Abstract

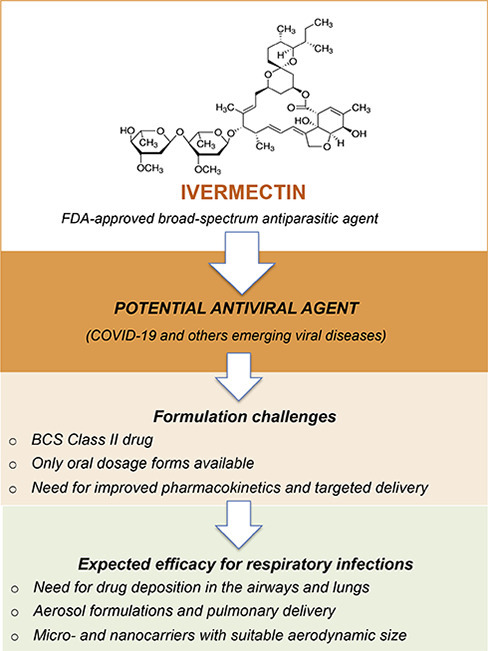

Ivermectin is an FDA-approved broad-spectrum antiparasitic agent with demonstrated antiviral activity against a number of DNA and RNA viruses, including severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Despite this promise, the antiviral activity of ivermectin has not been consistently proven in vivo. While ivermectin's activity against SARS-CoV-2 is currently under investigation in patients, insufficient emphasis has been placed on formulation challenges. Here, we discuss challenges surrounding the use of ivermectin in the context of coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) and how novel formulations employing micro- and nanotechnologies may address these concerns.

Graphical abstract

1. Commentary

The 2015 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine was awarded to William C. Campbell and Satoshi Ömura for their discoveries leading to ivermectin [1]. In addition to its extraordinary efficacy against parasitic diseases, ivermectin continues to offer new clinical applications due to its ability to be repurposed to treat new classes of diseases. Beyond its invaluable therapeutic role in onchocerciasis and strongyloidiasis, an increasing body of evidence points to the potential of ivermectin as an antiviral agent.

Ivermectin treatment was shown to increase survival in mice infected with the pseudorabies virus (PRV) [2] and reduced titers of porcine circovirus 2 (PCV2) in the tissues and sera of infected piglets [3]. In addition, Xu et al. reported the antiviral efficacy of ivermectin in dengue virus-infected Aedes albopictus mosquitoes [4]. Ivermectin was also identified as a promising agent against the alphaviruses chikungunya, Semliki Forest and Sindbis virus, as well as yellow fever, a flavivirus [5]. Moreover, a new study indicated that ivermectin presents strong antiviral activity against the West Nile virus, also a flavivirus, at low (μM) concentrations [6]. This drug has further been demonstrated to exert antiviral activity against Zika virus (ZIKV) in in vitro screening assays [7], but failed to offer protection in ZIKV-infected mice [8].

Recently, Caly et al. reported on the antiviral activity of ivermectin against SARS-CoV-2, the causative agent of COVID-19 [9]. These authors demonstrated that a single dose of ivermectin was able to reduce the replication of an Australian isolate of SARS-CoV-2 in Vero/hSLAM cells by 5000-fold. This finding has generated great interest and excitement among physicians, researchers and public health authorities around the world. However, these results should be interpreted with caution. Firstly, it is important to note that the drug was only tested in vitro using a single line of monkey kidney cells engineered to express human signaling lymphocytic activation molecule (SLAM), also known as CDw150, which is a receptor for the measles virus [10]. Also, ivermectin has not been tested in any pulmonary cell lines, which are critical for SARS-CoV-2 in humans [11]. Furthermore, these authors did not show whether the reduction seen in RNA levels of SARS-CoV-2 following treatment with ivermectin would indeed lead to decreased infectious virus titers. Importantly, the drug concentration used in the study (5 μM) to block SARS-CoV-2 was 35-fold higher than the one approved by the FDA for treatment of parasitic diseases, which raises concerns about its efficacy in humans using the FDA approved dose in clinical trials [12].

In light of the potential of ivermectin to prevent replication in a broad spectrum of viruses, the inhibition of importin α/β1-mediated nuclear import of viral proteins is suggested as the probable mechanism underlying its antiviral activity [6]. Since SARS-CoV-2 is an RNA virus, a similar mechanism of action may take place [9]. A possible ionophore role for ivermectin has also been reported [13]. Since ionophore molecules have been described as potential antiviral drugs [14], ivermectin could ultimately induce an ionic imbalance that disrupts the potential of the viral membrane, thereby threatening its integrity and functionality.

The pathology of COVID-19 is characterized by the rapid replication of SARS-CoV-2, triggering an amplified immune response that may lead to cytokine storm, which frequently induces a severe inflammatory pulmonary response [15]. Disease progression may result in progressive respiratory failure arising from alveolar damage, and can lead to death [16]. Moreover, the monitoring of SARS-CoV-2 viral load in the upper respiratory tract and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) in patients with severe disease indicates higher loads, as well as greater viral persistence [[16], [17], [18], [19]].

In addition to the indication for antiviral therapy, anti-inflammatory intervention may also be necessary to prevent acute lung injury in SARS-CoV-2 infection. With regard to its anti-inflammatory properties, ivermectin have been shown to mitigate skin inflammation [20]. Importantly, ivermectin significantly diminished the recruitment of immune cells and cytokine production in BALF assessed in a murine model of asthma [21]. A study evaluating the ability of ivermectin to inhibit lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammation revealed significantly decreased production of TNF-alpha, IL-1ss and IL-6 in vivo and in vitro [22]. Further studies may establish the role of ivermectin on inflammatory response caused by SARS-CoV-2, whether besides the antiviral activity ivermectin could play a supportive adjuvant role facing the hostile infection microenvironment.

With regard to investigations into potential drug treatments against COVID-19, ivermectin has received particular attention. Indeed, a number of clinical studies have been conducted in various countries such as USA, India and Egypt, as registered on the repository of data ClinicalTrials.gov. Table 1 shows a compilation of these studies, with patients receiving monotherapy or combination therapy, using different approaches of ivermectin dosing. In Spain, the SAINT clinical trial is currently underway and aims to determine the efficacy of a single dose of ivermectin, administered to low risk, non-severe COVID-19 patients [23]. Despite the fact that ivermectin has been shown to be effective in vitro against Sars-Cov-2, it is possible that the necessary inhibitory concentration may only be achieved via high dosage regimes in humans. The enthusiasm surrounding ivermectin use is restrained by a lack of appropriate formulations capable of providing improved pharmacokinetics and drug delivery targeting mechanisms. Although patients could be treated using systemic therapy, high-dose antiviral therapy could lead to severe adverse effects. Regardless, no commercially available injectable forms of ivermectin are available for human use. In COVID-19 patients, the rapid evolution of disease requires prompt treatment, as therapeutic intervention must be introduced within a narrow window of time. Considering that the respiratory tract has been shown to be a primary site of infection, the delivery of ivermectin by pulmonary route would provide high drug deposition in the airways and lungs to mitigate the high viral loads seen in these sites. It is worth noting that inhalation therapy has been reported to be the most effective treatment for respiratory infections due to increased drug bioavailability [24,25]. Indeed, pulmonary and nasal administration bypasses the first-pass metabolism observed in oral administration and the lungs and nasal cavity are known to be low drug-metabolizing environments [26]. In severe cases of SARS-CoV-2-induced pneumonia, antiviral aerosol formulations could be delivered by inhalation to patients on mechanical ventilation. In addition, patients presenting mild symptoms of COVID-19 could benefit from being treated with antiviral aerosol formulations at earlier stages of disease. Importantly, Gilead Sciences recently announced human trials of an inhaled version of its antiviral drug remdesivir for non-hospitalized patients [27].

Table 1.

Ongoing clinical trials evaluating potential treatments for COVID-19 using ivermectin with patients receiving either monotherapy or drug combinations. Studies in very early stages (“not yet recruiting”) or with missing information have not been included.

| Intervention/treatment | Study design | Phase | Enrollment | Status | Sponsor/location | Identifiera |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ivermectin, days 1–2: 12 mg total daily dose (weight < 75 kg); days 1–2: 15 mg total daily dose (weight > 75 kg:) | Single-center, randomized, parallel assignment, open label | II | 240 | Recruiting | University of Kentucky, Markey Cancer Center, United States | NCT04374019 |

| Ivermectin,3 mg capsules, 12–15 mg/day for 3 days | Single-center, randomized, parallel assignment, double-blind, placebo-controlled | NA | 100 | Recruiting | Sheba Medical Center, Israel | NCT04429711 |

| Ivermectin,200 to 400 μg per kg body weight | Single-center, non-randomized, crossover assignment, open-label | NA | 50 | Recruiting | Max Healthcare Insititute Limited, India | NCT04373824 |

| Ivermectin,6 mg and doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 5 days | Single-center, randomized, parallel assignment, double-blind, placebo-controlled | III | 400 | Completed | Dhaka Medical College, Bangladesh | NCT04523831 |

| Ivermectin,200 μg/kg single dose and 200 mg doxycycline day-1 followed by 100 mg doxycycline 12 hourly for 4 days | Single-center, randomized, parallel assignment, double-blind, placebo-controlled | II | 72 | Enrolling by invitation | International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh | NCT04407130 |

| Ivermectin,sub-cutaneous injection 200 μg/kg body weight once every 48 hourly with 80 mg/kg/day Nigella sativa;Sub-cutaneous injection ivermectin 200 μg/kg body weight once every 48 hourly with 20 mg zinc sulphate 8 hourly | Single-center, randomized, parallel assignment, open-label, placebo-controlled | I, II | 40 | Recruiting | Sohaib Ashraf, Sheikh Zayed Federal Postgraduate Medical Institute, Pakistan | NCT04472585 |

| Ivermectin,12 mg weekly + hydroxychloroquine 400 mg/daily + azithromycin 500 mg daily | Single-center, randomized, parallel assignment, | I | 100 | Completed | University of Baghdad, Iraq | NCT04343092 |

| Ivermectin,two doses 72 h apart: 40–60 kg (15 mg/day) 60–80 kg (18 mg/day) >80 kg (24 mg/day) | Single-center, randomized, sequential assignment, open label | II, III | 340 | Completed | Zagazig University, Egypt | NCT04422561 |

| Ivermectin,single dose tablets at 400 μg/kg | Single-center, randomized, parallel assignment, double-blind, placebo-controlled | II | 24 | Recruiting | Clinica Universidad de Navarra, Universidad de Navarra, Spain | NCT04390022 |

| Ivermectin,single oral dose 600 μg/kg or 1200 μg/kg, for 5 days | Multi-center, randomized, sequential assignment, double-blind, placebo-controlled | II | 102 | Recruiting | IRCCS Sacro Cuore Don Calabria di Negrar, Italy | NCT04438850 |

| Ivermectin,at the time of inclusion and the same dose at 24 h, depending on the body weight, from 12 mg to 24 mg in tablets | Single-center, randomized, parallel assignment, double-blind, placebo-controlled | II, III | 500 | Recruiting | Instituto de Cardiología de Corrientes, Argentina | NCT04529525 |

| Ivermectin,600 μg/kg/once daily | Multi-center, randomized, parallel assignment, open label | II | 45 | Recruiting | Laboratorio Elea Phoenix S.A., Argentina | NCT04381884 |

| Ivermectin,300 μg/kg, once daily for 5 days | Single-center, randomized, parallel assignment, double-blind, placebo-controlled | II, III | 400 | Recruiting | Centro de Estudios en Infectogía Pediatrica, Colombia | NCT04405843 |

| Ivermectin,6 mg once daily in day 0,1,7 and 8 plus azithromycin 500 mg once daily for 4 days, plus cholecalciferol, 400 IU twice daily for 30 days) | Single-center, non-randomized, parallel assignment, open-label | NA | 30 | Recruiting | Instituto de Seguridad y Servicios Sociales de los Trabajadores del Estado, Mexico | NCT04399746 |

| Ivermectin,12 mg every 24 h for one day (weight < 80 kg) or 18 mg every 24 h for one day (weight > 80 kg) | Single-center, randomized, parallel assignment, placebo-controlled | III | 108 | Active, not recruiting | Centenario Hospital Miguel Hidalgo, Mexico | NCT04391127 |

| Ivermectin,12 mg followed by losartan 50 mg orally once daily for 15 consecutive days | Single-center, randomized, parallel assignment, double-blind, placebo-controlled | II | 176 | Recruiting | Instituto do Cancer do Estado de São Paulo, Brazil | NCT04447235 |

| Ivermectin, oral dosage based on body weight, once on day for 2 days. This dose schedule should be repeated every 14 days for 45 days associated with 20 mg twice on day of active zinc | Single-center, randomized, parallel assignment, open-label, placebo-controlled | NA | 400 | Recruiting | Núcleo de Pesquisa eDesenvolvimento de Medicamentos (NPDM), Universidade Federal do Ceará, Brazil | NCT04384458 |

| Ivermectin, oral dosing schedules: 100 μg/kg single dose; 100 μg/kg on the first day, followed by 100 μg/kg after 72 h; 200 μg/kg single dose; and 200 μg/kg on the first day, followed by 200 μg/kg after | Single-center, randomized, parallel assignment, open-label | II | 64 | Recruiting | Hospital Univeristário da Universidade Federal de São Carlos, Brazil | NCT04431466 |

https://www.clinicaltrials.gov; NA: not applicable.

Despite its promising antiviral and preliminary anti-inflammatory potential, the development of ivermectin formulations presents challenges, primarily due to its property of poor water solubility. Consequently, ivermectin's oral bioavailability remains low [28]. In addition, its pharmacokinetic profile may be affected by specific formulations, and minor differences in formulation design can modify plasma kinetics, biodistribution, and, consequentially, efficacy. For instance, ivermectin does not achieve adequate concentration levels in the human bloodstream necessary for treatment efficacy against ZIKV [29]. Therefore, novel delivery strategies are needed to optimize ivermectin bioavailability. Micro-and nanocarriers offer several advantages in drug delivery, namely: specific targeting, high metabolic stability, high membrane permeability, improved bioavailability, controlled release and long-lasting action [30]. In light of these attributes, some studies have formulated ivermectin in micro- and nanoparticles, either using lipid nanocapsules [31], chitosan-alginate nanoparticles [32] or poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) micro- and nanoparticles [33,34]. For antiviral purposes, ivermectin has been formulated in liposomes [35] and PLGA nanoparticles [29]. The latter ivermectin nanoformulation was shown to cross the intestinal epithelial barrier when administered via oral route, with considerable concentrations detected in the blood, enabling its potential application in ZIKV therapy.

Appropriate drug formulations must address inherent limitations, including poor water-solubility and difficulty in drug delivering to desired target areas, notably the pulmonary environment. As previously mentioned, micro-and nanocarriers have been investigated in an effort to optimize ivermectin bioavailability. In the context of pulmonary delivery, these drug delivery systems can be modified to attend suitable aerodynamic size ranges for the airways and alveolar deposition. Smaller particles achieve a greater deposition in the lungs compared to larger particles. Particles smaller than 5 μm follow the airflow beyond the retro-pharynx and reach the trachea. Particles with an aerodynamic diameter of about 2 to 5 μm are deposited in the upper respiratory tract at the level of the trachea and tracheal bifurcation. Particles smaller than 2 μm deposit in the lower airway and alveolar epithelia [36,37]. Nanoparticulate systems, upon release in aerosol, form aggregates in the micrometer size range. These aggregates are believed to have sufficient mass to be deposited in the bronchiolar region and remain for an extended period, hence achieving the desired effect [38]. It follows that ivermectin formulations produced at the desired particle sizes will allow for particle deposition in either the lower airway or alveolar epithelia, which will then trigger rapid drug release, accelerating the onset of therapeutic activity.

We hypothesize that micro- and nanotechnology-based systems for the pulmonary delivery of ivermectin may offer opportunities for accelerating the clinical re-purposing of this “enigmatic drug” in the context of SARS-CoV-2 infection, as recent advances in pharmaceutical technology and nanomaterials can be applied to the treatment of pulmonary infections [[24], [25], [26],[36], [37], [38], [39], [40]]. Despite the challenges faced in developing these drug delivery carriers, and uncertainty with regard to the efficacy of ivermectin, it indeed presents promising potential. In an optimistic scenario, new drug dosage forms may not only contribute to mitigate SARS-CoV-2 infection, but also be effective against other emerging viral diseases.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors deny the existence of any conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank FACEPE (Pernambuco, Brazil), CNPq (Brazil), Inova Fiocruz (Brazil) and IDRC (Canada) for financial support. The authors also acknowledge the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES) – Finance Code 001. The authors are grateful to Andris K. Walter for critical manuscript review and English language copyediting services.

References

- 1.Callaway E., Cyranoski D. Anti-parasite drugs sweep Nobel prize in medicine 2015. Nature. 2015;526:174–175. doi: 10.1038/nature.2015.18507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lv C., Liu W., Wang B., Dang R., Qiu L., Ren J., Yan C., Yang Z., Wang X. Ivermectin inhibits DNA polymerase UL42 of pseudorabies virus entrance into the nucleus and proliferation of the virus in vitro and vivo. Antivir. Res. 2018;159:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2018.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang X., Lv C., Ji X., Wang B., Qiu L., Yang Z. Ivermectin treatment inhibits the replication of porcine circovirus 2 (PCV2) in vitro and mitigates the impact of viral infection in piglets. Virus Res. 2019;263:80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2019.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu T.L., Han Y., Liu W., Pang X.Y., Zheng B., Zhang Y., Zhou X.N. Antivirus effectiveness of ivermectin on dengue virus type 2 in Aedes albopictus. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2018;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varghese F.S., Kaukinen P., Glasker S., Bespalov M., Hanski L., Wennerberg K., Kummerer B.M., Ahola T. Discovery of berberine, abamectin and ivermectin as antivirals against chikungunya and other alphaviruses. Antivir. Res. 2016;126:117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang S.N.Y., Atkinson S.C., Wang C., Lee A., Bogoyevitch M.A., Borg N.A., Jans D.A. The broad spectrum antiviral ivermectin targets the host nuclear transport importin alpha/beta1 heterodimer. Antivir. Res. 2020;177:104760. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barrows N.J., Campos R.K., Powell S.T., Prasanth K.R., Schott-Lerner G., Soto-Acosta R., Galarza-Muñoz G., McGrath E.L., Urrabaz-Garza R., Gao J., Wu P., Menon R., Saade G., Fernandez-Salas I., Rossi S.L., Vasilakis N., Routh A., Bradrick S.S., Garcia-Blanco M.A. A screen of FDA-approved drugs for inhibitors of Zika virus infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;20:259–270. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ketkar H., Yang L., Wormser G.P., Wang P. Lack of efficacy of ivermectin for prevention of a lethal Zika virus infection in a murine system. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019;95:38–40. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2019.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caly L., Druce J.D., Catton M.G., Jans D.A., Wagstaff K.M. The FDA-approved drug Ivermectin inhibits the replication of SARS-CoV-2 in vitro. Antivir. Res. 2020;178:104787. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ono N., Tatsuo H., Hidaka Y., Aoki T., Minagawa H., Yanagi Y. Measles viruses on throat swabs from measles patients use signaling lymphocytic activation molecule (CDw150) but not CD46 as a cellular receptor. J. Virol. 2001;75:4399–4401. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.9.4399-4401.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang H., Zhou P., Wei Y., Yue H., Wang Y., Hu M., Zhang S., Cao T., Yang C., Li M., Guo G., Chen X., Chen Y., Lei M., Liu H., Zhao J., Peng P., Wang C.Y., Du R. Histopathologic changes and SARS-CoV-2 imunostaining in the lung of a patient with COVID-19. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020:M20–0533. doi: 10.7326/M20-0533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmith D., Zhou J.J., Lohmer L.R.L. The approved dose of ivermectin alone is not the Ideal dose for the treatment of COVID-19. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020;108:762–765. doi: 10.1002/cpt.1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rizzo E. Ivermectin, antiviral properties and COVID-19: a possible new mechanism of action. Naunyn Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2020;393:1153–1156. doi: 10.1007/s00210-020-01902-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sandler Z.J., Firpo M.R., Omoba O.S., Vu M.N., Menachery V.D., Mounce B.C. Novel ionophores active against La Crosse virus identified through rapid antiviral screening. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020;64 doi: 10.1128/AAC.00086-20. e00086–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pedersen S.F., Ho Y.C. SARS-CoV-2: a storm is raging. J. Clin. Invest. 2020;130:2202–2205. doi: 10.1172/JCI137647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou P., Yang X., Wang X., et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wölfel R., Corman M., Guggemos W., et al. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature. 2020;581:465–469. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zou L., Ruan F., Huang M., Liang L., Huang H., Hong Z., Yu J., Kang M., Song Y., Xia J., Guo Q., Song T., He J., Yen H.L., Peiris M., Wu J. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1177–1179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng S., Fan J., Yu F., Feng B., Lou B., Zou Q., Xie G., Lin S., Wang R., Yang X., Chen W., Wang Q., Zhang D., Liu Y., Gong R., Ma Z., Lu S., Xiao Y., Gu Y., Zhang J., Yao H., Xu K., Lu X., Wei G., Zhou J., Fang Q., Cai H., Qiu Y., Sheng J., Chen Y., Liang T. Viral load dynamics and disease severity in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Zhejiang Province, China, January-march 2020: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1443. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ebbelaar C.C.F., Venema A.W., Van Dijk M.R. Topical ivermectin in the treatment of Papulopustular rosacea: a systematic review of evidence and clinical guideline recommendations. Dermatol. Ther. (Heidelb). 2018;8:379–387. doi: 10.1007/s13555-018-0249-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yan S., Ci X., Chen N., Chen C., Li X., Chu X., Li J., Deng X. Anti-inflammatory effects of ivermectin in mouse model of allergic asthma. Inflamm. Res. 2011;60:589–596. doi: 10.1007/s00011-011-0307-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang X., Song Y., Ci X., An N., Ju Y., Li H., Wang X., Han C., Cui J., Deng X. Ivermectin inhibits LPS-induced production of inflammatory cytokines and improves LPS-induced survival in mice. Inflamm. Res. 2008;57:524–529. doi: 10.1007/s00011-008-8007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chaccour C., Ruiz-Castillo P., Richardson M.A., Moncunill G., Casellas A., Carmona-Torre F., Giráldez M., Mota J.S., Yuste J.R., Azanza J.R., Fernández M., Reina G., Dobaño C., Brew J., Sadaba B., Hammann F., Rabinovich R. The SARS-CoV-2 Ivermectin Navarra-ISGlobal trial (SAINT) to evaluate the potential of ivermectin to reduce COVID-19 transmission in low risk, non-severe COVID-19 patients in the first 48 hours after symptoms onset: a structured summary of a study protocol for a randomized control pilot trial. Trials. 2020;21:498. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-04421-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho D.K., Nichols B.L.B., Edgar K.J., Murgia X., Loretz B., Lehr C.M. Challenges and strategies in drug delivery systems for treatment of pulmonary infections. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2019;144:110–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2019.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou Q.T., Leung S.S., Tang P., Parumasivam T., Loh Z.H., Chan H.K. Inhaled formulations and pulmonary drug delivery systems for respiratory infections. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2015;85:83–99. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2014.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghadiri M., Young P.M., Traini D. Strategies to enhance drug absorption via nasal and pulmonary routes. Pharmaceutics. 2019;11:113. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics11030113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.An Open Letter from Daniel O'Day, Chairman & CEO, Gilead Sciences. 2020. https://stories.gilead.com//articles/an-open-letter-from-daniel-oday-june-22

- 28.Takano R., Sugano K., Higashida A., Hayashi Y., Machida M., Aso Y., Yamashita S. Oral absorption of poorly water-soluble drugs: computer simulation of fraction absorbed in humans from a miniscale dissolution test. Pharm. Res. 2006;23:1144–1156. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-0162-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Surnar B., Kamran M.Z., Shah A.S., Basu U., Kolishetti N., Deo S., Jayaweera D.T., Daunert S., Dhar S. Orally administrable therapeutic synthetic nanoparticle for Zika virus. ACS Nano. 2019;13:11034–11048. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b02807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Onoue S., Yamada S., Chan H.K. Nanodrugs: pharmacokinetics and safety. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2014;9:1025–1037. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S38378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ullio-Gamboa G., Palma S., Benoit J.P., Allemandi D., Picollo M.I., Toloza A.C. Ivermectin lipid-based nanocarriers as novel formulations against head lice. Parasitol. Res. 2017;116:2111–2117. doi: 10.1007/s00436-017-5510-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ali M., Afzal M., Verma M., Misra-Bhattacharya S., Ahmad F.J., Dinda A.K. Improved antifilarial activity of ivermectin in chitosan-alginate nanoparticles against human lymphatic filarial parasite, Brugia malayi. Parasitol. Res. 2013;112:2933–2943. doi: 10.1007/s00436-013-3466-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ali M., Afzal M., Verma M., Bhattacharya S.M., Ahmad F.J., Samim M., Abidin M.Z., Dinda A.K. Therapeutic efficacy of poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles encapsulated ivermectin (nano-ivermectin) against brugian filariasis in experimental rodent model. Parasitol. Res. 2014;113:681–691. doi: 10.1007/s00436-013-3696-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Camargo J.A., Sapin A., Daloz D., Maincent P. Ivermectin-loaded microparticles for parenteral sustained release: in vitro characterization and effect of some formulation variables. J. Microencapsul. 2010;27:609–617. doi: 10.3109/02652048.2010.501397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Croci R., Bottaro E., Chan K.W., Watanabe S., Pezzullo M., Mastrangelo E., Nastruzzi C. Liposomal systems as nanocarriers for the antiviral agent Ivermectin. Int. J. Biomater. 2016;8043983 doi: 10.1155/2016/8043983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu Q., Guan J., Qin L., Zhang X., Mao S. Physicochemical properties affecting the fate of nanoparticles in pulmonary drug delivery. Drug Discov. Today. 2020;25:150–159. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2019.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Newman S.P. Drug delivery to the lungs: challenges and opportunities. Ther. Deliv. 2017;8:647–661. doi: 10.4155/tde-2017-0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paranjpe M., Müller-Goymann C.C. Nanoparticle-mediated pulmonary drug delivery: a review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014;15:5852–5873. doi: 10.3390/ijms15045852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cojocaru F.D., Botezat D., Gardikiotis I., Uritu C.M., Dodi G., Trandafir L., Rezus C., Rezus E., Tamba B.I., Mihai C.T. Nanomaterials designed for antiviral drug delivery transport across biological barriers. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12:171. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12020171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chan W.C.W. Nano research for COVID-19. ACS Nano. 2020;14:3719–3720. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c02540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]