Abstract

Study objectives:

Age-related changes in sleep include a reduction in total sleep time and a greater incidence of sleep disorders, and are also an integral part of neurodegenerations. In the present study, we aimed to: a) identify common genetic variants that may influence self-reported sleep duration, and b) examine the association between the identified genetic variants and performance in different cognitive domains.

Methods:

A sample of 197 cognitively healthy participants, aged 20-80 years, mostly non-Hispanic Whites (69%), were selected from the Reference Abilities Neural Network and the Cognitive Reserve study. Each participant underwent an evaluation of sleep function and assessment of neuropsychological performance on global cognition and four different domains (memory, speed of processing, fluid reasoning, language). Published GWAS summary statistics from a PS for sleep duration in a large European ancestry cohort (N=30,251) were used to derive a Polygenic Score (PS) in our study sample. Multivariate linear models were used to test the associations between the PS and sleep duration and cognitive performance. Age, sex, and education were used as covariates. Secondary analyses were conducted in three age-groups (young, middle, old).

Results:

Higher PS was linked to longer sleep duration and was also associated with better performance in global cognition, fluid reasoning, speed of processing, and language, but not memory. Results especially for fluid reasoning, language, and global cognition were driven mostly by the young group.

Conclusions:

Our study replicated the previously reported association between sleep-PS and longer sleep duration. We additionally found a significant association between the sleep-PS and cognitive function. Our results suggest that common genetic variants may influence the link between sleep duration and cognitive health.

Keywords: sleep duration, Polygenic Score, cognition, cognitively healthy aging

Introduction

Sleep is implicated in cognitive functioning in young adults, while healthy older adults do not always demonstrate clear associations between sleep and cognitive functioning [1]. Sleep does serve many functions, and these range from tissue restoration to brain metabolite clearance; however, it is of particular interest the role of sleep in cognitive functioning [1-3]. Sleep duration is specifically linked to cognitive performance, with more often short sleep duration being associated to greater cortical β-amyloid burden, which is a precursor to cognitive decline [4]. Changes in sleep patterns are common among the aging population, with approximately 5% of older adults meet the criteria for clinically significant insomnia disorders and 20% for sleep apnea syndromes [1]. Self-reported sleep problems seem to reflect poor overall quality of sleep, which has also been associated with alterations in cognition [2-6]. A recent study suggests that high sleep fragmentation is linked to high neocortical expression of genes characteristic of aged microglia, independent of chronological age, which in turn is associated with poor cognition [7]. Habitual sleep duration has been also found to predict future risk for cognitive impairments including dementia, in a large group of older women [8]. In a different study of women, results indicated that extreme sleep durations in both middle and later life were linked to poor cognition [9]. Since especially short sleep duration has been linked to poor cognitive performance [5, 6], there is support that sleeping well especially in middle age promotes sustained cognitive integrity [1].

Different genes have been also related to sleep regulation. The most common sleep-regulatory genes are circadian locomotor output cycles kaput (CLOCK) which is mostly associated with insomnia and circadian rhythms, PERIOD (PER), linked to sleep homeostasis and circadian alertness, Brain and Muscle Arnt-Like 1 (BMAL1) linked to sleep deprivation, and crystal (CRY) linked to sleep homeostasis [10]. Associations have been found between single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within these genes and cognitive phenotypes such as memory formation, consolidation, and cognitive alertness [10, 11]. It has also been reported that the rhythmic expression of specific sleep genes (BMAL1, CRY1, and PER1) is lost in neurodegenerative diseases such as Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer's disease (AD) [12]. Another gene associated with sleep regulation is Apolipoprotein E- ε4 (ApoE-ε4). Interestingly, our data analyses in a large group of non-demented older adults indicated that carriers of the specific gene had less snoring and subjective sleep apnea, even after controlling for multiple covariates [10, 11]. A complex etiology combining multiple environmental and genetic causes could affect the association between sleep and genes like APOE-ε4, leaving space for more research on the field. Specific molecular clocks in different brain regions, their circadian phases and their anatomical relationships may help to understand the mechanisms of interaction between circadian clocks, sleep and cognition [10].

Dashti and colleagues [13] have recently reported 78 loci significantly associated with self-reported habitual sleep duration through genome-wide association analysis in 446,118 adults of European ancestry. In a sample of elderly adults [14], a Polygenic Score (PS) was derived from genetic variants associated with chronotype and sleep duration identified an association between shorter sleep latency and higher levels of visuospatial ability, processing speed, and verbal memory. To our knowledge, no existing study has combined sleep-PS and cognitive data across age spectrum. In the current study, using a sample of cognitively healthy adults we aimed to a) replicate the association between sleep-PS and self-reported sleep duration and b) examine the link between the sleep -PS and cognition (global and domain-specific).

Methods

Study Participants.

Study participants were recruited for the Reference Ability Neural Network (RANN), and the Cognitive Reserve (CR) study. The RANN study was designed to identify networks of brain activity uniquely associated with performance across adulthood for each of the four following reference abilities: memory, fluid reasoning, speed of processing and language [15]. The CR study was designed to elucidate the neural underpinnings of cognitive reserve and the concept of brain reserve [16]. All participants were native English speakers, right-handed, with at least a fourth-grade reading level. In order to be included in the study, participants had to be also free of any major neurological or psychiatric conditions that could affect their cognition. Careful screening excluded participants with MCI or AD. Additional inclusion criteria for participants required: 1) score equal or greater than 130 on the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale [17], in order to guarantee a cognitively normal status, 2) minimal or no functional capacity complaints [18] and, 3) complete data on imputed genome-wide genotyped (GWAS), sleep, cognitive performance in all domains, and socio-demographic variables (sex, age, and education). Both RANN and CR studies have been approved by the Institutional Review Board of Columbia University. More detailed information about the two studies can be found in previous publications [15, 16, 19-22].

Genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism genotype data (GWAS).

Each participant had a venous blood drawn during their visit at Columbia University. DNA samples were obtained through whole blood extraction. Genotyping was performed using Omni 1M chips, according to Illumina procedures. Genotype calling was performed using GenomeStudio v.1.0. Quality control was applied to both DNA samples and SNPs. Specifically, samples were removed from further analysis if they had call rates below 95%, sex discrepancies and relatedness.

GWAS imputation.

GWAS data for all study participants was imputed using the Haplotype Reference Consortium (HRC v1.1) panel through the Michigan Imputation online server (Das, Forer et al. 2016). The HRC is a reference panel of 64,976 human haplotypes at 39,235,157 SNPs constructed using whole genome sequence data from 20 studies of predominantly European ancestry [23].

Polygenic Score (PS).

Using the summary data of the GWAS of sleep duration reported by Dashti et al. [13], we derived a Polygenic Score (PS) based on 78 SNPs in our sample. PRSice software [24] was used to construct the PS and to graphically display the PS-phenotype association results.

Cognitive assessment.

Each participant underwent an extensive neuropsychological evaluation. From the neuropsychological battery, we derived four cognitive domains: memory, fluid reasoning, speed of processing, and language. The following tests were used: for memory: Selective Reminding Test (SRT) [25], Long-Term Storage, Consistent Long Term Retrieval, Total words recalled on the last trial. For fluid reasoning: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-III) matrix reasoning raw score, WASI-III letter-number sequencing raw score, and Block design test, total correct [26]. For speed of processing: WAIS-III digit-symbol total correct, Trail Making Test (TMT-A) total time [27], and Stroop Word Raw Score [28]. For language: WAIS-III language test, the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR) [29], and the American National Adult Reading Test (AMNART), errors [30]. Z-scores were computed for each cognitive task, and each participant, based on the means and standard deviations (SD) of all participants. Scores for TMT-A time and AMNART errors were transformed so that higher score indicates better performance, following the directionality of the other tests. We lastly created a global cognition score, using the sum of all the four cognitive domains together.

Sleep assessment.

Self-reported sleep duration was extracted from the Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [31]. The question was the following: “During the past month, how many hours of actual sleep did you get at night? (This may be different than the number of hours you spend in bed).” Answer was in hours of sleep per night. The scoring of the question was as follows: 0 for more than 7 hours, 1 for 6-7 hours, 2 for 5-6 hours, and 3 for less than 5 hours.

Statistical analysis

In order to derive the Polygenic Score, PRSice software calculates the sum of alleles associated with the phenotype of interest across many genetic loci, weighted by their effect sizes estimated from a GWAS of the corresponding phenotype in an independent sample. It requires only GWAS results on a base phenotype and genotype data on a target phenotype as input (base and target phenotype may be the same); it outputs PS for each individual and figures depicting the PS model fit at a range of p-value thresholds. We used the previously reported SNPs being associated with sleep duration [13] (see Supplemental material, Table 1) as the base-file. From the 78 SNPs previously reported, 69 available in our data. In the initial analysis, the sleep duration variable was used as the phenotype, while each cognitive domain and global cognition were used as the phenotype in the secondary analyses. Beta values were also used in the analyses (non-binary phenotype Target F). Clumping was used to obtain SNPs in linkage disequilibrium with an r2<0.25 within a 250 kb window. SNPs used to create the PS were selected according to the significance of their association with the phenotype at the following significance thresholds: 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.5, and 1, where the latter denotes the use of all SNPs.

Age, sex, and years of education were used as covariates in all the statistical analyses. Age and years of education were used as continuous variables, while sex was used as dichotomous.

Lastly, in order to examine any differences by age, we stratified the sample into three age groups (young 20-40, middle 41-60, old 61-80), and performed all the analyses between the sleep-PS and cognition. Adjusted models included sex and years of education as covariates.

Results

A total of one hundred ninety-seven participants (N=197) were included in the analyses. The study sample was characterized by a slightly higher frequency of women (54%). On average, study participants were 56 years old (standard deviation SD=16) ranging from 20 to 80 years old, and had 16 years of education (SD=2). The majority of the participants were non-Hispanic Whites (69%). Participants did not suffer from any major neurological/ psychiatric condition, and mostly, did not have any other major medical condition or were under specific medication affecting sleep habits. Prevalence of medical comorbidities that could affect cognition and sleep (diabetes, myocardial infraction, hypertension, and stroke) was low (diabetes 2.9%, stroke 0%, hypertension 19% -of which mostly treated-, myocardial infraction 0%). We also examined the “sleep medication” question from the PSQI, where the percentage of people taking no or very few sleeping drugs was reaching 87%).

Divided by age, the older group had the bigger sample size, with, interestingly, slightly higher mean years of education that the two other age groups. Further details about the demographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants are provided in Tables 1,2.

Table 1:

Characteristics of RANN/CR total dataset

| Characteristics | Mean (SD) | Minimum | Maximum | Total N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, Mean (SD) | 55.6 (15.8) | 21 | 78 | 197 |

| Education, years, Mean (SD) | 16.2 (2.3) | 11 | 22 | 197 |

| Sex, women, N (%) | 107 (54.3) | - | - | 197 |

| Sleep Duration, N (%) | - | - | - | 197 |

| 0 (>7 h) | 107 (54.3) | - | - | - |

| 1 (6-7 h) | 54 (27.4) | - | - | - |

| 2 (5-6 h) | 30 (15.2) | - | - | - |

| 3 (<5 h) | 6 (3) | - | - | - |

| PS, Mean (SD) | 0.49 (0.41) | 0.36 | 0.59 | 197 |

| Cognitive Domains, Mean (SD) | ||||

| Memory | 0.003 (0.95) | −2.36 | 1.64 | 197 |

| Fluid reasoning | 0.80 (0.83) | −1.76 | 2.16 | 197 |

| Speed of processing | −0.01 (0.87) | −3.23 | 2.12 | 197 |

| Language | 0.13 (0.83) | −2.46 | 1.21 | 197 |

| Global cognition | 0.20 (2.58) | −6.09 | 6.45 | 197 |

Table 2:

Characteristics of our sample by age-group

| Characteristics | Young (20-40) N=43 |

Middle (41-60) N=47 |

Old (61-80) N=107 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | |||

| Age, years, Mean (SD) | 30 (5) | 52 (6) | 67.5 (4.6) |

| Education, years, Mean (SD) | 15.9 (1.8) | 15.9 (2.4) | 16.4 (2.4) |

| Sex, women, N (%) | 28 (65.1) | 22 (46.8) | 57 (53.3) |

| Sleep Duration, N (%) | |||

| 0 (>7 h) | 28 (65.1) | 20 (42.6) | 59 (55.1) |

| 1 (6-7 h) | 11 (25.6) | 13 (27.7) | 30 (28) |

| 2 (5-6 h) | 3 (7) | 10 (21.3) | 17 (15.9) |

| 3 (<5 h) | 1 (2.3) | 4 (8.5) | 1 (0.9) |

| PS, Mean (SD) | 0.491 (0.342) | 0.495 (0.438) | 0.492 (0.42) |

| Cognitive Domains, Mean (SD) | |||

| Memory | 0.55 (0.84) | 0.12 (0.89) | −0.27 (0.91) |

| Fluid reasoning | 0.57 (0.79) | 0.18 (0.85) | −0.16 (0.73) |

| Speed of processing | 0.81 (0.78) | 0.01 (0.80) | −0.35 (0.69) |

| Language | −0.10 (0.81) | 0.18 (0.81) | 0.20 (0.84) |

| Global cognition | 1.84 (2.77) | 0.65 (2.46) | −0.53 (2.3) |

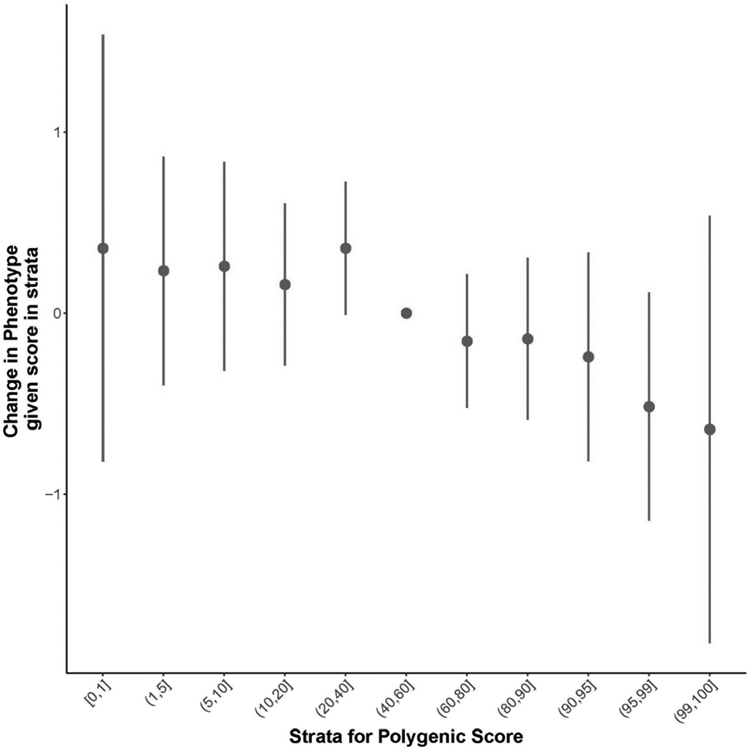

As expected, our results replicated the significant association (B=−5.06 SE=1.40, p= 4 x 10−4) between PS and self-reported sleep duration (see Table 3). PS proved to be a good predictor of sleep duration in cognitively normal adults, with the link indicating that higher values of PS was associated with longer sleep duration. Figure 1 indicates a quantile plot as an illustration of the effect of increasing PS on predicted risk of sleep duration.

Table 3:

PRSice results for associations between: sleep duration and genes, and sleep duration PS and each cognitive domain/global cognition. Unadjusted results

| Out comes | Threshold | R2 | B | SE | P | #SNPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep duration | 5.0E-08 | 0.062 | −5.06 | 1.40 | 4 x 10−4 | 69 |

| Cognitive domains | ||||||

| Memory | 5.0E-08 | 0.0002 | 0.33 | 1.63 | 0.84 | 69 |

| Reasoning | 5.0E-08 | 0.067 | 5.14 | 1.37 | 2 x 10−4 | 69 |

| Speed | 5.0E-08 | 0.031 | 3.65 | 1.47 | 0.014 | 69 |

| Language | 5.0E-08 | 0.14 | 7.62 | 1.33 | 3.9 x 10−8 | 69 |

| Global cognition | 5.0E-08 | 0.072 | 16.75 | 4.28 | 1.2 x 10−4 | 69 |

Figure 1:

Quantile plot as an illustration of the effect of increasing PS on predicted risk of sleep duration. Lower sleep duration score (more hours of sleep) was associated with higher PS score

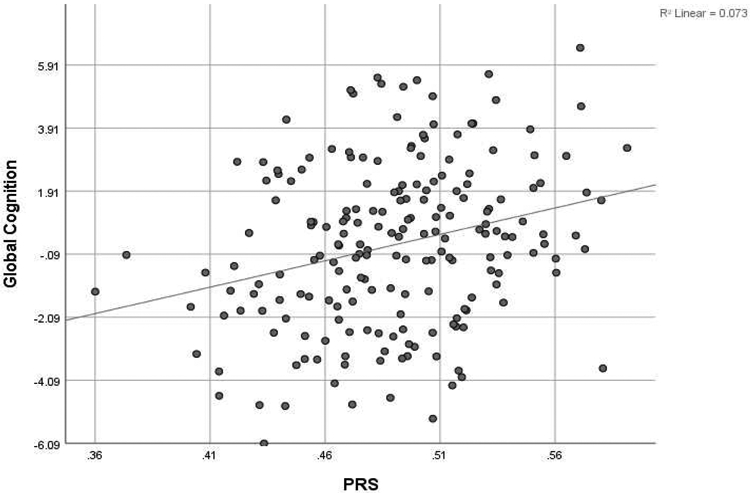

Secondary analysis results showed that the PS was significantly associated with cognitive domains and global cognition as well; longer sleep duration PS was associated with better performance on fluid reasoning (B=5.14, SE=1.37, p= 2 x 10−4 , speed of processing (B=3.65, SE=1.47, p=0.014), language (B=7.62, SE=1.33, p=3.9 x 10−8), and global cognition (B=16.75, SE=4.28, p= 1.2 x 10−4 ). No association between PS and memory performance was observed (see Table 2). Figure 2 provides a scatterplot illustrating the association between sleep PS and global cognition, showing that higher PS was linked to better performance. Results remained significant even after adjusting for age, sex, education; fluid reasoning (B=4.32, SE=1.23, p=5 x 10−4), speed of processing (B=3.62, SE=1.24, p=0.004), language (B=5.67, SE=1.23, p=7.1 x 10−6), as well as global cognition (B=13.76, SE=3.73, p=3 x 10−4 ). We did not find any significant association between sleep duration PS and memory (B=0.15, SE=1.52, p=0.920).

Figure 2:

Scatterplot of the association between sleep duration PS and global cognition (z-scores)

In the analysis by age group, the unadjusted results revealed significant associations of Sleep-PS with language and global cognition in all three age groups. Sleep-PS was linked to performance in fluid reasoning for young and middle-aged participants, but not for older adults. The association between Sleep-PS and speed of processing was significant only in older adults. Consistent with the analysis of all participants, the association between sleep PS and memory was not significant at any age-group. Similar were the adjusted results. Further details are provided in Table 4.

Table 4:

PRSice results for associations between sleep duration PS and each cognitive domain/ global cognition by age-group. Results unadjusted and then adjusted for sex, and education

| Young Unadjusted |

Adjusted | Middle Unadjusted |

Adjusted | Old Unadjusted |

Adjusted | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Memory | 5.142, 0.119 | 5.362, 0.141 | 0.726, 0.813 | −0.088, 0.978 | −1.296, 0.545 | –1.659, 0.446 |

| Processing speed | 5.516, 0.696 | 4.329, 0.197 | 3.929, 0.146 | 3.552, 0.216 | 3.481, 0.031 | 3.081, 0.06 |

| Fluid reasoning | 11.154, 9.67428e-05 | 9.582, 0.002 | 5.261, 0.067 | 4.732, 0.11 | 3.254, 0.057 | 2.298, 0.168 |

| Language | 10.216, 0.0007 | 8.579, 0.004 | 6.885, 0.011 | 5.347, 0.041 | 6.876, 0.0003 | 5.093, 0.003 |

| Global cognition | 32.028, 0.0017 | 27.852, 0.009 | 16.801, 0.038 | 13.544, 0.102 | 12.316, 0.018 | 8.813, 0.079 |

Discussion

In a sample of cognitively normal adults, a sleep duration Polygenic Score was significantly associated with several domains of cognition, as well as global cognition. Our results validated the association between specific candidate genes and self-reported sleep duration in our cohort. Higher values of the Sleep-PS predicted longer sleep duration.

Longer Sleep-PS was linked to the cognitive abilities of reasoning, speed of processing, and language, so that participants with longer Sleep-PS were in lower risk of cognitive dysfunction. Some studies in the general population report that both short and long sleep duration have been associated with cognitive dysfunction [32, 33]. However, others reveal such a link for only short and not long sleep duration, especially in a group of older men [34], older women [35] or school-aged children [36]. Yet, a different study showed that longer sleep duration was significantly associated with better cognitive performance in a group of college students [37]. Similarly, our results indicate that longer sleep duration is associated with better cognitive performance. Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep has been linked to enhanced fluid reasoning [38] and executive function [39], thus, we could hypothesize that longer sleep duration implies more REM sleep, leading to a better cognitive status. Considering that sleep deprivation is a consequential factor of cognitive decline [40], maintaining a longer sleep duration in cognitively normal aging matches with good cognitive performance. These results are enhanced by the analyses in three different age-groups. Stronger link between the PS and cognitive performance was indicated in the young group, so that younger participants with longer Sleep-PS performed better in fluid reasoning, language, and global cognition.

Interestingly, there was no significant association between sleep PS and memory performance. Memory retention is reported to have greater impact when the learning session is followed by a sleeping period, instead of a waking period [41]. The beneficial effect of sleep seems to interact with the learning process through the circadian rhythms [42]. However, other research does not support the role of sleep in memory consolidation [43], with other studies also pointing the need for further examination of the role of sleep to memory [44, 45]. Education could be a significant factor affecting these results. Our sample is characterized by a uniquely high-educated older group of participants (16 mean years of education). Hence, this group is highly chanced to be also characterized of a high cognitive reserve, and thus, preventing them from cognitive declines, especially in memory which is mostly affected in neurodegenerations such as Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s disease [21, 46, 47].

Our study has significant strengths, including the extensive neuropsychological evaluation to all participants. Moreover, study participants were selected to be free of underlying neurodegeneration that may contribute to the reported associations. Finally, we included participants covering a wide age spectrum (from 20 to 80 years of age), instead of restricting the sample to older adults.

However, there are also some limitations that must be noted. By using a candidate gene approach to define the PS, we cannot exclude the possibility that additional, unconsidered genetic variants may also contribute to the sleep-cognition association. Furthermore, the use of self-reported sleep duration measure over an objective measure of sleep is a main limitation of our research. Lastly, the lack of the working status of our participants (shift working/retirement etc.), is a limitation that should be noted since it could probably affect the sleep duration/habits of our sample.

Sleep duration genes can predict cognitive performance in cognitively normal adults. Longer sleep duration is a good predictor of good performance in fluid reasoning, speed of processing/attention, language, and global cognition as well. Maintaining a longer sleep can cultivate a good cognitive status. Longitudinal research is further needed in order to examine if sleep genes can affect/prevent a cognitive change over time.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

High polygenic score is linked to longer sleep duration

High sleep duration polygenic score is linked to better cognitive performance

Results were significant in cognitively healthy adults across age-range

Common genetic variants influence the link between sleep duration and cognitive health

Acknowledgments

This work was supported: by The National Institute of Health (NIH)/ National Institute of Aging (NIA) [Grant numbers: R01 AG026158 and RF1 AG038465], and the Bodossakis foundation.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

Financial disclosure: none

Non-financial disclosure: none

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gooneratne NS and Vitiello MV, Sleep in older adults: normative changes, sleep disorders, and treatment options. Clin Geriatr Med, 2014. 30(3): p. 591–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basner M, et al. , American time use survey: sleep time and its relationship to waking activities. Sleep, 2007. 30(9: p. 1085–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohayon MM, Sleep and the elderly. J Psychosom Res, 2004. 56(5): p. 463–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohayon MM, et al. , Meta-analysis of quantitative sleep parameters from childhood to old age in healthy individuals: developing normative sleep values across the human lifespan. Sleep, 2004. 27(7: p. 1255–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramos AR, et al. , Association between sleep duration and the mini-mental score: the Northern Manhattan study. J Clin Sleep Med, 2013. 9(7: p. 669–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miyata S, et al. , Poor sleep quality impairs cognitive performance in older adults. J Sleep Res, 2013. 22(5: p. 535–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaneshwaran K, et al. , Sleep fragmentation, microglial aging, and cognitive impairment in adults with and without Alzheimer's dementia. Sci Adv, 2019. 5(12: p. eaax7331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen JC, et al. , Sleep duration, cognitive decline, and dementia risk in older women. Alzheimers Dement, 2016. 12(1: p. 21–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devore EE, et al. , Sleep duration in midlife and later life in relation to cognition. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2014. 62(6): p. 1073–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kyriacou CP and Hastings MH, Circadian clocks: genes, sleep, and cognition. Trends Cogn Sci, 2010. 14(6): p. 259–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sakai T, et al. , A clock gene, period, plays a key role in long-term memory formation in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2004. 101(45: p. 16058–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guarnieri B and Sorbi S, Sleep and Cognitive Decline: A Strong Bidirectional Relationship. It Is Time for Specific Recommendations on Routine Assessment and the Management of Sleep Disorders in Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment and Dementia. Eur Neurol, 2015. 74(1-2: p. 43–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dashti HS, et al. , Genome-wide association study identifies genetic loci for self-reported habitual sleep duration supported by accelerometer-derived estimates. Nat Commun, 2019. 10(1: p. 1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cox SR, et al. , Sleep and cognitive aging in the eighth decade of life. Sleep, 2019. 42(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Habeck C, et al. , The Reference Ability Neural Network Study: Life-time stability of reference-ability neural networks derived from task maps of young adults. Neuroimage, 2016. 125: p. 693–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stern Y, Cognitive reserve in ageing and Alzheimer's disease. Lancet Neurol, 2012. 11(11: p. 1006–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mattis S, Dementia Rating Scale (DRS) Psychological Assessment Resources, Odessa, FL: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blessed G, Tomlinson BE, and Roth M, The association between quantitative measures of dementia and of senile change in the cerebral grey matter of elderly subjects. Br J Psychiatry, 1968. 114(512: p. 797–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Habeck C, et al. , Cognitive Reserve and Brain Maintenance: Orthogonal Concepts in Theory and Practice. Cereb Cortex, 2017. 27(8: p. 3962–3969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stern Y, et al. , The Reference Ability Neural Network Study: motivation, design, and initial feasibility analyses. Neuroimage, 2014. 103: p. 139–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stern Y, Cognitive reserve. Neuropsychologia, 2009. 47(10): p. 2015–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Razlighi QR, et al. , Cognitive neuroscience neuroimaging repository for the adult lifespan. Neuroimage, 2017. 144(Pt B: p. 294–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCarthy S, et al. , A reference panel of 64,976 haplotypes for genotype imputation. Nat Genet, 2016. 48(10: p. 1279–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Euesden J, Lewis CM, and O'Reilly PF, PRSice: Polygenic Risk Score software. Bioinformatics, 2015. 31(9): p. 1466–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buschke H and Fuld PA, Evaluating storage, retention, and retrieval in disordered memory and learning. Neurology, 1974. 24(11: p. 1019–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.D. W, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, 3rd edn., San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment, pp. 684–690. . 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reitan RM, The relation of the trail making test to organic brain damage. J Consult Psychol, 1955. 19(5: p. 393–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stroop JR, Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 1935. 18: p. 643–662. [Google Scholar]

- 29.D. W, The Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR): Test Manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grober E and Sliwinski M, Development and validation of a model for estimating premorbid verbal intelligence in the elderly. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol, 1991. 13(6: p. 933–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buysse DJ, et al. , The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res, 1989. 28(2: p. 193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kronholm E, et al. , Self-reported sleep duration and cognitive functioning in the general population. J Sleep Res, 2009. 18(4: p. 436–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kyle SD, et al. , Sleep and cognitive performance: cross-sectional associations in the UK Biobank. Sleep Med, 2017. 38: p. 85–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Potvin O, et al. , Sleep quality and 1-year incident cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older adults. Sleep, 2012. 35(4: p. 491–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tworoger SS, et al. , The association of self-reported sleep duration, difficulty sleeping, and snoring with cognitive function in older women. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord, 2006. 20(1: p. 41–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gruber R, et al. , Short sleep duration is associated with teacher-reported inattention and cognitive problems in healthy school-aged children. Nat Sci Sleep, 2012. 4: p. 33–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okano K, et al. , Sleep quality, duration, and consistency are associated with better academic performance in college students. NPJ Sci Learn, 2019. 4: p. 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walker MP, et al. , Cognitive flexibility across the sleep-wake cycle: REM-sleep enhancement of anagram problem solving. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res, 2002. 14(3: p. 317–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maquet P, et al. , Human cognition during REM sleep and the activity profile within frontal and parietal cortices: a reappraisal of functional neuroimaging data. Prog Brain Res, 2005. 150: p. 219–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Killgore WD, Effects of sleep deprivation on cognition. Prog Brain Res, 2010. 185: p. 105–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dujardin K, Guerrien A, and Leconte P, Sleep, brain activation and cognition. Physiol Behav, 1990. 47(6): p. 1271–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hockey GR, Davies S, and Gray MM, Forgetting as a function of sleep at different times of day. Q J Exp Psychol, 1972. 24(4): p. 386–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Siegel JM, The REM sleep-memory consolidation hypothesis. Science, 2001. 294(5544): p. 1058–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fowler MJ, Sullivan MJ, and Ekstrand BR, Sleep and memory. Science, 1973. 179(4070): p. 302–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maquet P, The role of sleep in learning and memory. Science, 2001. 294(5544): p. 1048–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stern Y, Cognitive reserve and Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord, 2006. 20(3 Suppl 2): p. S69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stern Y, et al. , Rate of memory decline in AD is related to education and occupation: cognitive reserve? Neurology, 1999. 53(9: p. 1942–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.