Abstract

Despite growing recognition of the importance of workforce diversity in healthcare, limited research has explored diversity among eating disorder professionals globally. This multi-methods study examined diversity across demographic and professional variables. Participants were recruited from eating disorder (ED) and discipline-specific professional organizations. Participants’ (N=512) mean age was 41.1 (SD=12.5) years; 89.6 (n=459) of participants identified as women, 84.1% (n=419) as heterosexual/straight, and 73.0% (n=365) as White. Mean years working in EDs was 10.7 (SD=9.2). Qualitative analysis revealed three themes resulting in a theoretical framework to address barriers to increasing diversity. Perceived barriers were: “stigma, bias, stereotypes, myths,” “field of eating disorders pipeline,” and “homogeneity of the existing field.” Findings suggest limited workforce diversity within and across nations. The theoretical model suggests a need for focused attention to the educational pipeline, workforce homogeneity, and false assumptions about EDs and should be tested to evaluate its utility within the EDs field.

Keywords: diversity, eating disorders, workforce, barriers, framework

Profiles of health professionals rarely reflect national profiles of social, linguistic, and ethnic diversity, and health professionals disproportionately are from higher social classes and dominant ethnic groups in society (United States [U.S.] Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, & National Center for Health Workforce Analysis, 2017; World Health Organization [WHO], 2006). However, there is growing recognition of the importance of workforce diversity in healthcare. For example, individuals from minority backgrounds may be at elevated risk for the medical and psychosocial consequences of disordered eating because they have been found to be less likely to be diagnosed with or receive care for an eating disorder (ED; Becker et al, 2003; Kazdin et al., 2017; Marques et al., 2011). Increasing diversity among professionals in the ED field may contribute to decreases in health disparities and encourage individuals from underrepresented populations to seek treatment. Additionally, increasing workforce diversity may reduce health disparities by reducing under-detection of ED in diverse patient populations, reducing provider bias and assumptions, better accommodating patient preferences, and providing more patient-centered and culturally sensitive care.

Numerous national and international initiatives have been introduced in healthcare to increase diversity in research, academia, and clinical settings. These efforts are especially relevant to EDs, given the interdisciplinary approach within the field based on medical complications, nutrition, and psychosocial aspects of these psychiatric disorders, as well as the need for heightened attention to this priority area. For example, the Academy for Eating Disorders (AED) recently established the Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Advisory Committee to actively promote a welcoming and inclusive environment to all stakeholders, to assess and address inequities in research and clinical practice, and to collaborate globally within the organization and ED field. Indeed, diversity is a complex and ever-changing blend of attributes, behaviors, and talents (Thomas, 1999). According to the U.S. Census Bureau, diversity is defined as “all of the ways in which we differ…age, gender, mental/physical abilities and characteristics, race, ethnic heritage, sexual orientation, communications style, organizational role and level, first language, religion, income, work experience, military experience, geographic location, education, work style, and family status” (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014). Yet, the domains of diversity highlighted in healthcare and research tend to be demographics, education, and profession (American Psychological Association [APA], 2018).

In fact, studies that have examined characteristics of the ED workforce often are limited in scope by focusing on a specific facet of identity (e.g., age, sex; Barbarich, 2002; Simmons et al., 2008), a specific discipline (e.g., medicine, psychology; von Ranson & Robinson, 2006), or how specific facets of diversity impact treatment (Wallace & von Ranson, 2012). Thus, as diversity initiatives increase across global healthcare, and specifically within the ED field, more inclusive information about what diversity looks like among the workforce as well as perspectives of potential barriers to promoting diversity among ED professionals is warranted. The purpose of this study was to describe various facets of diversity (i.e., demographics, professional) more inclusively among the workforce in the field of ED and broadly explore perspectives about existing barriers to increasing diversity using both quantitative and qualitative methods. Such knowledge will provide a better understanding of existing diversity and identify potential gaps in the representation of experts in the field of ED.

Methods

Participants

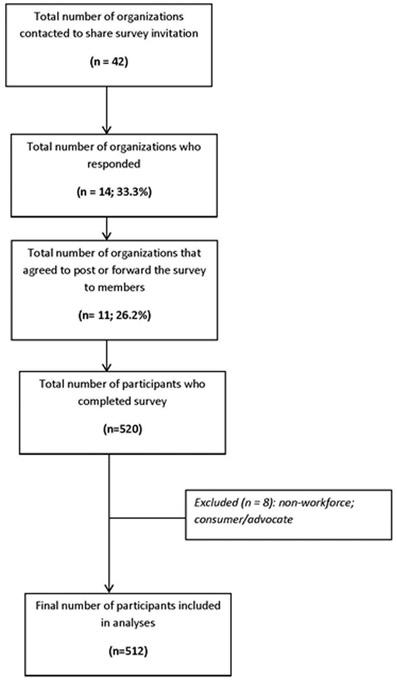

Participants (N = 512) were recruited between March and May 2018 from professional organizations with an available listserv and using snowball sampling, a nonprobability sampling technique where potential participants recruit from among their acquaintances (e.g., forwarding email with survey link; posting survey link on social media). To be more comprehensive, forty-two organizations located in 26 countries across five continents were sent an email request in English to share an online survey invitation (see Figure 1). Given that the survey was in English, we only contacted organizations whose contact information could be found on the Internet and whose websites were translated into English. Fourteen (33.3%) organizations responded and 11 (26.2%) agreed to post or forward the survey to members (see Table 1). Three organizations reported that they did not forward research opportunities using their listserv or did not allow non-members to post research opportunities. Study inclusion criteria were: 1) age ≥ 18 years, and 2) clinician or researcher in the field of ED. To be inclusive of all possible clinicians and researchers, graduate students and postdoctoral fellows/scholars were eligible for participation.

Figure 1.

Participant Recruitment

Table 1.

Professional Organizations that Shared the Online Survey Invitation

| Professional Organization | Geographical Location |

|---|---|

| Academy for Eating Disorders (AED) | United States |

| American Psychiatric Nurses Association (APNA) | United States |

| Australia & New Zealand Academy of Eating Disorders (ANZAED) | Australia |

| Austrian Society on Eating Disorders (ASED) | Austria |

| Eating Disorders Association of Canada (EDAC) | Canada |

| Eating Disorders Research Society (EDRS) | United States |

| Expert Network Eating Disorders | United States |

| Switzerland/Réseau Expert Suisse Troubles Alimentaires (ENES/RESTA) | Switzerland |

| National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA) | United States |

| Nordic Eating Disorders Society (NEDS) | Sweden, Norway, Denmark |

| Swedish Eating Disorder Society (SEDS) | Sweden |

| Therapy Center of Person with Eating Disorders in Vienna | Austria |

Note: AED and EDRS have international memberships.

Procedures and Measures

The Institutional Review Board of the University of Chicago approved this study for exemption status (Protocol # IRB18–0320). An investigator-designed survey was developed in English, and data were collected online. Survey questions inquired about demographic and educational background, current employment, and perceptions about diversity. Prior to posting the survey, colleagues who live and work outside of the U.S. provided feedback about survey questions, which were revised to consider different cultures and countries. For example, the response options for questions about race/ethnicity and religion were expanded. To facilitate consistency and inclusivity across responses, multiple-choice response options were provided for each categorical variable, with the option to write in an alternative or additional response. The invitation to participate contained a detailed description of the research project, its purpose, and procedures. If participants consented to participate by clicking on the survey link, they were directed to the survey that required 5–10 minutes to complete. Once the survey was completed, participants had the option to be directed to a new website (separate from the survey) to enter a raffle drawing for a $50 Amazon gift card.

Data Analyses

Quantitative Data.

We conducted descriptive analyses to examine diversity among the international workforce in the field of ED. All analyses were performed using SPSS© software version 22.

Qualitative Data.

A qualitative descriptive approach to data analysis (Sandelowski, 2000, 2010) was undertaken to examine responses to the broad and undefined, open-ended question: “What are some of the barriers to increasing diversity in the field of ED?” All data were extracted from the questionnaire verbatim, with two investigators (KMJ, BR) working together as a coding team. Based on the manifest content, or what the text actually said, data were categorized, and coded themes inductively developed, patterns analyzed and then integrated into a unified whole. Analysis was supported by using NVivo12, a computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software from Qualitative Solutions and Research. Rigor was supported through multiple steps: (1) confirmability, transferability and credibility through the search for confirming evidence, (2) credibility through the search for disconfirming evidence, (3) dependability through 100% of the responses reviewed and coded by the two researchers, and (4) integrating reflexivity by reviewing preliminary findings with the full interdisciplinary research team (Polit & Beck, 2017).

Research data are not shared and will abide by APA’s data preservation policies.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Table 2 provides details about demographics. Participants’ mean age was 41.1 (SD = 12.5; median = 38; range = 22–73) years. For gender, 89.6% (n = 459) of respondents identified as women, 9.8% (n = 50) as men, and 0.6% (n = 3) as non-binary or genderqueer. Regarding sexual orientation, 84.1% (n = 419) of individuals identified as heterosexual, 5.8% (n = 29) as bisexual, 5.0% (n = 25) as lesbian/gay, and 5.0% (n = 25) as asexual, fluid, mostly straight, pansexual, queer, or questioning.

Table 2.

Sample Demographics

| Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (n = 512) | ||

| Woman | 459 | 89.6 |

| Man | 50 | 9.8 |

| Non-binary or genderqueer | 3 | 0.6 |

| Sexual orientation (n = 498) | ||

| Heterosexual/straight | 419 | 84.1 |

| Bisexual | 29 | 5.8 |

| Lesbian or gay | 25 | 5.0 |

| Other (asexual, fluid, mostly straight, pansexual, queer, or questioning) | 25 | 5.0 |

| Marital Status1 (n = 511) | ||

| Divorced | 33 | 6.4 |

| In a relationship | 117 | 22.9 |

| Married/civil partnership | 296 | 57.8 |

| Never married | 29 | 5.7 |

| Separated | 6 | 1.2 |

| Single | 67 | 13.1 |

| Widowed | 5 | 1.0 |

| Prefer to self-describe | 3 | 0.6 |

| Body mass index (n = 494) | ||

| Underweight (< 18.5) | 13 | 2.6 |

| Normal or Healthy Weight (18.5-24.9) | 320 | 64.8 |

| Overweight (25.0-29.9) | 94 | 19.0 |

| Obese (≥ 30.0) | 67 | 13.6 |

| Race/ethnicity/nationality (n = 500) | ||

| Asian or Asian-American | 3 | 0.6 |

| Australian | 60 | 12.0 |

| Bi/Multi-Racial or Nationalities | 17 | 3.4 |

| Black or African-American | 3 | 0.6 |

| Canadian | 5 | 1.0 |

| European | 17 | 3.4 |

| Latino or Hispanic | 14 | 2.8 |

| White2 | 365 | 73.0 |

| Other3 | 16 | 3.2 |

| Primarily live during childhood (n = 512) | ||

| Rural | 97 | 18.9 |

| Sub-Urban | 210 | 41.0 |

| Urban | 200 | 39.1 |

| Prefer to self-describe4 | 5 | 1.0 |

| Country primarily live now (n = 508) | ||

| Australia/New Zealand | 173 | 34.1 |

| Canada | 30 | 5.9 |

| Central or Western Europe | 34 | 6.7 |

| Other | 12 | 2.4 |

| South or Central America/Latin America | 6 | 1.2 |

| United States | 253 | 49.8 |

| Religion (n = 496) | ||

| Agnostic | 111 | 22.4 |

| Atheist | 77 | 15.5 |

| Buddhist | 10 | 2.0 |

| Christian | 134 | 27.0 |

| Jewish | 37 | 7.5 |

| Spiritual but not religious | 90 | 18.1 |

| Other5 | 37 | 7.5 |

| Identified as person living with disability (n = 507) | 30 | 5.9 |

| Served in military (n = 509) | 11 | 2.2 |

| Lifetime diagnosis of mental disorder (n = 501) | 218 | 43.5 |

| Lifetime diagnosis of an eating disorder (n = 504) | 110 | 21.8 |

Note:

Individuals may have more than one response.

White includes White/Caucasian Pakeha/New Zealand of Europe Descent & Anglo/Anglo Saxon.

Other includes American, Arab, Brazilian, Indian, Israeli, Jewish, Middle-Eastern, National, South African or “Citizen of the world” (self-described response).

Other includes coastal, military bases, town, or many countries.

Other includes Unitarian Universalist, Humanist, Pagan, Pantheist, Naturist, Secular, Quaker, Muslim, Hindu, Deist, or combination of religions.

In response to the question “In what country do you primarily live now?”, 24 countries were represented. Table 3 provides details about education and employment. The mean number of years working in ED was 10.7 (SD = 9.2; range = 0–45); on average, 67.3% of participants’ weekly hours in their primary role focused on ED.

Table 3.

Education and Employment of Participants

| Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Education (n = 510) | ||

| Associate degree or equivalent | 14 | 2.7 |

| Baccalaureate or equivalent | 70 | 13.7 |

| Master’s degree or equivalent | 206 | 40.4 |

| PhD/MD or equivalent | 208 | 40.8 |

| Other | 12 | 2.4 |

| Education Background (n = 506) | ||

| Clinical Psychology | 194 | 38.3 |

| Counseling Psychology | 38 | 7.5 |

| Counseling/Psychotherapy | 6 | 1.2 |

| Dietitian/Nutrition | 101 | 20.0 |

| Medicine | 47 | 9.3 |

| Nursing | 54 | 10.7 |

| Occupational Therapy | 6 | 1.2 |

| Psychology | 12 | 2.4 |

| Public Health | 7 | 1.4 |

| Social Work | 27 | 5.3 |

| Other | 14 | 2.8 |

| Primary Area of Expertise (n = 508) | ||

| Body Image | 15 | 3.0 |

| Eating Disorders/Disordered Eating | 322 | 63.4 |

| General Psychiatry/Mental Health | 68 | 13.4 |

| Nutrition/Diet/Food | 43 | 8.5 |

| Obesity | 13 | 2.6 |

| Prevention/Policy | 10 | 2.0 |

| Primary Care | 15 | 3.0 |

| Other | 22 | 4.3 |

| Primary Title (n = 507) | ||

| Clinician | 323 | 63.7 |

| Director or Executive | 4 | 0.8 |

| Faculty | 59 | 11.6 |

| Graduate Student | 62 | 12.2 |

| Postdoctoral Fellow/Scholar | 17 | 3.4 |

| Researcher/Research Assistant | 23 | 4.5 |

| Other | 19 | 3.7 |

| Primary Role (n = 504) | ||

| Administrative | 31 | 6.2 |

| Clinical | 327 | 64.9 |

| Education | 35 | 6.9 |

| Research | 98 | 19.4 |

| Other | 13 | 2.6 |

| Location of Work2 (n = 491) | ||

| Rural | 38 | 7.7 |

| Sub-Urban | 107 | 21.8 |

| Urban | 346 | 70.5 |

| Client Population1 | ||

| Adolescent | 326 | 63.7 |

| Adult | 375 | 73.2 |

| Child | 152 | 29.7 |

| Older Adult | 114 | 22.3 |

| Young Adult | 276 | 53.9 |

Note:

Individuals may have more than one response.

Rural, Sub-Urban, and Urban were not defined for respondents.

PhD = Doctor of Philosophy; MD = Doctor of Medicine

Perceived Barriers to Increasing Diversity

Among the survey respondents, 292 (57.0%) answered the open-ended question. Sensitivity analyses were completed to examine differences between those who did and did not respond to the qualitative question. Individuals who responded to the qualitative question were more likely to have a history of an ED compared to those who did not respond to the qualitative question (70.9% versus 29.1%), χ2(1) = 10.72, p = .001. There were no other significant differences between those who did and did not respond to the qualitative question.

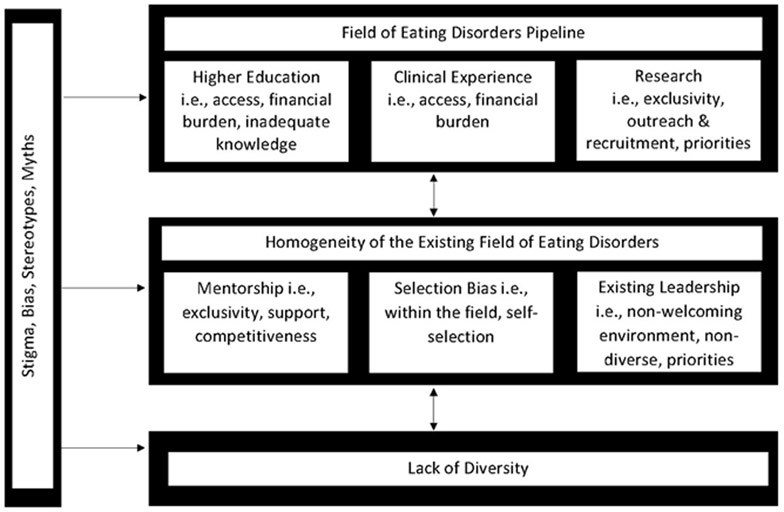

A small subset of individuals (n = 4) reported that they were not aware of diversity in the field of ED as an issue (e.g., “I was not aware this was an issue”). Some participants shared concerns about focusing on or imposing diversity with statements such as “diversity without cause is reckless” or “stop focusing on what is different about us and focus on what is similar.” However, most respondents discussed perceived barriers to increasing diversity. An overarching theme was “stigma, bias, stereotypes, myths.” Two additional themes emerged from the data, “field of ED pipeline” and “homogeneity of the existing field of ED”, and both were influenced by the overarching theme. Figure 2 provides a framework for relations among themes and subthemes. Online Supplementary Tables (Table 1) provide a detailed description of themes and subthemes with supporting quotations from respondents that exemplify the way in which the themes and subthemes were expressed by participants.

Figure 2.

Theoretical Model for Perceived Barriers to Increasing Diversity in the Field of Eating Disorder

“Stigma, Bias Stereotypes, Myths”

Most participants reported that stigma, bias, stereotypes, and/or myths were barriers to increasing diversity in the ED field. Most respondents did not define these constructs and thus definitions are not provided. In fact, most participants wrote “stigma,” “bias,” “stereotypes,” and/or “myths” as responses, or wrote brief responses like “weight stigma,” “cultural stigma,” “stigma of ED,” and “ED stereotypes.”

Respondents reported how stigmas and biases are barriers to increasing diversity. One respondent wrote “internalized and unexamined weight, racial, socioeconomic, ableist, etc. biases. If we are not willing to acknowledge our biases, we cannot improve them!” Moreover, participants addressed both stigma against providers who do not fall into a normal weight range and provider bias against clients who do not fall into a normal weight range. For example, one participant wrote “patients sometimes distrust clinicians who appear overweight/obese and say, ‘you’re trying to make me fat like you.” Another respondent wrote “systematic bias against larger bodied providers being able to provide treatment.” Yet another respondent wrote “clinician bias in diagnosis, researcher bias in study design e.g., focus on ‘established’ diagnostic categories (AN [anorexia nervosa], BN [bulimia nervosa] at the expense of exploratory work in ED-NOS [eating disorders-not otherwise specified] areas).”

Participants articulated how stereotypes and myths about ED impact diversity in this field. For example, one person wrote “the stereotypical images we see when EDs are discussed,” and another participant wrote “myths about eating disorders amongst practitioners.” Indeed, most respondents discussed how stereotyped views of individuals with ED as White, affluent, thin females from Western societies who are difficult to treat contribute to the persistent societal stereotypes and myths of ED and perpetuate such views among all stakeholders (e.g., providers, educators, researchers, clients). For example, one respondent wrote “old stereotypes about EDs that make people think they only present in a ‘certain’ way.”

The overarching theme of “stigma, bias, stereotypes, myths” was an indirect barrier to increasing diversity in the ED field via the two themes: “field of eating disorder pipeline” and “homogeneity of the existing field of eating disorders.” For example, several participants expressed how societal stereotypes and myths about ED impact access to education, research and training and those who seek a career in the field of ED. One respondent wrote how “training programs [are] organized around wealthy thin White people.” Yet another respondent wrote “Grad school reinforcement of the myth that EDs affect upper SES, White, cis-gendered young women further dissuades diverse individuals from becoming interested.”

Field of Eating Disorders Pipeline

The theme “field of eating disorders pipeline” reflects the significance that respondents placed on education, clinical experience, and research. Participants described how the significant financial burden and access to higher education and clinical experiences were barriers to increasing diversity in the field. For example, one individual wrote that barriers to increasing diversity included “the cost of higher education, particularly the tracks that lead one into advanced education (i.e., many years of education, low or no-pay jobs for experience, conference fees and associated travel).” Another person wrote that “education is very expensive and prohibitive to people from a low socioeconomic status.” Yet other individuals spoke to the access and financial burden of training. For example, a respondent wrote, “Access to training from economic and availability perspectives…is limited even among White individuals from Western societies” and another respondent wrote “…less capacity for offering clinical services and trainings in languages other than English, specialty training typically required (not unique to the field of ED).” Furthermore, individuals addressed how inadequate knowledge (e.g., lack of exposure, outdated information, limited emphasis on assessment and treatment) was a barrier to increasing diversity. Respondents wrote statements such as “I am continually shocked by the lack of information and the incorrect and outdated information that grad schools teach their students about ED.” Moreover, some individuals articulated how exclusivity and limited outreach and recruitment also contributed to lack of diversity in this field. For example, one person responded, “Recruiting applicants from diverse backgrounds…almost all individuals who apply to work with us are female.” Other respondents articulated how research primarily focuses on English speaking and Western societies and the need for an emphasis on linguistic and cultural diversity in research. Another participant wrote “hospitals/treatment centers not willing to hire non-Caucasian individuals.”

Homogeneity of the Existing Field of Eating Disorders

The theme, “homogeneity of the existing field of eating disorders,” encompassed the perceived impact of mentorship, selection bias, and the existing leadership on diversity. First, although respondents valued mentorship, they expressed limited support, encouragement, and pathways for diverse populations. One person wrote, “there is a lack of encouragement and pathways for men to be engaged in this area.” Moreover, the competitiveness of seeking mentorship was viewed as another barrier to increasing diversity. For example, respondents discussed how they sought out mentors in the field, and one participant wrote “[there is a] lack of supportive resources to coach and assist those who are interested but need the additional courage and support to do the work.” Second, respondents discussed how the current homogeneity and exclusivity of the field are barriers to increasing diversity. One respondent wrote “…the current homogenous make-up of the field requires those who do not fit the mold to be especially courageous.” Another person wrote, “it is a small and sometimes exclusive field. In that kind of situation, I think it is easy to stay stuck in the perspective of the existing group.” Indeed, other participants articulated how such homogeneity and exclusivity contributes to self-selection. For example, several respondents wrote how this field “seems to attract a specific sort of person” and one person wrote, “academia and clinical psychology are not always welcoming to minority groups, can feel left out.” Finally, participants discussed how the existing leadership does not prioritize diversity. One respondent wrote, “[we] need policy development among the professional bodies to ensure diversity is a key strategic area for development.” Other participants wrote about how the existing leadership is a barrier, including “unrecognized bias and prejudice by current gatekeepers,” “professional backgrounds not being recognized,” “Eurocentric beliefs” and “clinical and educational elitism.” Some participants even expressed the need to be a more welcoming field, “…showing the need for clinicians from diverse backgrounds. Letting them know they are needed and welcomed in the field.” Furthermore, individuals discussed how limited demographic and professional diversity exists among the leaders of the field. For example, many respondents articulated that White women are the majority in the field and White men tend to be in positions of power (e.g., the leaders, hold top level positions in academia, research, and business).

Overall, qualitative data indicated that the overarching theme “stigma, bias, stereotypes, myths,” was a direct barrier to increasing diversity in the ED field as well as an indirect barrier to increasing diversity through its impact on the themes “field of ED pipeline” and “homogeneity of the existing field of ED.” Indeed, most respondents wrote how explicit (e.g., not willing to hire non-Caucasians) and implicit (attitudes/stereotypes that affect understanding, actions, and decisions in an unconscious manner) bias and unconscious and automatic stereotyping contribute to the persistent challenge of diversifying the ED field via numerous pathways.

Discussion

This study provides novel information about the diversity (or lack thereof) within the ED workforce, as well as factors that may facilitate the maintenance of the “status quo” in this field. Using a multi-methods approach, we documented that most participants were female, heterosexual, and White with a mean age of 41.1 years old. Most respondents were clinicians, had a Master’s degree or higher, worked in an urban setting, and had worked about 10 years in the ED field. Qualitative data revealed three themes that were direct or indirect barriers to increasing diversity in the field of ED: the overarching theme “stigma, bias, stereotypes, myths,” and the themes “field of ED pipeline” and “homogeneity of the existing field of ED.”

The demographic breakdown of the current sample was consistent with previous research examining ED professionals (Simmons et al., 2008; von Ranson & Robinson, 2006; Wallace & von Ranson, 2012). Indeed, across these studies, participants were mostly female, heterosexual, and White. Future research on the ED workforce may consider oversampling non-female, non-heterosexual, and non-White individuals. However, the average age of the current study’s participants was younger compared to ED professionals who were AED members (Barbarich, 2002; Simmons et al., 2008), ED clinicians in Canada (von Ranson & Robinson, 2006), and the U.S. psychology workforce (APA, 2018). In addition, there were some differences in education backgrounds, highest levels of completed education, and client populations in the current study relative to prior studies (see Online Supplementary Tables, Table 2). It is possible that these differences are attributable to the recruitment methods and broader scope of the current study (e.g., numerous professional organizations, international, inclusive of students and postdoctoral fellows/scholars, snowball sampling), as well as the younger ED workforce having an increased willingness to participate and placing a higher value on diversity. In fact, research suggests that younger generations are more likely to consider the diversity and inclusion of the workplace when considering a new job, and are more comfortable discussing diversity and inclusion issues at work compared to older generations (Kochhar, 2016). Furthermore, although relatively small percentages of racial/ethnic/national minorities have been reported in recent studies within the ED field, the number of racial/ethnic/national minority healthcare providers continues to increase worldwide (Buchan et al., 2017; Spinks & Moore, 2007). Future research and initiatives to follow this trend and increase diversity among the ED workforce are crucial to the continued development of culturally informed care.

Reflecting the qualitative data, respondents discussed numerous barriers to increasing diversity in the field. The overarching theme in the current study was stigma and bias (i.e., eating disorder, provider, weight and size) and stereotypes and myths about ED (i.e., White, affluent, female, Western societies, thinness, difficult to treat) that may directly and indirectly impact diversity in the ED field. Indeed, this overarching theme was perceived as being an indirect barrier to increasing diversity via the pipeline in the ED field and the homogeneity of the existing field.

First, the systematic barriers of financial burden and access to education and clinical experiences were frequently reported. Respondents reported that if individuals from diverse backgrounds do not have financial support and/or do not have access to education and/or clinical experiences (e.g., due to geographical location, language), the field is unable to adequately diversify across multiple facets including socioeconomic, nationality, race/ethnicity, gender, sexual identity, and age. Moreover, most training and clinical programs are primarily English speaking and located in urban areas and Western societies. Such limited access requires individuals to have financial security to learn English and/or relocate and thrive in an environment with more financial obligations. Limited access also perpetuates the societal stereotypes and myths of an ED as a health problem primarily among White, affluent, thin females from Western societies who are difficult to treat.

Second, barriers at the individual level were reported such as access to mentorship which is essential for admission to certain graduate programs. Research has shown that cultural similarities are significant in mentoring (Okawa, 2002) and individuals tend to identify with persons who are like themselves on salient identity group characteristics (Welch, 1996). Indeed, healthcare providers and academics have repeatedly reported how ethnic and gender differences in prior educational opportunities led to disparities in exposure to career options as well as qualifications for and subsequent recruitment to training programs and faculty positions (Kaplan et al., 2018; Price et al., 2005; WHO, 2019).

These systematic and individual barriers are not unique to the field of ED and have been an ongoing global issue in healthcare both in academia and clinical practice. Studies that examined faculty at different career stages have shown that race/ethnicity, foreign-born status, and gender provoked bias and cumulative advantages or disadvantages in the workplace (Kaplan et al., 2018; Pololi et al., 2010; Price et al., 2005; WHO, 2019). Minority faculty also described how structural barriers such as poor retention efforts and lack of mentorship hindered success and professional satisfaction after recruitment. Moreover, minority and foreign-born faculty reported ethnicity-based disparities in recruitment and subtle manifestations of bias in the promotion process. In addition, the WHO reported that females are 70% of the global health workforce but hold only 25% of senior roles; and, occupational segregation, discrimination and bias, and sexual harassment contribute to these gender-based disparities (WHO, 2019).

To our knowledge, this is the largest study about diversity in the ED workforce to date. We sampled from multiple disciplines (e.g., medicine, nursing, psychology, clinical nutrition) and multiple countries (n = 24) and took a wide lens view of diversity across several domains (e.g., personal and professional). However, several limitations may have impacted findings. First, the survey was administered in English only, which may have reduced response rates of individuals for whom English is not a primary language. Second, data were collected across different countries and issues of diversity may differ based on regions of the world (e.g., immigration status, language spoken). However, our U.S. American perspectives may have limited our ability to pose appropriate questions from other countries and non-Eurocentric cultures. For example, countries with high numbers of immigrant populations (representing a wide range of race/ethnicities) may have legal barriers that keep highly trained immigrants out of professions unless the immigrants pursue further training in a field for which they already had trained in their country of origin. Third, the survey was self-report and many questions were subjective in nature, which may have impacted responses and skewed findings. Fourth, the main recruitment strategy was through professional organizations, which generally cost money to join and, thus, consist of individuals later in their careers and/or with the financial means required to be members. Relatedly, only one quarter of organizations who were approached agreed to distribute the survey, and with snowball sampling, participants were more likely to recruit their acquaintances who mirror their demographics. Thus, representativeness of the sample was not guaranteed, and participants may have represented a small and nonrandom subgroup of the pool of potential respondents. Finally, because survey participation was voluntary, respondents may not comprise a representative sample of the organizations with which they are affiliated or the global ED workforce. Taken together, these limitations could have contributed to decreased representativeness of the data, further reflecting barriers to increasing diversity. Future research should consider what aspects of diversity are relevant and how to solicit participation from non-Eurocentric countries and continents.

Diversity encompasses a multitude of characteristics and is an important and under researched topic. Although it is not clear as to whether the findings from this study will directly impact the quality of ED treatment, research has shown that clients prefer health professionals with similar backgrounds to themselves (Cabral & Smith, 2011). Results from this study provide data about the current status of professionals in the ED field as it relates to different facets of diversity and confirms anecdotal experiences of many persons. Thus, these findings may further encourage professional organizations and current leaders in the ED field to engage in increasing diversity and prioritize decreasing barriers within our field and healthcare overall. First, we can appreciate our similarities and what connects this field, namely, our commitment to working with individuals with ED. Advocacy for universal screening of ED may help to decrease stigmas and bias as well as stereotypes and myths about ED that may directly and indirectly impact diversity in the field. Moreover, we can applaud the diversity that does exist and initiatives to promote diversity worldwide. Second, we must acknowledge that differences exist and both conscious and unconscious biases and beliefs influence the lack of diversity in the ED field. For example, organizers of national and international conferences and leaders in the ED field can use their platforms to directly explore conscious and unconscious biases and beliefs contributing to the lack of diversity in the ED field. Third, we can promote the recruitment and retention of individuals from more diverse backgrounds and create a culture of respect and humility to prepare the ED workforce for challenges of working with diverse peers and patient populations. Finally, we can continue to gain knowledge about how individual and contextual factors (e.g., discipline, department, institution, country) influence diversity and place the responsibility for change on the existing workforce and leadership. For example, future studies may consider using a convergent parallel mixed methods design to gain a more multidimensional understanding of diversity in the ED workforce.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (T32 MH082761, F32 HD089586, K01 DK116925). Results were presented at the 2019 International Conference on Eating Disorders and 2019 Eastern Nurses Research Society. The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- American Psychological Association. (2018). Demographics of the U.S. psychology workforce: Findings from the 2007–16 American Community Survey. https://www.apa.org/workforce/publications/16-demographics/report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Barbarich NC (2002). Lifetime prevalence of eating disorders among professionals in the field. Eating Disorders, 10(4), 305–312. 10.1080/10640260214505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker AE, Franko DL, Speck A, & Herzog DB (2003). Ethnicity and differential access to care for eating disorder symptoms. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 33(2), 205–212. 10.1002/eat.10129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchan J, Dhillon IS, & Campbell J (2017). Health employment and economic growth: An evidence base. https://www.who.int/hrh/resources/WHO-HLC-Report_web.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Cabral RR, & Smith TB (2011). Racial/ethnic matching of clients and therapists in mental health services: A meta-analytic review of preferences, perceptions, and outcomes. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(4), 537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan SE, Gunn CM, Kulukulualani AK, Raj A, Freund KM, & Carr PL (2018). Challenges in recruiting, retaining and promoting racially and ethnically diverse faculty. Journal of National Medical Association, 110(1), 58–64. 10.1016/j.jnma.2017.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Fitzsimmons-Craft EE, & Wilfley DE (2017). Addressing critical gaps in the treatment of eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 50(3), 170–189. 10.1002/eat.22670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochhar S (2016). Millennials@Work: PerspecGves on diversity & inclusion. https://instituteforpr.org/millennialswork-perspectives-diversity-inclusion/

- Marques L, Alegria M, Becker AE, Chen CN, Fang A, Chosak A, & Diniz JB (2011). Comparative prevalence, correlates of impairment, and service utilization for eating disorders across US ethnic groups: Implications for reducing ethnic disparities in health care access for eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 44(5), 412–420. 10.1002/eat.20787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okawa G (2002). Diving for pearls: Mentoring as cultural and activist practice among academics of color. College Composition and Communication, 53, 507 10.2307/1512136 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polit DF, & Beck CT (2017). Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice (10th ed.). Wolters Kluwer. [Google Scholar]

- Pololi L, Cooper LA, & Carr P (2010). Race, disadvantage and faculty experiences in academic medicine. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 25(12), 1363–1369. 10.1007/s11606-010-1478-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price EG, Gozu A, Kern DE, Powe NR, Wand GS, Golden S, & Cooper LA (2005). The role of cultural diversity climate in recruitment, promotion, and retention of faculty in academic medicine. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 20(7), 565–571. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0127.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M (2000). Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing and Health, 23(4), 334–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M (2010). What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Research in Nursing and Health, 33(1), 77–84. 10.1002/nur.20362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons AM, Milnes SM, & Anderson DA (2008). Factors influencing the utilization of empirically supported treatments for eating disorders. Eating Disorders, 16(4), 342–354. 10.1080/10640260802116017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinks N, & Moore C (2007). The changing workforce, workplace and nature of work: Implications for health human resource management. Nursing Leadership, 20(3), 26–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DC (1999). Cultural diversity and work group effectiveness: An experimental study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 30(2), 242–263. 10.1177/0022022199030002006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2014). Diversity and inclusion: Valuing diversity and building a better workplace. https://www.census.gov/about/census-careers/diversity.html

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, & National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. (2017). Sex, race, and ethnic, diversity of U.S. health occupations (2011–2015). https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bhw/nchwa/diversityushealthoccupations.pdf [Google Scholar]

- von Ranson KM, & Robinson KE (2006). Who is providing what type of psychotherapy to eating disorder clients? A survey. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 39(1), 27–34. 10.1002/eat.20201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace LM, & von Ranson KM (2012). Perceptions and use of empirically-supported psychotherapies among eating disorder professionals. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50(3), 215–222. 10.1016/j.brat.2011.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch N (1996). Revising a writer’s identity: Reading and “re-modeling” in a composition class. College Composition and Communication, 47(1), 41–61. 10.2307/358273 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2006). Working together for health: The World Health Organization report; https://www.who.int/whr/2006/whr06_en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization; (2019). Delivered by women, led by men: A gender and equity analysis of the global health and social workforce. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/311322/9789241515467-eng.pdf?ua=1 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.