Abstract

Objective

With decreasing mortality in pediatric intensive care units (PICUs), a growing number of survivors experience long-lasting physical impairments. Early physical rehabilitation and mobilization during critical illness is safe and feasible, but little is known about the prevalence in PICUs. We aimed to evaluate the prevalence of rehabilitation for critically ill children and associated barriers.

Design

National 2-day point prevalence study.

Setting

82 PICUs in 65 hospitals across the United States.

Patients

All patients admitted to a participating PICU for ≥72 hours on each point prevalence day.

Interventions

None.

Measurements and Main Results

The primary outcome was prevalence of physical therapy (PT)- or occupational therapy (OT)-provided mobility on the study days. PICUs also prospectively collected timing of initial rehabilitation team consultation, clinical and patient mobility data, potential mobility-associated safety events, and barriers to mobility. The point prevalence of PT- or OT-provided mobility during 1769 patient-days was 35% and associated with older age (aOR for 13–17 vs. <3 years: 2.1; 95% CI, 1.5–3.1) and male gender (aOR for females, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.61–0.95). Patients with higher baseline function (PCPC ≤2 vs. >2) less often had rehabilitation consultation within the first 72 hours (27% vs. 38%; P<0.001). Patients were completely immobile on 19% of patient-days. A potential safety event occurred in only 4% of 4,700 mobility sessions, most commonly a transient change in vital signs. Out-of-bed mobility was negatively associated with presence of an endotracheal tube (aOR, 0.13; 95% CI, 0.1–0.2) and urinary catheter (aOR, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.1–0.6). Positive associations included family presence in children <3 years old (aOR, 4.55; 95% CI, 3.1–6.6).

Conclusions

Younger children, females and patients with higher baseline function less commonly receive rehabilitation in U.S. PICUs, and early rehabilitation consultation is infrequent. These findings highlight the need for systematic design of rehabilitation interventions for all critically ill children at risk of functional impairments.

Keywords: critical care, pediatrics, rehabilitation, physical therapy, occupational therapy, developmental pediatrics, intensive care units

INTRODUCTION

Resuscitation and reversal of organ failure are important aspects of patient management in the intensive care unit (ICU). Deep sedation and bedrest are common because of clinician perceptions of improved patient safety, physiological stability, and patient comfort. However, deep sedation and bedrest are associated with short-term harms, including pressure ulcers, muscle weakness, and venous thromboembolism (1–5). Survivors of critical illness also commonly experience long-term physical, cognitive, and psychological morbidities (6–8). These issues are compounded in the pediatric ICU (PICU) given that critical illness is occurring during a period of intense physical and neurocognitive development in infancy and childhood (9–11). Growing numbers of children who survive acute critical illness face high technological dependence (12), prolonged PICU stays (13, 14), and long-term morbidities (15, 16).

Early rehabilitation and mobility in adult ICUs is associated with improved muscle strength (1, 17) and physical functioning (17), along with decreased mechanical ventilation duration (1). Despite this evidence, point prevalence studies in adult ICUs have consistently demonstrated that physical rehabilitation is infrequent (18–21). In critically ill children, early rehabilitation and mobility is safe and feasible, with potential short- and long-term benefits (22). However, the current state of rehabilitation practices in PICUs is unknown.

Hence, we conducted a two-day point prevalence study in 82 PICUs across the United States (U.S.) to determine the prevalence of physical rehabilitation and mobility for patients admitted for at least 3 days. Additionally, we evaluated perceived barriers and potential safety events for patient mobility.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

PARK-PICU (Prevalence of Acute Rehabilitation for Kids in the PICU) was a cross-sectional point prevalence study conducted in U.S. PICUs on two days (November 9, 2017, and February 12, 2018). PICUs in the U.S. were eligible to participate if they (1) cared for mechanically ventilated infants and children and (2) were located in a distinct physical space dedicated to pediatric patients. PICUs were recruited via the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators (PALISI) network, e-mail, social media, and a dedicated website (23). Institutional review board approval was obtained at all sites with waiver of informed consent for collection of de-identified data.

Patient Selection

All patients with PICU length of stay (LOS) ≥72 hours as of 7 a.m. on each point prevalence day were included in the study. We chose ≥72 hours because patients with longer stays are at greater risk for muscle atrophy and physical impairment (24), and ICU studies suggest up to 72 hours as the threshold for defining “early” rehabilitation and mobilization (22, 25, 26).

Study Day Selection, Notification, and Data Collection

At the time of site enrollment, participating PICU study teams were informed of the designated months for the point prevalence study days. On the first day of the month, a clinician who was not involved with the study randomly chose a weekday for study conduct in all PICUs. Study teams were notified by text and/or email at 3 p.m. EST on the day before the selected day, with instructions to conduct screening for eligible patients and prepare for data collection on the following day. Prospective data collection began at 9 a.m. for all eligible patients and continued for 24 hours. All data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic capture tools hosted at Johns Hopkins University (27, 28). All data collection forms are publicly available on the study website (29).

Measures

ICU Characteristics

Prior to study initiation, each participating ICU (n=82) completed an organizational survey (29) to provide data regarding clinical resources and protocols related to rehabilitation and mobility. Site principal investigators were instructed to complete this survey in collaboration with a rehabilitation team leader and the PICU nurse manager to ensure accuracy.

Patient Clinical Characteristics

Sites abstracted clinical data (29) for all eligible patients based on clinical status at 9 a.m. on each study day. Data included mechanical ventilation status, sedative infusions and sedation level, delirium status, and use of specific medical devices. Mechanical ventilation was defined as positive pressure ventilation delivered via an endotracheal tube, tracheostomy, or noninvasive ventilation. Pre-admission functional status, categorized by the Pediatric Cerebral Performance Score (PCPC), was collected based on the medical record or discussion with family and PICU team. Data were collected from the electronic health record, or in real-time at the bedside, based on site preference and data availability.

Mobility Data

Physical therapy (PT) and occupational therapy (OT) consultation and treatment documentation for the first 72 hours of PICU admission were abstracted retrospectively from the electronic health record. For mobility data, standardized forms (29) were distributed to the bedside of all eligible patients by 9 a.m. for real-time event recording. Nurses and multidisciplinary staff were instructed to document the following: (1) occurrence of any PT-, OT-, nurse-, family- or other staff-provided mobility on the study day; (2) types and timing of mobility events (classified according to in-bed and out-of-bed activities); (3) perceived barriers to mobilization; and (4) potential safety events associated with mobilization (e.g., transient vital sign changes defined as ≥10% change in heart rate, oxygen saturation, or blood pressure; loss of invasive devices; falls). Mobility events were defined as any activity involving physical movement of the patient, with the exception of routine care, including turning/repositioning for delivery of medical care or prevention of pressure ulcers. Both barriers and potential safety events were selected from a pre-specified list with a free-text option (29).

The primary outcome was “therapist-provided mobility,” defined as ≥1 mobility event performed by either a PT or OT on the study day. This primary outcome was chosen based on: 1) comparability to U.S. adult ICU point prevalence data, (18) and 2) feedback from participating PICUs that PT and OTs are often consulted simultaneously and the rehabilitation team determines which services are most appropriate to provide. Out-of-bed mobility was defined as transfer from bed to chair, being held by family or staff, mat play, standing or walking. Secondary outcomes were out-of-bed mobility, barriers to mobility, and potential safety events. We also analyzed PT- and OT-provided mobility separately.

Data Analysis/Statistical Methods

The prevalences of therapist-provided mobility and out-of-bed mobility were defined as the number of patient-days with at least one associated event divided by the total eligible patient-days across the two study days. Categorical data were analyzed by chi-squared test, and continuous data (expressed as medians [interquartile range (IQR)]) were analyzed by the Mann-Whitney U test. Patients discharged before 12 p.m. on the study days were excluded from the final analysis. Multivariable logistic regression models, with a random effect for ICU site, were used to calculate odds ratios (ORs), with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), for therapist-provided mobility and out-of-bed mobility.

Covariates in the regression models were identified a priori based on clinical relevance and prior literature (30). The regression model for therapist-provided mobility included age category (0–2, 3–6, 7–12, 13–18, >18 years); sex; ethnicity; baseline PCPC before hospital admission; PICU LOS as of the study day; medical vs. surgical admission; type of respiratory support; vasoactive, opioid, and benzodiazepine infusions; nurse:patient ratio; indwelling urinary catheter; central venous or arterial catheters; hemodialysis catheter; intracranial pressure monitor; unit mobility protocol; and family presence. The regression model for out-of-bed mobility included these variables in addition to a binary indicator of therapist-provided mobility on the study day. Additional details for data analysis and statistical methods are provided in Supplemental Digital Content 1. A two-tailed P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Stata 14 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX) was used for all statistical analysis.

RESULTS

ICU and Patient Baseline Characteristics

Participating PICUs (n=82; Supplemental Digital Content 2 and 3) had a median of 24 beds (IQR, 16–30) and included medical-surgical-cardiac (44%), medical-surgical (40%), and cardiac only (16%) units. Most PICUs were in an academic teaching (92%) and free-standing children’s hospital (55%). Early mobility protocols were reported in 27% of units. A physician consultation request was required for evaluation and treatment by a PT or OT in 93% of PICUs. A dedicated full-time equivalent (≥1 FTE) PT and OT staff were present in 18% and 16% of PICUs, respectively.

Among 3,098 patients screened over two study days, 1769 (57%) met inclusion criteria (Supplemental Digital Content 4); 74 (4%) patients contributed data on both study days. Most were medical patients (73%), <3 years old (61%), with a median (IQR) PICU stay of 12 (6–30) days, and 48% had a baseline PCPC score >2 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Patient Baseline Characteristics, by Physical Therapy–/Occupational Therapy–Provided Mobility on Study Day

| Demographics | All Patient-Days n = 1,769 | PT/OT-Provided Mobility n = 625 | No PT/OT-Provided Mobility n = 1,144 | pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr), n (%) | 0.006 | |||

| 0–2 | 1,100 (62) | 355 (57) | 745 (65) | |

| 3–6 | 196 (11) | 71 (11) | 125 (11) | |

| 7–12 | 220 (12) | 90 (14) | 130 (11) | |

| 13–17 | 195 (11) | 83 (13) | 112 (10) | |

| > 18 | 58 (3) | 26 (4) | 32 (3) | |

| Female, n (%) | 767 (43) | 247 (40) | 520 (46) | 0.02 |

| Ethnicity, n (%)b | 0.10 | |||

| White | 864 (49) | 324 (52) | 540 (48) | |

| Black | 397 (23) | 141 (23) | 256 (23) | |

| Hispanic | 76 (4) | 30 (5) | 46 (4) | |

| Asian | 295 (17) | 94 (15) | 201 (18) | |

| Other | 130 (7) | 35 (6) | 95 (8) | |

| Body mass index, median (IQR)b | 17 (15–20) | 17 (15–21) | 17 (15–20) | 0.07 |

| PICU length of stay, median (IQR) | 12 (6–30) | 16 (7–41) | 10 (6–25) | 0.007 |

| Preadmission function, n (%)c | < 0.001 | |||

| 1: good | 455 (26) | 140 (22) | 315 (28) | |

| 2: mild disability | 472 (27) | 177 (28) | 295 (26) | |

| 3: moderate disability | 380 (22) | 167 (27) | 213 (19) | |

| 4: severe disability | 442 (25) | 137 (22) | 305 (27) | |

| 5: coma/vegetative state | 20 (1) | 4 (1) | 16 (1) | |

| Ambulatory before admission, if age ≥ 3, n (%)a | 424 (63) | 209 (77) | 215 (54) | <0.001 |

| Primary admission reason, n (%)b | 0.10 | |||

| Surgical | ||||

| Cardiac | 274 (16) | 96 (15) | 178 (16) | |

| Neurologic | 85 (5) | 42 (7) | 43 (4) | |

| Orthopedic | 8 (1) | 4 (0) | 4 (0) | |

| Other | 101 (6) | 33 (5) | 68 (6) | |

| Medical | ||||

| Respiratory | 671 (38) | 207 (33) | 464 (41) | |

| Cardiac | 282 (16) | 109 (17) | 173 (15) | |

| Hematology-oncology | 40 (2) | 19 (3) | 21 (2) | |

| Infectious/inflammatory | 104 (6) | 36 (6) | 68 (6) | |

| Neurologic | 103 (6) | 42 (7) | 61 (5) | |

| Other | 97 (5) | 37 (6) | 60 (5) | |

| Early mobility protocold | 468 (26) | 191 (31) | 277 (24) | 0.004 |

IQR = interquartile range, OT = occupational therapy, PT = physical therapy.

Calculated using χ2 test for categorical variables and Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables.

Missing data: ethnicity (n = 7); body mass index (n = 84); admission reason (n = 6).

Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category.

Defined as unit-based guideline or policy for early mobility.

Patient Clinical Characteristics on Study Day

About half of all eligible patients were receiving ≥1 continuous infusion of a sedative or analgesic, and 59% of all patients were mechanically ventilated (Table 2); 87% (n=529) of all intubated patients received a continuous analgesic and/or sedative infusion. Most patients had a central venous catheter (67%; n=1189), and 371 (21%) received a vasoactive infusion.

TABLE 2.

Patient Clinical Characteristics on Study Day, by Physical Therapy–/Occupational Therapy–Provided Mobility Status

| Clinical Characteristic on Study Day | All n = 1,769 | PT/OT-Provided Mobility n = 625 | No PT/OT-Provided Mobility n = 1,144 | pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory support, n (%)b | < 0.001 | |||

| No support | 312 (18) | 127 (20) | 185 (16) | |

| Nasal cannula or face mask | 166 (9) | 75 (12) | 91 (8) | |

| High-flow nasal cannula or RAM cannula | 209 (12) | 71 (11) | 138 (12) | |

| Tracheostomy collar | 38 (2) | 17 (3) | 21 (2) | |

| Mechanical ventilation–noninvasive | 167 (9) | 62 (10) | 105 (9) | |

| Mechanical ventilation–tracheostomy | 260 (15) | 109 (17) | 151 (13) | |

| Mechanical ventilation–endotracheal | 611 (35) | 162 (26) | 449 (39) | |

| Fio2, median (IQR)b,c | 35 (28–50) | 30 (25–45) | 35 (30–50) | 0.02 |

| Glasgow Coma Scale, median (IQR)b | 12 (9–15) | 14 (9–15) | 11 (9–15) | 0.001 |

| ≥ 1 sedative/analgesic infusion, n (%) | 809 (46) | 251 (40) | 558 (49) | 0.001 |

| Delirium present, n (%) | 0.11 | |||

| No | 453 (26) | 172 (28) | 281 (25) | |

| Yes | 182 (10) | 72 (12) | 110 (10) | |

| Not available | 1,133 (64) | 380 (61) | 753 (66) | |

| Any vasoactive infusion, n (%)d | 371 (21) | 109 (17) | 262 (23) | 0.007 |

| Any physical restraint, n (%) | 249 (14) | 74 (12) | 175 (15) | 0.05 |

| Any central venous catheter, n (%) | 1,189 (67) | 430 (69) | 759 (66) | 0.29 |

| Arterial catheter, n (%) | 483 (27) | 146 (23) | 337 (30) | 0.006 |

| Hemodialysis catheter, n (%) | 84 (5) | 39 (6) | 45 (4) | 0.03 |

| Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation cannula, n (%) | 39 (2) | 13 (2) | 26 (2) | 0.79 |

| Indwelling urinary catheter, n (%) | 249 (14) | 73 (12) | 176 (15) | 0.03 |

| Surgical drain, n (%) | 135 (8) | 56 (9) | 79 (7) | 0.12 |

| Chest tube, n (%) | 194 (11) | 65 (10) | 129 (11) | 0.57 |

| Ventricular assist device, n (%) | 16 (1) | 7 (1) | 9 (1) | 0.48 |

| Intracranial pressure monitor, n (%) | 50 (3) | 26 (4) | 24 (2) | 0.01 |

| Presence of pressure ulcer(s) | 125 (7) | 41 (7) | 84 (7) | 0.54 |

| Nurse-to-patient ratio, n (%)b | 0.002 | |||

| 2:1 or 1:1 | 733 (42) | 228 (37) | 505 (45) | |

| 1:2 or 1:3 | 1,023 (58) | 392 (63) | 631 (56) | |

| Family present at bedside | 1,315 (74) | 497 (80) | 818 (72) | < 0.001 |

IQR = interquartile range, OT = occupational therapy, PT = physical therapy.

Calculated using χ2 test and Mann-Whitney U test, as appropriate.

Missing data: respiratory support (n = 6), Fio2 (n = 2), Glasgow Coma Scale (n = 3), nurse-to-patient ratio (n = 13).

Among patient-days with all types of respiratory support above nasal cannula or face mask (n = 1,291).

Excluding milrinone.

Timing of PT/OT Consultation

By PICU day 3, PT and/or OT had been consulted for 538 patients (32%), with 411 (24%) having received treatment. Across the two study days, 671 patients (38%), with a median PICU LOS of 7 (IQR 5–12) days, did not have an active PT or OT consultation. Children with higher baseline function (PCPC ≤2 vs. >2) were less likely to have had PT or OT consultation by day 3 than were those with lower baseline function (27% vs. 38%; P<0.001, Supplemental Digital Content 5).

Therapist-provided Mobility

The prevalence of PICU patients who received PT- and/or OT-provided mobility on the study day was 35% (95% CI, 33%−38%). Patients received only PT, only OT, or both on 13%, 10% and 13% of study days, respectively; 42% of study days with both PT- and OT-provided mobility (n=103) were co-treatment during the same session. Tables 1 and 2 display univariate analysis for demographic and clinical factors and the primary outcome of PT or OT-provided mobility, while Supplemental Digital Content 6–8 provide PT and OT-specific data. Therapist-provided mobility (Supplemental Digital Content 8) was associated with older age (aOR compared to age<3: 7–12 years, 1.91 [95% CI, 1.34–2.73] and 13–17 years, 2.1 [95% CI, 1.45–3.06]), moderate baseline disability (PCPC 3 vs. PCPC 1: 1.38; 95% CI, 1.04–2.06), and longer PICU LOS (2.49 per 10-fold higher PICU day before day 100; 95% CI, 1.87–3.4). Presence of intracranial pressure monitoring also was associated with therapist-provided mobility (aOR 2.25; 95% CI, 1.15–4.39). Therapist-provided mobility increased with family presence on the study day (aOR 1.43; 95% CI, 1.08–1.89) and with presence of a PICU mobility protocol (aOR 1.58; 95% CI, 0.99–2.51). In contrast, female sex (aOR 0.76; CI, 0.61–0.95) was inversely associated with therapist-provided mobility. In discipline-specific regression analysis (Supplemental Digital Content 8), PT-provided mobility was associated with surgical (vs. medical) admission and older age groups, while OT-provided mobility was negatively associated with moderate and severe disability (PCPC 4 or 5 vs. PCPC 1).

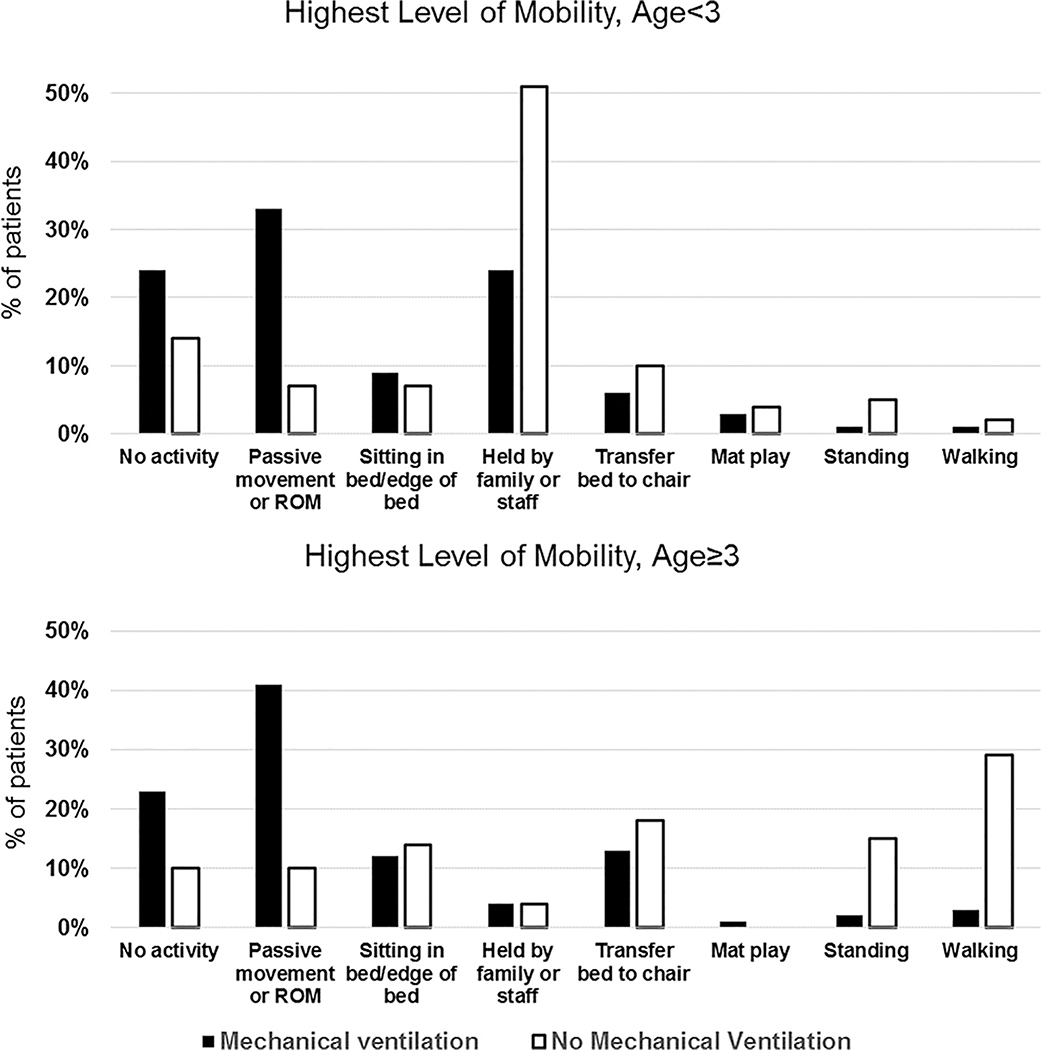

All Mobilization Events

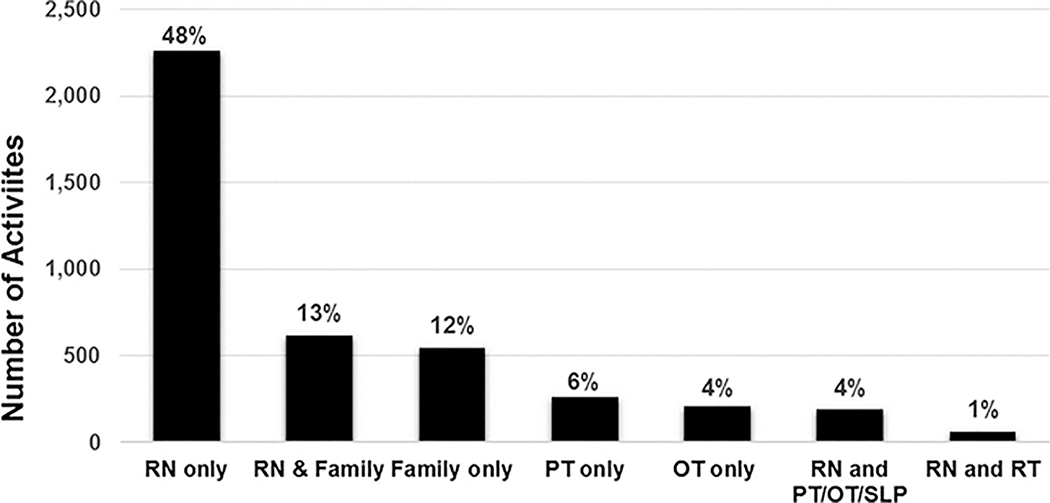

Of 1769 patient-days, 335 (19%) had no reported mobilization event. Most patients with no mobilization were mechanically ventilated (243 of 335 patient-days, 72%). On the 1434 patient-days with mobility, 4700 mobilization events occurred, for a median (IQR) of 2 (1–4) events per day. Figure 1 shows the highest level of mobility achieved on the study day. Among mechanically ventilated children, passive range of motion was the most common mobility event (age <3: 33%; age ≥3: 41%). Among those not mechanically ventilated, being held by family/nurse was most common for children <3 years (51%), and ambulation was most common for patients ≥3 years (29%). Nurses most commonly facilitated mobilization (n=3134, 67%), either alone or in combination with family or other PICU staff, whereas 12% of events were facilitated by family alone (n=546; Figure 2).

Figure 1. Highest Level of Mobility by Mechanical Ventilation Status, Stratified by Age.

Abbreviation: ROM, range of motion.

Figure 2. Number of Activities by Clinician Type.

Abbreviations: RN, registered nurse; PT, physical therapist; OT, occupational therapist; SLP, speech-language pathology; RT, respiratory therapist

Out-of-bed mobility

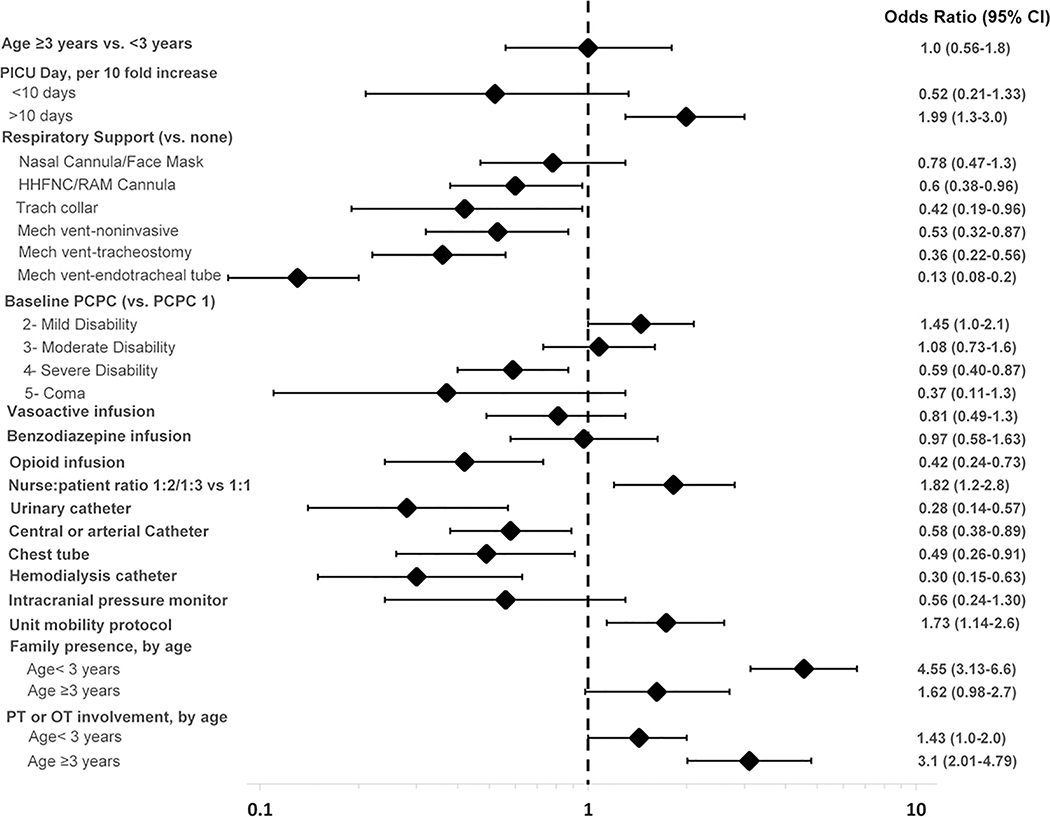

Out-of-bed mobility was achieved on 824 of 1769 study days, a prevalence of 47% (95% CI, 44%−49%), most commonly being held by a family member or nurse (n=403, 23%). Out-of-bed mobility was achieved on 70% of patient-days by those not mechanically ventilated (n=504), but only 30% of patient-days by mechanically ventilated children (n=320). Three of 136 patients (2%) who were ambulatory prior to PICU admission achieved ambulation with an endotracheal tube.

Variables that had the strongest negative association with out-of-bed mobility included presence of an endotracheal tube (aOR, 0.13; 95% CI, 0.08–0.2), urinary catheter (aOR, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.14–0.57) and other medical devices (Figure 3 and Supplemental Digital Content 9). Opioid infusion (0.42; 95% CI, 0.24–0.73) and severe baseline disability (PCPC 4 vs. 1: aOR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.4–0.87) were also negatively associated with out-of-bed mobility.

Figure 3: Adjusted Odds Ratios for Out-of-bed Mobility on Study Day.

The multivariable model included random effect for site, adjusted for admission reason, gender, and ethnicity in addition to all characteristics listed. Vasoactive infusion excluded milrinone. The interaction term for family presence by age strata was P = 0.005 in the univariate model and P = 0.001 in the multivariable model. The interaction term for physical therapy (PT) or occupational therapy (OT) involvement by age strata was P = 0.16 in the univariate model and P = 0.005 in the multivariable model. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HHFNC, heated high-flow nasal cannula; mech vent, mechanical ventilation; PCPC, Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category; PICU, pediatric intensive care unit.

Out-of-bed mobility was positively associated with longer PICU LOS (1.99 per 10-fold higher PICU day after day 10; 95% CI, 1.3–3.0) and lower nurse:patient ratio, a marker of lower patient acuity (1.82; 95% CI, 1.2–2.8). Among children <3 years, family presence had a strong positive association with out-of-bed mobility (aOR, 4.55, 95% CI, 3.1–6.6), whereas PT or OT involvement was strongly associated in children ≥3 (aOR, 3.1, 95% CI, 2.01–4.79).

Barriers to Mobility and Potential Safety Events

At least one barrier to mobilization was reported during 892 patient-days (51%) and 232 patient-days (72%) with no mobilization (Supplemental Digital Content 10). Most common barriers were medical contraindications (n=154, 9%), cardiovascular instability (n=154, 9%) and oversedation (n=148, 8%).

Staff reported a potential safety event in 195 (4%) of 4,700 mobility events, most commonly transient vital sign changes (n=136, 3%). Chest tubes and arterial lines were displaced in 3 of 194 (0.7%) and 2 of 982 (0.2%) mobility events, respectively. Three of these five events occurred with a nurse and family member, one with a family member alone, and another with a nurse alone. Dislodgment of endotracheal tube was reported in 2 of 1299 (0.15%) mobilization events during passive range of motion and proning with a nurse. One tracheostomy (0.1% of 888 events) was dislodged during an attempt to stand with an OT.

DISCUSSION

In this point prevalence study representing one-third of all PICU beds in the U.S.(13), the youngest children and patients with higher baseline function less often received PT- or OT-provided mobility. Despite evidence supporting the safety and feasibility of early mobility in critically ill children (22), early rehabilitation consultation was infrequent, and one-fifth of patients were completely immobile. Family presence was strongly associated with out-of-bed mobility for children <3 years. The rate of potential safety events was low across the large number of mobility events, especially when compared to the harms of bedrest in critically ill children. These findings provide important insights to inform systematic design of rehabilitation interventions in the PICU to optimize outcomes for critically ill children.

Our finding that 61% of all PICU patients with a stay ≥72 hours are <3 years old and less likely to receive therapist-provided mobility highlights an important issue given the rapid neurocognitive and physical development of these youngest patients. PTs and OTs provide key interventions to advance infants’ and toddlers’ gross and fine motor skills, sensory processing, and cognition during critical illness (31, 32). It is reassuring that family engagement increased mobility for children <3 years. However, it is ideal for families to partner with rehabilitation specialists and help facilitate prescribed interventions (i.e., passive range of motion, sensory stimulation). Interestingly, family presence was associated with increased therapist-provided mobility. Families of chronically critically ill children and those with previous PICU admission experiences may advocate more often for rehabilitation consultation (33, 34).

Similar to previous retrospective and quality improvement studies in the PICU (34, 35), early rehabilitation consultation and therapist-provided mobility was less frequent in patients with higher baseline function. Rehabilitation consultation may be delayed because of perception that these patients are at lower risk for functional impairment. However, PICU studies demonstrate that these children are, in fact, at high risk for functional deterioration and slow functional recovery (9). It is unclear why female sex was negatively associated with therapist-provided mobility. This finding requires further investigation given that girls have and similar rates of morbidity to boys (9, 15).

Presence of a unit mobility protocol was associated with both therapist-provided mobility and out-of-bed mobility in our study. Standardized, unit-based protocols can increase mobility and improve clinical outcomes for all patients regardless of age, diagnosis, or functional baseline, decreasing potential for implicit bias in clinician decision-making (36–40). However, we found that a minority of PICUs have dedicated PT or OT staff. While many PICU patients may benefit from early consultation and collaborative treatment by both PT and OT, it is critical for interdisciplinary teams to determine the best timing, frequency and approach to rehabilitation team involvement, given finite rehabilitation resources. Pediatric PTs focus on increasing physical function and rehabilitation of the musculoskeletal system (41, 42), while OTs have a central role in enabling infants and children to progress toward, or return to, key daily activities including play, feeding and eating (43). Therefore, educating PICU staff about these unique and complementary skillsets and indications for PT and OT consultation can optimize resource utilization and clinical care in the context of each hospital’s rehabilitation team staffing model.

Our results share several key similarities and differences with adult point prevalence data. The low prevalence of out-of-bed mobility in mechanically ventilated patients (30%) was similar to that in adult studies (0–33%) (18–21), but a higher proportion of PICU patients (16%) achieved out-of-bed mobility with an endotracheal tube (0–10% in adults) (18–21). This difference is likely because 67% of intubated PICU patients were <3 years and more likely to be held out-of-bed. Among intubated children ≥3 years, only 9% were mobilized out-of-bed. Our study also highlights the central role of PICU nurses in mobilization, nearly identical to the U.S. ARDSnet mobilization point prevalence study where nurses facilitated most mobility events (67% vs. 65%) (18). As a constant presence at the bedside, nurses are integral members of the interdisciplinary mobility team (44–47).

Invasive devices are barriers to early rehabilitation across all ICU populations (48, 49). Our findings of decreased out-of-bed mobility with most types of respiratory support and invasive medical devices is consistent with adult studies. A unique finding, however, was indwelling urinary catheters as a PICU risk factor for decreased out-of-bed mobility. Daily review for potential medical device removal can both reduce infection risk and avoid tethering patients to bed. If these devices are required, out-of-bed mobility can be safe, especially if there is multiprofessional education regarding device securement and pre-mobility planning (50).

As such, we found a low incidence (4%) of potential safety events associated with mobilization, similar to that in adult literature (2.6%) (51). Most PICU safety events (81%) were transient vital sign changes without clinical consequence. Only 0.3% of all mobility events were associated with dislodgement of a device, similar to the 0.6% rate in adults (51). Therefore, our data, in parallel with evidence from single-center PICU studies (22, 36, 38), suggest that mobilization of PICU patients is safe. However, education on methods for safe mobilization is critical for the interdisciplinary team.

Finally, we identified perceived barriers to mobility including medical status, lack of physician order, isolation precautions and oversedation. Opioid infusion, the first-line approach to analgosedation for PICU patients (52), was negatively associated with out-of-bed mobility, which may also be a reflection of acute pain that can impact mobility. Goal-directed and minimal sedation using multicomponent approaches facilitates participation in ICU rehabilitation for all patients and improves outcomes (37, 53–56). Similar PICU bundles have increased mobility and rehabilitation team involvement, and multicenter trials are underway to evaluate the impact on outcomes (22, 36, 38, 39, 57–59).

There are several strengths and limitations to our study. First, while we included a large proportion of U.S. PICUs which provides robust prevalence data, the point prevalence design cannot establish a causal relationship among the data. Second, knowledge of the study by clinical staff may have increased mobility events. However, this knowledge would not affect data on early rehabilitation consultation. Additionally, any bias would result in our overestimating mobility, which would further reinforce the message of low levels of rehabilitation and mobilization. Third, prospective data collection is limited by the quality of bedside documentation. Study teams worked closely with clinical staff during both day and night shifts to optimize data collection. Fourth, we included only weekdays, which may not reflect weekend rehabilitation characteristics. Fifth, both point prevalence days were during winter months, with potential limited generalizability to other times of year. Sixth, citing nurse:patient ratio as a measure of patient acuity has limitations; however, in some PICUs validated illness severity and nursing workload tools are used when deciding on nursing ratios.(60, 61) Seventh, our study focused solely on mobility-based interventions and did not capture non-mobility interventions that are important for PICU rehabilitation (i.e. activities of daily living, cognition, speech, swallow) that may primarily be performed by OT or speech language pathology. In addition, combining PT and OT-provided mobility as the primary outcome may not recognize their unique contributions. Finally, the study results may not be generalizable to all U.S. PICUs or internationally, particularly in smaller units and low-resource settings. Yet, it is important to note that all 82 ICUs participated in this study without any financial support, reflecting the high level of interest in understanding physical rehabilitation and mobility in critically ill children in the U.S.

CONCLUSIONS

In U.S. PICUs, younger children, females, and patients with higher baseline function less often receive physical rehabilitation, and the presence of invasive devices are associated with decreased out-of-bed mobility. Early consultation and treatment by rehabilitation clinicians is infrequent despite a low rate of potential safety events. As a growing number of children survive critical illness with long-lasting physical impairments, there is a need to systematically design and evaluate PICU rehabilitation interventions for a vulnerable patient population.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

PARK-PICU Investigators (Collaborators): Michael S.D. Agus, Kerry Coughlin-Wells (Boston Children’s Hospital MICU, Boston, MA); Christopher, J. Babbitt (Miller Children’s and Women’s Hospital Long Beach, Long beach, CA); Sangita Basnet, Allison Spenner (St John’s Children’s Hospital, Springfield, IL); Christine Bailey, Kristen N Lee (University of Louisville, Louisville, KY); Deanna Behrens, Ramona Donovan (Advocate Children’s Hospital, Park Ridge, IL); Kristina A. Betters, Marguerite O. Canter (Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt, PICU, Nashville, TN); Meredith F. Bone, Sara VandenBranden (Anne & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, IL); Gokul Kris Bysani (Medical City Children’s Hospital, Dallas, TX); Maddie Chrisman, Ericka L. Fink (UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA); Lee Anne Christie (Dell Children’s Medical Center, Austin, TX): Jean Christopher (Akron Children’s Hospital, Akron, OH); Christina Cifra, Weerapong Lilitwat (The University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa); David S. Cooper, Alicia Rice (Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center CICU, Cincinnati, OH); Allison S. Cowl (Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Hartford, CT); Jason W. Custer (University of Maryland Children’s Hospital, Baltimore, MD); Melissa Chung (Nationwide Children’s Hospital PICU, Columbus, OH); Danielle Van Damme, Kristen A. Smith (C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital, Ann Arbor, MI); Rebecca Dixon, Erin Bennett (University of Utah Primary Children’s Hospital, Salt Lake City, UT); Molly V. Dorfman, Ashley Mancini (Valley Children’s Hospital, Madera, CA); Sharon P. Dial (Cohen Children’s Medical Center, New Hyde Park, NY); Jane L. Di Gennaro, Leslie A. Dervan (Seattle Children’s Hospital, Seattle, WA); Lesley Doughty, Laura Benken (Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center CICU, Cincinnati, OH); Mark C. Dugan, Judith Ben Ari (Children’s Hospital of Nevada at UMC, Las Vegas, NV); Melanie Cooper Flaigle, Vianne Smith (Providence Sacred Heart Children’s Hospital, Spokane, WA); Shira J. Gertz (St Barnabas medical Center, Livingston, NJ); Katherine Gregersen, Shamel A. Abd-Allah (Loma Linda University Health, Loma Linda CA); Justin Hamrick, Katherine Irby (University of Arkansas PICU & CVICU, Little Rock, AR); Jodi Herbsman, Yasir M. Al-Qaqaa (NYU Langone Medical Center, New York, NY); John Holcroft (University of California Davis, Davis, CA);Erin Hulfish, Kathleen Culver (Stony Brook Children’s Hospital, Stony Brook, NY); Susan Hupp, Andrea DeMonbrun (UTSW Children’s Medical Center PICU, Dallas, TX); Kelechi Iheagwara, Shelli Lavigne-Sims (Our Lady of the Lake Children’s Hospital, Baton Rouge, LA); Christine Joyce, Chani Traube (Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY); Pradip Kamat, Cheryl Stone (Egleston Children’s Hospital at Emory University PICU, Atlanta GA); Sameer S. Kamath, Melissa Harward (Duke Children’s Hospital & Health Center PICU, Durham, NC); Priscilla Kaszubski, Joanna Daguanno (St Joseph’s Children’s Hospital, Tampa, FL); Robert P. Kavanagh, Debbie Spear (Penn State Hershey Children’s Hospital, Hershey, PA); Yu Kawai, Karen Fryer (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN); Bree Kramer (Women and Children’s Hospital of Buffalo, Buffalo, NY); Erin M. Kreml, Brian T. Burrows (Phoenix Children’s Hospital PICU, Phoenix, AZ); Andrew W. Kiragu (Hennepin County Medical Center, Minneapolis, MN); John Lane (Phoenix Children’s Hospital CVICU, Phoenix, AZ); Truc M. Le, Stacey R. Williams (Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt, PCICU, Nashville, TN); John C. Lin, Amanda Florin (St. Louis Children’s Hospital, Saint Louis, MO); Peter M. Luckett, Tammy Robertson (UTSW Children’s Medical Center CVICU, Dallas, TX); Venessa N. Madrigal, Ashleigh B. Harlow (Children’s National Health System, Washington, DC); Barry Markovitz, Fernando Beltramo (Children’s Hospital Los Angeles CICU, Los Angeles, CA); Michael C. McCrory (Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center, Winston Salem, NC); Robin L. McKinney (Hasbro Children’s Hospital, Providence, RI); Maryam Y. Naim (Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia CICU, Philadelphia, PA); Asha G. Nair, Ravi Thiagarajan (Boston Children’s Hospital CICU, Boston, MA); Shilpa Narayan, Kathleen Murkowski (Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin/Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI); Keshava Murthy Narayana Gowda, Jhoclay See (Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH); Pooja A. Nawathe (Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA); William E. Novotny, Cynthia Keel (Vidant Medical Center, Greenville, NC); Peter Oishi, Neelima Marupudi (UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital, San Francisco, CA); Laura Ortmann (Children’s Hospital & Medical Center, Omaha, NE); AM Iqbal O’Meara, Nikki M. Ferguson (Children’s Hospital of Richmond at VCU, Richmond, VA); Megan E. Peters (University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI); Neethi Pinto, Allison Kniola (The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL); Courtney M. Rowan, Jill Mazyrcyk (Riley Hospital for Children at Indiana University, Indianapolis, IN); Shilpa Shah, Sage Lachman (Children’s Hospital Los Angeles CTICU, Los Angeles, CA); Marcy N. Singleton, Sholeen T. Nett (Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, NH); Michael C. Spaeder, Jenna V. Zschaebitz (University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA); Thomas Spentzas (Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital PICU, Memphis, TN); Sue S. Sreedhar (Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital, St. Petersburg, FL); Katherine M. Steffen, Michelle Chen (Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford, Palo Alto, CA); Anne Stormorken, Allison Blatz (Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital, Cleveland, OH); Sachin D. Tadphale (Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital CVICU, Memphis, TN); Robert C. Tasker, John F. Griffin (Boston Children’s Hospital MSICU, Boston, MA); Tammy L. Uhl, Melissa Harward (Duke Children’s Hospital & Health Center CICU, Durham, NC); Karen H. Walson, Cynthia Bates (Scottish Rite Children’s Hospital at Emory University, Atlanta GA); Christopher M. Watson, Mary Lynn Sheram (Children’s Hospital of Georgia at Augusta University, Augusta, GA); Cydni N. William, Aileen Kirby (OHSU Doernbecher Children’s Hospital, Portland, OR); Michael Wolf, Kellet Lowry (Egleston Children’s Hospital at Emory University CICU, Atlanta GA); Heather A. Wolfe (Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia MICU, Philadelphia, PA); Andrew R. Yates, Brian Beckman (Nationwide Children’s Hospital CTICU, Columbus, OH).

We appreciate the collaboration and generous investment of time from all 82 PICU teams that participated in this study without financial support. We would also like to thank Claire Levine, MS for her editorial assistance with this manuscript. This study was funded by a StAAR (Stimulating and Advancing ACCM Research) grant from the Johns Hopkins Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine.

Funding: This study was funded by the Johns Hopkins University Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine Stimulating and Advancing ACCM Research (StAAR) Award.

Footnotes

Copyright form disclosure: The authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

Data Access, Responsibility and Analysis: Dr. Kudchadkar had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- 1.Devlin JW, Skrobik Y, Gelinas C, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pain, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disruption in Adult Patients in the ICU. Crit Care Med 2018;46(9):e825–e873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cummins KA, Watters R, Leming-Lee T. Reducing Pressure Injuries in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. Nurs Clin North Am 2019;54(1):127–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curley MA, Quigley SM, Lin M. Pressure ulcers in pediatric intensive care: incidence and associated factors. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2003;4(3):284–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Field-Ridley A, Dharmar M, Steinhorn D, et al. ICU-Acquired Weakness Is Associated With Differences in Clinical Outcomes in Critically Ill Children. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2016;17(1):53–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Witmer CM, Takemoto CM. Pediatric Hospital Acquired Venous Thromboembolism. Front Pediatr 2017;5:198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit Care Med 2012;40(2):502–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown SM, Bose S, Banner-Goodspeed V, et al. Approaches to Addressing Post-Intensive Care Syndrome among Intensive Care Unit Survivors. A Narrative Review. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2019;16(8):947–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herrup EA, Wieczorek B, Kudchadkar SR. Characteristics of postintensive care syndrome in survivors of pediatric critical illness: A systematic review. World J Crit Care Med 2017;6(2):124–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choong K, Fraser D, Al-Harbi S, et al. Functional Recovery in Critically Ill Children, the “WeeCover” Multicenter Study. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2018;19(2):145–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silver G, Traube C, Kearney J, et al. Detecting pediatric delirium: development of a rapid observational assessment tool. 2012;38(6):1025–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manning JC, Pinto NP, Rennick JE, et al. Conceptualizing Post Intensive Care Syndrome in Children-The PICS-p Framework. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2018;19(4):298–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heneghan JA, Reeder RW, Dean JM, et al. Characteristics and Outcomes of Critical Illness in Children With Feeding and Respiratory Technology Dependence. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2019;20(5):417–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horak RV, Griffin JF, Brown AM, et al. Growth and Changing Characteristics of Pediatric Intensive Care 2001–2016. Crit Care Med 2019;47(8):1135–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pollack MM, Holubkov R, Reeder R, et al. PICU Length of Stay: Factors Associated With Bed Utilization and Development of a Benchmarking Model . Pediatr Crit Care Med 2018;19(3):196–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pinto NP, Rhinesmith EW, Kim TY, et al. Long-Term Function After Pediatric Critical Illness: Results From the Survivor Outcomes Study. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2017;18(3):e122–e130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pollack MM, Holubkov R, Funai T, et al. Pediatric intensive care outcomes: development of new morbidities during pediatric critical care. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2014;15(9):821–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tipping CJ, Harrold M, Holland A, et al. The effects of active mobilisation and rehabilitation in ICU on mortality and function: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med 2017;43(2):171–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jolley SE, Moss M, Needham DM, et al. Point Prevalence Study of Mobilization Practices for Acute Respiratory Failure Patients in the United States. Crit Care Med 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sibilla A, Nydahl P, Greco N, et al. Mobilization of Mechanically Ventilated Patients in Switzerland. J Intensive Care Med 2020;35(1):55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nydahl P, Ruhl AP, Bartoszek G, et al. Early mobilization of mechanically ventilated patients: a 1-day point-prevalence study in Germany. Crit Care Med 2014;42(5):1178–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berney SC, Harrold M, Webb SA, et al. Intensive care unit mobility practices in Australia and New Zealand: a point prevalence study. Crit Care Resusc 2013;15(4):260–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cuello-Garcia CA, Mai SHC, Simpson R, et al. Early Mobilization in Critically Ill Children: A Systematic Review. J Pediatr 2018;203:25–33 e26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prevalence of Acute Rehabilitation for Kids in the PICU (PARK-PICU). [Webpage] 2018. [cited 2019 January 1st] Available from: https://park.web.jhu.edu

- 24.Parry SM, El-Ansary D, Cartwright MS, et al. Ultrasonography in the intensive care setting can be used to detect changes in the quality and quantity of muscle and is related to muscle strength and function. J Crit Care 2015;30(5):1151 e1159–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schweickert WD, Pohlman MC, Pohlman AS, et al. Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2009;373(9678):1874–1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel BK, Pohlman AS, Hall JB, et al. Impact of early mobilization on glycemic control and ICU-acquired weakness in critically ill patients who are mechanically ventilated. Chest 2014;146(3):583–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 2019;95:103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42(2):377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kudchadkar SR. PARK-PICU Data Collection Forms. 2017. [cited 2019 April 1st]Available from: https://park.web.jhu.edu/data-collection-forms/

- 30.Lederer DJ, Bell SC, Branson RD, et al. Control of Confounding and Reporting of Results in Causal Inference Studies. Guidance for Authors from Editors of Respiratory, Sleep, and Critical Care Journals. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2019;16(1):22–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ross K, Heiny E, Conner S, et al. Occupational therapy, physical therapy and speech-language pathology in the neonatal intensive care unit: Patterns of therapy usage in a level IV NICU. Res Dev Disabil 2017;64:108–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Case-Smith J, Rogers S. Physical and occupational therapy. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 1999;8(2):323–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marcus KL, Henderson CM, Boss RD. Chronic Critical Illness in Infants and Children: A Speculative Synthesis on Adapting ICU Care to Meet the Needs of Long-Stay Patients. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2016;17(8):743–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cui LR, LaPorte M, Civitello M, et al. Physical and occupational therapy utilization in a pediatric intensive care unit. J Crit Care 2017;40:15–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choong K, Foster G, Fraser DD, et al. Acute rehabilitation practices in critically ill children: a multicenter study. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2014;15(6):e270–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wieczorek B, Ascenzi J, Kim Y, et al. PICU Up!: Impact of a Quality Improvement Intervention to Promote Early Mobilization in Critically Ill Children. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2016;17(12):e559–e566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pun BT, Balas MC, Barnes-Daly MA, et al. Caring for Critically Ill Patients with the ABCDEF Bundle: Results of the ICU Liberation Collaborative in Over 15,000 Adults. Crit Care Med 2019;47(1):3–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fink EL, Beers SR, Houtrow AJ, et al. Early Protocolized Versus Usual Care Rehabilitation for Pediatric Neurocritical Care Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2019;20(6):540–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsuboi N, Hiratsuka M, Kaneko S, et al. Benefits of Early Mobilization After Pediatric Liver Transplantation. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2019;20(2):e91–e97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miura S, Wieczorek B, Lenker H, et al. Normal Baseline Function Is Associated With Delayed Rehabilitation in Critically Ill Children. J Intensive Care Med 2018:885066618754507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.APTA. Who are Physical Therapists? 2019. [cited 2020 January 1st] Available from: https://www.apta.org/AboutPTs/

- 42.Association APT. Section on Pediatrics Fact Sheet: Frequency and Duration of Physical Therapy Services in the Acute Care Pediatric Setting. 2003. [cited 2020 January 1st] Available from: https://pediatricapta.org/includes/fact-sheets/pdfs/PEDS_Factsheet_FrequencyAndDuration.pdf

- 43.AOTA. What is Occupational Therapy? [cited 2019 November 1st.] Available from: https://www.aota.org/Conference-Events/OTMonth/what-is-OT.aspx

- 44.Davidson JE, Winkelman C, Gelinas C, et al. Pain, agitation, and delirium guidelines: nurses’ involvement in development and implementation. Crit Care Nurse 2015;35(3):17–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dammeyer JA, Baldwin N, Packard D, et al. Mobilizing outcomes: implementation of a nurse-led multidisciplinary mobility program. Critical care nursing quarterly 2013;36(1):109–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stolldorf DP, Dietrich MS, Chidume T, et al. Nurse-Initiated Mobilization Practices in 2 Community Intensive Care Units: A Pilot Study. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 2018;37(6):318–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Klein KE, Bena JF, Mulkey M, et al. Sustainability of a nurse-driven early progressive mobility protocol and patient clinical and psychological health outcomes in a neurological intensive care unit. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2018;45:11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dubb R, Nydahl P, Hermes C, et al. Barriers and Strategies for Early Mobilization of Patients in Intensive Care Units. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2016;13(5):724–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Damluji A, Zanni JM, Mantheiy E, et al. Safety and feasibility of femoral catheters during physical rehabilitation in the intensive care unit. J Crit Care 2013;28(4):535 e539–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chohan S, Ash S, Senior L. A team approach to the introduction of safe early mobilisation in an adult critical care unit. BMJ Open Qual 2018;7(4):e000339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nydahl P, Sricharoenchai T, Chandra S, et al. Safety of Patient Mobilization and Rehabilitation in the Intensive Care Unit. Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2017;14(5):766–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kudchadkar SR, Yaster M, Punjabi NM. Sedation, sleep promotion and delirium screening practices in the care of mechanically ventilated children: A wake-up call for the pediatric critical care community. Crit Care Med 2014;42(7):1592–1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kamdar BB, Combs MP, Colantuoni E, et al. The association of sleep quality, delirium, and sedation status with daily participation in physical therapy in the ICU. Crit Care 2016;19:261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morris PE, Berry MJ, Files DC, et al. Standardized Rehabilitation and Hospital Length of Stay Among Patients With Acute Respiratory Failure: A Randomized Clinical TrialICU Rehabilitation and Length of Stay for Acute Respiratory Failure PatientsICU Rehabilitation and Length of Stay for Acute Respiratory Failure Patients. JAMA 2016;315(24):2694–2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ely EW. The ABCDEF Bundle: Science and Philosophy of How ICU Liberation Serves Patients and Families. Crit Care Med 2017;45(2):321–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Needham DM, Korupolu R, Zanni JM, et al. Early physical medicine and rehabilitation for patients with acute respiratory failure: a quality improvement project. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation 2010;91(4):536–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.National Institutes of Health. PICU Up!: A Pilot Trial of a Multicomponent Early Mobility Intervention for Critically Ill Children. 2019. [cited 2019 November 1st] Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03860168

- 58.Betters KA, Hebbar KB, Farthing D, et al. Development and implementation of an early mobility program for mechanically ventilated pediatric patients. J Crit Care 2017;41:303–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Van Damme D, Flori H, Owens T. Development of Medical Criteria for Mobilizing a Pediatric Patient in the PICU. Critical care nursing quarterly 2018;41(3):323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rogowski JA, Staiger DO, Patrick TE, et al. Nurse Staffing in Neonatal Intensive Care Units in the United States. Res Nurs Health 2015;38(5):333–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Law AC, Stevens JP, Hohmann S, et al. Patient Outcomes After the Introduction of Statewide ICU Nurse Staffing Regulations. Crit Care Med 2018;46(10):1563–1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.