; PIP2: Phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate; PIP3: Phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate; NLS: Nuclear localization signal or sequence; S9: Serine-9 phosphorylation; Y216: Tyrosine-216 phosphorylation; MG132: Carbobenzoxy-Leu-Leu-Leucinal. Black arrows between two elements indicate activating events in pathways. Black blocked arrows between two elements indicate inactivating events in pathways. Black arrows pointing up or down next to one element indicate increasing or decreasing. Crossed black lines indicate degradation.

Increased GSK-3 protein expression has also been observed in mouse models. Using the well-established PDX1-cre/LSL-KRasG12D (KC) mouse model, we observed increased expression of both GSK-3 kinases in the context of caerulein-induced acute pancreatitis and the development of acinar-to-ductal metaplasia (ADM) [9]. Significantly, caerulein-treated KC mice given a GSK-3 inhibitor prevented inflammation and the development of ADM [11], supporting the idea that GSK-3 is one of the main targets of oncogenic KRas signaling in promoting this early step of PDAC development in the mouse model (Figure 1). Interestingly, genetic deletion of GSK-3β in the KC mouse model could also limit the initiation of PDAC precursor lesions following an inflammatory insult suggesting a critical role for GSK-3β in this process [9]. Although this shows a role for GSK-3β in the development and generation of preneoplastic lesions in the pancreas, the utility of any GSK-3 inhibitor at this early stage in humans is unlikely since most patients with PDAC present with late stage disease [3]. However, the fact that GSK-3β is participating in the development of these early lesions suggests that cooperation of GSK-3β and oncogenic KRas signaling could provide an opportunity to develop new models to identify biomarkers for early detection.

Several natural products/herbs have also been shown to exhibit a strong effect on regulating GSK-3β protein expression. Luteolin (Lut), a member of the flavone subclass of flavonoids that can be found in fruits, vegetables and herbs, could inhibit expression of both KRas and GSK-3β as determined by immunohistochemical staining (Figure 1) [29]. Lut was also shown to prevent the growth of PDAC tumors in an orthotopic mouse model [29]. Thus, while a dominant role of oncogenic KRas signaling in regulating GSK-3 expression at the transcriptional level is clear, other mechanisms also contribute to GSK-3 protein expression in PDAC cells.

2.2. Post-translational regulation of GSK-3

Phosphorylation of substrates by GSK-3 kinases can lead to either inactivation/proteasomal degradation or enhanced activity and protein stabilization. For this reason, GSK-3 kinases have been implicated in regulating numerous signaling pathways associated with various human diseases including cancer, inflammation, neurodegenerative diseases, as well as promoting the cell growth, cell viability, migration and drug resistance in pancreatic cancer [30, 31, 32]. In stark contrast to most kinases, GSK-3 kinases are constitutively active in resting/unstimulated cells [33]. Moreover, GSK3 kinases prefer to phosphorylate S/T residues 4 amino acids N-terminal to a S/T that has been pre-phosphorylated by another kinase (S/TXXXpS/pT). This C-terminal localized “priming” phosphorylation by another kinase is required for sequential GSK-3 phosphorylation through its ability to induce a conformational change of the substrate to fit into its “binding pocket” within the kinase domain [15, 34, 35].

GSK-3 kinase activity is also regulated by its own phosphorylation, by protein complex formation, and by localization in subcellular compartments [18, 16, 36, 30]. In fact, stimulation of cells with various ligands can lead to the inactivation of GSK-3 kinases by either direct phosphorylation of an inhibitory residue found in their N-termini (S21 in GSK-3α or S9 GSK-3β, these sites of phosphorylation represent a pseudosubstrate for their kinase domain) by Akt (Figure 1), or by disruption of protein complexes in which GSK-3 kinases reside, such as the β-catenin destruction complex, which regulates the levels and nuclear accumulation of β-catenin in response to Wnt ligands (see below for more details). In addition to this inhibitory phosphorylation, tyrosine phosphorylation within the kinase domain (Y279 in GSK-3α or Y216 GSK-3β) is associated with increased kinase activity. Significantly, PDAC cell lines and tissues show increased Y216 and decreased S9 phosphorylation suggesting that GSK-3β is active in pancreatic cancer [37, 7, 38]. Lastly, while various mechanisms have been proposed to regulate the cytoplasmic to nuclear shuttling of GSK-3β, our prior published data indicate that its ability to accumulate in the nucleus requires active kinase activity. Indeed, treatment of PDAC cell lines with GSK-3 inhibitors led to a rapid proteasome-dependent loss of GSK-3β from the nucleus [7]. Additionally, while wild-type and constitutively active (S9A) GSK-3β could accumulate in the nucleus, a kinase-inactive mutant could not [7]. Taken together, these data suggest that once in the nucleus, GSK-3β must be active and likely targets some protein(s) that prevent its degradation until it is inactivated.

In addition to Akt, protein kinase A (PKA), and p70 S6 kinase have been shown to phosphorylate S9 of GSK-3β leading to its inactivation (Figure 1) [39, 16]. Moreover, irradiation of PANC-1 cells diminished intracellular hydrogen peroxide levels due to increased catalase activity, which prevented the inactivation of GSK-3β [40]. In another example, addition of Withanolide-D to PDAC cell lines induced a dose-dependent reduction of Akt activity followed by a concomitant decrease in S9 phosphorylation and increased Y216 phosphorylation of GSK-3β in PDAC cells [41]. Another study indicated that GSK-3 phosphorylation was significantly increased in PDAC cell lines upon treatment with Resibufogenin (RB), one of the major active components in a traditional anti-cancer medicine in China and other Asian countries [42]. However, the PI3K/Akt inhibitor LY294002 failed to suppress RB-induced GSK-3 phosphorylation, which the authors showed was mediated through Protein Kinase Cβ (PKCβ) [42]. Using cell lines and an orthotopic mouse model bearing a tumor cell line derived from KPC mice (Cre/KRasG12D/TP53mut), Yangchun et al., concluded that genetic depletion or pharmacological inhibition (with CCT137690) of Aurora Kinase A (AURKA) significantly inhibited S9 phosphorylation of GSK-3β together with induction of necroptosis and reduced tumor growth [8]. Lastly, Protein Kinase G (PKG) has also been shown to have an impact on GSK-3 activity since DT3, an inhibitor of PKG, resulted in decreased phosphorylation of GSK-3 in the murine PDAC cell line Panc02 in vitro, as well as reduced tumor volume and metastases in tumor-bearing animals [43]. It should be pointed out that the only readout of GSK-3β activity in this article was the level of phosphorylation. It remains possible that DT3 has other off-target effects that might have contributed to the decreased cell proliferation and survival.

One of the most well know targets of GSK-3 kinases is β-catenin. The regulation of GSK-3 kinases within what is known as the β-catenin destruction complex is likely the most well-studied. This complex contains GSK-3 kinases as well as Axin, the tumor suppressor protein adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), casein kinase 1 (CK1), disheveled (Dvl), β-TrCP, and β-catenin. Under resting conditions, β-catenin is phosphorylated by CK1 at S45, which acts as a pre-primed site for GSK-3 kinases, which subsequently phosphorylate S41, S37 and S33. This phosphorylation allows recognition by β-TrCP leading to the ubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation of β-catenin. However, the binding of Wnt ligand to its receptor Frizzled leads to the phosphorylation of the Wnt co-receptor LRP5/6. This phosphorylation leads to the recruitment of Axin, which results in the dissolution of the destruction complex and stabilization and nuclear translocation of β-catenin [16, 44]. However, in pancreatic cancer, the regulation between Wnt/β-catenin signaling and GSK-3 activity is far more complicated based the following evidence: (1) Wnt/β-catenin signaling is involved in PDAC tumorigenesis and has been ranked as one of the top 12 core pathways for tumor development, but mutations in key members of Wnt/β-catenin are rare in PDAC samples [45]. (2) GSK-3 isoenzymes have an equal role in Wnt signaling and inhibition of GSK-3 has to reach ~70% threshold to impact β-catenin stability and nuclear translocation, indicating there is only a small fraction of cellular GSK-3 that is associated with Axin and relevant to β-catenin degradation [16]. (3) As discussed earlier, whereas GSK-3β is overexpressed and accumulated in the nucleus of advanced PDAC, increased β-catenin expression has also been reported in late stage pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) lesions in human with mostly cytoplasmic and less than 10% nuclear localization [46]. (4) Pancreas specific knockout of GSK-3β in KC mice didn’t change the expression or localization of β-catenin while inhibition of GSK-3 using small molecules only led to increased membranous expression of β-catenin and reduced cyclin D1 expression, a well-accepted target of nuclear β-catenin/TCF complexes [9, 47]. Taken together, these data suggested the existence of different pools of GSK-3, those that are involved in regulating β-catenin-dependent pathways and those that are involved in modulating the stability and activities of other proteins associated with PDAC tumor development and progression [44, 46].

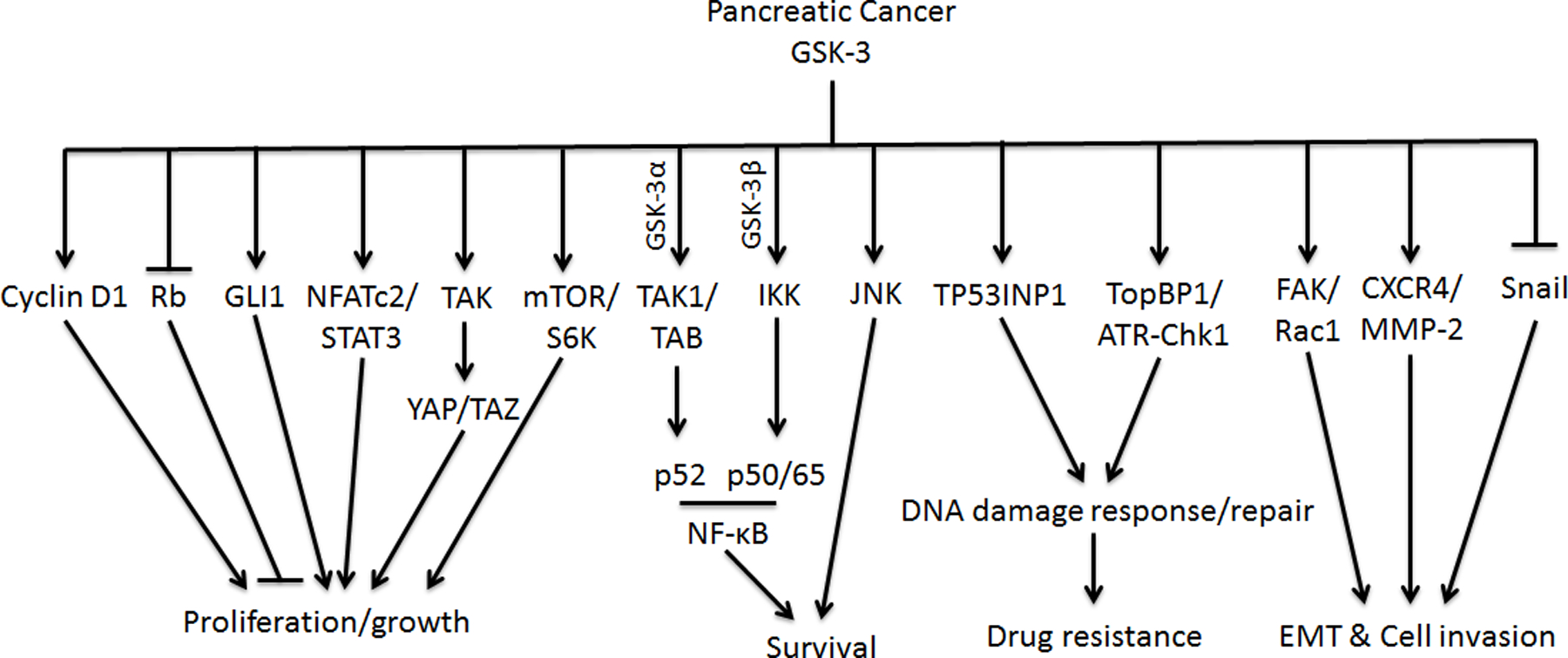

Given the fact that some substrates of GSK-3β, such as glycogen synthase, are cytosolic proteins, whereas others, notably several transcription factors, such as NF-κB p65, NFAT, c-Myc, and c-Jun are nuclear proteins (Figure 2), the mechanisms regulating the nuclear accumulation GSK-3β are of significant interest [18]. Notably, nuclear localization of GSK-3β is dynamic and requires its kinase activity in order to maintain its nuclear accumulation. Several mechanisms governing the translocation of GSK-3 have been revealed, including activated PKB/Akt, binding of FRAT1 and the existence of a bipartite nuclear localization sequence (NLS) within the GSK-3β kinase domain (reviewed in [16]). Additionally, another early study reported that pro-apoptotic stimuli increased Y216 phosphorylation in GSK-3β in the nucleus suggesting that activated nuclear GSK-3β is linked with pro-survival responses [48]. Consistent with this result, Zhang et al., confirmed that nuclear GSK-3β exhibited minimal S9 phosphorylation, and transfection of mammalian suppression/re-expression plasmids, which could deplete endogenous GSK-3β and express modified GSK-3β containing either a nuclear export signal (NES) or NLS, established that re-expression of the nuclear but not cytoplasmic-targeted S9A mutant induced expression of the NF-κB anti-apoptotic proteins, Bcl-xL and cIAP [49]. Whether, in this context nuclear GSK-3β was directly phosphorylating NF-κB to regulate its activity or targeting other epigenetic or transcriptional factors to promote the expression of these genes is unknown. Of note, it was recently shown in glioblastoma stem cells that GSK-3β phosphorylated the histone lysine demethylase Kdm1a in order to protect it from MDM2-mediated degradation, thus maintaining the stem cell program in these cells [50]. Whether GSK-3β also targets this or other epigenetic regulators in PDAC stem cells remains to be determined.

Figure 2. Model of GSK-3 targets and their regulations in PDAC proliferation, survival, drug resistance and metastasis.

GSK-3: Glycogen synthase kinase-3; GSK-3α: Glycogen synthase kinase-3α; GSK-3β: Glycogen synthase kinase-3β; Rb: Retinoblastoma; GLI1: glioma-associated oncogene homologue 1; NFATc2: Nuclear factor of activated T-cells, cytoplasmic 2; STAT3: Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; TAK: TGF-β–activated kinase 1; YAP: Yes-associated protein; TAZ: Transcriptional coactivator with a PDZ-binding domain; mTOR: Mammalian target of rapamycin; S6K: Ribosomal protein S6 kinase; TAB: TAK1-binding partner; IKK: Activation of the IκB kinase; JNK: c-Jun N-terminal kinase; TP53INP1: Tumor protein p53 inducible nuclear protein 1; TopBP1: topoisomerase 2-binding protein 1; ATR: ATM and Rad3-related kinase; Chk1: Check point kinase 1; FAK: Focal adhesion kinase; Rac1: Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1; CXCR4: C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4; MMP-2: Matrix metalloproteinase-2; NF-κB: Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; DNA: Deoxyribonucleic acid; EMT: Epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Black arrows indicate activating events in pathways. Black blocked arrows indicate inactivating events in pathways.

2.3. GSK-3 and PDAC cell growth

GSK-3 inhibition in pancreatic cancer, achieved by either RNA interference or GSK-3 specific inhibitors, has proven to strongly limit the growth of pancreatic cancer cells in vitro and in vivo in various models [24, 7, 38, 37, 51]. The underlying mechanisms for GSK-3-dependent pancreatic cancer cell proliferation is summarized and discussed here. One of the fundamental findings of the role of GSK-3 in cell cycle regulation is that GSK-3β could directly phosphorylate cyclin D1 on Thr-286 and trigger its proteasomal degradation and nuclear depletion, which led to conclusion that GSK-3β would suppress tumor development by limiting cell cycle progression (Figure 2) [52]. Paradoxically, Kitano et al., found that inhibition of GSK-3β activity with a small molecule inhibitor resulted in less cyclin D1 protein and decreased cyclin D1/cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 4/6 complex-dependent phosphorylation of the Rb tumor suppressor protein [47]. In addition, the GSK-3 inhibitor lithium could inhibit PDAC cell proliferation, block G1/S cell-cycle progression through induction of the ubiquitin-dependent proteasomal degradation of downstream components of the HH signaling pathway glioma-associated oncogene homologue (GLI1) [53]. Moreover, in contrast to the published evidence that GSK-3β-mediated phosphorylation of the SP2 region in NFATc2 resulted in nuclear export in immune cells [54], GSK-3β-mediated phosphorylation of the SP2 region stabilized nuclear NFATc2 protein levels in the nucleus of PDAC cells resulting in increased NFATc2-mediated transcription of target genes [55,11]. In this paper, the authors also indicated that GSK-3β is important for the Y705 phosphorylation of STAT3 leading to the formation of NFATc2-STAT3 complexes, which regulated the expression of genes involved in cell proliferation, survival, inflammation and metastasis (Figure 2). It is not clear how GSK-3β mediated the phosphorylation of STAT3, but it might be through the regulation of a tyrosine kinase that remains to be defined. A recent study published by Santoro et al., showed that instead of stabilizing YAP/TAZ proteins, as was shown in embryonic stem cells treated with the GSK-3 inhibitor LY2090314 [56], treatment of mice bearing orthotopically-implanted PDAC tumors led to a significant decrease in TAK1 and YAP/TAZ protein expression and a reduction in the number of proliferating cells [57]. Lastly, consistent with the role of GSK-3β in promoting p70 ribosomal protein S6 kinase (p70S6K) activity and cell proliferation in mouse embryonic fibroblasts and 293T cells [58], it was recently demonstrated that knockout of GSK-3β in the KC mouse model induced a profound reduction of DNA synthesis and diminished S6K phosphorylation [9]. Taken together, these data indicate that not every pathway observed to be regulated by GSK-3β in normal cells or other cell models, is necessarily conserved in PDAC cells, and must therefore be interrogated on a case-by-case basis.

2.4. GSK-3 and PDAC cell viability and drug resistance

Currently, there are several available therapeutic options for pancreatic cancer, including surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy. However, due to the broad heterogeneity of genetic mutations and dense stromal environment, PDAC cells usually develop alternative pathways associated with pro-survival networks to compromise conventional chemotherapies and novel therapeutics [59]. GSK-3 kinases have been implicated in regulating signaling pathways related to PDAC chemoresistance [31]. Thus, targeting these kinases might sensitize PDAC cells that have become resistant to conventional chemotherapy.

NF-κB is a transcription factor that is constitutively activate in most pancreatic cancer cell lines, and its activation can suppress pro-apoptotic signaling pathways through the induction of several anti-apoptotic genes [60]. Ougolkov et at., first reported that GSK-3β played an essential role in maintaining basal NF-κB reporter activity and expression of the NF-κB target genes, Bcl-2 and XIAP in pancreatic cancer cells independent of IKKβ activity [24]. Interestingly, Wilson et al., demonstrated that GSK-3β promoted constitutive NF-κB signaling by regulating IKK activity [61]. Moreover, nuclear GSK-3β, but not GSK-3α, could regulate NF-κB p65/p50 binding to the promoter of BIR3 and BCL2L1 and GSK-3 inhibitors significantly enhanced TRAIL- or TNFα-induced apoptosis in PDAC cells, which could be ameliorated by Bcl-xL overexpression [49]. Surprisingly, GSK-3α has also been found to facilitate constitutive TAK1 activity by maintaining TAK1-TAB1 interaction, and depletion of GSK-3α but not GSK-3β suppressed nuclear p52 levels, suggesting a unique role for GSK-3α in driving activation of the noncanonical NF-κB pathway associated with PDAC survival [28]. Nonetheless, inhibition of GSK-3 has been shown to increase Bim expression and potentiate the death-ligand-induced apoptotic response, which required c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) activity [62].

In regard to the critical role of GSK-3 in stimulating PDAC cell growth and anti-apoptotic response, several studies have been conducted to explore the potential benefit of combination therapies in pancreatic cancer using GSK-3 inhibitors. Two individual groups tested the GSK-3 inhibitor AR-A014418 in combination with gemcitabine and showed that AR-A014418 had a synergistic effect in killing PANC-1 cells in vitro and in vivo in a subcutaneous xenograft model [63, 64]. Unexpectedly, Mamaghani et al., found that AR-A014418 only had additive, sub-additive, or even antagonistic effect in other PDAC cell lines they tested even though NF-κB activity was disrupted upon GSK-3 inhibition in all of the cell lines tested [64]. Shimasaki et al., showed that p53-induced nuclear protein 1 was the target of GSK-3β in regulating cell death and DNA repair [63]. Peng et al., found that lithium synergistically enhanced the anti-cancer effect of gemcitabine through down-regulation of GLI1-associated apoptosis [53]. Elmaci and Altinoz proposed that a triple-clinical approved agent combo, including lithium, may provide a metabolic adjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer [65]. Moreover, Edderkaoui and colleagues designed and synthesized metavert, a dual GSK-3β and histone deacetylase 2 inhibitor [66]. Significantly, metavert increased the killing of drug-resistant PDAC cells by paclitaxel and gemcitabine, and in combination with gemcitabine, metavert significantly extended the survival time of KPC mice or mice bearing syngeneic tumors.

Recently, it was shown that 9-ING-41, a GSK-3 inhibitor that is currently in a phase Ia/b clinical trial, could overcome chemoresistance in patient-derived xenografts from breast cancer, impair tumor growth in renal cell cancer and neuroblastoma [51, 67, 68, 69]. The mechanism by which this inhibitor was overcoming chemoresistance in these tumors was not clear, and was assumed to be through the known regulation of NF-κB by GSK-3β, since increased NF-κB-mediated expression of anti-apoptotic genes are thought to be a general mechanism of chemotherapy resistance. However, we recently identified a new target of GSK-3 kinases that could help explain their ability to promote chemoresistance. We found that treatment of PDAC cells with Bio (a ‘toolkit’ GSK-3 inhibitor) or 9-ING-41 prevented the activation of the ATR-DNA damage response pathway following treatment with gemcitabine [12]. Indeed, cells treated with the inhibitor failed to undergo S-phase arrest or phosphorylate Chk1 following gemcitabine treatment [12]. Significantly, mice bearing orthotopic tumors of PDX-derived cell lines resistant to gemcitabine or irinotecan could be made sensitive when also given 9-ING-41 [12]. Mechanistically, it was found that GSK-3 kinase activity is required to prevent the proteasome-dependent degradation of TopBP1 (Figure 2), a critical ATR adaptor molecule that is recruited to damaged DNA and obligate in the full activation of ATR kinase activity in response to single-stranded DNA damage [12]. Moreover, several recent studies from different groups have revealed a strong cell cycle arrest (predominantly G2 arrest) effect of 9-ING-41 in cell lines from renal cancer, lymphoma, bladder cancer [68, 70, 71]. In preclinical and clinical studies, the cell cycle targeting drug nab-Paclitaxel (Abraxane) showed profound synergistic activity in combination with gemcitabine and has now become standard first-line therapy for advanced pancreatic cancer [72]. Whether 9-ING-41 will synergize with other chemotherapeutics that induce single-stranded DNA damage or cell cycle arrest in PDAC or other tumors will be an important area of future investigation.

2.5. GSK-3 and PDAC metastasis and invasion

In addition to the role of GSK-3 in pancreatic cancer cell growth, cell fate determination and drug resistance, several studies investigated the function of GSK-3 in regulating PDAC cell metastasis and invasion. Inhibition of GSK-3 in pancreatic cancer cells significantly attenuated the migration and invasion with altered subcellular localization of Rac1 and F-actin, reduced secretion of matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) and diminished phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) [47], and overexpression of GSK-3β upregulated CXCR4 and MMP-2 expression and promoted CXCR4-dependent invasion of PANC1 cells (Figure 1 and 2) [73]. In contrast, other groups have published evidence that activation of an Akt/GSK-3β/Snail signaling pathway, resulted in the inhibition of GSK-3β activity and EMT and invasion of PDAC cells [74, 75, 76]. In addition, treatment of a tetracycline diterpenoid compound extracted from the traditional Chinese medicine, Oridonin, elevated protein levels of GSK-3β in PDAC cells and reduced migration of SW1990 in vitro, which could be inhibited by CHIR, a GSK-3 inhibitor [77]. Lastly, microRNAs (miRNAs), endogenous non-coding small RNA that can target mRNAs for cleavage or translational repression have been shown to regulate key pathways that contribute to pancreatic carcinogenesis and progression [78, 79]. Interestingly, two different miRNAs (miR-744 and miR-940) were reported to bind unique regions within the 3’-UTR of GSK-3β mRNA and overexpression of such miRNAs led to decreased GSK-3β expression and cancer cell invasion [80, 81]. Overall, the role of GSK-3β in pancreatic cancer metastasis and invasion will require further investigation.

3. Conclusion

GSK-3 plays a central role in pancreatic cancer initiation, progression and survival. The premalignant pancreatic cells that harbor oncogenic KRas mutation trigger the overexpression of GSK-3 kinases, which can target different substrates, including transcription factors and signaling molecules, that promote tumor growth, survival and chemoresistance. Further delineation of the pro-tumorigeneic signaling and transcriptional pathways that are being regulated by GSK-3 kinases will be an area of significant interest as it could identify new molecular pathways to target. Indeed, the identification that GSK-3 kinases have a prominent role in regulating the response to DNA damage induced by chemotherapy is just one recent discovery that has the potential to impact the use of GSK-3 inhibitors with chemotherapy in cancer. Moreover, while 9-ING-41 is in the clinic, there are likely several other inhibitors under development that will likely enter the medical oncologists toolkit in the coming years. These GSK-3 inhibitors as single agents or in combination with other conventional and novel therapies have the potential to improve the outcomes for patients with PDAC.

4. Expert opinion

In PDAC, the majority of research has focused on GSK-3β, leaving the role for GSK-3α in this disease unknown. Despite this, it is clear that GSK-3 kinases regulate many aspects of precursor lesion initiation, high-grade tumor development, progression, cancer cell metastasis and chemoresistance. Thus, combining GSK-3 inhibitors with chemotherapies that induce single-stranded DNA damage could offer a promising therapeutic strategy for this tumor, as well as other human cancers.

One major concern regarding the utilization of GSK-3 inhibitors long term, is the fact that these kinases do negatively regulate the activity of known oncogenes including c-Myc, c-Jun and of course β-catenin. Importantly, a recent study tested over 300 kinase inhibitors and found that the GSK-3 inhibitor SB-7328810-H (SB) had the highest selectivity for inhibiting the viability of the mutant KRas-dependent pancreatic cancer cell line MiaPaCa2. Interestingly, SB treatment resulted in diminished phosphorylation of c-Myc and β-catenin leading to increased protein levels [82]. Surprisingly, the authors found that CRISPR/Cas9-mediated deletion of β-catenin or c-Myc prevented the apoptosis induced by SB treatment [82]. While the effect of GSK-3 inhibition might be tumor-type specific, it is not clear what the effects of chronic GSK-3 inhibition on normal tissues and stem cell populations will be. However, like other targeted therapies (e.g., c-Abl, EGFR) where the target plays a prominent role in organismal and tissue development/homeostasis, cancer cells might be more sensitive to the inhibitor than normal cells and tissues, thus providing a therapeutic window. Moreover, chronic long-standing administration of a GSK-3 inhibitor will not be necessary as these inhibitors are likely to be used intermittently over short periods of time.

As more research is done using clinically-relevant GSK-3 inhibitors, it is very likely that new roles for GSK-3 kinases in pancreatic cancer therapy, especially immunotherapy will be uncovered. Cancer immunotherapy has become a promising therapeutic option in a variety of malignancies, including pancreatic cancer. As reviewed by Kunk et al [83], there are a full spectrum of completed or on-going immunotherapy clinical trials that are designed for targeting both suppressor immune cells and the dense extracellular matrix in pancreatic cancer. But according to the report from Cristescu et al [84], only those patients expressing high levels of microsatellite instability (MSI-H) have both high tumor mutational burden and T-cell-inflamed gene expression profile (GEPhiTMBhi) and are predicted to have the strongest response to PD-1 checkpoint blockade. In regard to GSK-3 regulation of immune checkpoints, several recent studies have demonstrated that GSK-3 kinases are positive regulators of the immune checkpoint molecules PD-1 and LAG-3 in T cells (85, 86, 87). Indeed, treatment of mice with GSK-3 inhibitors suppressed B16 and EL-4 tumor growth in vivo in part by down-regulating the expression of PD-1 and LAG-3 on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and increasing the expression of granzyme B and interferon-γ in exhausted CD8+ T cells (87). Additionally, GSK-3i treatment of CAR-T cells was shown to decrease activation-induced cell death, diminish PD-1 expression and promote an effector memory phenotype, which protected mice from tumor re-challenge (88). Taken together, these studies suggest that immunotherapies in many cancers using either immune checkpoint blockade or CAR-T cell approaches could benefit from the addition of GSK-3 inhibition.

Progressive fibrosis mediated by cancer-associated fibroblasts responding to TGFβ signaling is a hallmark of PDAC, and is a major contributor to the profibrotic/anti-angiogenic TME which impairs chemotherapeutic perfusion into the tumor [89]. Thus, identifying ways in which to target the tumor microenvironment in PDAC could facilitate drug delivery and efficacy. To this end, it was recently identified that GSK-3 kinases promote the development of pulmonary fibrosis by positively regulating TGFβ-induced myofibroblast differentiation in vitro and in vivo [90]. Significantly, mice with TGFβ- or bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis showed improved lung function following treatment with the GSK-3 inhibitor 9-ING-41. This is not only interesting as it pertains to the potential resolution of the desmoplasia in PDAC, but also in regard to the effects of GSK-3 inhibition on the regulation of TGFβ signaling, since this cytokine not only regulates fibrosis, but also the generation of suppressive immune cells such as Tregs, myeloid-derived suppressor cells and tumor-associated macrophages. Whether GSK-3 inhibition could also be used to modulate these aspects of the suppressive PDAC tumor immune microenvironment will be very interesting.

Lastly, it is now well appreciated that around 12% of PDAC patient’s tumors bear DNA repair defects that affect homologous recombination repair due to either inherited or somatic mutations in a number of genes involved in this repair pathway such as BRCA1, BRCA2, ATM, and PALB2 [91]. Tumors bearing these mutations are sensitive to PARP inhibitors when combined with chemotherapy [92]. It remains possible that blocking the ATR pathway using a GSK-3 inhibitor might further sensitize these tumors when combined with a PARP inhibitor and chemotherapy, as it will remove another possible DNA repair escape mechanism. However, single-agent drug treatment has shown that cancer cells can quickly adapt by activating compensatory signaling pathways [93]. For example, in a recent study from Vaseva et al., the authors identified that an EGFR- and SRC-dependent feed-forward mechanism was induced following ERK1/2-inhibition, leading to the stabilization of MYC by activated ERK5 [94, 95]. A high-throughput and kinome-wide proteomics screen combined with accurate patient profiling should be applied to provide in-depth information of any possible pathway redundancy or feedback that could contribute to GSK-3 inhibitor resistance in pancreatic cancer.

Article highlights.

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is the most common type of pancreatic cancer. It is the third but will become the second leading cause of adult cancer death in the United States by 2030.

PDAC is still an incurable lethal disease primarily due to the advanced stage at diagnosis and extremely poor response rate to conventional therapies. Activating mutations of KRas represent the earliest and most common genetic alteration and play an essential role in initiating and promoting PDAC, but there are no effective RAS inhibitors available after three decades of intense effort.

GSK-3α and GSK-3β are conserved serine/threonine kinases that have been implicated in regulating multiple cellular pathways that are critical to normal cellular/organismal homeostasis and tumor development, progression and metastasis.

GSK-3β is overexpressed in PDAC and is negatively associated with shorter survival of PDAC patients.

Oncogenic KRas signaling activates the expression of GSK-3β and GSK-3β has a prominent role as tumor promotor and regulator of sustaining PDAC cell proliferation and viability. Inhibition of GSK-3β activity impairs PDAC cell growth, survival and drug sensitivity by impacting key targets like NF-κB, NFAT, Rb, TAK, GLl1 and TopBP1.

Several GSK-3 inhibitors have been developed, but at present, only 9-ING-41 is in a phase Ia/b clinical trial that includes patients with PDAC.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by a Fellowship Grant from the Eagles 5th District Cancer Telethon Funds for Cancer Research and the Center for Biomedical Discovery to L Ding and an NCI supported Pancreatic Cancer SPORE grant CA102701 to DD Billadeau.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

DD Billadeau serves on the Scientific Advisory Board of Actuate Therapeutics Inc. and holds equity interest in Actuate Therapeutics Inc. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer Disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest (•) or of considerable interest (••) to readers.

- 1.Garrido-Laguna I, Hidalgo M. Pancreatic cancer: from state-of-the-art treatments to promising novel therapies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2015. June;12(6):319–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R, et al. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res 2014. June 1;74(11):2913–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2019. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith BD, Smith GL, Hurria A, et al. Future of cancer incidence in the United States: burdens upon an aging, changing nation. J Clin Oncol 2009. June 10;27(17):2758–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim MP, Gallick GE. Gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic cancer: picking the key players. Clin Cancer Res 2008. March 1;14(5):1284–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *6.Cormier KW, Woodgett JR. Recent advances in understanding the cellular roles of GSK-3. F1000Res 2017;6.This reference is the latest review article from Dr. James Woodgett, who first cloned GSK-3 kinases and this review provides a broader overview of GSK-3 kinases and their roles in regulating numerous intracellular signaling cascades.

- **7.Ougolkov AV, Fernandez-Zapico ME, Bilim VN, et al. Aberrant nuclear accumulation of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta in human pancreatic cancer: association with kinase activity and tumor dedifferentiation. Clin Cancer Res 2006. September 1;12(17):5074–81.This reference is one of the first papers suggesting the tumor promoting role of GSK-3β in pancreatic cancer and provides evidence highlighting the importance of kinase activity and cellular localization of GSK-3β to pancreatic tumor development and dedifferentiation.

- 8.Xie Y, Zhu S, Zhong M, et al. Inhibition of Aurora Kinase A Induces Necroptosis in Pancreatic Carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2017. November;153(5):1429–43 e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ding L, Liou GY, Schmitt DM, et al. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta ablation limits pancreatitis-induced acinar-to-ductal metaplasia. J Pathol 2017. September;243(1):65–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcea G, Manson MM, Neal CP, et al. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta; a new target in pancreatic cancer? Curr Cancer Drug Targets 2007. May;7(3):209–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baumgart S, Chen NM, Zhang JS, et al. GSK-3beta Governs Inflammation-Induced NFATc2 Signaling Hubs to Promote Pancreatic Cancer Progression. Mol Cancer Ther 2016. March;15(3):491–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **12.Ding L, Madamsetty VS, Kiers S, et al. Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3 Inhibition Sensitizes Pancreatic Cancer Cells to Chemotherapy by Abrogating the TopBP1/ATR-Mediated DNA Damage Response. Clin Cancer Res 2019. September 18: published online 18 Sep 2019, DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0799.This reference examines and establishes the previously unknown role of GSK-3 kinases in regulating the ATR DNA damage response and provides valuable pre-clinical data for combining the GSK-3 inhibitor 9-ING-41 with chemotherapies that induce single-stranded DNA damage in pancreatic cancer patients

- 13.Embi N, Rylatt DB, Cohen P. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 from rabbit skeletal muscle. Separation from cyclic-AMP-dependent protein kinase and phosphorylase kinase. Eur J Biochem 1980. June;107(2):519–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woodgett JR. Molecular cloning and expression of glycogen synthase kinase-3/factor A. EMBO J 1990. August;9(8):2431–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doble BW, Woodgett JR. GSK-3: tricks of the trade for a multi-tasking kinase. J Cell Sci 2003. April 1;116(Pt 7):1175–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaidanovich-Beilin O, Woodgett JR. GSK-3: Functional Insights from Cell Biology and Animal Models. Front Mol Neurosci 2011;4:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jope RS, Yuskaitis CJ, Beurel E. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3): inflammation, diseases, and therapeutics. Neurochem Res 2007. Apr-May;32(4–5):577–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grimes CA, Jope RS. The multifaceted roles of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta in cellular signaling. Prog Neurobiol 2001. November;65(4):391–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sutherland C What Are the bona fide GSK3 Substrates? Int J Alzheimers Dis 2011;2011:505607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linding R, Jensen LJ, Ostheimer GJ, et al. Systematic discovery of in vivo phosphorylation networks. Cell 2007. June 29;129(7):1415–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alon LT, Pietrokovski S, Barkan S, et al. Selective loss of glycogen synthase kinase-3alpha in birds reveals distinct roles for GSK-3 isozymes in tau phosphorylation. FEBS Lett 2011. April 20;585(8):1158–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoeflich KP, Luo J, Rubie EA, et al. Requirement for glycogen synthase kinase-3beta in cell survival and NF-kappaB activation. Nature 2000. July 6;406(6791):86–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walz A, Ugolkov A, Chandra S, et al. Molecular Pathways: Revisiting Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3beta as a Target for the Treatment of Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2017. April 15;23(8):1891–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ougolkov AV, Fernandez-Zapico ME, Savoy DN, et al. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta participates in nuclear factor kappaB-mediated gene transcription and cell survival in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res 2005. March 15;65(6):2076–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris JPT, Wang SC, Hebrok M. KRAS, Hedgehog, Wnt and the twisted developmental biology of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat Rev Cancer 2010. October;10(10):683–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanda M, Matthaei H, Wu J, et al. Presence of somatic mutations in most early-stage pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Gastroenterology 2012. April;142(4):730–33 e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *27.Zhang JS, Koenig A, Harrison A, et al. Mutant K-Ras increases GSK-3beta gene expression via an ETS-p300 transcriptional complex in pancreatic cancer. Oncogene 2011. August 25;30(34):3705–15.(This reference shows for the first time the direct relationship between GSK-3β gene transcription and signaling pathways activated by oncogenic Ras signaling.)

- 28.Bang D, Wilson W, Ryan M, et al. GSK-3alpha promotes oncogenic KRAS function in pancreatic cancer via TAK1-TAB stabilization and regulation of noncanonical NF-kappaB. Cancer Discov 2013. June;3(6):690–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson JL, Dia VP, Wallig M, Gonzalez de Mejia E. Luteolin and Gemcitabine Protect Against Pancreatic Cancer in an Orthotopic Mouse Model. Pancreas 2015. January;44(1):144–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fitzgerald TL, Lertpiriyapong K, Cocco L, et al. Roles of EGFR and KRAS and their downstream signaling pathways in pancreatic cancer and pancreatic cancer stem cells. Adv Biol Regul 2015. September;59:65–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCubrey JA, Steelman LS, Bertrand FE, et al. GSK-3 as potential target for therapeutic intervention in cancer. Oncotarget 2014. May 30;5(10):2881–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Domoto T, Pyko IV, Furuta T, et al. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta is a pivotal mediator of cancer invasion and resistance to therapy. Cancer Sci 2016. October;107(10):1363–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woodgett JR. Regulation and functions of the glycogen synthase kinase-3 subfamily. Semin Cancer Biol 1994. August;5(4):269–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCubrey JA, Davis NM, Abrams SL, et al. Diverse roles of GSK-3: tumor promoter-tumor suppressor, target in cancer therapy. Adv Biol Regul 2014. January;54:176–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Billadeau DD. Primers on molecular pathways. The glycogen synthase kinase-3beta. Pancreatology 2007;7(5–6):398–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mancinelli R, Carpino G, Petrungaro S, et al. Multifaceted Roles of GSK-3 in Cancer and Autophagy-Related Diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017;2017:4629495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mai W, Kawakami K, Shakoori A, et al. Deregulated GSK3β sustains gastrointestinal cancer cells survival by modulating human telomerase reverse transcriptase and telomerase. Clin Cancer Res 2009. November 15;15(22):6810–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou W, Wang L, Gou SM, et al. ShRNA silencing glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta inhibits tumor growth and angiogenesis in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Lett 2012. March 28;316(2):178–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beurel E, Grieco SF, Jope RS. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3): regulation, actions, and diseases. Pharmacol Ther 2015. April;148:114–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mohamad NA, Cricco GP, Cocca CM, et al. PANC-1 cells proliferative response to ionizing radiation is related to GSK-3beta phosphorylation. Biochem Cell Biol 2012. December;90(6):779–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sarkar S, Mandal C, Sangwan R, Mandal C. Coupling G2/M arrest to the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway restrains pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Endocr Relat Cancer 2014. February;21(1):113–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu L, Liu Y, Liu X, et al. Resibufogenin suppresses transforming growth factor-beta-activated kinase 1-mediated nuclear factor-kappaB activity through protein kinase C-dependent inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase 3. Cancer Sci 2018. November;109(11):3611–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soltek S, Karakhanova S, Golovastova M, et al. Anti-tumor properties of the cGMP/protein kinase G inhibitor DT3 in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2015. November;388(11):1121–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu D, Pan W. GSK3: a multifaceted kinase in Wnt signaling. Trends Biochem Sci 2010. March;35(3):161–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jones S, Zhang X, Parsons DW, et al. Core signaling pathways in human pancreatic cancers revealed by global genomic analyses. Science 2008. September 26;321(5897):1801–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.White BD, Chien AJ, Dawson DW. Dysregulation of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in gastrointestinal cancers. Gastroenterology 2012. February;142(2):219–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kitano A, Shimasaki T, Chikano Y, et al. Aberrant glycogen synthase kinase 3beta is involved in pancreatic cancer cell invasion and resistance to therapy. Plos One 2013;8(2):e55289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bhat RV, Shanley J, Correll MP, et al. Regulation and localization of tyrosine216 phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta in cellular and animal models of neuronal degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000. September 26;97(20):11074–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang JS, Herreros-Villanueva M, Koenig A, et al. Differential activity of GSK-3 isoforms regulates NF-kappaB and TRAIL- or TNFalpha induced apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells. Cell Death Dis 2014. March 27;5:e1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou A, Lin K, Zhang S, et al. Nuclear GSK3beta promotes tumorigenesis by phosphorylating KDM1A and inducing its deubiquitylation by USP22. Nat Cell Biol 2016. September;18(9):954–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *51.Gaisina IN, Gallier F, Ougolkov AV, et al. From a natural product lead to the identification of potent and selective benzofuran-3-yl-(indol-3-yl)maleimides as glycogen synthase kinase 3beta inhibitors that suppress proliferation and survival of pancreatic cancer cells. J Med Chem 2009. April 9;52(7):1853–63.This reference provides the chemical description of the GSK-3i from which 9-ING-41 was derived, and the effect of this chemical on pancreatic cancer cell proliferation and survivial.

- 52.Diehl JA, Cheng M, Roussel MF, Sherr CJ. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta regulates cyclin D1 proteolysis and subcellular localization. Genes Dev 1998. November 15;12(22):3499–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peng Z, Ji Z, Mei F, et al. Lithium inhibits tumorigenic potential of PDA cells through targeting hedgehog-GLI signaling pathway. Plos One 2013;8(4):e61457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Neal JW, Clipstone NA. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibits the DNA binding activity of NFATc. J Biol Chem 2001. February 2;276(5):3666–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Singh SK, Baumgart S, Singh G, et al. Disruption of a nuclear NFATc2 protein stabilization loop confers breast and pancreatic cancer growth suppression by zoledronic acid. J Biol Chem 2011. August 19;286(33):28761–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Azzolin L, Zanconato F, Bresolin S, et al. Role of TAZ as mediator of Wnt signaling. Cell 2012. December 21;151(7):1443–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Santoro R, Zanotto M, Simionato F, et al. Modulating TAK1 expression inhibits YAP and TAZ oncogenic functions in pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 2019. September 27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Shin S, Wolgamott L, Yu Y, et al. Glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)-3 promotes p70 ribosomal protein S6 kinase (p70S6K) activity and cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011. November 22;108(47):E1204–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Adamska A, Domenichini A, Falasca M. Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: Current and Evolving Therapies. Int J Mol Sci 2017. June 22;18(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carbone C, Melisi D. NF-kappaB as a target for pancreatic cancer therapy. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2012. April;16 Suppl 2:S1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wilson W 3rd, Baldwin AS. Maintenance of constitutive IkappaB kinase activity by glycogen synthase kinase-3alpha/beta in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res 2008. October 1;68(19):8156–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Marchand B, Tremblay I, Cagnol S, Boucher MJ. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 activity triggers an apoptotic response in pancreatic cancer cells through JNK-dependent mechanisms. Carcinogenesis 2012. March;33(3):529–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shimasaki T, Ishigaki Y, Nakamura Y, et al. Glycogen synthase kinase 3beta inhibition sensitizes pancreatic cancer cells to gemcitabine. J Gastroenterol 2012. March;47(3):321–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mamaghani S, Patel S, Hedley DW. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibition disrupts nuclear factor-kappaB activity in pancreatic cancer, but fails to sensitize to gemcitabine chemotherapy. BMC Cancer 2009. April 30;9:132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Elmaci I, Altinoz MA. A Metabolic Inhibitory Cocktail for Grave Cancers: Metformin, Pioglitazone and Lithium Combination in Treatment of Pancreatic Cancer and Glioblastoma Multiforme. Biochem Genet 2016. October;54(5):573–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **66.Edderkaoui M, Chheda C, Soufi B, et al. An Inhibitor of GSK3B and HDACs Kills Pancreatic Cancer Cells and Slows Pancreatic Tumor Growth and Metastasis in Mice. Gastroenterology 2018. December;155(6):1985–98 e5.(This reference describes a novel dual GSK3-HDAC2 inhibitor that impairs PDAC cell proliferation and migration in vitro as well as tumor progression and metastasis in the KPC mouse model.)

- 67.Ugolkov A, Gaisina I, Zhang JS, et al. GSK-3 inhibition overcomes chemoresistance in human breast cancer. Cancer Lett 2016. October 1;380(2):384–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pal K, Cao Y, Gaisina IN, et al. Inhibition of GSK-3 induces differentiation and impaired glucose metabolism in renal cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 2014. February;13(2):285–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ugolkov AV, Bondarenko GI, Dubrovskyi O, et al. 9-ING-41, a small-molecule glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibitor, is active in neuroblastoma. Anticancer Drugs 2018. September;29(8):717–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wu XS, Stenson M, Abeykoon J, Nowakowski K, Zhang LW, Lawson J, et al. Targeting glycogen synthase kinase 3 for therapeutic benefit in lymphoma. Blood 2019. July 25;134(4):363–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kuroki H, Anraku T, Kazama A, et al. 9-ING-41, a small molecule inhibitor of GSK-3beta, potentiates the effects of anticancer therapeutics in bladder cancer. Sci Rep-Uk 2019. December 27;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med 2013. October 31;369(18):1691–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ying X, Jing L, Ma S, et al. GSK3beta mediates pancreatic cancer cell invasion in vitro via the CXCR4/MMP-2 Pathway. Cancer Cell Int 2015;15:70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Meng Q, Shi S, Liang C, et al. Abrogation of glutathione peroxidase-1 drives EMT and chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer by activating ROS-mediated Akt/GSK3beta/Snail signaling. Oncogene 2018. November;37(44):5843–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cannito S, Novo E, Compagnone A, et al. Redox mechanisms switch on hypoxia-dependent epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer cells. Carcinogenesis 2008. December;29(12):2267–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liu A, Shao C, Jin G, et al. miR-208-induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition of pancreatic cancer cells promotes cell metastasis and invasion. Cell Biochem Biophys 2014. June;69(2):341–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liu QQ, Chen K, Ye Q, et al. Oridonin inhibits pancreatic cancer cell migration and epithelial-mesenchymal transition by suppressing Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. Cancer Cell Int 2016;16:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 2004. January 23;116(2):281–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sun L, Chua CYX, Tian W, et al. MicroRNA Signaling Pathway Network in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. J Genet Genomics 2015. October 20;42(10):563–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yang HW, Liu GH, Liu YQ, et al. Over-expression of microRNA-940 promotes cell proliferation by targeting GSK3beta and sFRP1 in human pancreatic carcinoma. Biomed Pharmacother 2016. October;83:593–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhou W, Li Y, Gou S, et al. MiR-744 increases tumorigenicity of pancreatic cancer by activating Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. Oncotarget 2015. November 10;6(35):37557–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kazi A, Xiang S, Yang H, et al. GSK3 suppression upregulates beta-catenin and c-Myc to abrogate KRas-dependent tumors. Nat Commun 2018. December 4;9(1):5154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kunk PR, Bauer TW, Slingluff CL, Rahma OE. From bench to bedside a comprehensive review of pancreatic cancer immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer 2016;4:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cristescu R, Mogg R, Ayers M, et al. Pan-tumor genomic biomarkers for PD-1 checkpoint blockade-based immunotherapy. Science 2018. October 12;362(6411). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **85.Taylor A, Harker JA, Chanthong K, et al. Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 Inactivation Drives T-bet-Mediated Downregulation of Co-receptor PD-1 to Enhance CD8(+) Cytolytic T Cell Responses. Immunity 2016. February 16;44(2):274–86.This reference establishes for the first time that GSK-3 inhibitors have the potential to modulate the expression of PD-1 and thus could be used alone or in combination with immune checkpoint blockade to enhance anti-tumor immunity.

- 86.Taylor A, Rothstein D, Rudd CE. Small-Molecule Inhibition of PD-1 Transcription Is an Effective Alternative to Antibody Blockade in Cancer Therapy. Cancer Research 2018. February 1;78(3):706–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rudd CE, Chanthong K, Taylor A. Small Molecule Inhibition of GSK-3 Specifically Inhibits the Transcription of Inhibitory Co-receptor LAG-3 for Enhanced Anti-tumor Immunity. Cell Rep 2020. February 18;30(7):2075–82 e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sengupta S, Katz SC, Sengupta S, Sampath P. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 inhibition lowers PD-1 expression, promotes long-term survival and memory generation in antigen-specific CAR-T cells. Cancer Lett 2018. October 1;433:131–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Olive KP, Jacobetz MA, Davidson CJ, et al. Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling enhances delivery of chemotherapy in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Science 2009. June 12;324(5933):1457–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **90.Jeffers A, Qin W, Owens S, et al. Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3beta Inhibition with 9-ING-41 Attenuates the Progression of Pulmonary Fibrosis. Sci Rep 2019. December 12;9(1):18925.This reference reveals the importance of GSK-3 signaling for myofibroblast activation and differentiation in lung fibrosis and provides a strong rationale for testing GSK-3 inhibitors in modulating desmoplasia of pancreatic cancer.

- *91.Roberts NJ, Norris AL, Petersen GM, et al. Whole Genome Sequencing Defines the Genetic Heterogeneity of Familial Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Discov 2016. February;6(2):166–75.This reference determines the genetic basis of familiar pancreatic cancer susceptibility genes and has important implications for genetic screening in newly diagnosed pancreatic cancer patients with potential benefit combination therapy targeting DNA repair pathway.

- 92.Pihlak R, Valle JW, McNamara MG. Germline mutations in pancreatic cancer and potential new therapeutic options. Oncotarget 2017. September 22;8(42):73240–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Logue JS, Morrison DK. Complexity in the signaling network: insights from the use of targeted inhibitors in cancer therapy. Genes Dev 2012. April 1;26(7):641–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Vaseva AV, Blake DR, Gilbert TSK, et al. KRAS Suppression-Induced Degradation of MYC Is Antagonized by a MEK5-ERK5 Compensatory Mechanism. Cancer Cell 2018. November 12;34(5):807–22 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hayes TK, Neel NF, Hu C, et al. Long-Term ERK Inhibition in KRAS-Mutant Pancreatic Cancer Is Associated with MYC Degradation and Senescence-like Growth Suppression. Cancer Cell 2016. January 11;29(1):75–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]