Abstract

The Hippo pathway effector Yes-associated protein (YAP) is localized to the nucleus and transcriptionally active in a number of tumor types, including a majority of human cholangiocarcinomas (CCA). YAP activity has been linked to chemotherapy resistance and has been shown to rescue KRAS and BRAF inhibition in RAS/RAF driven cancers; however the underlying mechanisms of YAP-mediated chemoresistance have yet to be elucidated. Herein, we report that the tyrosine phosphatase SHP2 directly regulates the activity of YAP by dephosphorylating pYAPY357 even in the setting of RAS/RAF mutations, and that diminished SHP2 phosphatase activity is associated with chemoresistance in CCA. A screen for YAP interacting tyrosine phosphatases identified SHP2, and characterization of CCA cell lines demonstrated an inverse relationship between SHP2 levels and pYAPY357. Human sequencing data demonstrated lower SHP2 levels in CCA tumors as compared to normal liver. Cell lines with low SHP2 expression and higher levels of pYAPY357 were resistant to gemcitabine and cisplatin. In CCA cells with high levels of SHP2, pharmacologic inhibition or genetic deletion of SHP2 increased YAPY357 phosphorylation and expression of YAP target genes, including the anti-apoptotic regulator MCL1, imparting resistance to gemcitabine and cisplatin. In vivo evaluation of chemotherapy sensitivity demonstrated significant resistance in xenografts with genetic deletion of SHP2; which could be overcome utilizing an MCL1 inhibitor.

Keywords: BRAF, cholangiocarcinoma, cisplatin, gemcitabine, KRAS, phosphatase, tyrosine phosphorylation

INTRODUCTION

Cancer of the biliary tract, cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), is increasing in worldwide incidence [1–3]. Unfortunately, treatment options remain limited, with standard chemotherapy regimens providing only modest increases in patient survival. The median overall survival with the current standard-of-care systemic chemotherapy regimen of gemcitabine and cisplatin is <1 year [4]. Therapeutic advances for CCA will require an understanding of the oncogenic signaling pathways driving this malignancy and response to therapy. The Hippo pathway effector, Yes-associated protein (YAP), has been implicated in CCA oncogenesis and progression [5–12]. Therefore, we have continued to evaluate YAP signaling in CCA, and more specifically its phospho-regulation. Our group and others have noted that a significant proportion of CCA specimens have YAP localized to the nucleus, presumably representing a co-transcriptionally active molecule[5–7, 10, 11]. Importantly, we have further observed that nuclear YAP is tyrosine phosphorylated in CCA, which may have significant functional and targeting implications [9].

The canonical phospho-regulatory pathway for YAP, the Hippo pathway, is a kinase module of serine/threonine kinases (MST1/2 and LATS1/2) and various scaffolding proteins (MOB1 and SAV), that when active, culminate in serine phosphorylation of YAP leading to its cytoplasmic sequestration and or ubiquitination and degradation; such that when the Hippo pathway is active, YAP activity is restrained [13]. Therapeutic targeting of YAP via the Hippo pathway is difficult due to the lack of a dedicated cell-surface receptor for the pathway, and the fact that the pathway acts as a negative regulator; as such traditional therapeutic strategies are challenging. The interest in targeting Hippo/YAP activity stems from not only an observed upregulation in multiple cancer types, but also the observations that YAP activity can modulate sensitivity to both traditional DNA damaging agents and targeted therapies; and that YAP can rescue directed inhibition of KRAS and BRAF in RAS/RAF driven cancers. [14–25]. However, the precise mechanisms of chemoresistance tied to YAP activity have yet to be fully delineated.

In continuing to explore YAP activity in CCA and its effects on proliferation and therapeutic response, we have recently demonstrated that the tyrosine phosphorylation status of YAP is more important in determining its subcellular localization and transcriptional activity in CCA than serine phosphorylation [9]. We have linked the SRC-family kinase LCK to YAP tyrosine phosphorylation, which corroborates other reports of SRC family kinases (SFK) ability to regulate YAP activity [26–30]. Consistent with a role for LCK in regulating YAP nuclear compartmentation, tyrosine phosphatases were also implicated in YAP regulation as kinase inhibition was ineffective in regulating YAP subcellular localization in the presence of a pan-tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor [9]. Tyrosine phosphatases are known to interact with YAP, for example previous work has demonstrated a regulatory role of PTPN14 in regulating YAP activity, but this regulation was independent of the tyrosine phosphatase activity; and PTPN11 (SHP2) has been shown to interact with YAP, but it was suggested that YAP regulated SHP2 localization; however phosphatase regulation of YAP was not explored in detail [31, 32]. Given our preliminary observations we were interested in exploring the role of tyrosine phosphatases in regulating YAP activity in CCA and modulating CCA sensitivity to gemcitabine and cisplatin.

Herein, we examine tyrosine phosphatase activity regulating YAP activation in CCA and its effects on sensitivity to therapy. The results demonstrate an inverse relationship between levels of the tyrosine phosphatase SHP2 and levels of pYAPY357 in CCA cell lines. Furthermore, downregulation of SHP2 pharmacologically or utilizing CRISPR/Cas9 was associated with increased levels of YAP tyrosine phosphorylation, and consequently increased YAP nuclear localization and transcriptional co-activity. The observed increases in YAP activity were accompanied by increases in cellular proliferation and expression of the pro-survival BCL2 family member MCL1; culminating in resistance to gemcitabine and cisplatin both in vitro and in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

The human cholangiocarcinoma cell lines HuCCT-1 and KMCH, the murine CCA cell line SB1, and the human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell line (PANC1) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 0.2% primocin under standard conditions. Due to cell density and serum regulation of the Hippo pathway, cell culture experiments were performed at near confluence (~80%). For authentication of the HuCCT-1 and KMCH cell lines, short tandem repeat (STR) analysis was performed by the Genome Analysis Core of the Medical Genome Facility (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN). All cell lines underwent Mycoplasma contamination testing periodically using PlasmoTest™ -Mycoplasma Detection kit (InvivoGen). Cell lines were used within 40 passages of reanimation. All cell lines were maintained at 37 degrees Celsius in the presence of 5% CO2.

Antibodies and reagents.

SHP099 (Selleckchem), NSC87877 (Cayman), Doxycycline hyclate (Sigma), S63845 (APExBIO), Vertoporfin and Gemcitabine and Cisplatin (Cayman) was added to cells at final concentrations from 0.05–100 μM per experimental design. The following primary antibodies were used for immunoblot analysis: actin (C-11 Santa Cruz) phospho YAPY357 (ab62751 abcam) total YAP (63.7 Santa Cruz, 4912 CST), GAPDH (MAB374 Millipore), phospho SRCY416 (2101 Cell Signaling), SRC (L4A1 Cell Signaling), SHP2 (33975 Cell Signaling) and MCL-1 (ac32087 abcam). The following primary monoclonal antibody were used for immunofluorescence and/or immunohistochemistry: total YAP (63.7 Santa Cruz), phospho YAPY357 (ab62751 abcam). ProLong Antifade with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Life Technologies) was used for nuclear staining.

SHP2 Differential Expression Analysis

We examined the SHP2 (PTPN11) RSEM transformed normalized gene expression values from TCGA CHOL primary tumor samples (n=36) and compared them to GTEx normal liver samples (n=110) [33–35]. The data was downloaded from the University of California Santa Cruz’s Xenabrowser [36]. The source of the TCGA CHOL normalized expression values came from the University of North Carolina TCGA genome characterization center, and the source of the GTEx normalized expression values came from the University of California Santa Cruz Computational Genomics Lab. These gene expression values were derived from similar RNASeq experiments utilizing similar bioinformatics methods. A t-test was conducted and a box plot was constructed comparing the CHOL samples to the normal liver samples.

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblot analyses.

Whole-cell lysates were collected by adding ice cold lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technologies) containing protease inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich), phosphatase inhibitors (Roche Diagnostics) and 1 mM PMSF. Tissue sample lysates were homogenized with a glass dounce and ice cold lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors, phosphatase inhibitors and 1 mM PMSF. Samples were vortexed and lysed on ice for approximately 20 minutes. The lysed tissue was then centrifuged at 12,000g for 15 minutes to remove cellular debris. Supernatant was transferred to a clean tube and protein concentration determined by the Bradford (Sigma-Aldrich) protein assay. For immunoprecipitation, whole-cell lysates of SB1 cells that contain the FLAG-YAPS127A were incubated with equilibrated anti-FLAG M2 magnetic beads (Sigma-Aldrich) overnight at 4°C. The FLAG-YAPS127A was then eluted from the beads with FLAG peptide following manufacturer’s instructions. To conduct immunoblot analysis, proteins were then resolved by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight in 5% BSA-TBS Tween. The primary antibody dilution was 1:1000 unless otherwise indicated. After incubation membranes were washed for 30 minutes in TBS Tween and then horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies against mouse, rabbit and goat (Santa Cruz) were added to membrane at a concentration of 1:5000 and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. Immunoblots were visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) or ECL prime (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). For experiments in which multiple proteins were evaluated, membranes were stripped and reblotted.

Immunofluorescence.

Cells were grown on glass coverslips, once the cells reached desired confluency they were treated per experimental conditions. Cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100. The fixed cells were next incubated at room temperature with blocking buffer containing 5.0% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.1% glycine. Following blocking, the cells were incubated with primary antibody in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C. After washing, the cells were incubated with secondary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark. Following secondary incubation, the coverslips were again washed and mounted onto slides using ProLong Antifade (Invitrogen-Molecular Probes) containing DAPI. The slides were analyzed by fluorescent confocal microscopy (LSM 780, Zeiss).

Quantitative and qualitative PCR.

mRNA was isolated from cells and tissues using TRIzol Reagent (Ambion). Reverse transcription was performed using Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase and random primers (Life Technologies). After reverse transcription, cDNA was analyzed using real-time PCR (Light Cycler 480 II, Roche Diagnostics) for the quantitation of the target genes; SYBR Green (Roche Diagnostics) was used as the fluorophore. Expression was normalized to 18 S and relative quantification performed according to the 2−ΔCT or 2−ΔΔCT method as previously described.[37] Data are reported as fold expression compared to calibrator as geometric mean and geometric standard deviation of expression relative to calibrator. Technical replicates were completed for each run and a minimum of three biologic replicates completed for each condition/cell line. The primers used are listed in Supplemental Table 1.

TEAD reporter assay.

Global TEAD transcriptional activity was assessed in HuCCT1 and KMCH cells using a luciferase-based TEAD reporter. Cells were transduced with lentivirus encoding a reporter construct with the TEAD response elements and a minimal TATA promoter driving expression of firefly luciferase (BPS Bioscience, #79833). Transduced cells were selected with puromycin. Cells were treated with NSC or SHP099 at 10 uM for 24 hours prior to measurement of firefly luciferase activity with a luciferase assay system (BPS Bioscience).

CRISPR/Cas9 doxycycline induced knockout.

The sequences of single guide RNA (sgRNA) for SHP2 was designed using online CRISPR design tool (http://crispr.mit.edu/) and was 5′- GGTGATTACTATGACCTGTA −3′. DNA oligonucleotides for the sgRNA were synthesized and cloned into the FgH1tUTG plasmid (Addgene, Cambrdige, MA, USA). To produce lentiviruses, FgH1tSHP2 or FUCas9Cherry plasmids were transiently co-transfected into HEK293T cells with the packaging plasmids pRSV-Rev, pMDLg/pRRE and pCMV-VSV-G (all from Addgene) using FuGENE® HD Transfection Reagent (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA). After 48 and 72 hours, supernatant containing lentiviruses was harvested and passed through a 0.45-μM filter. Target KMCH cells were transduced with the lentiviruses in the presence of 8 μg/mL polybrene for 24 hours. After an additional 3 days in culture, m-cherry (Cas9) and GFP (inducible sgRNA) dual-positive cells were sorted on a single cell-basis into a 96 well plate by flow cytometry. To induce sgRNA expression, doxycycline hyclate (SIGMA, Mendota Heights, MN, USA) was added to culture medium at a final concentration of 7.5 μg/mL. The efficacy of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene deletion was determined by immunoblot analysis.

SHP2 wild-type/phosphatase mutants.

Following the manufacturer’s instructions, HuCCT-1 cells were transfected using SHP2(WT)@pLKO-Trex-SBP, a gift from Darrin Stuart (Addgene plasmid # 85457; http://n2t.net/addgene:85457; RRID:Addgene_85457) and SHP2(C459S)@pLKO-Trex-HA, a gift from Darrin Stuart (Addgene plasmid # 85459; http://n2t.net/addgene:85459; RID:Addgene_85459). Following 48-hour transfection, the cells were used for subsequent experiments.

Cell Viability.

HuCCT-1, KMCH and sgSHP2-KMCH cells were plated in triplicate in 96 well plates at a density of 3000, and 4000 cells per well respectively according to the growth characteristics of each cell line and treated with various compounds at a range of concentrations. After 24 hours cells were treated with NSC87877 (10 μM) or S63845 (5 μM) for 24, 48 and 72 hours. For combination experiments, cells were incubated for 24 hours and treated with gemcitabine and cisplatin (0.05, 0.1, 1, 10, 100 μM) for 24, 48 and 72 hours. Cell viability following treatment was assessed using [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, inner salt; MTS] and CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega, Madison, WI, USA).

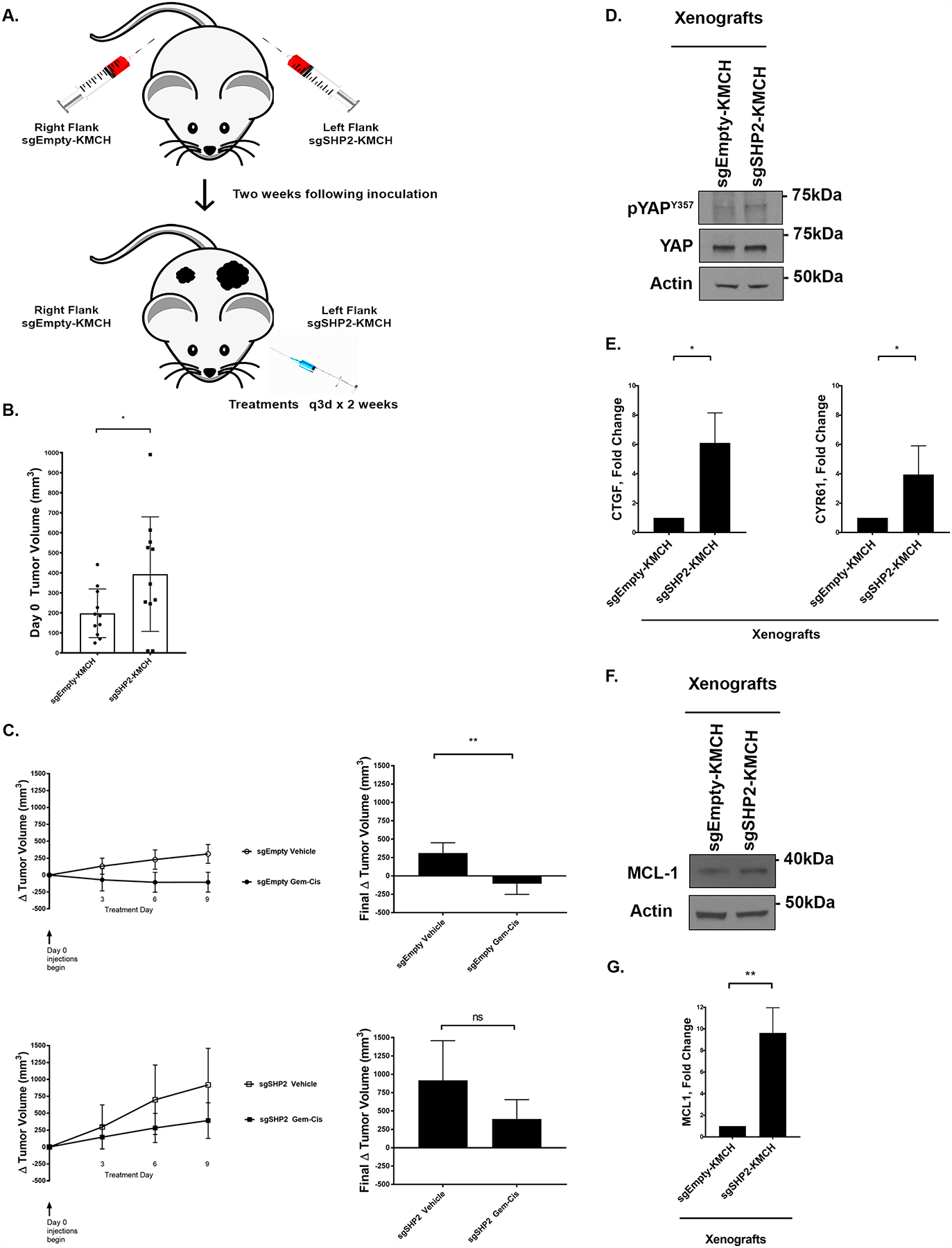

In vivo Studies.

The study protocol was approved by the institutional animal care and use committee at Mayo Clinic (A00004673–19). Experiments were carried out utilizing 8 week old male NOD/SCID mice. Xenografts were developed by separate subcutaneous injections of sgEmpty-KMCH and sgSHP2-KMCH cells (5 × 105 cells suspended in 40% DMEM and 60% Matrigel totaling 100 μL) into the flank area of each mouse. In each mouse the right flank was utilized for control tumor (sgEmpty-KMCH) and left flank utilized for experimental tumor (sgSHP2-KMCH). Tumor volume and body weight were recorded every 3 days. Treatment was initiated 2 weeks after tumor implantation when tumors had reached a volume of approximately 200 mm3. Combination gemcitabine (15mg/kg IP) and cisplatin (1mg/kg IP), gemcitabine (15mg/kg IP), cisplatin (1mg/kg IP) and S63845 (25 mg/kg IV) or normal saline was administered for 2 weeks (on days 0, 3, 6, 9, and 12). Administration of gemcitabine was 11 hours after light onset (HALO) followed by cisplatin 15 HALO. [38] Tumor progression was monitored on treatment days (0, 3, 6, 9, and 12) by measuring the width and length of the palpable mass; tumor volume was calculated using the formula: Volume (mm3) = (length X width2)/2. Animals were sacrificed and tumors extracted 15 days after the 1st treatment administration. Extracted tumor specimen volume and weights were collected.

Statistics.

Statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed Student t test or Mann-Whitney U test and GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software Inc.). Paired t test was used since data were normally distributed. All the data are presented as mean ± SEM and P value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Tyrosine phosphatase levels are altered in CCA and have an inverse relationship to YAP phosphorylation.

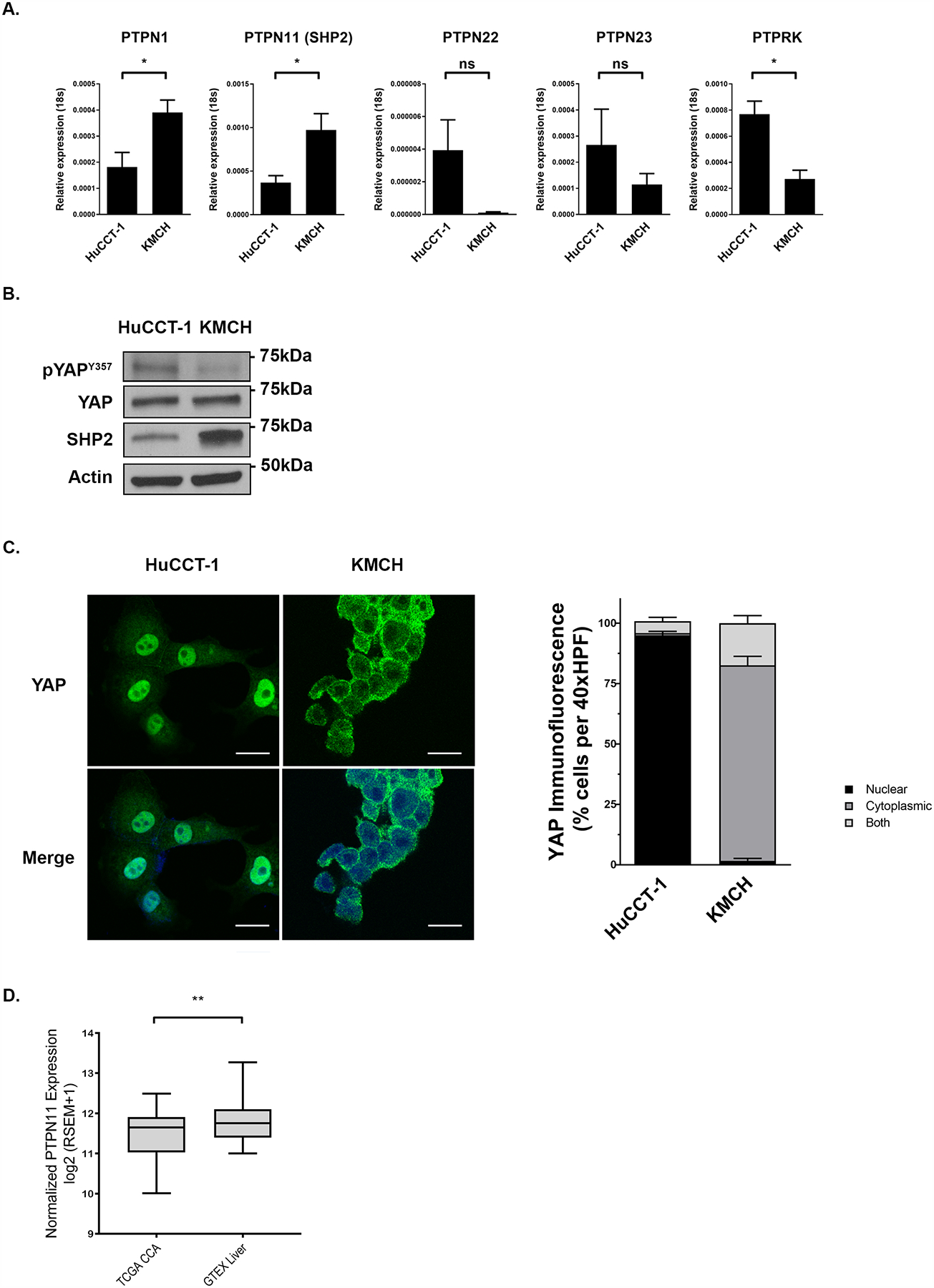

We have previously observed an association of a number of tyrosine phosphatases with YAP at baseline and dependent on its tyrosine phosphorylation status. In this previous screen, utilizing immunoprecipitation of an epitope tagged YAP in a murine CCA cell line, followed by mass spectroscopy, we noted an association of tyrosine-protein phosphatase non-receptor types 1, 11, 22, 23 as well as receptor-type tyrosine-protein phosphatase kappa with YAP, which increased following incubation with the SFK inhibitor Dasatinib [9]. Tyrosine-protein phosphatase non-receptor type 11 (also known as SHP2) has previously been identified as a YAP binding protein; and it has been proposed that YAP functions as a shuttle for SHP2 as part of confluency sensing machinery [31]. The remaining phosphatases had not previously been identified as YAP-interacting phosphatases. We initiated our evaluation by assessing levels of these candidate YAP-interacting tyrosine phosphatases by RT-PCR (PTPN1, 11, 22, 23, PTPRK) and then confirming levels by immunoblot in the CCA cell lines HuCCT1 and KMCH (Fig 1a–b). These two CCA cell lines were utilized as they have distinct pYAPY357 status and YAP cellular compartmentation (nucleus vs. cytoplasm); with HuCCT1 cells demonstrating higher levels of pYAPY357, and nuclear localized YAP; whereas KMCH cells demonstrate lower levels of pYAPY357, and cytoplasmic localized YAP at baseline (Fig.1b–c). In the CCA cell lines, we noted an inverse relationship between the levels of the YAP-interacting tyrosine phosphatases SHP2 (encoded by the PTPN11 gene) and PTP1b (encoded by the PTPN1 gene) and pYAPY357; suggesting that these phosphatases may be in fact regulators of phosphorylation status in CCA (Fig 1a–b). Furthermore, these data indicated that the HuCCT1 and KMCH cells have not only unique pYAPY357 profiles, but also have unique phosphatase profiles making them informative models to further dissect the role of tyrosine phosphatases in YAP regulation. Importantly the HuCCT1 cell line carries an activating KRASG12D mutation and the KMCH cell line carries an activating BRAFL485W mutation allowing us to evaluate the SHP2 regulation of YAP independent of direct effects on the MAP kinase signaling pathway (as SHP2 functions in signal transduction upstream of RAS activation). Expression levels of PTPN22, 23, and PTPRK did not correlate with pYAPY357 levels in these two CCA cell lines. We next evaluated publically available RNA sequencing databases and found that PTPN11 (SHP2) expression specifically was lower in cholangiocarcinoma specimens as compared to normal liver, further supporting a potential role for decreased SHP2 levels in cholangiocarcinoma biology (Fig. 1d). Indeed, in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)-CHOL dataset, five of the included CCA samples have a deletion in PTPN11 (SHP2) and gene expression is correlated with copy number (p=0.003). While SHP2 has been demonstrated to be an oncogene based on its role in RAS signal transduction in multiple tumor types, notably it has previously been demonstrated as a tumor suppressor in hepato-carcinogenesis, and based on this we further explored the possibility that SHP2 phosphatase activity could directly regulate YAP activity, thus behaving as a tumor suppressor in CCA [39–42].

Figure 1. Tyrosine phosphatase levels are altered in CCA and have an inverse relationship to YAP phosphorylation.

(A) mRNA expression of YAP associated tyrosine phosphatases in HuCCT-1 and KMCH cell lines. *, p < 0.05. (B) Cell lysates from the HuCCT-1, and KMCH cell lines were subjected to immunoblot for phosphorylated YAP tyrosine 357 (pYAPY357) and SHP2. Total YAP and actin were used as loading controls. (C) Representative images of YAP immunofluorescence in HuCCT-1 and KMCH cell lines with quantification of YAP localization. Original magnification 40x. Scale bar = 10 microns. (D) PTPN11 (SHP2) differential expression analysis of public TCGA CCA samples compared to public GTEx normal liver samples. **, p < 0.01.

SHP2 can regulate YAP activity and subcellular localization in CCA.

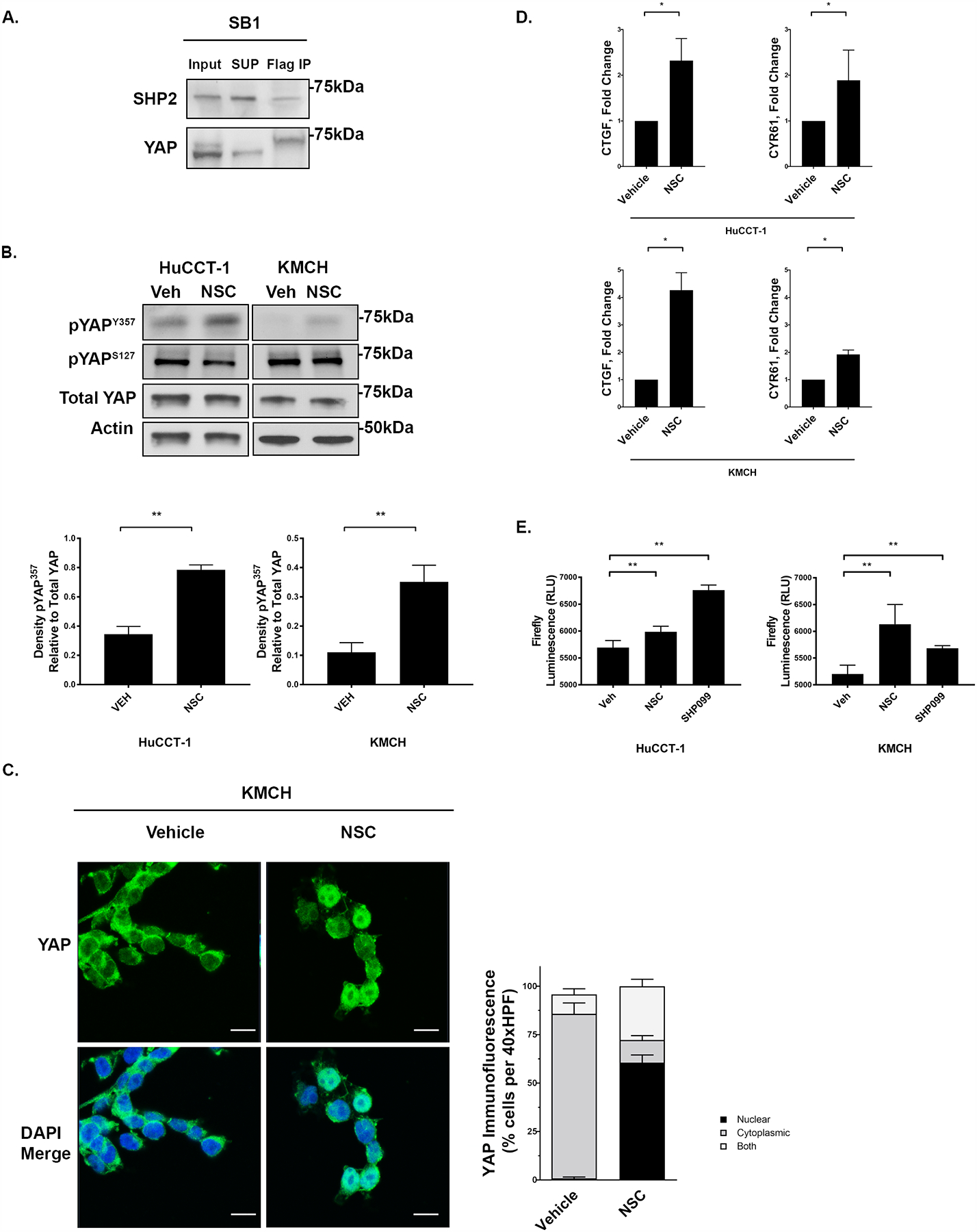

As an initial step we confirmed the findings of our immunoprecipitation-mass spectroscopy screen by performing co-immunoprecipitation experiments which demonstrated that SHP2 directly interacts with YAP in CCA cells (Fig. 2a). As SHP2 has previously been demonstrated to dephosphorylate the Y357 residue of YAP [43], we then explored the SHP2-YAP interaction in CCA utilizing a pharmacologic approach with attention to the effects of SHP2 inhibition on YAP phosphorylation status, subcellular localization, and transcriptional activity. In both HuCCT1 and KMCH cells, exposure to the SHP2 inhibitor NSC87877 (NSC) was associated with increases in pYAPY357 abundance, and consistent with effects on tyrosine phosphorylation independent of the serine/threonine Hippo kinase cascade, no change was noted in pYAPS127 abundance (Fig. 2b). NSC has activity against SHP1 as well as SHP2, with SHP1 a known negative regulator of SFK activity by limiting its autophosphorylation [44]. In order to evaluate the possibility that increased pYAPY357 levels may be due to reduced SHP1 activity (leading to increased SFK activity) we utilized a second, structurally dissimilar SHP2 inhibitor, SHP099, and found this inhibitor also increased pYAPY357 levels (Supplemental Fig. 1a). Furthermore, we evaluated the levels of active SRC (pSRCY416) by immunoblot and did not observe an increase in pSRC levels following NSC exposure (Supplemental Fig. 1b). Taken together these data suggested that SHP1 was not involved in regulating pYAPY357 levels and that there was baseline tonic activity of SHP2 on YAP regulating its Y357 phosphorylation status. We next sought to evaluate the consequence of SHP2 inhibition in relation to YAP subcellular localization and co-transcriptional activity. Shuttling of YAP into and out of the nucleus has been shown to be regulated by tyrosine phosphorylation limiting the interaction of YAP with exportin proteins, leading to nuclear accumulation of YAP [26]. As such we evaluated the subcellular localization of SHP2 in KMCH cells to determine whether SHP2 would be localized in the nucleus and noted at baseline SHP2 was indeed enriched in the nucleus (Supplemental Fig. 1c), consistent with the possibility that the low levels of nuclear YAP in KMCH cells were secondary to SHP2 phosphatase activity. Furthermore, exposure of KMCH cells (in which YAP is localized to the cytoplasm at baseline) to NSC, was associated with a shift of YAP to the nuclear compartment (Fig. 2c). Consistent with the increases in pYAPY357 abundance and the anticipated activation of YAP, co-transcriptional activity was also increased. Evaluation of YAP-TEAD transcription broadly utilizing a luciferase reporter construct demonstrated significant increases after both NSC and SHP099 exposure and specific expression of the YAP target genes CTGF and CYR61 were increased in both HuCCT1 and KMCH cells (Figs. 2d–e). In keeping with the profiling data suggesting that KMCH cells had lower pYAPY357 levels and higher SHP2 levels, we noted larger fold increases in YAP cognate target gene expression in KMCH cells compared to the HuCCT1 cells, even though significant increases in YAP target gene levels were also noted in HUCCT1 cells. We next explored whether SHP2 inhibition by NSC may also shift YAP from a cytoplasmic to nuclear compartment in a non-CCA cell line. We utilized the PANC1 pancreas cancer cell line in which, like KMCH cells, at baseline YAP is enriched in the cytoplasm. Similar to KMCH cells, incubation of the PANC1 cells with NSC shifted YAP to the nuclear compartment (Supplemental Fig. 2a). These findings supported a role for SHP2 regulating YAP tyrosine phosphorylation, subcellular compartmentalization and co-transcriptional activity; therefore we sought to further explore the specificity of these findings utilizing a genetic paradigm. We utilized an inducible CRISPR/Cas9 mediated deletion of PTPN11 (SHP2). Deletion of SHP2 in the KMCH cell line was achieved after 48 hours of treatment with doxycycline (Supplemental Fig. 3a). In the KMCH cells, which at baseline have high SHP2 levels, deletion of SHP2 was associated with an increase in pYAPY357 levels (Fig. 3a). In addition, we assessed the Hippo and MAP kinase pathways following SHP2 deletion and observed no significant change in either pYAPS127 or pERK levels (Fig. 3a), similar to pharmacologic SHP2 inhibition (Fig. 2b and Supplemental Fig. 3b). The increase in pYAPY357 levels was associated with a shift of YAP to the nuclear compartment and increased YAP co-transcriptional activity as measured by expression of cognate YAP target genes, similar to pharmacologic SHP2 inhibition (Fig. 3b–c). These data suggest that SHP2 can directly regulate YAP activity by regulating the abundance of pYAPY357 independent of the Hippo pathway and distinct from SHP2-mediated effects on the MAP kinase pathway; and thus may indeed behave as a tumor suppressor in CCA.

Figure 2. SHP2 can regulate YAP activity and subcellular localization in CCA.

(A) Cell lysates of SB1 cells that contain FLAG-YAPS127A were subjected to anti-Flag immunoprecipitation and western blot analysis of endogenous SHP2. Total YAP serves as a loading control in inputs. (B) Cell lysates from the HuCCT-1, and KMCH cell lines treated with NSC87877 (NSC, 10 μM, 3 hours) were subjected to immunoblot for phosphorylated pYAPY357 and pYAPS127 with representative densitometry of pYAP357 relative to Total YAP. **, p < 0.01. Total YAP and actin were used as loading controls. (C) Representative images of YAP immunofluorescence in KMCH cell lines +/− NSC (10 μM, 3 hours) with quantification of YAP localization. Original magnification 40x. Scale bar = 10 microns. (D) mRNA expression of CTGF and CYR61 in HuCCT-1 and KMCH +/− tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor NSC (10 μM, 3 hours). Fold change relative to vehicle. *, p < 0.05. (E) Global TEAD transcriptional activity in HuCCT1 and KMCH cells using a luciferase-based TEAD reporter. Cells were treated with NSC or SHP099 at 10 uM for 24 hours prior to measurement of firefly luciferase activity. **, p < 0.01.

Figure 3. SHP2 deletion increases YAP nuclear localization, and transcriptional activity.

(A) Cell lysates from KMCH cell lines transfected with empty or SHP2 targeting CRISPR sgRNA were subjected to immunoblot for pERK, pYAPY357, pYAPS127 and SHP2. Total YAP and actin were used as a loading control. (B) KMCH cell lines transfected with a doxycycline inducible CRISPR/Cas9 construct targeting SHP2 were incubated with doxycycline (7.5 μg/mL) for the noted time. Immunofluorescence for YAP was undertaken and representative images with quantification of YAP localization are displayed. Original magnification 40x. Scale bar = 10 microns. (C) CTGF and CYR61 mRNA expression in KMCH cell line transfected with sgEmpty and sgSHP2 +/− induction with doxycycline (7.5 μg/mL). Fold change relative to non-induced control. *, p < 0.05.

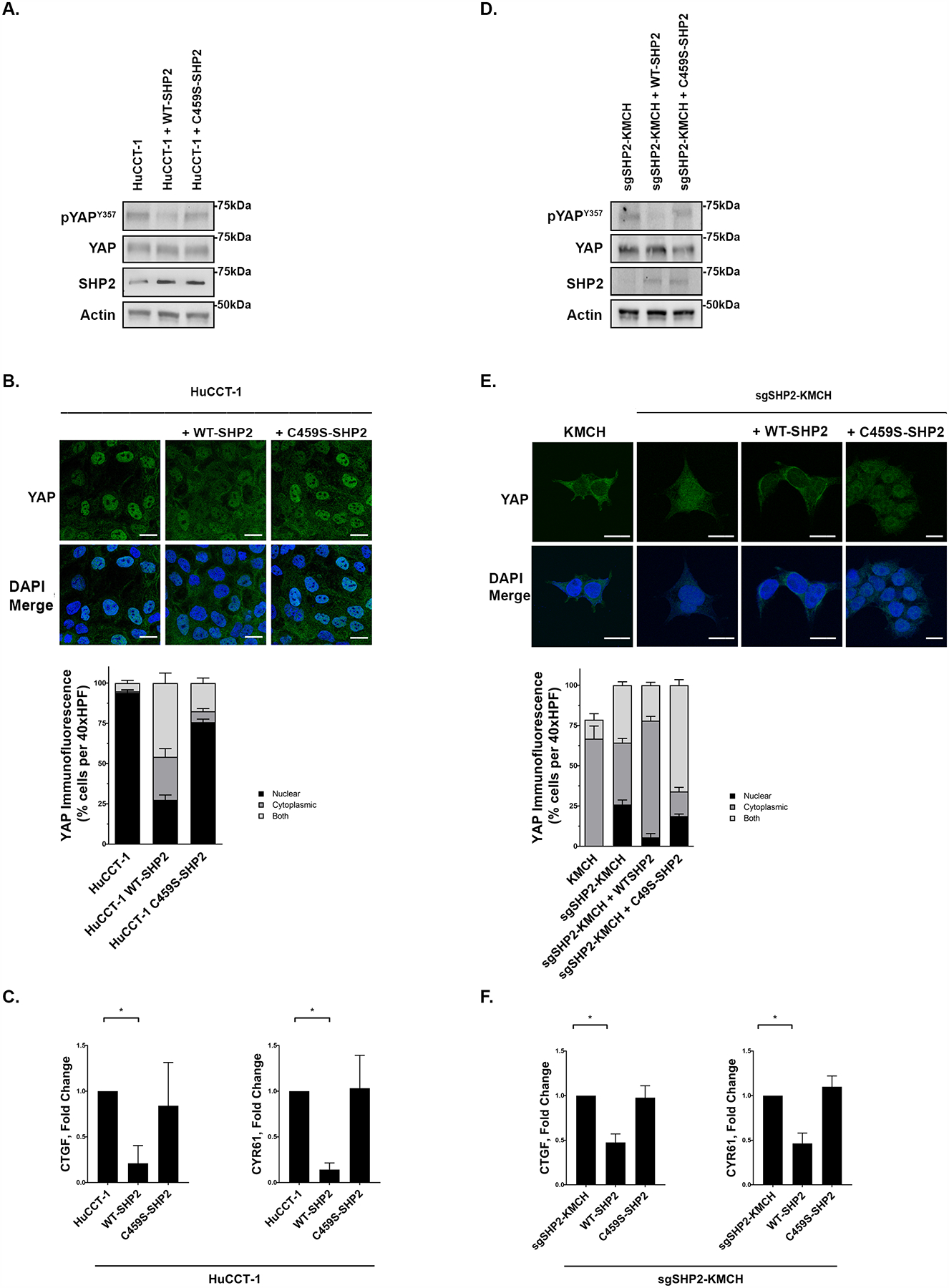

The Phosphatase Activity of SHP2 is required for YAP regulation.

Tyrosine phosphatases may regulate YAP activity via mechanisms unrelated to their phosphatase activity due to scaffolding functions [31, 32]. Given this, we next examined the role of phosphatase activity specifically in SHP2-mediated YAP regulation. We initiated these studies by exploring YAP localization and activity following enforced expression of wild-type SHP2 in HuCCT-1 cells (which have low baseline SHP2 levels). In HuCCT1 cells overexpressing wild-type SHP2, pYAPY357 levels were decreased and the localization of YAP was shifted from the nucleus to the cytoplasmic compartment. YAP transcriptional activity was also decreased (Fig. 4a–c). To extend these findings we expressed a SHP2 construct in which the phosphatase domain was mutated (C459S-SHP2). Expression of this phosphatase-dead construct had no demonstrable effect on pYAPY357 levels, YAP baseline localization, or YAP co-transcriptional activity (Fig. 4a–c). To further explore these observations, we pursued a deletion-reconstitution approach utilizing our inducible sgSHP2-KMCH cells. Following SHP2 deletion, doxycycline was withdrawn; and SHP2 levels were then reconstituted with either wild-type or phosphatase-dead constructs (Fig. 4d). Reconstitutions with wild-type SHP2, but not phosphatase-dead SHP2, was associated with a decrease in pYAP357 levels, YAP baseline nuclear localization and decreased YAP transcriptional activity (Fig. 4d–f). These observations suggest that the phosphatase activity of SHP2 is integral in regulating YAP in CCA.

Figure 4. The Phosphatase Activity of SHP2 is required for YAP regulation.

(A) Cell lysates from the HuCCT-1 cell line were transfected with WT SHP2 or C459S SHP2 (phosphate dead construct) and subjected to immunoblot for pYAPY357 and SHP2. Total YAP and actin were used as loading controls. (B) HuCCT-1, HuCCT-1 + WT-SHP2, and HuCCT-1 + C4592-SHP2 underwent immunofluorescence for YAP and representative images are displayed with quantification of YAP localization. Original magnification 40x. Scale bar = 10 microns. (C) mRNA expression of CTGF and CYR61 in HuCCT-1, HuCCT-1 + WT-SHP2, and HuCCT-1 + C4592-SHP2. Fold change relative to parental cell line control. *, p < 0.05. (D) KMCH cell line transfected with a doxycycline inducible CRISPR/Cas9 construct targeting SHP2 (sgSHP2-KMCH) were incubated with doxycycline (7.5 μg/mL) for 48 hours. The sgSHP2-KMCH cell lines were then washed and transfected with lenti virus over expressing WTSHP2 or C459S SHP2 constructs for 48 hours. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot for pYAPY357 and SHP2. Total YAP and actin were used as loading controls. (E) Immunofluorescence for YAP in KMCH, sgSHP2-KMCH, sgSHP2-KMCH + WT-SHP2, and sgSHP2-KMCH + C459S-SHP2 was performed and representative images with quantification of YAP localization are displayed. Original magnification 40x. Scale bar = 10 microns. (F) mRNA expression of CTGF and CYR61 in sgSHP2-KMCH, sgSHP2-KMCH + WT-SHP2, and sgSHP2-KMCH + C459S-SHP2. Fold change relative to parental sgSHP2-KMCH cell line. *, p < 0.05.

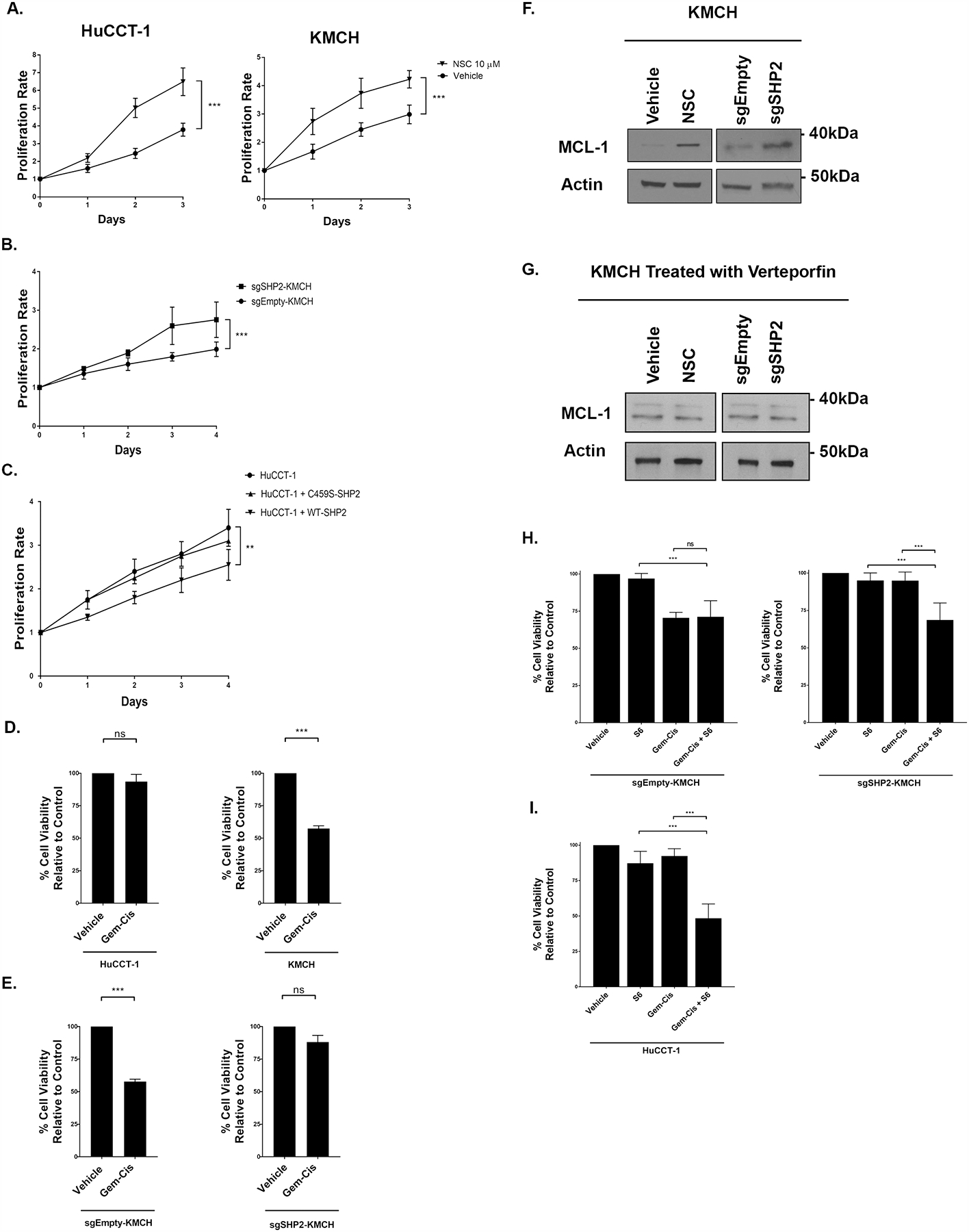

Tyrosine phosphatase activity is a critical determinant of CCA proliferation and in vitro sensitivity to standard of care chemotherapy.

Given the increases in YAP tyrosine phosphorylation and transcriptional co-activity observed with SHP2 downregulation, we examined the effect of SHP2 modulation on cellular proliferation. In both KMCH and HuCCT1 cells, incubation with NSC increased cellular proliferation compared to controls (Fig. 5a). We next examined sgSHP2-KMCH cells compared to sgEmpty-KMCH control cells after induction with doxycycline. Congruent with the pharmacologic observation, knockdown of SHP2 expression was associated with an increase in cellular proliferation (Fig. 5b). Correspondingly, in HuCCT1 cells, enforced expression of wildtype SHP2 was associated with a decrease in cellular proliferation, while C459S-SHP2 had no demonstrable effect (Fig. 5c). Increased YAP activity has been associated with chemoresistance [14–24], and given this we next examined the possibility that regulation of pYAPY357 by tyrosine phosphatases may also alter the sensitivity of CCA cell lines to gemcitabine and cisplatin, the current standard of care combinatorial therapy for CCA. We first explored this possibility utilizing our HuCCT-1 and KMCH cell lines. We observed decreased cell death in HuCCT-1 cells (low SHP2 levels) as compared to KMCH cells (high SHP2 levels) incubated with gemcitabine and cisplatin consistent with the possibility that YAP activation status, as denoted by pYAPY357 levels, modulates chemotherapeutic sensitivity (Fig. 5d). In order to further evaluate this possibility, we next incubated the sgEmpty-KMCH and sgSHP2-KMCH cell lines with gemcitabine and cisplatin. In line with our previous observations demonstrating increased YAPY357 phosphorylation and activity following SHP2 deletion, the sgSHP2-KMCH cells were resistant to the combination of gemcitabine and cisplatin (Fig. 5e). As we have previously demonstrated the pro-survival BCL2 family protein MCL1 to be a YAP target gene [45], we contemplated whether SHP2 inhibition and/or deletion could increase MCL1 levels as a mechanism of resistance to therapy. Indeed, following either NSC exposure or CRISPR/Cas9-mediated deletion of SHP2 we observed dramatic increases in MCL1 levels (Fig. 5f). We assessed the YAP dependence of MCL1 accumulation by repeating the studies in the presence of the YAP-TEAD inhibitor verteporfin. Verteporfin inhibited the MCL1 accumulation, supporting the concept that SHP2 inhibition/deletion increases MCL1 via a YAP dependent mechanism (Fig. 5g). We then hypothesized that targeting MCL-1 in cell lines that demonstrate high pYAPY357 and concomitant resistance to gemcitabine and cisplatin therapy may restore chemosensitivity. Indeed, both HuCCT1 and sgSHP2-KMCH cells treated with the MCL1 inhibitor S63845 (S6) demonstrated sensitivity to gemcitabine and cisplatin while S6 alone had no effect (Fig. 5h). We then asked whether or not sensitivity to gemcitabine and cisplatin could similarly be restored in the HuCCT1 cell line, which like the sgSHP2-KMCH have high levels of pYAPY357, low baseline levels of SHP2, and are resistant. Indeed, the addition of S6 sensitized the HuCCT1 cells to gemcitabine and cisplatin (Fig. 5i). These findings suggest that high pYAPY357 levels, which can be driven by loss of SHP2 activity, can reduce the sensitivity of CCA cells to standard of care chemotherapy via an MCL1-dependent mechanism.

Figure 5. Tyrosine phosphatase activity is a critical determinant of CCA proliferation and in vitro sensitivity to standard of care chemotherapy.

(A) HuCCT-1, and KMCH cell lines +/− NSC (10 μM, 3 days) were subjected to MTS assay daily for 3 days. The proliferation rate was calculated by the daily absorbance value relative to the respective day zero value. ***, p < 0.001. (B) KMCH cell lines transfected with a doxycycline inducible CRISPR/Cas9 construct targeting SHP2 (sgSHP2-KMCH) were incubated with doxycycline (7.5 μg/mL) for 48 hours. The KMCH and sgSHP2-KMCH cells were evaluated with MTS assay daily for 4 days. The proliferation rate was calculated by the daily absorbance value relative to the respective day zero value. ***, p < 0.001. (C) HuCCT-1 cell lines were transfected with WT SHP2 and C459S SHP2 constructs for 48 hours. HuCCT-1, HuCCT-1 + WT-SHP2, and HuCCT-1 + C4592 SHP2 were assessed with MTS assay for 4 days. The proliferation rate was calculated by the daily absorbance value relative to the respective day zero value. **, p < 0.01. (D) Percent cell viability (relative to control) of HuCCT-1 and KMCH cell lines measured by CellTiter-Glo assay following incubation with gemcitabine/cisplatin (100 nM, 72 hours). ***, p < 0.001. (E) Percent cell viability (relative to control) of KMCH and sgSHP2-KMCH cell lines measured by CellTiter-Glo assay following incubation with gemcitabine/cisplatin (100 nM, 72 hours). ***, p < 0.001. (F) Cell lysates from the KMCH cell lines treated with NSC (10 μM, 3 hours) or transfected with empty and SHP2 targeting CRISPR sgRNA were subjected to immunoblot for MCL-1. Actin was used as a loading control. (G) Cell lysates from the KMCH cell line treated with Verteporfin (10 μM, 3 hour) followed by NSC (10 μM, 3 hours) were subjected to immunoblot for MCL-1. sgEmpty-KMCH and sgSHP2-KMCH cells treated with Verteporfin (10 μM, 3 hour) were subjected to immunoblot for MCL-1. Actin was used as a loading control. (H) Percent cell viability (relative to control) of sgEmpty-KMCH and sgSHP2-KMCH cells measured by CellTiter-Glo assay following incubation with gemcitabine/cisplatin +/− S63845 (100 nM and 5μM, 72 hours). ***, p < 0.001. (I) Percent cell viability (relative to control) of HuCCT-1 cells measured by CellTiter-Glo assay following incubation with gemcitabine/cisplatin +/− S63845 (100 nM and 5μM, 72 hours). ***, p < 0.001.

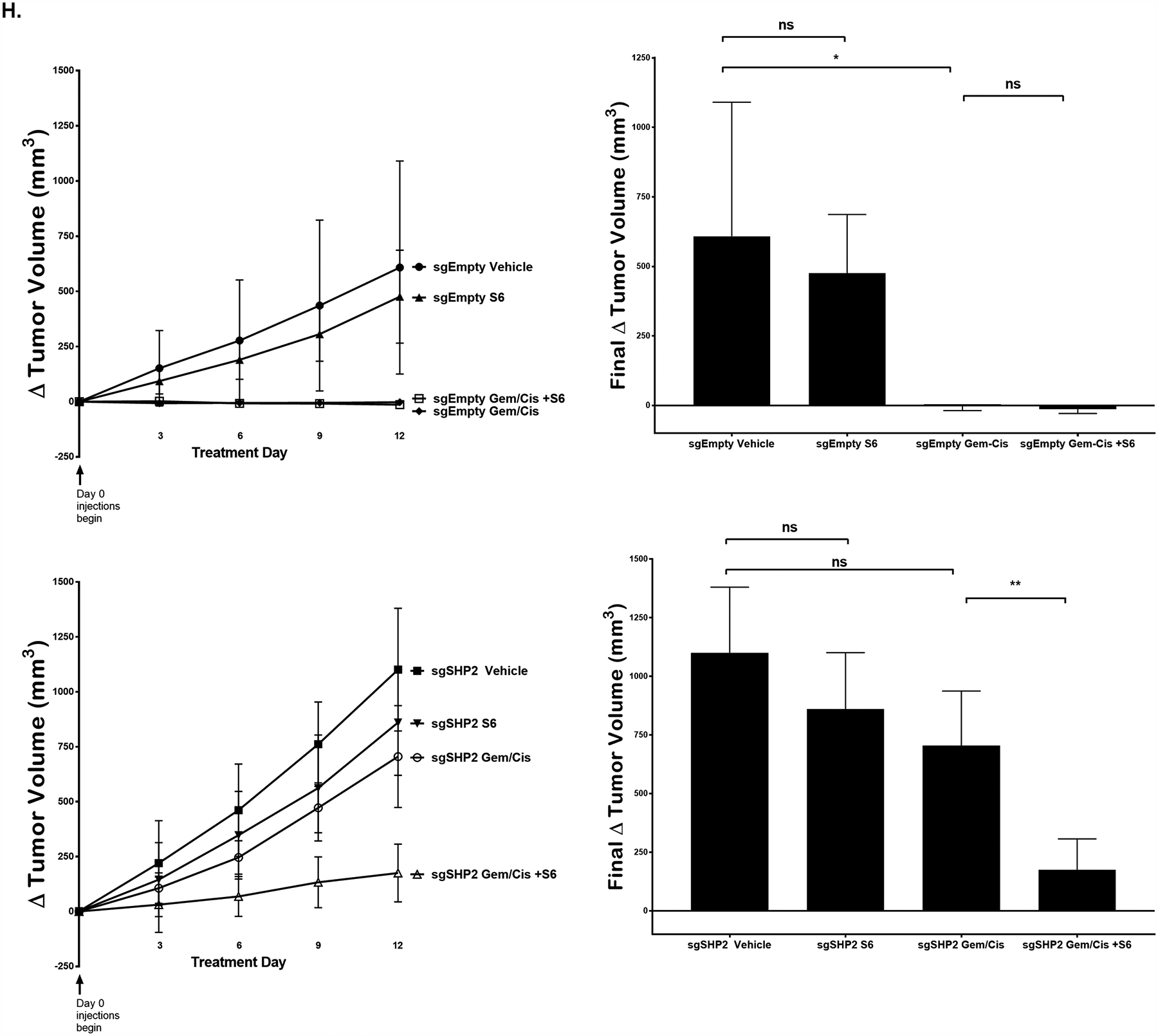

Deletion of SHP2 reduces in vivo sensitivity of CCA xenografts to standard of care chemotherapy, which can be overcome by the addition of MCL1 inhibition.

Based on the findings in the in vitro experiments we explored the effects of phosphatase deletion on the sensitivity of CCA cell line xenografts to gemcitabine plus cisplatin in a flank model. The sgEmpty-bearing KMCH cells were placed in one flank and the sgSHP2-KMCH in the other flank of NOD/SCID mice, ensuring equal chemotherapy dosing of each tumor within each animal (Fig. 6a). In keeping with the observations noted in vitro, the SHP2 phosphatase knockout cell line xenografts (sgSHP2-KMCH) developed tumors with faster growth (Fig. 6b). When treated with gemcitabine plus cisplatin, the sgEmpty-KMCH tumors stabilized and decreased in size, while the sgSHP2-KMCH continued to grow with the same kinetics as the vehicle treated sgEmpty-KMCH tumors. The vehicle treated SHP2 deleted tumors displayed the fastest growth rates (Fig. 6c). Immunoblot evaluation of YAP from these tumors demonstrated increased levels of pYAPY357 in the sgSHP2-KMCH bearing tumors as compared to the sgEmpty-KMCH xenografts, consistent with the in vitro results (Fig. 6d). Accordingly, YAP cognate target gene expression was higher in the SHP2 knockout xenografts (Fig. 6e). Furthermore, immunoblot and gene expression evaluation of MCL1 levels were also noted to be higher in the SHP2 knockout xenografts (Fig. 6f–g). We then asked whether the addition of the MCL1 inhibitor S63845 could restore chemosensitivity in vivo [46]. Indeed, the addition of S63845 to gemcitabine and cisplatin partially restored sensitivity in sgSHP2-KMCH cell line xenografts (Fig. 6h). These observations were congruent with our in vitro findings, and further supported a role for SHP2 in modulating the sensitivity of CCA to gemcitabine/cisplatin combinatorial therapy via a YAP-MCL1 mechanism.

Figure 6. Deletion of SHP2 reduces in vivo sensitivity of CCA xenografts to standard of care chemotherapy.

(A) In vivo study design. (B) Tumor volume of mice (sgEmpty-KMCH, and sgSHP2-KMCH) on treatment day 0. *, p < 0.05. (C) Δ Tumor volume of mice (sgEmpty-KMCH, and sgSHP2-KMCH) with q3d x 2 weeks intraperitoneal injection of either combination gemcitabine (15mg/kg) and cisplatin (1mg/kg) or normal saline. **, p < 0.01. (D) Cell lysates from xenografts of sgEmpty-KMCH and sgSHP2-KMCH were subjected to immunoblot for pYAPY357. Total YAP and actin were used as a loading control. (E) CTGF and CYR61 mRNA expression of sgEmpty-KMCH and sgSHP2-KMCH xenografts. Fold change relative to sgEmpty-KMCH control. *, p < 0.05. (F) Cell lysates of sgEmpty-KMCH and sgSHP2-KMCH xenografts were subjected to immunoblot for MCL-1. Actin was used as a loading control. (G) MCL-1 mRNA expression of sgEmpty-KMCH and sgSHP2-KMCH xenografts. Fold change relative to sgEmpty-KMCH control. **, p < 0.01. (H) Δ Tumor volume of mice (sgEmpty-KMCH, and sgSHP2-KMCH) with q3d x 2 weeks treatment. Treatments included S6 (25 mg/kg), combination gemcitabine (15mg/kg) cisplatin (1mg/kg), combination gemcitabine (15mg/kg) cisplatin (1mg/kg) and S6 (25 mg/kg), or normal saline. *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

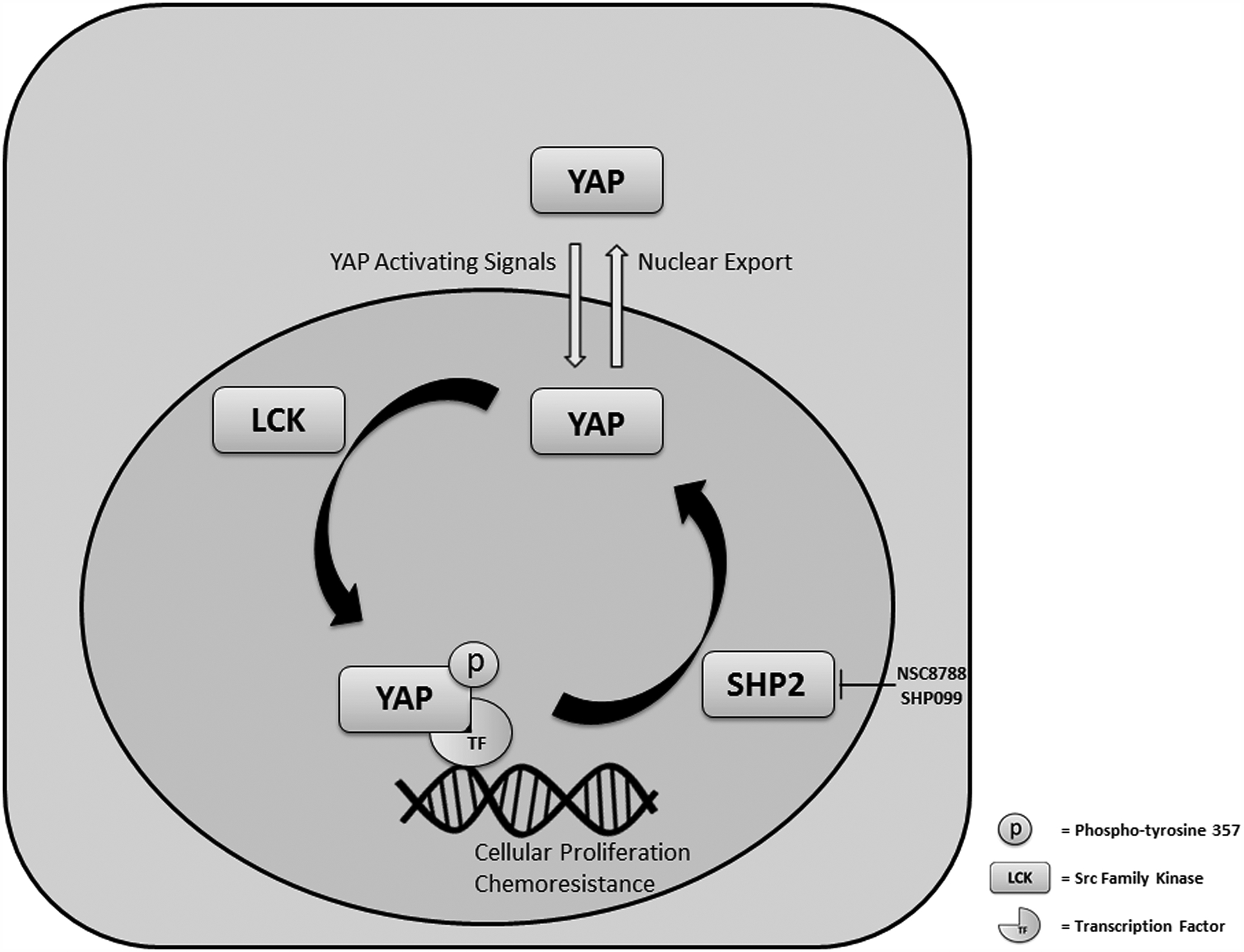

This study supports a role for the tyrosine phosphatase SHP2 in regulating YAP tyrosine phosphorylation and sensitivity to chemotherapy in cholangiocarcinoma (Fig. 7). These data indicate that: (1) the tyrosine phosphatase SHP2 can regulate tyrosine phosphorylation of YAP, (2) phosphatase activity specifically is required for regulation of YAP, and (3) deletion/inhibition of SHP2 increases cellular proliferation and decreases sensitivity to standard of care chemotherapy via YAP and MCL1 dependent mechanisms. These findings are discussed in greater detail below.

Figure 7. Summary of the Model.

SHP2 modulates proliferation and chemoresistance by regulating the tyrosine phosphorylation (activation) of YAP.

We identified the tyrosine phosphatase SHP2 as regulating YAP in CCA. Tsutsumi et. al previously identified SHP2 as a YAP/TAZ interacting protein following the observation that SHP2 subcellular localization was regulated by cell density in human gastric epithelial cells, and this regulation could be disrupted by the serine/threonine kinase inhibitor staurosporine[31]. Direct interaction of SHP2 and YAP/TAZ was demonstrated by co-immunoprecipitation experiments, and shRNA mediated knockdown of SHP2 in these cells did not appear to effect YAP localization. These findings lead the investigators to conclude that SHP2 was not regulating YAP/TAZ subcellular localization in this model, but that YAP/TAZ were regulating SHP2 localization. Of note, YAP/TAZ were highly enriched in the nucleus in these cells at baseline and based on our observations, and proposed mechanism of SHP2 regulation of YAP, we would not have expected to see any significant effects on YAP localization with SHP2 downregulation in that model; just as they observed. The ability of SHP2 to regulate YAP, and in turn the proliferation and chemosensitivity of CCA is initially striking given the previously described function of SHP2 as an oncogene in multiple tumor types through its positive effect on receptor tyrosine kinase-RAS signaling [39–41]. In fact, receptor tyrosine kinase driven malignancies have been demonstrated to be sensitive to SHP2 inhibition [47]. However, SHP2 has also been shown to be a tumor suppressor, specifically in hepatocellular carcinogenesis [42]. In these previous studies, deletion of SHP2 was accompanied by increased inflammatory signaling through STAT3 and eventually development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in mice [42]. These effects were magnified in an injury-inflammation model of HCC. Taken together these findings suggest that the oncogenic potential of SHP2 signaling is likely tissue and context dependent, such that it can act both as an oncogene through effects on MAP kinase signaling as well as a tumor suppressor through effects on YAP activity. Importantly we assessed the function of SHP2 in CCA cell lines that were RAS/RAF mutated, and as such could assess the YAP specific effects of SHP2 modulation without any obscuring effects on MAP kinase signaling.

Other studies have demonstrated a potential role for tyrosine phosphatases in the regulation of YAP. Wang et. al described a role for the protein tyrosine phosphatase PTPN14 in regulating YAP subcellular localization in the breast cancer cell line MCF10A [32]. These investigators noted that overexpression of PTPN14 led to a dramatic shift of YAP from the nucleus to the cytoplasm and conversely, downregulation by shRNA led to redistribution of YAP to the nucleus. The pYAPY357 levels were not evaluated, however these investigators did overexpress a phosphatase-dead construct which also was associated with YAP cytoplasmic translocation in the MCF10A cells; suggesting that the phosphatase activity of PTPN14 was not required for YAP regulation in these cells. Given these previous findings, we specifically evaluated the role of the phosphatase function of SHP2 in regulating YAP. Similar to Wang et. al we saw a decrease in nuclear localized YAP with enforced over expression of wild-type SHP2, however we also noted a decrease in pYAPY357 levels; and neither of these were observed with the catalytically inactive C459S-SHP2 construct. These data were further supported by the reconstitution experiments; re-expressing wild type SHP2 in CCA cells in which endogenous PTPN11 (SHP2) was deleted via a CRISPR/Cas9 approach. These data suggest that, unlike PTPN14 in breast cancer cells, the phosphatase activity of SHP2 is important for the regulation of YAP in CCA. We did not specifically note PTPN14 as a YAP associated phosphatase in evaluation of our CCA cells and it is possible that there are tissue/cell type specific differences both in the phosphatases associating/regulating YAP, and the specific mechanisms of action of those interactions.

Our finding that SHP2 levels/activity can modulate the sensitivity of CCA cells to the standard of care combinatorial therapy gemcitabine and cisplatin is consistent with previous data in multiple tumor types suggesting that increased YAP levels/activity can decrease the sensitivity to cytotoxic chemotherapy [15–17, 19, 21–23]. For example, decreased YAP activities through genetic silencing or pharmacologic approaches (utilizing the YAP-TEAD inhibitor verteporfin) have been associated with increased chemotherapy sensitivity to taxol in colorectal cancer models and cisplatin in hepatocellular carcinoma models [21–23]. Furthermore, YAP activation has been associated with decreased efficacy of other DNA-damaging agents such as radiation [16–18]. Even the efficacy of targeted agents has been observed to be affected by YAP activation, whereby resistance is associated with elevated YAP activity/levels [16, 20, 24]. In RAS/RAF driven cancers YAP signaling has been shown to overcome directed inhibition, suggesting that YAP activation can act as a parallel survival pathway [20, 25]. The activation of YAP we observed in our models with SHP2 deletion and pharmacologic inhibition is of significant relevance given the evaluation of SHP2 inhibitors as anti-cancer therapeutics [47]. Our observations would suggest that this may be counterproductive in some tumor types, such as CCA, which may be dependent on the balance of RAS/RAF/YAP activation. In contrast, our finding that MCL1 was markedly upregulated downstream of YAP activation, and that MCL1 inhibition could restore sensitivity to gemcitabine and cisplatin in the resistant cell lines indicates that targeting MCL1 may be a viable therapeutic approach; especially in tumors with hyper-activated YAP.

The role of tyrosine phosphatases as a regulator of YAP activity and by extension chemotherapeutic sensitivity is an intriguing paradigm. YAP has been observed to be “activated” in a number of tumor types; however an underlying genetic mechanism for this activation is not often apparent when examining canonical regulators, such as Hippo pathway components. For example, a small minority of patients with CCA have an identifiable mutation in a canonical regulator (NF2 and Salvador) in the TCGA analysis [48]. Thus, additional regulatory pathways continue to be of considerable interest in understanding YAP biology and function in oncogenesis and response to therapy. In CCA, tyrosine phosphatases as a gene family, are often mutated[49]; however whether or not all these are direct YAP interacting proteins and whether or not these derangements affect tumor progression or response to therapy has yet to be defined, and is an active area of investigation in our group. Additionally, other than genetic alterations, other possible mechanisms of regulating phosphatase activity and by extension YAP activity, warrant further investigation.

Overall our study contributes to the expanding knowledge regarding mechanisms of YAP regulation, independent of the Hippo pathway. Our observations provide further support for the model of tyrosine phosphorylation of YAP as a key regulator of function and a nuclear retention signal; and suggest a novel role for SHP2 tyrosine phosphatase activity in modulating this signal. These observations may have implications for further understanding YAP regulation in CCA specifically, and response to therapy broadly. We speculate that pYAPY357 phosphorylation and or SHP2 abundance may be biomarkers for response to standard of care chemotherapy in CCA and may select patients who will benefit from MCL1 directed combinatorial therapy.

Supplementary Material

Significance:

These findings demonstrate a role for SHP2 in regulating YAP activity and chemosensitivity, and suggest that decreased phosphatase activity may be a mechanism of chemoresistance in cholangiocarcinoma via a MCL1 mediated mechanism.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Grant Support: This work was supported by a Department of Defense Career Development Grant W81XWH-18-1-0297 (to R.L.S), the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) of the National Institutes of Health under award number T32DK07198 (to E.H.B), Optical Microscopy Core services provided through the Mayo Clinic Center for Cell Signaling in Gastroenterology (P30DK084567), the Mayo Clinic Medical Genome Facility - Proteomics Core, the Mayo Clinic Hepatobiliary SPORE (P50 CA210964) from the NCI, the Mayo Clinic Department of Surgery, and Mayo Clinic.

Footnotes

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Everhart JE and Ruhl CE, Burden of digestive diseases in the United States Part III: Liver, biliary tract, and pancreas. Gastroenterology, 2009. 136(4): p. 1134–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Razumilava N and Gores GJ, Classification, diagnosis, and management of cholangiocarcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2013. 11(1): p. 13–21 e1; quiz e3–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rizvi S and Gores GJ, Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of cholangiocarcinoma. Gastroenterology, 2013. 145(6): p. 1215–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valle J, et al. , Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med, 2010. 362(14): p. 1273–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li H, et al. , Deregulation of Hippo kinase signalling in human hepatic malignancies. Liver Int, 2012. 32(1): p. 38–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marti P, et al. , YAP promotes proliferation, chemoresistance, and angiogenesis in human cholangiocarcinoma through TEAD transcription factors. Hepatology, 2015. 62(5): p. 1497–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pei T, et al. , YAP is a critical oncogene in human cholangiocarcinoma. Oncotarget, 2015. 6(19): p. 17206–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smoot RL, et al. , Platelet-derived growth factor regulates YAP transcriptional activity via Src family kinase dependent tyrosine phosphorylation. J Cell Biochem, 2018. 119(1): p. 824–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sugihara T, et al. , YAP Tyrosine Phosphorylation and Nuclear Localization in Cholangiocarcinoma Cells Are Regulated by LCK and Independent of LATS Activity. Mol Cancer Res, 2018. 16(10): p. 1556–1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sugimachi K, et al. , Altered Expression of Hippo Signaling Pathway Molecules in Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Oncology, 2017. 93(1): p. 67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu H, et al. , Clinicopathological and prognostic significance of Yes-associated protein expression in hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Tumour Biol, 2016. 37(10): p. 13499–13508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamada D, et al. , IL-33 facilitates oncogene-induced cholangiocarcinoma in mice by an interleukin-6-sensitive mechanism. Hepatology, 2015. 61(5): p. 1627–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pan D, Hippo signaling in organ size control. Genes Dev, 2007. 21(8): p. 886–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zanconato F, Cordenonsi M, and Piccolo S, YAP/TAZ at the Roots of Cancer. Cancer Cell, 2016. 29(6): p. 783–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baia GS, et al. , Yes-associated protein 1 is activated and functions as an oncogene in meningiomas. Mol Cancer Res, 2012. 10(7): p. 904–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng H, et al. , Functional genomics screen identifies YAP1 as a key determinant to enhance treatment sensitivity in lung cancer cells. Oncotarget, 2016. 7(20): p. 28976–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ciamporcero E, et al. , YAP activation protects urothelial cell carcinoma from treatment-induced DNA damage. Oncogene, 2016. 35(12): p. 1541–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fernandez LA, et al. , Oncogenic YAP promotes radioresistance and genomic instability in medulloblastoma through IGF2-mediated Akt activation. Oncogene, 2012. 31(15): p. 1923–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hall CA, et al. , Hippo pathway effector Yap is an ovarian cancer oncogene. Cancer Res, 2010. 70(21): p. 8517–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin L, et al. , The Hippo effector YAP promotes resistance to RAF- and MEK-targeted cancer therapies. Nat Genet, 2015. 47(3): p. 250–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi G, et al. , Verteporfin enhances the sensitivity of LOVO/TAX cells to taxol via YAP inhibition. Exp Ther Med, 2018. 16(3): p. 2751–2755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang X, Wu B, and Zhong Z, Downregulation of YAP inhibits proliferation, invasion and increases cisplatin sensitivity in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncol Lett, 2018. 16(1): p. 585–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mao B, et al. , SIRT1 regulates YAP2-mediated cell proliferation and chemoresistance in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene, 2014. 33(11): p. 1468–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yun MR, et al. , Targeting YAP to overcome acquired resistance to ALK inhibitors in ALK-rearranged lung cancer. EMBO Mol Med, 2019: p. e10581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shao DD, et al. , KRAS and YAP1 converge to regulate EMT and tumor survival. Cell, 2014. 158(1): p. 171–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ege N, et al. , Quantitative Analysis Reveals that Actin and Src-Family Kinases Regulate Nuclear YAP1 and Its Export. Cell Syst, 2018. 6(6): p. 692–708 e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenbluh J, et al. , beta-Catenin-driven cancers require a YAP1 transcriptional complex for survival and tumorigenesis. Cell, 2012. 151(7): p. 1457–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tamm C, Bower N, and Anneren C, Regulation of mouse embryonic stem cell self-renewal by a Yes-YAP-TEAD2 signaling pathway downstream of LIF. J Cell Sci, 2011. 124(Pt 7): p. 1136–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taniguchi K, et al. , YAP-IL-6ST autoregulatory loop activated on APC loss controls colonic tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2017. 114(7): p. 1643–1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taniguchi K, et al. , A gp130-Src-YAP module links inflammation to epithelial regeneration. Nature, 2015. 519(7541): p. 57–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsutsumi R, et al. , YAP and TAZ, Hippo signaling targets, act as a rheostat for nuclear SHP2 function. Dev Cell, 2013. 26(6): p. 658–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang W, et al. , PTPN14 is required for the density-dependent control of YAP1. Genes Dev, 2012. 26(17): p. 1959–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Program, T.C.G.A. Cholangiocarcinoma (TCGA). The Cancer Genome Atlas Program; 2019. [cited 2019 11/1/2019]; Available from: https://www.cancer.gov/about-nci/organization/ccg/research/structural-genomics/tcga. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Project, T.G.-T.E.G., The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) Project 2019. [cited 2019 11/1/2019]; p. v8.p2.

- 35.Li B and Dewey CN, RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics, 2011. 12: p. 323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goldman M.e.a., The UCSC Xena platform for public and private cancer genomics data visualization and interpretation. bioRxiv, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmittgen TD and Livak KJ, Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nature protocols, 2008. 3(6): p. 1101–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li XM, et al. , Preclinical relevance of dosing time for the therapeutic index of gemcitabine-cisplatin. Br J Cancer, 2005. 92(9): p. 1684–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hill KS, et al. , PTPN11 Plays Oncogenic Roles and Is a Therapeutic Target for BRAF Wild-Type Melanomas. Mol Cancer Res, 2019. 17(2): p. 583–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ruess DA, et al. , Mutant KRAS-driven cancers depend on PTPN11/SHP2 phosphatase. Nat Med, 2018. 24(7): p. 954–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao H, et al. , Conditional knockout of SHP2 in ErbB2 transgenic mice or inhibition in HER2-amplified breast cancer cell lines blocks oncogene expression and tumorigenesis. Oncogene, 2019. 38(13): p. 2275–2290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bard-Chapeau EA, et al. , Ptpn11/Shp2 acts as a tumor suppressor in hepatocellular carcinogenesis. Cancer Cell, 2011. 19(5): p. 629–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xie J, et al. , Allosteric Inhibitors of SHP2 with Therapeutic Potential for Cancer Treatment. J Med Chem, 2017. 60(24): p. 10205–10219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Somani AK, et al. , Src kinase activity is regulated by the SHP-1 protein-tyrosine phosphatase. J Biol Chem, 1997. 272(34): p. 21113–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rizvi S, et al. , A Hippo and Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor Autocrine Pathway in Cholangiocarcinoma. J Biol Chem, 2016. 291(15): p. 8031–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kotschy A, et al. , The MCL1 inhibitor S63845 is tolerable and effective in diverse cancer models. Nature, 2016. 538(7626): p. 477–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen YN, et al. , Allosteric inhibition of SHP2 phosphatase inhibits cancers driven by receptor tyrosine kinases. Nature, 2016. 535(7610): p. 148–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Farshidfar F, et al. , Integrative Genomic Analysis of Cholangiocarcinoma Identifies Distinct IDH-Mutant Molecular Profiles. Cell Rep, 2017. 18(11): p. 2780–2794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gao Q, et al. , Activating mutations in PTPN3 promote cholangiocarcinoma cell proliferation and migration and are associated with tumor recurrence in patients. Gastroenterology, 2014. 146(5): p. 1397–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.