Abstract

In social contexts, people’s emotional expressions may disguise their true feelings but still be revealing about the probable desires of their intended audience. This study investigates whether children can use emotional expressions in social contexts to recover the desires of the person observing, rather than displaying the emotion. Children (7.0–10.9 years, N = 211 across five experiments) saw a protagonist express one emotional expression in front of her social partner, and a different expression behind her partner’s back. Although the protagonist expressed contradictory emotions (and the partner expressed none), even 7‐year‐olds inferred both the protagonist’s and social partner’s desires. These results suggest that children can recover not only the desire of the person displaying emotion but also of the person observing it.

People sometimes go to great lengths to disguise their true feelings. Defeated political candidates offer gracious concessions to despised opponents, nervous keynote speakers act calm and collected, and polite recipients of a gift gush even when they are disappointed. However, an often‐overlooked aspect of emotion regulation in social contexts is that while masked emotional expressions can be misleading about the true mental states of the person expressing the emotion, they may be revealing about what the person thinks about the probable mental states of her intended audience. When for instance, someone congratulates a friend in public but fumes in private, we might infer not only that this person’s true feelings about the event are negative but also that her friend’s feelings are positive. Thus, an astute observer who sees someone’s emotional expressions in both social and nonsocial contexts might be able to recover not only the individual’s true feelings, but also the probable desires of the person she is addressing.

This kind of inference is nontrivial: it requires tracking someone’s emotional expressions across contexts, figuring out the reason for her changing her emotional expressions, and inferring the likely mental state of a conversational partner whose expressions may not be observed at all. However, as children progress into middle childhood, this kind of sophisticated emotion understanding may be especially important. Studies suggest that children’s theory of mind overall, and their ability to understand emotion in particular, is correlated with the quality of peer relationships in early elementary school (Caputi, Lecce, Pagnin, & Banerjee, 2012; Cassidy, Parke, Butkovsky, & Braungart, 1992; Denham, McKinley, Couchoud, & Holt, 1990; Izard et al., 2001; Mostow, Izard, Fine, & Trentacosta, 2002); in light of this, influential interventions (e.g., the PATHS curriculum) have been designed to target emotion understanding in 7‐ to 9‐year‐olds (Greenberg, Kusche, Cook, & Quamma, 1995).

Critically, however, this kind of inference is the inverse of the kind of reasoning that has been the focus of most work on theory of mind. The vast majority of studies have investigated not children’s ability to infer others’ beliefs and desires given their emotional expressions and the context, but rather children’s ability to predict others’ actions and emotional reactions from knowledge of their beliefs and desires (see Wellman, 2014, for review). For instance, we know that toddlers (Stein & Levine, 1989; Wellman & Woolley, 1990) and even infants (Skerry & Spelke, 2014) expect agents to be happy when they get what they want, and sad if they do not. Four‐ and 5‐year‐olds predict that someone will be surprised if her expectations are violated, and happy if she falsely believes her actions will achieve a goal (Hadwin & Perner, 1991; MacLaren & Olson, 1993; Ruffman & Keenan, 1996; Wellman & Banerjee, 1991).

However, because beliefs and desires are intrinsically hidden, the challenge is often not to predict how someone will feel given an understanding of their other mental states but to use the emotions she expresses to recover what she most likely thinks and wants. The few studies that have focused on these inverse inferences suggest that toddlers can use positively or negatively valenced expressions to infer others’ preferences (Repacholi & Gopnik, 1997; Wellman, Phillips, & Rodriguez, 2000) and that preschoolers can connect others’ emotions to familiar eliciting causes (e.g., explaining that someone is scared because she saw a ghost, or surprised if she saw something unexpected; Rieffe, Terwogt, & Cowan, 2005; Wellman & Banerjee, 1991). By five, children can go beyond canonical relations between emotions and events, to infer false beliefs about novel events from a change of valence in someone’s emotional expressions before and after she knows the outcome of an event (Wu & Schulz, 2018). Children can also use someone’s emotional expression to recover her knowledge and predict her subsequent behavior in classic Sally‐Anne Tasks (Wu, Haque, & Schulz, 2018). For instance, if children are not told whether Sally saw Anne move her toy or not but are shown Sally’s emotional expression when she returns, they can infer from the valence of the expression whether Sally saw the transfer and thus where she will look (i.e., if Sally looks angry, children infer that Sally saw Anne move her toy and thus will look for the toy in the new location). However, the extent to which children can use emotional expressions to recover otherwise unknown information about others’ mental states remains unclear.

Moreover, the previous work has focused on emotions expressed by an individual reacting to an event on her own. However, emotions are frequently expressed in interpersonal contexts and serve communicative goals (see Shariff & Tracy, 2011 for review). Because a wide range of display rules govern how we ought to express our emotions in front of others, understanding others’ emotional expressions in social contexts may be a particularly challenging task. Consistent with this, studies suggest that children’s understanding of social display rules undergoes substantial development between early and middle childhood (Banerjee, 1997; Banerjee & Yuill, 1999; Broomfield, Robinson, & Robinson, 2002; Gnepp & Hess, 1986; Heyman, Sweet, & Lee, 2009; Naito & Seki, 2009; Pons, Harris, & de Rosnay, 2004; Popliger, Talwar, & Crossman, 2011; Warneken & Orlins, 2015; Xu, Bao, Fu, Talwar, & Lee, 2010).

Thus, although preschoolers recognize that people may sometimes express feelings that they do not actually have (e.g., happiness on receiving a disappointing gift; Banerjee, 1997; Misailidi, 2006), 4‐ to 6‐year‐olds, unlike older children, frequently fail to predict that people will mask their true feelings, even when honest responses could hurt others’ feelings (Broomfield et al., 2002). Between four and ten, children become increasingly likely to judge that white lies are permissible (Heyman et al., 2009), to tell white lies themselves (Fu & Lee, 2007; Xu et al., 2010), and to consider the conditions under which lying is most appropriate. For instance, 7‐year‐olds, but not 5‐year‐olds, will selectively tell an artist that her bad drawing is a good one if the artist looks sad but not if her expression is neutral (Warneken & Orlins, 2015). With development, children also become increasingly likely to explain their adherence to social display rules by referring to embedded perspectives (e.g., explaining that a child will pretend to like the gift “so the uncle doesn’t feel sad …”). Consistent with this, success on social display tasks is related to second‐order theory of mind in 8‐year‐olds but not younger children (Naito & Seki, 2009).

The interpretation of the developmental findings is slightly complicated by the fact that studies involving the youngest children (preschoolers) typically provide very rich contextual information (Banerjee, 1997; Gross & Harris, 1988; Harris, Donnelly, Guz, & Pitt‐Watson, 1986; Josephs, 1994; Misailidi, 2006; Naito & Seki, 2009; Wellman & Liu, 2004). For example, in Banerjee’s (1997) study, children between ages three and five were read stories including an eliciting event (e.g., “Michelle is sleeping over at her cousin’s house but she forgot her favorite teddy bear at home”), an agent’s mental state (i.e., “Michelle is really sad that she forgot her teddy bear”), the agent’s intention to hide her true feeling (i.e., “Michelle doesn’t want her cousin to see how sad she is”), and a reason for hiding that feeling (i.e., “because her cousin will call her a baby”). Children were then asked about what the agent really feels and what expression she will display on her face. In such contexts, even 3‐year‐olds successfully identify both the real emotion and the facial expression she will exhibit but their success may depend heavily on the detailed contextual information available in the stories.

Studies using less informative contexts have found that an understanding of social display rules emerges much later (Broomfield et al., 2002; Gnepp & Hess, 1986; Jones, Abbey, & Cumberland, 1998). For instance, Gnepp and Hess (1986) provided children between ages 6 and 15 years old with an eliciting event and an agent’s mental state but did not explicitly mention the agent’s intention to hide her feelings nor any reason for her doing so. Nearly half of the children between ages 6 and 8 years failed to use verbal display rules. Even the oldest age group (who were 15 years old and successfully predicted the use of verbal display rules) frequently failed to predict that the agents would try to regulate their facial expressions. However, with less information in the stories, there is more uncertainty about whether the protagonist intended to be polite or not; given this uncertainty, children may have preferred to report the emotional expression that directly mapped onto the protagonist’s true mental state. Thus, there remains some ambiguity about what children understand, and when, about social display rules. Rich detailed scenarios may overestimate children’s ability, whereas ambiguous scenarios may be open to interpretations that do not involve social display rules at all.

Here we focus on 7‐ to 10‐year‐olds, influenced by the fact that the majority of work suggests that children are sensitive to social display rules by middle childhood. In particular, researchers (Pons et al., 2004) have proposed that emotion understanding can be categorized into three developmental periods. Initially, children understand the external aspects of emotion, including emotional expressions and their probable situational and external eliciting causes (e.g., Bullock & Russell, 1985; Widen & Russell, 2008; Wu, Muentener, & Schulz, 2017). Then children understand the mental aspects of emotion, including the roles of desires and beliefs (e.g., Lagattuta, Wellman, & Flavell, 1997; Wellman & Banerjee, 1991; Wu et al., 2018; Wu & Schulz, 2018) and the discrepancy between expressed and felt emotions (e.g., Broomfield et al., 2002; Harris et al., 1986). Finally, children understand the role of reflection and appraisal, recognizing for instance, that people can experience mixed feelings (Donaldson & Westerman, 1986; Harter & Buddin, 1987), that reappraisal is a strategy for emotion regulation (Altshuler & Rubble, 1989; Band & Weisz, 1988), and that others’ emotions may be affected by rumination and moral transgressions (e.g., Krettenauer, Malti, & Sokol, 2008; Nunner‐Winkler & Sodian, 1988). Our focus on middle childhood corresponds to children in the second period of this proposed hierarchy of emotion understanding (Pons et al., 2004): an age when children distinguish authentic and expressed emotions, and may be able to recognize that emotions generated for the benefit of an intended audience can be used to infer the audience’s desires.

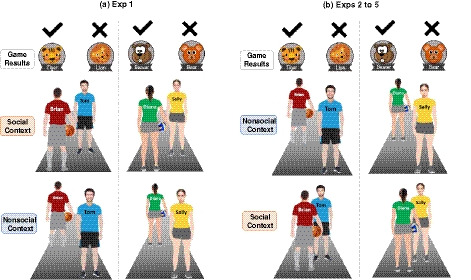

We investigate children’s ability to use one person’s expressions to infer the desires of another by introducing children to simple stories in which one of two teams wins a game (see Figure 1). An observer of the game (henceforth the Protagonist) displays one of two emotional reactions (happy or sad) in front of a social partner, and the contrasting emotional expression (sad or happy) behind the social partner’s back. We ask children both what the protagonist wants and what the social partner wants. Because many studies suggest that 7‐year‐olds can distinguish real and apparent emotion, our primary interest throughout is in children’s ability to recover the desires of the social partner (whose emotional expressions are never shown). Critically, the protagonist displays two contradictory emotions across the social and nonsocial contexts, and the social partner never displays any emotion at all. To succeed at our task, children need to understand that the desires of the social partner will dictate how the protagonist regulates her emotional expression in the social context. As noted, this kind of inference might be especially valuable in understanding rich, interpersonal interactions. In Experiment 1, we test 7‐ to 10‐year‐olds. In Experiment 2, we reduce the task demands and focus only on 7‐ and 8‐year‐olds because as reviewed above, much of the prior work on children's understanding of social display rules suggests that children should be capable of these inferences as early as seven. Experiments 3–5 replicate key findings of Experiment 2 and rule out alternative explanations of our data.

Figure 1.

Example materials. (a) In Exp 1, one of two teams won a game. A protagonist showed one emotional expression in front of a social partner (social context), and a different expression behind the social partner’s back (nonsocial context). (b) In Exps 2–5, the order of the social and nonsocial contexts was reversed. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Experiment 1

Method

Participants

All children in this and the following experiments were recruited from the Boston Children’s Museum between January and November 2017 in the United States. While most of the children were white and middle class, a range of ethnicities and socioeconomic backgrounds reflecting the diversity of the local population (47% European American, 24% African American, 9% Asian, 17% Latino, 4% two or more races) and the museum population (29% of museum attendees receive free or discounted admission) were represented. The Institutional Review Board of MIT approved the research. Parents provided informed consent, and children received stickers for their participation.

In this experiment, 92 children between ages 7 and 10 (M = 8.9 years; range = 7.0–10.9; 50 girls) were tested. There were twenty‐six 7‐year‐olds (M = 7.4 years; range: 7.0–7.9; 10 girls), twenty 8‐year‐olds (M = 8.4 years; range: 8.0–8.9; 14 girls), twenty‐four 9‐year‐olds (M = 9.5 years; range: 9.0–9.9; 13 girls), and twenty‐two 10‐year‐olds (M = 10.5 years; range: 10.0–10.9; 13 girls).

Materials

Each child saw two illustrated stories. Different agents and games were used in each storybook (Tom, Brian, and basketball in one story and Sally, Diana, and volleyball in the other). One story presented the Happy–Sad condition (i.e., [Tom/Sally] was happy in front of [Brian/Diana] but sad behind [Brian/Diana]’s back) and the other presented the Sad–Happy condition (i.e., [Tom/Sally] was sad in front of [Brian/Diana] but happy behind [Brian/Diana]’s back; e.g., Figure 1a). The particular story (i.e., basketball or volleyball) used in each condition (i.e., Happy–Sad or Sad–Happy), and the order of the two conditions were counterbalanced across participants. The facial expressions were from iStock photos (http://www.istockphoto.com/).

Procedure

Children were tested individually; all sessions were videotaped. Children were asked check questions to encourage them to follow along. Incorrect responses were corrected throughout. Children had little difficulty with the check questions; collapsing data from all five experiments in the study, children’s accuracies on the four check questions were 0.92, 0.95, 0.98, and 0.99, respectively. Check questions were used only to maintain children’s attention and were not used as inclusion criteria. Each story was read consecutively, as follows (using the basketball game story as an example).

The experimenter placed the first picture on the table and said, “There is a basketball game today. It’s the Tiger team against the Lion team.” She introduced the next picture and said, “This is Tom. Tom is a basketball fan. He loves watching basketball games. He goes to watch the game. He is either a fan of the Tiger team, or the Lion team, but we don’t know which one.” Children were asked (Check Question 1): “Do we know which team Tom is a fan of?” The experimenter introduced the third picture and said, "This is Brian. Brian was Tom’s friend when they were little, but now they don’t get to see each other very much. Brian became a basketball player. He plays in the game. He either plays for the Tiger team or the Lion team, but we don’t know which one." Children were asked (Check Question 2): “Do we know which team Brian plays for?” The experimenter introduced the fourth picture and said, “The results of the game were that the Tiger team won, and the Lion team lost” (see Figure 1a for this and the next two pictures). Then the experimenter introduced the fifth picture and said, "After the game, Brian ran back to the locker room. Tom was passing by and saw Brian. It was a very noisy and crowded room and they didn’t have a chance to talk. However, in front of Brian, when Tom came passing by, Tom made a face like this." Children were asked (Check Question 3): “Did Tom look happy or sad?” The experimenter introduced the sixth picture and said, “However, behind Brian’s back, as soon as Brian passed by and couldn’t see Tom, Tom made another face.” Children were asked (Check Question 4): “Did Tom look happy or sad?” To match the contexts on surface details, both characters were present in both the social and nonsocial contexts; the difference was only that in the social context, they were facing each other, and in the nonsocial context, they were facing away from each other.

Finally, the experimenter asked two test questions. The first question was about the protagonist (Protagonist Question): “Now I am going to ask you some questions. In front of Brian, Tom looked [happy/sad] but behind Brian’s back, Tom looked [sad/happy]. Do you think Tom is a fan of the Tiger team or the Lion team?” The experimenter then asked the other test question (Social Partner Question): “Does Brian play for the Tiger team or the Lion team?” We asked about the team affiliation (rather than the direct question: “Who did Tom/Brian want to win?”) because it required children to reason about the character’s desires but seemed more natural in this context than asking children to invoke a character’s desire for a counterfactual event. The experimenter coded children’s responses to the two test questions offline from videotapes. All these responses were re‐coded by an independent coder blind to conditions; there was 99% agreement on children’s responses.

Results and Discussion

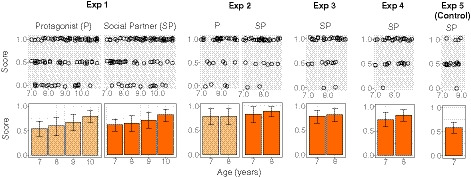

We scored children’s responses separately for the protagonist and the social partner. Children received one point for answering a question correctly and none for answering it incorrectly. Children’s scores were then averaged across the two stories. We compared children’s scores (range: 0–1) to chance level performance (0.5) using Exact Wilcoxon–Pratt Signed‐Rank Test. Overall, children successfully recovered both the protagonist’s desire (M = .65, SD = .40, z = 3.35, p = .001) and the social partner’s desire (M = .70, SD = .37, z = 4.50, p < .001). Using Ordinal Logistic Regression and taking age as a continuous variable, we found significant age effects on both children’s abilities to recover the protagonist’s desire (β = 0.38, SE = 0.17, z = 2.25, p = 0.024) and the social partner’s desire (β = 0.35, SE = 0.17, z = 2.08, p = .038; see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Results. The top row presents children’s performance as a function of age (dots are jittered to avoid overlapping), and the bottom row presents children’s performance averaged by age group. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

As noted, we treated age as a continuous variable. However, given the significant age effects, we did a post hoc, exploratory analysis by age bin (see Figure 2) to enable comparisons with previous literature, which has largely treated age groups categorically. Seven‐year‐olds (n = 26) and 8‐year‐olds (n = 20) failed to perform above chance on either question (7‐year‐olds: protagonist, M = .54, SD = .40, z = 0.50, p = .804; social partner, M = .62, SD = .33, z = 1.73, p = .146; 8‐year‐olds: protagonist, M = .60, SD = .42, z = 1.07, p = .424; social partner, M = .65, SD = .40, z = 1.60, p = .180). Nine‐year‐olds (n = 24) performed above chance on the social partner question (M = .71, SD = .41, z = 2.24, p = .041), but not on the protagonist question (M = .67, SD = .43, z = 1.79, p = .115). Ten‐year‐olds (n = 22) performed above chance on both (protagonist: M = .80, SD = .30, z = 3.36, p < .001; social partner: M = .82, SD = .33, z = 3.30, p = .001).

As noted, many previous studies suggest that by seven and eight, children can predict an agent’s real and apparent emotions given relatively rich contextual information (Banerjee, 1997; Broomfield et al., 2002; Gnepp & Hess, 1986; Gross & Harris, 1988; Harris et al., 1986; Jones et al., 1998; Josephs, 1994; Misailidi, 2006; Naito & Seki, 2009; Wellman & Liu, 2004). They can also represent second‐order mental state information (Perner & Wimmer, 1985; Sullivan, Zaitchik, & Tager‐Flusberg, 1994), which supports the understanding of social display rules (Banerjee & Yuill, 1999; Naito & Seki, 2009). Thus, it is possible that younger children’s difficulties here were due to task demands. In particular, children may have tripped up by the fact that the order of presentation was fixed: the social context always preceded the nonsocial context, thus the first expression children saw was a masked emotional expression. Only when children saw the second expression, did they have sufficient information to realize that the first expression may have reflected only the feelings of the social partner, rather than the protagonist’s true feelings.

In the next experiment, we reduce these task demands by flipping the order of the social and nonsocial contexts. Here, children first see the agent’s emotional expression in the nonsocial context and then the contrasting valence in the social context. This order does not require children to re‐interpret the first emotional expression; additionally, the first expression may provide a basis for children to understand the expression displayed in the social context. Because the prior literature suggests that children integrate emotion understanding and mental state understanding as early as seven; e.g., Pons et al., 2004 for review), and because we expect this manipulation to reduce task demands and improve children’s performance, we focus on the younger half of the age range tested in Experiment 1 to see if 7‐ and 8‐year‐olds can succeed at our task.

Experiment 2

Method

Participants

We determined the sample size of this and all the following experiments with a power analysis. We used a software called G*Power (Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, 2007) to run the analysis based on the Wilcoxon signed‐rank test (one sample case). To be conservative, we calculated the effect sizes of 10‐year‐olds in Experiment 1 (protagonist: d = 1.00; social partner: d = 0.97), and used the smaller effect size (d = 0.97) for the power analysis. Setting α = .05, we found that a sample size of n = 17 per age group sufficed to detect this effect with .95 power. Thus, we recruited children between ages 7 and 8 (M = 7.9 years; range: 7.0–8.8; 23 girls) from the Boston Children’s Museum with 17 children in each age bin (7‐year‐olds: M = 7.5 years, range: 7.0–7.9, 9 girls; 8‐year‐olds: M = 8.3 years, range: 8.0–8.8, 14 girls).

Materials, Procedure and Coding

The materials, procedure and coding were identical to Experiment 1 except that we flipped the order of the social and nonsocial contexts (see Figure 1b). Specifically, instead of first showing Tom’s emotional expression in front of Brian, the experimenter presented Tom’s expression behind Brian’s back, and said: “After the game, Tom made a face like this. At this moment, Brian was nearby but Tom didn’t see him.” Children were asked a check question: “Did Tom look happy or sad?” The experimenter then introduced the next picture and said, “However, Tom turned around and saw Brian. Tom made another face.” Children were asked another check question: “Did Tom look happy or sad?” Children's responses were coded the same way as Experiment 1. Intercoder agreement was 99%.

Results and Discussion

We used the same analyses as in Experiment 1. Overall, 7‐ and 8‐year‐olds recovered both the protagonist’s desire (M = .79, SD = .35, z = 3.78, p < .001) and the social partner’s desire (M = .85, SD = .29, z = 4.54, p < .001). There was no effect of age (protagonist: β = 0.41, SE = 0.73, z = 0.55, p = .580; social partner: β = 0.33, SE = 0.79, z = 0.43, p = .671). Planned analyses revealed that both 7‐ and 8‐year‐olds succeeded at both questions (7‐year‐olds: protagonist, M = .79, SD = .36, z = 2.67, p = .013; social partner, M = .82, SD = .35, z = 2.84, p = .007; 8‐year‐olds: protagonist, M = .79, SD = .36, z = 2.67, p = .013; social partner, M = .88, SD = .22, z = 3.61, p < .001; see Figure 2).

These results suggest that by age seven, children can use changing emotional expressions between social and nonsocial contexts to recover the desires of both participants in a social exchange. However, because the protagonist and the social partner questions were always asked in a fixed order, and the protagonist and the social partner were on different teams, children’s success on the first question (i.e., the protagonist question) was arguably more convincing than their success on the second question (i.e., the social partner question). Once children inferred which team the protagonist wanted to win, they may have simply assumed that the social partner wanted the other team to win without referring to the protagonist’s emotional expression in the social context. To rule out this possibility, in the next experiment, we replicate the design of Experiment 2 but ask only about the social partner. If children’s prior success on the social partner question relied on their answer to the protagonist question, they are likely to fail when asked only about the social partner. However, if their success involved an understanding of social display rules, they should succeed again here.

Experiment 3

Method

Participants

As in Experiment 2, 34 children (M = 8.0 years; range: 7.0–8.9; 18 girls) were recruited from the Boston Children’s Museum. Seventeen of them were 7‐year‐olds (M = 7.5 years; range: 7.0–7.9; 10 girls). The remaining 17 children were 8‐year‐olds (M = 8.4 years; range: 8.0–8.9; 8 girls).

Materials, Procedure and Coding

The materials, procedure, and coding were identical to Experiment 2 except that only the social partner question was asked. We coded children's responses the same way as the proceeding experiments; intercoder agreement was 99%.

Results and Discussion

We used the same analyses as the proceeding experiments. Again, 7‐ and 8‐year‐olds recovered the social partner’s desire (M = .81, SD = .30, z = 4.20, p < .001). There was no effect of age (β = 0.41, SE = 0.68, z = 0.61, p = .542). Planned analyses showed that both 7‐ and 8‐year‐olds succeeded at the social partner question (7‐year‐olds: M = .79, SD = .31, z = 2.89, p = .006; 8‐year‐olds: M = .82, SD = .30, z = 3.05, p = .003; see Figure 2).

This experiment replicated Experiment 2 in suggesting that 7‐ and 8‐year‐olds can use someone’s changing emotional expressions between social and nonsocial contexts to recover the desire of her social partner. These results at least partially rule out the possibility that children’s success in the social partner question in Experiment 2 was due to their tendency to flip their answer to the protagonist question. However, even though the protagonist question was not asked, children may have inferred the desire of the protagonist and (given the change in valence in the protagonist’s emotional expressions) simply concluded that the social partner had the opposing desire. In Experiment 4, we investigate this possibility by making the change of valence irrelevant to the inference. Experiment 4 is identical to Experiment 3 except that the protagonist is not a fan of either team; in the nonsocial context, she expresses an emotional response to an unrelated event (i.e., getting a new book or losing a favorite book). In this case, children can no longer infer the desire of the social partner by inferring the desire of the protagonist. If children still succeed, it provides stronger evidence that children can selectively use someone’s emotional expression in a social context to recover the desire of her intended audience.

Experiment 4

Method

Participants

As in Experiments 2 and 3, 34 children (M = 7.9 years; range: 7.0–8.9; 11 girls) were recruited from the Boston Children’s Museum. Seventeen of them were 7‐year‐olds (M = 7.5 years; range: 7.0–7.9; 5 girls). The remaining 17 children were 8‐year‐olds (M = 8.4 years; range: 8.0–8.9; 6 girls).

Materials, Procedure, and Coding

Experiment 4 was identical to Experiment 3 except as follows. When the experimenter introduced the protagonist, she did not say that he was a sports fan. Instead she said: “This is Tom. Today Tom got a new book he expected for a long time” or “This is Tom. Tom lost his favorite book today.” Tom’s facial expression was happy or sad, respectively. The experimenter asked a check question: “Did he look happy or sad?”

Minor changes were made in the description of the last three pictures as well. When the experimenter introduced the results of the game, she said: “The results of the game were that the Tiger team won and the Lion team lost.” She also emphasized: “Everyone knew the results” to tell the child that Tom knew the results even though he did not go to watch the game. The experimenter then placed the next picture on the table and said: “After the game, Tom was still [happy/sad] about his [new/lost] book. At this moment, Brian was nearby but Tom did not see him.” She placed the final picture on the table and said: “Then Tom turned around and saw Brian. Tom made a different face.” The experimenter asked another check question: “Did he look happy or sad?” The materials, procedure and coding were otherwise the same as Experiment 3. We coded children's responses the same way as the proceeding experiments; intercoder agreement was 99%.

Results and Discussion

We used the same analyses as the proceeding experiments. Children again successfully recovered the social partner’s desire (M = .78, SD = .28, z = 4.15, p < .001) and there was no effect of age (β = 0.75, SE = 0.62, z = 1.21, p = .228). Planned analyses revealed that children in both age groups succeeded at the task (7‐year‐olds: M = .74, SD = .31, z = 2.53, p = .021; 8‐year‐olds: M = .82, SD = .25, z = 3.32, p < .001; see Figure 2).

Thus, together with Experiment 3, Experiment 4 provides converging evidence that children’s success in the social partner question cannot be explained by their tendency to choose the desire contrasting with that of the protagonist. Even when the desire of the protagonist was not explicitly referenced (Experiment 3), and when the protagonist’s affiliation with the teams was unknown (Experiment 4), children selectively used the protagonist’s emotional expression in the social context to infer the desire of her social partner.

In the next experiment, we investigate a different heuristic that children might have used to pass the social partner question: they might have simply assumed that the social partner had the same expression as the protagonist when they were facing each other without making any mental state inferences about social display rules. To rule out this possibility, in Experiment 5, we made the protagonist’s emotional expressions in both the social and nonsocial contexts irrelevant to the story. Specifically, in the Happy–Sad condition, children were told that the protagonist was happy about her new book in the nonsocial context and sad in front of her social partner because her new book fell into a puddle and got all muddy; in the Sad–Happy condition, the protagonist was sad about her lost book in the nonsocial context but happy in front of her social partner because she found the lost book. If children simply used a face‐matching heuristic in the face‐to‐face context to pass the social partner question, they should perform similarly here. However, if children’s successes in Experiments 2–4 were based on mental state inferences about social display rules, then children should perform at chance in Experiment 5 where the expressions are not governed by those rules. Because the concern about using a simple face‐matching heuristic presumably applies more to younger children than older ones, we focused only on 7‐year‐olds in Experiment 5.

Experiment 5

Method

Participants

Seventeen 7‐year‐olds (M = 7.6 years; range: 7.1–7.9; 11 girls) were recruited from the Boston Children’s Museum.

Materials, Procedure, and Coding

The materials, procedure and coding were the same as Experiment 4 with one exception. In the Happy–Sad condition, when the experimenter introduced the last picture, she said: “Then Tom turned around and saw Brian. At the same moment, Tom’s new book fell into a puddle and got all muddy!” In the Sad–Happy condition, she said: “Then Tom turned around and saw Brian. At the same moment, Tom saw his book sitting right there on the bench. So his book wasn’t lost at all!” The experimenter then asked a check question: “Did he look happy or sad?” We coded children's responses the same way as the proceeding experiments; intercoder agreement was 100%.

Results and Discussion

We found that when the protagonist was responding to an unrelated event in the social context, 7‐year‐olds did not use the protagonist’s emotional expression to infer the desire of the social partner and performed at chance (M = .59, SD = .26, z = 1.34, p = .375). There was no effect of age (β = 1.12, SE = 1.98, z = 0.56, p = .573; see Figure 2). This suggests that children’s ability to recover the desire of the social partner in Experiments 2–4 was not simply due to matching the protagonist’s expression to the social partner's when they were facing each other. Since children did not just assume the protagonist’s expression matched the social partner’s in a face‐to‐face context but the protagonist was responding to an unrelated event, it is unlikely that children’s ability to recover the desire of the social partner in Experiments 2–4 was due to a simple heuristic rather than the (behaviorally equivalent but inferentially richer) understanding that the protagonist was displaying the emotion congruent with her social partner’s desires.

General Discussion

In five experiments, we found that children were able to use the information embedded in social display rules to recover others’ otherwise under‐determined mental states. In Experiment 1, children saw an emotional expression when a protagonist was in front of a social partner (Social Context), and then a different expression when the protagonist was behind the social partner’s back (Nonsocial Context). Children between ages seven and ten were increasingly able to infer both the protagonist’s and social partner’s desires. This is striking, especially since the protagonist displayed two contradictory emotional expressions and the social partner’s expressions were never observed at all. However, because children could not know that the initial expression was regulated until they saw the contrasting emotional expression in the nonsocial context, the task might have been especially demanding for younger children. In Experiment 2 we reduced the processing demands by flipping the order of the social and nonsocial contexts and found that even 7‐ and 8‐year‐olds succeeded. Experiments 3 and 4 replicated key findings of Experiment 2 as well as ruling out the possibility that children may have passed the social partner question simply by flipping their answers to the protagonist question. Finally, Experiment 5 ruled out an additional heuristic: the possibility that children assumed that the social partner mirrored the protagonist’s expression when they were facing each other. However, as predicted, when the protagonist’s emotional expression was not influenced by social display rules, 7‐year‐olds did not use the protagonist’s emotional expressions to reason about the desire of the social partner. Taken together, these results suggest that children can use their knowledge of social display rules and emotional expressions to infer not only the desire of the person expressing the emotions, but also that of the person perceiving the expression.

Our study builds on many previous studies that have looked at children’s ability to predict an agent’s real and apparent emotions in the context of social display rules. As noted, some of these studies provided rich contextual information (e.g., the agent’s desires, true feelings, her intentions, and a motivation to hide her true feelings) which may have overestimated children’s abilities (Banerjee, 1997; Gross & Harris, 1988; Harris et al., 1986; Josephs, 1994; Misailidi, 2006; Naito & Seki, 2009; Wellman & Liu, 2004). Other studies used less detailed scenarios but those scenarios are open to interpretations that do not involve social display rules at all (Broomfield et al., 2002; Gnepp & Hess, 1986; Jones et al., 1998). Our study overcomes these limitations by creating a scenario that was neither rich and detailed nor ambiguous: 7‐year‐olds were able to infer the desires of a protagonist’s social partner merely by knowing that the protagonist’s expressions changed between a social and nonsocial context.

Developmentally, our findings are broadly consistent with accounts proposing that 7‐ and 8‐year‐olds integrate mental state understanding and emotion understanding (Pons et al., 2004). The current results are also in line with a small set of studies looking at children’s ability to make inverse inference from observed emotional cues to unobservable mental states. Those studies have found that children can use someone’s emotional expression to recover what the person herself wants and believes (e.g., Repacholi & Gopnik, 1997; Wellman et al., 2000; Wu et al., 2018; Wu & Schulz, 2018). However, the current findings go beyond previous work in showing that children can use someone’s emotional expression and their understanding of display rules to recover what another person wants. To our knowledge, this is the first evidence showing that children are able to use one person’s emotional expression to recover the mental states of another. This suggests that emotional expressions provide a valuable entrée into others’ minds, and our findings provide novel insights into the extent to which children can recover rich information from observed emotional cues.

Although there has been debate on the extent to which reasoning about prosocial display rules requires second‐order mental state representation (Banerjee & Yuill, 1999; Naito & Seki, 2009), the debate pertains largely to contexts in which children might understand the social‐display rule because the intended audience’s desires are well‐established (e.g., as in gift giving scenarios where the giver presumably wants the receiver to like the present). In our task by contrast, the social partner’s beliefs, desires, and emotions were unknown throughout. To recover information about the social partner, children had to use the protagonist’s emotional expressions to gain insight into the mind of her audience. We believe that this kind of inference does require recursive mental state reasoning. The current results suggest that the ability to make these inferences is present by middle childhood, consistent with other work on children’s ability to entertain second‐order beliefs like “John thinks that Mary thinks …” (see Grueneisen, Wyman, & Tomasello, 2015; Perner & Wimmer, 1985; Talwar, Gordon, & Lee, 2007; though see Sullivan et al., 1994 for even earlier success on simplified tasks).

Critically, however, the inferential route children had to go may be distinct from the explicit inferences the children entertained. Because children have neither direct nor indirect access to the social partner’s mental states, they can only proceed by considering the protagonist’s reaction to the social partner. Nonetheless, children might have explicitly represented only the social partner’s desires (e.g., that Brian wanted the Lions to win) or they might have represented the protagonist’s beliefs about the social partner’s desires (e.g., that Tom thought Brian wanted the Lions to win). By seven and eight, children are capable of coordinating multiple perspectives and handling embedded complements (e.g., de Villiers & Pyers, 2002; Naito & Seki, 2009; Pons et al., 2004), so it is possible that children explicitly entertained second‐order beliefs (e.g., Tom thinks that Brian wants …). However, because both representations will lead to the correct conclusion (e.g., that Brian supports the Lions) we cannot distinguish the direct from embedded inference in this study so we conservatively frame these inferences as being about the third party’s probable desires (rather than the beliefs about those desires) throughout.

Interestingly, however, many real‐world contexts have the same ambiguity. When our colleague says, “It’s raining,” we may represent the fact that it’s raining but fail to represent that all we really know is that our colleague believes this to be the case. Consistent with this, failures of source memory are common in both adults and children (e.g., Cycowicz, Friedman, Snodgrass, & Duff, 2001; Gopnik & Astington, 1988; Taylor, Esbensen, & Bennett, 1994). One exception, however, is when we have reason to believe an informant is unreliable; in such cases, both adults and children can be epistemically vigilant (e.g., Koenig, Clément, & Harris, 2004; Sperber et al., 2010). In this study, the context suggested that the protagonist was certain about the social partner’s affiliation; however, in future work it would be interesting to look at how children interpret emotional expressions when the person expressing the emotion might be ignorant or mistaken. Given more uncertainty, children may be less likely to impute desires directly to the social partner and instead explicitly represent the protagonist’s beliefs about the partner.

Note also that our experiment contained both contexts in which the protagonist’s expression in the social context most likely belied her true feelings (Experiments 1–3, where the protagonist displayed the opposite valenced emotion in the nonsocial context) and contexts in which there was no reason to suppose that the protagonist’s expression in the social context was not entirely sincere (Experiment 4, where the opposite valenced emotion in the nonsocial context referred to an unrelated event). These different contexts capture some of the range of authentic emotions that might underlie any socially displayed expressions: Protagonists may wholeheartedly share the feelings of their social partner, have genuine feelings on the other person’s behalf independent of their own feelings about the matter (e.g., someone may be sincerely happy or sad for someone else even if they feel the opposite way themselves), be entirely neutral, or be at odds with their partner and displaying feigned, inauthentic emotions. Much of the developmental research has investigated the last of these, focusing on children’s ability to distinguish real and apparent emotions (Banerjee, 1997; Broomfield et al., 2002; Gnepp & Hess, 1986; Gross & Harris, 1988; Harris et al., 1986; Jones et al., 1998; Josephs, 1994; Misailidi, 2006; Naito & Seki, 2009; Wellman & Liu, 2004). The current research, however, suggests that the emotion apparent in social contexts may be informative despite the range of real emotions that could underlie it; although displayed emotions may be ambiguous about the protagonist’s own feelings, they may nonetheless be relatively unambiguous about the mental states of her audience. Consistent with this, researchers have suggested that emotional expressions may serve both as a component of an authentic emotional response and be adapted for communicative purposes (Shariff & Tracy, 2011).

In this study, we manipulated the expression of emotion in social and nonsocial contexts and looked at children’s responses to the manipulation on average; we did not consider sources of individual difference in children’s inferences. However, many factors might affect children’s understanding of social display rules, including gender (Brody & Hall, 2008; Davis, 1995), temperament (Brody, 2000; Calkins, 1994), and culture (Cole, Bruschi, & Tamang, 2002; Matsumoto, 1990). Future research might look at how these factors influence children’s ability to infer the mental states of observers who are the intended audience of others’ emotional expressions.

We also note that our scenario is ambiguous about the protagonist’s motivation for regulating her emotional reaction. She might have done so for prosocial reasons (to avoid hurting the feelings of her social partner), for self‐protective reasons (to avoid negative outcomes), or for self‐presentational ones (to appear nice and avoid appearing boastful). In any case, the protagonist’s emotional expression in the social context provides information about the mental states of her social partner. However, it would be interesting in future research to look at whether different motivations for emotion regulation affect the inferences that children draw.

Additionally, although the protagonist changed her emotional expression in all cases of our study, the salience of the relevance between this change and the mental state of the social partner varies slightly across different contexts. In Experiments 1–3, the protagonist was a sports fan and she went to watch a sports game that the social partner played for. The possibility that the protagonist and the social partner could have supported different teams and have different emotional responses to the outcome makes it salient that the protagonist’s changing emotional expression might have something to do with the social partner’s team affiliation. In contrast, in Experiment 4, the protagonist was not a sports fan at all and, when she was alone, responded to something irrelevant. Relative to Experiments 1–3, it is thus less obvious that the protagonist’s change of emotional expression was due to her understanding of her social partner’s feelings about the outcome of the game. Nonetheless, children spontaneously linked the change of emotional expression to the social partner’s team affiliation in this case as well. This suggests that children have a relatively flexible understanding of the inferences licensed by social display rules.

Our study was limited in using sports games for the scenarios throughout. We chose this domain not only because it is familiar, but because it is one in which individuals may have opposite‐valanced emotional reactions to the same outcome. The context thus makes it easy to establish relatively unbiased priors for the affiliations of the protagonist and social partner. However, since previous research suggests that children’s understanding of social display rules is influenced by what they experience in the home and family (e.g., Jones et al., 1998), it is possible that children’s performance on our tasks might be influenced by their familiarity with the specific content domain. Future research could use a wider range of child‐friendly scenarios to see if we can replicate these findings, and potentially extend the investigation to younger children.

Children also succeeded here in a very tightly constrained context: there were only two possible outcomes (one of two teams won a game), two possible emotional responses (happy or sad), and two characters. Moreover, the task design virtually eliminated any memory demands: children did not need to track the changing emotional expressions over time; they were concurrently displayed in the storybook card format, together with the social context. Future work might look at children’s ability to draw these kinds of inferences when they must track changing emotional dynamics over time or in more complex, multiparticipant scenarios. Note, however, that although more realistic scenarios may add processing demands and complexity, they may also provide children with richer cues to agents’ mental states.

Finally, as discussed, children meet new challenges in their peer relationships as their social environments transit from families to schools (Caputi et al., 2012; Cassidy et al., 1992; Denham et al., 1990; Greenberg et al., 1995; Izard et al., 2001; Mostow et al., 2002). Children interact with many more people at school than in their families, and the background of those individuals becomes more diverse. Children’s relationships also become more complex, as over development, they become increasingly able to exert the effortful control needed to monitor and regulate their emotional expressions (Saarni, 1984). By middle childhood, peers’ emotional displays are frequently tailored for the benefit of others (Simonds, Kieras, Rueda, & Rothbart, 2007) and it may be especially valuable for children to be able to use one person’s emotional expressions to infer the beliefs and desires of the intended audience. Such sophisticated mindreading abilities may help children better understand peer dynamics, choose social partners, and understand how to be better friends with others. Future research could look at whether the abilities studied here correlate with the quality of children’s peer relationships broadly.

Overall the current results suggest that at least in constrained contexts, children can recover otherwise underdetermined mental states from emotional expressions in social contexts. Intriguingly, the current results also suggest that there is a limit to how much we can hide in hiding our feelings. In disguising our true feelings, we may reveal what we think about what other people want.

This study is supported by the Center for Brains, Minds and Machines (CBMM), funded by NSF STC award CCF‐1231216. The authors thank the Boston Children’s Museum and participating parents and children. The authors also thank Rachel Magid, Michelle Wang, and Kary Richardson for helpful feedback, and to Elizabeth Rizzoni, Catherine Wu, and Sydney Kuo for help with data collection and coding.

References

- Altshuler, J. , & Rubble, D. (1989). Developmental changes in children's awareness of strategies for coping with uncontrollable stress. Child Development, 60, 1337–1349. 10.2307/1130925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Band, E. B. , & Weisz, J. R. (1988). How to feel better when it feels bad: Children's perspectives on coping with everyday stress. Developmental Psychology, 24(2), 247–253. 10.1037/0012-1649.24.2.247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, M. (1997). Hidden emotions: Preschoolers' knowledge of appearance‐reality and emotion display rules. Social Cognition, 15, 107–132. 10.1521/soco.1997.15.2.107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, R. , & Yuill, N. (1999). Children's understanding of self‐presentational display rules: Associations with mental‐state understanding. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 17, 111–124. 10.1348/026151099165186 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brody, L. R. (2000). The socialization of gender differences in emotional expression: Display rules, infant temperament, and differentiation In Fischer A. H. (Ed.), Gender and emotion: Social psychological perspectives (pp. 24–47). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 10.1017/CBO9780511628191.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brody, L. R. , & Hall, J. A. (2008). Gender and emotion in context In Lewis M., Haviland‐Jones J. M., & Barrett L. F. (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (3rd ed., pp. 395–408). New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Broomfield, K. A. , Robinson, E. J. , & Robinson, W. P. (2002). Children's understanding about white lies. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 20, 47–65. 10.1348/026151002166316 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock, M. , & Russell, J. A. (1985). Further evidence on preschoolers' interpretation of facial expressions. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 8, 15–38. 10.1177/016502548500800103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins, S. D. (1994). Origins and outcomes of individual differences in emotion regulation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59(2/3), 53–72. 10.2307/1166138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caputi, M. , Lecce, S. , Pagnin, A. , & Banerjee, R. (2012). Longitudinal effects of theory of mind on later peer relations: the role of prosocial behavior. Developmental Psychology, 48, 257–270. 10.1037/a0025402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy, J. , Parke, R. D. , Butkovsky, L. , & Braungart, J. M. (1992). Family‐peer connections: The roles of emotional expressiveness within the family and children's understanding of emotions. Child Development, 63, 603–618. 10.2307/1131349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole, P. M. , Bruschi, C. J. , & Tamang, B. L. (2002). Cultural differences in children's emotional reactions to difficult situations. Child Development, 73, 983–996. 10.1111/1467-8624.00451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cycowicz, Y. M. , Friedman, D. , Snodgrass, J. G. , & Duff, M. (2001). Recognition and source memory for pictures in children and adults. Neuropsychologia, 39, 255–267. 10.1016/S0028-3932(00),00108-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, T. L. (1995). Gender differences in masking negative emotions: Ability or motivation? Developmental Psychology, 31, 660–667. 10.1037/0012-1649.31.4.660 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Villiers, J. G. , & Pyers, J. E. (2002). Complements to cognition: A longitudinal study of the relationship between complex syntax and false‐belief‐understanding. Cognitive Development, 17, 1037–1060. 10.1016/S0885-2014(02),00073-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Denham, S. A. , McKinley, M. , Couchoud, E. A. , & Holt, R. (1990). Emotional and behavioral predictors of preschool peer ratings. Child development, 61, 1145–1152. 10.2307/1130882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, S. , & Westerman, M. (1986). Development of children's understanding of ambivalence and causal theories of emotion. Developmental Psychology, 22, 655–662. 10.1037/0012-1649.22.5.655 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F. , Erdfelder, E. , Lang, A.-G. , & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191. 10.3758/BF03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu, G. , & Lee, K. (2007). Social grooming in the kindergarten: The emergence of flattery behavior. Developmental Science, 10, 255–265. 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00583.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnepp, J. , & Hess, D. L. (1986). Children's understanding of verbal and facial display rules. Developmental Psychology, 22, 103–108. 10.1037/0012-1649.22.1.103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gopnik, A. , & Astington, J. W. (1988). Children's understanding of representational change and its relation to the understanding of false belief and the appearance‐reality distinction. Child Development, 59, 26–37. 10.2307/1130386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, M. T. , Kusche, C. A. , Cook, E. T. , & Quamma, J. P. (1995). Promoting emotional competence in school‐aged children: The effects of the PATHS curriculum. Development and psychopathology, 7, 117–136. 10.1017/S0954579400006374 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gross, D. , & Harris, P. L. (1988). False beliefs about emotion: Children's understanding of misleading emotional displays. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 11, 475–488. 10.1177/016502548801100406 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grueneisen, S. , Wyman, E. , & Tomasello, M. (2015). "I know you don't know i know…" children use second‐order false‐belief reasoning for peer coordination. Child Development, 86, 287–293. 10.1111/cdev.12264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadwin, J. , & Perner, J. (1991). Pleased and surprised: Children's cognitive theory of emotion. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 9, 215–234. 10.1111/j.2044-835X.1991.tb00872.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, P. L. , Donnelly, K. , Guz, G. R. , & Pitt‐Watson, R. (1986). Children's understanding of the distinction between real and apparent emotion. Child Development, 57, 895–909. 10.2307/1130366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter, S. , & Buddin, B. (1987). Children's understanding of the simultaneity of two emotions: A five‐stage acquisition sequence. Developmental Psychology, 23, 388–399. 10.1037/0012-1649.23.3.388 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman, G. D. , Sweet, M. A. , & Lee, K. (2009). Children's reasoning about lie‐telling and truth? Telling in politeness contexts. Social Development, 18, 728–746. 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00495.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izard, C. , Fine, S. , Schultz, D. , Mostow, A. , Ackerman, B. , & Youngstrom, E. (2001). Emotion knowledge as a predictor of social behavior and academic competence in children at risk. Psychological Science, 12, 18–23. 10.1111/1467-9280.00304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D. C. , Abbey, B. B. , & Cumberland, A. (1998). The development of display rule knowledge: Linkages with family expressiveness and social competence. Child Development, 69, 1209–1222. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.tb06168.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephs, I. E. (1994). Display rule behavior and understanding in preschool children. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 18, 301–326. 10.1007/BF02172291 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, M. A. , Clément, F. , & Harris, P. L. (2004). Trust in testimony: Children's use of true and false statements. Psychological Science, 15, 694–698. 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00742.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krettenauer, T. , Malti, T. , & Sokol, B. W. (2008). The development of moral emotion expectancies and the happy victimizer phenomenon: A critical review of theory and application. International Journal of Developmental Science, 2, 221–235. [Google Scholar]

- Lagattuta, K. , Wellman, H. , & Flavell, J. (1997). Preschoolers' understanding of the link between thinking and feeling: Cognitive cueing and emotional change. Child Development, 68, 1081–1104. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01986.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLaren, R. , & Olson, D. (1993). Trick or treat: Children's understanding of surprise. Cognitive Development, 8, 27–46. 10.1016/0885-2014(93)90003-N [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, D. (1990). Cultural similarities and differences in display rules. Motivation and Emotion, 14, 195–214. 10.1007/BF00995569 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Misailidi, P. (2006). Young children's display rule knowledge: Understanding the distinction between apparent and real emotions and the motives underlying the use of display rules. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 34, 1285–1296. 10.2224/sbp.2006.34.10.1285 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mostow, A. J. , Izard, C. E. , Fine, S. , & Trentacosta, C. J. (2002). Modeling emotional, cognitive, and behavioral predictors of peer acceptance. Child Development, 73, 1775–1787. 10.1111/1467-8624.00505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naito, M. , & Seki, Y. (2009). The relationship between second? Order false belief and display rules reasoning: The integration of cognitive and affective social understanding. Developmental Science, 12, 150–164. 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00748.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunner‐Winkler, G. , & Sodian, B. (1988). Children's understanding of moral emotions. Child Development, 59, 1323–1338. 10.2307/1130495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perner, J. , & Wimmer, H. (1985). "John thinks that Mary thinks that…" attribution of second‐order beliefs by 5‐to 10‐year‐old children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 39, 437–471. 10.1016/0022-0965(85),90051-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pons, F. , Harris, P. L. , & de Rosnay, M. (2004). Emotion comprehension between 3 and 11 years: Developmental periods and hierarchical organization. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 1, 127–152. 10.1080/17405620344000022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Popliger, M. , Talwar, V. , & Crossman, A. (2011). Predictors of children's prosocial lie‐telling: Motivation, socialization variables, and moral understanding. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 110, 373–392. 10.1016/j.jecp.2011.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repacholi, B. M. , & Gopnik, A. (1997). Early reasoning about desires: Evidence from 14‐and 18‐month‐olds. Developmental Psychology, 33, 12–21. 10.1037/0012-1649.33.1.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieffe, C. , Terwogt, M. M. , & Cowan, R. (2005). Children's understanding of mental states as causes of emotions. Infant and Child Development, 14, 259–272. 10.1002/icd.391 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruffman, T. , & Keenan, T. R. (1996). The belief‐based emotion of suprise: The case for a lag in understanding relative to false belief. Developmental Psychology, 32, 40–49. 10.1037/0012-1649.32.1.40 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saarni, C. (1984). An observational study of children's attempts to monitor their expressive behavior. Child Development, 55, 1504–1513. 10.2307/1130020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shariff, A. F. , & Tracy, J. L. (2011). What are emotion expressions for? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20, 395–399. 10.1177/0963721411424739 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simonds, J. , Kieras, J. E. , Rueda, M. R. , & Rothbart, M. K. (2007). Effortful control, executive attention, and emotional regulation in 7–10‐year‐old children. Cognitive Development, 22, 474–488. 10.1016/j.cogdev.2007.08.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skerry, A. E. , & Spelke, E. S. (2014). Preverbal infants identify emotional reactions that are incongruent with goal outcomes. Cognition, 130, 204–216. 10.1016/j.cognition.2013.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperber, D. , Clément, F. , Heintz, C. , Mascaro, O. , Mercier, H. , Origgi, G. , & Wilson, D. (2010). Epistemic vigilance. Mind & Language, 25, 359–393. 10.1111/j.1468-0017.2010.01394.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stein, N. L. , & Levine, L. J. (1989). The causal organisation of emotional knowledge: A developmental study. Cognition & Emotion, 3, 343–378. 10.1080/02699938908412712 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, K. , Zaitchik, D. , & Tager‐Flusberg, H. (1994). Preschoolers can attribute second‐order beliefs. Developmental Psychology, 30, 395–402. 10.1037/0012-1649.30.3.395 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Talwar, V. , Gordon, H. M. , & Lee, K. (2007). Lying in the elementary school years: Verbal deception and its relation to second‐order belief understanding. Developmental Psychology, 43, 804–810. 10.1037/0012-1649.43.3.804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, M. , Esbensen, B. M. , & Bennett, R. T. (1994). Children's understanding of knowledge acquisition: The tendency for children to report that they have always known what they have just learned. Child Development, 65, 1581–1604. 10.2307/1131282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warneken, F. , & Orlins, E. (2015). Children tell white lies to make others feel better. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 33, 259–270. 10.1111/bjdp.12083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellman, H. M. (2014). Making minds: How theory of mind develops. Oxford University Press; 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199334919.001.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wellman, H. M. , & Banerjee, M. (1991). Mind and emotion: Children's understanding of the emotional consequences of beliefs and desires. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 9, 191–214. 10.1111/j.2044-835X.1991.tb00871.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wellman, H. M. , & Liu, D. (2004). Scaling of theory‐of‐mind tasks. Child Development, 75, 523–541. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00691.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellman, H. M. , Phillips, A. T. , & Rodriguez, T. (2000). Young children's understanding of perception, desire, and emotion. Child Development, 71, 895–912. 10.1111/1467-8624.00198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellman, H. M. , & Woolley, J. D. (1990). From simple desires to ordinary beliefs: The early development of everyday psychology. Cognition, 35, 245–275. 10.1016/0010-0277(90)90024-E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widen, S. C. , & Russell, J. A. (2008). Children acquire emotion categories gradually. Cognitive Development, 23, 291–312. 10.1016/j.cogdev.2008.01.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y. , Haque, J. A. , & Schulz, L. E. (2018). Children can use others' emotional expressions to infer their knowledge and predict their behaviors in classic false belief tasks. In Proceedings of the 40th Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society (pp. 1193–1198).

- Wu, Y. , Muentener, P. , & Schulz, L. E. (2017). One‐ to four‐year‐olds connect diverse positive emotional vocalizations to their probable causes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 114, 11896–11901. 10.1073/pnas.1707715114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y. , & Schulz, L. E. (2018). Inferring beliefs and desires from emotional reactions to anticipated and observed events. Child Development, 89, 649–662. 10.1111/cdev.12759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, F. , Bao, X. , Fu, G. , Talwar, V. , & Lee, K. (2010). Lying and truth‐telling in children: From concept to action. Child Development, 81, 581–596. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01417.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]