Abstract

We report on the implementation of the concept of a photochemically elicited two‐carbon homologation of a π‐donor–π‐acceptor substituted chromophore by triple‐bond insertion. Implementing a phenyl connector between the slide‐in module and the chromophore enabled the synthesis of cylohepta[b]indole‐type building blocks by a metal‐free annulative one‐pot two‐carbon ring expansion of the five‐membered chromophore. Post‐irradiative structural elaboration provided founding members of the indolo[2,3‐d]tropone family of compounds. Control experiments in combination with computational chemistry on this multibond reorganization process founded the basis for a mechanistic hypothesis.

Keywords: cascade reactions; cyclohepta[b]indole; indole[2,3-d]tropone; photochemistry; ring expansion

By enabling cooperativity of substituent and solvent effects, the concept of a photochemically triggered two‐carbon ring expansion was implemented to open a modular synthetic access to cyclohepta[b]indole‐type buildings blocks (see scheme).

The N‐heteroacene cyclohepta[b]indol1 (1) features the basic scaffold of a variety of man‐made pharmaceutically active compounds2 and natural products,3 for example, alstonlarsine A (2)4 (Figure 1). To address the challenges associated with the synthesis of cyclohepta[b]indol‐type building blocks, a well‐diversified portfolio of enabling synthetic methods is already available.5 Variations of annulation reactions,6 of (m+n)‐cycloadditions,7 and of the Cope rearrangement8 have proven particularly valuable. Notably, however, organic photochemistry has not yet been exploited to access perhydrocyclohepta[b]indole‐type building blocks (3).

Figure 1.

Motif (1), Variation (2), and Building Block (3).

To complement the existing methodology, we aimed for a fuse–compress–expand sequence to 6,7‐dihydro‐cyclohepta[b]indol‐8(5H)‐ones 4 that exploits an unprecedented photochemically triggered two‐carbon ring‐expansion (Figure 2).9 Fusing is accomplished by Sonogashira cross‐coupling between o‐iodo anilines (5) and terminal alkynes (6), followed by condensation with five‐membered cyclic 1,3‐dicarbonyl compounds (7) and finalized by N‐acylation to deliver photochemistry‐competent vinylogous amides 8. The subsequent compress‐and‐expand phase consists of a photochemically triggered formation of a transient [2+2]‐cycloadduct that subsequently collapses to deliver the 6,7‐dihydro‐cyclohepta[b]indol‐8(5H)‐one 4; hence, the actual ring‐expansion merges excited‐state with ground state chemistry to an unprecedented one‐pot process.

Figure 2.

Fuse–compress–expand strategy to 6,7‐dihydrocyclohepta[b]indol‐8(5H)‐ones.

The experimental procedures and characterization data for the products 8 of the fuse‐phase are provided in full detail in the Supporting Information (29 examples). The results of our study on the photochemically triggered two‐carbon ring‐expansion of 8 are summarized in Tables 1–3. We adopted our previously optimized conditions for the alkyne de Mayo reaction without the necessity of optimization. Hence, solutions of the N‐protected vinylogous amides 8 a–ab (0.16 mmol) in degassed 2,2,2‐trifluoroethanol (TFE, c=0.03 m) were irradiated in sealable quartz tubes using the low‐pressure mercury vapor lamps (E max=254 nm) of a commercially available photoreactor. Reaction times refer to reactor running times. The appearance of yellow colored reaction mixtures served as an indicator for product formation and progression of conversion was detected by TLC analysis.

Table 1.

Two‐carbon ring expansion: Varying R1.

|

|

Table 3.

Two‐carbon ring expansion: Varying R1−4 and Z.

|

|

Representative examples for aliphatic and aromatic substituents at C‐10 were initially screened (Table 1). Ring expansion proceeded for R1=octyl‐ (8 a), 4‐hydroxylbutyl‐ (8 b) and 4‐siloxybutyl (8 c) to deliver 4 a–c in useful yields (85–92 %). Somewhat unexpectedly, hydroxylmethyl‐substitution (8 d) triggered decomposition under irradiation. No defined degradation product could be isolated. The nature of the decomposition pathway(s) remains speculative. Fortunately, irradiation of the corresponding silyl ether 8 e delivered the ring‐expansion product 4 e in 86 % yield. 2‐Aminotolane‐derived 8 f was susceptible to ring‐expansion at prolonged reaction times and delivered the R1=phenyl substituted 4 f in moderate yield (52 %).

For pharmaceutically relevant cyclohepta[b]indoloids, substituent diversification at C‐2 is frequently found.2 Consequently, we moved on to study substituent effects for R2≠H at C‐2 and using R1=CH3 at C‐10 as a prototype for alkyl substitution (Table 2). Methyl‐ (8 g), trifluoromethyl‐ (8 h) and tert‐butyl‐substitution (8 i) at C‐2 were tolerated and 4 g‐i were isolated in valuable yields (75–91 %). 4‐Aminobiphenyl‐based 8 j underwent the ring‐expansion slowly and sluggishly to provide 4 j (26 %) in low yield. Bromo or fluoro substitution enabled access to 4 k (83 %) or 4 l (83 %). Suzuki–Miyaura cross‐coupling of 4 k with phenylboronic acid under carefully optimized conditions delivered 4 j (92 %); thus 4 k may serve as a relay compound for post‐ring expansion structural diversification (vide infra).10 π‐Donor (R2=OCH3) and π‐acceptor (R2=CO2Me or CN) substitution allowed the formation of 4 m (57 %), 4 n (86 %), and 4 o (86 %). However, no conversion was observed for R2=NO2 (8 p, not depicted).

Table 2.

Two‐carbon ring expansion: Varying R2.

|

|

[a] PhB(OH)2 (1.5 equiv), Pd(PPh3)2Cl2 (0.05 equiv), PCy3 (0.1 equiv), Cs2CO3 (1.5 equiv), 1,4‐dioxane (297 equiv), 80 °C, 5.5 h, 92 % (226 mg).

We proceeded to study substituent effects at C‐3 or C‐4 for R2=H at C‐2 and R1=CH3 at C‐10. (Table 3). Subjecting vinylogous amides featuring methyl (8 q), fluoro (8 r), or chloro (8 s) substitution at C‐3 to the ring‐expansion protocol afforded 4 q (90 %), 4 r (83 %), and 4 s (86 %) in valuable yields. Ring‐expansion of m‐aminobenzoic acid derived 8 t (R1=CH3, R3=CO2Me) required strikingly prolonged irradiation (60 h, 4 o: 7 h) and delivered 4 t (66 %, 4 o: 86 %) in moderate yield. Degradation was observed for R4=CH3 (8 u); in the event, we speculate that „steric hindrance“ interferes with the photochemical compress‐phase of the ring‐expansion process. 2‐Aminonaphthalene‐based 8 w resisted irradiation (96 h) and was re‐isolated (96 %), whereas irradiation of the 5,6,7,8‐tetrahydro‐2‐aminonaphthalene‐based 8 v proceeded reluctantly to afford tetracyclic 4 v (50 %) in moderate yield. 5‐Aminobenzo[d][1,3]dioxole‐derived 8 x successfully underwent the ring‐expansion to yield tetracyclic 4 x (52 %) in reasonable yield. Finally, we turned to chromophore diversification. Irradiation of N‐acetyl derivative 8 y yielded the ring‐expanded product 4 y in 86 % yield after only 2.75 h of reactor running time. When irradiating tetronic acid‐originated 8 z (R1=CH3, Z=O), no conversion was detected by TLC. Tetramic acid‐derived 8 aa (R1=CH3) and 8 ab (R1=Si(CH3)3), however, could be converted into the desired ring‐expansion products 4 aa (51 %) and 4 ab (41 %) with moderate success.

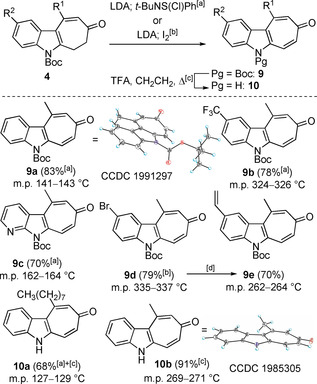

We are interested in utilizing indole‐tropone‐fused cyclohepta[b]indol‐8‐ones (indolo[2,3‐d]tropones, 10) as scaffold elements for the synthesis of extended N‐heteroacenes, N‐heterohelicenes, and as building blocks in natural product total synthesis (Table 4). Thus, we explored the dehydrogenation of selected 6,7‐dihydro‐cyclohepta[b]indol‐8(5H)‐ones 4. The corresponding lithium enolates were treated with N‐tert‐butylbenzenesulfinimidoyl chloride11 to deliver Boc‐protected indolo[2,3‐d]tropones 9.12, 13 Purification of the thus prepared cyclohepta[b]indol‐8‐ones 9 was complicated by intractable impurities of N‐(tert‐butyl)‐S‐phenylthiohydroxylamine. Alternatively, the enolate of 4 k was treated with I2 to deliver Boc protected 9 d (79 %); aryl bromide 9 d is anticipated to serve as a relay compound for scaffold extension as exemplified by Suzuki cross‐coupling with potassium vinyltrifluoroborate to afford 9 e (70 %). Removal of the Boc protecting group delivered 10 a (68 %) and 10 b 12 (91 %) representing founding members of the indolo[2,3‐d]tropone (10) family of compounds.14, 15, 16

Table 4.

Two‐carbon ring expansion: Varying R2.

|

|

[a] LDA, THF, −78 °C, then tBuNS(Cl)Ph, −78 °C; [b] LDA (1.5 equiv), THF, −78 °C to −50 °C, 1 h, then I2 (1.6 equiv), −50 °C to rt, 0.5 h, 79 % (207 mg); [c] TFA (28 equiv), CH2Cl2, 40 °C; [d] CH2CHBF3K (2 equiv), Pd2(dba)3 (0.1 equiv), P(tBu)3⋅HBF4 (0.1 equiv), Cs2CO3 (3 equiv), 1,4‐dioxane‐H2O (10:1), 60 °C, 30 min, 70 % (108 mg).

We used experimental and computational studies to gain mechanistic insights into the ring‐expansive multibond reorganization process. Experimentally, irradiation (350 nm) of 8 k in the presence of a triplet sensitizer (xanthone) triggered formation of 4 k; on the other hand, formation of 4 k was suppressed at 254 nm in the presence of a triplet quencher (2,5‐dimethylhexa‐2,4‐diene).17 On this basis, we assumed a [2+2] cycloaddition on the triplet surface. To gain further mechanistic insights, we performed (TD)DFT studies using the model compound 11 (Figure 3).18, 19 Our calculations on the B3LYP/def2‐TZVP level of theory predict a vertical excitation of S0‐11 to an upper Sn‐state (+112.6 kcal mol−1) that is followed by internal conversion (IC) to the S1‐11 state (n,π* character with respect to the α,β‐enone segment) and intersystem crossing (ISC) to the T1‐11 state.20 Our computations suggest π,π* character for T1‐11 with spin‐density being located above and below the α,β‐enone segment. Subsequent low‐barrier (+4.8 kcal mol−1) 5‐exo‐dig cyclization to T1‐13 via 12 is predicted to be highly exoenergetic (−21.1 kcal mol−1). T1‐13 was calculated to be almost isoenergetic to the double bond isomeric T1‐14 (−0.5 kcal mol−1); T1‐13 is interconnected with T1‐14 via a low‐barrier transition state (+1.8 kcal mol−1, not depicted). Rapid ISC of T1‐14 to S0‐14 is followed by an almost barrier‐less (+1.1 kcal mol−1) and highly exoenergetic (−42.1 kcal mol−1) cyclization via 15 to the (2+2) photocycloadduct 16. According to gas‐phase DFT calculations, the π‐donor–π‐acceptor substituted cyclobutene segment of 16 is susceptible to a slightly endoenergetic (+2.8 kcal mol−1) concerted bond reorganization via the transition‐state 17 (+24.1 kcal mol−1) to afford 18 featuring a trans‐α,β‐enone moiety.21 The stereochemical result of the modeled conversion of 16 to 18 is in accordance with a bond reorganization proceeding by a conrotatory 4π‐electrocyclic ring‐opening. Although predicted to be highly exoenergetic, attempts to localize a pathway leading from 18 (or 16) to the model compound 19 for the experimentally observed ring expansion‐products by gas‐phase computations were futile. The scale of the predicted barrier height (+24.1 kcal) for the conversion of 16 to 18 encouraged experimental studies to identify the [2+2]‐cycloadduct. However, efforts to detect the elusive [2+2]‐cycloadduct from 8 k by (preparative) TLC or by NMR experiments in deuterated solvents failed. The ring‐opening was then re‐modeled by considering explicit hydrogen‐bonding interactions between two molecules of 2,2,2‐trifluoroethanol (TFE) and the carbonyl oxygen atom of 16 (Figure 3). Our DFT calculations predict a slightly lower barrier for the weakly endoenergetic electrocyclic ring‐opening of 16⋅2TFE via 17⋅2TFE (+22.7 kcal mol−1, not depicted; corresponds to a calculated t 1/2=81 min) to 18⋅2TFE (+3.4 kcal mol−1). Notably, however, consideration of explicit hydrogen bonding interactions opens a low‐barrier (+11.2 kcal mol−1) pathway for the double‐bond isomerization of 18⋅2TFE to 19⋅2TFE (−35.5 kcal mol−1, not depicted) via 20⋅2TFE. The transition‐state structure 20⋅2TFE may be best explained as a tightly hydrogen‐bonded non‐π‐resonating α,β‐eniminium‐enolate zwitterion that we could not locate computationally without considering the transition‐state stabilizing interaction with TFE. Experimentally, attempts to perform the two‐carbon ring‐expansion of 8 k in CH3CN or CH3OH led to considerably lower isolated yields of 4 k (CH3CN: 61 %; CH3OH: 33 %). In both cases 4 k was contaminated with unidentified inseparable impurities. To further study the apparent solvent effect, control experiments were run in 1,1,1,3,3,3‐hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP). Much to our initial surprise, the resulting isolated yields were considerably lower (HFIP: 66 %, TFE: 83 %) 4 k but free of detectable impurities. We later realized that the comparatively lower yields in HFIP can be attributed to the cleavage of the Boc protecting group in HFIP [22] which slowly proceeds even at ambient temperature without irradiation.

Figure 3.

(TD)DTF (u)B3LYP/def2‐TZVP calculated (relative) electronic plus zero‐point energies (ΔE) at 298.15 K in kcal mol−1.

In summary, we reveal a conceptually novel approach to the cyclohepta[b]indole scaffold. Irradiation (254 nm) of modularly assembled vinylogous amides from 2‐alkynyl anilines in 2,2,2‐trifluoroethanol at ambient temperature triggered an intramolecular one‐pot annulative two‐carbon ring expansion to deliver 6,7‐dihydro‐cyclohepta[b]indol‐8(5H)‐ones. The process merges exited‐state [2+2]‐cycloaddition with ground‐state 4π‐electrocyclic ring‐opening. Computational chemistry suggests that solvent cooperativity is fundamental to the success of the overall multibond reorganization process. We also report the post‐irradiative synthesis and characterization of founding members of the indolo[2,3‐d]tropone family of compounds.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

Financial support by the TU Dortmund is gratefully acknowledged. Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

D. C. Tymann, L. Benedix, L. Iovkova, R. Pallach, S. Henke, D. Tymann, M. Hiersemann, Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 11974.

References

- 1.

- 1a. Treibs W., Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1952, 576, 110–115; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1b. Boyer J. H., De Jong J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1969, 91, 5929–5930. [Google Scholar]

- 2.

- 2a. Kuehm-Caubère C., Caubère P., Jamart-Grégoire B., Pfeiffer B., Guardiola-Lemaître B., Manechez D., Renard P., Eur. J. Med. Chem. 1999, 34, 51–61; [Google Scholar]

- 2b. Napper A. D., Hixon J., McDonagh T., Keavey K., Pons J.-F., Barker J., Yau W. T., Amouzegh P., Flegg A., Hamelin E., Thomas R. J., Kates M., Jones S., Navia M. A., Saunders J. O., DiStefano P. S., Curtis R., J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 8045–8054; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2c. Barf T., Lehmann F., Hammer K., Haile S., Axen E., Medina C., Uppenberg J., Svensson S., Rondahl L., Lundbäck T., Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 1745–1748; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2d. Yamuna E., Kumar R. A., Zeller M., Jayarampillai R. P. K., Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 47, 228–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.For a recent example, see: Krishnan P., Lee F.-K., Chong K.-W., Mai C.-W., Muhamad A., Lim S.-H., Low Y.-Y., Ting K.-N., Lim K.-H., Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 8014–8018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhu X.-X., Fan Y.-Y., Xu L., Liu Q.-F., Wu J.-P., Li J.-Y., Li J., Gao K., Yue J.-M., Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 1471–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stempel E., Gaich T., Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 2390–2402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.For selected recent examples, see:

- 6a. Kaufmann J., Jäckel E., Haak E., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 5908–5911; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 6010–6014; [Google Scholar]

- 6b. Kroc M. A., Prajapati A., Wink D. J., Anderson L. L., J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 1085–1094; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6c. Jadhav A. S., Pankhade Y. A., Vijaya Anand R., J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 8615–8626; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6d. Zeng Q., Dong K., Huang J., Qiu L., Xu X., Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 2326–2330; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6e. Zhang L., Zhang Y., Li W., Qi X., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 4988–4991; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 5042–5045. [Google Scholar]

- 7.For selected recent examples, see:

- 7a. Takeda T., Harada S., Okabe A., Nishida A., J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 11541–11551; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7b. Gelis C., Levitre G., Merad J., Retailleau P., Neuville L., Masson G., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 12121–12125; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 12297–12301; [Google Scholar]

- 7c. Wang Z., Addepalli Y., He Y., Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 644–647; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7d. Parker A. N., Martin M. C., Shenje R., France S., Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 7268–7273; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7e. Xu J., Rawal V. H., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 4820–4823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.For selected recent examples, see:

- 8a. Xu G., Chen L., Sun J., Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 3408–3412; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8b. Häfner M., Sokolenko Y. M., Gamerdinger P., Stempel E., Gaich T., Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 7370–7374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.For the initial example, see: Tymann D., Tymann D. C., Bednarzick U., Iovkova-Berends L., Rehbein J., Hiersemann M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 15553–15557; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 15779–15783. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conditions adapted from: Agbo E. N., Makhafola T. J., Choong Y. S., Mphatele J. M., Ramasami P., Molecules 2015, 21, 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mukaiyama T., Matsuo J.-i., Kitagawa H., Chem. Lett. 2000, 29, 1250–1251. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deposition numbers 1991297 and 1985305 (9 a and 10 b) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data are provided free of charge by the joint Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre and Fachinformationszentrum Karlsruhe Access Structures service.

- 13.Structural assignment in solid state and in solution is in accordance with the notion of 9 as cyclohepta[b]indol-8(5H)-one and not as tautomeric cyclohepta[b]indol-8-ol.

- 14.To the best of our knowledge, parent indolo[2,3-d]tropone has been mentioned only once, see: Nozoe T., Horino H., Toda T., Tetrahedron Lett. 1967, 8, 5349–5353. [Google Scholar]

- 15.For the synthesis of indolo[2,3-b]tropones, see:

- 15a. Yamane K., Fujimori K., Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1976, 49, 1101–1104; [Google Scholar]

- 15b. Jiye J., Kunihiro I., Fumiki T., Mitsunori O., Chem. Lett. 2010, 39, 861–863; [Google Scholar]

- 15c. De Jong J., Boyer J. H., J. Org. Chem. 1972, 37, 3571–3577. [Google Scholar]

- 16.For the synthesis of indolo[3,2-b]tropones, see:

- 16a. Mishra U. K., Yadav S., Ramasastry S. S. V., J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 6729–6737; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16b.see also reference 15a).

- 17.For experimental details, see the Supporting Information.

- 18.For computational details, see the Supporting Information.

- 19.For related computational studies, see:

- 19a. García-Expósito E., Bearpark M. J., Ortuño R. M., Robb M. A., Branchadell V., J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 6070–6077; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19b. Cucarull-González J. R., Hernando J., Alibés R., Figueredo M., Font J., Rodríguez-Santiago L., Sodupe M., J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 4392–4401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schalk O., Schuurman M. S., Wu G., Lang P., Mucke M., Feifel R., Stolow A., J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118, 2279–2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.For mechanistic studies concerning the electrocyclic ring opening of fused cyclobutenes, see:

- 21a. Silva López C., Faza O. N., de Lera Á. R., Chem. Eur. J. 2007, 13, 5009–5017; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21b. Wang X.-N., Krenske E. H., Johnston R. C., Houk K. N., Hsung R. P., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 9802–9805; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21c. Ralph M. J., Harrowven D. C., Gaulier S., Ng S., Booker-Milburn K. I., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 1527–1531; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 1547–1551. [Google Scholar]

- 22.For N-Boc cleavage in fluorinated alcohols at elevated temperatures, see: Choy J., Jaime-Figueroa S., Jiang L., Wagner P., Synth. Commun. 2008, 38, 3840–3853. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary