Abstract

Objectives:

The incidence of atrial fibrillation (AF) in patients over 75-years of age is expected to increase, and it’s treatment remains challenging. This study evaluated the impact of age on the outcomes of surgical ablation (SA) of AF.

Methods:

A retrospective review was performed of patients who underwent the Cox-Maze IV procedure (CMP-IV) at a single institution between 2005 and 2017. The patients were divided into a younger (age<75,n=548) and an elderly cohort (age≥75,n=148). Rhythm outcomes were assessed at 1 year and annually thereafter. Predictors of first atrial tachyarrhythmias (ATAs) recurrence were determined using Fine-Gray regression, allowing for death as the competing risk.

Results:

The mean age of the elderly group was 78.5 ± 2.8 years. The majority of patients (423/696, 61%) had non-paroxysmal AF. The elderly patients had a lower BMI (P<0.001) and higher rates of hypertension (P=0.011), previous myocardial infarction (P=0.017), heart failure (P<0.001), and preoperative pacemaker (P=0.008).Postoperatively, the elderly group had a higher rate of overall major complications (23%vs14%, P=0.017) and 30-day mortality (6%vs2%, P=0.026). The percent freedom from ATAs and antiarrhythmic drugs (AADs) was lower in the elderly patients at 3 (69%vs82%, P=0.030) and 4 years (65%vs79%, P=0.043). By competing risk analysis, the incidence of first ATAs recurrence was higher in elderly patients (33%vs20% at 5 years; Gray’s test, P=0.005). On Fine-Gray regression adjusted for clinically relevant covariates, increasing age was identified as a predictor of ATAs recurrence ((SHR) 1.03, 95% CI (1.02,1.05), P<0.001).

Conclusions:

The efficacy of the CMP-IV was worse in elderly patients, however the majority of patients remained free of ATAs at 5 years. The lower success rate in these higher risk patients should be considered when deciding to perform SA.

Keywords: Surgical Ablation, Cox Maze Procedure, Atrial Fibrillation, Elderly, Long-term Outcomes

Category: Adult, Acquired Cardiovascular Disease

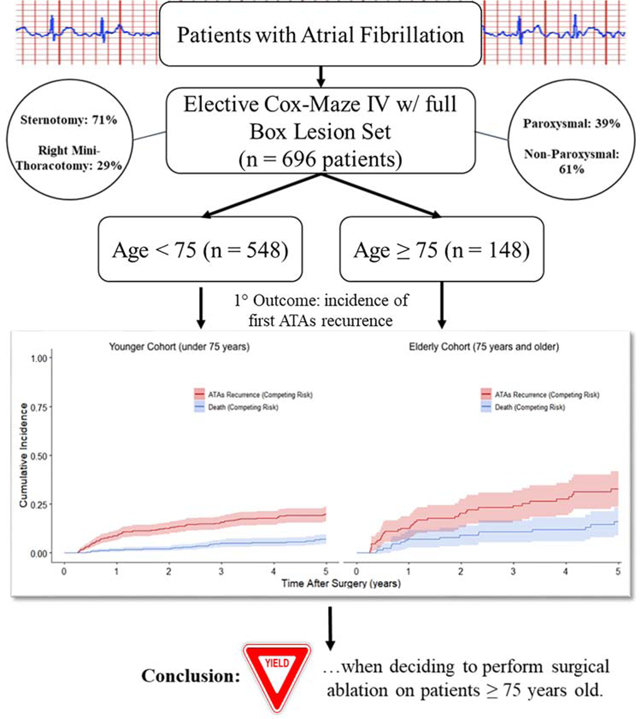

Graphical Abstract

Central Message

The CMP-IV was not as effective in treating atrial fibrillation in elderly patients (age≥75 years) when compared to younger patients. Overall perioperative morbidity was higher in the elderly group.

Central Picture

Central Picture Legend – 5-year survival free of atrial tachyarrhythmias recurrence for young (<75) & elderly (≥75)

Background

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia in the United States, and its prevalence is expected to double by the year 2050 [1]. This increase is not only seen in the general population, but also in a growing number of elderly patients [2]. Age is a known risk factor in the development of AF and contributes to the significant morbidity and mortality of the disease, especially stroke and thromboembolic events [3].

The treatment of elderly patients with AF remains a challenge due to concurrent morbidities and age-related physiological changes. Antiarrhythmic medications may not be as effective in this aging population. They can result in proarrhythmic events and cause drug interactions [4]. Anticoagulation therapies recommended to prevent the thromboembolic events associated with AF also have a higher risk of major bleeding complications in the elderly [5].

Catheter-based radiofrequency ablation (RFA) has been shown to be more effective than pharmacologic therapy in the treatment of AF, especially in patients with paroxysmal AF [6,7]. Despite this success, many elderly patients have traditionally been precluded from receiving RFA due to concerns regarding lower efficacy and increased complication rates [8,9]. Recently, several studies have been conducted to examine the efficacy and safety of performing catheter ablations to treat AF in elderly patients. Zado et al. examined three distinct age groups (< 65, 65–74, ≥ 75 years) and found no significant difference in AF control on or off antiarrhythmic drugs (AAD), or an increased rate of major complications with older age after RFA [10]. Other studies have found similar findings, showing no significant difference in efficacy or safety of catheter ablation in elderly patients [11–13].

The surgical treatment of AF, the Cox-Maze procedure in particular, has provided a durable option for the restoration of sinus rhythm among cardiac surgical patients with AF [16]. Few studies examined the efficacy of the CMP in the elderly. This study examined the impact of age on the efficacy of the Cox-Maze IV procedure in the treatment of AF in elderly patients at our center.

Methods

This study was approved by the Washington University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board. Informed consent and permission for release of information was obtained from all patients. The data were prospectively entered into a longitudinal database maintained at our institution, which included preoperative demographic data, operative details, and perioperative results using STS definitions for complications. Rhythm and other follow-up data were prospectively entered into our institutional AF outcomes database. Missing data were entered by contacting patients and referring physicians, as well as chart review.

Patient Population

From January 2005 to December 2017, 819 patients with AF underwent surgical ablation. Patients who underwent a Cox-Maze III procedure, urgent/emergent/salvage procedures, had prior cardiac surgery, and any other or prior surgical ablation techniques that were not a complete Cox-Maze IV procedure were excluded from the study (n = 123). Of the initial patients screened for the study, 696 patients were available for analysis. The remaining patients either underwent biatrial CMP-IV (n = 636) or a left-sided Cox-Maze lesion set (n=60). The patients were subsequently divided into two cohorts based on their age at the date of surgery: age < 75 (n = 548) and age ≥ 75 (n = 148). Preoperative patient characteristics and perioperative outcomes were evaluated and compared between the cohorts.

Follow-Up and Postoperative Care

Patients underwent follow-up at 3, 6, and 12 months, and annually thereafter. At each follow-up visit, patients underwent history and physical evaluations and electrocardiograms (ECGs). Routine prolonged monitoring was initiated in 2006 and included 24-hr Holter monitoring, pacemaker interrogation, or implantable loop recording. During the study, 89% (620/696) of patients underwent prolonged monitoring during their follow-up. Recurrence was defined as any episode of atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, or atrial tachycardia lasting longer than 30 seconds, in accordance with the 2017 consensus statement from the Heart Rhythm Society [15]. Treatment failure was defined as any patient requiring an interventional procedure for rhythm control after the 3-month blanking period.

All patients received postoperative antiarrhythmic and anticoagulation drugs unless contraindicated [16]. Postoperative atrial tachyarrhythmias (ATAs) unresponsive to antiarrhythmic drugs (AADs) were cardioverted prior to discharge unless contraindicated. The primary contraindication to cardioversion was a documented clot in the left atrial appendage. Patients with persistent bradycardia due to junctional rhythm were followed for 5–7 days to allow for sinus node recovery. A dual chamber pacemaker was inserted if the patients remained in symptomatic bradycardia after this time. Patients in normal sinus rhythm two to three months postoperatively had their AADs discontinued. Anticoagulation was discontinued between three and six months if the patient was free from ATAs on prolonged Holter monitoring, and had no evidence of atrial stasis or thrombus on transthoracic echocardiograms. Anticoagulation was discontinued irrespective of the patients’ CHA2DS2-VASc score [19]. The average follow-up time was 3.4 ± 1.6 years (median 3.8 years, [2.0,5.0]). At 1 and 5 years, 78% (499/636) and 59% (205/350) of patients available for follow-up had documented rhythm and AAD data, respectively (Data Supplement, Table 5 and 6).

Table 5.

Univariable and Multivariable Predictors of First ATAs Recurrence up to 5 Years After CMP-IV (Fine-Gray Regression)

| Variable | Univariable Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-Value | Subdistribution Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P-Value | Subdistribution Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | |

| Age (years) | <0.001 | 1.03 (1.02, 1.05) | 0.021 | 1.03 (1.00, 1.05) |

| Gender | 0.520 | 1.12 (0.79, 1.59) | 0.550 | 1.15 (0.73, 1.80) |

| Race (Caucasian) | 0.310 | 1.66 (0.62, 4.43) | 0.600 | 1.32 (0.47, 3.69) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.220 | 0.98 (0.96, 1.01) | 0.360 | 0.98 (0.95, 1.02) |

| Diabetes | 0.400 | 1.21 (0.78, 1.87) | 0.430 | 1.24 (0.73, 2.08) |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.450 | 0.87 (0.62, 1.24) | 0.059 | 0.68 (0.45, 1.02) |

| Hypertension | 0.370 | 1.19 (0.81, 1.77) | 1.000 | 1.00 (0.65, 1.54) |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | <0.001 | 2.57 (1.67, 3.96) | 0.005 | 2.03 (1.24, 3.31) |

| Stroke | 0.750 | 0.90 (0.48, 1.69) | 0.510 | 0.79 (0.39, 1.59) |

| Myocardial Infarction | 0.500 | 1.22 (0.69, 2.16) | 0.480 | 1.26 (0.67, 2.37) |

| NYHA (Class III or IV) | 0.069 | 1.39 (0.97, 1.99) | 0.770 | 1.06 (0.71, 1.60) |

| LVEF (%) | 0.160 | 0.99 (0.98, 1.00) | 0.210 | 0.99 (0.98, 1.01) |

| Chronic Lung Disease (Moderate+Severe) | 0.180 | 0.52 (0.19, 1.37) | 0.056 | 0.37 (0.13, 1.02) |

| Smoker | 0.100 | 1.34 (0.94, 1.91) | 0.081 | 1.42 (0.96, 2.10) |

| Renal Failure | 0.950 | 0.97 (0.37, 2.56) | 0.780 | 0.83 (0.23, 3.03) |

| Renal Failure requiring Dialysis | 0.790 | 1.35 (0.15, 11.9) | 0.370 | 3.07 (0.27, 35.62) |

| Non-Paroxysmal AF | <0.001 | 2.11 (1.42, 3.15) | 0.005 | 1.84 (1.20, 2.82) |

| Length of Time in AF (months) | 0.008 | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.026 | 1.00 (1.00, 1.01) |

| LA Size (cm) | <0.001 | 1.34 (1.15, 1.55) | 0.005 | 1.28 (1.08, 1.53) |

| Pre-operative Pacemaker | 0.210 | 1.37 (0.84, 2.26) | 0.850 | 0.95 (0.54, 1.65) |

| Perfusion Time (minutes) | 0.910 | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.440 | 1.00 (0.99, 1.00) |

| Sternotomy | 0.034 | 1.58 (1.04, 2.42) | 0.460 | 1.22 (0.72, 2.08) |

| Bilateral Maze | 0.590 | 1.21 (0.60, 2.45) | 0.990 | 1.00 (0.50, 1.97) |

| Procedure | ||||

| Post-operative Pacemaker | 0.690 | 1.11 (0.67, 1.83) | 0.960 | 1.01 (0.58, 1.77) |

| Absence of sinus rhythm at discharge | <0.001 | 2.73 (1.80, 4.15) | 0.011 | 1.84 (1.15, 2.95) |

LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA = New York Heart Association; CABG = coronary artery bypass graft

Study Design

Thirty-seven demographic and perioperative variables including complications were compared between the two cohorts. Freedom from ATAs on or off AADs were compared between the elderly and younger patient groups at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 years postoperatively.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation or as a median with interquartile range, as appropriate. Student’s t-test was used to compare means of normally distributed continuous variables, while Mann-Whitney U test was used for skewed distributions. Categorical variables were compared using either χ2 analysis or Fisher’s Exact test. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Composite endpoint survival (freedom from first ATAs recurrence and death) between subgroups delineated by age (<75 years and ≥75 years) was reported as a Kaplan-Meier estimate. The probability of being both alive and ATAs-recurrence free is equivalent to the probability of experiencing neither of the competing risks, as described below [17]. ATAs recurrence was evaluated using competing risk methodology [18]. Gray’s test was used to compare the incidence of first ATAs recurrence between groups. Death during the follow-up period served as the competing risk. Age categorization was informed by CHA2DS2-VASc risk score stratifications and prior studies on atrial fibrillation recurrence after surgical or catheter ablation in the elderly [14,28]. In subsequent analysis, age was treated as a continuous variable. Twenty-six preoperative and perioperative characteristics that were deemed clinically relevant were evaluated using unadjusted univariate and adjusted multivariate Fine-Gray regression to identify predictors of ATAs recurrence. Estimated probability of first ATAs recurrence occurring during the initial five years after CMP-IV was also evaluated by age at the time of surgery. Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 25 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and R 3.6.1 using the cmprsk package (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Patient Demographics

As expected, there were significant preoperative demographic differences between the two cohorts, including age, BMI, rate of NYHA Class III/IV heart failure, prior myocardial infarction, preoperative pacemaker implantation, hypertension, and peripheral vascular disease (Table 1). The overall average age of the entire patient population was 64.2 ± 11.6 years. The mean age of the elderly cohort (age ≥ 75) was 78.5 ± 2.8, compared to 60.3 ± 9.9 years in the younger group (P < 0.001). The majority of patients in the younger and elderly groups were male (340/548 (62.0%) vs 81/148 (54.7%), P = 0.108). The elderly patient group had a significantly lower BMI when compared to the younger patients (27.1 ± 5.4 vs 30.7 ± 7.1, P < 0.001). The elderly patient group had higher rates of New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class III/IV heart failure (103/148 (69.6%) vs 277/548 (50.5%), P < 0.001), prior myocardial infarction (22/148 (14.9%) vs 44/548 (8.0%), P = 0.017), preoperative pacemaker placement (26/148 (17.6%) vs 52/548 (9.5%), P = 0.008), hypertension (117/148 (79.1%) vs 374/548 (68.2), P = 0.011), and peripheral vascular disease (23/148 (15.5%) vs 46/548 (8.4%), P = 0.013). There were no other statistically significant differences in patient characteristics between the two groups, including the incidence of cerebrovascular disease, diabetes, chronic lung disease or renal failure.

Table 1.

Demographic and Patient Characteristics

| Variable | Age < 75 (n = 548) | Age ≥ 75 (n = 148) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (std) | 60.3 (9.9) | 78.5 (2.8) | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (std) | 30.7 (7.1) | 27.1 (5.4) | <0.001 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 340 (62.0) | 81 (54.7) | 0.108 |

| Caucasian, n (%) | 510 (93.4) | 148 (100) | <0.001 |

| Paroxysmal AF, n (%) | 219 (40.0) | 54 (36.5) | 0.450 |

| Non-Paroxysmal AF, n (%) | 329 (60.0) | 94 (63.5) | 0.450 |

| Length of time in AF (months), median [IQR] | 42.0 [12.0,96.0] | 36.0 [9.3,81.8] | 0.742 |

| NYHA class III or IV, n (%) | 277 (50.5) | 103 (69.6) | <0.001 |

| Prior Myocardial Infarction, n (%) | 44 (8.0) | 22 (14.9) | 0.017 |

| LVEF (%), mean (std) | 55.8 (11.8) | 56.2 (10.0) | 0.643 |

| Preoperative PM, n (%) | 52 (9.5) | 26 (17.6) | 0.008 |

| LA diameter (cm), mean (std) | 5.0 (1.1) | 5.1 (1.0) | 0.134 |

| Smoker, n (%) | 205 (37.4) | 61 (41.2) | 0.446 |

| Chronic lung disease, n (%) | 29 (5.3) | 12 (8.1) | 0.236 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 96 (17.5) | 26 (17.6) | 1.000 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 374 (68.2) | 117 (79.1) | 0.011 |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 314 (57.3) | 92 (62.2) | 0.302 |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 46 (8.4) | 23 (15.5) | 0.013 |

| Cerebrovascular disease, n (%) | 82 (15.0) | 30 (20.3) | 0.130 |

| Renal failure, n (%) | 18 (3.5) | 7 (5.1) | 0.450 |

| Dialysis, n (%) | 5 (1.1) | 1 (0.7) | 1.000 |

AF = atrial fibrillation, LA = left atrium, STD = standard deviation, LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction, NYHA = New York Heart Association, PM = pacemaker, BMI = body mass index, CPB = cardiopulmonary bypass, ICU = intensive care unit

Atrial Fibrillation Characteristics

There was no statistically significant difference between the groups in regard to type of atrial fibrillation, paroxysmal (219/548 (40.0%) vs 54/148 (36.5%), P = 0.450) and non-paroxysmal (329/548 (60.0%) vs 94/148 (63.5%), P = 0.450), or preoperative length of time in AF (median 42.0 [12.0,96.0] vs 36.0 [9.3,81.8] months, P = 0.742) as shown in Table 1. The majority (345/423, 81.6%) of the non-paroxysmal group had long-standing persistent AF. There was no difference between the elderly and younger patient cohorts with respect to left atrial diameter (5.1 ± 1.0 cm vs 5.0 ± 1.1 cm, P = 0.134) or left ventricular ejection fraction (56.2 ± 10.0% vs 55.8 ± 11.8%, P = 0.643).

Type of Surgical Procedure

The elderly patient group underwent median sternotomy at a higher rate than the younger patients (123/148 (83.7%) vs 370/548 (67.6%), P < 0.001) as shown in Table 2. A right mini-thoracotomy approach was used on 203 of the total 696 patients (29.2%). Compared to the younger cohort, the elderly group underwent fewer stand-alone Cox-Maze IV procedures (13/148 (8.8%) vs 198/548 (36.1%), P < 0.001). The biatrial lesion set was used more often in younger patients (508/548 (92.7%) vs 128/148 (86.5%), P = 0.021). At our institution, the left-sided only Cox-Maze lesion set is used on a selected group of patients with a LA diameter of less than 5.0 cm, paroxysmal AF, and no evidence of tricuspid valve pathology or right atrial or ventricular enlargement [16]. The majority of all patients in the study underwent concomitant procedures (485/696, 69.7%). Mitral valve operations included patients receiving an MV repair (175/485, 36.1%), MV replacement (89/485, 18.4%), and other operations including AV repair/replacement (105/485, 21.6%) and lone CABG (58/485, 12.0%) (Table 3). All of the patients in our study had excision or exclusion of the left atrial appendage.

Table 2.

Perioperative Outcomes

| Variable | Age < 75 (n = 548) | Age ≥ 75 (n = 148) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sternotomy, n (%) | 370 (67.6) | 123 (83.7) | <0.001 |

| Stand-alone Maze, n (%) | 198 (36.1) | 13 (8.8) | <0.001 |

| Biatrial Maze, n (%) | 508 (92.7) | 128 (86.5) | 0.021 |

| Post op PM, n (%) | 53 (9.7) | 31 (20.9) | 0.001 |

| CPB time (min), mean (std) | 171.3 (46.6) | 193.6 (56.7) | <0.001 |

| Crossclamp time (min), mean (std) | 82.6 (33.9) | 97.3 (31.9) | <0.001 |

| Overall major complication, n (%) | 75 (13.7) | 34 (23.0) | 0.017 |

| Cerebrovascular accident, n (%) | 9 (1.6) | 3 (2.0) | 0.725 |

| Pneumonia, n (%) | 29 (5.3) | 15 (10.1) | 0.037 |

| Mediastinitis, n (%) | 2 (1.2) | 1 (18) | 1.000 |

| Renal failure requiring dialysis, n (%) | 24 (4.4) | 11 (7.4) | 0.381 |

| Intra-aortic balloon pump, n (%) | 17 (3.1) | 6 (4.1) | 0.604 |

| Reoperation for bleeding, n (%) | 20 (5.7) | 8 (6.7) | 0.662 |

| ICU length of stay (hours), median [IQR] | 54 [26,101.5] | 96.7 [48.3,125.9] | 0.073 |

| Hospital length of stay (days), median [IQR] | 8.0 [6.0,12.0] | 12.0 [8.0,16.0] | <0.001 |

| 30 Day Mortality, n (%) | 12 (2.2) | 9 (6.1) | 0.026 |

Overall major complication rate includes pneumonia, cerebrovascular accident, mediastinitis, intra-aortic balloon pump, renal failure requiring dialysis, reoperation for bleeding. AF = atrial fibrillation, LA = left atrium, STD = standard deviation, LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction, NYHA = New York Heart Association, PM = pacemaker, BMI = body mass index, CPB = cardiopulmonary bypass, ICU = intensive care unit

Table 3.

Type of Concomitant Procedures

| Concomitant Operation | Age < 75 (n = 350) | Age ≥ 75 (n = 135) |

|---|---|---|

| MV Repair | 93 (26.6%) | 29 (21.5%) |

| MV Repair + TVR | 11 (3.1%) | 11 (8.1%) |

| MV Repair + AVR | 6 (1.7%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| MV Repair + CABG | 13 (3.7%) | 12 (8.9%) |

| MVR | 45 (12.9%) | 10 (7.4%) |

| MVR + TVR | 10 (2.9%) | 3 (2.2%) |

| MVR + AVR | 8 (2.3%) | 3 (2.2%) |

| MVR+CABG | 3 (0.9%) | 7 (5.2%) |

| CABG | 44 (12.6%) | 14 (10.4%) |

| Other | 117 (33.4%) | 47 (34.8%) |

MV = mitral valve; TVR = tricuspid valve replacement; AVR = aortic valve replacement; CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; MVR = mitral valve replacement.

Perioperative Results

The perioperative outcomes of the young and elderly patient cohorts are summarized in Table 2. Elderly patients had longer cardiopulmonary bypass time (193.6 ± 56.7 min vs 171.3 ± 46.6 min, P < 0.001) and hospital length of stay (median 12.0 days [8.0,16.0] vs 8.0 days [6.0,12.0], P < 0.001), and a trend toward longer ICU length of stay (median 96.7 hours [48.3,125.9] vs 54.0 [26.0,101.5], P = 0.073). In addition, elderly patients were more likely to be discharged in atrial fibrillation (27/148 (18.2%) vs 59/548 (10.8%, P = 0.014).

Major complications were defined as pneumonia, cerebrovascular accident, mediastinitis, intra-aortic balloon pump, renal failure requiring dialysis, and reoperation from bleeding. Elderly patients experienced a higher rate of overall major complications compared to the younger cohort (34/148 (23.0%) vs 75/548 (13.7%), P = 0.017), including a higher rate of pneumonia (15/148 (10.1%) vs 29/548 (5.3%), P = 0.037). Three patients in the elderly group experienced a postoperative cerebrovascular accident compared to 9 (2.0% vs 1.6%, P = 0.725) in the younger group. Cerebrovascular accident was defined as stroke or other thromboembolism occurring outside the 30-day postoperative period. The elderly patient cohort experienced higher rate of postoperative pacemaker placement compared to younger patients (31/148 (20.9%) vs 53/548 (9.7%), P = 0.001). There was no difference in the rate of overall major complications in patients requiring post-operative pacemaker implantation, compared to those who did not (15/84 (18%) vs 94/612 (15%), P = 0.525). However, patients who underwent post-operative pacemaker implantation had an increase in ICU length of stay (98.9 hours [71.3,144.9] vs 57.5 hours [26.5,114.3], P < 0.001) and hospital length of stay (8.0 days [6.0,12.0] vs 14.0 days [11.0,18.8], P <0.001).

Elderly patients had a significantly higher rate of 30-day mortality compared to the younger patients (9/148 (6.1%) vs 12/548 (2.2%), P = 0.026). The causes of 30-day mortality were similar between the two cohorts, and included acute respiratory failure, septic shock, multisystem organ failure, and heart failure. From the 21 patients with documented 30-day mortality, three patients (3/21, 14%) died following discharge. None of the patients who received a post-operative pacemaker with a documented 30-day mortality (0/84 (0%) vs 21/612 (3%), P = 0.096).

Efficacy

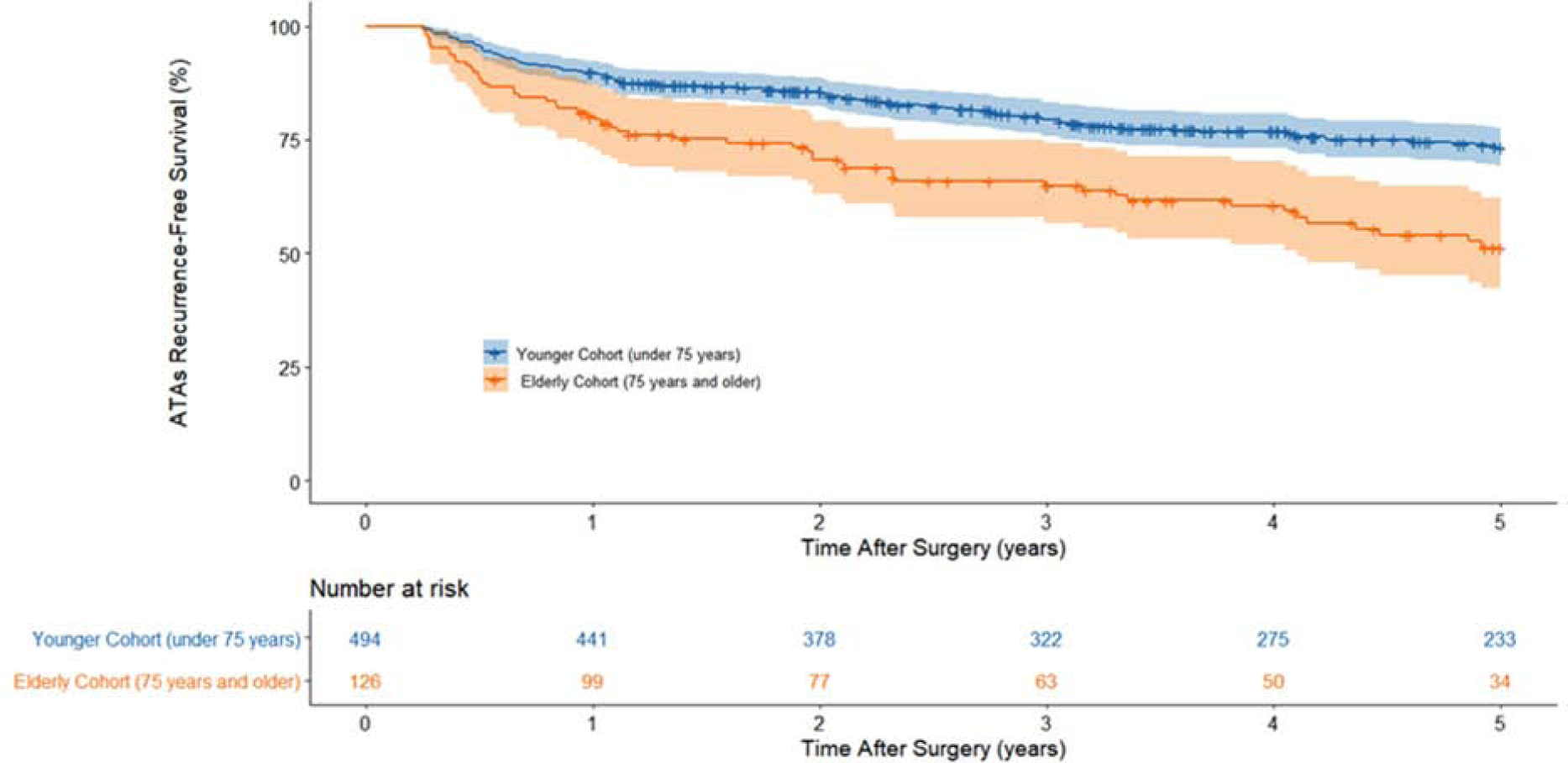

At years 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, the probability of remaining alive and free of ATAs recurrence was estimated to be 90%, 86%, 79%, 77%, and 73%, respectively, in the younger cohort. ATAs recurrence-free survival was estimated to be 80%, 71%, 65%, 60%, and 51% at the same time points in the elderly cohort. The results of the composite endpoint survival analysis can be seen in Figure 1 and Table 4, and are depicted in the graphical abstract (Data Supplement, Figure 5).

Figure 1.

ATAs recurrence-free survival by Kaplan-Meier estimation. The composite endpoint is estimated as the probability of being both alive and having not experienced any recurrence of ATAs. At each timepoint, this composite endpoint survival probability and the cumulative incidences for the competing risks of death and ATAs recurrence sum to one. Percentage of patients estimated to be alive and free of ATAs recurrence at each year can be found in Table 4.

Table 4.

Percentage of patients estimated to be in each state at each year after CMP-IV. Patients were assumed to be in one of three distinct states: alive and free from ATAs recurrence (composite endpoint), alive and having experienced first ATAs recurrence (CIF), or dead before ATAs recurrence (CIF).

| Year | Age < 75 (n = 548) | Age ≥ 75 (n = 148) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alive and free of ATAs recurrence (composite endpoint) | First Documented ATAs recurrence (CIF) | Death (CIF) | Alive and free of ATAs recurrence (composite endpoint) | First Documented ATAs recurrence (CIF) | Death (CIF) | |

| 1 | 90% | 9% | 1% | 80% | 13% | 7% |

| 2 | 86% | 12% | 2% | 71% | 20% | 9% |

| 3 | 79% | 16% | 5% | 65% | 24% | 11% |

| 4 | 77% | 18% | 5% | 60% | 28% | 12% |

| 5 | 73% | 20% | 7% | 51% | 33% | 16% |

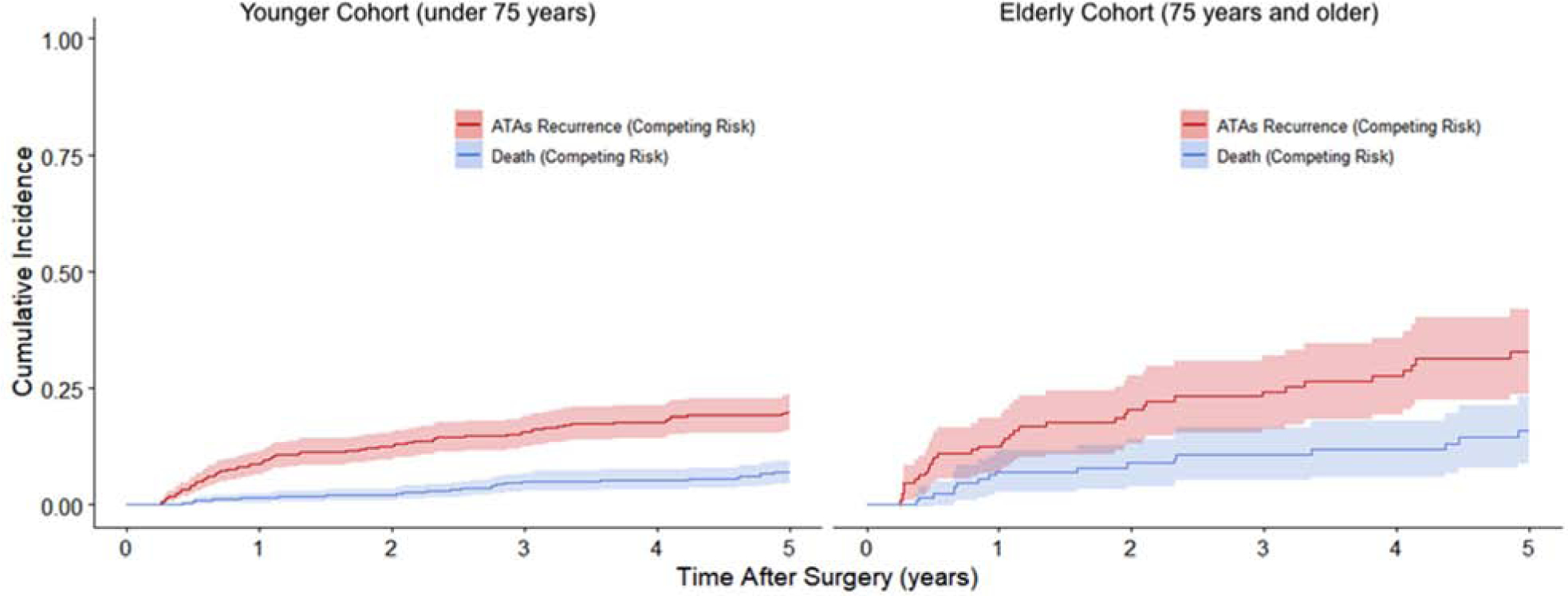

The estimated incidence of first ATAs recurrence at 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 years in the younger patient population was 9%, 12%, 16%, 18%, and 20%, respectively (Figure 2). The incidence of first ATAs recurrence in the elderly patient group was 13%, 20%, 24%, 28%, and 33%, at the same time points (Gray’s test, P=0.005). Among patients who did not experience the competing risk of ATAs recurrence, the elderly group had increased risk of death in the first five years after surgery relative to the younger group (Gray’s test, P=0.002). Estimated mortality at these timepoints was estimated to be 1%, 2%, 5%, 5%, and 7% during years 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively, in the younger patient cohort that remained in sinus rhythm during follow-up. Mortality was estimated as 7%, 9%, 11%, 12%, and 16% in the elderly cohort for those who remained in sinus rhythm at the same timepoints. Estimates of the cumulative incidence functions (CIFs) can be found in Table 4.

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence functions showing the competing risks of ATAs recurrence and death for younger and elderly cohorts in the first five years after undergoing CMP-IV. Percentage of patients estimated to have experienced either first ATAs recurrence or death at each year can be found in Table 4.

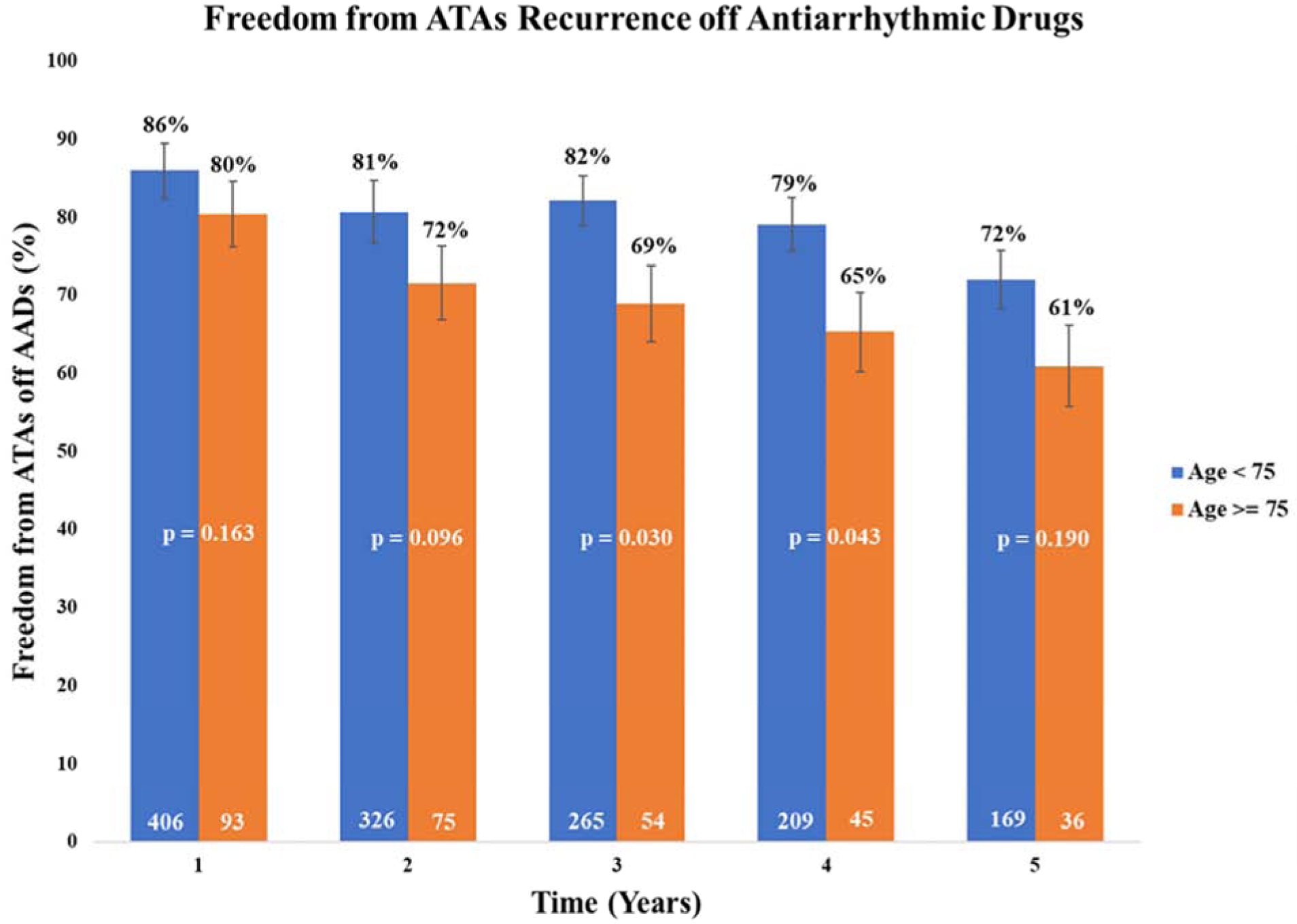

Similar results were found when examining the freedom from ATAs off AADs at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 years in the younger patient group, with freedom of 86%, 81%, 82%, 79%, and 72%, respectively (Figure 3). The elderly patient group showed freedom from ATAs and AADs of 80%, 72%, 69%, 65%, and 61%, at the same time points. These results also showed a significant difference in freedom from ATAs off AADs in the elderly patient group at post-operative years 3 (P = 0.030), and 4 (P = 0.043).

Figure 3.

Five-year follow-up showing freedom from atrial tachyarrhythmia recurrence off antiarrhythmic drugs with 95% confidence intervals for patients age < 75 and ≥ 75 years old. ATA, atrial tachyarrhythmias. AAD, antiarrhythmic drug.

Predictors of Recurrence

Univariable analysis of twenty-six preoperative and perioperative variables was performed as part of an analysis of potential factors contributing to the probability of first ATAs recurrence within five-year follow-up to CMP-IV (Table 5). The following were univariate predictors of first recurrence by Fine-Gray regression: age (subdistribution hazard ratio (SHR) 1.03, 95% CI (1.02, 1.05), P < 0.001), peripheral vascular disease (SHR 2.57, 95% CI (1.67, 3.96), P < 0.001), non-paroxysmal AF (SHR 2.11, 95% CI (1.42, 3.15), P < 0.001), increased time in AF (SHR 1.00, 95% CI (1.00, 1.00), P = 0.008), increased left atrial size (SHR 1.34, 95% CI (1.15, 1.55), P < 0.001), sternotomy (SHR 1.58, 95% CI (1.04, 2.42), P = 0.034), and absence of sinus rhythm at the time of hospital discharge (SHR 2.73, 95% CI (1.80, 4.15), P < 0.001).

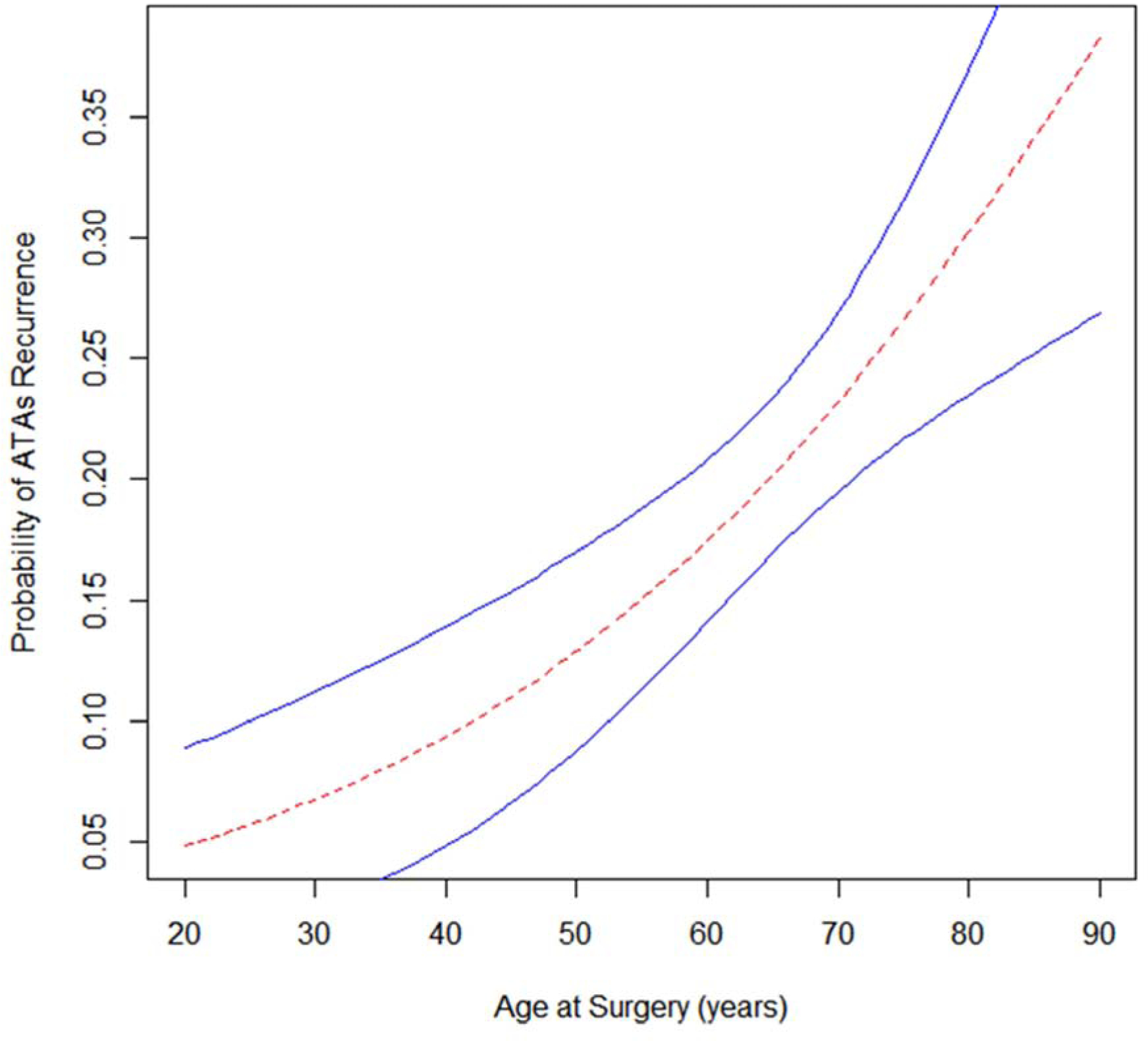

In multivariable Fine-Gray regression adjusted for clinically relevant covariates, the following were identified as predictors of first ATAs recurrence: age (SHR 1.03 95% CI (1.00, 1.05), P = 0.021), peripheral vascular disease (SHR 2.03, 95% CI (1.24, 3.31), P = 0.005), non-paroxysmal AF (SHR 1.84, 95% CI (1.20, 2.82), P =0.005), increased time in AF (SHR 1.00, 95% CI (1.00, 1.01), P = 0.026), increased left atrial size (SHR 1.28, 95% CI (1.08, 1.53), P = 0.005), and absence of sinus rhythm at the time of hospital discharge (SHR 1.84, 95% CI (1.15, 2.95), P =0.011). Receiving the biatrial Cox-Maze procedure was not found to be a predictor of first atrial tachyarrhythmias recurrence up to 5 years following the CMP-IV (univariable SHR 1.21 (0.60,2.45), P = 0.590; multivariable SHR 1.00 (0.50,1.97), P = 0.990). As displayed in Figure 4, analysis showed the probability of experiencing the first ATAs recurrence in the period of five years after CMP-IV increased proportionately with age at the time of surgery.

Figure 4.

Estimated probability of atrial tachyarrhythmias recurrence within the first five years after CMP-IV based on age at the time of surgery. 95% confidence interval bands depicted in blue.

Discussion

The Cox-Maze IV procedure remains the most effective surgical treatment for AF, and is the only surgical procedure to receive an FDA indication for the treatment of AF [20–23]. Since its introduction in 2002, the CMP-IV has shown excellent overall success rates, with lower morbidity and mortality compared to the CMP-III [16]. However, the efficacy of the CMP-IV at late follow-up in elderly patients has remained poorly defined. This study evaluated the impact of age on the efficacy of the CMP-IV.

This study confirmed our group’s previous reports showing the CMP-IV is successful in restoring normal sinus rhythm at early and late follow-up in the general population [16]. However, our results also showed that the CMP-IV was less effective in patients 75-years and older at the time of surgery when compared to younger patients. This study is among the first to report 5-year follow-up in elderly patients who underwent surgical ablation for AF, with freedom from ATAs off AADs in elderly patients of 69%, 65%, and 61%, at 3, 4, and 5 years postoperatively. However, our results are consistent with previously reported 2-year follow-up for the Cox-Maze procedure in the elderly from another center. In a group of 44 patients with mean age of 79.5 years, Ad et al. showed freedom from ATA recurrence after Cox-Maze III/IV procedure of 90%, 85%, and 60% at 6 months, 1 and 2 years, respectively [14]. Our study showed similar results with freedom from ATAs on or off AADs of 88% and 80% at one and two year follow-up for patients older than 75 years. Of interest, very few patients had symptomatic AF recurrence. At five years, only 5 of 205 (2.4%) patients experienced symptomatic recurrence following CMP-IV. Of those five patients, two were older than 75 years at the time of surgery. Thus, most patients were asymptomatic, often with a low burden of AF. Moreover, it is important to emphasize that despite having lower efficacy in the elderly, at one and five years, 88% and 73% of elderly patients were free of recurrent ATAs and AADs. Even more remarkable, only 6% of elderly patients had symptomatic recurrence at 5 years.

Our results were favorable when compared to catheter ablation studies in elderly patients. In a group of 32 patients ≥ 75 years old, Zado et al reported 50% freedom from ATAs off AADs and 73% freedom from ATAs on or off AADs at two year follow-up, with 9% of the elderly patients requiring a second ablation for AF control [10]. Another study including 46 patients ≥ 80 years old reported freedom from ATAs on or off AADs of 75% and under 30%, at 1 and 5 year follow-up respectively after catheter ablation [33]. Our study showed freedom from ATAs on or off AADs of 88% and 73%, at 1 and 5 year follow-up after CMP-IV in patients ≥ 75 years old. Fifty-four percent of patients in that study required a repeat ablation for rhythm control, and a high number (14/46, 32.6%) of deaths and stroke (3/46, 6.5%) were reported [24]. These results are in contrast to our study, which showed a lower mortality rate (9/148, 6.1%) and fewer postoperative strokes (3/148, 2.0%) in elderly patients. None of our patients had a repeat ablation.

In addition to the lower success of the CMP-IV in patients over 75 years old, this study showed an increase in overall complication rates (34/148 (23%) vs 75/548 (14%), P = 0.017). This is not surprising due to the older age and greater number of comorbidities in these patients. However, pneumonia was the only individual morbidity seen to occur in a higher rate in the elderly population (15/148 (10%) vs 29/548 (5%), P = 0.037). Three of the patients in the elderly patient cohort experienced a post-operative stroke or thromboembolic event, which is an important finding given the known morbidity and mortality associated with the complication. Our results were comparable to previously reported studies. [14,25] In addition, elderly patients did not experience an increase in renal failure requiring dialysis or a longer ICU length of stay. These findings are similar to those previously published by Ad and colleagues, as well as the complication rates documented in other studies examining catheter-based ablation of AF in the elderly [6–8,14,25].

Elderly patients experienced a higher rate of post-operative pacemaker placement compared to younger patients (21% vs 10%, P = 0.001). Of note, six of the 31 elderly patients received a postoperative pacemaker due to complete heart block, a sequela more commonly seen due to concomitant surgery and not the Cox-Maze procedure. Patients who received post-operative pacemakers had longer ICU (P < 0.001) and hospital (P < 0.001) length of stay, but no increase in overall major complication rates, when compared to those who did not (18% vs 15%, P = 0.525). Electrophysiological changes in atrial tissue due to increasing age may impair sinus node function and increase the risk of failed sinus node recovery.

As previously mentioned, the treatment of AF in elderly patients remains a challenge due to potentially numerous comorbidities. Our study found an increased rate of heart failure (P < 0.001), prior myocardial infarction (P = 0.017), preoperative pacemaker implantation (P = 0.008), hypertension (P = 0.011), and peripheral vascular disease in the elderly cohort, when compared to younger patients. These comorbidities, some of which are used in mortality risk models following cardiac surgery, likely contributed to our outcome data, which showed a higher 30-day mortality in elderly patients undergoing CMP-IV (9/148 (6.1%) vs 12/548 (2.2%), P = 0.026). However, it has been well documented that adding a CMP-IV did not increase operative risk or the rate of post-operative morbidity and mortality, in patients undergoing concomitant cardiac surgery [26,27,32]. Thus, the increased rate in 30-day mortality seen in the elderly patients in our study is likely due to the complexity of the patients’ clinical condition, not the CMP-IV itself. This is supported by the higher rate of comorbidities that were seen in these patients.

Six predictors of first ATAs recurrence were identified on multivariable Fine-Gray regression, which included age, peripheral vascular disease, non-paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, increased time in AF, increased LA size, and the absence of sinus rhythm at the time of hospital discharge.

These findings are similar to some of the predictors of recurrence that have been reported following catheter ablation [28,29]. It is important to note that patients experiencing ATAs recurrence after initial blanking period (90 days) were considered a failure using Fine-Gray regression analysis. Importantly, the analysis showed older age at the time of surgery increased the probability of experiencing first ATAs recurrence up to five years after CMP-IV.

Age-related structural and electrophysiologic changes in atrial tissue may contribute to the lower efficacy of the CMP-IV in the elderly. Age is known to be associated with regional conduction slowing, diffuse areas of low voltage, impairment of sinus node function, and an increase in atrial effective refractory period [30]. Existing atria structural remodeling and fibrosis also contribute to the propensity to AF in older patients [31]. Despite the proven efficacy of the CMPIV lesion set, which includes complete isolation of the entire posterior left atrium, these underlying changes may alter the ability of the lesions to durably prevent AF initiation and maintenance.

Limitations

Although this is one of the first studies to examine the impact of age on the efficacy of the CMPIV at late follow-up, it is not without limitations. This study was retrospective and non-randomized, thus subjected to inherent selection bias. The operations were performed at a single institution, most of which were completed by a single, highly-experienced surgeon. This may prevent the results from being generalized to all other centers. There was also a relatively small number of patients (n=148) in the elderly cohort, thereby increasing the likelihood of a type II statistical error, when comparing their outcomes to the much larger younger group. An inherent limitation in the study design is the lack of continuous monitoring on all patients, which can lead to interval censoring and underestimation of ATAs recurrence. Though both patient cohorts were well-monitored with prolonged follow-up (205/350, 59% at five years), some patients did not have 24-hour Holter monitoring and instead were assessed by electrocardiogram only. Additional analysis was performed after excluding all data obtained by electrocardiogram within the five-year follow-up, and it showed similar rates in freedom from ATAs on and off AADs in both patient cohorts. Lastly, while the use of Holter monitoring provides a good measure of ATAs recurrence, it does not address the clinical burden of AF. The clinical burden of AF was not examined in this study because any documented recurrence greater than 30 seconds was defined as an indication of CMP-IV failure.

Conclusion

The efficacy of the CMP-IV procedure was lower in patients ≥ 75 years old, with an estimated 51% ATAs recurrence-free survival at five years. There was an increase in overall major complication rates, as well as 30-day mortality, mostly commonly due to multisystem organ failure and heart failure. There was also a 21% incidence of postoperative pacemaker placement. Age, peripheral vascular disease, non-paroxysmal AF, increased LA size, longer preoperative duration in AF, and absence of sinus rhythm at the time of hospital discharge were predictors of first ATAs recurrence up to five years. The lower success rate in these elderly patients should be considered when deciding whether to perform surgical ablation. However, the majority of patients (61%) remain free of recurrent ATAs off AADs at 5 years and very few of the recurrences were symptomatic.

Supplementary Material

Perspective Statement.

The role of surgical ablation in the treatment of AF in patients older than 75 remains controversial. This study examined the efficacy of the Cox-Maze IV procedure in these patients. CMP-IV was less effective in the elderly at 3- and 4-year follow-up, with a higher complication rate compared to the younger cohort. These results should be considered when evaluating older patients for surgical ablation.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health RO1-HL032257 to R.J.D., and R.B.S., T32-HL007776 to R.J.D., A.J.K., R.M.M., and J.L.M., and the Barnes-Jewish Foundation.

Abbreviations and Acronyms:

- AAD

Antiarrhythmic drug

- AF

Atrial fibrillation

- ATAs

Atrial tachyarrhythmias

- CI

Confidence interval

- CIF

Cumulative incidence function

- CMP

Cox-Maze procedure

- OR

Odds ratio

- SA

Surgical ablation

- SHR

Subdistribution hazard ratio

- STS

Society of Thoracic Surgeons

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure:

R.J.D. – Atricure, Inc: Speaker and receives research funding; LivaNova, Inc.: Speaker. Medtronic: Consultant; Edwards Lifesciences: Speaker. Other authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, Chang Y, Henault LE, Selby JV, et al. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the Anticoagulation and risk factors in atrial fibrillation (ATRIA) study. JAMA 2001;285:2370–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colilla S, Crow A, Petkun W, Singer DE, Simon T, Liu X. Estimates of current and future incidence and prevalence of atrial fibrillation in the U.S. adult population. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112(8):1142–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heeringa J, van der Kuip DA, Hofman A, et al. Prevalence, incidence and lifetime risk of atrial fibrillation: the Rotterdam study. Eur Heart J 2006; 27: 949–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Atrial Fibrillation Follow-up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) Investigators. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1825–1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hylek EM, Evans-Molina C, Shea C, Henault LE, Regan S. Major hemorrhage and tolerability of warfarin in the first year of therapy among elderly patients with atrial fibrillation. Circulation 2007;115:2689–2696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amit G, Nyong J, Morillo CA. Efficacy of Catheter Ablation for Nonparoxysmal Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA Cardiol 2017; 2: 812–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilber DJ, Pappone C, Neuzil P, et al. Comparison of antiarrhythmic drug therapy and radiofrequency catheter ablation in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2010; 303: 333–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kusumoto F, Prussak K, Wiesinger M, Pullen T, Lynady C. Radiofrequency catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation in older patients: outcomes and complications. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2009;25(1): 31–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kautzner J, Peichl P, Sramko M, et al. Catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation in elderly population. J Geriatr Cardiol 2017; 14: 563–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zado E, Callans D, Riley M, et al. Long-Term Clinical Efficacy and Risk of Catheter Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation in the Elderly. J Cardiovasc Electrophyiol 2008; 19(6):621–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kis Z, Noten A, Martirosyan M, et al. Comparison of long-term outcome between patients aged < 65 vs. > 65 years after atrial fibrillation ablation. J Geriatr Cardiol 2017; 14: 569–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heeger CH, Bellmann B, Fink T, et al. Efficacy and safety of cryoballoon ablation in the elderly: A multicenter study. Int J Cardiol 2018; 278(2019):108–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhargava M, Marrouche NF, Martin DO, et al. Impact of age on the outcome of pulmonary vein isolation for atrial fibrillation using circular mapping technique and cooled-tip ablation catheter:. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2004; 15:8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ad N, Henry L, Hunt S, Holmes SD, Halpin L. Results of the Cox-Maze III/IV procedure in patients over 75 years old who present for cardiac surgery with a history of atrial ablation. J Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;54:281–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calkins H, Hindricks G, Cappato R, et al. 2017 HRS/EHRA/ECAS/APHRS/SOLAECE expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2017;14(10):e275–e444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henn MC, Lancaster TS, Miller JR, et al. Late outcomes after the Cox maze IV procedure for atrial fibrillation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150(5):1168–76, 1178.e1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Austin PC, Lee DS, Fine JP. Introduction to the analysis of survival data in the presence of competing risks. Circulation. 2016;133:601–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huebner M, Wolkewitz M, Hum S, et al. Competing risks need to be considered in survival analysis models for cardiovascular outcomes. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;153(6):1427–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pet M, Robertson JO, Bailey M, et al. The impact of CHADS2 score on late stroke after the Cox maze procedure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;146(1):85–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prasad SM, Maniar HS, Camillo CJ, et al. The Cox maze III procedure for atrial fibrillation: long-term efficacy in patients undergoing lone versus concomitant procedures. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;126(6):1822–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Damiano RJ, Gaynor SL, Bailey M, et al. The long-term outcome of patients with coronary disease and atrial fibrillation undergoing the Cox maze procedure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;126(6):2016–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schaff HV, Dearani JA, Daly RC, Orszulak TA, Danielson GK. Cox-Maze procedure for atrial fibrillation: Mayo Clinic experience. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;12(1):30–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mccarthy PM, Gillinov AM, Castle L, Chung M, Cosgrove D. The Cox-Maze procedure: the Cleveland Clinic experience. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;12(1):25–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bunch TJ, Weiss P, Crandall BG, et al. Long term clinical efficacy and risk of catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation in octogenarians. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2010; 33: 146–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tan H, Wang X, Shi H, et al. Efficacy, safety and outcome of catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation in octogenarians. Int J Cardiol 2010; 145: 147–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saint LL, Damiano RJ, Cuculich PS, et al. Incremental risk of the Cox-Maze IV procedure for patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing mitral valve surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013; 146(5):1072–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ad N, Holmes SD, Pritchard G, Shuman DJ. Association of operative risk with the outcome of concomitant Cox Maze procedure: a comparison of results across risk groups. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014; 148(6):3027–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Letsas K, Efremidis M, Giannopoulos G, et al. CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores as predictors of left atrial ablation outcomes for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2014;16:202–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heist E, Chalhoub F, Barrett C, et al. Predictors of Atrial Fibrillation Termination and Clinical Success of Catheter Ablation of Persistent Atrial Fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2012; 110:545–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kistler PM, Sanders P, Fynn SP, et al. Electrophysiologic and electroanatomic changes in the human atrium associated with age. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:109–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andrade J, Khairy P, Dobrev D, Nattel S. The clinical profile and pathophysiology of atrial fibrillation: relationships among clinical features, epidemiology, and mechanisms. Circ Res. 2014;114:1453–1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Badhwar V, Rankin JS, Ad N, et al. Surgical Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation in the United States: Trends and Propensity Matched Outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017; 104(2):493–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bunch T, May H, Bair T, et al. The Impact of Age on 5-Year Outcomes after Atrial Fibrillation Catheter Ablation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2016;27(2):141–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.