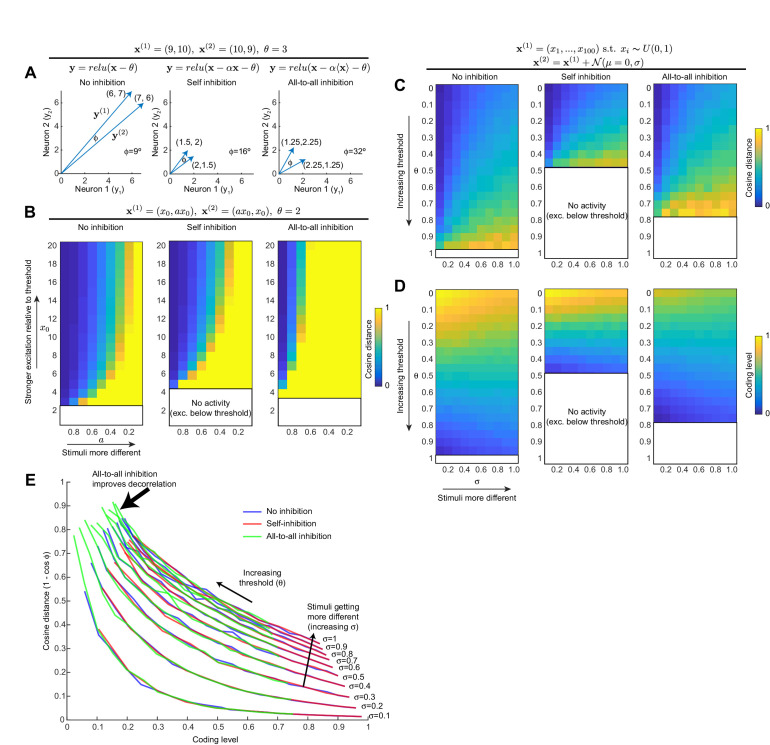

Appendix 1—figure 1. All-to-all inhibition decorrelates population activity better than self-inhibition.

(A) For a toy example of two neurons and two stimuli, self-inhibition improves the stimulus separation (i.e, increases angle between the two stimulus vectors) by bringing activity down closer to spiking threshold, but all-to-all inhibition improves the separation more. Note that to simplify the model, we model the inhibitory interneuron as being activated by the principal neurons' dendrites, as occurs with Kenyon cells and APL. (B) Generalization of result in (A) to wider activity range in the two neurons. Heat maps show cosine distance for different values of and a (increasing means more excitation; decreasing a means the stimuli are more different). The self-inhibition panel is the same as the no-inhibition panel, just stretched vertically (i.e., self-inhibition acts as gain control), whereas the all-to-all inhibition panel expands the range of high cosine distances toward more similar stimulus pairs. Blank areas mean the activity is zero because excitation is below threshold, so cosine distance is undefined. (C) Generalization of (A,B) to population of 100 neurons. Stimulus 1 is sampled from a uniform distribution over (0, 1). Stimulus 2 is Stimulus 1 plus Gaussian noise (magnitude of noise governed by σ; higher σ means the two stimuli are more different). Heat maps show cosine distance for different thresholds (θ) and σ averaged over 100 trials. (D) Coding level (fraction of active neurons) for different thresholds and σ as in (C); note how decreasing coding level (increased sparseness) correlates with higher cosine distance. (E) Each curve is one column (one value of σ) from the heat maps in (C) and (D), showing how cosine distance improves with lower coding levels. Adding inhibition does not change this curve; it merely shifts the model to different points along the curve. All-to-all inhibition achieves higher cosine distance (more decorrelated activity) than self-inhibition or no inhibition.