Abstract

We report the synthesis and photochemical and biological characterization of Ru(II) complexes containing π-expansive ligands derived from dimethylbenzo[i]dipyrido[3,2-a:2′,3′-c]phenazine (Me2dppn) adorned with flanking aryl substituents. Late-stage Suzuki couplings produced Me2dppn ligands substituted at the 10 and 15 positions with phenyl (5), 2,4-dimethylphenyl (6), and 2,4-dimethoxyphenyl (7) groups. Complexes of the general formula [Ru(tpy)(L)(py)](PF6)2 (8–10), where L = 4–7, were characterized and shown to have dual photochemotherapeutic (PCT) and photodynamic therapy (PDT) behavior. Quantum yields for photodissociation of monodentate pyridines from 8–10 were about 3 times higher than that of parent complex [Ru(tpy)(Me2dppn)(py)](PF6)2 (1), whereas quantum yields for singlet oxygen (1O2) production were ~10% lower than that of 1. Transient absorption spectroscopy indicates that 8–10 possess long excited state lifetimes (τ = 46–50 μs), consistent with efficient 1O2 production through population and subsequent decay of ligand-centered 3ππ* excited states. Complexes 8–10 displayed greater lipophilicity relative to 1 and association to DNA but do not intercalate between the duplex base pairs. Complexes 1 and 8–10 showed photoactivated toxicity in breast and prostate cancer cell lines with phototherapeutic indexes, PIs, as high as >56, where the majority of cell death was achieved 4 h after treatment with Ru(II) complexes and light. Flow cytometric data and rescue experiments were consistent with necrotic cell death mediated by the production of reactive oxygen species, especially 1O2. Collectively, this study confirms that DNA intercalation by Ru(II) complexes with π-expansive ligands is not required to achieve photoactivated cell death.

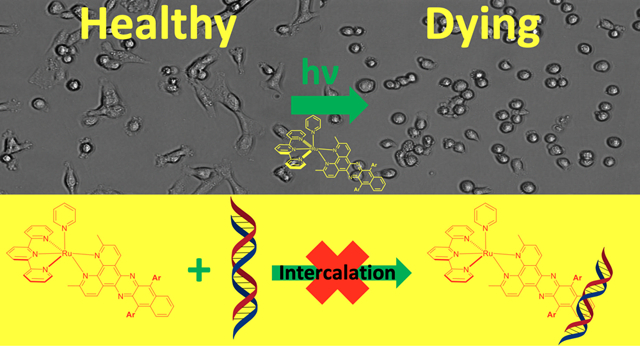

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Ruthenium complexes have broad applications in solar energy capture, photocaging, photodynamic therapy (PDT), and photochemotherapy (PCT).1–4 For biological applications including PDT and PCT, Ru(II) complexes show many attractive properties, including cell permeability,5,6 low inherent toxicity,7–10 efficient photodissociation of ligands,11–19 and high dark-to-light ratios for cancer cell death.20–24 Long-standing efforts in the development of Ru(II)-based photosensitizers have led to recent success in the achievement of a major milestone. The compound TLD-1433, which is the first Ru(II)-based photosensitizer to enter the clinic, advanced to Phase II clinical trials for the treatment of nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer due to promising results in preclinical development and earlier trials.25

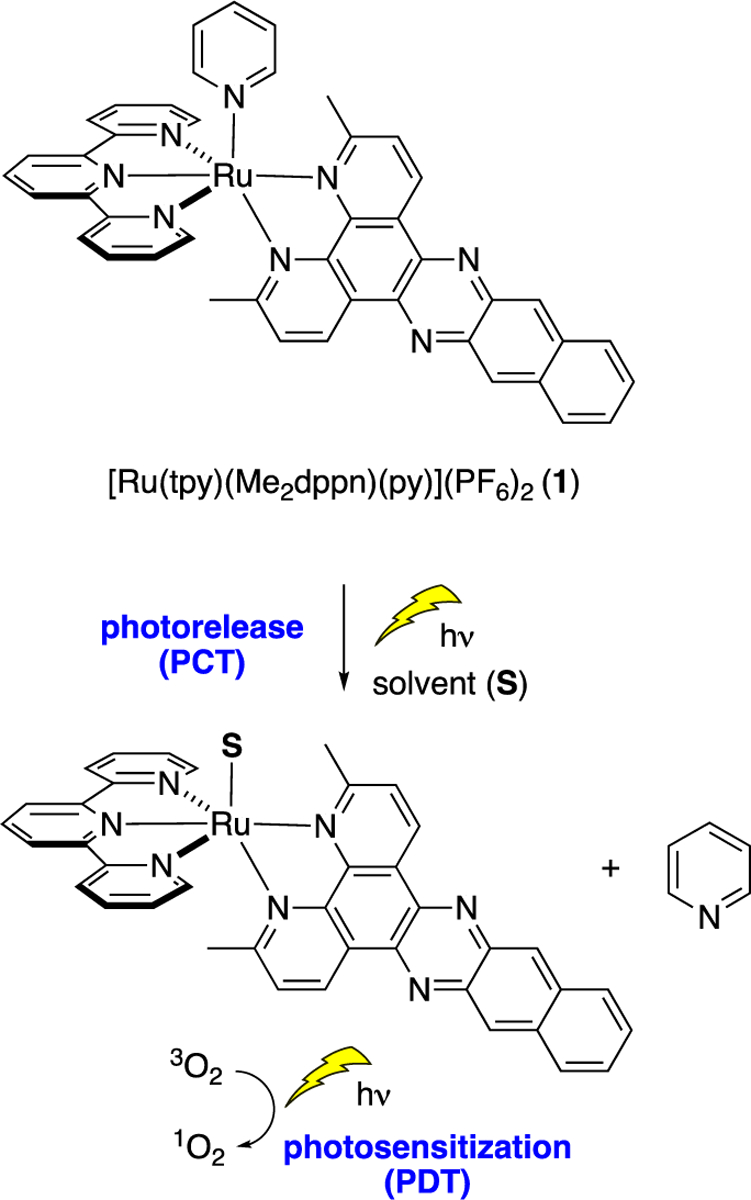

An important feature of Ru(II) complexes is that they absorb visible light strongly into singlet metal-to-ligand charge transfer (1MLCT) states that undergo intersystem crossing with nearly 100% yield to populate corresponding triplet MLCT (3MLCT) states.26 Coordination of a ligand with an extended π-system that possesses a ligand-centered 3ππ* state that falls below the 3MLCT state results in long excited state lifetimes (20–50 μs) that efficiently produce singlet oxygen (1O2),27 the mechanism of action for most Type II photosensitizers used in clinical PDT.28 In addition, complexes with sterically encumbered ligands that distort the coordination around the Ru(II) center from the ideal octahedral geometry result in lower energy metal-centered state(s) of antibonding character that can be populated from 3MLCT states, which facilitates ligand dissociation, the concept exploited in PCT.15,29 The Turro laboratory was the first to report Ru(II)-based complexes that show dual activity accessible with low energy light, resulting in both the photosensitized production of 1O2 and the photodissociation of aromatic heterocycles as models for drug molecules (Figure 1).15,27 The π-expansive ligand 3,6-dimethylbenzo[i]dipyrido-[3,2-a:2′,3′-c]phenazine (Me2dppn) contains a phenanthroline core fused with a diaminonaphthalene unit and was an essential component of this dual-action PDT/PCT agent. Importantly, the combination of PCT and PDT realized with a Me2dppn-containing Ru(II) complex was shown to be critical for achieving efficient, light-activated cell death in in vitro models of triple-negative breast cancer.30 Related complexes that underwent either PCT or PDT alone showed minimal, if any, cytotoxicity in these 2D and 3D culture models, proving that dual-action PCT/PDT creates and promotes efficacy of Ru(II) compounds against cancer cells.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the molecular structure of dual-action Ru(II) complex 1 containing the ligand Me2dppn and its photoactivated ligand dissociation for PCT and 1O2 photosensitization for PDT.

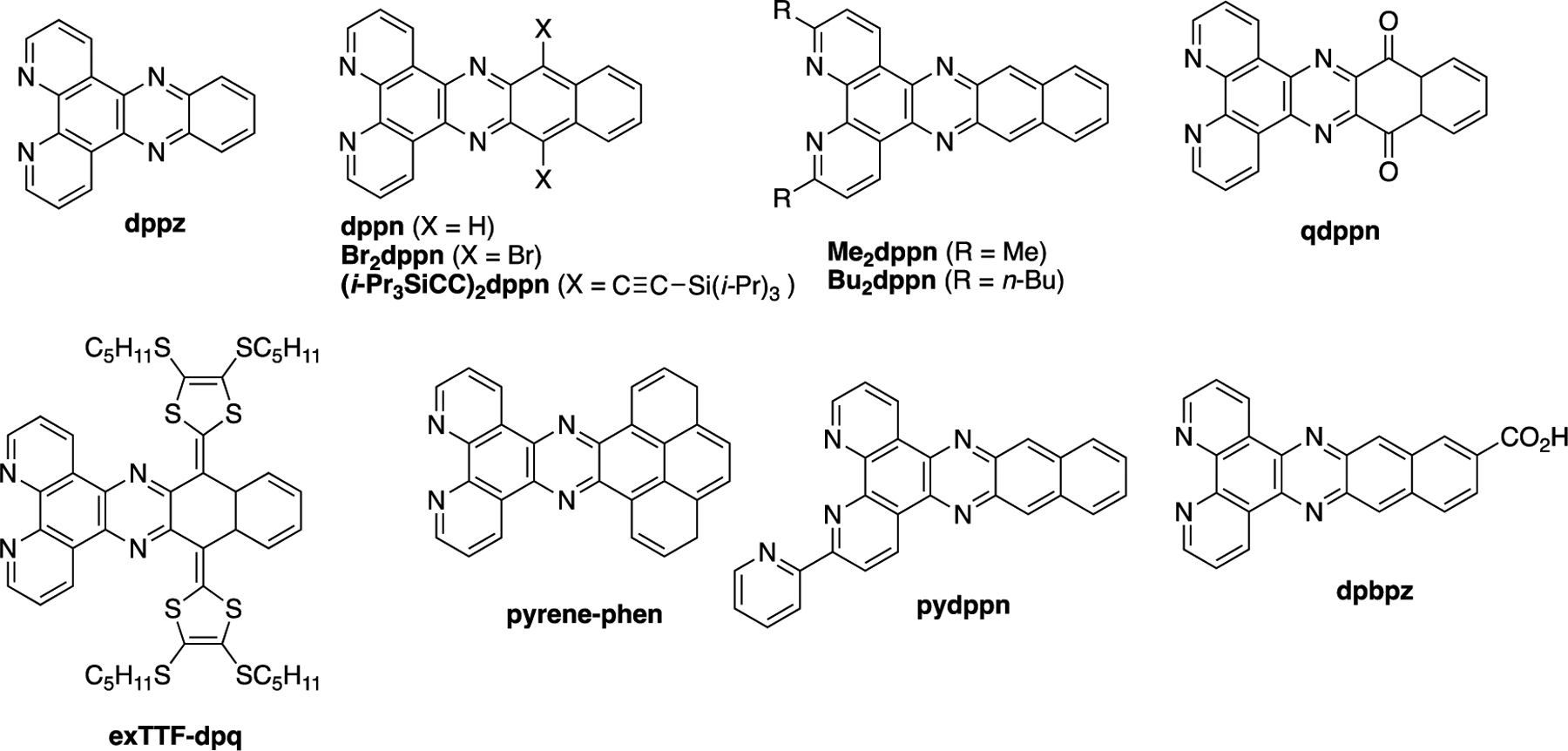

Aside from dual-action PCT/PDT agents, derivatives of the ligand dppn (Figure 2) have been incorporated into Ru(II) and related metal complexes for research in photochemistry, solar energy capture,31 sensing,32 and biology, including anticancer20,33–35 and antibacterial36,37 applications, among other works not cited here. Derivatives of dppn are underexplored, as opposed to other π-expansive ligands such as dipyrido[3,2-a:2′,3′-c]phenazine (dppz, Figure 2); a Sci-Finder search shows >100 analogs of dppz have been reported. Derivatives of dppn include structures shown in Figure 2. Analogs with substituents at the 3- (pydppn),38–41 3- and 6-(Me2dppn, Bu2dppn)42 and 10- and 15-positions (Br2dppn43 and (i-Pr3SiCC)2dppn44) have been synthesized. In addition, the p-quinone analog qdppn has been incorporated into several Ru(II) complexes with short-lived excited states that show low yields for 1O2 generation.20,45 The tetrathiafulvalene ligand exTTF-dpq was built into the complex [Ru(bpy)2(exTTF-dpq)]2+, which shows absorbance at >650 nm that is red-shifted by ~100 nm compared with [Ru(bpy)2(qdppn)]2+.46 Other derivatives include the pyrene-containing ligand pyrenephen47 and the carboxylic acid analog dppbz.48

Figure 2.

Bidentate π-expansive ligands include dppz and dppn derivatives

A major theme for Ru(II) complexes derived from dppn is their ability to bind, intercalate, and photocleave DNA. In some cases, the extended π-system of dppn may provide stronger binding and intercalation of Ru(II) complexes with DNA than complexes derived from dppz.49,50 Photocleavage of purified DNA by dppn-containing Ru(II) complexes has been demonstrated owing to its efficient production of 1O2 from a dppn-centered 3ππ* state, combined with its strong DNA binding.51,52 The complexes [Ru(tpy)(pydppn)]2+ and [Ru-(pydppn)2]2+ generated photodynamic DNA–protein and protein cross-links in human fibroblasts, including p53 and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) cross-links, consistent with nuclear targeting and DNA oxidation.39 In this case, data indicated that oxidative cross-linking was due to generation of 1O2 because cross-linking could be blocked by pretreatment of the cells with sodium azide, an efficient 1O2 scavenger. Although most studies implicate DNA targeting, other work suggests that dppn-containing Ru(II) complexes may interact with the cell membrane and lipid bilayers in cells.53,54 In general, it is often assumed that complexes of this class target and intercalate DNA in cells, but research that probes the mechanism of cell death using cell-based assays has been limited.39,54

In this manuscript, we describe the synthesis, characterization, and the photochemical and biological properties of Ru(II) complexes containing arylated derivatives of the ligand Me2dppn that were designed to increase lipophilicity and to block DNA intercalation. We report a late-stage divergent approach for the synthesis of Me2dppn analogs that provides rapid access to new Me2dppn ligands with aryl substituents attached to the 10- and 15-positions. Despite the fact that these new Ru(II) complexes are not expected to intercalate between the DNA bases, herein we show that they interact with DNA and exhibit dual-action PCT/PDT activity, with photoactivated toxicity in breast and prostate cancer cells that is achieved on short time scales. Investigations into the mode of cell death by Ru(II) complexes containing Me2dppn and its analogs indicate that high phototherapeutic indexes (PIs) can be achieved and that rapid cellular necrosis, rather than apoptosis, is the dominant mechanism of death at early time points. This work shows that cell death can be rescued using scavengers of reactive oxygen species (ROS), consistent with ROS generation, especially 1O2, being responsible for the cytotoxicity of these compounds and is important for future design of dual-action PDT/PCT complexes.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

General Considerations.

NMR and IR spectral data and mass spectrometry data were collected as previously described.30 Reactions were performed under ambient atmosphere unless otherwise noted.

Instrumentation.

Steady-state electronic absorbance spectra were collected using an Agilent Cary 8454 diode array spectrophotometer or Agilent Technologies Cary-Win UV–vis spectrometer. Emission data were collected using a Horiba FluoroMax-4 fluorimeter. The irradiation source for quantum yield measurements was a 150 W Xe arc lamp (USHIO) in a MilliArc lamp housing unit, powered by an LPS-220 power supply and an LPS-221 igniter (PTI). Irradiation wavelengths for steady-state photolysis were controlled with long-pass filters (CVI Melles Griot), and quantum yield experiments were conducted using a 500 nm bandpass filter (Thorlabs). Relative viscosity measurements were performed using a Cannon–Manning semimicro viscometer for transparent liquids submerged in a water bath maintained at 25 °C by a Neslab model RGE-100 circulator. Nanosecond transient absorption was performed using a LP980, an Edinburgh Instruments spectrometer equipped with a 150 W Xe arc lamp (USHIO) as the probe beam, an intensified CCD (ICCD) detector, and a PMT. The samples were excited by the output of an optical parametric oscillator (basiScan, Spectra-Physics) pumped by a Nd:YAG laser (Quana-Ray INDI, Spectra-Physics) as an excitation source with fwhm = 8 ns. The spectra were collected at various time details with an ICCD camera, and kinetic traces were recorded using a PMT and digital oscilloscope.

Methods.

The quantum yields for photoinduced ligand exchange in 8–10 were measured at λirr = 500 nm in MeCN using potassium ferrioxalate as an actinometer following a previously published procedure.55 Singlet oxygen quantum yields were performed using [Ru(bpy)3]2+ as a standard (ΦΔ = 0.81 in MeOH), 1,3-diphenylisobenzofuran (DPBF) as a 1O2 trapping agent, and following a previously established procedure.56 Steady-state and time-resolved electronic absorption was performed using 1 × 1 cm quartz cuvettes, and the concentration of samples for transient absorption spectroscopy was adjusted to obtain an absorbance value of 0.5 at the excitation wavelength.

Relative viscosity and electronic absorption titrations were performed using calf thymus DNA purified overnight by dialysis against 5 mM Tris, 50 mM NaCl, and pH 7.0 buffer. Changes to the electronic absorption spectra of 5 μM of 8 and 9 and 10 μM of 10 upon addition of increasing amounts of DNA (0–350 μM) in a manner not to affect the absorption by sample dilution were attempted to determine binding constants, Kb (5 mM Tris, 50 mM NaCl, pH 7.0), as is typical for complexes with extended π-systems.57 However, self-aggregation of the complexes, enhanced aggregation in the presence of polyanionic DNA or polystyrenesulfonate (PSS), and interactions with hydrophobic DNA regions result in similar spectral changes, such that the accurate determination of Kb was not possible using this method.58 Relative viscosity measurements were performed using sonicated calf thymus DNA that was an average length of ~200 base pairs in order to minimize DNA flexibility.59 For these experiments, the ratio of the amount of metal complex or ethidium bromide to that DNA was increased by adding small volumes of concentrated stock solutions to the DNA sample already in the viscometer. Solutions in the viscometer were mixed by bubbling with nitrogen and equilibrated to 25 °C by allowing samples to equilibrate in the water bath for 30 min prior to each measurement. Relative viscosities for DNA in the presence or absence of complex were calculated from eq 1

| (1) |

where t is the flow time of a given solution containing DNA and t0 is the flow time of buffer alone. Relative viscosity data are plotted as (η/η0)1/3 as a function of the ratio of complex to DNA concentration, where η is the relative viscosity of a solution at a given [complex]: [DNA] ratio, and η0 is the relative viscosity of a solution containing only DNA.

10,15-Dibromo-3,6-dimethylbenzo[i]dipyrido[3,2-a:2′,3′-c]phenazine (Me2Br2dppn, 4).

2,9-Dimethyl-1,10-phenanthroline-5,6-dione60 (0.55 g, 2.3 mmol) and 1,4-dibromo-2,3-diaminonaphthalene61 (0.73 g, 2.3 mmol) were refluxed in EtOH (46 mL) at 80 °C for 16 h under nitrogen atmosphere, during which time a red precipitate formed. The reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature, and the precipitate was collected by filtration, washed with EtOH, and dried in vacuo to give 3 as a red solid (0.80 g, 1.5 mmol, 67%): 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.61 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 8.74 (dd, J = 6.9, 3.2 Hz, 2H), 7.75 (dd, J = 6.9, 3.3 Hz, 2H), 7.70 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 3.04 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 162.80, 136.49, 135.83, 134.82, 133.30, 128.74, 128.39, 125.53, 124.90, 124.24, 25.63; IR (KBr) 3059, 2978, 2954, 2916, 2360, 2342, 1672, 1618, 1582, 1463, 1420, 1378, 1260, 1130, 938, 832, 749; ESMS calcd for C24H15Br2N4 [M + H]+ 517.0, found 516.9.

General Procedure for Suzuki Cross Coupling Reactions.

Me2Br2dppn (4), aryl boronic acid, PdCl2, PPh3, and K2CO3 were combined in a sealable pressure tube. Water (4 mL), ethanol (6 mL), and toluene (8 mL) were added, and the mixture was deoxygenated by bubbling Ar through a submerged needle for 20 min. The pressure tube was sealed, and the mixture was heated to reflux for 24 h. After aqueous workup, the crude product was purified via recrystallization or by chromatography on neutral alumina.

3,6-Dimethyl-10,15-diphenylbenzo[i]dipyrido[3,2-a:2′,3′-c]phenazine (Me2Ph2dppn, 5).

Compound 5 was prepared using the general procedure for Suzuki cross coupling reactions from 4 (207 mg, 0.400 mmol), phenylboronic acid (148 mg, 1.21 mmol), PdCl2 (7 mg, 0.04 mmol), PPh3 (21 mg, 0.080 mmol), and K2CO3 (221 mg, 1.60 mmol). The reaction mixture was cooled to rt, diluted with ethyl acetate (10 mL), and washed with a saturated solution of aqueous NaHCO3 (3 × 10 mL). The organic layer was separated, dried with anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated. The crude product was recrystallized from hot EtOH to give 5 (117 mg, 0.228 mmol, 57%) as an orange solid: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.98 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.2 Hz, 2H), 8.18–8.13 (m, 2H), 7.73–7.62 (m, 10H), 7.52 (dt, J = 8.2, 1.3 Hz, 4H), 2.95 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 161.5, 136.6, 133.8, 131.8, 131.6, 127.1, 126.8, 126.8, 125.8, 125.1, 123.8, 25.0; IR (KBr) 3048, 3030, 2965, 2919, 2870, 2823, 2723, 2357, 2339, 1587, 1487, 1439, 1395, 1364, 1348, 1101, 1070, 983, 953, 889, 833, 751, 702; ESMS calcd for C36H25N4 [M + H]+ 513.2, found 513.2.

10,15-Bis(2,4-dimethylphenyl)-3,6-dimethylbenzo[i]-dipyrido[3,2-a:2′,3′-c]phenazine (Me2(2,4-Me2Ph2)dppn, 6).

Compound 6 was prepared using the general procedure for Suzuki cross coupling reactions from 4 (204 mg, 0.394 mmol), 2,4-dimethyl phenyl boronic acid (150 mg, 1.00 mmol), PdCl2 (7 mg, 0.04 mmol), PPh3 (21 mg, 0.080 mmol), and K2CO3 (221 mg, 1.60 mmol). The reaction mixture was cooled to rt, diluted with ethyl acetate (10 mL), and washed with a saturated solution of aqueous NaHCO3 (3 × 10 mL). The organic layer was separated, dried with anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated. The crude product was purified by column chromatography on neutral alumina (7% EtOAc/hexanes) to give the pure compound 6 (124 mg, 0.217 mmol, 55%) as an orange solid: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.95 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.89 (dt, J = 6.2, 3.0 Hz, 2H), 7.55–7.43 (m, 4H), 7.35–7.22 (m, 6H), 2.91 (s, 6H), 2.58 (s, 6H), 1.98 (d, J = 3.4 Hz, 6H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 161.3, 147.4, 140.4, 137.4, 136.5, 135.9, 133.6, 133.5, 132.1, 130.9, 130.9, 129.8, 129.7, 126.7, 125.7, 125.2, 125.1, 123.8, 25.0, 20.7, 19.8; IR (KBr) 3064, 2996, 2948, 2919, 2855, 2728, 2363, 2343, 1684, 1612, 1587, 1542, 1507, 1489, 1458, 1425, 1364, 1348, 1301, 1201, 1180, 1130, 1122, 1072, 1033, 982, 956, 812, 766, 752, 722, 689, 638; ESMS calcd for C40H33N4 [M + H]+ 569.3, found 569.3.

10,15-Bis(2,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-3,6-dimethylbenzo[i]-dipyrido[3,2-a:2′,3′-c]phenazine (Me2(2,4-(MeO)2Ph2)dppn, 7).

Compound 7 was prepared using the general procedure for Suzuki cross coupling reactions from 4 (208 mg, 0.401 mmol), 2,4-dimethoxy phenyl boronic acid (182 mg, 1 mmol), PdCl2 (7 mg, 0.04 mmol), PPh3 (21 mg, 0.080 mmol), and K2CO3 (221 mg, 1.60 mmol) which are added to a pressure tube. Water (4 mL), ethanol (6 mL), and toluene (8 mL) were added, and argon gas was purged. After it was cooled to rt, the reaction mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2 (12 mL) and washed with a saturated solution of aqueous NaHCO3 (3 × 12 mL). The organic layer was separated, dried with anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated. The crude product was extracted by stirring with EtOAc/hexanes (10 mL, 1:1) for 3 h to give 7 (142 mg, 56%) as an orange solid: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.01 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 8.02 (dd, J = 6.9, 3.3 Hz, 2H), 7.54–7.34 (m, 6H), 6.81 (ddt, J = 13.6, 5.5, 2.4 Hz, 4H), 4.03 (s, 6H), 3.64 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 6H), 2.92 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 161.60, 161.29, 160.93, 159.31, 159.26, 133.80, 127.63, 127.53, 126.45, 124.84, 104.20, 104.14, 99.58, 98.79, 77.32, 77.00, 76.68, 55.67, 55.57, 29.69; IR (KBr) 3065, 3034, 2998, 2951, 2934, 2834, 2361, 2342, 2332, 1608, 1581, 1509, 1458, 1436, 1364, 1349, 1302, 1280, 1259, 1208, 1169, 1156, 1130, 1120, 1072, 1036, 955, 832, 766, 752, 660, 637; ESMS calcd for C40H33N4O4 [M + H]+ 633.2, found 633.2.

General Procedure Complex Synthesis [Ru(tpy)(L)(py)](PF6)2 Complexes (L = 5–7).

[Ru(tpy)Cl3], Ardppn ligands (L), and LiCl were added to a pressure tube. Ethanol and water were added, and the mixture was deoxygenated by bubbling Ar through a submerged needle for 20 min. Et3N was added, and the pressure tube was sealed and heated to 80 °C for 16 h. The reaction mixture was cooled to rt and concentrated, and the residue was purified by column chromatography on neutral alumina to give [Ru(tpy)(L)(Cl)](Cl) as red solids. A solution of [Ru(tpy)(L)Cl]Cl in EtOH was treated with pyridine. Water was added, and the mixture was deoxygenated by bubbling Ar through a submerged needle for 20 min. The pressure tube was sealed and heated to 80 °C for 16 h. The reaction mixture was cooled to rt and concentrated, and the residue was purified by column chromatography on alumina to give [Ru(tpy)(L)(py)](Cl)2 complexes. Anion metathesis was accomplished by dissolving this compound in a minimal amount of H2O and treating it with a saturated aqueous solution of NH4PF6 to give the final compound that was isolated by filtration and dried in vacuo to give [Ru(tpy)(L)(py)](PF6)2 complexes.

[Ru(tpy)(Ph2Me2dppn)(py)](PF6)2 (8).

Compound 8 was synthesized using the general procedure for complex synthesis starting from [Ru(tpy)Cl3] (57 mg, 0.13 mmol), 5 (92 mg, 0.18 mmol), LiCl (28 mg, 0.65 mmol), EtOH (11 mL), water (5.5 mL), and Et3N (0.22 mL, 1.6 mmol). The residue was purified by column chromatography on neutral alumina (2% MeOH/CH2Cl2) to give [Ru(tpy)(Ph2Me2dppn)(Cl)](Cl) as a red solid (83 mg, 70%): 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 9.23 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 8.60 (dd, J = 8.1, 4.0 Hz, 3H), 8.49 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 8.11 (dd, J = 8.2, 4.6 Hz, 2H), 8.09–8.00 (m, 2H), 7.94–7.86 (m, 4H), 7.75 (qd, J = 7.5, 6.6, 3.6 Hz, 3H), 7.68–7.64 (m, 2H), 7.63–7.55 (m, 5H), 7.55–7.51 (m, 2H), 7.25 (ddd, J = 7.3, 5.6, 1.3 Hz, 2H), 7.16 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 3.47 (s, 3H), 1.70 (s, 3H); ESMS calcd for C51H35N7Ru [M2+] 423.5998, found 423.5557. The intermediate [Ru(tpy)(Ph2Me2dppn)Cl]Cl (41 mg, 0.045 mmol) was treated with EtOH (5 mL), pyridine (0.014 mL, 0.18 mmol), and water (5 mL). The residue was purified by column chromatography on alumina (3–4%MeOH in DCM) to give [Ru(tpy)(Ph2Me2dppn)(py)](Cl)2 (30 mg, 67%). Anion metathesis gave [Ru(tpy)(Ph2Me2dppn)(py)](PF6)2 (8, 30 mg, 83%) as a black solid: 1H NMR (400 MHz, acetonitrile-d3) δ 9.25 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 8.75 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 8.52 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 8.44 (dt, J = 7.9, 1.1 Hz, 2H), 8.24–8.12 (m, 4H), 8.07–8.02 (m, 3H), 7.99–7.96 (m, 2H), 7.85–7.77 (m, 5H), 7.74–7.64 (m, 8H), 7.61–7.59 (m, 2H), 7.41–7.36 (m, 2H), 7.26 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.12–7.06 (m, 1H), 2.19 (s, 3H), 1.68 (s, 3H); IR (KBr) 2924, 2853, 2802, 2661, 2361, 2342, 1490, 1449, 1420, 1389, 1361, 1348, 1299, 1285, 1240, 1208, 1142, 1072, 1032, 953, 839, 768, 702, 670; UV–vis λmax 489 nm (ε = 11400 M−1 cm−1); ESMS calcd for C56H40F6N8PRu [M+] 1071.2, found 1071.2; anal. calcd for C56H44F12N8O2P2Ru (8·2H2O) C 53.72, H 3.54, N 8.95; found C 53.96, H 3.82, N 8.82.

[Ru(tpy)(Me2(2,4-Me2Ph2)dppn)(py)](PF6)2 (9).

Compound 9 was synthesized using the general procedure for complex synthesis starting from [Ru(tpy)Cl3] (62 mg, 0.14 mmol), 6 (120 mg, 0.2 mmol), LiCl (30 mg, 0.7 mmol), EtOH (12 mL), water (6 mL), and Et3N (0.24 mL, 1.7 mmol). The residue was purified by column chromatography on neutral alumina (2% MeOH/CH2Cl2) to give [Ru(tpy)(Me2(2,4-Me2Ph2)dppn)(Cl)](Cl) as a red solid (83 mg, 70%): 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 9.23 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 8.68–8.57 (m, 3H), 8.50 (t, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 8.11 (t, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 8.02–7.81 (m, 6H), 7.56 (hept, J = 5.1 Hz, 2H), 7.46 (s, 1H), 7.38–7.17 (m, 8H), 3.47 (s, 3H), 2.61 (s, 3H), 2.49 (s, 3H), 2.02 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 3H), 1.89 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 3H), 1.73 (s, 3H); ESMS calcd for C55H43ClN7Ru [M+] 938.2, found 938.2. The intermediate [Ru(tpy)((Me2(2,4-Me2Ph2)dppn)Cl]Cl was treated with EtOH (6 mL), pyridine (0.013 mL, 0.16 mmol), and water (6 mL). The residue was purified by column chromatography on alumina (3–4%MeOH in DCM) to give [Ru(tpy)(Me2(2,4-Me2Ph2)dppn)(py)](Cl)2 (30 mg, 71%): 1H NMR (400 MHz, methanol-d4) δ 9.33 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 8.82 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 8.72 (dt, J = 7.7, 4.6 Hz, 2H), 8.67–8.60 (m, 2H), 8.25 (t, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 8.18–8.05 (m, 5H), 7.92–7.84 (m, 2H), 7.80–7.72 (m, 3H), 7.63–7.57 (m, 2H), 7.51–7.42 (m, 3H), 7.37–7.32 (m, 4H), 7.26 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 2H), 7.17 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 2.61 (s, 3H), 2.50 (s, 3H), 2.25 (s, 3H), 2.03 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 3H), 1.92 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 3H), 1.74 (s, 3H). Anion metathesis gave [Ru(tpy)((Me2(2,4-Me2Ph2)dppn)(py)](PF6)2 (9, 32 mg, 75%) as a black solid: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3CN) δ 9.20 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 8.71 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 8.56–8.38 (m, 6H), 8.19 (t, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 8.04 (dd, J = 16.0, 7.4 Hz, 4H), 7.97–7.89 (m, 3H), 7.72 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.67–7.57 (m, 4H), 7.52 (s, 1H), 7.40 (s, 4H), 7.32–7.24 (m, 4H), 7.09 (q, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H), 2.64 (s, 3H), 2.53 (s, 3H), 2.18 (s, 3H), 2.11 (s, 3H), 2.06 (s, 3H), 1.68 (s, 3H); IR (KBr) 3073, 3032, 2922, 2854, 2361, 2342, 1671, 1604, 1507, 1490, 1422, 1388, 1349, 1302, 1285, 1236, 1143, 1061, 1015, 994, 957, 840, 767, 740, 699; UV–vis λmax 487 nm (ε = 12000 M−1 cm−1); ESMS calcd for C60H48F6N8PRu [M+] 1127.2, found 1127.2; anal. calcd for C60H54F12N8O3P2Ru (9·3H2O) C 54.34, H 4.10, N 8.45, found C 54.29, H 4.17, N 8.38.

[Ru(tpy)(Me2(2,4-(MeO)2Ph2)dppn)(py)](PF6)2 (10).

Compound 10 was synthesized using the general procedure for complex synthesis starting from [Ru(tpy)Cl3] (48 mg, 0.11 mmol), 7 (95 mg, 0.15 mmol), LiCl (23 mg, 0.55 mmol), EtOH (8 mL), water (4 mL), and Et3N (0.18 mL, 1.3 mmol). The residue was purified by column chromatography on neutral alumina (2% MeOH/CH2Cl2) to give [Ru(tpy)((2,4-(MeO)2Ph2)dppn))(Cl)](Cl) as a red solid (41 mg, 36%): 1H NMR (400 MHz, methanol-d4) δ 9.28 (dd, J = 8.3, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 8.70–8.57 (m, 3H), 8.52–8.46 (m, 2H), 8.10 (dt, J = 8.1, 3.9 Hz, 2H), 7.99–7.85 (m, 6H), 7.55–7.47 (m, 2H), 7.42–7.32 (m, 1H), 7.30–7.15 (m, 4H), 6.96 (t, J = 2.7 Hz, 1H), 6.88 (dt, J = 8.3, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.81 (dd, J = 6.3, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.72 (ddd, J = 15.8, 8.3, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 4.05 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 3H), 3.93 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 3H), 3.69 (dd, J = 11.9, 2.4 Hz, 3H), 3.55 (dd, J = 14.6, 2.4 Hz, 3H), 3.46 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 3H), 1.70 (d, J = 14.4 Hz, 3H); HRMS (ESMS) calcd for C55H43ClN7O4Ru [M]+ 1002.2, found 1002.2. The intermediate [Ru(tpy)((2,4-(MeO)2Ph2)dppn))Cl]Cl (35 mg, 0.034 mmol) was treated with EtOH (5 mL), pyridine (0.010 mL, 0.14 mmol), and water (5 mL). The residue was purified by column chromatography on alumina (3–4% MeOH in DCM) to give [Ru(tpy)((2,4-(MeO)2Ph2)dppn))(py)](Cl)2 (30 mg, 79%): 1H NMR (400 MHz, methanol-d4) δ 9.40 (dd, J = 8.4, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 8.88 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 8.72 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 8.64 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 8.29–8.22 (m, 1H), 8.11 (td, J = 9.4, 8.7, 5.5 Hz, 4H), 7.98 (dd, J = 13.2, 7.1 Hz, 2H), 7.80–7.72 (m, 3H), 7.60–7.52 (m, 2H), 7.51–7.43 (m, 3H), 7.45–7.26 (m, 4H), 7.23–7.14 (m, 2H), 7.01–6.89 (m, 2H), 6.87–6.77 (m, 2H), 4.06 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 3H), 3.99–3.90 (m, 3H), 3.74–3.66 (m, 3H), 3.63–3.56 (m, 3H), 2.29–2.24 (m, 3H), 1.74 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 3H). Anion metathesis gave [Ru(tpy)((2,4-(MeO)2Ph2)dppn)(py)](PF6)2 (10, 27 mg, 82%) as a black solid: 1H NMR (400 MHz, acetonitrile-d3) δ 9.29 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 8.79 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 8.53 (dd, J = 9.1, 4.4 Hz, 2H), 8.47–8.42 (m, 2H), 8.19 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 8.03 (dd, J = 12.4, 7.5 Hz, 6H), 7.72 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.62 (dd, J = 11.4, 5.9 Hz, 4H), 7.38 (p, J = 7.7, 7.0 Hz, 3H), 7.28 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.10 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 7.02 (t, J = 3.2 Hz, 1H), 6.96 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 6.89 (s, 1H), 6.84 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 4.08 (s, 3H), 3.98 (s, 3H), 3.74 (d, J = 11.9 Hz, 3H), 3.62 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 3H), 2.18 (s, 3H), 1.69 (s, 3H); IR (KBr) 2928, 2841, 2360, 2342, 1607, 1578, 1509, 1497, 1449, 1418, 1389, 1349, 1302, 1283, 1262, 1209, 1156, 1108, 1081, 1032, 955, 840, 768, 741, 699, 669; UV–vis λmax 487 nm (ε = 10600 M−1 cm−1); ESMS calcd for C60H48F6N8O4PRu [M+] 1191.2, found 1191.2; anal. calcd for C60H52F12N8O6P2Ru (10·2H2O) C 52.52, H 3.82, N 8.17; found C 52.39, H 4.00, N 8.21.

LogP.

Solutions of 1 and 8–10 were prepared in octanol (2 mL, 100 μM) and combined with deionized water (2 mL) in glass vials. The vials were capped, wrapped in aluminum foil, shaken (5 min), and allowed to settle (24 h). After 24 h, relative concentrations of 1 and 8–10 in the water and octanol layers were determined spectrophotometrically using absorbance values at 490 nm. LogP was calculated using the quotient of the absorbance at 490 nm in octanol over the absorbance at 490 nm in water.

EC50 Determinations.

MDA-MB-231 cells or DU-145 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at the density of 7000 cells per well in 100 μL of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 10% FBS and 1000 units/mL penicillin/streptomycin. Each plate was incubated in a 37 °C humidified incubator ventilated with 5% CO2 overnight (16 h). The media was aspirated from each well, and quadruplicate wells were treated with media containing 1 and 8–10 (100 μM–100 nM) in 1% DMSO. Plates also contained blank wells with no cells and control wells with media containing 1% DMSO. After 1 h of incubation at 37 °C, plates were irradiated using a blue LED light source (see the Supporting Information, tirr = 15 min, λirr = 460–470 nm, 170 J/cm2) or left in the dark and incubated for either 4 or 72 h in a 37 °C humidified incubator ventilated with 5% CO2. After incubation, MTT reagent (10 μL, 5 mg/mL in PBS) was added to each well, and plates were kept at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 2 h. The media was aspirated from each well, and DMSO (100 μL) was added. The wells were shaken for 30 min to allow for the solvation of the formazan crystals. Absorbance at 570 nm was measured in each well. Average absorbance values for the blank wells were subtracted from absorbance values for each sample to eliminate the background. Viability data were obtained by averaging normalized absorbance values for untreated cells and expressing absorbance for the treated samples as percent control. EC50 values were determined using Igor Pro graphing software.

Flow Cytometry Analysis.

MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded at 250000 cells/plate in five 60 mm2 cell culture dishes containing 3 mL of DMEM treated with 10% FBS and 1000 units/mL penicillin/streptomycin. After seeding, the cells were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 overnight (18 h). After incubation, two plates were treated with compound 1 (10 μM) or 9 (20 μM) in media (1% DMSO) and set to incubate at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 1 h. The remaining two plates were treated with DMEM containing 1% DMSO and placed in the incubator. Following incubation, plates were irradiated using a blue LED light source (see the Supporting Information, tirr = 15 min, λirr = 460–470 nm, 170 J/cm2) or left in the dark. These plates were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 4 h. After 4 h incubation, both the irradiated and nonirradiated plates were removed from the incubator. In a separate plate, after 2 h, cells treated with vehicle alone had media removed and replaced with H2O2 (500 mM) in PBS. Cells were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 3 h. The media from each plate was saved in a 15 mL falcon tube. The cells were detached from each plate via trypsinization and added to the previously removed media. The cells were centrifuged (600 g, 5 min) to pellet the cells. The supernatant was decanted, and the pellet was washed twice with PBS (4 mL). After the final wash, the supernatant was decanted, and the pellet was suspended in PBS (100 μL). A solution of Annexin V (5 μL, 1 mg/mL) was added to the cell suspension. The suspension was incubated at rt (15 min). After incubation, PBS was added (1 mL) to the tube and the suspension was centrifuged (600 g, 5 min). The supernatant was decanted, and cells were suspended in PBS (100 μL). A solution of propidium iodide (5 μL, 12 μM) was added to the cell suspension and incubated at rt (15 min). The cell suspension was diluted with PBS (1 mL). The suspension was passed through a metal mesh filter (30 μm) from Celltrics (Kobe, Hyogo Prefecture, Japan) into a small sample tube. Flow cytometric analysis was performed on a Sysmex Cyflow Space fluorescence-assisted cell sorter. Data were processed using FCS Express.fcs processing software by De Novo software (Boulder, Co).

ROS Scavenging.

MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at the density of 7000 cells per well in DMEM (100 μL) containing 10% FBS and 1000 units/mL penicillin/streptomycin and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 overnight. Each plate contained blank wells containing no cells and control wells with cells containing media and 1% DMSO. Noncontrol or nonblank wells were treated with compound 1 (10 μM) or 9 (20 μM) in media (1% DMSO) containing either NaN3 (50 mM), mannitol (50 mM), histidine (50 mM), or N-acetyl cysteine (5 mM) in quadruplicate. Plates were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 1 h and irradiated using a blue LED light source (see the Supporting Information, tirr = 15 min, λirr = 460–470 nm, 170 J/cm2) for 15 min. After 4 h incubation, MTT assay was used to assess viability as described above.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Synthesis and Structural Characterization.

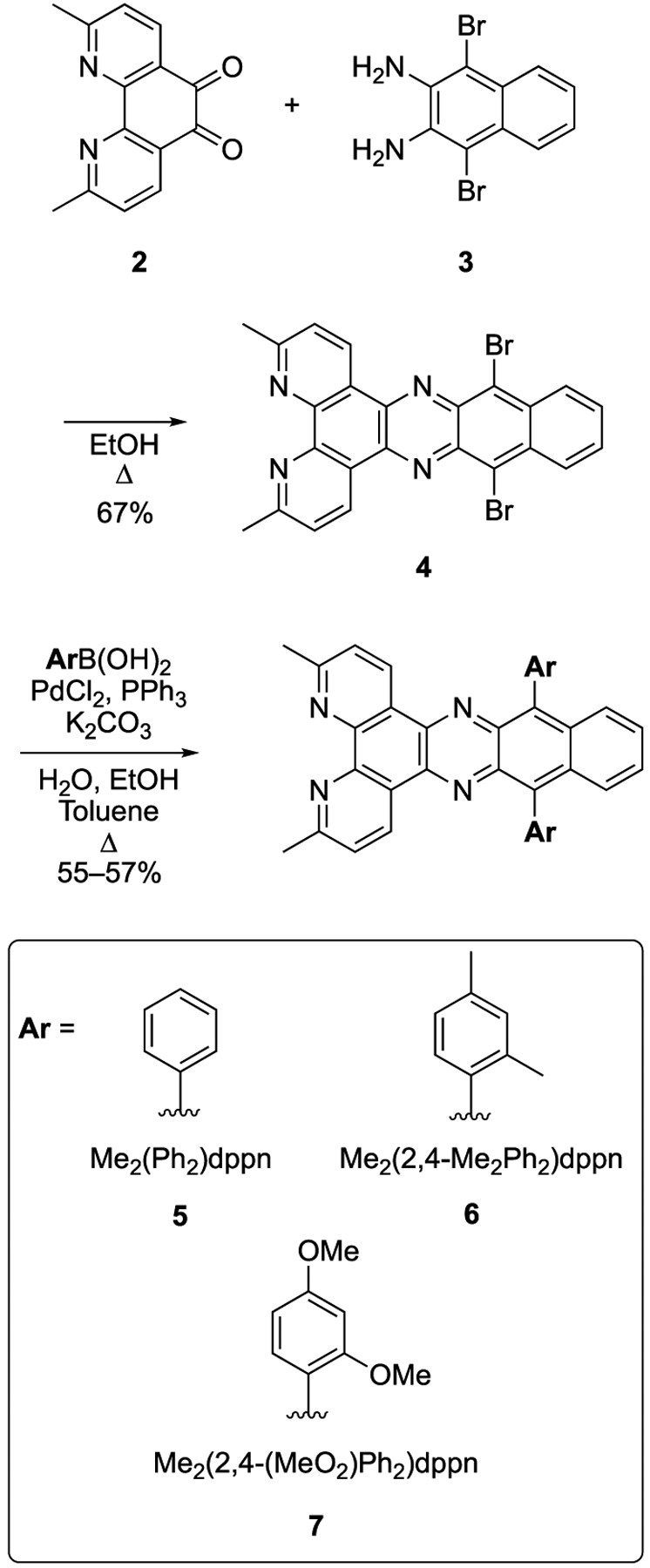

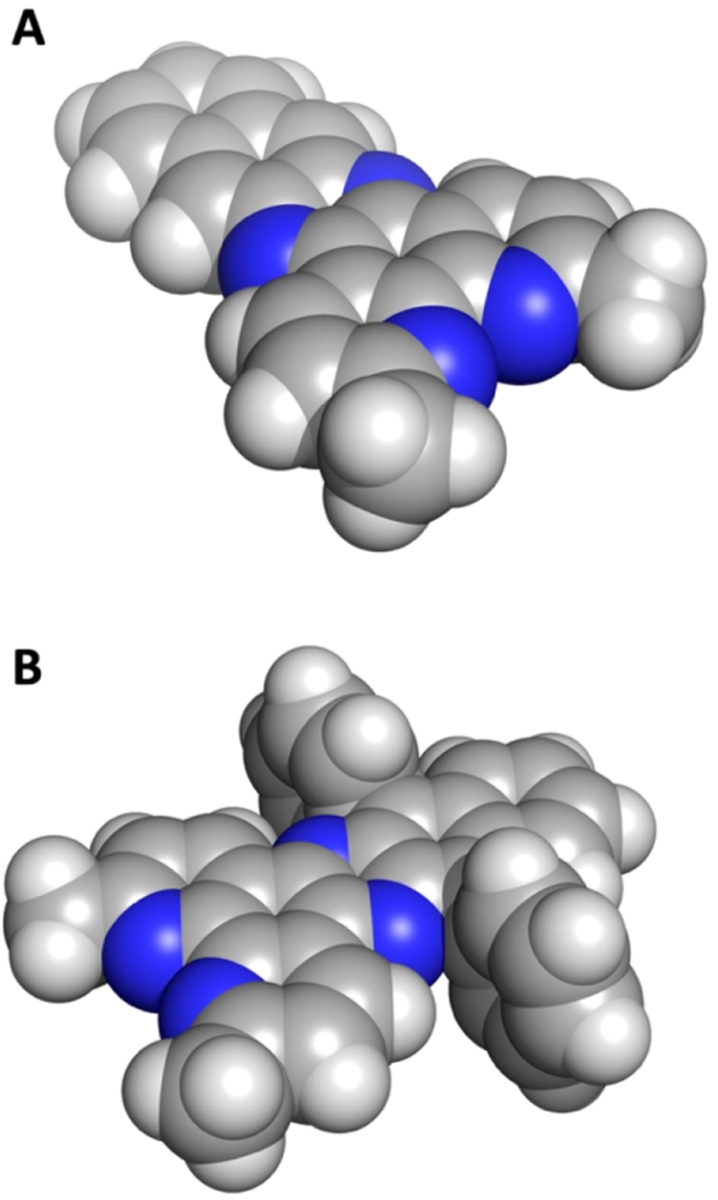

A literature search revealed that derivatives of dppn were limited to brominated (Br2dppn), quinone (qdppn), and trialkylsilylalkyne derivatives ((i-Pr3SiCC)2dppn) (Figure 2). Prior investigations with trialkylsilylalkyne derivatives used Sonogashira cross coupling reactions with 4,9-dibromonaphtho[2,3-c][1,2,5]thiadiazole to install alkyne substituents.62 Subsequent reduction with LiAlH4, followed by condensation of the resultant diamine with 1,10-phenanthroline-5,6-dione, gave trialkylsilylalkyne dppn derivatives functionalized in the 10-and 15-positions. Although this synthetic sequence provided the ligands in good overall yields, this strategy required a multistep synthesis to access each new dppn derivative. Instead of using early stage cross coupling reactions with 4,9-dibromonaphtho[2,3-c][1,2,5]thiadiazole, we envisioned a divergent approach, where new aryl substituents could be introduced at the latest stage, after formation of the dppn ring system. This new strategy required the synthesis of Br2Me2dppn (4). Compound 4 was accessed by condensation of 2,9-dimethyl-1,10-phenanthroline-5,6-dione (2)63 with 1,4-dibromonaphthalene-2,3-diamine (3),43 which is available in one step via bromination of 2,3-diaminonapthalene (Scheme 1).61 Suzuki cross coupling of 4 with three aryl boronic acids provided the diphenyl (5), di(2,4-dimethylphenyl) (6), and di(2,4-dimethoxyphenyl) (7) substituted ligands in one step from 4 in good yields (55–57%). Ligands 5–7 were chosen to probe steric and electronic effects in their respective Ru(II) complexes. Diphenyl derivative 5 was designed to act as a standard. Introducing the 2-methyl group, as shown with 6, was expected to minimize overlap of the dppn and phenyl π-systems due to allylic strain (Figure 3). In addition, the 2- and 4-methyl groups on the phenyl groups of 6 were expected to provide a mild electron-donating effect and also increase lipophilicity and solubility of resultant Ru(II) complexes. The 2,4-dimethoxy substituents on ligand 7 were not only expected to provide stronger electron donation than the methyl groups of 6 but were also expected to minimize overlap of the dppn and phenyl π-systems due to allylic strain and increase solubility. Attempts were also made to couple 2,4,6-trimethylphenyl boronic acid with 4 using the same coupling conditions and other protocols for sterically demanding Suzuki reactions. However, complex mixtures were obtained, with no evidence of dual coupling by 1H NMR spectroscopy or ESMS. The inability to obtain product from 2,4,6-trimethylphenyl boronic acid is likely due to the steric environment of the bromides in 4, with ortho C–H and N functional groups, which is highly crowded.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Aryl-Substituted dppn Derivatives 5–7

Figure 3.

Space-filling models of the ligands (A) Me2dppn (1) and (B) Me2(Ph)2dppn (5).

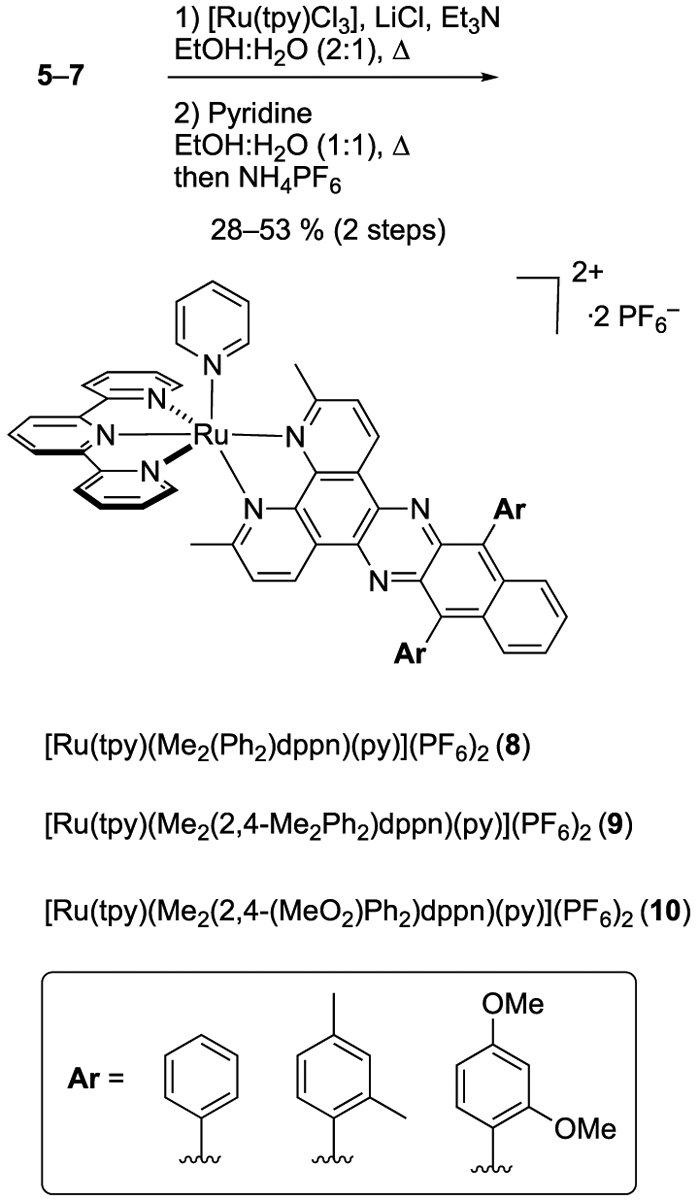

Three Ru(II) complexes derived from the arylated ligands 5–7 were prepared using a two-step synthetic procedure starting from [Ru(tpy)Cl3] (Scheme 2). Treating 5–7 with [Ru(tpy)(Cl)3], LiCl, and Et3N in a mixture of EtOH and H2O at 80 °C provided access to chloride complexes with the general formula [Ru(tpy)(L)(Cl)]Cl, where L = 5–7. Subsequent treatment of these salts with excess pyridine (4.0 equiv) in 1:1 EtOH/H2O, followed by salt metathesis with NH4PF6, provided the final complexes 8–10 containing monodentate pyridines with the general formula [Ru(tpy)(L)(py)](PF6)2, where L = 5–7 in 28–53% yield over two steps.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Ruthenium Complexes of the General Formula [Ru(tpy)(L)(Py)](PF6)2 (8–10), where L = Aryl-Substitued dppn Derivatives 5–7

Ru(II) complexes were characterized by 1H NMR, IR, and electronic absorption spectroscopies, electrospray mass spec-trometry, and elemental analysis. A key feature noted in the 1H NMR spectra of 8–10 is the loss of symmetry that occurs upon binding of ligands 5–7 to the Ru(II) center. For instance, the 1H NMR spectrum of ligand 5 shows one resonance in the aliphatic region assigned to the 3- and 6-methyl groups; in contrast, the 1H NMR spectrum of complex 8 shows two resonances for methyl groups, similar to 1, which arise from the different chemical environments of the two methyl groups upon coordination to the [Ru(tpy)(py)]2+ fragment. Spectra for ligands 6 and 7 show three singlets in the aliphatic region (~4.1–1.9 ppm) integrating for six protons each, which are assigned to NMR equivalent methyl groups that are related by a C2 axis and mirror plane that bisects the nitrogen atoms of 5–7. Complexes 9 and 10 each show six resonances integrating for three protons each from 4.2–1.5 ppm, which are assigned to the six methyl groups in the complexes that each are in different chemical environments. Interestingly, resonances for methoxy groups of 10 at ~3.6 and ~3.4 ppm appear as overlapping broad singlets that collectively integrate for three protons each. The splitting of these resonances into two peaks is consistent with the presence of cis and trans atropisomers, which would be expected to undergo slow interconversion on the NMR time scale, due to the crowded steric environment of the Ar–C(Me2dppn) bond (Figure S2). ESMS spectra of complexes 8–10 show major molecular ions with suitable isotopic distributions at 1071.2, 1127.2, and 1191.2, which are consistent with cations [[Ru(tpy)(5)(py)](PF6)]+, [[Ru(tpy)(6)(py)](PF6)]+, and [[Ru(tpy)(7)(py)](PF6)]+, respectively.

Photophysical Properties and Photochemistry.

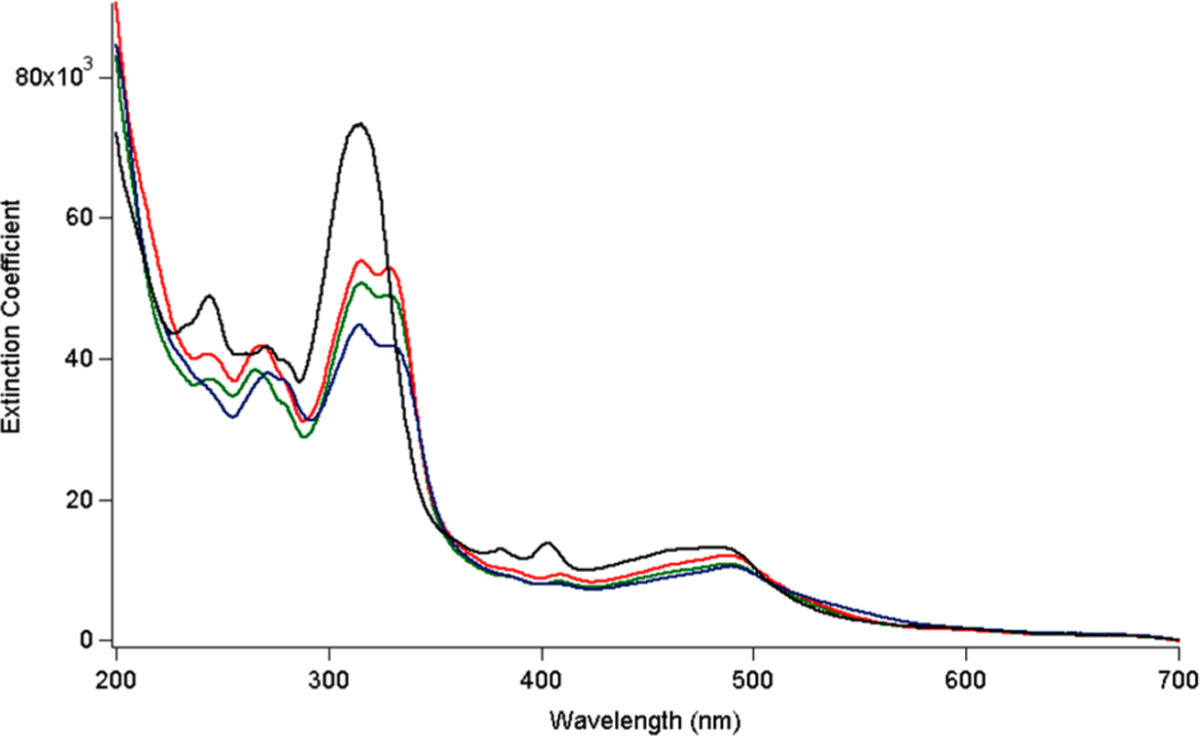

Complexes 8–10 in MeOH exhibit strong electronic absorption in the visible region, with peaks that tail out to ~700 nm, as depicted in Figure 4. Importantly, the spectral profiles of complexes 8–10 are similar to those of 1 (Figure 4). Ligand-centered 1ππ* transitions associated with the py and tpy ligands are observed in the 200–350 nm range, as previously reported for the related complexes [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(py)]2+ and [Ru(tpy)(dppn)(py)]2+.14,15 Dppn-centered 1ππ* absorption features at ~400 are also observed for 1 and 8–10, consistent with the similarity of the electronic structure of this ligand.14,15,27 In addition, the maxima of the broad Ru(dπ) → tpy(π*) metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT) bands of 8–10 appear at ~480–490 nm, at a similar position to that of 1 and related Ru(II)-dppn complexes.14,15,27,30

Figure 4.

Electronic absorption spectra of 1 (black), 8 (green), 9 (red), and 10 (blue) in MeOH.

It should also be noted that a red shift in the 1MLCT absorption is not observed across the series, indicating that the attachment of the aryl groups does not significantly shift the absorption to longer wavelengths, as expected from related complexes with substitutions to the distal portion of the dppz and dppn ligands.64–69 It has been established that in this type of complexes the 1MLCT transition observed with high intensity takes place from the Ru-centered HOMO to a molecular orbital on the dppz or dppn ligand with electron density proximal to the metal owing to greater spatial overlap.64–69 Although a lower energy MLCT state from the Ru to the distal fragment of the ligand is present, its optical density is negligible, such that substitutions to this part of the dppn or dppz ligand do not result in marked changes in energy or intensity to the absorption in the visible range.64–69

Irradiation of 8 – 10 in MeCN with λirr = 500 nm results in the exchange of the monodentate pyridine ligand for the coordinating solvent, whereas no exchange is observed under similar experimental conditions in the dark over a period of at least 22 h. The ligand exchange processes for 8, 9, and 10 in MeCN occur with quantum yields (Φ500) of 0.13(4), 0.13(3), and 0.13(2), respectively, more efficiently than nonarylated Me2dppn derivatives 1 and [Ru(tpy)(Me2dppn)(imatinib)]2+ (Table 1). The reason for the greater ligand exchange quantum yields of 8–10 is not readily apparent and is still under investigation. In addition to photoinduced ligand exchange, 8, 9, and 10 produce 1O2 following visible light irradiation with quantum yields, ΦΔ, of 0.62(3), 0.61(3), and 0.56(4), respectively, all of which are slightly lower than that of 1 (Table 1). The reduced efficiency of 1O2 production may be attributed to competitive population of the competing 3MC (metal-centered) state(s) in 8–10 as compared to 1, as evidenced by higher ligand exchange quantum yields.

Table 1.

Quantum Yields for Ligand Exchange (Φ500) and 1O2 Production Singlet Oxygen (ΦΔ) for 1, 8–10, and Related Ru(II) Complexes, and Their Octanol–Water Partition Coefficients (LogP)

| compound | Φ500a | ΦΔb | LogPc |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.053(1)15 | 0.69(9)15 | −0.27 ± 0.06 |

| 8 | 0.13(4) | 0.62(3) | 0.11 ± 0.01 |

| 9 | 0.13(3) | 0.61(3) | 0.32 ± 0.03 |

| 10 | 0.13(2) | 0.56(4) | 0.23 ± 0.03 |

| [Ru(tpy)(Me2dppn) (imatinib)]2+ | 0.073(1)72 | 0.57(7)72 | NDd |

MeCN, λirr = 500 nm.

MeOH, λirr = 460 nm, 435 long-pass filter.

Shake flask method, 298 ± 3 K; results are the average of three independent experiments, and errors are standard deviations.

Not determined.

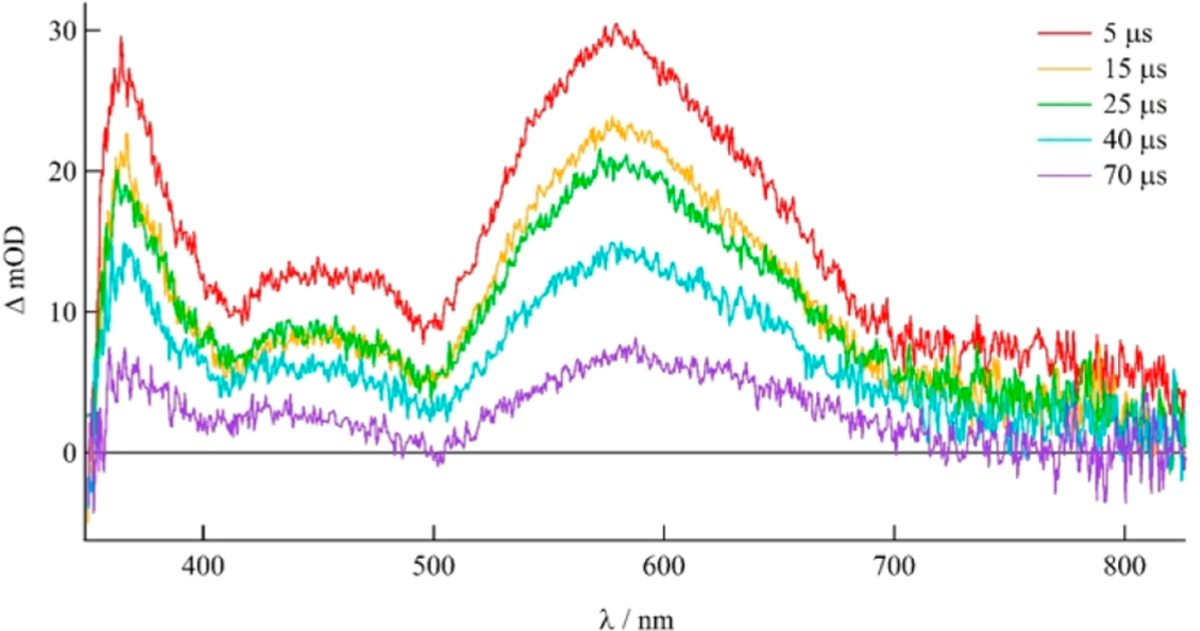

The excited state dynamics of 8–10 were investigated using nanosecond transient absorption (TA) spectroscopy in pyridine to preclude the formation of a new product stemming from ligand photosubstitution with the solvent. The TA spectrum of 8 in deaerated pyridine, shown in Figure 5, features strong positive signals centered at ~365 and 580 nm that decay monoexponentially with τ = 47 μs (λexc = 500 nm, fwhm = 8 ns). TA spectra with similar features were collected for 9 and 10 with lifetimes of 50 and 46 μs, respectively (Figures S6–S7). The strong signal at ~580 nm is known to be associated with the population of the dppn-localized 3ππ* excited state, in this case on the arylated Me2dppn ligand, and is consistent with TA spectra and lifetimes reported for other Ru(II) complexes containing the dppn ligand such as 1 (τ = 47 μs), [Ru(tpy)(dppn)(py)]2+ (τ = 50 μs), and [Ru(bpy)2(dppn)]2+ (τ = 33 μs).15,66,70 The existence of a long-lived excited state is necessary for the efficient bimolecular energy transfer to ground state 3O2 to produce cytotoxic 1O2. Similar excited state lifetimes in 1 and 8–10 demonstrate that the aryl substitutions on the Me2dppn ligand do not significantly affect the electronic or photophysical properties of the complex.

Figure 5.

Transient absorption spectrum of 8 in deaerated pyridine (λexc = 500 nm, 5.9 mJ/pulse, fwhm = 8 ns).

DNA Binding.

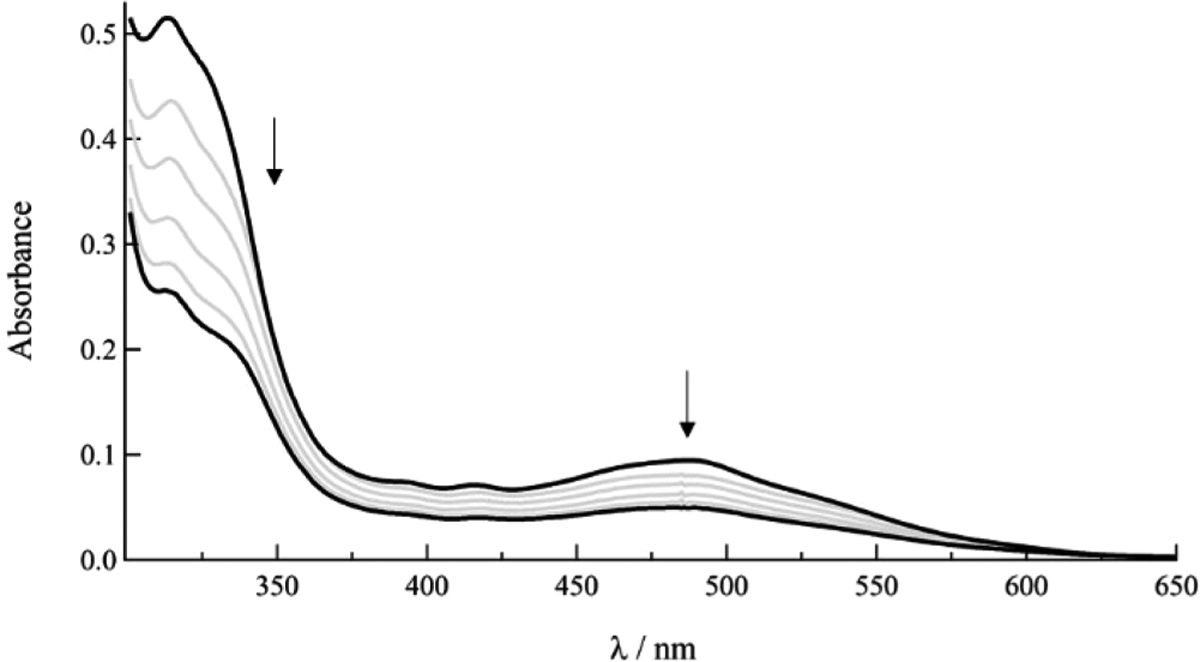

A number of techniques are typically required to understand the mode of binding between metal complexes and DNA, including spectrophotometric titrations, relative viscosity measurements, and thermal denaturation. Upon intercalation to DNA, the electronic absorption spectrum of a complex containing a ligand with an extended π-system exhibits hypochromism and modest bathochromism due to π-stacking interactions between the complex and the DNA bases.71,72 The titration of DNA up to 100 μM bases to 5 μM solutions of 8–10 resulted in hypochromic shifts of the MLCT transition of 16% in 8, 38% in 9, and 36% in 10 and no discernible bathochromic shifts. (Figures 6, S3–S5).

Figure 6.

Changes in the electronic absorption spectrum of 8 (10 μM) after addition of 0, 20, 40, 60, 100, and 200 μM DNA bases to solution (5 mM Tris, 50 mM NaCl, pH 7.0).

It should be noted that changes in absorption upon the addition of DNA are known to be associated with π-stacking interactions, such as intercalation, but similar spectral shifts are also observed upon self-aggregation, enhanced aggregation in the presence of the polyanion, and other hydrophobic interactions in the major and minor groove of DNA. The addition of polystyrene sulfonate (PSS) to cationic complexes has been previously used to probe the role of random coil polyanion on aggregation without the possibility of intercalation.58 The electronic absorption spectra of 5 μM solutions of 8–10, upon addition of 100 μM PSS, exhibit hypochromicity but to a lesser extent than 100 μM DNA bases (Figures S3–S5). These results demonstrate that there is some π-stacking interaction in the presence of both polyanions, likely enhanced by electrostatic interactions between the cationic Ru(II) complexes and the anionic backbones of PSS and DNA, such that they cannot be assigned to intercalation between DNA base pairs.58 Similar changes in absorption following addition of PSS are observed as a result of self-aggregation, as well as aggregation induced by the polyanion, as previously shown for cationic dirhodium complexes with dppz ligands.58 Given the number of equilibria possible in solution with similar spectral changes, a binding constant cannot be determined from absorption titration measurement, as is typically calculated for these type of complexes and other intercalators.73–75

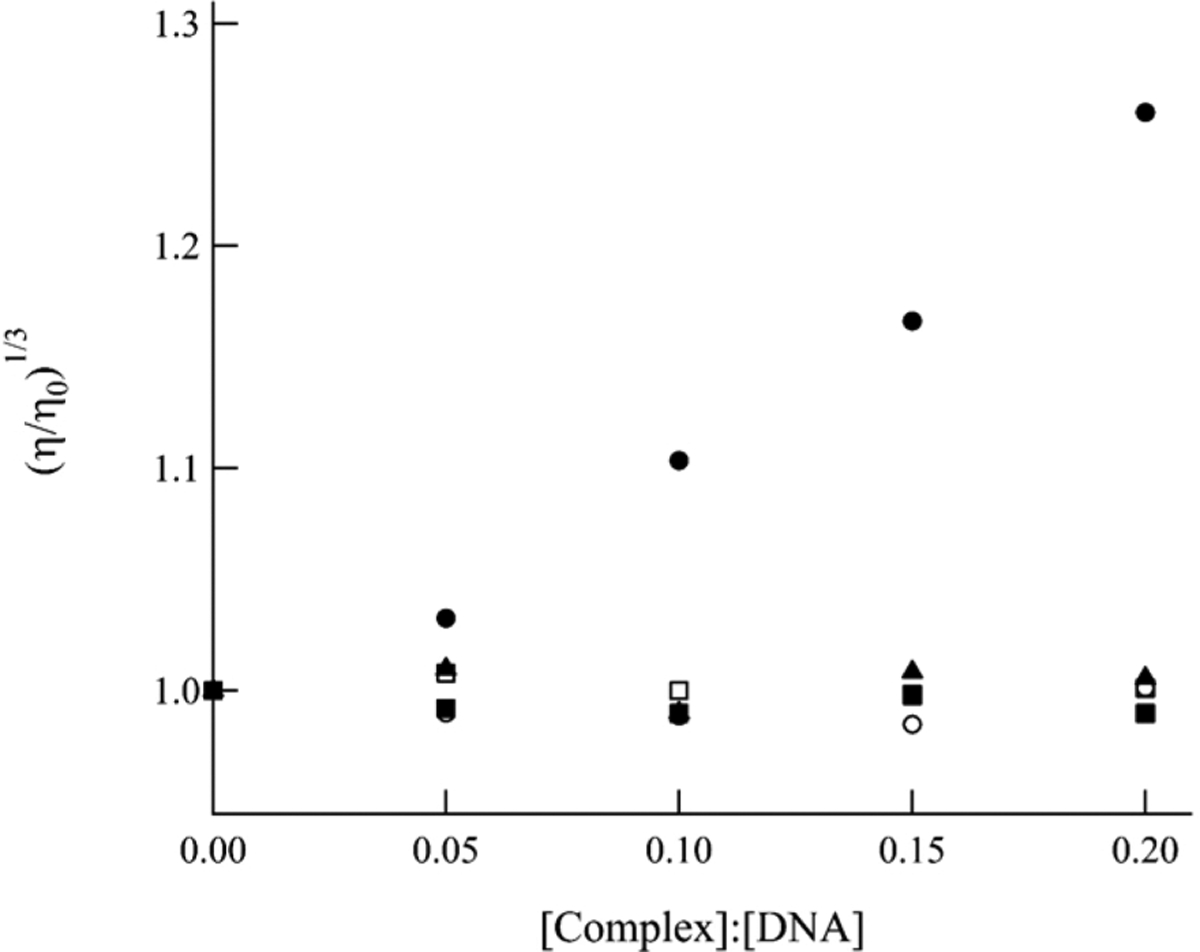

Two other important methods for the characterization of intercalation of organic molecules and inorganic complexes are the measurement of the changes in the DNA melting temperature (thermal denaturation) and the relative viscosity of DNA solutions in the presence of the probe. Attempts to obtain DNA melting temperatures in the presence of 8–10 were unsuccessful due to the decomposition of the complexes at temperatures above 60 °C. Electrostatic interactions between cationic metal complexes and the anionic phosphate backbone of DNA do not affect the viscosity of a DNA solution. In contrast, the intercalation of a molecule between the π-stacked bases of a duplex is known to unwind and elongate the cylindrical double helix DNA structure, thus increasing the viscosity relative to DNA alone.72,76 Figure 7 shows the changes of the relative viscosity of DNA solutions as a function of the concentration of ethidium bromide (EtBr), a known DNA intercalator, and complexes 8–10. Figure 7 also displays data for [Ru(bpy)3]2+, a complex that exhibits weak electrostatic interactions with the phosphodiester backbone and is known to not intercalate between DNA bases.77 As expected, EtBr increases the viscosity of the DNA solution as the amount of probe in solution is increased, while [Ru(bpy)3]2+ has no detectible effect on DNA solution viscosity. Complexes 8–10 follow the same trend as [Ru(bpy)3]2+ as the concentration of complex in solution increases, having little to no effect on the viscosity of DNA solutions. These results are consistent with an electrostatic and/or hydrophobic interaction between 8–10 and DNA, including complex self-aggregation aided by the anionic backbone, but not intercalation between the DNA bases.

Figure 7.

Relative viscosity of DNA (200 μM bases) solutions as a function of increasing concentration of [Ru(bpy)3]2+ (■), 8 (□), 9 (▲), 10 (○), and ethidium bromide (●).

Biological Characterization.

Lipophilicity of compounds is often strongly correlated with the amount of cellular uptake. In general, the more lipophilic a compound is, the more able it is to penetrate the lipid bilayer of the outer plasma membrane. Although several passive and active forms of cellular uptake have been characterized for bioactive Ru(II) complexes,6 many studies have established a positive correlation between lipophilicity, cell uptake, and cytotoxicity.1 It is generally believed that increasing the lipophilicity of Ru(II) and related transition-metal complexes through the addition of hydrophobic groups will lead to higher potency for cell killing.1 In order to quantify lipophilicity, the partition coefficients (LogP) between water and octanol were determined for the parent Ru(II) complex 1, which contains Me2dppn, and the arylated derivatives 8–10 (Table 1). As predicted, the addition of aryl substituents onto the Me2dppn ligand significantly enhanced lipophilicity in Ru(II) complexes 8–10 versus complex 1. Complex 1 shows a small, but negative LogP value, indicating that it prefers to dissolve in water versus octanol by ~2:1 ratio. In contrast, complexes 8–10 all show positive LogP values and prefer dissolution in octanol. The most lipophilic compound in the series was 9, which contains the 2,4-dimethylphenyl groups, and is more lipophilic than 1 by over 1 order of magnitude. Complexes 10 and 8 showed lower LogP values than 9, which is consistent with the nature of their substituents; phenyl would be expected to be less hydrophobic than 2,4-dimethoxyphenyl, which is in turn more polar than 2,4-dimethylphenyl due to the added oxygen atoms.

Given the photochemical reactivity and lipophilicity of Ru(II) complexes 8–10, these compounds were evaluated alongside the parent Ru(II) complex 1 for growth inhibitory effects against MDA-MB-231 triple-negative breast cancer and DU-145 prostate cells, which are two aggressive cancer cell lines with high metastatic potential. Cells were treated with 1 or 8–10, incubated for 1 h, and then irradiated with a blue LED light source designed for 96 well plates (tirr = 15 min, λirr = 460–470 nm, 170 J/cm2). In parallel experiments, cells were treated in the same manner but were left in the dark. Effective concentrations to provide 50% growth inhibition (EC50) values were determined 72 h after irradiation was concluded using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay (Table 2, entries 1–4). Phototoxicity indexes (PIs), which are the ratio of dark EC50 to light EC50, were calculated for each complex and several trends were apparent in the data. First, complexes 8–10 all caused less potent growth inhibition against both MDA-MB-231 and DU-145 cell lines than 1 by a factor of 2–3. The Me2dppn derivative 1 was the most potent analog in both cell lines and showed a superior PI value in the MDA-MB-231 cell line relative to 8–10. Second, Ru(II) complexes 1 and 8–10 all showed lower EC50 values in the DU-145 prostate cancer cell line relative to MDA-MB-231 by a factor of roughly two. Third, PI values for 1, 8, and 10 were similar, >5, in the DU-145 cell line. Given the fact that 8–10 are unable to intercalate in DNA, but 1 is, it is clear that DNA intercalation is not a requirement for cancer cell toxicity or photoinduced cell death. Furthermore, EC50 values for 1 and 8–10 showed no correlation with LogP values (Table 1), indicating that increasing lipophilicity of these Ru(II) complexes does not lead to greater efficacy.

Table 2.

EC50 Values (μM) for 1 and 8–10 against MDA-MB-231 and DU-145 Cells at Times (tMTT) of 72 and 4 ha,b

| EC50/μM | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDA-MB-231 | DU-145 | |||||||

| entry | compound | tMTT/h | Light | Dark | PIc | Light | Dark | PIc |

| 1 | 1a,b | 72 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 34 ± 3 | 7.4 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 11 ± 6 | 5.5 |

| 2 | 8a,b | 72 | 13 ± 1 | 37 ± 5 | 2.8 | 6.5 ± 2.5 | 33 ± 6 | 5.1 |

| 3 | 9a,b | 72 | 8.6 ± 0.5 | 21 ± 2 | 2.4 | 6.0 ± 1.0 | 17 ± 1 | 2.8 |

| 4 | 10a,b | 72 | 16 ± 3 | 63 ± 10 | 3.9 | 5.3 ± 1.0 | 29 ± 8 | 5.5 |

| 5 | 1a,b | 4 | 6.0 ± 3.2 | >100 | >17 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | >100 | >56 |

| 6 | 9a,b | 4 | 18 ± 6 | 41 ± 11 | 2.3 | 7.2 ± 2.6 | 38 ± 13 | 5.3 |

Cells treated with compound 1 and 8–10 for 1 h, then irradiated (tirr = 15 min, λirr = 460–470 nm, 170 J/cm2) or left in the dark. Cell viabilities were determined by MTT 4 and 72 h after irradiation was complete. Data are the average of three independent experiments using quadruplicate wells, and errors are standard deviations.

PI = phototherapeutic index = ratio dark EC50/light EC50.

During experiments with 1 and 8–10, clear changes in cancer cell morphology from dendritic to rounded, granular, and detached were observed in cells treated with all compounds and light at time points as early as 4 h, well before the 72 h end point of the MTT assay. To probe for toxic effects on shorter time scales, EC50 determinations were repeated for 1 and 9, which were the most potent of the tested compounds, 4 h after irradiation was concluded (Table 2, entries 5 and 6). These data confirmed that 1 and 9 were able to produce an almost immediate toxic effect in both the MDA-MB-231 and DU-145 cell lines. PI values were much higher for 1 at 4 h than at 72 h in both cancer cell lines, with the highest value, PI > 56, in DU-145 cells. This large increase in PI values was due to the minimal amount of toxicity observed, as judged by MTT, at the highest concentrations tested. In both MDA-MB-231 and DU-145 cells, EC50 values for 1 at the 4 h time point were >100 μM. In contrast, complex 9 showed toxicity at 4 h in both cell lines in the dark. The EC50 value for 9 in the dark in DU-145 cells was roughly double that observed at 72 h, which raised the PI from 2.8 at 72 h to 5.3 at 4 h.

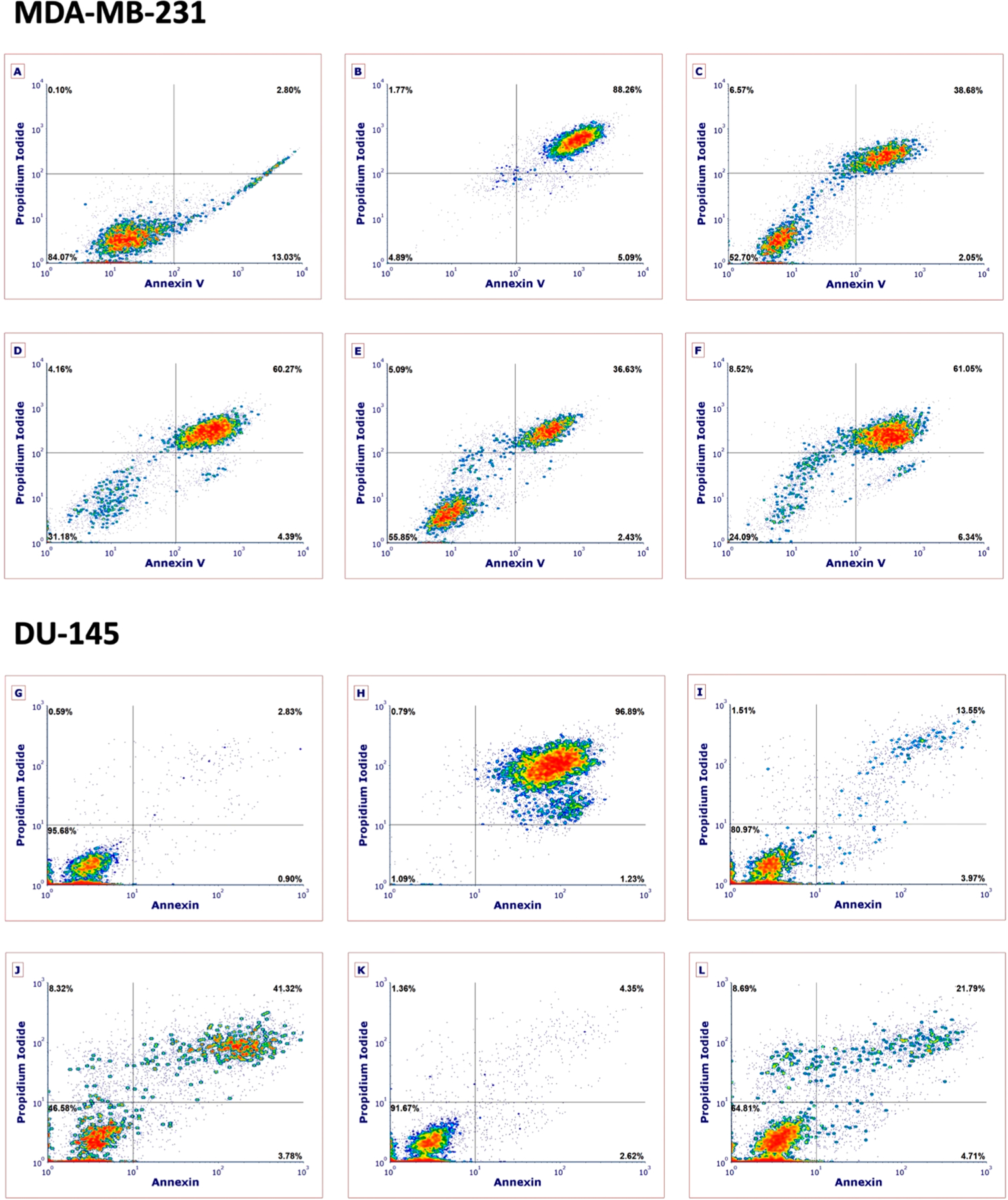

Although many Ru(II) complexes have shown promising activity in cancer cell lines, few investigations have probed the time scale or mechanism by which these complexes cause cell death.78–92 With the exception of two complexes derived from nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs that showed an approximately equal amount of apoptosis and necrosis,84 most Ru(II) complexes induce apoptosis as the dominant mechanism of cell death. Data with 1 and 9 show that early, photoactivated cell death is achieved in both triple-negative breast and prostate cancer cell lines. Except for dark toxicity observed with 1 at 72 h, data in Table 2 indicate that most of the cytotoxic effect of 1 and 9 are realized after only 4 h. Because of its programmed nature, death by apoptosis usually occurs on a longer time scale and requires at least 24 h before major metabolic changes occur that are evident by assays such as MTT. On the other hand, necrosis can occur almost immediately after compound treatment.93 To probe the mechanism of cell death, complexes 1 and 9 were evaluated against the MDA-MB-231 and DU-145 cell lines by flow cytometric analysis (Figure 8). Cells were treated with vehicle (1% DMSO), 1 (10 μM), or 9 (20 μM) for 1 h and then were treated with light (tirr = 15 min, λirr = 460–470 nm, 170 J/cm2) or left in the dark (Figure 4). In parallel experiments, MDA-MB-231 and DU-145 cells were treated with 500 mM H2O2, which causes rapid necrosis and serves as a positive control (Figure 8B, 8H). Cells were stained 4 h after conclusion of the irradiation with Annexin V, an antibody that recognizes the translocation of phosphatidylserine from the inner to the outer leaflet of the cell plasma membrane that is strongly associated with apoptosis, and propidium iodide, a cell-impermeable dye that is only able to enter cells after integrity of the plasma membrane is compromised. Because necrosis is accompanied by permeabilization of the outer plasma membrane, substantial uptake of propidium iodide is strongly associated with necrosis. Cells that show positive Annexin V staining and are negative for propidium iodide are considered apoptotic, whereas cells that stain for both dyes are considered necrotic because rupture of the plasma membrane allows entry of propidium iodide and Annexin V into cells. Data for 1 and 9 in both MDA-MB-231 and DU-145 cells indicate that necrosis is the primary mode of cell death at 4 h. In all cases, cells treated with 1 or 9 that are Annexin V positive and propidium iodide negative (apoptotic, lower right-hand quadrant) account for a minimal amount (<7%) of the total cell population. Cells treated with 1 or 9 in the light show substantial populations of cells that are Annexin V and propidium iodide positive, as high as 61% with treatment of MDA-MB-231 cells with 1 (10 μM) and light (Figure 8C). In both cell lines, treatment with light results in a substantial increase (~30%) of Annexin V and propidium iodide positive cells that is consistent with necrosis. Higher populations of cells showing little to no propidium iodide uptake or Annexin V uptake (normal, lower left-hand quadrant) were observed in cells treated with 1 or 9 in the dark. Given that 1 is not toxic in MDA-MB-231 cells at a concentration of 10 μM in the dark as judged by MTT (Table 2, entry 5) yet some amount of Annexin V and propidium iodide staining is observed (Figure 8C), staining may be facilitated by fusion of dye-containing aggregates of 1 with the MDA-MB-231 cells.94 Indeed, Ru(II) complexes derived from dppn and related ligands are known to aggregate in solution.95,96 Analysis of 1 and 8–10 in PBS buffer by dynamic light scattering indicated that particles ranging in size from 100–300 nm are present in solution (Figure S22). Taken together, these data confirm that treatment of MDA-MB-231 and DU-145 cells with 1 or 9 and light leads to substantial populations of necrotic cells, with minimal apoptosis.

Figure 8.

Flow cytometric analysis of MDA-MB-231 (A–F) and DU-145 (G–L) cells after 4 h treatment with 1 or 9 under dark and light (tirr = 15 min, λirr = 460–470 nm, 170 J/cm2) conditions using Annexin V/propidium iodide staining. Treatment conditions: (A) vehicle and light; (B) H2O2 (500 mM), 3 h treatment; (C) 1 (10 μM) dark; (D) 1 (10 μM) light; (E) 9 (20 μM) dark; (F) 9 (20 μM) light; (G) vehicle and light; (H) H2O2 (500 mM), 3 h treatment; (I) 1 (10 μM) dark; (J) 1 (10 μM) light; (K) 9 (20 μM) dark; (L) 9 (20 μM) light. Data are indicative of three independent experiments. See the Supporting Information for more details.

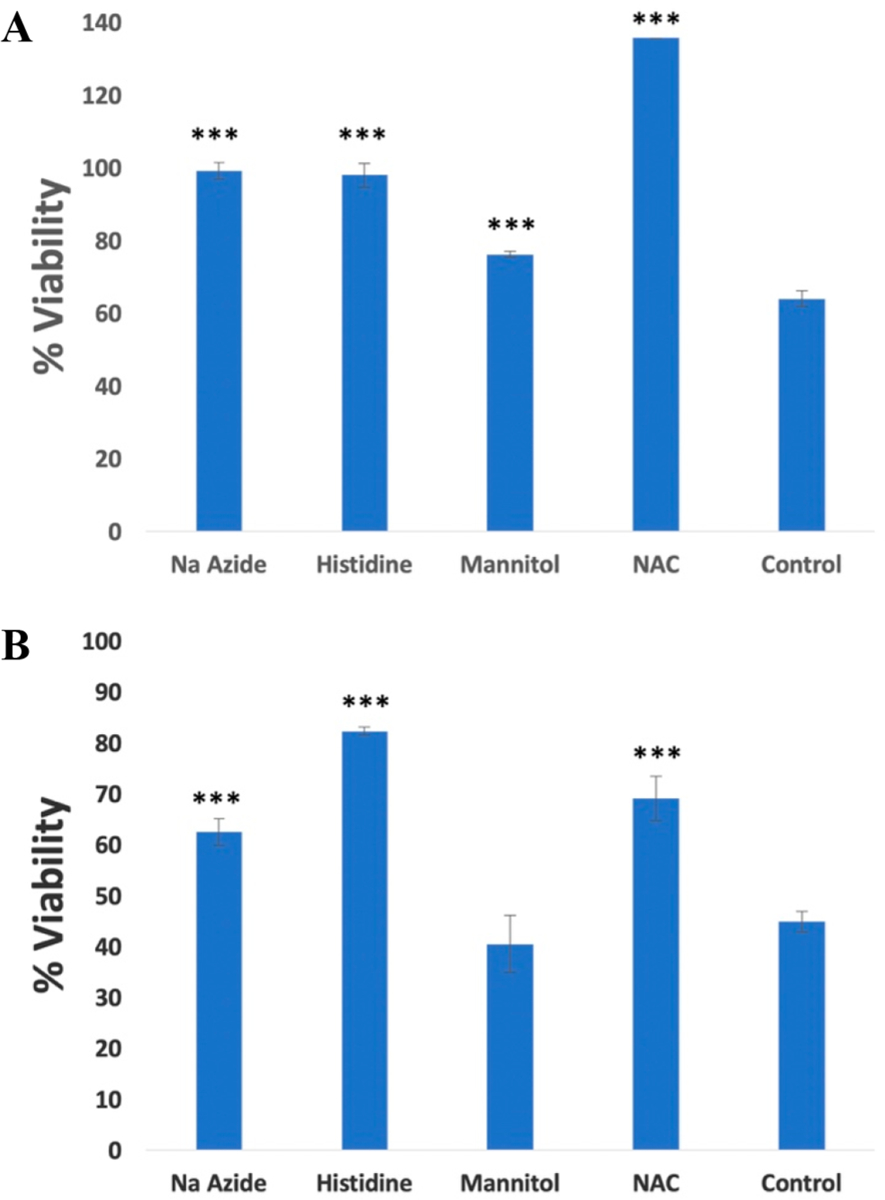

Data in this manuscript show that Ru(II) complexes 1 and 8–10 are dual-action agents that show efficient photodissociation (PCT) and photosensitization (PDT) from the same molecular entity. Photochemical generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is the principle mode of action for PDT agents. With most investigations that describe new Ru(II)-based PDT agents, it is often assumed that cell-free assays that are used to detect the photochemical generation of ROS translate to ROS-induced death in cells. Although there are some exceptions,39 researchers rarely use cell-based assays to probe the role that ROS have in photoactivated death. The time scale of viability loss and flow cytometric data are both consistent with 1 and 9 causing necrotic cell death. In order to gain further insight into the mechanism of necrotic cell death, several ROS quenchers were examined for their ability to block cytotoxicity in MDA-MB-231 cells at 4 h. Cells were pretreated with sodium azide (50 mM), a quencher of singlet oxygen, histidine (50 mM), a quencher of hydroxyl radical that also scavenges singlet oxygen to a lesser extent than sodium azide,97 and D-mannitol (50 mM), a hydroxyl radical scavenger. In addition, cells were pretreated with the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine (NAC, 5 mM),98 which counteracts oxidative stress in cells by increasing the ratio of reduced to oxidized glutathione. After pretreatment with ROS scavengers for 1 h, cells were treated with 1 (10 μM) or 9 (20 μM) near their 4 h EC50 values, incubated for 1 h, and were treated with light (tirr = 15 min, λirr = 460–470 nm, 170 J/cm2) or were left in the dark. Viability was determined by the MTT assay 4 h after irradiation was complete. Data for cells treated with light are shown in Figure 9; cells treated in the dark showed minimal evidence of toxicity (viabilities >90%). All four ROS scavengers provided significant levels of rescue in MDA-MB-231 cells treated with 1 and light (Figure 9A). Cells pretreated with the 1O2 scavengers sodium azide and histidine showed viabilities near 100%, indicating nearly full rescue, which strongly suggests that Type II photosensitization (1O2) plays a crucial role in the cell death mechanism. In addition, cells treated with 1 showed a lesser, but statistically significant (p < 0.01), level of rescue (~20%) with D-mannitol, a hydroxyl radical scavenger, which implicates hydroxyl radical and Type I photosensitization in cell death by 1. Pretreatment with NAC also provided a strong rescue of cells treated by 1 and light that reached a level above 100% relative to cells treated with vehicle, light, and no ROS scavenger. These data indicate that blocking of oxidative stress, presumably by increasing the ratio of reduced to oxidized glutathione in the cells, is enough to counteract the photochemical generation of ROS by 1. Levels of viability greater than 100% can be observed by MTT due to increased activity of oxidoreductases that drive reduction of MTT using NADH, whose concentration in cells is sensitive to the amount of reduced glutathione present.99 In contrast with data for 1, where large levels of rescue by ROS scavengers was observed, MDA-MB-231 cells treated with 9 (20 μM) underwent smaller (<30%), but statistically significant (p < 0.01), levels of rescue with sodium azide, histidine, and NAC (Figure 9B). These data are consistent with Type II photosensitization being partially responsible for necrotic cell death. Cells pretreated with d-mannitol showed no rescue versus control cells treated with 9, light, and no scavenger, which rules out Type I photosensitization. Overall, complex 1 caused death at lower concentrations with higher phototherapeutic indexes than 9, and several types of ROS (1O2, hydroxyl radical) were implicated in necrotic cell death.

Figure 9.

Cell viabilities of MDA-MB-231 determined by MTT 4 h after light treatment using pretreatment with ROS scavengers NaN3 (50 mM), mannitol (50 mM), histidine (50 mM), and N-acetylcysteine (5 mM) and either vehicle of (A) 1 (10 μM) or (B) 9 (20 μM). Cells were incubated with ROS scavenger for 1 h before light treatment (tirr = 15 min, λirr = 460–470 nm, 170 J/cm2). Data are representative of three independent experiments; error bars are standard deviations of quadruplicate samples. ***p < 0.01 and relates cells treated with no scavenger (control) to cells treated with ROS scavenger.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, we report the synthesis and photochemical and biological characterization of a novel series of Ru(II) complexes that contain π-expansive ligands and a dual-action PCT/PDT mode of action. A late-stage synthetic method was developed to introduce flanking aryl groups onto the dppn π-system that blocks the ability of resultant Ru(II) complexes to intercalate in DNA and enhances lipophilicity. However, introduction of the aryl substituents does not strongly influence the spectral or photophysical properties of the Ru(II) complexes versus the parent derivative 1. Despite the fact that 8–10 are not intercalators, the complexes associate with DNA in an electrostatic manner. Quantum yields for dissociations of monodentate pyridines by 8–10 were ~3 times higher than 1 and quantum yields for singlet oxygen generation were ~10% lower. Higher quantum efficiencies for photoactivated ligand dissociation observed for 8–10 versus 1 makes these complexes attractive for PCT applications. The overall similarity of spectral and photophysical properties of 1 and 8–10 is likely due to the presence of minimal overlap between the π-system of the dppn ligand and the 10- and 15-aryl substituents, which is enforced by a crowded steric environment. Biological evaluation of 1 and 8–10 in breast and prostate cancer cells indicated that preventing intercalation did not abolish bioactivity. Complexes 8–10 showed photoactivated death in both cell lines, although EC50 values were higher and photochemotherapeutic indexes were lower than data observed for 1. Collectively, these data indicate that intercalation is not necessary to achieve bioactivity, although it may enhance cell killing. In all cases cytotoxicity was promoted by ROS, particularly 1O2. Investigations into the time scale and mechanism of cell death by 1 and 8–10 defined necrosis, rather than apoptosis, as the mechanism of cell death that occurs as early as 4 h after treatment with compounds and light. Importantly, cell death by necrosis can overcome resistance to apoptotic agents100 and promote antitumor immunity.101–104

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the National Institutes of Health (EB 016072), the National Science Foundation (CHE 1800395), and Wayne State University for support of this research. For instrumentation support, we thank the Hütteman laboratory, the NSF (0840413), and Penrose Therapeutx.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b03585.

Spectral data for 4–10; DNA titration data for 9 and 10; transient absorption spectra for 9 and 10; DLS and time-resolved UV–vis data for 8–10 (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b03585

REFERENCES

- (1).Poynton FE; Bright SA; Blasco S; Williams DC; Kelly JM; Gunnlaugsson T The development of ruthenium(II) polypyridyl complexes and conjugates for in vitro cellular and in vivo applications. Chem. Soc. Rev 2017, 46, 7706–7756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).White JK; Schmehl RH; Turro C An overview of photosubstitution reactions of Ru(II) imine complexes and their application in photobiology and photodynamic therapy. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2017, 454, 7–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Heinemann F; Karges J; Gasser G Critical Overview of the Use of Ru(II) Polypyridyl Complexes as Photosensitizers in One-Photon and Two-Photon Photodynamic Therapy. Acc. Chem. Res 2017, 50, 2727–2736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Bonnet S Why develop photoactivated chemotherapy? Dalton Trans 2018, 47, 10330–10343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Puckett CA; Barton JK Mechanism of Cellular Uptake of a Ruthenium Polypyridyl Complex. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 11711–11716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Puckett CA; Ernst RJ; Barton JK Exploring the cellular accumulation of metal complexes. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 1159–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Mulcahy SP; Li S; Korn R; Xie X; Meggers E Solid-phase synthesis of tris-heteroleptic ruthenium(II) complexes and application to acetylcholinesterase inhibition. Inorg. Chem 2008, 47, 5030–5032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Meggers E Targeting proteins with metal complexes. Chem. Commun 2009, 1001–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Respondek T; Sharma R; Herroon MK; Garner RN; Knoll JD; Cueny E; Turro C; Podgorski I; Kodanko JJ Inhibition of Cathepsin Activity in a Cell-Based Assay by a Light-Activated Ruthenium Compound. ChemMedChem 2014, 9, 1306–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Ramalho SD; Sharma R; White JK; Aggarwal N; Chalasani A; Sameni M; Moin K; Vieira PC; Turro C; Kodanko JJ; Sloane BF Imaging sites of inhibition of proteolysis in pathomimetic human breast cancer cultures by light-activated ruthenium compound. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0142527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Garner RN; Gallucci JC; Dunbar KR; Turro C [Ru(bpy)2(5-cyanouracil)2]2+ as a Potential Light-Activated Dual-Action Therapeutic Agent. Inorg. Chem 2011, 50, 9213–9215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Respondek T; Garner RN; Herroon MK; Podgorski I; Turro C; Kodanko JJ Light Activation of a Cysteine Protease Inhibitor: Caging of a Peptidomimetic Nitrile with RuII(bpy)2. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 17164–17167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Sears RB; Joyce LE; Ojaimi M; Gallucci JC; Thummel RP; Turro C Photoinduced ligand exchange and DNA binding of cis-[Ru(phpy)(phen)(CH3CN)2]+ with long wavelength visible light. J. Inorg. Biochem 2013, 121, 77–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Knoll JD; Albani BA; Durr CB; Turro C Unusually Efficient Pyridine Photodissociation from Ru(II) Complexes with Sterically Bulky Bidentate Ancillary Ligands. J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118, 10603–10610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Knoll JD; Albani BA; Turro C New Ru(II) Complexes for Dual Photoreactivity: Ligand Exchange and 1O2 Generation. Acc. Chem. Res 2015, 48, 2280–2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Wachter E; Heidary DK; Howerton BS; Parkin S; Glazer EC Light-activated ruthenium complexes photobind DNA and are cytotoxic in the photodynamic therapy window. Chem. Commun 2012, 48, 9649–9651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Havrylyuk D; Deshpande M; Parkin S; Glazer EC Ru(II) complexes with diazine ligands: electronic modulation of the coordinating group is key to the design of ″dual action″ photoactivated agents. Chem. Commun 2018, 54, 12487–12490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Bahreman A; Limburg B; Siegler MA; Bouwman E; Bonnet S Spontaneous Formation in the Dark, and Visible Light-Induced Cleavage, of a Ru-S Bond in Water: A Thermodynamic and Kinetic Study. Inorg. Chem 2013, 52, 9456–9469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Lameijer LN; Ernst D; Hopkins SL; Meijer MS; Askes SHC; Le Devedec SE; Bonnet S A Red-Light-Activated Ruthenium-Caged NAMPT Inhibitor Remains Phototoxic in Hypoxic Cancer Cells. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2017, 56, 11549–11553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Yin H; Stephenson M; Gibson J; Sampson E; Shi G; Sainuddin T; Monro S; McFarland SA In Vitro Multiwavelength PDT with 3IL States: Teaching Old Molecules New Tricks. Inorg. Chem 2014, 53, 4548–4559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Sainuddin T; McCain J; Pinto M; Yin H; Gibson J; Hetu M; McFarland SA Organometallic Ru(II) Photosensitizers Derived from π-Expansive Cyclometalating Ligands: Surprising Theranostic PDT Effects. Inorg. Chem 2016, 55, 83–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Wang L; Yin H; Jabed MA; Hetu M; Wang C; Monro S; Zhu X; Kilina S; McFarland SA; Sun W π-Expansive Heteroleptic Ruthenium(II) Complexes as Reverse Saturable Absorbers and Photosensitizers for Photodynamic Therapy. Inorg. Chem 2017, 56, 3245–3259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Ghosh G; Colon KL; Fuller A; Sainuddin T; Bradner E; McCain J; Monro SMA; Yin H; Hetu MW; Cameron CG; McFarland SA Cyclometalated Ruthenium(II) Complexes Derived from α-Oligothiophenes as Highly Selective Cytotoxic or Photocytotoxic Agents. Inorg. Chem 2018, 57, 7694–7712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Smithen DA; Yin H; Beh MHR; Hetu M; Cameron TS; McFarland SA; Thompson A Synthesis and Photobiological Activity of Ru(II) Dyads Derived from Pyrrole-2-carboxylate Thionoesters. Inorg. Chem 2017, 56, 4121–4132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Monro S; Colon KL; Yin H; Roque J; Konda P; Gujar S; Thummel RP; Lilge L; Cameron CG; McFarland SA Transition Metal Complexes and Photodynamic Therapy from a Tumor-Centered Approach: Challenges, Opportunities, and Highlights from the Development of TLD-1433. Chem. Rev 2019, 119, 797–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Damrauer NH; Cerullo G; Yeh A; Boussie TR; Shank CV; McCusker JK Femtosecond Dynamics of Excited-State Evolution in [Ru(bpy)3]2+. Science 1997, 275, 54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Knoll JD; Albani BA; Turro C Excited state investigation of a new Ru(II) complex for dual reactivity with low energy light. Chem. Commun 2015, 51, 8777–8780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Castano AP; Demidova TN; Hamblin MR Mechanisms in photodynamic therapy: part one-photosensitizers, photochemistry and cellular localization. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther 2004, 1, 279–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Farrer NJ; Sadler PJ Photochemotherapy: Targeted Activation of Metal Anticancer Complexes. Aust. J. Chem 2008, 61, 669–674. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Arora K; Herroon M; Al-Afyouni MH; Toupin NP; Rohrabaugh TN; Loftus LM; Podgorski I; Turro C; Kodanko JJ Catch and Release Photosensitizers: Combining Dual-Action Ruthenium Complexes with Protease Inactivation for Targeting Invasive Cancers. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 14367–14380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Pena B; Leed NA; Dunbar KR; Turro C Excited state dynamics of two new Ru(II) cyclometallated dyes: relation to cells for solar energy conversion and comparison to conventional systems. J. Phys. Chem . C 2012, 116, 22186–22195. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Xu W; Wittich F; Banks N; Zink J; Demas JN; DeGraff BA Quenching of luminescent ruthenium(II) complexes by water and polymer-based relative humidity sensors. Appl. Spectrosc 2007, 61, 1238–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Sgambellone MA; David A; Garner RN; Dunbar KR; Turro C Cellular Toxicity Induced by the Photorelease of a Caged Bioactive Molecule: Design of a Potential Dual-Action Ru(II) Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 11274–11282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Pena B; David A; Pavani C; Baptista MS; Pellois J-P; Turro C; Dunbar KR Cytotoxicity Studies of Cyclometallated Ruthenium(II) Compounds: New Applications for Ruthenium Dyes. Organometallics 2014, 33, 1100–1103. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Lameijer LN; Hopkins SL; Breve TG; Askes SHC; Bonnet S d- Versus l-Glucose Conjugation: Mitochondrial Targeting of a Light-Activated Dual-Mode-of-Action Ruthenium-Based Anticancer Prodrug. Chem. - Eur. J 2016, 22, 18484–18491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Vidhisha S; Reddy KL; Kumar YP; Srijana M; Satyanarayana S Synthesis, characterization, antibacterial activity and investigation of DNA binding for Ru(II) molecular ″light switch″ complexes. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res 2014, 25, 197–205. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Lei W; Zhou Q; Jiang G; Zhang B; Wang X Photodynamic inactivation of Escherichia coli by Ru(II) complexes. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci 2011, 10, 887–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Liu Y; Hammitt R; Lutterman DA; Joyce LE; Thummel RP; Turro C Ru(II) Complexes of New Tridentate Ligands: Unexpected High Yield of Sensitized 1O2. Inorg. Chem 2009, 48, 375–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Zhao R; Hammitt R; Thummel RP; Liu Y; Turro C; Snapka RM Nuclear targets of photodynamic tridentate ruthenium complexes. Dalton Trans 2009, 251, 10926–10931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Sun Y; El Ojaimi M; Hammitt R; Thummel RP; Turro C Effect of Ligands with Extended π-System on the Photophysical Properties of Ru(II) Complexes. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 14664–14670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Loftus LM; White JK; Albani BA; Kohler L; Kodanko JJ; Thummel RP; Dunbar KR; Turro C New RuII Complex for Dual Activity: Photoinduced Ligand Release and 1O2 Production. Chem. - Eur. J 2016, 22, 3704–3708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Obare SO; Murphy CJ A Two-Color Fluorescent Lithium Ion Sensor. Inorg. Chem 2001, 40, 6080–6082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).McConnell AJ; Lim MH; Olmon ED; Song H; Dervan EE; Barton JK Luminescent Properties of Ruthenium(II) Complexes with Sterically Expansive Ligands Bound to DNA Defects. Inorg. Chem 2012, 51, 12511–12520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Monti F; Hahn U; Pavoni E; Delavaux-Nicot B; Nierengarten JF; Armaroli N Homoleptic and heteroleptic Ru(II) complexes with extended phenanthroline-based ligands. Polyhedron 2014, 82, 122–131. [Google Scholar]

- (45).Foxon SP; Green C; Walker MG; Wragg A; Adams H; Weinstein JA; Parker SC; Meijer AJHM; Thomas JA Synthesis, Characterization, and DNA Binding Properties of Ruthenium(II) Complexes Containing the Redox Active Ligand Benzo[i]dipyrido[3,2-a:2’,3′-c]phenazine-11,16-quinone. Inorg. Chem 2012, 51, 463–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Chesneau B; Hardouin-Lerouge M; Hudhomme P A Fused Donor-Acceptor System Based on an Extended Tetrathiafulvalene and a Ruthenium Complex of Dipyridoquinoxaline. Org. Lett 2010, 12, 4868–4871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Gao F; Chen X; Wang J-Q; Chen Y; Chao H; Ji L-N In Vitro Transcription Inhibition by Ruthenium(II) Polypyridyl Complexes with Electropositive Ancillary Ligands. Inorg. Chem 2009, 48, 5599–5601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Chang DM; Kim YS Novel heteroleptic ruthenium (II) complex with DPBPZ derivative for dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol 2012, 12, 5709–5712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Shilpa M; Nagababu P; Kumar YP; Latha JNL; Reddy MR; Karthikeyan KS; Gabra N; Satyanarayana S Synthesis, Characterization Luminiscence Studies and Microbial Activity of Ethylenediamine Ruthenium (II) Complexes with Dipyridophenazine Ligands. J. Fluoresc 2011, 21, 1155–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Zhou Q-X; Lei W-H; Chen J-R; Li C; Hou Y-J; Wang X-S; Zhang B-W A New Heteroleptic Ruthenium(II) Polypyridyl Complex with Long-Wavelength Absorption and High Singlet-Oxygen Quantum Yield. Chem. - Eur. J 2010, 16, 3157–3165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Sun Y; Joyce LE; Dickson NM; Turro C Efficient DNA photocleavage by [Ru(bpy)2(dppn)]2+ with visible light. Chem. Commun 2010, 46, 2426–2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Chen Y; Lei W; Jiang G; Zhou Q; Hou Y; Li C; Zhang B; Wang X A ruthenium(II) arene complex showing emission enhancement and photocleavage activity towards DNA from singlet and triplet excited states respectively. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 5924–5931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Ardhammar M; Lincoln P; Norden B Ligand Substituents of Ruthenium Dipyridophenazine Complexes Sensitively Determine Orientation in Liposome Membrane. J. Phys. Chem. B 2001, 105, 11363–11368. [Google Scholar]

- (54).Schatzschneider U; Niesel J; Ott I; Gust R; Alborzinia H; Woelfl S Cellular uptake, cytotoxicity, and metabolic profiling of human cancer cells treated with ruthenium(II) polypyridyl complexes [Ru(bpy)2(N-N)]Cl2 with N-N = bpy, phen, dpq, dppz, and dppn. ChemMedChem 2008, 3, 1104–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Montalti M; Credi A; Prodi L; Gandolfi MT Handbook of Photochemistry, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- (56).Rohrabaugh TN Jr.; Collins KA; Xue C; White JK; Kodanko JJ; Turro C New Ru(II) complex for dual photochemotherapy: release of cathepsin K inhibitor and 1O2 production. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 11851–11858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Nair RB; Teng ES; Kirkland SL; Murphy CJ Synthesis and DNA-Binding Properties of [Ru(NH3)4dppz]2+ . Inorg. Chem 1998, 37, 139–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Angeles-Boza AM; Bradley PM; Fu PKL; Wicke SE; Bacsa J; Dunbar KR; Turro C DNA Binding and Photocleavage in Vitro by New Dirhodium(II) dppz Complexes: Correlation to Cytotoxicity and Photocytotoxicity. Inorg. Chem 2004, 43, 8510–8519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Chaires JB; Dattagupta N; Crothers DM Studies on interaction of anthracycline antibiotics and deoxyribonucleic acid: equilibrium binding studies on the interaction of daunomycin with deoxyribonucleic acid. Biochemistry 1982, 21, 3933–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Jiang Y; Chen C-F Synthesis and structures of 1,10-phenanthroline-based extended triptycene derivatives. Synlett 2010, 2010, 1679–1681. [Google Scholar]

- (61).Tena A; Vazquez-Guillo R; Marcos-Fernandez A; Hernandez A; Mallavia R Polymeric films based on blends of 6FDA-6FpDA polyimide plus several copolyfluorenes for CO2 separation. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 41497–41505. [Google Scholar]

- (62).Wei P; Duan L; Zhang D; Qiao J; Wang L; Wang R; Dong G; Qiu Y A new type of light-emitting naphtho[2,3-c][1,2,5]thiadiazole derivatives: synthesis, photophysical characterization and transporting properties. J. Mater. Chem 2008, 18, 806–818. [Google Scholar]