Abstract

Background & Aims

Expert consensus mandates retesting for eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection after treatment, but it is not clear how many patients are actually retested. We evaluated factors associated with retesting for H pylori in a large, nationwide cohort.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study of patients with H pylori infection (detected by urea breath test, stool antigen, or pathology) who were prescribed an eradication regimen from January 1, 1994 through December 31, 2018 within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). We collected data on demographic features, smoking history, socioeconomic status, facility poverty level and academic status, and provider specialties and professions. The primary outcome was retesting for eradication. Statistical analyses included mixed-effects logistic regression.

Results

Of 27,185 patients prescribed an H pylori eradication regimen, 6486 patients (23.9%) were retested. Among 7623 patients for whom we could identify the provider who ordered the test, 2663 patients (34.9%) received the order from a gastroenterological provider. Female sex (odds ratio, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.08–1.38; P=.002) and history of smoking (odds ratio, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.15–1.33; P<.001) were patient factors associated with retesting. There was an interaction between method of initial diagnosis of H pylori infection and provider who ordered the initial test (P<.001). There was significant variation in rates of retesting among VHA facilities (P<.001).

Conclusions

In an analysis of data from a VHA cohort of patients with H pylori infection, we found low rates of retesting after eradication treatment. There is significant variation in rates of retesting among VHA facilities. H pylori testing is ordered by non-gastroenterology specialists two-thirds of the time. Confirming eradication of H pylori is mandatory and widespread quality assurance protocols are needed.

Keywords: antibiotic, response to therapy, resistance, risk factor

INTRODUCTION

Infection with Helicobacter pylori (HP) is associated with multiple gastrointestinal diseases, including malignancy.1–3 It is a widespread global infection, acquired in childhood, and is estimated to infect half of the world’s population.4–6 Due to its association with gastric adenocarcinoma, it was labeled a class 1 carcinogen by the World Health Organization.2,7,8

Guidelines suggest initial testing for HPin the setting of peptic ulcer disease, MALT lymphoma, gastric adenocarcinoma, and dyspepsia.9 Diagnosis can be made by stool antigen, urea breath test, or gastric biopsy. Although endoscopies are almost universally performed by gastroenterologists, they can be ordered by non-gastroenterology providers, while urea breath tests are performed by gastroenterology nurses or technicians, and stool antigen tests can be performed at almost all commercial laboratories.10,11 All patients who are found to have the infection should be offered treatment per expert consensus.12 Thereafter, subsequent retesting to confirm eradication is mandatory.9,12 This three-step recommendation to test, treat, and retest is important given the high rates of treatment failure, estimated at 20–30%, due to poor patient compliance of a multi-drug regimen and rising rates of antibiotic resistance.1,3,13 This three-step process is in stark contrast to the 1990’s, when routine retesting for HPwas a source of contention, with the invasive nature, cost, and time required for retesting leading to differing opinions on whether it was necessary.14,15

Yet rates of and factors associated with retesting have been poorly studied. Studies have generally been limited to single centers and small numbers of patients, yet they suggest inadequate retesting rates, even among gastroenterologists.16–19 Here, we sought to evaluate patient and facility factors associated with appropriate retesting in a large, nationwide cohort of patients with HP, and to evaluate facility variability in retesting rates.

METHODS

This retrospective cohort study was conducted within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), which includes data from the electronic medical record of all VHA facilities from 10/01/1999 onwards. We identified patients with HPby diagnostic testing: urea breath test, stool antigen, and/or gastric biopsy. Filtering in the CDW allowed identification of positive stool antigens and urea breath tests. Identification of HPon endoscopic pathology was performed using natural language processing on pathologic reports (previously validated).20,21 We included those patients prescribed an eradication regimen within the VHA. We only included patients prescribed an eradication regimen in order to minimize the possibility that the first HP test within the VHA was actually the follow-up retest. Unique identifiers assured no duplications. This analysis was performed on the largest cohort of patients in the US with HP, which has been used in prior publications.20,21

Study Outcome

The primary outcome was binary, whether or not a patient underwent retesting. Retesting was considered present if a patient underwent repeat HP testing by urea breath testing, stool antigen, or gastric biopsy.

Statistical Analysis

We fit mixed-effects logistic regression models to evaluate factors associated with retesting, and facility variability in retesting for all analyses. We used mixed effects models with facility-level random intercepts, rather than standard logistic regression models, to account for clustering of patients within facilities, variable patterns of retesting, and heterogeneity in access to specialists, procedures, and testing across facilities. We chose to do this as individual patients are clustered within facilities, which could lead to correlated outcomes of patients within those clusters. In contrast to a traditional fixed effect that has levels that are of primary interest and would be used again if the study were to be repeated, random effects can be viewed as selecting from a much larger set of levels.22 In the case of this study, facilities serve as the random effects, because one can view the centers in this study as being selected from the set of all VHA facilities. We used marginal standardization to predict the prevalence of retesting by facility with respect to the distribution of other covariates.

We evaluated the following patient-specific covariates: age, gender, race, ethnicity, history of ever smoking23, and zip code-level poverty at HPdiagnosis (categorized based on percentage of people within a zip code below the federal poverty line using 2010 census data). Facility-specific covariates included whether the facility is academic and percent of low socioeconomic veterans served.24 Test-specific covariates included the method of initial HP diagnosis and the specialty (gastroenterology or non-gastroenterology) and provider status (physician or non-physician). We used stopcodes and provider class to identify location of testing (gastroenterological setting or otherwise) and provider type (gastroenterological or otherwise, physician or otherwise).

Stata/IC 15.1 (College Station, TX) was used to perform backward selection, with inclusion of all clinically significant odds ratios (ORs), P<0.10. The Institutional Review Boards of the Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center and the University of Pennsylvania approved this study.

RESULTS

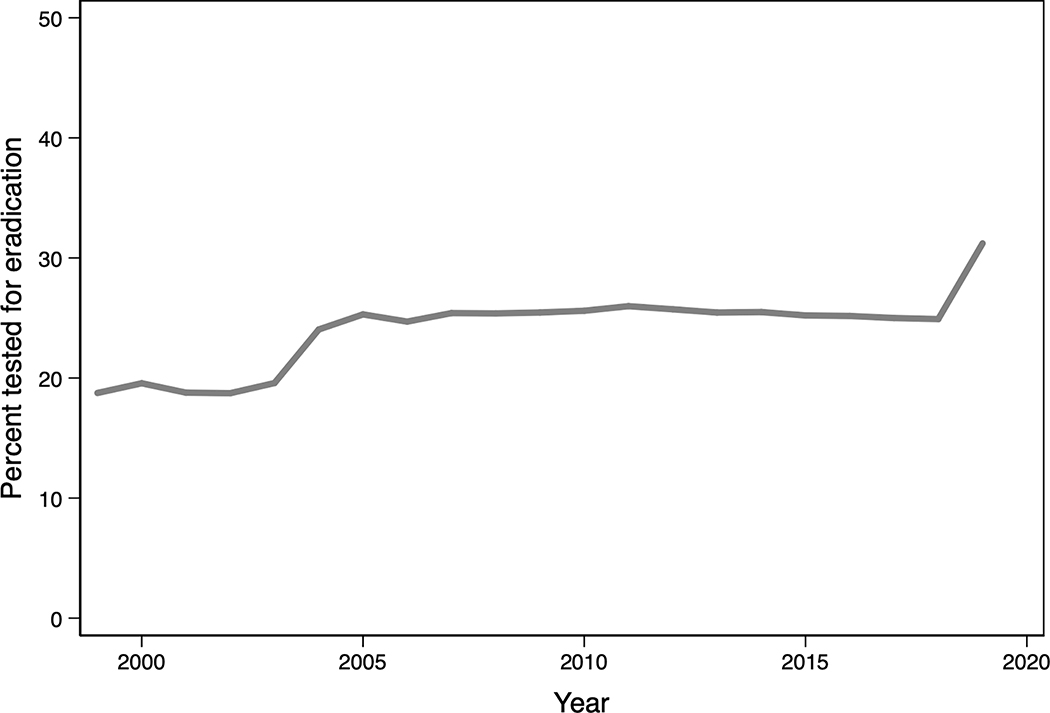

Of 27,185 patients diagnosed with HP and prescribed an eradication regimen, 6486 (23.9%) were tested for eradication. Figure 1 displays trends of treatment over time across facilities nationwide. While retesting has improved over the years, and there is a positive trend towards testing over time (Z = 2.86, p =0.004), the highest level of retesting (in 2019) only achieved retesting in 31.2%.

Figure 1:

Mean adjusted levels of retesting by year, for all facilities nationwide

Table 1 compares patients who were retested versus those who were not. Female patients were less likely to be tested for eradication. Patients initially diagnosed by pathology were only retested 22.1%, as compared to 30% of those diagnosed by stool antigen and 34.1% of those initially diagnosed by urea breath test, p<0.001.

Table 1:

Comparison of patients tested versus not tested for eradication

| Not tested for eradication (n=20,699) | Tested for eradication (n=6,486) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) at H. pylori diagnosis, median (IQR) | 62.2 (54.0, 69.2) | 60.9 (52.1, 67.7) | <0.001 |

| Female gender (n=2,090) | 1429 (68.4%) | 661 (31.6%) | <0.001 |

| Race | 0.11 | ||

| White (n=13,862) | 10,615 (76.6%) | 3247 (23.4%) | |

| Black or African American (n=10,464) | 7962 (76.1%) | 2502 (23.9%) | |

| American Indian / Alaska Native (n=271) | 201 (74.2%) | 70 (25.8%) | |

| Asian (n=186) | 131 (70.4%) | 55 (29.6%) | |

| Native Hawaiian / Pacific Islander (n=266) | 200 (75.2%) | 66 (24.8%) | |

| Unknown (n=2,136) | 1590 (74.4%) | 546 (25.6%) | |

| Ethnicity | <0.001 | ||

| Not Hispanic / Latino (n=22,578) | 17,328 (76.7%) | 5250 (23.3%) | |

| Hispanic or Latino (n=3,406) | 2458 (72.2%) | 948 (27.8%) | |

| Unknown (n=1,201) | 913 (76.0%) | 288 (24.0%) | |

| Smoking history (n=8,764) | 6670 (76.1%) | 2094 (23.9%) | 0.93 |

| Method of H. pylori diagnosis | <0.001 | ||

| Pathology (n=21,242) | 16,547 (77.9%) | 4695 (22.1%) | |

| Stool Antigen (n=5,773) | 4040 (70.0%) | 1733 (30%) | |

| Urea Breath Test (n=170) | 112 (65.9%) | 58 (34.1%) | |

| Poverty level of zip code where patient resided at H. pylori diagnosis | <0.001 | ||

| < 10% residing below poverty level (n=5,452) | 4174 (76.6%) | 1278 (23.4%) | |

| 10 – 24.9% residing below poverty level (n=12,939) | 9803 (75.8%) | 3136 (24.2%) | |

| 25 – 49.9% residing below poverty level (n=6,837) | 5230 (76.5%) | 1607 (23.5%) | |

| ≥50% residing below poverty level (n=769) | 631 (82.1%) | 138 (17.9%) | |

| Unknown (n=1,188) | 861 (72.5%) | 327 (27.5%) | |

| Provider who ordered initial H pylori test, where available* | <0.001 | ||

| Non-GI specialist, non-physician (n=1,319) | 719 (54.5%) | 600 (45.5%) | |

| Non-GI specialist, physician (n=3,641) | 1827 (50.2 %) | 1814 (49.8%) | |

| GI specialist, non-physician (n=281) | 40 (14.2%) | 241 (85.4%) | |

| GI specialist, physician (n=2,382) | 915 (4.4, 38.4%) | 1467 (61.6%) | |

| Academic VHA (n=16,594) | 12,555 (75.7%) | 4039 (24.3%) | 0.02 |

| Poverty level of VHA | <0.001 | ||

| <10% low SES at VHA (n=761) | 612 (80.4%) | 149 (19.6%) | |

| 10–25% low SES at VHA (n=12,303) | 9456 (76.9%) | 2847 (23.1%) | |

| 25–50% low SES at VHA (n=13,767) | 10,359 (75.2%) | 3408 (24.8%) | |

| >50% low SES at VHA (n=354) | 272 (76.7%) | 82 (23.2%) |

Percentages represent row percent

Those unavailable were unknown

We were able to identify the provider who ordered initial testing in 7623 patients. We found that 2663 (34.9%) of the tests were ordered by gastroenterological providers, while 4960 (65.1%) were ordered by non-gastroenterology providers. Among those ordered by gastroenterological providers, 281 (10.5%) were non-physician providers, while 2382 (89.4%) were physicians. Among the tests ordered by non-gastroenterology providers, 1319 (26.6%) were ordered by non-physician providers, and 3641 (73.4%) by physicians.

When evaluating retesting by the provider who ordered the initial HP test, gastroenterological, non-physician providers had the highest rates of retesting 85.4% (Figure 2).

Figure 2:

Bar graph of percentage of patients retested, by type of provider who ordered initial test

Mixed-effects multivariable logistic regression demonstrated important factors associated with retesting (Table 2). These included patient factors: female gender (OR 1.22; 95% CI: 1.08–1.38; p=0.002) and a history of smoking (OR 1.24; 95% CI: 1.151.33; p<0.001). Being tested at an academic center was not associated with retesting. The model also demonstrated an interaction between method of initial HP diagnosis and provider who ordered the initial HP test (p<0.001), where the initial diagnosis varied by provider type. Across all methods of testing, when non-physicians who worked in gastroenterology ordered the initial HP testing, retesting was more likely. Physicians, even those who were gastroenterology specialists, were not associated with increased retesting, as compared to non-physicians who worked in non-gastroenterology settings.

Table 2:

Multivariable mixed-effects logistic regression of factors associated with being tested for eradication

| Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.002 | |

| Male | REFERENCE | |

| Female | 1.22 (1.08 – 1.38) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.05 | |

| Not Hispanic / Latino | REFERENCE | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1.10 (0.98 – 1.24) | |

| History of smoking | 1.24 (1.15 – 1.33) | p<0.001 |

| Initial H pylori diagnosis by pathology | p<0.001 | |

| Non-GI specialist, non-physician | REFERENCE | |

| Non-GI specialist, physician | 0.88 (0.44 – 1.77) | |

| GI specialist, non-physician | 2.31 (0.71 – 7.52) | |

| GI specialist, physician | 0.87 (0.43 – 1.72) | |

| Initial H pylori diagnosis by stool antigen | p<0.001 | |

| Non-GI specialist, non-physician | REFERENCE | |

| Non-GI specialist, physician | 1.01 (0.86 – 1.19) | |

| GI specialist, non-physician | 1.66 (1.00 – 2.77) | |

| GI specialist, physician | 1.01 (0.80 – 1.26) | |

| Initial H pylori diagnosis by urea breath test | p<0.001 | |

| Non-GI specialist, non-physician | REFERENCE | |

| Non-GI specialist, physician | 0.91 (0.23 – 3.65) | |

| GI specialist, non-physician | 9.5 (0.80 – 112.97) | |

| GI specialist, physician | 0.30 (0.06 – 1.58) | |

| Academic VHA | 1.23 (0.97 – 1.56) | 0.07 |

per 5-year age increase at H pylori diagnosis

Other covariates tested but not included in the final multivariable models as they were not significant (p ≥ 0.1) were: age, race, zip code poverty level where patient resided at H pylori diagnosis, and the percentage of low socioeconomic veterans served by facility at which patient was initially tested

Given that there was an increase in retesting over time, and the accompanying changes in practice patterns, we conducted a sensitivity analysis limited to the years from 2008 onwards. The results of this are presented in Supplemental Table 1. Importantly, the interaction between method of initial diagnosis and provider remained, and retesting was most likely when gastroenterology non-physicians ordered the initial test.

Even after accounting for key patient factors, retesting rates differed significantly by facility (p<0.001). Among-facility differences in retesting rates were significantly different among facilities in the same geographic area, as defined by Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs) (Figures 3a and 3b), and in different states (Figure 4).

Figure 3:

Comparison of unadjusted (3A) and adjusted (3B) levels of retesting, by Veterans Integrated Service Networks

Figure 4:

Rates of retesting map. Adjusted rates calculated by Veterans Integrated Service Networks mean testing rates across states.

DISCUSSION

Retesting rates after HP treatment are poor, with less than one in four patients undergoing eradication testing after prescription of an HP regimen, despite clear consensus emphasizing the mandatory nature of retesting. In an era of falling eradication rates and increasing HP resistance, this is an area for robust quality assurance improvement.3,12,25 Part of the difficulty with HP retesting is associated with the time between HP detection, a multi-week treatment regimen, and retesting. Transitions in care during this time, between providers and settings, are opportunities for incomplete care.17,18,26 Previous studies have demonstrated that patients with HP are frequently lost to follow-up at times of transition, particularly at hospital discharge.17,18

Our study is the largest cohort of patients with detected HP nationwide. Single center studies have demonstrated a wide range of retesting rates, below 30% to almost 70%.19,26,27 We found that only 23.9% of veterans underwent retesting, on the lower end of previously published studies, but consistent with the wide range of rates. Given that our study provides a geographically diverse cohort of patients and our use of a random effects model was able to account for clustering of patients within facilities, variable patterns of retesting, and heterogeneity in access, our findings reliably demonstrate important gaps in HP-related care. As noted above, HP is associated with a multitude of gastrointestinal disorders, yet appropriate eradication is not always employed after detection.

After implementation of National Institutes of Health recommendations to treat all discovered HP, treatment went from <10% to close to 90% over two decades.17,28–30Similarly, for retesting, we demonstrate there is work to be done. Systems based changes have been proposed at care transitions, and retesting for HP after treatment is no different.31 The VHA is unique in its comprehensive electronic medical record, and though alerts are certainly not guaranteed to improve adherence, targeted alerts may be beneficial.27,32 And while the VHA is unique, it is an appropriate marker of quality for health care in the US. Previous studies have demonstrated that the VHA is often better than non-VHA settings at achieving high quality care, across disciplines and settings.33–37 HP retesting has not been explicitly compared in VHA and non-VHA systems, but should not vary significantly from other quality care metrics. Still, future studies should validate our findings in other large, non-VHA settings.

We identify increasing trends over time regarding retesting. Part of the increasing retesting rates over time can be attributed to the recognition of increasing antibiotic rates, particularly clarithromycin, an important component of HP eradication regimens.25,38

A notable finding demonstrates that if initial HP testing was ordered by non-physician providers who work in gastroenterology settings, patients were more likely to be retested. Tests ordered by physicians were less likely to be retested. This is similar to a recent study by Tapper, et al., which evaluated the impact of advanced practice providers on cirrhosis care.39 In that study, non-physicians, particularly those in hepatology, were more likely to adhere to quality metrics, such as hepatocellular carcinoma and variceal screening, and hepatic encephalopathy management. Nonphysician providers had improved outcomes (readmission and mortality). HP retesting to confirm eradication is similar to hepatocellular carcinoma screening, where <20% of cirrhotic patients appropriately undergo screening.40 Our findings add to growing literature that non-physician providers visits are an important adjunct, particularly in longitudinal instances, such as cancer screenings or HP retesting.40–42 Two important caveats should be noted regarding this finding: 1) ordering provider does not capture instances in which non-physician providers are working in tandem with physicians, and may overestimate the independence of the non-physician provider role, and 2) we were able to determine provider in 7623 of 27,185 cases (28.0%), which, while still a large number, is a relatively small proportion of the total cohort. Furthermore, this does not capture instances when patients are sent for endoscopy performed by a GI physician who is not part of the longitudinal care team.

We also identified that patient factors associated with retesting: female gender and smoking history. It is possible that these patients were considered “higher risk” by their providers, due to smoking history or some other factor not apparent in our study. Neither poverty level of patient residences nor percentage of veterans of low socioeconomic status served was associated with retesting. Notably, academic medical centers were not associated with retesting.

Importantly, only a third of patients saw gastroenterologists, either physicians or non-physicians. That non-gastroenterologists are ordering HP tests in diagnostic workups underscores the fact that appropriate HP testing education and quality control is of multi-disciplinary importance. HP is considered a class 1 carcinogen, a necessary (but not sufficient) factor in the development of gastric adenocarcinoma.20,21 It is tested for in laboratories and gastroenterology suites via endoscopy (pathology) and urea breath tests (performed by nurses or technicians with gastroenterologist test interpretation). That HP is a widespread bacterium with carcinogenic potential that can be tested for without gastroenterology specific involvement makes it widely pertinent for gastroenterologists and non-gastroenterologists alike to appropriately eradicate HP. Previous literature has identified that non-specialty providers are less adherent to specialty-specific clinical practice recommendations.43 This emphasizes the need for widespread dissemination of education regarding appropriate HP treatment and eradication to the entire medical community. Given the overall poor rates of retesting, and cumbersome nature of the tests, committees who develop guidelines could consider those individuals who are most important to retest.

Limitations of this study include its retrospective nature, and the inherent limitations of retrospective studies. For example, given the vastness of the sample, it would be implausible to determine who the patient’s primary provider was, who may be considered most responsible for retesting. There may be misclassification of the ordering provider, with misclassification of setting (i.e. the provider selected the incorrect visit). We were only able to identify ordering provider in about 30% of cases. Importantly, when we were able to identify a provider, the rates of retesting were >50%. This is markedly higher than the overall retesting rates of the full cohort (23.9%), and though not perfect, more acceptable. We hypothesize that this reflects continuity of care in ambulatory settings, as opposed to non-ambulatory settings, i.e. in an inpatient admission for gastrointestinal bleeding, where follow-up is less robust. This finding would only re-emphasize the need for widespread education regarding appropriate HP treatment and eradication guidelines. We did not capture ordered but incomplete retesting, so patients who did not complete ordered retesting would not be included in retesting rates, though there is no suggestion that completion rates should be differential between physicians and non-physicians or gastroenterological specialists versus non-specialists. We attempted to identify symptoms that led to initial testing, a factor that may impact retesting rates, and could provide a target for improving retesting rates. However, there were multiple overlapping codes that prevented our ability to key in on specific symptoms. Retesting may have been pursued selectively, depending on initial indication, which we are unable to parse out. Similarly, we are unable to identify specific indication for retesting, a potential source of information and target for process improvement. We did not use a prespecified time period in which to capture retesting (i.e. within a specified time period after index testing). While this could be helpful in order to capture the adherence to strict protocol, our findings still demonstrate an unacceptably poor rate of retesting, which would only amplify with restriction within a time period. We were further unable to distinguish ambulatory versus non-ambulatory settings for index testing, which could further identify systems-level settings (i.e. transitions of care) where HP retesting may be overlooked. However, as we note above, transitions in care, between providers and settings, are already well-described points at which a lapse in care can occur.17,18,26 Overall, our findings serve to underline the importance of implementing this quality measure across all settings and providers, not solely gastroenterologists. We were also unable to reliably distinguish between standard triple therapy and quadruple therapies, which may reflect the provider’s familiarity with guidelines, and therefore impact retesting. Lastly, there are measurement issues, including patients receiving care outside the VHA (potentially decreasing apparent retesting rates), and incomplete information (i.e. if a patient saw a gastroenterologist prior to a non-gastroenterologist ordering the test).

The strengths of our study are mainly related to the size and diversity of our unique cohort. Previous studies have been markedly smaller in size, and single-center studies. Our cohort consists of VHA facilities nationwide, inpatient and outpatient, with diverse facility, provider, and patient populations. Previous studies found that gastroenterology follow-up was associated with retesting, and we were able to further stratify by provider (physician versus non-physician).19 Importantly, we demonstrated that non-physician providers who ordered testing and worked in gastroenterological settings were most adherent to recommendations, further lending to recent literature emphasizing the role non-physician providers play in advancing care and the importance of education regarding retesting in non-gastroenterological settings. The VHA has previously been shown to be comparable (if not better) than non-VHA settings for quality of care, yet here we demonstrate poor rates of retesting among VHA populations. Future studies should validate these findings in large, non-VHA settings. Our findings demonstrate that across patients, facilities, and providers, retesting is poor, and quality assurance methods are needed.

Most importantly, we demonstrate that HP retesting for eradication confirmation remains unacceptably poor. While previously HP eradication was considered a two-step process (“test and treat”), confirming HP eradication is now mandatory. Despite this, our findings show that among the VHA, “test, treat, prove it’s gone” is not universal. Quality assurance protocols are strongly needed to improve this statistic, among both gastroenterologists and primary care providers.

Supplementary Material

WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW.

Background

Patients are supposed to be retested for eradication of Helicobacter pyloriinfection after treatment, but it is not clear how many patients are actually retested.

Finding

In an analysis of data from the Veterans Health Administration on patients with H pylori infection, we found low rates of retesting after eradication treatment. There is significant variation in rates of retesting among VHA facilities. Non-gastroenterology specialists order two-thirds of H pylori tests, emphasizing the need for widespread education.

Implications for patient care

Strategies are needed to confirm eradication of H pylori after treatment—widespread quality assurance protocols are needed.

Acknowledgments

Grant support:

Shria Kumar, MD is supported by an NIH training grant (5 T32 DK 7740-22)

Disclosures:

Shria Kumar, MD: Travel (Boston Scientific Corporation, Olympus Corporation)

David C. Metz, MBBCh: Consulting (Takeda, Lexicon, AAA. Novartis), Grant Support (Lexicon, Wren Laboratories, Ipsen, AAA)

David E. Kaplan, MD, MSc: Research grant support (Gilead, Bayer)

David S. Goldberg, MD, MSCE: Research grant support (Gilead, Merck, AbbVie, Zydus)

Abbreviations

- CDW

Corporate Data Warehouse

- ICD

International Classification of Diseases

- VHA

Veterans Health Administration

- VISN

Veterans Integrated Service Network

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an article that has undergone enhancements after acceptance, such as the addition of a cover page and metadata, and formatting for readability, but it is not yet the definitive version of record. This version will undergo additional copyediting, typesetting and review before it is published in its final form, but we are providing this version to give early visibility of the article. Please note that, during the production process, errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gerrits MM, van Vliet AH, Kuipers EJ, Kusters JG. Helicobacter pylori and antimicrobial resistance: molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6(11):699–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crowe SE. Helicobacter pylori Infection. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(12):1158–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fallone CA, Moss SF, Malfertheiner P. Reconciliation of Recent Helicobacter pylori Treatment Guidelines in a Time of Increasing Resistance to Antibiotics. Gastroenterology. 2019;157(1):44–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bamford KB, Bickley J, Collins JS, et al. Helicobacter pylori: comparison of DNA fingerprints provides evidence for intrafamilial infection. Gut.1993;34(10):13481350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu Y, Wan JH, Li XY, Zhu Y, Graham DY, Lu NH. Systematic review with metaanalysis: the global recurrence rate of Helicobacter pylori. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46(9):773–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hooi JKY, Lai WY, Ng WK, et al. Global Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(2):420–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang F, Meng W, Wang B, Qiao L. Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric inflammation and gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 2014;345(2):196–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Correa P Helicobacter pylori and gastric carcinogenesis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19 Suppl 1:S37–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chey WD, Leontiadis GI, Howden CW, Moss SF. ACG Clinical Guideline: Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(2):212239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miftahussurur M, Yamaoka Y. Diagnostic Methods of Helicobacter pylori Infection for Epidemiological Studies: Critical Importance of Indirect Test Validation. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:4819423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burucoa C, Delchier JC, Courillon-Mallet A, et al. Comparative evaluation of 29 commercial Helicobacter pylori serological kits. Helicobacter. 2013;18(3):169179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Serag HB, Kao JY, Kanwal F, et al. Houston Consensus Conference on Testing for Helicobacter pylori Infection in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(7):992–1002 e1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Di Mario F, Cavallaro LG, Scarpignato C. ‘Rescue’ therapies for the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Dig Dis. 2006;24(1–2):113–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phull PS, Halliday D, Price AB, Jacyna MR. Absence of dyspeptic symptoms as a test of Helicobacter pylori eradication. BMJ. 1996;312(7027):349–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reilly TG, Walt RP. Testing to check success of treatment to eradicate H pylori. Routine retesting is necessary. BMJ. 1996;312(7042):1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miehlke S, Loibl R, Meszaros S, Labenz J. [Diagnostic and therapeutic management of helicobacter pylori: a survey among German gastroenterologists in private practice]. Z Gastroenterol. 2016;54(10):1130–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nazareno J, Driman DK, Adams P. Is Helicobacter pylori being treated appropriately? A study of inpatients and outpatients in a tertiary care centre. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21(5):285–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoon H, Lee DH, Jang ES, et al. Optimal initiation of Helicobacter pylori eradication in patients with peptic ulcer bleeding. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(8):2497–2503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feder R, Posner S, Qin Y, Zheng J, Chow SC, Garman KS. Helicobacter pyloriassociated peptic ulcer disease: A retrospective analysis of post-treatment testing practices. Helicobacter. 2018;23(6):e12540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar S, Metz DC, Kaplan DE, Goldberg DS. Seroprevalence of H. pylori infection in a national cohort of veterans with non-cardia gastric adenocarcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar SM, D.C., Ellenberg S, Kaplan DE, Goldberg DS Risk Factors and Incidence of Gastric Cancer After Detection of Helicobacter pylori Infection: A Large Cohort Study. Gastroenterology. 2019(Accepted). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seltman HJ. Experimental design and analysis. 2018. http://www.stat.cmu.edu/~hseltman/309/Book/Book.pdf. Accessed 10/10/2019.

- 23.Wiley LK, Shah A, Xu H, Bush WS. ICD-9 tobacco use codes are effective identifiers of smoking status. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20(4):652–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldberg DS, French B, Forde KA, et al. Association of distance from a transplant center with access to waitlist placement, receipt of liver transplantation, and survival among US veterans. JAMA. 2014;311(12):12341243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thung I, Aramin H, Vavinskaya V, et al. Review article: the global emergence of Helicobacter pylori antibiotic resistance. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43(4):514–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yogeswaran K, Chen G, Cohen L, et al. How well is Helicobacter pylori treated in usual practice? Can J Gastroenterol. 2011;25(10):543–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong F, Ou G, Svarta S, et al. Do we eradicate Helicobacter pylori in hospitalized patients with peptic ulcer disease? Can J Gastroenterol. 2013;27(11):636–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cotton P NIH consensus panel urges antimicrobials for ulcer patients, skeptics concur with caveats. JAMA. 1994;271(11):808–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roll J, Weng A, Newman J. Diagnosis and treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection among California Medicare patients. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(9):994998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thamer M, Ray NF, Henderson SC, Rinehart CS, Sherman CR, Ferguson JH. Influence of the NIH Consensus Conference on Helicobacter pylori on physician prescribing among a Medicaid population. Med Care. 1998;36(5):646–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roy CL, Poon EG, Karson AS, et al. Patient safety concerns arising from test results that return after hospital discharge. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(2):121–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kane-Gill SL, O’Connor MF, Rothschild JM, et al. Technologic Distractions (Part 1): Summary of Approaches to Manage Alert Quantity With Intent to Reduce Alert Fatigue and Suggestions for Alert Fatigue Metrics. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(9):1481–1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chi RC, Reiber GE, Neuzil KM. Influenza and pneumococcal vaccination in older veterans: results from the behavioral risk factor surveillance system. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(2):217–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keating NL, Landrum MB, Lamont EB, et al. Quality of care for older patients with cancer in the Veterans Health Administration versus the private sector: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(11):727–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Keyhani S, Ross JS, Hebert P, Dellenbaugh C, Penrod JD, Siu AL. Use of preventive care by elderly male veterans receiving care through the Veterans Health Administration, Medicare fee-for-service, and Medicare HMO plans. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(12):2179–2185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lynch CP, Strom JL, Egede LE. Effect of Veterans Administration use on indicators of diabetes care in a national sample of veterans. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2010;12(6):427–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nelson KH, Willens HJ, Hendel RC. Utilization of radionuclide myocardial perfusion imaging in two health care systems: assessment with the 2009 ACCF/ASNC/AHA appropriateness use criteria. J Nucl Cardiol. 2012;19(1):3742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shiota S, Reddy R, Alsarraj A, El-Serag HB, Graham DY. Antibiotic Resistance of Helicobacter pylori Among Male United States Veterans. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(9):1616–1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tapper EB, Hao S, Lin M, et al. The Quality and Outcomes of Care Provided to Patients with Cirrhosis by Advanced Practice Providers. Hepatology. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tapper EB. Building Effective Quality Improvement Programs for Liver Disease: A Systematic Review of Quality Improvement Initiatives. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(9):1256–1265 e1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Swan M, Ferguson S, Chang A, Larson E, Smaldone A. Quality of primary care by advanced practice nurses: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2015;27(5):396–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Horrocks S, Anderson E, Salisbury C. Systematic review of whether nurse practitioners working in primary care can provide equivalent care to doctors. BMJ. 2002;324(7341):819–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leinung MC, Gianoukakis AG, Lee DW, Jeronis SL, Desemone J. Comparison of diabetes care provided by an endocrinology clinic and a primary-care clinic. Endocr Pract. 2000;6(5):361–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.