Abstract

“Stay home, save lives” has been shown to reduce the impacts of COVID-19; however, it is crucial to recognize that efforts not to stress healthcare systems may have unintended social consequences for domestic violence. This commentary addresses domestic violence as an important social and public health implication of COVID-19. As a pandemic with a high contagion level, necessary social distancing measures have been put in place across the world to slow transmission and protect medical services. We first present literature that shows that among the effects of social distancing are social and functional isolation and economic stress, which are known to increase domestic violence. We then present preliminary observations from a content analysis conducted on over 300 news articles from the first six weeks of COVID-19 “lockdown” in the United States: articles predict an increase in domestic violence, report an increase in domestic violence, and inform victims on how to access services. Assessing the intersection of the early news media messaging on the effect of COVID-19 on DV and the literature on social isolation and crisis situations, we conclude the commentary with implications for current policy related to (1) increased media attention, (2) increased attention in healthcare systems, (3) promoting social and economic security, and (4) long-term efforts to fund prevention and response, as well as research implications to consider. The research is presented as ongoing, but the policy and procedure recommendations are presented with urgency.

Keywords: COVID-19, Intimate partner violence, Domestic violence, Social isolation, Coronavirus

1. Introduction

In, 2020, the novel coronavirus commonly referred to as COVID-19 spread rapidly around the globe, resulting in unprecedented physical, mental, social, and economic impacts. One social and public health implication of COVID-19 is seen in the impacts on domestic violence (DV), defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as “physical violence, sexual violence, stalking, or psychological harm by a current or former partner or spouse” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). As a pandemic with a high contagion level, necessary social distancing measures have been put in place across the world to slow transmission and protect medical services. While necessary for preventing the spread of the disease, it is essential to consider the unintended impacts of such policies on DV. As highlighted herein, crisis situations, especially those involving social isolation, only exacerbate the conditions that are known to be risk factors for DV.

Early reports have documented alarming rates of increase in DV around the world; reports range from a 20%–25% increase in calls to helplines in Spain, Cyprus and the UK to a 40% or 50% increase in calls in Brazil (Bradbury-Jones & Isham, 2020). Peterman et al. (2020) document similar increases in Australia, Brazil, China, and the United States. As the US is seeing a rise in DV (Boserup, McKenney, & Elkbuli, 2020), the systems that are in place to prevent DV and to respond to DV are working under unprecedented restraints to respond to or reduce these rates.

Pre-pandemic data from the United States reveal that domestic violence affects about one in five women and about one in seven men, resulting is devastating personal trauma and injury (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). This commentary addresses increased rates DV as an important social and public health consequence of COVID-19. This implication is brought on by a break-down of existing social structures. We present literature that shows among these are social and functional isolation and economic stress. We then present preliminary findings from a content analysis conducted on over 300 news articles from the first six weeks of COVID-19 “lockdown” in the United States. We conclude the commentary with implications for future research and current policy. The research is presented as ongoing, but the policy and procedure recommendations are presented with urgency. “Stay home, save lives” has been shown to reduce the impacts of COVID-19; however, it is crucial to recognize that efforts not to stress healthcare systems may have unintended social consequences for DV.

1.1. Social isolation increases risk of DV

Stay at home orders limit familiar support options, increasing social and functional isolation. There is ample evidence that social isolation increases the risk of victimization. Social isolation is defined as having a lack of social connections needed for resources—in this sense, it is the isolation from support systems. Socially isolated individuals are at higher risk for all forms of DV (Lanier & Maume, 2009; Capaldi, Knoble, Shortt, & Kim, 2012; Farris & Fenaughty, 2002). Much of the research in this area focuses on rural communities, finding that the more rural or isolated a community as a whole, the higher prevalence of DV (Peek-Asa et al., 2011). Moreover, social isolation increases the opportunity for coercive control (Raghavan, Beck, Menke, & Loveland, 2019), which Myhill and Hohl (2019) find to be the strongest predictor of domestic violence. The combination of isolation and intimidation leads to the most violent and consistent abuse and is more likely to be lethal (Myhill & Hohl, 2019). In a study by Farris and Fenaughty (2002), male perpetrators were more likely to tell women they did not need to have friends, male or female, did not need to work, and to always stay home. Forced isolation, as well as behavior monitoring, not only removes social support structures but adds stress to the victim and gives control to the perpetrator (Mitchell & Raghavan, 2019). These efforts separate victims from these social support structures that may be able to help them out of the situation (Stylianou, Counselman-Carpenter, & Redcay, 2018).

While social isolation occurs when one is separated from family and friends, functional isolation occurs when support systems are no longer reliable (van Gelder et al., 2020). For instance, there is a lack of resources and criminal service involvement in rural areas that serve as geodemographic determinants (Lanier & Maume, 2009). Shelters and victim service centers are critical in supporting survivors to leave their abusers but are not a substitute for personal social support (Stylianou et al., 2018). Because of social distancing measures, shelters and other response services (as will be discussed) are not operating in the same manner and, in some cases, are operating over capacity or not at all. This reduces access to DV resources at a time when individuals are already socially isolated, increasing functional isolation. For instance, in many states, victims’ advocates have not been able to go to the hospital to support victims due to COVID-19 restrictions.

1.2. Crisis situations increase risk of DV

In the case of COVID-19, social isolation is even more confounded by stressors. Research from previous pandemics shows that the length of quarantine correlates to the degree of their psychological consequences, such as depression and stress (Brooks et al., 2020). The impacts of these factors on DV is well documented (Peterman et al., 2020).

Among these stressors are the economic impacts. In the first five weeks of the lockdown from the virus, more than 26 million Americans lost their jobs, and a quarter of Americans fear they will lose their jobs in the next year (Zarroli & Schneider, 2020). Millions of others have not lost their job, but have experienced a decrease in their income or are working under extremely stressful conditions as essential workers. Low income and unemployment are known risk factors for DV (Capaldi et al., 2012; Moore, 2020). More specifically, male unemployment significantly correlates with DV rates (Lanier & Maume, 2009). Moreover, loss of health insurance that was provided by one’s employer complicates one’s ability to seek medical help when they become unemployed (Lauve-Moon & Ferreira, 2017). In about one-third of DV cases, economic factors render the victim financially dependent on the abuser (Moore, 2020). On the other hand, financial independence is a known protective factor against DV (Jackson, 2016; Reichel, 2017). Davies et al. (2015) find low economic status to be a predictor of DV, but also that DV perpetuates low economic status.

Social circumstances forced by crises can include loss of housing and social support networks (Gearhart et al., 2018). Low socioeconomic status (SES) communities are already more vulnerable to higher rates of DV (Gillum, 2019). Low SES communities are not only more economically vulnerable, but they have higher rates of substance abuse. This issue is confounded by the stress caused by COVID-19 throughout the world.

Just as the virus increases stress levels and social isolation, social isolation is also a mediator for substance abuse (Farris & Fenaughty, 2002), which is also a risk factor for DV. Myhill and Hohl (2019) found that a majority (53.3%) of domestic violence perpetrators had a substance abuse and/or mental health illness. Dependency on drugs often increases social isolation, leading to greater susceptibility to victimization (Farris & Fenaughty, 2002) and perpetration (Assari & Jeremiah, 2018).

Much of the research on DV during crises focuses on disasters. Both disasters and DV disproportionately impact women and ethnic and racial minorities (Buttell & Carney, 2009; Gearhart et al., 2018; Lauve-Moon & Ferreira, 2017). As aforementioned, just as individuals lose their support systems during disasters, they often lose access to critical resources, such as DV shelters (Enarson, 1999). Enarson (1999) noted an increase in women who were already in abusive situations requiring shelter services in post-disaster recovery periods.

2. Preliminary evidence

With an understanding of the relationship between social isolation, crisis situations, and DV, the purpose of this research is to evaluate the early news media messaging on the effect of COVID-19 on DV. As such, our guiding research question is: How are American news media covering the impacts of COVID-19 on DV? As our dataset, we set Google Alerts (as of March 16, 2020) on appropriate combinations of “COVID-19/COVID19/coronavirus” and “domestic violence.” The researchers then received daily emails with links to all new English-language media sources that include these search terms. We then created an Excel sheet to record relevant articles with columns for a link to articles, the date of the article, the geographic scope (e.g., city, county, state, region, or US broadly), the title of the article, any documentation of the change in DV rates, and primary, secondary, and tertiary point of the article. In this process, we defined relevant articles as those related to the impacts of COVID-19 on DV or changes in DV resources/services related to COVID-19, exclusive of articles about particular individuals contracting or those tested for COVID-19— Our data represent the first six weeks of a pandemic with no particular end and has captured more than 300 relevant news articles from around the US. The preliminary nature of our data collection makes it difficult to know which of our observations will be supported by further research in this area and which are possibly sensationalized by the media. However, in our analysis of these articles, there are some trends that speak to the need for immediate and substantial action. The articles appear to have at least one of three purposes (with many coded into multiple categories): to report on the social conditions resulting from COVID-19 that would predict an increase in DV, to report an increase in reports of DV, and/or to inform victims on how to access services. We use these categories to highlight the following preliminary observations that inform this commentary when considered alongside the extant literature:

2.1. Observation 1. articles predict an increase in DV

The first type of article, accounting for about 64% of those reviewed, we are seeing serves the purpose of predicting that the COVID-19 social distancing measures will affect DV. Although the articles do not often cite the specific literature, many of the observations align with the literature we address within this commentary. Broadly, they point to the social implications (stress, job loss, social support) of social distancing and present arguments that they expect an increase in DV to follow. Some articles provide empirical evidence to support these predictions, such as the observation that some women have reported their partners threatening to contract the novel coronavirus in order to force their wives and children to stay home even longer. As an example from our data, Donnelly (2020) highlighted, “Domestic violence advocates say for victims, social distancing and isolation amid the coronavirus pandemic can put them at even greater risk … Jessica Brayden, who heads the domestic violence prevention agency Respond, Inc. in Somerville, Massachusetts, said she and other advocates fear the pandemic is putting victims in more danger. The message to stay home, coupled with financial stress, job loss, and kids staying home from school, can trap victims and trigger abusers.”

2.2. Observation 2. articles report an increase in DV

Although it will take time to fully assess the impacts of COVID-19 on DV, there is strong evidence from local, domestic, and abroad accounts that the predicted increase we have outlined based on extant literature is occurring. Most increases are measured by calls to victim services hotlines and emergency services. Many of these articles, which accounted for about 44% of articles, seek to explain the numbers by pointing to the social circumstances of COVID-19. For instance, this would include articles that cite the number of calls to the crisis hotline in March 2020 compared to earlier months in the year or compared to March 2019 and then seek to further explain these numbers by looking at the instability in the economy. As an example, Saterfields’s (2020) article on Fairfax, Virginia states, “According to the Fairfax County Police Department’s daily call-for-service recaps, there has been an increase in the number of domestic violence-related calls. Fairfax County Police Chief Edwin Roessler Jr said in a provided statement that the department has seen an incremental uptick in domestic violence calls in the county. The daily average number of domestic related calls this month, according to the daily calls-for-service recaps, are up 26% compared to April 2019.”

2.3. Observation 3. articles inform victims on how to access services

The third general purpose of the articles thus far has been to inform the public on how to access services related to DV. These articles accounted for about 35% of articles. Some of these articles were speculative regarding the change in access to or availability of these services. Some victims are no longer in contact with individuals outside their homes and, as such, less likely to seek help or perceive they have the support to seek help. Additionally, without insurance or income, some may not seek help for financial reasons. Still, others may not seek help for fear of contracting COVID-19 through interaction with others. For instance, healthcare officials are worried that women will not seek assistance in emergency rooms because of the fear of contracting the virus. As an example from our data, Moore’s (2020) article on South Carolina stated, “Emergency rooms are open. Survivors of sexual assault still have a place to go for care. That’s the message from expert nurses ready to treat victims.”

Nevertheless, other articles related specific information on changes in services or procedures. For instance, expanding online services and the number of locations people can turn to for help. DV services are impacted by COVID-19 as well. During social distancing, victims’ advocates are often not allowed in emergency rooms; victims are told to call after they are released. Additionally, because of policies put in place to reduce contagion through hospitals, victims may find that they cannot bring anyone to the hospital with them. Similarly, when reaching out to DV services, victims may be counseled over the phone or virtually where face-to-face interaction would have previously occurred. When the victim lives with the abuser, this mode of interaction is not always safe. Finally, there was a subset of articles in this area that served the purpose of communicating that services would continue as usual or with minimal interruption.

3. Implications

While draconian measures are necessary to impede the spread of COVID-19, the effects of the social distancing measures are deeply worrying. Peek-Asa et al. (2011) attributed higher rates of DV in rural communities to isolation from resources—the social distancing measures related to COVID-19 are increasing DV rates in the US as everyone is now more isolated from resources. Our preliminary findings indicate that DV is increasing, and these services designed to support victims are no longer easily accessible in any community. When considered in the context of extant literature on social isolation and crisis situations, we expect that DV will continue to increase in all communities, but that given this disparity in access to services, that there will still be a more significant impacts in our rural, minority, and low SES communities. In other words, all communities will see a rise in DV, but as the effects of COVID-19 are likely to yield more significant social stress in these communities, some areas will see a more considerable increase than others. When we couple the alarming early news media reports of increased DV, both predicted and reported, and the conditions reported in the literature that create risk environments for DV, we come to preliminary action items for addressing DV in the era of COVID-19.

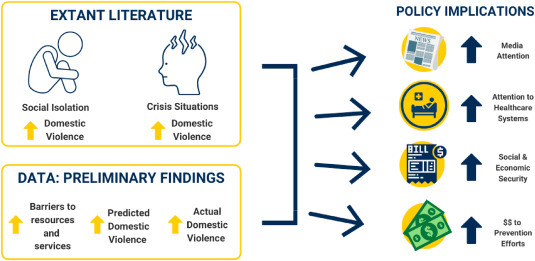

The primary implication is that immediate action is required to recognize and respond to the effect of COVID-19 on DV. Our preliminary findings that DV is predicted to increase and already increasing aligns with the literature that DV increases with social isolation and in crisis situations. This is further compounded by our finding that there is a disruption to COVID-19 services (see Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Development of implication from literature & findings

In this commentary, we outline four immediate needs to address this unintended effect: (1) increased media attention, (2) increased attention in healthcare systems, (3) promoting social and economic security, and (4) long-term efforts to fund prevention and response, as well as research implications to consider. These are recommendations that would apply to DV prior to the novel coronavirus but become even more crucial in our current social circumstances. Further, we acknowledge that our results focus on DV, but also speak to other forms of family violence, including child abuse and elderly abuse. The risk factors we have highlighted herein regarding DV are closely related to those of other forms of violence. Although not the primary focus of our search, we have encountered a considerable amount of evidence that the observations made herein about DV speak broadly to the impacts on violence against women1 and children. Currently, our preliminary analysis reveals that there has been an overall decrease in the number of child abuse cases currently being reported. However, this is likely due to children not having friend’s family members, teachers, and pastors who can catch the signs and report it. Counter to this, researchers expect there to be an increase in child abuse cases once businesses and schools start to reopen.

3.1. Increased media attention

Although we have documented a tremendous media response to the impacts of COVID-19 on DV, we call for continued media support to spread awareness to both the underlying issues increasing DV risk and the services available to victims. Moreover, social distancing measures have halted many primary prevention efforts that inform the public about these issues, so the media fill this void. Finally, while we have assessed only news media, we acknowledge that social media also plays a vital role in increasing media attention to DV. In one article we reviewed, for instance, Selvaratnum (2020) discussed how “#AntiDomesticViolenceDuringEpidemic has been trending on the Chinese social media platform Sina Weibo.” Similarly, American media covered pop-singer Rihanna’s Clara Lionel Foundation’s donation of 2.1 million USD to a Los Angeles domestic violence organization. Given the 24-h news cycle, it is important that such efforts continue to reach large audiences to bring awareness to the issue.

3.2. Increased attention in healthcare and emergency response systems

DV victims need to know their needs are not secondary. There are immediate policy implications for how DV cases are handled. Although service systems for victims are not functioning as they did before COVID-19, it is crucial to communicate that these services are available, that they are offered in the safest possible way to reduce risk of COVID-19, and that they are client-centered. This recommendation includes proper training for all those in contact with DV victims regarding their needs and an urgent need to assess the physical and emotional needs of DV victims. The recommendation also includes sufficient resources and personal protective equipment (PPE) to protect victims of DV, victim advocates, and all others involved, as well as funding to address the current volume of cases.

3.3. Long-term efforts to promote social and economic security

The social isolation required to control COVID-19 is unprecedented, but so are the social and economic consequences. Addressing these other factors will aid in addressing DV. Early efforts to address the economic impacts, such as the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, have sought to provide relief to Americans economically impacted by the coronavirus lockdown. However, the social and economic impacts are already expansive and evident in DV rates. More will be needed to address these underlying risk factors as policies and procedures currently in place.

3.4. Long-term efforts to fund prevention and response

There is precedent for changing priorities in times of economic hardship given a hierarchy of societal needs and limited funding. In response, it may be tempting to cut programs that focus on primary prevention or response to DV in order to reserve funds for other services and programs. We advocate that these responses are reconsidered, given the long-term impacts of COVID-19 on DV.

3.5. Research implications

Although DV services are working fast to adjust to the social implications of COVID-19, there is little evidence available to understand the comparative effectiveness of these changes in services fully. There is a growing and immediate need to understand the impacts of these novel approaches to supporting victims of DV. As the demand for these services is predicted to increase, and there is early evidence that supports this prediction, more research is needed on the effectiveness of online interventions. Tarzia, Cornelio, Forsdike, and Hegarty (2018) highlighted the need to understand better how women perceive services and how online experiences might compare to traditional approaches. Preliminary evidence implies that the effectiveness of virtual services for DV may depend on trust; as such, these services might be more useful for ongoing support than for providing support to new cases (Tarzia et al., 2018). Research must also consider access. As services go online, not everyone will have access either because of economic resources or because of control tactics used by an abuser. Access during social restrictions does not look the same as it may in other social situations.

Additionally, more research is needed on the impacts of COVID-19 on DV and any geographic or demographic differences. We must consider groups, physical and demographic, disproportionately impacted during these times. It is well established, for instance, that risk factors for victimization are not equally distributed across the population racially, economically, or based on gender (Stylianou et al., 2018). Further, while our preliminary findings were based on US news media, research is recommended to consider the impact of COVID-19 on DV on a more global scale.

Finally, although we have outlined preliminary findings from our analysis of media coverage of the articles relating to DV and COVID-19, a further and complete content analysis of the articles, their purpose, their messaging, and their perceived effect is warranted to expand on these preliminary observations. Continued research will require long-term documentation and analysis and will undoubtedly evolve as the social impacts of COVID-19 continues to evolve.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Candace Forbes Bright: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Christopher Burton: Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Madison Kosky: Investigation, Resources, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

We recognize that DV can be between same-sex partners and that males can be victims, but align with the literature that it is a largely gendered phenomenon in which females are most often the victims and males are most often the perpetrators (Fulu, Jewkes, Roselli, & Garcia-Moreno, 2013).

References

- Assari S., Jeremiah R.D. Intimate partner violence may be one mechanism by which male partner socioeconomic status and substance use affect female partner health. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2018;9 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boserup B., McKenney M., Elkbuli A. Alarming trends in US domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2020;S0735–6757(20):30307. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.04.077. 7. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury Jones C., Isham L. The pandemic paradox: The consequences of COVID-19 on domestic violence. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jocn.15296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S.K., Webster R.K., Smith L.E., Woodland L., Wessely S., Greenberg N. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttell F.P., Carney M.M. Examining the impact of Hurricane Katrina on police responses to domestic violence. Traumatology. 2009;15(2):6–9. doi: 10.1177/1534765609334822. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi D.M., Knoble N.B., Shortt J.W., Kim H.K. A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse. 2012;3(2):1–27. doi: 10.1891/1946-6560.3.2.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Government Printing Office; 2017. Preventing intimate partner violence across the lifespan: A technical package of programs, policies, and practices. [Google Scholar]

- Davies L., Ford-Gilboe M., Willson A., Varcoe C., Wuest J., Campbell J. Patterns of cumulative abuse among female survivors of intimate partner violence: Links to women’s health and socioeconomic status. Violence Against Women. 2015;21(1):30–48. doi: 10.1177/1077801214564076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly A. Domestic violence advocates fear ‘perfect storm during Coronavirus pandemic. 2020. https://www.nbcboston.com/investigations/domestic-violence-advocates-fear-perfect-storm-during-pandemic/2100955/ April 3.

- Enarson E. Violence against women in disasters: A study of domestic violence programs in the United States and Canada. Violence Against Women. 1999;5(7):742–768. doi: 10.1177/10778019922181464. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farris C.A., Fenaughty A.M. Social isolation and domestic violence among female drug users. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2002;28(2):339–351. doi: 10.1081/ADA-120002977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulu E., Jewkes R., Roselli T., Garcia-Moreno G. On behalf of the UN multi-country cross-sectional study on men and violence research team Prevalence of and factors associated with male perpetration of intimate partner violence: Findings from the UN multi-country cross-sectional study on men and violence in asia and the pacific. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1:e187–e207. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70074-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gearhart S., Perez-Patron M., Hammond T.A., Goldberg D.W., Klein A., Horney J.A. The impact of natural disasters on domestic violence: An analysis of reports of simple assault in Florida (1999–2007) Violence and Gender. 2018;5(2):87–92. doi: 10.1089/vio.2017.0077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Gelder N., Peterman A., Potts A., O’Donnell M., Thompson K., Shah N. EClinicalMedicine; 2020. COVID-19: Reducing the risk of infection might increase the risk of intimate partner violence. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillum T.L. The intersection of intimate partner violence and poverty in Black communities. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2019;46:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2019.01.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson A.L. The combined effect of women’s neighborhood resources and collective efficacy on IPV. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2016;78(4):890–907. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12294. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lanier C., Maume M.O. Intimate partner violence and social isolation across the rural/urban divide. Violence Against Women. 2009;15(11):1311–1330. doi: 10.1177/1077801209346711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauve-Moon K., Ferreira R.J. An exploratory investigation: Post-disaster predictors of intimate partner violence. Clinical Social Work Journal. 2017;45(2):124–135. doi: 10.1007/s10615-015-0572-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell J.E., Raghavan C. 2019. The impact of coercive control on use of specific sexual coercion tactics. violence against women. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore M. April 2, 2020. Nurses concerned victims of sexual assault won’t come to ER because of coronavirus.https://www.wyff4.com/article/nurses-concerned-victims-of-sexual-assault-wont-come-to-er-because-of-coronavirus/32021483 [Google Scholar]

- Myhill A., Hohl K. The “golden thread”: Coercive control and risk assessment for domestic violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2019;34(21–22):4477–4497. doi: 10.1177/0886260516675464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peek-Asa C., Wallis A., Harland K., Beyer K., Dickey P., Saftlas A. Rural disparity in domestic violence prevalence and access to resources. Journal of Women’s Health. 2011;20(11):1743–1749. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.2891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterman A., Potts A., O’Donnell M., Thompson K., Shah N., Oertelt-Prigione S. Vol. 528. Center Global Dev Work Paper; 2020. (Pandemics and violence against women and children). [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan C., Beck C.J., Menke J.M., Loveland J.E. Coercive controlling behaviors in intimate partner violence in male same-sex relationships: A mixed-methods study. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services. 2019;31(3):370–395. doi: 10.1080/10538720.2019.1616643. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reichel D. Determinants of intimate partner violence in Europe: The role of socioeconomic status, inequality, and partner behavior. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2017;32(12):1853–1873. doi: 10.1177/0886260517698951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satterfield K. Abusers threatening to ‘purposely contract’ COVID-19 reported among rise in domestic violence calls, Fairfax Co. official says. 2020. https://www.wusa9.com/article/news/health/coronavirus/fairfax-county-police-see-increase-in-domestic-related-calls-during-coronavirus-pandemic/65-36e9918b-b5e9-432b-9713-5bb75d947e17

- Selvaratnam T. 2020. Where can domestic violence victims turn during covid-19? The New York times.https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/23/opinion/covid-domestic-violence.html March 23. [Google Scholar]

- Stylianou A.M., Counselman-Carpenter E., Redcay A. “My sister is the one that made me stay above water”: How social supports are maintained and strained when survivors of intimate partner violence reside in emergency shelter programs. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2018 doi: 10.1177/0886260518816320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarzia L., Cornelio R., Forsdike K., Hegarty K. Women’s experiences receiving support online for intimate partner violence: How does it compare to face-to-face support from a health professional? Interacting with Computers. 2018;30(5):433–443. doi: 10.1093/iwc/iwy019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zarroli J., Schneider A. Deluge continues: 26 millions jobs lost in just 5 weeks. National Public Radio. 2020;April 23 [Google Scholar]