Abstract

Heterozygous, loss-of-function mutations in the granulin gene (GRN) encoding progranulin (PGRN) are a common cause of frontotemporal dementia (FTD). Homozygous GRN mutations cause neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis-11 (CLN11), a lysosome storage disease. PGRN is a secreted glycoprotein that can be proteolytically cleaved into seven bioactive 6 kDa granulins. However, it is unclear how deficiency of PGRN and granulins causes neurodegeneration. To gain insight into the mechanisms of FTD pathogenesis, we utilized Tandem Mass Tag isobaric labeling mass spectrometry to perform an unbiased quantitative proteomic analysis of whole-brain tissue from wild type (Grn+/+) and Grn knockout (Grn−/−) mice at 3- and 19-months of age. At 3-months lysosomal proteins (i.e. Gns, Scarb2, Hexb) are selectively increased indicating lysosomal dysfunction is an early consequence of PGRN deficiency. Additionally, proteins involved in lipid metabolism (Acly, Apoc3, Asah1, Gpld1, Ppt1, and Naaa) are decreased; suggesting lysosomal degradation of lipids may be impaired in the Grn−/− brain. Systems biology using weighted correlation network analysis (WGCNA) of the Grn−/− brain proteome identified 26 modules of highly co-expressed proteins. Three modules strongly correlated to Grn deficiency and were enriched with lysosomal proteins (Gpnmb, CtsD, CtsZ, and Tpp1) and inflammatory proteins (Lgals3, GFAP, CD44, S100a, and C1qa). We find that lysosomal dysregulation is exacerbated with age in the Grn−/− mouse brain leading to neuroinflammation, synaptic loss, and decreased markers of oligodendrocytes, myelin, and neurons. In particular, GPNMB and LGALS3 (galectin-3) were upregulated by microglia and elevated in FTD-GRN brain samples, indicating common pathogenic pathways are dysregulated in human FTD cases and Grn−/− mice. GPNMB levels were significantly increased in the cerebrospinal fluid of FTD-GRN patients, but not in MAPT or C9orf72 carriers, suggesting GPNMB could be a biomarker specific to FTD-GRN to monitor disease onset, progression, and drug response. Our findings support the idea that insufficiency of PGRN and granulins in humans causes neurodegeneration through lysosomal dysfunction, defects in autophagy, and neuroinflammation, which could be targeted to develop effective therapies.

Keywords: Progranulin (PGRN), Frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD), Frontotemporal dementia (FTD), Neurodegeneration, Lysosome, Inflammation, Proteomics, GPNMB, Galectin-3

Background

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) is the most common cause of dementia in people under the age of 60 [7]. Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is the clinical manifestation of FTLD neuropathology and major clinical symptoms can be divided into either progressive deficits in executive function and behavior or language [26]. Importantly, ~ 30% of FTD patients have a familial history of FTD or related neurodegenerative disease, highlighting the important role of genetics in disease pathogenesis [26, 39, 43]. Taken together autosomal dominant mutations in three genes, progranulin (GRN), chromosome 9 open reading frame 72 (C9orf72), and microtubule associated protein tau (MAPT), account for the majority of FTD heritability [43]. Less common mutations in other genes encoding TAR DNA binding protein 43 (TDP-43; TARDBP) [19, 32, 95], sequestosome-1/p62 (SQSTM1) [67, 121], charged multi-vesicular body protein 2b (CHMP2B) [104, 120], valosin-containing protein (VCP) [45, 126], TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) [33, 38, 92], among other rare genes can cause FTD [44]. Despite these advances in understanding the genetic causes of FTD, the normal, physiologic function of many proteins encoded by genes mutated in FTD is still unclear. Understanding the function and dysfunction of proteins linked to FTD is critical to developing effective therapies.

In particular, the function of the progranulin (PGRN) protein, encoded by GRN, has remained an enigma. The PGRN protein family is over a billion years old and evolutionarily conserved across many species, suggesting PGRN has a critical function [85]. Heterozygous GRN mutations cause FTD by decreasing PGRN mRNA and protein by 50% or more [6, 24, 31, 36, 57, 73]. Although FTD-GRN mutations lead to TDP-43 pathology and dysfunction [17, 23, 81], it is still unclear why deficiency of PGRN ultimately causes neurodegeneration.

PGRN is a pleiotropic, cysteine rich secreted protein composed of one half-length and seven full-length domain repeats called granulins that are connected by peptide linker regions [112]. PGRN is highly expressed in neuronal and microglial cells throughout the brain [88]. PGRN has been implicated in various physiological functions, ranging from extracellular signaling through membrane receptors [25, 76, 80, 129], neuroprotection [35, 65, 117, 130], to modulating inflammation [21, 70, 137]. PGRN can be cleaved by a variety of proteases to release individual ~ 6-kDa granulins, which are also bioactive [8, 47, 137]. However, the precise functions of PGRN and granulins are unclear, and the pathways that lead from deficiency of PGRN and granulins to FTD are still unknown, which has impeded progress towards developing therapies for FTD-GRN.

Another roadblock in the development of therapies for FTD is a lack of specific and sensitive biomarkers [40]. The identification of reliable biomarkers is important to distinguish FTD from Alzheimer's disease or other neurodegenerative diseases. Importantly, appropriate biomarkers are also useful to monitor disease progression and assess efficacy of potential drugs. Elevated levels of neurofilament light chain (Nfl) in CSF and plasma are one promising biomarker for symptomatic FTD patients that harbor mutations in GRN, C9orf72, or MAPT [58]. However, increased levels of Nfl in plasma or CSF are not specific to FTD and Nfl is increased in several other neurodegenerative diseases [124]. More research is needed to identify novel biomarkers to diagnose, discriminate, and ultimately treat the different sub-types of FTD.

To investigate the function of PGRN, provide insight into FTD pathogenesis, and identify potential biomarkers, we performed an unbiased quantitative proteomics analysis of whole-brain tissue from wild type (Grn+/+) and Grn knockout (Grn−/−) mice at 3- and 19-months of age. We utilized the Grn−/− mouse model because they share many pathological features with human FTD-GRN, including microgliosis, lipofuscinosis, accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins, and behavioral impairment [1, 82, 96]. We identified a variety of proteins that were increased or decreased in the Grn−/− mouse brain proteome that were subsequently validated using biochemical and immunohistological approaches. In particular, lysosomal proteins were the most significantly altered in young Grn−/− mice, indicating that lysosomal dysfunction is an early event when PGRN expression is lost. In addition, we identified two proteins, transmembrane glycoprotein NMB (GPNMB) and galectin-3, which are predominantly expressed in microglia and are key hubs of a larger network of dysregulated proteins that change with age in Grn−/− mice. Moreover, GPNMB and galectin-3 were significantly elevated in the lysates of FTD-GRN brain samples compared to healthy controls. Together, these data suggest that common pathogenic pathways are dysregulated in both Grn−/− mice and human FTD cases caused by GRN haploinsufficiency.

Methods

Mouse brain sample processing for proteomics and biochemical analysis

Grn−/− mice used in this study were originally generated in Dr. Aihao Ding’s laboratory [131, 132] and purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (B6(Cg)-Grntm1.1Aidi/, IMSR Cat# JAX:013175, RRID:IMSR_JAX:013175). Mice were housed in the Department of Animal Resources at Emory University and all work was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. Mice were sacrificed at various ages and whole brains were dissected from the skull and frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen. Brain tissue was ground to a fine powder under liquid nitrogen using a mortar and pestle and stored at − 80 °C as previously described [48]. Frozen cerebral cortex brain samples from 3-month old Grn+/+ wild type (n = 4) and Grn−/− knock out (n = 4) mice and 19-month old Grn+/+ wild type (n = 4) and Grn−/− knock out (n = 4) mice were collected. For proteomic analysis, approximately 100 mg of mouse brain tissue powder was homogenized in 500 μL of urea lysis buffer (8 M urea, 100 mM NaH2PO4, pH 8.5), supplemented with 5 μL (100 × stock) HALT protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Pierce) using a Bullet Blender (Next Advance) and 750 mg of steel beads (Next Advance). Protein supernatants were then transferred to a new 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube and sonicated (Sonic Dismembrator, Fisher Scientific) 3 times for 5 s with 15 s intervals of rest at 30% amplitude. Protein concentration was measured with the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay, and samples were frozen in aliquots at − 80 °C. Protein integrity was checked by one-dimensional SDS-PAGE. For subsequent immunoblots or ELISAs, an equal weight of brain powder was homogenized with 6 × volume per weight in cytoplasmic extraction buffer (CEB), membrane extraction buffer (MEB) from a Subcellular Fractionation kit (Pierce), or with 10 × volume per weight in RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton-X 100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0), supplemented with 1 × HALT protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (UK286007, Thermo scientific) as previously described [47]. Brain powder suspensions were sonicated (Sonic Dismembrator, Fisher Scientific) 5 times for 2 s with 8 s intervals of rest at 30% amplitude. Brain lysates were obtained by centrifugation at 500 × rcf for 10 min at 4 °C. Protein supernatants were transferred to a new 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube. Protein concentration was measured with the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay and saved samples were saved at − 80 °C.

Tandem mass tag (TMT) peptide labeling and electrostatic repulsion-hydrophilic interaction chromatography (ERLIC) fractionation

Proteolytic digestion of protein samples and cleanup was performed as previously described [14]. Briefly, protein samples were reduced with 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) for 30 min, alkylated with 5 mM iodoacetamide (IAA) in the dark for an additional 30 min and then diluted 8-fold with 50 mM triethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB). Overnight digestion was performed with 1:100 (w/w) Lysyl endopeptidase (Wako) followed by an additional 12-h digestion with Trypsin at 1:50 (w/w). Peptide solutions were acidified and desalted with a C18 Sep-Pak column (Waters). A 2 μg equivalent of each sample elution was pooled and used to create a global internal standard (GIS) and all samples were dried under vacuum. Tandem mass tag (TMT) peptide labeling was performed according to manufacturer’s instructions and as previously described [14]. One batch of 10-plex TMT kits (Thermo Fisher) was used to label 8 samples and two GIS mixtures per batch. Electrostatic repulsion-hydrophilic interaction chromatography (ERLIC) offline fractionation was performed as previously described [14, 15]. Briefly, dried samples were re-suspended in 100 μL of ERLIC buffer A (90% acetonitrile with 0.1% acetic acid) and separated on a PolyWAX LP column (20 cm by 3.2 mm packed with 300 Å pore, 5 μm beads (PolyLC Inc.) and elution fractions were recovered over a 45-min gradient from 0 to 50% ERLIC buffer B (30% ACN with 0.1% FA).

LC–MS/MS and TMT data acquisition

Assuming equal distribution of peptide concentration across all ERLIC fractions, 10 μL of loading buffer (0.1% TFA) was added to each of the fractions and 2 μL was separated on a 25 cm long 75 μm internal diameter fused silica column (New Objective, Woburn, MA) packed in-house with 1.9 μm Reprosil-Pur C18-AQ resin. The LC–MS/MS platform consisted of a Dionex RSLCnano UPLC coupled to an Orbitrap Fusion mass spectrometer with a Flex nano-electrospray ion source (Thermo Fisher). Sample elution was performed over a gradient of 3 to 30% Buffer B (0.1% formic acid in ACN) over 105 min (flow rate started at 300 nL/min and ended at 350 nL/min), from 30 to 60% B over 20 min at 350 nL/min, and from 60 to 99% B over 5 min at 350 nL/min. The column was equilibrated with 1% B for 10 min at a flow rate that increased from 350 nL/min to 400 nL/min. The MS was operated in positive ion mode and utilized the synchronous precursor selection (SPS)-MS3 method for reporter ion quantitation as described [90]. The full scan range was 380–1500 m/z at a nominal resolution of 120,000 at 200 m/z and automatic gain control (AGC) set to 2 × 105. Collision-induced dissociation (CID)-Tandem MS/MS at 35% normalized collision energy (CE) and higher energy collision dissociation (HCD) SPS-MS3 at 65% normalized collision energy (CE) were collected at top speed with 3 s cycles. For SPS, the top 10 product ions were notched and fragmented.

Protein identification and quantification

Raw data files from the Orbitrap Fusion were processed using Proteome Discover (version 2.1). Collected MS/MS spectra were searched against the UniProt mouse proteome database (54,489 total sequences). SEQUEST parameters were specified as: trypsin enzyme, two missed cleavages allowed, minimum peptide length of 6, TMT tags on lysine residues and peptide N-termini (+ 229.162932 Da) and carbamidomethylation of cysteine residues (+ 57.02146 Da) as fixed modifications, oxidation of methionine residues (+ 15.99492 Da) and deamidation of asparagine and glutamine (+ 0.984016 Da) as a variable modification, precursor mass tolerance of 20 ppm, and a fragment mass tolerance of 0.6 Da. Peptide spectral match (PSM) error rates were determined using the target-decoy strategy coupled to Percolator [16] modeling of true and false matches. Reporter ions were quantified from MS3 scans using an integration tolerance of 20 ppm with the most confident centroid setting. An MS2 spectral assignment false discovery rate (FDR) of less than 1% was achieved by applying the target-decoy strategy. Following spectral assignment, peptides were assembled into proteins and were further filtered based on the combined probabilities of their constituent peptides to a final FDR of 1%. In cases of redundancy, shared peptides were assigned to the protein sequence with the most matching peptides, thus adhering to principles of parsimony. In total, 8695 proteins were identified by tandem mass spectrometry. The search results and TMT quantification as well as raw LC–MS/MS files are included in the ProteomeXchange online repository with identifier (to be uploaded and assigned). Prior to data analysis, preliminary network connectivity outliers were determined as samples with connectivity beyond 3 standard deviations from the mean using Oldham's “SampleNetworks” v1.06 R script as previously published, but no cases were identified for removal [84, 102].

Data preparation

Each TMT batch consisted of a single age group, either 3 month or 19 month, of Grn+/+ and Grn−/− mice which led to some proteins being measured in one batch and not in the other. As a result, batch wise missing values for these proteins across the two TMT multiplexes led to exactly 50% missing values. To limit the effects of batch wise differences on data analysis methods, initial analysis was conducted on the 6566 unique proteins which were measured across all batches. Proteins with 50% of quantified values were later mapped into the existing network and volcano plots (2129 proteins).

Differential expression analysis and MetaScape

Differentially enriched or depleted proteins (p ≤ 0.05) were identified by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey HSD test comparing four groups: 3-month-old Grn+/+, 3-month-old Grn−/−, 19-month-old Grn+/+ mice and 19-month-old Grn−/− mice. Differential expression of proteins were visualized with volcano plots generated using the ggplot2 package in Microsoft R Open v3.4.2. Significantly differentially expressed proteins were determined by both having a p ≤ 0.05 and a fold change difference of greater than log2(1.25) or less than − log2(1.25) (a minimum 25% fold change).

Proteins that were significantly differentially expressed in Grn+/+ and Grn−/− mouse brain proteomes were analyzed using MetaScape as described [136]. Briefly, differentially expressed genes were analyzed using the MetaScape web portal (https://metascape.org/) to identify enriched ontology clusters in the data set. Statistically enriched terms (i.e. GO/KEGG terms), accumulative hypergeometric p-values, and enrichment factors were calculated and used for filtering. The significant terms were hierarchically clustered into a tree based on Kappa-statistical similarities among their gene memberships, then 0.3 kappa score applied as threshold to cast the tree into term clusters.

Weighed co-expression network analysis

Following previously described procedures of WGCNA [102], a weighted protein co-expression network was generated using the protein abundance network of 6566 unique proteins. WGCNA::blockwiseModules() function was used with the following settings: soft threshold power beta = 29, deepSplit = 4, minimum module size of 25, TOMdenom = “mean”, merge cut height of 0.07, pamStage = TRUE and a reassignment threshold of p < 0.05. Hierarchical protein correlation clustering analysis was conducted using 1‐TOM, and initial module identifications were established using dynamic tree cutting as implemented in the WGCNA::blockwiseModules() function [66]. Module eigenproteins were defined as the first principal component of coexpression module protein log2(abundances) [74]. The module membership measure is defined as kME. KME is the pearson correlation between the expression pattern of the protein and the module eigenprotein. Bicor correlation was used for pairwise complete correlation of non-missing measurements with the cognate samples’ levels in module eigenproteins. The top correlated eigenprotein was used to assign the proteins with 50% missing values to a module, albeit with diminished confidence due to N = 8 instead of 16.

Gene ontology (GO) and cell-type enrichment analysis

To characterize groups of differentially expressed proteins and co‐expressed proteins, we used GO Elite v1.2.5 as previously published [102] with pruned output visualized using an in‐house R script. Overrepresentation of ontologies in each module was determined by Z-score value. Enrichment of cell type across co‐expression modules was investigated by intersecting module proteins with lists of proteins known to be expressed by each cell marker [103] and assessing significance of overlap using a one‐tailed Fisher exact hypergeometric overlap test. After assessing significance, the p‐values were corrected by the Benjamini–Hochberg method. Cell type-specific gene lists are provided in Additional file 1: table S1.

Mouse plasma samples

Mouse blood samples were collected by cheek vein puncture into EDTA tubes and chilled on ice for 1 h. Plasma samples were separated by centrifugation at 500 rcf for 10 min at 4 °C and stored at − 80 °C for ELISA.

Human samples processing

Human brain samples

Human brain tissue was provided by the Emory Brain Tissue Bank (Emory University Goizueta Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, Atlanta, Georgia, USA) and the Mayo Clinic Brain Bank (Jacksonville, Florida). A summary of the neuropathological and clinical descriptors of human post-mortem samples used for immunostaining and ELISA is provided as a supplementary table (Additional File 2: table S2). This included a total of frozen frontal cortex samples from FTD-GRN patients (n = 21, 11 males and 10 females, mean age 66.81 ± 1.66 years), cognitively normal controls (n = 23, 13 males and 10 females, mean age 62.17 ± 2.51 years), among which 5 corresponding paraffin-embedded brain sections in each group were collected. Human brain tissue was processed as described for mouse brains described above. Briefly, an equal weight of brain powder was homogenized with 10 × volume per weight in RIPA buffer and saved for protein analysis (BCA), immunoblot, and ELISA.

Human CSF samples

Human cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples were obtained from the Advancing Research and Treatment for Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration (ARTFL) and the Longitudinal Evaluation of Familial Frontotemporal Dementia Subjects (LEFFTDS) studies (ARTFL-LEFFTDS), which were housed at the National Centralized Repository for Alzheimer Disease and Related Dementias (NCRAD). CSF was obtained by lumbar puncture from individuals with genetic mutations associated with FTD (FTD-GRN n = 13, FTD-C9orf72 n = 13, or FTD-MAPT n = 12) or cognitively normal controls (n = 14) and stored at − 80 °C before analysis. NCRAD receives government support under a cooperative agreement grant (U24 AG21886) awarded by the National Institute on Aging (NIA).

Immunostaining and imaging

Immunohistochemistry bright field staining was performed on 5 μm human and mouse brain paraffin sections as previously described [77, 99, 122]. In brief, sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated using a descending series of ethanol concentrations (100%, 95%, 70%). To retrieve the antigens, sections were boiled in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH = 6.0) using a microwave oven and cooled down for 1 h to reach room temperature. Brain tissue was treated with 3% H2O2 in deionized water for 20 min to block endogenous peroxidase activities. Slides blocked in 5% normal animal serum in 0.01 M TBS for 1 h at room temperature. Next, sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-mouse Cathepsin D (Goat, AF1029, 1:500, R&D Systems), anti-mouse Cathepsin Z (Goat, PA5-47048,1:500, Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-mouse GPNMB (Goat, AF2330, 1:1000, R&D Systems), anti-mouse Galectin-3 (Goat, AF1197,1:1000, R&D Systems), anti-mouse progranulin (Sheep, AF2557, 1:500, R&D System), or anti-human GPNMB (Rabbit, AF2550, 1:500, R&D System) antibody. ImmPRESS HRP polymer detection kits horse anti-goat IgG (MP7405-15, Vector laboratories) or horse anti-rabbit IgG (MP-7401-15, Vector laboratories) was used for detecting primary antibodies and amplifying signals. For mouse progranulin staining, biotinylated donkey anti-sheep secondary antibody (713-065-003, 1:200, Jackson ImmunoResearch) was used. To visualize staining, diaminobenzidine (DAB) with nickel enhancement (SK4100, Vector Laboratories) was performed and hematoxylin (72511, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used for nuclear counterstain. Finally, sections were dehydrated with increasing concentrations of ethanol (70%, 95%, 100%) and xylene for 2 min each then mounted with permanent mounting media (8312-4, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Whole slide images were captured on an Aperio AT2 Slide Scanner (Leica) and analyzed in Aperio ImageScope software.

Immunofluorescence staining was also performed on 5 μm mouse and human brain paraffin sections. Deparaffinization, rehydration and antigen retrieval steps were the same as immunohistochemistry staining above. Permeabilization was performed by incubating slides with 0.01 M TBS buffer containing 0.4%Triton-X 100 solution and 1% normal animal serum for 10 min. Non-specific binding was blocked with a one-hour incubation at room temperature with 5% normal animal serum in 0.1%Triton-X 100 in 0.01 M TBS. Autofluorescence from lipofuscin and blood vessels was blocked using Trueblack (#23007, Biotium) diluted in 70% ethanol for 30 s, followed by a rinse with TBS. Then, sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibody: anti-mouse GPNMB (Goat, AF2330, 1:1000, R&D Systems), anti-mouse Galectin-3 (Goat, AF1197, 1:1000, R&D Systems), anti-Iba1 (Rabbit, mAb17198, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-GFAP (Rabbit, Z0334, 1:1000, Agilent Dako) or anti-NeuN (Rabbit, mAb24307, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology) antibody. The following day, sections were incubated with fluorescent secondary antibodies: Donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (R37118, 1:500, Invitrogen), and Donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 647 (A-21447, 1:500, Invitrogen) for 1 h at room temperature. DAPI (#62248, 1:1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific,) was used to stain the nucleus and Prolong Gold anti-fade mountant (P36930, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used for cover slipping to protect fluorescent signals.

Immunoblot

Immunoblots were performed as previously described [27, 55, 72]. Briefly, human and mouse brain running samples were prepared in loading buffer with 50 mM 2-Mercaptoethanol (BME) followed by denaturing at 70 °C for 15 min. Protein samples were separated on Bio-Rad 4–20% 18-well midi gels at 100 V and transferred to a 0.2 µm nitrocellulose membrane using the Bio-Rad Trans-blot Turbo system. Membranes were stained with total protein stain (926-11010, Licor) and imaged on the Odyssey Fc (Licor) to access transfer efficiency and normalize protein abundance between samples. After blocking with Licor Odyssey blocking buffer for 1 h at room temperature, membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibody: anti-mouse Cathepsin D (Goat, AF965, 1:500, R&D Systems), anti-mouse Cathepsin Z (Goat, PA5-47048, 1:1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-mouse GPNMB (Goat, AF2330, 1:1000, R&D Systems), anti-mouse Galectin-3 (Goat, AF1197, 1:1000, R&D Systems), anti-human Galectin-3 (Goat, AF1154, 1:1000, R&D Systems), or anti-human GPNMB (Goat, AF2550, 1:1000, R&D Systems) antibody. All primary antibodies were diluted in 1:1 TBST/Blocking buffer. Alpha-tubulin (Rabbit, 1878-1, 1:10,000, Epitomics) and beta-actin (Rabbit, ab8227, 1:1000, Abcam) were used as loading controls. Near-infrared fluorescent secondary antibodies (diluted in TBST) or HRP-conjugated (diluted in 0.5% milk in TBST) antibodies were incubated for 1 h at room temperature: Donkey anti-goat Alexa Fluor 680 (A21084, 1:10,000, Invitrogen), goat anti-rabbit 790 (A11369, 1:10,000, Invitrogen), donkey anti-rabbit 680 (A21109, 1:10,000, Invitrogen), or donkey anti-goat HRP (705-035-003, 1:15,000, Jackson ImmunoResearch) were used. For HRP visualization, blots were incubated in WesternSure PREMIUM Chemiluminescent Substrate (926-95010, Licor) for 5 min before imaging. Near-infrared or chemiluminescent blots were imaged using the Odyssey Fc (Licor) and analyzed by Image Studio software 5.2.

ELISA

General ELISA protocols were performed as previously described [55, 63, 64]. Levels of GPNMB and galectin-3 in tissue were quantified using ELISAs Duosets according to the manufacturer’s protocol: human GPNMB (AF2550, R&D Systems), mouse GPNMB (AF2330, R&D Systems), human Galectin-3 (DY1154, R&D Systems), or mouse Galectin-3 (DY1197, R&D Systems). Additional ELISA reagents were from ELISA reagents kit 2 (DY008, R&D Systems). Briefly, ELISA plates were coated with 100 µL/well coating antibody diluted in coating buffer overnight at room temperature. After washing with 1 × wash buffer 3 times, plates were blocked with 1X reagent diluent 300 µL/well at least 1 h. Human brain RIPA lysates, CSF samples, mouse brain RIPA lysates or mouse plasma were diluted at 1:20, 1:4, 1:50, or 1:10 respectively, in 1X reagent diluent and added to plates with standard at 100 µL/well and incubated for 2 h. Next, 100 µl of diluted detection antibody was added per well. 100 µL of the working dilution of Streptavidin-HRP was added to each well and plates were incubated for 20 min in the dark. Then, 100 µL of substrate solution was added to each well and incubated for 15 min while still avoiding light. To stop the reaction, 50 µL of 2 N sulfuric acid was added to each well. Finally, ELISA plate sample absorbance (450 nm signal and 570 nm for background correction reading) was measured on an Epoch plate reader (BioTek) and processed using Gen5 software (BioTek). All samples were run in duplicate and values fell within the standard curve generated with recombinant human or mouse GPNMB or galectin-3 protein provided in DuoSet ELISA kits. Protein measurements in human and mouse brain samples were normalized to the amount of total protein added per well.

Statistical analysis

Standard curve generation and statistical analyses were performed by GraphPad Prism 8.0. An unpaired student's t-test for two groups and one-way or two-way ANOVA for more than two groups were used to generate p values. All quantitative data are presented as mean ± SEM and significance levels are denoted ****p < 0.0001, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01 and *p < 0.05.

Results

Proteomic analysis of Grn+/+ and Grn−/− mouse brain

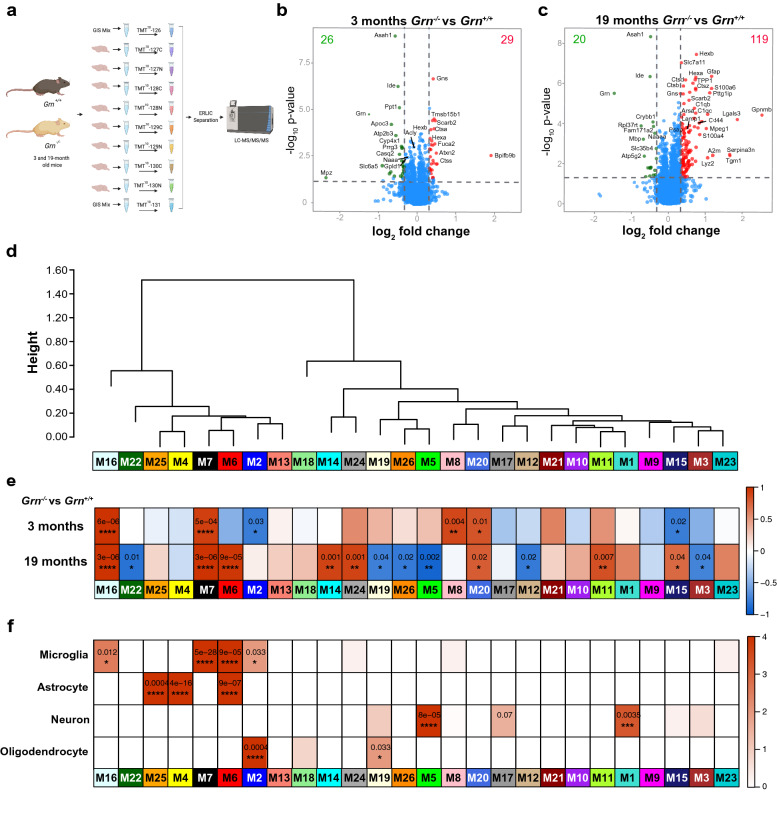

We used unbiased proteomics to quantify how PGRN deficiency changes the mouse brain proteome with age to provide insight into the function of PGRN and how PGRN deficiency causes neurodegeneration. This was accomplished using Tandem Mass Tag (TMT) isobaric labeling and synchronous precursor selection-based MS3 (SPS-MS3) mass spectrometry to perform quantitative proteomic analysis of the cerebral cortex in 3- and 19-month old Grn+/+ and Grn−/− mice (Fig. 1a). The use of 10-plex TMT labeling followed by off-line electrostatic repulsion-hydrophilic interaction chromatography (ERLIC) fractionation prior to LC–MS/MS enabled identification of 8,695 unique proteins. Next, we determined which proteins were differentially enriched or depleted (p ≤ 0.05; one-way ANOVA-Tukey HSD) in the brain proteomes of 3- or 19-month old Grn+/+ compared to age-matched Grn−/− mice (Fig. 1b, c); Additional file 1: table S3). In the 3-month Grn−/− mouse brain samples, 29 proteins increased and 26 proteins decreased in abundance compared to Grn+/+ mice of the same age (Fig. 1b). Gene ontology (GO) analysis of all significantly altered proteins Grn−/− mouse brain using MetaScape revealed a significant enrichment (− log10(p) > 10) of proteins involved in lysosome function (Kegg pathway: mmu04142) and glycosphingolipid metabolism (Reactome: R-MMU-1660662) (i.e. Gns, Scarb2, Hexa, Hexb, Fuca 2, Pppt1, and Ctsa) [136]. GO analysis focusing on downregulated proteins in the 3-month Grn−/− brain proteome identified a significant enrichment (− log10(p) > 4) of proteins involved in lipid catabolism (Acly, Apoc3, Asah1, Gpld1, Ppt1, Naaa; GO:0016042), which may indicate that PGRN deficiency causes impairment of the lysosomal degradation and recycling of lipids.

Fig. 1.

Proteomics and network analysis of Grn+/+ and Grn−/− mouse brain. a Schematic overview of experimental design. Quantitative proteomic analysis of the cerebral cortex of 3-month-old (n = 4 Grn+/+, n = 4 Grn−/−) and 19-month-old (n = 4 Grn+/+, n = 4 Grn−/−) mice was performed using Tandem Mass Tag (TMT) isobaric labeling and synchronous precursor selection-based MS3 (SPS-MS3) mass spectrometry. b, c Volcano plots illustrating differentially expressed proteins in 3- and 19-month-old mouse brains. Relative protein abundance (log2 Grn−/−/ Grn+/+) plotted against significance level (− log10 P-value), showing significantly (p < 0.05) decreased (Grn−/−/ Grn+/+ ratio < log2(− 1.25); green) and increased (Grn−/−/ Grn+/+ ratio > log2(1.25); red) proteins in Grn−/− mice. d WGCNA cluster dendrogram generated by hierarchical clustering of highly co-expressed genes followed by identifying 26 distinct modules coded by different colors. e Two-color heatmap is showing the relationship between modules and the bicor correlation of genotype. Significance levels are ****p < 0.0001, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01 and *p < 0.05. f Significance of cell type overlap is shown by one-color heatmap with P values. Relevance between each module and cell type was assessed by protein module overlap with known mouse microglia, astrocyte, neuron and oligodendrocyte markers. Significance levels are ****p < 0.0001, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01 and *p < 0.05

In 19-month-old Grn−/− mice, 119 proteins were increased and 20 proteins were decreased compared to Grn+/+ mice. In the brains of 19-month-old Grn−/− mice we found that an even larger number of lysosomal proteins were increased, including glycoprotein NMB (GPNMB), which is the most upregulated protein in aged Grn−/− mice (Fig. 1c). In addition to lysosome alterations, GO analysis revealed novel upregulated pathways in 19 month old Grn−/− mice including proteins involved in gliogenesis (C1qa, Dbi, Gfap, P2rx4, Stat3, Bin1, Zfp365) as well as inflammation, complement, and coagulation cascades (C1qa, C1qb, C1qc, C4b, Itgb2, and A2m) [136]. Thus, our initial analysis of the mouse brain proteome reveals an early dysregulation of proteins involved in lysosomal function and lipid metabolism in 3-month-old Grn−/− mice, which is exacerbated with age, leading to upregulation of proteins involved in the innate immune response and inflammation.

Co-expression protein analysis with Grn+/+ and Grn−/− mouse

Next, we performed weighted co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) on the Grn+/+ and Grn−/− mouse brain proteome datasets to determine the relationship between the changes in protein abundance we observed and biological pathways and cell types [66]. Network analysis identified 26 modules of strongly co-expressed groups of proteins (Fig. 1d; Additional file 1: table S4, table S5). Each protein co-expression module is defined by its first principal component, an eigenprotein, which is also the most representative weighted protein expression pattern across samples for a group of co-expressed proteins [102]. Modules were clustered based on relatedness defined by the correlation distance between eigenproteins (Fig. 1d). We calculated the relationship between modules and the biweight midcorrelation (bicor) [106] of eigenproteins to genotype and age of Grn mice and identified a number of modules that significantly correlated (Fig. 1e). Comparison of modules in the Grn+/+ 19-month versus Grn+/+ 3-month data set or Grn−/− 19-month versus 3-month Grn−/− data set identified many of the same modules, suggesting this analysis identifies common or shared protein modules that are generally altered during aging (Additional file 3: Fig. S1, online resource).

In contrast, comparison of 3-month old Grn−/− mice to 3-month old Grn+/+ mice identified 6 modules that significantly correlated to Grn deficiency (Fig. 1e). The ontology of these modules are described by a structural component, function, or biological process: modules M2 myelin, M7 lysosome/immune response, M8-synapse, M15-cation channel/transport, M16 lysosome/hydrolase activity, M20 ribosome (Fig. 2 and Additional file 1: table S5; Additional file 3: Fig. S2–5, online resource). The M2 myelin and M15-cation channel module were modestly, but significantly (p = 0.003 and p = 0.02, respectively), decreased in the 3-month cohort. The M16 (Fig. 2b, h) and M7 (Fig. 2a, g) lysosome modules were the most upregulated modules and the most significantly correlated (p = 6 × 10−6 and p = 5 × 10−4, respectively) to Grn deficiency in the 3-month old Grn−/− brain proteome, indicating these modules are key drivers of disease pathogenesis.

Fig. 2.

Modules that correlate to Grn deficiency and age highlight dysregulation of proteins involved in the lysosome, inflammation, and neuronal synaptic function. a–c Box plots illustrate eigenprotein values for modules (M7, M16, and M6 red) that are upregulated in 3- or 19-month-old Grn−/− mice compared to Grn+/+ mice. d–f Box plots of M5, M3 and M19 modules that have decreased eigenprotein values in Grn−/− versus Grn+/+ in 19-month-old mice. Values were analyzed by two-way ANOVA. Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis, calculated using GO Elite v1.2.5, of proteins in modules, highlights proteins involved in: g immune effector process, glycoprotein-binding, lysosome (M7), h protein transport, hydrolase activity, lysosome (M16), i oxidoreductase activity, regulation of NF kappa B cascade, lysosome (M6), j glutamate signaling, postsynaptic density, neuron spice and dendrite (M5), k regulation of neurotransmitter secretion, voltage-gated potassium channel activity, cytoplasmic microtubule (M3), i regulation of creation, synaptic membrane and synapses (M19). Light-green bars: biological process, light-blue bars: molecular function, brown-bars: cellular component

Comparison of 19-month old Grn−/− mice to 19-month old Grn+/+ mice identified 14 modules with significant correlation to Grn deficiency (Fig. 1e). Three of the same modules (M7, M16, and M20) that were increased in 3-month old Grn−/− mice were similarly increased in the 19-month old group. Novel modules that were altered in the 19-month old Grn−/− brain proteome include: modules M3-microtubule/cell-cycle (Fig. 2e, k), M5-postsynaptic/glutamate signaling (Fig. 2d, j), M6-lysosome/oxidation–reduction (Fig. 2c, i), M11-ribosome/translation, M12-nucleus/nucleic acid metabolism, M14-GPCR signaling, M19-synaptic membrane/secretion (Fig. 2f, i), M22-pyruvate/acetyl–CoA metabolism, M24-axon/defense response, and M26-membrane/mitochondria (Fig. 2a–l and Additional file 3: Fig. S2–5, online resource). The three most significantly upregulated modules M6 (Fig. 2c, i; p = 9 × 10−5), M7 (Fig. 2a, g; p = 3 × 10−6), and M16 (Fig. 2b, h; p = 3 × 10−6) are related to lysosome function, further implicating the importance of this pathway to normal PGRN function and alteration following Grn deficiency. Interestingly, the most significantly decreased modules in 19-month old Grn−/− brain contain proteins important for postsynaptic function and glutamate signaling (M5, Fig. 2d, j; p = 0.002), synaptic membrane/secretion (M19, Fig. 2f, i; p = 0.04), and mitochondria function (M22, p = 0.01; M26, p = 0.02; Additional file 3: Fig. S5).

Next, we asked if the changes we observed in specific modules were driven by changes in cell types. To do this, we evaluated whether a given module was enriched in marker proteins for particular CNS cell types using a previously established cell-type specific proteome derived from the mouse brain [53](Fig. 1f; Additional file 1: table S1). We observed significant enrichment of neuronal proteins in the M5 postsynaptic module (Fig. 1f; Dbn1, Shank2, Shank1, Camk4) and M1 module (Fig. 1f; Dpysl5, Madd, Sugp2, Lamb1). Further, oligodendrocyte protein markers were enriched in the M2 myelin module (Fig. 1f; Plp1, Mbp, Mog, cldn11) and the M19 synaptic membrane module (Fig. 1f; Ncald, Anks1b, Jak2, Gpr158). The observation that neuronal (M5, p = 0.002) and oligodendrocyte (M19, p = 0.033) modules are decreased specifically in the brain of 19-month, not 3-month, Grn−/− mouse brain suggests that neuronal loss and demyelination are a late-stage consequence of Grn deficiency.

We also found significant enrichment of microglial proteins in the M16 lysosome module (Fig. 1f; Lgmn, Uap1l1, Stk11ip), the M7 lysosome module (Fig. 1f; Gpnmb, P2rx4, Lgals3, Tcirg, Hexb), the M6 lysosome module (Fig. 1f; Cotl1, Msn, Ctsd, Tgm2), and the M2 myelin module (Fig. 1f; Aldh3b1). Protein markers of astrocytes were significantly enriched in the M6 module (Fig. 1f; Gja1, Dhrs4, Acsf2, Nadk2) as well as the M4 (Fig. 1f; Gstt1, Ccbl2, Abat, Aldh4a1, Gcsh) and M25 modules (Fig. 1f; Fam213a, Vcl, Hrsp12, Acadvl, Hadha), both of which contain mitochondrial proteins. Our observation that M7 and M16 modules are both enriched in microglia markers and lysosomal proteins, and are the most significantly elevated modules in the 3-month old Grn−/− brain proteome, suggests that dysregulation of microglial lysosomes may be the earliest pathologic change in Grn−/−.

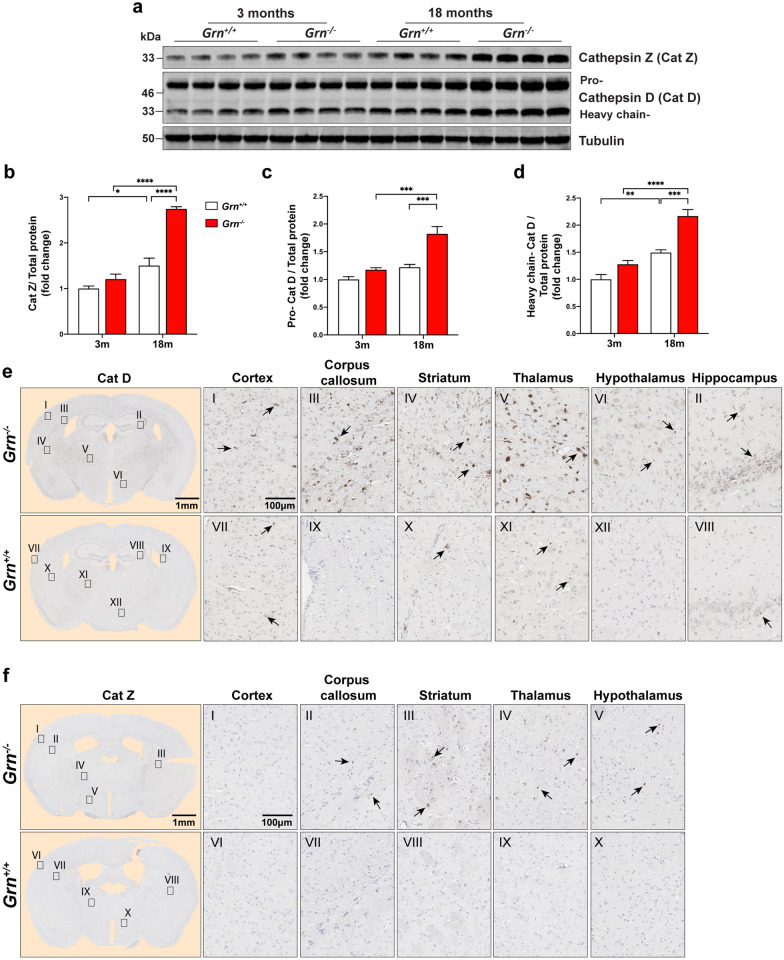

Aged Grn−/− mouse brains accumulate lysosomal proteins and markers of neuroinflammation

Because GO and network analysis revealed that dysregulation of the lysosomal pathway was an early and highly significant event in the Grn−/− mouse brain proteome, we focused on validating and examining these changes using biochemical and immunological orthogonal approaches. First, we examined the expression levels and neuroanatomical location of two lysosomal proteins, cathepsin Z (protein abbreviation, Cat Z; gene, Ctsz) and cathepsin D (protein abbreviation, Cat D; gene Ctsd), enriched in modules M7 and M6, respectively. We performed immunoblotting of whole brain lysates from 3-month (n = 8) and 18-month-old (n = 8) Grn+/+ and Grn−/− mice. First, we examined Cat Z, a unique cysteine cathepsin, previously implicated in neurodegenerative diseases, but not examined in the context of FTD or PGRN biology [3, 13, 110]. Levels of Cat Z increased in Grn+/+ (1.5-fold) and Grn−/− (2.3-fold) in whole brain lysates of 18-month mouse brain as measured by quantitative immunoblotting (Fig. 3a, b). Next, we examined the levels of Cat D, a key lysosomal aspartyl protease that has been suggested to play an important role in PGRN function [9, 115]. We observed a significant increase in both the pro- (~ 46 kDa) and heavy chain (~ 33 kDa) isoforms of Cat D (Fig. 3a, c, d). There were no significant differences in Cat Z and Cat D levels between Grn+/+ and Grn−/− mouse brain at 3 months, suggesting PGRN deficiency leads to an age-dependent increase of both Cat Z and Cat D. Next, we performed immunostaining on 19-month-old (n = 14) Grn−/− brain coronal sections to determine the regions of Cat Z and Cat D expression and upregulation. We found strong immunostaining of Cat D in the thalamus, corpus callosum, striatum, and hippocampus in Grn−/− mouse brains (Fig. 3e). Immunostaining of Cat Z was also increased in the thalamus, corpus callosum, and striatum of Grn−/− mice, but to a lesser extent than Cat D (Fig. 3f). Taken together, immunoblotting and immunostaining of Grn−/− mouse brains confirm our proteomic results and demonstrate that PGRN deficiency leads to an age-dependent increase in the lysosomal proteins Cat Z and Cat D.

Fig. 3.

The lysosomal proteins, cathepsin D (Cat D) and Cathepsin Z (Cat Z), are elevated in Grn−/− mouse brains. a Images of immunoblots of lysates of Grn+/+ and Grn−/− mouse brains at 3- (n = 4) and 18- (n = 4) months of age probed for Cat (33 kDa), pro Cat D (~ 48 kDa) and the mature heavy chain of Cat D (~ 33 kDa). Alpha-tubulin used as a loading control. b–d Fold change of signal intensity determined by comparing the 3-month-old Grn+/+ group mean signal intensity measurement value of Cat Z and Cat D bands from (a) and normalized to total protein signal of blot. f Immunohistochemistry staining of Cat D in 19-month-old Grn+/+ and Grn−/− mouse brains. Region specific Cat D expression in the cortex (I, VII), hippocampus (II, VIII), corpus callosum (III, IX), striatum (IV, X), thalamus (V, XI) and hypothalamus (VI, XII). g Region specific Cat Z expression in the cortex (I, VI), corpus callosum (II, VII), striatum (III, VIII), thalamus (VI, IX), and hypothalamus (V, X) of 19-month-old Grn+/+ and Grn−/− mouse brains. Scale bars (1 nm to 100 µm) are labeled in images and quantitative data shown as mean ± SEM, p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001

An age-dependent increase of GPNMB and Galectin-3 in Granulin Knockout mice

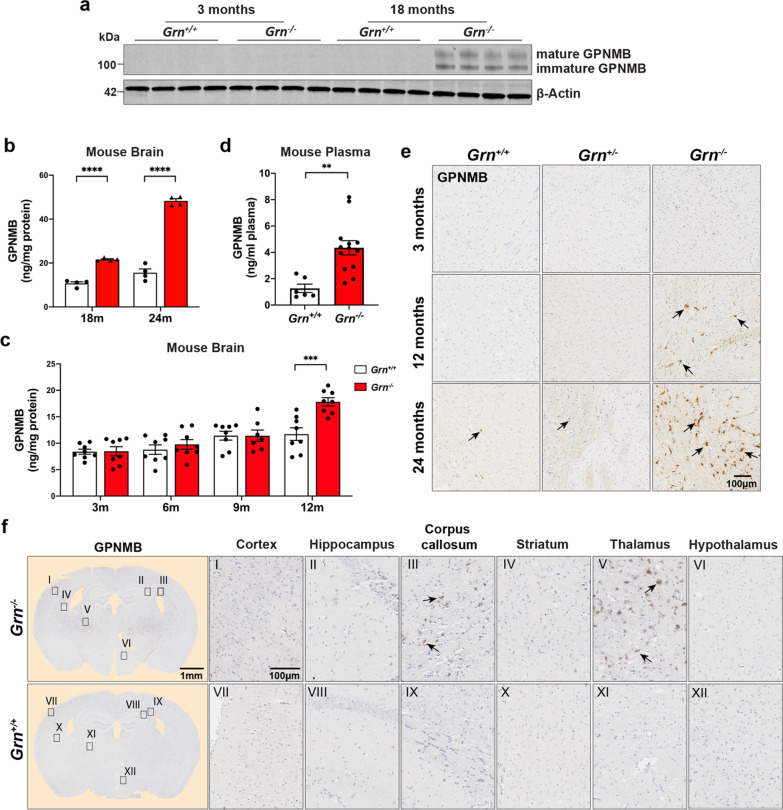

Next, we focused on examining the expression of transmembrane glycoprotein NMB (GPNMB) and galectin-3 (LGALS3), because these were two of the most enriched proteins in the Grn−/− brain proteome, and are key hub proteins of module M7 (Figs. 1d, e, 2a). Additionally, excess levels of GPNMB and galectin-3 have not been previously associated with neurodegeneration associated with FTD, suggesting they might be involved in pathogenesis or serve as biomarkers. Towards this goal, we examined GPNMB and galectin-3 expression levels in Grn+/+ and Grn−/− at different ages using immunoblotting and immunohistochemistry (Figs. 4, 5).

Fig. 4.

GPNMB levels increase in the brain and plasma of Grn−/− mice with age. a Representative immunoblots of immature and mature (glycosylated) GPNMB in mouse brain lysates of Grn+/+ and Grn−/− mice at 3- and 18-months of age. Beta-actin used as loading control. b Levels of GPNMB (ng/mg protein) in mouse brain lysates measured by ELISA. Tissue from Grn+/+ (white) and Grn−/− (red) mice at 18-months (n = 4 per group) and 24-months (n = 4 per group), respectively. Data analyzed by two-way ANOVA. c ELISA quantification of mouse brain GPNMB levels (ng/mg of brain protein) in Grn+/+ (white) and Grn−/− (red) mice at 3-, 6-, 9- and 12-month ages (n = 8 per group). Values analyzed by two-way ANOVA. d Levels of GPNMB in 19-month old Grn+/+ (white) and Grn−/− (red) mouse plasma measured by ELISA. Data (n = 6 for Grn+/+ and 13 for Grn−/−) analyzed using an unpaired student t-test. e Representative sections of Grn+/+, Grn+/−, and Grn−/− mouse thalamus at 3-, 12-, and 24-months of age immunostained for GPNMB. f 19-month-old Grn+/+ and age-matched Grn−/− mouse brain coronal sections were stained with anti-GPNMB antibody. GPNMB staining shown for multiple brain regions (cortex (I, VII), hippocampus (II, VIII), corpus callosum (III, IX), striatum (IV, X), thalamus (V, XI) and hypothalamus (VI, XII)). Scale bars (1 nm to 100 µm) are labeled in images and quantitative data shown as mean ± SEM, p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001

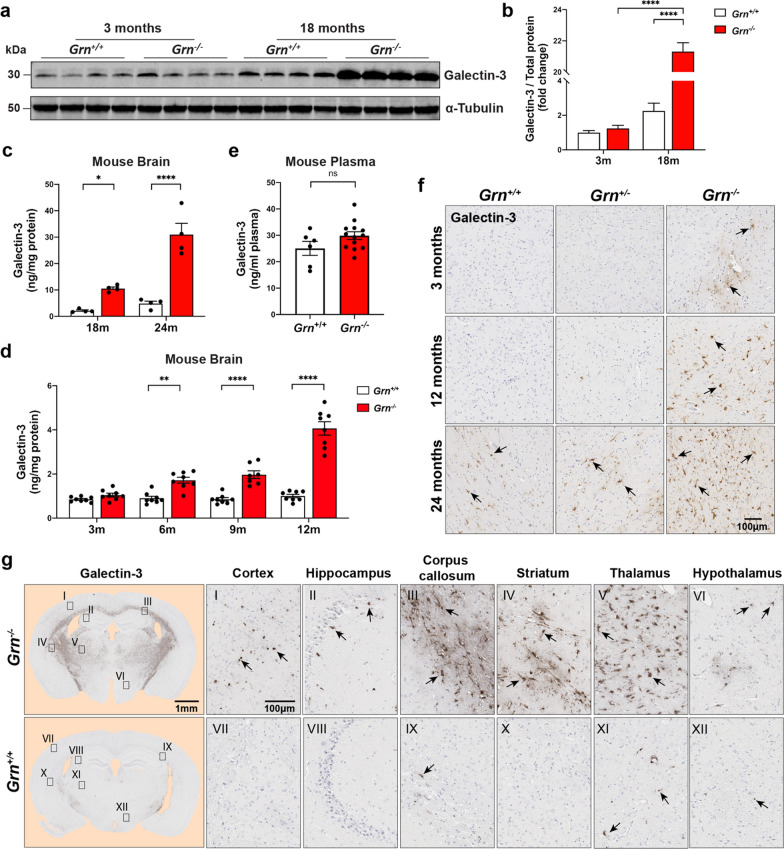

Fig. 5.

Galectin-3 levels are robustly increased with age in Grn−/− mouse brain. a, b Representative immunoblot (left) and quantification (right) of galectin-3 levels in the brain lysates of 3- and 18-month-old Grn+/+ mice and age-matched Grn−/− mice (n = 4 mice each group). Band values were normalized by total protein values and analyzed by two-way ANOVA. c Levels of mouse brain galectin-3 (ng/mg of protein) in lysates were quantified by ELISA. Galectin-3 levels were normalized to total protein added to assay and results analyzed by two-way ANOVA. d Galectin-3 protein measured in 19-month-old Grn+/+ and Grn−/− mice plasma samples by ELISA. Data analyzed using unpaired t-test. e Brain sections from Grn+/+, Grn+/−, Grn−/− mice at 3-, 12- and 24-months of age were immunostained with galectin-3 antibody. Representative images of thalamus from each genotype are shown. f 19-month-old Grn+/+ and age-matched Grn−/− mice brain coronal sections were stained with anti-GPNMB antibody and images from multiple regions (cortex (I, VII), hippocampus (II, VIII), corpus callosum (III, IX), striatum (IV, X), thalamus (V, XI) and hypothalamus (VI, XII)) are shown. Scale bars (1 nm to 100 µm) are labeled in images and quantitative data shown as mean ± SEM, p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001

First, we were unable to detect mouse GPNMB in either 3-month old Grn+/+ or Grn−/− mouse brains by immunoblot analysis of detergent brain extracts. However, in 18-month-old Grn−/− mouse brain lysates, we detected strong immunoreactive bands for mature (glycosylated; top band) and immature GPNMB compared to Grn+/+ mice (Fig. 4a). This result confirms our proteomic data that GPNMB is a highly upregulated protein in aged 18-month-old Grn−/− mouse brain. Next, we used ELISAs to quantify the level of GPNMB in whole brain lysates from 18- (n = 8) and 24-month-old (n = 8) Grn+/+ and Grn−/− mice. GPNMB levels were significantly increased in both 18-month-old Grn−/− (2.0-fold; p < 0.0001) and 24-month-old Grn−/− (3.1-fold; p < 0.0001) brain tissue compared to age-matched Grn+/+ brain tissue (Fig. 4b). Subsequently, we asked when GPNMB is first elevated in Grn−/− mouse tissue. To do this, we quantified GPNMB levels in Grn+/+ and Grn−/− mouse brain tissue at 3- (n = 16), 6- (n = 16), 9- (n = 16), and 12- (n = 16) months of age by ELISA (Fig. 4c). Based on this analysis, GPNMB levels are first significantly increased at 12-months of age in Grn−/− mouse brains. Then, we asked if an increase in GPNMB levels could be detected in the blood. Indeed, GPNMB levels were increased ~ 2-fold (p < 0.01) in 19-month-old Grn−/− mice plasma compared to Grn+/+ (Fig. 4d).

Next, we performed immunohistochemical staining for GPNMB on sagittal brain sections from 3-, 12-, and 24-month-old Grn+/+, Grn+/−, and Grn−/− mice to determine where GPNMB expression is most upregulated in the brain (Fig. 4e). We noted elevated GPNMB staining in the thalamus of Grn−/− mice at 12 and 24 months of age compared to both Grn+/+ and Grn+/− brains, in agreement with our ELISA results. Further, there was no appreciable difference in GPNMB staining between Grn+/+ and Grn+/− mice at any age. Finally, we completed a more extensive survey of GPNMB staining on coronal brain sections of 19-month old Grn+/+ and Grn−/− mice. We observed strong increases in GPNMB immunoreactivity in the corpus callosum and the thalamus and lower levels of increase in the hippocampus, cortex, and striatum (Fig. 4f).

Next, we repeated the same analyses for galectin-3. Based on quantitative immunoblotting, galectin-3 levels were 21-fold higher (p < 0.0001) in 18-month-old Grn−/− mouse brain lysate compared to age-matched Grn+/+ samples (Fig. 5a, b). In order to quantify galectin-3 protein levels more accurately, RIPA lysates of 18- and 24-month old mouse brain were analyzed using ELISAs. Galectin-3 levels were significantly increased in Grn−/− mouse brains in both ages compared to age-matched Grn+/+ mice (Fig. 5a, b). At 18-months, galectin-3 levels were 2.12 ± 0.64 ng/mg protein in Grn+/+ mice and 10.53 ± 1.25 ng/mg protein in Grn−/− mice. At 24-months, galectin-3 levels increased to 4.85 ± 1.78 ng/mg protein in Grn+/+ mice and 30.99 ± 8.55 ng/mg protein in Grn−/− mice (Fig. 5a, b). Subsequently, we asked what age is galectin-3 first elevated in Grn−/− mouse tissue. We quantified galectin-3 levels in Grn+/+ and Grn−/− mouse brain tissue at 3- (n = 16), 6- (n = 16), 9- (n = 16), and 12- (n = 16) months of age by ELISA (Fig. 5d). Based on this analysis, galectin-3 levels are first significantly elevated at 6 months of age in Grn−/− mouse brains (p < 0.01) and continue to increase with age (Fig. 5d). Interestingly, unlike GPNMB, we did not detect a significant change in galectin-3 levels in Grn−/− plasma compared to Grn+/+ plasma (Fig. 5e).

Next, we asked where galectin-3 expression is most upregulated in the brain. First, we performed immunohistochemical staining for galectin-3 on sagittal brain sections from 3-, 12-, and 24-month-old Grn+/+, Grn+/−, and Grn−/− mice. We noted elevated galectin-3 staining in the thalamus of Grn−/− mice as early as 3 months of age compared to both Grn+/+ and Grn+/− brains (Fig. 5f). This is an earlier time point than our ELISA results, which used whole brain lysates, which may mask subtle changes in focal regions of the brain. Further, there was no appreciable difference in galectin-3 staining between Grn+/+ and Grn+/ mice at any age. Finally, we completed a more extensive survey of galectin-3 staining on coronal brain sections of 19-month old Grn+/+ and Grn−/− mice (Fig. 5g). We observed very strong galectin-3 immunoreactivity throughout the myelin tracts of the corpus callosum, the striatum, and the thalamus. Galectin-3 immunoreactivity was also increased in the cortex, hippocampus, and hypothalamus, although the staining was less widespread and more punctate. Overall, these results confirm our initial proteomics data that GPNMB and galectin-3 levels are specifically increased in the brains of Grn−/− mice.

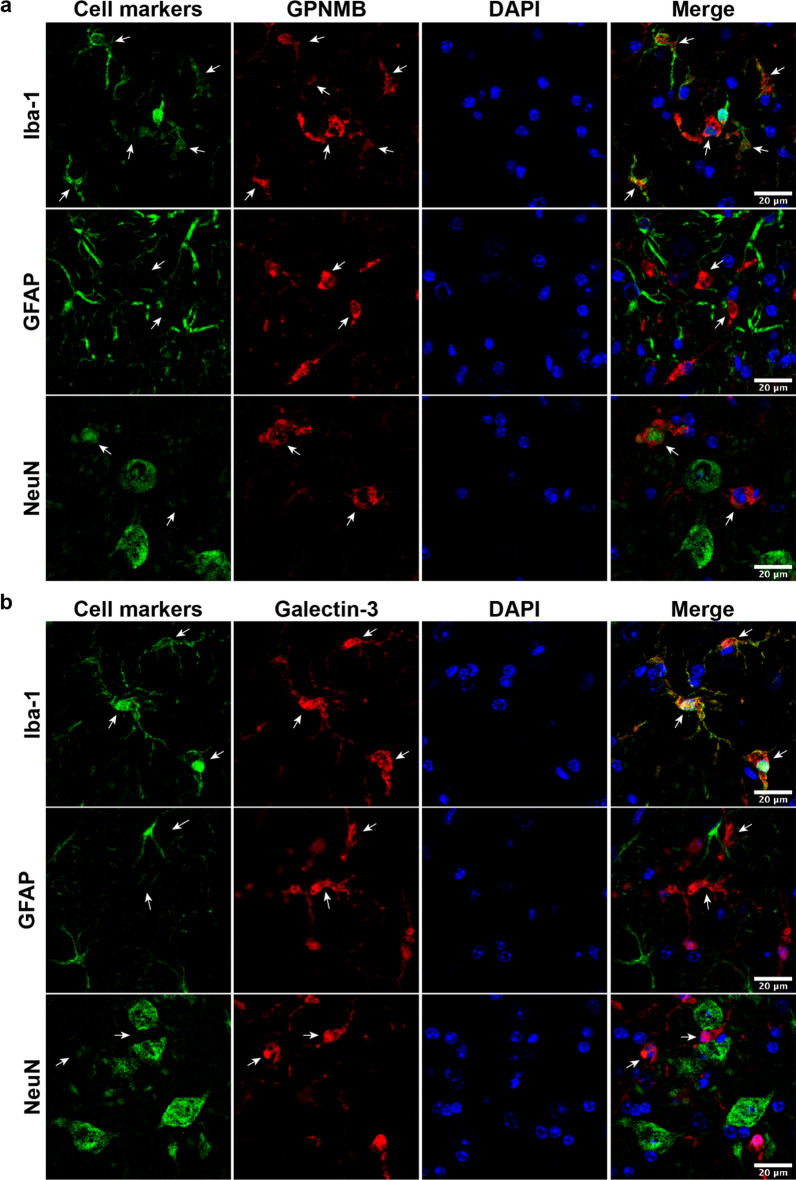

Cellular localization of GPNMB and galectin-3 in Grn−/− mice

Next, we aimed to determine which cells express GPNMB and galectin-3 in 19-month-old Grn−/− mice brains. We performed double immunofluorescent staining for GPNMB or galectin-3 with antibody markers for microglia (Iba-1), astrocytes (GFAP), and neurons (NeuN) (Fig. 6a, b). We detected strong co-localization between GPNMB, galectin-3, and Iba-1, indicating microglia express both proteins in aged Grn−/− mouse brain. This further supports our network-based proteomic analysis that detected a strong overlap between module M7, which contains GPNMB, galectin-3, and microglia cell markers (Fig. 1f). In contrast, we did not detect co-localization between GFAP-positive astrocytes and GPNMB or galectin-3. Similarly, we did not detect robust co-localization of GPNMB or galectin-3 signal in NeuN-positive neurons. On occasion, we observed GPNMB co-staining in some cells that were weakly positive for NeuN. In summary, double immunofluorescent suggests that microglia are the major source of GPNMB and galectin-3 expression in Grn−/− mouse brains.

Fig. 6.

GPNMB and galectin-3 co-localize with Iba-1 positive microglia cells in Grn−/− mouse brain. a Representative immunofluorescent co-staining for different cell markers (Iba-1, microglia; GFAP, astrocytes; NeuN, neurons) are shown in green, GPNMB (red), and nuclei (DAPI; blue) in brains of 19-month-old Grn−/− mice. b Representative immunofluorescent co-staining for different cell markers (Iba-1, microglia; GFAP, astrocytes; NeuN, neurons) are shown in green, galectin-3 (red), and nuclei (DAPI; blue) in brains of 19-month-old Grn−/− mice. Scale bars (20 µm) labeled in images

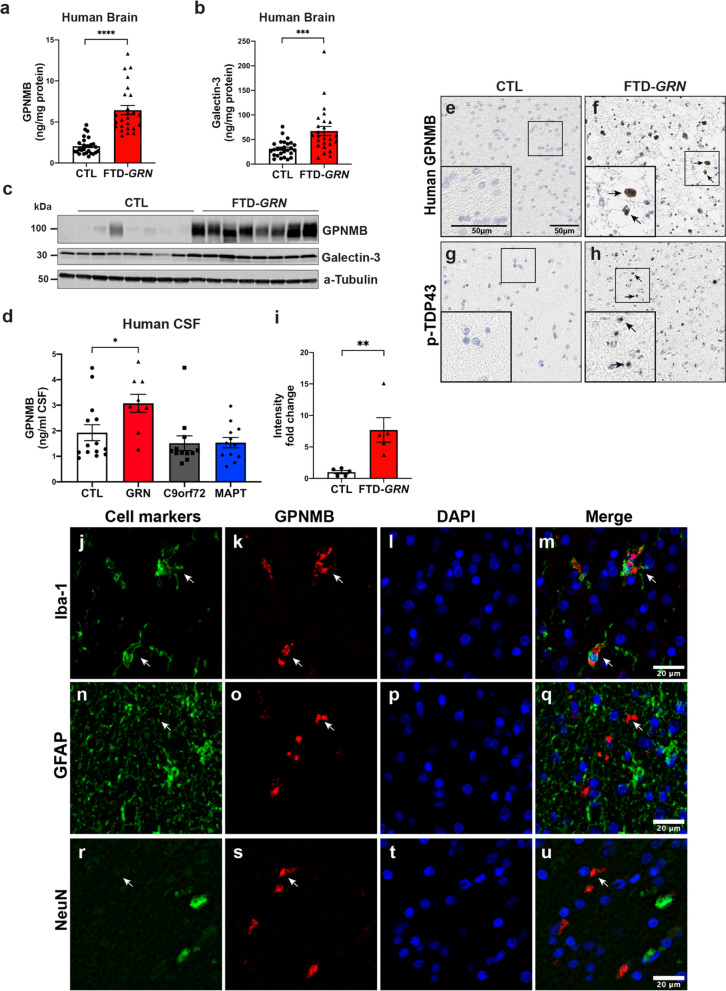

GPNMB and Galectin-3 are increased in FTD-GRN brain tissue

Finally, we asked if the pathologic changes we observed in aged Grn−/− mice also occur in the brains of FTD-GRN patients. We generated detergent lysates of the frontal lobe from 21 FTD-GRN samples and 23 cognitively normal controls. Initial immunoblotting of a subset of these cases suggested an increase in both GPNMB and galectin-3 in FTD-GRN brain homogenate compared to controls. Next, in order to more accurately quantify all samples, we measured human GPNMB and galectin-3 using sandwich ELISAs. Levels of GPNMB (p < 0.0001) and galectin-3 (p < 0.001) were both significantly increased in FTD-GRN brain homogenates compared to controls (Fig. 7a, b).

Fig. 7.

GPNMB and galectin-3 levels are elevated in FTD-GRN brains. a, b GPNMB and galectin-3 levels (ng/mg protein) were measured in frontal lobe tissue lysates generated from cognitively normal controls (CTL; n = 27) and FTD-GRN patients (n = 25). Data analyzed using unpaired t-test. c Representative immunoblots for GPNMB and galectin-3 in frontal lobe lysates from cognitively normal controls (n = 8) and FTD-GRN (n = 8) patients. d GPNMB levels (ng/mL) in CSF samples form cognitively normal controls (n = 14), FTD-GRN (n = 9), FTD-C9orf72 (n = 12) and FTD-MAPT (n = 12) samples quantified by ELISA. Data analyzed using one-way ANOVA. e, f GPNMB immunostaining was performed on frontal lobe tissue sections from cognitively normal controls (n = 5) (e) and FTD-GRN (n = 5) (f) patients. g, h Immunostaining for p-TDP 43 was stained on adjacent sections from identical samples in e, f as marker of FTLD pathology. i GPNMB staining intensity in human brain sections (e, f) were measured and presented as fold change. Representative immunofluorescence staining for cell markers (green) (j, n, r), GPNMB (red) (k, o, s), DAPI (blue) (i, p, t) in paraffin sections of brains from FTD-GRN cases. Iba-1, GFAP, NeuN used for markers of human microglia, astrocytes, and neurons respectively. GPNMB and Iba-1 signals overlap (arrow) (m) whereas, no overlapping signal was observed in co-staining with GFAP or NeuN (q, u). Scale bars were labeled in the images. Data analyzed by unpaired t-test. Scale bars (20 µm) labeled in images and quantitative data are shown as mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001

Subsequently, we examined the distribution of GPNMB in more detail in FTD-GRN brains. First, we examined GPNMB expression in the frontal lobe of five FTD-GRN cases compared to age-matched, cognitively normal controls. Specificity of the anti-GPNMB antibody for immunohistochemistry was validated using recombinant GPNMB protein to block staining (Additional file 3: Fig. S6, online resource). Interestingly, the strongest signal for GPNMB was detected in the white matter of the frontal lobe in FTD-GRN brains (Fig. 7e, f). Intensity of GPNMB immunoreactivity was 6.5-fold higher (p < 0.01) in the frontal lobes of FTD-GRN brains compared to matched regions from the brains of cognitively normal controls (Fig. 7e, f, Fig. S7a–d). Adjacent sections of FTD-GRN brains, but not controls, were immunopositive for phosphorylated TDP-43, confirming the presence of FTLD pathology in these cases [54, 81] (Fig. 7g, h, Fig. S7e–h). Then, to address cell-type specificity, we performed double immunofluorescent staining of GPNMB and antibody markers for microglia (Iba-1), astrocytes (GFAP), and neurons (NeuN) (Fig. 7j–u). We detected strong co-localization between GPNMB and Iba-1 in human FTD-GRN brains. No co-localization between GPNMB and GFAP or NeuN signal was detected. These data suggest microglia are the predominant source of GPNMB expression in human FTD-GRN brains.

Next, we asked if GPNMB levels were increased in FTD bio-fluids. We obtained CSF from patients with pathogenic genetic FTD mutations collected from the Advancing Research and Treatment for Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration (ARTFL) and Longitudinal Evaluation of Familial Frontotemporal Dementia Subjects (LEFFTDS) studies that were stored in the National Centralized Repository for Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (NCRAD) [95, 97]. GPNMB protein levels were quantified with sandwich ELISAs in CSF samples from individuals that were cognitively normal (controls; n = 14) and individuals with known mutations that cause FTD (FTD-GRN n = 13, FTD-C9orf72 n = 13, or FTD-MAPT n = 12). GPNMB levels were significantly up regulated (p < 0.05) in the FTD-GRN group (3.07 ± 0.35 ng/mL CSF) compared to controls (1.92 ± 0.31 ng/mL CSF) (Fig. 7d). In contrast, there was no significant difference in GPNMB levels between controls and FTD-C9orf72 or FTD-MAPT CSF samples.

Discussion

Although PGRN haploinsufficiency is a well-established cause of FTD, the function of PGRN and the pathogenic cascade caused by PGRN deficiency that ultimately leads to neurodegeneration is still unclear [22, 86]. In this study, we performed deep proteomic analysis of whole brains from Grn−/− mice, which recapitulate many features of FTD, including behavioral impairments and neuroinflammation [5, 10, 60, 82].

The first major finding is that the levels of lysosomal proteins are altered in young 3-month old c mouse brains. Our proteomics data is the first to find lysosomal dysregulation at such an early time point. This is likely due to the sensitivity of TMT-based proteomics and the known discrepancy between RNA transcript levels and protein expression [102]. In particular, we detected significant increases in well-established proteins that localize to the lumen or membrane of the lysosome including glucosamine (N-Acetyl)-6-Sulfatase (GNS), prosaposin (Psap), lysosomal integral membrane protein-2 (Limp-2/Scarb2), cathepsin A (CtsA), and hexosaminidases A and B (Hexa; Hexb). Importantly, the genes encoding all of these proteins harbor pathogenic mutations that cause lysosome storage disorders [91]. Furthermore, expression of these and other lysosomal genes are under control of the transcription factors TFEB and TFE3 and are up-regulated under conditions of lysosomal stress or dysfunction [93, 98, 101]. Thus, early lysosome dysfunction in Grn−/− mice may manifest by increased expression of many lysosomal proteins. In agreement with our findings, the mRNA transcripts of many of the lysosomal genes we have identified have been reported to be increased in older Grn−/− mice [42, 135]. Taken together, our data indicate that lysosomal dysfunction occurs early in Grn−/− brains and likely initiates pathogenesis and eventual neurodegeneration.

Our findings also provide insight into the function of PGRN. Recently, a potential role of PGRN in lysosome homeostasis has emerged based on the discovery that multiple cases of homozygous GRN mutation carriers develop neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis-11 (CNL11), a lysosomal storage disease [4, 18, 50, 105]. We, and other labs, have found that PGRN is trafficked to the lysosome and processed by cathepsins into granulins, which may be bioactive [47, 68, 133]. However, the function of PGRN and granulins within the lumen of the lysosome is still unclear. Because PGRN deficiency causes impairment of lysosomal protease activity and accumulation of lipofuscin [125], one possibility is that loss of PGRN/granulins directly or indirectly decrease the levels and/or activity of a lysosomal hydrolase.

With this idea in mind, our observation that a subset of the most significantly downregulated proteins (Acly, Apoc3, Asah1, Gpld1, Ppt1, Naaa) in the 3 month Grn−/− brain proteome are involved in lysosomal lipid catabolic process is important. Of these proteins two, ATP-citrate lyase (Acly) and apolipoprotein (apo) C-III (Apoc3), are involved in lipogenesis and lipid homeostasis [30, 94]. Intriguingly, the remaining proteins are all involved in lipid degradation pathways. N-acylsphingosine amidohydrolase 1 (Asah1) hydrolyzes sphingolipid ceramides into sphingosine and free fatty acids in the lysosome [87]. N-Acylethanolamine Acid Amidase (Naaa) degrades bioactive fatty acid amides, such as N-palmitoylethanolamine [114]. Palmitoyl-protein thioesterase 1 (Ppt1) removes thioester-linked fatty acyl groups like palmitate from modified cysteine residues during lysosomal degradation of proteins [59]. Finally, glycosylphosphatidylinositol specific phospholipase D1 (Gpld1) hydrolyzes the inositol phosphate linkage in proteins anchored by phosphatidylinositol glycans (GPI-anchor) to release proteins from the membrane and has recently been linked to the cognitive benefits of exercise for the aged brain [49]. Of note, earlier work found that loss of PGRN leads to an accumulation of polyunsaturated triacylglycerides and reduced diacylglycerides and phosphatidylserines in Grn−/− fibroblasts and mouse brains [29]. Our data provide additional evidence that PGRN deficiency leads to impaired degradation and recycling of lipids in the lysosome. Further work is necessary to determine if PGRN or granulins have a direct or indirect role in lysosomal lipid metabolism and homeostasis.

Our analysis of differentially expressed proteins in 19-month-old Grn−/− brains uncovered an even greater number of lysosomal proteins that are increased including Hexa, Hexb, Tpp1, and Fuca2. Intriguingly, proteins involved in inflammation and immune response (i.e. complement genes C1qa, C1qb, and C1qc) are significantly increased. Our data agrees with earlier work demonstrating that multiple Grn−/− mouse models have age-dependent microgliosis and astrogliosis throughout the brain including the cortex, hippocampus, and thalamus [1, 37, 82, 127, 132]. The upregulation of C1qa, C1qb, and C1qc we observe is consistent with previous transcriptomic data from Grn−/− mice, which reported upregulation in C1qa, C1qb, and C1qc before the onset of neurodegenerative features [29, 70]. Further, microglia isolated from 5.5-month old Grn−/− mice are activated and upregulate expression of genes associated with a microglial neurodegenerative phenotype (MGnD) [41]. Thus, gliosis and a robust inflammatory response is a consistent observation in multiple Grn−/− mouse models that increases with age, suggesting this is may be a downstream consequence initially triggered by lysosome dysfunction.

We also identified novel proteins that increase with age in the brains of Grn−/− mice. In particular, two of the most strongly up-regulated proteins were GPNMB (also known as osteoactivin) and galectin-3, suggesting they may play an important role in disease progression. Our co-localization studies demonstrate that GPNMB and galectin-3 are strongly expressed by microglia in aged Grn−/− mouse brain. GPNMB is a widely expressed transmembrane type I protein that has been implicated in many cellular functions including cell adhesion, cell migration, cell proliferation, and cell differentiation [113]. Intriguingly, variants in GPNMB are associated with Parkinson’s disease, highlighting the potential importance of GPNMB broadly in neurodegenerative diseases [52, 89]. Galectin-3 is a member of the lectin family, contains a carbohydrate-recognition-binding domain that mediates binding of β-galactosides, and plays an important role modulating inflammation [28]. Galectin-3 has also been implicated in brain innate immunity associated with neurodegeneration [16]. High levels of both GPNMB and galectin-3 levels have been found in the brain of 5xFAD mice [51] as well also the brains of PD and AD patients [11, 61, 75, 100]. Additionally, levels of GPNMB were elevated in grey and white matter of spinal cord of ALS patients [79].

We observed the strongest increases in GPNMB and galectin-3 expression in the thalamus of Grn−/− mouse, providing additional evidence that this region of the brain is particular vulnerable to loss of PGRN [70]. We also found high levels of GPNMB and galectin-3 in the corpus callosum, which is highly myelinated. Abundant galectin-3 staining was found along white matter tracts in the cortex and striatum, suggesting that the expression and upregulation of GPNMB and galectin-3 in microglia is related to myelin and white matter.

Importantly, myelin basic protein (MBP), a major component of white matter, is decreased in Grn−/− mouse brain. Furthermore, modules enriched for oligodendrocyte proteins (M19, p = 0.033) and neuronal and synaptic proteins (M5, p = 0.002) are not significantly decreased until 19-months of age in Grn−/− mouse brain, indicating that synaptic and neuronal loss and demyelination are a late-stage consequence of Grn deficiency. Our proteomics data is supported by a previous report that found defective myelination in the cerebral cortex of Grn−/− mice [108]. Our discovery that GPNMB and galectin-3 are elevated in the white matter of frontal lobe of FTD-GRN cases provides additional clinical relevance suggesting alterations of these proteins may contribute to neurodegeneration.

Intriguingly, demyelination that is observed as white matter hyperintensities (WMH) on MRI brain scans is a frequent and specific occurrence in FTD cases caused by GRN mutations [20, 107, 128]. Our data provide additional support to the idea that FTD-GRN cases are especially vulnerable to demyelination and loss of white matter, although the exact mechanism is unclear. One possibility is that aberrant microglial activation due to PGRN deficiency, caused by lysosome dysfunction and protein aggregation, leads to phagocytosis, synaptic pruning, and de-myelination that eventually manifests as white matter damage and WMH. Intriguingly, microglia expressing either GPNMB or galectin-3 have been implicated in the process of myelin phagocytosis and demyelination [46, 69, 109]. Taken together, we find that increases in microglial GPNMB and galectin-3 levels are correlated with demyelination. Currently it is unclear if GPNMB and galectin-3 upregulation is a cause or consequence of this process.

Lack of specific and sensitive biomarkers are another roadblock in the development of therapies for FTD [40]. Importantly, appropriate biomarkers are useful for monitoring disease progression as well as assessing the efficacy of potential drugs. Elevated levels of neurofilament light chain (Nfl) in CSF and plasma are one promising biomarker for symptomatic FTD patients that harbor mutations in GRN, C9orf72, or MAPT [118]. However, Nfl is not specific to FTD-GRN and is increased in several other neurodegenerative diseases [124]. In this study, we report our finding of elevated levels of GPNMB in aged Grn−/− mouse plasma as well as CSF from human FTD patients with GRN mutations. Previous reports found that GPNMB was elevated in the serum of type I Gaucher disease [138], but not significantly different in AD patients [51], compared to healthy controls. Because GPNMB levels were only increased in CSF from GRN mutation carriers, but not C9 or MAPT cases, GPNMB levels could serve as a biomarker to differentiate between FTD caused by GRN mutantions or other FTD genes.

It is currently unlcear why GPNMB is elevated in the microglia of Grn−/− mice and human FTD-GRN patients. One intriguing possibility is that upregulation of GPNMB expression is driven by lysosome dysfunction. This idea is supported by previous reports that lysosomal stress, induced by chemical inhibition of lysosome acidification or function, causes upregulation of GPNMB in macrophages [34, 111]. GPNMB is also elevated in the substantia nigra of patients with Parkinson's disease [75], a neurodegenerative disease increasingly linked to lysosome dysfcuntion [56, 83, 123]. Moreover, chemical [75] or genetic inhibition [61] of β-glucocerebrosidase (GBA; GCase) activity leading to the accumulation of glucosylceramides also causes increased expression of GPNMB. Progranulin deficiency reduces glucocerebrosidase activity [116, 134] suggesting that the accumulation of glucosylceramide or other sphingolipids could be a proximal cause of GPNMB upregulation in the Grn−/− mouse brain, an idea that needs further investigation. Although the precise mechanism that causes GPNMB upregulation in progranulin deficiency is unclear, our data suggest that measurement of GPNMB levels in the CSF could be used to monitor changes in microglial activation and response to therapies in FTD-GRN patients, similar to substrate reduction therapy in lysosome storage disorders [71, 78, 119]. One limitation of our data is a small sample size and lack of longitundal testing. Thus, further studies are necessary to investigate the utility, specificity, and sensitivity of GPNMB as a biomaker in FTD and related neurodegenerative diseases. Moreover, it will be important to determine if GPNMB and galectin-3 expression in microglia is deleterious, which would open a new therapeutic target for FTD and other diseases with PGRN deficiency.

Conclusion

Our results demonstrate the utility of a systems biology approach in understanding a complex disease like FTD. We were able to relate changes in the Grn−/− mouse brain proteome to known phenotypic signatures of FTD. Further analysis of these proteomic changes across age also provided insight on the mechanism(s) in which neurodegeneration occurs as result of PGRN deficiency. We identified novel proteins in the Grn−/− mouse proteome that are decreased at 3-months, which suggest an impairment of lysosomal metabolism of lipids, including sphingolipids, which are particularly important for neuronal survival [2, 14]. Lysosomal dysregulation is exacerbated with age in the Grn−/− mouse brain leading to neuroinflammation, synaptic loss, and decreased markers of oligodendrocytes, myelin, and neurons. For the first time, we identified increased levels of two proteins, galectin-3 and GPNMB, which have not been linked to FTD or PGRN deficiency previously and may serve as novel biomarkers or drug targets. Previous data demonstrate that upregulation of GPNMB and galectin-3 in microglia can be beneficial or harmful depending on the context, timing, and disease [12, 15, 16, 62, 109]. Further studies are necessary to understand the contribution of GPNMB and galectin-3 to FTD and related neurodegenerative disease. In summary, our findings support the idea that insufficiency of PGRN and granulins in humans cause FTD through lysosomal dysfunction and neuroinflammation and suggest novel therapeutic approaches.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1. Compilation of multiple supplementary tables. Table S1 is a list of cell type-specific protein markers used to identify enrichment of cell types in WGCNA modules. Table S3 is a summary of differential protein expression in Grn−/− (KO) compared to Grn+/+ (WT) mouse brain. Table s4 is a compilation of proteins identified in mouse brain proteome and their correlation to WGCNA modules. Table S5 is a summary of the enrichment of Gene Ontology (GO) terms for each module in WGCNA network.

Additional file 2. Table S2 summarizing the neuropathological, clinical diagnosis, age, sex, and other characterizes of human post-mortem samples used for immunostaining and ELISA.

Additional file 3. Compilation of multiple supplementary figures (S1–S7). Fig. S1 is a two-color heatmap showing the relationship between WGCNA modules and the bicor correlation of age. Fig. S2 contains multiple Box plots of WGCNA modules (M1, M2, M4, M8, M9, M10, M11, M12, M13, M14, M15, M17, M18, M20, M21, M22, M23, M24, M25, and M26). Fig. S3 displays Igraphs of modules (M3, M5, M6, M7, M16, and M19) that are associated with knockout (Grn−/−) status and corresponding gene symbols as nodes. Fig. S4 displays Igraphs of modules (M1, M2, M4, M8, M9, M10, M11, M12, M13, M14, M15, M17, M18, M20, M21, M22, M23, M24, M25, and M26 modules) associated with knockout (Grn−/−) status and corresponding gene symbols as nodes. Fig. S5 summarizes the gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of proteins in M1, M2, M4, M8, M9, M10, M11, M12, M13, M14, M15, M17, M18, M20, M21, M22, M23, M24, M25, and M26 modules. Light-green bars: biological process, light-blue bars: molecular function, brown-bars: cellular component. Fig. S6 is an immunoadsorption validation experiment demonstrating an anti-human GPNMB antibody binds antigen specifically on human brain sections. Fig. S7 GPNMB immunostaining was performed on frontal lobe tissue sections from four FTD-GRN patients.

Acknowledgements

Samples from the Advancing Research and Treatment for Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration (ARTFL) study and the Longitudinal Evaluation of Familial Frontotemporal Dementia Subjects (LEFFTDS) study were obtained through the National Centralized Repository for Alzheimer Disease and Related Dementias (NCRAD), which receives government support under a cooperative agreement Grant (U24 AG21886) awarded by the National Institute on Aging (NIA), were used in this study. The Advancing Research and Treatment for Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration (ARTFL) study receives support through a U.S Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS)/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) Grant U54NS092089. The Longitudinal Evaluation of Familial Frontotemporal Dementia Subjects (LEFFTDS) Study was made possible through the support of the U.S Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and the National Institute on Aging (NIA)/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) Grant U01AG045390. We thank the staff and investigators of the study as well as the participants and their families, whose help and participation made this work possible. Human biological samples and associated data were obtained from the Emory Neuropathology Core (P30 NS055077). This work was supported by P30-NS055077 to the Neuropathology/Histochemistry core of the Emory NINDS Neurosciences Core Facility, AG025688 to Emory’s Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, an Emory University Research Committee Grant (T.K), National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants (R01NS093362, R01NS105971), a New Vision Award (Donors Cure Foundation), an Emory Alzheimer's Disease Center Pilot Grant P50AG025688, the Alzheimer's Drug Discovery Foundation, the Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration (ADDF/AFTD), the Bluefield Project to Cure Frontotemporal Dementia, and the BrightFocus Foundation to TK.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: [MH, CJH, NTS, TK]; Methodology: [MH, EM, ED, DMD, CJH, NTS, TK]; Formal analysis and investigation: [MH, EM, ED, PM, QD, GT, CJH]; Resources: [MG, DD]; Writing—original draft preparation: [MH, EM, TK]; Writing—review and editing: [MH, EM, ED, PM, CJH, NTS, TK]; Funding acquisition: [TK]; Supervision: [TK]. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Analysis of the proteomic data generated during this study are included in this published article and electronic supplementary files. The raw proteomic datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and will be uploaded to a central publicly available data repository.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal procedures and studies were reviewed and approved by the institutional animal care and use committee (IACUC) at Emory University. Human biological samples were obtained with Institutional Review Board approval.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Patent pending related to this work entitled “Methods to treat neurodegeneration with granulins” to TK. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s40478-020-01037-x.

References

- 1.Ahmed Z, Sheng H, Xu YF, Lin WL, Innes AE, Gass J, Yu X, Wuertzer CA, Hou H, Chiba S, et al. Accelerated lipofuscinosis and ubiquitination in granulin knockout mice suggest a role for progranulin in successful aging. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:311–324. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alessenko AV, Albi E. Exploring sphingolipid implications in neurodegeneration. Front Neurol. 2020 doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allan ERO, Campden RI, Ewanchuk BW, Tailor P, Balce DR, McKenna NT, Greene CJ, Warren AL, Reinheckel T, Yates RM. A role for cathepsin Z in neuroinflammation provides mechanistic support for an epigenetic risk factor in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroinflamm. 2017;14:103. doi: 10.1186/s12974-017-0874-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Almeida MR, Macario MC, Ramos L, Baldeiras I, Ribeiro MH, Santana I. Portuguese family with the co-occurrence of frontotemporal lobar degeneration and neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis phenotypes due to progranulin gene mutation. Neurobiol Aging. 2016;41:200.e201–200.e205. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arrant AE, Onyilo VC, Unger DE, Roberson ED. Progranulin gene therapy improves lysosomal dysfunction and microglial pathology associated with frontotemporal dementia and neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. J Neurosci. 2018;38:2341–2358. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3081-17.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker M, Mackenzie IR, Pickering-Brown SM, Gass J, Rademakers R, Lindholm C, Snowden J, Adamson J, Sadovnick AD, Rollinson S, et al. Mutations in progranulin cause tau-negative frontotemporal dementia linked to chromosome 17. Nature. 2006;442:916–919. doi: 10.1038/nature05016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bang J, Spina S, Miller BL. Frontotemporal dementia. Lancet. 2015;386:1672–1682. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00461-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bateman A, Cheung ST, Bennett HPJ. A brief overview of progranulin in health and disease. Methods Mol Biol. 2018;1806:3–15. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8559-3_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beel S, Moisse M, Damme M, De Muynck L, Robberecht W, Van Den Bosch L, Saftig P, Van Damme P. Progranulin functions as a cathepsin D chaperone to stimulate axonal outgrowth in vivo. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26:2850–2863. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]