Abstract

Lorlatinib is a potent, brain‐penetrant, third‐generation anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)/ROS proto‐oncogene 1 (ROS1) tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) that is active against most known resistance mutations. This is an ongoing phase 1/2, multinational study (NCT01970865) investigating the efficacy, safety and pharmacokinetics of lorlatinib in ALK‐rearranged/ROS1‐rearranged advanced non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with or without intracranial (IC) metastases. Because patterns of ALK TKI use in Japan differ from other regions, we present a subgroup analysis of Japanese patients. Patients were enrolled into six expansion (EXP) cohorts based on ALK/ROS1 mutation status and treatment history. The primary endpoint was the objective response rate (ORR) and the IC‐ORR based on independent central review. Secondary endpoints included pharmacokinetic evaluations. At data cutoff, 39 ALK‐rearranged/ROS1‐rearranged Japanese patients were enrolled across the six expansion cohorts; all received lorlatinib 100 mg once daily. Thirty‐one ALK‐rearranged patients previously treated with ≥1 ALK TKI (EXP2 to EXP5) were evaluable for ORR and 15 were evaluable for IC‐ORR. The ORR and the IC‐ORR for Japanese patients in EXP2‐5 were 54.8% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 36.0‐72.7) and 46.7% (95% CI: 21.3‐73.4), respectively. Among patients who had received prior alectinib only (EXP3B), the ORR was 42.9%; 95% CI: 9.9‐81.6). The most common treatment‐related adverse event (TRAE) was hypercholesterolemia (79.5%). Hypertriglyceridemia was the most common grade 3/4 TRAE (25.6%). Single‐dose and multiple‐dose pharmacokinetic profiles among Japanese patients were similar to those in non–Japanese patients. Lorlatinib showed clinically meaningful responses and IC responses among ALK‐rearranged Japanese patients with NSCLC who received ≥1 prior ALK TKI, including meaningful responses among those receiving prior alectinib only. Lorlatinib was generally well tolerated.

Keywords: anaplastic lymphoma kinase, carcinoma, non–small‐cell lung, crizotinib, lorlatinib, tyrosine kinase inhibitor

Lorlatinib showed clinically meaningful responses (54.8%; 95% CI: 36.0‐72.7) and intracranial responses (46.7%; 95% CI: 21.3‐73.4) among ALK‐rearranged Japanese patients with non–small cell lung cancer who received ≥1 prior ALK TKI, including meaningful responses among those receiving prior alectinib only (42.9%; 95% CI: 9.9‐81.6). Lorlatinib was generally well tolerated, with a similar adverse event profile among Japanese patients to that among the overall population.

1. INTRODUCTION

Chromosomal rearrangements of the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene are oncogenic drivers in 3‐5% of non–small cell lung cancers (NSCLC), 1 , 2 , 3 and lung cancers with these rearrangements are sensitive to ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI). 4

The first ALK TKI, crizotinib, was approved in the United States (in 2011), the European Union (EU) (in 2012) and Japan (in 2012) for the treatment of patients with ALK‐rearranged NSCLC 5 , 6 , 7 on the basis of two single‐arm trials demonstrating objective response rates (ORR) of 50% and 61% and median response durations of 42 and 48 weeks. However, most crizotinib‐treated patients acquire resistance, through secondary ALK domain mutations and/or other molecular mechanisms, or develop disease progression due to poor central nervous system (CNS) penetration. 8 , 9

To overcome crizotinib resistance, second‐generation ALK TKI with greater potency and improved intracranial activity, 10 such as ceritinib 11 and alectinib, 12 have been developed and have shown clinical benefit in ALK‐rearranged NSCLC patients, both in those who are treatment‐naïve and who are crizotinib‐refractory. 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 Alectinib was first approved in Japan (in 2014) for use in the first‐line setting at a dose of 300 mg twice daily 25 on the basis of combined efficacy, safety and pharmacokinetic data from the Japanese AF‐001JP trial. 26 Outside Japan, it is used at a dose of 600 mg twice daily. 14 Given the results of the J‐ALEX study 27 and recommendations in The Japanese Lung Cancer Society Guideline for non–small cell lung cancer, stage IV, 28 most ALK‐rearranged NSCLC patients receive first‐line treatment with alectinib in Japan today. Nevertheless, most patients develop resistance to second‐generation ALK TKI, with distinct spectra of ALK resistance mutations. The frequency of one mutation, ALK G1202R increases significantly after exposure to second‐generation agents. 29

Lorlatinib is a highly potent, selective third‐generation ALK/ROS proto‐oncogene 1 (ROS1) TKI that was developed to penetrate the blood‐brain barrier 30 and to retain potency against most known ALK resistance mutations, 29 including ALK L1196M and G1202R, which can arise during crizotinib or second‐generation TKI treatment. In phases 1 and 2 of an ongoing study among patients with ALK‐rearranged advanced NSCLC, lorlatinib demonstrated clinically meaningful and durable responses, including among patients who had received prior TKI therapies and had CNS metastases. 31 , 32 Lorlatinib was generally well tolerated, and adverse events (AE) were predominantly grade 1 or 2 in severity; the most frequently reported AE include hypercholesterolemia and hypertriglyceridemia. 31 , 32

In Japan, lorlatinib was approved in September 2018 33 for patients with ALK‐rearranged unresectable advanced and/or recurrent NSCLC with resistance or intolerance to ALK TKI. Lorlatinib was approved in the United States in November 2018 34 and in the EU in May 2019 35 for the treatment of patients with ALK‐rearranged metastatic NSCLC who had disease progression on crizotinib and ≥1 other ALK TKI or who had disease progression on alectinib or ceritinib as the first ALK TKI received.

Given that patterns of ALK TKI use vary across geographical regions due to differences in local clinical practice (eg, alectinib is more commonly used in Japan [approval date 2014] 25 than in the United States [approval date 2015] 36 or the EU [approval date 2017] 37 ), we report post hoc analyses of safety, efficacy and pharmacokinetics of lorlatinib in the Japanese subpopulation of the aforementioned phase 1/2 study.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study design and patients

The safety of lorlatinib at the recommended phase 2 dose (100 mg once per day [QD]) among Japanese patients was evaluated in a lead‐in cohort (LIC) before commencement of the phase 2 portion of the study.

Full methodological details have been previously reported in Solomon et al. 32 Eligible patients were enrolled into expansion cohorts of the phase 2 portion of the study B7461001 based on their ALK/ROS1 mutation status and treatment history. EXP1: ALK‐rearranged; treatment‐naïve; EXP2: ALK‐rearranged; disease progression following prior crizotinib only; EXP3A: ALK‐rearranged; disease progression following prior crizotinib plus 1‐2 regimens of chemotherapy given before or after crizotinib; EXP3B: ALK‐rearranged; disease progression following 1 prior non–crizotinib ALK TKI ± any number of chemotherapy regimens; EXP4: ALK‐rearranged; disease progression following two prior ALK TKI ± any number of chemotherapy regimens; EXP5: ALK‐rearranged; three prior ALK TKI ± any number of chemotherapy regimens; EXP6: ROS1‐rearranged; any prior treatment or treatment‐naïve.

In the current efficacy analysis of Japanese patients, we did not include EXP1 (treatment naïve for ALK TKI, n = 3) or EXP6 (ROS1+, n = 5) because lorlatinib is not approved for use in these settings by the Japanese regulatory authority as of January 2020. 28 However, because the safety of lorlatinib is not dependent upon treatment cohort allocation, we present safety data for EXP1‐6 combined. As per Solomon et al, 32 efficacy cohorts were pooled into EXP2‐3A (pretreated with first generation crizotinib as their only ALK TKI), EXP3B (pretreated with a second‐generation ALK TKI only; in this cohort among Japanese patients, the only second‐generation ALK TKI used was alectinib) and EXP4‐5 (pretreated with two or three ALK TKI; in this cohort among Japanese patients, the ALK TKI used were crizotinib, alectinib or ceritinib).

2.2. Treatments and procedures

Lorlatinib was administered orally at a starting dose of 100 mg once daily continuously in 21‐day cycles. Treatment continued until investigator‐assessed disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, withdrawal of consent, or death. Continued treatment with lorlatinib was allowed if there was evidence of clinical benefit in the opinion of the investigator. Dose delay and/or reductions were permitted to manage toxicities based on investigator discretion. Patients requiring >3 dose reductions were discontinued from treatment.

Scheduled visits occurred on days 1, 8 and 15 of the first 21‐day cycle and then every 3 weeks (reduced to every 6 weeks after 38 cycles), at treatment discontinuation and at 28‐35 days’ post–treatment. Tumor imaging (chest, abdomen and pelvis computed tomography and brain magnetic resonance imaging scans) were performed at baseline, 6‐weekly until 30 months and 12‐weekly thereafter until disease progression or the start of a new anticancer treatment.

Safety assessments were performed in all patients at baseline and at every visit. AE were graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4.03 and were assessed from treatment start until at least 28 days after final lorlatinib administration. AEs were also grouped according to cluster terms comprising AEs that represent similar clinical symptoms/syndromes (see Appendix S1 for definitions).

2.3. Endpoints and assessments

The primary endpoint was the tumor ORR, defined as the proportion of patients with an objective response (OR); that is, a confirmed complete response (CR) or partial response (PR), as assessed by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST) v1.1 or modified RECIST v1.1 for intracranial (IC) ORR based on independent central review (ICR).

Secondary endpoints included: duration of response (DOR), defined as the time from the first documentation of objective tumor response to the first documentation of disease progression or to death from any cause; best percentage change from the baseline in tumor size based on ICR; progression‐free survival (PFS), defined as the time from first dose to first documentation of objective disease progression or to death on study due to any cause; patient‐reported outcomes (PRO) using European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (QLQ‐C30) and its corresponding Lung Cancer Module (QLQ‐LC13); single and multiple‐dose pharmacokinetics among Japanese and non–Japanese patients with available pharmacokinetic data; and safety and tolerability.

2.4. Statistical methods

The statistical methods used were the same as for the primary analysis published in Solomon et al (2018). 32 The data cutoff for this analysis was 2 February 2018. This study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT01970865.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Demography and Baseline Disease Characteristics

Between 15 September 2015 and 3 October 2016, 276 patients were enrolled across all cohorts (EXP1‐6) in the overall population, of whom 275 received at least one dose of lorlatinib. Three Japanese patients were enrolled in the LIC and received lorlatinib 100 mg QD (overall mean age of 44.3 years; 1 male patient [ALK‐rearranged previously treated with alectinib] and 2 female patients [1 ALK‐rearranged and one ROS1‐rearranged, both previously treated with crizotinib]; and all 3 had received previous brain‐directed radiotherapy). Of 39 Japanese patients enrolled in all remaining cohorts (EXP1‐6), 7 were in EXP2‐3A, 7 in EXP3B, 17 in EXP4‐5 and 31 in EXP2‐5 (Figure S1). The mean age among Japanese patients in EXP1‐6 was similar to that among all patients, but the proportions of male patients and those with cerebral metastases at baseline were smaller in the Japanese population compared to the overall population (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and patient demographics

| Japanese patients | All patients | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior crizotinib ± CT (EXP2‐3A) | Prior non–crizotinib ALK TKI ± CT (EXP3B) | ≥2 prior ALK TKI a ± CT (EXP4‐5) | Pooled efficacy group (EXP2‐5) | Pooled safety group (EXP1‐6) | Pooled efficacy group (EXP2‐5) | Pooled safety group (EXP1‐6) | |

| Number of patients | 7 | 7 | 17 | 31 | 39 | 198 | 275 |

| Age, years | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | 60.1 (14.7) | 54.9 (12.9) | 45.4 (7.5) | 50.8 (12.1) | 52.2 (12.3) | 53.2 (11.9) | 53.6 (12.1) |

| Range | 47‐85 | 33‐68 | 32‐60 | 32‐85 | 32‐85 | 29‐85 | 19‐85 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 6 (85.7) | 3 (42.9) | 12 (70.6) | 21 (67.7) | 27 (69.2) | 117 (59.1) | 157 (57.1) |

| Male | 1 (14.3) | 4 (57.1) | 5 (29.4) | 10 (32.3) | 12 (30.8) | 81 (40.9) | 118 (42.9) |

| Race, n (%) | |||||||

| White | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 97 (49.0) | 132 (48.0) |

| Asian | 7 (100.0) | 7 (100.0) | 17 (100.0) | 31 (100.0) | 39 (100.0) | 70 (35.4) | 103 (37.5) |

| Black | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1.1) |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 (4.0) | 12 (4.4) |

| Unspecified b | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 22 (11.1) | 25 (9.1) |

| ECOG performance status | |||||||

| 0 | 5 (71.4) | 4 (57.1) | 8 (47.1) | 17 (54.8) | 19 (48.7) | 89 (44.9) | 119 (43.3) |

| 1 | 2 (28.6) | 3 (42.9) | 9 (52.9) | 14 (45.2) | 20 (51.3) | 102 (51.5) | 146 (53.1) |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 (3.5) | 10 (3.6) |

| Brain metastases present at baseline c | 3 (42.9) | 0 | 12 (70.6) | 15 (48.4) | 18 (46.2) | 131 (66.2) | 163 (59.3) |

| Number of brain metastases at baseline among patients with metastases c | |||||||

| 1‐3 | 0 | 0 | 4/12 (33.3) | 4/15 (26.7) | 6/18 (33.3) | 51/131 (38.9) | 65/163 (39.9) |

| 4‐6 | 2/3 (66.7) | 0 | 5/12 (41.7) | 7/15 (46.7) | 8/18 (44.4) | 43/131 (32.8) | 56/163 (34.4) |

| 7‐9 | 1/3 (33.3) | 0 | 2/12 (16.7) | 3/15 (20.0) | 3/18 (16.7) | 24/131 (18.3) | 28/163 (17.2) |

| ≥10 | 0 | 0 | 1/12 (8.3) | 1/15 (6.7) | 1/18 (5.6) | 15/131 (11.5) | 17/163 (10.4) |

| Median | 5.0 | 0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| Previous radiotherapy | 0 | 3/7 (42.9) | 11/17 (64.7) | 14/31 (45.2) | 18/39 (46.2) | 125/198 (63.1) | 154/275 (56.0) |

| Previous brain‐directed radiotherapy | 0 | 0 | 10/17 (58.8) | 10/31 (32.3) | 12/39 (30.8) | 86/198 (43.4) | 103/275 (37.5) |

| Number of previous chemotherapy regimens | |||||||

| 0 | 5/7 (71.5) | 1/7 (14.3) | 1/17 (5.9) | 7/31 (22.6) | 9/39 (23.1) | 65/198 (32.8) | 105/275 (38.2) |

| 1 | 2/7 (28.6) | 4/7 (57.1) | 7/17 (41.2) | 13/31 (41.9) | 14/39 (35.9) | 83/198 (41.9) | 96/275 (34.9) |

| 2 | 0 | 2/7 (28.6) | 4/17 (23.5) | 6/31 (19.4) | 7/39 (17.9) | 30/198 (15.2) | 43/275 (15.6) |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 3/17 (17.6) | 3/31 (9.7) | 7/39 (17.9) | 12/198 (6.1) | 22/275 (8.0) |

| ≥4 | 0 | 0 | 2/17 (11.8) | 2/31 (6.5) | 2/39 (5.1) | 8/198 (4.0) | 9/275 (3.3) |

| Number of previous ALK or ROS1 TKI regimens | |||||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6/39 (15.4) | 0 | 43/275 (15.6) |

| 1 | 7/7 (100.0) | 7/7 (100.0) | 0 | 14/31 (45.2) | 16/39 (41.0) | 87/198 (43.9) | 117/275 (42.5) |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 10/17 (58.8) | 10/31 (32.3) | 10/39 (25.6) | 65/198 (32.8) | 67/275 (24.4) |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 7/17 (41.2) | 7/31 (22.6) | 7/39 (17.9) | 42/198 (21.2) | 44/275 (16.0) |

Data are n (%) unless specified otherwise. Data in EXP2‐3A, EXP3B, EX4‐5 and EXP2‐5 groups employ the intention‐to‐treat analysis set; data in the EXP1‐6 group employ the safety analysis set.

Abbreviations: ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; CT, chemotherapy; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; EXP, expansion cohort; ROS1, ROS proto‐oncogene 1; SD, standard deviation; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Lines of therapy (if the same TKI was given twice, this was counted as two prior lines of treatment).

In France, race was not allowed to be collected as per local regulations.

By independent central review and includes measurable and non–measurable baseline central nervous system lesions.

3.2. Safety

Among the three Japanese patients enrolled in the LIC, 1 patient had a grade 3 treatment‐related adverse event (TRAE) of elevation in blood creatine phosphokinase and lipase, and no patients had dose‐limiting toxicities.

In the phase 2 part of the study, the most frequent TRAE occurring in ≥30% among Japanese patients were hypercholesterolemia (79.5%), hypertriglyceridemia (76.9%), peripheral neuropathy (43.6%) and edema (35.9%) (Table 2). These AE occurred with a similar frequency among all patients (83.6%, 66.5%, 33.8% and 44.0%, respectively) (Table 2). Among Japanese patients, the median (range) time to onset of hypercholesterolemia was 14 days (5‐41) and hypertriglyceridemia was 13 days (5‐104), calculated using all AE regardless of causality.

Table 2.

Treatment‐related adverse events occurring in ≥10% of Japanese patients treated with lorlatinib (all cohorts: EXP1‐6) with corresponding treatment‐related adverse events in all patients (safety analysis sets)

| Japanese patients (N = 39) | All patients (N = 275) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All grades | Grade 1‐2 | Grade 3‐4 | All grades | Grade 1‐2 | Grade 3‐4 | |

| Any TRAE | 38 (97.4) | 18 (46.2) | 20 (51.3) | 262 (95.3) | 135 (49.1) | 127 (46.2) |

| Hypercholesterolemia a | 31 (79.5) | 24 (61.5) | 7 (17.9) | 230 (83.6) | 185 (67.3) | 45 (16.4) |

| Hypertriglyceridemia a | 30 (76.9) | 20 (51.3) | 10 (25.6) | 183 (66.5) | 137 (49.8) | 46 (16.7) |

| Peripheral neuropathy a | 17 (43.6) | 17 (43.6) | 0 | 93 (33.8) | 87 (31.6) | 6 (2.2) |

| Edema a | 14 (35.9) | 11 (28.2) | 3 (7.7) | 121 (44.0) | 115 (41.8) | 6 (2.2) |

| Diarrhea | 8 (20.5) | 8 (20.5) | 0 | 36 (13.1) | 35 (12.7) | 1 (0.4) |

| Cognitive effects a | 7 (17.9) | 7 (17.9) | 0 | 64 (23.3) | 61 (22.2) | 3 (1.1) |

| ALT increased | 7 (17.9) | 7 (17.9) | 0 | 28 (10.2) | 26 (9.5) | 2 (0.7) |

| Constipation | 7 (17.9) | 7 (17.9) | 0 | 26 (9.5) | 26 (9.5) | 0 |

| Tinnitus | 7 (17.9) | 7 (17.9) | 0 | 12 (4.4) | 12 (4.4) | 0 |

| AST increased | 6 (15.4) | 6 (15.4) | 0 | 33 (12.0) | 32 (11.6) | 1 (0.4) |

| Dizziness | 6 (15.4) | 5 (12.8) | 1 (2.6) | 26 (9.5) | 24 (8.7) | 2 (0.7) |

| Weight increased | 6 (15.4) | 6 (15.4) | 0 | 62 (22.5) | 52 (18.9) | 10 (3.6) |

| Mood effects a | 5 (12.8) | 4 (10.3) | 1 (2.6) | 44 (16.0) | 41 (14.9) | 3 (1.1) |

| Nausea | 5 (12.8) | 5 (12.8) | 0 | 23 (8.4) | 23 (8.4) | 0 |

| Arthralgia | 4 (10.3) | 4 (10.3) | 0 | 30 (10.9) | 29 (10.5) | 1 (0.4) |

| Hallucination, auditory | 4 (10.3) | 3 (7.7) | 1 (2.6) | 5 (1.8) | 4 (1.5) | 1 (0.4) |

| Headache | 4 (10.3) | 4 (10.3) | 0 | 19 (6.9) | 19 (6.9) | 0 |

| Hyperuricemia | 4 (10.3) | 4 (10.3) | 0 | 10 (3.6) | 10 (3.6) | 0 |

| Localized edema | 4 (10.3) | 2 (5.1) | 2 (5.1) | 7 (2.5) | 5 (1.8) | 2 (0.7) |

| Vomiting | 4 (10.3) | 4 (10.3) | 0 | 13 (4.7) | 12 (4.4) | 1 (0.4) |

Data are n (%).

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; EXP, expansion cohort; TRAE, treatment‐related adverse event.

Cluster term comprising adverse events that represent similar clinical symptoms/syndromes (see Appendix S1 for definitions).

Other TRAE occurring among <30% and ≥10% of Japanese patients are shown in Table 2. With the exception of 1 patient with a grade 3 TRAE of mood change, all cognitive and mood TRAE were of grade 1 or 2 level. The median time to first onset of cognitive effects AE was day 211.0 (range 1‐263), calculated using all AE regardless of causality.

Among Japanese patients with TRAE, dose reduction, temporary dose interruption and permanent discontinuation due to these events occurred in 8 (20.5%), 19 (48.7%) and 1 (2.6%), respectively. The permanent discontinuation was due to a TRAE of tinnitus, which resolved after discontinuation of study treatment. Corresponding proportions among all patients were similar: 24.7%, 33.8% and 3.3%, respectively.

3.3. Efficacy

3.3.1. Patients who received ≥1 prior anaplastic lymphoma kinase tyrosine kinase inhibitor (pooled EXP2‐5)

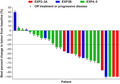

Of 31 Japanese patients in EXP2‐5, an OR was observed in 17 patients (ORR = 54.8%; 95% confidence interval [CI] 36.0‐72.7), a CR in 2 (6.5%), a PR in 15 (48.4%), and stable disease (SD) in 10 (32.3%) (Table 3; Figure 1). These percentages were similar to those among all patients in EXP2‐5; OR 50.0%, CR 2.0%, PR 48.0% and SD 26.8%, respectively (Table 3). At the time of analysis, the median DOR had not been reached among Japanese patients. Of 15 Japanese patients in EXP2‐5 with measurable baseline CNS lesions per ICR, an intracranial OR was observed in 7 patients (ORR = 46.7%; 95% CI 21.3‐73.4), a CR in 6 (40.0%), a PR in 1 (6.7%) and SD in 7 (46.7%) (Table 3). At the time of analysis, the median intracranial DOR had not been reached. Responses to lorlatinib were rapid in onset among both Japanese and all patients, with a median time to tumor response of 1.4 months in both populations.

Table 3.

Overall and intracranial responses by independent central review among Japanese and all patients (ITT analysis set)

| Japanese patients | All patients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior crizotinib ± CT (EXP2‐3A) | Prior non–crizotinib ALK TKI ± CT (EXP3B) | ≥2 prior ALK TKIs a ± CT (EXP4‐5) | ≥1 prior ALK TKI ± CT (EXP2‐5) | ≥1 prior ALK TKI ± CT (EXP2‐5) | |

| Overall responses | |||||

| Number of patients | 7 | 7 | 17 | 31 | 198 |

| Best overall response | |||||

| Complete response b | 0 | 1 (14.3) | 1 (5.9) | 2 (6.5) | 4 (2.0) |

| Partial response b | 6 (85.7) | 2 (28.6) | 7 (41.2) | 15 (48.4) | 95 (48.0) |

| Stable disease | 1 (14.3) | 3 (42.9) | 6 (35.3) | 10 (32.3) | 53 (26.8) |

| Objective progression | 0 | 1 (14.3) | 3 (17.6) | 4 (12.9) | 32 (16.2) |

| Indeterminate | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 (7.1) |

| Confirmed ORR (%; 95% CI) c | 6 (85.7; 42.1‐99.6) | 3 (42.9; 9.9‐81.6) | 8 (47.1; 23.0‐72.2) | 17 (54.8; 36.0‐72.7) | 99 (50.0; 42.8‐57.2) |

| Median duration of response, months (95% CI) d | NR (NE–NE) | NR (NE–NE) | 9.9 (4.2–NE) | NR (9.9–NE) | 11.1 (6.9–NE) |

| Intracranial responses | |||||

| Number of patients e | 3 | 0 | 12 | 15 | 131 |

| Best overall IC response | |||||

| Complete response b | 2 (66.7) | NA f | 4 (33.3) | 6 (40.0) | 37 (28.2) |

| Partial response b | 0 | NA f | 1 (8.3) | 1 (6.7) | 34 (26.0) |

| Stable disease | 1 (33.3) | NA f | 6 (50.0) | 7 (46.7) | 39 (29.8) |

| Objective progression | 0 | NA f | 1 (8.3) | 1 (6.7) | 10 (7.6) |

| Indeterminate | 0 | NA f | 0 | 0 | 11 (8.4) |

| Confirmed IC ORR (%; 95% CI) c | 2 (66.7; 9.4‐99.2) | NA f | 5 (41.7; 15.2‐72.3) | 7 (46.7; 21.3‐73.4) | 71 (54.2; 45.3‐62.9) |

| Median duration of IC response, months (95% CI) d | NR (NE–NE) | NA f | 15.0 (6.9–NE) | NR (15.0–NE) | 19.5 (14.5–NE) |

Data are n (%) unless specified otherwise.

Abbreviations: ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; CI, confidence interval; CT, chemotherapy; EXP, expansion cohort; IC, intracranial; ITT, intention‐to‐treat; NE, not estimable; NR, not reached; ORR, objective response rate; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Lines of therapy (if the same TKI was given twice, this was counted as two prior lines of treatment).

Confirmed response

Using exact method based on binomial distribution.

Kaplan‐Meier estimated median with 95% CI calculated using the Brookmeyer and Crowley method.

Number of patients with ≥1 measurable central nervous system lesion at baseline.

No patient met the reporting criteria.

Figure 1.

Waterfall plot of best percentage change in tumor size based on independent central review (EXP2 to 5, n = 28, Japanese ITT analysis set). EXP, expansion cohort; ITT, intention‐to‐treat

3.3.2. Patients who received alectinib as the last prior anaplastic lymphoma kinase tyrosine kinase inhibitor (pooled EXP2‐5)

Of 20 Japanese patients in EXP2‐5 who received alectinib as the last prior ALK TKI, an OR was observed in 9 patients (ORR = 45.0%; 95% CI 23.1‐68.5). Among all patients, the corresponding value for OR was 25/62 (ORR = 40.3%; 95% CI 28.1‐53.6).

3.3.3. Patients who received prior crizotinib only (EXP2‐3A)

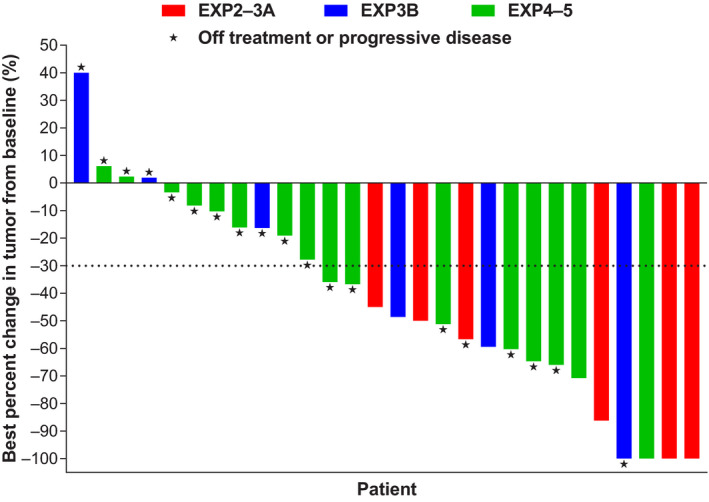

Of 7 Japanese patients in EXP2‐3A, an OR was observed in 6 patients (ORR = 85.7%; 95% CI 42.1‐99.6), a CR in 0, a PR in 6 (85.7%) and SD in 1 (14.3%) (Table 3). At the time of analysis, the median DOR had not been reached (Table 3). Of 3 Japanese patients in EXP2‐3A with measurable baseline CNS lesions based on ICR, an intracranial OR was observed in 2 patients (ORR = 66.7%; 95% CI 9.4‐99.2) and SD in 1 (33.3%) (Table 3). At the time of analysis, the median intracranial DOR had not been reached. Median PFS was not reached among Japanese patients and was 11.1 months (95% CI 8.2–not estimable [NE]) among all patients (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan‐Meier progression‐free survival by independent central review among Japanese patients (ITT analysis set). CI, confidence interval; EXP, expansion cohort; ITT, intention‐to‐treat; NE, not estimable; NR, not reached; PFS, progression‐free survival

3.3.4. Patients who received prior alectinib only (EXP3B)

Of 7 Japanese patients in EXP3B, all of whom received alectinib as their sole prior ALK TKI, an OR was observed in 3 patients (ORR = 42.9%; 95% CI 9.9‐81.6), a CR in 1 (14.3%), a PR in 2 (28.6%), and SD in 3 (42.9%) (Table 3). At the time of analysis, the median DOR had not been reached (Table 3). No Japanese patients in EXP3B had measurable baseline CNS lesions, based on ICR. Median PFS was not reached among Japanese patients and was 5.5 months (95% CI 2.9‐8.2) among all patients (Figure 2). Efficacy data for individual patients are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Lorlatinib efficacy data among Japanese patients receiving alectinib as their only prior ALK TKI (cohort EXP3B)

| Patient | Agent for advanced/metastatic disease | Best response for lorlatinib | Progression‐Free Survival (months), ► (ongoing) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regimen | Agent | BOR | Overall | Intracranial | ||

| 1 | 1 | Alectinib | PR | PR | No metastases |

► ► |

| 2 | Carboplatin | PR | ||||

| 2 | Bevacizumab | PR | ||||

| 2 | Pemetrexed | PR | ||||

| 2 | 1 | Cisplatin | NA a | PR | No metastases |

► ► |

| 1 | Pemetrexed | NA a | ||||

| 2 | Alectinib | PR | ||||

| 3 | Cisplatin | Unknown | ||||

| 3 | Pemetrexed | Unknown | ||||

| 3 | 1 | Bevacizumab | SD | CR | No metastases |

|

| 1 | Paclitaxel | SD | ||||

| 1 | Irinotecan | SD | ||||

| 2 | Alectinib | PR | ||||

| 4 | 1 | Cisplatin | PR | SD | No metastases |

|

| 1 | TS‐1 | PR | ||||

| 2 | Alectinib | PR | ||||

| 5 | 1 | Alectinib | SD | SD | No metastases |

|

| 2 | Cisplatin | PR | ||||

| 2 | Pemetrexed | PR | ||||

| 6 | 1 | Carboplatin | NA a | SD | No metastases |

|

| 1 | Paclitaxel | NA a | ||||

| 1 | Fluorouracil | NA a | ||||

| 2 | Bevacizumab | Unknown | ||||

| 2 | Carboplatin | Unknown | ||||

| 2 | Pemetrexed | Unknown | ||||

| 3 | Alectinib | PR | ||||

| 7 | 1 | Alectinib | PR | PD | No metastases |

|

Abbreviations: BOR, best overall response; CR, confirmed response; NA, not available; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response, SD, stable disease/no response.

Adjuvant therapy only.

3.3.5. Patients who received two or three prior anaplastic lymphoma kinase tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EXP4‐5)

Of 17 Japanese patients in EXP4‐5, an OR was observed in 8 (ORR = 47.1%; 95% CI 23.0‐72.2), a CR in 1 (5.9%), a PR in 7 (41.2%) and SD in 6 (35.3%) (Table 2). At the time of analysis, the median DOR was 9.9 months (95% CI 4.2–NE) (Table 3). Of 12 Japanese patients with measurable baseline CNS lesions as per ICR (8 had received prior crizotinib and alectinib, 3 had received prior crizotinib and ceritinib, and 1 had received prior crizotinib, alectinib and ceritinib), an intracranial OR was observed in 5 patients (ORR = 41.7%; 95% CI 15.2‐72.3), a CR in 4 (33.3%), a PR in 1 (8.3%) and SD in 6 (50.0%) (Table 3). At the time of analysis, the median intracranial DOR was 15.0 months (95% CI 6.9–NE) (Table 3). Median PFS was 8.4 months (95% CI 3.9‐11.3) among Japanese patients and was 6.9 months (95% CI 5.4‐9.5) among all patients (Figure 2).

3.4. Patient‐reported outcomes

The global quality of life score improved or remained stable in 73.3% of Japanese patients. Functional, general symptom and lung cancer‐specific symptom scores improved or remained stable in 70.0‐96.7%, 73.3‐96.7% and 56.7‐100%, respectively (Table 5).

Table 5.

Change in EORTC (QLQ‐C30 and QLQ‐LC13) scales among Japanese patients in the PRO‐evaluable analysis set

| Pooled EXP2‐5: ≥1 prior ALK TKI ± CT (N = 30) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Improved | Stable | Worsening | |

| Global QoL (QLQ‐C30) | |||

| Global QoL | 10 (33.3) | 12 (40.0) | 8 (26.7) |

| Functional scales (QLQ‐C30) | |||

| Physical | 9 (30.0) | 18 (60.0) | 3 (10.0) |

| Role | 5 (16.7) | 16 (53.3) | 9 (30.0) |

| Emotional | 9 (30.0) | 20 (66.7) | 1 (3.3) |

| Cognitive | 7 (23.3) | 18 (60.0) | 5 (16.7) |

| Social | 13 (43.3) | 16 (53.3) | 1 (3.3) |

| Symptom scales/items (QLQ‐C30) | |||

| Fatigue | 13 (43.3) | 15 (50.0) | 2 (6.7) |

| Nausea and vomiting | 6 (20.0) | 23 (76.7) | 1 (3.3) |

| Pain | 9 (30.0) | 15 (50.0) | 6 (20.0) |

| Dyspnea | 8 (26.7) | 18 (60.0) | 4 (13.3) |

| Insomnia | 13 (43.3) | 12 (40.0) | 5 (16.7) |

| Appetite loss | 13 (43.3) | 16 (53.3) | 1 (3∙3) |

| Constipation | 5 (16.7) | 21 (70.0) | 4 (13.3) |

| Diarrhea | 3 (10.0) | 19 (63.3) | 8 (26.7) |

| Financial difficulties | 8 (26.7) | 21 (70.0) | 1 (3.3) |

| Symptom scales/items (QLQ‐LC13) | |||

| Dyspnea | 4 (13.3) | 22 (73.3) | 4 (13.3) |

| Cough | 10 (33.3) | 18 (60.0) | 2 (6.7) |

| Hemoptysis | 8 (26.7) | 22 (73.3) | 0 |

| Sore mouth | 1 (3.3) | 20 (66.7) | 9 (30.0) |

| Dysphagia | 3 (10.0) | 26 (86.7) | 1 (3.3) |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 4 (13.3) | 13 (43.3) | 13 (43.3) |

| Alopecia | 1 (3.3) | 23 (76.7) | 6 (20.0) |

| Pain in chest | 5 (16.7) | 20 (66.7) | 5 (16.7) |

| Pain in arm or shoulder | 10 (33.3) | 15 (50.0) | 5 (16.7) |

| Pain in other parts | 10 (33.3) | 11 (36.7) | 9 (30.0) |

Data are n (%). For functioning and global QoL, “improved” was defined as a ≥10‐point increase from baseline and “worsening” was defined as a ≥10‐point decrease from baseline. “Stable” was defined as a patient who neither improved nor worsened. For symptoms, “improved” was defined as a ≥10‐point decrease from baseline and “worsening” was defined as a ≥10‐point increase from baseline. “Stable” was defined as a patient who neither improved nor worsened.

Abbreviations: ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; CT, chemotherapy; EORTC, European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer; EXP, expansion cohort; PRO, patient‐reported outcomes; QLQ‐C30, Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30; QLQ‐LC13, Quality of Life Questionnaire Lung Cancer Module; QoL, quality of life; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

3.5. Pharmacokinetics

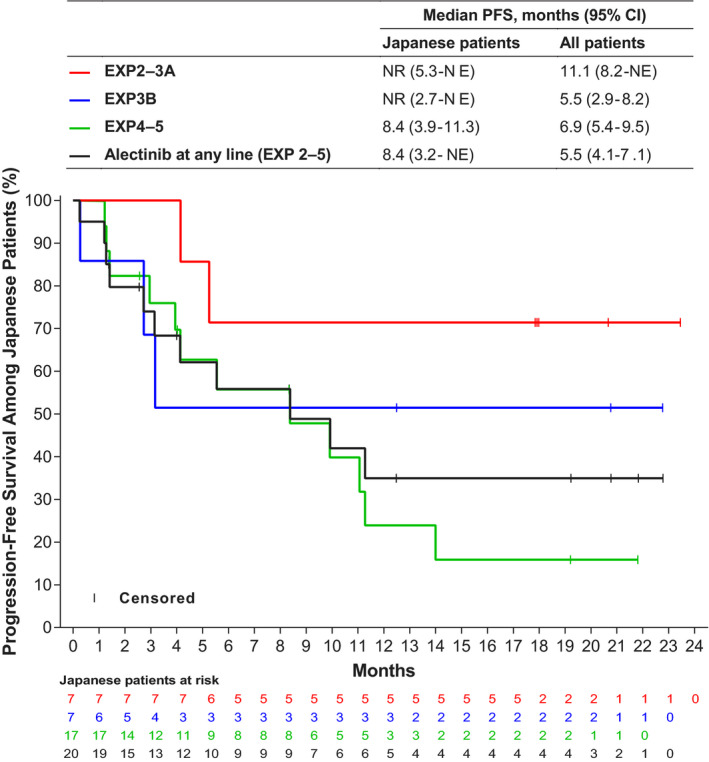

The median concentration‐time profiles following administration of single‐dose or multiple‐dose lorlatinib 100 mg QD were similar between Japanese and non–Japanese patients (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Median plasma lorlatinib concentration‐time plot against nominal time post–dose stratified by Japanese vs non–Japanese patients. A, Single‐dose lorlatinib 100 mg day 7 lead‐in. B, Multiple‐dose lorlatinib 100 mg QD cycle 1, day 15. QD, once per day

4. DISCUSSION

The safety and efficacy of lorlatinib in the Japanese subpopulation was comparable to that in the overall population. Lorlatinib demonstrated clinically meaningful responses in ALK‐rearranged Japanese patients who had received ≥1 prior ALK TKI, including among patients who had received crizotinib alone or whose last prior ALK TKI was alectinib. Given that CNS progression remains a clinically significant problem in ALK‐rearranged NSCLC, 19 , 23 , 38 , 39 it is encouraging that lorlatinib exhibited robust and clinically meaningful intracranial activity, including a number of complete intracranial responses, in ALK‐rearranged Japanese patients irrespective of prior lines of therapy.

Crizotinib was widely used as first‐line treatment in the United States until 2018, when National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines listed alectinib as the preferred, and crizotinib as an alternate, first‐line ALK TKI for patients with ALK‐rearranged NSCLC. 40 In Japan, however, alectinib has been used as the first‐line ALK TKI for patients with ALK‐rearranged NSCLC for a longer period, due to Japan being the first country to approve alectinib in May 2014. 25 In addition, the J‐ALEX trial has demonstrated improved PFS with alectinib versus crizotinib among ALK TKI‐naïve Japanese patients in this setting, 27 and it is recommended by the Japanese Lung Cancer Society Guideline for NSCLC, stage IV. 28

The findings in the current study of clinically meaningful responses among Japanese patients receiving first‐line or second‐line alectinib are, therefore, of relevance for clinical practice in this geographical region, as well as globally with the increasing use of alectinib as a first‐line therapy outside of Japan. Lorlatinib demonstrated clinically meaningful responses in ALK‐rearranged Japanese patients who received alectinib as their last ALK TKI or as their sole prior ALK TKI (Table 3). Three of these seven patients who received alectinib as their sole prior ALK TKI showed responses over 6 months. In addition, lorlatinib showed clinically meaningful IC responses among 12 patients previously treated with crizotinib and at least one other second generation ALK TKI (alectinib, ceritinib, or both). Whether these responses represent improved clinical outcomes versus platinum‐containing chemotherapy requires further prospective investigation.

The safety and tolerability of lorlatinib in the Japanese subpopulation was comparable to that in the overall population. The frequency of permanent discontinuation due TRAE was low in both the Japanese (2.6%) and overall (3.3%) populations. The most common TRAE were hypercholesterolemia and hypertriglyceridemia, which occurred at a similar frequency in the Japanese and overall populations. These events emerged after approximately 2 weeks of lorlatinib therapy were reported as grade 1 or 2 in the majority of patients and were manageable with lipid‐lowering agents and/or dosage reductions. Cognitive effects were generally mild (all reported as grade 1 or 2) and were manageable with dose reduction or dose interruption. The single‐dose and multiple‐dose pharmacokinetic profile of lorlatinib was comparable between Japanese and non–Japanese patients.

The limitation of this subanalysis was the small number of patients, especially in the EXP2‐3A and EXP3B cohorts.

In conclusion, lorlatinib showed clinically meaningful responses and IC responses among Japanese patients with ALK‐rearranged NSCLC who received ≥1 prior ALK TKI, including meaningful responses among those receiving prior alectinib only. Lorlatinib was generally well tolerated, with a similar AE profile among Japanese patients to that among the overall population.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Takashi Seto reports research funding during the conduct of the study from Abbvie, AstraZeneca, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly Japan, Kissei Pharmaceutical, LOXO Oncology, MSD, Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis Pharma, Pfizer Japan and Takeda Pharmaceutical; lecture fees and honoraria from AstraZeneca, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly Japan, MSD, Pfizer Japan and Taiho Pharmaceutical; and employment by Precision Medicine Asia. Hidetoshi Hayashi has received honoraria from AstraZeneca, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly Japan, MSD, Ono Pharmaceutical, Pfizer Japan, Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis Pharma, Merck Serono and Taiho Pharmaceutical; and research funding from AbbVie, AC MEDICAL, Astellas Pharma, AstraZeneca, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Daiichi‐Sankyo, Eisai, Eli Lilly Japan, EPS Associates, GlaxoSmithKline, Japan Clinical Research Operations, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Merck Serono, MSD, Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis Pharma, Ono Pharmaceutical, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, PAREXEL International, Pfizer Japan, PPD‐SNBL, Quintiles Transnational Japan, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Takeda Pharmaceutical and Yakult Honsha. Miyako Satouchi has received lecture fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Chugai, Eli Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Ono, Pfizer Japan and Taiho; and research funding for his institution from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Chugai, MSD, Pfizer Japan and Takeda. Yasushi Goto has received honoraria for consulting or advisory roles from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chugai, Daiichi‐Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Glaxo Smith Kline, Guardant Health, Kyorin, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer and Taiho Pharmaceutical; for speaker’s bureaus from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Chugai, Eli Lilly, MSD, Novartis Research, Ono Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Shionogi Pharma and Taiho Pharmaceutical; and has received institutional research funding from AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Chugai, Daiichi‐Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Guardant Health, Kyorin, Novartis, Ono Pharmaceutical, Pfizer and Taiho Pharmaceutical. Seiji Niho has received grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, MSD and Pfizer; personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Chugai, Novartis, Shionogi, Taiho and Yakult; and research grants from Merck Serono. Naoyuki Nogami has received honoraria from AstraZeneca, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly Japan, Kyowa Kirin, ONO Pharmaceutical, Pfizer Japan and Taiho Pharmaceutical. Toyoaki Hida has received grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly, Kissei, MSD, Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Ono Pharmaceutical, Pfizer and Taiho Pharmaceutical; and grants from AbbVie, Daiichi‐Sankyo, Eisai, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Merck Serono and Takeda Pharmaceutical. Toshiaki Takahashi has received grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly Japan, MSD, ONO Pharmaceutical and Pfizer Japan; and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim Japan and Roche Diagnostics. Masahiro Morise has received lecture fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Chugai, Eli Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Ono, Pfizer Japan and Taiho; and institutional research funding from Boehringer Ingelheim and Eli Lilly. Takashi Nagasawa, Mie Suzuki, Masayuki Ohkura, Kei Fukuhara, Holger Thurm and Gerson Peltz are employees of and stockholders in Pfizer. Makoto Nishio has received grants and non–financial support from F. Hoffmann‐La Roche; grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Ono Pharmaceutical, Pfizer and Taiho Pharmaceutical; fees from Merck Serono and Taiho Pharmaceutical; and grants from Astellas.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS STATEMENT

The institutional review board or independent ethics committee at each participating centre approved the protocol, which complied with the International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects, Good Clinical Practice guidelines, the Declaration of Helsinki, and local laws. All patients provided written, informed consent before participation.

Supporting information

Fig S1

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all the patients and their families as well as all study investigators, research coordinators, and staff at each investigational site. We thank Masakazu Matsumura of Pfizer R&D Japan for editorial assistance. This study was sponsored by Pfizer. Medical writing support was provided by Julian Martins, of Science Communications, Springer Healthcare (Paris, France), which was funded by Pfizer.

Seto T, Hayashi H, Satouchi M, et al. Lorlatinib in previously treated anaplastic lymphoma kinase‐rearranged non–small cell lung cancer: Japanese subgroup analysis of a global study. Cancer Sci. 2020;111:3726–3738. 10.1111/cas.14576

REFERENCES

- 1. Rikova K, Guo A, Zeng Q, et al. Global survey of phosphotyrosine signaling identifies oncogenic kinases in lung cancer. Cell. 2007;131:1190‐1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Koivunen JP, Mermel C, Zejnullahu K, et al. EML4‐ALK fusion gene and efficacy of an ALK kinase inhibitor in lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4275‐4283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Solomon B, Varella‐Garcia M, Camidge DR. ALK gene rearrangements: a new therapeutic target in a molecularly defined subset of non–small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:1450‐1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McDermott U, Iafrate AJ, Gray NS, et al. Genomic alterations of anaplastic lymphoma kinase may sensitize tumors to anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3389‐3395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. US Food and Drug Administration . Crizotinib US prescribing information. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/202570s011lbl.pdf. Accessed October 15, 2019

- 6. European Medicines Agency . Crizotinib EU prescribing information. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_‐_Product_Information/human/002489/WC500134759.pdf. Accessed October 15, 2019

- 7. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency . Report on the deliberation results (crizotinib). March, 2012. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000153949.pdf. Accessed October 15, 2019

- 8. Costa DB, Kobayashi S, Pandya SS, et al. CSF concentration of the anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibitor crizotinib. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:e443‐e445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shaw AT, Kim DW, Nakagawa K, et al. Crizotinib versus chemotherapy in advanced ALK‐positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2385‐2394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Petrelli F, Lazzari C, Ardito R, et al. Efficacy of ALK inhibitors on NSCLC brain metastases: A systematic review and pooled analysis of 21 studies. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0201425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Friboulet L, Li N, Katayama R, et al. The ALK inhibitor ceritinib overcomes crizotinib resistance in non–small cell lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:662‐673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kodama T, Tsukaguchi T, Yoshida M, Kondoh O, Sakamoto H. Selective ALK inhibitor alectinib with potent antitumor activity in models of crizotinib resistance. Cancer Lett. 2014;351:215‐221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Crino L, Ahn MJ, De Marinis F, et al. Multicenter phase II study of whole‐body and intracranial activity with ceritinib in patients with ALK‐rearranged non–small‐cell lung cancer previously treated with chemotherapy and crizotinib: results from ASCEND‐2. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2866‐2873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gadgeel SM, Gandhi L, Riely GJ, et al. Safety and activity of alectinib against systemic disease and brain metastases in patients with crizotinib‐resistant ALK‐rearranged non–small‐cell lung cancer (AF‐002JG): results from the dose‐finding portion of a phase 1/2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1119‐1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim D‐W, Mehra R, Tan DSW, et al. Activity and safety of ceritinib in patients with ALK‐rearranged non–small‐cell lung cancer (ASCEND‐1): updated results from the multicentre, open‐label, phase 1 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:452‐463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Novello S, Mazières J, Oh I‐J, et al. Alectinib versus chemotherapy in crizotinib‐pretreated anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)‐positive non–small‐cell lung cancer: results from the phase III ALUR study. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:1409‐1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Novello S, Mazieres J, Oh I‐J, et al. Primary results from the phase III ALUR study of alectinib versus chemotherapy in previously treated ALK+ non–small‐cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [abstract 1299O_PR]. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:1409‐1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ou SH, Ahn JS, De Petris L, et al. Alectinib in crizotinib‐refractory ALK‐rearranged non–small‐cell lung cancer: a phase II global study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:661‐668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Peters S, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, et al. Alectinib versus crizotinib in untreated ALK‐positive non–small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:829‐838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shaw AT, Gandhi L, Gadgeel S, et al. Alectinib in ALK‐positive, crizotinib‐resistant, non–small‐cell lung cancer: a single‐group, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:234‐242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shaw AT, Kim DW, Mehra R, et al. Ceritinib in ALK‐rearranged non–small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1189‐1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shaw AT, Kim TM, Crinò L, et al. Ceritinib versus chemotherapy in patients with ALK‐rearranged non–small‐cell lung cancer previously given chemotherapy and crizotinib (ASCEND‐5): a randomised, controlled, open‐label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:874‐886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Soria J‐C, Tan DSW, Chiari R, et al. First‐line ceritinib versus platinum‐based chemotherapy in advanced ALK‐rearranged non–small‐cell lung cancer (ASCEND‐4): a randomised, open‐label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2017;389:917‐929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yang J‐H, Ou S‐H, De Petris L, et al. Pooled systemic efficacy and safety data from the pivotal phase II studies (NP28673 and NP28761) of alectinib in ALK‐positive non–small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12:1552‐1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency . Report on the deliberation results (alectinib). June, 2014. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000208811.pdf. Accessed October 15, 2019

- 26. Seto T, Kiura K, Nishio M, et al. CH5424802 (RO5424802) for patients with ALK‐rearranged advanced non–small‐cell lung cancer (AF‐001JP study): a single‐arm, open‐label, phase 1–2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:590‐598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hida T, Nokihara H, Kondo M, et al. Alectinib versus crizotinib in patients with ALK‐positive non–small‐cell lung cancer (J‐ALEX): an open‐label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;390:29‐39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Akamatsu H, Ninomiya K, Kenmotsu H, et al. The Japanese Lung Cancer Society Guideline for non–small cell lung cancer, stage IV. Int J Clin Oncol. 2019;24:731‐770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gainor JF, Dardaei L, Yoda S, et al. Molecular mechanisms of resistance to first‐ and second‐generation ALK inhibitors in ALK‐rearranged lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2016;6:1118‐1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Johnson TW, Richardson PF, Bailey S, et al. Discovery of (10R)‐7‐amino‐12‐fluoro‐2,10,16‐trimethyl‐15‐oxo‐10,15,16,17‐tetrahydro‐2H‐8,4‐(m etheno)pyrazolo[4,3‐h][2,5,11]‐benzoxadiazacyclotetradecine‐3‐carbonitrile (PF‐06463922), a macrocyclic inhibitor of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) and c‐ros oncogene 1 (ROS1) with preclinical brain exposure and broad‐spectrum potency against ALK‐resistant mutations. J Med Chem. 2014;57:4720‐4744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shaw AT, Felip E, Bauer TM, et al. Lorlatinib in non–small‐cell lung cancer with ALK or ROS1 rearrangement: an international, multicentre, open‐label, single‐arm first‐in‐man phase 1 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1590‐1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Solomon BJ, Besse B, Bauer TM, et al. Lorlatinib in patients with ALK‐positive non–small‐cell lung cancer: results from a global phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:1654‐1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency . Report on the deliberation results (lorlatinib). September, 2018. http://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000228981.pdf. Accessed October 15, 2019.

- 34. US Food and Drug Administration . Lorlatinib US prescribing information. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/210868s000lbl.pdf. Accessed October 15, 2019

- 35. European Medicines Agency . Lorlatinib EU prescribing information. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product‐information/lorviqua‐epar‐product‐information_en.pdf. Accessed October 15, 2019

- 36. US Food and Drug Administration . Alectinib US prescribing information. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/208434s004lbl.pdf. Accessed January 1, 2020

- 37. European Medicines Agency . Alectinib EU prescribing information. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product‐information/alecensa‐epar‐product‐information_en.pdf. Accessed October 15, 2019.

- 38. Camidge DR, Kim HR, Ahn MJ, et al. Brigatinib versus crizotinib in ALK‐positive non–small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2027‐2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Solomon BJ, Mok T, Kim DW, et al. First‐line crizotinib versus chemotherapy in ALK‐positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2167‐2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kuznar W.Updated NCCN guidelines expand targeted therapy options for patients with metastatic NSCLC. http://oncpracticemanagement.com/issues/2018/july‐2018‐vol‐8‐no‐7/613‐updated‐nccn‐guidelines‐expand‐targeted‐therapy‐options‐for‐patients‐with‐metastatic‐nsclc. Accessed February 5, 2019

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig S1

Supplementary Material