Abstract

Radiation-induced cognitive dysfunction (RICD) is a progressive and debilitating health issue facing patients following cranial radiotherapy to control CNS cancers. There has been some success treating RICD in rodents using human neural stem cell (hNSC) transplantation, but the procedure is invasive, requires immunosuppression, and could cause other complications such as teratoma formation. Extracellular vesicles (EV) are nano-scale membrane-bound structures that contain biological contents including mRNA, microRNA, proteins, and lipids that can be readily isolated from conditioned culture media. It has been previously shown that hNSC-derived EV resolves RICD following cranial irradiation using an immunocompromised rodent model. Here we use immuno-competent wild type mice to show that hNSC-derived EV treatment administered either intravenously via retro-orbital vein injection or via intracranial transplantation can ameliorate cognitive deficits following 9 Gy head-only irradiation. Cognitive function assessed on the Novel Place Recognition, Novel Object Recognition, and Temporal Order tasks was not only improved at early (five weeks) but also at delayed (six months) post-irradiation times with just a single EV treatment. Improved behavioral outcomes were also associated with reduced neuroinflammation as measured by a reduction in activated microglia. To identify the mechanism of action, analysis of EV cargo implicated miRNA (miR-124) as a potential candidate in the mitigation of RICD. Furthermore, viral vector-mediated overexpression of miR-124 in the irradiated brain ameliorated RICD and reduced microglial activation. Our findings demonstrate for the first time that systemic administration of hNSC-derived EV abrogates RICD and neuroinflammation in cranially irradiated wild type rodents through a mechanism involving miR-124.

Keywords: Extracellular vesicles, Exosomes, Radiation-induced cognitive dysfunction, Neuroinflammation, Stem cells, miRNA

Introduction

Persistent, progressive and debilitating cognitive decline following cranial radiotherapy (RT) is a growing concern as survivorship increases with more efficacious brain tumor treatments. Treatment plans for brain and CNS metastases generally consist of surgical resection followed by RT and chemotherapy — collectively known as combination therapy (1). Systemic or focal RT can elicit a range of associated pathologies in the brain including changes to the vascular bed, neurogenesis, mature and immature neuronal structure damage, inflammatory responses, and expression of neurotrophic factors (2). As a result, the majority of survivors who received cranial RT report a range of degenerative sequelae including difficulties in learning and memory, attention, executive function, decision-making, and mood, that typically manifest late after treatment and progressively deteriorate over time (3). In pediatric cases, resultant cognitive impairments that significantly reduce quality of life are particularly problematic since long-term survival rates are high (4–6). Despite improvements in therapeutic outcome, radiation-induced cognitive dysfunction (RICD) remains a critical unmet medical need that adversely affects an ever-growing patient base without any therapeutic recourse.

Previous work from our laboratory has pioneered the use of transplanted multi- and pluripotent human stem cells to ameliorate a variety of radiation-induced normal tissue injuries including neurocognitive decline. Our past data have shown that intracranial (IC) transplantation of human neural stem cells (hNSCs) between 2 and 30 days following irradiation ameliorated cognitive deficits, reduced neuroinflammation, and preserved neuronal architecture in athymic nude (ATN) rats (7–10). While stem cell transplantation strategies remain a promising therapeutic approach, caveats for translating this technology to the clinic include the requirement for cranial surgical procedures, the need for immunosuppression (11), and the risk for teratoma formation (12,13). To address these caveats we subsequently demonstrated that intrahippocampal transplantation using hNSC-derived extracellular vesicles (EV) was equally as efficacious in ameliorating the effects of cranial irradiation in immunocompromised ATN rats (14,15). In these studies, grafted EV were found to mitigate a range of radiation-induced pathologies in the brain, including cognitive dysfunction, neuroinflammation and reductions in the structural complexity of neurons and synaptic integrity. While it was striking that EV were functionally equivalent to the transplanted stem cells in resolving RICD, literature did suggest that the secretome, rather than cell replacement, could be the dominant therapeutic mechanism driving the beneficial outcomes following stem cell transplantation (16–20).

EV is a broad term used to describe a variety of nano-scale membrane-bound structures often referred to as exosomes or microvesicles depending on size and mechanism of synthesis that are secreted by cells and that can participate in paracrine and endocrine signaling (21)https://paperpile.com/c/w8ZDqH/x6q7. Contents of EV include lipids, nucleic acids (e.g. genomic DNA, microRNAs (miRNAs), mRNAs), proteins, and in some cases mitochondria (22). Based on the evidence available to date, miRNAs are considered to be critical functional cargo within EV given that a single miRNA is capable of impacting multiple gene targets and signaling pathways (23). EV are recognized as specialized long distance mediators of intercellular communication and the small size and lipid-heavy composition of the particles facilitates their translocation across the blood-brain barrier (BBB, (24,25)), ideally suiting them to deliver their bioactive cargo into select target cell populations in the brain. The substitution of EV for stem cells to resolve RICD has several distinct advantages including: 1) eliminating the risk of teratoma formation, 2) minimizing complications associated with immunogenicity (26) and 3) providing a more amenable systemic route of administration that negates the need for invasive surgical procedures. In this study, we have treated immunocompetent, cranially irradiated mice with hNSC-derived EV to demonstrate proof of principle for the potential translational benefits of EV treatment as a safe and non-invasive strategy for long-term amelioration of RICD. We further report that analysis of EV miRNA cargo identified miR-124, a candidate molecule that we validate to be capable of mitigating RICD and neuroinflammation when overexpressed in vivo following cranial irradiation.

Materials & Methods

hNSC Culture and EV Isolation and Characterization.

The use of hNSC was approved by the Institutional Human Stem Cell Research Oversight Committee (HSCRO). The validation, expansion, and characterization of hNSCs (ENStem-A; EMD Millipore) followed previously published procedures (7,27). EV were isolated and purified from conditioned hNSC culture medium by ultracentrifugation (28) and characterized using a nano-particle analyzer (ZetaView PMX 110; Meerbusch, Germany). The ENStem conditioned media yielded 4.19 × 108 EV with a size distribution of 118.6-± 59.1 nm (diameter). These purified EV were used for all of the experiments described.

Animal Irradiation and Transplant Surgeries.

All animal procedures described in this study were in accordance with NIH guidelines and approved by the University of California Irvine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Four to five month old wild type male mice (C57BL/6, Jackson Laboratories) were maintained in standard housing conditions (20°C ± 1°C; 70% ± 10% humidity; 12 h:12 h light and dark cycle) and provided ad libitum access to food (Envigo Teklad 2020x) and water. For all studies, mice were immobilized and subjected to 9 Gy cranial irradiation using a 137Cs γ irradiator at a dose rate of 2.07 Gy/min (Mark I, J.L. Sheppard and Associates, CA, USA). Concurrent control mice were immobilized and placed into the irradiator for the same length of restraint and exposure time as that required to deliver the 9 Gy dose. Experimental design is shown in a schematic (Fig. 1A)

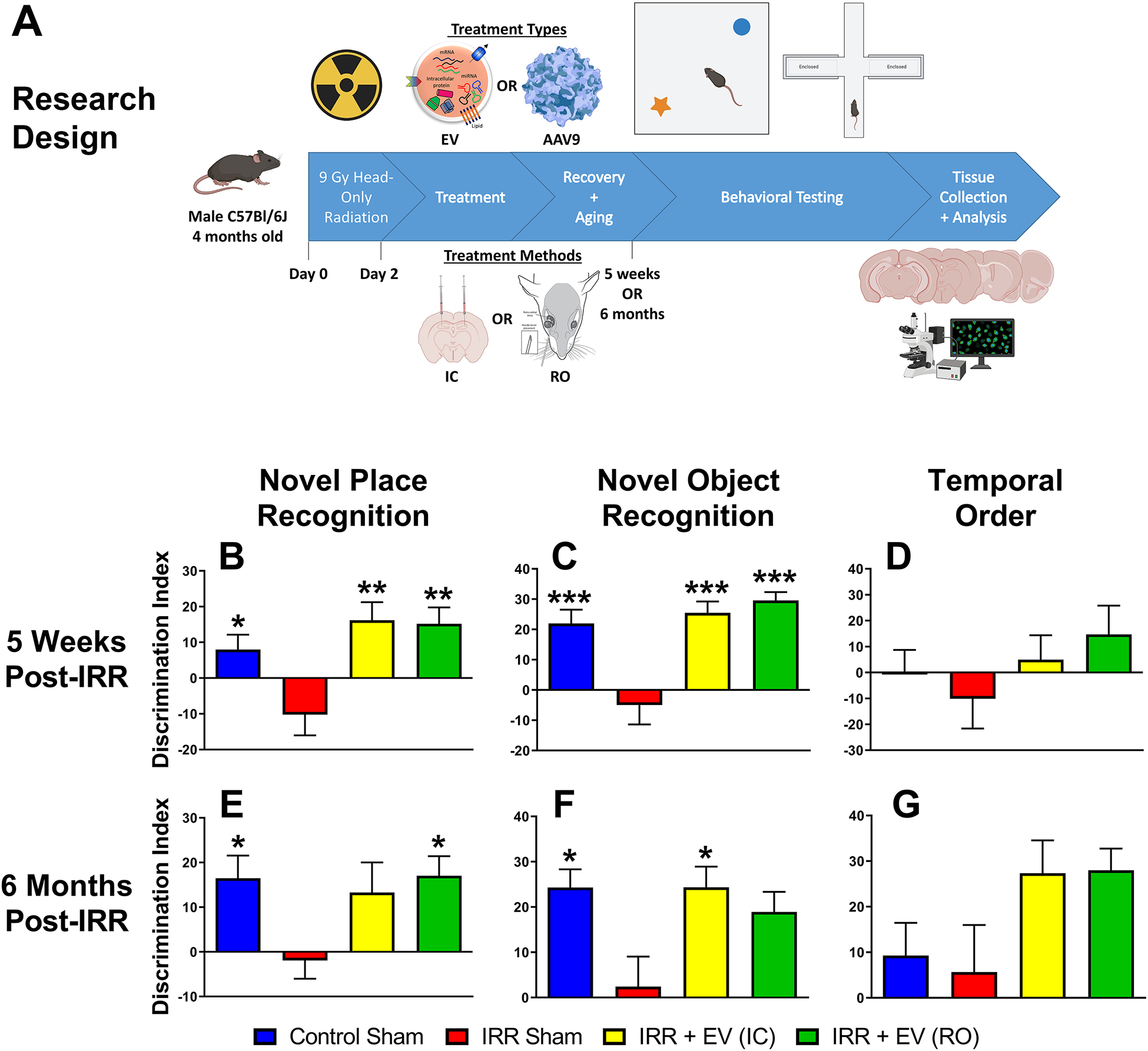

Figure 1. Stem cell-derived EV protect against radiation-induced cognitive dysfunction at five weeks and six months post irradiation.

The experimental design for the present studies is shown (A). Four-month-old male C57Bl/6J mice were immobilized and subjected to 9 Gy cranial irradiation using a 137Cs γ irradiator at a dose rate of 2.07 Gy/min. Two days later mice were treated intracranially or retro-orbitally with EV or miR-124 AAV9 particles. At five weeks and six months post-irradiation, animals were administered spontaneous exploration tasks in the following order: NPR (B, E), NOR (C, F) and TO (D, G). The tendency to explore novelty (novel place or object) was calculated using the discrimination index [(novel location exploration time/total exploration time) – (familiar location exploration time/total exploration time)] × 100. All data are presented as mean ± SEM (N=10–14 mice per group). * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001 compared to the IRR group; P values are derived from one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons.

EV cohort.

A single cohort of mice was randomly assigned to the following 4 experimental groups (100 mice total, N = 24–26/group): Control (sham irradiated receiving intra-cranial, IC, vehicle injection), Irradiated (IRR) sham (receiving IC vehicle), EV-treated using IC surgeries (EV IC), and EV-treated using retro-orbital (RO) vein injections (EV RO). At 48 hours following irradiation, mice were sedated and maintained on 2.5% (v/v) isoflurane/oxygen and subject to stereotactic intrahippocampal EV-grafting surgery (EV IC group), or EV therapy delivered through circulation via the retro-orbital sinus (EV RO group). IC was performed using a 33-gauge microsyringe at an injection rate of 0.25 μl/min. Each hippocampus received 2 distinct injections of EV per hemisphere in an injection volume of 2 μl (EV in sterile hibernation buffer) per site for a total of 4 injections (8 μl) and a total dose of 6.70 × 106 EV per animal. Bilateral stereotactic coordinates from the bregma were anterior-posterior (AP): −1.94, mediolateral (ML): ±1.25, dorsal-ventral (DV): −1.5 for the first site and AP: −2.60, ML: ±2.0, and DV: −1.5 for the second site. Control sham mice underwent IC procedures and received an equivalent injection of vehicle. To administer EV via RO, mice were similarly sedated and 6.98 × 106 EV in 50 μl of hibernation buffer were delivered into circulation via the RO injection.

miR-124 AAV cohort.

Prior to surgery, miR-124 and miR-scramble were cloned into an AAV vector and efficacy of constructs were tested in vitro and then packaged into AAV9 viral particles (SignaGen Laboratories, NJ). AAV9 particles were purified and titrated via qPCR before suspending into sterile calcium- and magnesium-free PBS for injection. A single cohort of mice was randomly assigned to the following 4 experimental groups (N = 12 mice/group): 0 Gy + AAV9-miR-Scr, 0 Gy + AAV9-miR-124, 9 Gy + AAV9-miR-Scr, and 9 Gy + AAV9-miR-124. At 48 hours following irradiation, mice were sedated and maintained on 2.5% (v/v) isoflurane/oxygen and subject to stereotactic intrahippocampal AAV9 injections using a 33-gauge microsyringe at an injection rate of 0.25 μl/min. Each hippocampus received 2 distinct injections per hemisphere in an injection volume of 1 μl viral particles per site for a total of 4 injections (4 μl) per animal. Bilateral stereotactic coordinates were the same as described above. The dose was approximately 3.5 × 1010 viral genomes (VG) per site and 1.4 × 1011 VG per animal.

Cognitive Testing.

To determine the effect of both treatments on cognitive function after irradiation, mice were subject to behavioral testing five weeks after irradiation. A cohort of EV-treated mice were tested at six months post-irradiation as well. The five-week EV cohort had 12 animals/group, and the six-month EV cohort had 10 animals/group except the EV RO group which had 14. The miR-124 cohort had 10–11 animals/group. Testing occurred over five weeks.

Open field testing.

Three open field, spontaneous exploration tasks were used in the following order: Novel Place Recognition (NPR), Novel Object Recognition (NOR), and Temporal Order (TO). These tasks rely on intact hippocampus, medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and perirhinal cortex function. The NPR and NOR tasks evaluate the preference for novel location and object, respectively, in a test of episodic memory, while the TO task provides a measure of recency memory. Tasks were conducted as described previously (29) and all trials were scored by observers blind to the experimental groups to avoid bias. The average of those scores was used to determine performance, defined as a discrimination index (DI) and calculated as [(novel location exploration time/total exploration time) – (familiar location exploration time/total exploration time)] × 100.

Elevated plus maze (EPM).

The EPM provides a measure of anxiety-like behaviors in rodents that can be linked to the amygdala, by quantifying the time spent and number of entries into the open versus closed arms of an elevated maze arranged as a symmetrical cross. The established anxiety-related indices for this test are the percentage of time spent in the open (uncovered) arm and the percentage of entries into the open arm. This test was not performed on the miR-124 cohort.

Light/dark box (LDB) exploration test.

The LDB exploration test assesses anxiety in rodents. The light-dark test utilizes an arena (45 × 30 × 27 cm) where one-third of the box is a dark compartment and the other two-thirds is a well-lit compartment. The light and dark compartment were connected via a small opening (7.5 × 7.5 cm) that allowed the mice to freely move between the light and dark compartments. The light intensity measured in the light chamber was 900 lux and 4 lux in the dark chamber. Mice were placed at the center of the light compartment facing opposite to the small opening. The number of transitions between the compartments and the total time spent in the light compartment was recorded to quantify performance on this 10 min test. Entry into a chamber was defined as all 4 paws crossing into the chamber. This test was not performed on the miR-124 cohort.

Fear extinction testing.

To determine whether mice could learn and later extinguish conditioned fear responses, we performed a series of fear extinction (FE) assays modified to be reliant on hippocampal function (30). Testing occurred in a behavioral conditioning chamber (17.5 × 17.5 × 18 cm, Coulbourn Instruments) with a steel slat floor (3.2 mm diameter slats, 8 mm spacing). The chamber was scented with a spray of 10% acetic acid in water. Initial fear conditioning (FC) was performed after mice were allowed to habituate in the chamber for 2 min. Three pairings of an auditory conditioned stimulus (16 kHz tone, 80 dB, lasting 120 sec; CS) co-terminating with a foot shock unconditioned stimulus (0.6 mA, 1 sec; US) were presented at 2 min intervals. On the following 3 days of extinction training, mice were presented with 20 non-US reinforced CS tones (16 kHz, 80 dB, lasting 120 sec, at 5 sec intervals) at 2 min intervals. On the final day of fear testing, mice were presented with only 3 non-US reinforced CS tones (16 kHz, 80 dB, lasting 5 120 sec) at 2 minute intervals. Freezing behavior was recorded with a camera mounted above the chamber and scored by an automated measurement program (FreezeFrame, Coulbourn Instruments). This test was not performed on the miR-124 cohort.

Immunohistochemistry, confocal imaging and analysis.

After completion of behavioral testing, mice were deeply anesthetized using isoflurane and euthanized via intercardiac perfusion using 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma) in 100 mM phosphate buffered saline (PBS, 100 mM, pH 7.4; Gibco). Brains were cryoprotected using a sucrose gradient (10–30%, Sigma) and sectioned coronally into 30 μm thick sections using a cryostat (Microm HN 525 NX, Thermo-Scientific, US). For each endpoint 3–4 representative coronal brain sections from each of 4–6 animals per experimental group were selected at approximately 15 section intervals to encompass the rostro-caudal axis from the middle of the hippocampus and stored in PBS. Free floating sections were first rinsed in PBS, blocked for 30 min in 4% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma) and 0.01% Triton (TTX, Sigma). For the immunofluorescence labeling of post-synaptic density 95 (PSD-95) and microglial activation marker CD68, mouse anti–PSD-95 (Thermo Scientific; 1:1,000) and rat anti-mouse CD68 (1:500; AbD Serotec) primary antibodies were used with Alexa Fluor 594 secondary antibody (1:1,000). For immunofluorescence labeling of pan microglial marker Iba1, rabbit anti-Iba1 (Wako Chemicals USA; 1:500) primary antibody was used with donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibody (1:500). Tissues were then DAPI nuclear counterstained (1 μmol/L) and mounted using slow fade/antifade mounting medium (Life Technologies). Confocal analyses were carried out using multiple z stacks taken at 1-mm intervals through the 25–30 μm section using a laser scanning confocal microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ti-C2 interface). Individual z stacks were then analyzed using Nikon Elements AR software (version 3.0). Images were deconvoluted using AutoQuant X3 and surface analysis was performed with Imaris version 9.2 (31).

EV Labeling, Tracking, and Imaging.

For in vivo tracking, EV were labeled with the fluorescent dye PKH26 (Sigma-Aldrich) the day before transplantation. The EV were then resuspended in Diluent C and incubated with Dye Solution for 2 min with intermittent mixing as per the manufacturer’s protocol. The dye was quenched with 1% bovine serum albumin in water, and EV were isolated through ultracentrifugation (28) and washed. EV were administered to mice using stereotactic intrahippocampal injections or retro-orbital injections (as described above). At 48 hours post-surgery, animals were anesthetized, PFA perfused, and brains sectioned as described above. Following DAPI counterstain, sections were mounted onto slides and covered using antifade gold and cover slips. As before, imaging was done using a Nikon Eclipse Ti-C2 laser-scanning confocal microscope. Images were deconvoluted using AutoQuant X3 and processed with Imaris version 9.2.

MicroRNA microarray.

EV were lysed using Qiazol and miRNA isolated using the Qiagen miRNeasy kit as per the manufacturer’s protocol (Qiagen,CA). Samples were analyzed for integrity and concentration (NanoDrop; 260/280 ratio > 1.6 and 260/230 ratio > 1.5), then processed and analyzed in duplicate on a miRNA microarray chip (Exiqon, Denmark; Genomics Shared Resource at the University of Texas South Western Medical Center). Results were delivered as a spreadsheet of miRNA IDs and their associated expression values. Negative control probes were included for determination of significant hits. Another spreadsheet provided was filtered for probes that had duplicate measurements with less than 15% coefficient of variation (CV) and at least three standard deviations greater than the negative control probes.

Validation of EV MicroRNA.

Validation of miRNA array data was performed using TaqMan Advanced miRNA Assays (ThermoFisher, MA). Total RNA was extracted from EV using the RNA miniprep kit (Zymo Research Corp., CA). RNA template was then ligated to adaptors and pre-amplified using the TaqMan Advanced miRNA cDNA Synthesis Kit (ThermoFisher) as per the manufacturer’s protocol to obtain the cDNA template for classical qPCR using specific TaqMan Advanced miRNA Assays (ThermoFisher) which are primers specific to the target miRNA. Duplicate reactions were set up in a 96-well plate with no-template controls (MilliQ water instead of total RNA was used for cDNA synthesis process) included for each assay. Cycling was performed in the CFX96 (BioRad Laboratories, Inc., CA). qPCR data was visualized and processed using CFX Manager software (BioRad Laboratories, Inc., CA).

Data analysis.

Statistical data analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism (v6). One-way ANOVA was used to assess significance between groups. When overall group effects were found to be statistically significant, a Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was used to compare all other groups to the IRR or 9 Gy + miR-Scr group. All analyses considered a value of P ≤ 0.05 to be statistically significant.

Results

Stem cell-derived EV treatment resolves RICD

Five weeks after irradiation and EV treatment, animals underwent behavioral testing (Fig. 1). The NPR test showed a significant overall group effect in DI between the groups (F(3,44) = 6.13; P = 0.0014). The IRR group mean was −10.2% which was lower than the control (mean = 7.99%), EV IC (mean = 16.2%), and EV RO (mean = 15.2%) groups (Fig. 1B). The difference in the mean DI was statistically significant between the IRR group and the control group (P = 0.033) and the EV-treated groups (EVIC: P = 0.0014; EVRO: P = 0.0021). Similarly, a significant group effect was found for the NOR test (F(3,43) = 11.49; P < 0.0001). The IRR group had a mean DI of −4.98%, whereas the control group (mean = 22.0%) and both of the EV treatment groups had higher mean DI values (EV IC: mean = 25.5%; EV RO: mean = 29.6%) (Fig. 1C). For this test all of the differences were statistically significant between the IRR group and the control (P = 0.0004), EVIC (P < 0.0001) and EV RO (P < 0.0001) groups. While no significant differences were observed in the TO test, the DI for the IRR group (mean = −10.1%) was lower than the control (mean = 0.228%) and both EV treatment groups (EV IC: mean = 4.98%; EV RO: mean = 14.7%) (Fig. 1D). Total explorations times were not found to differ across the experimental cohorts, suggesting that treatment did not reduce locomotion or induce neophobic behavior to confound the findings (Supp. Table 1).

To determine the persistence of the neurocognitive benefits of EV treatment, a second group of animals was administered the same spontaneous exploration tasks at six months post-IRR (Fig. 1E–G). The NPR test revealed a mean DI for the IRR group of −1.91%, while the DI of the control (mean = 16.5%), EV IC (mean = 13.3%), and EV RO (mean = 17.0%) groups were higher. A significant overall group effect was found between mean DIs for this task (F(3,39) = 2.95, P = 0.044). The mean differences in DI between the IRR group and the control and EV RO groups were statistically significant (Fig. 1E; P = 0.048 and P = 0.028, respectively). Similarly, the NOR test demonstrated mean DI of 24.3%, 24.3%, and 18.9% for the control, EV IC, and EV RO groups, respectively, compared to 2.41% for the IRR group. A significant overall group effect for the mean DI between groups was also observed for NOR (F(3,40) = 3.98; P = 0.014). The mean DI differences between the control and EV RO groups and the IRR group were both statistically significant (Fig. 1F; P = 0.014 and P = 0.013, respectively), while the mean DI difference between IRR group and EV RO group was near the threshold for statistical significance (P = 0.052). Lastly, the TO test did not reveal significant differences in DI between the control (mean = 9.29%) and IRR (mean = 5.66%) groups, though the EV treated groups did exhibit higher preferences for novelty (EV IC: mean = 27.4%; EV RO: mean = 28.0%) (Fig. 1G). The overall TO group effect for mean DIs did not reach significance (F(3,34) = 2.65, P = 0.065). As with the five-week tasks, total exploration times were not found to differ significantly between any of the groups indicating that irradiation impaired episodic memory rather than disrupting locomotor activity (Supp. Table 1).

To determine the effect of irradiation and EV treatments on anxiety-like behavior, the animals underwent testing on the Elevated Plus Maze (EPM) at both five weeks and six months post-irradiation. While no differences were observed at the early time point (Supp. Fig. 1A), at six months post-treatment, anxiety-like behavior was increased in the IRR group (mean = 0.714) compared to the control group (mean = 0.571; P = 0.058), but to a lesser extent when compared to the EV treated groups (EV IC: mean = 0.649; EV RO: mean = 0.676) (Supp. Fig. 1B). As a second measure of anxiety-like behavior, mice were also subjected to the LDB exploration test. As with the EPM, the LDB test measures an animal’s unconditioned response, where an anxious mouse will spend more time in the dark compartment of the arena than in the light compartment, and less time moving freely between the two compartments. No significant group effects were observed at either five weeks or six months post-treatment (Supp. Fig. 1C–D).

In the final behavioral assessment, mice were subjected to a hippocampal-dependent FC and FE task. During the conditioning phase of the task, all of the groups learned to associate the tone (conditioned stimulus) to the subsequent foot shock (unconditioned stimulus) as measured by freezing behavior (i.e. not moving) (Supp. Fig. 1E,G; T1-T3). For the five-week cohort, the mean level of freezing at T3 was over 40% for all groups and no significant differences were found between groups. Similarly, the five-week cohort exhibited no significant differences between groups during the subsequent 3 day extinction training period, as measured by a gradual decrease in the percent time spent freezing (Supp. Fig. 1E). On the final extinction test day, however, there was a trend for a higher level of freezing in the IRR group (mean = 15.0%) compared to the control (mean = 8.63%) and the EV treated groups (EV IC: mean = 6.59%; EV RO: mean = 10.2%), although this did not reach statistical significance (Supp. Fig. 1F). At the six-month time point, all groups were subjected to the same testing paradigms and were found to be conditioned to a level of freezing of 30% at T3. At this later time, neither the extinction training sessions nor final extinction test showed significant differences among cohorts (Supp. Fig. 1G,H).

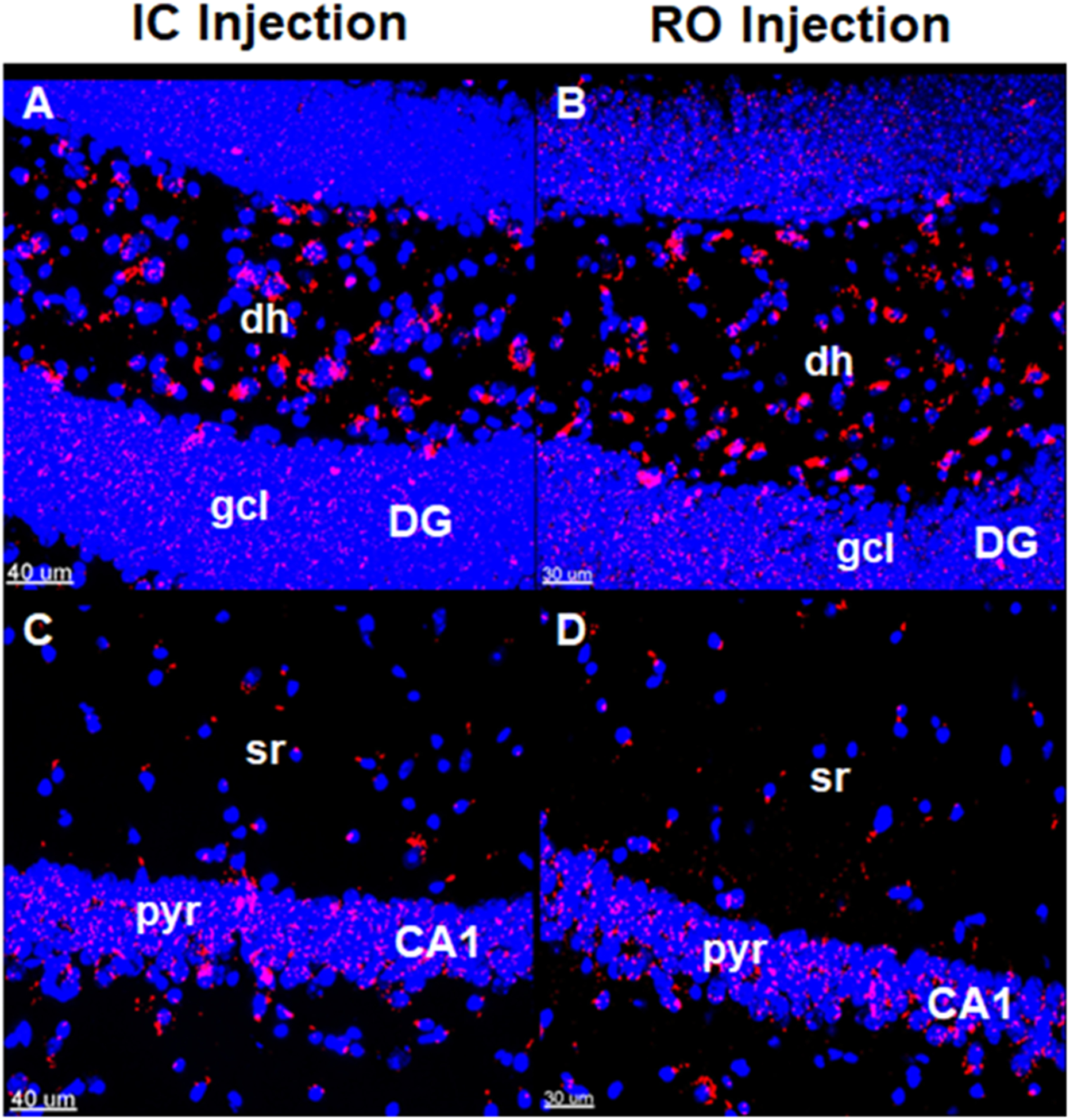

Tracking EV following IC transplantation and RO injection

Red fluorescent (PKH26) dye-labeled EV were used to determine whether EV migrate equally to various regions of the brain following distinct administration routes. In the IC transplanted mice, at 48 h post-injection, EV were found in the dentate gyrus (DG) and CA1 regions of the hippocampus adjacent to the transplantation sites (Fig. 2A,C). In the brain of the RO injected mice, fluorescent EV were also present in the DG and CA1 regions (Fig. 2B,D). We have shown previously that there were no obvious differences in the distribution of EV through hippocampus, SVZ and mPFC regions delivered by either route (32).

Figure 2. Stem cell-derived EV tracked to the host hippocampus following retro-orbital or intracranial injections.

Fluorescently labeled hNSC-derived EV were transplanted using stereotactic intracranial (IC) or retro-orbital (RO) injections. Brain tissue was fixed at 48 hours post-surgery and brain sections were imaged using confocal microscopy. Analysis suggests that IC injected EV (A, C) and RO injected EV (B, D) are similarly effective in targeting the dentate gyrus (DG) (A, B) and CA1 (C, D) regions of the hippocampus. Fluorescently labeled EV membranes, red; DAPI nuclear counterstain, blue. Scale bars = 30 μm (retro-orbital method), 40 μm (intracranial method). dh, dentate hilus; gcl, granule cell layer; sr, striatum radiatum; pyr, pyramidal cell layer

Stem cell-derived EV treatment reduces microglial activation in the irradiated hippocampus

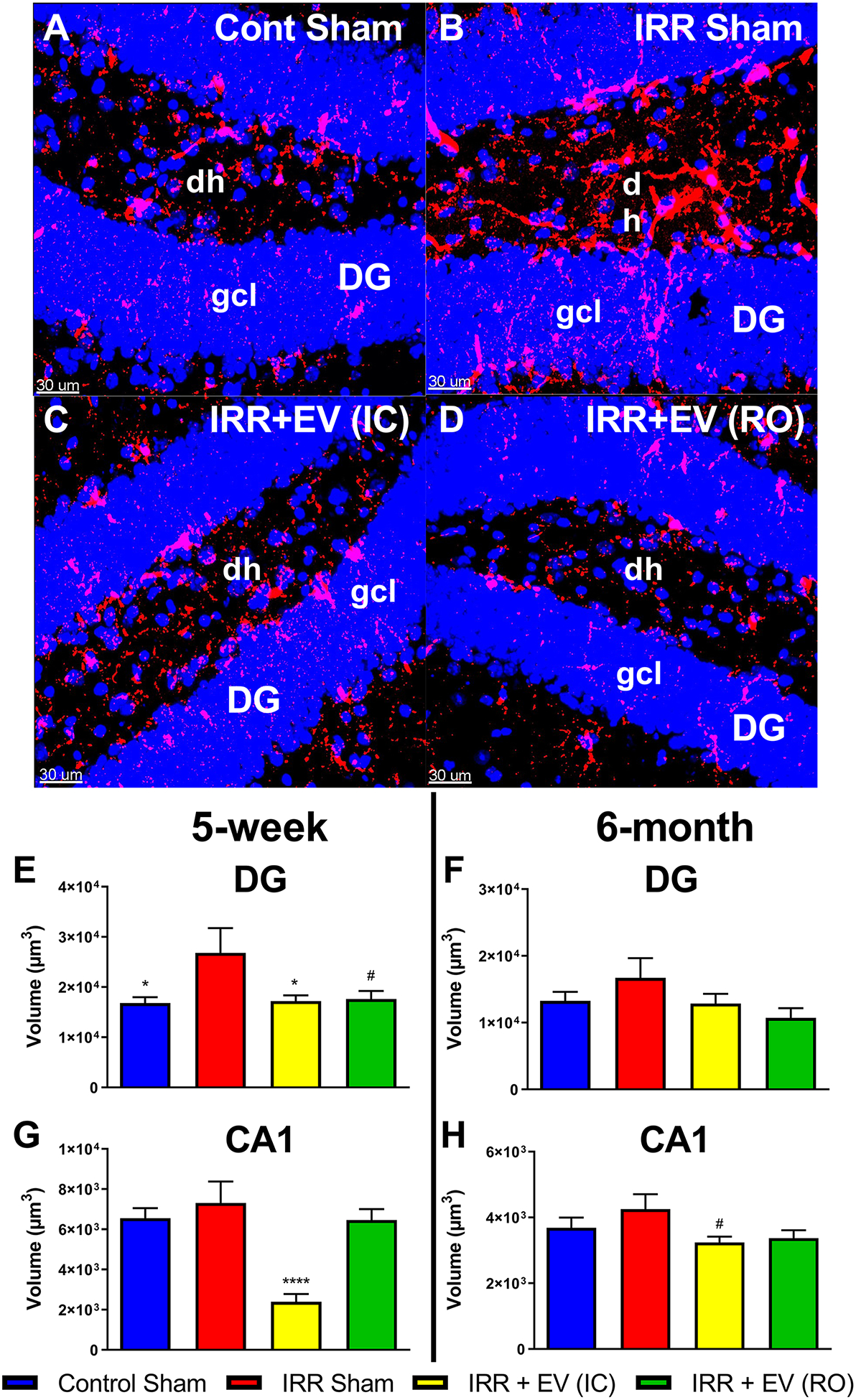

Following behavior testing CD68, a marker for activated microglia, was evaluated to assess the impact of EV treatments on neuroinflammation (Fig. 3). Representative images show the DG region of the hippocampus in brain sections from the five-week testing cohort (Fig. 3A–D). The number of CD68 positive cells for the IRR group, as quantified by total fluorescent volume per hippocampal section (mean = 2.68 × 104 μm3) was significantly greater than that of the control group (mean = 1.68 × 104 μm3) and the EV IC group (mean = 1.72 × 104 μm3), with P-values of 0.034 and 0.048, respectively (Fig. 3E). For the EV-treated RO group, there was a trend towards reduced CD68 levels (1.76 × 104 μm3; P = 0.061). The other hippocampal regions and time points showed similar trends for a higher volume of staining in the IRR group as compared to the control and EV-treated groups (Fig. 3F–H).

Figure 3. Stem cell-derived EV treatment reduces neuroinflammation in the hippocampus following irradiation.

Representative images of CD68+ activated microglia are shown from the dentate gyrus (DG) region of the hippocampus in all four groups for the five-week behavioral testing cohort. Relative to controls (A) the DG region of the hippocampus from irradiated mice show elevated levels of CD68 (B). EV treatment reduces CD68 levels in the irradiated brain (C and D; intracranial (IC) and retro-orbital (RO), respectively). Aggregate data from image processing with Imaris shows an increased volume of staining in the irradiated group compared to the control and EV-treated groups in the DG region in both the five-week (E) and six-month (G) cohorts. The same analysis showed similar trends in the CA1 region of the hippocampus in both the five-week (F) and six-month (H) cohorts. All data are presented as mean ± SEM (N = 4–6 mice per group). # P = 0.061, * P < 0.05, **** P < 0.0001 compared to the IRR group; P values are derived from ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (all other groups compared to IRR group). CD68, red; DAPI nuclear counterstain, blue. Scale bars = 30 μm. dh, dentate hilus; gcl, granule cell layer

Post-synaptic density protein 95 (PSD-95) is an excitatory-associated synaptic protein responsible for recruiting receptors and other proteins to the synaptic cleft. Changes in protein levels of PSD-95 have been shown to be altered following irradiation in a manner that may disrupt neurotransmission and contribute to cognitive dysfunction. However, evaluation of PSD-95 protein levels at both time points post-irradiation revealed no significant radiation effects (Supp. Fig. 2).

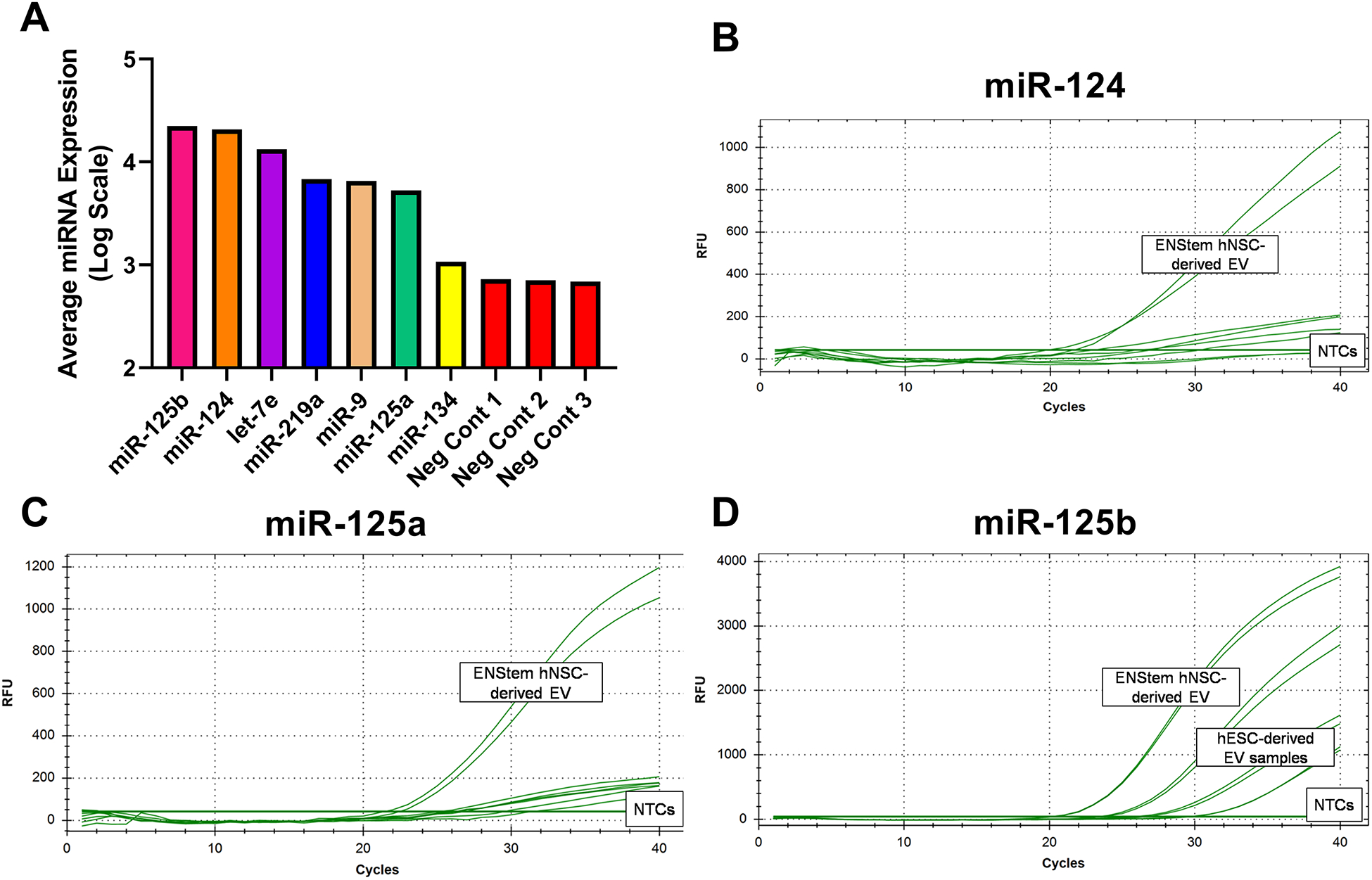

miRNA microarray analysis reveals miR-124 as potential therapeutic EV cargo

In order to investigate functional components of EV, total RNA was extracted from the hNSC-derived EV and analyzed using a targeted human miRNA array (Supp. Table 2). By cross-referencing the array data with the literature, candidate EV miRNAs implicated in learning, memory, neurogenesis, neurotransmission, synaptogenesis, and neuroinflammation were identified. These target miRNAs included miR-134–3p, miR-125b-5p, miR-124–3p, and miR-125a-5p (Fig. 4A). Of these candidates, all except miR-134–3p were confirmed to be present in EV RNA samples using TaqMan Advanced miRNA Assays (Fig. 4B–D), providing three candidate miRNA (miR-125b-5p, miR-124–3p, and miR-125a-5p) for follow up studies. Based on an abundance of literature (33–42) in support of a role for miR-124–3p in reducing neuroinflammation, miR-124–3p was chosen for further study.

Figure 4. hNSC-derived EV contain candidate miRNA that may mitigate RICD.

Total RNA extracted from therapeutic EV was analyzed by miRNA microarray. Select examples from array data (A) included four miRNAs with significant literature suggesting roles for them in synaptic function, dendrite outgrowth, and reduction in neuroinflammation. Of these four, three miRNAs (hsa-miR-124–3p, hsa-miR-125a-5p, and hsa-miR-125b-5p) could be validated using Taqman Advanced miRNA Assays (B, C, D).

Hippocampal miR-124 overexpression can mitigate RICD

To determine whether hsa-miR-124–3p (miR-124) was sufficient to mitigate RICD in wild type mice, the miR-124 sequence was cloned into an overexpression AAV vector and the construct was packaged into AAV9 particles (SignaGen; Fig. 5A). As with EV treatments, wild type male mice were cranially irradiated with the same 9 Gy dose of γ-rays and received stereotaxic injections 48 hours later with the miR-124 AAV9 construct or a scrambled control. The miR-124 treated mice underwent behavioral testing at five weeks post-irradiation (Fig. 5B–D). The NPR test revealed a significant overall group effect in DI between groups (F(3,38) = 2.91; P = 0.0468). The 9 Gy + miR-Scr group mean DI was 4.87%, which was lower than the mean DI of the 0 Gy + miR-124 (mean = 21.5%; P = 0.055) and 9 Gy + miR-124 (mean = 16.2%; P = 0.265) groups. In this instance only a small difference in mean DI was observed between the 9 Gy miR-Scr group and the 0 Gy + miR-Scr group (mean = 5.23%) (Fig. 5B). Similarly, a significant group effect was found for the NOR test (F(3,38) = 3.51; P = 0.0244). The 9 Gy + miR-Scr group had a mean DI of 3.03%, whereas the 9 Gy + miR-124 group (mean = 28.8%; P = 0.0072) had significantly higher mean DI values. The DI values for the 0 Gy groups were also higher, though not significantly so (0 Gy + miR-Scr: mean = 16.0%; P = 0.244; 0 Gy miR-124: mean = 17.6%; P = 0.181) (Fig. 5C). The group effect in the case of the TO test did not reach significance (F(3,30) = 2.73; P = 0.0615). In a result similar to the NOR test, the DI for the 9 Gy + miR-Scr group (mean = −1.69%) was observed to be significantly lower than the 9 Gy + miR-124 (mean = 29.4%; P = 0.0474) group and lower than both 0 Gy groups (0 Gy + miR-Scr: mean = 18.6%; P = 0.215; 0 Gy + miR-124: mean = 25.9%; P = 0.0724) (Fig. 5D). Total explorations times were found to be significantly different between the 0 Gy + miR-Scr and 0 Gy + miR-124 groups for the NOR test as well as the 0 Gy + miR-124 and 9 Gy + miR-Scr groups for the TO test. The rest of the total exploration times were not found to differ across the experimental cohorts for these tests, suggesting that treatment-induced locomotor changes did not confound our findings (Supp. Table 3).

Figure 5. miR-124 overexpression in vivo shows functional mitigation of RICD.

To determine whether miR-124 was sufficient to mitigate RICD in wild type mice, the miRNA sequence was cloned into a vector designed to overexpress miR-124 and the construct packaged into AAV9 particles. The vector map (A, designed by Signagen) shows that miR-124 expression is driven by the U6 promoter and eGFP expression is driven by the CMV enhancer and promoter. These transgenes are flanked by AAV2 inverted terminal repeats (ITR) for efficient propagation of the AAV genome. Mice received stereotaxic IC injections of AAV9 particles containing this vector two days post-irradiation. At five weeks post-irradiation, animals were administered spontaneous exploration tasks in the following order: NPR (B), NOR (C), and TO (D). Tendency to explore novelty (novel place or object) was calculated using the discrimination index [(novel location exploration time/total exploration time) – (familiar location exploration time/total exploration time)] × 100. All data are presented as mean ± SEM (N=10–11 mice per group). # P = 0.0724, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 compared to the IRR group. P values are derived from one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons (all other groups compared to the 9 Gy + miR-Scr group).

The spread of AAV9 particles and expression of the GFP reporter gene was confirmed experimentally (Fig. 6). Expression of the transgene construct was not limited to the area proximal to the injection sites in the hippocampus, but rather spread to the cortex (Fig. 6A) and corpus callosum (Fig. 6B), as well. Based on morphology, GFP expression was detected in both neuronal and glial cell types (Fig. 6C–D).

Figure 6. Reporter gene confirmation and tracking of AAV9-miR-124 in vivo.

The AAV9 vector designed to express either intact or scrambled miR-124 carried the eGFP reporter gene to enable construct visualization in vivo. After completion of behavior (8–10 weeks post-surgery) coronal brain sections were imaged for the presence of eGFP signal. Widespread expression of vector (green) was found in the cortex (A, layers IV, V and VI), corpus callosum (B, CC) and hippocampus (B, CA1; pyr, pyramidal layer; sr, stratum radiatum). Vector expression was evident in the cells resembling neuronal (C, arrows) and glial morphologies (D, arrows). Scale bars: 100 μm, A-B and 20 μm, C-D.

miR-124 overexpression reduced microglial activation

Similar to the EV-treated cohort, CD68 immunoreactivity was evaluated following behavioral testing to assess the impact of miR-124 overexpression on neuroinflammation (Fig. 7). Representative images show the impact of miR-124 overexpression on both the total number of microglia assessed using the Iba1 marker (Fig. 7A–B) and the amount of microglial activation indicated by the CD68 marker (Fig. 7C–D) in the irradiated hippocampus. Aggregate data from image processing using Imaris shows a decrease in Iba1+ cells in the hippocampus of in the 9 Gy + miR-Scr group compared to all other groups (Fig. 7E). The volume of CD68 staining was measured for both DG and CA1 regions of the hippocampus, combined, and adjusted for the average number of Iba1+ hippocampal microglia in each group (Fig. 7F). A significant overall group effect was observed for the difference in staining between groups (F(3,82) = 10.7; P < 0.0001). The adjusted CD68 immunoreactivity value for the 9 Gy + miR-Scr group (mean = 239) was significantly greater than that of the 0 Gy + miR-Scr group (mean = 152; P = 0.0045) and the miR-124-overexpressing groups (0 Gy + miR-124: mean = 140; P = 0.0009; 9 Gy + miR-124: mean = 91.1; P < 0.0001). In sum, data showed that miR-124 overexpression resulted in functionally equivalent effects as EV treatments, where reductions in neuroinflammation coincided with an amelioration of RICD.

Figure 7. miR-124 overexpression in vivo following cranial irradiation reduces neuroinflammation in the hippocampus.

Representative images of Iba1+ microglia and CD68+ activated microglia immunohistochemistry are shown from the hippocampus and dentate gyrus (DG), respectively, for the 9 Gy miR-Scr and the 9 Gy miR-124 groups of the miR-124 cohort. Relative to miR-124-overexpressing group (B), the mice in the 9 Gy miR-Scr group show decreased numbers of Iba1+ cells in hippocampal subfields (A). miR-124 overexpression (D) resulted in a relative decrease in the CD68+ immunoreactivity in the DG region when compared to the 9 Gy miR-Scr group (C). Aggregate data from image processing with Imaris shows an increased Iba1-adjusted (E) volume of CD68 immunoreactivity in the irradiated group compared to the control and miR-124 overexpressing groups in the hippocampus (F). All data are presented as mean ± SEM (N = 4 mice per group). ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001 **** P < 0.0001 compared to the IRR group; P values are derived from ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. Iba1, red; CD68, red; DAPI nuclear counterstain, blue. Scale bars = 150 μm (A, B) and 40 μm (C, D). dh, dentate hilus; gcl, granule cell layer.

Discussion

Ionizing radiation has been and will likely remain a powerful tool in the fight against cancer. The major limitation to the efficacy of RT is the resultant dose-dependent normal tissue toxicity. Multiple dose delivery strategies have emerged in an attempt to mitigate downstream damage (7–10,14,15) or avoid this complication using either precise tumor targeting (43–45) or ultra-high dose rate (46–48). While hNSC-derived EV have been used to effectively mitigate normal tissue toxicity in nude rats (14,15), current findings are the first example of using EV for this purpose in immunocompetent animals. Moreover, these data demonstrate the efficacy of a mildly invasive and translationally feasible route of administration. While replicating past stem cell transplantation studies using EV therapy in an athymic nude rat model was a logical first step, the real advantages of this strategy were borne out in the current study.

Present findings show for the first time, that an intravenous (retro-orbital) injection of hNSC-derived EV to cranially irradiated wild type mice was able to significantly mitigate RICD and accompanying neuroinflammation. The beneficial effects of the EV therapy were consistent for both the known (intrahippocampal, (14)) and the novel (retro-orbital) methods of delivery as well as at the short (five weeks) and long (six months) post-irradiation times. Further, we were able to identify a potential mechanism of action for EV therapy. We hypothesized and then tested the ability of a specific miRNA, miR-124, to mitigate RICD and neuroinflammation in vivo. Importantly, overexpression of this specific miRNA, just one known component of the bioactive EV cargo, was sufficient to impart significant neuroprotective phenotypes.

Cognitive testing results from a battery of spontaneous exploration tasks demonstrated conclusively the onset and persistence of RICD, specifically affecting the hippocampus, perirhinal cortex, and mPFC regions of the brain, serious complications mitigated by EV treatment. Interestingly, just a single dose of EV (or in vivo overexpression of miR-124) administered 48 hours post-irradiation was to be efficacious in mitigating RICD. While repeated treatments were not tested, this translationally feasible approach facilitates implementation of serial administration schedules that could provide further neuroprotective benefits at the cognitive, cellular and molecular levels especially at more protracted times. While multiple systemic injections of EV would be relatively simple and straightforward, the behavioral data at both five weeks and six months post-irradiation suggest that a single dose is sufficient to maintain long term intact hippocampal, perirhinal cortex, and mPFC function.

Collectively, data showed the hNSC-derived EV were equally able to co-localize to the brain via local (IC) or systemic (RO) routes of administration. Further, these results confirmed prior studies suggesting that EV could cross the BBB and interact with specific cellular subtypes in the brain (24,25). Intracranial tracking of fluorescent EV revealed no obvious differences in distribution, which was widespread throughout the hippocampal subfields (Fig. 2). Coalescence of EV surrounding target cells was revealed by the presence of larger fluorescent aggregates 48 hours after injection, likely representing multiple fusion events between EV of unknown functional significance. Additional studies are required to determine optimal dosing and whether molecular modifications could be undertaken to target EV to specific cell types for select phenotypic modulation.

While multiple mechanisms are likely responsible for the beneficial effects of EV treatments on the irradiated brain, their ability to modulate inflammatory processes provides a plausible explanation. Neuroinflammation has been shown to play a significant role in progressive neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease, and multiple sclerosis (49). Moreover, our group has previously shown an increase in activated microglia following irradiation that was abrogated by EV treatment (14,15). Given the robust attenuation of microglial activation by EV treatments, the identification of miR-124 as an EV cargo component, and the wealth of literature on miR-124 reducing neuroinflammation in similar models (33,40,42), further studies were then focused on evaluating the functional relevance of miR-124.

AAV9 constructs designed to drive the overexpression of miR-124 were then injected directly into the mouse hippocampus to critically test whether this could resolve (in part), RICD and associated normal tissue pathology in the brain. Intrahippocampal injections were selected for these proof of principle studies to target miR124 overexpression to a select region of the brain and to avoid systemic dilution of the viral particles. Tracking of eGFP reporter expression (Fig. 6) indicated that AAV9 particles were able to spread from the hippocampal injection sites and drive transgene expression in neurons and glial cells. Data showed that miR-124 overexpression was able to mitigate RICD in a similar, albeit less efficacious fashion than EV treatments. Many explanations could account for this, as it is extremely likely that the neuroprotective benefits of EV involve more than one miRNA or other EV cargo. Another reason could be related to the amount of time it takes to reach maximal expression of the AAV construct, generally achieved by 2 weeks (50). Thus, optimal expression, bioavailability and proximity of EV treatment to irradiation are all factors that could clearly impact the therapeutic benefits of miR-124. While further studies to inhibit miR-124 via antagomirs or miR-sponges may provide further mechanistic insight, miR-124 is ubiquitous in CNS tissues (51), pointing to the potential confounding off-target effects of such approaches.

This study represents an exciting development in the field of normal tissue protection following radiation injury. While we focused on miR-124 overexpression, hNSC-derived EV contained other candidate molecular cargo. Inhibition of miR-125a has been shown to decrease levels of PSD-95 in dendrites (52), and miR-125b has been shown to regulate synaptic structure and function (53). Furthermore, combinations of miRNAs could be more effective than individual ones, such that a “miR cocktail” could be loaded into cell culture-derived EV, liposomes (54), or artificially engineered EV (55,56). Amelioration of RICD might also be achieved from EV derived from other normal brain cell types such as mature neurons, astrocytes, and microglia, or even mesenchymal stem cell-derived EV that have been shown to reduce inflammation in other models (57,58). Systemic efficacy could also be optimized by engineering various EV types to contain a transmembrane protein and/or moiety for targeting purposes (42). As with the previous studies (7–10,14,15,31,48) this study was performed using tumor-free animals to study the biological mechanisms and physiological effect in the absence of confounding disease. Before any clinical application involving RT used in the context of cancer treatment, EV-tumor cell interactions would have to be investigated for lack of tumor promotion and changes to treatment efficacy. Further, a single dose of WBRT was used in present studies to follow up on the significant body of work from our lab implementing such a dosing scheme. While previous studies (59,60) have shown that fractionated irradiation causes RICD, follow up studies aimed at determining how EV might mitigate RICD after dose fractionation and in female mice are clearly warranted.

Over the years our group, among others, have not included grafted controls (either stem cells or extracellular vesicles) since such transplantation procedures used to treat a variety of pathologies in different rodent models were not found to functionally affect the intact normal brain (14,18,20,42,61). Importantly, past work from us using stem cells (62) and from others using EV (63,64), in which grafted controls were included, found that every single functional or molecular endpoint was statistically indistinguishable between the control, control+stem cell or control+EV groups. Further rationale for excluding controls treated with EV alone, is that inclusion of such cohorts is clinically irrelevant.

Here we highlight the benefits of EV treatments, which have certain advantages over stem cell-based approaches for resolving normal tissue complications (11–13). The ability to impart neuroprotective benefits to the irradiated brain without the need for invasive surgical procedures, immune suppression or risk of teratoma formation bode well for future clinical translation. Moreover, we were able to identify some of the beneficial bioactive miRNA cargo in EV, that suggests similar approaches and/or combinations of miRNA will hold additional benefits. Any approach capable of minimizing dose limiting toxicities to a target tissue or organ is poised to provide opportunities for dose escalation and enhanced radiocurability for the eventual benefit of those afflicted with cancer worldwide.

Supplementary Material

Significance.

Radiation-induced neurocognitive decrements in immune-competent mice can be resolved by systemic delivery of human neural stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles involving a mechanism dependent on expression of miR-124.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Erich Giedzinski, Maria Angulo, Lauren Apodaca, Ning Ru, Liping Yu, and Sana Jayaswal for expert technical assistance. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Michael Story and his group at UTSW for providing the microarray data. The authors also thank UC Irvine Professors Drs. Kim Green and Matthew Blurton-Jones for expert advice concerning the miR-124 overexpression project. Special thanks to Darryl Leja of the NHGRI for use of his illustration of the RO injection used in Figure 1. This work was supported by NINDS Grant R01 NS074388 (CLL), the UCI Research Seed Funding Program (JEB), and California Institute for Regenerative Medicine DISC1-10079 (JEB)

Footnotes

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Taphoorn MJ, Janzer RC, et al. Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol 2009;10:459–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee YW, Cho HJ, Lee WH, Sonntag WE. Whole brain radiation-induced cognitive impairment: pathophysiological mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Biomol Ther (Seoul) 2012;20:357–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meyers CA. Neurocognitive dysfunction in cancer patients. Oncology (Williston Park) 2000;14:75–9; discussion 9, 81–2, 5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roman DD, Sperduto PW. Neuropsychological effects of cranial radiation: current knowledge and future directions. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1995;31:983–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abayomi OK. Pathogenesis of irradiation-induced cognitive dysfunction. Acta Oncol 1996;35:659–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson VA, Godber T, Smibert E, Weiskop S, Ekert H. Cognitive and academic outcome following cranial irradiation and chemotherapy in children: a longitudinal study. Br J Cancer 2000;82:255–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Acharya MM, Christie LA, Lan ML, Giedzinski E, Fike JR, Rosi S, et al. Human neural stem cell transplantation ameliorates radiation-induced cognitive dysfunction. Cancer Res 2011;71:4834–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Acharya MM, Martirosian V, Christie LA, Limoli CL. Long-term cognitive effects of human stem cell transplantation in the irradiated brain. Int J Radiat Biol 2014;90:816–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Acharya MM, Martirosian V, Christie LA, Riparip L, Strnadel J, Parihar VK, et al. Defining the optimal window for cranial transplantation of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cells to ameliorate radiation-induced cognitive impairment. Stem Cells Transl Med 2015;4:74–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Acharya MM, Rosi S, Jopson T, Limoli CL. Human neural stem cell transplantation provides long-term restoration of neuronal plasticity in the irradiated hippocampus. Cell Transplant 2015;24:691–702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bradley JA, Bolton EM, Pedersen RA. Stem cell medicine encounters the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol 2002;2:859–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blum B, Benvenisty N. The tumorigenicity of human embryonic stem cells. Adv Cancer Res 2008;100:133–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gutierrez-Aranda I, Ramos-Mejia V, Bueno C, Munoz-Lopez M, Real PJ, Macia A, et al. Human induced pluripotent stem cells develop teratoma more efficiently and faster than human embryonic stem cells regardless the site of injection. Stem Cells 2010;28:1568–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baulch JE, Acharya MM, Allen BD, Ru N, Chmielewski NN, Martirosian V, et al. Cranial grafting of stem cell-derived microvesicles improves cognition and reduces neuropathology in the irradiated brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016;113:4836–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith SM, Giedzinski E, Angulo MC, Lui T, Lu C, Park AL, et al. Functional equivalence of stem cell and stem cell-derived extracellular vesicle transplantation to repair the irradiated brain. Stem Cells Transl Med 2020;9:93–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xin H, Li Y, Buller B, Katakowski M, Zhang Y, Wang X, et al. Exosome-mediated transfer of miR-133b from multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells to neural cells contributes to neurite outgrowth. Stem Cells 2012;30:1556–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xin H, Li Y, Cui Y, Yang JJ, Zhang ZG, Chopp M. Systemic administration of exosomes released from mesenchymal stromal cells promote functional recovery and neurovascular plasticity after stroke in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2013;33:1711–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xin H, Li Y, Liu Z, Wang X, Shang X, Cui Y, et al. MiR-133b promotes neural plasticity and functional recovery after treatment of stroke with multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells in rats via transfer of exosome-enriched extracellular particles. Stem Cells 2013;31:2737–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y, Chopp M, Meng Y, Katakowski M, Xin H, Mahmood A, et al. Effect of exosomes derived from multipluripotent mesenchymal stromal cells on functional recovery and neurovascular plasticity in rats after traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg 2015;122:856–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Y, Chopp M, Zhang ZG, Katakowski M, Xin H, Qu C, et al. Systemic administration of cell-free exosomes generated by human bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells cultured under 2D and 3D conditions improves functional recovery in rats after traumatic brain injury. Neurochem Int 2017;111:69–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gangoda L, Boukouris S, Liem M, Kalra H, Mathivanan S. Extracellular vesicles including exosomes are mediators of signal transduction: are they protective or pathogenic? Proteomics 2015;15:260–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cocucci E, Meldolesi J. Ectosomes and exosomes: shedding the confusion between extracellular vesicles. Trends Cell Biol 2015;25:364–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang J, Li S, Li L, Li M, Guo C, Yao J, et al. Exosome and exosomal microRNA: trafficking, sorting, and function. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 2015;13:17–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalani A, Tyagi A, Tyagi N. Exosomes: mediators of neurodegeneration, neuroprotection and therapeutics. Mol Neurobiol 2014;49:590–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alvarez-Erviti L, Seow Y, Yin H, Betts C, Lakhal S, Wood MJ. Delivery of siRNA to the mouse brain by systemic injection of targeted exosomes. Nat Biotechnol 2011;29:341–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu X, Badawi M, Pomeroy S, Sutaria DS, Xie Z, Baek A, et al. Comprehensive toxicity and immunogenicity studies reveal minimal effects in mice following sustained dosing of extracellular vesicles derived from HEK293T cells. J Extracell Vesicles 2017;6:1324730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Acharya MM, Lan ML, Kan VH, Patel NH, Giedzinski E, Tseng BP, et al. Consequences of ionizing radiation-induced damage in human neural stem cells. Free Radic Biol Med 2010;49:1846–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thery C, Amigorena S, Raposo G, Clayton A. Isolation and characterization of exosomes from cell culture supernatants and biological fluids. Curr Protoc Cell Biol 2006;Chapter 3:Unit 3 22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Acharya MM, Baulch JE, Klein PM, Baddour AAD, Apodaca LA, Kramar EA, et al. New Concerns for Neurocognitive Function during Deep Space Exposures to Chronic, Low Dose-Rate, Neutron Radiation. eNeuro 2019;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang CH, Knapska E, Orsini CA, Rabinak CA, Zimmerman JM, Maren S. Fear extinction in rodents. Curr Protoc Neurosci 2009;Chapter 8:Unit8 23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Acharya MM, Green KN, Allen BD, Najafi AR, Syage A, Minasyan H, et al. Elimination of microglia improves cognitive function following cranial irradiation. Sci Rep 2016;6:31545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ioannides P, Giedzinski E, Limoli CL. Evaluating different routes of extracellular vesicle administration for cranial therapies. J Cancer Metastasis Treat 2020;6:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu A, Zhang T, Duan H, Pan Y, Zhang X, Yang G, et al. MiR-124 contributes to M2 polarization of microglia and confers brain inflammatory protection via the C/EBP-alpha pathway in intracerebral hemorrhage. Immunol Lett 2017;182:1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang S, Ge X, Yu J, Han Z, Yin Z, Li Y, et al. Increased miR-124–3p in microglial exosomes following traumatic brain injury inhibits neuronal inflammation and contributes to neurite outgrowth via their transfer into neurons. FASEB J 2018;32:512–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun Y, Li Q, Gui H, Xu DP, Yang YL, Su DF, et al. MicroRNA-124 mediates the cholinergic anti-inflammatory action through inhibiting the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Cell Res 2013;23:1270–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yao L, Ye Y, Mao H, Lu F, He X, Lu G, et al. MicroRNA-124 regulates the expression of MEKK3 in the inflammatory pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. J Neuroinflammation 2018;15:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Geng L, Liu W, Chen Y. miR-124–3p attenuates MPP(+)-induced neuronal injury by targeting STAT3 in SH-SY5Y cells. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2017;242:1757–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Periyasamy P, Thangaraj A, Guo ML, Hu G, Callen S, Buch S. Epigenetic Promoter DNA Methylation of miR-124 Promotes HIV-1 Tat-Mediated Microglial Activation via MECP2-STAT3 Axis. J Neurosci 2018;38:5367–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Periyasamy P, Liao K, Kook YH, Niu F, Callen SE, Guo ML, et al. Cocaine-Mediated Downregulation of miR-124 Activates Microglia by Targeting KLF4 and TLR4 Signaling. Mol Neurobiol 2018;55:3196–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang Y, Ye Y, Kong C, Su X, Zhang X, Bai W, et al. MiR-124 Enriched Exosomes Promoted the M2 Polarization of Microglia and Enhanced Hippocampus Neurogenesis After Traumatic Brain Injury by Inhibiting TLR4 Pathway. Neurochem Res 2019;44:811–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ponomarev ED, Veremeyko T, Barteneva N, Krichevsky AM, Weiner HL. MicroRNA-124 promotes microglia quiescence and suppresses EAE by deactivating macrophages via the C/EBP-alpha-PU.1 pathway. Nat Med 2011;17:64–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang J, Zhang X, Chen X, Wang L, Yang G. Exosome Mediated Delivery of miR-124 Promotes Neurogenesis after Ischemia. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2017;7:278–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nwokedi EC, DiBiase SJ, Jabbour S, Herman J, Amin P, Chin LS. Gamma knife stereotactic radiosurgery for patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Neurosurgery 2002;50:41–6; discussion 6–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hsieh PC, Chandler JP, Bhangoo S, Panagiotopoulos K, Kalapurakal JA, Marymont MH, et al. Adjuvant gamma knife stereotactic radiosurgery at the time of tumor progression potentially improves survival for patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Neurosurgery 2005;57:684–92; discussion −92 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crowley RW, Pouratian N, Sheehan JP. Gamma knife surgery for glioblastoma multiforme. Neurosurg Focus 2006;20:E17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Favaudon V, Caplier L, Monceau V, Pouzoulet F, Sayarath M, Fouillade C, et al. Ultrahigh dose-rate FLASH irradiation increases the differential response between normal and tumor tissue in mice. Sci Transl Med 2014;6:245ra93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Montay-Gruel P, Petersson K, Jaccard M, Boivin G, Germond JF, Petit B, et al. Irradiation in a flash: Unique sparing of memory in mice after whole brain irradiation with dose rates above 100Gy/s. Radiother Oncol 2017;124:365–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Montay-Gruel P, Acharya MM, Petersson K, Alikhani L, Yakkala C, Allen BD, et al. Long-term neurocognitive benefits of FLASH radiotherapy driven by reduced reactive oxygen species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019;116:10943–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kempuraj D, Thangavel R, Natteru PA, Selvakumar GP, Saeed D, Zahoor H, et al. Neuroinflammation Induces Neurodegeneration. J Neurol Neurosurg Spine 2016;1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Klein RL, Dayton RD, Tatom JB, Diaczynsky CG, Salvatore MF. Tau expression levels from various adeno-associated virus vector serotypes produce graded neurodegenerative disease states. Eur J Neurosci 2008;27:1615–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lagos-Quintana M, Rauhut R, Yalcin A, Meyer J, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T. Identification of tissue-specific microRNAs from mouse. Curr Biol 2002;12:735–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Muddashetty RS, Nalavadi VC, Gross C, Yao X, Xing L, Laur O, et al. Reversible inhibition of PSD-95 mRNA translation by miR-125a, FMRP phosphorylation, and mGluR signaling. Mol Cell 2011;42:673–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Edbauer D, Neilson JR, Foster KA, Wang CF, Seeburg DP, Batterton MN, et al. Regulation of synaptic structure and function by FMRP-associated microRNAs miR-125b and miR-132. Neuron 2010;65:373–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Malam Y, Loizidou M, Seifalian AM. Liposomes and nanoparticles: nanosized vehicles for drug delivery in cancer. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2009;30:592–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Antimisiaris SG, Mourtas S, Marazioti A. Exosomes and Exosome-Inspired Vesicles for Targeted Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2018;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang J, Li W, Lu Z, Zhang L, Hu Y, Li Q, et al. The use of RGD-engineered exosomes for enhanced targeting ability and synergistic therapy toward angiogenesis. Nanoscale 2017;9:15598–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Timmers L, Lim SK, Arslan F, Armstrong JS, Hoefer IE, Doevendans PA, et al. Reduction of myocardial infarct size by human mesenchymal stem cell conditioned medium. Stem Cell Res 2007;1:129–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee RH, Pulin AA, Seo MJ, Kota DJ, Ylostalo J, Larson BL, et al. Intravenous hMSCs improve myocardial infarction in mice because cells embolized in lung are activated to secrete the anti-inflammatory protein TSG-6. Cell Stem Cell 2009;5:54–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Allen BD, Acharya MM, Lu C, Giedzinski E, Chmielewski NN, Quach D, et al. Remediation of Radiation-Induced Cognitive Dysfunction through Oral Administration of the Neuroprotective Compound NSI-189. Radiat Res 2018;189:345–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dey D, Parihar VK, Szabo GG, Klein PM, Tran J, Moayyad J, et al. Neurological Impairments in Mice Subjected to Irradiation and Chemotherapy. Radiat Res 2020;193:407–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Long Q, Upadhya D, Hattiangady B, Kim DK, An SY, Shuai B, et al. Intranasal MSC-derived A1-exosomes ease inflammation, and prevent abnormal neurogenesis and memory dysfunction after status epilepticus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017;114:E3536–E45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Acharya MM, Christie LA, Lan ML, Donovan PJ, Cotman CW, Fike JR, et al. Rescue of radiation-induced cognitive impairment through cranial transplantation of human embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106:19150–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kalani A, Chaturvedi P, Kamat PK, Maldonado C, Bauer P, Joshua IG, et al. Curcumin-loaded embryonic stem cell exosomes restored neurovascular unit following ischemia-reperfusion injury. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2016;79:360–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Drommelschmidt K, Serdar M, Bendix I, Herz J, Bertling F, Prager S, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles ameliorate inflammation-induced preterm brain injury. Brain Behav Immun 2017;60:220–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.