Pediatric lymphatic flow disorders present a unique disease spectrum with specific challenges and considerations. The immense recent advances in lymphatic imaging and therapeutics have allowed the identification and treatment of these devastating symptoms from the neonatal period to adolescence. The development of dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance lymphangiography (DCMRL) has provided accurate diagnoses and classification of neonatal and pediatric flow disorders. The concomitant innovation in the field of lymphatic interventions including thoracic duct (TD) embolization, interstitial embolization, and lymphovenous anastomosis offers curative interventions. As the field rapidly grows, there is a need for both classification and treatment algorithms for these diseases.

This article describes the pediatric-specific lymphatic pathologies and technical considerations of treatment and diagnosis of lymphatic flow disorder.

Neonatal Lymphatic Flow Disorders

Neonatal chylothorax, chylous ascites, and fetal hydrops are highly morbid conditions, resulting in lymphopenia, hypalbuminemia, hypogammaglobulinemia, coagulopathy, pulmonary hypoplasia, and failure to thrive. Conservative management includes pleural and abdominal fluid drainage, total parenteral nutrition, or medium chain triglyceride (MCT) formula, and administration of octreotide. 1 Recently, sirolimus, an MTOR inhibitor, has been added to the pharmacologic armament. 2 However, the response to conservative treatment varies between patients as well as lead time to improvement. DCMRL visualization of the anatomy and function of the lymphatic system has identified several different imaging patterns of these conditions and allowed better understanding of their pathophysiology. 3 Lymphatic embolization techniques offer definitive treatment for some of these pathologies once they are identified. 4

Fetal and neonatal lymphatic disorders can be divided into three categories: isolated chylothorax, chylous ascites, and central lymphatic flow disorder.

Isolated Chylothorax

Isolated chylothorax can present on fetal imaging or in the immediate postnatal period. These effusions often necessitate external drainage with chest or pericardial drains. Traditional management has been conservative, including diet modifications such as parenteral nutrition or specific MCT formula feeds. 1 Unfortunately, neonates are particularly vulnerable to the malnutrition and immunosuppression associated with prolong lymphatic leaks during a time of massive growth. The presence of drainage catheters for a protracted period of time in these patients increases the risk of superinfection. The need for TPN necessitates vascular access which can cause multiple complications, including vessel thrombosis and central line infection.

The new lymphatic diagnostic tools, however, can precisely identify the pathophysiological mechanism and new lymphatic interventions can provide effective therapeutic solutions.

DCMRL of patients with isolated pleural effusions typically demonstrates abnormal pulmonary lymphatic flow from the TD toward lung parenchyma thorough the branches of the TD ( Fig. 1a ). 5 These branches abut the pleural surface with lymph weeping into the pleural and pericardium spaces most probably through pleural stomata. In most of the patients, DCMRL shows congenital occlusion of the distal part of the TD resulting in developing collateral vessels that traverse mediastinum and lung parenchyma. 4

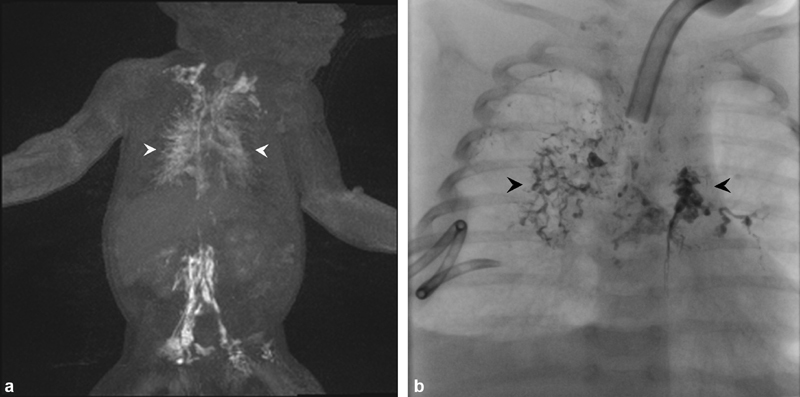

Fig. 1.

( a ) Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance lymphangiography of pulmonary lymphatic flow demonstrating contrast within the pulmonary lymphatics (arrowheads). ( b ) Fluoroscopic spot image of transnodal embolization with lipiodol demonstrating stasis within the pulmonary lymphatic ducts (arrowhead).

Following DCMRL, these patients undergo conventional intranodal lymphangiography using lipiodol (Guerbet Group, Princeton, NJ). The therapeutic effect of lipiodol as a treatment of chylous leaks has been well described and is probably the result of occlusion of the small lymphatic vessels or pleural stomata by the oil-based contrast. 6 Intranodal lymphangiography is performed by positioning the 25G spinal needles into bilateral inguinal lymph nodes under ultrasound guidance. The proper position of the needles is confirmed under fluoroscopy with water-soluble contrast. Lipiodol is then injected into lymph nodes until there is appropriate stasis within the abnormal pulmonary lymphatics ( Fig. 1b ). It is very important to limit the amount of lipiodol to approximately 1 to 2 mL (∼0.25 mL/kg), divided between each groin node, as larger doses of lipiodol can adversely affect the lymphatic system. 7 If the intranodal injection cannot deliver the adequate amount of the lipiodol in the pulmonary lymphatic circulation, catheterization of the TD and TD embolization can be performed.

Isolated Neonatal Ascites

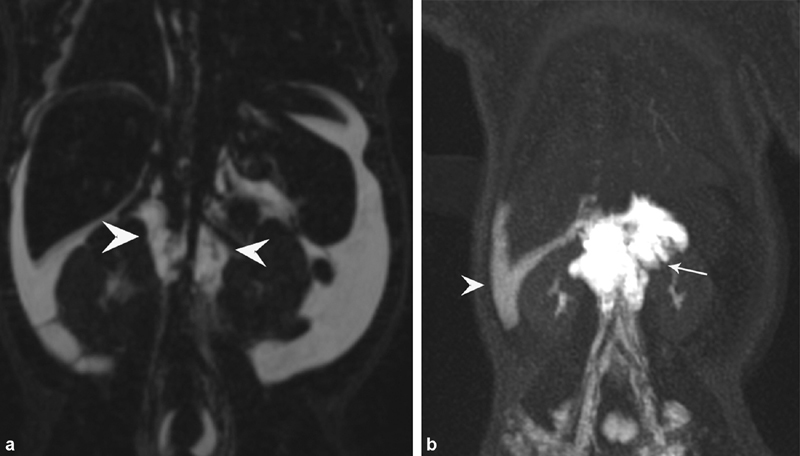

Isolated neonatal ascites is considerably more complex to treat than pleural effusions. Initially conservative treatment is attempted, similar to chylothorax. This consists of peritoneal drain placement and diet modification, including nothing by mouth, parenteral nutrition, or MCT formula feeds. 1 In our experience, the most common cause of the chylous ascites is large retroperitoneal lymphatic masses, which are often visible on T2-weighted imaging ( Fig. 2a ). If a focal leak is identified on DCMRL ( Fig. 2b ), intranodal lymphangiography is performed to guide the intervention. After the identification of the leak, the lymph nodes or lymphatic masses below the leak can be accessed with 25G spinal needle and be embolized percutaneously with N-BCA glue (TRUFILL, Codman Neuro, Raynham, MA) diluted 1:2 with lipiodol. 8 9 If the leak cannot be visualized on DCMRL and/or intranodal lymphangiography, open surgical approach can be attempted and combined glue embolization and surgical closure can be performed. Unfortunately, due to rarity of neonatal chylous ascites, the treatment approaches are not standardized as reflected in several case reports describing varied methods primarily in adult populations. 10 11

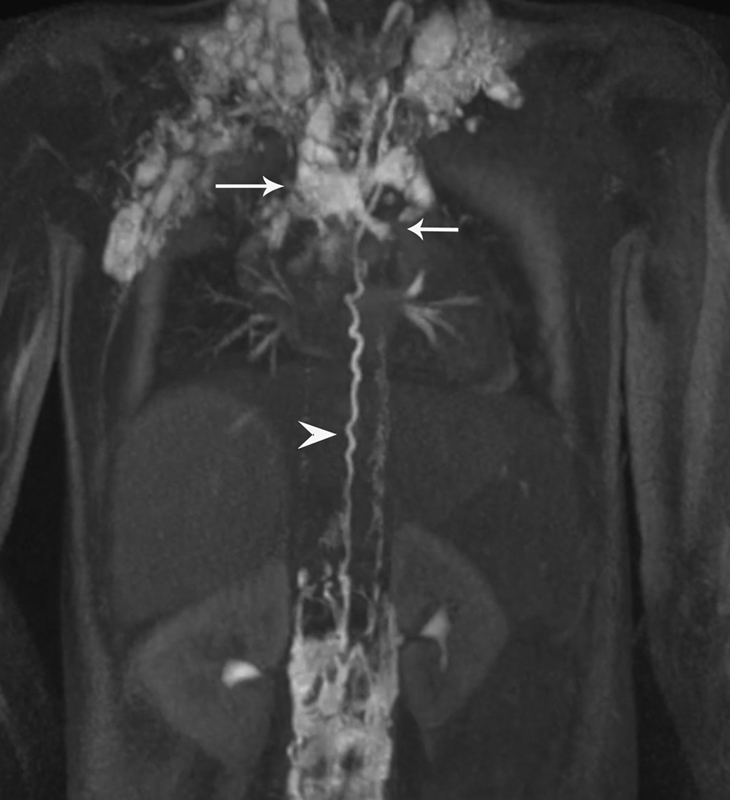

Fig. 2.

( a ) T2-weighted coronal MR sequences of patient with neonatal chylous ascites, demonstrating diffuse ascites and retroperitoneal mass (arrowheads). ( b ) Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance lymphangiography of the same patient demonstrating opacification of the retroperitoneal masses (arrow) and leak of contrast into peritoneal space (arrowhead).

Central Lymphatic Flow Disorder

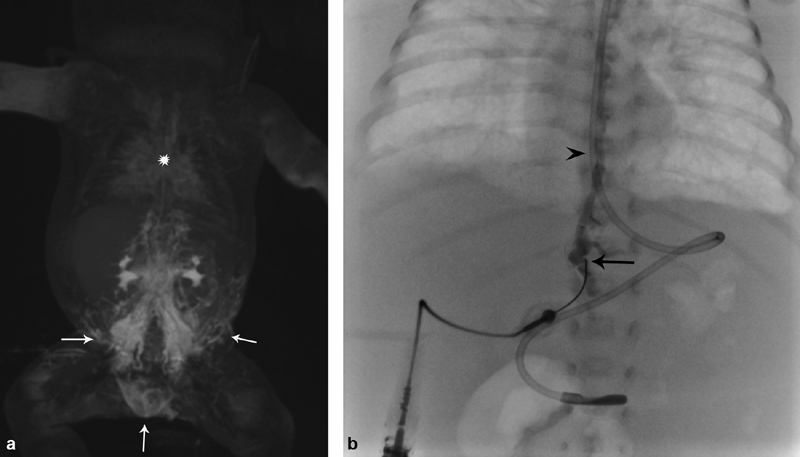

Central lymphatic flow disorder, also described as central lymphatic conducting anomaly, presents as a triad of fetal/neonatal pleural effusion, ascites, and diffuse anasarca. 12 13 This represents altered flow through the central lymphatic system without adequate collateralization. This is often associated with Noonan's syndrome, Turner's syndrome, and Down's syndrome. 14 15 Elevated central venous pressure often is a consequence of elevated pulmonary pressure due to chronic lung disease and neonates frequently can back up the lymphatic flow. In these cases, no intervention is indicated, and the treatment focuses on reduction of pulmonary hypertension and conservative treatment of chylous effusions. Neonates with pleural effusions associated with hydrops have a reported mortality of 69 to 75%. 16 DCMRL usually demonstrates lack of propagation of the contrast through central lymphatic system with dermal lymphatic backflow in the abdominal wall ( Fig. 3a ). Lymphatic embolization in these patients usually is not helpful, as the main pathophysiological mechanism is a central lymphatic obstruction and not a lymphatic leak. In cases of distal obstruction of TD, surgical lymphovenous anastomosis can be attempted. 17 18 Often the central lymphatic system is not visualized on DCMRL or intranodal lymphangiography, because high pressure in the occluded TD precludes contrast propagation. For that reason, we usually perform direct pressurized injection of the TD through a 25G spinal needle, positioned in the upper abdomen at the level of T12–L1 vertebra ( Fig. 3b ). However, if defined TD is absent and replaced with a dysplastic central lymphatic system, the therapeutic options are limited to conservative measures. The somatostatin analog octreotide has been used in this condition with varying results. 1 Recently, successful use of sirolimus (MTOR inhibitor) as well as trametinib (MEK inhibitor) has been reported. 19 20

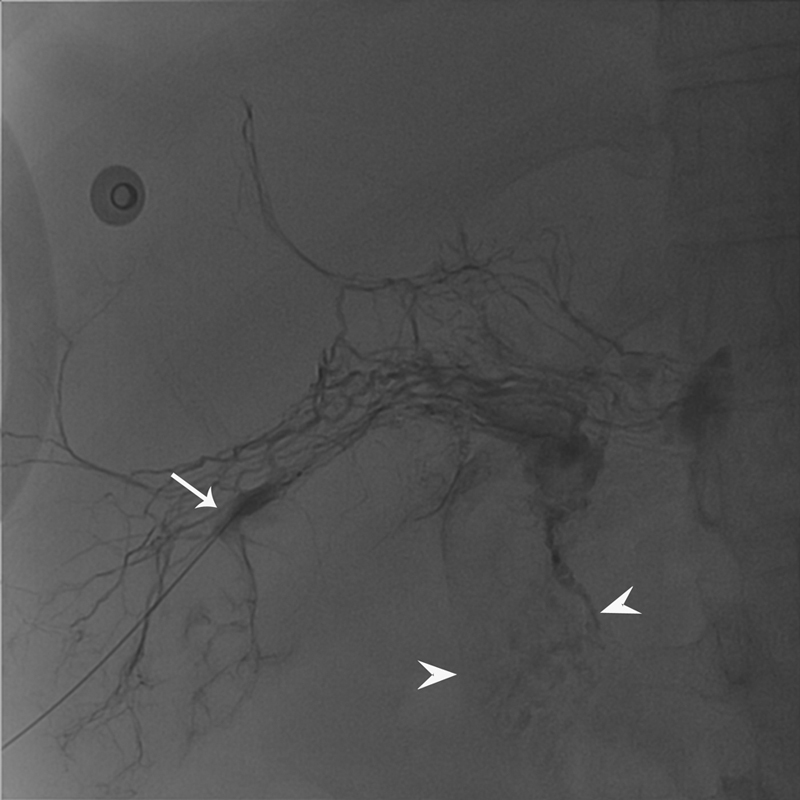

Fig. 3.

( a ) Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance lymphangiography of a patient with central lymphatic flow disorder, demonstrating stasis of contrast in the retroperitoneal lymphatic system with retrograde dermal filling (arrows) in lack of advancement of the contrast in thoracic duct (star). ( b ) Fluoroscopy image of the same patient, showing direct injection of the cisterna chyli with 25G needle (arrow) in the upper retroperitoneum, opacifying thoracic duct (arrowhead).

Pediatric Lymphatic Flow Disorders

Lymphatic flow disorders with high prevalence during childhood years include complex lymphatic malformations, plastic bronchitis (PB), and protein losing enteropathy.

Complex Lymphatic Malformations

Lymphatic malformation (LM) is a group of diseases that involve multiple organ systems including the lungs, bones, liver, the spleen, and the intestines. These diseases include generalized lymphatic anomaly (GLA), Kaposiform lymphangiomatosis (KLA), and Gorham-Stout disease (GSD). 13 KLA is a subset of GLA and presents with severe coagulopathy, chronic DIC, and pathognomonic lymphatic endothelial spindle cells on tissue biopsy. 13 KLA patients often have extravascular hemorrhage within the lymphatic fluid, including hemorrhagic chylous pleural and pericardial effusions. Bone involvement in GLA and KLA spares the cortex and most frequently affects the vertebrae. Bone cortex destruction and involvement of the ribs is typical for patients with GSD, also known as “vanishing bone disease.” 21

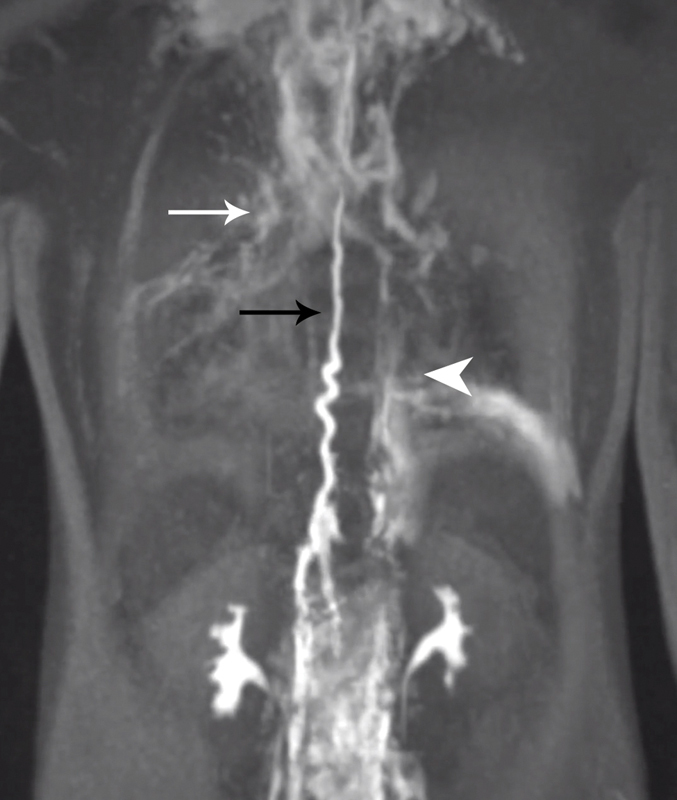

Pulmonary involvement including interstitial lung disease and/or pleural effusions is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in these patients. 1 14 A recent study reported the presence of the abnormal pulmonary lymphatic flow from TD or retroperitoneum into lung parenchyma in patients with LM ( Fig. 4 ). 22 Percutaneous embolization of the abnormal lymphatic vessels carrying this flow into the lung parenchyma was reported to be successful in the resolution of pleural effusion and improvement of pulmonary function in these patients. 22 23

Fig. 4.

Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance lymphangiography of the patient with Kaposiform lymphangiomatosis, demonstrating abnormal pulmonary lymphatic flow (white arrow) from the thoracic duct (black arrow) and retroperitoneum (arrowhead). (Reprinted from: Itkin M, Rabinowitz D, Nadolski G, Stafler P, Mascarenhas L, Adams D. Abnormal pulmonary lymphatic flow in patients with lymphatic anomalies and respiratory compromise on MR lymphangiogram. Chest 2019:A7386-A7386.)

Plastic Bronchitis

Plastic bronchitis is a condition where the patients expectorate fibrinous white-yellowish casts in the shape of the bronchial tree. In children, this typically occurs in patients with congenital heart disease often with Fontan physiology, affecting approximately 4 to 14% of this population. 24 Traditional medical management has centered on airway clearance with aerosolized tissue plasminogen activator, nebulizers, chest physical therapy, reduction of central venous pressure with Fontan fenestration, pulmonary arterial vasodilators, and corticosteroid therapy. 25 Unfortunately, the mortality rate of PB with conservative treatment has been reported as high as 14 to 50%. 26 Ultimately these patients have to undergo cardiac transplantation as a potential curative intervention. 27 Recently, DCMRL demonstrated that the cause of this condition is abnormal pulmonary lymphatic flow from TD into mediastinum similar to isolated neonatal chylothorax ( Fig. 5 ). 2 7 These abnormal lymphatics abut the bronchial wall, causing protein-rich lymph to seep into the bronchial endothelium and become inspissated in the bronchial tree into casts causing severe cough, airway plugging, and ultimately respiratory failure. 28

Fig. 5.

Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance lymphangiography image of the single ventricle patient with plastic bronchitis, demonstrating abnormal pulmonary flow (arrows) from the thoracic duct (arrowhead).

Understanding that the abnormal pulmonary lymphatic flow originates in the TD allows the application of a well-established TD embolization technique to treat PB. A 2016 case series reported 18 patients with Fontan anatomy and PB underwent lymphangiography. 29 In 16 of these patients, abnormal pulmonary lymphatic flow toward the lung parenchyma was demonstrated and all of them underwent TD cannulation with embolization of the abnormal flow, either selectively using N-butyl cyanoacrylate (NBCA) or lipiodol, TD stenting with exclusion of the abnormal flow, or TD embolization with coils/NBCA glue. Fifteen of 16 (94%) patients had significant improvement in symptoms and medical PB therapy was terminated. 17 Since the publication of this study, our group has identified several patients with PB in whom the abnormal lymphatic flow originated from the liver lymphatics and not the TD. This finding raises the possibility that the liver is another source of the lymphatic leakage for those patients with PB that were not successfully identified on traditional lymphangiography.

Although PB in Fontan patients is similar in presentation to PB in adult cardiac failure patients, it is essential to understand the Fontan cardiac anatomy and its inherent risk. A large proportion of the Fontan patients will have a fenestration in their Fontan. This is an opening in the IVC portion of the Fontan graft, allowing blood to enter the single ventricle heart, which connects directly to the systemic circulation resulting in right to left shunt, allowing passage of the oil-based contrast or glue into the central circulation. For this reason, it is necessary to place an occlusion balloon through this fenestration that can be inflated if any embolic is identified entering the venous circulation. Additionally, systemic vein–pulmonary vein collaterals need to be occluded before any liquid embolic agent is administered to mitigate any stroke risk.

Protein-Losing Enteropathy

Protein-losing enteropathy (PLE) is an excessive loss of proteins into the gastrointestinal tract, resulting in hypoalbuminemia, hypogammaglobulinemia, lymphopenia, and deficiency of fat-soluble vitamins. 30 These deficiencies lead to anasarca, ascites, pleural effusions, immunocompromise, and failure to thrive. The causes of PLE can be separated in two groups: diseases of the intestinal tract and conditions associated with lymphatic congestion. 31 Reported prevalence of PLE is 3 to 24% of single ventricle patients. 30 Elevated fecal α1-antitrypsin is diagnostic for PLE. 32 Conservative treatment of PLE includes low fat diet as well as loss replacement with albumin, intravenous immunoglobulin infusions, and steroids.

Recently, liver lymphangiography and lymphatic embolization have been used to diagnose and treat patients with lymphatic congestion PLE in patients with congenital heart disease. Liver lymphangiography is performed by placing 25G needle into the liver lymphatics under ultrasound guidance and injection of the iodinated contrast under fluoroscopy. Liver lymphangiography in PLE demonstrated abnormal hepatoduodenal connection to the second portion of duodenum ( Fig. 6 ). Itkin et al reported a series of eight patients with congenital heart disease and PLE who underwent transhepatic lymphatic embolization of abnormal hepatoduodenal connection with lipiodol and/or NBCA glue. Both patients with lipiodol embolization had transitory increase in serum albumin levels but also experienced gastrointestinal bleeding. Three of the patients embolized with NBCA glue had continued improvement, two had transient improvement, and one had no response. 30 The risks of the systemic embolization in these patients are similar to the patients undergoing embolization of PB; so, similar precautions have to be observed.

Fig. 6.

Fluoroscopic image of the liver lymphangiography performed through 25G needle (arrow) demonstrating leakage of the contrast in the duodenum (arrowheads).

Unique Pediatric Considerations

The lymphatic disorders in children are similar to that in adults; however, there are several considerations that are unique to children. The smaller size of children, especially infants, makes access of their lymphatic system with currently available equipment more challenging. Often neonatal TD is accessible only with a 25G needle, rather than a microcatheter, thereby limiting the ability to effectively embolize the entire duct. Radiation is more damaging in children and therefore fluoroscopic times and doses must be minimized. The operator and anesthesia team have to be mindful of limitation of iodinated contrast dose as well as heat loss due to relatively larger body surface area. All of these factors speak to the need for precision, skill, and judicious decision making when treating pediatric lymphatic flow disorders. As this emerging field progresses and techniques and equipment improve, we expect improved outcomes with decreased complication rates, as well as expansion of applications and range of treatable conditions. Clarity in classification and organized treatment approaches are necessary, especially in this vulnerable population.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest None declared.

References

- 1.Bellini C, Ergaz Z, Radicioni M. Congenital fetal and neonatal visceral chylous effusions: neonatal chylothorax and chylous ascites revisited. A multicenter retrospective study. Lymphology. 2012;45(03):91–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hori Y, Ozeki M, Hirose K. Analysis of mTOR pathway expression in lymphatic malformation and related diseases. Pathol Int. 2020;70(06):323–329. doi: 10.1111/pin.12913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Itkin M, Nadolski G J. Modern techniques of lymphangiography and interventions: current status and future development. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2018;41(03):366–376. doi: 10.1007/s00270-017-1863-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Itkin M. Interventional treatment of pulmonary lymphatic anomalies. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2016;19(04):299–304. doi: 10.1053/j.tvir.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biko D M, Johnstone J A, Dori Y, Victoria T, Oliver E R, Itkin M. Recognition of neonatal lymphatic flow disorder: fetal MR findings and postnatal MR lymphangiogram correlation. Acad Radiol. 2018;25(11):1446–1450. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2018.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gray M, Kovatis K Z, Stuart T. Treatment of congenital pulmonary lymphangiectasia using ethiodized oil lymphangiography. J Perinatol. 2014;34(09):720–722. doi: 10.1038/jp.2014.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rajebi M R, Chaudry G, Padua H M. Intranodal lymphangiography: feasibility and preliminary experience in children. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011;22(09):1300–1305. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim J, Won J H. Percutaneous treatment of chylous ascites. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2016;19(04):291–298. doi: 10.1053/j.tvir.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Majdalany B S, Khayat M, Downing T. Lymphatic interventions for isolated, iatrogenic chylous ascites: a multi-institution experience. Eur J Radiol. 2018;109:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2018.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nadolski G J, Chauhan N R, Itkin M. Lymphangiography and lymphatic embolization for the treatment of refractory chylous ascites. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2018;41(03):415–423. doi: 10.1007/s00270-017-1856-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Srinivasa R N, Chick J FB, Gemmete J J, Hage A N, Srinivasa R N. Endolymphatic interventions for the treatment of chylothorax and chylous ascites in neonates: technical and clinical success and complications. Ann Vasc Surg. 2018;50:269–274. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2018.01.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trenor C C, III, Chaudry G. Complex lymphatic anomalies. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2014;23(04):186–190. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iacobas I, Adams D M, Pimpalwar S. Multidisciplinary guidelines for initial evaluation of complicated lymphatic anomalies-expert opinion consensus. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67(01):e28036. doi: 10.1002/pbc.28036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atton G, Gordon K, Brice G. The lymphatic phenotype in Turner syndrome: an evaluation of nineteen patients and literature review. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23(12):1634–1639. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2015.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biko D M, Reisen B, Otero H J. Imaging of central lymphatic abnormalities in Noonan syndrome. Pediatr Radiol. 2019;49(05):586–592. doi: 10.1007/s00247-018-04337-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Savla J, Itkin M, Rossano J W, Dori Y. Utilization of magnetic resonance lymphangiography to determine the etiology of chylothorax and predict the outcome of lymphatic embolization in patients with congenital heart disease. Circulation. 2018;134 01:A17065–A17065. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reisen B, Kovach S J, Levin L S. Thoracic duct-to-vein anastomosis for the management of thoracic duct outflow obstruction in newborns and infants: a CASE series. J Pediatr Surg. 2020;55(02):234–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2019.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weissler J M, Cho E H, Koltz P F. Lymphovenous anastomosis for the treatment of chylothorax in infants: a novel microsurgical approach to a devastating problem. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;141(06):1502–1507. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000004424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ozeki M, Nozawa A, Yasue S. The impact of sirolimus therapy on lesion size, clinical symptoms, and quality of life of patients with lymphatic anomalies. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019;14(01):141. doi: 10.1186/s13023-019-1118-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li D, March M E, Gutierrez-Uzquiza A. ARAF recurrent mutation causes central conducting lymphatic anomaly treatable with a MEK inhibitor. Nat Med. 2019;25(07):1116–1122. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0479-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goyal P, Alomari A I, Kozakewich H P. Imaging features of kaposiform lymphangiomatosis. Pediatr Radiol. 2016;46(09):1282–1290. doi: 10.1007/s00247-016-3611-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Itkin M, Rabinowitz D A, Nadolski G, Stafler P, Mascarenhas L, Adams D. Abnormal pulmonary lymphatic flow in patients with lymphatic anomalies and respiratory compromise. Chest. 2020;158(02):681–691. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.02.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Itkin M, Nadolski G, Rabinowitz D.Lymphatic embolization of abnormal pulmonary lymphatic flow in patients with lymphatic malformationsPresented at the: ISSVA; May 14, 2020. Available at:https://www.issva.org/online-workshop-2020/scientific-program/thursday-schedule. Accessed August 1, 2020

- 24.Caruthers R L, Kempa M, Loo A. Demographic characteristics and estimated prevalence of Fontan-associated plastic bronchitis. Pediatr Cardiol. 2013;34(02):256–261. doi: 10.1007/s00246-012-0430-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young and Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing. . Rychik J, Atz A M, Celermajer D S. Evaluation and management of the child and adult with Fontan circulation: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;140(06) doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Madsen P, Shah S A, Rubin B K. Plastic bronchitis: new insights and a classification scheme. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2005;6(04):292–300. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laubisch J E, Green D M, Mogayzel P J, Reid Thompson W. Treatment of plastic bronchitis by orthotopic heart transplantation. Pediatr Cardiol. 2011;32(08):1193–1195. doi: 10.1007/s00246-011-9989-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Itkin M, Pizarro C, Radtke W, Spurrier E, Rabinowitz D A. Lymphatic management in single-ventricle patients. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu. 2020;23:41–47. doi: 10.1053/j.pcsu.2020.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dori Y, Keller M S, Rome J J. Percutaneous lymphatic embolization of abnormal pulmonary lymphatic flow as treatment of plastic bronchitis in patients with congenital heart disease. Circulation. 2016;133(12):1160–1170. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.019710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Itkin M, Piccoli D A, Nadolski G. Protein-losing enteropathy in patients with congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(24):2929–2937. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levitt D G, Levitt M D. Protein losing enteropathy: comprehensive review of the mechanistic association with clinical and subclinical disease states. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2017;10:147–168. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S136803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Florent C, L'Hirondel C, Desmazures C, Aymes C, Bernier J J. Intestinal clearance of α 1-antitrypsin. A sensitive method for the detection of protein-losing enteropathy. Gastroenterology. 1981;81(04):777–780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]