Abstract

Objective:

Citrullinated proteins are hallmark targets of autoantibodies in rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Our goal was to determine the effect of autocitrullination on the recognition of peptidylarginine deiminase (PAD) 2 and 4 by autoantibodies in RA.

Methods:

Autocitrullination sites in PAD2 and PAD4 were determined by mass spectrometry and literature review. Antibodies against native and autocitrullinated PADs in 184 patients with RA were detected by ELISA. Linear regression, outlier calculations, and competition assays were performed to evaluate antibody reactivity to native and citrullinated PADs.

Results:

Autocitrullination of PAD2 and PAD4 was detected at 48% (16/33) and 26% (7/27) of arginine residues, respectively. Despite robust autocitrullination, autoantibodies bound similarly to native and citrullinated PAD2 or PAD4 (rho=0.9274 and 0.903, respectively; p<0.0001 for both). Although subsets of anti-PAD-positive sera were identified that preferred native or citrullinated PAD2 (40.5 or 4.8%, respectively) or PAD4 (11.7 or 10.4%, respectively), competition assays confirmed that the majority of anti-PAD reactivity was attributed to a pool of autoantibodies that bound irrespective of citrullination status.

Conclusion:

Autocitrullination does not affect autoantibody reactivity to PADs in the majority of patients with RA, demonstrating that anti-PAD antibodies are distinct from anti-citrullinated protein antibodies in their dependence on citrullination for binding.

Keywords: Rheumatoid Arthritis, Autoantibodies, Anti-citrullinated protein antibodies, Peptidylarginine Deiminase, Citrullination, Autocitrullination

Introduction

Peptidylarginine deiminases (PADs) have emerged as key participants in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) due to their ability to generate the hallmark targets of anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPAs)(1). PADs catalyze the posttranslational deimination of peptidylarginine to peptidylcitrulline, creating neoepitopes recognized by ACPAs in approximately 80% patients with RA. Although there are five members of the PAD enzyme family, PAD2 and PAD4 have been most strongly implicated in generating the citrullinated autoantigens targeted in RA. These two PADs are expressed in the synovial tissue and fluid from patients with RA(2–4), and polymorphisms in these genes are independently linked to RA development, primarily in Asian populations(3, 4). PAD2 and PAD4 are also targeted by autoantibodies in 18.5 and 23–45% of RA patients, respectively, and are associated with distinct clinical outcomes(5–8). While PAD2 antibodies are associated with milder disease, PAD4 antibodies are associated with more destructive joint disease.

Although PAD2 and PAD4 have been shown to undergo autocitrullination(9–12), the anti-PAD autoantibodies described to date have been detected using native proteins, and the effect of autocitrullination on PAD immunogenicity is unknown. Since autoantibodies in RA can target both native and citrullinated sequences within the same antigen(13), it is possible that a subset of antibodies specific for citrullinated PADs have gone unnoticed. It is also possible that citrullinated PADs may be recognized by a subset of ACPAs. Both of these possibilities would result in the prevalence of anti-PAD antibodies being vastly underestimated by the use of native proteins as antigens. Since citrullination is a major determinant in the immunogenicity of hallmark autoantigens in RA, we investigated the effect of citrullination on the recognition of PAD2 and PAD4 by RA autoantibodies.

Patients and Methods

Human subjects

Sera from 184 patients with RA from the Evaluation of Subclinical Cardiovascular Disease and Predictors of Events in Rheumatoid Arthritis (ESCAPE RA) cohort(5, 6) and 39 healthy donors from a convenience cohort were obtained under written informed consent approved by the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board.

Native and citrullinated PAD preparation

To generate native and citrullinated antigens, purified human recombinant PADs were initially incubated in the presence of 1mM EDTA or 5mM calcium, respectively, in citrullination buffer (100mM Tris pH 7.6/10mM dithiothreitol (DTT)). However, under these conditions, both native and citrullinated PADs showed appreciable precipitation, which generated inconsistent results in ELISA assays. Different approaches were attempted to generate soluble autocitrullinated PADs, which resulted in the establishment of the following methods for purification and modification. Briefly, BL21(DE3) cells were transfected with pET28a(+) encoding human PAD4 or PAD2 with N-terminal 6×histidine and T7 tags. Protein expression was induced overnight (ON) with 0.4 mM isopropyl-ß-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG) at 16oC. For PAD4, the cells were lysed by sonication in 100mM Tris pH 7.6/10mM DTT/antipain/pepstatin A/leupeptin, and cleared lysate was split and incubated with either 100 μM EDTA or 10mM CaCl2 to generate native and citrullinated PAD4, respectively. After ON incubation at 37oC, precipitated proteins were removed by centrifugation and discarded. The supernatant, containing soluble native or autocitrullinated PAD4, was collected and passed through a 0.2 μm filter. The proteins were then purified using Ni-NTA agarose. For PAD2, the cells were lysed and protein was immediately purified using Ni-NTA agarose. Since the presence of the 6×histidine tag substantially reduced the autocitrullination activity of PAD2, this tag was removed following PAD2 purification using a thrombin cleavage site built into the vector. For this, PAD2 was dialyzed against 50mM Tris pH 7.6/ 200mM NaCl, prior to incubation with thrombin-agarose (Sigma) at room temperature ON. Citrullinated and native PAD2 were then generated by incubation in citrullination buffer with 5mM CaCl2 or 100 μM EDTA, respectively, for 5hrs at 37oC. Precipitated PAD2 was cleared following each reaction by centrifugation. Citrullination status was confirmed by anti-modified citrulline (AMC) immunoblotting (EMD Millipore).

Identification of PAD2 and PAD4 autocitrullination sites by mass spectrometry

Native and autocitrullinated PAD2 or PAD4 proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE followed by staining with GelCode Blue (ThermoFisher). PAD proteins were isolated from the excised gel bands, digested with trypsin (Promega) in 20 mM TEAB, and analyzed by mass spectrometry using an Orbitrap Fusion Lumos Tribrid Mass Spectrometer coupled with the Easy-nLC 1200 nano-flow liquid chromatography system (ThermoFisher), as described in detail in the Supplementary Methods.

Anti-PAD (Native and citrullinated) ELISA and blocking assay

High-binding polystyrene EIA plates (Costar) were coated overnight with 200 ng/well of soluble native or autocitrullinated PAD2 or PAD4 in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) pH 7.4 or PBS alone. ELISAs were then performed as previously described(5), with patient sera diluted 1:250 in 1% milk/PBS/0.05% tween-20 in duplicate. Anti-PAD arbitrary units (AU) were assigned based on a known positive patient serum that was serially diluted and included as a standard on each plate. Average AU were calculated for each serum sample by subtracting the background binding to PBS-coated wells.

For blocking experiments, ELISAs were performed as described above using 1:250 diluted serum that had been pre-incubated with 2 μg of a competing PAD antigen or PBS alone for 1 hour at room temperature with mixing. In one set of experiments sera were incubated with native PAD or PBS and then reactivity to the respective plate-bound citrullinated PAD was determined. In another set of experiments, sera were pre-incubated with citrullinated PAD or PBS before determining reactivity to the corresponding native PAD. The total reactivity to each PAD (“Total PADx AU”) was calculated by adding the binding of unblocked serum to native (natPADx) and citrullinated (citPADx) PAD, where PADx is PAD2 or PAD4 as appropriate. The proportion of antibodies in each serum sample that were specific for native, citrullinated, or both (i.e. indifferent) forms of PAD2 and PAD4 were calculated by the following equations:

Statistical analyses

Anti-PAD AU for native versus autocitrullinated PAD was plotted for each patient and analyzed using simple logistic regression with Spearman’s rho calculation. Bland-Altman plots were constructed to analyze the agreement between the naïve and citrullinated PAD2 and PAD4 ELISAs. The difference in antibody reactivity to native PAD and citrullinated PAD2 or PAD4 was plotted versus the average recognition of the respective native and citrullinated PAD for each patient. Statistical outliers were identified that demonstrated a strong preference for either the native or citrullinated form of each PAD using the combined robust regression and outlier removal (ROUT) method(14). Calculations were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 software or Intercooled STATA12, and a two-tailed alpha=0.05 was used throughout.

Results

PAD2 and PAD4 autocitrullinate

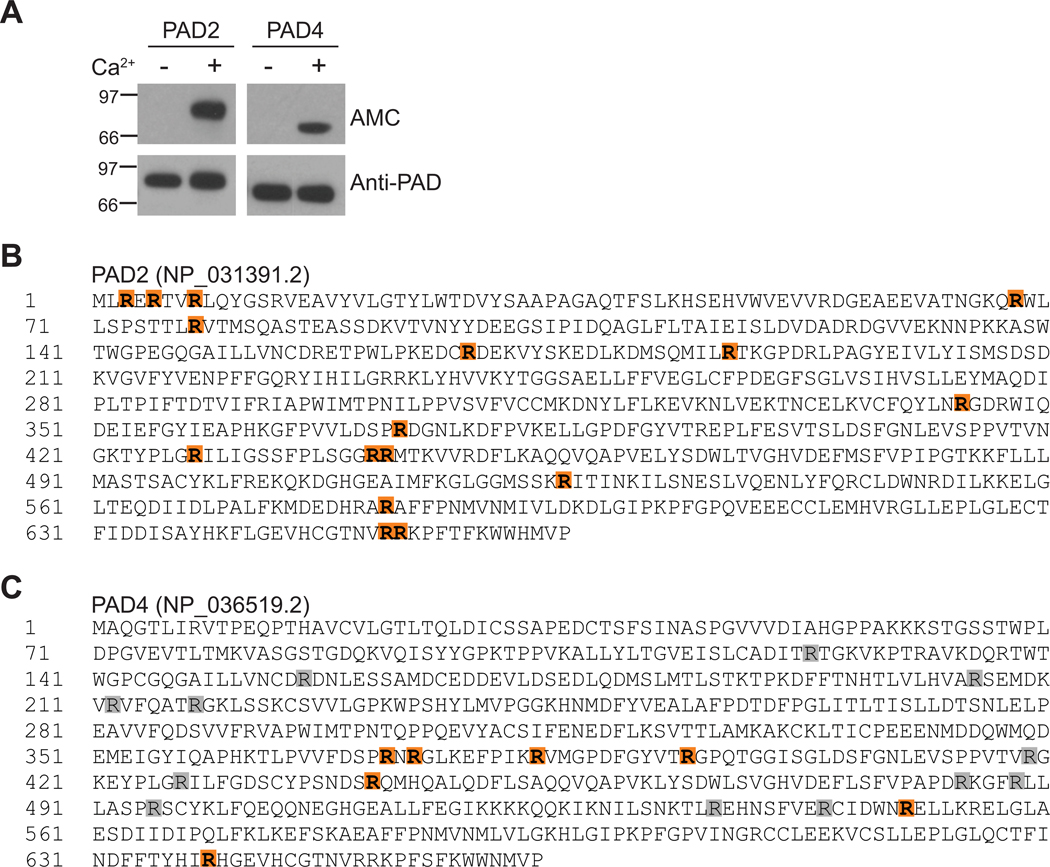

Published studies by our group and others have shown that PAD2 and PAD4 have the capacity to autocitrullinate(9–12) (Figure 1A), but autocitrullination sites in PAD2 have not been mapped. Mass spectrometry analysis of autocitrullinated PAD2 revealed citrullination at R3, R5, R8, R68, R78, R168, R187, R344, R373, R428, R441, R442, R525, R582, R652, and R653 (Figure 1B, Table S1, and Figure S1). This corresponds to 48% (16/33) of the total arginine residues in PAD2.

Figure 1. Citrullination sites in PAD2 and PAD4.

(A) PAD2 and PAD4 autocitrullinate in a calcium-dependent manner as detected by anti-modified citrulline (AMC) immunoblotting. PAD detection by rabbit anti-PAD2 or anti-PAD4 antibodies was included as a loading control. Citrullination sites in autocitrullinated PAD2 (B) and PAD4 (C) were identified by mass spectrometry (orange). (C) Citrullination sites in autocitrullinated PAD4 that have been identified in previously published studies(9–12) are also indicated (gray).

Three groups have previously mapped autocitrullination sites in PAD4 that are generated in vitro and found overlapping, as well as distinct, sites likely driven by differences in citrullination reaction and mass spectrometry conditions(9–11). While the total number of possible PAD4 autocitrullination sites identified to date is 18, representing 67% (18/27) of the total arginine residues in PAD4, only 6–12 autocitrullination cites were identified in each study, suggesting that a subset of arginine residues is modified in any given condition (Figure 1C). In our current study, autocitrullination of PAD4 was detected at R372, R374, R383, R394, R441, R550, and R639 (Figure 1C, Table S2, and Figure S2). These sites overlap with 6 previously identified sites, and include a novel autocitrullination site at R550. Despite 50% sequence identity and 65% homology between PAD2 and PAD4, only 12 arginines are conserved between the two enzymes and, of these, only three are shared autocitrullination sites.

Anti-PAD antibodies bind irrespective of citrullination status

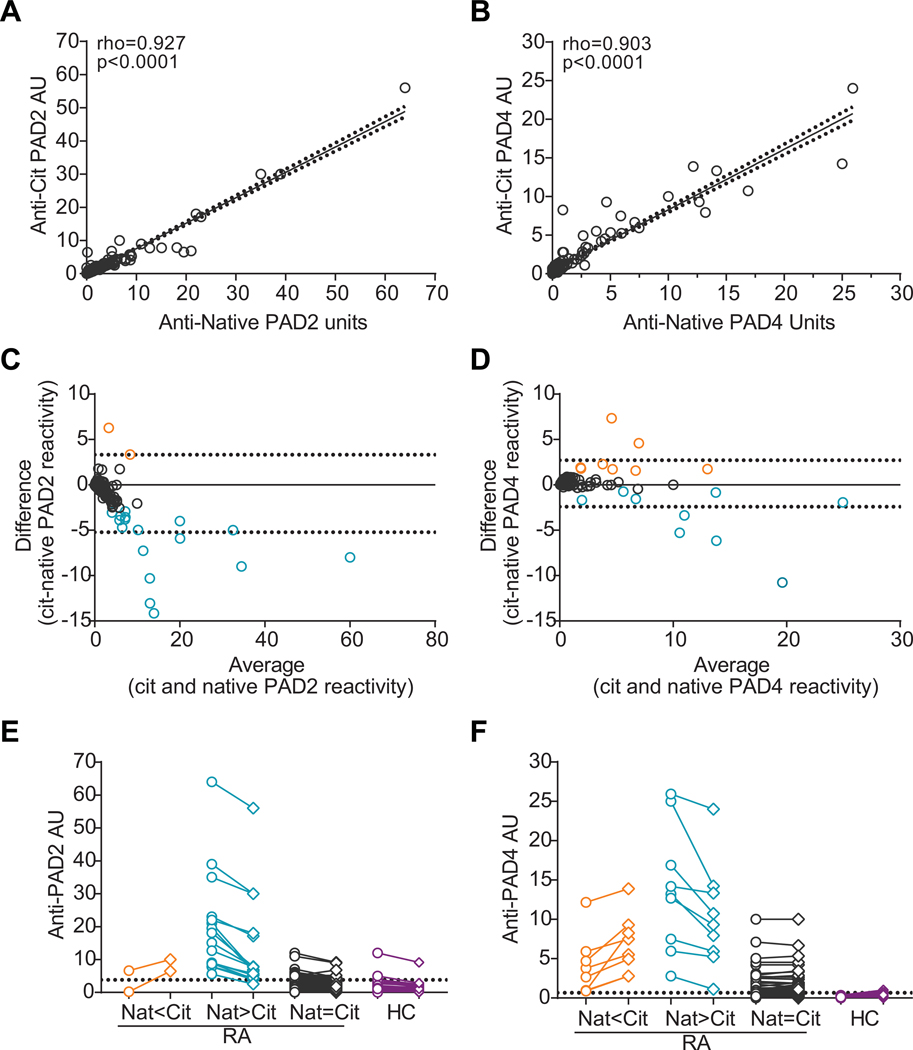

To determine whether autocitrullination of PAD2 or PAD4 affects immunogenicity, we studied the effect of autocitrullination on autoantibody binding in a well-established cohort of patients with RA in which antibodies to native PADs have been described(5, 6). Anti-citrullinated and native PAD ELISAs were performed in parallel, and linear regression analysis revealed a strong correlation between immunoreactivity to native and citrullinated PAD2 (rho=0.927, p<0.0001; Figure 2A) or PAD4 (rho=0.903, p<0.0001; Figure 2B). Although a significant correlation was noted, scatter around the trend line was observed, suggesting that some sera preferred the native or citrullinated form of each PAD. As an unbiased approach to identify sera that differed significantly from the rest of the dataset, immune reactivity to native PAD was subtracted from the reactivity observed to citrullinated PAD for each patient and an outlier calculation was performed (Figure 2C and D). This approach confirmed that 90% of sera bound similarly to PAD regardless of citrullination status, but identified a minority of sera that exhibited preferential recognition of either native or citrullinated PAD. Sera were categorized into these three groups and pairwise binding to native and citrullinated PAD2 or PAD4 is shown relative to immunoreactivity of healthy control sera (Figure 2E and F, respectively). Of the anti-PAD2 positive sera, 4.8% (2/42) bound preferentially to citrullinated PAD2 with only one serum demonstrating exclusive binding to the citrullinated form, 40.5% (17/42) bound preferentially to native PAD2 with less reactivity against the citrullinated antigen, and 54.8% (23/42) bound irrespective of citrullination status. Of the anti-PAD4 positive sera, 10.4% (8/77) preferred citrullinated PAD4, 11.7% (9/77) preferred native PAD4, and 77.9% bound similarly to both native and citrullinated PAD4. No sera were identified that exclusively recognized citrullinated PAD4. These preferences were not related to ACPA status since there was no significant difference in ACPA positivity or level between the three groups for each PAD (Table S3). In addition, there was no correlation between antibody binding to native PAD2 vs. PAD4 or citrullinated PAD2 vs. PAD4 (Figure S3), suggesting that the observed specificities are not the consequence of polyreactive autoantibody binding.

Figure 2. Anti-PAD antibodies bind similarly to native and citrullinated PADs.

Linear regression was used to determine the relationship between RA sera reactivity (n=184) to native and citrullinated PAD2 (A) or PAD4 (B). The trendline (solid line), 90% confidence intervals (dotted lines), Spearman’s rho, and p-values for each fit are indicated. (C and D) The difference in antibody reactivity to native PAD and citrullinated (cit) PAD was plotted on the y-axis (“cit-native PAD reactivity”) versus the average recognition of native and citrullinated PAD2 (C) and PAD4 (D) for each patient. A value of zero (solid line) represents equal binding to native and citrullinated PAD, and the 95% confidence interval is shown (dotted lines). (E and F) Sera that demonstrated a statistical preference for the native (negative values, blue) or citrullinated (positive values, orange) form of PAD2 or PAD4 are indicated. RA sera were grouped into three groups according to their binding to native (open circles, “Nat”) and citrullinated (open diamonds, “Cit”) PAD2 (E) or PAD4 (F) with Nat<Cit (orange), Nat>Cit (blue), and Nat=Cit (gray) binding indicated. Immunoreactivity of healthy control sera (HC, purple) to native or citrullinated PAD2 (n=37) or PAD4 (n=39) is also shown, and the >95th percentile is indicated (dotted line at 3.83 and 0.658, respectively). AU=arbitrary units

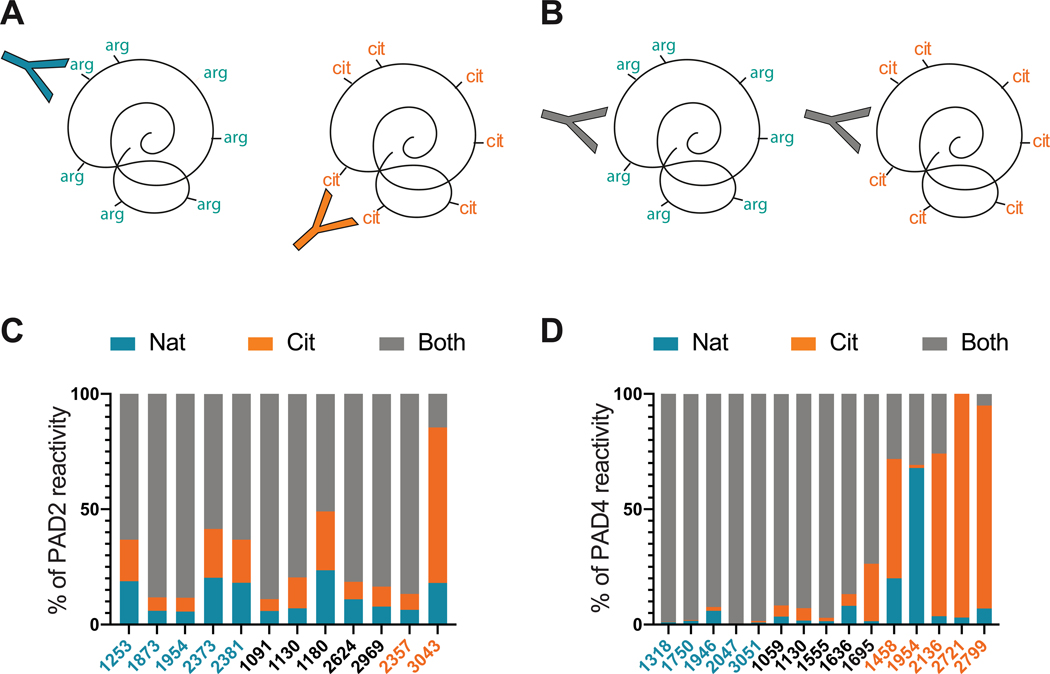

These data revealed that the majority of RA patient sera bound similarly to native and citrullinated PADs. This suggested two possibilities: the coexistence of distinct groups of anti-native PAD and anti-citrullinated PAD antibodies within the same individual (Figure 3A) or the presence of antibodies that bind to epitopes independently of citrullination status (Figure 3B). We therefore performed blocking studies to clearly differentiate between these two scenarios and define the proportion of antibodies in each serum that bound specifically to native PAD, citrullinated PAD, or both. Representative sera from Figure 2 that demonstrated defined reactivity to native and citrullinated PAD2 (n=12) or PAD4 (n=15) were pre-incubated with the relevant native or citrullinated PAD, or buffer alone, prior to use in anti-PAD ELISAs with the reciprocal PAD (Figure 3C and D). In sera known to prefer native PADs or react equally to native and modified forms (Figure 2C), a significant proportion of autoantibodies bound irrespectively of citrullination status (Figure 3C–D and Table S4). This suggests that although some sera preferred native PADs in the initial screen (Figure 2), the majority of this reactivity is due to antibodies that have the capacity to bind epitopes shared by both native and citrullinated PADs (as illustrated in Figure 3B). For the single serum that appeared exclusive for citrullinated PAD2 in Figure 2C, however, 67.4% of the antibodies were specific for citrullinated PAD2, while only 14.5% bound to both native and citrullinated PAD2 (as illustrated in Figure 3A). Similarly, among sera that preferentially bound to citrullinated PAD4, the majority of the reactivity was due to the presence of antibodies that had a strong preference for the modified antigen (Figure 3D and Table S4), with the exception of one serum (patient 1954), which appeared to contain a larger pool of native-specific antibodies than detected in the original screen. Using this approach, we demonstrated that the majority of PAD reactivity in patients with RA is attributed to the presence of autoantibodies that bind independently of autocitrullination status, suggesting native PADs as the dominant targets of autoantibodies in RA.

Figure 3. Anti-PAD autoantibodies bind PADs irrespective of citrullination status.

Two hypothetical scenarios are shown that could explain the observed binding of sera to both the native and citrullinated forms of PAD2 or PAD4. (A) Depicts the co-existence of two distinct autoantibody subsets, with unique specificities for either the native or the citrullinated form of the PAD. (B) Depicts a single group of anti-PAD autoantibodies that bind to epitopes irrespective of citrullination status, and can therefore bind both native and citrullinated forms of the PAD. A subset of anti-PAD2 (n=12, C) or PAD4 (n=15, D) antibody positive sera were pre-incubated with buffer alone (unblocked) or blocked with either native or citrullinated PAD prior to performing ELISAs with the reciprocally modified PAD. The “% PAD2 (or PAD4) reactivity” of each serum with specificity to native PAD (blue), citrullinated PAD (orange), or to bind both forms irrespective of citrullination status (gray) is shown on the y-axis. Each RA sera is indicated with a unique ID#, and they are color coded according to the binding preferences identified in Figure 2C.

Discussion

Although the mechanisms that drive the emergence and specificity of autoreactivity in RA are still unknown, posttranslational modifications are considered key components in the lack of tolerance to self-antigens. Since citrullination is a major determinant of autoantigen recognition by ACPAs in RA, and PADs have the capacity to autocitrullinate, it is reasonable to surmise that citrullination may enhance autoantibody recognition of PAD2 and PAD4. Interestingly, however, we found that the majority of PAD reactivity in RA occurred irrespective of citrullination status. While a minority of sera preferred citrullinated PAD, only a single anti-PAD2 serum was detected that bound exclusively to citrullinated PAD2. Furthermore, a subset of sera was identified for which PAD recognition was decreased by citrullination. The data presented here demonstrate that citrullination is not a major antigenic determinant for anti-PAD antibody reactivity in the vast majority of patients with RA, and in some cases can be detrimental for autoantibody binding.

This study addressed an important gap in knowledge that has mechanistic implications for understanding the relationship between anti-PAD antibodies and ACPAs in patients with RA. Although reactivity to autocitrullinated PADs may be hypothesized to be the nidus for both native PAD recognition and ACPA development, our study supports a growing body of data that autoimmunity to citrullinated antigens develops prior to and distinctly from anti-PAD immunity. In longitudinal studies, anti-PAD4 antibodies most often follow ACPA development in double-positive individuals(15), PAD4 antibodies can be found in ACPA-negative individuals(7), and anti-PAD2 antibodies are not associated with ACPAs(5). In addition, although analysis of monoclonal APCAs has revealed polyreactivity to multiple citrullinated targets(16), our data demonstrates that APCAs have little cross-reactivity with autocitrullinated PADs. Analysis of human monoclonal anti-PAD4 antibodies further supports distinct origins of these two specificities, revealing that anti-PAD4 antibodies arise from native PAD-specific B cell precursors, which are not polyreactive and do not recognize citrullinated antigens(17). This suggests that while ACPAs result from constant stimulation with abnormally citrullinated antigens, anti-PAD antibodies arise from the recognition of immunogenic native PAD4 by pre-existent autoreactive cells in a subset of patients with RA. Indeed, cleavage of native PAD4 by granzyme B increases its recognition by autoreactive CD4+ T cell in patients with RA(18), suggesting that cleavage and not citrullination is an important determinant for autoreactivity to PAD4 in RA.

Our study also supports the growing appreciation that, in addition to the emerging list of modified antigens, unmodified proteins are also prominent targets of the autoimmune response in RA (13, 19, 20). While anti-PAD antibodies have historically been detected in their native form, this study confirms that these antibodies bind irrespective of citrullination in most patients. A potential caveat of our study is that PAD autocitrullination in vitro may not be identical to what is occurring in vivo, which may impact antibody binding, both by creating non-physiologic epitopes and destroying others. In summary, our study suggests that while ACPAs and anti-PAD antibodies belong to a larger family of citrullination-associated autoantibodies, these autoantibodies are likely driven by distinct pathogenic mechanisms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Joan Bathon, M.D. from Columbia University for access to sera samples from the ESCAPE-RA cohort participants and Hong Wang, M.D., Ph.D. for technical support.

Grant Support:

Funding for this project was provided by the Rheumatology Research Foundation, Jerome L. Greene Foundation, and National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) [grant numbers R01 AR050026 and R01 AR069569]. We also acknowledge the support of the Center for Proteomics Discovery at Johns Hopkins and shared instrumentation grant from the NIH [grant number S10 OD021844]. The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the author and does not represent the official views of the NIAMS or the NIH.

Financial Interests:

ED, JTG, and FA are authors on licensed patent no. 8,975,033, entitled “Human autoantibodies specific for PAD3 which are cross-reactive with PAD4 and their use in the diagnosis and treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and related diseases” and ED and FA are authors on provisional patient no. 62/481,158 entitled “Anti-PAD2 antibody for treating and evaluating rheumatoid arthritis”. FA serves as consultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb, has received a grant from Medimmune, and personal fees from Celgene, outside of this submitted work. ED has received a grant from Pfizer, Celgene, and Bristol-Myers Squibb and personal fees from Celgene, outside of this submitted work. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Darrah E, Andrade F. Rheumatoid arthritis and citrullination. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2017; September 21;. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kinloch A, Lundberg K, Wait R, Wegner N, Lim NH, Zendman AJ, et al. Synovial fluid is a site of citrullination of autoantigens in inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2008; August;58(8):2287–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang X, Xia Y, Pan J, Meng Q, Zhao Y, Yan X. PADI2 is significantly associated with rheumatoid arthritis. PLoS One 2013; December 5;8(12):e81259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suzuki A, Yamada R, Chang X, Tokuhiro S, Sawada T, Suzuki M, et al. Functional haplotypes of PADI4, encoding citrullinating enzyme peptidylarginine deiminase 4, are associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Genet 2003; August;34(4):395–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darrah E, Giles JT, Davis RL, Naik P, Wang H, Konig MF, et al. Autoantibodies to Peptidylarginine Deiminase 2 Are Associated With Less Severe Disease in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Front Immunol 2018; November 20;9:2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris ML, Darrah E, Lam GK, Bartlett SJ, Giles JT, Grant AV, et al. Association of autoimmunity to peptidyl arginine deiminase type 4 with genotype and disease severity in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2008; July;58(7):1958–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halvorsen EH, Pollmann S, Gilboe IM, van der Heijde D, Landewe R, Odegard S, et al. Serum IgG antibodies to peptidylarginine deiminase 4 in rheumatoid arthritis and associations with disease severity. Ann Rheum Dis 2008; March;67(3):414–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao J, Zhao Y, He J, Jia R, Li Z. Prevalence and significance of anti-peptidylarginine deiminase 4 antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2008; June;35(6):969–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrade F, Darrah E, Gucek M, Cole RN, Rosen A, Zhu X. Autocitrullination of human peptidylarginine deiminase 4 regulates protein citrullination during cell activation. Arthritis Rheum 2010; March 3;. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slack JL, Jones LE Jr, Bhatia MM, Thompson PR Autodeimination of protein arginine deiminase 4 alters protein-protein interactions but not activity. Biochemistry 2011; May 17;50(19):3997–4010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tran DT, Cavett VJ, Dang VQ, Torres HL, Paegel BM. Evolution of a mass spectrometry-grade protease with PTM-directed specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016; December 20;113(51):14686–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mechin MC, Coudane F, Adoue V, Arnaud J, Duplan H, Charveron M, et al. Deimination is regulated at multiple levels including auto-deimination of peptidylarginine deiminases. Cell Mol Life Sci 2010; May;67(9):1491–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Konig MF, Giles JT, Nigrovic PA, Andrade F. Antibodies to native and citrullinated RA33 (hnRNP A2/B1) challenge citrullination as the inciting principle underlying loss of tolerance in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2016; November;75(11):2022–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Motulsky HJ, Brown RE. Detecting outliers when fitting data with nonlinear regression - a new method based on robust nonlinear regression and the false discovery rate. BMC Bioinformatics 2006; March 9;7:123,2105–7-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Darrah E, Yu F, Cappelli LC, Rosen A, O’Dell JR, Mikuls TR. Association of baseline peptidylarginine deiminase 4 autoantibodies with favorable response to treatment escalation in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2018; December 3;. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kolfenbach JR, Deane KD, Derber LA, O’Donnell CI, Gilliland WR, Edison JD, et al. Autoimmunity to peptidyl arginine deiminase type 4 precedes clinical onset of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2010; September;62(9):2633–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elliott SE, Kongpachith S, Lingampalli N, Adamska JZ, Cannon BJ, Mao R, et al. Affinity Maturation Drives Epitope Spreading and Generation of Proinflammatory Anti-Citrullinated Protein Antibodies in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2018; December;70(12):1946–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi J, Darrah E, Sims GP, Mustelin T, Sampson K, Konig MF, et al. Affinity maturation shapes the function of agonistic antibodies to peptidylarginine deiminase type 4 in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2018; January;77(1):141–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Darrah E, Kim A, Zhang X, Boronina T, Cole RN, Fava A, et al. Proteolysis by Granzyme B Enhances Presentation of Autoantigenic Peptidylarginine Deiminase 4 Epitopes in Rheumatoid Arthritis. J Proteome Res 2017; January 6;16(1):355–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maksymowych WP, Marotta A. 14–3-3eta: a Novel Biomarker Platform for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2014; Sep-October;32(5 Suppl 85):S,35–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.