Abstract

Objectives

The prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease and associated disorders is increasing. Rural residents in the United States have less access to memory care specialists and educational and community resources than in other areas of the country. Over a decade ago, we initiated an interdisciplinary rural caregiving telemedicine program to reach Kentucky residents in areas of the state where resources for supporting individuals with dementia are limited. Telemedicine programs involve a short informational presentation followed by a question and answer session; programs are offered 4 times a year. The purpose of this study was to explore questions asked over 1 year of the rural caregiving telemedicine program—encompassing 5 programs—to identify the scope of dementia-related knowledge gaps among attendees.

Methods

Questions from the 5 programs were recorded and content analyzed to identify areas of frequent informational requests.

Results

There were a total of 69 questions over the 5 sessions. For each program, questions ended due to time constraints rather than exhausting all inquiries. The most common topical areas of questions related to risk factors, behavioral management, diagnosis, and medications.

Discussion and Implications

This study highlights that rural caregivers in Kentucky have diverse dementia educational needs. Rural communities may benefit from additional, targeted resources addressing these common areas of unmet informational needs.

Keywords: rural caregivers, content analysis, dementia, education, telemedicine, rural

In rural America, the population is “older” than the nation as a whole.1 Since Alzheimer’s disease and dementia are associated with age, their prevalence in rural communities is expected to increase.2 Despite the great need in rural areas, memory care specialists and educational resources for disease identification and disease management are much sparser in rural communities than in other areas of the United States.3 Rural residents also face numerous socioeconomic disadvantages, making access to such resources an even greater challenge.4,5

Caregiving in Rural Communities

The majority of caregiving occurs at home by informal caregivers.6 Caregiving can lead to burden and fatigue, as well as mental and physical health issues.7–9 Burden is likely to be exacerbated when caregivers lack access to information and support to help navigate caregiving responsibilities, and unfortunately caregivers often do not receive desired information from medical providers.10 Rural residents may also face additional challenges and stress due to social isolation, inadequate financial resources, fewer public transportation options, and greater distances to access health care.11–18 These challenges are compounded by the sparsity of educational resources and programming in rural communities.19

Addressing the support and informational needs of rural caregivers of individuals with dementia requires innovative approaches20 such as the use of video teleconference, also known as telehealth, to enhance the opportunity for gaining information via health care professionals. Telehealth can serve as a platform for providing families with health consultation for disease management,21 peer support,22 and psychoeducation.23 A study exploring a videoconference support group for rural caregivers of individuals with frontotemporal dementia found the group helped overcome distance barriers and had high participation and low attrition.22 However, one study evaluating an online platform for a caregiver psychoeducational program found that while the program met informational needs, participants felt the program lacked relevance, engagement, and informal support; they concluded that online programs need to be more dynamic and personalized.23

Purpose of Research

Although substantial research has examined the experiences of caregivers of persons with dementia and factors that affect the caregiving experience, research is limited in understanding the specific informational needs of caregivers for persons with dementia in rural areas. The purpose of this brief report is to examine the questions asked over 1 year of programming to identify the scope of dementia-related knowledge gaps among attendees of rural communities. This study focuses on data from the existing rural caregiving educational program and does not introduce any additional research procedures, aside from recording questions asked.

Methods

Rural Caregiver Telemedicine Program

In order to help address the gap in accessible dementia care information for caregivers in rural communities, over a decade ago we began an interdisciplinary rural caregiving telemedicine program. This program was designed to reach Kentucky residents in areas where resources for supporting individuals with dementia are limited. No formal definition of rural is used for eligibility; rather, participating sites need to be outside major metropolitan areas. The program is focused on rural residents to target the content and delivery specifically to their needs. In earlier years of the program’s development, individuals from Kentucky cities participated; however, the rural attendees reported that they preferred an exclusively rural program, as the resources available and realities of the caregiving experience differ in rural communities. Differences in educational attainment also meant that urban participants’ questions may have been too esoteric for, and not aligned with the informational needs of, rural attendees.

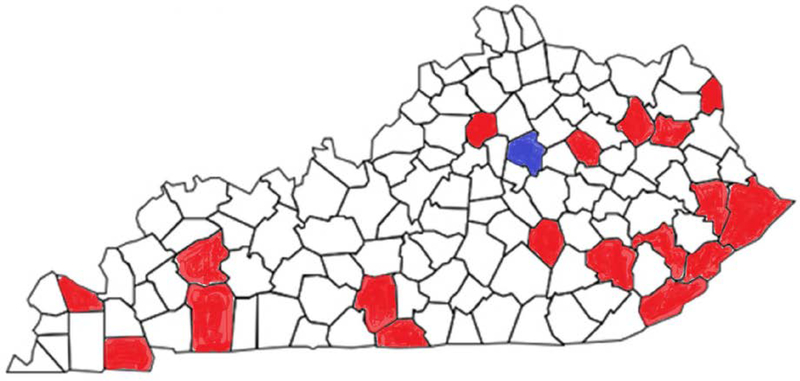

Figure 1 demonstrates the geographic regions currently encompassed in the program. The blue indicates Lexington, where the program delivery occurs. The red counties represent the participating sites in rural areas across the state. Telemedicine programs are offered quarterly, typically with a short presentation followed by a question and answer session. The question and answer session is moderated so that each site can ask a question; if time allows, sites can pose additional questions. Staff in attendance generally include a behavioral neurologist, a family care support specialist, a gerontologist, and a community outreach worker with the Alzheimer’s Association. On occasion special guests attend to augment existing expertise. The program is hosted in a variety of settings, including hospital conference rooms, long-term care facilities, and local extension offices. Each site has a facilitator whose background may vary from someone who helps with the videoconferencing technology alone to those with health care expertise. Sites connect to the presentation via Zoom Video Conferencing (Zoom Video Communications, San Jose, California) that enables both audio and visual information via computer; sites without such capabilities or with slow connectivity are provided the option of audio only via phone. All sites can test their connection in advance to troubleshoot technical issues, and audiovisual assistance is available the day of the program via phone.

Figure 1.

Geographical Reach of the Rural Caregiving Program

The program’s reach has grown over time, demonstrating a demand for greater educational resources in rural communities. To promote program attendance, prior attendees are sent a flyer for the upcoming program. The Alzheimer’s Association also contacts individuals in the area who have attended classes, programs, or support groups, or who have contacted the Association’s Helpline. The program is also included in the bulletin of upcoming events and the flyer is shared with community contacts. The Alzheimer’s Association also works with local media and includes the program in community calendars. Site facilitators may also help spread the word. Program participants are informal caregivers; eg, family members including spouses, siblings, and children, or friends, who are providing care for a loved one. Contact information is requested to share information for upcoming programs, but individual demographics and relationship to the care recipient are not collected. Following each session, attendees share general comments and suggestions, but no formal evaluation of program impact is conducted. Since the program is designed for educational purposes only, no IRB approval was needed.

Procedures

Over the course of 5 programs, occurring between January 2017 and January 2018, we recorded by hand all questions asked across sites and noted the gender of the question-asker. Individuals do not introduce themselves when speaking, making it impossible to determine whether multiple questions came from the same individual over time. Questions were then typed up and content-analyzed to identify areas of frequent informational requests. All questions were sorted, common areas were identified for these groupings and reorganized and iteratively evaluated, until a comprehensive set of categories was identified that fit the data. Author Bardach completed the initial qualitative content analysis, grouping questions into inductive categories of topical areas, but all categorizations were reviewed by author Gibson to ensure consistent interpretation.24

Results

Over the 5 sessions, a total of 448 individuals registered to attend. When accounting for individuals who attended more than 1 program, 294 unique individuals attended 1 of the 5 sessions. Session attendance ranged from 52 to 164 across sessions, with attendees participating in a mean of 1.3 sessions over the 5 offerings (range 1–5). Over the course of the 5 programs, 17 sites had pre-registered attendees. Over the 5 sessions, a total of 69 questions were asked; 13 of those questions came from the dedicated question and answer session. Fifty-three of the questions were from female attendees, and the remaining 16 were from male attendees. In all cases, questions ended due to time constraints within the program, rather than exhausting all inquiries. The program topics were late-state dementia and end-of-life care, genetic and familial risk for Alzheimer’s disease, management of behavioral symptoms in dementia, understanding dementia signs and symptoms, and a dedicated question and answer session.

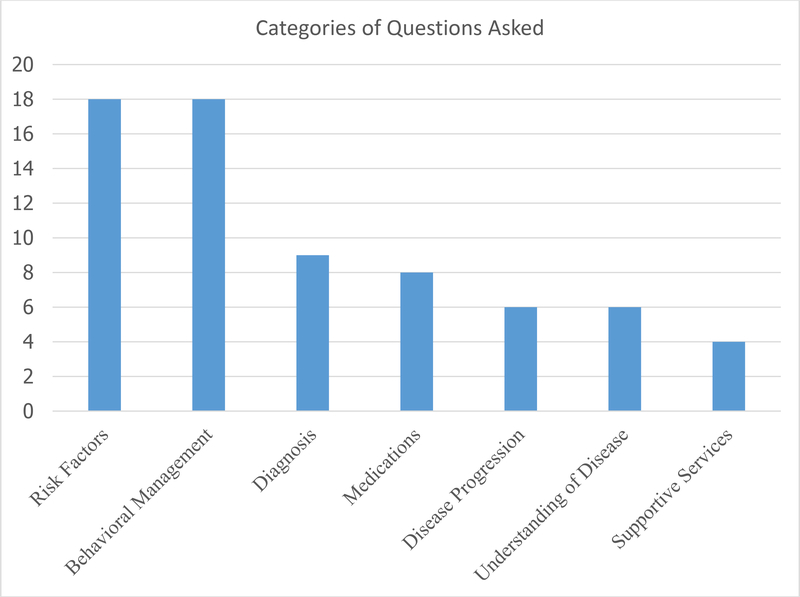

The most common question categories related to risk factors (n=18), behavioral management (n=18), diagnosis (n=9), and medications (n=8). Risk factors encompassed questions focused on genetic risk (n=4) as well as other health factors and life events and their possible contribution to the development of dementia (n=14). Behavioral management included questions regarding food and mealtime (n=5), questions focused on aggression and personality (n=3), as well as questions across a wide array of topics (n=10), ranging from ways to provide comfort for individuals with dementia, ways to encourage participation in activities, and strategies for handling inappropriate behaviors. Diagnosis encompassed discussion on the need and role of cognitive tests, the role of a neurologist, steps involved in diagnosis, the need for MRIs or other imaging, and the process of setting up an evaluation. Questions about medications included a focus on Alzheimer’s disease medications for treatment and prevention (n=5) as well as questions about the impact of other medications on dementia symptoms and progression (n=3). Less common categories of questions included questions pertaining to disease progression (n=6), understanding of disease (n=6), and supportive services (n=4). See Table 1 for each of these categories and several sample questions within each category.

Table 1.

Question Categories and Sample Questions

| Risk Factors |

| Does loss of hearing cause or lead to Alzheimer’s disease? |

| Are there common risk genes? |

| Behavioral Management |

| How do you motivate the patient to get up and do something? |

| Are there things you can do about agitation? |

| Diagnosis |

| If you have a loved one who you suspect has AD, would recommend seeing a neurologist for a proper diagnosis of these symptoms? |

| Should we request a second opinion? |

| Medications |

| Are there medications that slow the progression? |

| How long will he take those medications? |

| Disease Progression |

| How do you measure decline? |

| Can you tell me about the different stages and what to expect? |

| Understanding of Disease |

| What is the difference between dementia versus Alzheimer’s disease? |

| Are seizures common with people with dementia? |

| Supportive Services |

| Are there any programs to help pay for the medicines? |

| Is there a limit to how long someone can be on hospice? |

Figure 2 provides a visual representation of the categories of questions asked.

Figure 2.

Categories of Questions Asked

Participants could hear all questions and answers; accordingly, within a session the same questions were not repeated. Similar questions could re-occur during subsequent sessions; all questions were addressed regardless of their novelty.

Discussion

This study highlights the diverse dementia educational needs among rural caregivers in Kentucky. Greater efforts to provide dementia-specific educational resources and inform rural residents of available services and supports should be made. Innovative approaches to reach caregivers in rural areas are needed to address unmet informational needs. Rural caregivers clearly desire information regarding risk factors, behavioral management, obtaining a diagnosis, and medication use. Caregivers also sought out practical ways to incorporate this information in their local contexts to improve care and well-being for their loved ones. Communication and information technology can reduce distance barriers faced by underserved communities in rural areas to enhance access to expert opinions and quality information. The group context of the current telemedicine approach enables attendees to benefit from other attendees’ questions. The live and interactive nature of the program enables customized responses to ensure comprehension. The varied backgrounds of the panelists provide for multiple perspectives, enabling more holistic and comprehensive suggestions for maximizing quality of life for the caregiver and care recipient. This study highlights the importance of conveying general information (eg, how Alzheimer’s disease is different from dementia) as well as practical tips for daily life.

Future research may want to explore how to continue to build upon such technology to reach rural caregivers in broader areas while still providing some level of social support, as caregiver support has many health benefits25–27and can delay nursing home placement of the care recipient.28 While program comments suggest the sessions are well received and attendees appreciate the information and encouragement provided, the overall program impact and extent to which participation leads to feelings of support remain areas for future inquiry.20,29 Exploring the optimal amount of information to convey per session so as not to overwhelm attendees, experimenting with ways to better structure question and answer sessions to maximize utility and applicability, and surveying attendees for preferred session frequency may help enhance the program’s impact.30 The fact that each session ran out of time rather than exhausting questions suggests that attendees still have unmet informational needs. While some of the above suggestions may help reduce these unmet needs, identifying additional strategies to disseminate and share information in timely, relevant ways would be beneficial.

While it takes additional effort to record questions and critically evaluate educational programs, doing so over time will enable exploration of stability or variation in informational needs. Including additional data collection elements (on both attendees and outcomes) would enhance the ability to evaluate and continually improve the program. The initial questions in each question and answer session often seemed influenced by the session’s topic; however, the range of questions suggests the topic foci did not overly constrict inquiries. The challenge of trying to conduct research on an educational program without altering the program itself creates some limitations (eg, limited information about caregivers in attendance), but it offers the strength of providing real-world insight. While knowledge gains were not assessed, informal feedback and the program’s continued success demonstrate the perceived value to attendees. Future research should explore whether caregiver resilience and self-efficacy can improve through such programs.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to all the caregivers who participate in our programs to better meet the needs of their loved ones. Thank you also to the site facilitators and other professionals and organizations, including the Alzheimer’s Association, who help make these programs possible.

Funding: The project described was supported by the National Institute on Aging P30 AG028383. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

References

- 1.Pew Research Center. 2018. https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2018/05/22/demographic-and-economic-trends-in-urban-suburban-and-rural-communities, Accessed 9/20/2019.

- 2.Alzheimer’s Disease International. Dementia statistics. 2019. https://www.alz.co.uk/research/statistics, Accessed 9/20/2019.

- 3.Ruggiano N, Brown EL, Li J, Scaccianoce M. Rural Dementia Caregivers and Technology: What Is the Evidence? Research in gerontological nursing. 2018;11(4):216–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh GK, Siahpush M. Widening rural–urban disparities in life expectancy, US, 1969–2009. American journal of preventive medicine. 2014;46(2):e19–e29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rural Health Research Gateway. Rural Communities: Age, Income, and Health Status. 2018. https://www.ruralhealthresearch.org/assets/2200-8536/rural-communities-age-income-health-status-recap.pdf, Access 9/20/19

- 6.Alzheimer’s Association. 2019 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dementia. 2019;15(3):321–387. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dassel KB, Carr DC. Does Dementia Caregiving Accelerate Frailty? Findings From the Health and Retirement Study. Gerontologist. 2016;56(3):444–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fonareva I, Oken BS. Physiological and functional consequences of caregiving for relatives with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26(5):725–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park M, Choi S, Lee SJ, et al. The roles of unmet needs and formal support in the caregiving satisfaction and caregiving burden of family caregivers for persons with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2018;30(4):557–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gibson AK, Anderson KA. Difficult Diagnoses: Family Caregivers’ Experiences During and Following the Diagnostic Process for Dementia. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias. 2011;26(3):212–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baernholdt M, Yan G, Hinton I, Rose K, Mattos M. Quality of life in rural and urban adults 65 years and older: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination survey. J Rural Health. 2012;28(4):339–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coyle CE, Dugan E. Social isolation, loneliness and health among older adults. Journal of aging and health. 2012;24(8):1346–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGrail MR, Humphreys JS, Ward B. Accessing doctors at times of need-measuring the distance tolerance of rural residents for health-related travel. BMC health services research. 2015;15:212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hung P, Henning-Smith CE, Casey MM, Kozhimannil KB. Access To Obstetric Services In Rural Counties Still Declining, With 9 Percent Losing Services, 2004–14. Health Affairs. 2017;36(9):1663–1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adelman RD, Tmanova LL, Delgado D, Dion S, Lachs MS. Caregiver burden: a clinical review. Jama. 2014;311(10):1052–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beaudoin CE, Wendel ML, Drake K. A Study of Individual-Level Social Capital and Health Outcomes: Testing for Variance between Rural and Urban Respondents. Rural Sociology. 2014;79(3):336–354. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Branger C, Burton R, O’Connell ME, Stewart N, Morgan D. Coping with cognitive impairment and dementia: Rural caregivers’ perspectives. Dementia (London, England). 2016;15(4):814–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monahan DJ. Family Caregivers for Seniors in Rural Areas. Journal of Family Social Work. 2013;16(1):116–128. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glueckauf RL, Stine C, Bourgeois M, et al. Alzheimer’s Rural Care Healthline: Linking Rural Caregivers to Cognitive-Behavioral Intervention for Depression. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2005;50(4):346–354. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bauer M, Fetherstonhaugh D, Blackberry I, Farmer J, Wilding C. Identifying support needs to improve rural dementia services for people with dementia and their carers: A consultation study in Victoria, Australia. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2019;27(1):22–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dang S, Gomez-Orozco CA, van Zuilen MH, Levis S. Providing Dementia Consultations to Veterans Using Clinical Video Telehealth: Results from a Clinical Demonstration Project. Telemedicine journal and e-health. 2018;24(3):203–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Connell ME, Crossley M, Cammer A, et al. Development and evaluation of a telehealth videoconferenced support group for rural spouses of individuals diagnosed with atypical early-onset dementias. Dementia (London, England). 2014;13(3):382–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cristancho-Lacroix V, Wrobel J, Cantegreil-Kallen I, Dub T, Rouquette A, Rigaud AS. A web-based psychoeducational program for informal caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Journal of medical Internet research. 2015;17(5):e117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2008;62(1):107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boehm A, Eisenberg E, Lampel S. The contribution of social capital and coping strategies to functioning and quality of life of patients with fibromyalgia. The Clinical journal of pain. 2011;27(3):233–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Calvo R, Zheng Y, Kumar S, Olgiati A, Berkman L. Well-being and social capital on planet earth: cross-national evidence from 142 countries. PloS one. 2012;7(8):e42793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, Seeman TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Social science & medicine (1982). 2000;51(6):843–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goodwin JS, Howrey B, Zhang DD, Kuo YF. Risk of continued institutionalization after hospitalization in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66(12):1321–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gibson A, Holmes SD, Fields NL, Richardson VE. Providing Care for Persons with Dementia in Rural Communities: Informal Caregivers’ Perceptions of Supports and Services. Journal of gerontological social work. 2019:1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wald C, Fahy M, Walker Z, Livingston G. What to tell dementia caregivers—the rule of threes. International journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2003;18(4):313–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]