Abstract

First‐trimester abortion became legal in Mexico City in April 2007. Since then, 216 755 abortions have been provided, initially in hospitals, by specialized physicians using surgical techniques. With time and experience, services were provided increasingly in health centers, by general physicians using medical therapies. Meanwhile, abortion remains legally restricted in the remaining 31/32 Mexican states. Demand and need for abortion care have increased throughout the country, while overall abortion‐specific mortality rates have declined. In an effort to ensure universal access to and improved quality of reproductive and maternal health services, including abortion, Mexico recently expanded its cadres of health professionals. While initial advances are evident in pregnancy and delivery care, many obstacles and barriers impair the task‐sharing/shifting process in abortion care. Efforts to expand the provider base for legal abortion and postabortion care to include midlevel professionals should be pursued by authorities in the new Mexican administration to further reduce abortion mortality and complications.

Keywords: Abortion, Abortion mortality, Legal abortion, Medical abortion, Mexico, Task‐sharing

Short abstract

In Mexico, abortion services are increasing while mortality is decreasing in both restricted and permissive legal settings. While task‐sharing could potentially contribute to these trends, more coordinated and focused policy efforts are needed.

1. Background

Abortion care represents a significant and increasing component of reproductive health care in Mexico. However, access to services, quality of care, and safety of procedures vary widely among Mexican states, particularly because of diverse legal contexts: first‐trimester abortion is legal upon a woman's request only in Mexico City, while it remains restricted in the rest of the country. Task‐sharing and task‐shifting strategies have the potential to improve access, quality, and safety of abortion services, by increasing the number of sensitized and trained health professionals, including nonmedical providers.

The purpose of the present paper is to summarize recent data on unequal access to and safety of abortion care in Mexico, with a focus on legal services in Mexico City compared to the rest of the country. Trends in abortion hospitalizations and mortality are presented, analyzing how different legal contexts and access to services moderate these outcomes. A secondary objective is to document how recent strategies undertaken to decentralize service delivery and expand health workers’ roles can potentially impact access to and quality of abortion care in the country. This study is part of a multicountry project with similar objectives.

2. Materials and Methods

We analyzed recent morbidity and mortality health statistics in Mexico, as well as published and grey literature on abortion, including legally induced (interrupción legal del embarazo [ILE] in Spanish) and all types of abortion including spontaneous, ectopic, molar, unspecified, and other types of abortion (ICD‐10 codes O00‐08).

We also reviewed relevant policies (laws, regulations, norms, and technical guidelines) on the provision of postabortion and legal abortion services by type of provider, level of services, required competencies, and accreditation/certification processes. Published and grey literature on task‐sharing and task‐shifting strategies in Mexico were included, for reproductive, maternal, and abortion care specifically.

We conducted individual interviews with nine key stakeholders and three group discussions, using a semistructured guide to explore their perceptions of present policies, infrastructure, and resources; to identify barriers, facilitators, and opportunities to improve legal frameworks and effectively implement task‐sharing and task‐shifting strategies to expand health cadres’ roles in abortion care. Individual interviewees included the Director and Deputy Director of Maternal and Reproductive Health from the Federal Ministry of Health (MoH); the corresponding Director for Mexico City MoH; the Deputy Director of the Legal Department of the Mexico City MoH; the chief Nurse in charge of the ILE program in Mexico City; the Medical Director of an international nongovernmental organization (NGO) providing private abortion services; the Senior Program Officer of another NGO coordinating projects on task‐sharing in abortion care; the past‐Director of a midwifery school; and the Director of a donor foundation supporting task‐sharing in sexual, reproductive, maternal, and neonatal health (SRMNH).

Participants in group discussions were from a variety of different backgrounds including international agencies; academic institutions with experience in research and evaluation of task‐sharing; service providers; professional midwives and nurses’ organizations; and members of civil society. Both authors took notes and these were compared; we analyzed and interpreted the data separately and then discussed the main findings together. The conceptual framework of the policy component of the study was based on the Supporting the Use of Research Evidence (SURE) framework, which provides a comprehensive list of possible factors that may influence the implementation of health system interventions.1 The SURE framework helped to guide our research, conduct the discussions, interpret our results, and inform our conclusions. Previous implementation efforts and experiences were also useful in guiding our research.2, 3

3. Results

3.1. Abortion in Mexico: unequal access to and quality of abortion services

3.1.1. Legal restrictions and abortion morbidity and mortality in 31 Mexican states

Mexico is a federal country. Abortion is regulated both at federal level (Federal Penal Code: FPC) and at state level. Since 1931, the FPC penalizes with prison both the woman who undergoes an abortion and the person who performs it, additionally revoking professional licenses to the health personnel involved: physician, surgeon, comadron‐partera (midwife). Abortion is not criminally persecuted when it is unintentional (imprudencial in Spanish), when there is risk to a woman's life, or in the case of rape. States’ Penal Codes and health regulations similarly allow legal abortion only under specific circumstances. In recent years, minor exceptions were added in some states: severe risk to health, fetal malformations, and poor socioeconomic conditions (i.e. poor women with at least three children).4, 5, 6 After the emblematic “Paulina” case, a 13‐year‐old girl denied a legal termination of her pregnancy resulting from a brutal rape,7 the Official Mexican Norm on Sexual Violence was updated and new health regulations and guidelines were published,8, 9, 10 stating that legal abortion in cases of rape must be performed in hospitals by trained physicians to guarantee the safety of the procedure, according to the WHO definition at the time.11 Even when permitted by law, however, access to legal abortion services under these exceptions has been extremely limited, poorly registered, and hardly evaluated.12

As in all countries where abortion is legally restricted, its incidence can only be based on indirect estimates.13, 14, 15 Most recently, this methodology and the corresponding estimates have been adjusted, in line with a new WHO classification of abortion safety.16, 17 Overall, the estimated induced abortion rate (IAR) in Mexico has increased over time: 38 abortions per 1000 women aged 15–44 years in 2009, up from 25 in 1990.18 In Mexico City, the most recent IAR was estimated at 54.4 abortions per 1000 women.19

An alternative approach, which reflects all cases attended in the formal health system, is to analyze abortion hospitalization and mortality cases from official databases of public health information systems; inclusion criteria and data collection methodology have been previously described in detail.20 According to these sources, numbers and rates of abortion hospitalizations increased between 2000 and 2008, but with profound differences among states. Overall, abortion hospitalizations represented one in 10 obstetric hospitalizations over this period.20

New analysis of the public health sector, updated for the present study, which includes all types of abortions attended in hospitals, primary care clinics, and emergency rooms, shows that abortion cases increased but stabilized in recent years. Rates were 6.8 abortions per 1000 women aged 15–44 years in 2000, peaked at 8.1 in 2011, but decreased to 7.1 in 2016; the national mean rate was 7.3 in this period, which is similar to another study.21 Important differences among states persisted over the whole period22 (Table 11).

Table 1.

Abortion hospitalization rates and Abortion Mortality Rates by Mexican states, 2000–2016.a

| Mexican states | Abortion hospitalization ratesb | Abortion mortality ratec |

|---|---|---|

| National (all Mexico) | 7.3 | 40.3 |

| Baja California Sur | 9.81 | 7.9 |

| Colima | 9.00 | 8.3 |

| Sinaloa | 8.28 | 14.7 |

| Querétaro | 8.59 | 16.4 |

| Coahuila | 8.76 | 18.3 |

| Tamaulipas | 8.65 | 20.4 |

| Aguascalientes | 9.94 | 22.7 |

| Mexico City | 12.47 | 24.6 |

| Zacatecas | 9.13 | 25.1 |

| Baja California | 7.89 | 26.1 |

| Guanajuato | 7.17 | 26.5 |

| Jalisco | 7.54 | 27.2 |

| Sonora | 8.28 | 29.4 |

| Durango | 9.00 | 29.9 |

| Quintana Roo | 8.25 | 32.0 |

| San Luis Potosí | 7.01 | 34.2 |

| Nuevo León | 6.02 | 36.3 |

| Tabasco | 8.10 | 37.7 |

| Morelos | 7.49 | 37.9 |

| Yucatán | 5.85 | 38.3 |

| Nayarit | 7.67 | 42.1 |

| Campeche | 7.28 | 43.4 |

| Michoacán | 6.30 | 44.8 |

| Hidalgo | 6.60 | 45.4 |

| Chihuahua | 7.29 | 45.6 |

| Puebla | 5.69 | 49.9 |

| Tlaxcala | 8.12 | 55.2 |

| Veracruz | 5.56 | 63.8 |

| Oaxaca | 6.01 | 66.0 |

| State of Mexico | 5.03 | 72.4 |

| Chiapas | 6.90 | 78.3 |

| Guerrero | 6.17 | 83.3 |

Includes all ICD‐10 codes O00‐O08.

Number of abortions × 1000 women 15–49 years. Includes all abortions attended in hospitals, emergency rooms, primary health centers. Source: Official database of all public health systems.

Number of abortion deaths × 100 000 abortion cases. Source: INEGI/SSA, DGIS: Cubos dinámicos de información en mortalidad, 2000–2016.

Abortion caused 7.2% of all maternal deaths across Mexico between 1990 and 2008. Mean abortion mortality rate (AMR) decreased over that period, but with great differentials between the most and least marginalized states.23

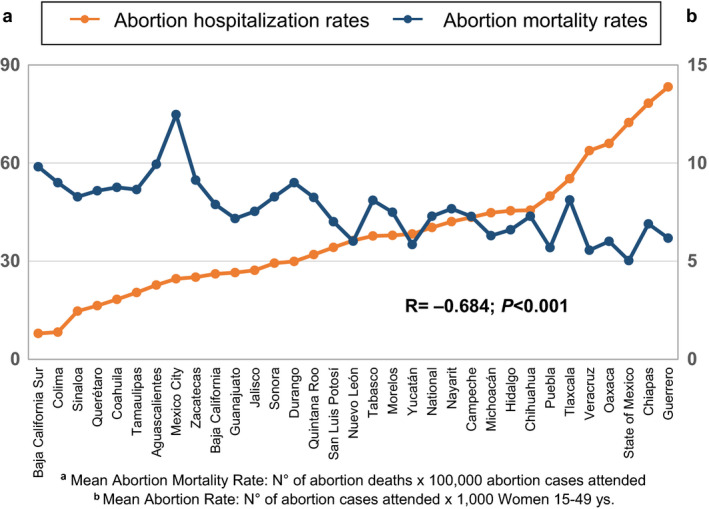

The updated analysis of abortion mortality reports a mean of 82 deaths per year between 2000 and 2016, with no decrease in absolute numbers. However, mean national AMR confirms the previous decreasing trend, from 52.6 deaths per 100 000 abortions attended in the health services in 2000 to 32.5 per 100 000 abortions in 2016, despite no significant legal changes in 31 of 32 states. Comparing abortion hospitalization and mortality rates by federal entities, the risk of death appears significantly lower in states where women have wider access to hospital care24 (Table 11 and Fig. 11).

Figure 1.

Abortion hospitalization rates and abortion mortality rates by federal entities, Mexico 2000–2016. Includes all ICD‐10 codes O00‐O08. Includes all abortions attended in hospitals, emergency rooms, and primary health centers. Source: aOfficial database of all public health systems; bINEGI/SSA, DGIS: Cubos dinámicos de información en mortalidad, 2000–2016.

While variations among states reflect different marginalization contexts that impact overall maternal mortality, they also suggest diverse grades of abortion unsafety, differential access to drugs (misoprostol), to trained providers, and to treatment of complications, as well as diverse severity of social stigma and fear of legal persecution.5, 25

These data are aligned with other studies, which also show a decreasing trend in unsafe abortion mortality at international and regional level.26, 27

3.1.2. Decriminalization of abortion law and morbidity and mortality in Mexico City

A long history involving civil society, academic leaders, and progressive legislators marked the efforts to change the extremely restricted abortion law in the capital city and to allow wider access to services. In 2000, a change in the law (Ley Robles) added new legal exceptions (fetal malformations and risk to a woman's health) to the few existing ones—rape and risk to a woman's life. Subsequent local health regulations established that termination of pregnancy was to be performed in hospitals (with at least 30 beds), or in institutions with basic surgical capacities, by health professionals, “preferably” specialized physicians (obstetrician/gynecologists) or surgeons.28 However, implementation remained a challenge, with only 10 procedures performed each year, mainly as a result of rape.29

A major step forward for abortion access was decriminalization of first‐trimester abortion on a woman's request in Mexico City, in April 200730 (in September 2019, first‐trimester abortion on a woman’s request was also made legal in the State of Oaxaca). Immediately after, new technical guidelines were issued and the legal termination of pregnancy (ILE) program was implemented in the public health sector.31 In the first year following decriminalization, more than 7000 legal first‐trimester abortions were performed; capacity, efficiency, and quality improved rapidly. Over the following years, the ILE program issued new guidelines and expanded services, from hospital‐only to highly equipped health centers, for a total of 14 hospitals/clinics in Mexico City.29 During the first months, approximately one‐third of procedures used sharp curettage, but this technique was soon abandoned for safer surgical (manual or electrical vacuum aspiration: MVA/EVA) and medical abortion options. While misoprostol alone was used at the beginning of the program, after the health registration of mifepristone and its inclusion in the Essential Drugs List in 2011, the combined regimen became the gold standard for medical abortion, with home administration of misoprostol.32

Between April 2007 and September 2019, a total of 216 755 women were served in ILE public services: 77.4% of procedures were performed with medical abortion and 21.2% with MVA or EVA. The large shift toward medical abortion played a major role in meeting women's high demand, simplifying the procedure, and reducing the risk of complications. This shift was also possible because 86% of women requested the services within the first 9 weeks.33 However, technical guidelines maintained similar requirements for medical as for surgical procedures, in terms of clinical infrastructure and type of health professionals.

Analysis of official databases for all abortion services in the whole public health sector in Mexico City shows that numbers and rates of abortions were already higher than the rest of the country before the change in the law, but trends over time were similar to national tendency. In 2000, the abortion rate was 8.8 per 1000 women aged 15–44 years and after legalization the rate doubled to 17 abortions per 1000 women in 2011. The rate leveled off to 14.5 abortion cases per 1000 women in 2016.24 Between 2007 and 2016, legal termination of pregnancy represented approximately 65% of all abortions attended in public hospitals and clinics in Mexico City among women of reproductive age; of these, roughly 30% came from outside the capital. However, disparities in access to legal abortion persist, particularly client‐related barriers, such as young age, low education, lack of knowledge, as well as difficulties in legal and geographical access.34, 35

In parallel, the literature documented a growing number and diversity of providers in the health sector,18, 19 as well as increasing access to self‐induced medical abortion via misoprostol in pharmacies, even after decriminalization.36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41 Additionally, legal abortion soon became available in the private sector.42

In line with increased numbers and rates of services, legal changes also had an impact on all abortion mortality in Mexico City: while the AMR increased between 2000 and 2007 (from 23.6 to 49 deaths per 100 000 abortions attended), it sharply declined after decriminalization and implementation of the ILE program, to an historic low of 12.2 per 100 000 procedures in 2015.25 Our results are consistent with those published by other researchers.5 Moreover, there were no deaths out of the 216 755 first‐trimester legal procedures that were performed in public services as of September 2019. Mexico City's legal abortion mortality rate is thus comparable with international standards, where it is less than one death (0.6) per 100 000 abortions43, 44, 45 (Table 22). These results strongly support the hypothesis that abortion‐related mortality is lowest where access to postabortion care and particularly to legal abortion care is highest, contrary to some published literature.46, 47

Table 2.

Legal abortion case fatality rates

3.2. Task‐sharing and task‐shifting in abortion care in Mexico

3.2.1. Review of normative and legal framework

Mexico was one of the five Latin American countries that participated in The State of the World Midwifery (SoW 2014) report that surveyed availability, needs, and opportunities for task‐shifting and task‐sharing, as well as competencies and functions provided by nonmedical personnel in sexual, reproductive, maternal, and neonatal care (SRMNC).48 The strategy aims to improve overall maternal and neonatal health outcomes, reduce mortality, guarantee availability of and universal access to skilled birth attendants (SBAs), and improve technical and human quality of care, reducing over‐medicalization and unnecessary, potentially harmful practices during delivery.

Following local dissemination of the report49 and according to international and national evidence and recommendations,50, 51 a novel alliance formed in Mexico in recent years, including federal and state MoHs, UNFPA, PAHO, academic and educational institutions, professional associations, groups of traditional and professional midwives, as well as civil society organizations, supported and coordinated by private Foundations. This alliance aspires to develop an integrated task‐sharing and task‐shifting strategy, strengthening obstetric nurses and professional midwives’ roles within a country‐specific “midwifery model”.52

However, this national strategy has focused mainly on pregnancy and childbirth care, leaving out important competencies such as legal abortion and postabortion care. In Mexico, as in most countries surveyed in the SoW2014, surgical treatment of abortion by MVA was the second least available of the seven basic emergency obstetric and newborn care (BEmONC) signal functions, either because it was not allowed or, even if permitted, it was not performed. Interestingly, availability and competency of midwives and nurses’ provision of medical abortion was not evaluated.48

Mexico shares with most countries in the region a general shortage and ill‐distribution of health professionals but, contrary to similar countries, also suffers from a high unmet need of midlevel providers: ratios of physicians to nurses and of nurses to the general population are among the lowest in the region.53 This shortage may particularly affect abortion providers, both in more and in less restricted legal circumstances. Two main cadres of midlevel workforce perform maternal and reproductive health tasks: nurses and midwives. Professional nurses graduate from nursing schools and/or from postgraduate perinatal/obstetric specialization schools: overall 16 200 professional nurses were reported in the SoW2014. Auxiliary nurses—the vast majority of this workforce—are trained through public and private technical diplomats. Professional midwives are extremely scarce in Mexico: only 78 were counted in 2012 for SoW2014; they attend midwifery schools to become technical midwives (equivalent to technical high school), professional midwives (equivalent to university degree), or empirical midwives, under mentoring models. Finally, traditional midwifery is widespread in Mexican regions with a significant indigenous population: by 2012, there were approximately 23 000 in the whole country.48 Thanks to most recent efforts, by 2018, six midwifery schools were identified; 255 professional midwives were counted and a 250% increase in students (from 283 in 2015 to 750 in 2018) of either nursing or midwifery schools was reported.54

According to this situational diagnosis, the federal MoH National Center for Gender Equity and Reproductive Health (CNEGySR) invested specifically in professional nurses, designing new educational curricula, generating regulatory efforts for their certification and full professional accreditation, as well as allocating funds to hire them in several states. A few legal and normative novel frameworks were also published to support this national task‐sharing and task‐shifting strategy. Two partial landmarks are noted here. The updated Official Mexican Norm NOM‐007 states that normal, low‐risk pregnancies and term births can be attended by trained, nonmedical health professionals, including nurses, and professional and traditional midwives.55 Unfortunately, this norm only applies to “normal” pregnancy and does not cover abortion care, not even in first‐trimester uncomplicated events.

Another potential landmark advance is the modification of the General Health Law, that allows nurses to prescribe, in the absence of physicians, medications included in the Essential Drugs List.56 However, later regulations strictly and arbitrarily limit the type and number of drugs that nurses may prescribe: no oxytocics and only four drugs in gynecologic practice.57 An additional opportunity is the pending update of NOM‐019, which regulates tasks, roles, and competencies of nurses within the health system, and can hopefully bring significant advances in the field.58

Global evidence shows women's high acceptance of midlevel providers’ role in the provision of abortion care, particularly for medical regimens.59, 60, 61, 62 To further generate local evidence, a clinical study was conducted in Mexico City ILE clinics. Results suggested that nurses trained to provide medical abortion were equivalent to physicians, in terms of safety, effectiveness, and acceptability of the procedure.63

Despite international recommendations,2, 3, 50, 64 local evidence, and persistent advocacy efforts, no major advances have been achieved in federal norms regulating provision of legal and postabortion care. Official regulatory bodies still establish that only physicians, general practitioners or ob/gyns, and general surgeons, can perform abortions, and this includes both medical and surgical procedures. Judicial approval is no longer required for legal abortion in cases of rape, but the norm still ratifies that it must be carried out in hospitals by trained physicians.10

In Mexico City, technical guidelines for the ILE program shifted over time, from the initial hospital‐based care provided by specialist physicians (ob/gyns or surgeons) to a first level of care provided by general practitioners. Clinical protocols establish preferential use of medical regimens up to 9–10 gestational weeks, with home administration of misoprostol.65 In this model of care, assessing clinical eligibility such as gestational age, prescribing drugs (mifepristone, misoprostol, and analgesics), as well as performing MVA are still formally reserved to physicians. Ultrasound is also a physician's task, but extensive training has been conducted among nurses. Nurses do play an essential role and oversee different functions, from preprocedure counseling to postprocedure family planning provision. However, no advance has been achieved to formally strengthen tasks and functions of nonmedical health professionals in this process of care. A last attempt to update ILE technical guidelines to include “trained midlevel providers” into the cadre of authorized health professionals in 2018 was unsuccessful.

3.2.2. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices: Experts’ interviews

Interviews with the diverse cadres of informants added important information on how they perceive midlevel providers’ roles in SRMNH care in general, and particularly in abortion care, how much they know, and how they interpret and apply present norms and regulations related to this strategy in Mexico.

All health authorities and stakeholders interviewed generally recognize and praise the substantial role that nurses, and increasingly midwives, play in the provision of health services, since midlevel providers are charged with the bulk of these processes and are believed to provide greater technical and interpersonal (“calidad y calidez”) quality of care.

However, the expert interviews confirmed the main findings of laws and norms that were reviewed. The central discussion focused on how to successfully implement task‐sharing and shifting, to improve professional midwives and obstetric nurses’ role in the provision of SRMNHC, particularly around normal, respectful, and “humanized” delivery. However, when specifically inquiring about the provision of postabortion and legal abortion services, we invariably found that this task was hidden or frankly opposed. Abortion care is often perceived as a potential obstacle for the implementation of a task‐sharing/shifting model. According to a Federal MoH authority: “If it is difficult to move forward with this issue of midwifery in general, just imagine if we add the issue of abortion, the additional resistance we will face.”

During the interviews, federal health authorities confirmed a limited interpretation of NOM‐007.55 They consistently described abortion (both induced and spontaneous) as a severe “pathology,” a “complication” of normal pregnancy, charged with clandestine, illegal, and dangerous connotations that accordingly require care in higher level facilities by specialized providers. Even among interviewees who favor the midwifery model, including midlevel providers themselves, these perceptions prevent abortion care from being normalized as a common reproductive health service, whether it is for an uncomplicated spontaneous abortion, an incomplete abortion and more so, a legal procedure. Given that abortion after rape is permitted in the 32 Mexican states, all pregnancy and maternity health services should have the duty and the ability to proactively inform and timely refer women who could require the procedure. This is a huge lost opportunity in the present delivery of services, that could be filled by a more active counselling and referral role of midlevel providers, as mentioned by some interviewees. Finally, we detected attitudinal problems and abortion‐related stigma among many midwives/nurses. As one midwife stated: “We were NOT made to take life away, we were meant to take care of life.” Conscientious objection could therefore constitute a barrier to provision of legal services among nonmedical providers as it does among medical providers.

Contrary to federal stakeholders, Mexico City health authorities and staff with more than 10 years’ experience in the legal abortion program strongly support task‐shifting and sharing among professional cadres, migrating services at the lowest possible level of complexity, both for legal abortion and for treatment of uncomplicated spontaneous abortions. Nurses are considered by these stakeholders as key elements in the ILE program, particularly for providing medical abortion and postabortion contraception. However, they are constrained by legal and normative frameworks dictated at federal level and have been unable to change the local guidelines to include midlevel providers for legal and postabortion care.

Current regulations have severely limited the cadre of legal abortion providers even in private services, in theory to ensure quality of provision of services but mainly to prevent potential liabilities before the regulatory bodies. Private providers additionally mentioned the high turnover among nurses, even greater than among doctors, which discourages training of these human resources. A skilled nurse is a precious human resource in the private market, even if salaries, both in the public and the private health system, are not particularly rewarding.

Both in the public and private sector, absence of regulations is perceived as a bottleneck, both for provision of legal abortion and for inclusion of nonmedical providers; however, when regulations ensue, they usually engender additional restrictions. Hyper‐regulations and barriers are often due to well‐intentioned but uneducated efforts to ensure the safest possible conditions of care, usually to avoid complications but also potential liability issues. However, it must be reminded that the single most important variable that increases the risk of complication is gestational age: every additional week, even in early gestation, doubles the risk for morbidity and mortality.43, 44, 45

Additional challenges and barriers identified during the interviews include the current shortage of professional nurses, and particularly midwives, despite the opening of new schools during the last 3 years; the difficulty of providing clinical fields for hands‐on practice; the absence of professional job descriptions for hiring this personnel into the public system; and finally, the general resistance to inclusion of midlevel providers among the medical community.54

4. Discussion

Abortion in Mexico is a frequent reproductive event in women's lives, and restrictive laws are not effective in preventing it. Increasing hospitalization numbers and rates in recent decades may reflect greater incidence of abortion due to persistently high unmet contraceptive needs in our country—a trend similar to Latin America.66 However, they may also reflect increased access to health services for treatment of complicated and uncomplicated cases, as abortion becomes “less unsafe,” according to recent international and regional trends.17 Abortion mortality, as a result, has decreased overall in Mexico, even in persistently restricted settings. This is most likely related to the widespread knowledge and use of misoprostol, inside and outside the formal health systems, in the hands of a growing and diverse cadre of providers, as well as in the hands of women themselves.39, 40 A similar impact has been documented in other Latin American countries.67, 68, 69

However, both use of services (hospitalizations) and safety of procedures (mortality) continue to show unequal patterns among states, particularly comparing Mexico City with the rest of the country.21, 24 Only where the law allows full legal access to safe services, such as in the capital after 2007, does access to abortion services steeply increase and mortality sharply decline, rapidly reaching rates comparable to international standards. A liberal law—and its wide implementation—is the strongest equalizer in terms of women's right to decide and in terms of public health indicators. In addition, availability of safe technologies, particularly drugs such as mifepristone and misoprostol, is critical in determining access to and quality of abortion care.

Task‐sharing and task‐shifting have been shown to be effective and acceptable interventions to increase safe abortion access and quality in many countries; however, whether nonmedical abortion providers have contributed to increased abortion safety in Mexico is still unclear. Task‐sharing/shifting in SRMNHC in Mexico has vigorously started, but requires support, coordination, leadership, and team working during the next years to overcome barriers and bottlenecks. The main regulatory and structural barriers are common to provision of all reproductive and maternal health services, but some are specific to safe and legal abortion care. In addition to restrictive or ambiguous regulations, other types of barriers were detected, such as negative attitudes and stigma, both among health authorities, stakeholders, and midwives/nurses themselves. Stigma is rooted in ideological and religious values, but also in lack of awareness and technical misperception. Abortion is conceived as an “additional obstacle” to the implementation of task‐sharing/shifting strategies in reproductive and maternal health. It is also considered a “complication” and a high‐risk practice independently of the conditions under which it is performed, ignoring the risks that unintended or even forced gestation and delivery pose to girls, adolescents, and women.43, 44

Despite these challenges, opportunities were mentioned by our interviewees. Efforts should focus on identifying the diverse training and skills nurses and midwives presently have, improving educational curricula, expanding theoretical knowledge, and strengthening clinical competencies in the provision of abortion services, whether in restricted or widely permitted contexts. Accordingly, accreditation and certification processes of various cadres of nonmedical health personnel should be conducted, based on international standards, to facilitate their full, dignified—and adequately remunerated—inclusion in the health system. In all cases, it is essential to work on values clarification and attitude transformation to reduce existing stigma and prejudices toward abortion.

A comprehensive strategy to improve reproductive health care is needed, women‐centered and based on the continuum of care model: from preventing an unplanned pregnancy with effective contraception, to supporting a woman in the case of gestational loss, to providing a legal abortion when pregnancy is unwanted, forced, or when it poses a serious health risk, up to assisting a normal delivery and giving newborn care. Midlevel providers can add a human rights, gender, and multicultural perspective that medical models often forget to include. They can and should offer information, counseling, and referral, but also provide safely induced abortion when adequately trained. Early medical abortion represents a specific opportunity for task‐sharing owing to its simplicity and safety. Current and future regulatory frameworks must provide legal protections versus liabilities and should be designed to accommodate old and new tasks and practices. The International Confederation of Midwives should work to sustain this comprehensive list of tasks and competencies.70, 71

Finally, a change of focus is needed, from the health personnel who perform the task—in this specific case, the abortion—to the skills s/he possesses to carry out a safe procedure, in adherence to international standards. The discussion should shift from the “cadre” to the “competency,” and from the individual to the team, so that all members work in coordination among them and between the different levels of care in functional and integral health networks. Such a team‐building perspective with common achievable goals has the potential to overcome some of the conflicts and competitions among health professionals, between physicians and nonphysicians, but also among diverse cadres of nonmedical providers.

A clear, overt strategic definition by international, regional, and national health bodies and national stakeholders and health authorities is required to give country support to these strategies, according to Mexico's international and regional commitments. This agenda has the potential to expand the equitable access to health services, via, among others, highly competent human health resources.

The change of government at the end of 2018 in Mexico is a window of opportunity for both the full legalization of abortion and for the wider incorporation of nonmedical health professionals (nurses and midwives) in the provision of sexual, reproductive, and maternal health services, including legal abortion, with an emphasis on primary health care, toward universal and equal access for all.

Author Contributions

RS conceived the design, planning, structure, and content of this study in Mexico, conducted interviews, supervised the data analysis, and wrote the manuscript. ET collaborated with identifying and reviewing materials, with conducting interviews and redacting reports, and supported data analysis and manuscript writing.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the UNDP‐UNFPA‐UNICEF‐WHO‐World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP), a cosponsored programme executed by the World Health Organization (WHO). Additional financial support came from the Society of Family Planning Research Fund (SFPRF11‐02), to support public health data collection and analysis. The authors acknowledge and thank the following people: Annik Sorahindo and Bela Ganatra, for the original design, advice, and close supervision of this multicountry study; Gerardo Polo, Evelyn Fuentes‐Rivera, and Blair Darney for their help in public health data collection and analysis, as well as all stakeholders, health authorities, and health personnel who kindly participated in the interviews and provided their informed opinions. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the decisions, policy, or views of the World Health Organization.

References

- 1. SURE Guides for Preparing and Using Evidence‐Based Policy Briefs: 5. Identifying and addressing barriers to implementing policy options. Version 2.1, updated November 2011. The SURE Collaboration; 2011.

- 2. Sorahindo AM, Morris JL. SERAH: Supporting Expanded Roles for safe Abortion care by Health workers – A working group to enable the implementation of the WHO guidelines for expanded roles of health workers in safe abortion and postabortion care. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2016;134:1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Glenton C, Sorhaindo AM, Ganatra B, Lewin S. Implementation considerations when expanding health worker roles to include safe abortion care: A five‐country case study synthesis. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Information Group in Elected Reproduction . Legal exceptions to abortion in state penal codes. Interactive consultation platform [in Spanish]. https://gire.org.mx/consultations/causales-de-aborto-en-codigos-penales-estatales/?type = . Accessed April 5, 2019.

- 5. Clarke D, Mühlrad H. Abortion Laws and Women's Health. IZA Discussion Papers 10890, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA), Oct. 2018. http://ftp.iza.org/dp11890.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2019.

- 6. World Health Organization . Global Abortion Policies Database. Country profile: Mexico. 2019. https://abortion-policies.srhr.org/country/mexico/. Accessed September 6, 2019.

- 7. Information Group in Elected Reproduction . Paulina, justice through the international route. 2008. [in Spanish]. https://gire.org.mx/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/PaulinaJusticia_TD6.pdf. Accessed October 3, 2019.

- 8. Official Federation Diary October 20, 1999. Official Mexican Norm 190‐SSA1-1999. Provision of health services. Criteria for health care of family violence [in Spanish] http://www.salud.gob.mx/unidades/cdi/nom/190ssa19.html. Accessed July 30, 2019.

- 9. Official Federation Diary March 24, 2016. Official Mexican Norm 046‐SSA2-2005. Family and sexual violence and violence against women. Criteria for prevention and care [in Spanish]. http://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5430957&fecha=24/03/2016. Accessed July 30, 2019.

- 10. Clinical Practice Guideline . Screening and care of intimate partner and sexual violence, in the first and second level of care. Mexico Ministry of Health 2010. [in Spanish] https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/267956/Guia_de_practica_clinica_atencionViolencia.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2019.

- 11. World Health Organization . Safe Abortion: Technical and Policy Guidance for Health Systems. Geneva: WHO; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Juárez F, Singh S, Maddow‐Zimet I. Unintended Pregnancy and Induced Abortion in Mexico: Causes and Consequences. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Singh S, Prado E, Juarez F. The Abortion Incidence Complications Method: A Quantitative Technique In: Singh S, Remez L, Tartaglione A, eds. Methodologies for Estimating Abortion Incidence and Abortion‐Related Morbidity: A Review. Guttmacher Institute, IUSSP: New York and Paris; 2010:71–97. [Google Scholar]

- 14. World Health Organization . Unsafe Abortion: Global and Regional Estimates of Incidence of Unsafe Abortion and Associated Mortality in 2008, 6th edn Geneva: WHO; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15. World Health Organization . Unsafe abortion incidence and mortality. Global and regional levels in 2008 and trends during 1990–2008. Geneva: WHO; 2012. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/75173/WHO_RHR_12.01_eng.pdf;sequence=1. Accessed July 30, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ganatra B, Tunçalp Ö, Johnston HB, Johnson BR, Gülmezoglu A, Temmerman M. From concept to measurement: Operationalizing WHO's definition of unsafe abortion. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92:155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ganatra B, Gerdts C, Rossier C, et al. Global, regional, and subregional classification of abortions by safety, 2010–14: Estimates from a Bayesian hierarchical model. Lancet. 2017;390:2372–2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Juárez F, Singh S, Garcia SG, Diaz‐Olavarrieta C. Estimates of induced abortion in Mexico: What's changed between 1990 and 2006? Int Fam Plann Perspect. 2008;34:158–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Juárez F, Singh S. Incidence of induced abortion by age and state, Mexico, 2009: New estimates using a modified methodology. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2012;38:58–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schiavon R, Troncoso E, Polo G. Use of Health System Data to Study Morbidity Related to Pregnancy Loss In: Singh S, Remez L, Tartaglione A, eds. Methodologies for Estimating Abortion Incidence and Abortion‐Related Morbidity and Mortality: A Review. New York and Paris: Guttmacher Institute, IUSSP; 2010:147–163. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Singh S, Maddow‐Zimet I. Facility‐based treatment for medical complications resulting from unsafe pregnancy termination in the developing world, 2012: A review of evidence from 26 countries. BJOG. 2015;123:489–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schiavon R, Fuentes‐Rivera E, Polo G, Saavedra‐Avendano B, Darney BG. State‐ and health system‐level variation in utilization of in‐facility abortion services Mexico 2000‐2016. Poster presented at 13th FIAPAC Conference, Liberating women – Removing barriers and increasing access to safe abortion care, September 14‐15, 2018, Nantes, France. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schiavon R, Troncoso E, Polo G. Analysis of maternal and abortion‐related mortality in Mexico in the last two decades, 1990–2008. Int J Obst Gynecol. 2012;118(Suppl.2):S78–S86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schiavon R, Darney BG, Saavedra B, Polo G, Fuentes‐Rivera E. With and without the law: what's happening with abortion in Mexico? Abstract 5754, Oral presentation, presented at XXII FIGO 2018 Congress, October 14‐19, 2018, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sousa A, Lozano R, Gakidou E. Exploring the determinants of unsafe abortion: Improving the evidence base in Mexico. Health Policy Plan. 2010;25:300–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ǻhman E, Shah IH. New estimates and trends regarding unsafe abortion mortality. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2011;115:121–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, et al. Global causes of maternal death: A WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2:e323–e333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Official Diary of Federal District . General guidelines for the organization and operation of the health services related to termination of pregnancy in the Federal District. Health circular 01/06. November 15, 2006. [in Spanish]. http://www.ordenjuridico.gob.mx/Documentos/Eliminados/wo28823.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2019.

- 29. Becker D, Diaz‐Olavarrieta C. Decriminalization of abortion in Mexico City: The effects on women's reproductive rights. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:590–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Official Diary of Federal District . Decree by which the Federal District penal code is reformed and the Health Law is updated. April 26, 2007. [in Spanish]. http://www.sideso.cdmx.gob.mx/documentos/legislacion/leyes/GacetaAbortoabril07_26_70.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2019.

- 31. Official Diary of Federal District . Agreement that reforms, updates and repeals diverse points of the Ministry of Health circular/gdf-ssdf/01/06 on general guidelines for organization and operation of the health services related to legal termination of pregnancy in the Federal District. May 4, 2007. [in Spanish]. http://data.consejeria.cdmx.gob.mx/portal_old/uploads/gacetas/mayo07_04_75.pdf Accessed May 12, 2016

- 32. Official Diary of Federal District . Notice to inform about the Second Update of Essential and Institutional Drug List of Federal District Ministry of Health August 16, 2011. [in Spanish]. http://www.ordenjuridico.gob.mx/Documentos/Estatal/Distrito%20Federal/wo64068.pdf. Accessed May12, 2019.

- 33. Mexico City Ministry of Health . Legal Termination of Pregnancy. Statistics April 2007‐September 2019. [in Spanish]. http://ile.salud.cdmx.gob.mx/wp-content/uploads/Interrupcion-Legal-del-Embarazo-Estadisticas-2007-2017-26-de-septiembre-2019.pdf. Accessed October 3, 2019.

- 34. Saavedra‐Avendano B, Schiavon R, Sanhueza P, Rios‐Polanco R, Garcia‐Martinez L, Darney BG. Who presents past the gestational age limit for first trimester abortion in the public sector in Mexico City? PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0192547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Friedman J, Saavedra‐Avendaño B, Schiavon R, et al. Quantifying disparities in access to public‐sector abortion based on legislative differences within the Mexico City metropolitan area. Contraception. 2019;99:160–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Billings DL, Walker DL, Mainero dPG, Clark KA, Dayananda I. Pharmacy worker practices related to use of misoprostol for abortion in one Mexican state. Contraception. 2009;79:445–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lara D, Abuabara K, Grossman D, Díaz‐Olavarrieta C. Pharmacy provision of medical abortifacients in a Latin American city. Contraception. 2006;74:394–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lara D, García SG, Wilson KS, Paz F. How often and under which circumstances do Mexican pharmacy vendors recommend misoprostol to induce an abortion? Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2011;37:75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wilson KS, Garcia SG, Lara D. Misoprostol use and its impact on measuring abortion incidence and morbidity In: Singh S, Remez L, Tartaglione A, eds. Methodologies for Estimating Abortion Incidence and Abortion‐Related Morbidity: A Review. Guttmacher Institute, IUSSP: New York and Paris; 2010:191–204. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Schiavon R, Collado ME, Quintanilla L, Reyes ME. Survey on factors related to misoprostol sales in pharmacies of Federal District. Final Investigation Report [in Spanish]. Ipas México. Mexico, DF December, 2015.

- 41. Weaver WG, Schiavon R, Kung S, Collado ME, Darney BG. Misoprostol Distribution and Knowledge in Mexico City: A Survey of Pharmacy Staff. Poster presented at the North American Forum on Family Planning, October 20‐22, 2018, New Orleans, Louisiana. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schiavon R, Collado ME, Troncoso E, Soto Sánchez JE, Zorrilla Otero G, Palermo T. Characteristics of private abortion services in Mexico City after legalization. Reprod Health Matters. 2010;18:127–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Raymond EG, Grimes DA. The comparative safety of legal induced abortion and childbirth in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(2 Pt 1):215–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Grimes DA. Estimation of pregnancy‐related mortality risk by pregnancy outcome, United States, 1991 to 1999. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:92–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . Consensus Study Report. The Safety and Quality of Abortion Care in the United States. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Koch E, Chireau M, Pliego F, et al. Abortion legislation, maternal healthcare, fertility, female literacy, sanitation, violence against women and maternal deaths: A natural experiment in 32 Mexican states. BMJ Open. 2015;5:1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Guttmacher Advisory . Review of a Study by Koch et al. on the Impact of Abortion Restrictions on Maternal Mortality in Chile. May 2012. https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/article_files/guttmacher-advisory.2012.05.23.pdf Accessed May 12, 2019

- 48. UNFPA, International Confederation of midwives, World Health Organization . The State of the World's Midwifery 2014. A Universal Pathway. A Woman's Right to Health. New York, NY: UNFPA; 2014. https://www.unfpa.org/sowmy; Accessed May 12, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 49. The World State of Midwifery 2014. Opportunities and challenges for Mexico. Panamerican Health Organization/World Health Organization/Safe Motherhood Committee in Mexico/UNFPA Mexico City, Mexico 2014. https://issuu.com/cpmsm/docs/las_parteras_del_mundo-final;. Accessed May 12, 2019.

- 50. World Health Organization . Health Worker Roles in Providing Safe Abortion Care and Post‐Abortion Contraception. Geneva: WHO; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. World Health Organization . Task sharing to improve access to Family Planning/Contraception. Summary Brief. Geneva: WHO; 2017. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259633/WHO-RHR-17.20-eng.pdf?sequence=1 Accessed May 12, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 52. National Institute of Public Health . Framework Project. Integral Midwifery Model [in Spanish]. http://www.modelointegraldeparteria.com/. Accessed September 30, 2019.

- 53. Nigenda G, Magaña‐Valladares L, Ortega‐Altamirano DV. Human resources for health in the context of the health reform in Mexico: Professional education and labour market. Gaceta Médica de México. 2013;149:555–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Atkin LC, Keith‐Brown K, Rees MW, et al. Strengthening Midwifery in Mexico: Evaluation of Progress 2015‐2018. January 2019. Report to the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. https://www.macfound.org/media/files/Strengthening_Midwifery_in_Mexico_Three-year_Progress_Report_Jan_2019.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2019.

- 55. Official Diary of the Federation . Official Mexican Norm 007‐SSA2-2016. For the care of the woman during pregnancy, delivery and puerperium, and of the newly born. April 7, 2016. [in Spanish]. http://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5432289&fecha=07/04/2016. Accessed July 30, 2019

- 56. Official Diary of the Federation . Decree by which an article 28 bis is added to the General Health Law. March 5, 2012. [in Spanish]. http://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/ref/lgs/LGS_ref60_05mar12.pdf Accessed July 30, 2019

- 57. Balseiro‐Almario L, Osuna E, Javier‐Cabrera D. Medication prescription by nursing baccalaureates: Legal accountability implications [In Spanish]. Revista Conamed. 2017;22:145–151. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Official Federation Diary . Mexican Official Norm 019‐SSA3-2013. For the practice of nursing in the National Health System. September 2, 2013. [in Spanish]. http://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5312523&fecha=02/09/2013. Accessed May 12, 2019.

- 59. Warriner IK, Wang D, Huong NT, et al. Can midlevel health‐care providers administer early medical abortion as safely and effectively as doctors? A randomized controlled equivalence trial in Nepal. Lancet. 2011;377:1155–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Berer M. Provision of abortion by mid‐level providers: International policy, practice and perspectives. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:58–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Yarnall J, Swica Y, Winikoff B. Non‐physician clinicians can safely provide first trimester medical abortion. Reprod Health Matters. 2009;17:61–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Renner RM, Brahmi D, Kapp N. Who can provide effective and safe termination of pregnancy care? A systematic review BJOG. 2013;120:23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Díaz‐Olavarieta C, Ganatra B, Sorhaindo A, et al. Nurse versus physician‐provision of early medical abortion in Mexico: A randomized controlled non‐inferiority trial. Bull World Health Organ. 2015;93:249–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ganatra B. Health worker roles in safe abortion care and post‐abortion contraception. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3:e512–e513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Official Diary of Federal District . Agreement that reforms, updates and repeals diverse points of the Ministry of Health circular/GDF-SSDF‐01/06 on general guidelines for organization and operation of the health services related to legal termination of pregnancy in the Federal District, published on November 15, 2006. June 20, 2012. [in Spanish].

- 66. Bearak J, Popinchalk A, Alkema L, Sedgh G. Global, regional, and subregional trends in unintended pregnancy and its outcomes from 1990 to 2014: Estimates from a Bayesian hierarchical model. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6:e380–e389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Faúndes A, Santos LC, Carvalho M, Gras C. Post‐abortion complications after interruption of pregnancy with misoprostol. Adv Contracept. 1996;12:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Miller S, Lechman T, Campbell M, et al. Misoprostol and declining abortion‐related morbidity in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic: A Temporal Association. BJGO. 2005;112:1291–1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Faúndes A. Misoprostol: Life‐saving. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2011;16:57–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Fullerton JT, Thompson JB, Severino R. The International Confederation of Midwives essential competencies for basic midwifery practice. An update study: 2009–2010. Midwifery. 2011;27:399–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Butler MM, Fullerton JT, Aman C. Competence for basic midwifery practice: Updating the ICM essential competencies. Midwifery. 2018;66:168–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]