Abstract

This article, from the “To the Point” series by the Undergraduate Medical Education Committee of the Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics, is a guide for advising medical students applying to Obstetrics and Gynecology residency programs. The residency application process is changing rapidly in response to an increasingly complex and competitive atmosphere, with a wider recognition of the stress, expense, and difficulty of matching into graduate training programs. The coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic and societal upheaval make this application cycle more challenging than ever before. Medical students need reliable, accurate, and honest advising from the faculty in their field of choice to apply successfully to residency. The authors outline a model for faculty career advisors, distinct from mentors or general academic advisors. The faculty career advisor has detailed knowledge about the field, an in-depth understanding of the application process, and what constitutes a strong application. The faculty career advisor provides accurate information regarding residency programs within the specialty, helping students to strategically apply to programs where the student is likely to match, decreasing anxiety, expense, and overapplication. Faculty career advisor teams advise students throughout the application process with periodic review of student portfolios and are available for support and advice throughout the process. The authors provide a guide for the faculty career advisor in Obstetrics and Gynecology, including faculty development and quality improvement.

Key words: advising, faculty career advisors, medical students, Obstetrics and Gynecology residency, undergraduate medical education

Introduction

Medical students often cite career advising as an area of unmet need, and rank guidance from faculty career advisors (FCAs) in their chosen specialty as the most helpful resource in the residency application process.1, 2, 3, 4 General advisors without an in-depth knowledge of the specialty may provide inaccurate counseling, whereas clerkship directors (CDs) and residency program directors (PDs) may not have time, resources, or training to excel at career advising.5 The rapid changes in the 2020–2021 application cycle owing to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) demonstrate the need for FCAs with both specialty-specific knowledge and an overall understanding of the application process.6

This article, one in the faculty development series “To The Point” by the Undergraduate Medical Education Committee of the Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics (APGO), is intended as a guide to advising medical students applying for Obstetrics and Gynecology (OBGYN) residency programs through the main residency Match of the National Residency Matching Program (NRMP).

Faculty Career Advisor’s Role and Responsibilities

The FCA fills a unique advising role, distinct from academic advisors, mentors, or coaches. FCAs are knowledgeable about the specialty, application process, and residency programs.7 , 8 Despite up to 90% of faculty performing some career advising, the role is often considered low status.9 , 10 Although the FCA role is often considered part of CD duties, FCAs should receive institutional recognition as advisors for the residency application process and should receive protected time to meet with and advise students commensurate with the number of advisees.9 , 11 , 12 There are no guidelines for the ideal student-to-advisor ratio, and in some specialties, FCAs advise more than 20 students annually.13

FCAs should frequently review the online resources published by the NRMP, Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), and other national organizations (Table 1 ). These websites are updated at least annually and provide a comprehensive view of the application process and updates on current conditions. The APGO OBGYN Residency Directory (https://www.apgo.org/students/) provides a concise listing and comparison of residency programs, which is a vital resource for students and advisors. Medical schools should provide FCAs with an access to the AAMC Careers in Medicine (CiM) website.14 Students can access CiM for career choice guidance. FCAs should also be aware of student-led websites that may be less reliable than those of professional organizations.15

Table 1.

Online advising resources

| Resource | Sponsor | Features |

|---|---|---|

| FRIEDA | AMA | Fellowship and residency electronic interactive database listing of all ACGME-accredited residency and fellowship programs in the United States and Canada |

| “The Road to Residency” video series. | ||

| Careers in Medicine | AAMC | Self-assessment for specialty choice |

| Residency preference exercise | ||

| Advice blogs | ||

| Career planning tools | ||

| NRMP | NRMP | Extensive information for applicants, advisors, medical schools, and residency programs |

| Couples Matching | NRMP | Detailed information for applicants and advisors on the couples matching process |

| Transforming Residency | APGO | Specialty-wide standards for the OBGYN residency application and interview processes |

| OBGYN Residency Directory | APGO | Listing of all OBGYN residency programs in the United States and Canada with detailed program data and links to program websites |

| Residency Explorer | AAMC | Applicants can compare residency programs and applicant’s profile with matched applicants at each program in 11 specialties |

| Effective Student Advising Series | APGO | Best practice guidelines for advisors in OBGYN |

AAMC, Association of American Medical Colleges; ACGME, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; AMA, American Medical Association; APGO, Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics; FREIDA, Fellowship and Residency Electronic Interactive Database; NRMP, National Residency Matching Program; OBGYN, Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Royce. Advising students applying to OBGYN residency 2020. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021.

Specialty FCA teams should meet regularly to review recent changes in the application process, ensuring equitable, accurate advice for all students. Successful teams work together to maximize outcomes for all students.

Medical students often have a limited understanding of the residency application process.4 Women and first-generation and underrepresented minority students may be less likely to use networking or have mentors.8 , 16 , 17 FCAs can help achieve opportunity equity by providing specialty-specific information about competitiveness and factors considered in granting interviews and ranking candidates.4 , 13

Early Career Advising

Advising preclerkship students includes mentorship, networking, and informational meetings.4 FCAs can help clarify career goals and identify research, extracurricular, and leadership opportunities.4 , 13 , 18 , 19

Certainty and compatibility

Once a student decides to pursue OBGYN, the FCA should assess a student’s motivation and ensure understanding of residency training commitments.19 Discussing career goals, plans for fellowship, research, advocacy, and topics such as abortion and assisted reproduction helps the FCA guide students’ program choices.13

Review portfolio

The FCA should review the student’s curriculum vitae (CV) using the standardized AAMC CV or a school’s recommended style.14 , 20 The student should accurately describe activities and research, taking credit for work done, but not overstating achievements. If a student participated in research without a resulting publication, the FCA can recommend poster or abstract presentation opportunities or suggest writing a manuscript with the research mentor.

The CV should highlight activities highly valued by residency programs including leadership, advocacy, teaching, honors and awards, such as the Gold Humanism Honor Society and Alpha Omega Alpha. Student membership in professional societies such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) demonstrates commitment to the field.

The FCA should review potential weaknesses, including illness or adversities that affected academic achievement. A low grade or score can be an opportunity to demonstrate resilience. For students with a lapse in professionalism, legal action, or criminal conviction, the FCA can coach the student through an honest appraisal of the episode to provide a path to a successful match.

The FCA should also assess interpersonal skills and offer communications or public speaking training if needed.21 , 22

FCAs must understand the school’s grading rubric and the Medical Student Performance Evaluation (MSPE), which is the standardized narrative summarizing the student’s achievements, grades, evaluations, and class rank.23 Many schools invite students to highlight achievements for the MSPE. FCAs can advise students to list attributes based on personal knowledge of the student and of factors valued by residency programs.

Postclerkship Planning

FCAs advise students on postclerkship electives, research, and extracurricular activities to promote professional development and build a competitive portfolio.18

Away electives

Because of COVID-19, in 2020–2021, the AAMC recommended limiting away rotations to students whose medical schools do not offer equivalent clinical experiences.6 , 24 FCAs can reassure students there seems to be no association between completing away electives and matching at an institution, whereas a poor performance hurts a student’s chances.25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32

Postclerkship curriculum

FCAs should recommend electives to broaden medical knowledge, such as cardiology, infectious disease, emergency medicine, dermatology, critical care, or neonatology.13 , 25 , 33, 34, 35 Students should plan flexible schedules during interviews and complete an elective with direct patient care in the months before graduation and, if available, a Transition-to-Residency course.34 , 36, 37, 38 A “Step Up to Residency” program is offered at the annual ACOG meeting.34 , 39

Some students take a fifth year; for less academically competitive students, research, publications, or a second degree may bolster their portfolio. The FCA should maintain regular contact with students during time away. At a minimum, hold a midyear conversation to confirm career plans and assure student well-being.

Networking

The FCA should ensure students meet with the Chair to discuss the departmental letter of recommendation (LOR).40 The Chair may delegate writing the LOR, but personal knowledge of the applicant is desirable. The student should send the CV and personal statement (PS) for review before the meeting, bring extra copies to the meeting, and be prepared to discuss their application. Meeting with the department Chair helps build student confidence for interviews. With current travel limitations, FCA teams can maximize networking through introductions to faculty at desired programs with similar clinical or research interests.

Assembling the Application

Holistic review

The FCA and student should review the Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) application, including the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) or Comprehensive Osteopathic Medical Licensing Examination (COMLEX-USA) scores, grades, research, teaching, volunteer and work experience, publications, and extracurricular activities. Preferences for program size, type, location, and whether the student is couples matching should be discussed. The FCA can then suggest programs where the student is likely to receive interviews.

Letters of recommendation

Students applying in OBGYN should submit at least 3 LORs including a letter from the department Chair.40 Because of the pandemic, the Council on Resident Education in Obstetrics and Gynecology (CREOG) and others recommend programs require fewer LORs for the 2020–2021 cycle.6 , 41 FCAs should advise choosing faculty, research mentors, or project supervisors who know the student personally and who can comment on strengths and fitness for residency.40 Authors from other specialties may be considered. Students should request a LOR at the time they work with the author and meet to review their portfolio. Students should be mindful of the time required to write LORs and request letters early enough to meet deadlines.

Personal statement

The FCA plays a critical role in reviewing the PS.42 Although the PS is the only place in the application where the student’s voice is heard, students often struggle with writing.42, 43, 44 A reflection exercise to identify strengths, weaknesses, career goals, and desired program characteristics leads to a well-organized, effective PS.42

The PS should focus on the student’s goals and what the student seeks in and brings to residency, rather than a patient or family story or why the student chose medicine.45 , 46 The tone should be professional and positive, avoiding criticism of the field, particular institutions, or individuals. Weaknesses should be addressed in a psychologically safe manner, with an emphasis on growth from adversity.42 , 47 The FCA should proofread and suggest edits, but refrain from revision. The PS should be the student’s own work; a recent report found a 2.6% incidence of plagiarism in the PS.48

Social media

Modern professionalism includes cultivation of an online social media presence.49 More than half of PDs report screening applicants’ social media for unprofessional behavior.50, 51, 52, 53, 54 Reassuringly, a recent study of 87 OBGYN applicants found no unprofessional postings.55 Social media is also an opportunity for student networking with the medical community through education, research, and commentary.56, 57, 58

Background for Advisors

Competitiveness of Obstetrics and Gynecology as a specialty

Interest in OBGYN has grown recently, with 5% to 6% of United States medical school graduates and 2% of foreign medical graduates entering OBGYN residencies.30 Applicants increased from 1335 in 2010 to 2026 in 2019.30 In 2020, there were 1413 preliminary postgraduate year 1 spots, with 1.12 positions for each applicant in the United States.30 , 59

Assessing competitiveness

The FCA can help students assess their competitiveness in comparison with classmates and with the entire applicant field.26 To ensure adequate interviews for all students, FCAs should advise students to apply strategically based on attributes valued at different programs, because residency programs often interview only a few candidates per school. This requires FCA teams to work collaboratively, equitably advising all applicants, while maintaining confidentiality.

Recent changes

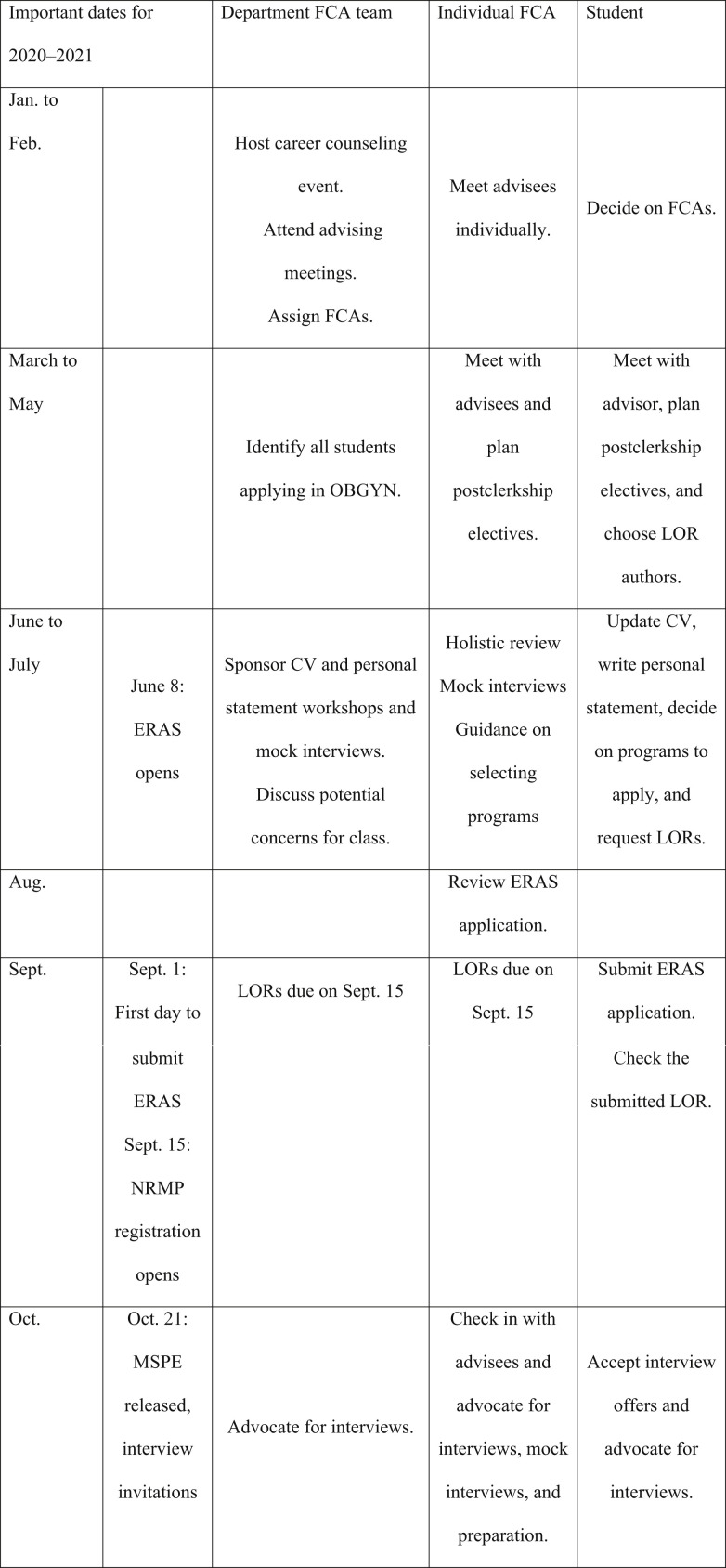

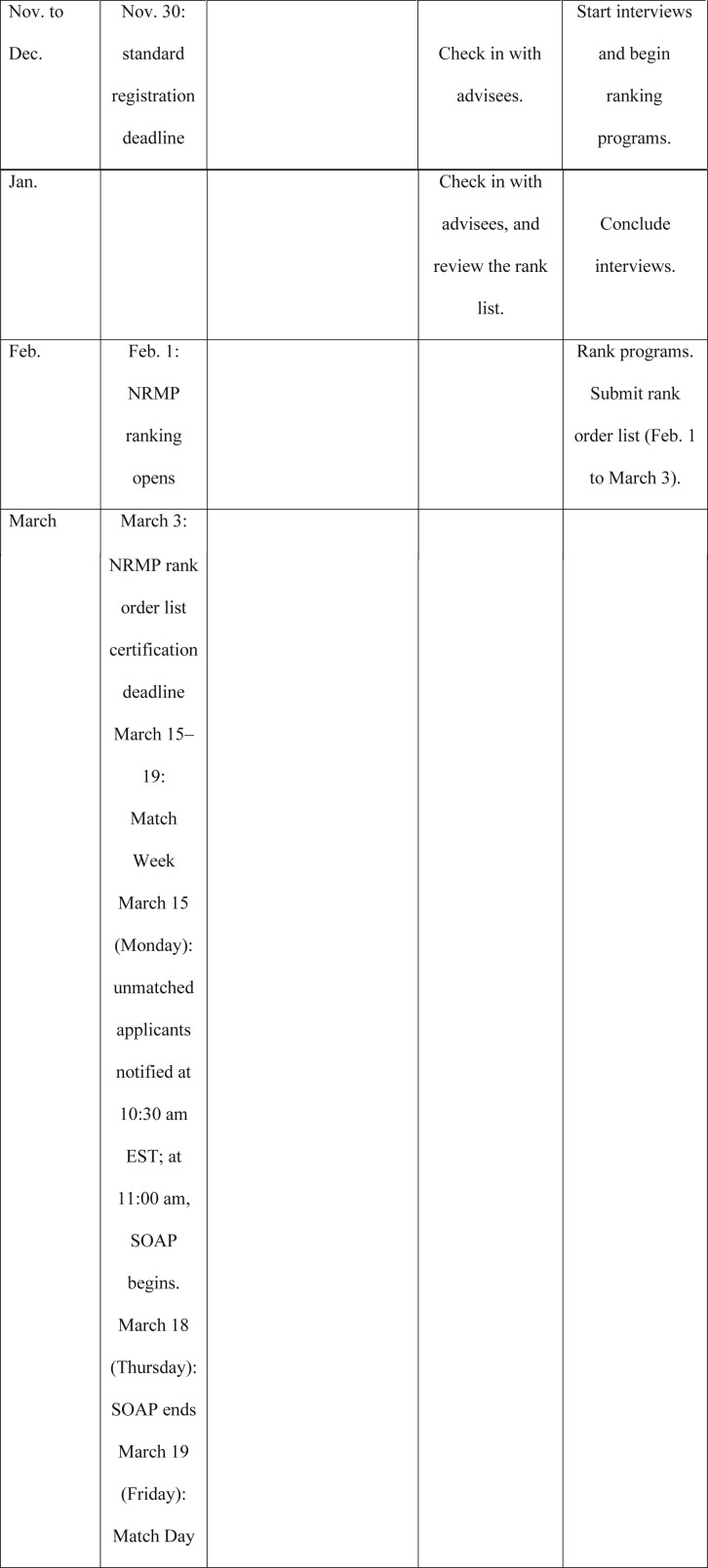

National efforts are underway to simplify the application process.60 In 2019, OBGYN became the first specialty to recommend residency programs limit the number of invitations extended to only the number of interviews available, standardize invitation dates, and give a realistic response time to accept invitations.60 Figure 1 provides an overview of the advising timeline including adjustments made in the current year in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure.

Timeline for residency application process in Obstetrics and Gynecology

All dates adjusted for the 2020–2021 cycle.

CV, curriculum vitae; ERAS, Electronic Residency Application Service; EST, Eastern Standard Time; FCA, faculty career advisor; LOR, letter of recommendation; MSPE, Medical Student Performance Evaluation; NRMP, National Residency Matching Program; OBGYN, Obstetrics and Gynecology; SOAP, supplemental offer and acceptance program.

Royce. Advising students applying to OBGYN residency 2020. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021.

Program Director’s Perspective

Attributes considered in granting interviews

PDs most frequently cite USMLE Step 1 scores as a factor in offering interviews, because standardized tests are viewed as an objective measure of academic achievement and potential for completing residency and passing licensing exams.61 Most programs do not specify a required Step 1 score; however, in 2019, the median score for matched applicants was 229 (interquartile range, 218–240).61 For less academically competitive candidates, including Step 2 scores in the initial application may boost chances for an interview. Other factors cited include LORs, Step 2 scores, PS, and the MSPE.30 , 59 Grades, class rank, publications, research, and work or volunteer experiences are less commonly cited factors.

In 2019, the National Board of Medical Examiners announced Step 1 will become pass/fail62; the effects of this change are uncertain, but may prompt the use of holistic reviews and may change recommendations for the number of applications to submit.6

Attributes considered in ranking

When ranking applicants to match, PDs consistently cite interpersonal interactions and communication skills as the most important attribute.61 Although academic excellence is often required to receive interviews, interpersonal skills are the deciding factor in ranking candidates. In 2020, all interviews will be virtual. Although concerns exist that this will adversely affect perceptions of communication skills,63 a pilot study in anesthesiology comparing virtual and face-to-face interviews reported no difference in matching results.64

The Application Process

Applying to residency programs: which ones and how many?

Applying for residency is expensive and time consuming. For OBGYN in 2019, students submitted a mean of 61.3 applications, whereas programs received an average of 438.1 total applications.61 , 65 Students frequently overapply out of concerns for not matching.7 FCAs can guide students to limit the number of programs at which they apply through a strategic approach including student interests, plans, and academic record.

In deciding where to apply, students consider clinical interests, academic competitiveness, geography, couples matching, and finances.13 Research and advocacy opportunities, patient population, and diversity are additional factors. FCAs can help students limit the overall number of applications by considering other aspects of their planned career paths in selecting programs at which to apply. For example, students interested in a nonacademic career may consider community hospital programs over academic medical center programs, whereas students planning to subspecialize may wish to apply to programs with associated fellowships. Students should apply to their home institution’s programs, unless they are certain they will not stay for residency.

In determining the number of applications, the AAMC “point of diminishing returns” (PDR) tool uses Step 1 scores to predict the number of programs needed to apply to match successfully.14 In OBGYN, applicants with a score of ≥230 needed to apply to 14 programs (confidence interval [CI], 13–15) to reach the highest likelihood of matching successfully: adding more applications did not increase the chances of a successful match. For scores of 214 to 229, the PDR was 21 programs (CI, 19–23), with an 82% likelihood of matching. For scores of <213, the PDR was 28 programs (CI, 26–30) with a 76% likelihood of matching. Approximately 90% of OBGYN applicants ranking ≥10 programs matched; more than 99% of applicants ranking ≥20 programs matched.14 Because of the decreased expenses associated with virtual interviews, students may consider overapplying during the 2020 application cycle. FCAs can use the PDR to encourage limiting the number of applications. In this fluid, competitive environment, less academically competitive students may need to apply to up to 30 programs to receive interviews (and thus rank sufficient programs), whereas highly competitive students may need to only apply to 10 to 14 programs.5 , 7

The process of deciding which programs at which to apply may become simplified with proposed changes resulting from the pandemic, including more transparent communication from programs regarding program values and desired applicant characteristics.6

Interview preparation and reflection

The FCA can assist students with mock interviews and review recent graduates’ experiences.21 , 22 Because few students have experience with online interviews, FCA teams should offer specific training and mock virtual interviews for the 2020 application cycle.63 Results from a prepandemic online interview pilot demonstrating equivalence of outcome with in-person interviews may reassure students.64 Students should explore program websites and attend online social events if offered to understand programs’ values, mission, and desired candidate qualities.6 During the interview season, FCAs should contact advisees regularly to review interview invitations and reflect on impressions and rank programs as they complete interviews.66

Postinterview communications

Students are often unsure about communicating with programs after interviews. Programs generally welcome notification of new publications or awards. Students should not falsely promise to rank a program first but may wish to inform a program of specific reasons they are ranking a program first, such as a spouse at the same institution. Communication from a program does not necessarily indicate a student will be ranked highly. Both candidates and programs are governed in behavior and communication by the NRMP Code of Conduct that prohibits programs from mandating second interviews and audition rotations or asking how the candidate will rank the program.61

Final step: rank order list

Before submission, the FCA should review students’ rank list. Students should rank programs in their preferred order. By ranking a program, the student is agreeing to employment at that program. Students should not rank a program they do not wish to attend. The NRMP recommends submitting the list before the deadline, because internet or website failures have occurred.61

Couples Matching

FCAs should understand the special concerns of couples matching, described in detail at the NRMP website (http://www.nrmp.org/couples-in-the-match/). For couples, each student must rank the same number of programs or options, up to a total of 300 combinations of residency programs, including “no match” options.61 The couple will match to the most preferred pair of programs on the rank order lists where each partner has been offered a position (or a “no match” option is listed). A frank appraisal of each student’s competitiveness in their specialty is essential to ensuring the best match for both students. In general, both students will need to apply to more programs than an individual student.61 Couples should decide whether they are willing to train in different geographic locations or whether either is willing to delay training for a year. Couples should turn in their rank order lists early, because both applicants’ lists will be rejected if there are discrepancies, and they must be resubmitted in time for the deadline.61

Supplemental Offer and Acceptance Program

Students are notified of match status on Monday of Match week. Applicants who have not matched may then enter the supplemental offer and acceptance program (SOAP). Residency programs with open slots can contact students directly during SOAP. Students or their representatives may not initiate contact before 3:00 pm Eastern Standard Time on that Monday and must go through ERAS to contact programs.67 Applicants in violation of the NRMP rules can be barred from future participation in the match.

In the immediate postmatch time frame, the FCA can offer support for the unmatched student, because this is often emotionally stressful.68 Bumsted et al68 provide an overview of SOAP and alternatives for achieving a residency position. After the closure of SOAP, the NRMP releases a list of unfilled programs. The FCA can assist the applicant in identifying programs because FCAs may learn of open positions in the specialty before general advisors.68 If an applicant does not match through the traditional match but obtains a preliminary position, the FCA should maintain contact and offer to review a second application.68 , 69

Effects of Coronavirus Disease 2019

In response to the pandemic, most American medical schools suspended educational and research activities in March 2020, resulting in decreased opportunities for students to prepare for residency. Changes in the application cycle were instituted by the AAMC, whereas APGO/CREOG recommended OBGYN-specific changes (Table 2 ).6 , 70 , 71

Table 2.

COVID-19–related changes to the residency application process

| Sponsoring entity | Recommendation for the 2020–2021 application cycle | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Coalition for Physician Accountability | Limitation on away rotations, except under the following circumstances:

|

Voluntary |

All programs commit to the following:

|

Voluntary | |

| Delayed ERAS opening | Delayed to Oct. 21, 2020 | |

| Delayed MSPE release | Delayed to Oct. 21, 2020 | |

| APGO and CREOG | Flexibility in the number and type of LOR | Voluntary |

| Residency Response | Develop innovative alternatives for virtual program information | Voluntary |

| Information for applicants |

|

Voluntary |

APGO, Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CREOG; Council on Resident Education in Obstetrics and Gynecology; ERAS, Electronic Residency Application Service; LOR, letter of recommendation; MSPE, Medical Student Performance Evaluation; NRMP, National Residency Matching Program.

Royce. Advising students applying to OBGYN residency 2020. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021.

As Ferrell and Ryan72 noted in April 2020, “The panic in the community is palpable, and many are confused by how to proceed in the wake of COVID-19” because the normal methods for demonstrating achievement are severely limited. Students may face added stress from societal upheaval, family illness, financial stress, and rising inequities. In light of the pandemic, virtual mentor relationships such as FCAs remain the educational intervention most desired by students.73 The APGO/CREOG specifically recommend students work with an FCA during this application cycle.41 , 74 FCAs should review the recent general and OBGYN-specific changes to the application process to accurately advise students.6 , 60 New FCA roles in 2020 include virtual interview preparation and electronic networking.63

Improving Advising: Continuous Quality Improvement

Resources

FCA teams should update local student resources regularly. Medical schools should provide current data, including programs where students have recently matched. FCA groups may conduct informal surveys or focus groups of graduates to elicit hard-to-capture data regarding student experiences.

Faculty development

The FCA is a novel role evolving to meet the needs of students during the residency application process. The pool of faculty serving as FCAs may vary from school to school, including subspecialists. Although no formal training programs exist, APGO and other specialty societies have published resources to assist faculty members as they develop the skills needed to successfully serve as FCAs.18, 19, 20, 21, 22 , 26 , 42 Online resources are listed in Table 1. FCA teams can improve advising through standardized programs, sharing best practices, case-based critical review of recent student experiences, and reflection on their own experiences to inform advising style and substance.75

Continuous quality improvement

FCA teams should meet annually after the match, to debrief, inviting administrative staff who often have a different perspective on student experiences. Recently, evaluation tools for undergraduate medical education programs have been published and may be used to identify and adopt best practices.76 , 77

Conclusion

Effective FCAs possess a deep understanding of the application process and residency programs and use holistic review techniques of student compatibility to maximize students’ success in matching into a desired residency. As the postpandemic medical education landscape evolves, the application process will undoubtably change, and specialty-specific FCA guidance will remain invaluable.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Speicher M.R., Pradhan S.R. Advising needs of osteopathic medical students preparing for the match. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2016;116:228–233. doi: 10.7556/jaoa.2016.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zink B.J., Hammoud M.M., Middleton E., Moroney D., Schigelone A. A comprehensive medical student career development program improves medical student satisfaction with career planning. Teach Learn Med. 2007;19:55–60. doi: 10.1080/10401330709336624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macaulay W., Mellman L.A., Quest D.O., Nichols G.L., Haddad J., Puchner P.J. The advisory dean program: a personalized approach to academic and career advising for medical students. Acad Med. 2007;82:718–722. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3180674af2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Englander R., Carraccio C., Zalneraitis E., Sarkin R., Morgenstern B. Guiding medical students through the match: perspectives from recent graduates. Pediatrics. 2003;112(3 Pt 1):502–505. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.3.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alston M.J., Autry A.M., Wagner S.A., Allshouse A.A., Stephenson-Famy A. Advising and interview patterns of medical students pursuing obstetrics and gynecology residency. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(Suppl1):17–22S. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hammoud M.M., Standiford T., Carmody J.B. Potential implications of COVID-19 for the 2020-2021 residency application cycle. JAMA. 2020;324:29–30. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strand E.A., Sonn T.S. The residency interview season: time for commonsense reform. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:1437–1442. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allen J.M., Smith C.L. Importance of, responsibility for, and satisfaction with academic advising: a faculty perspective. J Coll Stud Dev. 2008;49:397–411. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Habley W.R. National Academic Advising Association; Manhattan, KS: 2004. The status of academic advising: findings from the ACT Sixth National Survey. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dillon R.K., Fisher B.J. Faculty as part of the advising equation: an inquiry into faculty viewpoints on advising. NACADA J. 2000;20:16–23. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee P.R., Marsh E.B. Mentoring in neurology: filling the residency gap in academic mentoring. Neurology. 2014;82:e85–e88. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dimitriadis K., von der Borch P., Störmann S. Characteristics of mentoring relationships formed by medical students and faculty. Med Educ Online. 2012;17:17242. doi: 10.3402/meo.v17i0.17242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chretien K.C., Elnicki D.M., Levine D., Aiyer M., Steinmann A., Willett L.R. What are we telling our students? A national survey of clerkship directors’ advice for students applying to internal medicine residency. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7:382–387. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-14-00552.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Careers in medicine. Association of American Medical Colleges. 2019. https://www.aamc.org/cim/ Available at:

- 15.2020 OB GYN residency applicant spreadsheet. Student Doctor Network. 2020. https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1hWB524xXJkxui2SyAHIJYL2MLP8pZF2IbgW_wzwpZGE/edit#gid=195627284 Available at:

- 16.Uy P.S., Kim S.J., Khuon C. College and career readiness of Southeast Asian American college students in New England. J Coll Stud Retent Res Theor Pract. 2019;20:414–436. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Funk P.E., Knott P., Burdick L., Roberts M. Development of a novel pathways program for pre-health students by a private four-year university and a private health professions university. J Physician Assist Educ. 2018;29:150–153. doi: 10.1097/JPA.0000000000000218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hampton B.S., Cox S.M., Craig L.B. Effective student advising series: year by year path to residency application. Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2020. https://www.apgo.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/1-APGO-ESAS-Timeline.pdf Available at:

- 19.Hampton B.S., Cox S.M., Craig L.B. Effective student advising series: what makes a student a good fit for Ob-Gyn? Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2020. https://www.apgo.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/3-APGO-ESAS-Good-Fit-for-Ob-Gyn.pdf Available at:

- 20.Hampton B.S., Cox S.M., Craig L.B. Effective student advising series: how to guide your students to an outstanding CV. Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2020. https://www.apgo.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/5-APGO-ESAS-Outstanding-CV.pdf Available at:

- 21.Hampton B.S., Cox S.M., Craig L.B. Effective student advising series: guide your students to a great interview. Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2020. https://www.apgo.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/8-APGO-ESAS-Great-Interview.pdf Available at:

- 22.Donaldson K., Sakamuri S., Moore J., Everett E.N. A residency interview training program to improve medical student confidence in the residency interview. MedEdPORTAL. 2020;16:10917. doi: 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Recommendations for revising the medical student performance evaluation (MSPE). Association of American Medical Colleges. 2017. https://www.aamc.org/download/470400/data/mspe-recommendations.pdf Available at:

- 24.Medical student away rotations and in-person interviews for 2020-21 residency cycle. Association of American Medical Colleges. 2020. https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/mission-areas/medical-education/away-rotations-interviews-2020-21-residency-cycle Available at:

- 25.Lyss-Lerman P., Teherani A., Aagaard E., Loeser H., Cooke M., Harper G.M. What training is needed in the fourth year of medical school? Views of residency program directors. Acad Med. 2009;84:823–829. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a82426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hampton BS, Cox S, Craig LB, et al. Advising 4th-Year Students for a Successful Ob-Gyn Match. Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics Effective Student Advising Series. Available at: https://nam03.safelinks.protection.outlook.com/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcdn.ymaws.com%2Fapgo.org%2Fresource%2Fresmgr%2F4_apgo_esas_-_successful_mat.pdf&data=04%7C01%7CB.Arnold%40Elsevier.com%7C93b6b4c13ae6446da2f108d8916a7eed%7C9274ee3f94254109a27f9fb15c10675d%7C0%7C1%7C637419234647533288%7CUnknown%7CTWFpbGZsb3d8eyJWIjoiMC4wLjAwMDAiLCJQIjoiV2luMzIiLCJBTiI6Ik1haWwiLCJXVCI6Mn0%3D%7C1000&sdata=fF%2B1F6QGEuNVIwZigVccLuyeKc6ixRkRTNUlE5B1%2Bp4%3D&reserved=0. Accessed November 25, 2020.

- 27.Fabri P.J., Powell D.L., Cupps N.B. Is there value in audition extramurals? Am J Surg. 1995;169:338–340. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(99)80171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baldwin K., Weidner Z., Ahn J., Mehta S. Are away rotations critical for a successful match in orthopaedic surgery? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:3340–3345. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0920-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wood J.S., David L.R. Outcome analysis of factors impacting the plastic surgery match. Ann Plast Surg. 2010;64:770–774. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181b4bcf5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Results and data: 2019 main residency match. National Resident Matching Program. 2020. https://www.nrmp.org/new-2019-main-residency-match-by-the-numbers/ Available at:

- 31.Vogt H.B., Thanel F.H., Hearns V.L. The audition elective and its relation to success in the National Resident Matching Program. Teach Learn Med. 2000;12:78–80. doi: 10.1207/S15328015TLM1202_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huggett K.N., Borges N.J., Jeffries W.B., Lofgreen A.S. Audition electives: do audition electives improve competitiveness in the National Residency Matching Program? Ann Behav Sci Med Educ. 2010;16:32–39. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elnicki D.M., Gallagher S., Willett L. Course offerings in the fourth year of medical school: how U.S. medical schools are preparing students for internship. Acad Med. 2015;90:1324–1330. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Forstein D.A., Buery-Joyner S.D., Abbott J.F. A curriculum for the fourth year of medical school. A survey of obstetrics and gynecology educators. J Rep Med. 2019;64:247–254. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hueston W.J., Koopman R.J., Chessman A.W. A suggested fourth-year curriculum for medical students planning on entering family medicine. Fam Med. 2004;36:118–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Esterl R.M.J., Henzi D.L., Cohn S.M. Senior medical student “Boot Camp”: can result in increased self-confidence before starting surgery internships. Curr Surg. 2006;63:264–268. doi: 10.1016/j.cursur.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morgan H., Skinner B., Marzano D., Fitzgerald J., Curran D., Hammoud M. Improving the medical school-residency transition. Clin Teach. 2017;14:340–343. doi: 10.1111/tct.12576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Antonoff M.B., Swanson J.A., Green C.A., Mann B.D., Maddaus M.A., D’Cunha J. The significant impact of a competency-based preparatory course for senior medical students entering surgical residency. Acad Med. 2012;87:308–319. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318244bc71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.2019 step up to residency CREOG and APGO program. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2019. https://www.acog.org/education-and-events/creog/curriculum-resources/step-up-to-residency Available at:

- 40.Hampton B.S., Cox S.M., Craig L.B. Effective student advising series: writing residency letters of recommendation. Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2020. https://www.apgo.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/7-APGO-ESAS-Letter-of-Recommendation.pdf Available at:

- 41.Updated APGO and CREOG residency application response to COVID-19. Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Council on Resident Education in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2019. https://www.apgo.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Updated-APGO-CREOG-Residency-Response-to-COVID-19-.pdf Available at:

- 42.Hampton BS, Cox S, Craig LB, et al. Fourth Year Advising Project: Writing the Personal Statement. Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics Effective Student Advising Series. Available at: https://nam03.safelinks.protection.outlook.com/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcdn.ymaws.com%2Fapgo.org%2Fresource%2Fresmgr%2F6_apgo_esas_-_personal_state.pdf&data=04%7C01%7CB.Arnold%40Elsevier.com%7C93b6b4c13ae6446da2f108d8916a7eed%7C9274ee3f94254109a27f9fb15c10675d%7C0%7C1%7C637419234647533288%7CUnknown%7CTWFpbGZsb3d8eyJWIjoiMC4wLjAwMDAiLCJQIjoiV2luMzIiLCJBTiI6Ik1haWwiLCJXVCI6Mn0%3D%7C1000&sdata=ZV%2FUPhkCmMUcJ8v%2B7ldAkEGTU2F1MabOvKo%2Br39LLYo%3D&reserved=0. Accessed November 25, 2020.

- 43.White B.A.A., Sadoski M., Thomas S., Shabahang M. Is the evaluation of the personal statement a reliable component of the general surgery residency application? J Surg Educ. 2012;69:340–343. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Badal J.J., Jacobsen W.K., Holt B.W. Behavioral evaluations of anesthesiology residents and overuse of the first-person pronoun in personal statements. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3:151–154. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-10-00117.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hofmeister E.H., Diehl K.A., Creevy K.E., Pashmakova M., Woolcock A., Lyon S. Analysis of small animal rotating internship applicants’ personal statements. J Vet Med Educ. 2019;46:28–34. doi: 10.3138/jvme.0617-071r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Osman N.Y., Schonhardt-Bailey C., Walling J.L., Katz J.T., Alexander E.K. Textual analysis of internal medicine residency personal statements: themes and gender differences. Med Educ. 2015;49:93–102. doi: 10.1111/medu.12487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Elliott D, Armitage K, Hanna E, Kavan MG, Fried J. Optimizing the learner handoff from UME to GME: how to best transmit sensitive information. Paper presented at: National Resident Matching Program Annual Conference. Transition to Residency: Conversations across the Medical Education Continuum; October 13–15, 2019; Chicago, IL.

- 48.Maruca-Sullivan P.E., Lane C.E., Moore E.Z., Ross D.A. Plagiarised letters of recommendation submitted for the National Resident Matching Program. Med Educ. 2018;52:632–640. doi: 10.1111/medu.13546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaczmarczyk J.M., Chuang A., Dugoff L. e-Professionalism: a new frontier in medical education. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25:165–170. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2013.770741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Go P.H., Klaassen Z., Chamberlain R.S. Residency selection: do the perceptions of US programme directors and applicants match? Med Educ. 2012;46:491–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Go P.H., Klaassen Z., Chamberlain R.S. Attitudes and practices of surgery residency program directors toward the use of social networking profiles to select residency candidates: a nationwide survey analysis. J Surg Educ. 2012;69:292–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Golden J.B., Sweeny L., Bush B., Carroll W.R. Social networking and professionalism in otolaryngology residency applicants. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:1493–1496. doi: 10.1002/lary.23388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ponce B.A., Determann J.R., Boohaker H.A., Sheppard E., McGwin G., Theiss S. Social networking profiles and professionalism issues in residency applicants: an original study-cohort study. J Surg Educ. 2013;70:502–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Langenfeld S.J., Vargo D.J., Schenarts P.J. Balancing privacy and professionalism: a survey of general surgery program directors on social media and surgical education. J Surg Educ. 2016;73:e28–e32. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sullivan M.E., Frishman G.N., Vrees R.A. Showing your public face: does screening social media assess residency applicants’ professionalism? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:619–620. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hanzel T., Richards J., Schwitters P. #DocsOnTwitter: how physicians use social media to build social capital. Hosp Top. 2018;96:9–17. doi: 10.1080/00185868.2017.1354558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Breu A.C. From tweetstorm to tweetorials: threaded tweets as a tool for medical education and knowledge dissemination. Semin Nephrol. 2020;40:273–278. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2020.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cai F., Burns R.N., Kelly B., Hampton B.S. CREOGs over coffee: feasibility of an Ob-Gyn medical education podcast by residents. J Grad Med Educ. 2020;12:340–343. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-19-00644.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.National Resident Matching Program Charting outcomes in the match, specialties matching service. https://www.nrmp.org/nrmpaamc-charting-outcomes-in-the-match/ Available at:

- 60.Hammoud MM, Andrews J. Residency Selection: can the process be improved? Paper presented at: National Resident Matching Program Annual Conference. Transition to Residency: Conversations across the Medical Education Continuum; October 13–15, 2019; Chicago, IL.

- 61.Main residency match data and reports. National Resident Matching Program. 2020. http://www.nrmp.org/main-residency-match-data/ Available at:

- 62.Barone M., Filak A., Johnson D., Skochelak S., Whelan A. Summary report and preliminary recommendations from the invitational conference on USMLE scoring (InCUS), March 11-12, 2019. 2019. https://www.usmle.org/pdfs/incus/incus_summary_report.pdf Available at:

- 63.Jones R.E., Abdelfattah K.R. Virtual interviews in the era of COVID-19: a primer for applicants. J Surg Educ. 2020;77:733–734. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vadi M.G., Malkin M.R., Lenart J., Stier G.R., Gatling J.W., Applegate R.L., 2nd Comparison of web-based and face-to-face interviews for application to an anesthesiology training program: a pilot study. Int J Med Educ. 2016;7:102–108. doi: 10.5116/ijme.56e5.491a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.ERAS statistics. Association of American Medical Colleges. 2019. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/students-residents/report/eras-statistics Available at:

- 66.Kalén S., Ponzer S., Silén C. The core of mentorship: medical students’ experiences of one-to-one mentoring in a clinical environment. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2012;17:389–401. doi: 10.1007/s10459-011-9317-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Policies and pitfalls for applicants: SOAP. National Resident Matching Program. 2018. https://www.nrmp.org/applicant-policy-pitfalls-soap/ Available at:

- 68.Bumsted T., Schneider B.N., Deiorio N.M. Considerations for medical students and advisors after an unsuccessful match. Acad Med. 2017;92:918–922. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rawlings A., Doty J., Frevert A., Quick J. Finding them a spot: a successful preliminary match curriculum. J Surg Educ. 2018;75:e78–e84. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gabrielson A.T., Kohn J.R., Sparks H.T., Clifton M.M., Kohn T.P. Proposed changes to the 2021 residency application process in the wake of COVID-19. Acad Med. 2020;95:1346–1349. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.The Coalition for Physician Accountability’s Work Group on Medical Students in the Class of 2021 Moving Across Institutions for Post Graduate Training Final report and recommendations for medical education institutions of LCME-accredited, U.S. osteopathic, and non-U.S. medical school applicants. Association of American Medical Colleges. 2020. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2020-05/covid19_Final_Recommendations_05112020.pdf Available at:

- 72.Ferrel M.N., Ryan J.J. The impact of COVID-19 on medical education. Cureus. 2020;12:e7492. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Guadix S.W., Winston G.M., Chae J.K. Medical student concerns relating to neurosurgery education during COVID-19. World Neurosurg. 2020;139:e836–e847. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.05.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Right resident, right program, ready day one: APGO and CREOG guidelines for students applying for an Ob-Gyn residency. Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2020. https://www.apgo.org/covid19-residency-application/ Available at.

- 75.Gelwick B.P. Training faculty to do career advising. Person Guid J. 1974;53:214–216. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chang L.L., Nagler A., Rudd M. Is it a match? a novel method of evaluating medical school success. Med Educ Online. 2018;23:1432231. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2018.1432231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chakraborti C., Crowther J.E., Koretz Z.A., Kahn M.J. How well did our students match? A peer-validated quantitative assessment of medical school match success: the match quality score. Med Educ Online. 2019;24:1681068. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2019.1681068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]