Medical-legal partnerships (MLPs) have been established in 292 healthcare and 142 legal aid organizations in 36 states in the U.S. They comprise a healthcare delivery model that integrates legal assistance as a vital component of healthcare.1 MLPs are built on three key beliefs: (1) the social, economic, and political context in which people live has a fundamental impact on health; (2) social determinants of health often manifest in the form of legal needs; and (3) attorneys have the special tools and skills to address these needs. MLPs bring legal and healthcare teams together to provide high-quality, comprehensive care and services to patients who need it most. According to the National Center for Medical-Legal Partnership, the most promising MLPs are those in which healthcare and legal professionals use training, screening and health and legal care to improve patient and population health; and in which this legal care is integrated into the delivery of healthcare and has deeply engaged health and legal partners at both the front-line and administrative levels to improve patient health.2

Health disparities continue to increase among those most vulnerable, and gaps should be addressed at all levels of well-being. Four in five physicians say patients’ social needs are as important to address as their medical conditions, according to a recent survey conducted by Harris Interactive on behalf of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Among physicians serving patients in low-income communities, nine in ten believe this is true. Eighty-five percent of primary care providers and pediatricians reported that unmet social and legal needs — things like access to nutritious food, reliable transportation, and adequate housing — lead directly to worse health for all Americans. Yet in spite of their insistence on the capacity of social and legal needs to affect patient wellbeing, approximately 80% of physicians surveyed did not feel confident in their capacity to address such needs, and further indicated that this gap impeded their ability to provide quality care.3 Social needs perpetuate health disparities and must be tackled in order to reduce overall morbidity and mortality.

In particular, disparities in HIV/AIDS continue to rise in the U.S. and globally.4 Despite substantial improvements in the prevention of HIV/AIDS in the United States, some populations continue to be disproportionately affected by these diseases. For example, although Black Americans represent only 12% of the U.S. population, they accounted for 44% of new HIV infections and an estimated 44% of people living with HIV in 2010. Blacks also accounted for almost half of new AIDS diagnoses (49%) in 2011. In 2010, male-to-male sexual contact accounted for half (51%) of new HIV infections among blacks overall and a majority (72%) of new infections among black men.5 A similar trend holds true for Latinos. Latinos represented approximately 16% of the U.S. population but accounted for 21% of new HIV infections and 19% of people living with HIV in 2010. Latinos also accounted for 21% of new AIDS diagnoses in 2011. Among Latinos, men who have sex with men are heavily impacted by HIV. In 2010, male-to-male sexual contact accounted for nearly 7 in 10 (68%) new HIV infections among Latinos overall and nearly 8 in 10 (79%) new infections among Latino men.6 These disparities in HIV/AIDS are attributed to many concurrent factors, including lack of HIV testing and access to prevention and care, poor mental health, substance use, violence and victimization, discrimination, and economic hardship.

Stigma and discrimination continue to surround the HIV epidemic. People living with HIV still face potential discrimination in health care, housing, employment, parenting, insurance, and other aspects of life.7 For instance, those living with HIV may encounter prejudice when attempting to rent an apartment due to misinformed beliefs about the communicability of HIV, and they may also be unable to meet minimum income qualifications for stable housing if their chronic illness limits or fully negates their capacity to work.8 In a recent study of those living with HIV/AIDS in Los Angeles County, that 98% of respondents reported having a legal need within the last year, with needs ranging from health care access to public benefits.9 Thirty-one percent of these study participants reported experiencing HIV-based discrimination in employment, housing and health care settings. When coupled with the medical complications associated with HIV/AIDS, these social issues may have a pernicious impact upon the health and wellbeing of HIV-affected populations. MLPs are uniquely positioned to combat these medical and legal issues comprehensively.

While there has been a substantial increase in scholarly literature on MLPs in recent years,10 including an entire issue in the Journal of Legal Medicine devoted to the subject in 2014,11 few studies have documented their effects on health disparities in vulnerable populations. We aimed to collect and synthesize contemporary scholarly knowledge regarding the impact of MLPs on patient welfare and community health disparities. In doing so, we did not attempt to produce a comprehensive overview of the structure, services and impact of the several hundred MLPs operating within the U.S., but rather to systematically review empirical evaluations of such programs. We further aimed to develop new directions regarding the potential for MLPs to address the needs of HIV-affected populations.

Methods

We conducted our review in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.12 This approach directs researchers to conduct a broad initial search for potentially relevant material, and then to narrow the results in several subsequent stages based on specific and replicable inclusion criteria.

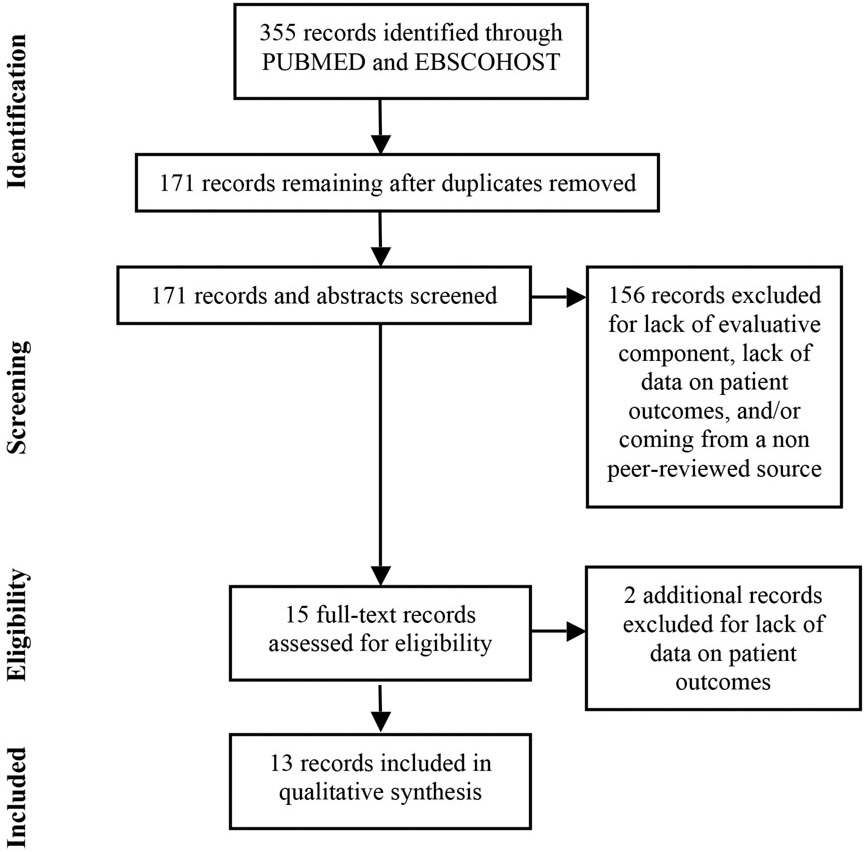

We searched the PUBMED and EBSCOHOST databases for articles published between January 1993 and January 2016 that included critical terms related to the review (step one, see Table 1). This yielded 355 publications, including 34 from PUBMED and 321 from EBSCOHOST. We then removed all duplicates within and across databases, which reduced our sample to 171 articles (step two). We screened the titles and abstracts of all 171 pieces, based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) works appeared in peer-reviewed sources,13 had an evaluative component, (3) emphasized patient inputs and/or outcomes, and (4) provided empirical data for a sample of patients who were screened for and/or received services through MLPs (step three). The first criterion limited our review to scholarly works, and eliminated such non-scholarly items as newspaper articles and press releases. The second criterion excluded a range of works from consideration including book reviews, letters to the editor, and policy pieces that advocated the development or modification of MLPs without providing empirical data regarding their implementation or impact. The third criterion related to our interest in the capacity of MLPs to reduce health disparities through addressing patients’ otherwise unmet legal needs. Articles that focused entirely on medical and/or legal education, potential financial benefits (or drains) for hospitals and clinics, and/or legal and healthcare providers’ perceptions of medical-legal collaborations were excluded. The fourth and final criterion excluded limited case studies from consideration, and restricted our review to evaluations with data for multiple patients. In addition to limiting our review to studies with more rigorous evaluative designs, this final criterion further prevented hand-selected “success stories” or “failure stories” from biasing our analysis.

Table 1.

Core Database Search Strategy: Peer-reviewed, January 1993 - January 2016

| Focus | Search Terms |

|---|---|

| (1) Medical Legal Partnership | (“medical Legal Partnerships”[Mesh] OR “MLP”[Mesh] OR “randomized clincial trials”[Mesh] OR medical legal partnership [tiab] OR MLPs [tiab] OR health legal partnership [tiab] OR health partnerships [tiab] OR health law programs [tiab]) |

| AND | |

| (2) Health Disparities | (“health disparities” [mesh] OR “health services” [mesh] OR “gaps in health disparities” [mesh] OR “public health impact” [mesh] OR “disease prevention” [mesh] OR Health disparities [tiab]) |

| AND | |

| (3) Evaluation of some kind | (study[tiab] OR studies[tiab])) OR (intervention*[tiab] AND (study[tiab] OR studies[tiab] OR program*[tiab] OR pilot[tiab]) OR evaluation*[tiab]) |

| AND | |

| (4) Intervention studies | (Randomized clincal trial[tiab] OR RCT [tiab] OR intervention[tiab] OR design [tiab] OR control experiment [tiab] OR case-control designs [tiab] OR multivariate regression [tiab]) |

Results

Applying the PRISMA criteria, we identified 15 pieces for full-text review. Additional screening resulted in an exclusion of 2 more pieces based on those same criteria, for a final pool of 13 articles. See Figure 1 for a visual representation of this process, also referred to as the “PRISMA Flow of Information” chart. The final 13 articles were subjected to intensive qualitative analysis, based on the overarching concerns of the systematic review: (a) assessing the potential for MLPs to reduce health disparities in vulnerable populations, and (b) speculating and/or identifying empirical data regarding the potential for MLPs to specifically address the needs of HIV-affected populations (Table 2).

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram of Search and Data Extraction

Table 2.

Studies Examining the Impact of MLPs in Addressing Health Disparities, 1993–2015

| Authors | Year | Title | Journal | Location | Sample Size | Target Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beck, et al. | 2012 | Identifying and treating a substandard housing cluster using a medical-legal partnership. | Pediatrics | Cincinnati, OH | 16 units, housing 45 children | Families with children, specifically those living in substandard housing conditions |

| Fleishman, et al. | 2006 | The attorney as the newest member of the cancer treatment team. | Journal Of Clinical Oncology | New York, NY | 3 patients | Cancer patients |

| Klein, et al. | 2013 | Doctors and lawyers collaborating to help children: Outcomes from a successful partnership between professions. | Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved | Cincinnati,OH | 28,200 patients across 3 clinics:1,614 referred to MLP | Families with children |

| O’Sullivan, et al. | 2012 | Environmental improvements brought by the legal interventions in the homes of poorly controlled inner-city adult asthmatic patients: a proof-of-concept study. | The Journal Of Asthma | New York,NY | 12 patients | Adults with asthma |

| Pettignano, et al. | 2011 | Medical-legal partnership: impact on patients with sickle cell disease. | Pediatrics | Atlanta, GA | 71 parents/guardians of 76 children withsickle cell disease | Families with children diagnosed with sickle cell disease |

| Pettignano, et al. | 2013 | Can access to a medical-legal partnership benefit patients with asthma who live in an urban community? | Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved | Atlanta, GA | 295 parents/guardians of 313 children with asthma | Families with children diagnosed with asthma |

| Rodabaugh, et al. | 2010 | A medical-legal partnership as a component of a palliative care model. | Journal of Palliative Medicine | Buffalo, NY | 297 patients in main assessment: 2 case studies | Cancer patients |

| Ryan, et al. | 2012 | Pilot study of impact of medical-legal partnership services on patients’ perceived stress and wellbeing. | Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved | Tucson, AZ | 67 patients | Adult patients and adult parents of minor patients |

| Sandel, et al. | 2014 | The MLP vital sign:Assessing and managing legal needs in the healthcare setting. | The Journal of Legal Medicine | Boston, MA | Need assessment:154 stage 1; 39 stage 2; Case study: 1 | Families with children |

| Sege, et al. | 2015 | Medical-legal strategies to improve infant health care:A randomized trial. | Pediatrics | Boston, MA | 330 families: 163 control and 167 intervention | Families with newborn children |

| Taylor, et al. | 2015 | Keeping the heat on for children's health:A successful medical-legal partnership initiative to prevent utility shutoffs in vulnerable children. | Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved | Philadelphia,PA | Year 1:450 utility medical certification requests.Year 2:846 requests. | Families with children |

| Teufel, et al. | 2012 | Rural medical-legal partnership and advocacy:A three-year follow-up study. | Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved | Southern IL | 825 patients | Adult patients |

| Weintraub, et al. | 2010 | Pilot study of medical-legal partnership to address social and legal needs of patients. | Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved | Palo Alto,CA | 54 families | Families with children |

Overall Utilization of MLPs

Consistent with literature regarding the value of flexibility in developing MLPs,14 the 13 studies in this review described a range of MLP teams and organiza tional practices. Some MLPs were limited to attorneys and primary care staff such as physicians and nurses, whereas others relied heavily on additional providers such as social workers to screen and support patients/clients. Some MLPs made use of waiting rooms for initial screenings, and directed medical and/or social work staff to administer social needs assessments while patients awaited their appointments, whereas others incorporated legal and other social determinants of health (SDH) assessments into standardized medical histories. MLPs further varied in the extent to which hospitals and clinics partnered with external organizations, such as legal advocacy agencies, in addressing patients’ legal needs.

Researchers in the 13 studies used a range of methods for assessing the impact of MLPs. Several studies simply provided overviews of MLP practice over a period of one or more years, incorporating such data as the number of patients referred to MLPs or otherwise identified as in need of services, the number and nature of cases opened (i.e. which specific needs were identified, such as housing or utility bills), financial benefits secured for patients and clinics, and the percentage of successful interventions (i.e., those that resulted in improved access to benefits, or the resolution of a legal problem).15 One study focused on pre-intervention data as a means of establishing the scope of legal needs among clinic patients, and supplemented these data with a single in-depth case study of a patient whose use of emergency medical services declined notably after receiving MLP services.16 Another provided three case studies for patient utilization of MLP services.17 Only four of the 13 studies provided more rigorous investigations that incorporated pre-test and post-test data for a sample of patients who received services.18 Finally, given that the first MLP launched in 1993, we note that the oldest article in our review was published in 2006,19 and that the first study with a comparatively rigorous, pre- and post-test design for assessing patient outcomes was published in 2010.20 Efforts to promote and implement MLP models in legal and healthcare settings appear to have considerably outpaced efforts to evaluate such models.

Establishing the Need for Legal Interventions

For more than 20 years, clinics and hospitals in the United States have founded and expanded MLPs based on the following assumptions: (a) patient populations, particularly but not limited to low-income families with children, often have unmet legal needs; and (b) addressing these legal needs will have a positive impact on patient health. These assumptions are hierarchical. If the first is inaccurate, the second is somewhat irrelevant, or at least too minimal to necessitate a clinic-wide change in protocols and the development of a permanent MLP. Bearing this hierarchy in mind, many of the pieces included in this review provided data to establish the range and scope of legal needs in patient populations.

One study at the Boston Medical Center focused entirely on legal needs assessment.21 Hospital staff administered a brief legal needs assessment to all parents and guardians of patients at the pediatric emergency department in Fall 2007 (n=154), and conducted a series of in-depth follow-up interviews (n=39). These assessments revealed substantial legal needs among patients. Almost half of families reported receiving at least one letter threatening utility shutoff within the previous year, and 23% of those families had actually experienced a shutoff. One quarter of families reported using less safe energy alternatives such as heating the home with a stove, and more than one-third reported reducing meal sizes or skipping meals altogether due to inadequate resources. While 85% of families with legal needs reported these issues as “serious” or “very serious,” few had sought out legal services. Some families were unsure of whom to contact, concerned that legal services would be costly or unhelpful, and/or unaware that their concerns could be addressed through legal means.

| Methodology | Main Findings |

|---|---|

| Families screened for substandard housing during outpatient primary care, MLP referrals made as appropriate. Researchers presented the outcomes of MLP intervention. | Sixteen families screened for substandard housing;outcome data available for 14. Pest infestation and water damage were the most common issues. After MLP intervention, major repairs were completed in at least 10 homes. |

| Presentation of three in-depth case studies for patients who received MLP services. | Patients received effective interventions in regards to end-of-life,financial, and workplace related issues. |

| Review of patients' records, specifically in regards to patients screened for MLP referral and the legal outcomes of MLP interventions when applicable. | Relative to the full sample, patients referred to MLP were significantly more likely to be African American, have public insurance, and be diagnosed with asthma, developmental delays, and/or behavioral disorders. Housing and income/health benefits were the most common bases for MLP referrals. Referrals for the 1614 patients/families resulted in 1945 legal outcomes - 89% (1742) outcomes were positive, such as improvement in housing or the provision of relevant legal advice).Across all cases, MLP secured approximately $200,000 in back benefit recovery. |

| Retroactive review of patients' medical records, 9-12 months pre-intervention and 6-12 months postintervention, specifically in regards to the impact of MLP intervention on asthma severity and related utilization of health services. | Following MLP intervention, there were declines in emergency department visits, hospital admissions, overall need for systemic steroids, medication doseage, and asthma severity.. |

| Retroactive review of patients' records, specifically in regards to legal outcomes.H 1 3 | The 71 parents/guardians presented with 106 legal issues, 51 of which related directly to children. MLP intervention closed 99 of them, with 21 resulting in a quantificable increase in benefits. |

| Retroactive review of patients' records, specifically in regards to the impact of MLP intervention on financial and other benefits. | MLP screenings resulted in 250 legal interventions; housing, family law, disability, education, and Medicaid were the most common issues. Sixty-five cases had financially measurable outcomes, resulting in an estimated total of $500,000 in annual benefits. |

| Retroactive review of patients' records, specifically in regards to the legal and financial outcomes of MLP intervention. | The most common issues identified for MLP intervention were custody/guardianship, advance care planning, benefits, estate planning, housing, and legal advice. Case Study 1 concerned securing access to HEAP and food stamps for a patient whose benefits were cut after he began staying in a hospitality room between treatments; Case Study 2 concerned preventing eviction and arranging for within-family guardianship after a patient's death. |

| MLP staff administered pre- and post-intervention assessments of patients' self-perceived stress and overall wellbeing. | After MLP interventions, patients reported significant declines in stress and increases in personal wellbeing. |

| BMC staff administered a legal needs assessment in 2 stages: (1) self-administered quesionnaire, given to parents/guardients of patients at Pediatric Emergency Dept; (2) follow-up telephone interviews. Researchers also presented one in-depth case study from Lancaster, PA. | BMC Study identified substantial legal needs among participants. Utility shutoffs/threats of shutoff and food insecurity were among the most common.While 85% of families with unmet legal needs described these issues as serious or very serious, most had not sought legal services. Case studyconcernd a patient whose utilization of emergency services declined considerably after MLP intervention. |

| Intervention group families were assigned a Family Specialist who provided ongoing support up to the 6-mth routine visit; control group families received infant safety intervention. Researchers administered surveys at baseline, 6mths, and 12mths, and reviewed patients' medical records. | At baseline, the majority of participants reported at least one or two hardships in the previous year; food and housing security were the most common issues. Family Specialists initiated MLP consults for 75 families. Intervention group had significantly greater success accessing concrete supports, including utility and food assistance. Intervention group children were significantly more likely to be on schedule with immunizations and care visits at 6mths, those there were no such differences at 12mths. |

| Researchers documented patients' pursuits of Certifications of Medical Need (COMN) for utility assistance, along with approval rates, for one year prior to and one year following the implementation of an MLP | After MLP implementation, the number of COMN requests increased by 47% and the approval rate increased by 67%. |

| Longitudinal review of patient records, ultimately spanning 7 years, specifically in regards to legal and financial outcomes. | MLP screenings resulted in 1,152 referrals for 825 patients; 259 of these resulted in successful trial/mediation. An additional 450 cases were resolved through legal advice or referrals.Altogether, MLP interventions relieved almost $4,000,000 in patients' health care debt. |

| MLP staff administered pre- and post-intervention assessments of families' legal needs and parents' reports of child wellbeing. | After MLP interventions, families reported significant improvements in access to benefits, and significant declines in avoidance of healthcare due to financial concerns.Two-thirds of participants reported improvements in child wellbeing. |

Several studies provided data regarding the number of patients who were screened for unmet legal needs as a means of establishing the need for MLP interventions. Within its first three years, the Child HeLP program in Cincinnati, OH identified 1,614 patients with unmet legal needs from a broader pool of 28,200 patients.22 Housing and public benefits-related needs were the most common. Focusing specifically on families with children who were diagnosed with asthma, an assessment of the HeLP program in Atlanta, GA identified 250 issues appropriate for MLP intervention from a sample of 295 parents and guardians.23 The most frequent issues concerned housing, family law, disability, education, and Medicaid (in that order). An MLP in Buffalo, NY that focused on the needs of patients in palliative care received 297 referrals between April 2004 and December 2007.24.The most common legal needs in this population concerned child custody and guardianship, advance care planning, benefits, and housing and estate planning. Taken together, these studies established the overall scope of unmet legal needs among hospital and clinic patients, as well as the necessity of tailoring MLPs to specific target populations.

The Impact(s) of Medical-Legal Partnerships

Policy papers and other works advocating the inclusion of attorneys in healthcare teams outnumber rigorous, empirical evaluations of such teams. This is particularly striking, given that support for and utilization of MLPs appears to be increasing nationwide. It is therefore increasingly important to conduct and disseminate rigorous, replicable evaluations of this model. Furthermore, when evaluations have been conducted, they have often emphasized interventions in patients’ unmet legal needs, specifically those recognized as social determinants of health (e.g., the presence of mold and pest infestations), over and above such interventions’ ultimate effects on patient health and utilization of medical services. In other words, researchers have established more findings regarding the capacity of MLPs to address legal outcomes than their capacity to address health outcomes.

The aforementioned assessment of Child HeLP determined that referrals for 1,614 families resulted in the identification of 1,945 legal outcomes.25 Almost 90% of these (1,742) were positive, as evidenced by such developments as improvements in housing or benefits, or the provision of useful legal advice. MLP interventions from the referrals secured approximately $200,000 total in back benefit recovery. Another assessment of Child HeLP focused on MLP capacity to identify and address environmental problems in substandard housing clusters (e.g. units with pest infestation, mold, or uncompleted repairs that posed health risks). Out of a sample of 16 units housing a total of 45 children, repairs were documented in 10 units.26 The aforementioned assessment of HeLP included 65 cases with financially quantifiable outcomes within a broader pool of 250 legal interventions; these totaled more than $500,000 in estimated annual benefits to patients.27 Another assessment of HeLP, this time focusing on families with children who were diagnosed with sickle cell disease, identified 106 legal issues from an initial sample of 71 parents and guardians. MLP interventions closed 99 of these cases, with 21 resulting in a measurable improvement in benefits.28 An assessment of a rural MLP in Southern Illinois found that 825 patients had received services over a 7-year period, resulting in 259 successful outcomes in court or mediation, the provision of legal advice and referrals for 450 additional cases, and the relief of nearly $4,000,000 total in patients’ health care debt.29 An MLP in Philadelphia, PA produced significant improvements in approval ratings for certifications of medical need (COMN), which enabled patients to attain assistance with utility coverage.30

Four studies directly addressed the impact of MLP interventions on patient health, incorporating pre-and post-assessments. The most rigorous among them was a randomized control trial for Project DULCE in Boston, MA, a comprehensive program which aims to improve care access and utilization for families with infants.31 Three hundred and thirty families participated, including 163 assigned to the control group and 167 to the intervention group. The former participated in infant safety training; the latter were assigned a Family Specialist who provided ongoing support for the first 6 months of a newborn’s life, including but not limited to MLP referrals. At 6 months after infants’ birth, intervention group families (i.e., those with access to MLP services) were significantly more likely to be up-to-date on immunizations and care visits, and to have used emergency services less frequently; however, these effects disappeared at 12 months. It was also not possible to isolate the impact of MLP services in particular, relative to the other components or cumulative impact of Project DULCE.

One retroactive assessment of 12 asthmatic adults in New York City, which compared patient data 9-12 months prior to and 6-12 months following MLP intervention, documented declines in emergency department visits, hospital admissions, patient need for systemic steroids, and clinical asthma severity.32 A pilot study of an MLP in Palo Alto, CA with 54 families found significant improvements in parents’ assessments of children’s overall health and wellbeing, and a decrease in healthcare avoidance due to concerns regarding health insurance and costs.33 An assessment in Tucson, AZ with 67 participants found that patients reported decreased stress and improved personal wellbeing after MLP interventions.34

Geographic Location and Target Population

Broadly speaking, MLPs target low-income populations. As is often the case with legal advocacy services, interventions were typically available for families with incomes below 200% of the federal poverty line. Many of the hospitals and clinics that established MLPs were located in low-income areas to begin with, and served financially disadvantaged populations. Patients who screened for unmet legal needs, but whose incomes were above program thresholds, were referred to external resources.

Beyond this emphasis on low socioeconomic status, many MLPs (and assessments of MLPs) focused specifically on families with children.35 Only one study focused explicitly on adults;36 an additional two seemed primarily geared towards adult populations.37

Furthermore, all 13 studies were conducted in the United States, and 12 of them focused on MLPs located in major urban centers such as Atlanta and Boston; only one38 assessed the implementation and impact of MLP services in rural communities. The paucity of programs and evaluations in low- and middle income countries, and in rural communities within the U.S., likely reflects the infrastructure and economic disadvantage of resource-poor communities.

While the articles included in this study addressed a small range of specific medical conditions, including asthma and cancer, there were no assessments of the capacity of MLPs to address the needs of people living with HIV or facing a high risk of HIV acquisition.

Theoretical Foundations

None of the articles included in this review provided a guiding theoretical framework concerning the development, implementation, or evaluation of MLPs. A previous publication on Project DULCE in Boston, MA drew on a risk and protective framework, which compels providers to consider patients’ strengths and other resources in addition to the factors that threaten their wellbeing39; however, this framework was lacking in the empirical assessment of DULCE’s impact on utilization of infant healthcare services.40

Discussion

Drawing from Inclusive Practices to Better Serve Vulnerable Populations

Significant strides have been made to demonstrate the impact and efficacy of medical-legal partnerships. Gaps exist, in particular when establishing key mediators impacting health outcomes, but studies show improvement and success in key MLP domains in addressing a range of health and (more frequently) legal needs. Our results bring together critically appraised articles highlighting the improvements in the health and wellbeing of vulnerable patients as result of MLP interventions. Table 3 provides an overview of key constructs and elements identified by the authors to further improve MLPs.

Table 3.

Common Elements and Comprehensive Constructs in MLP Programs with Rigorous or Strong Evidence

| Target Population |

| 1) Clearly defined the targeted population, including age and georgraphic location; 2) outlined stategies for recruitment and engagement; 3) tailored MLP screenings and service provision to the needs of the target population. |

| Needs Assessment |

| 1) A population-relevant needs assessmented was conducted in regards to unment legal needs that negatively affect patient health and access to care (e.g. concrete supports such as income supports, food stamps, disability benefits, utility assistance, health insurance; and legal status issues such as criminal background, consumer law status, military discharge status, immigration status). |

| Theoretically Grounded |

| 1) Need for theoretically grounded models or theories driving MLP evaluation. Creating a codebook and a well-defined, precise documentation protocol to capture staff and patients decisions, as well as any reported outcomes, could help inform future studies and ensure replicability. |

| Integration of Services |

| 1) Routine incorporation of legal needs screening into health care protocols (e.g. in waiting rooms or during scheduled appointments); 2) fully intregrated MLP where prioritized legal needs were connected to patient health; 3) incorporation of legal team, including attorneys, into broader hospital or clinic health care team shaped the organization and its functioning, ultimately impacting public health infrastructure; 4) presence of a framework of shared understanding concerning patient confidentiality issues, compliance with HIPAA, proper identification of the client, safeguarding the attorney-client privilege, and other legal and ethical issues that arise in medical-legal collaborations. |

| Capacity to carry out MLP |

| 1) Successful MLPs included and engaged and incorporated in their implementation/sustainability approach a wide range of stakeholders, from physicians, lawyers, and social workers to the members of the community intended to reach; 2) clear definition of roles and responsibilities for each stakeholder. |

Our review also identified a need to consider the capacity of MLPs to address health disparities across a broader range of populations. Data on the perspectives of patients with diverse health conditions and related variation with regard to type of legal needs or unique interrelated legal and health challenges are limited. The articles reviewed here demonstrate the value of tailoring interventions towards specific populations, as indicated by the extent to which the legal needs of cancer patients41 differed from those of families with asthmatic children.15 However, much remains be done in regards to identifying the most prevalent legal needs, and designing appropriate MLP interventions for, a broader range of patient-client populations. It is also imperative to further investigate the contexts of and approaches to recruitment and retention of minority populations in MLPs. Not a single study in this review considered race, ethnicity or sexuality as mediating factors impacting health outcomes. The incorporation of community-based participatory research approaches, including involvement of community stakeholders in the development and implementation of MLPs, may hold particular promise. Finally, researchers may be able to use the findings of this study to inform and motivate future large-scale, prospective longitudinal studies to assess the efficacy of MLPs as a strategy for addressing health-threatening legal needs across different groups.

Making the Case for Theory-Grounded MLPs

Theoretically grounded research illuminating the mechanisms of legal issues on health outcomes would provide a much needed contribution to MLP design, implementation, and evaluation. The choice of what theory or theories to draw upon in the practical implementation of programs or in the design of questions is critical for the future of MLPs. The theory of triadic influences suggests that behavioral intentions and, ultimately, actual behaviors are influenced by a complex set of intrapersonal, interpersonal, and sociocultural/environmental factors.43 As applied to MLPs, this approach would direct program designers and staff to consider patient-clients’ individual perspectives and experiences, social support networks, and institutional influences in attempting to address unmet health and legal concerns. The theory of planned behavior (TPB)44 could also potentially be used to test or evaluate the impact of MLPs. TPB explains how laws, policies, or programs can result in behavior change and improvements in health outcomes. As indicated above, a risk and protective framework has already been used to design a comprehensive intervention that included MLP services. This might be of value for other MLPs, in that program staff might assess the extent to which patients’ social supports and other resources can mitigate environmental threats to health and promote patient utilization of legal and healthcare services. Most MLP protocols analyzed for this review focused on risks to patient wellbeing without considering or engaging protective factors.

Causal diagrams (CDs) could also potentially impact the implementation and evaluation of MLPs. Novak defines causal diagrams as graphical tools for organizing and representing knowledge.45 The concepts represented in CDs are variables, characteristics or quantities with changeable values, which may be either observed (or are observable in principle) or theoretically postulated. While CDs do not necessarily represent a theoretical paradigm in and of themselves, they may provide a means of translating theoretical foundations into program design. Theoretical assumptions might provide a foundation of initial concepts that shape patient-client needs and behavior, as well as a logical framework for developing implementation and evaluation strategies.

Building Models Grounded in Measures and Designs

The findings from this review point to the urgent need to test the efficacy of MLPs through rigorous designs. Developing adequate scales and instruments to measure impact of MLPs remains particularly difficult. Creating simple scales based on the number of individuals reached and/or the number of legal needs addressed, or treating all MLP interventions as equivalent, may be misleading because of the substantial variation across MLPs in regards to services, resources, and target population, as well as variation among patient-clients served within and among MLPs. Important to note is that no studies have been conducted to assess which aspects/components of the MLP are more impactful to patients. Scales and instruments should be shaped by underlying theoretical frameworks. More importantly, we recognize that alternatives to randomized controlled trials are necessary to fully understand the impact of MLP while taking into consideration the real-life conditions in low-income and otherwise marginalized communities. Several of the pieces reviewed here provided data for legal needs assessments.45 It would have been unethical to randomly assign some patients with unmet legal needs to an MLP intervention group, while declining to provide support for the rest. Alternatively, a stepped-wedge randomized trial design might provide a suitable mechanism to explore and evaluate the efficacy of MLPs.46 Rather than randomly assigning some participants to receive an intervention and assigning others to a non-intervention control group, stepped wedge designs ensure that all participants receive an intervention, but randomize the order in which they do so. The design is particularly relevant where it is predicted that the intervention will do more good than harm and/or that non-intervention would amount to doing harm, as in the case of MLPs; under such circumstances, it is considered unethical to utilize a parallel design in which only some participants receive an intervention. Stepped wedge approaches are also appropriate when, for logistical, practical or financial reasons, it is impossible to deliver the intervention to all participants at once; this may well be the case for large-scale evaluations, in which researchers and providers seek to evaluate MLP interventions with a larger patient-client population than a given program can provide for simultaneously.

Applying and Integrating Bioethics for the Enrichment MLPs

Other areas of MLPs should be further analyzed, including the unique, interrelated, and often similar ethical issues that confront the clinical and legal partners involved in the implementation and evaluations MLPs.47 For instance, a lawyer in an MLP setting must be attuned to the traditional rules governing conflicts of interest, making sure that present client matters do not conflict with the lawyer’s other existing client matters, a lawyer’s responsibilities to a third party, or the same or substantially related matters in which the lawyer represented previous clients.48 Moreover, the medical and legal service providers should have a framework of shared understanding concerning patient confidentiality issues, compliance with HIPAA, proper identification of the client, safeguarding attorney-client privilege, and other legal and ethical issues that arise in medical-legal collaborations.49 MLP collaborators must be mindful of these issues of shared responsibility when structuring an MLP’s operations. Indeed, designing and implementing a data collection and retention system to measure an MLP’s health and legal interventions and outcomes in ethically appropriate ways is another avenue ripe for exploration.

Bridging Health Disparities in HIV/AIDS through the Use of Medical Legal Partnerships

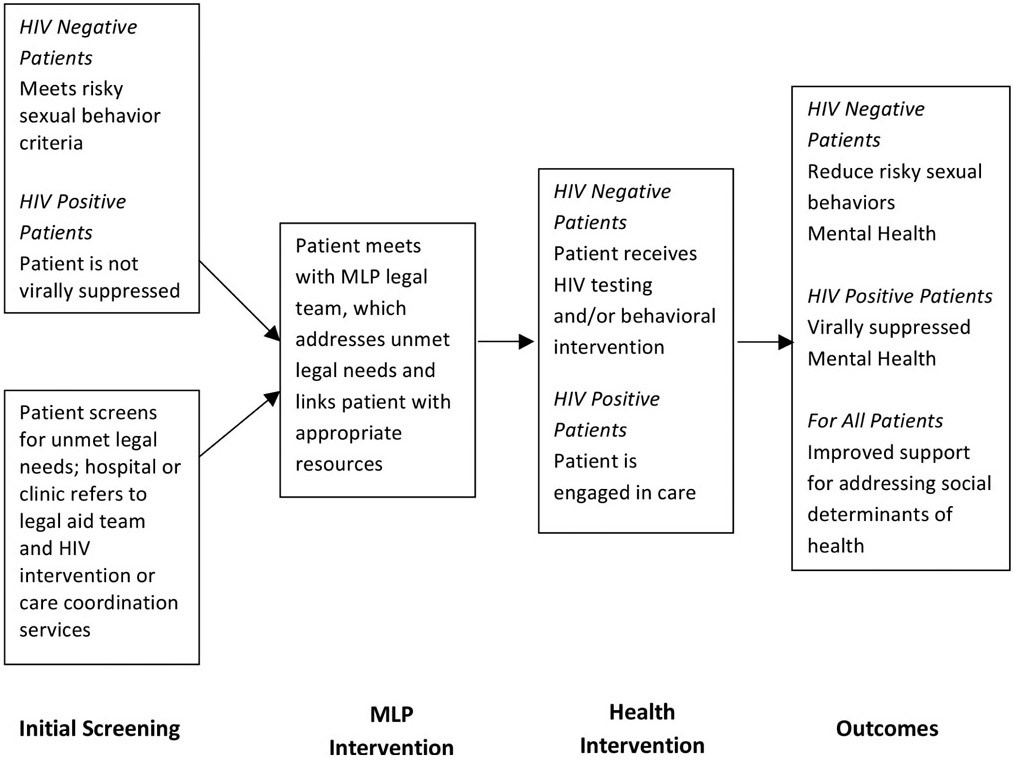

Building on theory and inclusive measures, an HIV/AIDS MLP model could serve as a framework to address HIV-related legal and health disparities. MLPs offer an integrated approach to healthcare delivery that seems promising for meeting the needs of individuals at high-risk of HIV acquisition and people living with HIV, but has yet to be rigorously assessed within this population. HIV/AIDS disparities are attributed to syndemic factors, including lack of testing and access to care, discrimination, poor mental health, substance use, violence, and economic hardship.50 MLPs offer a structural integrated intervention that could tackle these factors and facilitate improvements in medical and psychosocial outcomes among high-risk groups and HIV-positive individuals. A causal diagram was built to demonstrate how an HIV/AIDS MLP model can address disparities in HIV/AIDS (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

MLP to Address Health Disparities in HIV/AIDS

Limitations

First, although we used a thorough search strategy, we were invariably constrained by search terms and our specific emphasis on evaluations of MLPs; therefore, we may have inadvertently missed some relevant work on MLP programs. Second, our search was limited to two languages and two major databases. We did not look at reports or studies published at web sites of major international organizations or policy centers. It is possible that MLP program descriptions and evaluations may be available in other languages or on other Web sites. The decision to exclude reports or studies published at web sites or gray literature such as conference proceedings or institutional publications resulted from our strict inclusion criteria to include only peer-reviewed articles.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, our study was the first comprehensive systematic literature review on the impact of MLPs in addressing health disparities and improving health outcomes. Our results speak to the potential for MLPs to address health and legal needs, while highlighting the need for more rigorous investigations (including longitudinal assessments) to better capture the efficacy and impact of MLPs. Our review of the literature also points to the need to refine MLP approaches for a broader range of vulnerable populations and communities at need, including individuals at high risk of HIV acquisition and HIV positive individuals. A great deal of work related to rigorous and theory-driven evaluations, designs, challenges in addressing the legal and health needs of diverse populations, and ethical complexities in the implementation of MLPs remains to be done. MLPs represent an innovative approach that could potentially close numerous gaps in health disparities; theory-grounded program designs and rigorous evaluations should go a long way towards realizing this potential.

Acknowledgments

We thank Scott Buris, J.D., professor at Temple University Law School and Ronda B. Goldfein, J.D., executive director at AIDS Law Project of Pennsylvania, for their continuous support during the review process and for providing valuable input.

Contributor Information

Omar Martinez, School of Social Work, and College of Public Health at Temple University..

Jeffrey Boles, Temple University’s Fox School of Business..

Miguel Muñoz-Laboy, Temple University’s School of Social Work..

Ethan C. Levine, Temple University’s School of Social Work..

Chukwuemeka Ayamele, Columbia University..

Rebecca Eisenberg, Temple University’s School of Social Work..

Justin Manusov, University of Colorado-Boulder School of Law..

Jeffrey Draine, Temple University’s School of Social Work..

References

- 1.RWJ Foundation, “What’s Law Got to Do With It? How Medical-Legal Partnerships Reduce Barriers to Health,” July 8, 2015, available at <http://www.rwjf.org/en/culture-of-health/2015/07/what_s_law_got_todo.html> (last visited May 30, 2017).

- 2.National Center for Medical-Legal Partnershiptoolkit. Phase I: Laying the Groundwork (2014).

- 3.RWJ Foundation, “Health Care’s Blind Side: The Overlooked Connection between Social Needs and Good Health,” 2011, available at <http://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2011/12/health-care-s-blind-side.html> (last visited May 30, 2017).

- 4.van Griensven F and Stall RD, “Racial Disparity in HIV Incidence in MSM in the United States: How Can It Be Reduced?” AIDS 28, no. 1 (2014): 129–130; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ricks JM, Crosby RA, and Terrell I, “Elevated Sexual Risk Behaviors among Postincarcerated Young African American Males in the South,” American Journal of Men’s Health 9, no. (2015): 132–138; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Milburn NG, Lightfoot M, and Rueda VC, “Challenge of HIV Prevention in Diverse Communities,” in Leong FTL, Comas-Díaz L, and Nagayama Hall GC, and McLoyd VC, Trimble JE, and Leong FTL et al. , eds., APA Handbook of Multicultural Psy-chology, Vol. 2: Applications and Training (Washington, D,C.: American Psychological Association, 2014): at 577–592; [Google Scholar]; Sullivan PS, Rosenberg ES, Sanchez TH, Kelley CF, Luisi N, and Cooper HL et al. , “Explaining Racial Disparities in HIV Incidence in Black and White Men Who Have Sex with Men in Atlanta, GA: A Prospective Observational Cohort Study,” Annals of Epidemiology 25, no. 6 (2015): 445–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CDC, HIV Diagnosis Data Are Estimates from All 50 States, the District of Columbia, and 6 U.S. Dependent Areas. Rates Do Not Include U.S. Dependent Areas (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Id.

- 7.Lambda Legal, HIV Stigma and Discrimination in the U.S.: An Evidence-Based Report (2010).

- 8.The Center for HIV Law & Policy, Housing Rights of People Living with HIV/AIDS: A Primer (2010).

- 9.Miyashita A, Hasebhush A, Wilson BDM, Meyer I, Nezhad S, and Sears B, “The Legal Needs of People Living with HIV: Evaluating Access to Justice in Los Angeles,” April 2015, The Williams Institute, available at <http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/research/health-and-hiv-aids/the-legal-needs-of-people-living-with-hiv-evaluating-access-to-justice-in-los-angeles/#sthash.vv4qN4Bv.dpuf> (last visited May 30, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen E, Fullerton DF, Retkin R, Weintraub D, Tames P, and Brandfield J et al. , “Medical-Legal Partnership: Collaborating with Lawyers to Identify and Address Health Disparities,” Journal of General Internal Medicine 25, Supp. 2 (May 2010): S136–S139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lawton EM and Sandel M, “Medical-Legal Partnerships: Collaborating to Transform Healthcare for Vulnerable Patients: A Symposium Introduction and Overview,” Journal of Legal Medicine 35, no. 1 (2014): 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, and Altman DG, “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses: The PRISMA Statement,” International Journal of Surgery 8, no. 5 (2010): 336–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Coalition of Anti-Violence, Anti-lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Violence in 2008 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hallarman L, Snow D, Kapoor M, Brown C, Rodabaugh K, and Lawton E, “Blueprint for Success: Translating Innovations from the Field of Palliative Medicine to the Medical-Legal Partnership,” Journal of Legal Medicine 35, no. (2014): 179–194; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Atkins D, Heller SM, DeBartolo E, and Sandel M, “Medical-Legal Partnership and Healthy Start: Integrating Civil Legal Aid Services into Public Health Advocacy,” Journal of Legal Medicine 35, no. 1 (2014): 195–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beck AF, Klein MD, Schaffzin JK, Tallent V, Gillam M, Kahn RS, “Identifying and Treating a Substandard Housing Cluster Using a Medical-Legal Partnership,” Pediatrics 130, no. 5 (2012): 831–838; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Klein MD, Beck AE, Henize AW, Parrish DS, Fink EE, and Kahn RS, “Doctors and Lawyers Collaborating to Help Children — Outcomes from a Successful Partnership between Professions,” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 24, no. 3 (2013):1063–1073; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Pettignano R, Bliss LR, Caley SB, and McLaren S, “Can Access to a Medical-Legal Partnership Benefit Patients with Asthma Who Live in an Urban Community?” Journal of Health Care for the Poor & Underserved 24, no. 2 (2013): 706–717; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Pettignano R, Caley SB, and Bliss LR, “Medical-Legal partnership: Impact on Patients with Sickle Cell Disease,” Pediatrics 128, no. 6 (2011): e1482–e1488; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Rodabaugh KJ, Hammond M, Myszka D, and Sandel M, “A Medical-Legal Partnership as a Component of a Palliative Care Model,” Journal of Palliative Medicine 13, no. 1 (2010): 15–18; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Taylor DR, Bernstein BA, Carroll E, Oquendo E, Peyton L, and Pachter LM, “Keeping the Heat on for Children’s Health: A Successful Medical-Legal Partnership Initiative to Prevent Utility Shutoffs in Vulnerable Children,” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 26, no. 3 (2015): 676–685; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Teufel JA, Werner D, Goffinet D, Thorne W, Brown SL, and Gettinger L, “Rural Medical-Legal Partnership and Advocacy: A Three-Year Follow-Up Study,” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 23, no. 2 (2012): 705–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandel M, Suther E, Brown C, Wise M, and Hansen M, “The MLP Vital Sign: Assessing and Managing Legal Needs in the Healthcare Setting,” Journal of Legal Medicine 35, no. 1 (2014): 41–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fleishman SB, Retkin R, Brandfield J, and Braun V, “The Attorney as the Newest Member of the Cancer Treatment Team,” Journal of Clinical Oncology 24, no. 13 (2006): 2123–2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Sullivan MM et al. , “Environmental Improvements Brought by the Legal Interventions in the Homes of Poorly Controlled Inner-city Adult Asthmatic Patients: A Proof-of-Concept Study,” Journal of Asthma 49, no. 9 (2012): 911–917; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ryan AM, Kutob RM, Suther E, Hansen M, and Sandel M, “Pilot Study of Impact of Medical-Legal Partnership Services on Patients’ Perceived Stress and Wellbeing,” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 23, no. 4 (2012): 1536–1546; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Sege R, Preer G, Morton SJ, Cabral H, Morakinyo O, and Lee V et al. , “Medical-Legal Strategies to Improve Infant Health Care: A Randomized Trial,” Pediatrics 136, no. 1 (2015): 97–106; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Weintraub D, Rodgers MA, Botcheva L, Loeb A, Knight R, Ortega K et al. , “Pilot Study of Medical-Legal Partnership to Address Social and Legal Needs of Patients,” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 21, no. 2 (2010): 157–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.See Fleishman et al. , supra note 17.

- 20.See Weintraub et al. , supra note 18.

- 21.See Sandel et al. , supra note 16.

- 22.See Klein et al. , supra note 15.

- 23.See Pettignano (2013), supra note 15.

- 24.See Rodabaugh et al. , supra note 15.

- 25.See Klein et al. , supra note 15.

- 26.See Beck et al. , supra note 15.

- 27.See Pettignano (2013), supra note 15.

- 28.See Pettignano (2011), supra note 15.

- 29.See Teufel et al. , supra note 15.

- 30.See Taylor et al. , supra note 15.

- 31.See Sege et al. , supra note 18.

- 32.See O’Sullivan et al. , supra note 18.

- 33.See Weintraub, supra note 18.

- 34.Ryan et al. , supra note 18.

- 35.See Beck, Klein, and Pettignano (2013), and Pettignano (2011), supra note 18;; Taylor et al. , supra 15;; Sandel et al. , supra note 16;; Ryan et al. and Sege et al. , supra note 18;; Taylor et al. , supra note 15.

- 36.See O’Sullivan et al. , supra note 18.

- 37.See Rodabaugh et al. , supra note 15;; Teufel et al. , supra note 15.

- 38.Id. (Teufel).

- 39.Sege R, Kaplan-Sanoff M, Morton S, Velasco-Hodgson C, Preer G, and Morakinvo G et al. , “Project DULCE: Strengthening Families through Enhanced Primary Care,” Zero to Three 35, no. 1 (2014): 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- 40.See Sege et al. , supra note 18.

- 41.See Atkins et al. , supra note 14.

- 42.See National Coalition of Anti-Violence, supra note 13.

- 43.Flay BR, Snyder FJ, and Petraitis J, “The Theory of Triadic Influence,” in DiClemente RJ, Crosby RA, and Kegler MC, eds., Emerging Theories in Health Promotion, Practice and Research, 2nd ed. (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2009): 451–510. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ajzen I and Driver BL, “Prediction of Leisure Participation from Behavioral, Normative, and Control Beliefs: An Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior,” Leisure Sciences 13, no. 3 (1991): 185–204. [Google Scholar]

- 45.See Lawton et al. , supra note 11;; Moher et al. , supra note 11;; National Coalition, supra note 13;; Hallarman, supra note 14;; Atkins et al. , supra note 14;; Beck et al. , supra note 15;; Klein, supra note 15.

- 46.Brown CA and Richard JL, “The Stepped Wedge Trial Design: A Systematic Review,” BMC Medical Research Methodology 6 (2006): 54–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Campbell AT, Sicklick J, Galowitz P, Retkin R, and Fleishman SB, “How Bioethics Can Enrich Medical-Legal Collaborations,” Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 38, no. 4 (2010): 847–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.See Model Rules of Professional Conduct, at R. 1.7 and 1.9 (2012).

- 49.Boumil M, Freitas DR, and Freitas CR, “Multidisciplinary Representation of Patients: The Potential for Ethical Issues and Professional Duty Conflicts in the Medical-Legal Partnership Model,” Health Care Law and Policy 13, no. 1 (2010): 107–138. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mimiaga M, Biello K, Robertson A, Oldenburg C, Rosen-berger J, and O’Cleirigh C et al. , “High Prevalence of Multiple Syndemic Conditions Associated withsickle Sexual Risk Behavior and HIV Infection among a Large Sample of Spanish- and Portuguese-Speaking Men Who Have Sex with Men in Latin America,” Archives of Sexual Behavior 44, no. 7 (2015): 1869–1878; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Starks T, Millar B, Eggleston J, and Parsons J, “Syndemic Factors Associated with HIV Risk for Gay and Bisexual Men: Comparing Latent Class and Latent Factor Modeling,” AIDS & Behavior 18, no. 11 (2014): 2075–2079, at 5p; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Oldenburg CE, Perez-Brumer AG, and Reisner SL, “Poverty Matters: Contextualizing the Syndemic Condition of Psychological Factors and Newly Diagnosed HIV Infection in the United States,” AIDS 28, no. 18 (2014): 2763–2769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]