Abstract

Background

Chemo‐ and radiotherapy for breast cancer (BC) can lead to cardiotoxicity even years after the initial treatment. The pathophysiology behind these late cardiac effects is poorly understood. Therefore, we studied a large panel of biomarkers from different pathophysiological domains in long‐term BC survivors, and compared these to matched controls.

Methods and results

In total 91 biomarkers were measured in 688 subjects: 342 BC survivors stratified either to treatment with chemotherapy ± radiotherapy (n = 170) or radiotherapy alone (n = 172) and matched controls. Mean age was 59 ± 9 years and 65 ± 8 years for women treated with chemotherapy ± radiotherapy and radiotherapy alone, respectively, with a mean time since treatment of 11 ± 5.5 years. No biomarkers were differentially expressed in survivors treated with radiotherapy alone vs. controls (P for all >0.1). In sharp contrast, a total of 19 biomarkers were elevated, relative to controls, in BC survivors treated with chemotherapy ± radiotherapy after correction for multiple comparisons (P <0.05 for all). Network analysis revealed upregulation of pathways relating to collagen degradation and activation of matrix metalloproteinases. Furthermore, several inflammatory biomarkers including growth differentiation factor 15, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, chemokine (C‐X‐C motif) ligand 16, tumour necrosis factor super family member 13b and proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9, elevated in survivors treated with chemotherapy, showed an independent association with lower left ventricular ejection fraction.

Conclusion

Breast cancer survivors treated with chemotherapy ± radiotherapy show a distinct biomarker profile associated with mild cardiac dysfunction even 10 years after treatment. These results suggest that an ongoing pro‐inflammatory state and activation of matrix metalloproteinases following initial treatment with chemotherapy might play a role in the observed cardiac dysfunction in late BC survivors.

Keywords: Cardiotoxicity, Biomarkers, Pathophysiology, Cardio‐oncology

Introduction

Worldwide, breast cancer (BC) is the most common cancer in women. Improved oncological treatment has reduced mortality in patients with BC.1, 2 An unfortunate complication of chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy is the development of cardiotoxicity leading to cardiovascular disease (CVD).1, 2, 3, 4

Yet, the pathophysiological mechanisms leading to cardiotoxicity are poorly understood.3 The effects of oncological treatment depend on the treatment modality used (e.g. radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or both) and dosage received. In the acute phase, treatment with chemotherapy may lead to necrosis, apoptosis and cell loss.3 Agents like doxorubicin can cause oxidative stress by increasing the production of reactive oxygen species.5, 6, 7 Furthermore, treatment can cause damage to endothelial cells and subsequent inflammation, leading to cardiac fibrosis.7

Biomarkers can be useful to study possible pathophysiological changes in disease and following treatment.8, 9, 10 Several studies have shown a predictive association of biomarkers with cardiotoxicity during and right after treatment with chemo‐ and/or radiotherapy.11, 12 A recent study13 found that inflammatory biomarkers were increased in BC survivors >4 years after treatment; however, this study was limited by lack of age‐matched controls and a low number of biomarkers included. Therefore, we studied biomarker profiles in long‐term BC survivors stratified by treatment modality compared to age‐ and primary care physician (PCP) matched controls.

Methods

Study population

This study included BC survivors and age and PCP matched controls from the Breast cancer Long‐term OutCome (BLOC) study, of which design and results have been published previously.14 Between 2013 and 2016, the BLOC study enrolled 350 female early BC survivors, diagnosed ≥5 years ago who were cancer‐free since treatment, and 350 age and PCP matched control women never diagnosed with cancer. Of the 350 survivors of early BC, 175 patients were post‐operatively treated with only radiotherapy and 175 with chemotherapy ± radiotherapy. Biomarker measurements were available in 342 survivors and 346 controls (total 688 participants) of the original study cohort. The medical ethics committee of the University Medical Center Groningen (UMCG) approved this study and all participants gave written informed consent. The study was registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01904331). This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study assessments and biomarker measurements

Data on previous medical history and medication use were collected from electronic patient files from the PCP based on the International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC) codes for cardiovascular risk factors and CVD at time of cross‐sectional measurement and at a time of anti‐cancer treatment. Additional information such as smoking history, alcohol consumption and a family history of CVD were answered by participants through a questionnaire. Furthermore, all participants underwent a physical examination at inclusion, determining blood pressure, body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference. Renal function was assessed by calculation of estimated glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine. Radiotherapy in the Netherlands consists of Linac‐based photon tangential fields up to a dose of 50 Gy with or without a boost. In addition, two‐dimensional echocardiography was performed at the UMCG by experienced blinded staff using the biplane Simpson's method according to the guidelines of the American Society of Echocardiography/European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging.15 Blood samples were drawn before echocardiographic assessment and directly analysed for lipid spectrum, renal function and glucose. Additionally, lithium‐heparin plasma samples were immediately stored at −80° for biomarker assessment.

Biomarker analyses were performed at Olink Bioscience (Uppsala, Sweden) using the Olink Proseek Olink Proseek® Multiplex CVD III I96x96 kit, which measures 92 cardiovascular‐related proteins simultaneously in 1 μL plasma samples.16 The kit is based on a proximity extension assay technology, where 92 oligonucleotide‐labelled antibody pairs are allowed to bind to their respective targets. This technique has a major advantage over conventional multiplex assays, in that only correctly matched antibody pairs provide a signal, giving a very high specificity. Amplicons were quantified using a Fluidigm BioMark™ HD real‐time polymerase chain reaction platform, which provides normalized protein expression data, where a high protein value corresponds to a high protein concentration. The Olink assay uses four built‐in internal controls, providing technical control for each individual sample. In addition, eight external controls including two pooled plasma samples are used to calculate intra‐ and interpolate coefficients of variation for each assay. An overview of disease domains of biomarkers involved is provided in online supplementary Table S1 . Intra‐ and inter‐assay coefficients of variation are reported in online supplementary Table S2 .

Statistical analyses

Baseline characteristics were compared between patients previously treated with chemotherapy ±/or radiotherapy alone and their respective matched controls using Students' t‐test, the Mann–Whitney U test or the Chi‐square test depending on the nature and distribution of the variable. Biomarker profiles between BC survivors and respective controls were compared using logistic regression analyses stratified to treatment modality, correcting for age, BMI, renal function and a diagnosis of CVD in multivariable analyses. Sensitivity analysis was performed by repeating our analyses in subjects who received chemotherapy alone compared to matched controls. To correct for multiple comparisons, we used a false discovery rate of 0.1 using the Benjamini–Hochberg method. We performed sensitivity analyses restricting our analyses only to survivors with a T‐classification of ≥2. We created a general network of human physical protein–protein interaction (PPI) (HsapiensPPI), consisting of 17 625 unique nodes with 330 157 interactions between them based on data from BIND,17 BioGRID,18 DIP,19 HPRD,20 IntAct21 and PDZBase.22 Context‐specific networks were constructed by selecting nodes and interactions that occur only between members from the protein list being investigated (N0 networks) and/or by selecting nodes that indirectly interact, one‐neighbour‐away, with members of the list (N1 networks). Physical cohesiveness of context‐specific networks were assigned using the Physical Interaction Enrichment procedure that corrects for biased enrichment, in general PPI networks, of proteins that are often studied.23 Analysis of PPIs was performed and plotted using Cytoscape version 3.7.0, where the node size corresponds to the betweenness centrality. A larger node size, the more connected the node is in the network. We used the ClueGO app in Cytoscape to investigate over‐represented biological pathways using data from the Gene‐ontology consortium and Reactome.24 Lastly, we investigated the association of biomarkers with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). The association of biomarkers with LVEF was tested using multivariable linear regression analysis, correcting for age, renal function, BMI, history of or current CVD, treatment with anti‐hormonal therapy and treatment with radiotherapy. All analyses were performed using R, version 3.5.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Baseline characteristics

Breast cancer survivors treated with radiotherapy alone had a slightly higher prevalence of diabetes (12% vs. 5%, P = 0.016) compared to controls and were more often on beta‐blockers (19% vs. 11%, P = 0.044) (Table 1). BC survivors treated with chemotherapy ± radiotherapy more often used angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors (19% vs. 11%, P = 0.03), anticoagulants (11% vs. 5%, P = 0.025) and antiplatelet therapy (9% vs. 3%, P = 0.026). Survivors treated with chemotherapy ± radiotherapy had a mean age of 59 years ± 9 years, survivors treated with radiotherapy alone had a mean age of 65 ± 8 years. In the group treated with chemotherapy, 69% received additional radiotherapy. The median cumulative anthracycline doses for the chemotherapy was 238 ( interquartile range 228–240) mg/m2. A total of 108 (63%) survivors treated with chemotherapy ± radiotherapy were also treated with anti‐hormonal therapy, while 38 (22%) of survivors treated with radiotherapy were also treated with anti‐hormonal therapy (Table 1). Mean follow‐up time since treatment was 11 ± 5.5 years. Time since treatment did not differ between survivors treated with radiotherapy alone (11 ± 5 years) and those treated with chemotherapy ± radiotherapy (11 ± 6 years, P = 0.453). N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP) and C‐reactive protein were significantly increased in survivors previously treated with chemotherapy ± radiotherapy compared to controls.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Radiotherapy | Chemotherapy ± radiotherapy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Treated | P‐value | Control | Treated | P‐value | |

| Patients, n | 172 | 170 | 174 | 172 | ||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age (years) | 64.8 (6.9) | 65.2 (7.5) | 0.59 | 59.6 (9.1) | 59.3 (9.2) | 0.71 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.9 (4.8) | 26.9 (5.5) | 0.97 | 25.9 (4.3) | 26.2 (4.0) | 0.52 |

| Time since therapy (years) | – | 11.6 (5.2) | – | 11.3 (5.5) | ||

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 74.1 (13.7) | 74.4 (17.5) | 0.84 | 75.8 (13.3) | 74.3 (14.6) | 0.3 |

| Medical history, n (%) | ||||||

| Hypertension | 61 (35.5) | 60 (35.3) | 0.97 | 42 (24.1) | 46 (26.7) | 0.58 |

| Diabetes | 8 (4.7) | 20 (11.8) | 0.016 | 7 (4.0) | 9 (5.2) | 0.59 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 30 (17.4) | 32 (18.8) | 0.74 | 28 (16.1) | 21 (12.2) | 0.3 |

| Artificial heart valve | 2 (1.2) | 1 (0.6) | 0.57 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 0.31 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 6 (3.5) | 14 (8.2) | 0.061 | 8 (4.6) | 15 (8.7) | 0.12 |

| Heart failure | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.16 | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 0.99 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 4 (2.3 | 6 (3.5) | 0.51 | 1 (0.6) | 4 (2.3) | 0.17 |

| Medication, n (%) | ||||||

| ACE inhibitors | 23 (13.4) | 31 (18.2) | 0.22 | 19 (10.9) | 33 (19.2) | 0.031 |

| Beta‐blockers | 19 (11.0) | 32 (18.8) | 0.044 | 14 (8.0) | 21 (12.2) | 0.2 |

| CCB | 13 (7.6) | 7 (4.1) | 0.18 | 9 (5.2) | 7 (4.1) | 0.63 |

| Diuretics | 26 (15.1) | 18 (10.6) | 0.21 | 12 (6.9) | 13 (7.6) | 0.81 |

| Anticoagulants | 11 (6.4) | 18 (10.6) | 0.16 | 8 (4.6) | 19 (11.0) | 0.025 |

| Antiplatelet therapy | 5 (2.9) | 13 (7.6) | 0.05 | 6 (3.4) | 16 (9.3) | 0.026 |

| Statins | 26 (15.1) | 30 (17.6) | 0.53 | 13 (7.5) | 23 (13.4) | 0.072 |

| Laboratory | ||||||

| HDL‐cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.8 (0.5) | 1.7 (0.4) | 0.038 | 1.8 (0.5) | 1.7 (0.5) | 0.77 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.7 (1.0) | 5.6 (1.1) | 0.73 | 5.6 (1.2) | 5.5 (1.1) | 0.9 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.2 (0.7) | 1.4 (0.8) | 0.13 | 1.3 (0.7) | 1.3 (0.8) | 0.43 |

| LDL‐cholesterol (mmol/L) | 3.5 (1.0) | 3.5 (1.1) | 0.7 | 3.5 (1.1) | 3.4 (1.0) | 0.6 |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 5.6 (1.0) | 5.9 (1.7) | 0.063 | 5.5 (1.0) | 5.5 (1.0) | 0.73 |

| C‐reactive protein (mg/L) | 1.4 [0.8–3.0] | 1.7 [0.9–4.0] | 0.19 | 1.4 [0.8–3.0] | 1.9 [1.0–4.0] | 0.017 |

| NT‐proBNP (pg/mL) | 82.0 [50.5–140.5] | 97.0 [51.0–160.0] | 0.15 | 71.5 [46.0–125.0] | 97.5 [58.0–148.5] | 0.002 |

| Echocardiography | ||||||

| LVEF (%) | 59.0 [57.5–61.5] | 58.0 [55.0–62.0] | 0.11 | 59.0 [57.0–62.0] | 57.5 [55.0–60.0] | <0.001 |

| Systolic dysfunction (LVEF <54%) | 13 (7.7) | 27 (16.3) | 0.016 | 13 (7.5) | 25 (15.0) | 0.029 |

| E′ septal (cm/s) | 7 [6–9] | 7 [6–9] | 0.73 | 8 [7–10] | 8 [6–9] | 0.31 |

| E′ lateral (cm/s) | 10 [8–11] | 9 [7–11] | 0.416 | 10.7 [8.8–12.4] | 10.4 [7.9–12.4] | 0.23 |

| E/e′ | 7.5 [6.4–9.0] | 7.6 [6.6–9.1] | 0.38 | 7.2 [6.1–8.2] | 7.0 [5.9–8.1] | 0.29 |

| Prior treatment | ||||||

| Time since therapy (years) | – | 11.6 (5.2) | – | 11.3 (5.5) | ||

| Anti‐hormonal therapy | 38 (22) | 108 (63) | ||||

| Cumulative anthracycline doses (mg/mL) | – | 238 [228–240] | ||||

| Trastuzumab | 0 (0) | 13 (9) | ||||

| Radiotherapy (%) | 100 | 69 | ||||

| LV mean dose (Gy) | 2 [0.6–6.5] | 1.9 [0.6–6.0] | ||||

Values are given as mean ± standard deviation, n (%), or median [interquartile range].

ACE, angiotensin‐converting enzyme; BMI, body mass index; CCB, calcium channel blocker; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; LV, left ventricular; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; SD, standard deviation.

Biomarkers and pathways

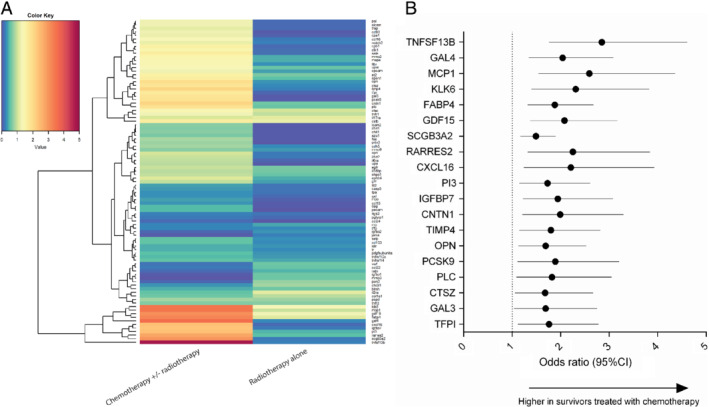

No significant differences were found in biomarker levels between BC survivors treated with radiotherapy alone vs. controls (Figure 1 A). In sharp contrast, 19 biomarkers had significantly higher levels in survivors treated with chemotherapy ± radiotherapy compared to controls (Figure 1 A). After multivariable adjustment for age, BMI, renal function and a diagnosis of CVD, all these 19 biomarkers remained significantly higher in survivors treated with chemotherapy ± radiotherapy compared to controls (Figure 1 B). Further correction for LVEF did not affect these results (P remained <0.05 for all). Biomarker levels were not associated with time since treatment (P > 0.1 for all). When restricting our analyses only to survivors with a T‐classification of ≥2, similar results were observed (online supplementary Table S3 ). No association between the biomarkers and received radiation dose was observed (P for all >0.2). No association between any of the differentially regulated biomarkers and received anthracycline dose was observed.

Figure 1.

(A) Heatmap depicting ‐log10 (P‐value) of biomarker associations with the chemotherapy/radiotherapy and radiotherapy group vs. age‐ and sex‐matched controls. Red signifies P < 0.05 while blue signifies P > 0.05. (B) Forest plot depicting multivariable odds ratios for biomarker levels in survivors treated with chemotherapy ± radiotherapy vs. controls. CI, confidence interval.

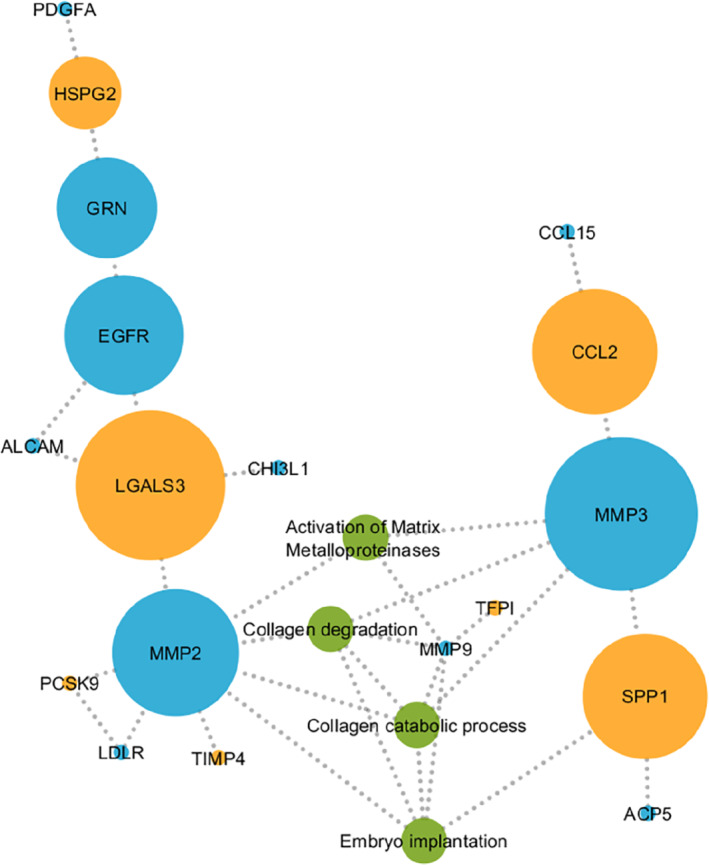

To provide biological context to the proteins found, we performed network analysis and pathway over‐representation analysis (Figure 2). We observed that galectin‐3, osteopontin, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) 2, MMP‐3 and epidermal growth factor receptor were important hubs (larger nodes) within the network. Following pathway over‐representation analysis, we observed that pathways relating to collagen degradation, activation of MMPs and collagen catabolic processes were significantly over‐represented in survivors treated with chemotherapy ± radiotherapy (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Results from network analysis showing protein–protein interactions for empirically identified markers (orange), predicted markers (blue) and associated pathways (green). ACP5, acid phosphatase 5, Tartrate Resistant; ALCAM, activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule; CCL2, chemokine (C‐C motif) ligand 2; CCL15, chemokine (C‐C motif) ligand 15; CHI3L1, chitinase‐3‐like protein 1; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; GRN, granulin; HSPG2, heparan sulfate proteoglycan 2; LDLR, low‐density lipoprotein receptor; LGALS3, galectin‐3; MMP2, matrix metalloproteinase 2; MMP3, matrix metalloproteinase 3; PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9; PDGFA, platelet‐derived growth factor subunit A; SPP1, secreted phosphoprotein 1; TIMP4, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 4.

To exclude the possibility that differentially regulated biomarkers in the chemotherapy ± radiotherapy group were the consequence of the higher prevalence of current and past cardiovascular events, we performed additional sensitivity analyses restricting our analyses to BC survivors without any history of CVD, which did not affect our findings. Secondly, to exclude the possibility that the differentially regulated biomarkers were the consequence of a combination of radiotherapy and chemotherapy, we performed analyses restricting to BC survivors only treated with chemotherapy, which showed similar results (online supplementary Table S4 ).

Association with left ventricular ejection fraction

From the biomarkers that were significantly up‐regulated in survivors treated with chemotherapy ± radiotherapy, higher levels of tumour necrosis factor super family member 13b (TNFSF13B), monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, growth differentiation factor 15, chemokine (C‐X‐C motif) ligand 16, peptidase inhibitor 3, insulin growth factor binding protein 7, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9), osteopontin and perlecan showed a significant association (P for all <0.05) with lower LVEF in the group treated with chemotherapy ± radiotherapy, independent of age, renal function, BMI, history of or current CVD, treatment with anti‐hormonal therapy and treatment with radiotherapy (Table 2). In addition, levels of NT‐proBNP were significantly increased in BC survivors compared to controls, as reported previously.14 Levels of C‐reactive protein were similarly increased; however, in multivariable analyses, both markers were not associated with LVEF in survivors treated with chemotherapy ± radiotherapy.

Table 2.

Association of biomarkers with left ventricular ejection fraction after correction for age, renal function, body mass index, history of or current cardiovascular disease, treatment with anti‐hormonal therapy and treatment with radiotherapy in survivors treated with chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy

| Biomarker | Standardized beta | P‐value |

|---|---|---|

| TNFSF13B | −0.18 | 0.02 |

| Gal4 | −0.11 | 0.184 |

| MCP1 | −0.21 | 0.011 |

| KLK6 | 0.01 | 0.864 |

| FABP4 | −0.2 | 0.033 |

| GDF15 | −0.26 | 0.002 |

| SCGB3A2 | 0.03 | 0.739 |

| RARRES2 | −0.2 | 0.017 |

| CXCL16 | −0.19 | 0.019 |

| PI3 | −0.17 | 0.041 |

| IGFBP7 | −0.18 | 0.026 |

| CNTN1 | −0.15 | 0.06 |

| TIMP4 | −0.08 | 0.294 |

| OPN | −0.16 | 0.04 |

| PCSK9 | −0.16 | 0.041 |

| PLC | −0.21 | 0.011 |

| CTSZ | −0.11 | 0.16 |

| Gal3 | −0.14 | 0.079 |

| TFPI | −0.15 | 0.05 |

CNTN1, contactin‐1; CTSZ, cathepsin Z; CXCL16, Chemokine (C‐X‐C motif) ligand 16; FABP4, fatty acid binding protein 4; Gal3, galectin‐3; Gal4, galectin‐4; GDF15, growth differentiation factor 15; KLK, kallikrein‐6; IGFBP7, insulin‐like growth factor‐binding protein 7; MCP1, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1; OPN, osteopontin; PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9; PI3, peptidase inhibitor 3; PLC, perlecan; RARRES2, retinoic acid receptor responder protein 2; SCGB3A2, secretoglobin family 3A member 2; TFPI, tissue factor pathway inhibitor; TIMP4, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 4; TNFSF13B, tumour necrosis factor super family member 13b.

Discussion

Results of this study show that BC survivors treated with chemotherapy have a distinct biomarker profile even more than 10 years following systemic anti‐cancer treatment. This suggests a potential persistent pro‐inflammatory state in BC survivors following treatment with chemotherapy. This pro‐inflammatory state might be an important risk factor for cardiovascular events in BC survivors previously treated with chemotherapy and is associated with lower LVEF.

This is the first study of its kind studying a large panel of biomarkers in late BC survivors. Previous studies investigated biomarkers during or immediately after treatment.11, 25 Particularly troponin I and T have shown promise in predicting cardiotoxicity following anti‐cancer treatment and suggest that direct cardiac damage might be a causative factor in early onset cardiotoxicity. However, no differences in troponin T levels were observed in the BLOC study between controls and survivors.26, 27, 28 In our study, no significant differences were found between patients treated with radiotherapy alone and controls, even after accounting for differences in disease severity in sensitivity analyses. This may potentially be explained by the relatively low‐dose of radiotherapy received and the modern machines used in administering radiotherapy, which greatly reduce the radiation dosages, and the fact that the heart was often outside of the radiation beam in the BLOC study.29, 30 Furthermore, survivors previously treated with radiotherapy might have less advanced BC, which might be an explanation for the differences in biomarker levels found between patients treated with chemotherapy/radiotherapy vs. controls and those treated only with radiotherapy vs. controls.

In contrast, a considerable number of biomarkers were elevated in BC survivors treated with chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy. These biomarkers were primarily associated with inflammatory pathways and collagen deposition. While no association was observed between biomarkers and received anthracycline dose, this might be confounded by the limited overall variation in dose of anthracyclines received. Scuric et al.13, 31 found that BC survivors treated with chemo‐ and/or radiotherapy had higher markers of cellular aging, including more DNA damage and lower telomerase activity. However, this study only investigated a small number of markers and the time since follow‐up was considerably shorter compared to the BLOC study. These markers of cellular aging were associated with higher levels of pro‐inflammatory cytokines including soluble tumour necrosis factor receptor II and objective measures of cognitive performance. In addition, increases in pro‐inflammatory cytokines during and after anti‐cancer treatment are related to increased fatigue and depression and an important risk factor for future cardiovascular events.32, 33, 34 Pro‐inflammatory and cardiac remodelling markers including growth differentiation factor 15, galectin‐3 and insulin growth factor binding protein 7 are associated with incident cardiovascular events and heart failure.35, 36, 37 Epigenetic imprinting might be responsible for this pro‐inflammatory state – a previous study in BC patients showed that treatment with chemotherapy left an epigenetic imprint leading to increased inflammation. Furthermore, this imprint was associated with symptoms of depression and fatigue long after treatment.38, 39 A separate study performed in 327 individuals showed that among 37 BC survivors with a median time since treatment of 4 years the extracellular volume was increased compared to controls, suggesting greater cardiac fibrosis. Our results showed that pathophysiological processes relating to collagen deposition were up‐regulated. The overall difference in LVEF between survivors and controls was significant, albeit of a relatively small magnitude, as previously reported.14 Furthermore, although we found a significant association between several increased levels of biomarkers and a decreased LVEF, the overall effects were relatively small.

In our study, BC survivors previously treated with chemotherapy showed higher levels of PCSK9. PCSK9 is secreted into plasma by the liver and binds low‐density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor at the surface of hepatocytes. This leads to less recycling of LDL receptors, reducing LDL‐cholesterol clearance. PCSK9 contributes to increased plaque instability through pro‐inflammatory pathways and active oxidation. In patients with heart failure, increased levels of PCSK9 are associated with adverse outcomes.40 Inhibition of PCSK9 stabilizes plaques, decreased LDL‐cholesterol and reduced the risk of cardiovascular events in patients with established CVD.41, 42 Results of our study suggest that PCSK9 might be a potential bio‐target in BC survivors.

Limitations

This study only included women who survived BC for at least 5 years after diagnosis and are therefore perhaps healthier than patients at the time of treatment, therefore the effect of the biomarkers found in this study might be escalated in the direct phase of treatment. While we performed additional sensitivity analyses accounting for differences in cancer severity, residual confounding might have taken place. Biomarker targets found were not independently confirmed using conventional ELISAs. Receptor status was not available for survivors in the BLOC study, which might have confounded our results. Furthermore, the risk for cardiovascular events might have been over‐estimated in the BLOC study due to non‐participation of controls with higher rates of (previous) cardiovascular events. Lastly, the cross‐sectional design and type of analysis used excludes inference of causality.

Conclusion

Long‐term survivors of early BC treated with systemic chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy show increased levels of biomarkers related to inflammation and collagen deposition compared to matched controls. Lastly, many of these biomarkers were associated with cardiac dysfunction, providing a possible functional link between a pro‐inflammatory state in BC survivors and cardiac dysfunction.

Funding

Funding support by Pink Ribbon, Stichting de Friesland, the University of Groningen, the University Medical Center Groningen, and Roche Diagnostics is kindly acknowledged.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Supporting information

Table S1. Disease classification of biomarkers included in the OLINK CVD III assay.

Table S2. Assay information.

Table S3. Sensitivity analyses restricting our analyses only to survivors with a T‐classification of ≥2.

Table S4. Association of biomarkers with survivors treated with chemotherapy alone vs. controls.

References

- 1. Zamorano JL, Lancellotti P, Rodriguez Muñoz D, Aboyans V, Asteggiano R, Galderisi M, Habib G, Lenihan DJ, Lip GY, Lyon AR, Lopez Fernandez T, Mohty D, Piepoli MF, Tamargo J, Torbicki A, Suter TM. 2016 ESC position paper on cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity developed under the auspices of the ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines: The Task Force for Cancer Treatments and Cardiovascular Toxicity of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2016;37:2768–2801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lancellotti P, Suter TM, López‐Fernández T, Galderisi M, Lyon AR, Van der Meer P, Cohen Solal A, Zamorano JL, Jerusalem G, Moonen M, Aboyans V, Bax JJ, Asteggiano R. Cardio‐oncology services: rationale, organization, and implementation. Eur Heart J 2019;40:1756–1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tromp J, Steggink L, Van Veldhuisen D, Gietema J, van der Meer P. Cardio‐oncology: progress in diagnosis and treatment of cardiac dysfunction. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2017;101:481–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Albini A, Pennesi G, Donatelli F, Cammarota R, De Flora S, Noonan DM. Cardiotoxicity of anticancer drugs: the need for cardio‐oncology and cardio‐oncological prevention. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010;102:14–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Van Der Meer P, Gietema JA, Suter TM, Van Velduisen DJ. Cardiotoxicity of breast cancer treatment: no easy solution for an important long‐term problem. Eur Heart J 2016;37:1681–1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Suter TM, Ewer MS. Cancer drugs and the heart: importance and management. Eur Heart J 2013;34:1102–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ewer MS, Ewer SM. Cardiotoxicity of anticancer treatments. Nat Rev Cardiol 2015;12:547–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tromp J, Van Der Pol A, Klip IT, De Boer RA, Jaarsma T, Van Gilst WH, Voors AA, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Van Der Meer P. Fibrosis marker syndecan‐1 and outcome in patients with heart failure with reduced and preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail 2014;7:457–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tromp J, Khan MA, Klip IT, Meyer S, de Boer RA, Jaarsma T, Hillege H, van Veldhuisen DJ, van der Meer P, Voors AA. Biomarker profiles in heart failure patients with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6:e003989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tromp J, Khan MA, Mentz RJ, O'Connor CM, Metra M, Dittrich HC, Ponikowski P, Teerlink JR, Cotter G, Davison B, Cleland JG, Givertz MM, Bloomfield DM, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Hillege HL, Voors AA, van der Meer P. Biomarker profiles of acute heart failure patients with a mid‐range ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail 2017;5:507–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ky B, Putt M, Sawaya H, French B, Januzzi JL, Sebag IA, Plana JC, Cohen V, Banchs J, Carver JR, Wiegers SE, Martin RP, Picard MH, Gerszten RE, Halpern EF, Passeri J, Kuter I, Scherrer‐Crosbie M. Early increases in multiple biomarkers predict subsequent cardiotoxicity in patients with breast cancer treated with doxorubicin, taxanes, and trastuzumab. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:809–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cardinale D, Colombo A, Sandri MT, Lamantia G, Colombo N, Civelli M, Martinelli G, Veglia F, Fiorentini C, Cipolla CM. Prevention of high‐dose chemotherapy‐induced cardiotoxicity in high‐risk patients by angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibition. Circulation 2006;114:2474–2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Scuric Z, Carroll JE, Bower JE, Ramos‐Perlberg S, Petersen L, Esquivel S, Hogan M, Chapman AM, Irwin MR, Breen EC, Ganz PA, Schiestl R. Biomarkers of aging associated with past treatments in breast cancer survivors. NPJ Breast Cancer 2017;3:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Boerman LM, Maass SW, van der Meer P, Gietema JA, Maduro JH, Hummel YM, Berger MY, de Bock GH, Berendsen AJ. Long‐term outcome of cardiac function in a population‐based cohort of breast cancer survivors: a cross‐sectional study. Eur J Cancer 2017;81:56–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor‐Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Goldstein SA, Kuznetsova T, Lancellotti P, Muraru D, Picard MH, Rietzschel ER, Rudski L, Spencer KT, Tsang W, Voigt JU. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2015;16:233–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tromp J, Ouwerkerk W, Demissei BG, Anker SD, Cleland JG, Dickstein K, Filippatos G, Van Der Harst P, Hillege HL, Lang CC, Metra M, Ng LL, Ponikowski P, Samani NJ, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Zannad F, Zwinderman AH, Voors AA, Van Der Meer P. Novel endotypes in heart failure: effects on guideline‐directed medical therapy. Eur Heart J 2018;39:4269–4276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bader GD, Betel D, Hogue CW. BIND: the Biomolecular Interaction Network Database. Nucleic Acids Res 2003;31:248–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stark C, Breitkreutz BJ, Reguly T, Boucher L, Breitkreutz A, Tyers M. BioGRID: a general repository for interaction datasets. Nucleic Acids Res 2006;34:D535–D539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Xenarios I, Rice DW, Salwinski L, Baron MK, Marcotte EM, Eisenberg D. DIP: the Database of Interacting Proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 2000;28:289–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Peri S, Navarro JD, Amanchy R, Kristiansen TZ, Jonnalagadda CK, Surendranath V, Niranjan V, Muthusamy B, Gandhi TK, Gronborg M, Ibarrola N, Deshpande N, Shanker K, Shivashankar HN, Rashmi BP, Ramya MA, Zhao Z, Chandrika KN, Padma N, Harsha HC, Yatish AJ, Kavitha MP, Menezes M, Choudhury DR, Suresh S, Ghosh N, Saravana R, Chandran S, Krishna S, Joy M, Anand SK, Madavan V, Joseph A, Wong GW, Schiemann WP, Constantinescu SN, Huang L, Khosravi‐Far R, Steen H, Tewari M, Ghaffari S, Blobe GC, Dang CV, Garcia JG, Pevsner J, Jensen ON, Roepstorff P, Deshpande KS, Chinnaiyan AM, Hamosh A, Chakravarti A, Pandey A. Development of Human Protein Reference Database as an initial platform for approaching systems biology in humans. Genome Res 2003;13:2363–2371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kerrien S, Aranda B, Breuza L, Bridge A, Broackes‐Carter F, Chen C, Duesbury M, Dumousseau M, Feuermann M, Hinz U, Jandrasits C, Jimenez RC, Khadake J, Mahadevan U, Masson P, Pedruzzi I, Pfeiffenberger E, Porras P, Raghunath A, Roechert B, Orchard S, Hermjakob H. The IntAct Molecular Interaction Database in 2012. Nucleic Acids Res 2012;40:D841–D846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Beuming T, Skrabanek L, Niv MY, Mukherjee P, Weinstein H. PDZBase: a protein‐protein interaction database for PDZ‐domains. Bioinformatics 2005;21:827–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sama IE, Huynen MA. Measuring the physical cohesiveness of proteins using physical interaction enrichment. Bioinformatics 2010;26:2737–2743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bindea G, Mlecnik B, Hackl H, Charoentong P, Tosolini M, Kirilovsky A, Fridman WH, Pagès F, Trajanoski Z, Galon J. ClueGO: a Cytoscape plug‐in to decipher functionally grouped gene ontology and pathway annotation networks. Bioinformatics 2009;25:1091–1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tian S, Hirshfield KM, Jabbour SK, Toppmeyer D, Haffty BG, Khan AJ, Goyal S. Serum biomarkers for the detection of cardiac toxicity after chemotherapy and radiation therapy in breast cancer patients. Front Oncol 2014;4:277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cardinale D, Sandri MT, Martinoni A, Borghini E, Civelli M, Lamantia G, Cinieri S, Martinelli G, Fiorentini C, Cipolla CM. Myocardial injury revealed by plasma troponin I in breast cancer treated with high‐dose chemotherapy. Ann Oncol 2002;13:710–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cardinale D, Colombo A, Torrisi R, Sandri MT, Civelli M, Salvatici M, Lamantia G, Colombo N, Cortinovis S, Dessanai MA, Nolè F, Veglia F, Cipolla CM. Trastuzumab‐induced cardiotoxicity: clinical and prognostic implications of troponin I evaluation. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:3910–3916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cardinale D, Sandri MT, Martinoni A, Tricca A, Civelli M, Lamantia G, Cinieri S, Martinelli G, Cipolla CM, Fiorentini C. Left ventricular dysfunction predicted by early troponin I release after high‐dose chemotherapy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;36:517–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Darby SC, Ewertz M, McGale P, Bennet AM, Blom‐Goldman U, Brønnum D, Correa C, Cutter D, Gagliardi G, Gigante B, Jensen MB, Nisbet A, Peto R, Rahimi K, Taylor C, Hall P. Risk of ischemic heart disease in women after radiotherapy for breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2013;368:987–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Darby SC, McGale P, Taylor CW, Peto R. Long‐term mortality from heart disease and lung cancer after radiotherapy for early breast cancer: prospective cohort study of about 300 000 women in US SEER cancer registries. Lancet Oncol 2005;6:557–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Carroll JE, Van Dyk K, Bower JE, Scuric Z, Petersen L, Schiestl R, Irwin MR, Ganz PA. Cognitive performance in survivors of breast cancer and markers of biological aging. Cancer 2019;125:298–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Collado‐Hidalgo A, Bower JE, Ganz PA, Cole SW, Irwin MR. Inflammatory biomarkers for persistent fatigue in breast cancer survivors. Clin Cancer Res 2006;12:2759–2766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bower JE, Ganz PA, Irwin MR, Kwan L, Breen EC, Cole SW. Inflammation and behavioral symptoms after breast cancer treatment: do fatigue, depression, and sleep disturbance share a common underlying mechanism? J Clin Oncol 2011;29:3517–3522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Willerson JT, Ridker PM. Inflammation as a cardiovascular risk factor. Circulation 2004;109(21 Suppl 1):II2–II10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wollert KC, Kempf T, Wallentin L. Growth differentiation factor 15 as a biomarker in cardiovascular disease. Clin Chem 2017;63:140–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Morrow DA, O'Donoghue ML. Galectin‐3 in cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:1257–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gandhi PU, Gaggin HK, Redfield MM, Chen HH, Stevens SR, Anstrom KJ, Semigran MJ, Liu P, Januzzi JL. Insulin‐like growth factor‐binding protein‐7 as a biomarker of diastolic dysfunction and functional capacity in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail 2016;4:860–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Torres MA, Pace TW, Liu T, Felger JC, Mister D, Doho GH, Kohn JN, Barsevick AM, Long Q, Miller AH. Predictors of depression in breast cancer patients treated with radiation: role of prior chemotherapy and nuclear factor kappa B. Cancer 2013;119:1951–1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Smith AK, Conneely KN, Pace TW, Mister D, Felger JC, Kilaru V, Akel MJ, Vertino PM, Miller AH, Torres MA. Epigenetic changes associated with inflammation in breast cancer patients treated with chemotherapy. Brain Behav Immun 2014;38:227–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bayes‐Genis A, Núñez J, Zannad F, Ferreira JP, Anker SD, Cleland JG, Dickstein K, Filippatos G, Lang CC, Ng LL, Ponikowski P, Samani NJ, van Veldhuisen DJ, Zwinderman AH, Metra M, Lupón J, Voors AA. The PCSK9‐LDL receptor axis and outcomes in heart failure: BIOSTAT‐CHF subanalysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:2128–2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sabatine MS, Leiter LA, Wiviott SD, Giugliano RP, Deedwania P, De Ferrari GM, Murphy SA, Kuder JF, Gouni‐Berthold I, Lewis BS, Handelsman Y, Pineda AL, Honarpour N, Keech AC, Sever PS, Pedersen TR. Cardiovascular safety and efficacy of the PCSK9 inhibitor evolocumab in patients with and without diabetes and the effect of evolocumab on glycaemia and risk of new‐onset diabetes: a prespecified analysis of the FOURIER randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2017;5:941–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nicholls SJ, Puri R, Anderson T, Ballantyne CM, Cho L, Kastelein JJP, Koenig W, Somaratne R, Kassahun H, Yang J, Wasserman SM, Scott R, Ungi I, Podolec J, Ophuis AO, Cornel JH, Borgman M, Brennan DM, Nissen SE. Effect of evolocumab on progression of coronary disease in statin‐treated patients: the GLAGOV randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016;316:2373–2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Disease classification of biomarkers included in the OLINK CVD III assay.

Table S2. Assay information.

Table S3. Sensitivity analyses restricting our analyses only to survivors with a T‐classification of ≥2.

Table S4. Association of biomarkers with survivors treated with chemotherapy alone vs. controls.