Abstract

This article approaches the analytic of the “Muslim Question” through the prism of the discursive and conspiratorial use of demographics as an alleged threat to Europe. It argues that concerns about “Muslim demographics” within Europe have been entertained, mobilized, and deployed to not only construct Muslims as problems and dangers to the present and future of Europe, but also as calls to revive eugenic policies within the frame of biopower. The article begins by sketching the contours of the contemporary “Muslim Question” and proceeds with a critical engagement with the literature positing a deliberate and combative strategy by “Muslims” centered on birth rates—seen by these authors as a tactical warfare—to allegedly replace European “native” populations. The analysis continues by focusing on two images juxtaposing life and death as imagined within the replacement discourse, and that capture that discourse in powerful albeit disturbing ways. Finally, the article proposes reading the population replacement discourse as a deployment of biopolitics and one of its many techniques, namely, eugenics.

Keywords: biopolitics, conspiracy theories, demographics, eugenics, Muslim Question, racism

1. INTRODUCTION

Today “Muslims” exist as a controversy of sorts; “Muslims” are a problem, discursively crafted as a question longing for answers and interventions.1 In Europe, so the story goes, Muslims do not integrate into the nation‐state and remain isolated from society and its values, they do not speak the national language, they are underachievers in schools, have lower rates of employment and higher birth rates vis‐à‐vis “Western natives.”2 Muslims live in an archaic world of gender inequality. Muslim men oppress Muslim women, and the most pristine example of such oppression is the hijab. This atavistic world of inequality also renders Muslims intolerant toward sexual diversity and sexual minorities. Islam may or may not be the ultimate factor behind all of this, but certainly plays a role, for it represents a religious force, as the story continues, that does not, and might inherently not be able to, respect the separation between religion and the state which is taken to be a central feature of Western civilization. This premodern world, moreover, in sharp contrast to Western civilization, is considered to hold an innate sense of violence that, at best, is barely contained, and lurks in Muslim subjectivities, waiting to be activated through processes of radicalization, extremism, Islamism, and ultimately terrorism. The ontological differences between Muslims and Westerners are so immense to the point that, allegedly, these two constructed groups hold diametrical opposed conceptions toward live and death, “They [violent Muslims] love death,” we have been told, “as we [Westerners] love life” (Roy, 2017, p. 2).

Slight variations of this discourse have been uttered in French, Dutch, German, English, and many other languages. Iterated by politicians, journalists, academics, judges, teachers, and many others, on a broad spectrum of different political views, but more prominently from the (far) right. A critique of this discourse has emerged through the concept of Islamophobia, which reveals the stereotypes surrounding the figure of the “Muslim,” while also surveying the different processes of discrimination faced by Muslims (Sayyid, 2014; Klug, 2012; Kundnani, 2014; Law et al., 2019; Bayrakli & Hafez, 2017). Islamophobia's usefulness as a concept, however, has also been contested, both etymologically for its imprecision (Halliday, 1999; Vakil, 2010),3 and analytically and historically for its detachment from larger trajectories such as Orientalism, colonial racial formations, and its “family resemblance” with the 19th‐century European Jewish Question, although there have been important efforts to entangle these histories (Medovoi, 2012; Meer, 2013; Meer & Modood, 2009; Said, 1985).

More recently, the analytical frame of the “Muslim Question” was brought to scholarly discussions and analyses of Muslims and Islam in Europe (Anidjar, 2012; Farris, 2014; Norton, 2013; O’Brien, 2015; Mansouri, Lobo, & Johns, 2015).4 This conceptualization further traces the problematization—which, following Michel Foucault (1988), refers to the processes of how and why something or somebody is turned into a problem—of Islam and Muslims in Europe and seeks to apprehend the systematic character of this process. We understand the analytic of the “Muslim Question” to revolve around two dimensions. First, the accusation of being an “alien body” to the nation (Farris, 2014, pp. 296–297) and second, the demands of integration and assimilation (Farris, 2014, p. 296). The production of material and symbolic difference is, in other words, entangled with forceful calls, as well as concrete measures, to regulate, control, and refashion Muslims’ lives and subjectivities. The “Muslim Question” can thus be considered as a form of what Foucault calls governmentality, or “a mode of power concerned with the maintenance and control of bodies and persons, the production and regulation of persons and populations, and the circulation of goods insofar as they maintain and restrict the life of the population” (Butler, 2004, p. 52).

In this article, we seek to further think through (the analytic of) Europe's “Muslim Question” by means of approaching it from one particular angle, namely the discursive and conspiratorial use of demographics as an alleged threat to Europe. The problematization of Muslims in Europe is particularly and anxiously concerned with demographics, and more particularly with two key demographic processes determining the size and composition of a population, that is, birth and migration. Discourses on “waves” or “floods” of migration as well as on high birth and fertility rates among “migrant” populations have gained considerable traction all over Europe in the past decades, and provide fertile ground for the “fear of replacement.” Within the context of the “Muslim Question,” this fear entails that Muslim populations will “replace” the white/Christian populations that are considered to be “native” to Europe. This predicament, moreover, is often framed as the result of a deliberate and combative strategy on the side of Muslims, and hence labeled as “demographic warfare” and “demographic Jihad.”

We investigate this contemporary discourse of “replacement” in its articulation with Europe's “Muslim Question,” and as a prism into that question, in the following manner. First, we offer a concise and schematic account of the rise of the “replacement” discourse through a brief discussion of some of its major articulations. Borrowing from Kyra Schuller (2018) we propose reading this discourse as a palimpsest, a discourse that accumulates layers through time, a discourse in which every (re)iteration adds layers of meaning (fiction, statistical, racial, conspiratorial, theological), while still bearing traces of or keeping intact the core idea (a deliberated Muslim plan to replace “native” European populations). Second, we do a close reading of two recent images that juxtapose life and death as imagined within the replacement discourse, and that capture that discourse in powerful albeit disturbing ways. We selected these images because they represent nodal points of the current demographic discourse, while at the same time also being incitements to discourse. Finally, our close reading of these images provides the ground to develop an argument on biopolitics and also eugenics in the context of the “Muslim Question;” we argue that demographic questionings and biopolitical‐eugenic answers constitute a key discursive site where the “Muslim Question” articulates and unfolds nowadays.

2. LE GRAND REPLACEMENT: THE PALIMPSEST OF DEMOGRAPHIC WARFARE

Over the past decades, Muslims and Islam in Europe have increasingly been framed and approached through the specter of demographics, in which the optic of migration, always already framing Muslims as recent arrivals to Europe (thereby erasing both long‐standing colonial entanglements and century old and deep‐rooted Islamic presences in various parts of Europe), has been increasingly joined by an optic of birth rates. From seemingly innocuous reporting on how the most frequent given name to newborns in certain cities or neighborhoods is now Mohammed instead of Jan (in Brussels) or Hans or Johann (in Berlin) (Bruzz, 2018; BZ, 2019) to heated and racially charged polemics, such as Austria's first baby of 2018 derogatively being called “a newly born terrorist” (Torrens, 2018), there is a heightened public interest in the procreation of Muslim populations. This interest, and sometimes moral panic, is part of a more elaborate discourse that has developed under various signatures, such as “demographic jihad” or “population replacement,” that suggest that those populations who consider themselves native to Europe—that is, white and Christian populations—fear they will soon be outnumbered and thus “replaced” by Muslims.

While its core ideas have been in the making for several decades, the discourse has expanded significantly in the last two to three years in a synergic interplay between marginal extreme right‐wing political subcultures—in the meantime readily referred to as the alt_right—and mainstream and best‐selling authors and commentators.5 We have seen the rise of a conspiratorial‐confrontational genre with slight national variations, but overall committed to paint a civilizational chasm between Islam and the West in general, and Europe in particular, in which Muslims are systematically depicted as a problematic population posing a series of difficulties and menaces to Western societies and governments. This discursive genre, moreover, portrays a waning and decaying Europe that is going through “civilizational decline” as well as a “demographic winter,” and needs to be defended against Muslims and Islam. In what follows, we give a brief account of the main arguments of this discourse of demographic threat, as they are developed and disseminated through best‐selling books and authors. We also highlight how this discourse over its period of formation and proliferation has acquired layers of meanings through its different iterations, rendering it, as it were, into an unfinished palimpsest.

One of the first post‐colonial elaborations linking demographic concerns about the high birth rates of non‐Europeans with the destruction of Europe can be found in Jean Raspail’s (1973) apocalyptic novel Le Camp des Saints. The novel is structured around a single and straightforward plot: one million desperate and starving Indians embark on one thousand old ships from the Ganges to Europe, and through a set of contingencies they end up on the shores of southern France. The Indians are led by a nameless character identified only as a “giant turd eater,” who is accompanied by a child‐monster of evil character (Raspail, 1973, pp. 9–12). Once the plot is set up, the novel alternates between the reactions of different sectors of French society (the media, politicians, a professor) toward the imminent arrival of the ships and the immigrants, and the description of what transpires on the ships. According to Jean‐Marc Moura (1988, p. 119), Raspail developed and turned neo‐malthusian concepts—proper to the 1970s and concerned with the relationship between estimated global population growth and the depletion of resources—into a fiction that heavily resonated with the rise of the “new far right” in 1970s France and its vociferous opposition to migration. In Raspail's racially charged nightmare, migration from the “Third World” would eventually bring the apocalypse of the West (the book opens with an epigraph of the Bible's book of Revelation, setting up the eschatological tone of the novel), beginning with France yet expanding throughout Europe. Once the migrants reach the French coast, they embark upon a path of destruction and murder heading into the continent, and they are joined by migrants who were already there (Arabs) and French anarchists. The novel concludes with the destruction of Switzerland.

Mounted on the liberty provided by fiction, The Camp of Saints inaugurates a genre that in the ensuing decades will find translations into history, sociology, theology, demographics, and political sciences, and where the destruction of Europe is produced by the convergence of two processes. On the one hand, the migration of non‐Europeans to Europe—migrants who allegedly have higher birth rates compared to Europeans, and who are considered to inaugurate a process which will eventually lead to a deleterious transformation of the social, political, cultural, and “racial” make up of European societies. On the other hand, the complicity of (weakened) European elites, who take part in the destruction of Europe, by—willingly or not—enabling and accepting “waves” of migrants who end up shattering the meanings of what is supposed to be European. The convergence of these two processes mobilizes the call to defend Europe, including the call for a stronger European leadership with a more aggressive stance towards migration. This genre, moreover, is framed within a Manichean and confrontational world view, antagonizing the West versus the Rest, to use Stuart Hall’s (1992, p. 275) phrase.

In a paragraph capturing the fears and anxieties of an imminent racial war, Raspail narrates a scene worth quoting at length since it delineates many themes of the demographic warfare palimpsest that will continue to appear in the following decades through new iterations. While chaos reigns the shores of the Ganges, a local Indian official has a phone conversation with a Belgian consul, explaining to the consul the following:

Look here, my friend. Why cling to the hope that my government still has some say in all this? What’s happening out on those docks is the fringe of the problem, the part we can see. Like the lava that shoots up out of the crater. Or the wave that breaks on the beach … Yes, that’s what it is, a wave, with another one rolling behind it, and one behind that, and another, and another. And so on, out to sea, back to the storm that’s the cause of it all. This mob of poor devils attacking the ships is just the first wave. You’ve seen their kind before. Their misery is nothing new, it doesn’t upset you. But what about the second wave, the one right behind? Would it shock you to learn that thousands more are on the move? Half the country, in fact. Young ones, handsome ones, the ones that haven’t even begun to starve … The second wave, my friend. The beautiful creatures. God’s perfect specimens, these people of ours. Like statues, in all their naked glory, out of our temples and onto the road, streaming toward the port. Yes, ugliness bowing to beauty at last … And behind them, the third wave, fear. And the fourth wave, famine. Two months, my friend, and five million dead already! … Then the wave we call flood, stripping the country, destroying the crops, laying waste the land for five long years. And another one, off in the distance, the wave of war. More famine in its wake, more millions dead. And another, still nearer the storm, the wave of shame. The shame of those days when the West was master of our land . . . But through it all, through wave after wave, these people of ours, rubbing bellies for all they’re worth, to their bodies’ and souls’ content, to bring more millions into the world to die … Yes, that’s where it all begins. That’s the eye of the storm, no matter how it’s hidden. And you know, it’s really not a storm at all, but a great, triumphant surge of life … There’s no Third World. No, not anymore. That’s only a phrase you coined to keep us in our place. There’s one world, only one, and it’s going to be flooded with life, submerged. This country of mine is a roaring river. A river of sperm. Now, all of a sudden, it’s shifting course, my friend, and heading west … (Raspail, 1973, pp. 14–15 [our emphasis])

The Indian official announces “the end of the Third World,” by which he means the end of the West, through a “surge of life,” represented by “a river of sperm.” The image that Raspail conjures up establishes the life of the Other as tantamount to the death of Europe. The fertility of migrants washing up on European shores carries the seed of Europe's destruction. The Camp of Saints mobilizes and weaponizes the construal of non‐Europeans’ higher birth rates and migration as a deliberate and unstoppable warfare tactic against Europe. In the novel at large, and this paragraph in particular, Raspail unfolds the blueprint of a discourse that will, slowly but steadily, burgeon throughout Europe and the US, and is elaborated in multiple sites and in different layers, yet has become particularly attached to the Muslim subject.6

An early scholarly articulation of this discourse can be found in Samuel Huntington’s (1993) highly influential essay The Clash of Civilizations?, later developed into a monograph with the same title, albeit without a question mark (Huntington, 1996), which became a highly influential layer within the palimpsest of demographic warfare. Future global politics and wars will not be between ideologically opposing super‐powers as in the Cold War era but rather between civilizations holding diametrically opposed cultural values, Huntington argues. In this scheme, Islam represents the ultimate threat to Western civilization for, according to Huntington, “Islam has bloody borders” (Huntington, 1993, p. 35), that is, where there is Islam there will be blood. This menace emerges not only from Islam's assumed link to violence, but also from its demographics: “Islam is exploding demographically with destabilizing consequences for Muslim countries and their neighbours” (Huntington, 1996, p. 103; for a critique see Said, 2001). This demographic explosion, he continues, has been particular expansive in the age cohort of 15 to 24 years, which “provides recruits for fundamentalism, terrorism, insurgency, and migration” (Huntington, 1996, p. 103). Ever since its publication, The Clash of Civilizations thesis became a paradigmatic and highly influential frame positing a belligerent argument to understand world politics as the outcome of the warlike confrontation between the West and Islam.

At the beginning of the 21st century, in the wake of the War on Terror, the concern with demography was elaborated more systematically and burgeoned all over Europe. A crucial concept in this further development is that of Eurabia, which succinctly captures many of the themes of Europe's “Muslim Question” and the demographic warfare trope. Eurabia functions as a nodal point articulating different interrelated discourses: the problematization of Muslims writ large, the idea of Europe waning, and the demographic threat posed by Muslims which is also linked with the construal of Muslim hypersexuality, or, as it is sometimes labeled, “Muslim fecundism” (BareNakedIslam, 2013). The Eurabia narrative can be seen as embedded within the wider frame of Huntington's clash of civilizations and echoing Raspail's ordeal, but it adds extra layers in the form of conspiracy theories of an alleged plot of Muslim domination, and the waning of a complicit Europe. Oriana Fallaci (2004; for a critique of the Eurabia conspiracy see Carr, 2006; Bangstad, 2013) was the first author to seriously popularize the term Eurabia in her best‐seller book The Force of Reason.7

According to Fallaci, Eurabia is the code word for a not‐so‐hidden conspiracy between Arab and European government elites, plotted in 1974 with the end goal, as it were, of sending Arab immigrants to Europe in exchange for oil (Fallaci, 2004, pp. 137–138). Given that “the sons of Allah breed like rats” (Fallaci, 2002, p. 137), Fallaci concludes that “Europe is no longer Europe, it is ‘Eurabia’, a colony of Islam” (Fallaci & Varadarajan, 2005). Leaving the dehumanization of Muslims and the irony of portraying Europe as colonized aside for a moment, Fallaci's relevance in regard to the development of the population replacement discourse resides in her mainstream articulation of “Muslim hypersexuality” and higher birth rates with an upcoming calamity, that is, the destruction of Europe. In a sense, Eurabia takes Huntington's idea of “Islam exploding demographically” to the arena of secret plots and conspiracies, as the demographic explosion in Fallaci's writings is not only the outcome of “natural” processes, but also a deliberate and combative Muslim strategy.8

The term Eurabia became even more prominent through the writings of Giselle Litman, pen name Bat Ye’Or (2005), and the publication of her book Eurabia: The Euro‐Arab Axis. Although Fallaci and Ye’Or predicate the same conspiratorial fears, Ye’Or's exposition takes on a more academic tone and structure than Fallaci's, and as a result Ye’Or's publications are couched in an aura of scientific validity. In Eurabia, she fleshes out the alleged secret plan whereby European civilization has become “subservient of the ideology of jihad and the Islamic powers that propagate it” (Ye’Or, 2005, p. 9). According to Ye’Or, this secret plot has been transforming Europe culturally as well as demographically by means of an “increasing Islamic penetration of Europe” (Ye’Or, 2005, p. 10 [our emphasis]) that will result in the “alteration and substitution of one civilization by another” (Ye’Or, 2005, p. 35). In short, Europeans will be “substituted” by Muslims.9

Ever since Ye’Or's publication, the discourse proliferated in different arenas and across borders, with books developing eerily similar lines of argument such as Melanie Philips’ (2006) Londonistan: How Britain Is Creating a Terror State Within, and Bruce Bawer’s (2006) While Europe Slept: How Radical Islam Is Destroying the West from Within, to mention only some of the most prominent ones (see also Murray, 2017). These publications keep adding layers to the palimpsests of population replacement, making it local, that is, London, or mixing the demographic threat with Islamic terrorism, while highlighting the alleged complicity of European governments and elites.

In the 2010s, the Islamic demographic threat discourse was further “refined,” and made salonfähig, notably in Germany by the politician and writer Thilo Sarrazin (2010) through the publication of his best‐selling book Deutschland schafft sich ab (Germany Abolishes Itself). While taking up the same themes present in the writings of Fallaci, Ye’Or, and Philips, Sarrazin frames his argument in a sociological fashion and relies on the “hard facts” of statistical knowledge (for a statistical critique of Sarrazin's theses see Foroutan, 2010). With Sarrazin, Raspail's nightmares have become full‐fledged “facts.” At the outset, Sarrazin presents himself as concerned with the current and prospective economic consequences of the current demographic trends in Germany, for the birth rates of the “smarter” and accomplished “native Germans” (einheimische Deutsch) (Sarrazin, 2010, pp. 60–62) are dwindling vis‐à‐vis the birth rates of the underachievers and the more prone to criminality Muslim migrants (Sarrazin, 2010, pp. 260–262). By deploying statistics to “prove” the demographic threat and the displacement of “native Germans” by Muslims in Germany, and by presenting himself as an academic expert, Sarrazin mainstreamed, in German‐speaking countries, the thesis of the higher birth rates of Muslims as a menace leading to a displacement (Verschiebung) of the German population and eventually to Germany's self‐destruction. Sarrazin's portrayal of the demographic threat, moreover, postulates different levels of hereditary intelligence between the German “native population” and Muslims, the latter being depicted as underachievers in schools. The higher birth rates of Muslims will therefore ultimately result in Germany “becoming dumber” (Sarrazin, Ulrich, & Topçu, 2010).

In 2018, Sarrazin published another book centered on the demographic threat, now relabeled as Feindliche Übernahme (Hostile Takeover). Here, Sarrazin develops an iteration of the discourse not in terms of statistics but on the basis of the Qur'an, where he “seeks answers” for his “concerns” (Sarrazin, 2018, p. 12). For Sarrazin, the Qur'an functions as a window to understand Muslim mentality (Sarrazin, 2018, p. 21), whatever that might be. Once more Sarrazin predicts the population displacement of “native Germans” as the majority by Muslims, but this time the root of the problem is a cultural one, that is, the “Muslim mentality,” which, in turn, is exclusively formed and shaped by the Qur'an. To the palimpsest of population replacement Sarrazin has added a biopolitical deployment of statistics, upon which he has written Orientalism's textual attitude, namely, the epistemological premise postulating that everything that Muslims do and think can be understood by referring to the Qur'an (Said, 1978, p. 93).

While Germany Abolishes Itself made waves in the public debate in Germany, the novelist and essayist Renaud Camus delivered a speech entitled Le grand remplacement (The Great Replacement) in a small town in the south of France.10 Camus’ formulation would give the discourse emerging in different places in Europe, and drawing on different terms (such as alteration or substitution), one of its more recognizable epithets, that is, the replacement thesis. Camus’ diagnosis of replacement relies on a stark distinction between “an official doctrine” which approaches the French nation in more legal terms—that is, of a citizenry that is founded on a formal principle of equality of citizens—versus an ethnic or racial “common sense” of belonging. According to that “common sense,” Camus asserts, France has become unrecognizable. To make this distinction between “official doctrine” and “common sense” tangible, Camus mobilizes the figure of a hijabi woman who asserts, “I am as French as you are” (“je suis aussi française que vous”) (Camus, 2011, p. 19). In Camus’ eyes, this figure is “crushing” and “difficult to tolerate” (Camus, 2011, p. 19), as she takes the tension between the “official doctrine” and “common sense” to an “unbearable extreme.” If her claim to French citizenship holds, Camus argues, to be French has become meaningless, and France has been reduced to a territory. Camus’ line of argumentation, which is drenched in a sentiment of loss and nostalgia, effectively and dangerously erodes and berates the juridical underpinnings of contemporary definitions, regulations, and practices of citizenship. He understands those to be rooted in the “absurd” affirmation that only one “species” (espèce) of French exist, which he considers to be the result of the “dogmatic anti‐racist regime” that came into being after the Second World War and made it impossible to speak of racial distinction. Thus, according to Camus, “replacement” also occurs in language,11 and part of the war is semiotic. For Camus, there is no doubt that different “species” exist among the current French population, and “race” is a way of distinguishing humanity and conceptualizing the French—as a race, whose “replacement” is obscured and facilitated by the formal and legal categories of citizenship currently in place. In sum, Camus attacks a civic‐legal notion of citizenship, and asserts a racial conceptualization of the national population. Unsurprisingly, this racial thinking comes with an arresting dehumanization of non‐white French in general and Muslims in particular—a dehumanization that is perhaps most on display when Camus speaks of Muslims in France as “replacements” (“remplacants”).

It is clear that Camus, and indeed many of his followers, approach the current state of population dynamics as a situation of war. Camus, more specifically, talks about colonization. Quoting Frantz Fanon (which he names as one of his favorite authors), Camus deplores the “enslavement of indigenous populations” of France. And while this strikes us as an ironic reversal of the positions of colonizer and colonized entrenched in the history of European modernity, there is little sense of irony nor reversal in Camus’ writings: he takes on a negationist stand towards colonialism as he asserts that the French never really colonized (Camus, 2011, p. 55). He suggests, moreover, that North African, previously colonized populations have long been focused on colonizing Europe. This joins a prominent trope elaborated within Eurabia conspiracy theories, which Camus “substantiates” with a quote from Houari Boumédiène's speech at the UN in 1974, in which the Algerian political leader would have said:

One day, millions of men will leave the Southern Hemisphere to go to the Northern Hemisphere. And they will not go there as friends. Because they will go there to conquer it. And they will conquer it with their sons. The wombs of our women will give us victory. (Quoted in Camus, 2011, p. 53)

Suggesting a deliberate plot to replace Europe's native population by means of higher birth rates, these words perfectly align with the key ideas of the replacement thesis. The quote, however, is fabricated. Boumédiène did deliver a speech at the UN in 1974 in the context of discussions on international prices of raw materials and that speech contains nothing even remotely close to these words nor ideas.12 Yet this is a powerful fabrication that “works”—that is to say, it captures the minds and attention of many, as it became a widely shared meme in the right‐wing blogsphere that supposedly lays bare, in a very concise manner (i.e., in a meme‐able quote),13 the “real intention” of postcolonial (Muslim) migrants to Europe. The quote thus articulates a myth at the heart of conspiracy theories that are part of Europe's “Muslim Question,” as it succinctly captures some of the ideas central to anti‐Muslim racism: migration of Muslims to Europe as colonization, as conquest, and the central role of demographic and reproductive warfare in that conquest. This renders the quote into a conspiratorial fabrication that operates, we argue, at the very heart of Europe's “Muslim Question” in a fashion not unlike the manner in which the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, fabricated in the early 20th century, was operational at the heart of the Jewish Question, that is, as a way to “prove” and incite fear of religious/racial “others” who are allegedly conspiring to dominate white and (culturally) Christian Europe. Even though the Protocols and contemporary conspiracies such as Ye’Or's Eurabia or Camus’ Great Replacement differ significantly in terms of their context of appearance and content, the conspiracies “display strikingly similar discursive dynamics in their attempt to racialize Jews and Muslims as the ultimate Other determined to destroy Us” (Zia‐Ebrahimi, 2018, p. 314).

While this demographic discourse, both in terms of content and confrontational style, is situated in a postcolonial and contemporary context, it can be approached as an articulation of what Foucault (1997) has identified as the discourse on race war or race struggle (Foucault, 1997, p. 65). The historical discourse on race war posited the understanding of history, social relations, and power as the outcome of “a confrontation between races” (Foucault, 1997, p. 69). The race war discourse, furthermore, was structured and predicated upon a binary conceptualization of society, two races, “them and us” (Foucault, 1997, p. 74). Following Foucault's (European) genealogy, this discourse was subjected to a series of important changes during the 19th century. First, the war, the struggle itself was conceptualized differently, “it is no longer a battle in the sense that a warrior would understand the term, but a struggle in the biological sense: the differentiation of the species, natural selection, and the survival of the fittest” (Foucault, 1997, p. 80). Second, society is no longer seen through a binary prism, instead it is approached as a whole “threatened by a certain number of heterogenous elements which are not essential to it … hence the idea that foreigners have infiltrated this society” (Foucault, 1997, p. 81). At this point racial discourse took over and reworked the race war discourse, and then the idea of “race purity replaces that of race struggle.” In similar yet ongoing fashion, the “population replacement” discourse appraises history and social reality as driven by a struggle between the West and Islam—this war or clash is underpinned by cultural and biological themes and a concern for the survival of Europe or the West, threatened by the infiltration of foreigners who calculatedly seek to overtake Europe through migration and birth rates.

Our discussion has focused on mainstream(ed) articulations of the discourse on replacement, yet we are fully aware that this discourse is developed in interplay with a large field of more fringe right‐wing commentators and blog writers as well as (far) right‐wing political groups. The replacement thesis has proliferated in the blogosphere, on sites such as the Gates of Vienna and Jihad Watch from the US, and Politically Incorrect from Germany, where more virulent, aggressive, and racially charged layers have been added, and where labels such as “Demographic Jihad” and “Muslim fecundism” were coined (Furness, 2017; Truthies, 2018). A myriad of far‐right groups, moreover, has embraced, embedded, and predicated the construal of the demographic threat into their political platforms. In France, Marine Le Pen—an admirer of Raspail's fiction—has taken on Camus’ thesis in her political speeches from 2011 onwards (Valerio, 2013). By the time the nationalist and anti‐Islam movement Pegida (Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamization of the Occident) rises in 2014, first in Germany but soon with local groups all over Europe, it is able to solidly build on the demographic replacement discourse and call for a defense of the “occident” [Abendland] against an ongoing Islamization, which in its view comprises not only the construction of mosques on German soil and the arrival of Muslim refugees, but also a population replacement of “native Germans.” And while Pegida represents a far‐right movement outside of the parliamentary arena, various political parties have appropriated the language and images of Pegida in their own political campaign, such as the AfD in its 2017–2018 electoral campaign in Germany, or the Forum voor Democratie 2019 campaign in the Netherlands. Today, almost every European far‐right political party has adopted the discourse on Islamic demographic threat and relies on its dissemination to succeed.14

While a careful study of the interplay between the more far‐right fringe and the mainstream commentators falls beyond the scope of this article, we do want to comment on one feature of this interplay that struck us while researching the mainstream(ed) demographic anxieties: even though both the Eurabia literature of the 2000s and the replacement thesis literature of the 2010s comment elaborately on what they consider to be problematic about the current make‐up of the population in West European countries, their diagnoses tend to focus on migration, cultural erosion, or the imminent danger of Islam, while shying away from the question of procreation. Moreover, when biological reproduction does come to the foreground, it isn't always in ways one might expect: Camus, for instance, is outspoken about how nationalist natalist politics and “more French (meaning white) babies” cannot be a solution to the problem as he sees it. This is due to his neo‐Malthusian take on today's ecological crisis, a concern that also appears in Sarrazin's statistical diagnosis. If the mainstream(ed) authors come up with political solutions, they tend to focus on the realm of cultural politics (affirming norms and values), border regimes (limiting migration), and (revoking) citizenship. Camus, for instance, suggests to revoke French citizenship from those who do not “associate with France” (Camus, 2011, p. 24) as he puts it—an idea that is gradually finding its way into legislation and citizenship reforms all over Europe (Camus, 2011, p. 62).15 Sarrazin on his side, is more focused on optimizing German productivity and global competitiveness by making up a population of the “smartest” and “most qualified,” that is, “native” Germans. In sum, while these authors paint catastrophic pictures about the current situation, their calls for action remain both general and vague as well as limited to what we might call the biopolitics of borders and migration, and culture and citizenship. The biopolitics of procreation and indeed eugenics are tangible but, by and large, remain unspoken. This shifts drastically when considering the written and visual material produced by more fringe far‐right commentators, who do put forward calls for action as well as political solutions in terms of biological reproduction—in particular a call for “more white babies.” In some of these more extreme calls for action, moreover, reproductive biopolitics go hand in hand with the necropolitics (Mbembé, 2003) of (calls to) terrorism: the ideas of Eurabia and great replacement were important factors in the white supremacist violence perpetrated by Breivik and Tarrant respectively.

The replacement discourse, moreover, is versatile: one of its recent notorious moments includes its mobilization at the white supremacy rally Unite the Right in 2017 in Charlottesville, US, where the chants “you will not replace us” and “Jews will not replace us” became prominent slogans of the demonstration. Drawing on Foucault (1997) and Stoler’s (1995) elaboration of discourses and their “polyvalent mobility,” we can consider the discourse on population replacement as an open text, subjected to multiple iterations whereby some core ideas are mobilized and coupled with older and newer discourses, targeting different populations and serving a plethora of political aims. The chant “Jews will not replace us,” for instance, does not seek to communicate a “demographic replacement” of whites by Jews, but rather that the latter are the ones orchestrating the replacement (ADL, 2017) and thus the population replacement palimpsest is threaded along with old anti‐Semitic conspiracy theories postulating “Jewish world domination.” The population replacement palimpsest, in other words, is not only mobilized against Muslims, but also against other “populations” who are constructed as threatening as they are seen as seeking to replace whites, as the 2019 murderous shooting in El Paso Texas showed.

3. “IT’S THE BIRTHRATES”: IMAGES OF LIFE AND DEATH16

We now turn to two images which we analyse in more detail with the aim of further unpacking this demographic discourse on the rise. The two images we selected are not so much representative as they are nodal parts of the discourse—as well as incitements to discourse. At the same time, the images differ in various respects: while one comes from the sphere of party politics and more specifically political campaigns, the other one belongs to the alt_right blogosphere. The messages they convey also differ, and in a sense the images are complementary and express an interplay or intertextuality: if one focuses on the need both to control who belongs to the nation as well as to produce “more white babies,” the other stresses the danger, the terror, of “too many Muslim babies.” Our analysis of these images relies on Stuart Hall’s (1997) approach to the examination of visual forms of representation. As Hall points out, the meanings of images are always ambiguous, that is, images carry several messages, which might even contradict each other. The work of representation entails the attempt to fix one particular meaning, to privilege one upon the other. This process occurs through the proliferation of dominant discourses as well as through intertextuality. The latter can be understood as a process in which the meanings of an image accumulate when read across other images and forms of representation (Hall, 1997, p. 232). Concretely, we follow Hall’s proposition to subject images to two levels of analysis: the denotative, that is, the description of the event, and the connotative, the suggested or implied meanings of the image. Our analysis of the connotative level, furthermore, is complemented with W. J. T. Mitchell’s proposition of shifting the location of desire to images, and interrogate “its construction of desire in relation to fantasies of power and impotence” (Mitchell, 1996, p. 77).

As part of its political campaign for the German Federal Elections in 2017, the far‐right political party Alternative for Germany (AfD) developed a series of 10 posters to be displayed nationwide epitomizing their political program, as it were, its alternative for Germany's future (AfD, 2017a). Nearly all of the posters directly or indirectly referred to Islam, Muslims, and migration as problems for that envisioned future. One of the posters, entitled “New Germans? We'll make them ourselves; Trust yourself Germany” [Authors’ translation], (AfD, 2017b) depicts a pregnant white woman lying on a blanket in the grass on a sunny day. While we don't see her entire face, and as such she is not an individually recognizable woman—she might be any white woman—we do see a wide, confident smile. With one hand she touches, in a protective manner, her partially uncovered belly, which is visibly pregnant. She wears jeans and a striped t‐shirt white and blue, the colours of the AfD (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

‘New Germans? We'll make them ourselves, trust yourself Germany’ (Valodnieks, 2017) [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Denotatively, the caption stabilizes the preferred meaning of the image: this is about regulating and controlling the contours and content of the German population. The question “who is German?”, the post asserts, should be decided by “we,” the Germans. The text suggests that Germany has lost its confidence to settle this question, and mobilizes Germans to regain that confidence. In the interplay between image and text, the poster mobilizes the idea of women as the symbolical, cultural, and biological reproducers of the nation (Yuval‐Davis, 1996)—this includes the well‐established trope of representing the nation as female as well as nationalist norms of making women responsible for the “proper” reproduction (both cultural and biological) of the nation (Yuval‐Davis, 1997), which encompasses preventing and punishing miscegenation (Goldberg, 2002). The poster conveys multiple messages when it comes to the German nation and its reproduction. The text suggests that something is wrong with how “new Germans” are currently conceived of, and it is time to change this conception. “New Germans” typically refers to former migrants from the 1960s “guest worker” programs and their line of descent ad infinitum. Ultimately, the belated reform of German citizenship in 1999 supplementing the ius sanguinins principle with a ius solis one, allowed many long‐time residents to formally acquire German citizenship. This reform, however, did not shatter the racial construction of Germanness as whiteness, and the construal of being German exclusively through (white) heredity. Thus, the qualification “new” has come to function as a mark of distinction, a form of racial characterization, suggesting indeed that there are different “kinds” of Germans, and that some Germans, allegedly “new arrivals” to Germanness, might structurally be cast in the position of never being able to fully arrive (Boersma & Schinkel, 2017). These “new Germans” continue to have “a migration background” that routinely is associated with problems and deficiencies. By questioning the current making of “new Germans” the poster is questioning the 1999 citizenship reform that gave birth, so to speak, to “new Germans,” or “Passport Germans” as the AfD also likes to call them.17 As such, the poster seeks to refute the current citizenship regime and its formal and legal understandings of German nationality, and calls upon Germans—“old” Germans, who are white Germans—to have the confidence to “make” “new Germans.” The text, in other words, questions the social reproduction of the German population at large, and does not necessarily refer to biological reproduction: “new” Germans can notably be made by new citizenship laws. Yet the visual focus of the image, the pregnant belly, immediately puts the question of birth rates center‐stage. The poster thus represents a key moment within the discourse on replacement: the division of labor which we observed between more mainstream and fringe texts is recast within this poster, in the interplay between text and image. As a result, questions of migration and procreation are firmly articulated with each other: the more established (anti)migration discourses usher in the public's attention and unabashedly direct that attention to the question of procreation. The call for Germans to take care of the social reproduction of the nation at large, in other words, confidently puts procreation at the center of that project and suggests that white Germans ought to make (real) “new Germans.” While there is no partner in sight, the message the AfD seeks to convey would not work if the partner and the baby were non‐white. Against the background of an ageing population, stagnant birth rates, and the construction of migration as a threat to German values, identity, and ultimately to Germanness, the poster envisions a future where the German population would ideally be homogenously white.

With W. J. T. Mitchell’s (1996) question “what does this picture want?” in mind, we might say that the election poster aspires to mobilize the targeted subject, namely, the adult white German voter, to three actions: first, to trust the AfD and vote for it in the elections; second, to revise established and formal notions of “new Germans” in the current public debate; and third, to biologically reproduce and “make new Germans.” The poster thus seeks to stimulate the feeling of trust in a twofold manner, trust in the AfD, and trust in oneself, in one's Germanness. At the same time, tacitly, it also incites to heteronormative and reproductive intercourse. These desires compressed in an image and a few lines of text are further articulated in the AfD’s political manifesto (AfD, 2016). In the chapter devoted to Family and Children the party is clear on wanting “Larger families instead of mass migration” (AfD, 2016, p. 41). In the discussion of family politics, the AfD lays out the challenges—in equilibrium and health—that the German population faces, and appraises that “mass immigration, mainly from Islamic states” (AfD, 2016, p. 41) will only accelerate deleterious ethnic‐cultural changes in the German population, for migrants from Islamic countries “attain below‐average levels of education, training and employment” (AfD, 2016, p. 41)—an argument copy‐pasted from Sarrazin's textbook. Migrants from Muslim countries, the argument goes, do not integrate into German society. This will only lead to a “critical escalation of the demographic crisis” (AfD, 2016, p. 42). Furthermore, the AfD’s envisioned politics also take as a focal point of concern abortion for (white/real) German women, since the party “welcomes all unborn and newborn children” (AfD, 2016, p. 43). They subsequently criticize the “exempt of punishment” for interrupted pregnancies due to social reasons, which according to their estimations represents around 97 per cent of all abortions in the country. In sum, the poster, in conjunction with the AfD’s manifesto, articulates different dimensions of the population replacement palimpsest and suggests two interrelated biopolicies should be implemented. Moreover, it raises a twofold concern regarding German demographics, (a) the deleterious effects of migration from so‐called Islamic countries; and (b) the need to revise and even reform who belongs to the German body politic. At the same time, and more particularly on the visual level, the poster puts biological reproduction center‐stage, as it, in a suggestive manner, raises the question of not having enough white babies, while offering a solution to it that establishes control over women's bodies, and incites white reproduction.

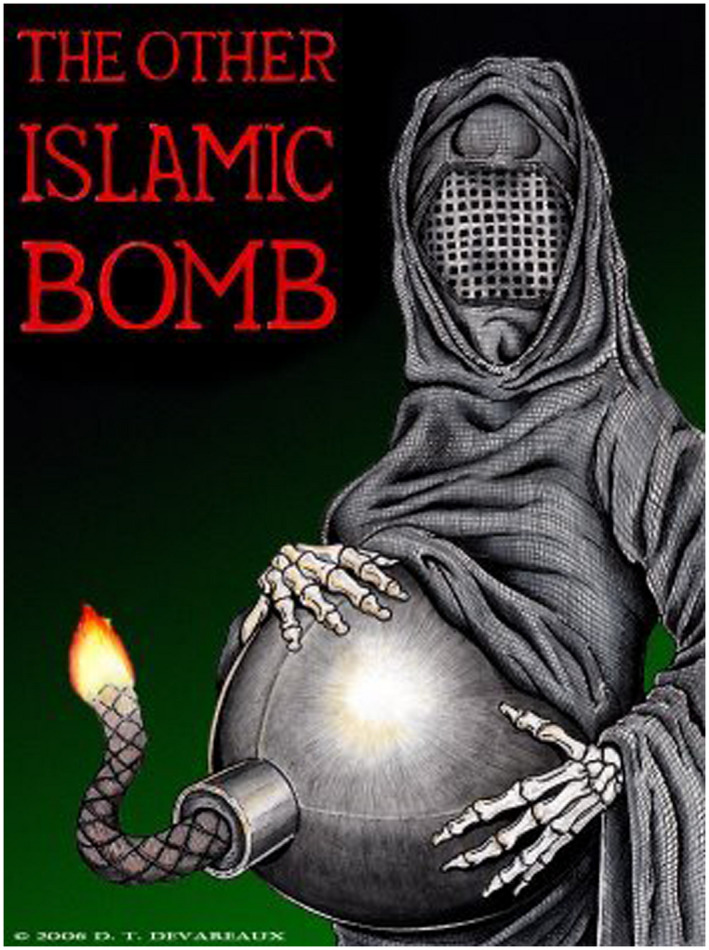

To the AfD electoral poster campaign, which represents an image that was easily accessible in the public sphere during the election period, we want to juxtapose another image, more explicit and disturbing, which circulates widely within the alt_right blogosphere.18 In a cartoon called “The Other Islamic Bomb”, blogger D. T. Devareaux (2006a) visually articulates the sense of an Islamic external threat.19 The cartoon portrays a heavily pregnant female figure, dressed all in black. This female figure also remains faceless, yet this time not because of the framing or cutting of the image, but due to what in global media is represented as the “Islamic garb” par excellence, that is, the burka. This woman also touches her pregnant belly, with a protective gesture of her hands. Yet her hands represent death: they lack human flesh and skin and consist merely of bones. With skeleton hands and a black cloak hiding her face, she invokes the mythical personification of death, the Grim Reaper, whose face we don't get to see, as the story goes, until the moment he comes to collect us. This image, too, is visually centered on a pregnant belly, yet this belly does not stand for life, but is represented as a ticking bomb about to explode. She is thus carrying, and will be giving birth to, death and destruction—in just a matter of time (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

“The other Islamic bomb” (Devareaux, 2006a) [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

This cartoon activates two racial tropes through allegorically signifying a double death. The first trope, instant and literally explosive, conjures up the figure of the Islamic terrorist, the suicide bomber blowing up himself (and only rarely herself) with the final goal of destroying the West. This racial figure both inhabits and exemplifies what Talal Asad (2007) pointedly analyses as (the dominant representation of) the “Islamic culture of death” and Salman Sayyid (2014, p. 4) conceptualizes as one face of the “Double Muslim,” that is, one “of the most iconic images of the War on Terror” who represents the “fanatic par excellence,” bringing immediate and explosive death to enemies and to himself. In terms of gendered representations, the cartoon is striking in different ways. Moreover, it represents a quintessential figure of femininity, that is, a pregnant woman. At the same time, her gender is more ambiguous, because of the garb she dons (the burka is often suspected of “concealing what is underneath,” and more specifically of possibly concealing a man and/or a bomb), the (male) trope of the suicide bomber she embodies, and the (male) mythical figure of death she personifies. We might understand this as an effect of the deep representational connection between violence and Muslim masculinity at large—as, for instance, expressed by the Dutch right‐wing politician Geert Wilders when he characterizes Muslim and migrant men as “Islamic testosterone bombs” (Al Jazeera and AP, 2019). In order to emphasize her violent character, in a way that overrides the vulnerability that often marks representations of pregnant women, she needs to display some signs of a soldier, some suggestions of masculinity—while the femininity of her pregnant belly remains center‐stage. This is violence, death, and destruction by a careful (her protective hand) and nurturing (her life‐giving womb) conception of life. Her fertile body embodies death—by (bearing) Muslim life. Hence, a basic signifier of life—pregnancy—is turned into death, and the living body itself becomes a weapon of destruction (Mbembé, 2003).

Thus, the second death articulated by Devareaux's cartoon anticipates the future of the population to which she is the alien body, the Trojan horse, that is, a population that is European, Western, white. This individual “demographic bomb,” in other words, brings forth gradual death on a mass scale, as she is not alone. With an army of “demographic bombs” the European (white) population is slowly but steadily replaced by Muslims by means of calculated higher birth rates, echoing the fabricated quote of Boumédiène. She is therefore an apocalyptic figure, announcing the apocalyptic future feared by Raspail, which we might understand in terms of what Jasbir Puar (2007, p. xx) has qualified as paranoid temporality, a discourse of “negative exuberance—for we are never safe enough, never healthy enough, never prepared enough—driven by imitation (repetition of the same or in the service of maintaining the same).” The image, in short, constitutes the visual representation of the demographic replacement palimpsest, and indeed is often used as an illustration for alt_right blog posts or articles about “demographic warfare.” In an appalling fashion, it expresses the “weaponization of the (Muslim) womb” that these conspiracy theories consider to be central to the postcolonial predicament and that we consider to be central to the construction of the “Muslim Question.”

Turning once more to Mitchell’s (1996) question “what does this picture want?” we might argue that, in line with its (alt_right) context of production as well as its (meme‐like) format, this image seeks to powerfully, disturbingly capture and convey the meaning as well as the threat at the heart of the replacement theory, and further disseminate it. And it is drenched in a not‐so‐subtle desire as well as incitement: this reproduction of life‐death, this replacement, must be halted.

4. BIOPOWER AND EUGENICS

These kinds of representations, we argue, call for a closer scrutiny of and engagement with the technology of power centered on the production of the population as a political problem, that is, biopower (Foucault, 1997), and one of the myriads of techniques deployed by it: eugenics (Schuller, 2018). We now turn to a more elaborate discussion of how biopolitics and biopower can be understood as shaping and informing the population replacement palimpsest to then return to and offer a second reading of the images against the background of biopolitics and eugenics.

Although the notion of biopower was not coined by Foucault, he established the concept and approach as critical tools to examine the production and management of populations on the social scientific agenda.20 Ever since its Foucaultian elaboration, the concept of biopower has taken a life of its own, it has become a traveling theory (Willaert, 2012), subjected to further elaborations, amendments, and critiques. These critiques have expanded not only the Eurocentric architecture of the concept by taking into account how colonial history and the colonies “as laboratories of modernity” were crucial in the formation of this technology of power (Stoler, 1995, p. 15), but also amendments have appeared engaging with some of the precepts upon which Foucault built the concept, namely: his Eurocentric location of the “birth of racism” in the 19th century (Stoler, 1995; Weheliye, 2014); his limited and problematic conceptualization of race and racism (Weheliye, 2014); the insufficiency of biopower to capture contemporary forms of subjection of life to the power of death (Mbembé, 2003, p. 39), the sudden break between sovereign power and biopower (Sheth, 2011),21 as well as the preponderance of race over sexuality in Society must be defended (Schuller, 2018). In this sense, while we consider Foucault's concepts of biopower and biopolitics to be crucial in accounting for the appearance and proliferation of the population replacement discourse, it is also the case that questions of race, colonization, and dehumanization, which are central to the workings of biopower, remain undertheorized in Foucault's writings (see Bracke & Hernández Aguilar, 2020) and need to be brought to the fore when considering a discourse of population replacement, which, as mentioned, mobilizes different layers and categories of analysis. Population replacement discourse seeks to reverse European colonial history and erode existing legal understandings of citizenship, while activating racial tropes and an idea of race war. Moreover, this discourse, centered as it is on life and death, also conjures up sex and sex differentiation.

As a technology of power focused on the production of the population as a political problem, biopower's emphasis centers on the human as a living being and therefore is concerned with “a global mass that is affected by overall processes characteristic of birth, death, production, illness and so on” (Foucault, 1997, pp. 242–243). It seeks to “treat the population as a set of coexisting living beings with particular biological and pathological features, and which as such fall under specific forms of knowledge and techniques” (Foucault, 1997, p. 367). Biopower, in other words, operates at the level of the production, control, and regulation of populations, and it does so by further crafting (racial) caesuras within the continuum of the population and by recruiting and proliferating racial differentiations with long histories (Weheliye, 2014) as well as sex and sexual categories of differentiation (Schuller, 2018). Biopower transformed the race war discourse in significant ways: the race war discourse transmuted into the idea that “We have to defend society against all the biological threats posed by the other race, the subrace” (Foucault, 1997, pp. 61–62) that lives among us, that is internal to the nation. Within the biopolitical frame the race war discourse was recoded as a prism to understand power relations and how they divide the social body, in which in order to live you must kill, which, in a racist logic, gets translated into “if you want to live, the other must die” (Foucault, 1997, p. 256). Within the biopolitical frame, racism performs a fundamental function, for it creates a break in the continuum of population, assigning value (life) to the superior race and lack thereof (death) to the inferior race, while also establishing a correlation between the life and death of the races. Killing the other race, in the context of the biopolitical race war, amounts not only to “the elimination of the biological threat” (Foucault, 1997, p. 256) but also to the improvement of the species, an issue unspoken but present in the AfD’s poster. However, as Schuller (2018) has argued, biopower's central aim of letting live (the superior race) and letting die (the inferior race) is not only predicated upon racial characterizations and differentiations, but, equally important, necessitates sex differentiation as the vehicle to incite and safeguard the reproduction of the superior race and thus of the national population.

One of the ways in which the analytics of biopower can be and have been extended, and which is particularly significant for our current discussion, is through thinking of eugenics. Even though Foucault recognized eugenics as one of the most important innovations in the technologies of sex (Foucault, 1997, pp. 7–10; Foucault, 1990, pp. 148–159), while also hinting toward the relevance of eugenics programs in the context of biopower, he did not fully pursue how, in effect, eugenics was a paradigmatic deployment of power both seeking to regulate sex at the individual level, and the health and safety of the population with the end goal of governing heredity transmission and thus the nation's stock, that is, the population. More recently, Kyra Schuller (2018) has unravelled the convoluted relations between eugenics and biopower, while expanding the analytics of biopower geographically—to the US—and conceptually, as being also informed by the sciences of impressibility. Schuller proposes a broad conceptualization of eugenics that is not reduced to the appearance of the gene as the ultimate decisive factor in heredity. In general terms, eugenics has been usually apprehended “as the early 20th century movement to encourage ‘fit’ women to increase their birth rate and to rob ‘unfit’ women of the capacity to conceive, an agenda that reached its nadir in Nazi Germany” (Schuller, 2018, p. 22). Albeit accurate, this understanding of eugenics does not consider the larger trajectory of the idea and the practices it prompted beyond German territory. Heredity, the focus of eugenics programs, was not always deemed immutable, but also impressible, Schuller argues, that is to say, it could be transformed, reshaped, and refashioned through experiences.22 In this sense, biopolitical eugenics has operated through two complementary frames—one purportedly fixed in genetic material and therefore deemed unchangeable, and the other approached as open and subjected to change through interventions—both, however, predicated upon the twinning of racial characterization and population's regulation and improvement. Having set the workings of biopower and eugenics as conceptual tools to approach the replacement discourse we return now to the images and read them under this light.

The AfD poster and “the other Islamic Bomb” meme share a set of interrelated themes and complement a vision hovering on life and death—lives that are worth living and lives that are not, lives that are worth protection and lives that are a form of death, lives that are at risk by the lives of Others, for “they love death as we love life” (Roy, 2017, p. 2).23 Both images express or suggest the “weaponization of the womb.” One image offers a concrete political strategy—a strategy or indeed a campaign one can vote for (and that more than 10% of the German population has voted for on several occasions)—that proposes white natalist politics in which the wombs of white women are mobilized to reproduce more white babies.

As we pointed out before, the white women's body is not represented in its entirety: the way in which parts of her body are cut off by the frame and her bodily integrity is not part of the representation, emphasize the part of her body that matters here: the womb. The weaponization, then, consists of how her womb is enlisted in a nationalist project (Yuval‐Davis 1996), that is, a warfare project of a white nation. The other image conjures up a spectacular fantasy of the “replacement thesis” in its most extreme form: here the birth of Muslim babies signifies the death of the West. Here “womb” is “bomb” is “tomb,” in a representation of the weaponization of the womb that is attributed to the “Islamic Other.” The womb of the “Other” becomes the Other's “other bomb.” Thus, this fantasy of the other is a mirror image of the Self, a projection of the Self, which portrays the weaponization of the white womb as merely a form of “self‐defense” in the face of horrific death. And the abundant light, background greenery, and wide smile surrounding the pregnant belly all convey the innocent character of this self‐defense.

Furthermore, it is possible to keep interrogating the images by asking what do they want in terms of lack, that is to say, what desires are articulated in terms of impotence, those desires that the image wants because it lacks them (Mitchell, 1996, pp. 77–78). In this vein, the AfD poster aspires to control and determine white reproduction, yet that desire reveals a lack, namely, the means to enforce positive policies aimed at procreating and reproducing the white population, and negative policies with the end goal of blocking those deemed unfit to reproduce. In the German context, the poster aspires to grant life to those deemed “native Germans” (einheimische Deutsch) and let die—or at least not continue living, as part of the Germany nation, in the future—those Germans “with migration background.” If only white “native Germans” were to procreate “new Germans” there is no possibility for “Passport‐Germans” or “Germans with migration background” to live. The poster desires eugenics. In terms of dormant desire, the image aspires to revive the absolute control over German heredity, a control that the AfD currently lacks.24 The image, therefore, can be seen as articulating the desires of the productive side of eugenics, it calls for policies oriented towards procreating those (considered to be native Germans) deemed fit to the healthy reproduction of the German nation. This call, moreover, necessitates seizing control over “native German” women's bodies.25 These desires, moreover, are also underscored by a historical intertextuality that must inform further readings of the image, that is, the background of Nazi propaganda with its own images, texts, and posters that called upon “Aryan women” to bear white children for Nazi Germany (Bock, 1983).26

In their interplay which is simultaneously complex and multi‐layered as well as a simple mirror, both images conjure up race, religion, gender, and sexuality. These categories are strategically deployed while complementing each other in activating the biopolitical discourse of “the defense of the society by itself” (Foucault, 1997). In this light, the images we have analyzed, and the “replacement thesis” they articulate, pursue a logic of eugenics, as a deliberate proposal to intervene in the racial constitution of a population. This proposal consists of mobilizing the wombs of white women—a part of the proposal that is put to the plebiscite—as well as fueling deadly fantasies of non‐white wombs turning into bombs and tombs. Taken together, the images articulate the two sides of eugenics, positive and negative policies, the former granting life, the latter letting die. In other words, the images call for the deployment of biopower and the discourse on defending the (European) society from its internal enemies, that is, Muslims.

Moreover, both images and their supplementary ideas about life and death activate and deploy biopower. However, as Schuller (2018) has pointed out, biopolitics not only operate through a caesura in the population performed by race, determining those who may live and those who may die, but equally through a sex differentiation superimposed in this first caesura that distinguishes within those who may live, between female and male sensibilities and impressibilities. While the AfD and Devareaux's vision introduce a racial categorization and division between Westerns/Europeans/Germans and Muslims, their biopolitical future, and the defense of the Western/European/German societies also necessitates a sex differentiation within the former, for it requires the control, and regulation of the white female body to secure the reproduction of the white sociopolitical body. As Schuller puts it, “Sex difference represents one of the key mechanisms through which race fragments the biological into governable units” (Schuller, 2018, p. 65). In this sense, the biopolitical protection of the health of the population and the maintenance of its equilibrium requires both racial and sex differentiations “with distinct claims to life” (Schuller, 2018, p. 65).

5. THE BIOPOLITICS OF THE “MUSLIM QUESTION”

So, what is then the “Muslim Question?” If the “Muslim Question” can be seen and approached as the general problematization of Muslims as “Muslims,” a problematization which includes the characterization of Muslims as an alien body to the nation, then the “Muslim Question” is biopolitics. It is part, and indeed has become central, to the regulation, management, and control of (national) populations in Europe, and in the West at large. One of the significant features of the population replacement palimpsest is that it reiterates the discursive production of the population itself and at the same time it introduces a caesura within this continuum: it breaks down the population inhabiting Europe into Europeans and Muslims. The population replacement discourse crafts this artificial reality and frames it in a wider civilizational confrontation where Europe—allegedly weakened for many reasons but also because of its stagnant birth rates—needs to be defended, safeguarded from the double death that Muslims come to represent: the immediate death of terrorism; and the long‐term but large‐scale death brought forth by the combative strategy of higher birth rates. Equally important, the demographic threat within the contours of the “Muslim Question” has also been a way to characterize and construct Muslims as an alien body to Europe. Some strands of the population replacement discourse diagnoses problems within Europe's current demographic development in terms of an ageing population and not enough newborns to replace the labor force to keep Europe's economic competitiveness. Yet this demographic problem only exists in so far as Muslims are not considered and counted as Europeans, in so far as their newborns have not been seen and cannot be seen as part of Europe, in so far as they remain “alien” to the European nations.

The biopolitics of the “Muslim Question” unfolds through a particular discourse we have laid out in this article, that is, the discourse of replacement. This fantasy of replacement—an “alien body” that comes to settle, colonize, reproduce itself, and finally replace a white and Christian Europe—is entertained, animated, and conspired in a way that grounds a politics that understands itself as merely a “response” to a demographic threat, and presents itself as seeking to “halt” this alleged replacement, relying on various kinds of actions drenched in natalist and eugenic desires. In this respect, the “Muslim Question” represents a—paranoid and apocalyptic—reading of the postcolonial predicament from the mindset of the former colonizer. It is an interpretation in which the postcolonial is experienced and framed as a situation of loss and of threat, and in which forces are mobilized to “fight back” in many arenas, against the plot, against feminism, against civic notions of citizenship and even against the history of Europe by reversing the roles of the colonized and the colonizer.

Commenting on the shortcomings of Foucault's biopower, Lemke (2011) argues that the notion fell short since it neither included nor allowed the examination of modalities of power aimed at inculcating forms of self‐government and the government of others, while, following Lemke (2011), the production of the population as a political problem unlocked the grid of governmentality. Once the population became the object of government's consideration it also fell under the calculations about the best way to defend, govern, and improve it. In this article, we focused only on one dimension of the “Muslim Question,” its biopolitical aspect, while the construction of Muslims as an “alien body” has also been paired with forceful calls of assimilation and integration, which is where governmentality, as an analytical tool, comes in. But a call for integration requires a prior distinction, a biopolitical one. Analytically, then, the contemporary Muslim Question recruits and operates two technologies of power. On the one hand, it deploys biopower in its pursuit of crafting the Muslim population as a problematic “alien body,” while desiring eugenic techniques that would present solutions to the problem. On the other hand, it calls for a series of discourses, policies, and techniques to govern the “integration” of Muslims, that is, it deploys governmentality. Although at times, these two technologies may operate independently, by and large they overlap and complement each other in producing a social and political reality where Muslims are deemed an inherent and dangerous problem.

While our examination of the demographic replacement also lends itself to advance the argument that race, religion, gender, and sex are never merely descriptive categories, but rather should be understood as produced, and indeed co‐produced, in particular contexts, we opted to focus on tracing the formation and dissemination of the replacement discourse, to offer a reading of this discourse against the light of biopolitics and eugenics, and to situate the emergence of this discourse within the contours of Europe's “Muslim Question.”

Bracke S, Hernández Aguilar LM. “They love death as we love life”: The “Muslim Question” and the biopolitics of replacement. Br J Sociol. 2020;71:680–701. 10.1111/1468-4446.12742

NOTES

This work is part of the research programme EnGendering Europe's Muslim Question with project number 016.Vici.185.077, which is financed by the Dutch Research Council (NWO).

Our analysis of the contemporary problematization of Muslims is focused on Europe. This does not imply, however, that the problematization of Muslims and Islam is confined to Europe, as Executive Order 13,769 (the “Muslim ban”) in the US, the Citizenship Amendment Act in India, or the Xinjiang “re‐education camps” in China, to name but a few examples, testify to.

By framing our analysis as the “Muslim Question” our intention is not to discard the work done by the concept Islamophobia, for it has been of paramount relevance in shedding light on the different processes of discrimination and violence faced by Muslims or those deemed as such. Yet we find the analytical framework of the “Muslim Question” apt to address the plethora of interrelated discourses that indeed encompass racial formations but surpass it.

Gil Anidjar seeks to interrogate not the “Jewish” and “Muslim Question” per se, but rather the subject who keeps posing these questions: Europe and the process whereby this entity called Europe has pursued to construct its integrity and unity “through the institutionalization of Others as ‘problems’” (Anidjar, 2012, p. 40). In this context, Anidjar, moreover, deconstructs the tenuous and fragile distinction between a question and a problem by arguing that these questions reveal not only how questioning turns subjects into problems to be solved, but also how all of these questions hint toward approaching Europe itself as a Question and as a problem.

A small but vocal group of intellectuals has been decisive in developing the discourse on population replacement by providing the themes and overall frame of the discourse. The books these intellectuals have produced not only immediately became best‐sellers, but also established powerful frames of thought to understand both the West and the alleged threat that Islam represents. On the internet, as Yasemin Shooman (2012) has documented, an international and highly connected network of actors has been at the forefront of disseminating stereotypes and hatred against Muslims, including the discourse on population replacement. There seems to be a symbiotic relation between these two spheres, the public intellectuals and the internet, while the former delimits the structure and rules of the discourse, the latter fills in the details, magnifies the threats, and reaches wider audiences.

An English translation of The Camp of Saints was particular well received in the US (Blumenthal and Rieger, 2017). The cover of the first edition joined the title of the novel with the heading “a chilling novel about the end of the white world” (Blumenthal and Rieger, 2017). And ever since its publication, Raspail's novel has gained the admiration of prominent figures of the far right such as Marine Le Pen, who exhibits a copy of the book in her office (Valerio, 2013), and also Steve Banon—former chief strategist of the Trump administration—who on repeated occasions has used the title of the book to describe the so‐called refugee crisis of 2014–2015, “The whole thing in Europe is all about immigration… It's a global issue today—this kind of global Camp of the Saints” (Banon, quoted in Blumenthal, 2017).

Fallaci (2004, p. 138) reports that the term is not hers: “No, it is not mine this terrifying term Eurabia. It is not I who conceived this atrocious neologism which derives from the symbiosis of the words Europe and Arabia, Eurabia is the name of the little journal founded in 1975 by the official perpetrators of the plot, of the conspiracy: the Association France‐Pays Arabes in Paris.”

As Dyrendal et al. (2018, pp. 7–8) point out, conspiracy theories can be in, about, and as religion, in other words, the relation between conspiracy theories and religion is not straightforward, but often conspiracy theories join the dots between religion, politics, and terrorism and violence. Moreover, either secular or majority religious groups can recruit and mobilize conspiracies to demonize and cast out religious minorities, anti‐Semitism being a paradigmatic example.

Ye’Or consistently uses “alteration” or “substitution.” The term “replacement” does figure in her writings as in “replacement theory” in the realm of theology, where she constructs the argument that, while the Vatican has formally denounced supersessionism, Muslims consider Islam as a perfected final version of Abrahamic monotheism, thus superseding Jews and Christians.

Le Grand Remplacement, speech delivered on November 26, 2010, in Lunel, Dep. Hérault in France, published in Camus (2011) (Neuilly‐sur‐Seine: David Reinharc, 2011).

Camus calls this “the second career of Adolf Hitler,” by which he means a “less bloody but more lasting” effect that the term race has become a taboo (Camus, 2011, p. 67, authors’ translation). Many critical race scholars have documented how, after the Shoah, “race,” as an analytical category, has become the unspeakable in Europe in general, and, for different reasons, in Germany and France in particular (see, e.g., Lentin, 2008). As race became unspeakable, it could be argued, it went “underground” and provided fertile ground for a new substantive racial and racist thinking, of which Camus is a prominent example, which is now finding its way into mainstream public debate again.

The full video of Boumédiène's speech [in Arabic] can be retrieved from the United Nations’ archive: (UN General Assembly, 1974a). An English translation of the 2,208th Plenary meeting can be found in UN General Assembly (1974b).

The use of memes understood as “small cultural units of transmission … spread by copying or imitation” (Shifman 2011, p. 188) has been crucial in the proliferation and dissemination of the population replacement conspiracy in the internet. Geert Lovink and Marc Tuters (2018) argue that memes can be seen “as a kind of vernacular cultural compression technique, a means by to ‘decode’ and ‘encode’ the operative dynamics of dominant hegemony.” The fabricated quote of Boumédiène along with his portrait has been composed into a meme able to travel and be understood easily and swiftly. The meme comprises the core idea of the replacement thesis and offers itself to be consumed in an instant.