Abstract

Background:

Racial/ethnic minorities experience a greater burden of mental health outcomes compared to White adults in the United States. The Collaborative Care model is increasingly being adopted to improve access to services and to promote diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric diseases. This systematic review seeks to summarize what is known about Collaborative Care on depression outcomes for racial/ethnic minorities in the United States.

Methods:

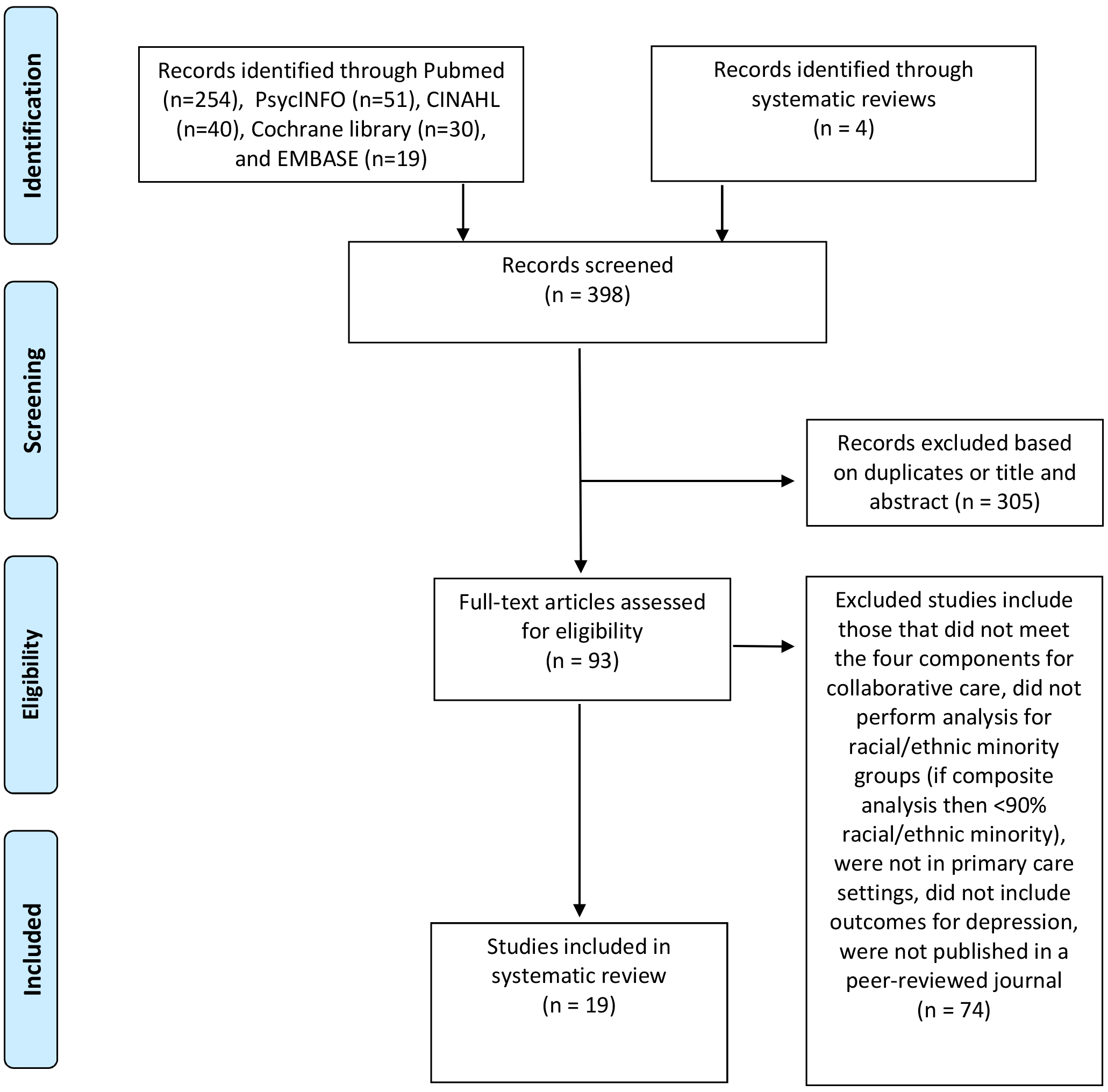

This review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses method. Collaborative care studies were included if they comprised adults from at least one racial/ethnic minority group, were located in primary care clinics in the U.S., and had depression outcome measures. Core principles described by the University of Washington Advancing Integrated Mental Health Solutions Center were used to define the components of Collaborative Care.

Results:

Of 398 titles screened, 169 full-length articles were assessed for eligibility, and 19 studies were included in our review (10 randomized controlled trials, 9 observational). Results show there is potential that Collaborative Care, with or without cultural/linguistic tailoring, is effective in improving depression for racial/ethnic minorities, including those from low socioeconomic backgrounds.

Conclusions:

Collaborative Care should be explored as an intervention for treating depression for racial/ethnic minority patients in primary care. Questions remain as to what elements of cultural adaptation are most helpful, factors behind the difficulty in recruiting minority patients for these studies, and how the inclusion of virtual components changes access to and delivery of care. Future research should also recruit individuals from less studied populations.

Keywords: Collaborative Care, Depression, Racial/Ethnic Minority, Systematic Review

Introduction

Racial and ethnic minorities experience a greater burden of mental health problems compared to White adults in the United States. While the prevalence of mental health disorders is similar among White and non-White adults, disparities in access and utilization of mental health services persist.1 The reasons for reduced service use are many including lack of insurance,2 language and communication barriers,3 and perceived stigma.4 When minority patients present to mental health care, there is evidence they receive lower quality of care and have worse outcomes.5 The full implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act has worked to decrease some of these disparities by increasing access to behavioral health care in primary care settings. Although there exist many forms of integrated care models, few have demonstrated effectiveness in addressing minority mental health disparities in clinical settings.

One way of addressing the mental health needs of the general population in the U.S. is through Collaborative Care, a well-studied health care delivery model based in primary care settings.6 Collaborative Care is a patient-centered and team-based system of care that aims to improve mental health outcomes through measurement-based care. It relies on the use of registries to ensure that patients with depressive disorders are improving on measures such as the PHQ-9.7 In this model, a behavioral care manager provides brief psychological interventions such as problem-solving treatment, motivational interviewing, and behavioral activation to patients.8 In addition, the care manager reviews cases from the registry on a regular basis with a consult psychiatrist, who provides recommendations to the primary care team on the management of these patients.9 To date, past systematic reviews have failed to describe Collaborative Care depression outcomes for racial/ethnic minorities. This model of care may require adaptations to maximize its chances for improved depression outcomes in these populations. The primary aim of this study is to examine the evidence for Collaborative Care for racial/ethnic minorities in the U.S in improving depression measures. Our findings may help inform the implementation of integrated care programs with the goal of reducing mental health care disparities for minority populations.

Materials and Methods

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) method.10 We searched PubMed, PsycINFO, EMBASE, CINAHL, and reference lists of key articles (including systematic reviews) for articles published since database inception. For the MEDLINE search, we used the following keywords and their combinations: (minority groups OR ethnic groups OR asian americans OR hispanic americans OR african americans OR native americans) AND (collaborative care OR integrated delivery of health care OR integrated delivery system) AND (depressive disorder OR depressed). We also used the following Mesh words and their combinations: (minority groups OR ethnic groups OR asian americans OR hispanic americans OR african americans OR indians, north american) AND (delivery of health care, integrated) AND (depressive disorder OR depression). These same search terms were used for PsycINFO, CINAHL, and the Cochrane library. We modified the search for EMBASE using the following keywords and their combinations: (minority group OR ethnic group OR asian continental ancestry group OR asian american OR african american OR hispanic OR american indian) AND (collaborative care OR ‘integrated health care system) AND (depression).

Studies were included in this review if they comprised adults (>18 years) from at least one racial/ethnic minority group (defined as >90% of sample if composite analysis), were located in primary care clinics in the U.S. (as this is the primary entry point for many individuals of racial/ethnic minority background), were published in English, and measured depression outcomes quantitatively, as assessed by standardized instruments (e.g. PHQ-9 and CES-D). We used core principles described by the University of Washington Advancing Integrated Mental Health Solutions (AIMS) Center to define the main components of Collaborative Care.11, 12 These principles include 1) patient-centered team care, 2) population-based care, 3) measurement-based treatment to target, and 4) evidence-based care. Articles were excluded if they 1) did not have all 4 components of Collaborative Care as part of the intervention, 2) focused solely on treatment of other psychiatric or medical conditions (e.g. posttraumatic stress disorder, substance use disorders, diabetes), 3) were conducted in a setting that was not limited to primary care (e.g. specialty oncology clinics), 4) did not include outcomes for depression improvement (e.g. purely qualitative or descriptive), 5) if analysis was not broken down by racial/ethnic minority group (if composite analysis, if sample make-up was <90% racial/ethnic minority), or 6) if they were not published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Titles and abstracts were screened for eligibility and the full text of all potentially eligible studies were reviewed by two authors (TW and JH) to assess for relevance to this systematic review. If a consensus could not be reached, the full text article was then reviewed by a third author (HH) to determine eligibility for inclusion. Data from the studies was abstracted and included the following: population studied (e.g. racial/ethnic minority group, age, gender), type of study, clinical setting, diagnostic/screening measure(s) used for depression, whether there was cultural adaptation, and the primary depression outcome.

Results

Of 398 titles screened, 169 full-length articles were assessed for eligibility (93 after duplicates were excluded), and 19 studies were included in our review (Fig 1, PRISMA flow chart). Ten were randomized controlled trials (RCT), and 9 were observational studies (see Tab 1). Almost all studies had participant demographics that were >50% women and two studies13, 14 specifically included only women. Only one study, which recruited participants from the Veterans Administration system, had a sample which was predominantly men.15 The majority of studies included Hispanic adults (11 of 19 studies)13, 14, 16–24 and/or Black adults (10 of 19)14–21, 25, 26 as part or all of their samples. Asian adults (primarily East Asians) were included in 8 studies,14, 16, 17, 19, 27–30 and Native American adults were included in two studies.15, 31 Two studies specifically included individuals with co-morbid medical conditions (i.e. cardiometabolic syndrome19 and type 2 diabetes mellitus24).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart of study selection

Table 1.

When full intervention protocols could not be found (e.g. for studies with sub-analyses based on data from larger studies), the original papers were referred to in assessing whether the intervention met AIMS criteria.

| Author, Year | Setting, Longest Follow-Up Period | Demographics | Cultural and Linguistic Components | Measurement Tool(s) | Comparison Group | Outcome(s) at Longest Follow-up Period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized Controlled Trials | ||||||

| Arean, 2005 | Washington, California, Texas, Indiana and North Carolina 12 months | 1801 older adults age >60 years who met DSM-IV criteria for major depression or dysthymia Ethnic breakdown: 77% Whites, 12% Blacks, 8% Latinos, 3% Other Women: 65% |

None (explicit observation made by authors) | HSCL-20 | Older minority patients in usual care were compared to those in Collaborative Care intervention | Older minorities in intervention group had significantly better depression outcomes than those in usual care (50% vs 18% for treatment response, p < 0.0001), with Blacks having largest improvement |

| Yeung, 2010 | Boston 6 months | 100 Chinese American adults, age >18, with PHQ-9 ≥10 Ethnic breakdown: 100% Chinese American Women: 69% female |

|

HAM-D-17 CGI-S, CGI-I | Chinese Americans receiving Collaborative Care were compared to those receiving usual care | There were no statistically significant differences in treatment outcome between the care management group and physician-care only group; the groups’ respective response rates were 60% and 50%, their remission rates were 48% and 37%, their mean CGI-S scores were 2.7 and 2.5, and their mean CGI-I scores were 2.8 and 2.8 |

| Bao, 2011 | NYC, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh 2 years | 396 adults age >60, English-speaking, had ≥18, and CES-D score >20 Ethnic breakdown: 83% Black, 13% Hispanic, 1% Asian, 3% other Women: 71.6% |

|

HDRS | Patients receiving Collaborative Care were compared to those receiving usual care; also analyzed depression outcomes for White versus minority adults both in Collaborative Care | Descriptive results showed depression improved for patients in both arms. Minority patients under usual care experienced a similar course of depression as White patients. Under intervention, minorities saw slower decline in HDRS in first 4 months. Collaborative Care provided comparable effects between minorities and Whites in the early phase. However, by month 18, it ceased to benefit minorities, whereas for Whites, the intervention effect amounted to a 2.3 reduction in HDRS at month 24 |

| Davis, 2011 | Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi 6 months | 360 veteran adults, age ≥18, with PHQ-9 ≥12 Ethnic breakdown: 75% White, 18% Black, 3% Native American, 3.6% Other Women: 8% |

None reported | HSCL-20 | Patients in telemedicine-based Collaborative Care were compared to those in usual care | Minority individuals had significantly higher rate of response than Whites to collaborative care (42% versus 19%, X^2=8.1, p=0.004) |

| Cooper, 2013 | Maryland, Delaware 18 months | 132 Black adults, age 18–75, with MDD as screened positive using Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), met DSM-IV criteria for MDD in past year, and had symptoms present for at least 1 week in past month Ethnic breakdown: 100% Black Women: 79.6% |

|

CES-D CIDI | Blacks receiving culturally sensitive Collaborative Care were compared to those receiving standard Collaborative Care without cultural adaptation | Both the standard collaborative care group (−9.1, CI 12.8, 5.4) and the culturally sensitive collaborative care intervention group (−12.0, CI 15.7, 8.2) experienced statistically significant reductions in CES-D at 18 months that were clinically meaningful. There were no statistically significant differences in CES-D between groups over the follow-up period. At 12 months, 33% of the culturally sensitive group and 42% of the standard group achieved remission from depression; this difference was not statistically significant (OR 0.97; CI, 0.34, 2.80) |

| Yeung, 2016 | Boston 6 months | 190 Chinese American monolingual immigrant adults with PHQ-9 ≥10 and who met DSM-IV criteria for MDD as diagnosed by Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview Ethnic breakdown: 100% Chinese American Women: 63% |

|

HAM-D-17 CGI-S, CGI-I | Chinese American patients in Collaborative Care were compared to those in usual care | Odds of achieving response and remission significantly greater in intervention versus control group (OR=3.9, 95% CI, 1.9 to 7.8 and OR=4.4, 95% CI, 1.9 to 9.9 respectively) Patients in intervention showed significantly greater improvement over time in HAM-D-17 (p = 0.002), CGI-S (p = 0.003), CGI-I (p = 0.02) |

| Jonassaint, 2017 | Southwestern Pennsylvania 12 months | 590 adults, age ≥18, with PHQ-9 ≥10 Ethnic breakdown: 15% Black, 85% White Women: 94% |

None reported | PHQ-9 | Black patients were compared to White patients, both of whom participated in Collaborative Care with computerized cognitive behavioral therapy “Beating the Blues” | Black participants trended toward a greater decrease in depressive symptoms than Whites (estimated 8-session change −6.6 vs −5.5, p=0.06) |

| Lagomasino, 2017 | Los Angeles 16 weeks | 400 adults, age ≥18, who screened positive for MDD or dysthymia using PHQ-9 (cutoff unspecified) and 2 questions from PRIME-MD Ethnic breakdown: 85% Latino, 4% White, 10% Black, 2% Other Women: 83% |

|

PHQ-9 | Patients in Collaborative Care were compared to those in “enhanced usual care” (ie, received educational pamphlet about depression, letter they could bring to PCP stating they screened positive for depression, list of local mental health resources) | PHQ-9 significantly lower at 16 weeks in intervention group compared to usual care (8.6 vs 13.3, p<.001) |

| Wu, 2018 | LA county 12 months | 1406 adults age ≥18, diagnosed with T2DM, who spoke English or Spanish, with a working phone number Ethnic breakdown: 89% Hispanic Women: 63% |

|

PHQ-9 | Patients receiving collaborative care with technology assistance or Collaborative Care only were compared to those receiving usual care | Compared to physician-supported care only (UC=6.35), care management (SC=5.05, p=0.02) and technology-facilitated care management (TC=5.16, p=0.02) were both significantly associated with decreased PHQ-9 scores. Only technology-facilitated care management was associated with improved depression remission compared to physician-supported care only. No significant differences in depression outcomes between care management and technology-facilitated care management |

| Emery-Tiburcio, 2019 | Chicago 12 months | 250 adults, age ≥60 years, with PHQ-9 score ≥8 Ethnic breakdown: 50% Hispanic, 50% Black Women: 80.4% |

|

PHQ-9 | Patients receiving Collaborative Care plus membership in Generations, an older adult educational activity program, were compared to those receiving only Generations | Significantly more participants in the care management group (69.7%) than physician-care only group (52.1%) had achieved 50% or greater reduction in depressive symptoms (p=0.012) |

| Observational Studies | ||||||

| Alexopoulos, 2005 | New York City, NY; Philadelphia, PA; Pittsburgh, PA 2 years | 396 adults, age ≥60, English-speaking with MMSE >18 and CES-D score >20 Ethnic breakdown: 83% Black, 13% Hispanic, 1% Asian, 3% other Women: 71.6% |

None reported | HDRS | Patients receiving Collaborative Care were compared to those receiving usual care | When remission defined as HDRS<10, care management practices had higher likelihood of remission than practices offering usual care. By 8 months, 43% of patients receiving the care management intervention had achieved remission compared with 28% of patients receiving usual care |

| Huang, 2011 | Western Washington State 1 month | 661 women, age ≥18, who are either pregnant or parenting a child with PHQ-9 score ≥10 Ethnic breakdown: 59.5% Latina, 19.1% White, 11.3% Black, 10.1% Asian Women: 100% |

None reported | PHQ-9 | Women receiving Collaborative Care who identify as non-Hispanic white, black, and Asian were compared to Latina patients | 66% of Latina patients had 50% or greater reduction in PHQ-9 score compared to 53% white, 40% black, and 51% Asian patients (p<0.001). |

| Uebelacker, 2011 | Rhode Island 12 weeks | 38 Hispanic adults, age ≥18 who met DSM-IV criteria for major depression, minor depression, or dysthymia Ethnic breakdown: 100% Hispanic Women: 95% |

|

QIDS-Clinician version CES-D | Patients receiving telephone depression care management were compared to those receiving usual care | No significant difference in QIDS or CES-D scores between patients who received telephone depression care management and those who received usual care only |

| Sanchez, 2012 | Austin, Texas 3 months | 269 adults age ≥18 who screened in for depression using PHQ-9 (cutoff not specified) Ethnic breakdown: 35% non-Hispanic Whites, 55% Hispanics, 10% other Women: 81% |

|

PHQ-9 | Minority groups were compared to non-Hispanic Whites in Collaborative Care intervention | Spanish-speaking Hispanic patients had significantly greater odds of achieving clinically meaningful improvement compared to non-Hispanic whites (odds ratio [OR] = 2.45, 95% CI = 1.214.95; p = .013) |

| Kwong, 2013 | New York City, NY 12 weeks | 57 Asian American adults, age ≥18 with PHQ-9 ≥8 and confirmed with mini international neurop sychiatric interview Ethnic breakdown: 100% Asian American Women: 68% |

|

PHQ-9 | Asian American patients receiving Collaborative Care were compared to Asian American patients receiving physician-only care | No statistically significant difference in reduction in PHQ-9 scores between patients who received care management support and those who received physician only care. |

| Ratzliff, 2013 | Washington state 16 weeks | 345 adults age >18 with PHQ-9 ≥10 Ethnic breakdown: 58% Asian Americans (suspected mostly Chinese and Vietnamese but could not further characterize) Women: 69% |

|

PHQ-9 | Asian American patients in culturally sensitive Collaborative Care clinics were compared to Asian American and White patients in general Collaborative Care clinics (i.e. without culturally sensitive components) | No statistically significant differences among groups for improvement of depressive symptoms |

| Angstman, 2015 | Midwestern United States multisite practice 6 months | 7010 adults, age ≥18 with PHQ-9 ≥10 Ethnic breakdown: 91.8% non-Hispanic white, 2.1% Black, 1.0% Hispanic, 1.7% Asian, 3.4% Other Women: 71% |

|

PHQ-9 MDQ | Patients receiving Collaborative Care were compared to those receiving usual care | Minority patients who received collaborative care had significantly improved outcomes at 6 months with 50.3% reaching remission (vs. 10.2%, P< 0.001) and only 26.6% remaining in persistent depressive state (vs. 63.3%, P< 0.001) compared to those who received usual care. |

| Eghaneyan, 2017 | Urban center in northern Texas 1 year | 45 adult Hispanic women, age >18 who screened positive for depression on PHQ-9 Ethnic breakdown: 100% Hispanic Women: 100% |

|

PHQ-9 | Baseline PHQ-9 scores of Hispanic women were compared to PHQ-9 scores at their last appointment | There was a statistically significant decrease in PHQ-9 score from baseline compared to the last appointment (18.98 vs 14.33, p<0.001). |

| Bowen, 2020 | Rocky Mountain West, Upper Great Plains, Alaska 2 years | 1993 adults age ≥18 Ethnic breakdown: 345 AI/AN patients (17%), 1473 White patients (74%), and 175 Other (e.g. Asian, Black, etc.) patients (9%) Women (of AI/AN group): 71.4% |

|

PHQ-9 | Native American/Native Alaskan patients in Collaborative Care were compared to White patients in Collaborative Care and “Other” (Asian, Black etc.) patients in collaborative care | Native American/Native Alaskan patients were more likely to have depression response compared to White patients (OR = 1.4, CI = 1.1.−1.7) though statistically significant differences between these two groups disappeared after controlling for clinic |

Definition(s): Usual care defined as physician-supported care without case management and with standard referrals to specialist clinic Abbreviations: PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire-9; HDRS = 24-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; HAM-D-17 = 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; CIDI = Composite International Diagnostic Interview; CGI-S = Clinical Global Impression, Severity; CGI-I = Clinical Global Impression, Improvement; HSCL-20 = Hopkins Symptoms Checklist-20; MDQ = Mood Disorders Questionnaire; QIDS = Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology

Length of follow-up ranged from 1 month to 2 years. Screening and measurement tools included the PHQ-9, 24- or 17-item HDRS, CES-D, and HSCL-20. A few other studies also used the QIDS-Clinician Version and sections of the CGI.23, 29, 30 Depression outcomes included treatment response (reduction of symptoms by at least 50%) and remission (score improved to at or below cut-off, e.g. HAM-D <10 or PHQ-9 <5). Other studies also examined the trends for how quickly participants showed an improvement in depressive symptoms.23, 26

Twelve studies (7 RCT and 5 observational) compared Collaborative Care to usual care for minority patients,15–21, 23, 27–30 and 8 of these showed evidence for decrease in depressive symptoms among minority patients receiving Collaborative Care.15–18, 20, 21, 24, 29 Four of these 8 studies included specific cultural and linguistic components as part of the Collaborative Care intervention.20, 21, 24, 29 Of the 4 studies that showed no differences in outcome between collaborative care and usual care, 3 had cultural and linguistic components.23, 27, 30

Five studies (1 RCT and 4 observational) compared minority patients to White patients in collaborative care.14, 22, 26, 28, 31 The RCT and 2 of the observational studies showed better response to depression in minority patients compared to White patients,26,14, 22 one study showed no difference,28 and the last study showed minority patients responded better to Collaborative Care, though this benefit disappeared when the authors controlled for clinic.31 Bao et al.’s 2011 study also evaluated whether Collaborative Care was as effective for improving depression for White adults versus racial/ethnic minority adults. The authors found minority and White adults both experienced improvement of symptoms initially, but this improvement ceased by 18 months for minority adults compared to White adults, who experienced ongoing benefit to 24 months.

The remaining two studies were a RCT comparing minority patients in culturally sensitive Collaborative Care to minority patients in Collaborative Care without cultural components (no difference in outcomes)25 and a prospective study showing minority patients’ responses to collaborative care (trend toward improvement).13

Six of the 10 RCTs in this review incorporated some culturally sensitive component, ranging from providing bilingual educational materials20, 24 and bilingual clinical care staff21 to more intensive adaptations including creating culturally adapted interview protocols29, 30 and using ethnically matched interventionists.25 Of these, 4 studies described improvement in depression outcomes for minority patients in Collaborative Care compared to those in usual care,20, 21, 24, 29 and one described improvement in depression outcomes for minority patients in Collaborative Care with or without culturally sensitive elements.25 For the 4 studies that did not include culturally sensitive measures, there was a mixed description of positive results. Uniquely, the BRIDGE study provided a head-to-head comparison between standard Collaborative Care and culturally sensitive Collaborative Care for Black adults; both groups experienced statistically significant improvement of depression outcomes, though the 2 groups did not differ significantly.25

Of the 9 observational studies, 5 provided a combination of bilingual educational materials, bilingual screening tools, and multilingual clinical staff.13, 19, 22, 23, 27, 28 In one study, bilingual educational materials were the only adaptation used,27 whereas the other 4 had bilingual/bicultural staff. The 4 studies without cultural adaptations all trended toward depression improvement,14, 16, 17 whereas the 5 with adaptations were divided between no difference from usual care23, 27, 28 and improvement.13, 22

Six of the studies in this review included a variety of technological components as part of their Collaborative Care interventions. One used a computerized CBT module,26 another an automated telephone assessment system integrated into the case management registry,24 and another a virtual multidisciplinary team case review.20 The remaining three used telemedicine initiatives for connecting primary care offices with psychiatrists for consultation.15, 28, 29 Results from all 6 studies suggest technology can be effectively implemented to improve depression outcomes for racial/ethnic minorities.

Discussion

There is a robust evidence base that Collaborative Care can improve depression outcomes for individuals, though population samples from these studies are often predominantly White adults. Results from this review show there is potential for Collaborative Care to be effective in improving depression among racial/ethnic minorities and that results can be sustained over time.

The majority of studies included in this review had study populations that were mostly women, reflecting general trends observed in mental health practices that women are more likely to seek and receive mental health care for depression compared to men.32 The results from the study of veterans15 showed minority veterans had higher rates of response to Collaborative Care compared to White veterans, indicating this model may be an intervention to address untreated depression among minority men.33

Examining the recruitment efforts of the included studies raises important considerations of potential barriers to Collaborative Care for racial/ethnic minority populations. Several studies described difficulties recruiting minority patients. In fact, one study initially aimed to be an RCT but because of low recruitment rates had to adjust its design to become an observational study.27 To our knowledge, there is no current literature examining the recruitment of minority patients for Collaborative Care research, though more broadly within mental health research, previous studies have noted the difficulty in recruiting minority subjects.34 Minority adults’ views of what depression is and what causes it (e.g. stress and social factors) may make them less inclined to participate in studies with a focus on medication treatment (versus therapy), as suggested by Bao et al.19 Involving family members may also be important for certain minority groups such as Hispanic Americans, for whom family cohesion and interdependence have been identified as key values.19, 35

It is thus worth noting to what extent, if any, each study incorporated cultural adaptations into their study implementation. These cultural adaptations were targeted toward improving patient-centered communication, which has been shown to improve patient adherence, satisfaction, and mental health outcomes.36 Additionally, interventions that focus on cultural issues aim to increase patient knowledge, decrease barriers to access, and improve provider cultural sensitivity, which are all linked to improved health outcomes.37, 38 However, there is no standard definition of culturally sensitive care; thus, results should be interpreted cautiously. As noted above, some of these cultural adaptations were as minimal as providing bilingual educational materials while others were as intensive as using culturally adapted interview protocols and providing additional training for staff.

Of note, the Cooper study, which compared standard Collaborative Care to a patient-centered culturally-sensitive Collaborative Care model tailored to Black patients,25 highlights the potential for culturally sensitive care to not only focus on language capacity but also incorporate culturally targeted messages that address patient beliefs and attitudes about treatment. Importantly, however, this same study revealed that Black adults benefited from Collaborative Care regardless of whether there was a cultural component, suggesting the cultural component may be secondary to standard implementation of Collaborative Care.

Most RCTs that incorporated a culturally sensitive component showed positive results. The exception to this is Yeung et al.’s 2010 study. The authors of this paper suggest that results may have been confounded by poor response rate and/or inadequate screening measures leading to inclusion of a lesser severity or not clinically depressed cohort, raising questions about whether a higher cut-off point for screening tools (e.g. PHQ-9) should be used.30 The observational studies are more difficult to interpret because conclusions are limited by the overall lower intensity of culturally sensitive components.

These data together suggest Collaborative Care programs targeting racial/ethnic minority patients should focus on implementation of the four core AIMS components and that culturally sensitive adaptations are likely secondary to this. In other words, a high-fidelity, well-implemented Collaborative Care program designed with understanding of and input from the local context will more effectively improve depression in minority populations than a program that only boasts culturally sensitive care.39

In addition to cultural adaptations, telemedicine is another intervention that shows promise in improving access to and outcomes in mental health care.40 Three studies in this review incorporated telemedicine,15, 28, 29 and all showed improvement in depression for racial/ethnic minority patients. Telemedicine has the potential to connect patients to providers who speak the same language or whose facilities have more robust interpreting services. It may also allow patients to speak with providers who are trained to evaluate psychiatric diseases in specific cultural contexts.41 Despite this potential, further investigation of the effectiveness of telemedicine for racial/ethnic minorities is needed.

Socioeconomic differences among racial/ethnic minority groups (especially for White versus non-White groups) may have also played a role in depression outcomes. However, most studies did not comment specifically on income level. It is therefore difficult to draw conclusions about how patients from different socioeconomic classes may have responded to Collaborative Care interventions. A number of studies had samples that were recruited exclusively from clinics serving low-income patients (e.g. public sector clinics), and Collaborative Care seems to have been an effective intervention for these groups; of note, all of these studies included cultural components, ranging from bilingual screening tools to bilingual staff and culturally adapted therapy.20–23 These findings are consistent with previous ones that demonstrate Collaborative Care can have disproportionate benefit to underserved communities and promotes better engagement with care.42

A primary strength of this study is that it followed guidelines described by PRISMA. Although the exclusion of non-U.S. Collaborative Care studies could be viewed as a limitation, the inclusion of studies from non-U.S. countries would not have answered our primary research question focused on examining potential systems of care that could reduce mental health disparities for racial/ethnic minorities in the U.S. As primary care is the entry point to healthcare for many racial/ethnic minority individuals, our review included only studies which implemented the collaborative care model in this setting. However, other evidence suggests Collaborative Care is also effective in specialty care settings.43 Our review spans several studies including different minority groups and captures the most recent literature. This includes the largest Collaborative Care study published earlier this year involving Native American/Alaskan Native individuals,31 a group which has historically been disproportionately underrepresented in mental health research. The variability of geographic locations, ranging from urban community health centers to satellite clinics in suburban or rural areas, is an additional strength of this review. Lastly, although this was not the primary focus of our research project, our review captures the wide range of cultural adaptations that have been implemented in Collaborative Care settings.

Limitations of this review include variability of study duration, comparison groups, and screening/outcome assessments. While all studies were carefully screened to meet the core AIMS components of Collaborative Care, they differed with regards to the frequency of care management follow-up and/or psychiatric case review and member make-up of the interdisciplinary team. Another limitation is the variability of how authors defined culturally sensitive care with clear differences in intensity of delivery. Studies which did not specifically or adequately describe the inclusion of racial/ethnic minorities and/or provide details of the Collaborative Care intervention may have been missed and subsequently not included in this review. Of course, an inherent but important limitation when analyzing pooled data from diverse groups is the difficulty in generalizing results. The needs of individuals, including those belonging to the same racial/ethnic minority group, can vary significantly depending on education level, geographic residence, and socioeconomic status. Whether certain minority populations benefit more or less from Collaborative Care merits additional research. Given the limited number of studies included in this review, we could not pursue this question further.

Conclusion

Results from this review show there is potential that Collaborative Care in primary care settings, with or without cultural/linguistic tailoring, is effective in improving depression for racial/ethnic minority patients, including those from low socioeconomic backgrounds. Positive outcomes can occur in as little as 1 month and persist for up to 2 years. Questions remain as to what elements of cultural adaptation (including screening and monitoring tools) are most helpful in implementing Collaborative Care for minority populations and whether the inclusion of virtual components (e.g. telemedicine, computerized modules) changes access to and delivery of care for racial/ethnic minority populations. Future research should also include less studied populations, including South Asians, Native Americans, Arab Americans, and Multiracial Americans, and whether better outreach methods can be adopted to include men from racial/ethnic minority populations.

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank Marshall Forstein, MD; Amber Frank, MD; Laura Warren, MD; and Jessica Collier for their support of psychiatry residents’ research at Cambridge Health Alliance.

Funding: Karen M. Tabb PhD was supported by the National Institutes of Minority Health Disparities award number L60 MD008481.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Alegria M, Alvarez K, Ishikawa RZ, et al. Removing Obstacles To Eliminating Racial And Ethnic Disparities In Behavioral Health Care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016; 35: 991–999. 2016/June/09 DOI: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alegria M, Cao Z, McGuire TG, et al. Health insurance coverage for vulnerable populations: contrasting Asian Americans and Latinos in the United States. Inquiry 2006; 43: 231–254. 2006/December/21 DOI: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_43.3.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dorsey R, Graham G, Glied S, et al. Implementing health reform: improved data collection and the monitoring of health disparities. Annu Rev Public Health 2014; 35: 123–138. 2013/December/25 DOI: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gary FA. Stigma: barrier to mental health care among ethnic minorities. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2005; 26: 979–999. 2005/November/15 DOI: 10.1080/01612840500280638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tiwari A, Rajan M, Miller D, et al. Guideline-consistent antidepressant treatment patterns among veterans with diabetes and major depressive disorder. Psychiatr Serv 2008; 59: 1139–1147. 2008/October/04 DOI: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.10.113910.1176/ps.2008.59.10.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thota AB, Sipe TA, Byard GJ, et al. Collaborative care to improve the management of depressive disorders: a community guide systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med 2012; 42: 525–538. 2012/April/21 DOI: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL and Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001; 16: 606–613. 2001/September/15 DOI: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang H, Bauer AM, Wasse JK, et al. Care managers’ experiences in a collaborative care program for high risk mothers with depression. Psychosomatics 2013; 54: 272–276. 2012/December/01 DOI: 10.1016/j.psym.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bauer AM, Williams MD, Ratzliff A, et al. Best Practices for Systematic Case Review in Collaborative Care. Psychiatr Serv 2019; 70: 1064–1067. 2019/August/28 DOI: 10.1176/appi.ps.201900085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151: W65–94. 2009/July/23 DOI: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.University of Washington, Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Division of Population Health,. Principles of collaborative care, https://aims.uw.edu/collaborative-care/principles-collaborative-care (2019, accessed 3 Jan 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Psychiatric Association, Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine,. Dissemination of integrated care within adult primary care settings: The collaborative care model. 2016.

- 13.Eghaneyan BH, Sanchez K and Killian M. Integrated health care for decreasing depressive symptoms in Latina women: Initial findings. Journal of Latina/o Psychology 2017; 5: 118–125. DOI: 10.1037/lat0000067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang H, Chan YF, Katon W, et al. Variations in depression care and outcomes among high-risk mothers from different racial/ethnic groups. Fam Pract 2012; 29: 394–400. 2011/November/18 DOI: 10.1093/fampra/cmr108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis TD, Deen T, Bryant-Bedell K, et al. Does minority racial-ethnic status moderate outcomes of collaborative care for depression? Psychiatr Serv 2011; 62: 1282–1288. 2012/January/03 DOI: 10.1176/ps.62.11.pss6211_1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alexopoulos GS, Katz IR, Bruce ML, et al. Remission in depressed geriatric primary care patients: a report from the PROSPECT study. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162: 718–724. 2005/April/01 DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.4.718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Angstman KB, Phelan S, Myszkowski MR, et al. Minority Primary Care Patients With Depression: Outcome Disparities Improve With Collaborative Care Management. Med Care 2015; 53: 32–37. 2014/December/03 DOI: 10.1097/mlr.0000000000000280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arean PA, Ayalon L, Hunkeler E, et al. Improving depression care for older, minority patients in primary care. Med Care 2005; 43: 381–390. 2005/March/22 DOI: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000156852.09920.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bao Y, Alexopoulos GS, Casalino LP, et al. Collaborative depression care management and disparities in depression treatment and outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011; 68: 627–636. 2011/June/08 DOI: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Emery-Tiburcio EE, Rothschild SK, Avery EF, et al. BRIGHTEN Heart intervention for depression in minority older adults: Randomized controlled trial. Health Psychol 2019; 38: 1–11. 2018/November/02 DOI: 10.1037/hea0000684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lagomasino IT, Dwight-Johnson M, Green JM, et al. Effectiveness of Collaborative Care for Depression in Public-Sector Primary Care Clinics Serving Latinos. Psychiatr Serv 2017; 68: 353–359. 2016/November/16 DOI: 10.1176/appi.ps.201600187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanchez K and Watt TT. Collaborative care for the treatment of depression in primary care with a low-income, spanish-speaking population: outcomes from a community-based program evaluation. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2012; 14 2012/January/01 DOI: 10.4088/PCC.12m01385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uebelacker LA, Marootian BA, Tigue P, et al. Telephone depression care management for Latino Medicaid health plan members: a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Nerv Ment Dis 2011; 199: 678–683. 2011/September/01 DOI: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318229d100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu S, Ell K, Jin H, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of a Technology-Facilitated Depression Care Management Model in Safety-Net Primary Care Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: 6-Month Outcomes of a Large Clinical Trial. J Med Internet Res 2018; 20: e147 2018/April/25 DOI: 10.2196/jmir.7692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cooper LA, Ghods Dinoso BK, Ford DE, et al. Comparative effectiveness of standard versus patient-centered collaborative care interventions for depression among African Americans in primary care settings: the BRIDGE Study. Health Serv Res 2013; 48: 150–174. 2012/June/22 DOI: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01435.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jonassaint CR, Gibbs P, Belnap BH, et al. Engagement and outcomes for a computerised cognitive-behavioural therapy intervention for anxiety and depression in African Americans. BJPsych Open 2017; 3: 1–5. 2017/January/07 DOI: 10.1192/bjpo.bp.116.003657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwong K, Chung H, Cheal K, et al. Depression care management for Chinese Americans in primary care: a feasibility pilot study. Community Ment Health J 2013; 49: 157–165. 2011/October/22 DOI: 10.1007/s10597-011-9459-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ratzliff AD, Ni K, Chan YF, et al. A collaborative care approach to depression treatment for Asian Americans. Psychiatr Serv 2013; 64: 487–490. 2013/May/02 DOI: 10.1176/appi.ps.001742012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yeung A, Martinson MA, Baer L, et al. The Effectiveness of Telepsychiatry-Based Culturally Sensitive Collaborative Treatment for Depressed Chinese American Immigrants: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2016; 77: e996–e1002. 2016/August/26 DOI: 10.4088/JCP.15m09952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yeung A, Shyu I, Fisher L, et al. Culturally sensitive collaborative treatment for depressed chinese americans in primary care. Am J Public Health 2010; 100: 2397–2402. 2010/October/23 DOI: 10.2105/ajph.2009.184911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bowen DJ, Powers DM, Russo J, et al. Implementing collaborative care to reduce depression for rural native American/Alaska native people. BMC Health Serv Res 2020; 20: 34 2020/January/15 DOI: 10.1186/s12913-019-4875-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bertakis KD, Helms LJ, Callahan EJ, et al. Patient gender differences in the diagnosis of depression in primary care. J Womens Health Gend Based Med 2001; 10: 689–698. 2001/September/26 DOI: 10.1089/15246090152563579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blumberg SJ, Clarke TC and Blackwell DL. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Men’s Use of Mental Health Treatments. NCHS Data Brief 2015: 1–8. 2015/June/17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iwamasa GY, Sorocco KH and Koonce DA. Ethnicity and clinical psychology: a content analysis of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev 2002; 22: 931–944. 2002/September/07 DOI: 10.1016/s0272-7358(02)00147-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katiria Perez G and Cruess D. The impact of familism on physical and mental health among Hispanics in the United States. Health Psychology Review 2014; 8: 95–127. DOI: 10.1080/17437199.2011.569936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Griffin SJ, Kinmonth AL, Veltman MW, et al. Effect on health-related outcomes of interventions to alter the interaction between patients and practitioners: a systematic review of trials. Ann Fam Med 2004; 2: 595–608. 2004/December/04 DOI: 10.1370/afm.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beach MC, Price EG, Gary TL, et al. Cultural competence: a systematic review of health care provider educational interventions. Med Care 2005; 43: 356–373. 2005/March/22 DOI: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000156861.58905.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fisher TL, Burnet DL, Huang ES, et al. Cultural leverage: interventions using culture to narrow racial disparities in health care. Med Care Res Rev 2007; 64: 243s–282s. 2007/October/19 DOI: 10.1177/1077558707305414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science 2009; 4: 50 DOI: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fortney JC, Pyne JM, Edlund MJ, et al. A randomized trial of telemedicine-based collaborative care for depression. Journal of general internal medicine 2007; 22: 1086–1093. 2007/May/10 DOI: 10.1007/s11606-007-0201-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hilty DM, Ferrer DC, Parish MB, et al. The effectiveness of telemental health: a 2013 review. Telemed J E Health 2013; 19: 444–454. 2013/May/24 DOI: 10.1089/tmj.2013.0075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Katon W, Russo J, Reed SD, et al. A randomized trial of collaborative depression care in obstetrics and gynecology clinics: socioeconomic disadvantage and treatment response. Am J Psychiatry 2015; 172: 32–40. 2014/August/27 DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14020258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ell K, Xie B, Quon B, et al. Randomized controlled trial of collaborative care management of depression among low-income patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 4488–4496. 2008/September/20 DOI: 10.1200/jco.2008.16.6371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]