Abstract

Ruminant livestock are a significant contributor to global methane emissions. Infectious diseases have the potential to exacerbate these contributions by elevating methane outputs associated with animal production. With the increasing spread of many infectious diseases, the emergence of a vicious climate–livestock–disease cycle is a looming threat.

Links between Infectious Disease and Climate Change

While the effects of climate change on the distribution and severity of infectious diseases are widely recognized [1], the inverse, how infectious agents contribute to climate change, is rarely considered. However, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is revealing that pathogens, via behavioral or physiological effects on hosts, can indirectly modulate global climate. For example, restrictions on travel and commerce in response to COVID-19 are projected to result in a ~8% drop in 2020 global CO2 emissions (https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-review-2020/global-energy-and-co2-emissions-in-2020). While this is an extreme example of the impacts infectious diseases can have on climate, many pathogens, ranging from other viruses to parasitic worms and bacteria, may also affect greenhouse gas emissions, albeit more subtly. One pathway by which such effects can occur involves animal methane emissions. Methane is a greenhouse gas with an effect on global warming 28–36 times more potent than CO2. In the last decade, atmospheric methane concentrations have increased rapidly and approximately half of this rise is associated with emissions from agricultural animals, particularly ruminant livestock [2]. Here we argue that ongoing changes in climate not only increase animal infectious diseases [1], but pathogens, in turn, can exacerbate animal methane production, resulting in a potentially vicious climate–disease cycle (Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Potential Positive Feedback Loop Arising from Interactions Among Climate, Infectious Diseases, and Methane Emissions.

Ongoing changes in climate are linked to increases in pathogen infections. Pathogens, such as gastrointestinal worms and the bacteria causing bovine mastitis (which affects the mammary glands), can increase net enteric methane emissions produced by livestock like sheep and dairy cows. Ultimately, this effect may feedback on climate, promoting a vicious cycle of climate change and infection.

How Livestock Disease Affects Methane

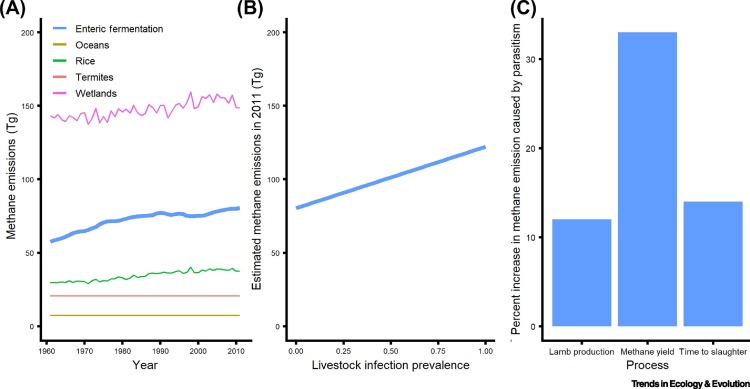

Sixty percent of all mammal biomass on Earth is livestock (e.g., cattle, pigs, sheep; [3]) and ruminant livestock account for nearly half of all biogenic methane emissions (Figure 2A). We estimate that pathogen-induced changes in these livestock methane emissions have the potential to increase methane inputs to the atmosphere by up to 50% (Figure 2B). This estimate is based on recent studies of parasitic worm infections in sheep, which show that these common parasites can elevate net methane emissions in animal production systems by increasing methane yield, reducing production efficiency, and lengthening the time it takes animals to reach production targets (Figure 2C) [4., 5., 6.]. For example, while individual lambs and ewes infected with the gastrointestinal (GI) worm Teladorsagia circumcincta produced less daily methane on average than uninfected controls [4,6], methane yield per kg dry matter intake was 33% higher in parasitized lambs [4]. Infected lambs also gained weight at only 4% of the rate of uninfected lambs and would thus require more time to reach target slaughter weight, resulting in greater lifetime methane production [4]. Likewise, in ewes, maternal weight loss and delayed weaning due to parasitism resulted in an 11% increase in methane emissions per kg lamb weight gain [6], meaning more methane production per weaned lamb. Crucially, recent models project that for livestock in certain regions, infection pressure from key GI worm species, including T. circumcincta, will increase with warming temperatures, largely due to accelerated parasite development during winter months [7]. In combination, these processes set the stage for unanticipated positive feedbacks (Figure 1).

Figure 2.

Contribution of Livestock to Methane Emissions and the Impact of Parasitism.

(A) Enteric fermentation from ruminant livestock is second only to wetlands as the most important living source of atmospheric methane. (B) Current estimates ignore effects of pathogens on methane release from livestock, but each percentage point increase in gastrointestinal worm infection prevalence might increase this contribution by 0.52% relative to baseline levels, resulting in an increase of up to 52% in a universally infected global livestock population. (C) The total impact of pathogen infection on livestock methane production arises from a combination of effects on processes such as lamb production, methane yield, and time to slaughter. Data in (A) are global estimates of methane emissions from 1961 to 2012 due to combined enteric fermentation of cattle, sheep, and goats (http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/GE). Estimates of methane emissions from wetlands, rice cultivation, termites, and oceans are from bottom-up inventories and atmospheric circulation modeling [15]. For (B), we estimated the net effect of increasing worm infection on enteric methane emissions from sheep as the observed effect of infection on methane yield (+33% [5]) times the effect on time to slaughter (+14% [5]). This resulted in an estimated 52% increase (1.33 × 1.14 = 1.52) in methane release. Next, to illustrate how such an effect could scale up to affect livestock-derived methane emissions globally, we recalculated global livestock methane emissions from 2011 across the full range (0–1) of possible infection prevalence, p, using the equation: Emissions(p) = Emissions2011(1.52 * p + (1 − p)).

Disease effects on methane are not unique to worms and sheep. Mastitis, a bacterial infection of the mammary glands, is widespread in dairy cattle and also linked to elevated methane emissions [8,9]. For example, subclinical mastitis, a form of the disease in which no visible signs of infection may be apparent in the udders, reduces both milk yield and feed intake in cows, requiring farmers to cull and replace animals at a higher rate to maximize profit. A recent model showed that subclinical mastitis can increase both enteric and manure methane emissions by up to 8% per kg of milk relative to uninfected cows [8]. Thus, improved control of mastitis in dairy cattle, where an average cow produces ~10 000 kg of milk per year, could tangibly reduce methane emissions from the dairy industry. However, mastitis is primarily controlled using antibiotics and increasing rates of antibiotic resistance under warmer temperatures have been reported for at least two mastitis-causing bacteria: Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli [10], highlighting the complex and reciprocal effects of climate on disease and disease on climate.

Lessons from the Past and Implications for the Future

Infectious diseases have affected global methane production in the past via impacts on herbivorous mammals. For example, the extirpation of megaherbivores at various times in history accounted for reductions in global methane release to the atmosphere of between 0.8% and 34.8% [11]. One of these critical periods was during the African rinderpest outbreak of the 1890s. Rinderpest, caused by a virus similar to measles, was a devastating disease of domestic and wild herbivores prior to its eradication in 2011. In the 1890s, 80–90% of all cattle and wild ruminants in sub-Saharan Africa succumbed to rinderpest and this outbreak was associated with a ~4% reduction in total global methane emissions [11].

If historical losses of herbivores due to infectious disease reduced methane emissions, then changes in methane emissions driven by effects of disease on current herbivore populations seem equally likely. However, the rinderpest example raises the possibility that, in addition to increasing methane emissions from livestock, contemporary infectious diseases might simultaneously decrease emissions by causing widespread mortality. Indeed, mass livestock mortalities due to infectious diseases are common. These events are frequently the result of disease-associated control efforts rather than disease-induced mortality per se and they appear to be increasing in frequency and scope. For example, in the early 2000s, an outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease triggered the slaughter of over 6 million cattle and sheep in the UK (https://www.nao.org.uk/report/the-2001-outbreak-of-foot-and-mouth-disease/). Thus, it is possible that disease-associated mortality could mitigate any disease-related increases in livestock methane emissions.

However, if more livestock are produced to compensate for disease-associated losses, a moderating effect of disease mortality on livestock methane emissions seems unlikely. At a global scale, livestock production often increases in response to regional disease outbreaks to meet sustained market demand [12]. For example, the World Bank estimates that between 2006 and 2009, ~1.4% of the total global population of non-poultry livestock was lost annually due to disease (https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/27118). Despite this annual loss, global stocks of these same species grew from 411 million animals in 1990 to 459 million animals in 2010, a 2.4% annual increase (http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QA), suggesting that increased livestock production outpaced disease-associated mass mortalities occurring over the same timeframe. Thus, under current market conditions, there is no evidence that large-scale disease-associated mortality will help reduce livestock methane emissions.

Accounting for Disease in Mitigation Strategies

In light of growing global demand for livestock products, the potential impact of infectious diseases on animal methane emissions warrants serious attention from researchers and policy makers. First, quantifying the positive, negative, and net effects of pathogens on methane emissions will be crucial for predicting how both endemic and newly emerging livestock diseases might contribute to future changes in global climate. For example, emission projections may drastically underestimate future atmospheric methane concentrations by not accounting for infectious diseases. Given an annual increase in the rate of production of agricultural animals of 2.7%, methane emissions from livestock are projected to rise by +20% between 2017 and 2050 (http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/GE). However, by incorporating GI worm infections alone into these projections (assuming a +52% increase per animal due to a combination of increased methane yield and longer time to slaughter as in Figure 2B), we estimate that livestock emissions over the same period could actually rise by as much as 82% (1.20 × 1.52 = 1.82).

Second, plans for mitigating livestock methane emissions should consider infectious diseases alongside the direct effects of livestock on emissions. Current strategies to mitigate livestock methane emissions include minimizing enteric fermentation by providing livestock with higher quality feed, improving livestock waste management techniques, and selecting for low-emission breeds [13]. For example, microbiome-focused breeding programs are one promising avenue for reducing methane emissions in dairy cattle [14]. Modeling exercises suggest that these strategies can be cost-effective ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (http://sciencesearch.defra.gov.uk/Default.aspx?Menu=Menu&Module=More&Location=None&Completed=0&ProjectID=17791), but it is unclear how these strategies interact with infectious disease. For example, how does selecting for low methane-emission animals affect susceptibility to pathogens? What is the net effect of breeding for low emissions versus breeding for pathogen resistance on methane yield? Addressing these questions is urgent given rising levels of drug resistance among livestock pathogens. As drug efficacy wanes, higher rates of infection could exacerbate methane emissions, so accounting for this dual threat is essential to managing methane emissions effectively.

Finally, if climate change increases some infectious diseases and pathogens, in turn, increase climate change (Figure 1), this positive feedback should be incorporated into models that evaluate both the effects of climate on pathogen transmission and the effects of livestock pathogens on global methane production. More generally, we need a better understanding of the role infectious diseases play in ecosystems beyond direct impacts on host health and the global food supply so we can determine when and how best to incorporate pathogens into climate models and mitigation policies.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Living Earth Collaborative at Washington University in St. Louis for funding the ‘Parasites and Ecosystems’ working group and members of the Ezenwa Laboratory for feedback on the manuscript. Madison Mack and Anne Robinson illustrated Figure 1 in association with InPrint.

References

- 1.Altizer S. Climate change and infectious diseases: from evidence to a predictive framework. Science. 2013;341:514–519. doi: 10.1126/science.1239401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fletcher S.E.M., Schaefer H. Rising methane: a new climate challenge. Science. 2019;364:932–933. doi: 10.1126/science.aax1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bar-On Y.M. The biomass distribution on Earth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018;115:6506–6511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1711842115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fox N.J. Ubiquitous parasites drive a 33% increase in methane yield from livestock. Int. J. Parasitol. 2018;48:1017–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kenyon F. Reduction in greenhouse gas emissions associated with worm control in lambs. Agriculture. 2013;3:271–284. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Houdijk J.G.M. Animal health and greenhouse gas intensity: the paradox of periparturient parasitism. Int. J. Parasitol. 2017;47:633–641. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2017.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rose H. GLOWORM-FL: a simulation model of the effects of climate and climate change on the free-living stages of gastro-intestinal nematode parasites of ruminants. Ecol. Model. 2015;297:232–245. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Özkan Gülzari Ş. Impact of subclinical mastitis on greenhouse gas emissions intensity and profitability of dairy cows in Norway. Prev. Vet. Med. 2018;150:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2017.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mostert P.F. Estimating the impact of clinical mastitis in dairy cows on greenhouse gas emissions using a dynamic stochastic simulation model: a case study. Animal. 2019;13:2913–2921. doi: 10.1017/S1751731119001393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacFadden D.R. Antibiotic resistance increases with local temperature. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018;8:510–514. doi: 10.1038/s41558-018-0161-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith F.A. Exploring the influence of ancient and historic megaherbivore extirpations on the global methane budget. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016;113:874–879. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1502547112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morgan N., Prakash A. International livestock markets and the impact of animal disease. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2006;25:517–528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grossi G. Livestock and climate change: impact of livestock on climate and mitigation strategies. Anim. Front. 2018;9:69–76. doi: 10.1093/af/vfy034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wallace R.J. A heritable subset of the core rumen microbiome dictates dairy cow productivity and emissions. Sci. Adv. 2019;5 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aav8391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghosh A. Variations in global methane sources and sinks during 1910–2010. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015;15:2595–2612. [Google Scholar]