Abstract

The coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic presents significant challenges for health systems globally, including substantive ethical dilemmas that may pose specific concerns in the context of care for people with kidney disease. Ethical concerns may arise as changes in policy and practice affect the ability of all health professionals to fulfill their ethical duties toward their patients in providing best practice care. In this article, we briefly describe such concerns and elaborate on issues of particular ethical complexity in kidney care: equitable access to dialysis during pandemic surges; balancing the risks and benefits of different kidney failure treatments, specifically with regard to suspending kidney transplantation programs and prioritizing home dialysis, and barriers to shared decision-making; and ensuring ethical practice when using unproven interventions. We present preliminary advice on how to approach these issues and recommend urgent efforts to develop resources that will support health professionals and patients in managing them.

Keywords: COVID-19, end-stage kidney disease, ethics, pandemic, resource allocation

Editor’s Note.

This is one of several articles we think you will find of interest that are part of our special issue of Kidney International addressing the challenges of dialysis and transplantation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Please also find additional material in our commentaries and letters to the editor sections. We hope these insights will help you in the daily care of your own patients.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic presents significant challenges for health systems globally, including substantive ethical dilemmas. The pandemic has profoundly affected delivery of essential health services, including care for patients with or at risk of kidney disease. Measures to reduce infection risk have changed the way care is delivered, creating potential difficulties for health professionals in fulfilling their ethical responsibilities toward individual patients, public health, and their own families (see Table 1 ).1, 2, 3, 4 For patients with kidney failure (KF), who are dependent for survival on access to kidney replacement therapy (KRT) in the form of transplantation or dialysis, some changes have high-stakes implications. In settings where access to care was already difficult, the disruption of COVID-19 has proven catastrophic for some patients.5 COVID-19 infection is associated with the development of nephropathy and acute kidney injury (AKI), increasing demand for dialysis during surge periods.6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Kidney transplant patients are more vulnerable to severe complications of COVID-19,11 and transplant and dialysis patients may be at higher risk of infection.11, 12, 13, 14 People with kidney disease and transplant recipients have a higher risk of death from COVID-19.15

Table 1.

Challenges fulfilling ethical duties in the context of changes in health care delivery

| Ethical duties | Challenges | Strategies |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; PPE, personal protective equipment.

Awareness of the effect of the pandemic on access to dialysis is growing,9 , 10 and professional societies have publicly called for action to address issues in kidney care during the pandemic.16 However, despite several publications offering ethical advice during the pandemic, most focus on long-standing ethical concerns in the context of pandemics, such as obligations of health care workers to provide care and the allocation of scarce resources, in particular personal protective equipment, ventilators, and antiviral medications.1 , 2 , 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 Consequently, specific considerations pertinent to KF care are neglected. In Table 1, we summarize several challenges that may arise as changes in policy and practice affect the ability of kidney health professionals to fulfill their ethical duties toward their patients in providing best practice care. These important issues deserve further elaboration; however, we focus on 3 priority issues of particular ethical complexity: equitable access to dialysis during pandemic surges; balancing the risks and benefits of different KF treatments, specifically with regard to suspending kidney transplantation programs and prioritizing home dialysis, and barriers to shared decision making (SDM); and ensuring ethical practice when using unproven interventions. We present preliminary advice on how to approach these issues and recommend urgent efforts to develop resources that will support health professionals and patients in managing them.

Equity of access to dialysis

Surges in dialysis demand have been reported during the pandemic as a result of COVID-19–related AKI; there may also be difficulties in meeting regular demand for dialysis as a result of disruption to domestic and international supply chains.5 , 6 , 26 , 27 For example, there may be staff shortages because of illness or isolation measures, people may be unable to travel safely to access dialysis during lockdown periods, medical products such as dialysate fluid may be unavailable because of transport delays or diversion of supplies to meet urgent needs elsewhere, and insufficient supplies of personal protective equipment may limit the ability of clinics to provide full services while meeting infection control standards.26 , 28 Home dialysis patients may face difficulties in accessing telemedicine, laboratory services, prescriptions, and delivery of dialysis supplies.29

Although some countries, especially low- and middle-income countries have experience with rationing of publicly funded dialysis,30 , 31 rationing of dialysis in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic may present unfamiliar challenges for many health systems. Notably, people with AKI requiring only temporary dialysis for survival may be unable to access this treatment if systems are overwhelmed. The pandemic may potentially exacerbate the need for rationing in any country and complicate existing ethical dilemmas regarding equity in the allocation of available resources. Some dialysis centers may be able to provide dialysis to only some of those in need, leading some patients to die who would otherwise survive. Other centers may need to compromise on the quality of care provided, for example, by reducing dialysis frequency or duration or by using modalities that are not the preferred or standard treatment for particular patients. Burgner et al. have outlined measures that may increase efficiency in managing dialysis resources and enable more people to receive treatment or survive without dialysis during periods of peak demand.32 Nevertheless, rationing of resources may be required for a period of weeks, and on a recurrent basis, necessitating long-term planning for equitable and efficient resource allocation.

When there are insufficient resources to meet all needs, and those resources are necessary to preserve life, several ethical principles and values are commonly used to guide the allocation of resources so as to avoid or minimize unfair inequalities (inequities)33 (see Table 2 ). In some situations several of these principles and values, taken in isolation, may produce the same conclusion. In practice, they are applied in variable combinations, informed by clinical evidence regarding the likely outcomes of particular allocation frameworks in specific populations, and, ideally, the values and preferences of those populations.

Table 2.

Principles and values guiding resource allocation decision-making in the context of KF care, with examples of their limitationsa

| Avoiding futility: ensuring resources are used only where they will provide a benefit. | Maximizing utility: allocating resources to produce the greatest benefits overall for a given population. |

|---|---|

|

|

| Reciprocity and solidarity: helping those who are necessary for the provision of care and/or who contribute to the common good. | “Fair innings”: focus on allowing all people to live a “normal” life span. |

|---|---|

|

|

| Prioritarianism: providing first for the worst off. | Equality: respecting fundamental right to health.b |

|---|---|

|

|

AKI, acute kidney injury; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; KF, kidney failure; ICU, intensive care unit.

These highlight the need for use of allocation frameworks that engage with a range of considerations pertinent to distributive justice.

Notably may be interpreted as promoting equality of health outcomes, opportunities to access care, or shares of resources.

Like mechanical ventilation, dialysis is a life-sustaining treatment. Unlike ventilators, which are rarely used as long-term treatment of chronic end-stage organ failure, dialysis is used in the chronic treatment of >2 million people worldwide.34 Dialysis machines are also routinely used to provide life-sustaining treatment to several individuals in a given time period, whereas in the same period a ventilator may be used by only 1 person. However, continuous KRT is often required in critically ill patients with COVID-19–related AKI,35 making this treatment, like mechanical ventilation, a rival good—use by one patient may exclude others who could die as a result. Ethical guidelines designed to support the allocation of resources such as ventilators have received considerable attention from ethicists and politicians20; however, they may not be well suited to allocation of dialysis resources.36

Although some patients may be completely excluded from dialysis as a consequence of rationing during pandemic surges in resource-limited settings, rationing of dialysis that entails compromises in the quality of care provided is likely to be a more widespread challenge for health care providers (including health professionals and institutions) and patients in many countries. Guidelines are thus needed to ensure that when compromises are necessary and unavoidable, they are fairly distributed and hence equitable. In the early phase of the pandemic, as resource capacities fluctuate and evidence to inform clinical decision-making slowly emerges, key strategies to optimize utility and promote equity in the allocation of limited dialysis resources include the following:

-

(i)

expand capacity and explore options to reduce demand for chronic dialysis where possible32;

-

(ii)

use alternative dialysis modalities for which capacity is more readily expanded (e.g., acute start peritoneal dialysis) when possible27 , 35 , 37;

-

(iii)

use transparent clinical criteria to inform decision-making based on the best available current evidence38; and

-

(iv)

engage in advance care planning with patients, exploring their preferences with regard to treatment options if they develop COVID-19 and require intensive care unit admission and/or dialysis.39 Determining treatment limits in advance may help avoid futile treatment.40

The development of guidelines to support decision-making for the allocation of dialysis resources should be prioritized as part of long-term planning in response to the pandemic in all countries,41 with consideration for the local context and respect for the values and preferences of local stakeholders. Use of well-designed guidelines and decision-making tools that are supported by stakeholders—including patients—are likely to improve impartiality in decision-making and reduce the psychological burdens of rationing on clinicians, including moral distress.42 Procedural justice must be respected, with transparent communication of policies and guidelines, systematic monitoring and review of outcomes, and clear, accessible processes to support accountability.

Rethinking decision-making about KF treatment modalities

Efforts to reduce demand for KRT and avoid rationing, and to protect patients with KF and staff from COVID-19 infection, may influence decision-making about KF treatment modalities and potentially affect quality of patient care. The effect of COVID-19 is expected to persist for some years. Infection precautions such as use of personal protective equipment for high-risk procedures are likely to continue even if vaccines and successful treatments are developed. This will affect not only the financial cost of treatment of KF, threatening the viability of some services and increasing barriers to care for many patients, but also the risks and benefits associated with particular treatment modalities and the complexities of clinical decision-making for both patients and health care providers. Ethical values and principles that are commonly used to guide decision-makers in the clinical setting such as respect for patient autonomy, nonmaleficence, beneficence, and justice still prevail; however, the context in which decisions are made has changed significantly. Preparedness for managing these changes in clinical practice must include consideration of the ethical implications for decision-making, which we briefly explore below.

SDM

It is essential that patients, and their carers or substitute decision-makers when relevant, are actively engaged in decision-making about treatment options, as they are usually best placed to determine which option will accord with their personal values and preferences, in light of their individual circumstances. Inclusion of patients in decision-making about policy is also vital, enabling decisions to be informed by an understanding of patient experiences and perspectives and respecting the autonomy of those who will be most affected by the decisions made. Patients should also be involved in decision-making about—and informed of—rationing of health resources when relevant to promote transparency and accountability of resource allocation decisions.42

SDM involves a collaborative approach in which clinicians and patients (or their substitute decision-makers) work together to make decisions about care that are based on relevant clinical information and the patient’s interests, values, and preferences. In the clinical setting, there may be several practical barriers to SDM during the pandemic as a result of, for example, reliance on telemedicine or physical distancing measures in clinics.43 These may raise ethical concerns about respect for patient autonomy and complicate efforts to determine the best interests of patients who lack decision-making capacity.44 For example, if a patient who communicates nonverbally is hospitalized and COVID-19 protections prevent the attendance of their usual carers, video calls may be ineffective in enabling carers to ascertain the views and preferences of that patient through visual cues. The additional burdens of decision-making for patients and their families as outlined below may result in increased reliance on clinicians to advise on treatment decisions. Clinicians may have less information than they ordinarily would regarding the potential risks and benefits of treatment choices and are thus likely to experience significant ethical anxiety when implementing these decisions or supporting patients to make treatment choices. Uncertainty regarding the potential risks and benefits of options makes it difficult for clinicians to know how best to fulfill their obligations to promote patient well-being (beneficence) and avoid causing harm, ensuring that unavoidable harms are proportionate to the expected benefits of decisions taken (nonmaleficence). Those who feel unable to fulfill their obligations, for example, as a consequence of resource constraints or policies enforcing restrictions on availability of treatments, may experience moral distress.

Fortunately, efforts to reduce risks associated with particular treatment modalities are increasingly informed by guidelines, and uncertainty may be reduced by the growing evidence base in the COVID-19 literature.12 Use of patient and clinician decision aids, which comprise various structured tools designed to support evidence-based and deliberative decision-making, may help manage decision-making difficulties and promote the dialogue necessary for effective SDM.43 , 45 , 46 Effective staff training and support for SDM, tailored to the new clinical realities of the pandemic era, will be essential to ensure that any decision-making aids are used effectively. Clinicians will need to cautiously and critically evaluate evidence from experiences in different countries or health system contexts for application in their local setting and may benefit from additional training in risk communication and SDM with patients (see Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Summary of recommendations for ESKD treatment modality decision-making

| Transparency and reassurance | Critical analysis |

|---|---|

|

|

| Shared decision-making | Management of risk and moral distress |

|---|---|

|

|

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease; PPE, personal protective equipment.

Kidney transplantation

Kidney transplant programs were paused or activity was restricted in many countries as the pandemic developed. This was due to fears of increasing the pool of vulnerable transplant recipients who face significant risks from COVID-19 infection—in particular those admitted for surgery or receiving organs from deceased donors who might be infected—and concerns that performing surgery that might result in the need for intensive care unit admission could use scarce resources at a time of increasing demand.47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52 In some contexts, insufficiency of intensive care unit resources may have also limited deceased donation activity because of limitations in capacity to provide maintenance care of prospective deceased donors before retrieval of organs. In contrast to kidney transplant programs, some heart, lung, and liver transplants have been permitted on the grounds of lifesaving necessity.47, 48, 49 However, for some patients, such as those in low- and middle-income countries for whom ongoing dialysis may be unavailable, inaccessible, or unfeasible because of the lack of availability or financial costs, the inability to obtain a timely living donor kidney transplant may be fatal.

Decisions to institute moratoria or reduce transplant activity were made in response to a rapidly developing crisis with limited consideration of longer-term consequences and how these may be managed. The temporary suspension will exacerbate the long-standing shortage of deceased donor kidneys, place increased pressure on systems to fulfill demand once transplant activity resumes, and prevent preemptive transplantation, thus increasing demand for dialysis for those patients who would otherwise have received a transplant. For some, delays could eliminate the opportunity for transplantation altogether. Furthermore, continued reliance on dialysis may expose patients with KF to higher risks of COVID-19 infection over time because of limitations on social distancing when accessing dialysis (outpatient hemodialysis) and/or obtaining dialysis resources or receiving care at home. Hence, efforts to prevent harm to some patients may create or exacerbate inequities in access to transplantation or dialysis or in exposure to the risk of COVID-19 infection.

As health systems establish some control over the spread of COVID-19 and the management of health care resources, transplant professionals and policymakers are now determining when and how to recommence or scale-up kidney transplantation.50 A gradual reopening of programs is likely to occur where nonrenal surgical capacity permits, with prioritization of low-risk cases in centers with effective systems and resources to manage infection risks. Stakeholders will have to contend with several challenging decisions involving evaluation of risks and benefits in the context of considerable uncertainty. Determining when to proceed with donation and/or transplantation has always involved efforts to ensure expected benefits are proportionate to potential risks. In the pandemic era, customary risk-benefit analyses will be further complicated by consideration of patients’ risk of contracting COVID-19 infection and the associated risks that may be linked to specific treatment modalities. Patients’, physicians’, and surgeons’ perceptions of risk, which may be influenced by media coverage and research reporting experiences in other countries, will also be a complicating factor in decision-making.

Kidney transplant recipients have a comparatively high risk of COVID-19 infection and mortality.15 , 53, 54, 55 Dialysis patients, particularly those attending outpatient dialysis clinics, are also at higher risk as a result of greatly increased contact with health care systems and hence exposure to potential infection.13 They are also likely to be at higher risk of serious complications and death as a result of older age and comorbidities.13 , 56 Patients contemplating transplantation must consider the possible effect of future pandemic developments in the context of their own health system and individual circumstances. For example, if a surge in infections occurs shortly after a transplant, the patient’s risk of life-threatening infection may increase. For those who defer transplantation, a surge might limit dialysis availability; thus, concerns about infection risks will intersect with concerns about the availability of essential health resources and the potential effect of rationing measures on access to all treatments.

Dialysis treatment

For new patients with KF, the possibility of delaying commencement of KRT may be considered to reduce demand and protect patients from the risks of infection associated with either transplantation or dialysis. However, rather than postponing dialysis, physicians in some countries have been urged to consider whether new incident patients might be suitable for at-home dialysis.57 Established patients may also be encouraged to change to home hemodialysis and/or peritoneal dialysis where this is an option so as to reduce pressure on hemodialysis clinics and facilitate social distancing. The benefits of this approach must be weighed against the potential burdens and risks for patients. For example, it may not be possible to provide the customary level of support to patients commencing home hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis, leaving patients and their carers anxious or ill-equipped to manage and thus at higher risk of complications. However, these concerns may be reduced by use of remote monitoring.58 Suspension of “nonessential” surgery has also restricted options for creation of dialysis access, resulting, for example, in continued reliance on catheters rather than the safer and more reliable arteriovenous fistulae.

When evaluating the potential burdens and infection risks associated with various treatment modalities, clinicians must consider not only patients with KF but also their personal carers. Those close to dialysis patients often play a significant role in their care, for example, by providing transport to clinics or assisting in dialysis at home.59 Dependence on carers may increase during the pandemic because of the disruption of patient transport systems or supply chains or reduced availability of professional care. Carers may therefore be more exposed to the risk of infection.

Conservative care

Conservative kidney management without dialysis should always be considered as a treatment pathway for KF.60 Given the increased risks now associated with various forms of KRT, the balance of risks and benefits may shift in favor of conservative kidney management without dialysis for some patients whether as a temporary deferral or a choice not to initiate dialysis at all. However, it is important to ensure that decisions about initiating dialysis in people approaching KF or discontinuing dialysis in those already receiving it are not unconsciously influenced by rationing considerations; for example, information on treatment options should not be withheld from patients because a clinician believes that rationing may be required. Where rationing is necessary, this should be addressed explicitly and separately from decisions about what would be best for individual patients; rationing decisions should be made at the clinic, hospital, or government level to avoid situations in which clinicians may engage in ad hoc implicit bedside rationing, which may notably conflict with their duties of fidelity toward patients. Routine use of allocation guidelines to support clinical decision-making may help reduce moral distress and promote transparency, accountability, and consistent application of policy.61 , 62

Ethical implications of unproven and innovative interventions for the treatment of COVID-19

There are growing ethical concerns about the use of experimental treatments for COVID-19 infection that are of unproven benefit and potentially significant risks and regarding the conduct of research in this field.63, 64, 65 Rapid communication of preliminary or incomplete trial results via media releases and journal publications has influenced practice in several countries, created confusion, and also undermined confidence in the peer review process, as evidenced by widespread controversy regarding the use of hydroxychloroquine as treatment of COVID-19.66 , 67 Kidney health professionals may be involved in clinical trials of novel interventions, which are more likely to be tested in patients with COVID-19 with more severe infection, who are at high risk of AKI.7 , 8 Clinicians may also need to advocate for inclusion of patients with KF in clinical trials to ensure new therapies are suitable for use in a population at high risk of COVID-19–related morbidity and mortality.68 When standard kidney therapies are unavailable or rationed as a result of the pandemic, clinicians may also consider innovative changes in standard practice in the care of people with kidney disease without COVID-19, including deviations from routine dialysis protocols or procedures, or changes in immunosuppression regimens for transplant recipients.69

Ethical principles governing clinical research are equally relevant during public health crises; however, pandemic circumstances may complicate standard procedures of ethical review and the potential risks and benefits of conducting research may result in practices not normally considered justifiable. The World Health Organization provides general ethical guidance for research during the pandemic70; however, there is little guidance as yet available for the use of interventions that are unproven in the treatment of COVID-19 infection but that are established therapies for other conditions, which have accordingly been fast-tracked for use in the pandemic. The so-called “off-label” use of existing therapies or changes in established practices including cessation of standard therapies such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors for the management of hypertension or kidney disease carry significant risks as clinicians may independently prescribe or withhold interventions without the oversight and patient protections normally afforded in clinical trials.71 , 72

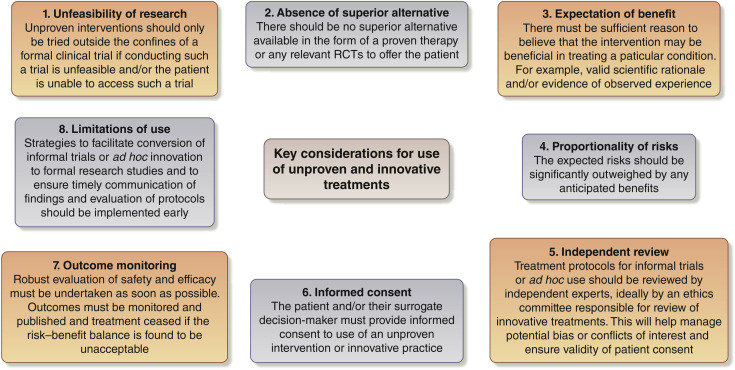

Use of unproven interventions or trial of innovative diagnostics, medicines, or surgery outside a formal research study may be considered ethically justified under certain conditions.73, 74, 75 Key considerations are outlined in Figure 1 . Clinicians may feel pressure to offer unproven interventions to patients as a result of optimistic media coverage, particularly when supported by politicians or celebrities. Regulators may also feel pressure to approve some interventions.76 Patients and/or their surrogate decision-makers may request treatments and, given significant known risks of COVID-19, clinicians may feel compelled to provide an unproven intervention in the absence of alternatives—so-called compassionate use.77 Ethical decision-making regarding the use of unproven interventions or even participation in a formal trial may be complicated if the patient has a high risk of mortality from the infection, such as transplant recipients and those on dialysis, and if the patient currently lacks decision-making capacity. Regardless of these difficulties, clinicians should work to build the evidence base through randomized trials.

Figure 1.

Key considerations for the use of unproven and innovative treatments. RCT, randomized controlled trial.

In the face of uncertainty relating to the clinical course of COVID-19 infection and the potential risks or benefits of novel interventions or off-label treatments, clinicians should uphold their customary ethical duties toward patients and communities. Respecting autonomy by ensuring that patients or their surrogates are informed of treatment options, and of the limitations of knowledge when relevant, and that valid consent is obtained for all treatments is essential. The imperative to avoid delays in provision of beneficial treatments to large numbers of patients with severe illness may conflict with efforts to generate data from robust clinical trials that are likely, over time, to substantially benefit many people.78 Clinicians should recognize that the obligation of beneficence does not entail the reckless pursuit of unproven interventions that may cause harm to patients and the wider community. Failure to uphold professional standards of evidence-based practice and ethical conduct of research, for example, may undermine public trust in health care systems at a time when trust may be essential for the effective implementation of public health measures to address the pandemic.

Conclusion

This article identifies a number of complex ethical issues with specific implications for kidney health care during the COVID-19 pandemic: concerns about equity in the allocation of limited resources, complex treatment decisions in the context of clinical uncertainty regarding risks and benefits of treatment modalities, and the use of unproven interventions for the treatment of COVID-19 or innovative practices for KF care. The ethical challenges that have emerged or been exacerbated during the pandemic are likely to persist for several years because of the long-term effect of changes in health care practice, economies, and social norms. Considerable work is still needed to explore these issues in greater depth and to develop guidelines and tools to support ethical decision-making in the local context.

Disclosure

FJC has received honoraria from Baxter and research funding from the National Institute for Health Research and Kidney Care UK. VJ has received research funding from Glaxo-Smith-Kline, Baxter Healthcare, and Biocon and honoraria from NephroPlus and Zydus Cadila, with the policy of all honoraria being paid to the organization. All the other authors declared no competing interests. All the other authors declared no competing interests.

References

- 1.Bakewell F., Pauls M.A., Migneault D. Ethical considerations of the duty to care and physician safety in the COVID-19 pandemic. CJEM. 2020;22:407–410. doi: 10.1017/cem.2020.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Binkley C.E., Kemp D.S. Ethical rationing of personal protective equipment to minimize moral residue during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Surgeons. 2020;230:1111–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kliger A.S., Silberzweig J. Mitigating risk of COVID-19 in dialysis facilities. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15:707–709. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03340320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ying NL, Kin W, Han LC, et al. Rapid transition to a telemedicine service at Singapore community dialysis centers during Covid-19 [e-pub ahead of print]. NEJM Catal Innov Care Deliv. https://doi.org/10.1056/CAT.20.0145. Accessed August 23, 2020.

- 5.Ramachandran R., Jha V. Adding insult to injury: kidney replacement therapy during COVID-19 in India. Kidney Int. 2020;98:238–239. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldfarb D.S., Benstein J.A., Zhdanova O. Impending shortages of kidney replacement therapy for COVID-19 patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15:880–882. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05180420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perico L., Benigni A., Remuzzi G. Should COVID-19 concern nephrologists? Why and to what extent? The emerging impasse of angiotensin blockade. Nephron. 2020;144:213–221. doi: 10.1159/000507305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naicker S., Yang C.W., Hwang S.J. The novel coronavirus 2019 epidemic and kidneys. Kidney Int. 2020;97:824–828. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kulish N. A life and death battle: 4 days of kidney failure but no dialysis. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/01/health/coronavirus-dialysis-death.html Available at:

- 10.Abelson R., Fink S., Kulish N., Thomas K. An overlooked, possibly fatal coronavirus crisis: a dire need for kidney dialysis. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/18/health/kidney-dialysis-coronavirus.html Available at:

- 11.Gandolfini I., Delsante M., Fiaccadori E. COVID-19 in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2020;20:1941–1943. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ikizler T.A., Kliger A.S. Minimizing the risk of COVID-19 among patients on dialysis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16:311–313. doi: 10.1038/s41581-020-0280-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kliger A.S., Cozzolino M., Jha V. Managing the COVID-19 pandemic: international comparisons in dialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2020;98:12–16. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trujillo H., Caravaca-Fontán F., Sevillano Á. SARS-CoV-2 infection in hospitalized patients with kidney disease. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5:905–909. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2020.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The OpenSAFELY Collaborative, Williamson E, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran KJ, et al. OpenSAFELY: factors associated with COVID-19-related hospital death in the linked electronic health records of 17 million adult NHS patients [e-pub ahead of print]. medRxiv.https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.06.20092999. Accessed August 23, 2020.

- 16.American Society of Nephrology, European Renal Association-European Dialysis and Transplant Association, International Society of Nephrology Ensuring optimal care for people with kidney diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.kidneynews.org/sites/default/files/Statement%20ASN%20ERA%20EDTA%20ISN%204.28.20.pdf Available at:

- 17.Robert R., Kentish-Barnes N., Boyer A. Ethical dilemmas due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10:84. doi: 10.1186/s13613-020-00702-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McQuoid-Mason D.J. COVID-19: may healthcare practitioners ethically and legally refuse to work at hospitals and health establishments where frontline employees are not provided with personal protective equipment? S Afr J Bioeth Law. 2020;13:16–19. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dunn M., Sheehan M., Hordern J. ‘Your country needs you’: the ethics of allocating staff to high-risk clinical roles in the management of patients with COVID-19. J Med Ethics. 2020;46:436–440. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2020-106284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Emanuel E.J., Persad G., Upshur R. Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2049–2055. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb2005114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jessop Z.M., Dobbs T.D., Ali S.R. Personal protective equipment (PPE) for surgeons during COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review of availability, usage, and rationing. Br J Surg. 2020;107:1262–1280. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.White D.B., Lo B. A framework for rationing ventilators and critical care beds during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;323:1773–1774. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim S., DeBruin D.A., Leider J.P. Developing an ethics framework for allocating remdesivir in the COVID-19 pandemic. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95:1946–1954. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White D.B., Angus D.C. A proposed lottery system to allocate scarce COVID-19 medications: promoting fairness and generating knowledge. JAMA. 2020;324:329–330. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.11464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeJong C., Chen A.H., Lo B. An ethical framework for allocating scarce inpatient medications for COVID-19 in the US. JAMA. 2020;323:2367–2368. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prasad N., Agarwal S.K., Kohli H.S. The adverse effect of COVID pandemic on the care of patients with kidney diseases in India. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5:1545–1550. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2020.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sourial M.Y., Sourial M.H., Dalsan R. Urgent peritoneal dialysis in patients with COVID-19 and acute kidney injury: a single-center experience in a time of crisis in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;76:401–406. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fisher M., Prudhvi K., Brogan M., Golestaneh L. Providing care to patients with AKI and COVID-19 infection: experience of front line nephrologists in New York. Kidney360. 2020;1:544–548. doi: 10.34067/KID.0002002020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yerram P, Misra M. Home dialysis in the coronavirus disease 2019 era [e-pub ahead of print]. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis.https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ackd.2020.07.001. Accessed August 28, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Luyckx V.A., Smyth B., Harris D.C.H. Dialysis funding, eligibility, procurement, and protocols in low- and middle-income settings: results from the International Society of Nephrology collection survey. Kidney Int Suppl. 2020;10:e10–e18. doi: 10.1016/j.kisu.2019.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Flood D., Wilcox K., Ferro A.A. Challenges in the provision of kidney care at the largest public nephrology center in Guatemala: a qualitative study with health professionals. BMC Nephrol. 2020:21. doi: 10.1186/s12882-020-01732-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burgner A., Ikizler T.A., Dwyer J.P. COVID-19 and the inpatient dialysis unit: managing resources during contingency planning pre-crisis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15:720–722. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03750320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Persad G., Wertheimer A., Emanuel E.J. Principles for allocation of scarce medical interventions. Lancet. 2009;373:423–431. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liyanage T., Ninomiya T., Jha V. Worldwide access to treatment for end-stage kidney disease: a systematic review. Lancet. 2015;385:1975–1982. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61601-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chua H.R., MacLaren G., Choong L.H. Ensuring sustainability of continuous kidney replacement therapy in the face of extraordinary demand: lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;76:392–400. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parsons J.A., Martin D.E. A call for dialysis-specific resource allocation guidelines during COVID-19. Am J Bioeth. 2020;20:199–201. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2020.1777346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.El Shamy O., Patel N., Abdelbaset M.H. Acute start peritoneal dialysis during the COVID-19 pandemic: outcomes and experiences. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31:1680–1682. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020050599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin D.E., Harris D.C., Jha V. Ethical challenges in nephrology: a call for action. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16:603–613. doi: 10.1038/s41581-020-0295-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu E. Communication strategies for kidney disease in the time of COVID-19. J Palliat Med. 2020;23:757–758. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2020.0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Curtis J.R., Kross E.K., Stapleton R.D. The importance of addressing advance care planning and decisions about do-not-resuscitate orders during novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA. 2020;323:1771–1772. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silberzweig J., Ikizler T.A., Kramer H. Rationing scarce resources: the potential impact of COVID-19 on patients with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31:1926–1928. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020050704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ducharlet K., Philip J., Gock H. Moral distress in nephrology: perceived barriers to ethical clinical care. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;76:248–254. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abrams E.M., Shaker M., Oppenheimer J. The challenges and opportunities for shared decision making highlighted by COVID-19. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:2474–2480.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parsons J.A., Johal H.K. Best interests versus resource allocation: could COVID-19 cloud decision-making for the cognitively impaired? J Med Ethics. 2020;46:447–450. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2020-106323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Greenhalgh T., Howick J., Maskrey N. Evidence based medicine: a movement in crisis? BMJ. 2014;13:348. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stacey D., Légaré F., Lewis K. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kumar D., Manuel O., Natori Y. COVID-19: a global transplant perspective on successfully navigating a pandemic. Am J Transplant. 2020;20:1773–1779. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and supply of substances of human origin in the EU/EEA. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/covid-19-supply-substances-human-origin.pdf Available at:

- 49.Australian Health Protection Principal Committee Statement on organ donation and transplantation during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.health.gov.au/news/australian-health-protection-principal-committee-ahppc-coronavirus-covid-19-statements-on-7-april-2020#statement-on-organ-donation-and-transplantation-during-the-covid19-pandemic Available at:

- 50.National Health Service Blood and Transplant KAG guidance for re-opening or expansion of kidney transplant programs and COVID-19. https://nhsbtdbe.blob.core.windows.net/umbraco-assets-corp/18469/kag-guidance-for-re-opening-or-expansion-of-kidney-transplant-programs-and-covid-19.pdf Available at:

- 51.American Society of Transplant Surgeons ASTS COVID 19 Strike Force guidance to members on the evolving pandemic. https://asts.org/advocacy/covid-19-resources/asts-covid-19-strike-force/asts-covid-19-strike-force-initial-guidance#.XrUOCi1L3BI Available at:

- 52.National Health Service Blood and Transplant POL296/1—re-opening of transplant programmes: issues for consideration. https://nhsbtdbe.blob.core.windows.net/umbraco-assets-corp/18436/pol296.pdf Available at:

- 53.Akalin E., Azzi Y., Bartash R. Covid-19 and kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2475–2477. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2011117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Banerjee D., Popoola J., Shah S. COVID-19 infection in kidney transplant recipients. Kidney Int. 2020;97:1076–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alberici F., Delbarba E., Manenti C. A single center observational study of the clinical characteristics and short-term outcome of 20 kidney transplant patients admitted for SARS-CoV2 pneumonia. Kidney Int. 2020;97:1083–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ng J.H., Hirsch J.S., Wanchoo R. Outcomes of patients with end-stage kidney disease hospitalized with COVID-19. Kidney Int. 2020;98:1530–1539. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence COVID-19 rapid guideline: dialysis service delivery. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng160 Available at: [PubMed]

- 58.Srivatana V., Liu F., Levine D.M., Kalloo S.D. Early use of telehealth in home dialysis during the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City. Kidney360. 2020;1:524–526. doi: 10.34067/KID.0001662020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hoang V.L., Green T., Bonner A. Informal caregivers’ experiences of caring for people receiving dialysis: a mixed-methods systematic review. J Ren Care. 2018;44:82–95. doi: 10.1111/jorc.12235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hole B., Hemmelgarn B., Brown E. Supportive care for end-stage kidney disease: an integral part of kidney services across a range of income settings around the world. Kidney Int Suppl. 2020;10:e86–e94. doi: 10.1016/j.kisu.2019.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Close E., White B.P., Willmott L. Doctors’ perceptions of how resource limitations relate to futility in end-of-life decision making: a qualitative analysis. J Med Ethics. 2019;45:373–379. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2018-105199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Scheunemann L.P., White D.B. The ethics and reality of rationing in medicine. Chest. 2011;140:1625–1632. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Baud D., Qi X., Nielsen-Saines K. Real estimates of mortality following COVID-19 infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:773. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30195-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kalil A.C. Treating COVID-19—off-label drug use, compassionate use, and randomized clinical trials during pandemics. JAMA. 2020;323:1897–1898. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zagury-Orly I., Schwartzstein R.M. Covid-19—a reminder to reason. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:e12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2009405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kim A.H., Sparks J.A., Liew J.W. A rush to judgment? Rapid reporting and dissemination of results and its consequences regarding the use of hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:819–821. doi: 10.7326/M20-1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mahase E. Hydroxychloroquine for covid-19: the end of the line? BMJ. 2020;369:m2378. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.International Society of Nephrology International Society of Nephrology –Advancing Clinical Trials (ISN-ACT) statement on trials and COVID-19. https://www.theisn.org/images/ISN-ACT-Statement-on-Trials-and-COVID-19-Final.pdf Available at:

- 69.Bomback A.S., Canetta P.A., Ahn W. How COVID-19 has changed the management of glomerular diseases. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15:876–879. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04530420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.World Health Organization Ethical standards for research during public health emergencies: distilling existing guidance to support COVID-19 R&D. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331507/WHO-RFH-20.1-eng.pdf Available at:

- 71.DeJong C., Wachter R.M. The risks of prescribing hydroxychloroquine for treatment of COVID-19—first, do no harm. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:1118–1119. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vaduganathan M., Vardeny O., Michel T. Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors in patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1653–1659. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr2005760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Samanta J., Samanta A. Quackery or quality: the ethicolegal basis for a legislative framework for medical innovation. J Med Ethics. 2015;41:474–477. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2014-102366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McCulloch P., Altman D.G., Campbell W.B. No surgical innovation without evaluation: the IDEAL recommendations. Lancet. 2009;374:1105–1112. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Earl J. Innovative practice, clinical research, and the ethical advancement of medicine. Am J Bioeth. 2019;19:7–18. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2019.1602175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ferner R.E., Aronson J.K. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in covid-19. BMJ. 2020;369:m1432. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Borysowski J., Ehni H.J., Górski A. Ethics review in compassionate use. BMC Med. 2017;15:136. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0910-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wise J., Coombes R. Covid-19: the inside story of the RECOVERY trial. BMJ. 2020;370:m2670. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]